Abstract

Policies to improve air quality need to be based on effective plans for reducing anthropogenic emissions. In 2020, the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic resulted in significant reductions of anthropogenic pollutant emissions, offering an unexpected opportunity to observe their consequences on ambient concentrations. Taking the national lockdown occurred in Italy between March and May 2020 as a case study, this work tries to infer if and what lessons may be learnt concerning the impact of emission reduction policies on air quality. Variations of NO2, O3, PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations were calculated from numerical model simulations obtained with business as usual and lockdown specific emissions. Both simulations were performed at national level with a horizontal resolution of 4 km, and at local level on the capital city Rome at 1 km resolution. Simulated concentrations showed a good agreement with in-situ observations, confirming the modelling systems capability to reproduce the effects of emission reductions on ambient concentration variations, which differ according to the individual air pollutant. We found a general reduction of pollutant concentrations except for ozone, that experienced an increase in Rome and in the other urban areas, and a decrease elsewhere. The obtained results suggest that acting on precursor emissions, even with sharp reductions like those experienced during the lockdown, may lead to significant, albeit complex, reduction patterns for secondary pollutant concentrations. Therefore, to be more effective, reduction measures should be carefully selected, involving more sectors than those related to mobility, such as residential and agriculture, and integrated on different scales.

Keywords: Air pollution, COVID-19, Lockdown, Air quality policies, Air quality modelling

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Air pollution represents the biggest environmental threat to human health together with climate change. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 7 million of premature deaths every year due to air pollution exposure and in September 2021 reviewed and updated its Air Quality Guidelines lowering the recommended limit values of air pollutants for public health protection (WHO, 2021).

Efforts to improve air quality have also benefits in contrasting climate change, and the adoption of policies and measures reducing greenhouse gases emissions can in turn improve air quality.

When in early 2020 the world had to face the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), different lockdown measures were put in place that lead to an unforeseen decrease in air pollutant and greenhouse gases emissions (Gkatzelis et al., 2021). From this point of view, the tragic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which led governments to act with drastic interventions to limit its spread, can be used as a test bench to assess the effectiveness of policies based on anthropogenic emission reduction. Indeed, during the COVID-19 induced lockdowns, some human activity sectors were affected rather than others, with very important emission variations in just a few weeks. By estimating those variations, simulating their effects on air quality, and checking them against monitoring data, we can quantify the expected impact on air quality of hypothetical long-term policies, acting on those sectors, with similar variations. Therefore, the first wave of the pandemic offers a unique opportunity, although as an unforeseen and side effect, to understand how air quality can be modified if measures to reduce air pollution emissions are adopted at different scales, from regional to local ones (Sokhi et al., 2021).

On the other hand, this unprecedented real-world experiment raised the interest of many researchers from different fields in studying the link between air pollution and COVID-19. As Heederik et al. (2020) pointed out, some papers were accepted for publication after a very short review period abandoning the rigorous peer review process, rushing the dissemination of several findings (Villeneuve and Goldberg, 2020) and suggesting that sometimes the observed link is a correlation rather than a causation (Riccò et al., 2020). If the evaluation of the relations between air pollution and SARS-CoV-2 is still in progress, with new researches showing more rigorous analyses of previous papers (e.g. Kogevinas et al. (2021)), many studies have demonstrated that the unprecedented national lockdowns, travel restrictions and the closing of national borders during the first wave of the pandemic in 2020 caused short-term pollutant concentration reductions.

Several analyses regarding the effect of lockdowns on air quality were conducted at different scales using various approaches such as machine learning, statistical analysis, satellite data and numerical modelling. A review can be found in Silva et al. (2022) and Gkatzelis et al. (2021) and at the following link https://amigo.aeronomie.be/covid-19-publications/peer-reviewed. At global level, Sokhi et al. (2021) evaluated air quality changes comparing 2020 with the period 2015–2019 using ground-based air quality observations over 63 cities, covering 25 countries, and observing a decrease up to 70% for nitrogen dioxide (NO2), between 30% and 40% for particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5) even if the signal resulted to be rather complex in different cities and among the same regions, while ozone (O3) showed no or small increases. In Europe, Barré et al. (2021) estimated the lockdown effects on NO2 concentrations using satellite data, surface site measurements and regional ensemble air quality modelling simulations from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), with an estimated NO2 concentration reductions of 23%, 43% and 32%, respectively; Schneider et al. (2022) quantified the effect of different lockdown measures on concentrations of NO2, O3, particulate matter with a diameter of 10 μm or less (PM10) and PM2.5 across 47 European cities using CAMS modelling data, showing a general decrease in NO2 and PM concentrations with a different behaviour for O3 whose concentrations presented limited reductions and a slight increase in April, and also estimating the number of avoided deaths attributable to single activity reductions.

Numerous studies were also conducted in specific European countries, for example Velders et al. (2021) quantified the lockdown effects on PM and gaseous pollutants in the Netherlands using a numerical model and a random forest technique, estimating a reduction range of 8–30% for NO2 and 5–20% for PM2.5; von Schneidemesser et al. (2021) estimated the effects of traffic lockdown measures on NO2 levels using both observations and models in Berlin with the median observed NO2 concentration reduction of around 40%, while in Spain Querol et al. (2021) studied the effects of COVID-19 on air quality for different pollutants in 11 cities, finding a marked decreased in NO2 concentrations, low decrease in PM levels, and different urban O3 behaviour with a slight decrease in rural areas.

In general, all the studies agreed on the overall significant reduction of NO2 concentrations, leading to a slight increase of O3 levels in urban areas, while the PM signal is rather complex among different cities and places.

In Italy, one of the countries most affected by the first wave of the pandemic, many studies to assess the impact of lockdown on air pollutant concentrations were performed: Campanelli et al. (2021) used in-situ observations, aerosol and gas column measurements and satellite data to analyse NO2 air concentrations at five urban sites distributed over the whole Italian territory; Putaud et al. (2021) analysed the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on air quality at regional and urban background sites in northern Italy; Bontempi et al. (2022) in the city of Brescia (Lombardy region, northern Italy), while Cucciniello et al. (2022) in the city of Avellino (southern Italy).

Whereas previous studies were mainly limited to regions or cities, our work represents the first study covering the entire Italian territory, where a high-resolution chemical transport model (CTM), validated with ground-based observations, was applied to integrate different scales. Moreover, the use of a CTM enabled us to evaluate the emission variations of each lockdown restriction measure and to estimate their effects in terms of air pollutant concentrations.

Our aim is to infer from the pandemic lockdowns what messages we can take home in defining air pollution control programs to provide useful information to policymakers for the definition of future abatement policies. In this respect, our approach is to relate COVID-19 induced emission reductions in some sectors with air pollutant concentrations, aiming at assessing the effectiveness of emission reduction policies in air quality regulations. To this scope, we used the case study of Italy national lockdown between February and May 2020.

Numerical simulations at different horizontal spatial resolutions were conducted to evaluate the effects on air pollution: at national level with a resolution of 4 km and in the case of the capital city Rome with a resolution of 1 km.

The model evaluation performed with pollutant concentrations, observed before and during the lockdown, provides a validation of the chemical transport model as a tool to estimate the air quality impact of emission reduction measures in air quality plans, that is not achievable through feasible real-world experiments.

Data and methods are presented in Section 2, the results are shown in Section 3 with a brief discussion, and some conclusions are drawn in Section 4.

2. Data and methods

To evaluate the changes in NO2, O3, PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations from the emission reductions caused by COVID-19 lockdown measures enforced in Italy, we used an approach based on three-dimensional atmospheric modelling.

Air quality simulations were performed from January to May 2020 using the Flexible Air quality Regional Model (FARM; Gariazzo et al., 2007; Silibello et al., 2008; Kukkonen et al., 2012) Chemical Transport Model (CTM) with different setups over two domains, at lower (4 km) and higher (1 km) horizontal resolution, covering the whole Italy and the city of Rome, respectively. Modelling domains are depicted in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Domains considered in the present study: Italian national domain with a resolution of 4 km (on the left, green border) and domains of the Lazio regional system with the inner Rome domain having a resolution of 1 km (on the right, red border, the black star indicating the city location).

2.1. Simulation over Italy

The study at national scale was carried out by means of the Atmospheric Modelling System of the MINNI project (AMS-MINNI; Mircea et al., 2014; 2016; D'Elia et al., 2021) whose main components are the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF, Version 4.1.2, Skamarock et al., 2019) meteorological model, the EMission Manager (EMMA; ARIA/ARIANET, 2013) emission processor, and the FARM CTM.

Two different air quality simulations were conducted, covering the period from January to May 2020, over the 4 km resolution grid: the first one (BASE) made use of the business-as-usual anthropogenic emission inventory, while the second one (LOCK) was set up to include the lockdown-induced emission reductions in different sectors. The same meteorological conditions, described in the following Section, were used to drive the two simulations. Two different AMS-MINNI air quality simulations, produced within CAMS over Europe and consistently referred to business-as-usual and lockdown scenarios, were used as initial conditions and to force pollutant concentrations at lateral boundaries. More details on emissions and boundary conditions can be found in Sections 2.1.2 and 2.1.3.

2.1.1. Meteorology

Hourly meteorological fields over Italy for the period of interest were reconstructed using the WRF model, considering two nested domains (2-way mode) at 12 and 4 km resolution, respectively, the former over Central Europe and the latter covering Italy. ERA5 (Hersbach et al., 2020) reanalyses fields were used as initial and boundary conditions for the coarser grid. Details on WRF setup are summarised in Table 1 .

Table 1.

WRF setup used for the simulation over Italy.

| Model version | WRF v4.1.2 (Skamarock et al., 2019) | |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Central Europe | Italy |

| Horizontal resolution | 12 km | 4 km |

| Number of grid points in x | 204 | 388 |

| Number of grid points in y | 190 | 418 |

| Number of vertical sigma-hybrid levels | 35 | 35 |

| Microphysics | WRF Single Moment 6-class scheme (Hong and Lim, 2006) | |

| Cumulus Parameterization | Kain–Fritsch Convective Parameterization (Kain, 2004) | Explicit convection |

| PBL Scheme | Mellor Yamada Jancic (MYJ; (Janjić, 1994) | |

| Surface layer | Monin-Obukhov/Janjic Eta (Janjić, 1996) | |

| Land Surface | Noah LSM (Land Surface Model; (Liu et al., 2006) | |

| Longwave Radiation | RRTMG (Iacono et al., 2008) | |

| Shortwave Radiation | RRTMG (Iacono et al., 2008) | |

2.1.2. Emissions

Many studies analysed the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on air quality using different approaches, from in situ observations to satellite data. The estimation of those impacts using an air quality modelling system requires the quantification of emission variations per source and pollutant, that is also important to provide significant information to policymakers in designing future abatement policies and measures. Quantifying an emission variation during the lockdown period is not a straightforward task which is affected by large uncertainties, due to types and timing of restrictions in different areas, or different individual responses, among countries and regions (Guevara et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2022).

In this study, we followed the approach defined in Guevara et al. (2021, 2022) and Rodríguez-Sánchez et al. (2022).

We firstly estimated a baseline emission inventory for the year 2020 (BASE), developed from the official national emission inventory elaborated by the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA; Taurino et al. (2022)) with a topdown approach on a provincial level (NUTS3 level, where NUTS stands for Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/background). The topdown emission inventory was compared and harmonized with the regional emission inventories made available by the EU Life Prepair project (https://www.lifeprepair.eu/) for the Po Valley Regions (northern Italy) and by ARPA Lazio for the Lazio Region (central Italy; https://www.arpalazio.it/ambiente/aria/inventario-regionale-delle-emissioni-in-atmosfera), producing for that regions an inventory with a bottomup approach. Concerning the dust emissions from road transport resuspension, to be coherent on the entire 4 km domain, the methodology of the EPA algorithm AP-42 (http://www.epa.gov/ttn/chief/ap42/ch13/bgdocs/b13s0201.pdf) and the emission factors from Amato et al. (2012) were used, not including the regional estimates.

The emission inventory is referred to 2017, being the most recent year with available official emission estimates both at national and regional level, and we assumed that it could represent BASE emissions for 2020. An exception was the residential sector, for which the heating degree days sum of 2017 and 2020 was used to update the emissions to the year 2020, accounting for the effect of the different meteorology.

To be used in FARM CTM, the provincial emission inventory was then spatially disaggregated to the 4 km grid, hourly modulated and speciated by EMMA.

To quantify the emission variation due to the COVID-19 restrictions put in place all over Italy, emission adjustment factors were built following a data-driven approach (Guevara et al., 2021, 2022; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2022). As in the studies already cited, we assumed that changes in emissions follow changes in the main activity data. Data from different sources were analysed and compared. For each of the following sector, classified considering the European Selected Nomenclature for Air Pollution (SNAP), we prepared a dataset of adjustment factors to be applied to BASE emission inventory in order to build the LOCK emission inventory: energy industry (SNAP 01), manufacturing industry (SNAP 03 and 04), civil sector (SNAP 02, divided in commercial/institutional and residential sub-sectors), road transport (SNAP 07, divided in light and duty vehicles), maritime transport (SNAP 0804) and aviation (SNAP 0805). A summary of the activity data considered for each sector, with temporal variation (daily, weekly, or monthly) and data source is reported in table S1 of the Supplementary Material (SM).

2.1.3. Air quality

The BASE and LOCK air quality simulations were performed running FARM on the target domain reported in Fig. 1, having a horizontal resolution of about 4 km (0.045° latitude x 0.035° longitude). FARM was forced by the meteorological fields and anthropogenic emissions produced as described in the previous Sections, interpolated on the model grid. The 0.15° × 0.1° horizontal resolution concentration fields over Europe from AMS-MINNI, one of the models participating in CAMS71 COVID19 exercise (Schneider et al., 2022), were used as boundary and initial conditions.

FARM operates off-line, downstream with respect to meteorology, taking as input the WRF hourly fields to calculate transport, diffusion, and transformations of the atmospheric pollutants. The meteorological post-processor SURFPRO (SURFace-atmosphere interface PROcessor; AriaNet srl, 2011) was used to interface the two models, using WRF simulated quantities to produce a more detailed description of boundary layer structure and to estimate micrometeorological parameters (turbulence scales like Reynolds stresses and scale temperature), horizontal and vertical diffusivities, deposition velocities for gaseous species and natural emissions (biogenic, soil dust and marine aerosols) on the simulation grid.

Table 2, Table 3 summarize the settings adopted for FARM and SURFPRO, respectively.

Table 2.

FARM setup used for the simulation over Italy.

| Version | FARM v5.1 |

|---|---|

| Domain | Italy (see Fig. 1) |

| Horizontal resolution | ∼4 km (0.045° × 0.035° lat-lon) |

| Number of grid points in x | 388 |

| Number of grid points in y | 418 |

| Number of fixed terrain-following vertical levels | 14 (from 20 m up to 6290 m) |

| Advection scheme | Blackman cubic polynomials (Yamartino, 1993) |

| Vertical levels | 16 fixed terrain following layers with a quasi-logarithmic distribution. Meteorological fields are provided on the centre of the cells. |

| Lower layer thickness | 40 m Concentrations are provided at this height. |

| Domain top | 10 km |

| Chemical mechanism | SAPRC-99 (Carter, 2000) |

| Aerosol model | AERO3 (Binkowski and Roselle, 2003) Dynamics is described by three growing and interacting lognormal modes: nucleation (Aitken), accumulation and coarse. |

| Cloud chemistry | Aqueous SO2 simplified chemistry (Seinfeld and Pandis, 1998) |

| Inorganic chemistry | ISORROPIA v1.7 (Nenes et al., 1998) |

| Organic chemistry | SORGAM (Schell et al., 2001) |

| Boundary conditions | From MINNI/CAMS COVID-19 exercise |

Table 3.

SURFPRO setup used for the simulation over Italy.

| Version | SURFPRO v3.3 |

|---|---|

| Land use | Corine Land Cover 2006 with 22 classes |

| Biogenic VOC | MEGAN 2.04 (Guenther et al., 2006) |

| NOx from soil | MEGAN 2.04 (Guenther et al., 2006) |

| Sea salt emissions | Zhang et al. (2005) |

| Windblown dust | Vautard et al. (2005) |

| Vertical diffusivity | Kz-closure approach following Lange (1989) |

| Horizontal diffusivity | combination of two methods: Smagorinsky (1963) and scale function depending on the local stability class and wind speed (sum of the two values). |

| Dry deposition | Resistance model based on (Wesely, 1989) |

| Wet deposition for both gases and aerosols species | In-cloud and sub-cloud scavenging coefficients following EMEP (Simpson et al., 2003) |

| Mixing height computation scheme | Bulk Richardson number method (with fixed Ric = 0.25) |

2.2. High resolution simulation over rome

The study over Rome shared the air quality modelling system used in the national scale analysis, including FARM CTM, EMMA and SURFPRO. Moreover, the air quality boundary conditions were extracted from the national scale simulations as the best available option to describe the long-range transport of pollutants from other areas of the country and from further European regions. The local scale simulation differed from the national scale one for what concerns meteorology and emission reconstruction, consistently performed according to what employed in ARPA Lazio operational air quality forecast system configuration over Lazio region and Rome metropolitan area (https://qa.arpalazio.net/, in Italian), also used in year-by-year air quality assessments. The meteorology was reconstructed by the Regional Atmospheric Modelling System (RAMS, Cotton et al., 2003), while emission estimates were based on Lazio Region emission inventory for the reference year 2017.

Two different air quality simulations were performed on a two-way nested modelling system covering the Lazio Region with 4 km resolution, and an inner area spanning 60 × 60 km centred over Rome city with a resolution of 1 km (Fig. 1 ). Adopting the same approach described for the national scale analysis, the first simulation (BASE) made use of business-as-usual anthropogenic emissions described by the regional emission inventory, while the second one (LOCK) included the lockdown-induced emission reductions. The two corresponding national scale AMS-MINNI air quality simulations were used to define pollutant concentrations at lateral boundaries. The simulations covered the whole year 2020 to support the ARPA Lazio institutional activities in the yearly air quality assessment, while the analysis presented here is focused on the period from 1st January to May 3, 2020 to highlight lockdown related emission reduction impact. More details on meteorology and emissions are given in the following Sections.

2.2.1. Meteorology

Meteorological fields over Lazio Region and Rome were reconstructed by the application of the RAMS model on four two-way nested domains at 32, 16, 4 and 1 km resolution, to downscale the US National Centers for Environmental Prediction GFS (Global Forecast System (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/weather-climate-models/global-forecast); global meteorological forecast over the target urban area of Rome.

Details on the RAMS setup are summarised in Table 4 .

Table 4.

RAMS setup used for the simulation down to Lazio Region and Rome.

| Model version | RAMS v6 (Cotton et al., 2003) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Central Mediterranean | Italy | Lazio Region | Rome |

| Horizontal resolution | 32 km | 16 km | 4 km | 1 km |

| Number of grid points in x | 54 | 58 | 66 | 70 |

| Number of grid points in y | 54 | 58 | 58 | 70 |

| Number of vertical sigma-hybrid levels | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Microphysics | Two-moment bulk scheme (Meyers et al., 1997; Walko et al., 1995) | |||

| Cumulus Parameterization | Modified Kuo – (Tremback, 1990) | Modified Kuo – (Tremback, 1990) | Explicit convection | Explicit convection |

| PBL Scheme | Mellor-Yamada level 2.5 scheme – (Mellor and Yamada, 1982) | |||

| Surface layer | Surface layer similarity theory (Louis, 1979) | |||

| Land Surface | Soil – vegetation – snow parameterization (LEAF-3) (Walko et al., 2000) | |||

| Longwave Radiation | Harrington (1997) long/shortwave model – two stream scheme interacts with liquid and ice hydrometeor size spectra and with dust particles | |||

| Shortwave Radiation | Harrington (1997) long/shortwave model – two stream scheme interacts with liquid and ice hydrometeor size spectra and with dust particles | |||

2.2.2. Emissions

The emission input for 4 and 1 km resolution air quality simulations was prepared using the same emission processor explained in Section 2.1.2, starting from the data of the ARPA Lazio inventory for the reference year 2017 (https://www.arpalazio.it/ambiente/aria/inventario-regionale-delle-emissioni-in-atmosfera), available at municipality level. Dust emissions from road transport resuspension were estimated using the EPA algorithm AP-42 (https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-10/documents/13.2.1_paved_roads.pdf).

As done for the national scale simulations, the inventory data were used for the BASE case, and the LOCK case was generated by applying daily based emission reductions per sector, also using the same adjustment factors of the national scale.

3. Results and discussion

In the following paragraphs, we firstly discuss the effect of lockdown measures on emissions (Section 3.1) and then on air quality (Section 3.2) both on national and Rome domain.

3.1. Emissions

On a national level, the comparison between LOCK and BASE emission scenarios (reported in Section S2 of the SM, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6) shows a significant variation in nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur oxides (SOx) and non-methane volatile organic compound (NMVOC) emissions from the second part of March to the end of April with a daily reduction that reaches 30%, while in May, when the restrictions were less stringent, a slight emission recovery is foreseen. Minor variations are estimated for PM2.5 (similar considerations can be extended also to PM10) and carbon monoxide (CO), while no significant variations are estimated for ammonia (NH3), as the agricultural sector, the main contributor for this pollutant, was not interested by the restrictions.

Fig. 2.

Top: contribution of each sector (affected by the restrictions) to total BASE emissions over the entire period (Feb–May 2020). Middle: total emission variations (LOCK-BASE)/BASE [%] due to lockdown measures. Bottom: emission variations over the entire period for each sector.

Fig. 3.

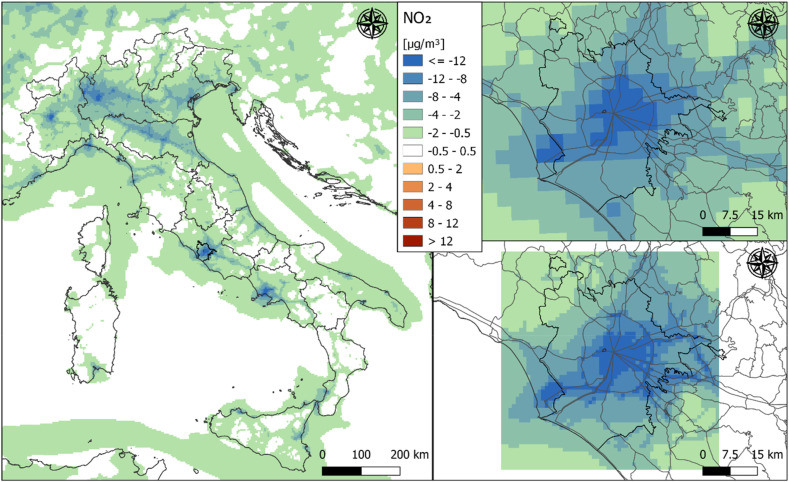

NO2 concentration differences (in μg/m3) between LOCK and BASE in April 2020: Italian domain at 4 km resolution (left) and zoomed over Rome (top, right); 1 km resolution simulation over Rome (bottom, right). Gray lines represent Rome main road network.

Fig. 4.

As in Fig. 3 but referred to O3 concentration differences.

Fig. 5.

As in Fig. 3 but referred to PM10 concentration differences.

Fig. 6.

As in Fig. 3 but referred to PM2.5 concentration differences.

Overall, in the entire period, we estimated an average emission reduction of 15% for SOx, 11% for NOx, 10% for NMVOC, 4% for CO, 2% for PM2.5, and no reduction for NH3 (Fig. 2, middle). For each pollutant, Fig. 2 shows the contribution to the total BASE emissions coming from all the sectors affected by the restrictions (top histogram) and the estimated emission variation (LOCK-BASE)/BASE during the first wave of the pandemic (middle). The variation occurred in the entire period in each sector for each pollutant are presented as well (bottom).

For NOx emission, the sectors affected by the restrictions contributed to nearly 60% of total BASE emissions (Fig. 2, top), with the road transport sector being the most contributing one, followed by industrial, maritime and energy sectors, whose reductions respect to their sectorial BASE value are −22%, −25%, −20% and −16%, respectively (bottom panel). Indeed, industrial, maritime and energy sectors show high sectoral variation, but their contribution to the total emission variation is limited to a few percentage points (middle panel). The emission variations for PM2.5, CO and NH3 are low (middle), as their respective dominant sectors (top panel) were either not affected (agriculture for NH3) or increased their activity rates (residential heating for PM2.5 and CO, bottom panel).

The sectors involved by the COVID-19 measures contributed to 53% of total NMVOC emissions (top panel), with the industrial sector reduced by 24% (bottom panel) and driving the overall NMVOC reduction (middle panel).

3.2. Air quality

An in-depth evaluation of the LOCK simulation was firstly carried out. Different statistical indices were calculated as suggested by literature on model validation (Chang and Hanna, 2004), to quantify the agreement between modelled and observed values. The statistical metrics were calculated for the background monitoring stations satisfying the criteria of 75% of valid data per month for all the period (Jan–May 2020). Valid stations for the three zones urban (UB), suburban (SB) and rural (RB) and for each pollutant were grouped by 9 climatic zones and depicted in Figure SF3.1 of the SM. The results for mean bias (MB), root mean square error (RMSE) and the correlation coefficient (corr) are reported in Section S3 of the SM Figures SF3.2-9, along with their formulations. The analysis shows that, regardless of the station zone, for both NO2 and O3 the highest correlation values are found in the Po Valley (Pianura Padana and Alto Adriatico, the latter being the coastal area of the Po Valley), where also the higher PM10 and PM2.5 values are observed. This result is noteworthy as Po Valley, representing a hotspot for air pollution in Italy, was particularly affected by lockdown measures, and good model skills in correlation values indicate the robustness of the temporal modulation adopted in the emissions and in the applied reductions. Indeed, the comparison between observed and simulated time series of daily average concentrations (Section 4 in the SM) underlines as the modelling systems, with few exceptions occurring in less polluted areas, are in good agreement with the observed time evolution over Italy (4 km resolution, Figures SF4.1.1-12) as well as in Rome (4 and 1 km resolutions, Figures SF4.2.2-9). This behaviour, during the lockdown period when substantial and rapid emission variations occurred, confirms that the modelling systems as a whole can be valuable tools in analysing the effects of reduction measures implied by air quality policies, assessing cross-sectoral synergies and trade-offs. This assessment is a peculiar result enabled by the sharp emissions reduction occurred during the lockdown that cannot be obtained from model evaluation using observations gathered by feasible real-world experiments.

Once validated the model results, simulated concentrations of NO2, O3, PM10 and PM2.5 are presented here focussing only on the month of April 2020, when the most stringent restrictions were fully in place all over Italy. This choice allows us to avoid possible misinterpretation in our results by considering a larger period, only partially interested by restrictions, and when the highest air pollutant concentration variations were observed. As a reference for the whole simulated months, the reader can refer to the SM (Section S4).

In the following paragraphs, for each pollutant we present the results in terms of average concentration difference between LOCK and BASE simulated concentrations over Italy and over Rome at 4 and 1 km resolution, respectively.

3.2.1. NO2

In Section S4.1.1 (SM), a detailed comparison between NO2 observed and simulated (LOCK) concentrations is presented at national level, as the daily time series computed as the median of all the background stations data, grouped by climatic zone (Figure SF4.1.1). The modelling system gives reasonably good results in most areas, except mainly in the mountains (Arco Alpino and Appennino, i.e., Alps and Apennines) where the 4 km horizontal resolution is not enough to resolve the effects induced by the complex orography, as well as in some southern areas of the country where the number of available stations is too limited to provide an extensive description of background concentrations. As mentioned before, it is worth noting that the model performs reasonably well in the Po Valley. A similar behaviour is observed over the Rome domain (see S4.2.1 in SM for reference), where both simulations tend to well reproduce the time evolution (SF4.2.2), but some differences can be observed: if we focus on April (SF4.2.3), high resolution simulation tends to produce lower NO2 concentrations than the 4 km resolution one at the selected sites, in some cases underestimating the observed values.

Fig. 3 shows the average NO2 concentration difference (LOCK-BASE) in April 2020 for the 4 km resolution simulations at national level (left) and zoomed over Rome area (top, right), as well as the same difference related to 1 km resolution domain (bottom, right). At Italian level, a reduction of NO2 concentrations is observed, with the highest differences exceeding 12 μg/m3 in northern Italy (mainly the Po Valley) and in general within the major urban areas and along the main road axes; far from these zones, the concentration variations are very small or negligible. A similar pattern is shown both in the 4 and 1 km resolution over the Rome domain (top right and bottom right in Fig. 3, respectively): in this case, increasing the resolution does not dramatically change the absolute magnitude of the variations, but highlights spatial details reflecting the most urbanised areas of the city and its main road network.

3.2.2. O3

In Section S4.1.2 (SM), a detailed comparison between observed and simulated (LOCK) ozone concentrations is presented at national level for daily maximum 8 h average (MDA8) time series, as the median value of all the background stations grouped by climatic zone (Figure SF4.1.4). Excluding the Alps and the Apennines where, as noted before, the model resolution is not adequate for resolving complex orography, a good agreement with measurements is generically shown, especially where high pollution levels are observed (e.g., Po Valley). Moreover, from figure SF4.1.4 (in SM) it is worth noting that the ozone concentration increase observed in April is well reproduced by the model. Similar behaviour is noted in Rome (Section S4.2.2 in SM), where the two simulations give similar results, well reproducing the ozone trend (SF4.2.4–5). The average ozone air concentration difference for April 2020 is depicted in Fig. 4. At the national scale (left panel), positive values in the map indicate that lockdown measures led to an increase of ozone concentrations in main urban areas and close to the main roads, while a reduction is shown in rural areas. The same behaviour is also evident in the zoom over Rome. As in the case of NO2, also in the case of ozone the 1 km resolution simulation (bottom, right in the Figure) highlights more details of the urban area with respect to the 4 km resolution one (top, right). In both cases, maximum increments reach values of 10–12 μg/m3. These values are compatible with the estimate obtained comparing 2020 observations with 2015–2019 monthly mean concentrations (as e.g. Sokhi et al., 2021) at six urban background stations, that provided values ranging from +4 to +16 μg/m3.

The observed increment of ozone concentrations in urban areas at both resolutions, combined to the corresponding NO2 decrease, reflects the VOC-limited regime occurring in European urban areas, as showed for example by Beekmann and Vautard (2010). The decrease of NOx associated to an increase of ozone was also pointed out in other works investigating air pollution related to COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. Brancher, 2021; Kroll et al., 2020). As also highlighted in Grange et al. (2021), the NOx-limited or VOC-limited regime is a crucial aspect to be considered in planning effective strategies for ozone pollution control. In this regard, numerical modelling is the only tool capable of providing a comprehensive picture at national scale to support policymakers. Our modelling analysis confirms that the increase of ozone concentration observed during the lockdown in many urban locations (see e.g. Gkatzelis et al., 2021; Sokhi et al., 2022) is limited to the cities, major roads and large conurbation areas, while rural background areas show different behaviours, with prevailing ozone concentration decrease, in agreement with the observational analyses provided by Cristofanelli et al. (2021) and Steinbrecht et al. (2021) and with model simulation results obtained for central to southern Europe by Matthias et al. (2021).

3.2.3. PM

In SM, a detailed comparison between observed and simulated PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations is presented over Italian (SM Sections S4.1.3, S4.1.4) and Rome (S4.2.3, S4.2.4) domains for daily time series, at all the background stations. Generally, the modelled concentrations show a good agreement with measurements at both resolutions, concerning the temporal variation and timing of the peaks. In general, over Rome the 4 km simulation produces lower concentrations than the high resolution one, especially during winter months (SF4.2.6, SF4.2.8).

It is worth noting that an outlier is present in the observations at the end of March, not captured by the model neither at national level nor over Rome (Figures SF4.1.7 and SF4.2.6). This event was caused by long-range dust transport from the Caspian Sea area (Campanelli et al., 2021), a contribution that was not included at the model domain boundary as not described through boundary conditions, while the concentration peak observed in mid-May in central to southern Italian regions, and contributed by Sahara dust advection (see e.g. https://dust.aemet.es/) is correctly reproduced by the model (Figures SF4.1.7).

In the city of Rome, larger differences occur in the first part of April, when the model underestimates observed PM values. In this case, the difference can be explained by intense fires in the Balkan region. This is confirmed by back-trajectories calculated by means of M-TrraCE (Vitali et al., 2017) from 4th to 14th of April using the hourly 4 km meteorological fields produced by WRF. As an example, Figure SF4.2.10 in SM shows the 8th of April as the most representative day of the whole event. Moreover, the descent of the airmass from the Balkans, showed in the Figure, is consistent with the synoptic pattern in the area with the presence of a high-pressure system favouring subsidence conditions, as highlighted by Campanelli et al. (2021).

Concerning PM10 fields, the difference of average simulations for April 2020 highlights a general reduction at national level (Fig. 5, left panel), with maximum values in the Po Valley, varying between 4 and 6 μg/m3. In other parts of the country, the difference is much less pronounced, except in few major urban areas like Rome (top, right panel) where an average reduction of 2–4 μg/m3 is reached. In the 1 km simulations (bottom, right panel), the area within the reduction range 2–4 μg/m3 is wider, and in the city centre and surrounding main roads the concentration reduction exceeds 6 μg/m3.

Looking at the difference of average simulated PM2.5 fields for April 2020 in Fig. 6, it is worth noting that the level of concentration reductions is close to that found for PM10, suggesting the predominance of the fine component over the coarse one in the modelled concentrations, as also confirmed by the comparison with observations (see SM Section S4).

3.3. Discussion

The results presented in this Section highlight the connection between emission reductions in some sectors and the air quality in urban and rural areas. By using a numerical modelling system, we showed that the effect of emission reductions on air pollutant concentrations may change dramatically when looking at different pollutants and/or at urban or rural areas. In the case of COVID-19 induced lockdown, the road transport sector experienced the highest variation, leading the 11% total NOx emission reduction. The effects of such reductions were largely visible on the closely interrelated NO2 and O3 ambient concentrations showing opposite behaviour in urban areas, due to the occurring VOC-limited chemical regime, a crucial aspect to be considered when elaborating emission control policies. Conversely, for other pollutants, such as PM, changes in modelled concentrations were less pronounced, confirming the prominent role of the emissions from the heating sector, only slightly affected by changes during the lockdown, and from the agricultural sector not affected by the restrictions. The impact of long-range transport of desert dust and wildfires was also identified during short term episodes occurred during the studied period. It is worthwhile considering that long-range transport and secondary pollutant formation cannot be prevented or controlled by local policies but require measures coordinated over larger scales.

Investigating the model response to emission scenarios at different resolutions, 4 km over Italy and 1 km over Rome, revealed a substantial coherence in the sign of the concentration variations, their spatial patterns, and their magnitude, even though at higher resolution more spatial details were obtained. Comparison with observed time series over Rome showed that the model performs well in terms of temporal evolution and timing of the peaks at both resolutions, while at some sites, on specific periods/days, the two simulations can differ. This different behaviour could be explained by the use of two different meteorological drivers, as illustrated by Adani et al. (2020).

It is worth noting that the model best performances compared to observations were obtained in the Po Valley, a hotspot for atmospheric pollution in Italy, where the lockdown effects on air quality were larger and where we used a bottom-up emission inventory (see Section 2.1.2).

We highlight the crucial role played by state-of-the-art air quality modelling systems that allow to study and quantify the impact of emissions on air concentration variations. This feature is of the utmost importance in supporting policymakers when designing future emission abatement policies over large geographical areas and at different scales, from national down to city level. Such results, even if affected by uncertainties, can only be reached operating these comprehensive tools that integrate atmospheric dynamics, thermodynamics, and chemistry.

4. Conclusions

Many papers have been written to investigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on air quality, but a study covering the whole of Italy, one of the most affected areas during the first wave of the pandemic, was missing. In our work, we presented two different numerical simulations, related to the business as usual and the lockdown-specific emissions, with a horizontal spatial resolution of 4 km over Italy and of 1 km over a smaller domain around Rome.

The measures adopted by the different governments to contrast the SARS-CoV-2 spread represent an unprecedented and unique experiment to better understand the effects on air quality of substantial emission reductions, the peculiarities of the different pollutants, the key factors in the definition of air pollution mitigation policies.

The first question we tried to answer was whether air quality modelling systems could well reproduce the effects of large and rapid emission variations occurred in a relatively short period (two months in our analysis). Our results showed a good agreement with observations both in terms of statistical scores and time series behaviour, indicating that models can be a valuable tool in supporting the analysis and the screening of air quality policies.

We also investigated the effects of the different lockdown measures on the variation of air pollution levels and how these measures affect pollutants whose formation derives from complex physical and chemical transformations, such as PM and O3. To this aim, we elaborated and compared two different simulations, the BASE and LOCK case, sharing the same input data, but emissions and boundary conditions. The highest emission reductions occurred in the mobility sector, where road transport is the main contributor to NOx emissions. This caused an estimated reduction of 11% of total NOx emissions, that in the month of April 2020 led to a maximum reduction of 12 μg/m3 in NO2 concentrations, especially in urban areas and along the main roads. The NO2 reduction in urban areas led to an increase in O3 concentrations due to the titration process, underlining that, when defining O3 reduction measures, the prevalent chemical regime should be carefully considered. The industrial sector mostly affected SOx and NMVOC emissions but with moderate absolute variations, while the much less pronounced PM concentration reduction was linked to the increase in the emissions from the residential sector, especially during the month of March and in the first half of April, and to the lack of NH3 emission variations, mostly caused by the agricultural sector not affected by the restrictions.

This study also confirms the direct link between NO2 concentration variations and the reduction in the emission precursors (NOx), while the same is not true for PM, being its concentrations linked to a broader set of precursors (like ammonia from the agricultural sector).

The results from the higher resolution simulations over Rome, broadly showing the same patterns of the coarser simulations but better detailing their shape over and around the urban area, evidenced as synergies at different scales are required also in the policy definition.

This study demonstrated that even considerable actions in few sectors, like the transport or industrial ones, may have distinct effectiveness in abating concentrations of different air pollutants. Moreover, measures limited in time jeopardize all the efforts: Bartoňová et al. (2022), for example, demonstrates that, when averaged over the year 2020, the effects on air quality of the pandemic measures, that were gradually lifted after the first wave, will be substantially smaller than those of April 2020. The experimented abatement of traffic related emissions can be considered representative of local measures, like e.g., the urban traffic electrification, that can be expected to strongly reduce NO2 concentrations (Piersanti et al., 2021), but slightly impact pollutants influenced by long-range transport and secondary formation, which require large scale international emission reduction and prevention policies.

An integrated approach should be adopted by policymakers in defining reduction measures where policies in different fields, such as energy, climate and air quality, and different aspects, from economic to societal, must be considered in a holistic way.

Author contribution statement

Massimo D’Isidoro: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Data Curation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Visualization; Ilaria D’Elia: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Data Curation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Visualization; Lina Vitali: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Data Curation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Visualization; Gino Briganti: Software; Validation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Data Curation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Visualization; Andrea Cappelletti: Software; Data Curation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Antonio Piersanti: Conceptualization; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Sandro Finardi: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Giuseppe Calori: Software; Validation; Investigation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Nicola Pepe: Software; Validation; Investigation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Alessandro Di Giosa: Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Andrea Bolignano: Software; Validation; Investigation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Gabriele Zanini: Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Funding Acquisition

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express out thanks to the ENEA colleagues Dr. Mario Adani for providing the boundary conditions for the national air quality simulations, and Dr. Luisella Ciancarella, Dr. Giandomenico Pace and Alcide Di Sarra for sharing with us their useful ideas and comments.

We acknowledge the PULVIRUS Project that funded this activity (http://www.pulvirus.it/) and the colleagues from the National and Regional Environmental Agencies involved in the Project.

The computing resources and the related technical support used for the national simulations were provided by the CRESCO/ENEAGRID High Performance Computing infrastructure and its staff (Iannone et al., 2019). The infrastructure is funded by ENEA, the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development and by Italian and European research programmes (http://www.cresco.enea.it/english).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Turkish National Committee for Air Pollution Research and Control.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2022.101620.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adani M., Piersanti A., Ciancarella L., D'Isidoro M., Villani M.G., Vitali L. Preliminary tests on the sensitivity of the FORAIR_IT air quality forecasting system to different meteorological drivers. Atmosphere. 2020;11 doi: 10.3390/atmos11060574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato F., Karanasiou A., Moreno T., Alastuey A., Orza J.A.G., Lumbreras J., Borge R., Boldo E., Linares C., Querol X. Emission factors from road dust resuspension in a Mediterranean freeway. Atmos. Environ. 2012;61:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.07.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ARIA/ARIANET Emission Manager - processing system for model-ready emission input - user's guide. Milano. 2013;19 R2013. No. R2013.19) [Google Scholar]

- AriaNet srl . 2011. SURFPRO3 User's Guide (SURFace-Atmosphere Interface PROcessor. Version 3) [Google Scholar]

- Barré J., Petetin H., Colette A., Guevara M., Peuch V.-H., Rouil L., Engelen R., Inness A., Flemming J., Pérez García-Pando C., Bowdalo D., Meleux F., Geels C., Christensen J.H., Gauss M., Benedictow A., Tsyro S., Friese E., Struzewska J., Kaminski J.W., Douros J., Timmermans R., Robertson L., Adani M., Jorba O., Joly M., Kouznetsov R. Estimating lockdown-induced European NO2 changes using satellite and surface observations and air quality models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:7373–7394. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-7373-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoňová A., Colette A., Zhang H., Fons J., Liu H.-Y., Brzezina J., Chantreux A., Couvidat F., Guerreiro C., Guevara M., Kuenen J., Solberg S., Super I., Szanto C., Tarasson L., Thornton A., Ortiz A.G. ETC/ATNI Report; Kjeller: 2022. The Covid-19 Pandemic and Environmental Stressors in Europe: Synergies and Interplays. 2021/16. [Google Scholar]

- Binkowski F.S., Roselle S.J. Models-3 community multiscale air quality (CMAQ) model aerosol component 1. Model description. J. Geophys. Res. 2003;108 doi: 10.1029/2001jd001409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E., Carnevale C., Cornelio A., Volta M., Zanoletti A. Analysis of the lockdown effects due to the COVID-19 on air pollution in Brescia (Lombardy) Environ. Res. 2022;212 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancher M. Increased ozone pollution alongside reduced nitrogen dioxide concentrations during Vienna's first COVID-19 lockdown: significance for air quality management. Environ. Pollut. 2021;284 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanelli M., Iannarelli A.M., Mevi G., Casadio S., Diémoz H., Finardi S., Dinoi A., Castelli E., di Sarra A., Di Bernardino A., Casasanta G., Bassani C., Siani A.M., Cacciani M., Barnaba F., Di Liberto L., Argentini S. A wide-ranging investigation of the COVID-19 lockdown effects on the atmospheric composition in various Italian urban sites (AER – LOCUS) Urban Clim. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter W.P.L. Documentation of the SAPRC-99 chemical mechanism for VOC reactivity assessment. Final Report to California Air Resources Board, Contract. 2000;92–329 Contract 95–308. [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.C., Hanna S.R. Air quality model performance evaluation. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2004;87:167–196. doi: 10.1007/s00703-003-0070-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton W.R., Pielke R.A., Sr., Walko R.L., Liston G.E., Tremback C.J., Jiang H., McAnelly R.L., Harrington J.Y., Nicholls M.E., Carrio G.G., McFadden J.P. RAMS 2001: current status and future directions. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2003;82:5–29. doi: 10.1007/s00703-001-0584-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofanelli P., Arduni J., Serva F., Calzolari F., Bonasoni P., Busetto M., Maione M., Sprenger M., Trisolino P., Putero D. Negative ozone anomalies at a high mountain site in northern Italy during 2020: a possible role of COVID-19 lockdowns? Environ. Res. Lett. 2021;16 doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac0b6a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciniello R., Raia L., Vasca E. Air quality evaluation during COVID-19 in Southern Italy: the case study of Avellino city. Environ. Res. 2022;203 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Elia I., Briganti G., Vitali L., Piersanti A., Righini G., D'Isidoro M., Cappelletti A., Mircea M., Adani M., Zanini G., Ciancarella L. Measured and modelled air quality trends in Italy over the period 2003-2010. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:10825–10849. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-10825-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gariazzo C., Silibello C., Finardi S., Radice P., Piersanti A., Calori G., Cecinato A., Perrino C., Nussio F., Cagnoli M., Pelliccioni A., Gobbi G.P., Di Filippo P. A gas/aerosol air pollutants study over the urban area of Rome using a comprehensive chemical transport model. Atmos. Environ. 2007;41:7286–7303. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.05.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gkatzelis G.I., Gilman J.B., Brown S.S., Eskes H., Gomes A.R., Lange A.C., McDonald B.C., Peischl J., Petzold A., Thompson C.R., Kiendler-Scharr A. The global impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns on urban air pollution: a critical review and recommendations. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 2021;9 doi: 10.1525/elementa.2021.00176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grange S.K., Lee J.D., Drysdale W.S., Lewis A.C., Hueglin C., Emmenegger L., Carslaw D.C. COVID-19 lockdowns highlight a risk of increasing ozone pollution in European urban areas. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:4169–4185. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-4169-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther A., Karl T., Harley P., Wiedinmyer C., Palmer P.I., Geron C. Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (model of emissions of gases and aerosols from nature) Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006;6:3181–3210. doi: 10.5194/acp-6-3181-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara M., Jorba O., Soret A., Petetin H., Bowdalo D., Serradell K., Tena C., Denier van der Gon H., Kuenen J., Peuch V.-H., Pérez García-Pando C. Time-resolved emission reductions for atmospheric chemistry modelling in Europe during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:773–797. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-773-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara M., Petetin H., Jorba O., Denier van der Gon H., Kuenen J., Super I., Jalkanen J.-P., Majamäki E., Johansson L., Peuch V.-H., Pérez García-Pando C. European primary emissions of criteria pollutants and greenhouse gases in 2020 modulated by the COVID-19 pandemic disruptions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2022;14:2521–2552. doi: 10.5194/essd-14-2521-2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington J.Y. Colorado State University; 1997. The Effects of Radiative and Microphysical Processes on Simulated Warm and Transition Season Arctic Stratus. [Google Scholar]

- Heederik D.J.J., Smit L.A.M., Vermeulen R.C.H. Go slow to go fast: a plea for sustained scientific rigour in air pollution research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01361-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersbach H., Bell B., Berrisford P., Hirahara S., Horányi A., Muñoz-Sabater J., Nicolas J., Peubey C., Radu R., Schepers D., Simmons A., Soci C., Abdalla S., Abellan X., Balsamo G., Bechtold P., Biavati G., Bidlot J., Bonavita M., De Chiara G., Dahlgren P., Dee D., Diamantakis M., Dragani R., Flemming J., Forbes R., Fuentes M., Geer A., Haimberger L., Healy S., Hogan R.J., Hólm E., Janisková M., Keeley S., Laloyaux P., Lopez P., Lupu C., Radnoti G., de Rosnay P., Rozum I., Vamborg F., Villaume S., Thépaut J.-N. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020;146:1999–2049. doi: 10.1002/qj.3803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.Y., Lim J.-O.J. The WRF single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6) J. Kor. Meteorol. Soc. 2006;42:129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Iacono M.J., Delamere J.S., Mlawer E.J., Shephard M.W., Clough S.A., Collins W.D. Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases: calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008;113 doi: 10.1029/2008JD009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iannone F., Ambrosino F., Bracco G., De Rosa M., Funel A., Guarnieri G., Migliori S., Palombi F., Ponti G., Santomauro G., Procacci P. 2019 International Conference on High Performance Computing Simulation (HPCS). Presented at the 2019 International Conference on High Performance Computing Simulation. HPCS); 2019. CRESCO ENEA HPC clusters: a working example of a multifabric GPFS Spectrum Scale layout; pp. 1051–1052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janjić Z.I. Amer. Meteor. Soc.; Norfolk, VA: 1996. The Surface Layer in the NCEP Eta Model. Presented at the Eleventh Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction; pp. 354–355. [Google Scholar]

- Janjić Z.I. The step-mountain eta coordinate model: further developments of the convection, viscous sublayer, and turbulence closure schemes. Mon. Weather Rev. 1994;122:927–945. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1994)122<0927:TSMECM>2.0.CO. 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kain J.S. The kain–fritsch convective parameterization: an update. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2004;43:170–181. doi: 10.1175/1520-0450(2004)043<0170:TKCPAU>2.0.CO. 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogevinas M., Castaño-Vinyals G., Karachaliou M., Espinosa A., de C.R., Garcia-Aymerich J., Carreras A., Cort és B., Pleguezuelos V., Jimenez A., Vidal M., O'Callaghan-Gordo C., Cirach M., Santano R., Barrios D., Puyol L., Rubio R., Izquierdo L., Nieuwenhuijsen M., Dadvand P., Aguilar R., Moncunill G., Dobaño C., Tonne C. Ambient air pollution in relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection, antibody response, and COVID-19 disease: a cohort study in catalonia, Spain (COVICAT study) Environ. Health Perspect. 2021;129 doi: 10.1289/EHP9726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll J.H., Heald C.L., Cappa C.D., Farmer D.K., Fry J.L., Murphy J.G., Steiner A.L. The complex chemical effects of COVID-19 shutdowns on air quality. Nat. Chem. 2020;12:777–779. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0535-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen J., Olsson T., Schultz D.M., Baklanov A., Klein T., Miranda A.I., Monteiro A., Hirtl M., Tarvainen V., Boy M., Peuch V.-H., Poupkou A., Kioutsioukis I., Finardi S., Sofiev M., Sokhi R., Lehtinen K.E.J., Karatzas K., San José R., Astitha M., Kallos G., Schaap M., Reimer E., Jakobs H., Eben K. A review of operational, regional-scale, chemical weather forecasting models in Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012;12:1–87. doi: 10.5194/acp-12-1-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lange R. Transferability of a three-dimensional air quality model between two different sites in complex terrain. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1989;28:665–679. doi: 10.1175/1520-0450(1989)028<0665:TOATDA>2.0.CO. 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Chen F., Warner T., Basara J. Verification of a mesoscale data-assimilation and forecasting system for the Oklahoma city area during the joint urban 2003 field project. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2006;45:912–929. doi: 10.1175/JAM2383.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Louis J.-F. A parametric model of vertical eddy fluxes in the atmosphere. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1979;17:187–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00117978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthias V., Quante M., Arndt J.A., Badeke R., Fink L., Petrik R., Feldner J., Schwarzkopf D., Link E.-M., Ramacher M.O.P., Wedemann R. The role of emission reductions and the meteorological situation for air quality improvements during the COVID-19 lockdown period in central Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:13931–13971. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-13931-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor G.L., Yamada T. Development of a turbulence closure model for geophysical fluid problems. Rev. Geophys. 1982;20:851–875. doi: 10.1029/RG020i004p00851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers M.P., Walko R.L., Harrington J.Y., Cotton W.R. New RAMS cloud microphysics parameterization. Part II: the two-moment scheme. Atmos. Res. 1997;45:3–39. doi: 10.1016/S0169-8095(97)00018-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mircea M., Ciancarella L., Briganti G., Calori G., Cappelletti A., Cionni I., Costa M., Cremona G., D'Isidoro M., Finardi S., Pace G., Piersanti A., Righini G., Silibello C., Vitali L., Zanini G. Assessment of the AMS-MINNI system capabilities to simulate air quality over Italy for the calendar year 2005. Atmos. Environ. 2014;84:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mircea M., Grigoras G., D'Isidoro M., Righini G., Adani M., Briganti G., Ciancarella L., Cappelletti A., Calori G., Cionni I., Cremona G., Finardi S., Larsen B.R., Pace G., Perrino C., Piersanti A., Silibello C., Vitali L., Zanini G. Impact of grid resolution on aerosol predictions: a case study over Italy. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2016;16:1253–1267. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2015.02.0058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nenes A., Pandis S.N., Pilinis C. ISORROPIA: a new thermodynamic equilibrium model for multiphase multicomponent inorganic aerosols. Aquat. Geochem. 1998;4:123–152. doi: 10.1023/A:1009604003981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piersanti A., D'Elia I., Gualtieri M., Briganti G., Cappelletti A., Zanini G., Ciancarella L. The Italian national air pollution control programme: air quality, health impact and cost assessment. Atmosphere. 2021;12:196. doi: 10.3390/atmos12020196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putaud J.-P., Pozzoli L., Pisoni E., Martins Dos Santos S., Lagler F., Lanzani G., Dal Santo U., Colette A. Impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on air pollution at regional and urban background sites in northern Italy. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:7597–7609. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-7597-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Querol X., Massagué J., Alastuey A., Moreno T., Gangoiti G., Mantilla E., Duéguez J.J., Escudero M., Monfort E., Pérez García-Pando C., Petetin H., Jorba O., Vázquez V., de la Rosa J., Campos A., Muñóz M., Monge S., Hervás M., Javato R., Cornide M.J. Lessons from the COVID-19 air pollution decrease in Spain: now what? Sci. Total Environ. 2021;779 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccò M., Ranzieri S., Balzarini F., Bragazzi N.L., Corradi M. SARS-CoV-2 infection and air pollutants: correlation or causation? Sci. Total Environ. 2020;734 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez A., Vivanco M.G., Theobald M.R., Martín F. Estimating the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on pollutant emissions in Europe. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2022.101388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schell B., Ackermann I.J., Hass H., Binkowski F.S., Ebel A. Modeling the formation of secondary organic aerosol within a comprehensive air quality model system. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001;106:28275–28293. doi: 10.1029/2001JD000384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R., Masselot P., Vicedo-Cabrera A.M., Sera F., Blangiardo M., Forlani C., Douros J., Jorba O., Adani M., Kouznetsov R., Couvidat F., Arteta J., Raux B., Guevara M., Colette A., Barré J., Peuch V.-H., Gasparrini A. Differential impact of government lockdown policies on reducing air pollution levels and related mortality in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:726. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04277-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seinfeld J.H., Pandis S.N. John Wiley and Sons; 1998. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. [Google Scholar]

- Silibello C., Calori G., Brusasca G., Giudici A., Angelino E., Fossati G., Peroni E., Buganza E. Modelling of PM10 concentrations over Milano urban area using two aerosol modules. Environmental Modelling & Software, New Approaches to Urban Air Quality Modelling. 2008;23:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2007.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A.C.T., Branco P.T.B.S., Sousa S.I.V. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on air quality: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19:1950. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19041950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson D., Fagerli H., Jonson J.E., Tsyro S., Wind P., Tuovinen J.-P. 2003. Transboundary Acidification, Eutrophication and Ground Level Ozone in Europe PART I Unified EMEP Model Description (EMEP Status Report 2003) [Google Scholar]

- Skamarock W.C., Klemp J.B., Dudhia J., Gill D.O., Liu Z., Berner J., Wang W., Powers J.J., Duda M.G., Barker D., Huang X.-Y. NCAR/TN-556+STR; 2019. A DESCRIPTION OF THE ADVANCED RESEARCH WRF MODEL VERSION 4.1 (No. [Google Scholar]

- Smagorinsky J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations: I. The basic experiment. Mon. Weather Rev. 1963;91:99–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sokhi R.S., Moussiopoulos N., Baklanov A., Bartzis J., Coll I., Finardi S., Friedrich R., Geels C., Grönholm T., Halenka T., Ketzel M., Maragkidou A., Matthias V., Moldanova J., Ntziachristos L., Schäfer K., Suppan P., Tsegas G., Carmichael G., Franco V., Hanna S., Jalkanen J.-P., Velders G.J.M., Kukkonen J. Advances in air quality research – current and emerging challenges. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022;22:4615–4703. doi: 10.5194/acp-22-4615-2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sokhi R.S., Singh V., Querol X., Finardi S., Targino A.C., Andrade M. de F., Pavlovic R., Garland R.M., Massagué J., Kong S., Baklanov A., Ren L., Tarasova O., Carmichael G., Peuch V.-H., Anand V., Arbilla G., Badali K., Beig G., Belalcazar L.C., Bolignano A., Brimblecombe P., Camacho P., Casallas A., Charland J.-P., Choi J., Chourdakis E., Coll I., Collins M., Cyrys J., da Silva C.M., Di Giosa A.D., Di Leo A., Ferro C., Gavidia-Calderon M., Gayen A., Ginzburg A., Godefroy F., Gonzalez Y.A., Guevara-Luna M., Haque SkM., Havenga H., Herod D., Hõrrak U., Hussein T., Ibarra S., Jaimes M., Kaasik M., Khaiwal R., Kim J., Kousa A., Kukkonen J., Kulmala M., Kuula J., La Violette N., Lanzani G., Liu X., MacDougall S., Manseau P.M., Marchegiani G., McDonald B., Mishra S.V., Molina L.T., Mooibroek D., Mor S., Moussiopoulos N., Murena F., Niemi J.V., Noe S., Nogueira T., Norman M., Pérez-Camaño J.L., Petäjä T., Piketh S., Rathod A., Reid K., Retama A., Rivera O., Rojas N.Y., Rojas-Quincho J.P., San José R., Sánchez O., Seguel R.J., Sillanpää S., Su Y., Tapper N., Terrazas A., Timonen H., Toscano D., Tsegas G., Velders G.J.M., Vlachokostas C., von Schneidemesser E., Vpm R., Yadav R., Zalakeviciute R., Zavala M. A global observational analysis to understand changes in air quality during exceptionally low anthropogenic emission conditions. Environ. Int. 2021;157 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrecht W., Kubistin D., Plass-Dülmer C., Davies J., Tarasick D.W., von der Gathen P., Deckelmann H., Jepsen N., Kivi R., Lyall N., Palm M., Notholt J., Kois B., Oelsner P., Allaart M., Piters A., Gill M., Van Malderen R., Delcloo A.W., Sussmann R., Mahieu E., Servais C., Romanens G., Stübi R., Ancellet G., Godin-Beekmann S., Yamanouchi S., Strong K., Johnson B., Cullis P., Petropavlovskikh I., Hannigan J.W., Hernandez J.-L., Diaz Rodriguez A., Nakano T., Chouza F., Leblanc T., Torres C., Garcia O., Röhling A.N., Schneider M., Blumenstock T., Tully M., Paton-Walsh C., Jones N., Querel R., Strahan S., Stauffer R.M., Thompson A.M., Inness A., Engelen R., Chang K.-L., Cooper O.R. COVID-19 crisis reduces free tropospheric ozone across the northern hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021;48 doi: 10.1029/2020GL091987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taurino E., Bernetti A., Caputo A., Cordella M., De Lauretis R., D'Elia I., Di Cristofaro E., Gagna A., Gonella B., Moricci F., Peschi E., Romano D., Vitullo M. ISPRA; 2022. Italian Emission Inventory 1990-2020. Informative Inventory Report 2022 (No. 361/2022), ISPRA, Rapporti. [Google Scholar]

- Tremback C.J. Colorado State University, Dept. of Atmospheric Science; Fort Collins, CO 80523: 1990. Numerical Simulation of a Mesoscale Convective Complex: Model Development and Numerical Results (PhD. Dissertation). Atmos. Sci. Paper No. 465. [Google Scholar]

- Vautard R., Bessagnet B., Chin M., Menut L. On the contribution of natural Aeolian sources to particulate matter concentrations in Europe: testing hypotheses with a modelling approach. Atmos. Environ. 2005;39:3291–3303. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.01.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velders G.J.M., Willers S.M., Wesseling J., den Elshout S., van van der Swaluw E., Mooibroek D., van Ratingen S. Improvements in air quality in The Netherlands during the corona lockdown based on observations and model simulations. Atmos. Environ. 2021;247 doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.118158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve P.J., Goldberg M.S. Methodological considerations for epidemiological studies of air pollution and the SARS and COVID-19 coronavirus outbreaks. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020;128 doi: 10.1289/EHP7411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali L., Righini G., Piersanti A., Cremona G., Pace G., Ciancarella L. M-TraCE: a new tool for high-resolution computation and statistical elaboration of backward trajectories on the Italian domain. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2017;129:629–643. doi: 10.1007/s00703-016-0491-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Schneidemesser E., Sibiya B., Caseiro A., Butler T., Lawrence M.G., Leitao J., Lupascu A., Salvador P. Learning from the COVID-19 lockdown in berlin: observations and modelling to support understanding policies to reduce NO2. Atmos. Environ. X. 2021;12 doi: 10.1016/j.aeaoa.2021.100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walko R.L., Band L.E., Baron J., Kittel T.G.F., Lammers R., Lee T.J., Ojima D., Pielke R.A., Taylor C., Tague C., Tremback C.J., Vidale P.L. Coupled atmosphere–biophysics–hydrology models for environmental modeling. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2000;39:931–944. doi: 10.1175/1520-0450(2000)039<0931:CABHMF>2.0.CO. 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walko R.L., Cotton W.R., Meyers M.P., Harrington J.Y. New RAMS cloud microphysics parameterization part I: the single-moment scheme. Atmos. Res. 1995;38:29–62. doi: 10.1016/0169-8095(94)00087-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wesely M.L. Parameterization of surface resistances to gaseous dry deposition in regional scale numerical models. Atmos. Environ. 1989;23:1293–1304. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; 2021. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamartino R.J. Nonnegative, conserved scalar transport using grid-cell-centered, spectrally constrained blackman cubics for applications on a variable-thickness mesh. Mon. Weather Rev. 1993;121:753–763. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1993)121<0753:NCSTUG>2.0.CO. 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.M., Knipping E.M., Wexler A.S., Bhave P.V., Tonnesen G.S. Size distribution of sea-salt emissions as a function of relative humidity. Atmos. Environ. 2005;39:3373–3379. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.