Abstract

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a risk factor for prostate cancer (PCa) progression. Thus, this life-threatening disease demands a proactive treatment strategy. Andrographis paniculata (AP) is a promising candidate with various medicinal properties. However, the bioactivity of AP is influenced by its processing conditions especially the extraction solvent.

Objective

In the present study, bioassay-guided screening technique was employed to identify the best AP extract in the management of MetS, PCa, and MetS-PCa co-disease in vitro.

Methods

Five AP extracts by different solvent systems; APE1 (aqueous), APE2 (absolute methanol), APE3 (absolute ethanol), APE4 (40% methanol), and APE5 (60% ethanol) were screened through their phytochemical profile, in-vitro anti-cancer, anti-obese, and anti-hyperglycemic properties. The best extract was further tested for its potential in MetS-induced PCa progression.

Results

APE2 contained the highest andrographolide (1.34 ± 0.05 mg/mL) and total phenolic content (8.85 ± 0.63 GAE/gDW). However, APE3 has the highest flavonoid content (11.52 ± 0.80 RE/gDW). APE2 was also a good scavenger of DPPH radicals (EC50 = 397.0 µg/mL). In cell-based assays, among all extracts, APE2 exhibited the highest antiproliferative activity (IC50 = 57.5 ± 11.8 µg/mL) on DU145 cancer cell line as well as on its migration activity. In in-vitro anti-obese study, all extracts significantly reduced lipid formation in 3T3-L1 cells. The highest insulin-sensitizing and -mimicking actions were exerted by both APE2 and APE3. Taken together, APE2 showed collectively good activity in the inhibition of PCa progression and MetS manifestation in vitro, compared to other extracts. Therefore, APE2 was further investigated for its potential to intervene DU145 progression induced with leptin (10–100 ng/mL) and adipocyte conditioned media (CM) (10% v/v). Interestingly, APE2 significantly diminished the progression of the cancer cell that has been pre-treated with leptin and CM through cell cycle arrest at S phase and induction of cell death.

Conclusion

In conclusion, AP extracts rich with andrographolide has the potential to be used as an alternative to ameliorate PCa progression induced by factors highly expressed in MetS.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, Prostate cancer, Andrographis paniculata, Obesity, Hyperglycemia, Leptin

Introduction

The prevalence of prostate cancer (PCa) in our community is becoming more apparent. A report published by the Ministry of Health of Malaysia (MOH) indicated that between 2007–2011, 3132 cases were reported. Subsequently, between 2012–2016, the total reported case increased to 4189 [1]. It is expected that by 2030, 1.7 million new cases and 499,000 deaths will occur in the entire world [2].

Though the progression of PCa is multifactorial, it has been observed that the progression is worse in individuals with metabolic syndrome (MetS) that comprises high adiposity, hyperglycaemia, hypertension, and high triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein (LDL). A meta-analysis on previously published academic reports revealed that MetS was associated with a 12% increase in PCa risk, and the association was significant in the studies conducted in Europe. The same study also emphasized that hypertension and waist circumference of > 102 cm were associated with a significant 15% and 56% greater risk of PCa [3]. Furthermore, men with MetS appear more likely to have high-grade PCa, more advanced disease, greater risk of progression after radical prostatectomy, and were more likely to suffer PCa-specific death [4].

One of the mediators between MetS and PCa is leptin, a hormone that is secreted by the adipocytes. Long-term exposure to high leptin levels significantly worsens the PCa prognosis due to increased proliferation, migration and invasion of the cancer cells [5]. The action of leptin is more pronounced in the androgen-resistant PCa cells, a plausible explanation for the recurrence of the disease even after radical prostatectomy [6]. As such, treatment approach by using leptin antagonist has gained great research interest. For example, honokiol from Magnolia grandiflora was found to antagonize the activity of leptin and negatively mediate breast cancer cells by inhibiting leptin-induced epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT), and mammosphere-formation along with a reduction in the expression of stemness factors [7].

The therapeutic potential of plant phytochemicals has been gaining more attention in the recent research trend. One such plant that has sparked research interest is Andrographis paniculata (AP). AP is a herbaceous plant commonly known as King of Bitter, Kalmegh, or Hempedu Bumi [8]. Traditionally, AP has been used to treat several ailments, including fever, inflammation, viral and bacterial infections, upper respiratory tract infection, and as an agent for the modulation of the immune system [9, 10]. The medicinal value of AP is attributed to its phytochemicals [11]. As one of the primary compounds of AP, andrographolide has been shown effective in fighting tumours [12], obesity, and hyperglycaemia [13].

Hence, the goal of the current study was to uncover the potential of AP for the treatment of rapidly progressing PCa in MetS microenvironment in vitro. Additionally, during the study, bioassay-guided technique was employed as a screening method in effort to obtain the best extract of AP from various extraction solvents. The best AP extract was chosen based on its ability to exert potent overall bioactivity to simultaneously target PCa, components of MetS, and MetS-PCa co-disease. Based on our thorough literature study, no researcher has attempted this study. Thus, this report is expected to fill an important knowledge gap in the cancer research arena.

Experimental

Chemicals, Reagents and Raw material

Rosiglitazone, oil red O (ORO), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), Trypsin–EDTA, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), dexamethasone (DEX), insulin, and ascorbic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and Penicillin–Streptomycin (P-S) were bought from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA. Isopropanol, paraformaldehyde (PFA), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), sodium nitrite (NaNO2), aluminum chloride hexahydrate (AlCl3.6H2O), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), gallic acid (GA), rutin, methanol, and ethanol were purchased from QRec (Asia), Malaysia. Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) reagent was acquired from Merk, Germany.

The raw material of AP was obtained from local plant nursery, Ethno Resources Sdn Bhd located at Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia (3.222746,101.565417). The harvest time was conducted at day 90 to 100. The plant was collected as whole from root to shoot, dried under shades with air flow, and then pulverized to form powder that passes size 40 mesh.

Preparation and extraction of plant materials

The extraction method employed in this study was Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE). In brief, 5 g of the AP whole plant powder was soaked in five different solvents: 1) aqueous (APE1), 2) absolute methanol (APE2), 3) absolute ethanol (APE3), 4) 40% methanol (APE4) and 5) 60% ethanol (APE5) with solvent-to-sample ratio of 20 mL/g. Then, the beaker was placed in the chamber of an ultrasonic water bath. The temperature of the water bath was set and monitored to 30 °C. Subsequently, the extraction process was conducted for 30 min. Next, the extract was filtered from the coarse powder using a filter paper (Whatman, 125 mm). For every extraction batch, the plant material was exhaustively extracted for three times to maximize the yield. The extract was concentrated in vacuo by using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Laborota 4003, Schwabach, Germany) to a final volume of approximately 10 mL. The remaining solvent content was removed by oven drying at 60 °C for 24 h to leave only the dry extract of the plant. The weight of the dry extract was measured, and the yield was calculated. The dried extract was stored at -20 °C until further use.

HPLC analysis

Phytochemical content analysis was performed using High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Waters, e2695 Separation Module) equipped with an auto-sampler, a column oven, and a UV detector. The reverse-phase C-18 column was used in this study. The system temperature was maintained at 25 °C. The flow rate was controlled at 1 mL/min, and samples were injected at a constant volume of 20 µL. The mobile phase used was the mixture of methanol–water (60%, v/v) with pH adjusted at 2.8 using phosphoric acid. Detection was done at wavelength 210 nm. Standard solutions were prepared (1–1000 µg/mL) by serially diluting the stock solution of andrographolide dissolved in methanol at 1 mg/mL. The concentration of andrographolide, the dominant marker of AP, of each sample, was determined from the standard curve by the external standard method.

Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The determination of TPC was adapted from Ismail et al. [14]. In brief, 1 mL of sample and 1 mL of FC reagent were mixed and incubated for 5 min. Then, the reaction mixture was added with 800 µL Na2CO3 solution (7.5% w/v) and vortexed. The mixture was further incubated at room temperature for 2 h in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm (BioTek ELx808). The standard curve was developed from gallic acid. The phenolic content of the samples was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE) over g dry weight (DW).

Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

TPC analysis was minor adjustments was performed according to Ismail et al. [14]. In short, 0.25 mL of the sample was mixed with 1.25 mL of distilled H2O. Then, 75 µL of 5% (w/v) NaNO2 was added to the mixture. The reaction mixture was incubated for 6 min. Afterward, 150 µL 10% (w/v) AlCl3.6H2O was introduced, and the mixture was further incubated for 5 min. Then, 0.5 mL of 1 M NaOH was added, followed by 275 µL distilled H2O. The absorbance was immediately measured using a microplate reader (BioTek ELx808) at 510 nm. Rutin was used as the standard in this study. The flavonoid content of the samples was expressed as mg rutin equivalent (RE) over g dry weight (DW).

DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity

DPPH radical scavenging activity was performed according to Ismail et al.[14]. Briefly, the DPPH solution was prepared in methanol at 0.1 mM. Then, 3 mL of the DPPH solution was mixed with 200 µL of the samples. The mixture was then incubated in the dark at room temperature for 40 min. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek ELx808). The standard used in this assay was ascorbic acid (0–100 µg/mL). The inhibition percentage was then calculated.

Cell cultures and conditioned media

For the anticancer study, DU145 (Elabscience, China) PCa cell line was used. For the study of antihyperglycemic and anti-adipogenesis, 3T3-L1 (ATCC, USA) preadipocyte was used. Both cells were cultured and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin. The media was regularly replaced with a fresh one every two to three days. Passages were performed by treatment with Trypsin–EDTA. All cells were incubated at 37 °C, with an atmospheric composition of 5% CO2. To initiate differentiation (Day 0) of the preadipocyte cell, 2-days post-confluent cells were incubated with differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.5 mM IBMX, 2 mM DEX and 1.7 mM insulin). After 72 h (Day 3), spent media was replaced by complete DMEM supplemented with 1.7 mM insulin and incubated for 48 h. Differentiated adipocytes were maintained in complete DMEM until Day 10. Conditioned media (CM) was obtained from mature 3T3-L1 after Day 10. The spent media was removed, and cells were gently washed with PBS. Afterward, serum-free DMEM was inserted, and the cell was incubated for 24 h. Then, the CM was collected, centrifuged at 3000 rpm, filtered with a 0.22 µm syringe filter, and stored at -20 °C until further use.

Anti-proliferative assay

The anti-proliferative activity on DU145 was performed according to Suhaimi et al. [15]. The assay was initiated when the cultured cell has achieved 80% confluent. The cells were counted, diluted, and seeded in a 96-well plate at cell density 5 × 103 cells/100 µL/well. The seeded cells were incubated for 24 h. Then, spent media were discarded and replaced with basal DMEM containing the sample at varying concentrations (0–1000 µg/mL) of AP extracts, and the cells were further incubated for 24 h. The MTT colorimetric assay was employed for the detection of the cell’s viability after treatment. In brief, after the treatment, the spent media containing the sample were discarded. Then, 100 µL fresh DMEM and 20 µL MTT solution dissolved in PBS (5 mg/mL) was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. Then, the MTT solution was removed and 200 µL DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystal. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek ELx808).

Anti-migration assay

The anti-migration activity of DU145 was conducted following Soib et al. protocol [16]. In short, DU145 cells were seeded in a 6-wells plate at density 0.3 × 106 cells/3 mL/well. The cell was then incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 until the cell reached 80–90% confluent. A wound was created by scratching the cell monolayer with a 200 µL micropipette tip. Cell debris was rinsed with PBS three times, and samples were introduced into the wells. Wound closure was recorded using an inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Aziovert 100, Jena, Germany) at 0, 12, 24, and 48 h and the closure area was analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH).

Adipogenesis inhibition assay

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated according to the protocol previously described with modification [17]. To determine the effect of the extracts on adipogenesis of 3T3L1, samples at 3.75, 7.5, and 15 ug/mL were added at the initial time of differentiation, Day 0. The addition of samples was continued on Day 3 until Day 5. Treated cells were maintained in complete DMEM until Day 10. At the end of the experiment, the matured adipocytes were fixed with 4% (w/v) PFA for 24 h at room temperature and washed twice with PBS. The ORO stock solution (0.5% w/v) was prepared by dissolving 0.5 g powder in 100 mL isopropanol by overnight stirring. The stock solution was filtered through filter paper and stored at 4 °C in dark. ORO working solution was prepared by 3:2 dilution with deionized water, filtered and covered with aluminum foil. ORO working solution (200μL) was then added to each well and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Stained cells were then washed extensively with tap water. Images were captured using an inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Aziovert 100, Jena, Germany) equipped with a digital camera and image software. To quantify the amount of lipid formed, 300μL isopropanol was added to the stained cells for 10 min with gentle shaking. The dissolved ORO dye was measured at 490 nm. The assay was carried in triplicates. Cells without treatment were set as control.

Antihyperglycemic assay

Glucose utilization assay was performed according to Ismail [18]. At the end of the experiment, data for insulin-sensitizing and -mimicking activities were obtained. In short, before sample treatment, differentiated adipocytes were starved for 3 h in basal DMEM. Extract samples at concentrations of 3.25, 7.5, and 15 µg/mL were added to the assigned wells with or without an additional 1 µg/mL of insulin. After 48 h of incubation, spent media were collected, and glucose utilization was measured using Cobas C111 (Roche). Rosiglitazone was used as a positive control. Treatment was conducted in triplicates.

Stimulation of DU145 with CM and Leptin, and Co-treatment with AP Extract

Before the experiment, cell propagation was conducted as described previously. Once the cultured DU145 has reached 80% confluent, it was trypsinized and counted. The cell was seeded in a 96-well culture plate at a cell density of 5 × 103 cells/100 µL/well. Then the cells were incubated for 24 h in 5% CO2 and 37 °C to allow for cell attachment. Afterward, the cells were serum-starved with serum-free DMEM for 24 h. The cells were incubated with adipocyte CM at 5, 10, and 20%, and leptin at 1, 10, and 100 ng/mL followed by incubation for 48 h. The viability was measured using MTT. For the co-treatment with APE2, after serum-starving, the cells were simultaneously treated with 10% CM/10 ng/mL leptin, and APE2 at various concentrations and incubated for 48 h. Cell’s viability was measured using MTT.

Flow-cytometry for cell cycle and apoptosis

Flow-cytometry analysis was conducted to obtain data on cell cycle progression and apoptosis manifestation using Guava® Muse® Cell Analyzer. DU145 cells were initially propagated in complete DMEM until it reached 70% confluent. Cells were starved for 24 h to synchronization. Then, the spent media was discarded and treatment with 10% CM, 100 ng/mL, APE2 at IC10 and IC25, and cisplatin at IC10 were started for 48 h. At the end of treatment, cells (both floating and attached) were harvested. For cell-cycle analysis, prior to staining, the cells were fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol and incubated at -20 °C for at least 3 h. The fixed cells were stained using cell-cycle kit (Muse® Cell Cycle Kit, MCH100106) according to manufacturer’s instruction. As for apoptosis analysis, right after harvesting, cells were directly stained using apoptosis kit (Muse® Annexin V & Dead Cell Kit, MCH100105) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Following staining, the cells were analyzed using the instrument. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments and analyzed by Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism software. Significant differences were established at p < 0.05.

Results

Extraction yield

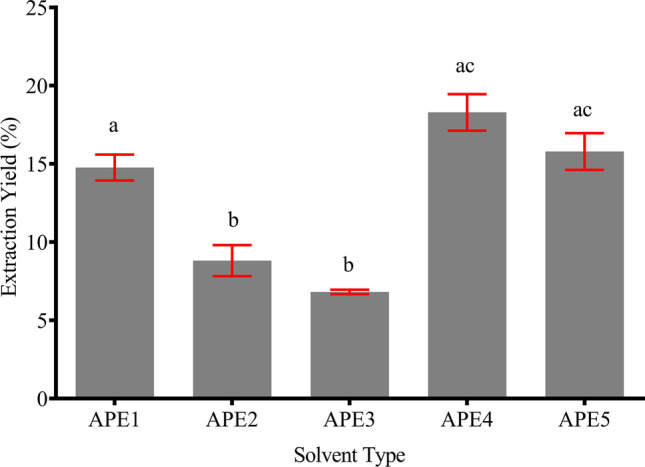

To translate how these solvent systems would affect an extraction outcome, measurement of the extraction yield is often used as this is the most direct and simple method. Extraction yield is a measure to evaluate the efficiency of a technique in extracting specific components from the plant material. It is also largely affected by choice of parameter used during the extraction process. The yield is measured as the weight percentage of the dried crude extract over the weight of the raw material [19]. As depicted in Fig. 1, the extraction yield of AP was the highest in APE4 (18.29 ± 2.02%), followed by APE5 (15.78 ± 2.04%), APE1 (14.76 ± 1.44%), APE2 (8.81 ± 1.72%), and APE3 (6.81 ± 0.24%).

Fig. 1.

Extraction yield of AP using various types of solvent. The yield was calculated as the percentage of dried crude extract over the weight of the raw material. Extraction was done in triplicate for each solvent. Different letters indicate a significant difference at p < 0.5

Phytochemical analysis

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

The High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) technique was utilized to quantify the andrographolide content in the extracts. Analysis of the andrographolide reference (elution time ~ 5.53 min) yielded a standard curve y = 36794x -176,268 with linearity R2 = 0.9972. According to Fig. 2 and Table 1, alcohol mono-solvents generated a high concentration of andrographolide where methanol (APE2) produced 1.34 mg/mL followed by ethanol (APE3) at 1.21 mg/mL. Binary solvents produced relatively moderate concentration of andrographolide with 60% ethanol (APE5) at 0.41 mg/mL and 40% methanol (APE4) at 0.36 mg/mL. Meanwhile, the aqueous solvent (APE1) gave an almost negligible amount of andrographolide, only at 0.03 mg/mL.

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatograms of andrographolide standard (A), APE1 (B), APE2 (C), APE3 (D), APE4 (E) and APE5 (F). The analysis was conducted using a C-18 column with 60% methanol as the mobile phase adjusted at a pH of 2.8 using phosphoric acid

Table 1.

Andrographolide concentration, total phenolic (TPC) and flavonoid content (TFC), and DPPH radical scavenging capacity in AP extracts. Different letters indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05. Each test was conducted in triplicate

| Extract | Andrographolide | TPC | TFC | DPPH | IC50 (µg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/mL | mg GAE/g DW | mg RE/g DW | EC50 (µg/mL) | DU145 | HSF1184 | |

| APE1 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 2.80 ± 0.12 | 3.60 ± 0.86 | N/A | 1284.7 ± 9.2 a | 4675.7 ± 136.2 a |

| APE2 | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 8.85 ± 0.63 | 9.00 ± 0.64 | 397.0 | 57.5 ± 11.8 b | 467.2 ± 6.2 b |

| APE3 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | 8.75 ± 0.06 | 11.52 ± 0.80 | 635.9 | 102.6 ± 2.0 b | 455.2 ± 3.2 b |

| APE4 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 3.63 ± 0.06 | 9.34 ± 0.26 | 1802.0 | 705.3 ± 22.5 c | 1159.3 ± 131.6 bc |

| APE5 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 4.89 ± 0.21 | 11.24 ± 0.12 | 1556.0 | 110.2 ± 17.0 bd | 541.0 ± 14.1 dbc |

Total Phenolic (TPC) and Flavonoid (TFC) Content

As depicted in Table 1, APE2 and APE3 contained the highest TPC, quantified at 8.85 ± 0.63 and 8.75 ± 0.06 mg GAE/g DW, respectively. APE4 and APE5 contained a moderate amount of TPC at 3.63 ± 0.06 and 4.89 ± 0.21 mg GAE/g DW. APE1 has the lowest TPC at only 2.80 ± 0.12 mg GAE/g DW. Based on this finding, extraction using absolute alcohol effectively produced a substantially higher TPC followed by binary and aqueous solvents. However, for TFC, ethanol-based solvents resulted in higher concentration of flavonoid. The amount followed the order of APE3 (11.52 ± 0.80 mg RE/g DW) > APE5 (11.24 ± 0.12 mg RE/g DW) > APE2 (9.34 ± 0.26 mg RE/g DW) > APE4 (9.00 ± 0.64 mg RE/g DW) > APE1 (3.60 ± 0.86 mg RE/g DW).

Radical Scavenging Activity

Dose-dependent DPPH radical scavenging activity was present in all extracts (Fig. 3). Of all the extracts, APE2 exerted the best scavenging activity with EC50 of 397.0 µg/mL followed by APE3 (635.9 µg/mL), APE5 (1556.0 µg/mL) and APE4 (1802.0 µg/mL) (Table 1). For APE1, the scavenging activity was the weakest with only 17% activity at the highest tested concentrations. For comparison, andrographolide and ascorbic acid exhibited potent antioxidant activity with EC50 = 2.2 µg/mL and EC50 < 0.98 µg/mL respectively.

Fig. 3.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of different solvents of AP extracts. The concentration tested was from 0.98 µg/mL to 2000 µg/mL. The experiment was run in triplicate (n = 3), and each data were plotted as mean with an SD bar. Andrographolide and ascorbic acid were used as control

In Vitro prostate cancer inhibition

Anti-proliferative activity on DU145

To investigate the anticancer potential of different AP extracts, DU145 was treated with the extracts at varying concentrations, ranging from 0 to 1000 µg/mL for 24 h. For cytotoxicity profile comparison, normal fibroblast cell (HSF1184) was also simultaneously treated in this study.

As depicted in Fig. 4, dose-dependent effects were exhibited by all AP extracts against both cells. However, the anti-proliferative effects of the extracts were more profound on DU145, except for APE1 and APE4. Both extracts only inhibited the DU145 proliferation at the highest concentration tested, 1000 µg/mL (APE1 = 37% inhibition; APE4 = 73% inhibition). On the other hand, APE1 showed strong and significant proliferative activity on HSF1184 growth in all concentrations tested with the highest at 250 µg/mL (2.78-fold as compared to control).

Fig. 4.

The anti-proliferative activity of AP extracts from different solvents. A) DU145 cells viability and B) HSF1184 cell viability. The experiment was conducted in triplicate, and each graph represents mean ± sd. * represents a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to the control

APE2 demonstrated the strongest cytotoxicity toward DU145 by causing severe cell death (56% inhibition) at the lowest concentration of 62.5 µg/mL. At increased concentration of 500 µg/mL, only 3% of cells survived. Compared to treatment on HSF1184, the death-inducing effect was only noticeable at 500 µg/mL.

Meanwhile, APE5 increased the viability of normal cells at concentration ≤ 500 µg/mL with almost 1.7-fold greater than control but exhibit severe toxicity at 1000 µg/mL (88% inhibition). On DU145, the viability was decreased even during the exposure at the lowest concentration (62.5 µg/mL; 38% inhibition) and maximum inhibition was measured at 500 µg/mL (93% inhibition).

Overall, the IC50 of all extracts on DU145 were reached at doses below 1000 µg/mL, as indicated in Table 1, except for APE1, where the IC50 exceeded 1000 µg/mL. This finding showed that APE1 has a lower cytotoxicity profile on DU145 as compared to other extracts. In contrast, APE2, APE3, and APE5 exhibited stronger but relatively mild cytotoxicity towards DU145 with IC50 of 57.5, 102.6, and 110.2 µg/mL respectively. These results demonstrated that the growth inhibition on DU145 was influenced by extraction solvent in the following order: APE2 > APE3 > APE5 > APE4 > APE1.

Anti-migratory activity on DU145

One of the harmful effects of PCa is its capability to metastasize from its site of origin to other parts of the body. Thus, uncovering the potential of AP extract as an anti-migratory agent is necessary. In this regard, the scratch assay was conducted to study the anti-migratory effect of the extracts [20]

From Fig. 5, the scratched area in the control group of all extracts were fully closed at 48 h of treatment. However, treatment with AP extracts prevented the migration of DU145 cells for a full recovery. In accordance with the anti-proliferative results, APE1 exhibited the fastest migration rate as compared to other extracts. At the highest concentration tested (1000 µg/mL) inhibition of wound closure was only at 30% after 48 h. Referring to Fig. 6, APE1 at 125 µg/mL delayed the migration of DU145 cells at the early time of treatment, (12 h: 31%; 24 h: 45%). However, 90% of the scratched area was covered after 48 h suggesting that APE1 was a weak anti-migratory agent.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of DU145 migration during the treatment of AP extracts. The assay was conducted using scratch assay technique. Each group was treated at five different doses (0 – 1000 µg/mL). Measurement was taken at 0 (baseline), 12, 24, and 48 h. The closure percentage was calculated based on the baseline area. The analysis was determined using ImageJ software. Measurement was done in triplicate

Fig. 6.

Migration activity of DU145 treated with AP extracts at 125 µg/mL. Images were captured at 0 (baseline), 12, 24, and 48 h. using an inverted microscope at a magnification of × 4. At 48 h. of APE2 and APE3, the cell has lost integrity and has detached from the surface. Further staining with trypan blue indicates that the cells are no longer viable

However, for APE4 and APE5, dose-dependent anti-migration behaviours at concentration ≥ 62.5 µg/mL were observed with 70% reduction in migration at 250 µg/mL after 48 h of treatment. Treatment at ≥ 500 µg/mL of APE4 and APE5 caused the cells to lose integrity and viability.

A greater anti-migration effect was observed in APE2 and APE3. Migration of cells at the scratched area was partially inhibited at ≤ 125 µg/mL of extracts and dominant at 24 h of treatment. However, at prolonged exposure (≥ 48 h) to these extracts, cell death happended. Besides, when compared to APE3 that still manifests migration at hour 24, APE2 migration was slightly reduced from 29 to 26%, suggesting suitability as a candidate for an anti-cancer agent.

In Vitro targeting of metabolic syndrome components

Adipogenesis Inhibition Assay

Inhibition of adipogenesis is an effective method to reduce adiposity in MetS. During insulin treatment in the induction phase, the 3T3-L1 cells were concurrently treated with AP extracts at dose 3.25 µg/mL – 15 µg/mL for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 7, all AP extracts dose-dependently reduced the adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 adipocytes at different magnitudes. APE3 delivered the highest percentage of inhibition (± 87%) for all tested concentrations. On the other hand, APE5 dose-dependently inhibits adipogenesis up to 86.34% at 15 µg/mL. Both extracts had ethanol as a solvent. In comparison, APE2 and APE4 are methanol-based extracts. APE4 produced a higher percentage of inhibition of 77.88% at 15 µg/mL against 53.95% at a similar concentration of APE2. Meanwhile, APE1 resulted in inhibition of only 22.21% at 15 µg/mL.

Fig. 7.

Effect of AP extracts on the percentage formation of lipid in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Dose-dependent inhibition of adipogenesis was observed in all extracts. Cells induced with insulin alone was set as the untreated control. Rosiglitazone, a type antidiabetic drug, was used as the positive control. Significant was considered at p < 0.05 (N = 3)

Insulin-Sensitizing and Mimicking Assay

Anti-hyperglycaemic drugs such as metformin and thiazolidinediones are designed to sensitize insulin function in the glucose transportation process. In this section, the effect of AP extracts on sensitizing the activity of insulin were measured via glucose consumption assay in the presence of insulin. Results in Fig. 8 showed that APE2 consistently enhanced glucose consumption by 7% compared to the control group. For APE3, a comparable increase in glucose consumption was observed for all concentrations, but only significant at 7.25 µg/mL with a 5.61% of increment. On the other hand, APE1, APE4, and APE5 failed to facilitate glucose consumption in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

Fig. 8.

Effect of extracts of AP on insulin-dependent glucose consumption in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Insulin alone was set as a negative control. Rosiglitazone was set as a positive control. Significant was considered as p < 0.05 (N = 3)

The high glucose level in the blood might also result from the permanent damage of pancreatic beta-cell as the producer of insulin. In this case, external insulin is required for hyperglycaemia control. Therefore, the AP extracts were further tested for their ability to mimic the function of insulin. Adipocytes were treated with the extracts without the presence of insulin. It was discovered that AP extract mimicked the insulin properties by increasing glucose consumption. Dose-dependent increment of glucose consumption was observed for APE2, APE3 and APE5 (Fig. 9). For APE2, the glucose consumption was gradually increased by 2.43%, 4.55% and 6.06% at a concentration from 3.75 µg/mL to 15 µg/mL respectively. Meanwhile, a similar trend was also observed in APE3 with an increase of 2.35%, 4.47% and 5.98% at the same concentration range. For APE5, lower but significant values of glucose consumption were measured. Within the tested concentration, the glucose consumption was enhanced up to 4.39% at 15 µg/mL. On the other hand, APE4 and APE1 failed to significantly mimic insulin activity.

Fig. 9.

Effect of AP extracts on glucose consumption in 3T3-L1 adipocytes without co-incubation with insulin. Rosiglitazone was set as positive control. Significant was considered as p < 0.05 (N = 3)

Proliferation of prostate cancer cell in metabolic syndrome environment and role of a. paniculata

effect of adipocyte conditioned media and leptin on DU145 proliferation

Exposure to conditioned media (CM) from mature adipocytes significantly accelerates the proliferation of DU145 with maximum induction at 10% of CM (Fig. 10). However, at 20% of CM, the cells' proliferation was reduced, but its difference with the untreated group was still statistically significant. In the group treated with leptin alone, the cells' proliferation was also dose-dependently stimulated with a progressive increase of viable cells from 1 to 100 ng/mL of leptin. At 100 ng/mL of leptin, the increase was comparable to 10% CM.

Fig. 10.

The effect of leptin and adipocyte CM on the proliferation of DU145 prostate cancer cell line. Adipocyte CM was prepared from matured 3T3-L1 culture, filter-sterilized, and diluted with fresh complete DMEM to 5%, 10%, and 20% dilution. Cells incubated with only fresh complete DMEM was set as the control. The experiment was conducted in quintuplicate. Significance was considered at p < 0.05 (N = 6). Asterisk (*) represents a statistically significant difference compared to the control group

Effect of APE2 on Prostate Cancer Cell Induced with Leptin and Adipocyte CM

Based on the bioassay-guided screening in the earlier sections, APE2 collectively exhibited the best effects in this study. Therefore, it was further investigated for its potential as to attenuate the deleterious effects imposed by MetS on PCa cells. In this study, MetS microenvironment was manifested by adipocytes CM and exogenous recombinant leptin. In the untreated control, both leptin and CM significantly enhanced the cell’s proliferation by 25% and 20% respectively (Fig. 11). Interestingly, incorporation of APE2 during the treatment reduced the cell viability. The anti-proliferative effect was more profound in CM-treated as compared to leptin-treated cells. In CM-treated cells, APE2 significantly reduced cell viability to 60% at 60 µg/mL. Meanwhile, in leptin-treated cells, 50% of the reduction was observed at 60 µg/mL.

Fig. 11.

DU145 cell viability incubated with 10% adipocyte CM (A) and 10 ng/mL leptin (B). The cells were co-treated with APE2 (0 – 60 µg/mL) for 48 h. Cells incubated with fresh DMEM alone were set as negative control. * represents significant differences compared to the negative control. # represents significant differences with the group treated with either CM or leptin alone. All test was conducted in quintuplicate, and significance was considered at p < 0.05

Cell Cycle Analysis Using Flow-Cytometry

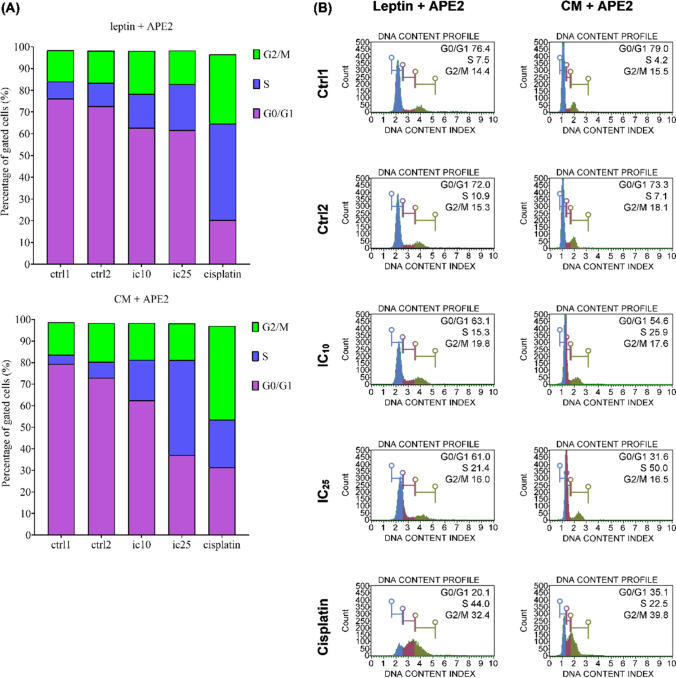

To further understand how leptin and adipocyte CM affect the proliferation of DU145, a flow-cytometry analysis was conducted as presented in Fig. 12 and Table 2. Treatment of the cells with either exogenous leptin or adipocyte CM significantly increased entry into the S-phase (ctrl1 vs ctrl2). Leptin increased the proportion as much as 2.84% while CM caused an increase of 3.26%. Subsequently, co-treatment of the cells with APE2 and leptin/CM dose-dependently arrested the growth cycle at S-phase. In the group treated with leptin (100 ng/mL), co-treatment with APE2 at IC10 and IC25 arrested the cycle at S-phase as much as 15.53 ± 0.78% and 21.13 ± 0.55%, respectively. For the group induced with adipocyte CM, APE2 at IC10 and IC25 halted the cycle to 18.83 ± 6.82% and 44.07 ± 5.95%, respectively.

Fig. 12.

Flow cytometry analysis (cell cycle) on DU145 following treatment with leptin (100 ng/ml), adipocyte CM (10%), APE2 at IC10 and IC25, and cisplatin at IC10

Table 2.

Percentage of gated cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases. Asterisk (*) represents a significant difference compared to ctrl1 (p < 0.05). Dagger (†) represents a significant difference compared to ctrl2 (p < 0.05). Each test was conducted in triplicate (n = 3)

| Leptin + AP (Methanol) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin | AP | Cis | G0/G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M (%) | |

| ctrl1 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 76.23 ± 0.47 | 7.83 ± 0.42 | 14.30 ± 0.26 |

| ctrl2 | ✔ | ✗ | ✗ | 72.70 ± 0.61* | 10.67 ± 0.21* | 14.87 ± 0.45 |

| ic10 | ✔ | IC10 | ✗ | 62.77 ± 0.67† | 15.53 ± 0.78† | 19.77 ± 0.06† |

| ic25 | ✔ | IC25 | ✗ | 61.63 ± 1.64† | 21.13 ± 0.55† | 15.50 ± 0.95 |

| cisplatin | ✔ | ✗ | IC10 | 20.30 ± 0.35† | 44.37 ± 0.32† | 31.83 ± 0.49† |

| Adipocyte CM + AP (Methanol) | ||||||

| CM | AP | Cis | G0/G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M (%) | |

| ctrl1 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 79.40 ± 0.69 | 4.17 ± 0.45 | 15.13 ± 0.32 |

| ctrl2 | ✔ | ✗ | ✗ | 72.93 ± 2.27 | 7.43 ± 0.42* | 17.97 ± 1.80 |

| ic10 | ✔ | IC10 | ✗ | 62.47 ± 6.92 | 18.83 ± 6.82 | 17.03 ± 0.51 |

| ic25 | ✔ | IC25 | ✗ | 37.10 ± 5.94† | 44.07 ± 5.95† | 17.00 ± 0.78 |

| cisplatin | ✔ | ✗ | IC10 | 31.40 ± 3.92† | 22.07 ± 1.12† | 43.57 ± 3.53† |

| Leptin = 100 ng/mL; CM = 10%; APE2 IC10 = 24.11 µg/mL, IC25 = 42.11 µg/mL; Cisplatin IC10 = 4.11 µg/mL | ||||||

Apoptosis Analysis Using Flow-Cytometry

To understand the mode of cell death caused by APE2, a test for apoptosis was conducted on the cells using a similar design as the test for the cell cycle. A very prominent trend can be observed from the data (Fig. 13). Firstly, in both treatment groups, the total apoptotic event was marginally reduced after exposure to leptin and CM (ctrl2). In CM-treated group, total apoptotic cell was reduced from 4.48% to 2.35%. In leptin-treated group, the reduction was from 8.56% to 7.28%. Secondly, treatment with APE2 significantly increased the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis at both IC10 (CM: 18.23%, leptin: 13.60%) and IC25 (CM: 9.10%, leptin: 13.19%) compared to drug control (CM: 3.58%, leptin: 7.28%). Finally, lower dose of APE2 (IC10) implicated a higher total margin of apoptotic event. At higher doses of APE2 (IC25) the apoptosis of the cell is lower (if not similar) compared to the lower dose of APE2.

Fig. 13.

Flow cytometry analysis (apoptosis) on DU145 following treatment with leptin (100 ng/ml), adipocyte CM (10%), APE2 at IC10 and IC25, and cisplatin at IC10. (A) illustrates the total apoptotic event, distinguished by early and late apoptosis. (B) represent the crude data obtained from the flow cytometer

Discussion

Obesity increased the risk of developing PCa. Hypertrophic condition of fat cells in obese people secretes large amount of adipokines (leptin, adiponectin), cytokines (TNF-alpha, Il6) and lipid that synergistically involved in the enhancement of metastasis progression of PCa cells. In this study, 10% condition media (CM) derived from the 48 h incubation of 3T3-L1 mature adipocytes resulted in a significant progression in DU145 growth by almost 20%. Previously, adipocyte CM has demonstrated a favourable effect on cancer cells growth. It has been shown to accelerate the growth of melanoma and colon cancer cells in vitro [21]. Exposure with adipocyte CM on breast cancer cell (MCF-7) also significantly enhanced the proliferation and metastasis [22]. Report from preclinical and clinical data has repeatedly suggested the association of leptin; one of the prominent adipokines secreted in CM with PCa. Long‑term exposure of PCa cells to leptin has been observed to enhance their proliferation, migration, and invasion [20].

This phenomenon was confirmed in this study, whereby 100 ng/mL of leptin alone increased the DU145 progression by 23%. Interestingly, co-treatment with APE2, a methanolic extract of AP, could act as anti-proliferative agent that inhibits the DU145 growth under CM-induced and leptin-induced condition. At 60 µg/mL, the decrease of cell viability was similar to the IC50 of APE2 treatment without the presence of CM and leptin, which was 57.5 ± 11.8 µg/mL, suggesting APE2 works well in MetS as well as in non-MetS conditions. The anti-proliferative activities of AP have been previously reported on both healthy and cancerous cells [23]. Moreover, most of the findings are leaning toward the supposition that AP has high potential as an anticancer agent. For example, the dichloromethane fraction of the methanolic AP extract has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of HT-29 (colon cancer) with IC50 value of 10 µg/mL [24]. The methanolic extract also has been shown to effectively inhibit the human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells with a mean IC50 of 28 µg/mL [25]. AP extract has also been tested for oesophageal cancer treatment in animal model. Treatment of the metastatic oesophageal xenograft-bearing mice at a dose of 1600 mg/kg exhibited inhibition of tumour growth and metastasis [26]. These discoveries are in agreement to our result that showed potential antiproliferative activity against DU145 in both APE2 and APE3, with greater emphasis on APE2.

However, according to a report by Fadeyi and colleagues, for antitumor study, crude plant extracts that exhibit ≥ 80% growth inhibition at 200 µg/mL are considered moderately active. The extracts can only be considered very active if ≥ 50% inhibition can be achieved at 20 µg/mL and potent if ≥ 80% inhibition can be achieved at the same concentration [27]. Additionally, according to the US National Cancer Institute Guidelines, plant extracts will only be considered as potent antitumor agent if the IC50 is below 30 µg/mL [28]. Extracts that do not fall into either of these categories are considered not significant for the study. This criterion has also been applied for other assays apart from antitumor. Based on this understanding, APE2 can only be described as mildly active against MetS-PCa co-disease in this in vitro study. Nevertheless, several literature reports have attempted to resolve this limitation by incorporating nanocarrier. Through this method, the permeability and retention of active compound at disease site could be increased leading to improve therapeutic activities [29]. For example, andrographolide that has been encapsulated into liposome was found to exert better hepatoprotective activity compared to free andrographolide [30]. Another concern pertaining andrographolide efficacy is its inability to fully dissolve in aqueous solvent and low bioavailability. But, by encapsulation using nanocarrier, this drawback can be overcome [31]. Li and friends have shown that by encapsulating andrographolide into solid-lipid nanoparticle (SLN), the bioavailability was enhanced and the IC50 against the head and neck cancer cells was marginally reduced compared to treatment with free andrographolide [32]. Therefore, future attempt to extent this study should take into consideration this aspect.

The higher anti-proliferative potential of AP extract is accredited to the high andrographolide content. In the literature, pure andrographolide has been found useful in preventing the growth of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) by inducing apoptosis through the inhibition of P13K/AKT pathway at a dose of 10 µg/mL [33]. The work from Liu and colleagues has also shown that administration with andrographolide could downregulate the expression of androgen receptor (AR) and its associated signalling in PCa cells, which partly responsible for the development of castration-resistance PCa (CRPC) [34]. In an animal study, andrographolide was found to decrease tumour volume, MMP-11 expression, and blood vessel formation. The compound was also suggested to cause DNA damage, leading to the growth inhibition of the cancer cells [35].

Cell cycle assessment on CM and leptin-induced condition showed that the entry into the S-phase was markedly increased in both groups after exposure with leptin and CM. Entry into the G2/M-phase was also noticeably elevated following CM treatment (Fig. 12). The role of CM and leptin on the proliferation of cancer cells has been reported from the cell cycle point of view. Leptin particularly increases the expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 2, which accelerates the cell cycle of breast cancer cells [36]. Cyclin D1 functions in the regulation of the cell cycle through the G1 to S phase [37]. The entry into the S-phase for the group exposed with CM was marginally higher compared to treatment with leptin alone. This could result from the content of the CM that consists of many cytokines in addition to leptin. Adipocyte CM has also been reported to contain TNF-α [38] which has been linked to the up-regulation of CYCLIN D1 gene expression [39]. Similarly, exposure of colon cancer cell line, HT-29, upon adipocyte CM statistically increased entry into the S phase [40]. However, treatment with APE2 dose-dependently arrested progress of the cell cycle at S phase in both groups. The current finding was reflective of previously reported finding whereby treatment with andrographolide, a component of APE2, significantly stop the cell cycle at S phase in breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231 [41].

Cell cycle arrest could trigger apoptosis [42]. However, in this study, exposure to the cancer cell with leptin and CM significantly reduced the apoptotic characteristic. But, externalization of the phosphatidylserine, which is a prominent apoptosis characteristic, was detected after treatment with APE2 in both groups. Verily, cell arrest following AP extract treatment has also been reported to lead to the apoptotic event in human leukaemia cells [43]. Nevertheless, a paradoxical trend was seen in the apoptosis process after APE2 treatment. At increased dose (IC25), the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was unaltered for the leptin-treated group, while for CM-treated group, the percentage was even reduced (Fig. 13). A similar finding was reported whereby at increased andrographolide dosage, the gastric cancer cell was found to be less apoptotic. Rather, the cell was described to undergo non-apoptotic cell death [44]. The author also suggested that at increased dose, multiple death signalling could be activated at once (as opposed to sequential death signalling in apoptosis) leading to quick cell death [44]. Two of the major AP components (andrographolide and dehydroandrographolide) has been reported to induce autophagic cell death in human oral cancer cell [45]. Thus, this is a plausible mode of cell death implicated on DU145, but more in-depth research is needed for confirmation.

In our initial steps to identify the most prominent extract suitable for the above assays, AP was extracted using five different solvents: aqueous (APE1), absolute methanol (APE2), absolute ethanol (APE3), 40% methanol (APE4) and 60% ethanol (APE5). The choice for these solvents was derived from literature reports. The utilization of absolute ethanol and methanol as one of the options was due to its ability to maximize the extraction of andrographolide, and other active phytochemicals compared to other organic solvents [46]. In particular, methanol has been reported to have almost similar Hildebrand parameter (δ) to andrographolide (14.45 vs 14.80) as compared to ethanol (δ = 12.90) [47]. This vastly facilitates the solubility of andrographolide. As for hydro-alcoholic mixture of solvents, it was included in this study based on previous finding that reported higher extraction yield of AP compared to single solvent system [48]. 40% methanol extract of AP was reported to give relatively high extractable andrographolide content [49], while the 60% ethanol extract was found to exhibit highest TPC and antioxidant activity [50]. Ethanol and aqueous solvents are also known to be safe for human consumption [51]. The attempt to extract AP from other organic solvents such acetone, chloroform, and hexane has also been reported. But, due to low recovery of andrographolide as reported by previous researcher [47], these solvents were excluded in this study.

For mono-solvent systems, APE1 resulted with the highest yield. This could be attributed to the physicochemical properties of water. At ambient temperature, the dielectric constant (K) of water is around 78.36 [52]. However, cavitation caused by UAE could cause elevation of the temperature into the system. At the elevated temperature, the K value of water could be shifted closer to the K value of organic solvents such as methanol (K ~ 31.13) and acetonitrile (K ~ 35.11) [53]. At these K values, the extraction of non-polar organic matters could also be achieved [54]. In the binary-solvent system, both APE4 and APE5 exceeded the yield of all mono-solvent extracts. The higher yields in the binary solvent extracts may be explained through the properties of the solvents and the solutes. Alcohols such as methanol and ethanol are organic solvents with moderate to low polarity while water is an inorganic solvent with higher polarity. Since the solubility of a component follows the principle of “like dissolves like,” alcohols facilitate the extraction of compounds with lower polarity while water is responsible for the extraction of component with higher polarity [19]. However, in mixture of both solvents, a shift of polarity takes place reflected by the K value. 40% methanol and 60% ethanol would have a K values of 60.94 and 46.76 respectively [55, 56]. This way, the range of the extractable compound is wider, and the yield could be maximised as indicated in the finding of this study.

The selection of APE2 extract as the most suitable extracts for MetS-PCa condition was made based on two bio-assay guided steps: 1) anti-proliferation & anti-migration under non-metabolic syndrome condition and 2) anti-adipogenesis and anti-diabetes profiles. It was apparent from this study that APE2 and APE3 gave favourable results in the study of the anti-proliferation and anti-migration of DU145 cells. It was suspected to be caused by high andrographolide content as depicted from the HPLC quantification. A study has shown that andrographolide was able to prevent the 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced mobility and invasion of MCF-7 by interfering with the expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 and MMP-2 which involve in the degradation of the extracellular matrix, providing passage for migrating cancer cells [57, 58]. Moreover, the migration of cancer cells is usually assisted by the action of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF induces new vessel formation and tumour growth by inducing mitogenesis [59]. A study has reported that andrographolide, extracted and purified with methanol, was found to significantly inhibit the formation of a new blood vessel in VEGF-induced HUVEC cells by restricting its mobility and tube-forming activities [60]. Another possible explanation is through the activity of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. TGF-β signalling plays context-dependent roles in cancer: in pre-malignant cells, TGF-β primarily functions as a tumour suppressor, while in the latter stages of cancer, TGF-β signalling promotes invasion and metastasis [61]. However, andrographolide has been reported to reduce the activity of TGF-β, eventually reducing metastasis [62].

Previously, andrographolide has been reported to inhibit the adipogenesis process by downregulating mRNA and protein expression of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα) and C/EBPβ, as well as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) during the adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells [63]. However, in this study, the order of inhibition was not according to the order of andrographolide content. Rather, the arrangement was proportional to the estimated flavonoid content. This finding indicates that this phytochemical group might be directly involved in the adipogenesis inhibition process. AP extracts have been shown to contain several flavonoids including 5,7,2′,3′-tetramethoxyflavanone, 5-hydroxy-7,2′,3′-trimethoxyflavone, 5-hydroxy-7,8,2,3-tetramethoxyflavone, 5-hydroxy-7,2,6-trimethoxyflavone, skullcap flavone 12-methylether and 5-hydroxy-7,8,2,5-tetramethoxy-flavone [64]. Depending on the arrangement of side groups, particularly the hydroxy and methoxy functional groups, the flavonoids could act either as chemo-preventive or chemosensitizer entity [65]. Consistent with the finding in this study, flavonoid content could positively act as a chemosensitizer of andrographolide for adipogenesis inhibition. However, an in-depth investigation of this association is necessary, and a study of its own is warranted.

It was also discovered that AP could enhance the sensitivity of insulin to induce glucose transportation into the cells, in this case, 3T3-L1 adipocytes. APE2 exhibited the most profound effect. This extract sensitized the insulin action for all concentrations tested. Meanwhile, APE3 selectively sensitized insulin activity at 7.5 µg/mL. Previously, the incidence of insulin resistance was reported because of the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα activity. This cytokine impairs the translocation of glucose transport 4 (GLUT4) to the cellular membrane. However, administration of AP extracts attenuated the reduced glucose uptake in animal study [66]. Insulin sensitizing effect has also been reported in the work of Ismail in his dissertation [18]. The author postulated that the strong anti-hyperglycaemic effect of 100% alcohol extracts might come from the high level of andrographolide content, which is three times higher than the binary solvent extracts. The compound was reported to sensitize the effect of insulin during the incubation together with insulin [67].

Insulin mimicry action of phytochemicals has been reported in several literature findings. For example, the extract from the fruit of bitter melon (Momordica charantia) has been found to mimic the action of insulin. The antihyperglycemic potential was also found to be caused by inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), activation of AMPK, an increase of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) expression, and recovery of pancreatic β-cell [68]. At the same time, insulin-mimetic and secretagogue activities of several plant extracts have also been reviewed in a report from Patel and colleagues that include herbal plants such as Ficus bengalensis (Moraceae) and Lepechinia caulescens (Lamiaceae) [21]. Therefore, the quality as an insulin-mimetic agent of AP extract is highly possible since this plant has been extensively established to possess anti-hyperglycaemic potential through several pathways.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the bioassay-guided extraction of AP was successfully conducted. During the process, five extracts of AP were studied for their phytochemical content as well as anticancer, anti-obese, and anti-hyperglycaemic activities. Collectively, APE2 was found to exert the best bioactivity in most of the assays conducted. Thus, its potential was further tested for MetS-PCa co-disease in vitro. Adipocyte CM and leptin both significantly accelerated the proliferation of DU145. The level of induction was comparable between 10% CM and 100 ng/mL. From this finding, it is apparent that highly expressed leptin in MetS could positively affect PCa cells proliferation. Treatment with APE2, however, was shown to interfere with this association. APE2 inhibited the proliferative effect of leptin on DU145 possibly through cell cycle arrest and induction of cellular death signalling. This study exposed an interesting finding on the therapeutic value of APE2 in MetS-PCa co-disease. However, data presented here is still very limited to draw a comprehensive conclusion. Thus, further consideration into this study should be approached from in vivo point-of-view.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mohamad Khairul Hafiz Idris, Email: mhkhairul@gmail.com.

Rosnani Hasham, Email: r-rosnani@utm.my.

Hassan Fahmi Ismail, Email: h.fahmi@umt.edu.my.

References

- 1.Azizah AM, et al. Malaysia national cancer registry report (MNCR) 2012–2016. 2019, National Cancer Institute: Putrajaya.

- 2.Pakzad R, et al. The incidence and mortality of prostate cancer and its relationship with development in Asia. Prostate International. 2015;3(4):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esposito K, et al. Effect of metabolic syndrome and its components on prostate cancer risk: Meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2013;36(2):132–139. doi: 10.1007/BF03346748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiang Y-Z, et al. The association between metabolic syndrome and the risk of prostate cancer, high-grade prostate cancer, advanced prostate cancer, prostate cancer-specific mortality and biochemical recurrence. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noda T, et al. Long-term exposure to leptin enhances the growth of prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2015;46(4):1535–1542. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoda MR, et al. The adipocyte-derived hormone leptin has proliferative actions on androgen-resistant prostate cancer cells linking obesity to advanced stages of prostate cancer. Journal of oncology, 2012. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Avtanski DB, et al. Honokiol activates LKB1-miR-34a axis and antagonizes the oncogenic actions of leptin in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(30):29947–29962. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra SK, Sangwan NS, Sangwan RS. Phcog Rev.: Plant Review Andrographis paniculata (Kalmegh): A Review. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2007. 1(2): p. 283–298.

- 9.Chao W-W, et al. Inhibitory effects of ethyl acetate extract of Andrographis paniculata on NF-kB trans-activation activity and LPS-induced acute inflammation in mice. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:9. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxena RC, et al. A randomized double blind placebo controlled clinical evaluation of extract of Andrographis paniculata (KalmColdTM) in patients with uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(3):178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S, et al. Application of nanotechnology in improving bioavailability and bioactivity of diet-derived phytochemicals. J Nutr Biochem. 2014;25(4):363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varma A, Padh H, Shrivastava N. Andrographolide: A New Plant-Derived Antineoplastic Entity on Horizon. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Wong TS, et al. Synergistic antihyperglycaemic effect of combination therapy with gallic acid and andrographolide in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology. 2019. 18:101048.

- 14.Ismail HF, et al. Comparative study of herbal plants on the phenolic and flavonoid content, antioxidant activities and toxicity on cells and zebrafish embryo. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017;7(4):452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suhaimi SH, et al. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction conditions followed by solid phase extraction fractionation from Orthosiphon stamineus Benth (Lamiace) leaves for antiproliferative effect on prostate cancer cells. Molecules. 2019;24(22):4183. doi: 10.3390/molecules24224183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soib HH, et al. Bioassay-Guided Different Extraction Techniques of Carica papaya (Linn.) Leaves on In Vitro Wound-Healing Activities. Molecules. 2020. 25(3):517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ismail HF, Majid FAA, Hashim Z. Eugenia Polyantha Enhances Adipogenesis via CEBP-Α and Adiponectin Overexpression in 3T3-L1. Chem Eng Trans. 2017;58:1117–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ismail HF. Anti-Diabetes Mechanism of Action By SynacinnTM In Adipocytes. 2018. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

- 19.Zhang S-Q, Bi H-M, Liu C-J. Extraction of bio-active components from Rhodiola sachalinensis under ultrahigh hydrostatic pressure. Sep Purif Technol. 2007;57(2):277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2007.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(2):329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel DK, et al. An overview on antidiabetic medicinal plants having insulin mimetic property. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(4):320–330. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60032-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko J-H, et al. Conditioned media from adipocytes promote proliferation, migration, and invasion in melanoma and colorectal cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(10):18249–18261. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amini N, et al. CervicareTM induces apoptosis in HeLa and CaSki cells through ROS production and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. RSC Adv. 2016;6(29):24391–24417. doi: 10.1039/C5RA25654B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ajaya Kumar R, et al. Anticancer and immunostimulatory compounds from Andrographis paniculata. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;92(2):291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki R, et al. Cytotoxic components against human oral squamous cell carcinoma isolated from Andrographis paniculata. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(11):5931–5935. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, et al. The adjuvant value of Andrographis paniculata in metastatic esophageal cancer treatment – from preclinical perspectives. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):854. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00934-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fadeyi SA, et al. In vitro anticancer screening of 24 locally used Nigerian medicinal plants. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rummun N, et al. Antiproliferative activity of Syzygium coriaceum, an endemic plant of Mauritius, with its UPLC-MS metabolite fingerprint: A mechanistic study. PloS one. 2021. 16(6):e0252276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Murakami M, et al. Improving Drug Potency and Efficacy by Nanocarrier-Mediated Subcellular Targeting. Science Translational Medicine. 2011. 3(64):64ra2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Midya DK, Pramanik KC, Chatterjee TK. Effect of Andrographolide-Encapsulated Liposomal Formulation on Hepatic Damage and Oxidative Stress. Int J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2009;3(1):55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casamonti M, et al. Andrographolide Loaded in Micro- and Nano-Formulations: Improved Bioavailability, Target-Tissue Distribution, and Efficacy of the “King of Bitters”. Engineering. 2019;5(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2018.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, et al. Andrographolide-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles enhance anti-cancer activity against head and neck cancer and precancerous cells. Oral Diseases. n/a(n/a). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Yang T, et al. Andrographolide inhibits growth of human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia Jurkat cells by downregulation of PI3K/AKT and upregulation of p38 MAPK pathways. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2016;10:1389–1397. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S94983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu C, et al. Andrographolide targets androgen receptor pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(2):151–159. doi: 10.1177/1947601911409744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forestier-Román IS, et al. Andrographolide induces DNA damage in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2019;10(10):1085–1101. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Q, et al. Cancer-associated adipocytes: key players in breast cancer progression. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0778-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menezes ME, et al. Chapter Eight - Genetically Engineered Mice as Experimental Tools to Dissect the Critical Events in Breast Cancer, in Advances in Cancer Research, K.D. Tew and P.B. Fisher, Editors. 2014. Academic Press. p. 331–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Skurk T, et al. Relationship between Adipocyte Size and Adipokine Expression and Secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):1023–1033. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roubert A, et al. The influence of tumor necrosis factor-α on the tumorigenic Wnt-signaling pathway in human mammary tissue from obese women. Oncotarget. 2017;8(22):36127–36136. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnäbele K, et al. Effects of adipocyte-secreted factors on cell cycle progression in HT29 cells. Eur J Nutr. 2009;48(3):154. doi: 10.1007/s00394-009-0775-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banerjee M, et al. Cytotoxicity and cell cycle arrest induced by andrographolide lead to programmed cell death of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0257-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pucci B, Kasten M, Giordano A. Cell cycle and apoptosis. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.). 2000. 2(4):291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Cheung H-Y, et al. Andrographolide Isolated from Andrographis paniculata Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Mitochondrial-Mediated Apoptosis in Human Leukemic HL-60 Cells. Planta Med. 2005;71(12):1106–1111. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim SC, et al. Andrographolide induces apoptotic and non-apoptotic death and enhances tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(5):3837–3844. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye J, et al. Non-apoptotic cell death in malignant tumor cells and natural compounds. Cancer Lett. 2018;420:210–227. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen M, Xie C, Liu L. Solubility of Andrographolide in Various Solvents from (288.2 to 323.2) K. J Chem Eng Data. 2010. 55(11):5297–5298.

- 47.Kumoro AC, Hasan M, Singh H. Effects of solvent properties on the Soxhlet extraction of diterpenoid lactones from Andrographis paniculata leaves. Science Asia. 2009;35(1):306–309. doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2009.35.306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar S, Dhanani T, Shah S. Extraction of Three Bioactive Diterpenoids from Andrographis paniculata: Effect of the Extraction Techniques on Extract Composition and Quantification of Three Andrographolides Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J Chromatogr Sci. 2013;52(9):1043–1050. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmt157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin H, et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of multiple NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductases from Andrographis paniculata. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;102:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thoo Y, et al. A binary solvent extraction system for phenolic antioxidants and its application to the estimation of antioxidant capacity in Andrographis paniculata extracts. Int Food Res J. 2013. 20(3).

- 51.Do QD, et al. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of Limnophila aromatica. J Food Drug Anal. 2014;22(3):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Babu PR, et al. Solubility Enhancement of Cox-II Inhibitors by Cosolvency Approach. 1970. - 7(- 2).

- 53.Dhanani T, et al. Effect of extraction methods on yield, phytochemical constituents and antioxidant activity of Withania somnifera. Arab J Chem. 2017;10:S1193–S1199. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luong D, Sephton MA, Watson JS. Subcritical water extraction of organic matter from sedimentary rocks. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;879:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albright PS, Gosting LJ. Dielectric constants of the methanol-water system from 5 to 55°1. J Am Chem Soc. 1946;68(6):1061–1063. doi: 10.1021/ja01210a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saha A, Tiwary AS, Mukherjee AK. Charge transfer interaction of 4-acetamidophenol (paracetamol) with 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone: A study in aqueous ethanol medium by UV–vis spectroscopic and DFT methods. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2008;71(3):835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chao C-Y, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 and inhibition of TPA-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression by andrographolide in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(8):1843–1851. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Webb AH, et al. Inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 decreases cellular migration, and angiogenesis in in vitro models of retinoblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):434. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3418-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang L, et al. VEGF is essential for the growth and migration of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(5):5085–5093. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pratheeshkumar P, Kuttan G. Andrographolide Inhibits Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell Invasion and Migration by Regulating MMP-2 and MMP-9 During Angiogenesis. Journal of environmental pathology, toxicology and oncology: official organ of the International Society for Environmental Toxicology and Cancer. 2011;30:33–41. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.v30.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie F, et al. TGF-β signaling in cancer metastasis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2017;50(1):121–132. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmx123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Islam M, et al. Andrographolide, a diterpene lactone from Andrographis paniculata and its therapeutic promises in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018. 420. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Chen CC, et al. Andrographolide inhibits adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells by suppressing C/EBPβ expression and activation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016;307:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koteswara Rao Y, et al. Flavonoids and andrographolides from Andrographis paniculata. Phytochemistry. 2004;65(16):2317–2321. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jeong JM, et al. Antioxidant and chemosensitizing effects of flavonoids with hydroxy and/or methoxy groups and structure-activity relationship. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2007;10(4):537–546. doi: 10.18433/J3KW2Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen H-W, Chen C-C. Andrographis paniculata ameliorates insulin resistance in high fat diet-fed mice and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019. 3(Supplement_1).

- 67.Jin L, et al. Andrographolide attenuates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;332(1):134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moradi B, et al. The most useful medicinal herbs to treat diabetes. Biomedical Research and Therapy. 2018;5(8):2538–2551. doi: 10.15419/bmrat.v5i8.463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]