Abstract

Background

Lack of political will is frequently invoked as a rhetorical tool to explain the gap between commitment and action for health reforms in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, the concept remains vague, ill defined and risks being used as a scapegoat to actually examine what shapes reforms in a given context, and what to do about it. This study sought to go beyond the rhetoric of political will to gain a deeper understanding of what drives health reforms in SSA.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using Arksey and O’Malley (2005) to understand the drivers of health reforms in SSA.

Results

We reviewed 84 published papers that focused on the politics of health reforms in SSA covering the period 2002–2022. Out of these, more than half of the papers covered aspects related to health financing, HIV/AIDS and maternal health with a dominant focus on policy agenda setting and formulation. We found that health reforms in SSA are influenced by six; often interconnected drivers namely (1) the distribution of costs and benefits arising from policy reforms; (2) the form and expression of power among actors; (3) the desire to win or stay in government; (4) political ideologies; (5) elite interests and (6) policy diffusion.

Conclusion

Political will is relevant but insufficient to drive health reform in SSA. A framework of differential reform politics that considers how the power and beliefs of policy elites is likely to shape policies within a given context can be useful in guiding future policy analysis.

Keywords: Health policy, Review, Health systems

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), political will or lack of it is often summarily regarded as the central variable to explain why health reforms are implemented or not to the risk of becoming banal.

Superficially invoking the concept as a ‘catch-all culprit’ with ‘little analytic content’ precludes a deeper understanding of the actual drivers of policy change, thereby constraining policy learning to effectively inform future reforms.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Political will is relevant but not sufficient to drive health reforms in SSA African countries since in reality reforms are mediated by the perception of costs and benefits among actors, the distribution and exercise of power at the elite level, political ideologies and policy diffusion across settings.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Proponents of policy change should cease bemoaning lack of political will and integrate their technical know-how with the relevant political skills and strategies to enhance the feasibility of desired reforms.

Introduction

Health systems in Africa conjure an image of neglect and catastrophe,1–7 with a widespread call for urgent reforms.2 6 8 9 These reforms are often captured in various transnational declarations.10–12 Despite the wide array of declarative commitments, real action is slow and progress is retarded.13 14 This mismatch is often blamed on the ‘lack of political will’2 15 with persistent demand for it.16–20 Political will has been cited as the underlying driver for transformative health sector reforms internationally15 and among African countries.21–24 Political will has been defined as the commitment of actors to undertake actions to achieve a set of objectives and to sustain the costs of those actions over time.25 Although frequently invoked as a rhetorical tool in political discussions, the concept of political will remains ambiguous and one of the ‘slipperiest concept in the policy lexicon’’ that is often presented as a ‘catch-all culprit’ with ‘little analytic content’.25–28 Some critics view the default to ‘lack of political will’ as a ‘lazy and unproductive’ scapegoat to actually examine what is either driving or blocking the proposed reforms, and what to do about it.29 The concept itself is complex because it involves intent and motivation, which are inherently intangible and susceptible to manipulation.25 In the context of health reforms, the concept personalises policy change by emphasising individual leaders’ political will as the sole driver of reforms, which tends to ignore the political constraints and risks associated with reform process.30 From a scholarly perspective, although the concept is oft-regarded as the central variable behind the health reforms, it is predominantly treated as an exogenous factor or ‘black box’ concept which is not amenable to a detailed analysis.31 A vague focus on ‘political will’ also ignores the role of values, ideologies, political skill and institutions as structural determinants of political action.31 This article seeks to go beyond the narrative of political will to account for health reforms in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) through a scoping review of available literature.

At a general level, scoping studies aim to rapidly map the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available, and can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right, especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before.32 Since the aim of our study was to understand the drivers for reform across Africa and for various reform areas, synthesising available literature provided a more feasible approach to rapidly map the key concepts compared with a primary study. Second, to our knowledge, the drivers of health reform in SSA are seldom comprehensively reviewed and synthesised evidence on the issue is not readily available. Therefore, in line with one of the specific aims of a scoping review, in this study, we sought to describe in detail the drivers of health reforms across diverse policy areas in a range of countries in SSA, thereby providing a mechanism for summarising and disseminating the findings to policy makers, practitioners and consumers who might otherwise lack time or resources to undertake such work themselves.32 Thus, by condensing the available literature and highlighting the key themes, this scoping review provides a potential framework to guide future primary research that seeks to understand in-depth the drivers for health reforms in specific SSA contexts.

Methods

This article used scoping review methods developed by Arksey and O’Malley32 to understand the drivers of health reforms in SSA. We selected this approach because of its emphasis on flexibility, reliance on an abductive logic of enquiry, and its bias towards narrative driven summation.33 The framework is presented as an iterative, qualitative review with five distinct stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results.

Patient and public involvement statement

It was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Research question

‘What is known from existing literature about the drivers of (non) health reforms in SSA?’

Identifying relevant studies

In line with prior studies,34 we developed a search strategy that covered three dimensions of the relevant studies: (1) the policy area of interest (health reforms), (2) the object of interest (policy processes/change) and (3) the geographical coverage (SSA). To refine the search, key health reforms such as primary healthcare (PHC) and universal health coverage (UHC) were expressly included in the search strategy based on the authors’ priori knowledge on health system reform efforts in SSA. While previous reviews have focused on specific policy areas, we maintained a wider policy interest to determine whether certain reform areas dominate research coverage and its potential implications.

Data search

Between May and July 2022, we conducted a comprehensive literature search in three electronic databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Academic Complete and WHO Global Medicus. A variety of search terms were used: Health AND Politics AND Africa, Limit to geography-Africa, South of Sahara, Political economy AND Health AND Africa, Primary health care AND politics AND Africa, Political economy AND Universal Health Coverage AND Low-middle income countries, Political economy AND Primary Health Care AND Low-middle income countries, Health AND power AND Africa. We also searched Google, Google scholar and the BioMed central (BMC) database through the ‘search all BMC articles’ portal: https://www.biomedcentral.com/. We purposively selected the BMC database due to its wider collection of journals with a focus on health systems in Low -and Middle -income Countries (LMICs) and the open access nature of the publications since we did not have access to other relevant paid-for databases such as CINAHL, Scopus and Web of Science. We also selected relevant papers from the International Journal of Health Policy and Management (IJHPM) Special Issue on Analysing the Politics of Health in Low-Middle-Income countries published in 2021: https://www.ijhpm.com/article_4039.html. We also reviewed the publications by members of the Social Science Approaches for Research and Engagement in Health Policy and Systems (SHAPES) Thematic Working Group (TWG) which are shared through a fortnightly email update. We reviewed the fortnightly updates from 1 September 2021 to 17 August 2022 which coincides with the period of the authors’ membership to the SHAPES TWG. We purposively selected the fortnightly updates from SHAPES because it focuses on key thematic areas related to this study such as power and policy analysis. Due to the centrality of power in health reforms, we also reviewed the ‘10 best resources on power in health policy and systems in low- and middle-income countries’ published by the Health Policy and Planning Journal in 2018 https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/33/4/611/4868632.

Screening

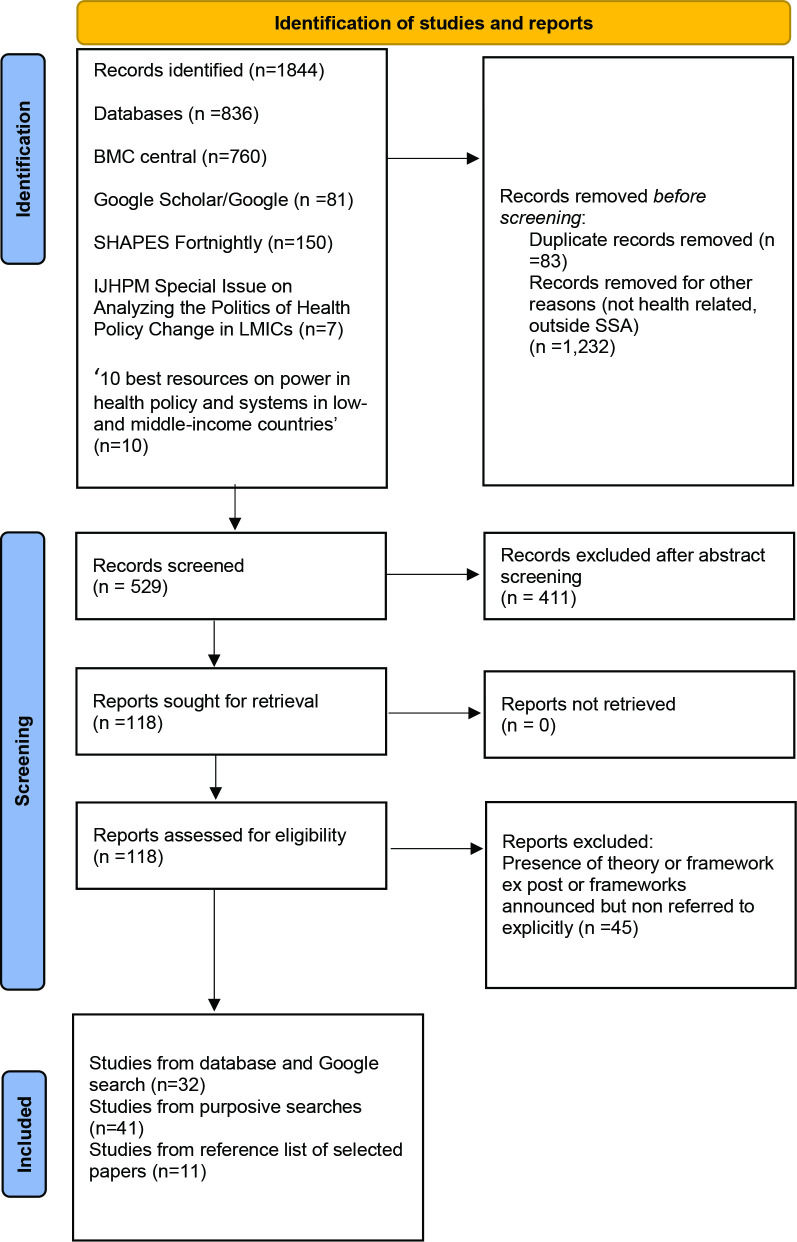

ATM conducted the screening process. The initial search generated 1844 papers. No time limit was set for the studies. Screening of the retrieved papers involved three sequential stages. The first stage involved title screening of all the papers. From this process, 83 duplicates were immediately removed. A further 1232 papers were removed for either being non-health related or being from outside SSA. In the context of this study, SSA is, geographically the area of the continent of Africa south of the Sahara. Countries from the Middle East/North Africa region: Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia were therefore excluded. Non-health papers included general country profiles and coverage of reforms in other social sectors such as education, agriculture and housing and politics in general. After the title screening, 529 papers were eligible for the second stage which involved abstract screening. Out of these, 411 were excluded chiefly for not focusing on policy process. These papers were largely descriptive without explaining the drivers of such (non) reforms and fell into three broad categories: (1) those elaborating the importance of policy (2) those highlighting the risks of not implementing a given policy and (3) those showcasing benefits of reforms. Of the 118 papers that were eligible for full article screening, 45 were removed because they either included theory or framework ex post or frameworks announced but none referred to explicitly during analysis. This left a final list of 73 articles for data extraction and analysis. An additional 11 articles were obtained from the reference list of selected papers. A final list of 84 papers was eligible for full analysis. A detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for relevant studies

| Criteria | Applied to title and abstract screening to select relevant studies (stages 1 and 2) | Applied to full-text screening for eligibility (stage 3) |

| Inclusion |

|

|

| Exclusion |

|

|

Adapted from Jones et al (2021).

SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

Data extraction

After identifying eligible articles, ATM conducted the data charting. Data charting is a technique for synthesising and interpreting qualitative data by sifting, charting and sorting material according to themes. Themes can be known or pre-established before data extraction (inductive approach) or emerge as data extraction begins and patterns start to form (deductive approach). In this study, we drew themes using both an inductive and deductive approach. Inductively, we drew themes from two papers that examined the concept of political will as an explanatory variable for (non) health reforms. The first paper by Baum et al used eight case studies from Australia to examine the determinants of political will for pro-health equity policies and how political will can be created through analysis of public policy.35 The second paper by Michael Reich synthesises relevant critiques on the application of the concept of political will to understand health reform process, including in LMICs.30 We also examined the main themes from the two supplements that focused on the politics of health reforms namely the Special Issue on Analysing the Politics of Health in LMICs published in the IJHPM in 2021 and the 10 best resources on power in health policy and systems in LMICs published by the Health Policy and Planning Journal in 2018. Through an integrative synthesis of these sources, we identified five relevant themes (1) the distribution of costs and benefits arising from policy reforms; (2) the form and expression of power among actors; (3) the desire to win or stay in government; (4) political ideologies and (5) elite interests. A data charting tool (extraction tool) was developed in Microsoft Excel capturing essential characteristics such as the title of the paper, year of publication, policy issue under study, theory used, the policy stage, reform drivers and other relevant attributes as shown in detail in table 2.

Table 2.

Publication characteristics and reform aspects

| Publication characteristics | Reform aspects |

| Authors | Distribution of costs and benefits |

| First author affiliations (institution, location) | Form and expression of power |

| Year of publication | Desire to win or stay in government |

| Title | Political ideologies |

| Journal | Elite interests |

| Study setting: country/countries where study was conducted | Transnational and national policy diffusion |

| Policy issue | |

| Framework/theory used |

Data analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis by categorising the contents of each eligible article according to the five themes mentioned above. The first step involved verbatim extraction of text excerpts from the selected articles, which were categorised according to the themes in the data charting tool. The second step involved an iterative process of interpretive data analyses and refining, including an analysis of how a given reform driver played out similarly or diverged across geography and time. Through this iterative process, a sixth theme emerged: the influence of transnational and national policy diffusion as a reform driver. This emerging theme was incorporated into the data extraction tool and all the papers were examined against the emergent theme. Pivot tables were run in Microsoft Excel to collate and summarise the results on publication characteristics and reform aspects.

Results

The selection process is shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram in figure 1. The policy studies were drawn from more than 30 different countries from Southern, Central, East and West Africa. Out of the 84 studies included, two countries accounted for more than 40% of the total studies, with South Africa accounting for 22% of the total studies while Ghana accounted for 19%.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

The general profile of the selected papers is shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Profile of reviewed studies

| Policy stage | |

| Stage | No of papers |

| Agenda setting and formulation | 67 |

| Agenda setting, formulation and implementation | 2 |

| Implementation-national level | 4 |

| Implementation-service delivery level | 11 |

| Reform issue | |

| Financing | 28 |

| NHI | 11 |

| PBF | 5 |

| General health financing | 4 |

| User fees | 4 |

| User fees and NHI | 1 |

| CBHI | 1 |

| Earmarked tax for HIV/AIDS | 1 |

| Financial protection | 1 |

| Reproductive, maternal and child health | 12 |

| Abortion | 4 |

| Maternal health | 4 |

| Maternal and child health | 3 |

| Child health | 1 |

| HIV/AIDS | 9 |

| ARV policy | 4 |

| VMMC | 2 |

| General HIV/AIDS policy | 2 |

| PMTCT | 1 |

| Service delivery | 6 |

| Doctors and nurses | 4 |

| Community health workers | 1 |

| General | 1 |

| Other reform issues | 3 |

| Location of first authors | |

| Regional location | No of papers |

| Africa | 52 |

| Africa/Europe | 5 |

| Europe | 17 |

| North America | 4 |

| USA | 6 |

| Years of publication | |

| Years of publication | No of papers |

| 2002–2014 | 22 |

| 2015–2022 | 62 |

ARV, Antiretroviral; CBHI, Community-Based Health Insurance; NHI, National Health Insurance; PBF, Perfomance-Based Financing; PMTCT, Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission; VMMC, Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision.

Drivers for reform

The next sections present how the drivers for health reforms identified earlier influenced (non) health reforms in SSA: (1) the distribution of costs and benefits arising from policy reforms; (2) the form and expression of power among actors; (3) the desire to win or stay in government; (4) political ideologies; (5) elite interests and (6) transnational and national policy diffusion.

The costs and benefits of reforms

Health policy reform efforts face resistance because they commonly place concentrated new costs on well-organised, powerful groups while seeking to make new benefits available to non-organised and powerless groups.30 In Ghana, the transition from the pay for service arrangement or ‘cash and carry system’ to a National Health Insurance (NHI) in the early 2000s received popular support because the working middle class wanted to be relieved of the burden to cater for their own health and that of extended families36 37 and parliamentarians desired to offload the constituents’ incessant demand for money to cater for personal health needs.22 Contrary, the middle class in South Africa showed apathy towards advocating for the NHI policy because they benefited from a labour structure that provided them with private sector health.38 At institutional or bureaucratic level, reforms with fiscal implications were slowed down or derailed due to divergent frames between the Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Finance (MOF) as in the case of South Africa.39 40 Through its power to set the macroeconomic agenda and control the government budget, the MOF’s lack of support technically vetoed the NHI off the policy agenda. In contrast, in Uganda the coalition of MOF and other ministries facilitated the NHI’s ascension and maintenance on the policy agenda41; a coalition that similarly favoured the development of the AIDS Trust fund.42 However, the Social Health Insurance (SHI) was resisted because it was viewed as threat to the authority and influence of the existing insurance management entity.41 The other reform driver relates to the extent to which the private sector perceives the costs and benefits arising from reforms. Private sector interests, particularly market protectionism dampened SHI and NHI oriented reforms in Ghana,43 Uganda,41 Zimbabwe24 and South Africa.39

Reform propsects are also dampened if they are perceived as a threat to non-material benefits such as professional status which explained nurses’ resistance to community health worker programmes in Zambia44 and Burkina Faso.45 Studies have also found that reforms with public health benefits but with commercial costs and fiscal implications are subject to corporate resistance and under-prioritisation by governments particularly those aimed at controlling the production and use of tobacco,46 47 alcohol48 and sugar.49 While these examples portray the distribution of benefits and costs as the basis of interest group competition that derails reforms, there are examples to the contrary. In Ghana, the framing of Anti-Microbial Resistance (AMR) not as a health problem but a multisectorial threat enabled stakeholder cohesion that helped to set and sustain the AMR agenda under the OneHealth Approach.50

The form and expression of power

Power is defined as the ability or capacity to ‘do something or act in a particular way’ and to ‘direct or influence the behaviour of others or the course of events’. Koduah et al43 combined Mintzberg’s power concept, arenas of conflict of Grindle and Thomas28 and Sterman’s concept of policy resistance (2006) to examine the rise and fall of primary care maternal services from Ghana’s capitation policy.43 During the agenda setting and policy formulation stages; predominantly technical policy actors within the bureaucratic arena used their expertise and authority for consensus to influence the capitation basket. However, the political momentum was dampened during implementation when providers used their knowledge, skills, authority, social and professional identity to resist the policy changes. McCollum et al conducted an analysis of power within priority-setting for health following devolution in Kenya using Gaventa’s power cube and Veneklasen’s expressions of power.51 ‘Power over’—which involves direct decision-making power over other actors—was by far the most common expression of power as for the case of Ghana’s capitation policy. As a result of concentrated power and closed spaces for meaningful citizen participation, priority setting reforms in Kenya were manipulated in favour of elite preferences. In a study conducted in South Africa, Schneider et al showed that power over was a necessary condition for effective implementation of a maternal and child health initiative52; aided by self-efficacy (power to) and agency (power within). Usher38 used Power Resources Theory to demonstrate that the lack of support from the working class derailed support for the NHI in South Africa.38 Studies have also found that African Presidents have highly personalised power to decide what becomes or ceases to be policy.

Studies have also shown the power of global actors in influencing reforms. A study on malaria control in seven countries showed how the concentration of technical and financial resources in few donors provides them the power to distort local priority needs,53 a similar finding from a study on Perfommace-Based Financing (PBF) in Sierra Leonne.54 Crises also provides a window of opportunity for external agencies to wield additional levers of power. In Zimbabwe, the World Bank wielded financial and ideational power to steer Results Based Financing (RBF) post the socioeconomic crisis of the late 2000s55 as the case of the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) in South Sudan.56 In addition, crises enhance the attention of global actors towards previously marginalised issues, particularly if such a crisis is perceived as a global health security as the case with health system strengthening efforts in Guinea post the Ebola crisis.57 However, studies from countries such as Malawi and Zimbabwe have also shown that the influence of external agencies is moderated or resisted due to historical, cultural and political considerations at the implementation stage.53 55 58 The power of global actors is also constrained by the own rules that espouse adherence to the ideals of local ownership59 and lack of local ownership has been shown to derail reforms.60 Although power is often analysed from a top-down approach, application of Lipsky’s Street Level bureaucracy have found that health workers possess considerable discretionary power over the services, benefits and sanctions received by their clients on a daily basis. Such practices—often driven by personal values and necessitated by the realities of daily work demands—effectively become public policy, rather than the intentions or objectives of documents and statements developed at a central level.61–67 Although discretionary power is often viewed as active defiance to national policy that is fraught with negative consequences, studies have shown that it can be associated with desirable outcomes as health workers devise positive coping behaviours to deal with the imperative of service delivery within severely constrained environments62 63 67 or as a managerial innovation within a decision space.68

The desire to win or stay in government

Whether an issue would impact on staying in or winning government influences reforms35. This is based on an assumption that the ambition to gain power drives electoral competitors to pledge action on voters’ demands.36 In the aftermath of a democratic transition in Ghana in the early 1990s, the cash and carry system that was deeply despised by many Ghanaians became an attractive ground on which the opposition could challenge the ruling party36 69 and the repeal and replacement of the system with an NHI emerged as a cornerstone of its electoral campaign pledges.22 37 On electoral victory in 2000, the then newly elected president swiftly introduced the NHI to show the electorate that their party had fulfilled an election pledge, in the process bolstering the electoral chances for the next plebiscite. After the initial adoption of the NHI, political parties continued to propose technical changes with an electoral appeal,70 although the technical merits of such reforms were trumped by partisan politics, which culminated in non-implementation.71 Partisan politics, including competition for credit and counter-blaming for policy failures, have continued to characterise healthcare policies in Ghana, a phenomenon that was laid bare during the COVID-19 pandemic.72 In Uganda, user fees were hastily removed just before the 2001 presidential elections to bolster re-election chances41 and electorally appealing projects which could be easily showcased during election campaigns were prioritised for maternal health policies73 as in the case of priority setting reforms in Kenya.51 74 In Ethiopia, the massive expansion of PHC in the mid 2000s was partly driven by the government’s desire to win back opposition voters.75 Political declarations also provide a window of opportunity for reforms. The launch of the Free Health Care Initiative by the then president of Sierra Leone in 2000 was a key driver for the PBF reforms,54 while the Cameronian president’s electoral promise to fight against corruption favoured similar reforms.76 Studies have also shown that electoral competition generates incentives for incumbents to pursue vote-maximising policies that favour the basic health conditions of the rural population which constitutes the largest segment of voters.77

Political ideologies and societal values

We found that political ideologies significantly influenced health reforms, particularly those with widespread redistributive effects. In the 1980s, a socialist political orientation facilitated the adoption of a well-elaborated PHC strategy in Zimbabwe that was influenced by the desire to dismantle the colonial legacy of racially driven health inequities24; a similar path taken by South Africa during the postpartheid era.40 In Ethiopia, the decision to embark on widesperead PHC reforms was rooted in the ruling coalition’s developmental state strategy with a rural bias.31 Studies have also shown the influence of market economy ideologies. The neoliberal agenda of the 1980s–1990s had adverse effects in Ghana,36 Zimbabwe24 and Uganda.78 In South Africa, the SHI lost momentum when the country adopted the neoliberal-laden Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) 40 which favoured efficiencies and control of public sector expenditure.38 39 Political ideologies also intersect with social values. In Ghana, the NHI received popular support because it resonated with certain established societal values, norms and customs anchored on societal cohesion and mutual solidarity.79 In Zimbabwe, the Results Bsed Financing (RBF) model was initially resisted because of the perceived contradiction with the entrenched values of professionalism and labour market harmonisation.55 Social values also influence how scientific and epidemiological evidence can be used to inform or back policy. In Malawi, despite overwhelming evidence on the epidemiological and social burden of abortion in the country and generation of political will for action, abortion law reforms could not be effected due to religiously based opposition from the Christian and Muslim community.58 In Ghana, more political attention was directed towards breast cancer although there was evidence of more epidemiological and social burden for cervical cancer.80 This was because Ghanaian women’s organisations successfully drew attention to breast cancer by connecting it to powerful societal values associated with the breast such as breast feeding and motherhood while the social construction of cervical cancer as a disease caused by a sexually transmitted infection and poor genital hygiene dampened public appeal.Studies have also shown that political figures can selectively use or modify data to boost reforms that appeal to their own values and interests. In South Africa, the Minister of Health piled pressure on the committee working on health financing options to adapt its conclusions towards the Minister’s preferred insurance option39 while in Uganda political figures imposed ambitious targets for ending preventable maternal deaths to court political legitimacy.73 In Zimbabwe, the initial scale up RBF preceded sharing of the impact since there was no demand for robust evidence from the MOH due to the urgent need for funding while there was perceived bias towards positive evaluative results on the part of funders.55 Studies have also found that evidence is unlikely to induce reforms unless it resonates with the prevailing political philosophy as the case with population health policies in Ethiopia.81 Personal beliefs have also been shown to shape advocacy work. Application of Sabatier and Jenkins’ advocacy coalition framework on maternal health in Nigeria82 and access to HIV/AIDS treatment in South Africa83 showed that resonance of the core belief (personal philosophy) that health is an individual right motivated the formation of coalitions that pushed for reforms in those areas. Besides influencing advocacy coalitions, core beliefs have an important influence on policy choices. Reforms that threaten the core beliefs of policy makers and the public such as religion, culture and morality are generally subjected to doubt, defiance and resistance as in the case of male circumcision in Uganda and Malawi84 85 and abortion in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda.86–88 Core beliefs also reinforce political ideologies which significantly influence policy reforms through discursive practices that are shaped by history, including challenging dominant narratives and the pre-eminence of transnational actors. The framing of the cholera epidemic in Zimbabwe as a global health security necessitating some external intervention threatened the core belief that Zimbabwe was a sovereign country free from outside interference.89 As a result, the government mounted a vicious counter narrative that framed Cholera as a calculated racist terrorist attack by the former colonial power Britain and its allies as part of a grand strategy to recolonise Zimbabwe, tapping into the collective colonial memory when the British engaged in pathogen terrorism during the liberation struggle. This bioterror-colonial interdiscursivity resurfaced during the COVID-19 pandemic.90 Similarly, the racial and geographical profiling of AIDS as a disease that disproportionately affected black people explains President Thabo Mbeki’s denialist approach to the science of HIV/AIDS and the magnitude of the problem in South Africa since such ‘Black profiling’ was perceived to reimport the core belief of White supremacy that was perpetuated during the apartheid era.91 92

Elite interests

Elites consist of minority individuals or organised groups who wield substantial capacity to influence policy by virtue of possessing, such characteristics as power, wealth, skill, deference and monopoly to vital information.93 In this paper, we found one study that explicitly applied elite theory to analyse how actors’ interests and power influenced maternal health policies in Uganda between 2000 and 2015.73 In that study, Mukuru et al conceptualise elite interests as varying from self-interest (maximise personal benefits), to pragmatism (less powerful elites adjusting to accommodate the interests of the dominant elites) and public interest/altruism (genuine pursuit for public welfare). We found this characterisation to be useful in analysing elite behaviour in general, therefore it was applied to other studies that we reviewed although they did not explicitly apply elite theory. In Uganda, elites holding dominant power were mainly motivated by self interest such as the desire to secure electoral votes, establish personal legacies, maintain political appointments and accruing personal benefits from donor funds.73 On the other hand, elites with altruistic motives often lacked the power and clout to shape reform. Consequently, resulting policies often appeared to be skewed towards elites’ personal political and economic interests, rather than maternal mortality reduction. In Ghana, breast cancer was given more prominence because it affects elite women from higher socioeconomic groups who have access to political structures, while cervical cancer more frequently affects women of lower socioeconomic status.80 A study on priority setting under devolution in Kenya found that that elites often have unwielding influence on policy because they make decisions behind closed doors; akin to elite capture51 which aligns with the findings from Zimbabwe for the implementation of good governance for medicines (GGM) initiative94 and the abolishment of user fees in Uganda.41 Elites have also been found to be instrumental in public positioning of issues and construction of social problems (framing) to garner political support for reforms. In Malawi, doctors possessing first-hand knowledge of unsafe abortion persistently argued that the government must address unsafe abortion as part of its effort to reduce maternal mortality while lawyers framed access to abortion services as a human right that required a supportive legislative environment.58 Studies have also found that individual elites draw substantial power from their political and personal ties to push for desired reforms. In Ethiopia, the then Minister of Health Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus managed to push for PHC expansion and other health financing reforms partly due to his close relationship with the then Prime Minister Meles Zenawi75; similar acquaintances that facilitated the establishment of the AIDS trust fund in Uganda.42 Elites from international organisations also draw from similar proximity to power structures. In Uganda, some health development partners took advantage of their access to policy elites to influence maternal health policies, including conditioning grants towards areas aligned with their own interests.73 Personal characteristics of the policy elites also influence their leverage on reforms. In Zambia, the tactical ability and charismatic characterof the second Minister of Health was noted as instrumental in driving hospital reforms, a move that was also seen as part of his personal agenda to pro-up his own political profile40 while the then Ethiopian Minister of Health Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is regarded as ‘the prime mover’ for reforms in his country.75 Studies have also identified how political elites can manipulate the policy agenda through partisan appointees who ignore technical considerations to align with the interests of appointing authorities.37 We also found that the characterisation of elites as driven by altruistic motives or self-interests depends on who is ‘losing ‘or ‘winning’ from intended policies, a phenomenon that played it self out when pharmacists pushed for stricter laws to regulate medicine vendors in Uganda.95 Despite these self-interest motives, we found examples where elites were moved by altruistic motives. In South Africa, government officials who came from underprivileged communities found it important and necessary to change poor maternal health conditions of those communities and successfully lobbied for progressive reforms.96

Transnational and national policy diffusion

Transnational policy diffusion involves the mechanisms through which remarkably similar policy innovations spread across widely differing nation-states.97 It is a phenomenon characterised by temporal waves, spatial concentration and content commonality in diverse settings.98 Policy diffusion is influenced by) a) the success or failure of policies elsewhere (learning), b) by policies of other jurisdictions with which they compete for resources (competition), (C) c) by the pressure from international organisations or powerful countries (coercion) and d) by the perceived appropriateness of policies (emulation).99 The period from the 2000s is dominated by diffusion of policies aimed at achieving UHC through health financing reforms such as SHI, NHI, Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI), abolishment of user fees and PBF.22 38 41 55 75 76 78 79 100–103 While the diffusion of SHI, NHI and abolishment of user fees was mainly through the broad ideational movement towards financial protection, we found that emulation and learning fostered the uptake of CBHI and PBF across diverse settings. The acceptability of PBF in Cameron was influenced by encouraging results from Rwanda and the involvement of senior MOH officials in regional meetings where countries that had started PBF reported quicker progress towards Millennium Development Goals.76 This transnational policy diffusion was driven by networks and experts or diffusion entrepreneurs from the World Bank and other technical agencies. In relation to CBHI, Ethiopian officials conducted feasibility studies to Senegal, then considered the leading African example of CBHI75 but the design was strongly influenced by the success of Rwanda’s Mutuelles de Santé which was considered as a ‘pilot site’ by one official. In relation to HIV/AIDS financing, the adoption of the AIDS trust Fund in Uganda was influenced by the success of a similar mechanism in Zimbabwe.42 The influence of transnational networks was not limited to health financing aspects. In Malawi, the generation of political priority for abortion law reforms was influenced by a network of international and local diffusion entrepreneurs who took advantage of global movements and domestic contexts to push for reforms,58 a similar situation with the generation of political attention for breast cancer in Ghana.80 Studies have also found that the diffusion of certain policies is favoured by prevailing ideational paradigms through the active contribution of diffusion entrepreneurs at global level. That was the case with national medicines policies which were visibly promoted by the third WHO Director general Dr Halfdan Mahler after the inclusion of access to essential drugs as a component of PHC.104 Studies have also found Global Health Institutions (GHIs) can strategically coalesce to endorse the legitimacy or illegitimacy of policies in SSA, often in alignment with the dominant position of institutions with perceived global clout. In the 1980s–1990s, GHIs endorsed the World Bank’s stance on the introduction of user fees and aligned with the same institution when it called for their removal in the 2000s.105 Apart from the geospatial diffusion, studies have also found the temporal diffusion of policies within the same country as the case of CBHIs which served as a learning precursor for the NHI in Ghana.36 This temporal diffusion also explains how Ghana’s fee exemption policy for maternal health initiated in 1963 was maintained over the years in a path-dependent manner.106 While policies are dominantly framed as diffusing from norm-setting agencies at global level to SSA following a rigorous evidentiary process, exceptions exist where country level implementation influenced global policy. Pragmatic considerations influenced Malawi to adopt Option B+for Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission for HIV/AIDS ahead of WHO recommendations and guidelines; a policy that rapidly diffused to other countries in the absence of normative (formalised) guidelines from WHO.107 This ‘bottom-up’ diffusion also occurred within a national jurisdiction when provincial implementation of ARV policy in South Africa fostered federal homogeneity, which eventually became national policy.108 Table 4 shows the drivers for reforms and non-health reforms in SSA.

Table 4.

Drivers for reforms and non-health reforms in SSA

| Driver | Reform aspects | Non-reform aspects |

| Distribution of costs and benefits |

|

|

| Form and expression of power |

|

|

| Desire to win or stay in government |

|

|

| Political ideologies |

|

|

| Elite interests |

|

|

| Transnational and national policy diffusion |

|

|

+ positive effect (favours implementation of reforms that promote access to health, particularly for marginalised populations). − negative effect (against reforms that promote access to health). +/− it can be either positive or negative depending on the context.

SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

Discussion

This study moved beyond the political will narrative and unpacked important drivers for health reforms in SSA. First, we found that actors directly or indirectly supported reforms in their favour whilst resisting or blocking those that are not in their favour. In certain contexts, the active resistance to unfavourable reforms by powerful coalitions countervailed domestic political will such as in the case of the SHI in Uganda,41 capitation policy in Ghana,43 NHI in Ghana during the early phases of development37 and abortion law reforms in Malawi.58 These examples challenge the dominant view that lack of reforms or slow pace of progress is always a result of lack political will; demonstrating that political will can be vetoed by organised interests including private sector and pressure groups. This aligns with literature on health reforms35 109 110 from the African context111–113 and on the international scene.114–116 An interesting finding is how powerful groups and policy makers can push for reforms if there is a perception that existing policies impose concentrated costs at personal level and an anticipation of cost dispersion if reforms are effected. This is in line with Kingdon who posits that the personal experience of policy makers influences policy change.117 In light of the power of elites and their self-interest motives, lack of redistributive health reforms in SSA may therefore be partly explained by the fact that the elites themselves, including head of states, are not personally affected by the poor state of public health services as they can resort to the private sector or seek medical care in foreign countries.118–120 Thus, lack of political will maybe driven by the disjuncture between the personal experiences of policy makers who benefit from alternative, well funded health systems as opposed to the often underfunded public health sector that primarily serves majority of underprivliged citizens.

This study also demonstrated the role of power in health reforms. Power was found to be concentrated in a few elites who can use their political, economic and social means to steer reforms in their favour at the expense of powerless groups.38 39 51 80 This expression of ‘power over’ aligns with Luke’s first dimension of power whereby an actor considers their situation and mobilize the means to act on a course they have determined,121 a form of power that has been identified in other studies from LMICs.122 123 Although this overt form of power was the most reported, a nuanced analysis reveals Luke’s second dimension of power where unfavourable reforms were prevented or illegitimised from appearing on the agenda.38 39 While power is often characterised as wielded by people or groups who act through domination or coercion, we found that power can not be objectified, instead it is fluid and dynamic according to shifting contexts. In this regard, advocacy coalitions and networks play a pivotal role to change power dynamics and resolving intractable policy stalemates as in the case of South Africa’s ARV policy 91 92 and sugar tax policy.49 This networked governance aligns with Focault’s assertion that ‘power is everywhere’ and ‘comes from everywhere’ 124 and the idea that the government’s role in global health has shifted from ‘rowing the boat’ to ‘steering the boat’.125 We also found that power can be used productively, including how opposition parties can initiate policy debates, form strategic pacts with ruling coalitions and capitalise on internal party solidarity to effect reforms.49 There are circumstances or windows of opportunity under which advocacy coalitions are likely to wield power. While global movements have been emphasised,126–129 we found that shifts to a democratised society provide a window of opportunity for citizens to push for reforms36 58 130 particularly if reforms are framed in a way that attracts previously marginalised groups or conflict expansion.131 That a shift to a democratic society underpins citizen participation in health underscores the role of institutions in enabling an advocacy driven policy change. On the other hand, it highlights the pitfalls of the dominant global discourse that emphasises citizens and civic society participation without looking at the structural environment that hinders such action. While power is often framed from the top-down perspective, we found that healthcare workers at service delivery power wield so much discretionary power that can distort policies, sometimes driven by genuine concerns arising from a disempowering work environment. Thus, the portrayal of front line workers as non-policy makers who are supposed to ‘follow national policy’ without considering their local circumstances and how they respond to it may partly explain why supposedly well-designed policies fail to be implemented, much to the frustration of central level planners. Thus, genuine political will, particularly expressed in policy documents and followed by financial and technical resources at the top, can be disarrayed if not aligned with the realities at service delivery level. This may explain why ‘poor staff’ attitude is oft cited as a major constraint to policies. Within this lens of street level bureaucracy, we posit that a summative blame of staff conduct without a closer look at the underlying drivers is conceptually handicapped and practically self-defeating.

The desire to win or stay in government plays a major role in shaping health reforms, particularly if the opposition political parties raise reforms on the campaign plank. However, reforms that are primary driven by electoral motives are often populistic, hurried and technically weak78 as in the case of user fee removal132 and community health initiatives.122 This study also found that political ideologies have a profound effect on policy reforms. This departs from the theories that focus on interest group mobilisation, electoral competition and bureaucratic actors to explain policy reform.75 One ideological lens emphasises the role of political settlements or how paradigmatic ideas on political, economic and social aspects interact to shape reforms. In Ethiopia, the interests and ideas of the ruling coalition were identified as important drivers of progressive reforms in the 2000s,75 largely influenced by a developmental state ideology. This political settlement paradigm aligns with the positive health transformation experience in Rwanda post the 1994 genocide23 and Zimbabwe in the 1980s.133 However, the pursuit of a neoliberal agenda in Zimbabwe in the 1990s; and the attendant adverse effects24 is emblematic of how a shift towards market oriented political settlements can damage health systems as in the case of Ghana,134 South Africa100 and several Latin American countries.135

This study has highlighted how political elites can dominate reforms and steer policies towards self-interests at the expense of altruistic choices aimed at public benefit. In addition, we found that technically sound reforms can be resisted if political support is construed as partisanly biased.43 This emphasises that political will is likely to be effective in mobilising social classes to support government policies when there is high ‘quality of government’ which has been defined as the composite of the rule of law, control of corruption and government effectiveness, which endears public trust.136 This puts into ambivalence the common assumption that securing the buy-in of politicians or generating political will guarantees progressive reforms. This may be partly because that expectation draws from the standard welfare economics that portrays policy makers as ‘benevolent social planners’ or individuals who only prefer choices that maximise social welfare.137 Within this frame, a further assumption is that as benevolent social planners, politicians will rationally use available data and evidence to inform policies. However, in this study we found that data and evidence that contradicts the core beliefs of the elite can be disregarded, altered, selectively used and manipulated to suit elite interests. The belief-evidence didactic is not only limited to controlling available evidence (content), instead powerful elites can endeavour to dismantle the institutional structures that shape unfavourable evidence and replace them with those that are likely to generate evidence that reinforces their own beliefs. This aligns with insights from other countries where the application of evidence was found to be ‘purpose-driven’ and predefined by political agendas,138 putting into sharp scrutiny the primacy of ‘evidence-based policy making’.139 However, evidence can wilfully or unwilfully shift elite beliefs if advocacy coalitions frame the non-uptake of evidence as lack of concern for citizen welfare and a breakdown in the social contract between the state and the citizens, particularly if there is interdiscursivity with publicly appealing discourses such as human rights. Generally, evidence is less contentious for non-distributive aspects such as clinical guidelines which do not naturally threaten the core beliefs.

Finally, we found the influence of national and transnational policy diffusion on policy reforms. Interestingly, while literature often analyses the diffusion of policies to SSA through the ‘imposition of preferences’ by powerful global actors, in this study we found that such a phenomenon might be particularly applicable to areas where donors have substantial interest such as malaria or specific reforms such as PBF. On the contrary, reforms with a redistributive component, particularly on health financing were influenced by local interests and electoral politics. In the same vein, the diffusion of epistemological ideas within international networks influenced domestic reforms on HIV/AIDS subject to extensive local adaptation. This is in line with the theory of policy diffusion which posits that decison makers makers filter thepolitical consequences of policies through the lenses of their ideological stances.140 These findings do not disregard the power of global actors; but demonstrate the agency of local actors. It therefore refutes the generalised portrayal of African countries as acquiescing recipients of imposed preferences. We further posit that an approach that emphasises how donors undermine health systems at the expense of domestic agency does not only pose a negative image on the part of donors. Instead, the desire for electoral legitimacy and the dominance of self-interests we found in this study suggests that such a narrative can be susceptible to political and elite manipulation. One possible way could be attributing weak African health system to deviant donor behaviour; in the process deflecting blame and distancing themselves from their legitimate role to act.

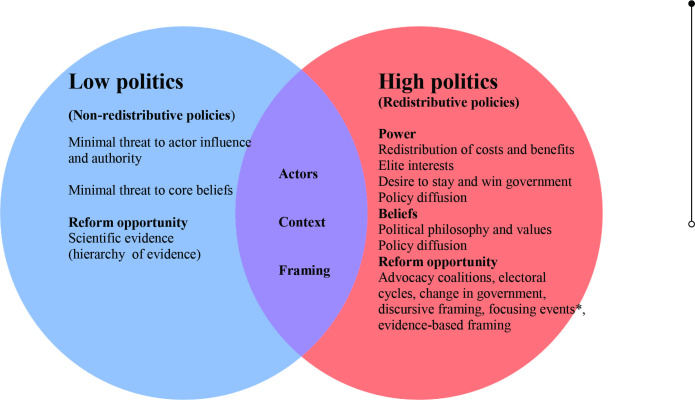

Differential reform politics

Although all reforms are inherently political, in this study we found that the intensity of interest group competition (politics) differs according to issue characteristics. In general, redistributive policies such as UHC are subject to more intense interests group politics (high politics) because they threaten the distribution of power compared with non-destributive policies such as clinical guidelines. Reforms that threaten the dominant beliefs of powerful elites, such as abortion and circumcision are equally subjected to high politics. Figure 2 presents a framework that differentiates reform politics and the opportunities that can arise to effect desired reforms. The framework would potentially guide policy makers and reform advocates to anticipate the likely intensity of interest group competition to effect desired reforms and identify windows of opportunities under which reform is likely to occur.

Figure 2.

Framework for differentiated health policy analysis and opportunities for reform. *Focusing events are events that bring an unprecedented attention to an issue.

Areas for further research

This study also found areas that may need further research. From a policy coverage issue, we found the dominance of policy analysis on health financing. While this may be driven by the fact that health financing is cross-cutting and fundamental to health reforms, such a bias neglects the politics of other areas critical to SSA context or ‘issues at the margins’ such as access to essential medicines, social determinants of health, corruption and non-communicable diseases. Further research is needed to understand the politics of these issues. We also found that most papers focused on the agenda setting and policy formulation stages at the expense of implementation politics. Considering the power of ‘street-level bureaucrats’, more studies are needed to understand how front-line health workers’s discretionary power can influence reform. We also found that applicable theories and frameworks are rarely used to analyse policies, which renders the analysis to surface conclusions such as ‘lack of political will’. A case in context is a study from Zimbabwe which identified political will as a key factor in promoting implementation of GGM without unpacking its determinants141; a critical gap that was addressed by a subsequent study that used relevant theory.94 Therefore, application of theories and conceptual frameworks need to be considered in future research to gain a deeper understanding of policy dynamics in SSA.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has strengths and limitations that need to be highlighted.

Strengths of the study

To our knowledge, this is one for the few studies that systematically synthesised wide sources of available literature to unpack the drivers of health reforms in SSA with a specific focus on the conceptual merits of political will. While reform oriented studies have mainly focused on policy change for redistributive policies that are often dominated by interest group politics, such as health financing or UHC, our study included a variety of policy areas to expand the understanding of policy drivers to non-redistributive policies. This expanded focus enabled us to unpack the role of political settlements and elite beliefs in shaping reforms, including how this affects the interpretation of evidence. This study also casts light on the discretionary power of healthcare workers which departs from the dominant norm of focusing on agenda setting and formulation studies. Finally, by incorporating various studies and highlighting some often neglected policy research areas, this study provides a potential framework that can stimulate further research in the future.

Limitations of the study

First, we could not access some relevant databases which might have potentially limited the range of literature sources we reviewed. The sources used may therefore not be comprehensive enough to draw conclusions. Nevertheless, the studies we reviewed covered a range of countries from all the regions of SSA on diverse policy issues. Second, the screening and data charting was conducted by one author without inter-author data triangulation, which may impair reliability. Third, grey literature papers that could potentially cover reform aspects were excluded from the review since majority of them did not use explicit theory to explain policy change. Finally, some of the papers we reviewed reported reform processes that cut across more than one area, for example, financing and HIV/AIDS, and it was challenging to singularly isolate the reform issue.

Conclusions

Political will is relevant but not sufficient to drive health reforms in sub-Saharan African countries. In reality, reforms are mediated by the perception of costs and benefits among actors, the distribution and exercise of power at the elite level, political ideologies and policy diffusion. These factors may be strong enough to trump the use of evidence to inform policy. Actors who desire to push for health reforms in SSA should seek to understand the salient drivers of health reform and move beyond the quick and convenient default to lack of political will as the reason for non-implementation of reforms. A framework of differential reform politics that considers how the power and beliefs of policy elites is likely to shape policies in a given context can be useful in guiding future policy analysis.

bmjgh-2022-010228supp001.pdf (308.7KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Handling editor: Valery Ridde

Contributors: ATM and CCM codesigned the manuscript. ATM led the conduct and analyses of the manuscript and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. Both authors made a substantial contribution to the structure and content of the manuscript. ATM is the guarantor responsible for the overall contents of this paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Azevedo MJ. The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Historical perspectives on the state of health and health systems in Africa, II. The Modern Era, 2017: 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oleribe OO, Momoh J, Uzochukwu BS, et al. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int J Gen Med 2019;12:395–403. 10.2147/IJGM.S223882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebremeskel AT, Otu A, Abimbola S, et al. Building resilient health systems in Africa beyond the COVID-19 pandemic response. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006108. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uwaezuoke SN. Strengthening health systems in Africa: the COVID-19 pandemic fallout. JPATS;1:15–19. 10.25259/JPATS_14_2020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoman H, Karafillakis E, Rawaf S. The link between the West African Ebola outbreak and health systems in guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone: a systematic review. Global Health 2017;13:1. 10.1186/s12992-016-0224-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders DM, Todd C, Chopra M. Confronting Africa's health crisis: more of the same will not be enough. BMJ 2005;331:755–8. 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monekosso GL. Meeting the challenges of the African health crisis in the decade of the nineties. Afr J Med Med Sci 1993;22:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regional Committee for, A . Implementation of health sector reforms in the African region: enhancing the stewardship role of government: report of the regional director. Brazzaville: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirigia J, Barry S. Health challenges in Africa and the way forward. In: Biomed central, 1. 1, 2008: 27–3. 10.1186/1755-7682-1-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witter S, Jones A, Ensor T. How to (or not to) … measure performance against the Abuja target for public health expenditure. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:450–5. 10.1093/heapol/czt031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assefa Y, Damme WV, Williams OD, et al. Successes and challenges of the millennium development goals in Ethiopia: lessons for the sustainable development goals. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000318. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otim ME, Almarzouqi AM, Mukasa JP, et al. Achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): a conceptual review of normative economics frameworks. Front Public Health 2020;8:584547. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.584547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govender V, McIntyre D, Loewenson R. Progress towards the Abuja target for government spending on health care in East and Southern Africa. In: EQUINET discussion paper 60, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, et al. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet 2021;397:61–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aregbeshola BS. Enhancing political will for universal health coverage in Nigeria. MEDICC Rev 2017;19:42–6. 10.37757/MR2017.V19.N1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anyangwe SCE, Mtonga C. Inequities in the global health workforce: the greatest impediment to health in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2007;4:93–100. 10.3390/ijerph2007040002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uwimana J, Jackson D, Hausler H, et al. Health system barriers to implementation of collaborative TB and HIV activities including prevention of mother to child transmission in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:658–65. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders D. Public health in Africa. In: Global public health: a new era, 1, 2003: 135–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenny AP, Yates R, Thompson R. Social health insurance schemes in Africa leave out the poor. Int Health 2018;10:1–3. 10.1093/inthealth/ihx046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert L, Walker L. HIV/AIDS in South Africa: an overview. Cad Saude Publica 2002;18:651–60. 10.1590/S0102-311X2002000300009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Østebø MT, Cogburn MD, Mandani AS. The silencing of political context in health research in Ethiopia: why it should be a concern. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:258–70. 10.1093/heapol/czx150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahab H, Aka PC. The politics of healthcare reforms in Ghana under the fourth Republic since 1993: a critical analysis. Can J Afr Stud 2021;55:203–21. 10.1080/00083968.2020.1801476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chemouni B. The political path to universal health coverage: power, ideas and community-based health insurance in Rwanda. World Dev 2018;106:87–98. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.01.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mhazo AT, Maponga CC. The political economy of health financing reforms in Zimbabwe: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health 2022;21:42. 10.1186/s12939-022-01646-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinkerhoff DW. Unpacking the concept of political will to confront corruption. In: U4 Brief, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Post LANN, Raile ANW, Raile ED. Defining political will. Politics Policy 2010;38:653–76. 10.1111/j.1747-1346.2010.00253.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammergren L. Political will, constituency building, and public support in rule of law programs, 202. Center for Democracy and Governance Fax, 1998: 216–3232. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grindle MS, Thomas JW. Public choices and policy change: the political economy of reform in developing countries. Johns Hopkins Univ Pr, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green D. Why demanding ‘political will’is lazy and unproductive. In: Poverty to Power Blog, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reich MR. The politics of reforming health policies. Promot Educ 2002;9:138–42. 10.1177/175797590200900401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croke K. The origins of Ethiopia's primary health care expansion: the politics of state building and health system strengthening. Health Policy Plan 2021;35:1318–27. 10.1093/heapol/czaa095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koon AD, Hawkins B, Mayhew SH. Framing and the health policy process: a scoping review. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:801–16. 10.1093/heapol/czv128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones CM, Gautier L, Ridde V. A scoping review of theories and conceptual frameworks used to analyse health financing policy processes in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Policy Plan 2021;36:1197–214. 10.1093/heapol/czaa173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baum F, Townsend B, Fisher M, et al. Creating political will for action on health equity: practical lessons for public health policy actors. Int J Health Policy Manag 2020. 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.233. [Epub ahead of print: 05 Dec 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carbone G. Democratic demands and social policies: the politics of health reform in Ghana. J Mod Afr Stud 2011;49:381–408. 10.1017/S0022278X11000255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agyepong IA, Adjei S. Public social policy development and implementation: a case study of the Ghana National health insurance scheme. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:150–60. 10.1093/heapol/czn002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Usher KA. The politics of health care reform: a comparative analysis of South Africa, Sweden and Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pillay TD, Skordis-Worrall J. South African health financing reform 2000-2010: understanding the agenda-setting process. Health Policy 2013;109:321–31. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilson L, Doherty J, Lake S, et al. The SAZA study: implementing health financing reform in South Africa and Zambia. Health Policy Plan 2003;18:31–46. 10.1093/heapol/18.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basaza RK, O'Connell TS, Chapčáková I. Players and processes behind the National health insurance scheme: a case study of Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:357. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birungi C, Colbourn T. It's politics, stupid! a political analysis of the HIV/AIDS trust fund in Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res 2019;18:370–81. 10.2989/16085906.2019.1689148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koduah A, van Dijk H, Agyepong IA. Technical analysis, contestation and politics in policy agenda setting and implementation: the rise and fall of primary care maternal services from Ghana's capitation policy. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:323. 10.1186/s12913-016-1576-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zulu JM, Kinsman J, Michelo C, et al. Developing the National community health assistant strategy in Zambia: a policy analysis. Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:1–13. 10.1186/1478-4505-11-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shearer JC, Abelson J, Kouyaté B, et al. Why do policies change? Institutions, interests, ideas and networks in three cases of policy reform. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:1200–11. 10.1093/heapol/czw052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wisdom JP, Juma P, Mwagomba B, et al. Influence of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control on tobacco legislation and policies in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2018;18:954. 10.1186/s12889-018-5827-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loewenson R, Godt S, Chanda-Kapata P. Asserting public health interest in acting on commercial determinants of health in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from a discourse analysis. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e009271. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milsom P, Smith R, Modisenyane SM, et al. Does international trade and investment liberalization facilitate corporate power in nutrition and alcohol policymaking? Applying an integrated political economy and power analysis approach to a case study of South Africa. Global Health 2022;18:32. 10.1186/s12992-022-00814-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kruger P, Abdool Karim S, Tugendhaft A, et al. An analysis of the adoption and implementation of a sugar-sweetened beverage Tax in South Africa: a multiple streams approach. Health Syst Reform 2021;7:e1969721. 10.1080/23288604.2021.1969721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koduah A, Gyansa-Lutterodt M, Hedidor GK, et al. Antimicrobial resistance national level dialogue and action in Ghana: setting and sustaining the agenda and outcomes. One Health Outlook 2021;3:18. 10.1186/s42522-021-00051-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCollum R, Theobald S, Otiso L, et al. Priority setting for health in the context of devolution in Kenya: implications for health equity and community-based primary care. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:729–42. 10.1093/heapol/czy043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider H, Mukinda F, Tabana H, et al. Expressions of actor power in implementation: a qualitative case study of a health service intervention in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:207. 10.1186/s12913-022-07589-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parkhurst J, Ghilardi L, Webster J, et al. Competing interests, clashing ideas and institutionalizing influence: insights into the political economy of malaria control from seven African countries. Health Policy Plan 2021;36:35–44. 10.1093/heapol/czaa166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bertone MP, Wurie H, Samai M, et al. The bumpy trajectory of performance-based financing for healthcare in Sierra Leone: agency, structure and frames shaping the policy process. Global Health 2018;14:99. 10.1186/s12992-018-0417-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witter S, Chirwa Y, Chandiwana P, et al. The political economy of results-based financing: the experience of the health system in Zimbabwe. Glob Health Res Policy 2019;4:20. 10.1186/s41256-019-0111-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Widdig H, Tromp N, Lutwama GW, et al. The political economy of priority-setting for health in South Sudan: a case study of the health pooled fund. Int J Equity Health 2022;21:1–16. 10.1186/s12939-022-01665-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kolie D, Delamou A, van de Pas R, et al. 'Never let a crisis go to waste': post-Ebola agenda-setting for health system strengthening in guinea. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001925. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daire J, Kloster MO, Storeng KT. Political priority for abortion law reform in Malawi: transnational and national influences. Health Hum Rights 2018;20:225–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fischer SE, Strandberg-Larsen M. Power and agenda-setting in Tanzanian health policy: an analysis of stakeholder perspectives. Int J Health Policy Manag 2016;5:355–63. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coulibaly A. Performance-Based Financing (PBF) in Mali: is it legitimate to speak of the emergence of a public health policy? International Development Policy; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walker L, Gilson L. 'We are bitter but we are satisfied': nurses as street-level bureaucrats in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1251–61. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaede BM. Doctors as street-level bureaucrats in a rural hospital in South Africa. Rural Remote Health 2016;16:3461. 10.22605/RRH3461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dzambo T. Discretion among street level bureaucrats: a case study of nurses in a public hospital in Cape town; 2014.

- 64.Penn-Kekana L, Blaauw D, Schneider H. 'It makes me want to run away to Saudi Arabia': management and implementation challenges for public financing reforms from a maternity ward perspective. Health Policy Plan 2004;19 Suppl 1:i71–7. 10.1093/heapol/czh047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Atinga RA, Agyepong IA, Esena RK. Ghana's community-based primary health care: Why women and children are 'disadvantaged' by its implementation. Soc Sci Med 2018;201:27–34. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Béland D, Ridde V. Ideas and policy implementation: understanding the resistance against free health care in Africa. 10. Global Health Governance, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lehmann U, Gilson L. Actor interfaces and practices of power in a community health worker programme: a South African study of unintended policy outcomes. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:358–66. 10.1093/heapol/czs066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen J, Ssennyonjo A, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Does decentralization of health systems translate into decentralization of authority? A decision space analysis of Ugandan healthcare facilities. Health Policy Plan 2021;36:1408–17. 10.1093/heapol/czab074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seddoh A, Akor SA. Policy initiation and political levers in health policy: lessons from Ghana’s health insurance. BMC Public Health 2012;12. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-S1-S10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abiiro GA, McIntyre D. Universal financial protection through national health insurance: a stakeholder analysis of the proposed one-time premium payment policy in Ghana. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:263–78. 10.1093/heapol/czs059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abiiro GA, Alatinga KA, Yamey G. Why did Ghana's National health insurance capitation payment model fall off the policy agenda? A regional level policy analysis. Health Policy Plan 2021;36:869–80. 10.1093/heapol/czab016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imurana Braimah A, Braimah AI. On the politics of lockdown and lockdown politics in Africa: COVID-19 and partisan expedition in Ghana. JPSIR 2020;3:44–55. 10.11648/j.jpsir.20200303.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mukuru M, Kiwanuka SN, Gilson L, et al. "The Actor Is Policy": Application of Elite Theory to Explore Actors’ Interests and Power Underlying Maternal Health Policies in Uganda, 2000-2015. Int J Health Policy Manag 2020. 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nyawira L, Mbau R, Jemutai J, et al. Examining health sector stakeholder perceptions on the efficiency of County health systems in Kenya. PLOS Glob Public Health 2021;1:e0000077. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lavers T. Towards Universal Health Coverage in Ethiopia's 'developmental state'? The political drivers of health insurance. Soc Sci Med 2019;228:60–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sieleunou I, Turcotte-Tremblay A-M, Fotso J-CT, et al. Setting performance-based financing in the health sector agenda: a case study in Cameroon. Global Health 2017;13:52. 10.1186/s12992-017-0278-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harding R. Who is democracy good for? Elections, rural bias, and health and education outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. J Polit 2020;82:241–54. 10.1086/705745 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nannini M, Biggeri M, Putoto G. Health coverage and financial protection in Uganda: a political economy perspective. Int J Health Policy Manag 2021. 10.34172/ijhpm.2021.116. [Epub ahead of print: 29 Aug 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fusheini A, Marnoch G, Gray AM. Stakeholders perspectives on the success drivers in Ghana's National Health Insurance Scheme - identifying policy translation issues. Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;6:273–83. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reichenbach L. The politics of priority setting for reproductive health: breast and cervical cancer in Ghana. Reprod Health Matters 2002;10:47–58. 10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00093-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prata N, Summer A. Assessing political priority for reproductive health in Ethiopia. Reprod Health Matters 2015;23:158–68. 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]