Abstract

Objectives

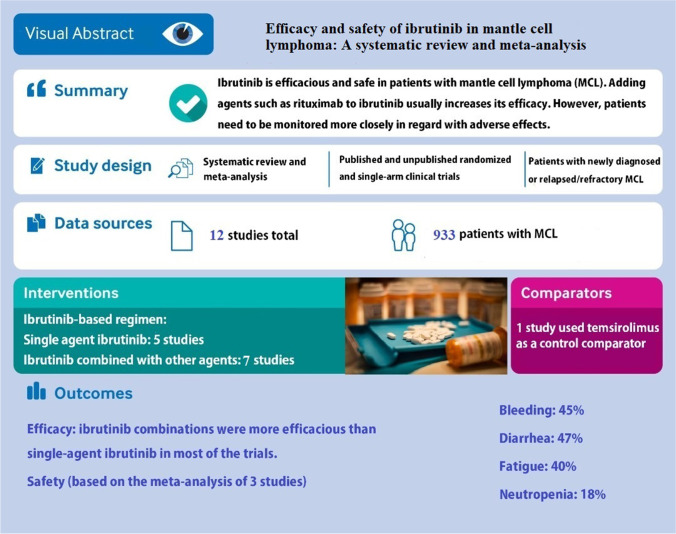

Since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ibrutinib to treat patients with refractory/relapsed mantle cell lymphoma (R/R MCL), it is used in clinical trials, whether as a single agent or in combination with other chemotherapy agents. The efficacy and safety of ibrutinib administration alone or in combinations have not been studied systematically. This study systematically reviewed the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib-containing regimens for the treatment of patients with MCL.

Evidence acquisition

We performed a systematic search in PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus. Then, a team of independent reviewers selected relevant studies and extracted the data.

Results

From a total of 1,436 studies, 12 trials were eligible. The overall response rates (ORRs) of patients with R/R MCL receiving single-agent ibrutinib ranged between 62.7% to 93.8%, and the ORRs of ibrutinib combinations ranged from 74 to 88%. In patients with newly diagnosed MCL receiving ibrutinib and rituximab, ORR ranged from 84 to 100%. The highest progression-free survival (PFS) was reported in patients receiving ibrutinib and rituximab (43 months). The meta-analysis performed on adverse events (AEs) demonstrated that single-agent ibrutinib had a high risk of bleeding, nausea, and diarrhea.

Conclusion

Single-agent ibrutinib showed acceptable efficacy and safety in the treatment of patients with MCL. Moreover, combining ibrutinib with other agents such as rituximab, venetoclax, and ublituximab can increase its efficacy and reduce chemotherapy-induced resistance in most cases; however, in the case of combination therapy, patients need to be monitored more strictly in terms of AEs. In our review, the ibrutinib and rituximab combination showed promising results in patients with R/R MCL. Also, this combination showed favorable efficacy and safety in patients with newly diagnosed untreated MCL, making it a great candidate to be studied more in large and well-designed trials.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40199-022-00444-w.

Keywords: Mantle cell lymphoma, Ibrutinib, Efficacy, Adverse events, Survival

Objectives

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is one of the rare subtypes of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), comprising approximately 2%-10% of all NHL cases, with an overall incidence of 0.5 to 1 case per 100,000 population in the United States [1]. Treatment of MCL is challenging due to a lack of efficient curative therapies and poor prognosis. Even though 50%-90% of patients respond to primary MCL therapy, most are vulnerable to the disease progression [2]. High-dose chemotherapy, followed by autologous stem cell transplantation, may improve survival in younger patients [3]. However, most MCL patients are elderly (i.e., a median of 68 years) and not eligible for such aggressive treatments [4]. Despite all efforts, MCL is not a curable malignancy, and virtually, all affected patients will encounter relapse or refractory disease. Several different regimens have been addressed to treat relapsed or refractory (R/R) MCL, including R–hyper-CVAD (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Doxorubicin, and Dexamethasone), bortezomib, and nucleoside analogs such as fludarabine [5]. However, some concerns have been raised about the safety and efficacy of these agents [5].

Ibrutinib is a small molecule that inhibits the function of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, a key signaling molecule for the growth and survival of malignant B cells [6]. In 2013, ibrutinib was approved for the treatment of MCL in patients who had received prior therapy [7]. Several studies with different implications have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib for MCL treatment; ibrutinib may be preferable for older or frail patients who are unlikely to tolerate the conventional chemotherapy regimens [8–12].

The efficacy and safety of ibrutinib as a single agent were evaluated and showed partial response (PR) at least in two-thirds of patients with R/R MCL [9]. In addition, the efficacy of ibrutinib administration in combination with other agents for the treatment of MCL has been evaluated in previous studies [10, 11, 13, 14], resulting in different overall response rates (ORRs).

Here, we aimed to comprehensively review all available phase II/III clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib either alone or in combination with other chemotherapy agents for the treatment of patients with MCL. In this study, we also performed pooled analyses of the incidence of 4 common adverse events (AEs) during ibrutinib administration to patients with MCL. Our systematic review provided the latest results of the trials concerning the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in patients with MCL compared to the published narrative reviews studying Bruton’s kinase inhibitors, including ibrutinib, in MCL treatment [15–22]. Due to the predefined search protocols and transparent selection criteria, our study might provide the best evidence regarding this topic up to now.

Evidence acquisition

This systematic review was performed and reported according to Cochran and PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) statements [23]. The systematic review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (ID: CRD42020160809).

Search strategy

We performed a systematic search in PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus. For PubMed search, we considered Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and for other databases, we used keywords. The search was conducted in June 2021 by 2 independent investigations in an unbiased manner (MR and MJ). No time or language restrictions were applied to our search strategy. The systematic review included both published full-text and ongoing studies with published abstracts. Finally, hand searching was performed to ensure that all relevant studies were obtained. Supplementary Table 1 provided the searched terms in different databases in detail.

Study selection

First, all relevant studies were imported into Thomson Reuters Endnote 7.1 software, and duplicates were removed. Second, 2 independent reviewers (M.R. and P.H.) screened the studies and included eligible studies based on their titles and abstracts. Then, the full texts of the studies were retrieved (if available), and the relevance of the full texts was evaluated by the reviewers (M.R. and P.H.). In the event that a full text was not available, we contacted the corresponding authors and asked if they could provide it. If the authors were reluctant to send the information or did not answer, the study was regarded as “relevant/irrelevant” based on its abstract.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

We merely included phase II and III trials based on PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome). (i) Population: patients who were suffering from MCL, either newly diagnosed or R/R. (ii) Intervention: ibrutinib, whether as a single agent or in combination with other chemotherapy agents. (iii) Comparator: ibrutinib vs. other agents or ibrutinib without comparators. (iv) Outcome: primary or secondary efficacy endpoints in oncology studies, such as overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and safety endpoints (such as the percentage of AEs in patients).

Exclusion criteria

Clinical trials with the following criteria were excluded: (i) phase I trials due to their small sample size and differences in the doses assigned to patients and (ii) studies on patients with B-cell lymphoma that did not report any efficacy/safety results for patients with MCL.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by 2 authors independently (M.R. and M.J.) according to the PRISMA guidelines [23]. In case of any differences or disagreements, by consulting the third author (A.M.) or consensus-based discussion, we resolved the problem and made the final decision.

The following information was extracted from each study: (i) general characteristics of the study (first author’s name, publication year, phase of the study, and study status [completed or ongoing]); (ii) descriptive data of the patients (number of patients, gender, age, inclusion criteria, number of prior therapies); (iii) duration of follow-up and treatment and the dose of ibrutinib and other drug agents; (iv) primary and secondary efficacy endpoints, such as ORR, complete response (CR) and PR, PFS, duration of response (DoR), OS, and time-to-response; and (v) hazard ratio (HR) and percentage of AEs.

Quality and risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality and risk of bias of included randomized controlled trial(s) were assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [24]. The following parameters were evaluated by the 2 authors (M.J. and V.A.): random allocation, blinding, selection bias caused by attrition, and selective reporting of outcomes. The overall risk of studies’ bias was defined as the low, moderate, serious, critical risk of bias, and no information. As there is no approved protocol for quality assessment of non-comparative studies (e.g., single-arm trials), we only evaluated the quality of single-arm studies based on data content, integrity, and publication in distinguished scientific journals. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus-based discussion.

Statistical analysis

Data from 3 studies [8, 9, 25] were analyzed using a random-effects model based on the inverse-variance method to estimate the pooled proportion of effect sizes with 95% CI among the included studies. We used standardized mean differences as the summary statistic for meta-analysis. Due to limitations in studies' arm matching, we could only perform the meta-analysis on reported AEs.

We assessed and quantified heterogeneity using the heterogeneity chi-square test. P values less than 0.05 and I2 statistic over 50% were considered statistically significant. We used Begg’s and Egger’s tests (P < 0.1), along with Begg’s funnel plot, to investigate the publication bias. All the analyses and plots were performed using STATA 13 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

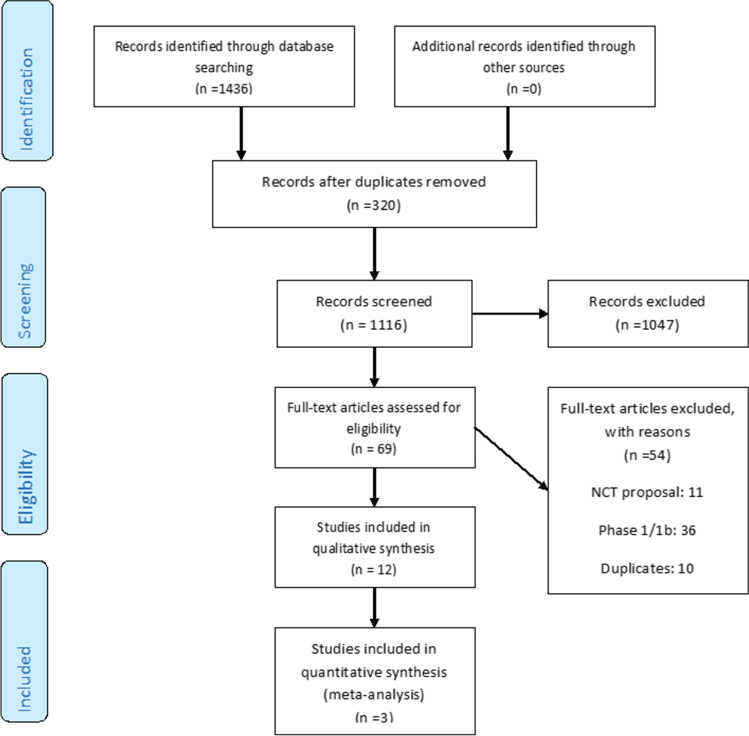

As depicted in Fig. 1, a total number of 1,436 initial relevant studies were identified from all database searches. After screening, only 12 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were considered for data extraction. Detailed characteristics of selected studies are shown in Supplementary Table 2. For all included studies, we extracted the latest version of the reported data.

Fig. 1.

The steps of selecting the trials

PICO

Population

The baseline characteristics of the cancer patients in trials, including the number of recruited patients, the number of previously received lines of therapy, the duration of follow-up and treatment modalities, and drug regimens, are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Type of malignancy

In phase II/III trials, Wang et al. [26], Jain et al. [12], and Gine et al. [27] studied newly diagnosed MCL patients, and Handunnetti et al. [14] had 1 untreated MCL patient in their study. Other studies investigated the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in patients with R/R MCL.

Age and gender

Among phase II/III trials, Dreyling et al. [28] had the highest number of included patients (N = 280). The median age of the included patients varied from 56 [26] to 72 [8] years old, and the patients were predominantly of the male gender 66% of patients).

Previous lines of therapy

Not all of the included trials reported the median number of previous lines of therapies, but in those mentioned, it ranged between 1 to 3 courses of chemotherapy.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

All phase II/III trials included patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) ≤ 2, except for the studies by Jerkman et al. [11] that included patients with ECOG-PS 0–3 and Gine et al. [27] that included patients with ECOG 0–1.

Intervention and comparison

The detailed data on dosages and schedules of administered drugs in phase II/III studies are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Single-agent vs. combination

Among 15 phase II/III studies, 4 studies used single-agent ibrutinib [8, 9, 25, 29], and 1 study compared single-agent ibrutinib vs. single-agent temsirolimus [30]. The remaining trials studied the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in combination with other agents.

Comparison

RAY et al.’s study [30] was the only randomized trial that compared ibrutinib with temsirolimus in terms of efficacy and safety; other included studies were single-arm trials.

Dose

All phase II/III trials treated MCL patients using 560 mg/day of ibrutinib (single agent or in combination) until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Follow-up duration

The follow-up duration among the phase II/III trials varied, with the shortest median follow-up of 6 months in the Kolibaba et al.’s study [10] and the most extended median follow-up of 47 months reported by Jain et al. [13].

Outcome

Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the endpoints of efficacy such as PFS, OS, ORR, median time to response (MTTR), DoR, and safety in trials, respectively.

ORR

Among all phase II/III trials that studied ibrutinib in combination with other agents in patients with R/R MCL, the highest reported ORR was 88% in patients receiving ibrutinib and rituximab [13] combination, and among the single-agent ibrutinib studies, the updated version of Maruyama et al.’s trial [8] reported the highest ORR (93.8%). On the contrary, the lowest ORR in single-agent trials (62.7%) was reported in patients previously treated by rituximab-containing regimens who had progressed after 2 cycles of bortezomib administration before receiving ibrutinib [25], and the lowest ORR (74%) in combination trials was in R/R MCL patients receiving a combination of Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, and rituximab [11]. Based on subgroup analyses in a trial studying ibrutinib and venetoclax combination [14], the lowest and the highest ORRs were seen in patients with TP53 (50%) and ATM (90%) genetic aberrations, respectively. Along with ibrutinib-containing regimens for the treatment of R/R MCL patients, this agent was used in numerous studies for newly diagnosed patients [26, 27]. The trials studying the combination of ibrutinib and rituximab in patients with newly diagnosed MCL showed high ORRs, ranging from 84% [27] to 100% [26] (see Supplementary Table 3).

CR

Jain et al. [13] reported the highest CR (58%) by administering a combination of ibrutinib and rituximab compared to the CR achieved (20.9%) by single-agent ibrutinib in patients with MCL receiving a rituximab-containing regimen and progressed after at least 2 cycles of bortezomib therapy [25]. Trials that studied the ibrutinib and rituximab combination in patients with newly diagnosed MCL reached high CRs, ranging from 71% [12] to 88% [26] (see Supplementary Table 3).

PFS

Among the studies that noted PFS, the combination of ibrutinib and rituximab [13] showed the highest PFS (43 months), while single-agent ibrutinib [25] showed the lowest PFS (10.5 months).

OS: Only 3 studies reached median OS [14, 30, 31]. The longest one was 32 months, reported by Handunnetti et el. [14].

MTTR

Two single-agent ibrutinib studies reported a “median time to initial response” [9, 25]. Also, one of these 2 studies [9], as well as the study of the ibrutinib and rituximab combination in young patients with newly diagnosed MCL, reported “median time to CR” [9, 26]. The trial investigating the ibrutinib and rituximab combination in elderly patients with newly diagnosed MCL reported the median number of cycles to reach CR [12].

DoR

Among the studies that reached DoR, Jain et al. [13] studied the ibrutinib and rituximab combination, and Wang et al. [25] studied single-agent ibrutinib, reporting the longest (46 months) and shortest (14.9 months) DoRs, respectively.

Time to next treatment

Only Rule et al. [30] reported time to next treatment.

Time to progression

Time to progression (TTP) was only estimated in the trial by Handunnetti et al. [14] that studied the ibrutinib and venetoclax combination for patients with R/R MCL.

Minimal residual disease

Karmali et al. [29] aimed to focus on the minimal residual disease (MRD) data of MCL patients. The authors found no relationship between MRD and efficacy endpoints such as PFS and OS. Also, Gine et al. [27] used an innovative approach by employing an MRD-driven therapy secession. Some other studies reported data related to MRD, which are mentioned in Supplementary Table 3 in the “Comment” section.

AEs

As various AEs, including hematological and non-hematological AEs, were reported in the trials, we did not present them here. Instead, we summarized the data relevant to AEs in Supplementary Table 4. Also, we conducted a meta-analysis on 4 of the AEs, including bleeding, neutropenia, diarrhea, and nausea. The results of this meta-analysis are presented at the end of the “Results” section.

Single-agent ibrutinib

In 2013, Wang et al. [32] reported the results of a phase II/III clinical trial that led to the approval of ibrutinib in patients with R/R MCL. In 2015, an update [9] with a longer follow-up was published (median time of follow-up: 26.7 months vs. 15.3 months in the previous study). In this study, patients were either bortezomib-treated or bortezomib-naïve. The final version of this trial could not confirm any association between previous bortezomib exposure and ORR. The longest DoR, PFS, and OS were detected in patients suffering from lower disease burden and less refractory conditions.

In 2014, Wang et al. [25] conducted another study to assess the efficacy and safety of single-agent ibrutinib exclusively in MCL patients who had received a prior rituximab-based regimen and progressed after at least 2 cycles of bortezomib. In subgroup analysis, ORR was independent of variables such as age, gender, geographic region, number of prior lines of therapies, baseline extranodal disease, simplified Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score, bulky disease, and stage of MCL.

Dreyling’s study in 2016 [28] is the only randomized clinical trial in this systematic review. In 2018, an update of this study with a longer follow-up (median 38.7 months vs. median 20 months) was published [30]. This team stratified 280 R/R MCL patients who had received 1 or more rituximab-containing treatments from 21 countries into ibrutinib (n = 139) or temsirolimus (n = 141) arms. Generally, patients in the ibrutinib group achieved a superior ORR, PFS, and OS compared with patients in the temsirolimus group. The initial analysis identified prior lines of treatment as a prognostic factor. Although the ORR results for ibrutinib were similar regardless of the number of prior lines of treatments (75% vs. 78% for 1 prior line and > 1 prior line, respectively), the patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy and then received ibrutinib benefited more than those who had received more than 1 line of therapy by achieving higher CR (33% vs. 16%) or by achieving a longer median DoR (22.3 months vs. 10.0 months) for those who had achieved PR. Additionally, the PFS of patients with 1 prior line of therapy was double than those who had received ibrutinib after more than 1 prior line of therapy (25.4 months vs. 12.1 months). Also, the OS of ibrutinib patients who had received only 1 previous cycle was almost 15 months more than patients who had received more than 1 cycle (42.1 months vs. 27.0 months). Regarding safety, fewer grade 3–4 AEs and fewer treatment discontinuations were observed in patients receiving ibrutinib compared to temsirolimus (75% vs. 87% and 17% vs. 32%, respectively). No new late-onset or cumulative toxicities were seen in the latest version of the study, supporting that ibrutinib might be safe even in longer durations of treatment.

Another multicenter, single-arm, phase II study assessed the efficacy and safety of single-agent ibrutinib in Japanese MCL patients [33] in 2016 and the final update in 2019 [8]. Before patients’ recruitment, all enrolled patients had received rituximab. Half of the patients had also received bendamustine, including 3 patients with radiotherapy. In this longer follow-up of patients (22.5 months), a deeper response was obtained, meaning that the number of patients who achieved CR increased from 1 (6.3%) to 5 (31.3%) from the first analysis to the last one. The safety profile of ibrutinib was acceptable without any unexpected AEs. In the final analysis [8], some insignificant changes in the incidence and severity of AEs were reported. Newly-proclaimed hemorrhagic toxicities included a severe grade 3 gastric hemorrhage in 1 patient, which was resolved after drug interruption. Also, the rate of stomatitis was higher (50% vs. 37.5%) than the previous study, but the rates of diarrhea and platelet count decreased, and some other AEs, such as anemia, remained the same.

Karmali et al. [29] aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of single-agent ibrutinib maintenance following chemo-immunotherapy for MCL. This study did not reach efficacy endpoints and only reported the endpoints related to safety (AEs).

Ibrutinib combinations

Combination of ibrutinib and rituximab

Jain et al. [13] studied the combination of ibrutinib and rituximab in R/R MCL patients who were heavily pretreated with different chemotherapy regimens, including rituximab, hyper-CVAD, bortezomib, and lenalidomide-containing regimens. R/R MCL patients with non-blastoid morphology, low-risk MIPI score, and low Ki-67% index (< 50%) benefited more from the combination therapy, demonstrating longer PFS and OS; also, the CR rate with ibrutinib plus rituximab (58%) was superior to the CR rate of patients receiving single-agent ibrutinib (23%) [9, 30]. Similar to the long-term data from single-agent ibrutinib therapy, the safety profile of ibrutinib plus rituximab did not indicate any additional long-term toxicities.

Due to the optimal and durable clinical responses of R/R MCL by ibrutinib and rituximab [13], this combination was considered for newly diagnosed, untreated young (< 65 years old) MCL patients [26]. This study aimed to administer ibrutinib plus rituximab as a chemotherapy-free induction, followed by fewer cycles (4 cycles) of chemo-immunotherapy consolidation (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone [R-HCVAD]/methotrexate, cytarabine [MTX-ara-C]) in order to reduce chemotherapy-induced AEs [26]. This study consisted of 2 parts: in part 1, the ibrutinib and rituximab combination was used without the addition of any chemotherapy agents till the best response, and in part 2, patients received a shortened course of intense chemo-immunotherapy, as described in detail in Supplementary Table 2. Twenty-two patients (17%) relapsed after treatment completion, including 6 who transformed to aggressive MCL. Despite the significantly shorter PFS in patients with aggressive histology (blastoid/pleomorphic) of the MCL compared with non-aggressive patients, the OS did not show any significant difference between these subgroups. Also, no differences were seen between the OS of patients with high and low Ki-67% indices [26].

Besides trying the ibrutinib and rituximab combination for young patients, Jain et al. [12] evaluated this combination as a frontline treatment in elderly patients (≥ 65 years). Elderly patients with MCL are usually treated with conventional chemo-immunotherapy, which poses risks such as worsening comorbidities, severe infections, second cancers, and the need for hospitalization in this age subgroup. As a result, ibrutinib and rituximab were tried for these patients as a completely chemotherapy-free approach hoping for fewer risks. The results showed that the risk of grade 3–4 myelosuppression and hospitalization for infection was lower (< 10%) compared to some chemo-immunotherapy studies [34–36]. Also, the risk of drug discontinuation due to disease progression was lower (8%) than in some other studies (40%-60%) [36, 37]. However, the risk of drug discontinuation because of drug intolerance was higher (42%) compared to some other studies (10%-25%) [35–37], possibly due to frequent comorbidities in elderlies. Patients who achieved CR as the best response to ibrutinib and rituximab therapy had a significantly better PFS than those without CR as the best response (P = 0.003). This study excluded patients with a Ki-67% index of more than 50% and blastoid morphology. The PFS and OS were not significantly different, but a higher risk of progression events was noticeable in those patients with Ki-67% higher than 30%. On the other hand, the response rate of patients with TP53 aberrations was lower than those without these aberrations. In this study, 17 out of 50 (34%) patients developed atrial fibrillation, 9 of whom (18%) were patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation. Therefore, this study suggests considering cardiac evaluation and cardiovascular risk factor modification before ibrutinib and rituximab therapy.

Finally, Gine et al. [27] conducted a phase II clinical trial to investigate the efficacy and toxicity of the ibrutinib and rituximab combination in previously untreated patients with indolent MCL. Hematologic toxicities, such as grade 3–4 neutropenia (22%), were more frequent in this study compared to a similar study of this combination in elderlies (grade 3–4 neutropenia = 8%) [12], possibly due to the more number of leukemia cases recruited in this study. On the other hand, these patients had a lower rate of gastrointestinal symptoms and fatigue compared with elderlies, which can be attributed to the better general condition and body performance of patients. The only unexpected toxicity was a case of severe aplastic anemia. Patients with TP53 mutations had a significantly lower PFS. Also, patients with a high-risk MIPI and TP53 mutation had a significantly lower OS. Of note, patients with TP53 mutations had lower DoRs than patients without these mutations. This study aimed to employ an MRD-driven approach, meaning that rituximab was used up to a total of 8 doses, but the decision upon when to discontinue ibrutinib was made based on MRD. Ibrutinib (560 mg) was used once daily and discontinued after 2 years of treatment in the case of sustained undetectable MRD (at least for 6 months at 2 consecutive determinations), otherwise until progression or unacceptable toxicity. As the data suggest, ibrutinib discontinuation was appropriate in cases with undetectable MRD, except for TP53-mutated cases, which showed a high risk of relapse even after molecular response.

Combination of ibrutinib, lenalidomide, and rituximab

Due to encouraging results achieved by administering either single-agent ibrutinib or the lenalidomide and rituximab combination in patients with R/R MCL, Jerkeman et al. [11] hypothesized that the combination of these 3 would increase efficacy compared to each agent per se. Therefore, in an open-label, single-arm, phase II trial in R/R mantle cell patients who had previously been treated (n = 50) with rituximab-containing regimens, these agents were used in combination as an induction treatment, and then during the maintenance phase, ibrutinib and rituximab were continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. In this study, PFS was lower in patients with TP53 mutation (13 months) compared with those not having the mutation (34 months). Moreover, the ORRs reported in trials using the ibrutinib and rituximab combination (88%) [13, 38] were slightly higher than the ORR in this study (74%); however, the trial by Wang et al. [13, 38] studying ibrutinib and rituximab had a different methodology and patients’ allocation from this study in terms of the proportion of patients with a low-risk MIPI score (44% in the study by Wang et al. vs. 16% in this trial) and the proportion of patients with refractory disease (70% in the study by Wang et al. vs. 16% in this trial). Conversely, the addition of lenalidomide to ibrutinib and rituximab might have enhanced the proportion of patients reaching CR (54%). Previous studies have reported 44%, 36%, and 19% as the achieved CR for patients receiving ibrutinib and rituximab [38], rituximab and lenalidomide (30), and ibrutinib as a single agent [28], respectively.

Combination of ublituximab and ibrutinib

A phase II clinical trial by Kolibaba et al. [10] assessed the efficacy and safety of the combination of ublituximab (TG-1101, a novel glycoengineered anti-CD-20 monoclonal antibody) and ibrutinib. Responses generally improved from the first to second assessment, with a median tumor reduction of 64% by week 8 and 82% by week 20.

Combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax

A phase II study by Tam et al. [39] assessed the efficacy and safety of the ibrutinib and venetoclax combination and compared it with historical controls. In 2019, this study was updated [14], and the median follow-up was extended to 37.5 months (1.4–45.3). The efficacy endpoints are promising in this study (Supplementary Table 3); however, this combination’s efficacy was influenced by the type of genetic aberration the patients had (Supplementary Table 3) [14].

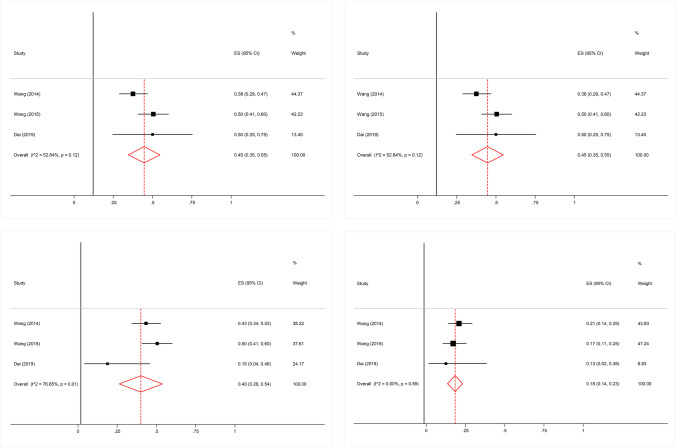

Meta-analysis of AEs: Data synthesis

Bleeding

As indicated in Fig. 2a, pooled effect size revealed that the proportion of bleeding was 45% (95% CI, 35%-55%). No significant heterogeneity was detected across the studies (I2 = 52.84%; P = 0.12). Besides, there was no evidence of publication bias among included studies (P = 0.602, Begg’s test; P = 0.791, Egger’s test) [8, 9, 25].

Fig. 2.

a Forest plot of bleeding. No significant heterogeneity was detected. No evidence of publication bias was found. b Forest plot of diarrhea. No significant heterogeneity was detected. No evidence of publication bias was found. c Forest plot of fatigue. Significant heterogeneity was detected. No evidence of publication bias was found. d Forest plot of neutropenia. No significant heterogeneity was detected. No evidence of publication bias was found

Diarrhea

As indicated in Fig. 2b, pooled effect size revealed that the proportion of diarrhea was 47% (95% CI, 37%-56%). No significant heterogeneity was detected across the studies (I2 = 47.72%, P = 0.15). Besides, there was no evidence of publication bias among included studies (P = 0.602, Begg’s test; P = 0.754, Egger’s test) [8, 9, 25].

Fatigue

As indicated in Fig. 2c, pooled effect size revealed that the proportion of fatigue was 40% (95% CI, 26%-54%). However, significant heterogeneity was detected across the studies (I2 = 76.65%, P = 0.01). Besides, There was no evidence of publication bias among included studies (P = 0.602, Begg’s test; P = 0.285, Egger’s test) [8, 9, 25].

Neutropenia

As indicated in Fig. 2d, pooled effect size revealed that the proportion of neutropenia was 18% (95% CI, 14%-23%). No significant heterogeneity was detected across the studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.59). Besides, there was no evidence of publication bias among included studies (P = 0.602, Begg’s test; P = 0.523, Egger’s test) [8, 9, 25].

Discussion

In this systematic review, we aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib as a single agent or in combination with other agents in patients with MCL by a comprehensive literature review of relevant phase II/III trials.

Generally, ibrutinib was safely and efficiently combined with a second agent in different included studies. Based on the efficacy outcomes, such as ORR and CR, the ibrutinib and rituximab [13] combination was highly effective and safe for patients with R/R MCL, with mostly tolerable AEs. The high PFS and DoR of this combination confirm this result. The data suggested that the earlier usage of ibrutinib may lead to better efficacy outcomes, and the results of the trials studying the ibrutinib and rituximab combination for patients with newly diagnosed MCL were in accordance with R/R MCL patients. Seemingly, adding lenalidomide as a third agent to ibrutinib and rituximab did not improve the efficacy outcomes significantly. However, before any decisive conclusion, more trials should be undertaken to find out more about the pros and cons of triplet combination regimens. Based on our literature review, the ibrutinib and rituximab combination had the potential of being administered as an effective and safe combination for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed MCL. Regarding safety, ibrutinib should be used with caution while considering close monitoring and risk assessment prior to prescription, especially in patients with the risk of hemorrhagic events or cardiac arrhythmias. Taking MRD-driven therapy secession, meaning discontinuation of ibrutinib therapy in case of sustained undetectable MRD after 2 years, studied by Giné et al. [27], may be considered an alternative treatment approach with a lower long-term risk of AEs while maintaining benefit administration. Administering second-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib [15, 17], with fewer hemorrhagic and cardiac risks of AEs may be another alternative in patients who are vulnerable to AEs [16]; however, suggesting these 2 alternatives was beyond the scope of our systematic literature review.

Ibrutinib has recently been introduced to the cancer treatment market, and it has not been examined in numerous large and well-designed clinical trials with different applications in various cancers. Three out of 4 trials that investigated the efficacy and safety of single-agent ibrutinib have undergone a meta-analysis [40], and the efficacy endpoints of these agents were pooled in that study. In our systematic review, trials studying ibrutinib in combination with other agents could not be pooled in a meta-analysis due to the insufficient number of homologous trials with similar arms. As a result, we were not able to conduct a meta-analysis on the efficacy outcomes of ibrutinib-containing regimens. Instead, we performed a meta-analysis on 4 of the AEs in patients with R/R MCL, which had been pooled from 3 of the single-agent ibrutinib trials.

In our literature review, we found some controversies regarding the association of baseline characteristics and traditional prognostic markers on the efficacy endpoints. Two studies [25, 30] stated that ORR was independent of the number of prior lines of therapies. Moreover, Wang et al. [25] suggested that ORR was independent of age, gender, and simplified MIPI score. Despite the ORR, Wang et al. [30] suggested that patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy and then received ibrutinib benefited more than those who received more than 1 line of therapy by achieving higher CR and showing longer DoR and PFS. The promising results of using ibrutinib as a frontline therapy for MCL patients were in accordance with this finding, suggesting that earlier use of ibrutinib may lead to better efficacy. A meta-analysis [40], which included 3 of these studies mentioned above [25, 28, 32], suggested that the ORR of patients receiving ibrutinib was high among all patients with different baseline characteristics. However, PFS and OS were dependent on baseline characteristics, such as ECOG performance status, simplified MIPI score, bulky disease, and blastoid histology. Consistent with the results of the single-agent ibrutinib trials, the trial of Jain et al. [13], which had the longest duration of follow-up and investigated the effects of the ibrutinib and rituximab combination, reported longer PFS and OS for patients with non-blastoid morphology and low-risk MIPI score. Also, Gine et al. [27] suggested that patients with high-risk MIPI had significantly lower PFS. As a result, these studies suggested that baseline characteristics and traditional prognostic markers mainly affected the endpoints such as PFS and OS rather than ORR. However, there is still a debate whether all of the baseline characteristics mentioned are prognostic for PSF and OS [11].

Besides traditional prognostic factors discussed above, some trials highlighted the association of the newer prognostic factors such as the Ki-67% index and TP53 and ATM aberrations [11, 13, 14, 27] with efficacy endpoints. Ki-67 is a nuclear cell proliferation protein that has been used as a proliferative activity index in various lymphomas, including MCL. In a trial, Jain et al. [13] studied the ibrutinib and rituximab combination in R/R MCL patients; they suggested that patients with a low Ki-67% index (< 50%) benefited more from therapy by achieving longer PFS and OS significantly compared with those with a high Ki-67% index. However, there are some controversies among assessed trials; for example, in the updated version of the trial, Wang et al. [26] studied the ibrutinib and rituximab combination in untreated MCL patients; they found no significant difference in OS among patients with high and low ki-67% indices. In newly diagnosed elderly patients receiving the ibrutinib and rituximab combination, in patients with high (≥ 30%) and low (< 30%) Ki-67% indices, PFS and OS were not significantly different [12]. In another study, PFS was significantly longer for patients without TP53 mutations compared with TP53-mutated patients receiving the ibrutinib, rituximab, and lenalidomide combination [11]. Also, DoR, PSF, and OS were higher in newly diagnosed indolent MCL patients without TP53 mutations compared with TP53 mutated patients receiving ibrutinib and rituximab [27]. Also, the response rate of patients with TP53 aberrations was lower than those without these aberrations in elderly patients receiving ibrutinib and rituximab [12]. Overall, due to the heterogeneous population of MCL patients in different studies, future studies with larger homogenous sample sizes and well-designed studies with longer duration of follow-up are recommended to identify the exact relation of prognostic factors with patients’ clinical outcomes.

Generally, single-agent ibrutinib was efficacious and safe in patients with R/R MCL, either in short-term or long-term administration. In addition to the abovementioned meta-analysis [40], the results of a trial in Japanese MCL patients [33] confirmed single-agent ibrutinib to be efficacious and well-tolerable in patients with R/R MCL. Noteworthy, in the updates of the pooled trials [8, 9, 30], the efficacy endpoints, including ORR, PFS, and OS, remained consistent with the earlier versions. In addition, no unforeseen AEs were observed in most of the updates, except for the trial of Japanese patients [8], which demonstrated an increase in hemorrhagic AEs compared to previous findings. As shown in Supplementary Table 4, AEs, such as fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea were frequently reported. Also, our meta-analysis results of the 3 studies [8, 9, 25] on single-agent ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with R/R MCL demonstrated a high frequency (40%-50%) of bleeding, nausea, and diarrhea. According to the meta-analysis mentioned above (40), the high frequency of bleeding is of great importance because most of MCL patients are elderly, and the use of anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents is common among them; as a result, careful assessment of the risk of bleeding should be made for the patients receiving ibrutinib. In conclusion, single-agent ibrutinib is efficacious and safe in short-term and long-term administration. However, close monitoring of patients with a longer duration of treatment is highly recommended to prevent serious AEs, such as hemorrhagic events.

Most of the trials included in the current review studied ibrutinib in combination with other agents. It seems that there are some reasons behind selecting ibrutinib combination therapies rather than single-agent ibrutinib by oncology researchers. The most important reasons are based on the synergic effects of chemotherapy agents to increase the chance of CR on the one hand and overcome resistance to ibrutinib by malignant cells on the other hand. Besides, some studies [13, 40] have hypothesized that a deeper response (which means achieving higher CRs) to ibrutinib therapy led to superior survival and response rate endpoints, such as an increase in DoR and PFS. However, there are some controversies regarding the association between the depth of response and superior response rates; for example, the combination of ibrutinib, rituximab, and lenalidomide [31] resulted in a deeper initial response but did not terminate to longer PFS as predicted; therefore, some doubts remain over the relation of the depths of response and efficacy endpoints such as DoR and PFS.

Most phase II/III trials that studied the effects of ibrutinib in combination with other agents in R/R MCL patients noted that treatment with combination regimens was superior to single-agent ibrutinib in terms of efficacy outcomes while tolerating AEs. These combinations included ibrutinib and rituximab (ORR: 88%; CR: 58%) [13], ibrutinib and ublituximab (ORR: 87%; CR: 33%) [10], and ibrutinib, lenalidomide, and rituximab (ORR: 74%; CR: 54%) [11]. The latter regimen increased the efficacy insignificantly compared to single-agent ibrutinib. Patients receiving the ibrutinib and rituximab combination [13] had the highest PFS (43 months, 13 months longer than single-agent ibrutinib) compared to single-agent ibrutinib, making ibrutinib and rituximab the most efficacious combination. Similar to the results of the single-agent ibrutinib trial, the prolonged use of this regimen did not cause any additional long-term toxicities, making it a great option for long-term therapy of R/R MCL patients. With the prolonged administration of the ibrutinib and rituximab combination, ORR remained the same (88%), while CR increased from 44% [28] to 58% [13], increasing the depth of response in patients. Another trial studying the ibrutinib and venetoclax combination showed a remarkably high ORR and CR (both 90%) in a subgroup of MCL patients with aberrant ATM, suggesting this combination to be studied in this subgroup in the proceeding clinical trials [14]. Generally, most ibrutinib-containing combinations showed a superior CR compared to single-agent ibrutinib in R/R MCL patients. Altogether, most of the combinations studied in phase II/III trials were efficacious and safe in R/R MCL patients [14].

Ibrutinib was approved for the treatment of patients with R/R MCL, but there were some clinical trials assessing the efficacy of this agent in untreated and newly diagnosed MCL patients. Wang et al. [26] evaluated the efficacy and safety of the ibrutinib and rituximab combination in young patients with newly diagnosed MCL, showing promising results by achieving 100% ORR in both parts of the study. Furthermore, this combination indicated a favorable efficacy in elderly patients (≥ 65 years; ORR: 96%; CR: 71%) [12] but posed a high risk of arrhythmia (22% grade 3 fibrillation) in this population due to their high cardiovascular risk factors despite the fact that patients with diseases such as atrial fibrillation had been excluded from the study. The results of these studies [12, 26] suggested that this regimen could be considered a frontline therapy for MCL patients of different range of age groups; however, precautions should be taken, especially for elderlies, due to the cardiovascular risks of ibrutinib therapy. Moreover, ibrutinib was effective and safe in previously untreated patients with indolent MCL (ORR: 84%; CR: 80%) [27]. Overall, ibrutinib-containing regimens were efficient and safe for patients with newly diagnosed MCL, as they were so in R/R MCL patients.

We systematically reviewed the latest evidence of phase II/III clinical trials. Our study was methodologically and chronologically different from previously published narrative reviews between 2014 and 2020 [15–22]. However, our results are still in line with the results of Tucker et al.’s study [22] in early 2016, suggesting that response rates of ibrutinib administration for the treatment of MCL patients may increase when combined with other chemotherapy agents. Some narrative reviews [15, 16] suggested that newer Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib, may have a better safety profile than ibrutinib due to more minor off-target effects, resulting in fewer cases of some critical side effects, including atrial fibrillation. However, comparative trials with parallel interventional groups are still lacking [18]. The disease progression while being on Bruton’s tyrosine kinase therapy and drug resistance are problems that should be addressed, and understanding resistance mechanisms is a key to finding more effective strategies to treat patients with MCL [15].

Strengths and limits

The strength of the present review is that we included all the relevant studies, including published and unpublished studies, covering the efficacy and safety of as many as possible ibrutinib-based regimens. The limitation of our work is that some of the trials we included are still ongoing, and their results are prone to change by further follow-ups.

Conclusion

Single-agent ibrutinib revealed acceptable efficacy and safety in the treatment of patients suffering from MCL. Moreover, combining ibrutinib with other agents, such as rituximab, venetoclax, and ublituximab, can increase its efficacy and reduce chemotherapy-induced resistance in most cases; however, in the case of combination therapy, patients need to be monitored more strictly in terms of AEs. In our review, the ibrutinib and rituximab combination showed promising results in patients with R/R MCL. Also, this combination showed favorable efficacy and safety in patients with newly diagnosed untreated MCL, especially in MCL patients with a low Ki-67% index. The combination of ibrutinib and rituximab is a great candidate to be studied more in large and well-designed trials. However, caution should be taken in prescribing ibrutinib for patients with high risks of bleeding or arrhythmia.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Authors’ contributions

AM designed and conceptualized the study. MR, MJ, and PHM performed the literature search and extracted data. VA, MJ, and PF helped with quality assessment. ES and ZH were in charge of the data analysis. MR, MJ, VA, PHM, and PF contributed to writing the original draft of the manuscript. AM and MR reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was part of the PharmD thesis and supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 399176).

Declarations

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved this study (code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1399.14.)

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chiang CL-L, Hagemann AR, Leskowitz R, Mick R, Garrabrant T, Czerniecki BJ, et al. Day-4 myeloid dendritic cells pulsed with whole tumor lysate are highly immunogenic and elicit potent anti-tumor responses. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Njue A, Colosia A, Trask PC, Olivares R, Khan S, Abbe A, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: a systematic literature review. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(1):1–12. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei F-Q, Sun W, Wong T-S, Gao W, Wen Y-H, Wei J-W, et al. Eliciting cytotoxic T lymphocytes against human laryngeal cancer-derived antigens: evaluation of dendritic cells pulsed with a heat-treated tumor lysate and other antigen-loading strategies for dendritic-cell-based vaccination. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dreyling M, Campo E, Hermine O, Jerkeman M, Le Gouill S, Rule S, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_4):iv62–iv71. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreyling M, Thieblemont C, Gallamini A, Arcaini L, Campo E, Hermine O, et al. ESMO Consensus conferences: guidelines on malignant lymphoma. part 2: marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):857–77. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aalipour A, Advani RH. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors and their clinical potential in the treatment of B-cell malignancies: focus on ibrutinib. Ther Adv Hematol. 2014;5(4):121–133. doi: 10.1177/2040620714539906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Claro RA, McGinn KM, Verdun N, Lee SL, Chiu HJ, Saber H, et al. FDA approval: Ibrutinib for patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma and previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(16):3586–3590. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruyama D, Nagai H, Fukuhara N, Kitano T, Ishikawa T, Nishikawa T. Final analysis of a phase II study of ibrutinib in Japanese patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2019;59(2):98–100. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.19006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang ML, Blum KA, Martin P, Goy A, Auer R, Kahl BS, et al. Long-term follow-up of MCL patients treated with single-agent ibrutinib: updated safety and efficacy results. Blood. 2015;126(6):739–745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-635326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolibaba K, Burke JM, Brooks HD, Mahadevan D, Melear J, Farber CM, et al. Ublituximab (TG-1101), a Novel Glycoengineered Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody, in Combination with Ibrutinib Is Highly Active in Patients with Relapsed and/or Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma; Results of a Phase II Trial. Blood. 2015;126(23):3980–3980. doi: 10.1182/blood.V126.23.3980.3980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerkeman M, Hutchings M, Räty R, Wader KF, Laurell A, Christensen JH, et al. Ibrutinib-Lenalidomide-Rituximab in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Final Results from the Nordic Lymphoma Group MCL6 (PHILEMON) Phase II Trial. Blood. 2020;136:36–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain P, Zhao S. Ibrutinib with Rituximab in first-line treatment of older patients with mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(2):202–212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain P, Romaguera J, Srour SA, Lee HJ, Hagemeister F, Westin J, et al. Four-year follow-up of a single arm, phase II clinical trial of ibrutinib with rituximab (IR) in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) Br J Haematol. 2018;182(3):404–411. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handunnetti SM, Anderson MA, Burbury K, Hicks RJ, Birbirsa B, Bressel M, et al. Three year update of the phase II ABT-199 (venetoclax) and ibrutinib in mantle cell lymphoma (AIM) study. Blood. 2019;13:134:756.

- 15.Bond DA, Alinari L, Maddocks K. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma: review of current evidence and future directions. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2019;17(4):223–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen C, Berinstein NL, Christofides A, Sehn LH. Review of Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(2):e233–e240. doi: 10.3747/co.26.4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bond DA, Maddocks KJ. Current Role and Emerging Evidence for Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2020;34(5):903–921. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim ES, Dhillon S. Ibrutinib: a review of its use in patients with mantle cell lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2015;75(7):769–776. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephens DM, Spurgeon SE. Ibrutinib in mantle cell lymphoma patients: glass half full? Evidence and opinion. Ther Adv Hematol. 2015;6(5):242–252. doi: 10.1177/2040620715592569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDermott J, Jimeno A. Ibrutinib for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma. Drugs Today (Barcelona, Spain : 1998) 2014;50(4):291–300. doi: 10.1358/dot.2014.50.4.2133570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanna KS, Campbell M, Husak A, Sturm S. The role of Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the management of mantle cell lymphoma. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26(5):1190–1199. doi: 10.1177/1078155220915956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker DL, Rule SA. Ibrutinib for mantle cell lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2016;12(4):477–491. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S. A: John Wiley and Sons; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M, Goy A, Martin P, Ramchandren R, Alexeeva J, Popat R, et al. Efficacy and safety of single-agent Ibrutinib in patients with mantle cell lymphoma who progressed after Bortezomib therapy. Blood. 2014;124(21):4471. doi: 10.1182/blood.V124.21.4471.4471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang M, Jain P, Yao Y, Liu Y, Zhao S, Hill H, et al. Ibrutinib Plus Rituximab (IR) Followed By Short Course R-Hypercvad/MTX in Patients (age ≤ 65 years) with Previously Untreated Mantle Cell Lymphoma - Phase-II Window-1 Clinical Trial. Blood. 2020;136(Supplement 1):35–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-137259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giné E, de la Cruz F, Ubieto AJ, Jimenez JL, García-Sancho AM, Terol MJ, Barca EG, Casanova M, de la Fuente A, Marín-Niebla A, Muntañola A. Ibrutinib in combination with rituximab for indolent clinical forms of mantle cell lymphoma (IMCL-2015): a multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(11):1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Dreyling M, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M. Ibrutinib versus temsirolimus in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10020):770–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00667-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karmali R, Abramson JS, Stephens DM, Barnes JA, Kaplan J, Winter JN, et al. Ibrutinib Maintenance (I-M) Following Intensive Induction in Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL): Efficacy, Safety and Changes in Minimal Residual Disease. Blood. 2020;136(Supplement 1):30–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-137695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rule S, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, Rusconi C, Trneny M, Offner F, et al. Ibrutinib versus temsirolimus: 3-year follow-up of patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma from the phase 3, international, randomized, open-label RAY study. Leukemia. 2018;32(8):1799–1803. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0023-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerkeman M, Eskelund CW, Hutchings M, Räty R, Wader KF, Laurell A, et al. Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, and rituximab in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (PHILEMON): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5(3):e109–e116. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, Goy A, Auer R, Kahl BS, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):507–516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maruyama D, Nagai H, Fukuhara N, Kitano T, Ishikawa T, Shibayama H, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(12):1785–1790. doi: 10.1111/cas.13076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robak T, Jin J, Pylypenko H, Verhoef G, Siritanaratkul N, Drach J, et al. Frontline bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) versus rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) in transplantation-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma: final overall survival results of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(11):1449–1458. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Visco C, Chiappella A, Nassi L, Patti C, Ferrero S, Barbero D, et al. Rituximab, bendamustine, and low-dose cytarabine as induction therapy in elderly patients with mantle cell lymphoma: a multicentre, phase 2 trial from Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(1):e15–e23. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, Walewski J, Geisler CH, Trneny M, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): long-term follow-up of the randomized European MCL elderly trial. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2020;38(3):248–256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruan J, Martin P, Christos P, Cerchietti L, Tam W, Shah B, et al. Five-year follow-up of lenalidomide plus rituximab as initial treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2018;132(19):2016–2025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-859769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang ML, Lee H, Chuang H, Wagner-Bartak N, Hagemeister F, Westin J, et al. Ibrutinib in combination with rituximab in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: a single-centre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tam CS, Anderson MA, Pott C, Agarwal R, Handunnetti S, Hicks RJ, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for the treatment of mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1211–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rule S, Dreyling M, Goy A, Hess G, Auer R, Kahl B, et al. Outcomes in 370 patients with mantle cell lymphoma treated with ibrutinib: a pooled analysis from three open-label studies. Br J Haematol. 2017;179(3):430–438. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.