Abstract

Background

CD47 is a widely expressed transmembrane glycoprotein that delivers an antiphagocytic signal on macrophages through its interaction with SIRPα. CD47 is highly expressed in cancer cells and its overexpression is correlated with poor prognosis. CD47 blocking antibodies are actively being developed worldwide for cancer therapy, and the most challenging concern is associated with hematotoxicity. Ligufalimab (AK117) is a novel humanized IgG4 anti-CD47 antibody without hemagglutination effect. Blockade of CD47-SIRPα pathway by AK117 leads to a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment with unique safety features.

Methods

AK117 was discovered through a screening hierarchy excluding hemagglutination. AK117 was characterized by detecting CD47-SIRPα blocking potential. Its effect on human red blood cells was examined and the mechanism of its binding with erythrocytes was studied. The abilities of AK117 and its combination with various opsonizing antibodies to promote macrophage-dependent phagocytosis of multiple human tumor cells were determined using fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. In vivo, the antitumor efficacy of AK117 monotherapy and combination with AK112 (an anti-PD-1/VEGF-A bispecific antibody) was assessed in a variety of xenograft models. Toxicologic studies were evaluated in non-human primates.

Results

AK117 bound to CD47 with high affinity and blocked the CD47-SIRPα interaction. AK117 did not induce hemagglutination and showed significantly lower degree of erythrophagocytosis compared with Hu5F9-G4, and this mechanism of hemagglutination resistance might be related to the binding conformation. AK117 enhanced macrophage-mediated phagocytosis in both hematologic cancer and solid tumor cell lines as a single agent or in combination with cetuximab and rituximab in vitro, respectively. The antitumor effects of AK117 as a single agent or in combination with AK112 were also encouraging in various xenograft models. In non-human primates, AK117 showed less hematotoxicity compared with Hu5F9-G4.

Conclusions

AK117 eliminated hemagglutination and also enabled to maintain full effectiveness of CD47 blockade on tumor cells, which resulted in excellent antitumor efficacy and favorable safety profile of AK117. A series of clinical trials of AK117 as a therapeutic agent in combination with various agents such as AK112 are in progress for the treatment of multiple hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.

Keywords: Antibodies, Neoplasm; Drug Evaluation, Preclinical; Immunotherapy; Phagocytosis

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The main treatment-related adverse events of CD47 blocking antibodies occurred in clinical trials are the hematotoxicities, especially hemagglutination and anemia, which limit the clinical application of those antagonists, thus, we have developed ligufalimab as a second generation of anti-CD47 antibody without inducing hemagglutination.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

AK117 is a novel anti-CD47 antibody with no hemagglutination, and the mechanism of resistance to hemagglutination is correlated with the unique conformation of AK117/CD47 complex. AK117 is more likely to bind CD47 on one red blood cell (RBC), while Hu5F9-G4 is likely to bind CD47 on two separate RBCs, consequently leading to hemagglutination. Additionally, co-blockade of CD47, PD-1 and VEGF by AK117 and AK112 (an anti-PD-1/VEGF-A bispecific antibody) exerts the excellent antitumor effect in xenograft model of triple-negative breast cancer.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Ligufalimab as an immunotherapeutic agent in combination with various agents potentially shapes a promising therapeutic strategy for multiple human cancers.

Background

During the process of tumorigenesis and development, tumors continue to evolve and may escape tumor immune surveillance and inhibit antitumor immune response through various mechanisms. One of the main mechanisms of tumor immune escape is the employment of immune checkpoint pathway.1 2 Over the past decades, immunotherapy has shown remarkable clinical efficacy in cancer treatment, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4, programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and programmed death ligand-1 for multiple cancer types, which act on the adaptive immune system.3–7 Macrophages are professional phagocytes of innate immune system and widely distributed in our body tissues. They engulf tumor cells through phagocytosis, which is regulated by pro-phagocytic and antiphagocytic signals. However, the function of macrophages is inhibited by one of the phagocytosis immune checkpoints which is the CD47‐SIRPα pathway.8 Currently, adaptive ICIs in combination with innate ICIs have emerged as a novel anticancer strategy through corroborated action of phagocytosis, natural cytotoxicity and T cell-mediated cytotoxicity.9

CD47 is a transmembrane protein, widely expressed on essentially all human cell types and overexpressed broadly across tumor types. The overexpression of CD47 is correlated with poor prognosis in patients with cancer.10 11 CD47 functions as a macrophage immune checkpoint by suppressing activity of phagocytes through its interactions with SIRPα on phagocytic cells, which gives a ‘don’t eat me’ signal to the innate immune system as a mechanism of immune escape.8 12 The increasing number of studies has focused on anti-CD47 immunotherapy in recent years and it has been reported that tumor growth and metastasis can be inhibited significantly by blocking the CD47-SIRPα interaction.13 Blockade of the CD47-SIRPα interaction effectively promotes the phagocytosis of tumor cells by phagocytes such as macrophages, and induces proceeding and cross-presentation of tumor antigens to T cells by antigen presenting cells, which results in activation of adaptive immune response.14–16 In addition, the blockade of CD47 also facilitates the recruitment of additional immune cells to tumors for synergizing the innate and adaptive immune response.14 15 17 However, the CD47-SIRPα axis can influence the maintenance of erythrocytes, platelets and hematopoietic stem cells.18 SIRPα is barely detectable in red blood cells (RBCs) or in T or B lymphocytes, whereas CD47 is ubiquitously expressed on a variety of human cells including RBCs and platelets.10 18 19 Therefore, the blockade of CD47 by anti-CD47 antibody enables to induce cell-mediated cytotoxicity which leads to severe on-target off-tumor toxicity effects, including RBC hemagglutination, anemia, and platelet aggregation.20 21

In the past few years, there have been more than 20 CD47-related therapeutic agents in over 40 clinical studies for the treatment of multiple hematological malignancies and solid tumors worldwide. A few failed clinical studies cast shadows over the development of CD47 agents.22 The main issues were lack of efficacy for monotherapy, and the occurrence of anemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia.23 24 In 2018, a phase I dose-escalation clinical study of CC-90002 in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes was terminated due to the lack of monotherapy activity and evidence of anti-drug antibodies.25 Although the phase 1b clinical study of magrolimab (Hu5F9-G4) in combination with azacitidine showed positive results in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in 2019, a ‘priming dose’ strategy was still required to improve the issue of anemia.26 Therefore, it is imperative to develop a next generation of anti-CD47 antibody to overcome the aforementioned issues and further improve the safety and therapeutic efficacy.

To enhance the tolerance of the anti-CD47 antibody, regulate the pathophysiological functions mediated by CD47-SIRPα signaling, and retain the antitumor efficacy, we have developed a second generation of anti-CD47 antibody ligufalimab. Ligufalimab, also known as AK117, is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody with a unique structure. Ligufalimab could effectively eliminate RBC hemagglutination and anemia, and induce robust macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of cancer cells, and improve the antitumor efficacy without the requirement of a lower ‘priming’ dose to prevent anemia.

Methods

Antibodies and cells

6F7, the murine clone and parental version of AK117, was first screened through hemagglutination on human RBCs. Hu5F9-G4 (anti-CD47 antibody by Forty Seven and Gilead)20 and cetuximab (anti-EGFR antibody)27 were produced in-house according to published sequences. Anti-HEL antibody with IgG1 or IgG4 Fc were used as isotype control antibody (Akeso Biopharma). Rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody, Roche, Cat. H0277) was purchased from Roche. Both AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 were also produced in the following versions: intact antibody with IgG1 mutation Fc, monovalent with IgG4 Fc, F(ab)2. Human tumor cell lines (Jurkat, Raji, Ramos and HT-29 were purchased from the Cell Resource Center, Shanghai Institutes of Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences. MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection.

Antibody affinity determination by surface plasmon resonance

The affinity of antibodies to the extracellular domain (ECD) of human CD47 was determined via surface plasmon resonance (SPR) on a Biacore T200 system. CM5 chip coated with human CD47-his protein was dipped into various concentrations of AK117 (from 0.78 nM to 25 nM with twofold serial dilution). The process of molecular binding (time 120s) and dissociation (time 300s) was recorded using Biacore control software V.2.0. The kinetics and affinity data were analyzed with a 1:1 model using Biacore T200 Evaluation V.2.0.

Binding activity to CD47

Binding activity of AK117 to recombinant CD47 protein was determined by ELISA, and evaluation of AK117 binding on Jurkat or Raji cells was performed by flow cytometry. The details are available in the online supplemental methods.

jitc-2022-005517supp001.pdf (114.3KB, pdf)

Blockade of SIRPα to CD47

The ability of AK117 to disrupt recombinant SIRPα binding to CD47 was evaluated using competitive ELISA, and its ability to block the binding of SIRPα to CD47 expressed on tumor cells was determined by competitive flow cytometry. The details are available in the online supplemental methods.

Species cross binding activity

96-well plates were coated with CD47 protein of cynomolgus monkey, mouse and rat. The cross binding activities were detected using same procedure with binding activity by ELISA.

In vitro safety detection on RBCs

Human RBCs isolated from healthy donors (Zhongshan Blood Center) were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for three times. For hemagglutination, human RBCs were 1:300 diluted in PBS and added into a 96-well plate. Gradient concentrations of AK117 (G4, G1m and F(ab)2) were mixed with RBCs completely and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. HIgG4 and T500 were used as isotype antibody control and positive control.

For binding with RBCs, gradient concentrations of AK117 were incubated with RBCs at 37°C for 40 min, cells were washed and incubated with allophycocyanin (APC) labeled mouse antihuman IgG Fc secondary antibody, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were analyzed using an BD FACSCalibur or Beckman cytometer analysis system.

Modeling and docking

Based on the sequence of AK117, the Fab AK117 was constructed using IgFold.28 The Fab Hu5F9-G4 (PDB ID: 5IWL) was modeled using PyMOL29 and IgFold. Protein–protein docking was performed to analyze the potential epitopes on CD47-ECD using docking script.30 The details are available in the online supplemental methods.

CD47-transmembrane domain modeling

The whole-length CD47 was constructed by PDB file (ID: 7MYZ) to build an antibody-antigen structure. The details are available in the online supplemental methods.

Conformational comparison of antibody-antigen complexes

The construction of whole-length IgG4 antibody was prepared using the structural data of PDB: 5DK3 as the frame structure. The antigen part in Fab-antigen simulated structure was superposed to IgG4 antibody to present the conformation of the whole antibody binding multiple antigens. The details are available in the online supplemental methods.

In vitro phagocytosis assay

Mouse and human macrophages were differentiated from bone marrow cells and peripheral monocytes for 7 days in vitro in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor, respectively. Raji, Ramos, Jurkat and HT-29 cells stained with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (2 µM) in 100 µL assay buffer (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum) were added in 1.5 mL eppendorf tube and incubated with AK117 alone or combo with rituximab or cetuximab at 37°C for 30 min. Macrophages were added into wells and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Cell mixtures were washed using PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin three times and incubated with APC-labeled goat anti mouse CD11b at 4°C for 40 min, followed three times washing. The pellets were resuspended in 300 µL PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and analyzed for phagocytosis using FACSCalibur. Data were analyzed using Flowjo. The ratio of CFSE+APC+double positive cells to APC+positive cells was recognized as a phagocytosis index.

In vivo xenograft tumor model

Female, 5–7 weeks old SCID/Beige mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (animal quality certificate number: 11400700259196). All mice were bred in house for a week before the experiment.

For xenograft models, mice were inoculated subcutaneously in right flank with 5×106 cells/mouse in 0.1 mL of a 70% Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium/30% Matrigel (BD Biosciences) mixture containing a suspension of tumor cells (Raji or MDA-MB-231). Mice were divided into five groups with seven mice per group. Each group resulted in a mean tumor volume (TV) of 100–120 mm3.

In Raji xenograft model, mice were intravenously injected with 1 mg/kg AK117, 0.1 mg/kg AK117, 1 mg/kg Hu5F9-G4, 0.1 mg/kg Hu5F9-G4 and 1 mg/kg anti-HEL-G4 antibody on the Day 0 (group day), D3, D7, D10, D14 and D17.

In MDA-MB-231 TNBC xenograft model, mice were treated with 0.2 mg/kg and 0.02 mg/kg AK117, 0.2 mg/kg Hu5F9-G4, 0.02 mg/kg Hu5F9-G4 and 0.2 mg/kg anti-HEL-G4 antibody on the Day 0 (group day), D3, D7, D10, D14 and D17.

The in vivo bioactivity of AK117 combo AK112 was also tested in a humanized PD-1 mouse model bearing MDA-MB-231 cells. Mice were inoculated subcutaneously in the right flank with 8×106 MDA-MB-231 tumor cells/mouse. Mice were randomized into four groups of six mice each group with a mean TV of ~120 mm3. 4×106 CD3-acitvated peripheral blood mononuclear cells were intraperitoneally injected into mice for the construction of humanized PD-1 mice model. Mice were treated intraperitoneally with AK117 or AK112 or AK117+AK112 once a week for 4 weeks.

The TVs were measured every 3 days and calculated with 0.52×L×W2 (L for length and W for width). Relative tumor growth inhibition (TGI%) was calculated with equation . Vn0 and Vnt mean TV of mouse with number n on day 0 and day t, respectively. RTVn: relative TV of mouse with number n on day t. Mean RTVvehicle and mean RTVtreat represent mean volume of tumor in vehicle and treat group, respectively.

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Akeso Biopharma. The protocol numbers of Raji, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-231 (AK112+AK117) xenograft models are 20160927–01, 20171020–01 and LAW-2022–001, respectively. The animals received care in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Toxicity study in non-human primates

Single dose toxicity studies were conducted at JOINN(Suzhou) according to a written study protocol and facility standard operating procedures in compliance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee criteria, national legal regulations on animal welfare, and accepted animal welfare standards. Cynomolgus monkeys were intravenously infused with a single dose of AK117 (one female and one male) and Hu5F9-G4 (one female and one male) at 10 mg/kg, following a 28-day observation period. Blood samples were withdrawn twice before the injections and at 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14 and 21 days, following administration for blood counts including hemoglobin and hematocrit.

Statistical analysis

The phagocytosis and mouse tumor data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) and the results were presented as mean±SE. Comparisons were performed using a one-way analysis of variance.

Results

AK117 binding to CD47 and blocking of SIRPα interaction with CD47

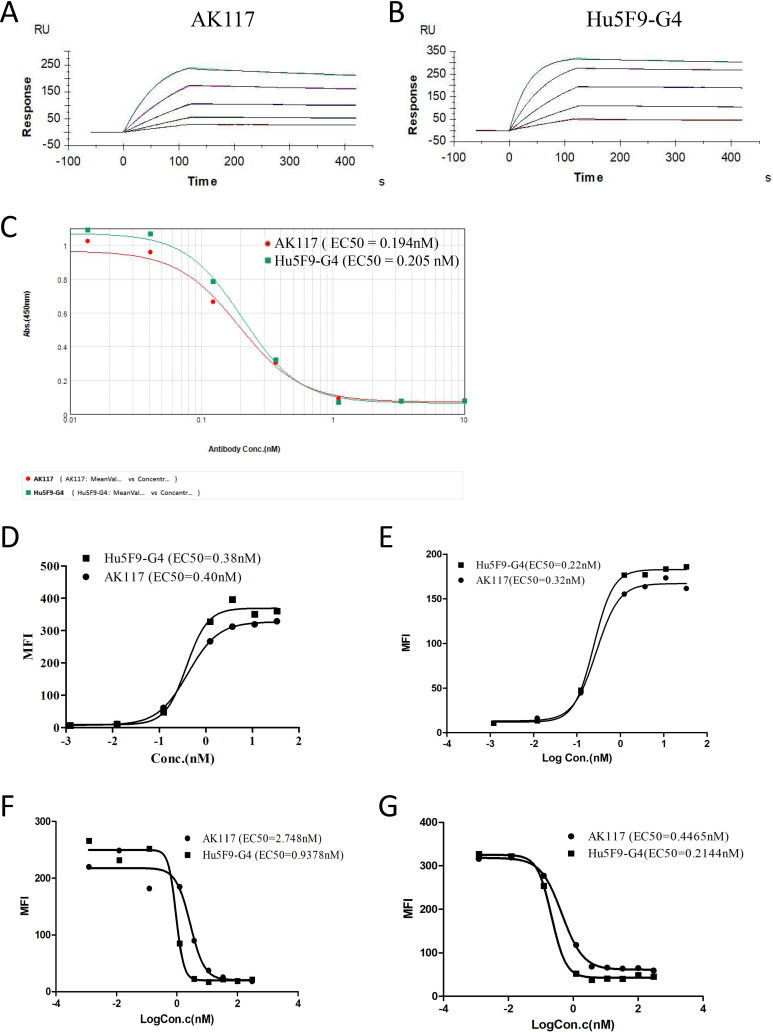

In an effort to identify lead antibody for therapeutic targeting of CD47, we implemented a strategy that included a hemagglutination exclusion step high in the screening hierarchy. A CD47 blocking antibody that did not induce RBC hemagglutination was discovered and later humanized to be named as AK117. Then the specificity and antigen binding affinity of AK117 were detected using ELISA and SPR. The ELISA results showed that AK117 specifically bound to human CD47 antigen with a half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 0.078 nM (online supplemental figure S1). We measured the antigen binding affinity of AK117, which was bound to human CD47 antigen with a KD of 1.52E−10M compared with a KD of 4.42E−11M from Hu5F9-G4 (figure 1A, B; table 1). In order to assess cellular binding activity of AK117, different tumor cells with high endogenous expression of CD47 were tested by flow cytometry. AK117 bound to Jurkat and Raji cells with an EC50 of 0.40 nM and 0.32 nM, respectively (figure 1D, E), and the binding activity of AK117 to CD47 on these cells was comparable to that of Hu5F9-G4. These results indicated that AK117 can specifically bind human CD47 with high affinity.

Figure 1.

AK117 binding and competitive binding to human CD47. (A) and (B) are binding kinetics of AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 to extracellular domain of human CD47 examined by surface plasmon resonance on a Biacore T200 system. Competitive binding of AK117 to recombinant human CD47 with SIRPα by indirect ELISA (C). AK117 binding activity to CD47 expressed on tumor cells (D-Jurkat, E-Raji) and blocking of recombinant SIRPα interaction with CD47 on tumor cells (F-Jurkat, G-Raji) by flow cytometry.

Table 1.

Kinetics data of AK117 to extracellular domain of human CD47

| Antibody | KD (M) | ka (1/Ms) | kd (1/s) | Rmax (RU) |

| AK117 | 1.52E−10 | 2.54E+06 | 3.88E−04 | 253.21–272.60 |

| Hu5F9-G4 | 4.42E−11 | 3.00E+06 | 1.32E−04 | 238.81–327.23 |

jitc-2022-005517supp002.pdf (4.5MB, pdf)

We next examined the ability of AK117 in blocking the interaction between CD47 and SIRPα by ELISA and flow cytometry. AK117 competed with SIRPα-ECD binding to human CD47 with an EC50 of 0.194 nM (figure 1C). AK117 effectively blocked the CD47-SIRPα interaction on the surface of Jurkat and Raji cells with an EC50 of 2.748 nM and 0.4465 nM, respectively, and the blocking activity of AK117 was comparable to that of Hu5F9-G4 (figure 1F, G).

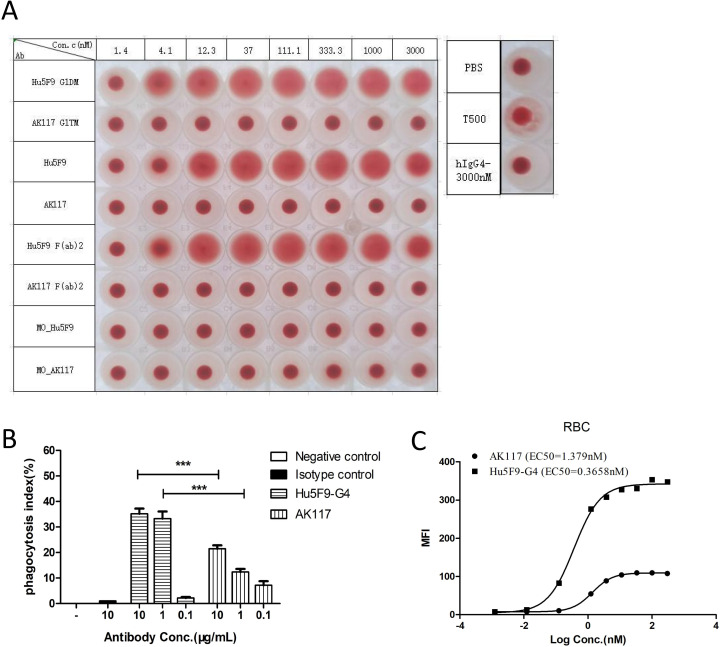

AK117 does not induce RBC agglutination in vitro

The effects of AK117 on RBCs were investigated in vitro. The hemagglutination test showed that AK117 did not induce RBC hemagglutination even at concentrations up to 3000 nM, while Hu5F9-G4 induced RBC hemagglutination at concentrations as low as 4.1 nM (figure 2A). We examined whether bivalency is necessary for hemagglutination of Hu5F9 and if antibody isotype would contribute to hemagglutination. Thus, we constructed monovalent and bivalent Hu5F9-G4 and AK117, respectively, to detect their hemagglutinating capabilities. The results demonstrated that monovalent Hu5F9-G4, monovalent AK117 and bivalent AK117 did not induce hemagglutination, while bivalent Hu5F9-G4 induced hemagglutination. We also constructed IgG1 and IgG4 subclasses of AK117 and Hu5F9. AK117-IgG1 and AK117-IgG4 did not induce hemagglutination, while both Hu5F9-G1 and Hu5F9-G4 induced hemagglutination. F(ab)2 fragment antibodies were also constructed to test capacity for hemagglutination. While AK117 and AK117-F(ab)2 did not induce hemagglutination, Hu5F9-G4 and Hu5F9-F(ab)2 did (figure 2A). These results indicated that bivalency is necessary for Hu5F9 to induce RBC agglutination, and antibody isotype has no influence on an antibody’s capacity for inducing hemagglutination. AK117 induced a significantly lower degree of phagocytosis of erythrocytes compared with that of Hu5F9-G4 (figure 2B). AK117 bound to human erythrocytes with an EC50 of 1.379 nM, the binding activity of AK117 to erythrocytes was significantly weaker than that of Hu5F9-G4 (figure 2C). These results reveal that AK117 has superior safety features over Hu5F9-G4, particularly in terms of hematological toxicity.

Figure 2.

Safety test on human RBCs in vitro. Hemagglutination of AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 (A). All versions of AK117 do not induce hemagglutination. Bivalent Hu5F9-G4 could induce hemagglutination but not monovalent version (Mo-Hu5F9). Phagocytosis of human RBCs by mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages mediated with AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 (B, n=6, one-way analysis of variance Newman-Kuels analysis, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01). FACS binding of AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 on human RBCs (C). PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RBC, red blood cell; FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting.

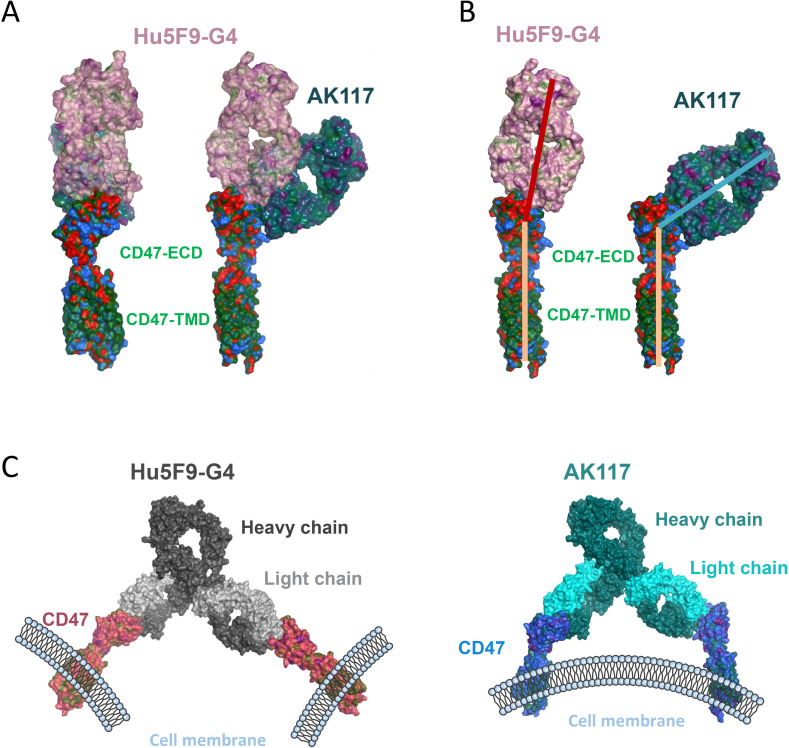

AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 have different binding epitopes with several shared residues on CD47 through in silico analysis

In order to understand the potential mechanism that AK117 does not induce hemagglutination, we performed an antibody structure simulation and antigen binding docking analysis. The Fab AK117 and the Fab Hu5F9-G4 (PDB ID: 5IWL) were well modeled, and the assembly analysis showed that both AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 interacted with CD47-ECD in specific regions. We overlapped the Fab fragments from AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 on CD47 protein and observed that AK117 oriented to CD47-ECD from side area, whereas Hu5F9-G4 formed a head-to-head conformation on CD47-ECD (figure 3A), indicating that the epitope binding regions of AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 on CD47 are different. Additionally, we found the binding epitopes of AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 on CD47 were partially overlapped (online supplemental figure S2A). Then the binding orientations of the Fab fragments from AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 on CD47 were analyzed and compared. The angle between the Fab Hu5F9-G4 and CD47 was about 180 degrees, while the AK117/CD47 complex formed a smaller angle (figure 3B). The different binding orientations of AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 on CD47 might be related to the distinct binding epitopes of AK117 and Hu5F9-G4.

Figure 3.

Binding conformation of AK117 in complex with CD47. (A) Superimposed structure of the Fab AK117 and the Fab Hu5F9-G4 (PDB ID: 5IWL) in complex with CD47-ECD. Based on the homology modeling, the Fab AK117 was constructed, and molecular docking with limitation on AK117 CDRs residues was performed. (B) Structural analysis of AK117/CD47-ECD and Hu5F9-G4/CD47-ECD complexes. The binding epitopes and the orientations were compared. (C) Structural analysis of AK117/CD47 and Hu5F9-G4/CD47 complexes on the whole IgG4 antibody (PDB ID: 5DK3). The spatial distances and the dihedral angles were compared. ECD, extracellular domain.

Next, we extended the structural analysis into the whole antibody to study the spatial structures of both AK117/CD47 and Hu5F9-G4/CD47 complexes in order to better understand whether the conformational changes induced by different binding orientations are related to hemagglutination. Hu5F9-G4 bound two CD47 proteins and formed a Y-shaped conformation with a big distance between two CD47 proteins and a dihedral angle of 28.5 degrees (figure 3C, left; online supplemental figure S2B). However, AK117 bound two CD47 proteins which were almost parallel and their spacing was narrow, with a dihedral angle of 40.0 degrees (figure 3C, right; online supplemental figure S2C). Despite the bigger dihedral angle of the AK117/CD47 complex, it is not significantly different from that in the Hu5F9-G4/CD47 complex, which is unable to provide sufficient space to bind another cell. This analysis hints that AK117 is unlikely to bind two cells simultaneously due to its conformational changes, however, the Y-shaped conformation with big distance between two bound CD47 proteins is more allowable for Hu5F9-G4 to bind CD47 on two different cells, resulting in RBC agglutination.

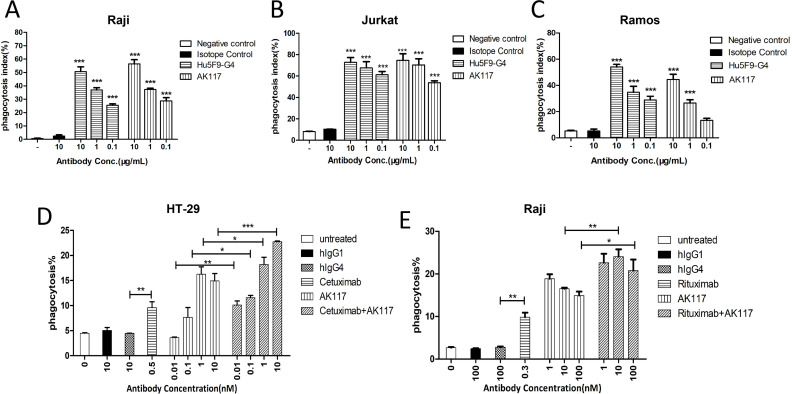

AK117 promotes phagocytosis of tumor cells in vitro

We initially investigated whether blockade of the CD47-SIRPα interaction by AK117 would enable macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of target cells in vitro. The phagocytic activity was measured by using a fluorescence microscope to count the number of ingested cells. At 0.1, 1, and 10 µg/mL of AK117, the phagocytic indices on Raji cells were 28.70%±2.44%, 37.28%±0.95%, and 56.44%±3.13%, respectively; the phagocytic indices on Jurkat cells were 53.78%±1.77%, 70.35%±5.78% and 74.62%±6.28%, respectively; the phagocytic indices on Ramos cells were 13.33%±1.55%, 26.47%±2.49% and 44.56%±3.97%, respectively. The results demonstrated that AK117 induced potent phagocytosis of Raji, Jurkat and Ramos cells in a dose-dependent manner by macrophages, with activity similar to that of Hu5F9-G4 (figure 4A–C).

Figure 4.

Phagocytosis of tumor cells with AK117 or combo with opsonizing antibodies. Phagocytosis of human Raji (A, n=5), Jurkat (B, n=4) and Ramos (C, n=6) by mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages mediated with AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 (one-way analysis of variance Newman-Kuels analysis, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, error bars represent mean±SEM of duplicate samples). Opsonizing antibodies cetuximab and rituximab increase AK117-driven phagocytosis of HT-29 (D) and Raji cells (E), respectively.

We also investigated the effect of AK117 in combination with different opsonizing antibodies on the phagocytosis of hematologic cancer and solid tumor cell lines by human macrophages in vitro. Human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages were used as phagocytic cells and the phagocytosis of HT-29 and Raji cells was detected when treated with the combination of AK117 with cetuximab and rituximab, respectively. The results indicated that the phagocytic index in each combo group was higher than that of the single drug-treated group in a dose-dependent manner (figure 4D, E).

AK117 demonstrates macrophages-mediated antitumor activity in a xenograft mouse solid tumor model, as monotherapy or in combination with AK112, a PD-1/VEGF bispecific antibody

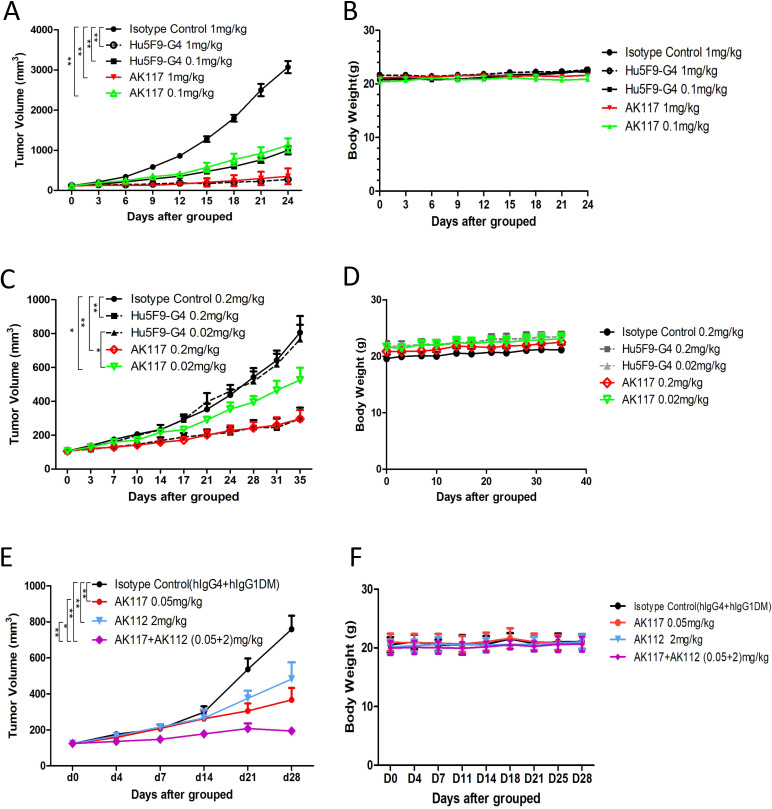

The antitumor activity of AK117 in B cell lymphoma and TNBC xenograft models was evaluated and compared with that of Hu5F9-G4. The results demonstrated robust antitumor activity of AK117 compared with isotype control groups, and the tumor growth in both Raji and MDA-MB-231 xenograft models was significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner. Intravenous injection of Raji xenografts with AK117 or Hu5F9-G4 (1 mg/kg and 0.1 mg/kg, respectively) resulted in more than 50% inhibition of tumor growth (88.56% and 63.78% TGI at 1 and 0.1 mg/kg of AK117, and 91.40% and 67.49% TGI at 1 and 0.1 mg/kg of Hu5F9-G4, respectively) in comparison with isotype control group, and there was no obvious body weight loss among all groups (figure 5A, B). In MDA-MB-231 xenograft model, AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg inhibited tumor growth by more than 50% relative to isotype control group (AK117: TGI of 68.20%; Hu5F9-G4: TGI of 62.74%), and antitumor activity of AK117 was significantly higher than that of Hu5F9-G4 at the dose of 0.02 mg/kg (AK117: TGI of 34.96%; Hu5F9-G4: TGI of 5.25%). No significant body weight loss was observed among all groups (figure 5C, D).

Figure 5.

Monotherapy and combo therapy of AK117 demonstrated antitumor activity in vivo. (A, B) Efficacy and body weight change of AK117 in SCID/Beige mice bearing with Raji cells. (C, D) Efficacy and body weight change of AK117 in SCID/Beige mice bearing with MDA-MB-231 tumor cells. (E, F) Efficacy and body weight change of AK117 or combo with AK112 in SCID/Beige mice bearing with MDA-MB-231 cells. Tumor volumes were assessed two times per week. Error bars represent mean±SEM of tumor volumes. Comparisons between groups were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance; *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01.

As the combination of CD47 and VEGF blocking agents showed a synergistic antitumor effect in non-small cell lung cancer model,31 and VEGF and PD-1 are known to have synergistic antitumor effect, we hypothesized that the co-blockade of CD47, PD-1 and VEGF may result in enhanced antitumor effect. We thus designed an experimental scheme for the combination of AK117 with AK112, a tetrameric bispecific antibody targeting PD-1 and VEGF-A developed by Akeso Biopharma. The antitumor activity of AK117 in combination with AK112 was investigated in the humanized PD-1 mice model against MDA-MB-231 xenografts. The results demonstrated that tumor growth was effectively inhibited in monotherapy and combination therapy groups, and dramatic inhibition effect was observed in the AK117 and AK112 combination group with statistically significant differences, and no obvious body loss of mice was found in all groups (figure 5E, F).

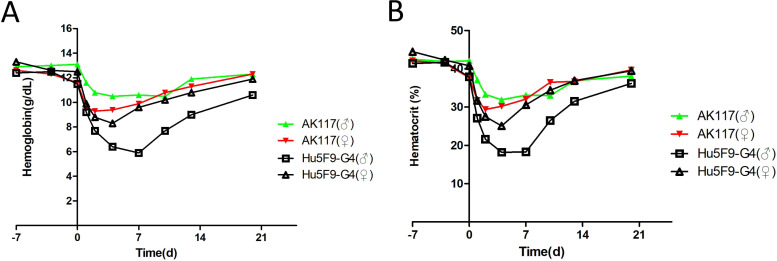

AK117 shows a favorable safety profile in non-human primates

The toxicologic assessment of AK117 was performed in cynomolgus monkeys. We detected that AK117 only bound to cynomolgus CD47, but not to rat or mouse CD47 by ELISA (online supplemental figure S3A). Additionally, AK117 bound to the cynomolgus monkey RBCs in fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) assay (online supplemental figure S3B), but did not induce RBC hemagglutination in cynomolgus monkey (online supplemental figure S3C). Two groups of cynomolgus monkeys were intravenously administrated with AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 at a single dose of 10 mg/kg, respectively. Changes in clinical signs, body weight, ECG and hematological parameters were evaluated in all cynomolgus monkeys during the 28-day observation period. The decrease of hemoglobin and hematocrit levels in the AK117 treated group were significantly shallower than the Hu5F9-G4 treated group. At day 7 post treatment, the hemoglobin and the hematocrit in AK117 treated males were 10.6 g/dL and 33.1%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those in Hu5F9-G4 treated males (hemoglobin: 5.9 g/dL; hematocrit: 18.3%); and the hemoglobin and the hematocrit were 9.9 g/dL and 32.1% in AK117 treated female monkeys, and 9.6 g/dL and 30.6% in Hu5F9-G4 treated female monkeys. Importantly, the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels spontaneously increased up and returned to baseline levels at day 20 after administration in all cynomolgus monkeys (figure 6A, B). Additionally, the relevant data of AK117 recorded at the doses of 30 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg showed no obvious hematological side effects in both male and female cynomolgus monkeys (online supplemental table S1). These results revealed that AK117 caused transient anemia, and was well tolerated, with no obvious adverse side effects in cynomolgus monkeys.

Figure 6.

Non-human primate toxicology studies show good safety. (A, B) Individual cynomolgus monkeys were administered with single intravenous infusions of AK117 at the 10 mg/kg. The hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were monitored over 3 weeks.

Discussion

In this study, our findings demonstrated that AK117 binds human CD47 with high affinity, blocks CD47-SIRPα interaction, and achieves excellent antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo, especially when combined with different antibodies. More importantly, AK117 does not induce RBC hemagglutination compared with Hu5F9-G4, which provides the mechanistic foundation for improved safety profile for AK117. The study in non-human primates also shows that AK117 has much milder reduction of hemoglobin compared with Hu5F9-G4. Also, the hemoglobin reduction effect induced by AK117 is transient in nature, and could be recovered spontaneously.

CD47 is widely distributed in tumor cells and normal cells, especially in RBCs. At present, the main side effects of CD47 blocking antibodies are RBC hemagglutination and anemia, which limits the clinical application of CD47 antibody. Several approaches are being explored to cope with these problems. In these cases some antibodies are designed to bind negligibly to CD47 on RBCs and some are designed as bispecific antibodies, which reduce binding to CD47 through the high affinity of another target.22 An important question is whether reduced affinity for CD47 could also affect the effectiveness of CD47 blockade that relates to antitumor effect. Our studies found that AK117 does not induce RBC hemagglutination, and can also maintain full effectiveness of CD47 blockade on tumor cells. The exploration of hemagglutination resistance showed that monovalent Hu5F9-G4 did not induce hemagglutination, while the bivalent Hu5F9-G4 did induce hemagglutination, and neither monovalent nor bivalent AK117 induce hemagglutination. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that AK117 only binds CD47 on one RBC, while Hu5F9-G4 can simultaneously bind CD47 on two separate RBCs and thus could lead to hemagglutination. Moreover, the molecular simulation-based spatial structure analyses suggested that the AK117/CD47 complex demonstrated a distinct binding conformation compared with the Hu5F9-G4/CD47 complex. The Y-shaped conformation of Hu5F9-G4/CD47 complex might contribute to the binding of Hu5F9-G4 to two separate RBCs, while AK117 could not. Additionally, we detected whether IgG subclasses and Fc region of both AK117 and Hu5F9-G4 influenced on RBC hemagglutination, and the results indicate that IgG subclasses and Fc region are not the factors affecting RBC hemagglutination. At present, there are more than 10 CD47 monoclonal antibodies in clinical trials stage, and for many antibodies the mechanisms related to RBC hemagglutination have not been reported so far. It is reported that TJC4 negligibly binds to human RBCs, and the mechanism of its binding to CD47 is studied as well. The structure of TJC4-CD47 complex is a novel conformational epitope with a straight head-to-head binding and an N-linked glycosylation site nearby the two critical epitopes on the CD47 protein prevents its binding to human RBCs.32 A study on SRF231 reported that it did not induce hemagglutination in vitro may be related to the binding mode of RBCs, which may be similar to the binding mode of AK117 to RBCs.33

Meanwhile, the antitumor activity of AK117 was comparable to that of Hu5F9-G4 in vitro and in vivo studies. AK117 as a single agent or in combination with other antitumor drugs may provide new anticancer therapy. CD47 blocking antibodies have been explored in combination with various antitumor agents, such as FcR activating antibodies and antibodies with different targets. Some studies have shown that cetuximab or rituximab synergizes with CD47 blocking antibody through enhanced FcR-mediated antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis coupled with blockade of the antiphagocytic CD47 signal by anti-CD47 antibody.34 35 Our study also demonstrated significant enhancement of antitumor effect when AK117 was combined with cetuximab and rituximab, which is consistent with previous studies. Accumulating evidence has increasingly supported the strategy of multitarget combination therapy. It is reported that CD47 upregulation limits the antitumor effect of VEGF/VEGFR inhibitors. And, blocking VEGF/VEGFR pathway increases the expression of CD47 on tumor cells, consequently inhibiting the antitumor effect of macrophages.31 Therefore, we believe that simultaneous blockade of VEGF and CD47 would effectively inhibit the immunosuppressive pathway induced by anti-angiogenic therapy and enhance macrophage-mediated phagocytosis to improve antitumor effect. Furthermore, CD47 blockade also activates the adaptive immune system by triggering T-cell responses primarily through dendritic cells.15 Dendritic cells play a key role in innate immune response and adaptive immune response,36 37 and play a critical role in T cell-mediated tumor immunotherapy.38 39 Thus, co-blockade of CD47, PD-1 and VEGF by AK117 and AK112 (a PD-1/VEGF bispecific antibody) in combined therapy may activate both innate and adaptive immune systems and enhance the directional recognition of tumors by human immune system. In this study, we evaluated the antitumor efficacy of AK117 combined with AK112 in the TNBC xenograft model, and the results showed that the antitumor efficacy was significantly improved.

The phase I clinical study of AK117 also showed that AK117 was well-tolerated up to 45 mg/kg every week (data not published) in subjects without dose-limiting toxicity events and no hematological treatment-related adverse events were observed in patients. Therefore, AK117 does not require a lower ‘priming’ dose to prevent anemia. CD47 receptor occupancy of AK117 on T lymphocytes in peripheral blood of subjects reached and maintained 100% at a dose of 3 mg/kg only, full and durable receptor occupancy in peripheral blood was observed at ≥10 mg/kg.40 All these data reveal that AK117 has excellent safety features in clinical application. Based on preclinical data and early clinical results, a series of phase IB/II clinical study of AK117 combined with various agents for the treatment of a number of cancer types are in progress (NCT04900350, NCT04980885, NCT05227664, NCT05229497, NCT05214482, NCT05235542 and NCT05382442).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the colleagues who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: TQ, TZ, XP, ZH, CJ: Formal analysis, investigation, writing, review and editing of the manuscript. ZMW, YX (MX): Conceptualization, supervision, review and editing of original draft. BL: Conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, validation, investigation, methodology, project administration, review, editing of the manuscript and taking responsiblity for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: This study is funded by Akeso Biopharma. Grant/award number is not applicable.

Competing interests: The authors are all employees of Akeso Biopharma outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Beatty GL, Gladney WL. Immune escape mechanisms as a guide for cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:687–92. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:252–64. 10.1038/nrc3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2018–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. First-Line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2415–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balar AV, Galsky MD, Rosenberg JE, et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2017;389:67–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32455-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1919–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng M, Jiang W, Kim BYS, et al. Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2019;19:568–86. 10.1038/s41568-019-0183-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lentz RW, Colton MD, Mitra SS, et al. Innate immune checkpoint inhibitors: the next breakthrough in medical oncology? Mol Cancer Ther 2021;20:961–74. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown EJ, Frazier WA. Integrin-Associated protein (CD47) and its ligands. Trends Cell Biol 2001;11:130–5. 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01906-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barclay AN, Van den Berg TK. The interaction between signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) and CD47: structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Immunol 2014;32:25–50. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vernon-Wilson EF, Kee WJ, Willis AC, et al. Cd47 is a ligand for rat macrophage membrane signal regulatory protein SIRP (OX41) and human SIRPalpha 1. Eur J Immunol 2000;30:2130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Jin S, Guo X, et al. Targeting the CD47-SIRPα signaling axis: current studies on B-cell lymphoma immunotherapy. J Int Med Res 2018;46:4418–26. 10.1177/0300060518799612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tseng D, Volkmer J-P, Willingham SB, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody-mediated phagocytosis of cancer by macrophages primes an effective antitumor T-cell response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:11103–8. 10.1073/pnas.1305569110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Pu Y, Cron K, et al. Cd47 blockade triggers T cell-mediated destruction of immunogenic tumors. Nat Med 2015;21:1209–15. 10.1038/nm.3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soto-Pantoja DR, Terabe M, Ghosh A, et al. Cd47 in the tumor microenvironment limits cooperation between antitumor T-cell immunity and radiotherapy. Cancer Res 2014;74:6771–83. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0037-T [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao XW, van Beek EM, Schornagel K, et al. Cd47-Signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα) interactions form a barrier for antibody-mediated tumor cell destruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:18342–7. 10.1073/pnas.1106550108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logtenberg MEW, Scheeren FA, Schumacher TN. The CD47-SIRPα immune checkpoint. Immunity 2020;52:742–52. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matozaki T, Murata Y, Okazawa H, et al. Functions and molecular mechanisms of the CD47-SIRPalpha signalling pathway. Trends Cell Biol 2009;19:72–80. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Wang L, Zhao F, et al. Pre-Clinical development of a humanized Anti-CD47 antibody with anti-cancer therapeutic potential. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137345. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorahy DJ, Thorne RF, Fecondo JV, et al. Stimulation of platelet activation and aggregation by a carboxyl-terminal peptide from thrombospondin binding to the integrin-associated protein receptor. J Biol Chem 1997;272:1323–30. 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Z, Sun H, Yu J, et al. Targeting CD47 for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:180. 10.1186/s13045-021-01197-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeidan AM, DeAngelo DJ, Palmer JM, et al. A phase I study of CC-90002, a monoclonal antibody targeting CD47, in patients with relapsed and/or refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): final results. Blood 2019;134:P1320. 10.1182/blood-2019-125363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikic BI, Lakhani N, Patnaik A, et al. First-In-Human, first-in-class phase I trial of the Anti-CD47 antibody Hu5F9-G4 in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:946–53. 10.1200/JCO.18.02018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeidan AM, DeAngelo DJ, Palmer J, et al. Phase 1 study of anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody CC-90002 in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Ann Hematol 2022;101:557–69. 10.1007/s00277-021-04734-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sallman DA, Donnellan WB, Asch AS, et al. The first-in-class anti-CD47 antibody Hu5F9-G4 is active and well tolerated alone or with azacitidine in AML and MDS patients: initial phase 1B results. JCO 2019;37:7009. 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.7009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, Kaas Q, Wehbi V, et al. Structure-Function relationships of the variable domains of monoclonal antibodies Approved for cancer treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007;64:210–25. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruffolo JA, Gray JJ, Fast GJJ. Fast, accurate antibody structure prediction from deep learning on massive set of natural antibodies. Biophys J 2022;121:155a–6. 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.11.1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schrödinger L, DeLano W. PyMOL, version 4.6.0, 2020. Available: http://www.pymol.org/pymol [Accessed Aug 2022].

- 30.Jiménez-García B, Roel-Touris J, Romero-Durana M, et al. LightDock: a new multi-scale approach to protein-protein docking. Bioinformatics 2018;34:49–55. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Wang Y, Fan J, et al. Blocking CD47 efficiently potentiated therapeutic effects of anti-angiogenic therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:346. 10.1186/s40425-019-0812-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng Z, Wang Z, Guo B, et al. TJC4, a differentiated Anti-CD47 antibody with novel epitope and RBC sparing properties. Blood 2019;134:P4063. 10.1182/blood-2019-122793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peluso MO, Adam A, Armet CM, et al. The fully human anti-CD47 antibody SRF231 exerts dual-mechanism antitumor activity via engagement of the activating receptor CD32A. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000413. 10.1136/jitc-2019-000413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chao MP, McKenna KM, Cha A, et al. Abstract PR13: the anti-CD47 antibody Hu5F9-G4 is a novel immune checkpoint inhibitor with synergistic efficacy in combination with clinically active cancer targeting antibodies. Cancer Immunol Res 2016;4:PR13. 10.1158/2326-6066.IMM2016-PR13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cell 2010;142:699–713. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998;392:245–52. 10.1038/32588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabado RL, Balan S, Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Cell Res 2017;27:74–95. 10.1038/cr.2016.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayoux M, Roller A, Pulko V, et al. Dendritic cells dictate responses to PD-L1 blockade cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med 2020;12. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav7431. [Epub ahead of print: 11 03 2020] www.science.org/doi/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh SA, Wu D-C, Cheung J, et al. Pd-L1 expression by dendritic cells is a key regulator of T-cell immunity in cancer. Nat Cancer 2020;1:681–91. 10.1038/s43018-020-0075-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gan HK, Coward J, Mislang ARA, et al. Safety of AK117, an anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors in a phase I study. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2630. 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.2630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2022-005517supp001.pdf (114.3KB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005517supp002.pdf (4.5MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.