Summary

Therapies based on glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) long-acting analogs and insulin are often used in the treatment of metabolic diseases. Both insulin and GLP-1 receptors are expressed in metabolically relevant brain regions, suggesting a cooperative action. However, the mechanisms underlying the synergistic actions of insulin and GLP-1R agonists remain elusive. In this study, we show that insulin-induced hypoglycemia enhances GLP-1R agonists entry in hypothalamic and area, leading to enhanced whole-body fat oxidation. Mechanistically, this phenomenon relies on the release of tanycyctic vascular endothelial growth factor A, which is selectively impaired after calorie-rich diet exposure. In humans, low blood glucose also correlates with enhanced blood-to-brain passage of insulin, suggesting that blood glucose gates the passage other energy-related signals in the brain. This study implies that the preventing hyperglycemia is important to harnessing the full benefit of GLP-1R agonist entry in the brain and action onto lipid mobilization and body weight loss.

Keywords: obesity, diabetes, glucagon-like peptide 1 analogs, glycemic control, tanycyte, metabolism, brain access, nutrient partitioning

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Brain entry and action of a GLP-1R agonist is modulated by peripheral glycemia

-

•

Hypothalamic tanycytes regulate GLP-1R agonist entry and effects on metabolism

-

•

Glycemic control of GLP-1R agonist entry in the brain is blunted in obesity

Bakker et al. show that insulin-induced hypoglycemia leads to better entry and action of GLP-1R agonist in the brain. Enhanced action of GLP-1R in the brain involves tanycytic release of VEGF and increases whole-body lipid oxidation. Obesity and high-fat feeding uncouple glycemic change and GLP-1RA entry in the brain.

Introduction

Obesity and correlated diseases are now clearly identified as a worldwide pandemic in both developing and developed countries (Molavi et al., 2006) and have more than doubled since 1980 (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight). Obesity is associated with increased mortality, notably due to a constellation of associated disorders, such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, reproductive diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and certain cancers, thus impacting upon large swathes of society and placing an enormous burden on health care resources. The last decade has witnessed a significant endeavor to efficiently develop alternative strategies aiming at restoring glycemia control and decreasing body weight.

While insulin treatment remains a major tool in the therapeutic arsenal to restore uncontrolled glycemia in diabetes, other existing therapies are based on peripheral peptides whose respective receptors are also located in the central nervous system. Among these peptides, the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which is secreted by pancreatic cells (Chambers et al., 2017), brainstem neurons (Holt et al., 2019), and from gut enteroendocrine cells upon nutrient transit. GLP-1 exerts several beneficial actions partly through its ability to enhance glucose-induced insulin release from pancreatic β cells (Barrera et al., 2011; Muller et al., 2019). This incretin action has fostered the development of GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists for the treatment of T2D and obesity. Despite pharmacological interventions combining insulin and GLP-1R agonists are on the market for the treatment of T2D, yet limited knowledge exists on the mechanistic interactions of these two molecules (Anderson and Trujillo, 2016; Gough et al., 2014; Moreira et al., 2018). Importantly, in addition to the incretin effects (Anderson and Trujillo, 2016), GLP-1 promotes satiety and lowers body weight (Muller et al., 2019). These actions are, at least in part, mediated through brain circuits dedicated to the regulation of energy balance (Dodd and Tiganis, 2017; Sisley et al., 2014; Taouis and Torres-Aleman, 2019).

Peripheral insulin is reported to access the brain either through regulated passage across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (Banks et al., 1997; Pardridge et al., 1985) or via circumventricular organs (CVOs) (Banks, 2019) and locally initiates signaling cascades through its cognate insulin receptor (InsR), which is highly expressed in several hypothalamic and extra-hypothalamic regions (Konner et al., 2011; Porniece Kumar et al., 2021; Vogt and Bruning, 2013). In both humans and rodents, impaired central insulin signaling has been associated with metabolic defects (Bruning et al., 2000; Dodd and Tiganis, 2017; Ferrario and Reagan, 2018; Fisher et al., 2005; Heni et al., 2015; Scherer et al., 2011).

Peripheral GLP-1 has also been implicated in body weight homeostasis. GLP-1 was found to modulate vagal afferents, while centrally produced GLP-1 can also serve as a central neurotransmitter (Baggio and Drucker, 2014; Burcelin and Gourdy, 2017; Lockie, 2013). At the central level, GLP-1 is produced by a distinct subset of neurons within the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and several studies now point toward an unequivocal role of GLP-1-dependent signaling in the control of body weight, food intake, and energy expenditure (EE) (Sisley et al., 2014). Recent studies suggest that peripherally administered GLP-1R agonists act on GLP-1R-expressing neuronal populations located within CVOs, such as the anorectic/catabolic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons of the arcuate nucleus (ARC) (Baggio and Drucker, 2014; Secher et al., 2014) and the GABAergic neurons of the NTS (Fortin et al., 2020).

Interestingly, while several studies have used direct brain administration of hormones and analogs to dissect out the mechanisms underlying their central actions, there is a paucity of knowledge regarding the physiological underpinnings by which endogenously secreted or pharmacologically administered hormones gain access to effector neurons located behind the BBB. Among the CVOs, the median eminence (ME) and the area postrema (AP), located near the third and fourth ventricles, respectively, represent check-points for circulating signals acting on ARC and NTS neurons (O'Rahilly and Farooqi, 2008a, 2008b), two key structures that regulate body weight dynamics. While being characterized by reduced fenestrated capillaries when compared with the ME, the ARC is enriched in tanycytes, a specialized glial cell type (Garcia-Caceres et al., 2019; Nampoothiri et al., 2022; Prevot et al., 2018). Tanycytes control the fenestration of blood vessels at the ME/ARC junction and facilitate the transport of blood circulating signals onto energy sensing ARC neurons (Balland et al., 2014; Langlet et al., 2013; Mullier et al., 2010; Rodriguez et al., 2010).

In particular, tanycytes have been shown to gate adaptive remodeling within the ME by controlling blood-brain signal exchanges in response to nutrients availability and plasma glucose (Balland et al., 2014; Langlet et al., 2013) to transport metabolic hormones, such as leptin that exerts key pro-insulinic effects on the pancreas by acting on hypothalamic neurons (Duquenne et al., 2021), and recent studies have highlighted the role of tanycytes in mediating the GLP-1R agonist liraglutide transport into the brain and action onto feeding and metabolic efficiency (Imbernon et al., 2022). We hypothesized that acute physiological fluctuations (plasma glucose, nutrients, and/or hormones) might regulate the ability of hormones and/or pharmacological analogs to exert their central actions by modulating their access to central structures. Considering the growing therapeutic need for poly-pharmacological strategies (e.g., on the co-administration of GLP-1R agonists and insulin) (Anderson and Trujillo, 2016), we explored whether and how insulin and GLP-1R analogs might exert coordinated/synergistic actions on energy homeostasis through direct and/or indirect modulation of BBB passage.

Using bioactive fluorescently labeled insulin and the GLP-1R agonist Exendin-4 (Ex-4), we show that peripherally administered insulin can initiate signaling cascades in the ME/ARC and potentiate accelerated Ex-4 access to AP/NTS and ME/ARC structures. In addition, we show that central detection of hypoglycemia, rather than direct insulin action, is instrumental to enhance Ex-4 brain access. While GLP-1R agonist injection alone induced a sustained increase in fatty acid oxidation, upon co-injection with insulin Ex-4 was able to partially oppose the lipogenic effect of insulin. We provide evidence that the release of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) by tanycytes is a player in the adaptive response of CVOs to glycemic changes. Finally, we show that exposure to an energy-rich diet leads to a specific uncoupling between hypoglycemia and the potentiation of Ex-4 entry in the brain.

Altogether, our data reveal that acute changes in systemic glycemia can rapidly modulate the access and action of peripheral metabolic signals onto relevant energy-related neurons behind the BBB, in tanycyte-expressing brain regions. Finally, in support of this hypothesis, we demonstrate that peripheral blood glucose negatively correlates with the ratio of central cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to systemic plasma insulin in humans, further indicating that low plasma glucose may be associated with increased blood-to-brain passage of metabolically active peptide hormones. The identified mechanism is of clinical relevance as combined therapies for the glycemic control of diabetes could serve as gatekeepers for brain access and action of GLP-1/insulin, which is crucial for whole-body energy homeostasis.

Results

Co-administration of insulin and Ex-4 reveals bidirectional metabolic actions

We first explored the metabolic consequences of insulin and Ex-4 co-administration. Using indirect calorimetry, in three groups of chow-fed C57Bl6J male mice (n = 8/group) fed a chow diet and lean at the time of the experiment we measured the metabolic efficiency, feeding patterns, and locomotor activity during a 4-day treatment period consisting of daily injections (2:00 p.m.) of insulin (24 nmol/kg, blue), Ex-4 (120 nmol/kg, red), or insulin + Ex-4 (24 nmol/kg, 120 nmol/kg, green) (Figure 1A). A 3-day baseline period was first acquired for all groups (n = 24) and presented as reference (black, Figure 1A). Consistent with previously described anorectic actions of GLP-1 (Baggio and Drucker, 2014; Barrera et al., 2011; Burcelin and Gourdy, 2017; Secher et al., 2014; Sisley et al., 2014), acute administration of Ex-4 decreased both daily (Figure 1B) and cumulative (Figure 1C) food intake either alone or in combination with insulin. These satiety-like responses were associated with reduced EE when compared with a baseline group (Figure 1D). Consistent with the body weight loss effect induced by the GLP-1R agonist, acute injection of Ex-4 triggered a sustained increase in fatty acid oxidation compared with control baseline (Figure 1E), and both Ex-4 and insulin + Ex-4 treatments were associated with a significant decrease in body weight compared with control condition (Figure 1G). Analysis of meal ultrastructure revealed that Ex-4 was efficient in decreasing meal number and size, even though a desensitization process may occur during the 4-day treatment (Figure S1). Consistent with feeding response to hypoglycemia (Fraley and Ritter, 2003; Hudson and Ritter, 2004), acute insulin administration led to a transient increase in food intake (Figures 1B and 1C). This response was associated with a slight decrease in nocturnal chow intake and overall cumulative food intake was significantly different from controls only during the first day (Figure 1C). In our hands, EE remained marginally affected when compared with baseline (Figure 1D). To discriminate between true mass-independent group effects, we performed a regression-based analysis (ANCOVA) with body weight as covariate of EE (MMPC, www.mmpc.org) for all conditions. We did not detect any significant interaction between BW and EE (vehicle n = 24 versus insulin n = 8, p = 0.537; vehicle n = 24 versus Ex-4 n = 8, p = 0.537; vehicle n = 24 versus insulin + Ex-4 n = 8, p = 0.721). In addition, acute insulin administration exerted a sharp and sustained decrease in fatty acid oxidation (Figure 1E) consistent with the anti-lipolytic and lipogenic action of insulin (Petersen et al., 1988; Thomas et al., 1979). When co-administered with insulin, Ex-4 opposed the hyperphagic response following hypoglycemia (Figure 1B) and induced a sharp rebound in fatty acid oxidation (Figure 1E). This result reveals the antagonistic action of GLP-1R agonist on feeding and metabolic substrate utilization, even under co-administration with insulin. Note that we only observed a decrease in locomotor activity when insulin and Ex-4 were co-administered (Figure 1F) as a possible result of reduced energy availability and/or low blood glucose levels. Our results support the idea that body weight loss, which was significant in both condition of Ex-4 administration (Figure 1G), is due to both reduction of feeding and shift toward peripheral lipid utilization (Sisley et al., 2014). It is important to note that, since mice were on chow diet, body weight loss achieved by Ex-4 administration on a short period was relatively low. This is in line with previous studies showing that GLP-1R agonist exhibits stronger effects on high-fat fed/obese mice as compared with lean/chow-fed mice (Simonds et al., 2019). We next explored whether the effect was a consequence of peripheral or brain-specific actions.

Figure 1.

Metabolic consequences of insulin and Exendin-4 co-injection

(A) Experimental setup for metabolic efficiency characterization of mice receiving a daily i.p. saline injection (baseline, gray) followed by a 4-day treatment period consisting of a daily injection (2:00 p.m.) of insulin (24 nmol/kg, blue), Exendin-4 (120 nmol/kg, red), or mix of insulin + Exendin-4 (24 nmol/kg, 120 nmol/kg, green). Graphs represent an average of a 3-day baseline (gray) or 3-day treatment periods for (B) food intake, (C) cumulative food intake, (D) energy expenditure, (E) calculated fatty acid oxidation, and (F) locomotor activity.

(G) Body weight changes upon treatment. n = 8 in each group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05. $p < 0.05, insulin versus vehicle. £p < 0.05, Ex-4 versus vehicle. #p < 0.05, insulin + Ex-4 versus vehicle. &p < 0.05, insulin + Ex-4 versus Ex-4. For statistical details, see Data S1.

Peripheral insulin accesses hypothalamic CVOs initiating IR-dependent signaling cascade

Using fluorescent and biologically active insulins (vivotag-750-labeled insulin: insulin_VT750 or Alexa 647-labeled insulin: insulin_Alexa 647) in combination with whole-brain light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) (Salinas et al., 2018), we assessed whether insulin directly accessed the brain. We found that peripherally administered fluorescent insulin can indeed access the ME and ARC hypothalamic regions (Figures S2A–S2F). Interestingly, this signal required an InsR-dependent mechanism since mice pre-treated with the IR antagonist S961 (180 nmol/kg) 30 min before systemic administration of insulin_VT750 failed to show fluorescent signals in the ARC (Figures S2A and S2B). To confirm our findings, the same experiment was repeated with Insulin-Alexa647 using confocal microscopy. Mice administered with Insulin-Alexa647 showed similar signal patterns (Figures S2C and S2D). Co-labeling analysis revealed that, 2 min after intravenous (i.v.) injection of Insulin-Alexa647, fluorescent insulin signals were detected in ME cellular elements expressing vimentin, a specific marker of tanycytes (Figures S2E and S2F). As for insulin_VT750, insulin_Alexa 647 was almost completely absent in the ARC when mice were pre-treated with S961 (Figures S2E and S2F). In addition to the brain entry of insulin, immunofluorescence analysis revealed that, after 10 min of i.v. injection, insulin was able to trigger IR downstream phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) in ME/ARC regions with an intense signal in vimentin-expressing tanycytes (Figure S2G). Western blot analysis of ME/ARC compared with whole mediobasal hypothalamic punches, revealed that phospho-Akt (Ser473), but not phospho-ERK (Thr202/Thr204), was preferentially induced in ME/ARC by peripheral insulin injection (Figures S2H–S2J).

Insulin and GLP-1 signaling components are differentially expressed in hypothalamic and AP/NTS tanycytes

Using similar approaches, we found that peripheral administration of Ex-4_Alexa 594 was detected in ME/ARC and AP (Figures S3A–S3D). Immediately after Ex-4 i.v. injection (10–15 s), the fluorescent signal was observed in both ME and AP (Figures S3A and S3B); however, a clear accumulation of signal was visible in the ME tanycytes (Figures S3A and S3B), suggesting that, at early time points, ME tanycytes are involved in Ex-4 transport while diffusing through fenestrated capillaries in the AP. In addition, 15 min after fluorescent Ex-4 i.p. injection, the signal was detected in the ARC and overlapped with GLP-1R immunoreactivity (Figures S3C and S3D). To understand the potential differences between ME and AP tanycytes, we performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) purification of tanycytes (Langlet et al., 2013). In brief, Tat-Cre chimeric protein was injected either in the third or fourth ventricle of tdTomatoloxP/+ mice, thus allowing cell-type-specific tagging of tanycytes (Langlet et al., 2013). Labeled tanycytes were then subjected to FACS (Figure S3E) followed by RT-PCR analysis. As shown in Figure S3F, transcripts related with signaling pathways of both GLP-1, like GLP-1R, and insulin, such as insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, were significantly enriched in the tanycytes of the ME compared with those of the AP, even though in both structures tanycytes expressed similar amounts of mRNA encoding for InsR and insulin-like growth factor receptor (Figure S3F). These data support the idea that only ME tanycytes may be actively involved in the transport of insulin and Ex-4 into brain CSF.

Peripheral insulin administration promotes the access of Ex-4 into hypothalamic/hindbrain structures

We next explored the action of peripherally injected insulin on brain access of Ex-4. LSFM-based whole-brain analysis (Salinas et al., 2018) was used to quantify the accumulation of Ex-4_VT750 after systemic administration. 2D planes extracted from LSFM clearly showed that the Ex-4_VT750 signal was detected in the ME/ARC, OLVT, AP, SFO, and choroid plexus (Figure 2A). Compared with vehicle, peripheral injection of insulin (2–240 nmol/kg) dose dependently increased the signal of Ex-4_VT750 in these brain areas (yellow arrow, Figures 2A and 2B). Moreover, using 3D projections we observed increased Ex-4_VT750 fluorescent signal in the brain vasculature as well as in ME/ARC (Figure S4A).

Figure 2.

Insulin-mediated hypoglycemia potentiates the access of GLP-1 analog Exendin-4 in the brain

(A) Selection 2D planes whole-brain light-sheet scanning to visualize fluorescent signals of Exendin-4_VT750 (120 nmol/kg, i.p.) together vehicle or insulin (240 nmol/kg, i.p.). The picture represents the arcuate nucleus (ARC), organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT), area postrema (AP), subfornical organ (SFO), and choroid plexus. (B) Quantification of hypothalamic Exendin-4_VT750 fluorescent signal normalized to vehicle in combination with insulin (2 and 240 nmol/kg, i.p.) and insulin receptor antagonist S961 + insulin (doses). n = 5–17/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, vehicle versus insulin.

(C) Experimental setting for hyperinsulinemic clamp controlled at either normal glucose or low glucose levels.

(D) Low or normal glucose during hyperinsulinemic conditions.

(E and G) Quantification of Exendin-4_VT750 fluorescent signal normalized to vehicle under high (162 ± 14 mg/dL) or low (74 ± 5 mg/dL) glucose conditions in (E) hypothalamus and (G) hindbrain.

(F and H) Correlation curve between Exendin-4_VT750 fluorescent signal intensity and blood glucose (BG) in (F) hypothalamus and (H) hindbrain. n = 10–11/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, vehicle versus insulin. For statistical details, see Data S1.

We next applied a recently developed approach that allows region-specific quantifications of fluorescent signals in an integrated brain atlas (Salinas et al., 2018). Using this method, we found that insulin exerted a dose-dependent action onto Ex-4_VT750 hypothalamic access that could be prevented by pre-treatment with the IR antagonist S961 (180 nmol/kg) (Figures 2B, S4B, and S4C). Importantly, this phenomenon required the integrity of GLP-1R activity since peripheral injection of insulin (2, 240 nmol/kg) failed to promote the access of the fluorescent GLP-1R antagonist Ex-9-39_VT750 despite similar change in glycemia (Figures S4D and S4E). These results indicate that insulin dose-dependently potentiates the GLP-1R agonist, but not GLP-1R antagonist passage, in the ME/ARC region.

Hypoglycemia rather than insulin itself gates the central access of GLP-1R agonist

Since the ME undergoes adaptive structural plasticity (higher permeability under fasting-induced hypoglycemia; Langlet et al., 2013) to match the energy status of the individual, we next explored whether brain insulin signaling per se or insulin-promoted hypoglycemia facilitated Ex-4_VT750 access in ME and AP. We therefore performed a hyperinsulinemic clamp (3.3 mU/kg/min) on awake mice in which glucose levels were set at either physiological (162 ± 14 mg/mL) or low (74 ± 5 mg/mL) concentrations. Ex-4_VT750 was administered intraperitoneally under constant hyperinsulinemia with blood glucose stabilized under normal or low levels (Figures 2C and 2D). Animals were sacrificed 15 min after Ex-4_VT750 administration and brains were processed for LSFM-based signal acquisition (Salinas et al., 2018). We found that, in a hyperinsulinemic state, the Ex-4_VT750 signal was higher in the hypothalamus of animals maintained at low glucose levels compared with the euglycemic controls (Figures 2E and 2G). Furthermore, regression analysis revealed an inverse correlation between low glucose levels and high Ex-4_VT750 fluorescence in both hindbrain and hypothalamic structures (Figures 2F and 2H). These data indicate that, although we cannot rule out a direct action of insulin on different brain regions, changes in glucose levels are necessary to promote Ex-4 brain access.

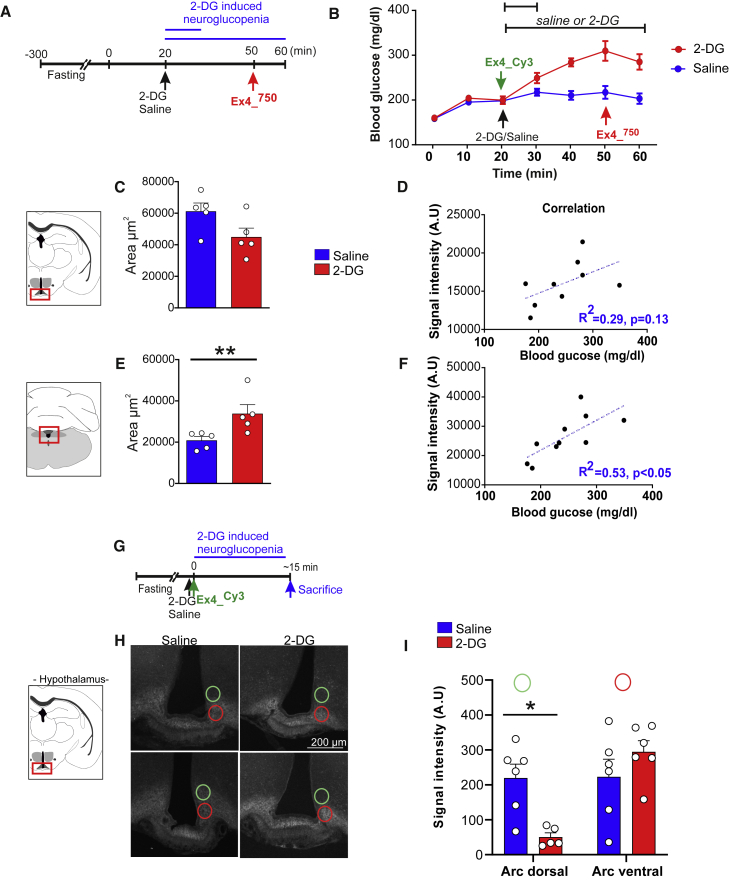

Next, we explored whether centrally detected glucoprivation could relay CVO adaptation to hypoglycemia. In that regard, we assessed whether central neuroglucopenia induced by 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) (250 mg/kg, i.p.) could affect the brain access of a GLP-1R agonist. Animals received either saline or 2-DG injections followed by intravenous administration of Ex-4_VT750 30 min after 2-DG injection (Figures 3A and 3B) and ∼10 min before sacrifice. The brains were dissected and processed as indicated previously, 10 min after Ex-4_VT750. The occurrence of a counter-regulatory response to 2-DG-induced neuroglucopenia was highlighted by increased blood glucose (Figure 3B). 2-DG injection was associated with an increase dispersion measured by the area of the Ex-4_VT750 signal in the hindbrain and a trend to decrease in the hypothalamus (Figures 3C and 3E). In the hindbrain, we found a significant correlation between blood glucose and Ex-4_VT750 signal (Figure 3F), indicating that the access of Ex-4_VT750 to the brain was associated to the degree of the counter-regulatory response. Importantly, while low blood glucose was correlated with an increase in brain passage through CVOs of Ex-4_VT750 (Figures 2 and S4A), here we found that hindbrain Ex-4_VT750 fluorescent signal (and to a lesser extend hypothalamus), was increased despite large counter-regulatory increase in blood glucose 30 min after 2-DG injection. This observation suggests that the adaptive changes occurring in CVOs to modulate Ex-4 passage might involve the detection of glucoprivation at a central level, which can potentially be decorrelated from peripheral glucose changes.

Figure 3.

Central detection of low glucose increases Exendin-4 access to the brain

(A) Experimental schedule of 2-DG (250 mg/kg, i.p.) injections before administration of Exendin-4_VT750 (120 nmol/kg, i.p.) at 10 or 30 min following 2-DG/vehicle injection, and (B) glycemic changes upon 2-DG-induced neuroglucopenia.

(C–F) Quantification of the volume of fluorescent signal dispersion in the arcuate (C) and hindbrain (E) area from Exendin-4_VT750 or Exendin-4_Cy3 in the hypothalamus and (C and D) hindbrain (E and F) structure using whole-brain laser-sheet microscopy. (D and F) Correlation curve between Exendin-4_VT750 fluorescent signal intensity and blood glucose in (D) hypothalamus and (F) hindbrain. n = 5–9 minimum in each group. ∗p < 0.05. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(G) Experimental setup for concomitant injection of vehicle or 2-DG (250 mg/kg) together with Ex-4_Cy3 (120 nmol/kg) ∼15 min before sacrifice.

(H and I) (H) Representative photomicrographs of Ex-4_Cy3 fluorescent distribution and (I) signal quantification in the dorsal (green circles) and ventral part (red circles) of the arcuate nucleus ∼15 min after 2-DG injection. n = 5–9/group. ∗p < 0.05. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. For statistical details, see Data S1.

Hence, to further define the dynamics of Ex-4 entry into the brain following neuroglucopenia, we performed a similar experiment in which animals were sacrificed at an early time point (∼15 min) following injection of both fluorescent Exendin-4Cy3 and 2-DG (Figure 3G). Confocal microscopy analysis in the ARC (Figure 3H) and AP (Figure S5) revealed that, even before any systemic changes in glucose (15 min after 2-DG injection), centrally detected glucoprivation resulted in the redistribution of the fluorescent Exendin-4Cy3 more ventrally toward the ME in the ARC region (Figures 3H and 3I), while the overall intensity in the ARC and AP remained unchanged (data not shown and Figure S5). Overall, these results support the notion that Ex-4 passage through hypothalamic CVOs and its distribution in hypothalamic structures can rapidly respond to changes in glycemia detected, at least in part, at the central level.

Tanycytic VEGF contributes to brain access and action of GLP-1 agonist

VEGF has been shown to be an important regulator of BBB plasticity (Dantz et al., 2002). In addition, tanycytic VEGF has been involved in the control of ME/ARC adaptations to fasting and hypoglycemia (Langlet et al., 2013). We therefore hypothesized that brain access and action of Ex-4 during insulin-mediated hypoglycemia could depend, at least in part, on tanycytic Vegfa. We first explored whether VEGF signaling could be involved in the action of hypoglycemia in promoting Ex-4_VT750 entry into the ME/ARC. Using similar approaches as described in Figure 2, we found that, while VEGF injection (0.1 mg/kg) enhanced Ex-4_VT750 signal in the hypothalamus to an extent comparable with insulin-mediated hypoglycemia, administration of the VEGF-R antagonist Axitinib (25 mg/kg) prevented the action of insulin on the access of Ex-4_VT750 to this region (Figures 4A and 4B). In addition, we also found that peripheral injection of the vasodilating prostacyclin analog sodium beraprost (BPS) (Kubota et al., 2011) similarly increased the Ex-4_VT750 signal in the ME/ARC (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

The access of Exendin-4 in the ARC under hypoglycemia involves tanycyte-borne VEGF

(A) Quantification of hypothalamic Exendin-4_VT750 (120 nmol/kg) fluorescent signal normalized to vehicle and (B) glycemic changes in response to VEGF (0.1 mg/kg, i.p.), insulin (240 nmol/kg, i.p. ) + VEGF, VEGF receptor antagonist Axitinib (25 mg/kg, i.p.), Axitinib alone, or the prostacyclin analog sodium beraprost (BPS 1 mg/kg, i.p.). n = 5–7/group. ∗p < 0.05, vehicle versus insulin. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(C) Model for tanycyte-restricted invalidation of Vegfa in TanycyteΔVegfa mice (Vegfalox/lox; third ventricle injection of TAT-CRE or AAV-CRE-GFP) and experimental setup for concomitant injection of vehicle or 2-DG (250 mg/kg) together with Ex-4_Cy3 (120 nmol/kg) ∼15 min before sacrifice.

(D and E) (D) Representative photomicrographs for Ex-4_Cy3 fluorescent distribution and (E) signal quantification in the dorsal (green circles) and ventral part (red circles) of the arcuate nucleus ∼15 min after 2-DG injection. Signal quantification was acquired on four to six brain sections from each animal, N = 2–5/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05.

(F) Glycemic change after saline (black, red) or insulin (0.75 U/kg, gray, orange) in control (black, gray) and TanycyteΔVegfa mice (red, orange).

(G) 3D fluorescent signal quantification in the ARC in normoglycemic (NG) and hypoglycemic (HG) conditions.

(H) Representative 2D planes from whole-brain light-sheet scanning to visualize fluorescent signal of peripherally injected Exendin-4_VT750 (120 nmol/kg) in the ME/ARC region of control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice.

(I) Signal quantification of fluorescent Exendin-4_VT750 in the dorsal (green circles) and ventral part (red circles) of the arcuate nucleus 60 min after insulin (0.75 U/kg) injection. Signal quantification was acquired on three brain sections from each animal, n = 2–4/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗ p value < 0.05, insulin versus vehicle. For statistical details, see Data S1.

Next, we generated mice lacking Vegfa in ME tanycytes. Selective ablation of Vegfa in tanycytes was achieved by using either intracerebroventricular injection of the chimeric protein TAT-CRE (Figure 4C) (Langlet et al., 2013) or AAV1/2-GFP or AAV1/2-CRE-GFP in VegfLox/LoxP mice to generate control and TanycyteΔVegf mice (Figure S5E; see STAR Methods). Selective ablation of Vegfa in tanycytes was first evaluated by confirming the co-expression of GFP in vimentin-immunoreactive tanycytic cell bodies and processes in mice injected with AAV 1/2-GFP viruses into the lateral ventricle (Figure S5D). In addition, FACS-based isolation of GFP-positive and -negative cells from the ARC revealed that tanycyte-specific mRNA (GPR50 and vimentin) were enriched in GFP-positive cells while POMC was enriched in GFP-negative cells (putative neurons) (Figures S5F–S5H). Furthermore, we show that Vegfa but not Vegfb was significantly decreased in GFP-positive cells from TanycyteΔVegf (VegfLox/LoxP:AAV-CRE-GFP) animals, but not in tanycytes from control mice (VegfLox/LoxP:AAV-GFP, Figures S5I–S5K).

First, we assessed how Vegfa ablation in tanycytes affected the ME/ARC distribution of Ex-4 in response to acute (∼15 min) 2-DG-induced neuroglucopenia (Figure 4C). As previously observed (Figures 3G and 3I), short-term neuroglucopenia triggered a change in Ex-4Cy3 signal distribution in a more ventral position close to the ME (Figures 4D and 4E) in control animals. However, TanycyteΔVegfa displayed a rather opposite pattern in which fluorescent Ex-4Cy3 was rather more dorsal (Figures 4D–4F), although the total fluorescence intensity was comparable between groups (data not shown). Next, we assessed how prolonged hypoglycemia induced by insulin affected the passage of Ex-4_VT750 in ME/ARC. Control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice received either saline or insulin (0.75 U/kg, i.p.) and Ex-4_VT750 was injected ∼15 min before sacrifice (Figure 4F). Consistent with previous observation (Figures 2A–2D), 2D fluorescence analysis in the ARC revealed an opposite trend for increase and decrease of signal in control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice, respectively, as a consequence of hypoglycemia (Figure 4G). Further analysis of 2D plane selection demonstrated a wider dispersion of Ex-4Cy3 signal in the dorsal ARC of control mice (Figures 4H and 4I) compared with TanycyteΔVegfa mice in which hypoglycemia-induced Ex-4Cy3 redistribution followed opposite trends (Figure 4I) despite similar changes in blood glucose (Figure 4F). Overall, these results suggest that tanycyctic Vegfa integrity is important to mediate Ex-4 distribution in the ARC in response to prolonged detection of glycemic changes.

We next assessed the metabolic consequences of Vegf loss in tanycytes. Metabolic efficiency was first assessed on chow diet-fed control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice during a 3-day daily i.p. saline treatment followed by a 3-day treatment period consisting of a daily injection of Ex-4, insulin or insulin + Ex-4. Animals were then exposed to 3 weeks of high-fat diet followed by a 3-day treatment period of a daily injection of Ex-4 (120 nmol/kg, red) or insulin + Ex-4 (Figure 5A). While control mice exhibited a more pronounced decreased in cumulative chow intake (Figure 5B) and body weight loss (Figure 5D) in response to insulin + Ex-4 compared with Ex-4 alone, these responses were blunted in TanycyteΔVegfa mice (Figures 5C and 5E). In addition, averaged fatty acid oxidation revealed a different metabolic baseline between control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice (Figures 5F and 5G) supporting the role of tanycytic Vegfa in central integration of metabolic signals.

Figure 5.

Metabolic action of Exendin-4 involves tanycyte-borne VEGF

(A) Experimental schedule for the characterization of metabolic efficiency in controls (Vegfalox/lox; ventricular injection of AAV-GFP) and TanycyteΔVegfa mice (Vegfalox/lox; ventricular injection of AAV-CRE-GFP) in response to daily i.p. saline injection (baseline, gray) followed by a 3-day treatment period consisting of a daily injection (2:00 p.m.) of Exendin-4 (120 nmol/kg, red), followed by insulin (20 nmol/kg, blue), and 3 days of mix of insulin + Exendin-4 (20 nmol/kg, 120 nmol/kg, green). Control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice were then exposed to a 3-week high-fat feeding regimen and reevaluated for their response to Exendin-4 or insulin + Exendin-4. Graphs represent averaged values for (B and C) cumulative food intake, (D and E) body weight change, (F and G) fat oxidation, and (H and I) food intake on chow diet. Three-day averaged cumulative food intake (J and K) and body weight change (L and M) through i.p. saline injection (black) followed by a 3-day treatment period consisting of a daily injection (2:00 p.m.) of Exendin-4 (120 nmol/kg, red) and 3 days of mix of insulin + Exendin-4 (20 nmol/kg, 120 nmol/kg, green) of control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice after exposure to high-fat diet. n = 8–5/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05. $p < 0.05, insulin versus vehicle. £p < 0.05, Ex-4 versus vehicle. #p < 0.05, insulin + Ex-4 versus vehicle. &p < 0.05, insulin + Ex-4 versus Ex-4. For statistical details, see Data S1.

Furthermore, compared with TanycyteΔVegfa mice control mice displayed a more pronounced and prolonged change in fatty acid oxidation (Figures 5F and 5G) and feeding (Figures 5H and 5I) as a difference between vehicle and treatment conditions, while change in fat oxidation in response to insulin was comparable with vehicle in TanycyteΔVegfa mice. In particular, fatty acid oxidation profiles were almost similar between vehicle and insulin conditions in TanycyteΔVegfa (Figures 5F and 5G) despite similar glycemic change achieved by a single i.p. insulin injection (vehicle/insulin: 62% ± 5.7% in controls and 52% ± 2.08% in TanycyteΔVegfa). In addition, calculation of the absolute sum of the area under the curve (ΔAUC) for fatty acid oxidation changes in the few hours following the injection revealed a blunted response to the insulin + Ex-4 treatment in TanycyteΔVegfa (Figures S6A–S6D) compared with control mice.

After a 3-week high-fat diet, we observed qualitatively similar decrease in high-fat feeding in response to Ex-4 and insulin + Ex-4 treatments in both control and TanycyteΔVegfa mice (Figures 5J and 5K). However, when compared with control mice, the decrease in body weight achieved by either treatment was blunted in TanycyteΔVegfa (Figures 5L and 5M).

Overall, these results suggest that tanycytic Vegfa relays, at least in part, the changes in metabolism elicited by acute Ex-4, insulin, and Ex-4 + insulin.

The coupling between hypoglycemia and brain access of Ex-4 is impaired following exposure to caloric-rich diet

Finally, we explored the consequence of high-fat high-sugar (HFHS) exposure on the coupling between glucoprivation and brain access of Ex-4. In these conditions, adult male C57/Bl6J mice were exposed to a 5- or 10-week HFHS regimen and, in each condition, we assessed the ability of a single injection of insulin (240 nmol/kg) to promote BBB passage of Ex-4_VT750. HFHS-exposed mice had a significant increase in body weight compared with chow-fed controls (Figure 6A). Insulin (240 nmol/kg) was able to trigger a similar decrease in blood glucose in both HFHS groups (Figure 6B). However, despite a similar decrease in blood glucose, the ability of hypoglycemia to promote Ex-4_VT750 brain access was drastically decreased between 5 and 10 weeks of HFHS exposure (Figures 6C and 6D), whereas in the hindbrain, after 5 weeks of HFHS diet, insulin-induced hypoglycemia was still able to facilitate Ex-4 passage (Figures 6C and 6E). The correlation between blood glucose changes in response to insulin and Ex-4_VT750 signal intensity revealed that, in both hindbrain and hypothalamic structures, the coupling between hypoglycemia and brain access of GLP-1R agonists was impaired following 10 weeks of HFHS exposure (Figure 6F and 6G).

Figure 6.

Exposure to energy-dense food leads to uncoupling between hypoglycemia and Exendin-4 brain access

(A) Body weight increase in mice exposed to 5 or 10 weeks of high-fat high-sucrose (HFHS) diet.

(B) Changes in blood glucose upon insulin (240 nmol/kg, i.p.) followed by the fluorescent Ex-4_VT750 (120 nmol/kg, i.p.).

(C) Horizontal, orbital plane digital sections acquired with whole-brain light-sheet microscopy of fluorescent signals are overlaid onto the Common Coordinate Framework version 3 (CCFv3) template from the Allen Institute for Brain Science (Oh et al., 2014) and show Ex-4_VT750 signals in the brain of mice after 5 or 10 weeks of HFHS diet treated with vehicle or insulin (240 nmol/kg).

(D and E) Quantification of Ex-4_VT750 signal intensity in the hypothalamus (D) or hindbrain (E) structures following 5 weeks (blue, red) or 10 weeks (black, green) of HFHS diet.

(F and G) Correlation of blood glucose levels (mg/dL) upon insulin injection. Fluorescent signal intensity of Exendin-4_VT750 in (F) hypothalamic and (G) hindbrain regions. n = 5–6/group. ∗p < 0.05. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. For statistical details, see Data S1.

Blood glucose negatively correlates with central insulin content in humans

Altogether our results suggest that, within a physiological range, acute perturbations of blood glucose promote rapid alterations in local brain access and action of Ex-4. Indeed, we found that either systemic insulin-induced hypoglycemia or central neuroglucopenia (2-DG) promoted accelerated Ex-4 entry in the hypothalamus and hindbrain. We next explored the translatable aspect of this phenomenon in humans. We reasoned that this mechanism, in which lower plasma glucose leads to higher blood-to-brain passage of peptide hormones, could potentially also affect other circulating energy-related signals. In a cohort of non-obese individuals (N = 140, characterization in Table S2), we addressed the correlation between plasma glucose and the ratio of central CSF and systemic plasma insulin that reflects blood-to-brain insulin transport. When plasma glucose in fasted patients was regressed onto CSF/plasma insulin levels, we found a robust inverse correlation (p < 0.001), showing that the lower the blood glucose the higher the ratio between central/systemic insulin (Figure 7). This result supports the notion that lower plasma glucose acts as a gatekeeper for central transport/access of blood-borne energy-related peptides also in humans. Importantly, while there was a negative correlation between the ratio of insulin in CSF/serum and body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.0007, r2 = −0.079), the correlation between insulin in CSF/serum and glucose was independent of BMI and remained significant after adjustment for BMI (p < 0.0001).

Figure 7.

Central insulin content in humans correlated with plasma glucose

Correlation of CSF/serum insulin ratio with plasma glucose in 140 human subjects (p < 0.0001, r = 0.50). For statistical details, see Data S1.

Discussion

In this study we show, when co-administered with insulin, Ex-4 opposes the action of insulin onto fuel partitioning toward glucose utilization by promoting a shift toward increased fatty acid oxidation (Figure 1). Using fluorescent-labeled molecules, we were able to visualize that both insulin and Ex-4 can access ARC neurons and confirmed that the insulin-mediated signaling cascade (phospho-Akt) was rapidly initiated in the ME/ARC area (Figure S2). In an early time point after Ex-4 injection, we found an accumulation of Ex-4 signal in tanycytes residing in the ME but not in the AP. This was associated with increased mRNA content for GLP-1R and InsR signaling in tanycytes of the ME/ARC compared with tanycytes in the AP/NTS region, suggesting that the InsR/GLP-1R tanycytic signaling is fostered in the ME/ARC (Figure S3). Surprisingly, peripheral insulin injection accelerated the access of fluorescently labeled Ex-4, but not the GLP-1R antagonist Ex-9-39, in most CVOs, including ME/ARC and AP/NTS regions (Figures 2 and S4).

In fact, we discovered that the degree of hypoglycemia, rather than insulin itself, correlated with an increased Ex-4 fluorescent signal in both the hypothalamus and the hindbrain (Figures 2C–2H). This suggests that insulin signaling onto ME/ARC tanycytes did not confer a specific advantage for the access of GLP-1R agonist to the brain via CVOs but rather that other mechanisms might be involved.

The response of CVOs to hypoglycemia is, to a certain extent, relayed by central glucoprivic sensing, since 2-DG-induced glucopenia promoted rapid adaptive distribution of Ex-4 in hypothalamic structures (Figures 3G–3I) followed by a change in hypothalamic and hindbrain Ex-4 abundance (Figure 3). Using pharmacological and genetic approaches, we show that the integrity of tanycytic VEGF-A is required for the adaptive responses of the BBB at CVOs to glycemic changes (Figure 4) and the consequent effect of Ex-4 on fatty acid oxidation (Figure 5). In addition, we demonstrated that exposure to an energy-rich diet induces a progressive defect in the adaptive access of Ex-4 to the brain in response to insulin-mediated glycemic changes (Figure 6). These results raise the possibility that obesity and/or high-fat feeding alters the ability of tanycytes to respond to acute changes during glycemia. Finally, we provide evidence that, in humans, glycemia also correlates with blood-to-brain entry of the energy-related signals: insulin (Figure 7).

Altogether, these results support the notion that acute changes in plasma glucose, detected at the central level, induce a rapid adaptive modification of brain access and action of energy-related signals. In the framework of insulin/GLP-1R agonist co-treatment, our data support a model where tanycytic VEGF-A relays the action of insulin-mediated hypoglycemia onto ME/ARC entry and the action of the GLP-1R agonist. Indeed, to mediate their action, circulating signals need to reach neurons that lie behind the BBB. First-order neurons, such as AgRP and POMC neurons, have an exquisite location close to the capillary loops arising from the ME (Schaeffer et al., 2013), with a tightly regulated permeability that allows central access of circulating molecules via CVOs (Banks, 2019; Prevot et al., 2018). The permeability of the ME vascular loops reaching the ARC is tightly regulated by tanycytes, which are not only glucose-sensing cells (Frayling et al., 2011), but also cells translating this glucose signal to glucose-insensitive POMC neurons regulating feeding (Lhomme et al., 2021) and one of the main sources of VEGF-A in the ME (Jiang et al., 2020; Langlet et al., 2013). The tanycytes regulate the direct access of blood-borne molecules to ARC neurons by controlling capillary fenestration. Hence, the microenvironment determined by the structure of the local capillaries and tanycyte-mediated signaling might confer to each CVO an idiosyncratic and distinct ability to integrate changes in nutrient availability and adapt blood-to-brain passage of metabolic signals. This hypothesis is in line with studies from Secher et al. (2014) and Fortin et al. (2020) demonstrating that the AP is not required for food intake and body weight-reducing effects of acutely delivered liraglutide, while GLP-1R signaling onto NTS neurons mediates part of the acute anorectic effects of liraglutide. In addition, this hypothesis is strongly comforted by the recently described role of ME tanycytes in the transport and action of the GLP-1R agonist liraglutide (Imbernon et al., 2022).

The brainstem has also been demonstrated to be an important mediator for body weight lowering by GLP-1R agonists, such as semaglutide (Gabery et al., 2020), and our results do not preclude the possibility that GLP-1R agonists may also act on other cell types of the NTS (Fortin et al., 2020). Indeed, our study suggests that glycemic changes can modulate the passage of GLP-1R agonist in hindbrain and hypothalamic structures through tanycyte-dependent and -independent mechanisms, and at different time frames. The action of GLP-1R agonists on both ARC and hindbrain cells could ultimately act in synergy, and possibly throughout different timescales, to mediate the long-term body weight loss action of GLP-1R agonists. The contribution of ARC neurons to the action of GLP-1R agonists on lipid substrate utilization is well in line with previous studies showing that (1) peripheral and intra-arcuate injection of Ex-4 can oppose the decrease in lipid oxidation induced by centrally delivered ghrelin (Abtahi et al., 2016) and (2) GLP-1R agonists enhance triglyceride clearance in humans (Whyte et al., 2018).

Overall, these observations fit with a concept where appetite suppression and fat mobilization resulting from a combinatorial action of peripherally administered GLP-1R agonists and insulin both contribute to weight loss. It is probable that the timing by which GLP-1R agonists reach hypothalamic and brainstem targets will be influenced by adaptive mechanisms governing peptide entry into these regions through respective distinct CVOs. One can therefore envision an orchestrated response pattern with a first acute response evoked in the vagus nerve and in the AP/NTS, followed by a second, more sustained, increase in body weight loss and favored lipid utilization through action on ARC neurons. Our data also highlight that the increase in fat oxidation induced by the GLP-1R agonist can oppose the lipogenic action of insulin. In theory, in a context of both excessive body weight and uncontrolled glycemia, achieving glucose control while limiting insulin-mediated lipogenesis and body weight gain would probably have beneficial output on metabolic syndrome (Muller et al., 2019).

This hypothesis agrees with recent phase III data from the Semaglutide STEP program that show clearly that weight loss induced by Semaglutide 2.4 mg is strikingly reduced in patients with obesity and T2D relative to non-diabetic patients with obesity (Davies et al., 2021; Wilding et al., 2021). In the same line, in the Obesity and Prediabetes trial (Pi-Sunyer et al., 2015) (overweight or obese patients but without T2D), weight loss was 8% with liraglutide compared with 5.4% in patients with diabetes (Wing et al., 2011). Indeed, in the STEP 1 trial, overweight or obese people but without T2D, bodyweight loss achieved by semaglutide 2.4 mg was 14.9% compared with 2.4% in patients with both obesity and T2D (Wilding et al., 2021). These patient data are reminiscent of our results showing that exposure to a 10-week HFHS diet decreases the CVO adaptive response to hypoglycemia leading to blunted Ex-4 entry in the brain when compared with the 5-week prediabetic condition (Figures 6F and 6G). In addition, clinical studies have highlighted that GLP-1R agonists show better efficacy for therapy in non-diabetic versus diabetic obese individuals (Davies et al., 2021; Pi-Sunyer et al., 2015; Wilding et al., 2021; Wing et al., 2011). Our study provides one possible mechanism by which to achieve better glucose control that might allow a better entry, action, and benefit of GLP-1R agonists and potentially other energy-related signals, including gut-derived peptide. Conversely, uncontrolled glycemia might prevent the full action of energy-related peptide in the brain. Importantly, though, our data cannot rule out that this phenomenon is a more general one that will affect brain access of a variety of signals.

While our study holds an interesting avenue for better understanding and optimization of the action of circulating signals onto central regulation of metabolism, further studies are warranted to fully depict by which mechanisms peptides/drugs access the brain under glycemic changes and how they may circumvent/correct the default acquired during nutrient overload and obesity.

Limitations of the study

A limitation of our study is that we do not provide a mechanism by which HFHS exposure uncouples brain responses to hypoglycemia. Previous reports have argued that exposure to energy-dense food and altered nutrient sensing can impair tanycyte functions (Balland et al., 2014; Langlet et al., 2013) and also trigger inflammatory-like responses in the hypothalamus of humans and rodents (Andre et al., 2017; Arruda et al., 2011; Thaler et al., 2012; Banks, 2003; Banks et al., 1999, 2004). In addition, to capture the status of Ex-4 transport, while mitigating further metabolic action, we injected the fluorescent analog 15 min before sacrifice. In this time window we cannot rule out that differences observed in Ex-4 signal in the brain might be due to change in time-dependent kinetics. Furthermore, GLP-1R is expressed in astrocytes and, given the prevalent role of astrocyte-endothelial transport it is very likely that, under various physiological condition, GLP-1R expressed onto astrocytes might play a significant role in GLP-1R agonist function in the brain (Chowen et al., 1999; Iwai et al., 2006; Klegeris, 2021; Schonhoff and Harms, 2018). Finally, chronic deletion of Vegfa in tanycytes will most certainly modify local entry of a variety of circulating energy-related signals which will lead to an altered metabolic baseline.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse GFP | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: A-11122; RRID: AB_221569 |

| Chicken polyclonal anti-mouse Vimentin | Merck Millipore | Cat#AB1620, RRID: AB_90774 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Phospho-akt (ser473) (D9E) XP® antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#:4060 RRID: AB_2315049 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #9272 RRID: AB_329827 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #9101 RRID: AB_331646 |

| Anti-β-Actin antibody, Mouse monoclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A1978 RRID: AB_476692 |

| Mouse monoclona anti-GLP-1R antibody clone 7F38A2 | Novo Nordisk (Jensen et al., 2018) | N/A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse GFP | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: A-11122 RRID: AB_221569 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-chicken IgG, Alexa Fluor 568 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A11041 RRID: AB_2534098 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A11008 RRID: AB_143165 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| AAV1/2-CAG-eGFP | Vector Biolab | N/A |

| AAV1/2-CAG-iCre/eGFP | Vector Biolab | N/A |

| AAV1/2-Dio2::Cre | Muller-Fielitz et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| TAT-Cre fusion protein | Peitz et al., 2002 | N/A |

| Insulin | Novo Nordisk | Flex pen, 8-9670-79-202-2 |

| S961 | Novo Nordisk | N/A |

| Sodium beraprost (SBP) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#: 88475-69-8 |

| Exendin 9-39 | Novo Nordisk | N/A |

| Exendin 9-39 | Novo Nordisk | N/A |

| Exendin 4 | Novo Nordisk | N/A |

| Exendin 4_VT750 | Novo Nordisk | N/A |

| Exendin 4_Cy3 | Novo Nordisk | N/A |

| Recombinant mouse VEGF 164 | RDS | Cat#293-VE |

| RNaseOUT™ | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: 10777019 |

| Hoechst 33,258 (pentahydrate bis-benzimide) | Invitrogen | RRID:AB_2651133 |

| DAPI | Vectashield | Cat#H-1200 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat##T8787 |

| BSA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat## A9418 |

| Normal goat serum | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat## 9663 RRID: AB_2810235 |

| Normal donkey serum | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D9663, RRID: AB_2810235 |

| Axitinib | LC Laboratories | Cat#A-1107 |

| Alexa 555 | Invitrogen | Cat#A20501MP |

| Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P5726 |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Roche | Cat#11836153001 |

| 2-deoxyglucose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#8375 |

| tetrahydrofuran | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#401757 |

| dibenzylether | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#3363 |

| Mowiol | Merck Millipore | Cat#: 475904 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Papain Dissociation System | Worthington Papain | Cat#: LK003150 |

| TaqMan® PreAmp Master Mix Kit | Applied Biosystems | Cat#: 4366128 |

| SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: 18080093 |

| Northern Lights Mercodia Total GLP-1 NL-ELISA | Mercodia | Cat#: 10-1278-01 RRID: AB_2892202 |

| RNAscope® Multiplex Fluorescent Kit | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat#: 320850 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Data S1 | This paper | All figures corresponding statistical details. |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mus musculus: tdTomatoloxP−STOP-loxP | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No.007914 RRID: MSR_JAX:007,914 |

| Mus musculus: Tg(CAG-BoNT/B,EGFP)U75-56wp/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No. 018056 RRID: IMSR_JAX:018,056 |

| Mus musculus: C57Bl/6J | Janvier | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Phenomaster TSE Systems GmbH | TSE Systems GmbH | N/A |

| MATLAB v2019b | The MathWorks, Inc. | RRID: SCR_001622 |

| MetaMorph | Molecular Devices LLC | RRID: SCR_002368 |

| EE ANCOVA analysis tools | NIDDK Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Centers (MMPC, www.mmpc.org) | http://www.mmpc.org/shared/regression.aspx |

| Imaris Bitplane software (Imaris x64 7.5.1 or 9.7.2) | Bitplane | https://imaris.oxinst.com/products/imaris-essentials |

| ImageJ | NIH | RRID: SCR_003070 |

| Photoshop CC | Adobe Systems | RRID: SCR_014199 |

| GraphPad PRISM 8.0 | GraphPad Software | RRID: SCR_002798 |

| Other | ||

| Glucofix premium | A. Menarini diagnostics | #43408 |

| Glucofix sensor | A. Menarini diagnostics | #38493 |

| Chow Diet | Safe diets | #A03 |

| High-Fat high-Sucrose Diet | Brogaarden | #D12451 Research Diet |

Resource availability

Lead contact

-

•

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Serge Luquet (serge.luquet@u-paris.fr).

Materials availability

-

•

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental models and subject details

Animals

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with approved national regulations of both France and Denmark, which are fully compliant with internationally excepted principles for the care and use of laboratory animals, and with animal experimental licenses granted by either the Animal Care Committee University Paris Diderot-Paris 7 (CEB-14-2016), the Danish Ministry of Justice and the Institutional Ethics Committees for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals of the University of Lille and the French Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research (APAFIS#2617-2015110517317420 v5) and under the guidelines defined by the European Union Council Directive of September 22, 2010 (2010/63/EU). C57Bl6J male mice (10-18 weeks) were housed 5 per cage or individually when required for the experiment, in standard, temperature-controlled condition with a 12-hour-light/dark cycle. The mice had ad libitum access to water and regular chow, unless otherwise stated. B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J i.e tdTomatoloxP−STOP-loxP mice, (Stock No.007914; RRID:IMSR_JAX:007,914) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and VegfaloxP/loxP mice (Gerber et al., 1999) were a gift from N. Ferrara (Novartis) #49} all C57BL/6J background.

Analytical procedures in humans

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood (serum and NaF-plasma for glucose measurements) collection was performed under fasting conditions between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. and subjects with normal CSF cell counts on the XN-10 hematology analyzer (Sysmex, Norderstedt, Germany) were included in the study. We included patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) as this enabled a highly structured, standardized and fast collection of specimens in the frame of the prospective ABCPD study (Sulzer et al., 2018). Such a high-quality collection especially of CSF is almost impossible in comparably large cohorts of healthy subjects, and we are not aware of any literature reporting about glucose pathway alterations in PD. Plasma and CSF glucose were measured immediately after collection on the ADVIA XPT clinical chemistry analyzer (hexokinase method). Plasma and CSF insulin levels were determined by an ADVIA Centaur XPT chemiluminescent immunoassay system after testing linearity and recovery for insulin in CSF (both instruments from Siemens Healthineers, Eschborn, Germany). The variation of this assay in CSF at an insulin concentration of 8 pmol/L was 12%. The ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Tuebingen approved the study (686/2013BO1), and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table S2 contains the characteristics of the participants.

Method details

Hyperinsulimic high/low glycemic clamp

Catheter was chronically inserted in the jugular vein under anesthesia and mice recovered for one week before starting the experiment. Mice were food deprived for 5 h to establish stable blood glucose levels. Mice were connected through the jugular vein catheter in the clamp system and after 30 min injected with insulin bolus (100 mU/kg) and continuous maintained with 3.3 mU/kg/min Insulin (Novorupid, Flex pen, 8-9670-79-202-2), 2 ul/min speed with pump. Mice were either maintained on glucose levels between 140 and 160 mg/dL (high) or maintain on glucose levels between 70 and 80 mg/dL (low) controlled by 30% glucose solution connected to the clamp. For 140-160 mg/dL (high glucose), the pump was started 10 min after insulin bolus with speed at 4ul/min. For 70-80 mg/dL (low glucose), glucose perfusion only started when BG levels dropped to 60mg/dl within 30 min. Blood glucose was measured every 10 min during the entire experiment by tail cut and measured by Glucofix glucose analyzer. After approximately 90 min, when stable high or low glucose was established, mice were injected with fluorescent labeled Exendin4 (Exendin4_VT750, 120 nmol/kg, Novo Nordisk) 15 min prior to sacrifice, followed by fixation perfusion (10 mL Saline with 20 U/ml heparin and 10mL 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin) and dissection of the brain. Tissues were stored in 10% NBF 4°C until further processing.

2DG-induced neuroglucopenia

Central neuroglucopenia was induced by 250 mg/kg of 2-deoxyglucose (Sigma) injected ip after 5 h of food deprivation. ∼10 min prior to sacrifice and 30 min after 2-DG injection, animals were injected with fluorescent Exendin-4 (Exendin4_VT750 or Exendin4_Cy3, 120nMol/kg) at early (15min) or late (40min) time points.

Compound and doses

Insulin VT750 was used i.v. at 2 to 240 nM/kg, and mice were sacrificed 10-15 s or 15 min after injection. S961 (NOVO NORDISK, (Schaffer et al., 2008)) was used i.v. at 1060 μmol/kg or 180nmole/kg and injected 30 min prior insulin administration.

Exendin-4 VT750, Exendin-4 CY3, Exendin-9-39 VT750 were administered at 120nmol/kg 15 min prior to sacrifice. Recombinant mouse VEGF (RDS) was delivered i.p. at 60 μg/kg as previously described (Langlet et al., 2013). Axitinib (in DMSO, LC Laboratories, France) was delivered i.p. at 25 mg/kg as described in (Langlet et al., 2013). Exendin-4 VT750, Exendin-4 CY3, Insulin VT750, Exendin-9-39 VT750 and insulin were kindly provided by Novo Nordisk. The vasodilating agent Sodium beraprost (BPS, Sigma Aldrich ref no: 88,475-69-8) was used at 1 mg/kg according to (Kubota et al., 2011)

Tanycyte-specific VegfA invalidation

Tanycytic specific knockdown of VEGFa was performed in isoflurane-anesthetized 8-weeks old VegfaloxP/loxP or tdTomatoloxP−STOP-loxP VegfaloxP/loxP male mice by stereotactic injection of either TAT-Cre (Experimental group in Figures 4C–4E) or AAV1/2-GFP (AAV1/2-CAG-eGFP; serotype 1:2 chimeric; titer = 1.2 x 1013 GC/mL; Vector Biolabs) to produce control or AAV1/2-CRE-GFP (AAV1/2-CAG-iCre/eGFP; serotype 1:2 chimeric; titer = 2.8 x 1013; Vector Biolabs) or AAV1/2 Dio2:Cre (serotype 1:2 chimeric, 0.5 × 1010 genomic particles μl−1, produce as previously described (Muller-Fielitz et al., 2017)) to produce TanycyteΔVegfa mice. TAT-CRE injections was performed directly in the third ventricle (2 μL; 0.3 μL/min; anteroposterior/midline/dorsoventral coordinates: −1.7 mm/0 mm/–5.6 mm) while AAV virus Injections were performed in the lateral ventricle (2 μL; at 0.2 μL/mim; anteroposterior, −0.3 mm; midline, −1 mm; dorsoventral, −2.5 mm), 2 weeks before starting the experiments. (experimental group Figures 4G–4I, 5, S5, and S6).

Isolation of tanycytes by FACS

The ME and AP from TAT-Cre injected tdTomatoloxP−STOP-loxP and the ME of AAV1/2 GFP control or AAV1/2 GFP + AA1/2 Dio2:Cre injected VegfaloxP/loxP mice were microdissected, and enzymatically dissociated using Papain Dissociation System (Worthington Papain, Cat#: LK003150) to obtain single-cell suspensions as described before (Messina et al., 2016). Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) experiments were performed using an EPICS ALTA Cell Sorter Cytometer device (Beckman Coulter). The cell sort decision was based on measurements of tdTomato fluorescence or EGFP fluorescence (Tomato: excitation 488nm, detection: bandpass 675 ± 20nm; EGFP: excitation: 488 nm; 50 mW; detection: EGFP bandpass 530/30 nm, autofluorescence bandpass 695/40 nm) by comparing cell suspensions from non-infected brain sites (the cortex) and infected brain sites (median eminence). For each animal, 4000 cells tdTomato positive or 200 cells EGFP positive and negative cells were sorted directly into 10μL extraction buffer: 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.4 U/μl RNaseOUT (Thermo Fisher).

Tissue processing for laser sheet microscopy analysis

For light sheet fluorescent microscopy, the tissues were dehydrated in increasing concentrations (50 vol%, 80 vol%, 96 vol%, 2 × 100 vol%) of tetrahydrofuran (Sigma), at 3 to 12 h per step. The dehydrated sections were then cleared until transparent by incubating with 3 × dibenzylether (Sigma) for 1 to 2 days in total. For immunohistochemistry, tissues were immediately saturated in 20% sucrose solution in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C, followed by 4

embedding and freezing in tissue teck. Brain transparisation was performed as previously described (Renier et al., 2014; Salinas et al., 2018).

Light sheet microscopy

Visualization of fluorescence was performed with a light sheet ultramicroscope coupled to a SuperK EXTREME (EXR-15) laser system (LaVision). The samples were scanned in 5- or 10-μm steps at excitation/emission settings of 560/620 or 620/700 nm for autofluorescence signal and 710/775 nm for specific signal of exendin4750 or insulin750. All samples were scanned with identical settings in each individual experiment. Images were generated using Imaris Bitplane software (Imaris x64 7.5.1 or 9.7.2). The fluorescent signals shown in Figures 3 and 6 are unmixed signals. The estimated auto-fluorescence contribution in the specific channel was calculated and removed based on ratios of voxel intensities between selected voxels in the autofluorescence recording and the corresponding voxels in the specific recording. The unmixing algorithm was written in MATLAB (Release, 2012b; MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, United States) and applied as an XT-plugin in Imaris (Release 7.6.5, Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland). Quantification of 3D signal intensities in Figure 4 was performed in manually drawn ROI’s of ARC and ME using Imaris 9.7.2 with a fixed baseline threshold of fluorescent signal in the specific channel.

Immunohistochemistry

Brains were sectioned into 30-μm cryosections covering the hypothalamus. All sections were collected and consecutively sampled on cryoslides and stored in −80°C. Sections were blocked in TBS containing donkey serum or PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 and stained for Vimentin (Merck Milliproe #: AB5733 1:2000) and phospo-Akt (Ser473) (CST #4060 1:50) in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100/0.2% BSA at 4°C overnight. Brain sections were counterstained with Hoechst nuclear stain (1:10,000 μL in dH2O). Images were obtained using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope. Tissue processing: tissues are just after dissection saturated in 20% sucrose solution in 4%PFA overnight at 4°C, followed by embedding and freezing in tissue teck. GLP-1R antibody clone 7F38A2 was produced and fully validated by Novo Nordisk (reference in.(Jensen et al., 2018)).

GFP immunohistochemistry

Brains were perfused in 4% PFA and post-fixed for 24 h and then kept in 0.01M PBS-0.05% sodium azide until further processing. Brain sections of 30 μm were cut and free-floating sections were blocked in an incubation solution of PBS, 0.25% BSA (BSA, A9418, Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.3% Triton X-100 (T8787, Sigma-Aldrich) with 4% normal goat serum (D9663, Sigma-Aldrich, RRID:AB_2810235) for 2h at room temperature (RT, 20–25°C). Then, sections were incubated with rabbit GFP antibody (1:500, A11122, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A-11122, RRID:AB_221569) and chicken anti-vimentin (1:500; Millipore, catalog no. AB1620, RRID:AB_90774) in the same blocking buffer for 48h in agitation at 4°C. After PBS rinses, immunoreactivity was revealed with Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:400, A11008, Invitrogen, RRID:AB_143165) and Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated secondary antibody goat anti-chicken IgG (1:4700, A11041; RRID: AB_144696) for 90 min. After Hoechst 33,258 (pentahydrate bis-benzimide, 1μg/mL, Invitrogen, RRID:AB_2651133) incubation for nuclei visualization, sections were mounted in slides and covered with mount containing Mowiol medium (Calbiochem, Merck Millipore).

Confocal microscopy

For hypothalamic Exendin-4Cy3 signal quantification, mice were rapidly anesthetized with gaz isoflurane and transcardially perfused with 4% (weight/vol.) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). Brains were post-fixed overnight in the same solution and stored at 4°C. 30 μm-thick sections were cut with a vibratome (Leica VT1000S, France), stored at −20°C in a solution containing 30% ethylene glycol, 30% glycerol and 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer. Sections were processed as follows: Day 1: free-floating sections were rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 0.25 M Tris and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.5).

Acquisitions for Exendin-4 fluorescent signal were performed with a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510) with a color digital camera and AxioVision 3.0 imaging software. Images used for quantification were all single confocal sections. Photomicrographs were obtained with the following band-pass and long-pass filter settings: Cy3 (band-pass filter: 560–615). The objectives and the pinhole setting (1 airy unit, au) remained unchanged during the acquisition of a series for all images. Quantification of fluorescent signal was performed using the ImageJ software taking as standard reference a fixed threshold of fluorescence.

Total protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Mice were injected i.p. with insulin (60 nmol/kg, Novo Nordisk) or vehicle prior to brains were dissected by decapitation. Hypothalamic and MBH region were detected and isolated under microscope and were snap frozen immediate in liquid nitrogen. Proteins were extracted with tris-based lysis buffer (25 mM Tris pH7.4, 50 mM beta-glycerophosphate, 1% Triton x100, 1.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10ug/ml leucepeptin + pepstatin A, 10 ug/ml aprotin, 100ug/ml PMSI). Homogenates were incubated on ice for 30 min and then cleared by a 10 min centrifugation at 21,000 g. 20 ug of protein extracts were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for Western blot analysis. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: 1:100 (phospho-Ak (ser473): CST #4060S), 1:500 (total-Akt: CST #9272), 1:1000 (phospho-ERK (T42/44), CST #9101), 1:5000 (beta actin: Sigma A1978).

Acute insulin/Exendin-4 injection

Metabolic output and feeding were monitored on C57Bl6j male mice (10 weeks old) using indirect calorimetry (n = 8 per groups) for a 2-days baseline acclimation consisting of a single saline injection (i.p at 2:00 pm), followed by a 4-days treatment period in which animals received an i.p injection of insulin (24 nmol/kg), Exendin-4 (120 nmol/kg) or a combination of both (Ex-4 120 nmol/kg + Insulin 24 nMol/kg). After completion of the analysis, animal received an acute injection of fluorescent labeled Ex-4 (Exendin4_VT750, 120nMol/kg, Novo Nordisk) 15 min prior to sacrifice, followed by fixation perfusion (10 mL saline with 20U/ml heparin and 10mL 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin) and dissection of the brain. Tissue were stored in 10% NBF 4°C until further processing. TanycyteΔVegfa and control mice were subjected to a 3-day saline baseline followed by consecutive, 2-days regimen of Exendin-4, 2-days of and insulin and 3-days Insulin + Exendin-4 injection.

Metabolic efficiency analysis

Mice were monitored for whole energy expenditure (EE), oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, respiratory exchange rate (RER = VCO2/VO2, where V is a volume), and locomotor activity using calorimetric cages with bedding, food and water (Labmaster, TSE Systems GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany).

Ratio of gases is determined through an indirect open circuit calorimeter (for review (Arch et al., 2006; Even and Nadkarni, 2012)). This system monitors O2 and CO2 concentration by volume at the inlet ports of a tide cage through which a known flow of air is being ventilated (0.4 L/min) and compared regularly to a reference empty cage. For optimum analysis, the flow rate is adjusted according to the animal weights to set the differential in the composition of the expired gases between 0.4 and 0.9% (Labmaster, TSE Systems GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany).

The flow is previously calibrated with O2 and CO2 mixture of known concentrations (Air Liquide, S.A. France). Oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production and energy expenditure were recorded every 15 min for each animal during the entire experiment. Whole energy expenditure was calculated using the Weir equation respiratory gas exchange measurements (3). Fatty acid oxidation was calculated from the following equation: fat ox (kcal/h) = energy expenditure X (1-RER/0,3) according to Bruss et al. (Bruss et al., 2010).

Food and water consumption were recorded as the instrument combined a set of highly sensitive feeding and drinking sensors for automated online measurement. Mice had free access to food and water ad libitum. To allow measurement of every ambulatory movement, each cage was embedded in a frame with an infrared light beam-based activity monitoring system with online measurement at 100 HZ. The sensors for gases and detection of movement operate efficiently in both light and dark phases, allowing continuous recording.

Mice were monitored for body weight and composition at the entry and the exit of the experiment. Body mass composition (lean tissue mass, fat mass, free water and total water content) was analyzed using an Echo Medical systems’ EchoMRI (Whole Body Composition Analyzers, EchoMRI, Houston, USA), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, un-anesthetized mice were weighed before they were put in a mouse holder and inserted in MR analyzer. Readings of body composition were given within 1 min.

Data analysis was performed on excel XP using extracted raw value of VO2 consumed, VCO2 production (express in ml/h), and energy expenditure (Kcal/h). Subsequently, each value was expressed either by total body weight or whole lean tissue mass extracted from the EchoMRI analysis. The EE ANCOVA analysis done for this work was provided by the NIDDK Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Centers (MMPC, www.mmpc.org) using their Energy Expenditure Analysis page (http://www.mmpc.org/shared/regression.aspx) and supported by grants DK076169 and DK115255’.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. All data were entered into Excel 5.0 or 2003 spread sheets and subsequently subjected to statistical analyses using GraphPad Prism or Statview Software. Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05. All statistical comparisons were performed with Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The statistical tests used are listed along with the statistical values in the Supplementary Tables. All the data were analyzed using either Student t-test (paired or unpaired) with equal variances or One-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA. In all cases, significance threshold was automatically set at p < 0.05. ANOVA analyses were followed by Bonferroni post hoc test for specific comparisons only when overall ANOVA revealed a significant difference (at least p < 0.05). All details related to statistical analyses are summarized in Data S1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a collaborative research grant from Novo Nordisk and the Université Paris Cité. We acknowledge funding support from the Centre National la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), The Université Paris Cité, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM). We thank Olja Kacanski for administrative support, Isabelle Le Parco, Ludovic Maingault, Angélique Dauvin, Aurélie Djemat, Florianne Michel, Magguy Boa, and Daniel Quintas for animal care; Sabria Allithi for genotyping; and Jeanette Bannebjerg Johansen for laboratory/technical support. W.E. thanks Massimiliano Mazzone for the Vegflox/lox mice. We acknowledge the technical platform Functional and Physiological Exploration platform (FPE) of the Université Paris Cité, BFA, UMR 8251, CNRS, Paris, France, and the animal core facility “Buffon” of the Université Cité/Institut Jacques Monod. D.H.M.C. and R.H. received support from the National Research Agency ANR-15-CE14-0030-01: “Nutritpathos” and ANR-17-CE37-0007-02 “METACOGNITION,” respectively. This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) Synergy grant no. 810331 to V.P. and M.S., H2020-MSCA grant no. 748134 to M.I. The EE ANCOVA analysis done for this work was provided by the NIDDK Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Centers (MMPC, www.mmpc.org) using their Energy Expenditure Analysis page (http://www.mmpc.org/shared/regression.aspx) and supported by grants DK076169 and DK115255’.

Author contributions

W.B. initiated the project, conducted most experiments, and provided guidance throughout the project. C.G.S., S. Luquet, W.F.J.H., H.S.N., A.S., J.H.-S., and T.Å.P. conducted imaging experiments, synthetized fluorescent compounds, and provided expertise on analysis. M.I. provided critical input and experiment throughout the project in the whole revision part. D.H.M.C., R.H., C. Morel, C. Martin, C. Meresse, G.G., R.G.P.D., and J.C. carried out metabolic and behavioral phenotyping. A.P., M.H., and W.M. conducted the experiments in humans. M.I., M.D., M.S., and V.P. provided expertise and animal models to explore tanycytic function. C. Martin, G.G., M.I., and V.P. provided critical insight for manuscript preparation. W.B., M.I., G.G., C. Martin, M.I., V.P., and S. Luquet designed and planned the experiments. S. Luquet designed and supervised the whole project, secured funding, and wrote the manuscript with the help of all co-authors.

Declaration of interests

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk, through which T.Å.P., A.S., S.L., W.F.J.H., and H.S.N. are current employees and shareholders, while C.G.S. and J.H.-S. are former employees and shareholders. The insulin and the peptide used for the experiments were provided by Novo Nordisk as well. This does not alter our adherence to all policies on sharing data and materials. All Intellectual Property Rights of the current study are owned by the Université Paris Cité, CNRS UMR 8251, and there has been no compromise of the objectivity or validity of the data in the article. C.G.S. and J.H.-S. are no longer affiliated with Novo Nordisk at the time of manuscript submission. Novo Nordisk markets liraglutide for the treatment of diabetes and obesity. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Published: November 22, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111698.

Contributor Information

Wineke Bakker, Email: wineke.bakker@gmail.com.

Serge Luquet, Email: serge.luquet@u-paris.fr.

Supplemental information

Figures S1–S7, Tables S1 and S2, and supplemental experimental procedures

Statistical details corresponding to Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and S1–S6

Data and code availability

-

•

Data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

Corresponding statistical details are provided in Data S1.

-

•

This study did not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this study is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Abtahi S., VanderJagt H.L., Currie P.J. The glucagon-like peptide-1 analog exendin-4 antagonizes the effect of acyl ghrelin on the respiratory exchange ratio. Neuroreport. 2016;27:992–996. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S.L., Trujillo J.M. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29:152–160. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]