Abstract

User measurement bias during subcutaneous tumor measurement is a source of variation in preclinical in vivo studies. We investigated whether this user variability could impact efficacy study outcomes, in the form of the false negative result rate when comparing treated and control groups. Two tumor measurement methods were compared; calipers which rely on manual measurement, and an automatic 3D and thermal imaging device. Tumor growth curve data were used to create an in silico efficacy study with control and treated groups. Before applying user variability, treatment group tumor volumes were statistically different to the control group. Utilizing data collected from 15 different users across 9 in vivo studies, user measurement variability was computed for both methods and simulation was used to investigate its impact on the in silico study outcome. User variability produced a false negative result in 0.7% to 18.5% of simulated studies when using calipers, depending on treatment efficacy. When using an imaging device with lower user variability this was reduced to 0.0% to 2.6%, demonstrating that user variability impacts study outcomes and the ability to detect treatment effect. Reducing variability in efficacy studies can increase confidence in efficacy study outcomes without altering group sizes. By using a measurement device with lower user variability, the chance of missing a therapeutic effect can be reduced and time and resources spent pursuing false results could be saved. This improvement in data quality is of particular interest in discovery and dosing studies, where being able to detect small differences between groups is crucial.

Keywords: Tumor models, in silico, in vivo, tumor imaging, 3D-TI, study reproducibility, efficacy study

Introduction

Subcutaneous tumor xenograft models are used to study tumor progression and responses in vivo. Tumor volume is the most commonly used metric to monitor progression of tumor and response to treatments. Tumor volume is calculated using 2 or more dimensions; most commonly length and width, using tumor width as a proxy for height.1 These dimensions are measured manually (with calipers), or by using imaging techniques including MRI, CT, fluorescence, or 3D imaging combined with a thermal signature.2-5 Calipers are the most common tool of choice due to their low cost, however they produce less precise, more variable results than CT,3 ultrasound,6 and 3D and thermal imaging methods5 due to user measurement variation (also referred to as user variability or inter-operator variability). Caliper users must determine the longest tumor length and its perpendicular width by eye which is highly subjective,7 and the mechanical nature of calipers adds further variation by allowing the tumor to be squeezed, influencing its shape, and recorded dimensions.

The user variability problem in tumor measurement has been addressed in the clinical field and has been found to affect MR and CT imaging techniques that rely on manual measurement methods.8,9 Computer-aided tumor measurement can be used to more precisely assess tumor volume by removing user variability and bias, and software now exists to define and measure tumor dimensions automatically as part of imaging methods. Therefore, sources of user measurement variation can be removed by imaging methods that use algorithms and machine learning to determine the longest length and width automatically, and by designing tools that do not come into contact with the tumor. Partial or fully automatic image processing and tumor measurement has been widely adopted in oncology clinics, setting a precedent for this technology to improve data quality and throughput in preclinical trials.9,10 Automatic tumor measurement with 3D and thermal tumor imaging has indeed been shown to significantly reduce user measurement variability in subcutaneous in vivo studies.5,11

Cancer research is affected by a reproducibility crisis, with estimates of published studies that can be reproduced by another team as low as 11%.12 This irreproducibility stems from many sources including study design and data reporting,13,14 variation within animal models,15 and use of low quality or misidentified biospecimens and cell lines.16,17 Lower precision during measurement also affects study reproducibility; caliper users cannot swap in and out of studies as the user measurement variability is so high that measurements between users are often not comparable, even when measuring the same animal. Thus, reducing measurement variability is a promising option to achieve greater repeatability of results. Caliper measurement variability is a known problem, however their use is still ubiquitous, and the effects on study endpoints have not been investigated in detail.

High attrition of drugs during late-stage clinical trials is another prevalent problem in oncology, where only 5% of drugs in Phase I will be successfully licensed.18 A greater focus of resources at the preclinical drug discovery stage (the “quick win, fast fail” paradigm where drug candidates are filtered out during preclinical testing) has been suggested as a solution to reduce drug development costs.19 More certainty of drug effects earlier on will reduce attrition and costs downstream, but this method is also dependent on a low false negative rate so that effective drugs are not discarded. Decreasing user variability is therefore a viable target to increase certainty in drug effects in the preclinical stage.

Aims of the study

A common method used to evaluate treatment efficacy in subcutaneous tumor models is to compare average tumor volume of a treated group with that of a control (untreated) group on the final day of a study. Significant differences between groups are determined using a statistical test, for example a t-test. We hypothesized that larger user measurement variability would result in larger standard deviation of group volume and less consistency in group volumes when repeating a study and would therefore affect the conclusions made in the study and repeats.

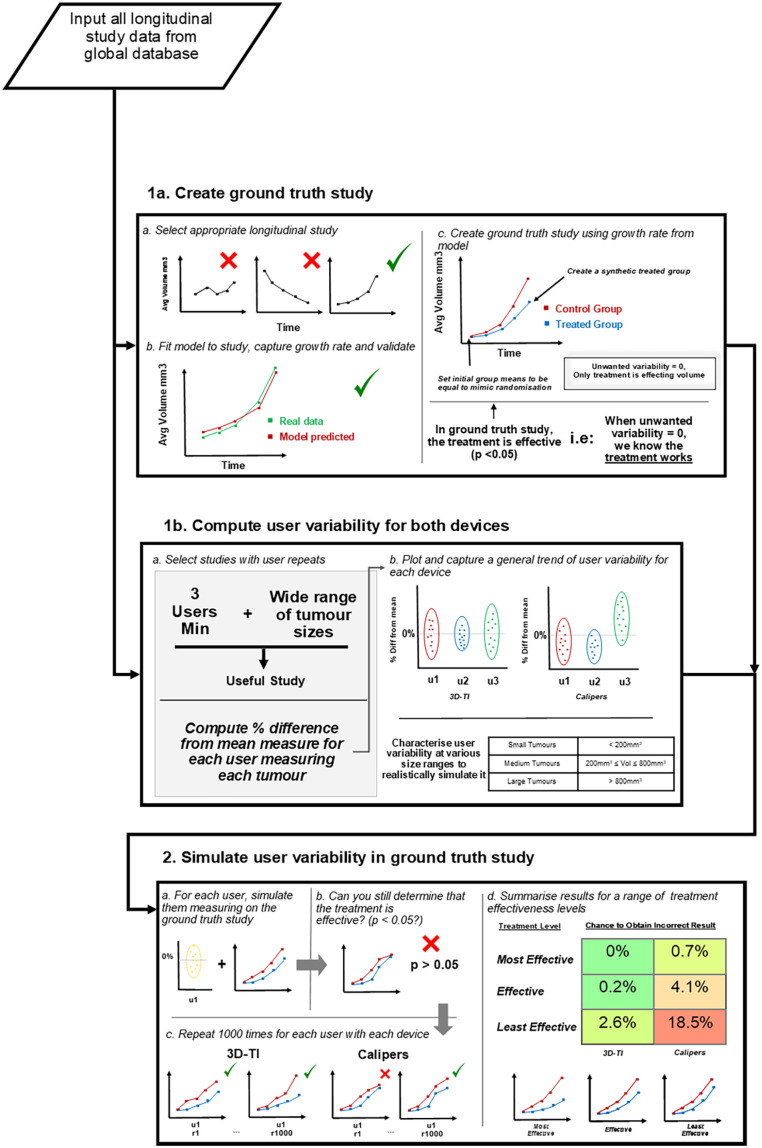

As previously shown, user measurement variability and bias can affect preclinical in vivo tumor studies, from randomization to study outcomes.5,11 In vivo tumor growth data as collected in duplicate by multiple investigators were used as a start point for this investigation in order to investigate how user measurement variability affects study endpoints in more detail. Mathematical modeling was chosen to create a controlled efficacy study scenario in which the only variation in study outcome was produced by the user variability applied to the model. In a typical in vivo study, other sources of variation including differences between individual rodents, and laboratory conditions could also affect the outcome, so this method allowed us to isolate the effects of user measurement variation on the study outcomes with confidence.

Methods

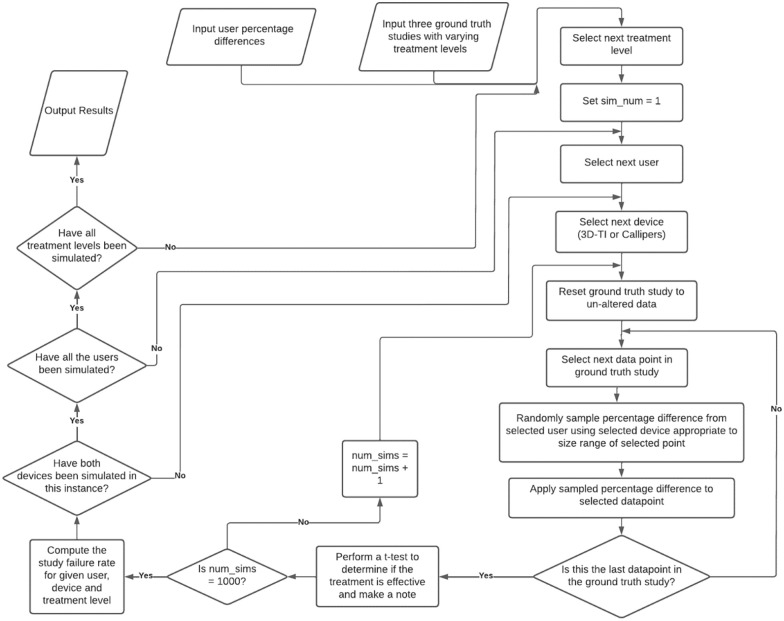

Determining if inter-operator variability can cause false study results is challenging as the true outcome of a study must first be known in order to determine the rate of false results. A true study outcome is near impossible to determine with certainty using in vivo data due to unwanted sources of variability; intrinsic rodent variability as well as inter-operator variability can impact tumor study outcomes and reproducibility of results. Furthermore, in vivo resources are limited, often leading to small group sizes and underpowered experiments. Sources of variability and poor study design are the key contributors to poor in vivo study reproducibility.12 Simulating studies mathematically (in silico) allows complete isolation of effects that can be attributed to a single variable of interest; user measurement in this case. An in silico study was modeled on real in vivo efficacy study data to exclude other unwanted sources of variability. This in silico study contained a control group and a single treatment group with the only difference in the group volume averages being due to the treatment effect alone, giving a model study with a known outcome in which the treatment being assessed was effective, necessary to determine the false negative rate. This in silico study is referred to as the “Ground truth study.” The impact of inter-operator variability on false study results could then be assessed via simulation, different users were simulated measuring throughout the same in silico study. If the treatment was deemed ineffective then a false result was recorded. To accurately simulate user measurements, user measurement characteristics were first defined for each measurement device. These characteristics came from in vivo data spanning 15 users and 9 longitudinal studies. Having 15 users measure on a single study in vivo would be impossible due to mouse handling restrictions, therefore an in silico study provides greater confidence in experimental outcomes. An overview of this entire process is shown in Figure 1. The application of a large dataset of real in vivo user measurements to in silico data to simulate user measurement has not been done before. We believe our data set of user repeated tumor measurements to be the largest in the world and allows us to offer a deeper insight into the impact of inter-operator variability. Comprehensive datasets comparing measurement variability of 5 or more users are extremely rare in this field and few organizations have the capacity, resources, or motivation to collect or analyze such data, especially as the results highlight issues with widely used calipers. This analysis is a natural follow up to a previous work highlighting the difference in inter-operator variability between calipers and 3D-TI,5 where we have taken the conclusions from that paper and investigated how the variability we identified would affect real-world efficacy study outcomes.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the analysis process.

Tumor measurement devices

Two tumor measurement methods were used to collect data to compare the effects of user measurement variability; calipers and the BioVolume 3D and thermal imaging (3D-TI) device. 3D-TI utilizes a proprietary combination of thermal imaging, and stereo RGB photographic images to develop a 3D tumor model using mapping and stereo process reconstruction. This model is then segmented automatically via a machine learning algorithm designed to detect the boundary of the tumor, another algorithm is used which then measures the longest length and width without user bias. Tumor volume is then calculated automatically.113D-TI also creates a digital record with relevant metadata, allowing for data to be shared with ease and leaving an audit trail for data traceability. Here, calipers were used in the standard way; users chose the longest tumor length and its perpendicular width by eye, and measured along these axes by placing caliper blades around the tumor. This method has several sources of user variation including compression of the tumor between the caliper blades, and determining the longest length and width by eye which is especially a problem for complex and non-spherical tumors.

3D-TI significantly reduces user measurement variability in comparison to calipers,5 so was also used to collect repeats of tumor measurements. Stereoscopic RGB and thermal images were captured and converted into 3D tumor models using the BioVolume 3D-TI device and software. BioVolume’s 3D-TI measurement algorithm then determined the tumor’s length and width from the 3D model using the same automatic method every time. Further details on measurement technique, the BioVolume system, and how scans were processed are available in our previous paper.11

Tumor volume was calculated from length and width in the same way for both devices, using the formula20:

In vivo data collection

The 3D-TI device and system (BioVolume) were used by 27 client organizations with training and support from Fuel3D. Studies were designed to compare variability of caliper measurements to the 3D-TI device. All animal care, lab work, caliper measurements, and image scans were carried out by scientists in client organizations according to their own animal handling and ethics protocols. Data including tumor dimensions, user, date and rodent ID were shared with Fuel3D to use in an aggregated and anonymized way, forming the “global dataset.” Client companies and scientists did not have financial interests in BioVolume.

Appropriate in vivo longitudinal studies from this global dataset of 3D-TI measurements were selected as described in the following “ground truth” modeling and “computing user variability” sections.

Creating the ground truth study

In vivo data processing

To create representative synthetic study data in which unwanted variability is equal to zero, a template growth curve for users to “measure” was established (Figure 1, Box 1a). A tumor growth study where growth was measured using 3D-TI and calipers at 7 points across a 16 day period was used to model the template tumor growth curves. 3D-TI measurements had the lowest inter-operator variability (assessed by coefficient of variation, 0.181 vs 0.238, P = .026, Wilcoxon–signed rank test) so were used for modeling. Repeat measurements enabled estimation of stable means when fitting the model.

Fitting the model

Modeling synthetic data allowed removal of unwanted sources of variability. Any difference in average treatment between groups could then be confirmed to be from treatment.

A generalized linear model was fit to the study data using R and the lme4 package (v1.1). The model consisted of:

A fixed group slope by day to estimate the growth rate of the group

A fixed rodent intercept, to account for varying initial rodent volumes.

Combining the above gives us the model formula:

where day represents the day since first measurement. A generalized linear model was fit using a log link function and a gamma family to account for exponential tumor growth, and heteroskedastic growth within groups. The growth rate obtained from the day: group term in the model was 0.236 log units, or a daily increase in growth rate of exp(0.236) = 1.26.

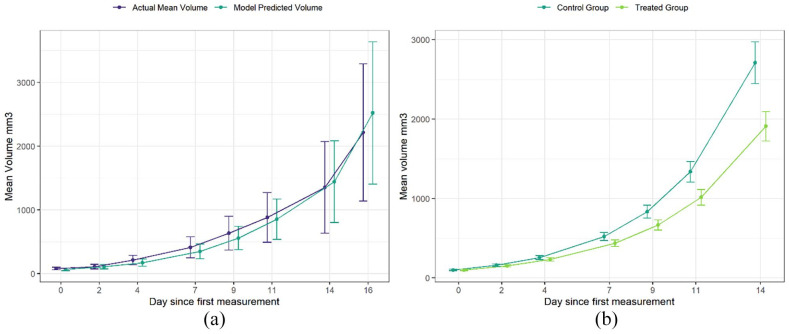

To validate the model and confirm that the group growth rate obtained by the model accurately represented the in vivo study data, average group growth curves were plotted for both the in vivo study, and modeled study (Figure 2a). The growth curves were closely aligned, with overlapping CIs, indicating that the model represented the study data well, confirming that the growth rate of the control group was captured successfully.

Figure 2.

(a) Comparison of study average tumor volume against model predicted average volumes. Model used to predict rodent volumes averaged across the 5 users. Error bars are 95% CIs. (b) Average tumor growth of representative synthetic study data. Using the growth rate obtained from the model, synthetic study data was created in which a treatment was evaluated and initial group volumes across the groups were equal. This is referred to as the “ground truth study” and was the basis for which the impact of user variability was investigated. Error bars are 95% CIs.

Using the growth rate obtained from the model, synthetic study data were created. Synthetic study data with unwanted sources of variability removed was essential to be confident in the conclusions made. The data were created with the following changes to the original study:

A treated group was added which the same growth rate as the control group minus a set value. This value was then varied to adjust the growth rate, creating different treatment effectiveness levels.

Eight rodents were created in each group and tumor volumes were initially identical across the 2 groups. This was to replicate the effects of randomization where initial group volumes are equal and any difference in group volume after treatment can be attributed to treatment alone. Initial rodent tumor volumes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initial rodent volumes for both groups in the synthetic study.

| Rodent name | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial tumor volume (mm³) | 80 | 85.7 | 91.4 | 97.1 | 102.9 | 108.6 | 114.3 | 120 |

After establishing the initial conditions, the model was used to simulate the growth of these rodents in both groups for the 7 measurement sessions across 14 days (Figure 2b). These synthetic study data will be referred to as the ground truth study.

Creating different treatment scenarios

To investigate the impact of inter-operator variability at different treatment levels, 3 separate ground truth studies were created, each with a different growth rate in the treated group to represent different treatment strengths or dosages. The treated group growth rate was defined as a constant and subtracted from the control group growth rate:

Most effective treatment scenario = 0.236 - 0.03

Effective treatment = 0.236 - 0.025

Least effective = 0.236 - 0.02

On the final day this resulted in the following group mean difference (control group mean tumour volume – treated group mean tumour volume) and standard errors:

Most effective treatment scenario: Mean group difference = 950 mm3

Effective treatment: Mean group difference = 800 mm3

Least effective: Mean group difference = 650 mm3

Both the control and treated groups in each scenario had a standard error ~120 mm3.

A t-test was performed on the final day to determine if there was a significant difference between average group volumes in the ground truth study. In all 3 of these scenarios (where unwanted variability was equal to zero), the treatment group was statistically different to the control group (Table 2). To investigate the impact of inter-operator variability on the outcome of a study, user variability was then introduced to the ground truth study data to determine how this variability affected the ability to statistically separate the 2 groups.

Table 2.

Results of t-test comparing final day group volumes in each of the 3 ground truth studies.

Defining user variability

In vivo data processing

Percentage difference from the mean (PDFM) for a given tumour with repeated measures from different users was used to quantify how users measure in relation to each other. The PDFM was modified to exclude a user’s own measurements, so that users were not compared to themselves. PDFM is a relative measure affected by tumor size so to accurately simulate user variation throughout a longitudinal study, PDFM was assessed for a range of tumor sizes. Therefore, only longitudinal studies that captured the entire tumor life cycle (from palpable to welfare endpoint) and that had at least 3 users taking repeat measurement were included. Nine studies in our global dataset met these criteria, summarized in Table 3. Table 3 can provide insight on the most variable users and if they measure in the same study, it also shows that the number of users per study is balanced, between 3 and 5.

Table 3.

Study data used to compute PDFM and users which measured in the studies.

| Study | Users |

|---|---|

| Study 1 | u01, u02, u03 |

| Study 2 | u01, u02, u06 |

| Study 3 | u04, u05, u07 |

| Study 4 | u08, u09, u10, u11, u12 |

| Study 5 | u08, u09, u10, u11, u12 |

| Study 6 | u08, u09, u10, u11, u12 |

| Study 7 | u13, u14, u15 |

| Study 8 | u13, u14, u15 |

| Study 9 | u13, u14, u15 |

PDFM was calculated for each user with each measurement device and across 3 size ranges:

Small tumors: ⩽200 mm³

Medium tumors: between 200 and 800 mm³

Large Tumors: ⩾800 mm³

These bounds were chosen to maximize the number of datapoints across the size ranges whilst still being somewhat representative. Table 4 details the number of data points included in each size range, a data point is 1 tumor measurement per user, per mouse, per timepoint across the studies in Table 3. To remove outliers, 5% of the largest and smallest PDFMs were excluded for each user, measurement device and tumor size range. 3463 tumor measurements were included in total using the 3D-TI and 3456 tumor measurements using calipers.

Table 4.

Number of data points for the various size ranges for both 3D-TI and calipers. T.V = Tumor Volume.

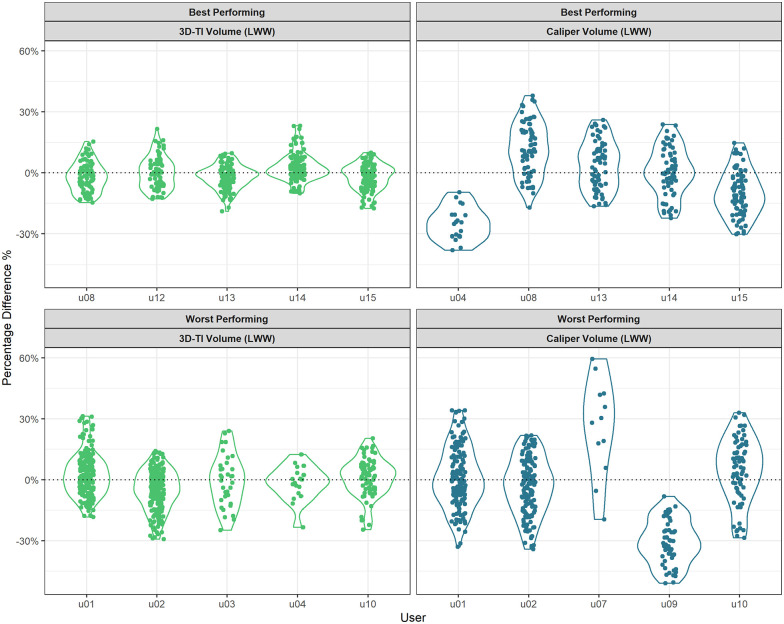

Capturing characteristics of users for 3D-TI and calipers

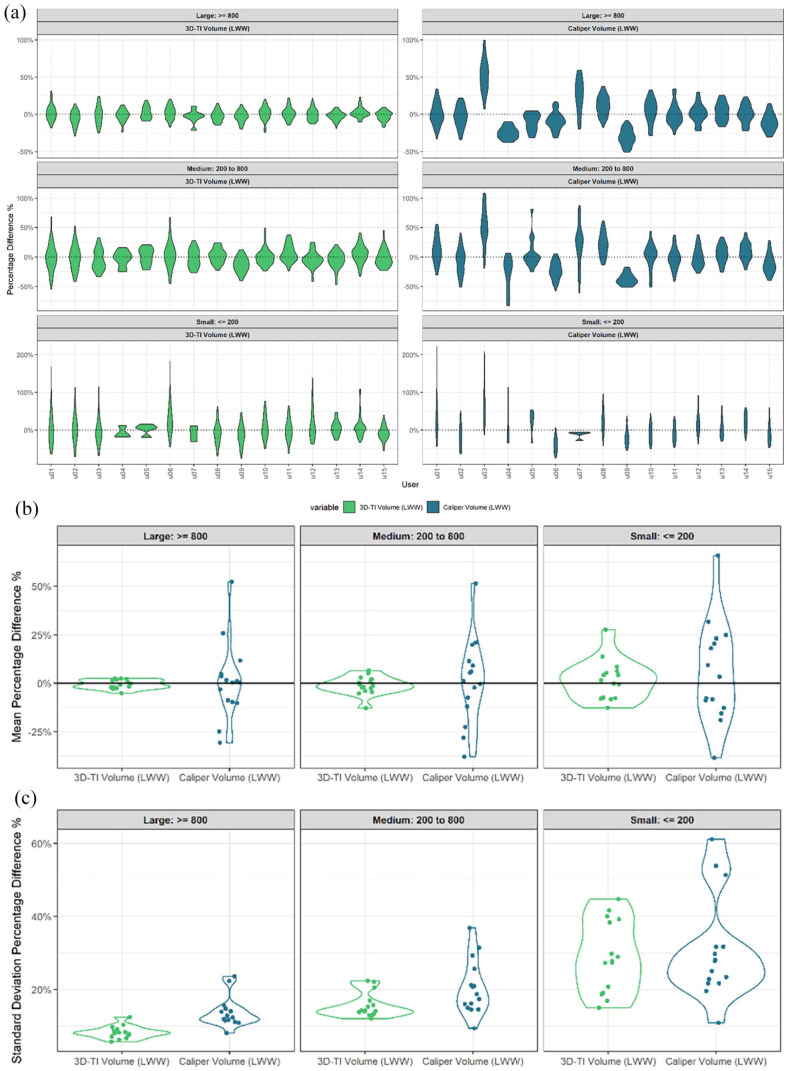

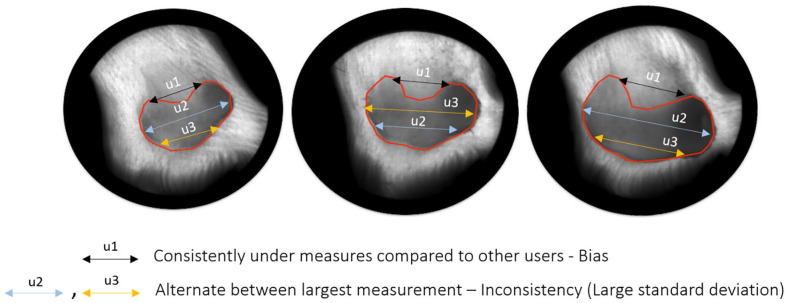

PDFM was used to establish whether a user had a particular bias when compared to other users, for example, User 03 had a mean PDFM of ~50% for large tumors with calipers and as such typically measured 50% larger than the average of the other users’ measures in the same study (Figure 3a). Consistency of said biases relative to the other users in the same study is also an important factor to consider and was assessed using the standard deviation of PDFM. 3D-TI users were less biased than caliper users for all size ranges when assessed by the mean (Figure 3b). Users were also more consistent in their biases when using 3D-TI as opposed to calipers when looking at the standard deviation for large and medium size tumors (Figure 3c, P = 8.3 × 10−5 and P = 1.6 × 10−2 respectively, t-test). Figure 4 shows examples of user measurement bias as well as inconsistency of bias.

Figure 3.

(a) Percentage difference from the mean (PDFM) for all users. Shown as a violin plot, users taken from valid longitudinal studies for 3D-TI (Left) and calipers (right) for a range of tumors sizes. (b) Mean of PDFM of each user. Violin plot represents average of each user’s measurement distribution, split by tumor size range. (c) Standard deviation of PDFM of each user. Violin plot represents standard deviation of each user’s measurement distribution, split by tumor size range.

Figure 4.

Diagram illustrating user bias (user 1) and inconsistency of bias compared with other users (users 2 and 3).

Simulating user measurement in the ground truth study

After generating both the ground truth study data and characterizing user variability for both 3D-TI and caliper users, the 2 were then combined to investigate the impact of inter-operator variability on study outcome (Figure 1, box 2).

The ground truth study data were categorized according to tumor volume using the same ranges (Figure 3). An iterative process was then run in which 1 of the 15 users was selected and their percentage differences were applied to the ground truth study data at the appropriate size range. This was simply done by selecting a datapoint in the ground truth study, randomly sampling one of the percentage differences within the same tumor size category and multiplying them together, essentially “reverting” back from a mean measurement as generated by the model to the individual user measurement. This was repeated for every data point in the ground truth study, for both the generated 3D-TI and caliper percentage differences. The synthetic study data was then determined to have been “measured” by the selected user. A t-test was then performed on the final day to determine if there was a significant difference in average volume between both groups. This process of synthetic measurement across the ground truth study and analysis was repeated for each user 1000 times (for 3D-TI and caliper measurements), as for a given datapoint many possible PDFMs could be sampled resulting in different outcomes. Performing 1000 repeats reduces effects of outliers due to sampling and creates a stable mean result. An incorrect result rate was computed as the number of times the control and treatment groups could not be statistically separated divided by 1000 for each user and each device.

The above simulation was performed for each of the 3 treatment scenarios. The study failure rate was then averaged across all 15 users, split across 3D-TI, calipers, and the 3 treatment levels (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flow chart detailing the simulation algorithm.

Results

An existing longitudinal in vivo study was used to create synthetic tumor growth curve data for a range of treatment scenarios as detailed in Methods. Inter-operator measurement variability was then computed for both 3D-TI and calipers and applied to the synthetic growth curves to generate user measurements in silico. These data were then analyzed in order to investigate the effect of user variability on study endpoint.

For a range of treatment scenarios, 3D-TI consistently reduced the chance of getting an incorrect result in an efficacy study (Table 5). Failing to detect a significant difference between group means on the final study day was classed as an incorrect result (false negative). For the most effective scenario where the difference in mean group volumes between control and treated groups was 950 mm3 before applying user variability, the treatment was deemed effective for all 3D-TI users and their 1000 measurement repeats. When using calipers in the same treatment scenario, an incorrect result (false negative) was obtained 0.7% of the time. When decreasing the effectiveness of the treatment, inter-operator variability had an increasing impact on endpoint results. The chance of getting an incorrect result for calipers in the “effective” scenario was 4.1%. For 3D-TI measurements, an incorrect result was only obtained in 0.2% of cases. Finally for the scenario in which the treatment is the least effective of the 3, caliper measurements obtained an incorrect result in almost 20% of cases. For 3D-TI, even in the least effective treatment scenario an incorrect result was only obtained in 2.6% of cases.

Table 5.

Probability of incorrectly determining an effective treatment to be ineffective due to user variability for 3D-TI and calipers. Using a combination of simulation and modeling, 15 users “measured” on a study using both 3D-TI and calipers in which the treatment was known to be effective, this process was repeated 1000 times for each user. Probability of not detecting a difference between group means was computed for each user then averaged across all users for a given device. Volumes in brackets is the mean group difference for the respective treatment scenario. Each cell is coloured using a gradient in which the lowest probability of a false negative result is green, and the highest probability is red.

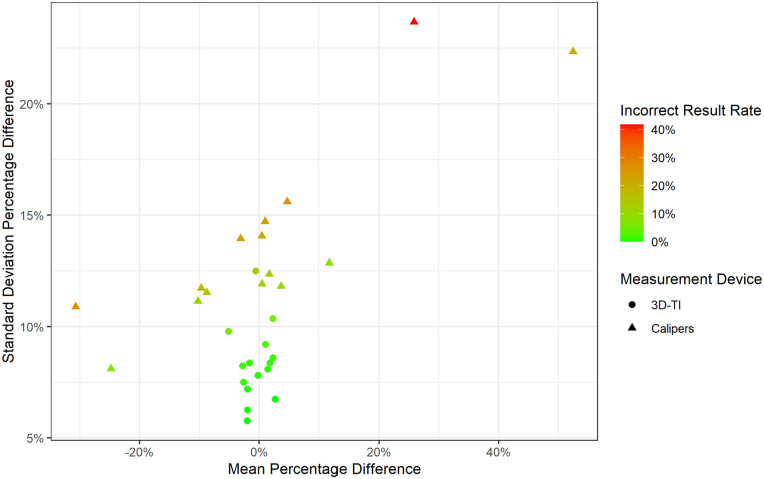

Figure 6 highlights the difference in characteristics between the 5 users with the lowest incorrect result rate and the 5 highest users. Users that measured less consistently when compared with other users and therefore had larger standard deviation in PDFM, were more likely to obtain an incorrect result. Users with mean PDFMs centered about zero were also likely to produce an incorrect result as both positive and negative PDFMs created more overlaps in the group measurements.

Figure 6.

Percentage difference from the mean (PDFM) for large tumors. Data plotted as violin plots for the 5 users with the lowest (top) and highest (bottom) incorrect result rates for 3D-TI (left) and calipers (right).

The impact of mean PDFM and the standard deviation of PDFM on incorrect result rate was then investigated further, taking into account all users, for 3D-TI and calipers (Figure 7). Users with larger standard deviations had a higher chance of obtaining an incorrect result, and caliper users tended to have larger standard deviations. As the standard deviation of PDFM increased, users who did not over measure were more likely to obtain an incorrect result in this scenario. The best user is one who has little to no bias (mean of 0) and is highly consistent compared to other users (small standard deviation).

Figure 7.

Standard deviation versus mean of PDFM. Mean and standard deviation PDFM colored by incorrect result rate for all users using 3D-TI and calipers. Data for large tumors only.

Discussion

Preclinical study irreproducibility stems from many causes, of which user measurement variability has been shown to be a significant problem when taking tumor measurements using calipers.2-5 Gathering repeat measurements (either inter- or intra-operator) is time consuming and increases welfare concerns due to increased animal handling, so for this study, real in vivo data was applied to a synthetic model study. Working in silico also allowed exclusion of all other sources of in vivo variability such as differences in group means at randomization. Thus, user variability was isolated and was the sole cause of any change in study outcome.

PDFM outliers were excluded from the model to better generalize PDFM for each user, however this method slightly underestimates the true impact of user variability on study outcome. We predict that including outliers would further increase the chance of false results from the values reported here. On the other hand, sampling percentage difference randomly from one user, and resampling in a study repeat may overestimate variation in comparison to real-life measurement; it is unlikely that one user would repeat a measurement and record a greatly different result when resampling.

Interestingly, a user who over measures relative to other users is less at risk at detecting a false negative than a user which under measures or measures consistently with other users, as shown by the effect of mean PDFM on the incorrect result rate. The reason for this is large positive percentage differences creates a larger distance in group means than negative similar sized percentage differences. The inverse would be true with a scenario with a treatment that was not effective and false positive rate were to be investigated.

This study is a starting point for further investigations into the effects of measurement variability on study endpoints and outcomes. Greater understanding of these effects will help us to understand and minimize problems in study reproducibility and to accurately characterize drug effects at an early stage with confidence. We have shown here that reducing measurement variability reduces false negative rate which has been identified as an essential variable to control to achieve cost-savings in clinical trials using the “quick win, fast fail” model,19 without mistakenly excluding effective drugs from further development.

Next, investigating the impact of inter-operator variability study on false positive rate should be reported to get a full understanding of overall false result rates. Secondly, a wider range of different treatment evaluation scenarios could be investigated, including regression studies, and impact on other efficacy measures such as survival curves, and other statistical tests such as a repeated measures ANOVA. More in-depth analysis to determine the effects of cell line on inter-operator variability would also enhance understanding of specific treatment scenarios and possibly allow for more realistic tumor measurment simulation.

Calipers are by far the cheapest tumor measurement tool used universally by researchers and animal technicians working in the oncology field. Hesitancy to change a long-established and ubiquitous technique, as well as additional welfare considerations (anesthesia requirement) are barriers to wider adoption of alternative imaging techniques. High start-up costs are another factor, but one that could be offset over time by new technologies that increase throughput by automating data collection and entry, and which have the potential to reduce group sizes and study length by offering more accurate and precise data.

In conclusion we showed that by using a 3D and thermal imaging device to reduce user measurement variability in comparison to calipers, the chance of a false efficacy study result was also decreased. This translates to missing a treatment effect in an efficacy study, and wrongfully excluding a viable drug candidate from further development. The inverse is also possible; a false positive result also has the potential to be a costly mistake if an ineffective drug moves forward in the development cycle for more rounds of testing. Resources and time would be wasted trying and eventually failing to replicate the false positive result. Later-stage clinical trials are expensive and time consuming to run, therefore incorrect or ambiguous results should be reduced as early on in development as possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank and gratefully acknowledge the contribution of all the scientists who ran studies and collected the measurement data which was analyzed in this report. We also thank Adam Sardar for his guidance and discussion of the modeling methods.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Fuel3D provided support in the form of salaries for authors, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. In vivo work was carried out by BioVolume users who were not employed by Fuel3D and who did not receive financial compensation.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Fuel3D is developing BioVolume and claims financial competing interests on the product. There are specific patents granted and filed for this technology or any part of it. Fuel3D provided support in the form of salaries for authors, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. In vivo work was carried out by BioVolume users who were not employed by Fuel3D and who did not receive financial compensation.

Author Contributions: Jake T Murkin performed the analysis and wrote the Methods, Results and Discussion. Hope E Amos wrote the Introduction, Abstract and Discussion as well as provided scientific insight into the analysis process. Daniel W Brough proof read, performed corrections and offered insight into the analysis process. Karl D Turley framed the initial hypothesis and provided feedback throughout the analysis and writing of the results.

References

- 1. Euhus DM, Hudd C, LaRegina MC, Johnson FE. Tumor measurement in the nude mouse. J Surg Oncol. 1986;31:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ni J, Bongers A, Chamoli U, Bucci J, Graham P, Li Y. In vivo 3D MRI measurement of tumour volume in an orthotopic mouse model of prostate cancer. Cancer Control. 2019;26. doi: 10.1177/1073274819846590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jensen MM, Jørgensen JT, Binderup T, Kjaer A. Tumor volume in subcutaneous mouse xenografts measured by microCT is more accurate and reproducible than determined by 18F-FDG-micropet or external caliper. BMC Med Imaging. 2008;8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hall C, von Grabowiecki Y, Pearce SP, Dive C, Bagley S, Muller PAJ. iRFP (near-infrared fluorescent protein) imaging of subcutaneous and deep tissue tumours in mice highlights differences between imaging platforms. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brough D, Smith A, Turley K, Amos H, Murkin J. Reducing inter-operator variability when measuring subcutaneous tumours in mice: an investigation into the effect of inter-operator variability when using callipers or a novel 3D and thermal measurement system. MetaArXiv Preprint. Posted online October 8, 2021. doi: 10.31222/osf.io/hvfpx [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ayers GD, McKinley ET, Zhao P, et al. Volume of preclinical xenograft tumors is more accurately assessed by ultrasound imaging than manual caliper measurements. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:891-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ranganathan B, Milovancev M, Leeper H, Townsend KL, Bracha S, Curran K. Inter- and intra-rater reliability and agreement in determining subcutaneous tumour margins in dogs. Vet Comp Oncol. 2018;16:392-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoon JH, Yoon SH, Hahn S. Development of an algorithm for evaluating the impact of measurement variability on response categorization in oncology trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heye T, Merkle EM, Reiner CS, et al. Reproducibility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging part II. Comparison of intra- and interobserver variability with manual region of interest placement versus semiautomatic lesion segmentation and histogram analysis. Radiology. 2013;266:812-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zerouaoui H, Idri A. Reviewing Machine Learning and image processing based decision-making systems for breast cancer imaging. J Med Syst. 2021;45:8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delgado San Martin J, Ehrhardt B, Paczkowski M, et al. An innovative non-invasive technique for subcutaneous tumour measurements. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483:531-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Henderson VC, Kimmelman J, Fergusson D, Grimshaw JM, Hackam DG. Threats to validity in the design and conduct of preclinical efficacy studies: a systematic review of guidelines for in vivo animal experiments. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kenakin T, Bylund DB, Toews ML, Mullane K, Winquist RJ, Williams M. Replicated, replicable and relevant-target engagement and pharmacological experimentation in the 21st century. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;87:64-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lazic SE, Essioux L. Improving basic and translational science by accounting for litter-to-litter variation in animal models. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simeon-Dubach D, Burt AD, Hall PA. Quality really matters: the need to improve specimen quality in biomedical research. J Pathol. 2012;228:431-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vaughan L, Glänzel W, Korch C, Capes-Davis A. Widespread use of misidentified cell line KB (HeLa): incorrect attribution and its impact revealed through mining the scientific literature. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2784-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moreno L, Pearson AD. How can attrition rates be reduced in cancer drug discovery? Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2013;8:363-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, et al. How to improve RD productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:203-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomayko MM, Reynolds CP. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24:148-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]