Abstract

Purpose

Although rifampicin (RIF) is used as a synergistic agent for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDR-AB) infection, the optimal pharmacokinetic (PK) indices of this medication have not been studied in the intensive care unit (ICU) settings. This study aimed to evaluate the PK of high dose oral RIF following fasting versus fed conditions in terms of achieving the therapeutic goals in critically ill patients with MDR-AB infections.

Methods

29 critically ill patients were included in this study. Under fasting and non-fasting conditions, RIF was given at 1200 mg once daily through a nasogastric tube. Blood samples were obtained at seven time points: exactly before administration of the drug, and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after RIF ingestion. To quantify RIF in serum samples, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used. The MONOLIX Software and the Monte Carlo simulations were employed to estimate the PK parameters and describe the population PK model.

Results

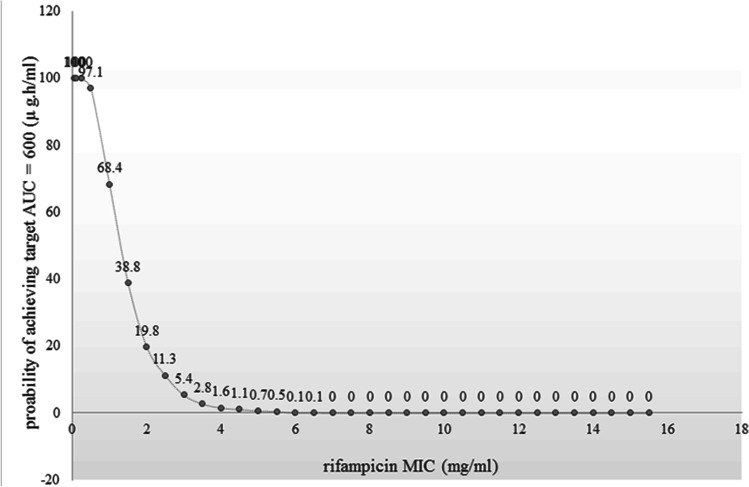

The mean area under the curve over the last 24-h (AUC0-24) value and accuracy (mean ± standard deviation) in the fasting and fed states were 220.24 ± 119.15 and 290.55 ± 276.20 μg × h/mL, respectively. There was no significant difference among AUCs following fasting and non-fasting conditions (P > 0.05). The probability of reaching the therapeutic goals at the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 4 mg/L, was only 1.6%.

Conclusion

In critically ill patients with MDR-AB infections, neither fasting nor non-fasting administrations of high-dose oral RIF achieve the therapeutic aims. More research is needed in larger populations and with measuring the amount of protein-unbound RIF levels.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Rifampin, Gram-negative Bacilli Infection, Critical Illness, Sepsis, Antimicrobial Resistance, Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter Baumanni

Introduction

Mortality in terms of antimicrobial resistance is estimated to be around 10 million cases per year by 2050 [1]; thus, the rise in resistant cases has become a global concern. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDR-AB) frequently causes life-threatening hospital-acquired infections, particularly in the intensive care units (ICUs) [2–4]. A number of studies on the eradication of MDR-AB have shown that colistin (COL) and rifampicin (RIF) combined regimens result in favorable microbiological and clinical responses [5–13]; however, contradicting outcomes have also been reported [14, 15]. The absence of in vivo pharmacokinetic (PK) investigations of RIF in MDR-AB is most likely to blame for the contradictory outcomes.

RIF is a concentration-dependent antimicrobial agent [16] and the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) indices of RIF related to the proportion of the maximum serum concentration to minimum inhibitory concentration (Cmax/MIC) and the fraction of the area under the curve (AUC) 24 h to MIC (AUC24h/MIC) [17]. The optimal Cmax/MIC ratio plays an important role to prevent antimicrobial resistance and also reduction of bacterial load [18]. Guidelines of the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) do not identify breakpoints for RIF in gram-negative bacilli, but the French Society for Microbiology (SFM) provides a RIF breakpoint for A. baumannii depending on MIC levels (sensitive to RIF if MIC ≤ 4, intermediate if 8 ≤ MIC ≤ 16, and resistant if MIC ≥ 16 mg/L) [17]. Based on time-kill and in vivo intracellular killing PK studies of RIF, and considering the fact that RIF displays greater plasma protein binding (83.8%), Jayaram et al. [19] suggested that the AUC0-24/MIC of free (unbound) RIF should be considered as a target. They observed that one log10 reduction in colony-forming unit per milliliter (CFU/mL) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis happened when AUC0-24/MIC of free (f) RIF was equal to or greater than 30 (fAUC0-24/MIC = 30). As RIF is considered a concentration-dependent antibiotic, Cmax/MIC ≥ 8–10 of free RIF was considered a predictor of successful treatment [17, 20].

Several studies have reported that the 600 mg per day of oral RIF was sub-therapeutic in the majority of patients with Tuberculosis (TB), and suboptimal Cmax levels reached [15, 21, 22]. Better results were reported with the oral dose of 1200 mg per day for TB [15, 23]; and also promising results in terms of the addition of an intravenous 20 mg/kg/day (approximately 1200 mg per day) RIF dose were reported for MDR-AB infections [24, 25]. Considering the absorption, bioavailability, and exposure of intravenous and oral RIF increase nonlinearly with an increase in dose [26], and since the intravenous form of RIF is not widely available in ICUs of many countries, an oral 1200 mg per day as once daily dose was selected and evaluated as a high dose for MDR besides the 600 mg per day (10 mg/kg/day) standard care [27, 28]. Although cohort studies on high doses of RIF (i. e. 900 to 2400 mg/day) had confirmed its safety and tolerability [29, 30], thoughtful monitoring of any related hepatic adverse effects and other probable complications was considered during the study to provide patients’ safety.

The intubated patients in ICUs usually receive the oral medications via a nasogastric (NG) tube. Absorption of drugs via feeding tube shows a variable profile and sometimes is not similar to the oral route [31]. Drug absorption may be affected by the eating state, which alters stomach emptying, gastrointestinal pH, bile flow into the intestine, and the formation of bile micelles [32, 33].

The present study aimed to evaluate PK of high dose oral RIF following intragastric administration under fasting versus fed conditions to achieve target concentrations.

Methods

Study design, participants, and setting

This was a prospective, observational study conducted at ICUs of Sina Hospital, affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). The study was carried out between January 2020 and September 2021. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Sina Hospital and TUMS (IR.TUMS.SINAHOSPITAL.REC.1399.120 and IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.808). Considering intubated patients’ unconsciousness, a written informed consent was obtained from the closest patient’s relative (legally acceptable representative) or legal guardian in the hospital. Adult patients who met all of the aspects of the following inclusion criteria were enrolled in the current study: (i) the presence of at least one positive blood culture for any strains of MDR-AB (defined as being resistant to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial classes) [34], (ii) suspicion of sepsis or septic shock based on 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines [35], and (iii) tolerance of enteral nutrition (EN) for at least 24 h. Patients with any of the conditions of (i) pre-existing severe liver impairment (class C of Child–Pugh classification) [36], (ii) an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 30 mL/min (based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation [37]), (iii) pregnancy, (iv) body mass index (BMI) of less than 18 or greater than 35 kg/m2, (v) a history of RIF receiving for more than a week before entering into the study, (vi) tobacco smoking, (vii) coadministration of drugs that can affect the PK of RIF, such as strong CYP3A4 inducers or avoided combinations with risk X [38], or (viii) fingerstick blood glucose levels less than 110 mg/dL during the fasting period were excluded from the study. To investigate PK parameters of RIF in terms of different feeding conditions (fasting (F) and non-fasting (NF) conditions), all included patients received 1200 mg of RIF (Hakim Pharmaceutical, Iran) as a single dose each day, via nasogastric (NG) tube, and over two consecutive days as F and NF condition, sequentially. Thus, F state was investigated at the beginning and as the first day and NF investigation was performed as the second day and immediately after. In the F state, patients were deprived of nutritional solutions from 12 a.m. to 6 a.m., then took RIF and fasted for up to two hours after taking the medication. For F state extemporaneous formulations of RIF, suspensions were prepared by trituration of four 300 mg RIF capsules in 120 mL of simple syrup (standard sugar solution without flavor or medication, made up of 85% w/v of sucrose and purified water) [39], as the manufacturer had recommended for preparation of oral solutions [40]. The liquid was prepared immediately before the administration time for each patient and delivered by feeding tube, subsequently. In the NF state, ingredients of four 300 mg RIF capsules were completely dispersed in 150 mL of standard Enterameal (Karen Pharma, Iran, containing 5.4 g of protein, 20.2 g of carbohydrate, and 5.4 g of fat) liquid preparation and then administered via feeding tube. In both conditions, after administration of RIF, the NG tube was flushed with 50 mL of warm tap water to inhibit clogging.

Sample collection

Serial blood samples were obtained at seven time points: exactly before administration of the drug and 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h from witnessed RIF intake. Patient’s blood samples (2 mL per sample) were collected from the central venous catheter (CVC) in accelerating clot formation tubes (Eurotubo Serum Separation) and centrifuged for 5 min at 6000 revolutions per minute (rpm). Subsequently, the separated plasmas were frozen in microcentrifuge tubes (MAXWELL) at -80 °C until analysis.

Bioanalysis

The plasma concentrations of RIF and 25-O-desacetylrifampicin (dRMP) were both measured by protein precipitation followed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection. The method was established and validated in our laboratory by testing different portions of solvents and various methods of extraction for the optimized condition of the simultaneous assessment of RIF and dRMP. Six hundred microliters of acetonitrile, 30 μl ascorbic acid solution (33 mg/mL) as an antioxidant, and 15 μl of p-nitropropionanilide solution (1.24 mg/mL) as internal standard were added to 300 μl of plasma sample. The mixture was vortexed for 10 min and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. Then, 700 μl of the clear supernatant went into the process of solvent-evaporation by heating up to 37 centigrade degrees. Finally, 700 μl of 1:1 water–methanol solution was added for reconstitution. One hundred microliters of the final solution were injected into the HPLC Waters associates system, which consisted of a Hector-M C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) protected with a Ultisil XB guard column (10 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm), with Knauer Diode array detector (K-2800) and Knauer injector with 100 μl capacity. The mobile phase consisted of 0.05 M potassium dihydrogen phosphate (pH 2.6) and acetonitrile (54%-46% [vol/vol]). The flow rate was set at 1 mL/min, and the UV detection was performed at both wavelengths of 334 and 472 nm for the omission of intervening peaks. The method validated for selectivity, accuracy, precision, and calibration curve on the basis of FDA guideline for validation of bioanalytical methods. Ordinary linear regression analysis was used to determine the method's linearity, with correlation coefficients (r2) of 0.999 and 0.9998 for RIF and dRMP at 334 nm and across the range of 0.1 to 4.8 g/mL, respectively, and 0.9968 for both RIF and dRMP over the range of 4.8 to 40 g/mL. The amounts are 0.9996, 0.9991, 0.993, and 0.9911 for the other wavelength, respectively. The accuracy of standard concentrations was 99 4% for RIF and 100 3% for dRMP, at the wavelength of 334 nm and 99 3% and 99 8% for dRMP, at the wavelength of 472 nm over the concentration range of 0.1 to 40 μg/mL. The intra and inter-day precision were less than 15% for RIF and dRMP. The lower limits of quantitation (LoQ) were 0.1 for both the drug and its metabolite according to signal-to-noise ratio calculations. The reported stability of rifampicin-containing plasma samples at 20 °C and 80 °C was at least 16 months with less than 5% loss without antioxidants [41], and the stability for standard plasma concentrations of RIF and dRMP with 1.048 mg/mL of ascorbic acid was observed during 5 h at room temperature and after 24 h at 20 °C with less than 4% loss. Concentrations were expressed in mg/L for the parent drug and its metabolite.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive study was performed among the planned sample size of 29 patients (calculated with Cochran’s formula for a confidence level of 95% [42]) in both F and NF conditions with hypothesis testing. To explain the normal distribution, a one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used for all PK parameters. After that, non-compartmental methods for P values less than 0.05 and compartmental methods for P values more than 0.05 were employed to define the parameters. Likewise, equality of means was tested with t test and Levene's test was done to describe the equality of variances. Moreover, F versus NF states were tested with the independent-samples t test, and a geometric mean ratio and 95% confidence interval was calculated for every comparison. All statistical evaluations were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 26, and GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1.471 was used for describing the parameters. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Population pharmacokinetics modeling

A nonlinear mixed-effects modeling approach was selected due to the best plots’ match. Data were analyzed using the software program MONOLIX (MonolixSuite 2021 release, version 2021R1). RIF PK parameters were estimated using the stochastic approximation expectation–maximization (SAEM) and structural model. For better model development, outlier findings (4 days from a total of 58 days of sampling) were censored. Due to the presence of a double-peak in many of the concentration–time curves, double-absorption was chosen and tested in addition to the other absorption models available in the MONOLIX library. MONOLIX library of double-absorption models contains all the combinations for mixed absorptions with different types and delays. Depending on the best match, the first absorption was selected to be first order (modeled with the parameter ka1) and with no delays. The second absorption was selected to be first order (modeled with the parameter ka2) but with a lag-time for the absorption process, modeled with the parameter Tlag2. Therefore, the order of RIF absorption was found to be “sequential”. RIF distribution was one-compartmental and “V” is defined as the volume of the central compartment. Elimination of RIF was linear and defined by Cl (as clearance). The absorbed fraction of the drug transferred into the central compartment (defined as “F1”) with random variability defined as “Ω”. Thereafter, the main PK parameters of RIF such as the area under the curve from the time of dosing over the last 24-h (AUC0-24), maximum observed concentration (If not unique, then the first maximum is used) (Cmax), time to reach maximum plasma concentration (Tmax), the plasma half-life (t1/2), estimated volume of distribution following oral administration (Vd), and mean residence time extrapolated to infinity using predicted Clast (MRT∞) were estimated by MONOLIX using the SAEM algorithm. For describing the metabolite, observed AUCs from dosing to the time of the last measured concentrations (AUClast) were determined for both RIF and dRMP by non-compartmental analysis (NCA) using MONOLIX, under both F and NF conditions. Concentrations-time curves were examined and a visual predictive check (VPC) was used to evaluate the performance of the PK model as a diagnostic tool [43]. Residual error, goodness-of-fit plots, VPC, and objective function value (OFV) were used to verify the model [44]. For the distribution of the residuals, individual weighted residuals (IWRES) tests were used. Individual parameters were used to calculate IWRES tests. Finally, doses were simulated for 1000 participants using Monte Carlo simulations to attain a minimum target plasma concentration of 32–40 mg/L (due to the maximum MIC of 4 mg/L and Cmax/MIC of ≥ 8–10 for the free fraction of RIF as a predictor of successful treatment of RIF-sensitive A. baumannii, as mentioned before).

Results

A total of 36 eligible patients met all the inclusion criterion during the study period from which, seven were excluded due to missing of one of the sampling days (in result of patient’s death or discharge) (6 patients) and refusal to participate (1 patient). Demographics, physiological indicators at baseline, and received medications that could affect the PK parameters of the included patients at the beginning of each day are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of included patients (N = 29)

| Value | Variable | |

|---|---|---|

| NFb | Fa | |

| Age (years) [median (range)] | 55 (27–81) | 55 (27–81) |

| BMIc (kg/m2) [mean ± SDd] | 24.6 ± 2.6 | 24.6 ± 2.6 |

| Total daily dose of RIF (mg/kg) [mean ± SD] | 16.8 ± 1.9 | 16.8 ± 1.9 |

| eGFRe [mean ± SD] | 67.1 ± 26.7 | 65.9 ± 24.8 |

| Intake fluids (mL) [mean ± SD] | 3098 ± 976 | 3188 ± 811 |

| Output fluids (mL) [mean ± SD] | 2895 ± 781 | 2933 ± 978 |

| MAPf (mmHg) [mean ± SD] | 71.9 ± 8.8 | 73.4 ± 9.3 |

| SOFAg score [mean ± SD)] | 7.1 ± 2 | 6.3 ± 2 |

| Child Pugh score [mean ± SD] | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 1.3 |

| Medications | ||

| Vasopressor (%) | 19/29 (65.5) | 19/29 (65.5) |

| PPIh (%) | 20/29 (68.9) | 20/29 (68.9) |

| Sedative-analgesic medications (%) | 25/29 (86.2) | 25/29 (86.2) |

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 20/29 (68.9) | 20/29 (68.9) |

| Postoperative (%) | 14/29 (48.3) | 14/29 (48.3) |

| Length of ICU stay (day) [median (range)] | 13 (7–92) | 13 (7–92) |

aF: fasted; bNF: non-fasted (fed); cBMI: body mass index; dSD: standard deviation; eeGFR: estimated glomerular filtration; fMAP: mean arterial pressure; gSOFA: sequential organ failure assessment; hPPI: proton pump inhibitor

Finally, 406 serum samples from 29 patients were available for evaluation of PK parameters (Table 2).

Table 2.

RIF PK parameters estimated using the SAEM

| Value | Stochastic Approximation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S.E.a | R.S.E. (%)b,c | ||

| Fixed Effects | |||

| ka1popd,e (hr−1) | 1.1 | 0.22 | 19.9 |

| ka2popf (hr−1) | 0.46 | 0.094 | 20.6 |

| F1pop | 0.68 | 0.25 | 37.2 |

| Tlag2poph (hr) | 2.92 | 4.46 | 153 |

| Vpopi (L/kg) | 0.68 | 0.022 | 3.19 |

| Clpop (L/hr) | 0.08 | 0.0061 | 7.58 |

| Standard Deviation of the Random Effects | |||

| Ωj ka1 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 18.2 |

| Ω ka2 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 39.3 |

| Ω F1g | 3.57 | 1.06 | 29.6 |

| Ω Tlag2 | 2.99 | 1.49 | 49.7 |

| Ω V | 0.097 | 0.048 | 49.5 |

| Ω Cl | 0.52 | 0.057 | 11 |

| Error Model Parameters | |||

| A& | 0.49 | 0.05 | 10.2 |

| B& | 0.15 | 0.019 | 12.6 |

aS.E.: standard error; bR.S.E.: relative standard error; cRSE%: relative standard error percentage; dPop: population parameter; eka1: first-order absorption rate constant from the first site; fka2: first-order absorption rate constant from the second site; gF1: absorbed fraction from the first site; hTlag2: delay for the second absorption; iV: volume of the central compartment; jΩ: random variability; & A and B: residual error components

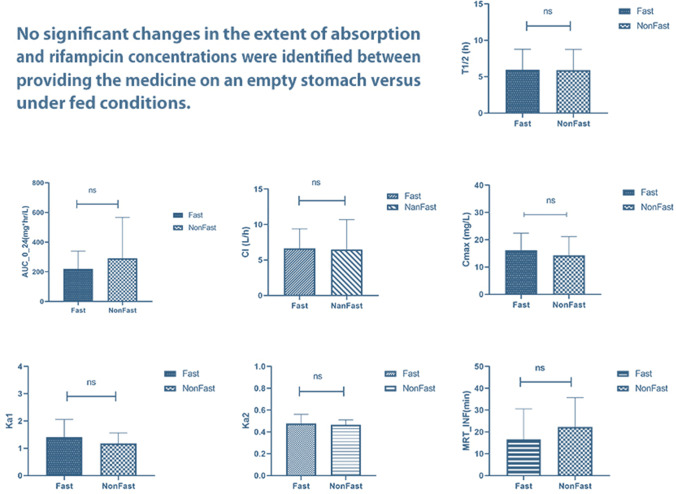

The estimated values for the main PK parameters are shown in Table 3. According to the determined P values, the differences between the two groups were not significant for any of the parameters due to the criterion. The distribution of AUC0-24, Cmax, Tmax, T1/2, Ka1, Ka2, Vd, CI, MRT∞, eGFR, and fluid intake were non-normal but the volume of fluid output had a normal distribution.

Table 3.

RIF PK parameters were estimated using the SAEM, after obtaining an oral dose of 1200 mg RIF both in F and NF states during once-daily administration according to the model

| Parameter | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fa | NFb | P-Value | |

| AUC0-24c (μg × h/mL) [mean ± SD] | 220.24 ± 119.16 | 290.55 ± 276.20 | 0.216 |

| Cmaxd (mg/L) [mean ± SD] | 16.11 ± 6.30 | 14.29 ± 6.85 | 0.298 |

| T1/2e (hr) [mean ± SD] | 5.94 ± 2.84 | 5.91 ± 2.85 | 0.963 |

| Tmaxf (hr) [mean ± SD] | 3.84 ± 2.96 | 3.00 ± 2.10 | 0.214 |

| ka1h (hr−1) [mean ± SD] | 1.40 ± 0.65 | 1.18 ± 0.38 | 0.114 |

| ka2h (hr−1) [mean ± SD] | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 0.484 |

| Vdi (L/kg) [mean ± SD] | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 0.621 |

| Clj (L/h) [mean ± SD] | 6.66 ± 2.74 | 6.49 ± 4.20 | 0.860 |

| MRT∞g [mean ± SD] | 16.59 ± 13.98 | 22.27 ± 13.48 | 0.121 |

aF: fasted; bNF: non-fasted (fed); cAUC0-24: area under the curve from time zero to the last 24-h; dCmax: greatest serum concentration; eT1/2: half-life; fTmax: time it takes for a drug to reach the greatest concentration; gMRT∞: the mean residence time; hk: elimination constant rate; iVd: volume of distribution; jCl: clearance of rifampicin; &SD: standard deviation

Model evaluation and validation

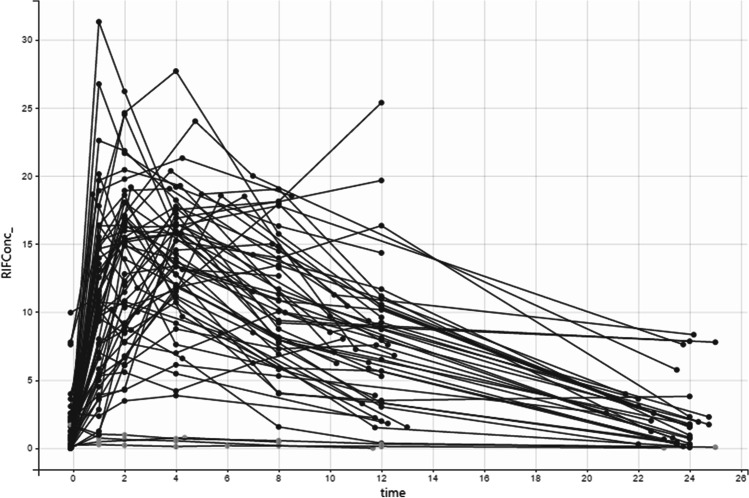

Figure 1 shows the time-concentration graph of RIF. The mechanisms of absorption, distribution, and excretion of RIF in the body were totally compatible with the one-compartmental model, based on observed plasma concentrations of RIF.

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic plot: Observed plasma RIF concentrations represented as RIFConc (rifampicin concentrations) (mg/mL) versus time (hour)

Figure 2 (VPC) indicated that the average prediction was compatible with time-concentration periods and the changeability was sensibly evaluated. VPC indicated that the model was able to reflect the average orientation (50th percentile) and in addition to the variability (10th and 90th percentiles). Outliers are highlighted with dots and dark-gray areas.

Fig. 2.

VPC of RIF PK model for RIFConc (rifampicin concentrations) versus time (hour) based on Monte Carlo 1000 simulation and the VPC with the forecast interims for the 10th (middle-gray lower range), 50th (light-gray central zone) and 90th (middle-gray upper zone) percentiles. Percentiles are compared with the 10th, 50th, and 90.th empirical percentiles (solid lines)

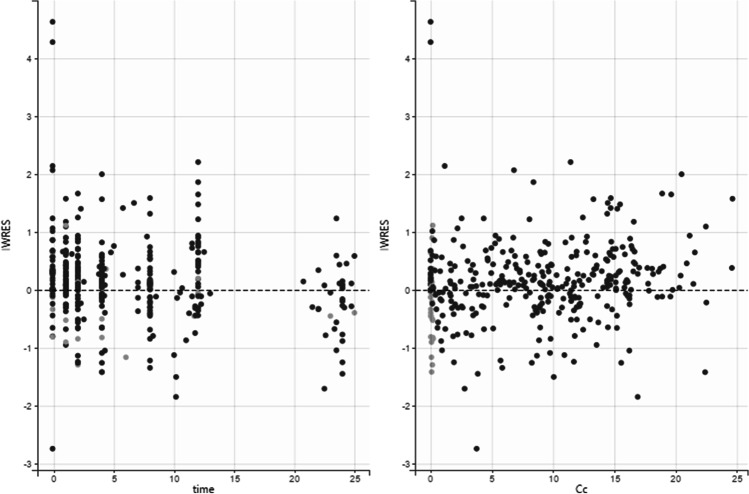

Distribution of the residuals

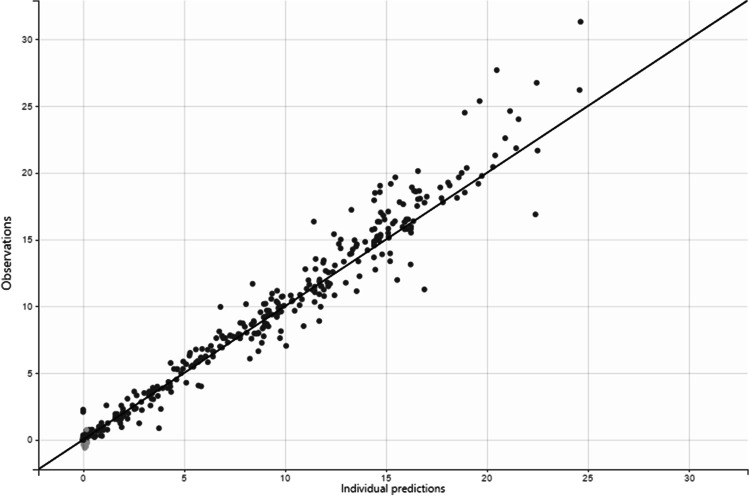

There was a fit between the estimated PK model and the observed data. Scatter plots of IWRES vs. time/RIF concentration are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Diagnostic plots: Scatter plots of IWRES with respect to time and predicted Cc (plasma rifampicin concentration) for oral RIF

Dose simulations

Figures 4, 5 depicts simulated plasma concentrations of 1200 mg RIF once daily using Monte Carlo techniques, clearly demonstrating that this dose regimen fails to achieve the minimum target plasma concentration of 32–40 mg/L in the steady-state.

Fig. 4.

Goodness-of-fit plots for final population models of RIF, observed and predicted concentrations vs. time

Fig. 5.

Prediction Cc (rifampicin concentration) time (hour) distribution. 1200 mg doses were simulated using Monte Carlo simulations in order to achieve a minimum targeted plasma concentration of 40 mg/L. Dashed lines corresponded to the dose of 1200 mg/day of RIF

In Fig. 6, doses were simulated using Monte Carlo simulation with n = 1000 patients per simulation in order to achieve a minimum AUC0-24 of 600 μg × h/mL. As shown, by administering 1200 mg of RIF, the probability of reaching the target at MIC of 4, was only 1.6%.

Fig. 6.

Probability of targeted AUC attainment for 1000 simulated subjects when RIF is administered at 1200 mg every 24 h in critically ill patients

PK analysis of dRMP (NCA)

The AUClast ratio (mean ± SD) of dRMP to RIF under F and NF conditions were 0.25 ± 0.16 and 0.26 ± 0.18, respectively.

Discussion

The present study showed that the high-dose oral regimen of RIF at 1200 mg once daily (16 mg/kg/day) fails to achieve the therapeutic goals in critically ill patients with carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii. This finding was in line with Lepe et al. [17] study which had estimated the probability of achievement of the RIF’s therapeutic targets (unbound Cmax/MIC = 10 and fAUC0-24/MIC = 30) at doses of 10 mg/kg/day and 20 mg/kg/day for A. baumannii clinical isolates (in which the population was not specified to be critically ill) as 0.2% and 0.6%, respectively. Since PK targets for RIF in A. baumannii treatment is still unknown, goals were adapted from PK studies of RIF in patients with TB [19]. As it was mentioned before, the fAUC0-24/MIC = 30 of RIF can be considered as a therapeutic indicator based on the time-kill and in vivo intracellular killing PK studies of RIF, due to both Jayaram et al. [19] and Lepe et al. [17]. Considering the average protein-binding of 80% for RIF which represents a free fraction of 20%, and MIC of at least 4 for the RIF-sensitive A. baumannii, the fAUC0-24 was calculated to be at least 120 μg × h/mL as the 0.2 portion, thus the overall AUC0-24 of 600 μg × h/mL was chosen as the target in this study. It was clearly shown that by administering 1200 mg of RIF, the probability of reaching the target at MIC of 4, was only 1.6% which was not surprising due to other similar studies. Wasserman et al. [45] investigated varying values of the AUC0-24 owing to different doses and modes of administration of RIF (10 mg/kg and 35 mg/kg oral vs. 20 mg/kg intravenous doses) in a recent randomized PK study. The mean AUC0-24 levels of RIF were found to be 42.9, 295.2, and 206.5 μg × h/mL, respectively. According to that research, even the 20 mg/kg/day administered intravenous or the 35 mg/kg/day of the oral route were not high enough to achieve the targeted AUC0-24 of 600 μg × h/mL. This also reflects the non-linear and more than proportional increase in the AUC0-24 of RIF with the proportional increase in the oral dose of the drug, which was in line with the findings of Rao PS and co-workers’ population PK study, with the reported average AUC0-24 of 108.8 due to a 35 mg/kg of oral dose [46]. Based on recent reports by Te Brake el al [47], the AUC0-24 for the 50 mg/kg daily dose of RIF, ranged between 320 to 995 μg × h/mL with the mean value of 571 μg × h/mL, which was close to this paper’s target, but not well tolerated.

Food is known to affect oral drugs’ absorption by affecting gastric emptying time and pH, stimulating bile flow and splanchnic blood flow, or physically interacting with medications [48]. Food has been found in a number of trials to delay and reduce the amount of RIF absorbed following oral administration [49–53]. Van Scoy and Wilkowske, on the other hand, stated that the difference observed in PK parameters was not clinically significant [54]. Verbist and Gyselen also reported that although the Cmax of RIF after an oral dose administered on an empty stomach was greater, it was not significantly higher than the fed condition [55]. While same results were reported by Peloquin et al. [56], it is suggested that as RIF is lipid-soluble, the conflicting reports can be in terms of variation in the lipid content of the meals administered during the fed state. Among four investigations with nearly 600-kilocalories-containing meals, RIF plasma concentrations decreased by about 50%, 22%, and 11% with three high carbohydrate diets [51–53], and the only significant difference between the effect of the two carbohydrate and lipid-rich diets was the later Cmax occurred in the carbohydrate-rich diet as compared to the lipid-rich [51], suggesting that the rate of absorption from the gut may be affected by the amount of fats in the food. In this trial, no significant changes in the extent of absorption and RIF concentrations were identified between the two feeding states also suggesting that some other variables, such as the patients' poor nutritional status, the presence of sepsis-related inflammations, which may affect the intestinal mucosa and limit medication absorption, and delayed gastric emptying, which likely affects the gastric pH, might have influenced the overall findings [53, 57]. The majority of our patients received PPIs, vasopressors, and sedative analgesic medications which caused significant changes in gastric emptying and pH led to effect on drug absorption [58–62]. The portion of the drug administered via NG tube which actually reaches the stomach is another difference in case of administration methods in the present study while other studies have mostly been conducted using oral doses taken by mouth. This should be considered for all of the other PK characteristics in this study.

The dual-peak phenomenon is commonly caused by a delay in gastric emptying, changes in gastric pH, enterohepatic recirculation, the occurrence of two drug-absorption sites, and the administration of large drug doses [63–66]. Commonly used medications in our patients including opioids and PPIs are the main reasons for this phenomenon which can cause upper and lower gastrointestinal dysmotility and increase the gastric pH respectively [58]. Besides, RIF itself has an enterohepatic cycle which can independently lead to sequential absorption and dual-peak [67].

The importance of PK/PD optimization approaches for antimicrobials’ dosing in sepsis has been stressed in guidelines, including the last revision of International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock [68, 69]. Lack of clinical understanding of RIF's PK/PD against resistant A. baumannii might be one of the reasons for treatment failure in clinical studies [70]. Regarding the last guideline of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, mono-therapy is not recommended in moderate to severe carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii infection due to limited clinical data supporting the effectiveness and COL has been investigated as one arm of the two-drug combination, with or without RIF, in this case [71]. The guideline has mentioned the combination due to numerous studies based on the principles supporting that COL and RIF have synergic effects against A. baumannii, described by bioavailability model (i. e. COL may damage the outer membrane and facilitates RIF entry, thus amplifies its binding to the A. baumannii’s RNA-polymerase [72, 73]). Aydemir et al. evaluated the effect of COL vs. a combination of COL and RIF on the mortality in treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and reported no significant difference in microbial responses between the two groups [74]; but the results were expected as the MICs of eleven patients was quite resistant to RIF; and synergistic effects for the combination does not happen in resistant cases in terms of rpoB-gene-mediated mutations [8]. Moreover, they administered 600 mg per day of RIF via NG tube, while this oral dose resulted in sub-therapeutic levels in more than half of the patients, based on the findings of Koegelenberg et al. [75]. Durante-Mangoni and colleagues also investigated the effect of COL and RIF in combination on the 30-day mortality of critically ill patients with infections caused by extensively drug-resistant (XDR) A. baumannii, and as the MICs were greater than 16 mg/L in 43 percent of the patients again, the findings were not surprising [14]. Therefore, despite the type of the infection being VAP among a wide range of the patients in that study, the administrated dose of COL was sub-therapeutic for that as the administration of a 2-million-international-units of COL every 8 h could not provide the adequate plasma and broncho-alveolar therapeutic concentrations [76] as Cheah S-E et al. indicated that the most important PK indicator of the optimal effect of COL was the fAUC/MIC and the ratio of 7.4–17.6 is necessary to achieve a two log10 reduction in A. baumannii load and 3.5–13.9 for one log10 reduction [77]. Moreover, Tsuji et al. stated that an AUC0-24 of approximately 50 mg × h/L for COL at the steady-state was insufficient in the VAP treatment [78]. So in the Durante-Mangoni and co-workers clinical trial, PK/PD optimization approaches in dosing of COL and RIF were not taken into account. The last update of the Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance [71] has advised against the use of RIF as a part of combination therapy based on the three mentioned clinical trials’ results in which almost none of the COL and RIF doses were not optimal [10, 14, 74]. As it is important to choose the right method to check the A. baumannii’s sensitivity to RIF [8], according to Varshochi et al. [79], the Epsilometer test (E-test) had a more diagnostic value compared to the other methods such as disk diffusion and agar dilution; so routine performance of the E-test before adding RIF to the therapeutic regimen is recommended. Because the optimum doses for both medications were not included in any of the current studies, our analysis advises that further clinical trials focusing on PK/PD dosing optimization be conducted.

Study limitations

This study had some limitations such as the sample size which was relatively small and the point that many factors can potentially affect the process of metabolism, absorption, and excretion of RIF in the critically ill patients, that it not possible to be exactly measured. Furthermore, the amount of protein-unbounded portion of RIF in the blood could not be measured for this study.

Conclusion

A high-dose oral regimen of RIF at 1200 mg daily may not be high enough to achieve therapeutic levels for MDR-AB infections in critically ill patients and at least a 50 mg/kg/day of the drug is required to reach the minimum AUC0-24 of 600 μg × h/mL [47] and the greater probability of reaching the target at MIC of 4 (This higher dose is suggested to been studied with divided administration, due to the reported intolerance). Furthermore, it may be suggested that there is no need to withhold nutritional solutions from ICU patients when administering RIF, since no significant differences in PK parameters were seen between providing the medicine under F vs. NF conditions, in this small group. Further studies are required.

Acknowledgements

This endeavor would not have been possible without the generous support from Dr. Maryam Taghizadeh-Ghehi, the assistant professor of clinical pharmacy, who accompanied during designing the study. Deepest gratitude is expressed to Dr. Maryam Dibaei, PhD student of pharmaceutics, for her enlightening guidance during bioanalysis.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Research Center for Rational Use of Drugs, Tehran University of Medical Sciences for financial support of the project.

Declarations

Competing interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hossein Karballaei-Mirzahosseini, Romina Kaveh-Ahangaran, Atabak Najafi and Arezoo Ahmadi These authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.O'Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Government of the United Kingdom. 2016. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016-05/apo-nid63983.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr 2022.

- 2.Vázquez-López R, Solano-Gálvez SG, Juárez Vignon-Whaley JJ, Abello Vaamonde JA, Padró Alonzo LA, Rivera Reséndiz A, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii resistance: a real challenge for clinicians. Antibiotics. 2020;9(4):205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Pogue JM, Zhou Y, Kanakamedala H, Cai B. Burden of illness in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in US hospitals between 2014 and 2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Nguyen M, Joshi SGJJoAM. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii, and their importance in hospital-acquired infections: a scientific review. J Appl Microbiol. 2021;131(6):2715–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Armengol E, Asunción T, Viñas M, Sierra JM. When combined with colistin, an otherwise ineffective rifampicin–linezolid combination becomes active in Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms. 2020;8(1):86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bai Y, Liu B, Wang T, Cai Y, Liang B, Wang R, et al. In vitro activities of combinations of rifampin with other antimicrobials against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2015;59(3):1466–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Lee HJ, Bergen PJ, Bulitta JB, Tsuji B, Forrest A, Nation RL, et al. Synergistic activity of colistin and rifampin combination against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57(8):3738–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Nordqvist H, Nilsson LE, Claesson C. Mutant prevention concentration of colistin alone and in combination with rifampicin for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(11):1845–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Oh S, Chau R, Nguyen AT, Lenhard JR. Losing the battle but winning the war: Can defeated antibacterials form alliances to combat drug-resistant pathogens? Antibiotics. 2021;10(6):646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Park HJ, Cho JH, Kim HJ, Han SH, Jeong SH, Byun MK. Colistin monotherapy versus colistin/rifampicin combination therapy in pneumonia caused by colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: A randomised controlled trial. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;17:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Scudeller L, Righi E, Chiamenti M, Bragantini D, Menchinelli G, Cattaneo P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro efficacy of antibiotic combination therapy against carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;57(5):106344. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Petrosillo N, Ioannidou E, Falagas ME. Colistin monotherapy vs. combination therapy: evidence from microbiological, animal and clinical studies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(9):816–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Tuon FF, Rocha JL, Merlini AB. Combined therapy for multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection–is there evidence outside the laboratory? J Med Microbiol. 2015;64(9):951–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Durante-Mangoni E, Signoriello G, Andini R, Mattei A, De Cristoforo M, Murino P, et al. Colistin and rifampicin compared with colistin alone for the treatment of serious infections due to extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(3):349–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Goutelle S, Bourguignon L, Maire PH, Van Guilder M, Conte Jr JE, Jelliffe RW. Population modeling and Monte Carlo simulation study of the pharmacokinetics and antituberculosis pharmacodynamics of rifampin in lungs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(7):2974–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Gumbo T, Louie A, Deziel MR, Liu W, Parsons LM, Salfinger M, Drusano GL. Concentration-dependent Mycobacterium tuberculosis killing and prevention of resistance by rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(11):3781–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Lepe JA, García-Cabrera E, Gil-Navarro MV, Aznar JJ. Rifampin breakpoint for Acinetobacter baumannii based on pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models with Monte Carlo simulation. Revista Española de Quimioterapia. 2012;25(2). [PubMed]

- 18.Rolain JM, Diene SM, Kempf M, Gimenez G, Robert C, Raoult D. Real-time sequencing to decipher the molecular mechanism of resistance of a clinical pan-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolate from Marseille, France.Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(1):592–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Jayaram R, Gaonkar S, Kaur P, Suresh B, Mahesh B, Jayashree R, et al. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of rifampin in an aerosol infection model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(7):2118–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Regoes RR, Wiuff C, Zappala RM, Garner KN, Baquero F, Levin BR. Pharmacodynamic functions: a multiparameter approach to the design of antibiotic treatment regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(10):3670–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ramachandran G, Chandrasekaran P, Gaikwad S, Agibothu Kupparam HK, Thiruvengadam K, Gupte N, et al. Subtherapeutic rifampicin concentration is associated with unfavorable tuberculosis treatment outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(7):1463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Perea-Jacobo R, Muñiz-Salazar R, Laniado-Laborín R, Cabello-Pasini A, Zenteno-Cuevas R, Ochoa-Terán A. Rifampin pharmacokinetics in tuberculosis-diabetes mellitus patients: a pilot study from Baja California, Mexico. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2019;23(9):1012–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Loubinoux J, Mihaila-Amrouche L, Le Fleche A, Pigne E, Huchon G, Grimont PAD, et al. Bacteremia caused by Acinetobacter ursingii. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(3):1337–1338. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1337-1338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassetti M, Repetto E, Righi E, Boni S, Diverio M, Molinari MP, et al. Colistin and rifampicin in the treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(2):417–420. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motaouakkil S, Charra B, Hachimi A, Nejmi H, Benslama A, Elmdaghri N, et al. Colistin and rifampicin in the treatment of nosocomial infections from multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Infect. 2006;53(4):274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svensson RJ, Aarnoutse RE, Diacon AH, Dawson R, Gillespie SH, Boeree MJ, Simonsson US. A population pharmacokinetic model incorporating saturable pharmacokinetics and autoinduction for high rifampicin doses. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2018;103(4):674–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Cresswell FV, Meya DB, Kagimu E, Grint D, te Brake L, Kasibante J, et al. High-Dose Oral and Intravenous Rifampicin for the Treatment of Tuberculous Meningitis in Predominantly Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Positive Ugandan Adults: A Phase II Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(5):876–884. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz-Bedoya CA, Mota F, Tucker EW, Mahmud FJ, Reyes-Mantilla MI, Erice C, et al. High-dose rifampin improves bactericidal activity without increased intracerebral inflammation in animal models of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Investig. 2022;132(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Garcia-Prats AJ, Svensson EM, Winckler J, Draper HR, Fairlie L, van der Laan LE, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of high-dose rifampicin in children with TB: the Opti-Rif trial. 2021;76.46-3237:(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Seijger C, Hoefsloot W, Bergsma-de Guchteneire I, te Brake L, van Ingen J, Kuipers S, et al. High-dose rifampicin in tuberculosis: Experiences from a Dutch tuberculosis centre. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0213718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu LL, Zhou Q. Therapeutic concerns when oral medications are administered nasogastrically. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38(4):272–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Lindahl A, Ungell AL, Knutson L, Lennernäs H. Characterization of fluids from the stomach and proximal jejunum in men and women. Pharm Res. 1997;14(4):497–502. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Cheng L, Wong H. Food effects on oral drug absorption: application of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling as a predictive tool. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(7):672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, Kumar A, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Albers I, Hartmann H, Bircher J, Creutzfeldt W. Superiority of the Child-Pugh classification to quantitative liver function tests for assessing prognosis of liver cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24(3):269–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YC, Park JY, Kim B, Kim ES, Ga H, Myung R, et al. Prescriptions patterns and appropriateness of usage of antibiotics in non-teaching community hospitals in South Korea: a multicentre retrospective study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022;11(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Baniasadi S, Shahsavari N, Namdar R, Kobarfard F. Stability assessment of isoniazid and rifampin liquid dosage forms in a national referral center for tuberculosis. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2015;6(4):706–9.

- 40.Nahata MC, Morosco RS, Hippie TF. Stability of rifampin in two suspensions at room temperature. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1994;19(4):263–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1994.tb00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruslami R, Nijland HM, Alisjahbana B, Parwati I, van Crevel R, Aarnoutse RE. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of a higher rifampin dose versus the standard dose in pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(7):2546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. John Wiley & Sons. 1977.

- 43.Bergstrand M, Hooker AC, Wallin JE, Karlsson MO. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. The AAPS journal. 2011;13(2):143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Kiang TK, Sherwin CM, Spigarelli MG, Ensom MH. Fundamentals of population pharmacokinetic modelling. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51(8):515–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Wasserman S, Davis A, Stek C, Chirehwa M, Botha S, Daroowala R, et al. Plasma pharmacokinetics of high-dose oral versus intravenous Rifampicin in patients with tuberculous Meningitis: a randomized controlled trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65(8):e00140–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Rao PS, Moore CC, Mbonde AA, Nuwagira E, Orikiriza P, Nyehangane D, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and significant under-dosing of anti-tuberculosis medications in people with HIV and critical illness. Antibiotics. 2021;10(6):739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Te Brake LH, de Jager V, Narunsky K, Vanker N, Svensson EM, Phillips PP, et al. Increased bactericidal activity but dose-limiting intolerability at 50 mg·kg−1 rifampicin. Eur Respir J. 2021;58.(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Omachi F, Kaneko M, Iijima R, Watanabe M, Itagaki F. Relationship between the effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of oral antineoplastic drugs and their physicochemical properties. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2019;5(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s40780-019-0155-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acocella G. Clinical pharmacokinetics of rifampicin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1978;3(2):108–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Furesz S, Scotti R, Pallanza R, Mapelli E. Rifampicin: a new rifamycin. 3. Absorption, distribution, and elimination in man. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 1967;17(5):534–7. [PubMed]

- 51.Zent C, Smith P. Study of the effect of concomitant food on the bioavailability of rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1995;76(2):109–113. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar AKH, Chandrasekaran V, Kumar AK, Kawaskar M, Lavanya J, Swaminathan S, et al. Food significantly reduces plasma concentrations of first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145(4):530–535. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_552_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saktiawati AMI, Sturkenboom MGG, Stienstra Y, Subronto YW, Sumardi, Kosterink JGW, et al. Impact of food on the pharmacokinetics of first-line anti-TB drugs in treatment-naive TB patients: a randomized cross-over trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;71(3):703–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Van Scoy RE, Wilkowske CJ. Antituberculous Agents. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67(2):179–187. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)61320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verbist L, Gyselen A. Antituberculous activity of rifampin in vitro and in vivo and the concentrations attained in human blood. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1968;98(6):923–932. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1968.98.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peloquin CA, Namdar R, Singleton MD, Nix DE. Pharmacokinetics of rifampin under fasting conditions, with food, and with antacids. Chest. 1999;115(1):8–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haussner F, Chakraborty S, Halbgebauer R, Huber-Lang M. Challenge to the Intestinal Mucosa During Sepsis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:891. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan Y, Chen Y, Zhang X. The effect of opioids on gastrointestinal function in the ICU. Critical Care. 2021;25(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Kenny MT, Strates B. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of the antibiotic rifampin. Drug Metab Rev. 1981;12(1):159–218. doi: 10.3109/03602538109011084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nijland HMJ, Ruslami R, Stalenhoef JE, Nelwan EJ, Alisjahbana B, Nelwan RHH, et al. Exposure to Rifampicin Is Strongly Reduced in Patients with Tuberculosis and Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(7):848–854. doi: 10.1086/507543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yeo CJ, Couse NF, Antiohos C, Zinner MJ. The effect of norepinephrine on intestinal transport and perfusion pressure in the isolated perfused rabbit ileum. J Surg Res. 1988;44(5):617–624. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(88)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feng X-Q, Zhu L-L, Zhou Q. Opioid analgesics-related pharmacokinetic drug interactions: from the perspectives of evidence based on randomized controlled trials and clinical risk management. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1225–1239. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S138698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mummaneni V, Amidon GL, Dressman JB. Gastric pH influences the appearance of double peaks in the plasma concentration-time profiles of cimetidine after oral administration in dogs. Pharm Res. 1995;12(5):780–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Godfrey KR, Arundel PA, Dong Z, Bryant R. Modelling the double peak phenomenon in pharmacokinetics. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2011;104(2):62–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Krause A, Lavielle M, Chatel K, Kohl C, de Kanter R, de la Haye S, et al. Modeling the two peak phenomenon in pharmacokinetics using a gut passage model with two absorption sites. 2013. Available at: https://www.page-meeting.org/default.asp?abstract=2779. Accessed 12 Apr 2022.

- 66.Wang Y, Roy A, Sun L, Lau CE. A double-peak phenomenon in the pharmacokinetics of alprazolam after oral administration. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 1999;27(8):855–9. [PubMed]

- 67.Gerner B, Scherf-Clavel O. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling of cabozantinib to simulate enterohepatic recirculation, drug–drug interaction with rifampin and liver impairment. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(6):778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Shahrami B, Sharif M, Sefidani Forough A, Najmeddin F, Arabzadeh AA, Mojtahedzadeh M. Antibiotic therapy in sepsis: No next time for a second chance! J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46(4):872–876. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karakonstantis S, Ioannou P, Samonis G, Kofteridis DP. Systematic review of antimicrobial combination options for pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics. 2021;10(11):1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance on the Treatment of AmpC β-Lactamase–Producing Enterobacterales, Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(12):2089–114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Bai Y, Liu B, Wang T, Cai Y, Liang B, Wang R, et al. In Vitro activities of combinations of rifampin with other antimicrobials against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(3):1466–1471. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04089-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee HJ, Bergen PJ, Bulitta JB, Tsuji B, Forrest A, Nation RL, et al. Synergistic activity of colistin and rifampin combination against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(8):3738–3745. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00703-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aydemir H, Akduman D, Piskin N, Comert F, Horuz E, Terzi A, Kokturk F, Ornek T, Celebi G. Colistin vs. the combination of colistin and rifampicin for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(6):1214–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Koegelenberg CF, Nortje A, Lalla U, Enslin A, Irusen EM, Rosenkranz B, Seifart HI, Bolliger CT. The pharmacokinetics of enteral antituberculosis drugs in patients requiring intensive care. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(6):394–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Imberti R, Cusato M, Villani P, Carnevale L, Iotti GA, Langer M, Regazzi M. Steady-state pharmacokinetics and BAL concentration of colistin in critically Ill patients after IV colistin methanesulfonate administration. Chest. 2010;138(6):1333–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Cheah SE, Wang J, Nguyen VT, Turnidge JD, Li J, Nation RL. New pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of systemically administered colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in mouse thigh and lung infection models: smaller response in lung infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(12):3291–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Tsuji BT, Pogue JM, Zavascki AP, Paul M, Daikos GL, Forrest A, Giacobbe DR, Viscoli C, Giamarellou H, Karaiskos I, Kaye D. International consensus guidelines for the optimal use of the polymyxins: endorsed by the American college of clinical pharmacy (ACCP), European society of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases (ESCMID), infectious diseases society of America (IDSA), international society for anti‐infective pharmacology (ISAP), society of critical care medicine (SCCM), and society of infectious diseases pharmacists (SIDP). Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2019;39(1):10–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Varshochi M, Hasani A, Derakhshanfar SJ, Bayatmakoo Z, Ghavghani FR, Poorshahverdi P, et al. In vitro susceptibility testing of Rifampin against Acinetobacter Baumannii: Comparison of disk diffusion, agar dilution, and e-test. Erciyes Medical Journal. 2019;41(4):364–9.