Abstract

Background:

Cannabidiol (CBD), a major cannabinoid of Cannabis sativa, is widely consumed in prescription and non-prescription products. While CBD is generally considered ‘non-intoxicating’, its effects on safety-sensitive tasks are still under scrutiny.

Aim:

We investigated the effects of CBD on driving performance.

Methods:

Healthy adults (n = 17) completed four treatment sessions involving the oral administration of a placebo, or 15, 300 or 1500 mg CBD in a randomised, double-blind, crossover design. Simulated driving performance was assessed between ~45–75 and ~210–240 min post-treatment (Drives 1 and 2) using a two-part scenario with ‘standard’ and ‘car following’ (CF) components. The primary outcome was standard deviation of lateral position (SDLP), a well-established measure of vehicular control. Cognitive function, subjective experiences and plasma CBD concentrations were also measured. Non-inferiority analyses tested the hypothesis that CBD would not increase SDLP by more than a margin equivalent to a 0.05% blood alcohol concentration (Cohen’s dz = 0.50).

Results:

Non-inferiority was established during the standard component of Drive 1 and CF component of Drive 2 on all CBD treatments and during the standard component of Drive 2 on the 15 and 1500 mg treatments (95% CIs < 0.5). The remaining comparisons to placebo were inconclusive (the 95% CIs included 0 and 0.50). No dose of CBD impaired cognition or induced feelings of intoxication (ps > 0.05). CBD was unexpectedly found to persist in plasma for prolonged periods of time (e.g. >4 weeks at 1500 mg).

Conclusion:

Acute, oral CBD treatment does not appear to induce feelings of intoxication and is unlikely to impair cognitive function or driving performance (Registration: ACTRN12619001552178).

Keywords: Cannabidiol, cognition, driving simulation, medicinal cannabis, psychomotor

Introduction

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a terpenophenolic cannabinoid found in the Cannabis sativa plant (ElSohly et al., 2017). CBD has shown considerable therapeutic potential in recent clinical trials (Millar et al., 2019) and is increasingly being used to treat anxiety, epilepsy, chronic pain and other conditions (Arnold et al., 2020). While some CBD products are prescribed (e.g. Epidiolex), the use of non-prescription CBD is also common in Europe and North America where CBD-containing ‘nutraceuticals’ can be purchased over the counter (Goodman et al., 2020; Manthey, 2019). Unlike the other major plant-derived cannabinoid, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) (Arkell et al., 2019, 2020), CBD does not appear to ‘intoxicate’ or have readily discernible subjective effects (Arkell et al., 2020; Arndt and de Wit, 2017; Spindle et al., 2020). However, the impact of CBD on cognitively demanding, safety-sensitive tasks, such as driving, is worthy of investigation, given the substantial and increasing community use.

While several studies have indicated that CBD does not impair cognitive performance on discrete neuropsychological tests (McCartney et al., 2020), only one has directly investigated its effects on driving performance (Arkell et al., 2020). This randomised, placebo-controlled trial involving occasional cannabis users found that vaporised cannabis containing 13.75 mg of CBD (<1.0% Δ9-THC) did not increase standard deviation of lateral position (SDLP), a well-established marker of impaired driving (Verster and Roth, 2011), during an on-road driving test. Measures of cognitive function and subjective intoxication (e.g. feeling ‘stoned’, ‘sedated’, ‘relaxed’, ‘anxious’) were also unaffected by CBD (Arkell et al., 2020). Thus, low doses of vaporised CBD appear unlikely to impair driving performance.

While reassuring, it should be noted that most clinical trials administer CBD orally (e.g. in a solution/oil, capsule or spray) rather than via vaporisation (Millar et al., 2019) and that nutraceuticals and prescription CBD products are often designed for oral ingestion (e.g. oils, capsules, edibles) (McGregor et al., 2020). Route of administration has a profound effect on the pharmacokinetics of CBD, with inhalation producing a rapid and transient peak in blood CBD concentrations and oral consumption eliciting lower peak concentrations hours later (Millar et al., 2018). Dose is another important factor: while nutraceuticals usually contain small amounts of CBD (e.g. ~10–20 mg/mL) (McGregor et al., 2020), the anxiolytic (~300–600 mg) (Bergamaschi et al., 2011; Crippa et al., 2011; Linares et al., 2019; Zuardi et al., 1993), anti-psychotic (~600–1280 mg/d) (Boggs et al., 2018; Leweke et al., 2012; Zuardi et al., 2009) and anticonvulsant (5–20 mg/kg/d) (Devinsky et al., 2017, 2018; Thiele et al., 2018) effects of CBD are only well documented at higher doses.

The current randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigated the effects of acute, oral CBD treatment at doses of 15, 300 and 1500 mg on simulated driving performance, cognitive function and subjective experiences. A non-inferiority approach was used to test the hypothesis that CBD would not increase SDLP by more than the non-inferiority margin (Δ), equivalent to a 0.05% blood alcohol concentration (BAC) (McCartney et al., 2020). This is the legal BAC limit for driving in many jurisdictions (Furtwaengler and De Visser, 2013) and therefore represents the largest ‘tolerable’ amount of driver impairment.

Methods

This investigation was approved by the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee (2019/474) and conducted at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki (1983), and local regulations. The trial protocol is published elsewhere (McCartney et al., 2020) and registered with the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12619001552178).

Study design

Participants completed four treatment sessions involving the oral administration of either placebo or 15, 300 or 1500 mg CBD (CBD-15, CBD-300 and CBD-1500) in a randomised, double-blind, crossover design. Sessions were separated by a washout period ⩾7 days and completed within a maximum of 60 days (median (interquartile range; IQR) washout of 7.5 (7) days). Participants were instructed to avoid using illicit drugs (including cannabis) throughout their involvement.

Participant population

Healthy individuals aged between 18 and 65 years who had held a full (unrestricted) driver’s licence for ⩾ 1 year and had not used cannabis in ⩾3 months were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a clinically significant prior adverse response to cannabis, cannabinoid products or synthetic cannabinoids; (2) a current sleep disorder; (3) current suicidal ideation; (4) a history of (a) drug (including cannabis) and/or alcohol dependence or (b) attempted suicide; (5) a major psychiatric disorder within the last 12 months (except clinically-managed mild depression or anxiety); (6) a body mass index > 30 kg/m2; (7) a high habitual caffeine intake (i.e. >300 mg/d); (8) current use of medications that (a) induce or inhibit the cytochrome (CYP) 450 enzyme system or (b) are metabolised by CYP enzymes that are inhibited by CBD; (9) current use of anticonvulsant medications; (10) required to complete drug testing for cannabis; (10) unwillingness to (a) adhere to pre-trial procedures (see section ‘Experimental procedures’) or (b) refrain from using illicit drugs throughout participation; (11) high likelihood of experiencing simulator sickness; and (12) pregnant or lactating.

All volunteers completed an initial eligibility screen where they were informed of the study requirements and risks before providing written informed consent and being assessed for eligibility by an investigator and independent physician. Eligible participants then practised the full, ~30 min simulated drive and cognitive function tests to reduce learning effects. The eligibility criteria and the recruitment and screening processes are detailed further elsewhere (McCartney et al., 2020).

Experimental procedures

Participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol (⩾24 h) and caffeine (⩾12 h), keep a 24-h diet record (or, if this was not their first session, to replicate the diet they consumed before this) and spend ⩾8 h in bed overnight prior to each session.

Participants arrived at the laboratory between ~07:00 and 09:00 h following an overnight fast and verbally acknowledged compliance with the pre-trial procedures. Breath (Alcotest®, Dräger, Lübeck, Germany), drug (DrugCheck® NxStep Onsite Urine Drug Test), hydration (Palette Digital Refractometer, ATAGO, USA) and pregnancy (Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin Cassette, AlereTM) tests were also performed (as applicable) to verify abstinence from alcohol, cannabis and illicit drugs and to rule out dehydration and pregnancy (McCartney et al., 2020).

Each treatment session involved eight ‘blocks’ of testing: ‘Baseline’ (pre-treatment), ‘Pre-Drive 1’ (between 15 and 45 min post-treatment), ‘Drive 1’ (between 45 and 75 min post-treatment), ‘Post-Drive 1’ (between 75 and 95 min post-treatment), ‘Halfway’ (between 140 and 150 min post-treatment), ‘Pre-Drive 2’ (between 180 and 210 min post-treatment), ‘Drive 2’ (between 210 and 240 min post-treatment) and ‘Post-Drive 2’ (between 240 and 260 min post-treatment). The specific assessments completed during each block are described below and summarised in Table 1 of McCartney et al. (2020). Treatments were administered on completion of the Baseline tests alongside a standardised breakfast; a light standardised snack was also provided ~150 min post-treatment. Participants indicated which treatment they thought they had received and their confidence in this guess (on a 4-point Likert-type scale; 1 = ‘not at all’ to 4 = ‘extremely’) at the end of each session.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Characteristic | Participants (n = 17) |

|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) (n) | 10/7 |

| Age (years) | 27.9 (7.0) |

| Weight (kg) | 67.4 (23.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.0 (4.3) |

| Unsupervised driving experiencea (years) | 9.9 (6.7) |

| Last month driving frequency (day/week) | 4 (5) |

| Last month driving distance (km/week) | 80 (75) |

| Lifetime cannabis exposures (n) | |

| ⩽10 uses | 6 |

| >10 uses | 10 |

| No use | 1 |

| Time since last cannabis use (n) | |

| 3–6 months | 3 |

| 6–12 months | 5 |

| 1–2 years | 3 |

| 2–4 years | 2 |

| >4 years | 3 |

| Lifetime CBD exposures (n) | |

| ⩽10 uses | 1 |

| >10 uses | 2 |

| No use | 14 |

| Time since last CBD use (n) | |

| 3–6 months | 0 |

| 6–12 months | 2 |

| 1–2 years | 1 |

| 2–4 years | 0 |

| >4 years | 0 |

M: males; F: females; CBD: cannabidiol; IQR: interquartile range.

Values are median (IQR) and frequency (n) as appropriate.

Years in possession of a driver’s licence (includes time with a probationary licence).

Study treatments

The investigational product (GD Cann®–C; GD Pharma Pty Ltd, Norwood, South Australia, Australia) was an oral formulation of synthetic CBD (100 mg/mL) in medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil; the placebo was MCT oil (only). It was administered in different volumes (i.e. 150 μL, 3.0 mL or 15 mL) containing 15, 300 or 1500 mg CBD. Each dose was made up to a total equivalent volume of 15 mL via the addition of placebo oil and administered (via oral ingestion) in a high-fat supplement (100 mL; 50 g fat) (Calogen®, Nutricia, Macquarie Park, Australia) intended to increase the bioavailability of CBD (Birnbaum et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2018). Neither the placebo nor active treatment contained any other cannabinoids (including Δ9-THC) or cannabis constituents (e.g. flavonoids, monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes). The products did not differ noticeably in their visual appearance or smell and the preparations administered carried no ‘treatment-identifying’ information (e.g. coded letters or numbers).

Randomisation

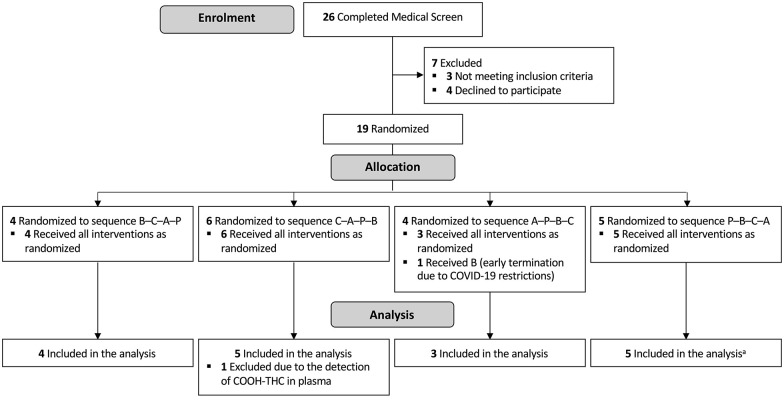

Participants were assigned to one of four possible treatment orders (Figure 1) in a 1:1:1:1 ratio using a pre-populated randomisation schedule. The four orders constituted a Latin square and the schedule was randomly generated in a series of balanced blocks by an independent statistician using SAS (v9.4, Cary, NC) as described elsewhere (McCartney et al., 2020). Only the statistician and those individuals involved in treatment preparation had access to the randomisation schedule (and neither had any contact with participants).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. A: 1500 mg CBD; B: 15 mg CBD; C: 300 mg CBD; P: Placebo. aOne participant failed to complete the ‘Standard Drive’ on each testing occasion and was therefore omitted from the analysis of these outcomes.

Data collection

Simulated driving

Driving performance was measured 45–75 and 210–240 min post-treatment using a fixed-base driving simulator equipped with standard vehicle controls and a custom-built scenario that has demonstrated sensitivity to the effects of Δ9-THC (SCANeR Studio Simulation Engine, v1.6r85, OKTAL, Paris, France) (Arkell et al., 2019). The timing of the second drive was selected to approximately coincide with peak plasma CBD concentrations reported at ~3 h after consuming 25 or 300 mg CBD (Birnbaum et al., 2019; Knaub et al., 2019) and ~4 h after consuming 1500 mg CBD (Taylor et al., 2018). The driving test incorporated two activities detailed elsewhere (McCartney et al., 2020): (1) a 7-min ‘car following’ (CF) component during which participants maintained what they considered a ‘safe distance’ between themselves and a lead vehicle accelerating and decelerating (90–110 km/h) at 30 s intervals and (2) a ~25-min ‘standard’ component (formally termed ‘secondary’ component; Arkell et al., 2019; McCartney et al., 2020) along highway and rural roads with posted speed limits of 110 and between 60–100 km/h, respectively. SDLP was measured throughout both components. Car following distance (‘headway’) and standard deviation (SD) of headway were measured during the CF component (only) and speed and SD of speed were measured during the standard component (only). Data were automatically recorded by the simulator’s software programme at a rate of 20 Hz and all artefacts were removed manually by the same (blinded) investigator using a systematic approach: 10 s of data were removed immediately prior to and following each intentional lane crossing and 60 s were removed immediately prior to and following each ‘incident’ (two hazards and two sets of traffic lights) using time-stamps recorded by the driving simulator software. The data collected during each incident were also removed. Artefacts were only present in the standard component of the drive. Participants were instructed to follow all road rules and drive in the centre of their lane.

Cognitive function

Cognitive function was assessed at Baseline, Pre-Drive 1 and Pre-Drive 2 using three computerised tasks that have previously demonstrated sensitivity to the effects of Δ9-THC (Arkell et al., 2019, 2020; Schlienz et al., 2020; Spindle et al., 2018): the Digit Symbol Substitution Task (DSST) (~1.5 min), Divided Attention Task (DAT) (~4 min) and Paced Serial Addition Task (PSAT) (~3 min). The DRUID® task (~2 min), a computerised application (‘app’) designed to measure drug and/or alcohol-induced impairment, was also completed at these times (Richman and May, 2019). The app generates an overall impairment score between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating increased impairment. A 10-min Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT) (i.e. simple reaction time test) was also performed Post-Drives 1 and 2. These tasks and their associated outcome measures are detailed elsewhere (McCartney et al., 2020). All automatically generated ‘alternate versions’ (i.e. with different stimuli) on each testing occasion to reduce learning effects.

Subjective experiences

Subjective feelings, namely ‘stoned’, ‘sedated’, ‘alert’, ‘anxious’ and ‘sleepy’, were measured at all time points using 100 mm visual analogue scales (VAS), where 0 represented ‘not at all’ and 100 represented ‘extremely’. State anxiety was also measured at these times using the 6-item Short Form State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S) (Marteau and Bekker, 1992). After reversing the scores on ‘positive’ items, the total STAI score was summed and multiplied by 20/6 to generate a result comparable to that obtained on the full, 20-item STAI-S (Marteau and Bekker, 1992). Driving self-efficacy was measured Pre-Drives 1 and 2 using the Adelaide Driving Self Efficacy Scale (ADSES) (George et al., 2007).

Plasma cannabinoid concentrations

Blood was collected into 10 mL pre-treated EDTA vacutainers (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, USA) via an indwelling venous cannula at Baseline and Pre- and Post-Drives 1 and 2. Samples were centrifuged at 2500g for 15 min (4°C) and the plasma supernatant was stored at −80°C. Plasma was thawed for analysis via ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using previously validated methods (Kevin et al., 2021). Target analytes were CBD, Δ9-THC and their major phase-I metabolites.

Cardiovascular measures

Seated heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) were measured at all time points using an automated sphygmomanometer (M2 Basic, Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Measures were taken in duplicate or triplicate if systolic BP differed by >15 mmHg, then averaged.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was SDLP on the simulated driving tests. SDLP is a well-established measure of impaired driving and has been shown to increase dose-dependently with the administration of intoxicating and sedative drugs (e.g. alcohol, Δ9-THC, benzodiazepines) (Dassanayake et al., 2011; Irwin et al., 2017; Veldstra et al., 2015).

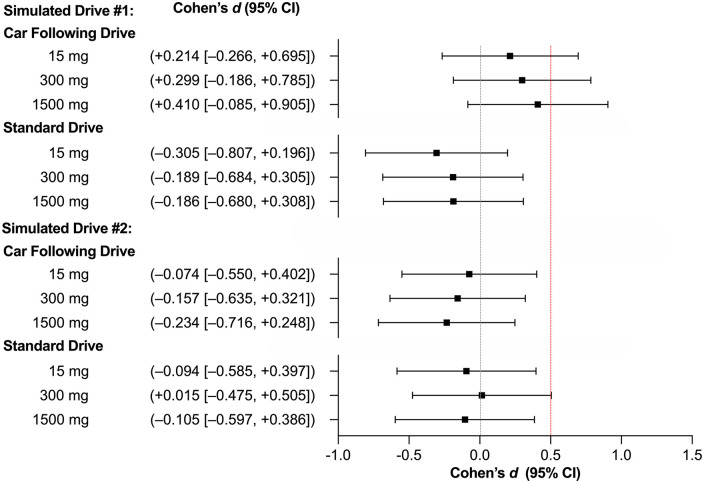

Statistical methods

The primary outcome was subjected to non-inferiority analysis. Δ was defined a priori as a Cohen’s dz effect of 0.50 on the basis of analyses suggesting that a 0.05% BAC (i.e. the largest ‘tolerable’ amount of driver impairment) has an effect of this magnitude on SDLP (see McCartney et al., 2020, for details). Non-inferiority is therefore established if the upper 95% confidence interval (CI) is <0.50. Indeed, this is the preferred way in which to demonstrate that one treatment is not worse than another (Althunian et al., 2017). Note that Δ was not based on prior studies of cannabis or THC as there is limited value in showing CBD is less impairing than a substance that is typically prohibited among drivers (Perkins et al., 2021). Note also that although they could differ in their sensitivity to impairment, the same Δ was used to analyse SDLP data from the standard and CF components of the drive. This was because we did not have a direct measure of alcohol’s effects on our specific driving scenario and instead used data from several other studies to obtain the best possible estimate (see McCartney et al., 2020, for details). Indeed, it would have been difficult to estimate the magnitude of difference (if one exists) between CF and non-CF drives using this approach.

Cohen’s dz effect estimates were calculated by standardising the mean difference between placebo and each intervention performance score against the SD of the performance change (SDΔ) (Lakens, 2013). The standard error (SE) was derived using the Hedges and Olkin approximation adapted for a repeated-measures design (Borenstein et al., 2009; Goulet-Pelletier and Cousineau, 2018b):

| (1) |

where SEd is the SE of Cohen’s d, d is Cohen’s dz, n is the sample size and R is the correlation coefficient. SEd values were then divided by a factor of to derive the SE for Cohen’s dz specifically (Goulet-Pelletier and Cousineau, 2018a, 2018b) and used to calculate 95% CIs. (Note: one participant failed to complete the standard component of each drive (see section ‘Expectancies and adverse events’) and was therefore omitted from the relevant non-inferiority analyses and the statistical analyses of speed and SD of speed described below.)

Secondary outcomes were analysed using linear mixed-effects models and the ‘lme4’ and ‘emmeans’ packages (Bates et al., 2012; Singmann et al., 2019) in RStudio (Version 4.0.1). Variables that were measured at Baseline were analysed as the change from Baseline (i.e. the Baseline measure was subtracted from each measure obtained during a given treatment session prior to analysis); the remainder were analysed as ‘raw scores’. The models included Treatment, Time, and the Treatment × Time interaction as fixed effects (as appropriate) and the participant as a random effect. Models were generated using the restricted maximum likelihood (RML) criterion and no covariance structure was specified (unstructured). The data were log-transformed and reanalysed in the event that residuals were non-normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.05). The first model was retained if the log transformation did not improve normality (Schielzeth et al., 2020). Effect sizes were calculated as partial eta squared . Two-sided (Bonferroni corrected) pairwise comparisons were used to compare estimated marginal means across Treatment, Time or Treatment and Time if a significant effect of Treatment, Time, or a Treatment × Time interaction was observed, respectively. For each variable, the Bonferroni correction was proportional to the total number of post hoc comparisons performed (e.g. six if a main effect of Treatment was observed). Normally and non-normally distributed data are presented as Mean ± SE and median (IQR), respectively unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was accepted as p < 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics

Recruitment for this trial commenced in November 2019 and concluded 12 months later. Nineteen participants were initially randomised (Figure 1). However, one was unable to complete all four treatment sessions within the 60-day (drug expiration) period due to a university-wide suspension on face-to-face research during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Another had detectable levels of 11-COOH-Δ9-THC in plasma (at Baseline) suggesting she had not abstained from cannabis. Both individuals (females) were removed from the final sample. (Note: The retrospective exclusion of the latter participant did not influence the primary outcome; see Figure S1.) The characteristics of the 17 remaining participants are summarised in Table 1. Baseline urine specific gravity (hydration status) (F[3, 48] = 0.745, p = 0.531) and self-reported (pre-trial) sleep duration (F[3, 48] = 0.348, p = 0.791) did not differ across treatments.

The target sample size of 27 (see McCartney et al., 2020) could not be reached within the available resources due to the abovementioned suspension of face-to-face research. A smaller than anticipated sample size in a non-inferiority trial would be expected to yield Cohen’s dz effect estimates with wider 95% CIs, increasing the likelihood of an inconclusive result (i.e. where the 95% CI includes 0 and 0.50 – and the ‘true’ result, inferior or non-inferior, remains to be determined) without compromising the validity of any ‘non-inferior’ results (Schönbrodt and Perugini, 2013). There is also some risk of ‘non-inferior (inferior)’ results (i.e. where the 95% CI does not include 0 or 0.50) being mistaken for ‘standard’ non-inferior results (i.e. where the 95% CI includes 0 but not 0.50); however, both still indicate non-inferiority (i.e. the 95% CI is <0.5) (see also Figure 1 in McCartney et al., 2020).

Primary outcome

The non-inferiority analysis of the primary outcome (SDLP) is displayed in Figure 2; Mean ± SD values are presented in Table 2. Non-inferiority to placebo was established during the standard component of Drive 1 (CBD-15: –1.60 ± 1.31 cm; CBD-300: –0.94 ± 1.25 cm; CBD-1500: –0.87 ± 1.17 cm) and the CF component of Drive 2 (CBD-15: –0.45 ± 1.49 cm; CBD-300: –0.71 ± 1.10 cm; CBD-1500: –1.24 ± 1.28 cm) on all CBD treatments and during the standard component of Drive 2 on CBD-15 (–0.44 ± 1.18 cm) and CBD-1500 (–0.64 ± 1.51 cm). The remaining comparisons (to placebo) were inconclusive (i.e. the 95% CIs included both 0 and 0.50) (CBD-15 on CF Drive 1: +1.04 ± 1.18 cm; CBD-300 on CF Drive 1: +1.43 ± 1.16 cm; CBD-1500 on CF Drive 1: +1.39 ± 0.82 cm; CBD-300 on standard Drive 2: +0.06 ± 1.07 cm). The same results were obtained when the analysis was performed using an unstandardised Δ (see Figure S19). Note also that the numeric differences in SDLP on the standard and CF components of the drive (Table 2) are likely due, in part, to the latter being conducted on a large highway with gentle contours, and part of the former being conducted on a windier rural road.

Figure 2.

SDLP effect sizes (n = 17 on Car Following Drives and n = 16 on Standard Drives). Values are Cohen’s dz (95% CI) (all comparisons to Placebo). Red line represents the non-inferiority margin (Δ). CI: confidence interval. Drive 1 was completed 45–75 min post-treatment and Drive 2 was completed 180–210 min post-treatment.

Table 2.

Measures of simulated driving performance.

| Simulated drive 1 | Simulated drive 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 15 mg | 300 mg | 1500 mg | Placebo | 15 mg | 300 mg | 1500 mg | |

| Car Following component | ||||||||

| SDLP (cm) | 20.0 ± 4.2 | 21.0 ± 5.4 | 21.4 ± 3.7 | 21.4 ± 4.3 | 21.7 ± 5.5 | 21.2 ± 5.1 | 21.0 ± 5.4 | 20.4 ± 5.5 |

| Headway (m) | 81.5 ± 66.2 | 102.5 ± 93.0 | 96.7 ± 103.2 | 89.7 ± 81.8 | 90.8 ± 73.4 | 102.6 ± 109.3 | 93.9 ± 73.2 | 93.0 ± 86.1 |

| SD Headway (m) | 18.3 ± 7.8 | 27.2 ± 21.2 | 22.5 ± 16.3 | 20.7 ± 12.6 | 26.9 ± 23.8 | 26.6 ± 20.3 | 25.4 ± 11.2 | 22.6 ± 11.0 |

| Standard componenta | ||||||||

| SDLP (cm) | 34.4 ± 5.1 | 32.8 ± 4.8 | 33.4 ± 6.2 | 33.5 ± 5.9 | 34.3 ± 4.9 | 33.9 ± 6.1 | 34.4 ± 4.0 | 33.7 ± 6.2 |

| Speed (km/h) | 100.1 ± 6.2 | 98.9 ± 6.4 | 99.0 ± 5.1 | 99.7 ± 5.4 | 103.2 ± 11.7 | 100.6 ± 5.4 | 101.1 ± 5.5 | 101.3 ± 7.0 |

| SD Speed (km/h) | 13.0 ± 2.4 | 14.1 ± 3.6 | 12.2 ± 2.0 | 12.9 ± 2.5 | 13.5 ± 3.1 | 12.8 ± 3.1 | 12.2 ± 2.4 | 12.5 ± 2.9 |

SD: standard deviation; SDLP: standard deviation of lateral position.

Values are Mean ± SD.

Sample size was n = 16 as one participant failed to complete the Standard Drive on each occasion (see section ‘Expectancies and adverse events’).

Drive 1 was completed ~45–75 min post-treatment and Drive 2 was completed ~180–210 min post-treatment. The measures obtained during the standard component of these simulated drives may not be directly comparable to those obtained during previous studies utilising the same task as artefacts (e.g. lane crossing events) were removed in a subtly different (though in both cases, systematic) way.

Secondary outcomes

Measures of driving performance are summarised in Table 2. Measures of cognitive function, subjective experiences and cardiovascular function are displayed in Figures S2–S9; note that ‘raw scores’ for variables that were measured at Baseline (and therefore analysed as the change from Baseline as described in section ‘Statistical methods’) are also presented in Figures S10–S15. These data were included for completeness and were not subjected to statistical analysis. The results of the statistical comparisons are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the statistical analyses of driving performance, cognitive function, subjective experiences, and cardiovascular parameters (n = 17).

| Outcome | Treatment effect | Time effect | Interaction effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-ratio | p-value | F-ratio | p-value | F-ratio | p-value | ||||

| Driving performance | |||||||||

| SDLP (CF) | – | – | – | 0.018 | 0.893 | <0.01 | – | – | – |

| Headway | 0.700 | 0.553 | 0.02 | 0.746 | 0.389 | <0.01 | 0.311 | 0.816 | <0.01 |

| SD Headway | 0.508 | 0.677 | 0.03 | 3.81 | 0.053 | 0.03 | 0.684 | 0.563 | 0.03 |

| SDLP (Standard) | – | – | – | 0.850 | 0.359 | <0.01 | – | – | – |

| Speed | 1.15 | 0.329 | 0.03 | 8.37 | 0.005 | 0.07 | 0.160 | 0.922 | <0.01 |

| SD Speed | 2.35 | 0.076 | 0.06 | 1.18 | 0.278 | 0.01 | 1.24 | 0.297 | 0.03 |

| Cognitive function | |||||||||

| DSST | |||||||||

| Correct responses | 0.325 | 0.807 | <0.01 | 1.77 | 0.186 | 0.02 | 0.113 | 0.952 | <0.01 |

| Response accuracy | 0.637 | 0.593 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.982 | <0.01 | 0.234 | 0.872 | <0.01 |

| DAT | |||||||||

| Tracking error | 4.75 | 0.004 | 0.11 | 0.211 | 0.647 | <0.01 | 0.742 | 0.529 | 0.02 |

| Hits | 0.476 | 0.700 | 0.01 | 0.167 | 0.684 | <0.01 | 0.085 | 0.968 | <0.01 |

| Response time | 1.67 | 0.176 | 0.04 | 0.105 | 0.746 | <0.01 | 1.09 | 0.356 | 0.03 |

| PSAT | |||||||||

| Correct responses | 2.49 | 0.064 | 0.06 | 0.040 | 0.841 | <0.01 | 0.118 | 0.949 | <0.01 |

| Response time | 2.54 | 0.060 | 0.06 | 0.731 | 0.394 | <0.01 | 0.429 | 0.733 | 0.01 |

| DRUID | |||||||||

| Total score | 1.03 | 0.381 | 0.03 | 0.347 | 0.557 | <0.01 | 0.521 | 0.669 | 0.01 |

| PVT | |||||||||

| Response time | 1.09 | 0.353 | 0.03 | 0.243 | 0.623 | <0.01 | 0.118 | 0.949 | <0.01 |

| Lapses | 1.87 | 0.138 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.973 | <0.01 | 0.405 | 0.749 | 0.01 |

| Subjective experiences | |||||||||

| Stoned | 1.04 | 0.377 | 0.01 | 5.39 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.535 | 0.891 | 0.02 |

| Sedated | 0.500 | 0.682 | <0.01 | 8.03 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.569 | 0.867 | 0.02 |

| Alert | 2.07 | 0.104 | 0.02 | 3.19 | 0.014 | 0.04 | 0.190 | 0.999 | <0.01 |

| Anxious | 7.54 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.545 | 0.703 | <0.01 | 0.200 | 0.999 | <0.01 |

| Sleepy | 2.27 | 0.081 | 0.02 | 11.7 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.613 | 0.831 | 0.02 |

| State anxiety | 2.20 | 0.088 | 0.02 | 2.42 | 0.048 | 0.03 | 0.389 | 0.967 | 0.02 |

| Driving self-efficacy | 0.654 | 0.581 | 0.02 | 8.37 | 0.005 | 0.07 | 0.386 | 0.762 | 0.01 |

| CV Function | |||||||||

| Heart rate | 1.40 | 0.243 | 0.01 | 1.96 | 0.100 | 0.03 | 0.263 | 0.994 | 0.01 |

| Systolic BP | 2.27 | 0.080 | 0.02 | 0.965 | 0.427 | 0.01 | 0.810 | 0.640 | 0.03 |

| Diastolic BP | 1.93 | 0.125 | 0.02 | 2.71 | 0.031 | 0.03 | 0.415 | 0.957 | 0.02 |

–: not applicable; CF: car following drive; CV: cardiovascular; DAT: Divided Attention Task; DSST: Digit Symbol Substitution Task; PSAT: Paced Serial Addition Task; PVT: Psychomotor Vigilance Test; Standard: standard drive; SD: standard deviation; SDLP: standard deviation of lateral position; BP: blood pressure.

Bold p-values are significant (p < 0.05).

Driving performance

Speed differed across Time (Table 3) with participants travelling faster during Drive 2 than Drive 1 (p = 0.005; Table 2). No other significant differences were observed.

Cognitive function

Tracking error, that is, the mean distance between the cursor and the target, on the DAT indicated an effect of Treatment (Table 3; Figures S3 and S11) with less error (relative to baseline) observed on CBD-300 (–0.16 ± 0.31 vs +1.21 ± 0.43, p = 0.011) and CBD-1500 (–0.19 ± 0.43 vs +1.21 ± 0.43, p = 0.007) than CBD-15. No other significant differences were observed.

Subjective experiences

VAS ratings of stoned, sedated, alert and sleepy as well as scores on the ADSES and STAI questionnaires differed across Time but did not indicate effect of Treatment or a Treatment × Time interaction (Table 3; Figures S7, S8 and S14). Relative to baseline, participants felt

More stoned Post-Drive 1 (+4 ± 2 mm) than Pre-Drive 1 (+1 ± 1 mm, p = 0.006), Pre-Drive 2 (+1 ± 1 mm, p = 0.001) and Post-Drive 2 (+1 ± 1 mm, p = 0.002);

More sedated (ps < 0.002) Post-Drive 1 (+10 ± 5 mm) than Pre-Drive 1 (+2 ± 2 mm), Halfway (+4 ± 3 mm), Pre-Drive 2 (+3 ± 2 mm) and Post-Drive 2 (+4 ± 3 mm);

Less alert Post-Drive 1 than Pre-Drive 2 (–2 ± 5 vs +7 ± 5 mm, p = 0.021);

Sleepier (ps < 0.001) Post-Drive 1 (+11 ± 5 mm) than Pre-Drive 1 (–3 ± 3 mm) and Pre-Drive 2 (+1 ± 5 mm);

Sleepier Post-Drive 2 (+6 ± 5 mm) than Pre-Drive 1 (–3 ± 3 mm, p < 0.001) and Pre-Drive 2 (+1 ± 5 mm, p = 0.027);

Sleepier Halfway than Pre-Drive 1 (+6 ± 5 vs −3 ± 3 mm, p = 0.004).

Driving self-efficacy was also higher Pre-Drive 2 than Pre-Drive 1 (108 ± 4 vs 103 ± 5, p = 0.005). Post hoc comparisons for state anxiety did not reach statistical significance (ps > 0.10). These observations suggest the driving tests induced some degree of fatigue.

VAS ratings of anxiousness indicated an effect of Treatment (Table 3; Figures S7 and S14) with higher ratings (relative to baseline) observed on placebo (+0 ± 1 mm) than CBD-300 (–6 ± 4 mm, p < 0.001) and CBD-1500 (–4 ± 3 mm, p = 0.033) and on CBD-15 (+0 ± 2 mm) than CBD-300 (–6 ± 4 mm, p = 0.001) and CBD-1500 (–4 ± 3 mm, p = 0.040). No other significant differences were observed.

Cardiovascular function

Diastolic BP indicated an effect of Time (Table 3; Figures S9 and S15) with higher BP (relative to baseline) observed Pre-Drive 1 than Post-Drive 1 (–4.6 ± 6.0 vs −2.0 ± 6.1 mmHg, p = 0.025). No other significant differences were observed.

Plasma cannabinoid concentrations

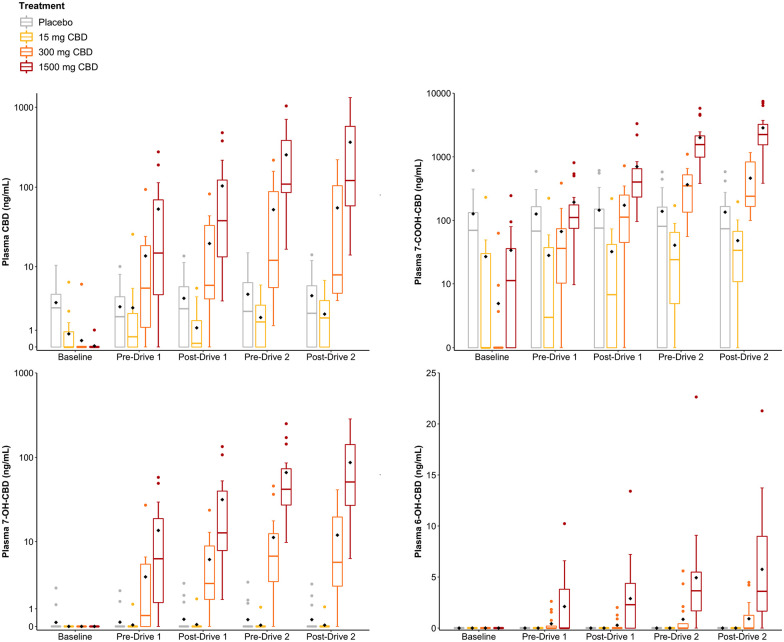

Plasma CBD, 7-COOH-CBD, 7-OH-CBD and 6-OH-CBDconcentrations are presented in Figure 3. Several participants were unexpectedly found to have detectable levels of CBD and CBD metabolites in plasma at Baseline on (and throughout) their placebo trial (CBD: n = 12, mean (range) = 4.7 (1.4–10.4) ng/mL; 7-COOH-CBD: n = 12, 180 (61–609) ng/mL; 7-OH-CBD: n = 2, 1.9 (1.3–2.5) ng/mL) (Figure S16). Each of these individuals received CBD-1500 at their last visit between 7 and 29 days earlier suggesting that this high dose produced prolonged residual concentrations of CBD and CBD metabolites in plasma. (Note: The Latin square generated during randomisation was ‘unbalanced’ such that each treatment was not preceded equally often by every other treatment; Figure 1.) Indeed, we identified a moderate, though not statistically significant, negative (Spearman’s) correlation between residual plasma CBD concentrations and the length of the washout period (in days) among these 12 individuals (R = 0.53, p = 0.075).

Figure 3.

Plasma CBD, 7-COOH-CBD, 7-OH-CBD and 6-OH-CBD and concentrations (n = 17). Baseline is pre-treatment; Pre-Drive 1 is ~45 min post-treatment, Post-Drive 1 is ~75 min post-treatment, Pre-Drive 2 is ~210 min post-treatment and Post-Drive 2 is ~240 min post-treatment. Grey: Placebo, Yellow: 15 mg CBD; Orange: 300 mg CBD and Red: 1500 mg CBD. The black diamond represents the mean value.

Some participants also had detectable levels of CBD and CBD metabolites in plasma at Baseline on their CBD-15 trial (CBD: n = 5; mean (range) = 2.5 (0.8–6.3) ng/mL; 7-COOH-CBD: n = 7; 62 (15–230) ng/mL) (Figure S16). Each of these individuals received placebo at their last visit but CBD-1500 between 14 and 39 days earlier. CBD and 7-COOH-CBD were also detected in plasma at Baseline on a number of CBD-300 (CBD: n = 1; 7-COOH-CBD: n = 3) and CBD-1500 (CBD: n = 1; 7-COOH-CBD: n = 11) trials (Figure S16). Δ9-THC, 11-COOH-Δ9-THC and 11-OH-Δ9-THC were not detected in any of the samples obtained from the 17 included participants.

Expectancies and adverse events

Participants correctly identified the treatment received on 11 (16%) occasions (Placebo: 3 (18%); CBD-15: 3 (18%); CBD-300: 4 (24%); CBD-1500: 1 (6%)) (Figure S17). Individuals were not at all (n = 4), somewhat (n = 2), moderately (n = 4) and extremely (n = 1) confident they had correctly guessed their assigned treatment in each instance.

No serious adverse events occurred. One participant fainted during the Baseline blood draw; she completed the treatment session; however, her involvement in the trial was ultimately terminated due to the abovementioned suspension of face-to-face research. A second participant felt nauseated ~20 min into the first driving test (after receiving the placebo treatment) and later vomited (despite having practised the driving test without complications during the eligibility screen). She completed the treatment session, but only performed the CF component (i.e. first ~7 min) of each subsequent drive (see section ‘Statistical methods’). The participant appeared to drive similarly during the CF component of her first and subsequent driving tests and her exclusion did not influence the primary outcome (Figure S18).

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of acute, oral CBD treatment on simulated driving performance, cognitive function and subjective experiences. A non-inferiority design was used to test the hypothesis that CBD would not increase SDLP by more than Δ, the approximate level of impairment observed at 0.05% BAC. With recent evidence suggesting that low doses of vaporised CBD do not impair driving performance (Arkell et al., 2020), and additional reports that CBD (in general) does not affect cognitive function or induce feelings of intoxication (Arkell et al., 2020; Arndt and de Wit, 2017; Spindle et al., 2020), the expectation was that orally administered CBD would not influence these outcomes, even at high doses.

The effects of CBD on SDLP during Drive 2 (~3.5–4 h post-treatment) support this hypothesis. Indeed, neither CBD-15, CBD-300 nor CBD-1500 appeared to increase SDLP during the CF or standard components of this drive, though CBD-300 technically had an inconclusive effect on the latter with the upper 95% CI just exceeding (+0.005) the non-inferiority margin. The average increase in SDLP on this treatment and task was negligible (+0.06 cm).

While all three CBD treatments also demonstrated non-inferiority during the standard component of Drive 1 (~45–75 min post-treatment), suggesting no effect on SDLP, their effects on the CF component were inconclusive, that is, these analyses were underpowered to determine the impact of CBD. As CBD did not affect SDLP during the standard component of this drive and plasma CBD concentrations were lower at this time than during Drive 2, where non-inferiority was established, it seems likely that a larger participant sample would yield a ‘non-inferior’ result. However, it is important to acknowledge that the CF task has demonstrated greater sensitivity to Δ9-THC-induced impairment than the standard drive (Arkell et al., 2019). In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that CBD has ‘phasic’ pharmacological effects, for example, stronger (or differing) effects on initial exposure than at maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax). On the contrary, the average ‘change’ in SDLP observed (during CF) on each of these treatments (+1.0–1.4 cm) was smaller than typically reported during intoxication with other drugs (e.g. ~2.5 cm) (Verster and Roth, 2011) (see also Figure S19) – and considerably less than previously observed with 13.75 mg Δ9-THC in another RCT employing exactly the same simulated driving test (~3.9 cm) (Arkell et al., 2020).

The effects of CBD on cognitive function and subjective experiences were also investigated. However, unlike SDLP, these data were analysed in an exploratory fashion using traditional, statistical techniques (i.e. test of ‘superiority’) as it would have been difficult to define Δ for each individual outcome. No dose of CBD impaired performance on the DSST, DAT, PSAT, PVT or DRUID® task. However, tracking performance on the DAT did differ among active treatments with more error observed on CBD-15 than CBD-300 and CBD-1500. This finding is somewhat difficult to interpret as no significant differences to placebo were observed, that is, it is unclear whether CBD-15 impaired or CBD-300 and CBD-1500 enhanced tracking performance (or both). The fact that (1) no other cognitive effects were observed; (2) studies do not typically detect significant effects of CBD on cognitive function (McCartney et al., 2020); and (3) 10 different cognitive function variables were measured suggests that the result could be a Type II Error. The only subjective measure to demonstrate an effect of treatment in this trial was ‘anxiousness’, with marginally higher VAS ratings (~5 mm) observed on placebo and CBD-15 than CBD-300 and CBD-1500. This finding adds to a growing body of evidence that CBD has anxiolytic properties (Bergamaschi et al., 2011; Crippa et al., 2011; Linares et al., 2019; Zuardi et al., 1993). Overall, these observations suggest that CBD does not impair cognitive function or induce feelings of intoxication. However, it is important to acknowledge that, given our relatively small sample size, these superiority analyses could have been underpowered to detect otherwise significant effects.

One limitation of this investigation is that 12 participants were unexpectedly found to have low but detectable levels of CBD in plasma on their placebo trial. Each of these individuals had received CBD-1500 at their last visit (up to 29 days earlier) suggesting it was residual from this high dose. Indeed, cannabinoids are highly lipophilic molecules and the persistence of Δ9-THC in biological matrices despite weeks or months of abstinence is a well-documented phenomenon believed to reflect its retention in adipose tissue (Wong et al., 2013). The current observation suggests that CBD may be retained in a similar manner, an effect that, to our knowledge, has not been well described in previous pharmacokinetic studies. A key phase-one trial (Taylor et al., 2018) during which participants were administered 1500, 3000 or 4500 mg CBD followed by two separate 1500 mg doses at intervals of ⩾7 days did not appear to report their participants’ baseline (pre-treatment) plasma CBD concentrations (i.e. after prior dosing). The authors simply noted that their statistical analyses ‘suggested’ residual CBD was present in plasma after the washout period (Taylor et al., 2018). Another study (Taylor et al., 2020) observed mean plasma CBD concentrations of ~30 ng/mL 2 weeks after administering 750 mg CBD twice daily for 4 weeks. It is important to recognise that the residual CBD detected in the current investigation is unlikely to reflect ‘other’ recent CBD use (i.e. outside of the trial) as CBD is not available (legally) without a prescription in Australia (McGregor et al., 2020) and was not detected in any Baseline oral fluid samples (i.e. the presence of CBD in oral fluid would indicate recent use) (data published elsewhere; McCartney et al., 2022).

It is important to consider the extent to which this residual CBD affected driving performance and/or other outcomes on the placebo treatment. In this regard, it is worth noting that residual plasma CBD concentrations were very low (e.g. at Baseline on the placebo treatment (n = 12), mean (range) = 4.7 (1.4–10.4) ng/mL) and similar to the (peak) plasma CBD concentrations observed on the 15 mg CBD treatment (4.7 (0.0–25.7) ng/mL) (when no CBD was present at Baseline). This is important because no RCTs appear to have detected meaningful phenotypic effects of CBD at doses <200 mg (Chagas et al., 2014; Freeman et al., 2020; Jadoon et al., 2016; Linares et al., 2019; Lopez et al., 2020; Naftali et al., 2017; Zuardi et al., 2017). It is therefore unlikely that these low, residual levels of CBD influenced performance.

Second, no obvious or substantial differences in SDLP were observed among those participants who did (n = 12) versus did not (n = 5) have residual CBD in plasma on their placebo trial (Table S1). Indeed, these groups had very similar (i.e. differed by ⩽ 1.0 cm) average SDLP values on the CF component of Drives 1 and 2 and the Standard component of Drive 2. Thus, while results should be interpreted with some caution, this residual CBD appears unlikely to have had a major effect on the current trial. Future studies should, however, take care to measure plasma CBD concentrations (as this is not frequently done; Millar et al., 2019) and be mindful that CBD doses ⩾300 mg may not ‘washout’ within 7 days. Whether 7-COOH-CBD and 7-OH-CBD, also present in plasma on the placebo trial, can elicit pharmacological effects in humans is yet to be established (Ujváry and Hanuš, 2016).

The current trial administered CBD in combination with a high fat supplement as previous studies have found that the administration of a high-fat meal greatly increases plasma CBD concentrations (Birnbaum et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2018). Unfortunately, plasma CBD concentrations varied among participants (as is typical) and did not appear elevated above ‘usual’ levels observed in fasted participants (although Cmax could not be reliably estimated and a ‘no supplement’ control was not used).

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that acute, oral CBD treatment at doses up to 1500 mg does not induce feelings of intoxication and is unlikely to impair cognitive function or driving performance. However, further research is required to confirm no effect of CBD on safety-sensitive tasks in the hours immediately post-treatment and with chronic administration.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-jop-10.1177_02698811221095356 for Effects of cannabidiol on simulated driving and cognitive performance: A dose-ranging randomised controlled trial by Danielle McCartney, Anastasia S Suraev, Peter T Doohan, Christopher Irwin, Richard C Kevin, Ronald R Grunstein, Camilla M Hoyos and Iain S McGregor in Journal of Psychopharmacology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jop-10.1177_02698811221095356 for Effects of cannabidiol on simulated driving and cognitive performance: A dose-ranging randomised controlled trial by Danielle McCartney, Anastasia S Suraev, Peter T Doohan, Christopher Irwin, Richard C Kevin, Ronald R Grunstein, Camilla M Hoyos and Iain S McGregor in Journal of Psychopharmacology

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Melissa Benson, Zoe Schrire, Sarah Abelev, Jun Zhi Teh, and Isobel Lavender for their assistance with trial activities; Dr Yizhong Zheng, Dr Tom Altree, and Dr Henry Ainge-Allen for their assistance conducting medical screens; Dr Lewis Martin for his statistical advice and all of the participants in the trial. We are grateful to Barry and Joy Lambert and family for their ongoing support of the research activities of the Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Author contributions: D.M., A.S.S., C.I., R.R.G., C.M.H. and I.S.M. contributed to the conception and design of the research project; D.M. and A.S.S. were involved in data acquisition; P.T.D. and R.C.K. were involved in biospecimen analysis; C.I. was involved in developing the simulated driving test; D.M. and I.S.M. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the research data; and all authors were involved in drafting and critically revising the manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: D.M., A.S.S., P.T.D., R.C.K. and I.S.M. receive salary support from the Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics. I.S.M. also acts as a consultant to Kinoxis Therapeutics and is an inventor on several patents relating to novel cannabinoid therapeutics. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research project was funded by the Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics, a philanthropically funded centre for medicinal cannabis research at the University of Sydney.

ORCID iD: Danielle McCartney  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7783-5220

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7783-5220

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Althunian TA, deBoer A, Groenwold RHH, et al. (2017). Defining the noninferiority margin and analysing noninferiority: An overview. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 83(8): 1636–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkell TR, Lintzeris N, Kevin RC, et al. (2019) Cannabidiol (CBD) content in vaporized cannabis does not prevent tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-induced impairment of driving and cognition. Psychopharmacology 236(9): 2713–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkell TR, Vinckenbosch F, Kevin RC, et al. (2020) Effect of Cannabidiol and Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol on driving performance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324(21): 2177–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt DL, de Wit H. (2017) Cannabidiol does not dampen responses to emotional stimuli in healthy adults. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 2(1): 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JC, Nation T, McGregor IS. (2020) Prescribing medicinal cannabis. Australian Prescriber 43(5): 152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, et al. (2012) Package ‘lme4’. CRAN. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RHC, Chagas MHN, et al. (2011) Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-naive social phobia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 36(6): 1219–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum AK, Karanam A, Marino SE, et al. (2019) Food effect on pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol oral capsules in adult patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia 60(8): 1586–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs DL, Surti T, Gupta A, et al. (2018). The effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on cognition and symptoms in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia a randomized placebo controlled trial. Psychopharmacology 235(7): 1923–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al. (2009) Introduction to Meta-Analysis. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons [Google Scholar]

- Chagas MH, Zuardi AW, Tumas V, et al. (2014) Effects of cannabidiol in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: An exploratory double-blind trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 28(11): 1088–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Derenusson GN, Ferrari TB, et al. (2011) Neural basis of anxiolytic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in generalized social anxiety disorder: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 25(1): 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassanayake T, Michie P, Carter G, et al. (2011) Effects of benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids on driving. Drug Safety 34(2): 125–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, et al. (2017) Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 376(21): 2011–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Patel AD, Cross JH, et al. (2018) Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 378(20): 1888–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElSohly MA, Radwan MM, Gul W, et al. (2017) Phytochemistry of Cannabis sativa L. Phytocannabinoids: 1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman TP, Hindocha C, Baio G, et al. (2020). Cannabidiol for the treatment of cannabis use disorder: A phase 2a, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, adaptive Bayesian trial. The Lancet Psychiatry 7(10): 865–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtwaengler NA, De Visser RO. (2013) Lack of international consensus in low-risk drinking guidelines. Drug and Alcohol Review 32(1): 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S, Clark M, Crotty M. (2007) Development of the Adelaide Driving Self-Efficacy Scale. Clinical Rehabilitation 21(1): 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S, Wadsworth E, Schauer G, et al. (2020) Use and perceptions of Cannabidiol products in Canada and in the United States. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. Epub ahead of print 20 November. DOI: 10.1089/can.2020.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulet-Pelletier J-C, Cousineau D. (2018. a) Corrigendum to ‘A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, part I: The Cohen’s d family’. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology 15(1): 54–54. [Google Scholar]

- Goulet-Pelletier J-C, Cousineau D. (2018. b) A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, part I: The Cohen’s d family. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology 14(4): 242–265. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin C, Iudakhina E, Desbrow B, et al. (2017) Effects of acute alcohol consumption on measures of simulated driving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Accident; Analysis and Prevention 102: 248–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadoon KA, Ratcliffe SH, Barrett DA, et al. (2016) Efficacy and safety of cannabidiol and tetrahydrocannabivarin on glycemic and lipid parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group pilot study. Diabetes Care 39(10): 1777–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevin RC, Vogel R, Doohan P, et al. (2021) A validated method for the simultaneous quantification of cannabidiol, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, and their metabolites in human plasma and application to plasma samples from an oral cannabidiol open-label trial. Drug Testing and Analysis 13: 614–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaub K, Sartorius T, Dharsono T, et al. (2019) A Novel Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System (SEDDS) based on VESIsorb® formulation technology improving the oral bioavailability of cannabidiol in healthy subjects. Molecules 24(16): 2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D. (2013) Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology 4: Article 863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leweke F, Piomelli D, Pahlisch F, et al. (2012) Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Translational Psychiatry 2(3): e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares IM, Zuardi AW, Pereira LC, et al. (2019) Cannabidiol presents an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve in a simulated public speaking test. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999) 41(1): 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez HL, Cesareo KR, Raub B, et al. (2020) Effects of hemp extract on markers of wellness, stress resilience, recovery and clinical biomarkers of safety in overweight, but otherwise healthy subjects. Journal of Dietary Supplements 17(5): 561–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey J. (2019) Cannabis use in Europe: Current trends and public health concerns. The International Journal on Drug Policy 68: 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Bekker H. (1992) The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State – Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The British Journal of Clinical Psychology 31(3): 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney D, Benson MJ, Suraev AS, et al. (2020). The effect of cannabidiol on simulated car driving performance: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, dose-ranging clinical trial protocol. Human Psychopharmacology 35(5): e2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney D, Kevin RC, Suraev AS, et al. (2022) Orally administered cannabidiol (CBD) does not produce false-positive tests for THC on the Securetec DrugWipe® 5S or Dräger Drug Test® 5000. Drug Testing and Analysis 14: 137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor IS, Cairns EA, Abelev S, et al. (2020) Access to cannabidiol without a prescription: A cross-country comparison and analysis. The International Journal on Drug Policy 85: 102935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar SA, Stone NL, Bellman ZD, et al. (2019) A systematic review of cannabidiol dosing in clinical populations. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 85(9): 1888–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar SA, Stone NL, Yates AS, et al. (2018) A systematic review on the pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol in humans. Frontiers in Pharmacology 9: 1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naftali T, Mechulam R, Marii A, et al. (2017) Low-dose cannabidiol is safe but not effective in the treatment for Crohn’s disease, a randomized controlled trial. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 62(6): 1615–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins D, Brophy H, McGregor IS, et al. (2021) Medicinal cannabis and driving: The intersection of health and road safety policy. The International Journal on Drug Policy 97: 103307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman J, May S. (2019) An investigation of the DRUID® smartphone/tablet app as a rapid screening assessment for cognitive and psychomotor impairment associated with alcohol intoxication. Vision Development & Rehabilitation 5(1): 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Schielzeth H, Dingemanse NJ, Nakagawa S, et al. (2020) Robustness of linear mixed-effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11(9): 1141–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Schlienz NJ, Spindle TR, Cone EJ, et al. (2020) Pharmacodynamic dose effects of oral cannabis ingestion in healthy adults who infrequently use cannabis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 211: 107969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönbrodt FD, Perugini M. (2013) At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality 47(5): 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- Singmann H, Love J, Buerkner P, et al. (2019) Package ‘emmeans’. CRAN R Project. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/emmeans.pdf (accessed 10 April 2020).

- Spindle TR, Cone EJ, Goffi E, et al. (2020) Pharmacodynamic effects of vaporized and oral cannabidiol (CBD) and vaporized CBD-dominant cannabis in infrequent cannabis users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 211: 107937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindle TR, Cone EJ, Schlienz NJ, et al. (2018) Acute effects of smoked and vaporized cannabis in healthy adults who infrequently use cannabis: A crossover trial. JAMA Network Open 1(7): e184841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L, Crockett J, Tayo B, et al. (2020) Abrupt withdrawal of cannabidiol (CBD): A randomized trial. Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B 104(PtA): 106938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L, Gidal B, Blakey G, et al. (2018) A phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single ascending dose, multiple dose, and food effect trial of the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of highly purified cannabidiol in healthy subjects. CNS Drugs 32(11): 1053–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele EA, Marsh ED, French JA, et al. (2018) Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet 391(10125): 1085–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujváry I, Hanuš L. (2016) Human metabolites of cannabidiol: A review on their formation, biological activity, and relevance in therapy. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 1(1): 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldstra JL, Bosker WM, deWaard D, et al. (2015) Comparing treatment effects of oral THC on simulated and on-the-road driving performance: Testing the validity of driving simulator drug research. Psychopharmacology 232(16): 2911–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verster JC, Roth T. (2011) Standard operation procedures for conducting the on-the-road driving test, and measurement of the standard deviation of lateral position (SDLP). International Journal of General Medicine 4: 359–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A, Montebello ME, Norberg MM, et al. (2013) Exercise increases plasma THC concentrations in regular cannabis users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 133(2): 763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW, Cosme RA, Graeff FG, et al. (1993). Effects of ipsapirone and cannabidiol on human experimental anxiety. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 7(1, Suppl.): 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Hallak JE, et al. (2009) Cannabidiol for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 23(8): 979–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW, Rodrigues NP, Silva AL, et al. (2017) Inverted U-shaped dose-response curve of the anxiolytic effect of cannabidiol during public speaking in real life. Frontiers in Pharmacology 8: 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-jop-10.1177_02698811221095356 for Effects of cannabidiol on simulated driving and cognitive performance: A dose-ranging randomised controlled trial by Danielle McCartney, Anastasia S Suraev, Peter T Doohan, Christopher Irwin, Richard C Kevin, Ronald R Grunstein, Camilla M Hoyos and Iain S McGregor in Journal of Psychopharmacology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jop-10.1177_02698811221095356 for Effects of cannabidiol on simulated driving and cognitive performance: A dose-ranging randomised controlled trial by Danielle McCartney, Anastasia S Suraev, Peter T Doohan, Christopher Irwin, Richard C Kevin, Ronald R Grunstein, Camilla M Hoyos and Iain S McGregor in Journal of Psychopharmacology