Abstract

Background

Chronic low back pain is a common musculoskeletal disease. With the increasing number of patients, it has become a huge economic and social burden. It is urgent to relieve the burden of patients. There are many common rehabilitation methods, and aquatic physical therapy is one of them. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to summarize the existing literature and analyze the impact of aquatic physical therapy on pain intensity, quality of life and disability of patients with chronic low back pain.

Methods

Through 8 databases, we searched randomized controlled trials on the effect of aquatic physical therapy on patients with chronic low back pain. These trials published results on pain intensity, quality of life, and disability. This review is guided by Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The level of evidence was assessed through GRADE.

Results

A total of 13 articles involving 597 patients were included. The results showed that compared with the control group, aquatic physical therapy alleviated the pain intensity (Visual Analogue Scale: SMD = -0.68, 95%CI:-0.91 to -0.46, Z = 5.92, P < 0.00001) and improved quality of life (physical components of 36-Item Short Form Health Survey or Short-Form 12: SMD = 0.63, 95%CI:0.36 to 0.90, Ζ = 4.57, P < 0.00001; mental components of 36-Item Short Form Health Survey or Short-Form 12: SMD = 0.59, 95%CI:0.10 to 1.08, Ζ = 2.35, P = 0.02), and reduced disability (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire: SMD = -0.42, 95%CI:-0.66 to -0.17, Ζ = 3.34, P = 0.0008; Oswestry Disability Index or Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire: SMD = -0.54, 95%CI:-1.07 to -0.01, Ζ = 1.99, P = 0.05). However, aquatic physical therapy did not improve patients' pain at rest (Visual Analogue Scale at rest: SMD = -0.60, 95%CI:-1.42 to 0.23, Ζ = 1.41, P = 0.16). We found very low or low evidence of effects of aquatic physical therapy on pain intensity, quality of life, and disability in patients with chronic low back pain compared with no aquatic physical therapy.

Conclusions

Our systematic review showed that aquatic physical therapy could benefit patients with chronic low back pain. However, because the articles included in this systematic review have high bias risk or are unclear, more high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to verify.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12891-022-05981-8.

Keywords: Chronic low back pain, Aquatic physical therapy, Pain intensity, Quality of life, Disability

Background

Chronic low back pain was defined as back pain with or without leg pain for more than 12 weeks between the lower ribs and the folds above the buttocks [1]. Chronic low back pain is a common and increasing skeletal muscle disease [2]. Maher describes back pain syndrome as a major health problem with huge economic and social costs, as more than 80% of health care costs go to patients with the disease [3]. Therefore, it is very important to relieve the pain intensity and disability of patients with chronic low back pain and improve their quality of life.

The treatment of chronic low back pain is still in constant exploration. Scaturro et al. [4] have observed the effect of combination of rehabilitative therapy with ultramized palmitoylethanolamide on patients with chronic low back pain. The results showed that the pain intensity and disability of patients were relieved, and the quality of life was improved. However, Guidelines for the management of patients with chronic low back pain still recommend exercise therapy as a first-line treatment to reduce pain intensity and disability [5]. Among them, aquatic physical therapy is particularly interesting, and one of the methods in rehabilitation treatment recently [6]. Aquatic physical therapy (APT) is defined as exercising in water, or using the characteristics of water to relieve pain intensity, relax muscles and promote better exercise, it includes hydrotherapy and aquatic exercise [7]. Silva et al. previously reported the positive effect of hydrotherapy on the management of patients with knee osteoarthritis [8]. Pérez-de et al. also reported the positive effects of aquatic physical therapy on patients with chronic stroke [9]. Previously, Shi et al. [10] have done a systematic review to analyze the impact of aquatic exercise on patients with chronic low back pain. This article analyzed the impact of aquatic exercise on patients' pain intensity and quality of life. Later, new randomized controlled trials were published, and these articles were not included in the analysis. But in this article, newly published randomized controlled trials was included to analyzed not only the impact of aquatic physical therapy on pain intensity and quality of life of patients with chronic low back pain, but also the impact on disability of patients. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to summarize and analyze the articles about the impact of aquatic physical therapy on patients with chronic low back pain, and to analyze the effectiveness of aquatic physical therapy on pain intensity, quality of life, and disability of patients with chronic low back pain.

Methods

This systematic review protocol has been registered on PROSPERO as CRD42021265891. The methods was conducted according to the method described in the Cochrane Handbook [11], and the reporting was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. (Appendix 1).

Search strategy

We searched 8 databases, including: PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Web of science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang data, Chongqing VIP (CQVIP), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM). There are no restrictions on languages and countries, the search date is from the beginning to July 15, 2022. The following terms were used for retrieval: 'low back pain,' 'aquatic exercise,' 'aquatic therapy,' 'hydrotherapy'.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of study

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are based on PICOS standards: see Table 1 for specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients diagnosed with chronic low back pain | Patients with other serious systemic diseases |

| Interventions | APT or APT + other interventions (APT group) | No APT intervention |

| Comparisons | Other interventions: such as land based exercise, health education, physical therapy, no exercise, etc. (No APT group) | With APT intervention |

| Outcomes | Include at least one of the following outcome indicators: pain intensity (VAS, NPRS, NRS etc.); quality of life (SF-36, SF-12 etc.); disability (ODI, ODQ, RMDQ etc.). The analysis results include the short-term (< 12 weeks), medium-term (12–48 weeks) and long-term (> 48 weeks) effects of APT on patients with chronic low back pain | The literature does not contain the outcome indicators of inclusion criteria |

| Study | Randomized controlled trial; Published in English or Chinese | Non randomized controlled trial |

Note: APT Aquatic Physical Therapy, VAS Visual Analogue Scale, NPRS Numeric Pain Rating Scale, NRS Numeric Rating Scale, SF-36 Quality Short-Form 36 Health Survey, SF-12 Short-Form 12, ODI Oswestry Disability Index, ODQ Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, RMDQ Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire

Study selection

Two researchers independently checked the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies and downloaded those that might meet the requirements. By reading the full text, the eligible studies were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process was completed by two reviewers, and a third reviewer was sought for discussion to resolve disagreements.

Data extraction

Two reviewers checked eligible studies and extracted characteristics of included studies, including: the first author, year, country of study, the sample size of the intervention group, the sample size of the control group, the type of exercise in the intervention group, the type of exercise in the control group, intervention time, follow-up time, and outcomes measures.

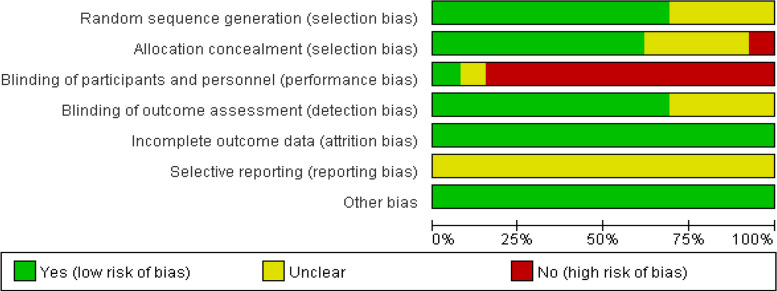

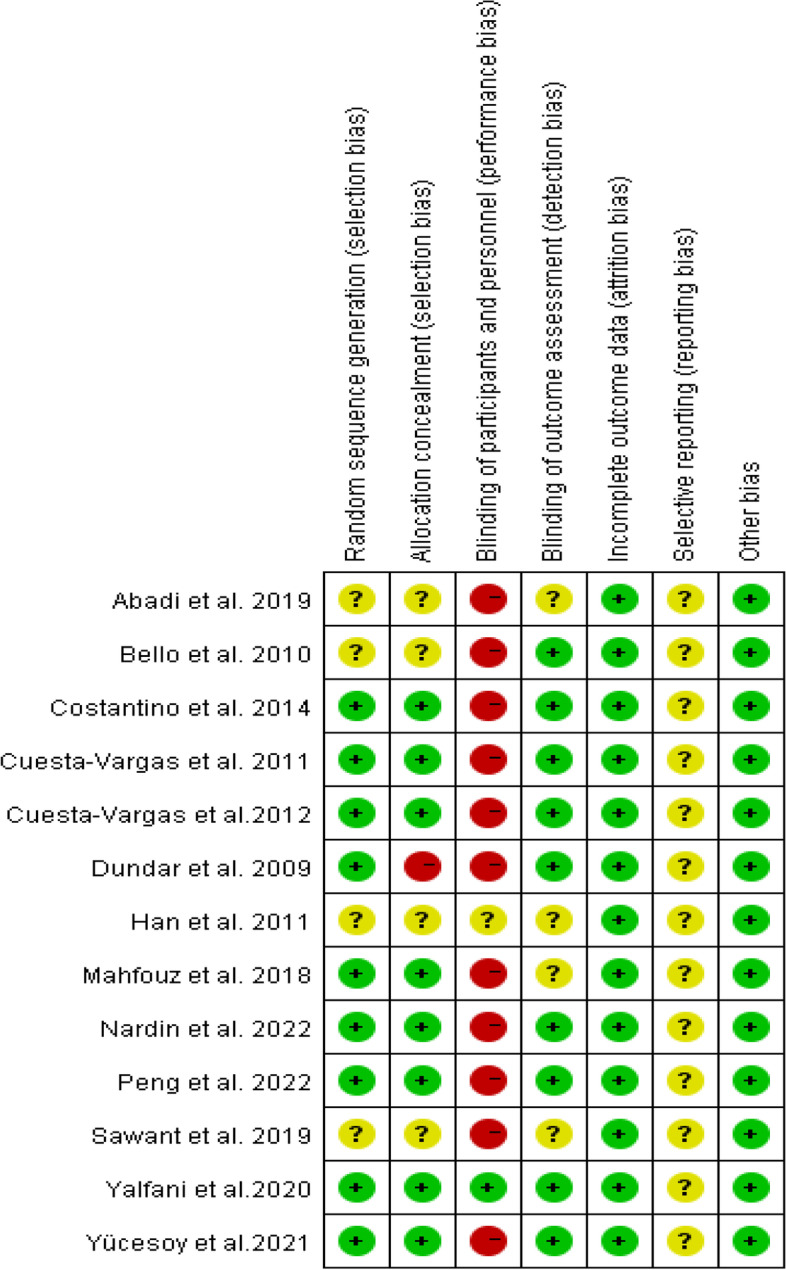

Assessment of risk of bias

The quality of the literature was evaluated by two independent people using Cochrane bias risk assessment tool [11] respectively. If there are differences, they should be resolved through discussions with a third reviewer. This tool evaluates the bias of randomized controlled trials in seven aspects: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias.

Data synthesis

Meta-analysis was conducted on the same result variable of more than two groups of data. If the mean and standard deviation cannot be directly obtained, the relevant data shall be converted according to the evidence-based medicine conversion formula [13]. The results of data synthesis are presented in the form of forest maps.

Statistical analysis

We use RevMan (version 5.3) software to analyze the data. Mean ± SD was used as the effect index for continuous variables, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were given for all variables, if the same research tool is used in the included literature, the mean difference (MD) analysis is used. If different research tools are used, the standardized mean difference (SMD) analysis is used. We used Cochran's Q statistic and Ι2 statistic to test the heterogeneity of the included articles. If Ι2 > 50%, we think there is heterogeneity between articles, and use random effect model for statistical analysis. If Ι2 < 50%, the heterogeneity between articles was considered acceptable, and the fixed effect model was used for statistical analysis [14]. Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis were used to analyze the source of results heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was carried out by eliminating each study one by one. Use Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) to rate the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low. Trials were grouped according to VAS, VAS subscale, SF-36 or SF-12 subscale, RMDQ, ODI, or ODQ.

Results

Literature search

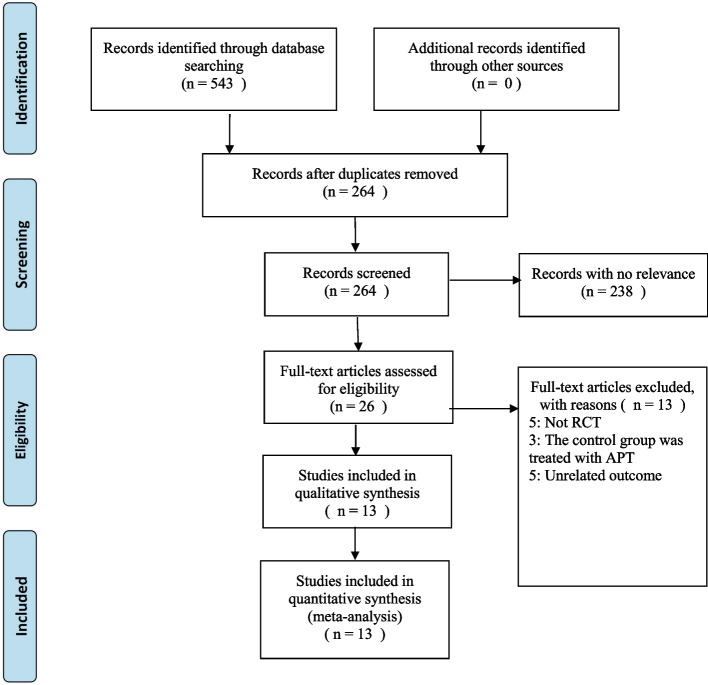

We used the search strategy to search 543 articles in the database. After excluding the repetitive literatures, we read the titles and abstracts of the remaining literatures, and selected 26 literatures to read the full text. Five non randomized controlled trial was excluded, three in the control group also used aquatic physical therapy, and five articles have unrelated outcome. Finally, 13 articles were confirmed to meet the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 summarizes the literature screening process at the end of the article.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of selection of studies

Study characteristics

This paper includes 13 articles, and the basic characteristics of each article are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| First Author, Year | Country of study | Intervention group(Sample Size) | Control group(Sample Size) | Intervention group (Type of exercise) | Control group (Type of exercise) | Intervention time | Follow up time | Outcomes measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abadi et al. 2019 [15] | Sultan | 19 | 20 | aquatic exercise | physiotherapy exercise + no exercise | 60 min 2 × /wk 12wks | —— | modified Oswestry questionnaire |

| Bello et al. 2010 [16] | Ghana | 6 | 6 | water-based exercises | land-based exercises | 45-60 min 2 × /wk 6wks | —— | Pain: VAS; Trunk flexibility: MSFT,MSET |

| Costantino et al. 2014 [17] | Italy | 27 | 27 | hydrotherapy | physiotherapy treatment | 60 min 2 × /wk 12wks | 3mons | RMDQ;SF-36 |

| Cuesta-Vargas et al. 2011 [18] | Spain | 23 | 23 | MMPTP + DWR | MMPTP | 60 min 3 × /wk 15wks | —— | pain: VAS; disability: RMDQ; general health:SF-12; physical function: MISL test, dual inclinometer, Biering Sorensen test |

| Cuesta-Vargas et al. 2012 [19] | Spain | 25 | 24 | GP + DWR | GP | 30 min 3 × /wk 16wks | 48wks | pain: VAS; disability: RMDQ; general health: SF-12 |

| Dundar et al. 2009 [20] | Turkey | 32 | 33 | aquatic exercise | land-based exercise | 60 min 5 × /wk 4wks | 12wks | spinal mobility: modified Schober test; lumbal flexion/extension and rotation: inclinometer, goniometer; pain: VAS; disability: MOLBDQ; quality of life:SF-36 |

| Han et al. 2011 [21] | Korea | 9 | 10 | aquatic exercise | no exercise | 50 min 5 × /wk 10wks | —— | VAS; muscle strength |

| Mahfouz et al. 2018 [22] | Egypt | 20 | 20 | aquatic therapy | conventional physical therapy | 60 min 6wks | —— | pain: VAS; Disability: ODI; lumbar flexion; Lumbar extension |

| Nardin et al. 2022 [23] | Brazil | 20 | 20 | PBM + DWR | PBM | 65 min 2 × /wk 4wks | —— | IPAQ-SF; ODI; VAS; 6-min walk test cortisol level; creatine kinase levels |

| Peng et al. 2022 [24] | China | 56 | 57 | therapeutic aquatic exercise | Physical therapy modalities | 60 min 2 × /wk 12wks | 12mons | RMDQ; NRS; SF-36; SAS; SDS; PSQI; PASS; TSK; FABQ |

| Sawant et al. 2019 [25] | India | 15 | 15 | hydrotherapy | conventional therapy | —— | —— | VAS; MODI |

| Yalfani et al. 2020 [26] | Iran | 12 | 12 | water pilates | mat pilates | 75 min 3 × /wk 8wks | —— | pain: VAS; disability: ODQ; balance: BBS |

| Yücesoy et al. 2021 [27] | Turkey | 33 | 33 | balneological + home exercise | home exercise | 40 min 5 × /wk 2wks | 3mons | pain: VAS, ODI; PGA; DGA; FFD; modified Schober test; SF-36 |

Note: VAS Visual Analogue Scale, MSFT Modified Schober Flexion Technique, MSET Modified Schober Extension Technique, RMDQ Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, SF-36 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, MMPTP Multimodal Physical Therapy Program, DWR Deep-Water Running, SF-12 Short-Form 12, MISL Maximum Isometric Strength of Lumbar, GP General practice, MOLBDQ The modifified Oswestry low back disability questionnaire, ODI Oswestry Disability Index, PBM Photobiomodulation therapy, IPAQ-SF International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form, NRS Numeric Rating Scale, SAS Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, SDS Zung Self-rating Depression Scale, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PASS Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale, TSK Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia, FABQ Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, MODI Modified Oswestry Disability Index, ODQ Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, BBS Biodex Balance System, PGA Patient’s global assessment, DGA physician’s global assessment, FFD finger-to-floor distance

Risk of bias assessment

For details of bias risk assessment, see Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias summary

Effects of interventions

APT VS No APT (short-term effects)

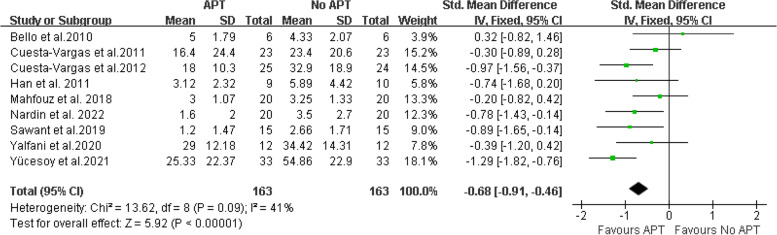

Pain intensity Nine studies [16, 18, 19, 21–23, 25–27] provided data on VAS and were included in the meta-analysis. The final results showed that compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy significantly reduced the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain (SMD = -0.68, 95%CI:-0.91 to -0.46, Z = 5.92, P < 0.00001, Ι2 = 41%, Fixed Effect Model). (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

APT VS No APT, VAS

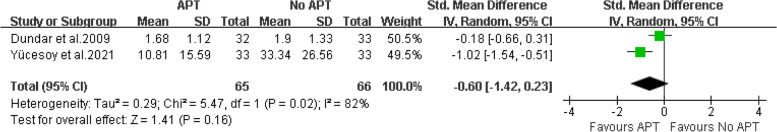

There are two articles [20, 27] that provide data of VAS at rest. The final results showed that compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy no significantly reduced the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain at rest (SMD = -0.60, 95%CI:-1.42 to 0.23, Ζ = 1.41, P = 0.16, Ι2 = 82%, Random Effect Model).( Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

APT VS No APT, VAS at rest

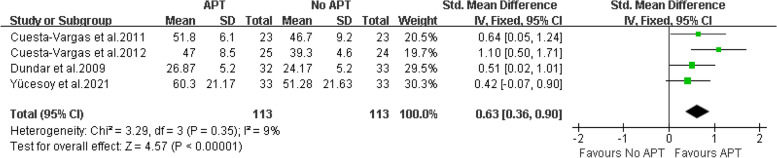

Quality of life Four articles [18–20, 27] provide data on the physical components of patients with chronic low back pain treated with aquatic physical therapy. Two articles are provided by SF-36, and two articles are provided by SF-12. Therefore, SMD combined effect quantity is adopted. The final results showed that compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the physical condition of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.36 to 0.90, Ζ = 4.57, P < 0.00001, Ι2 = 9%, Fixed Effect Model). (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

APT VS No APT, physical components of quality of life

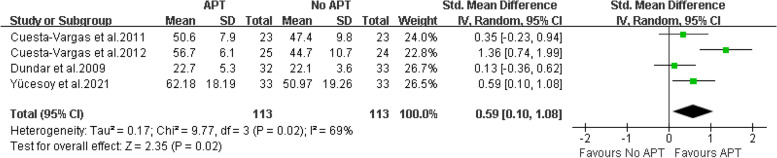

Four articles [18–20, 27] provide data on the mental components of patients with chronic low back pain treated with aquatic physical therapy. Two articles are provided by SF-36, and two articles are provided by SF-12. Therefore, SMD combined effect quantity is adopted. Sensitivity analysis found that the heterogeneity decreased from 69% to 0% after deleting one article, this may be due to different assessment tools and different intervention plans [19]. Because the outcome effect was the same, the study by Cuesta-Vargas AI et al. was included in the analysis. The final results showed that compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the mental condition of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.10 to 1.08, Ζ = 2.35, P = 0.02, Ι2 = 69%, Random Effect Model). (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

APT VS No APT, mental components of quality of life

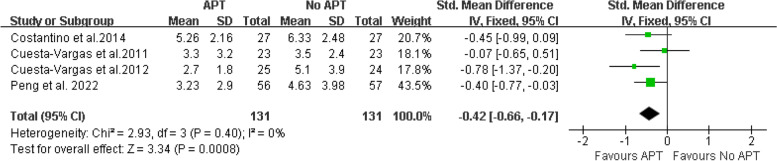

Disability Four articles [17–19, 24] provided RMDQ scores. The final results showed that compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the disability of patients with chronic low back pain (SMD = -0.42, 95%CI:-0.66 to -0.17, Ζ = 3.34, P = 0.0008, Ι2 = 0%, Fixed Effect Model). (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

APT VS No APT, RMDQ

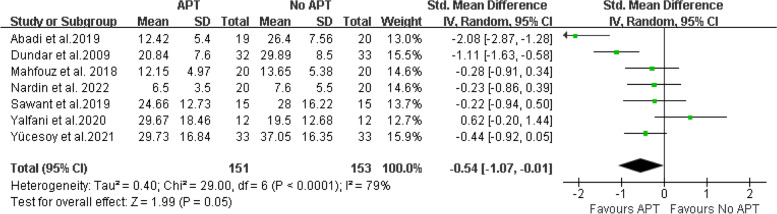

Seven articles [15, 20, 22, 23, 25–27] provide ODI or ODQ. The final results showed that compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the disability of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = -0.54, 95%CI:-1.07 to -0.01, Ζ = 1.99, P = 0.05, Ι2 = 79%, Random Effect Model) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

APT VS No APT, ODI or ODQ

Subgroup analysis (APT VS No APT at follow, medium-term effects)

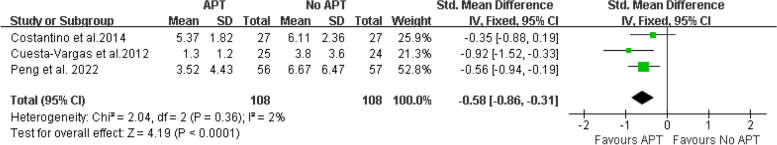

Disability Three articles [17, 19, 24] provided RMDQ scores at follow. At follow, compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the disability of patients with chronic low back pain (SMD = -0.58, 95%CI:-0.86 to -0.31, Ζ = 4.19, P < 0.0001, Ι2 = 2%, Fixed Effect Model). (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

APT VS No APT, RMDQ at follow

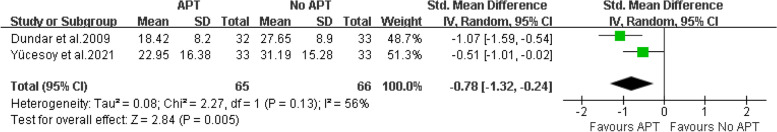

Two articles [20, 27] provided ODI or ODQ scores at follow. At follow, compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the disability of patients with chronic low back pain (SMD = -0.78, 95%CI:-1.32 to -0.24, Ζ = 2.84, P = 0.005, Ι2 = 56%, Random Effect Model). (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

APT VS No APT, ODI or ODQ at follow

Subgroup analysis (APT VS land based exercise, short-term effects)

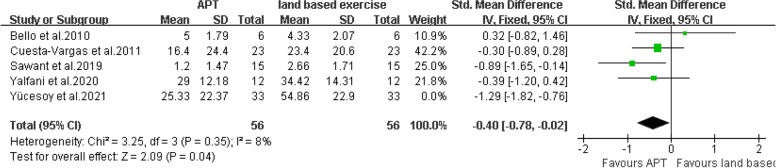

Pain intensity There are five articles [16, 18, 25–27] that provided VAS scores. The final results showed that compared with land based exercise, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = -0.40, 95%CI:-0.78 to -0.02, Ζ = 2.09, P = 0.04, Ι2 = 8%, Fixed Effect Model) (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

APT VS land based exercise, VAS

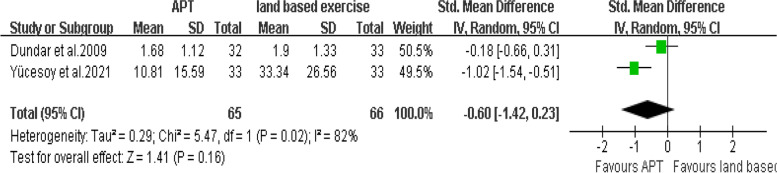

There are two articles [20, 27] that provided VAS at rest scores. The final results showed that compared with land based exercise, aquatic physical therapy no significantly improved the pain intensity at rest of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = -0.60, 95%CI:-1.42 to 0.23, Ζ = 1.41, P = 0.16, Ι2 = 82%, Random Effect Model) (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

APT VS land based exercise, VAS at rest

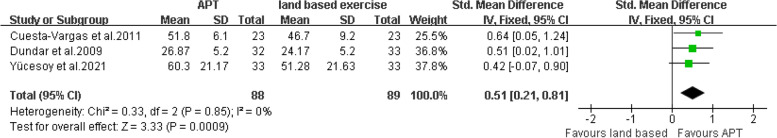

Quality of life There are three articles [18, 20, 27] that provided physical components scores. The final results showed that compared with land based exercise, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the physical condition of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = 0.51, 95%CI:0. 21 to 0.81, Ζ = 3.33, P = 0.0009, Ι2 = 0%, Fixed Effect Model) (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14.

APT VS land based exercise, physical components of quality of life

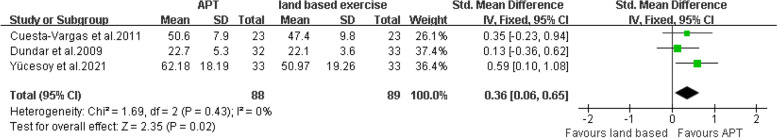

There are three articles [18, 20, 27] that provided mental components scores. The final results showed that compared with land based exercise, aquatic physical therapy significantly improved the mental condition of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = 0.36, 95% CI:0.06 to 0.65, Ζ = 2.35, P = 0.02, Ι2 = 0%, Fixed Effect Model).( Fig. 15).

Fig. 15.

APT VS land based exercise, mental components of quality of life

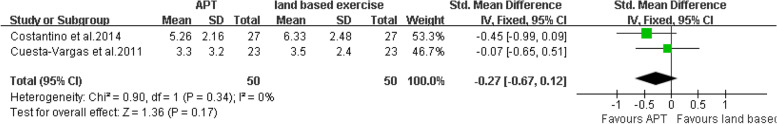

Disability There are two articles [17, 18] that provided RMDQ scores. The final results showed that compared with land based exercise, aquatic physical therapy no significantly improved the disability of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = -0.27, 95%CI:-0.67 to 0.12, Ζ = 1.36, P = 0.17, Ι2 = 0%, Fixed Effect Model) (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16.

APT VS land based exercise, RMDQ

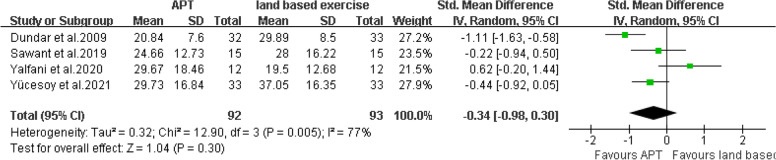

There are four articles [20, 25–27] that provided ODI or ODQ scores. The final results showed that compared with land based exercise, aquatic physical therapy no significantly improved the disability of patients with chronic low back pain. (SMD = -0.34, 95%CI:-0.98 to 0.30, Ζ = 1.04, P = 0.30, Ι2 = 77%, Random Effect Model) (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17.

APT VS land based exercise, ODI or ODQ

Publication bias

As there were no more than 10 included literatures for each outcome, publication bias was not performed.

Certainty of evidence

For the evidence quality of the measured results, see Table 3 for details.

Table 3.

GRADE evidence profile of the effect of aquatic physical therapy on chronic low back pain

| Certainty assessment | number of patients | Effect | Certainty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | APT | No APT | Absolute (95% CI) | |

| VAS | ||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized trials | serious1 | not serious2 | not serious3 | serious4 | none5 | 163 | 163 | SMD:-0.68 (-0.91, -0.46) | ⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

| VAS at rest | ||||||||||

| 2 | Randomized trials | serious1 | serious6 | not serious3 | serious4 | none5 | 65 | 66 | SMD: -0.60 (-1.42, 0.23) | ⊕ ◯◯◯ Very Low |

| physical components of SF-36 or SF-12 | ||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials | serious1 | not serious7 | not serious3 | serious4 | none5 | 113 | 113 | SMD: 0.63 (0.36, 0.90) | ⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

| mental components of SF-36 or SF-12 | ||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials | serious1 | serious8 | not serious3 | serious4 | none5 | 113 | 113 | SMD: 0.59 (0.10, 1.08) | ⊕ ◯◯◯ Very Low |

| RMDQ | ||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials | serious1 | not serious9 | not serious3 | serious4 | none5 | 131 | 131 | SMD: -0.42 (-0.66, -0.17) | ⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

| ODI or ODQ | ||||||||||

| 7 | Randomized trials | serious1 | serious10 | not serious3 | serious4 | none5 | 151 | 153 | SMD: -0.54 (-1.07, -0.01) | ⊕ ◯◯◯ Very Low |

VAS Visual Analogue Scale, SF-36 Quality Short-Form 36 Health Survey, SF-12 Short-Form 12, RMDQ Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, ODI Oswestry Disability Index, ODQ Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire

1We downgraded the quality of the evidence for risk of bias by one level. All included studies were at high or unclear risk of bias

2We did not downgrade for inconsistency, I2 = 41% and χ2 = 13.62, P = 0.09

3Although the studies included different types of interventions, we did not downgrade for indirectness

4We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one level because the population size was less than 400 people

5We did not downgrade publication bias, although we could not reliably assess this category due to the small number of eligible studies

6We did downgrade for inconsistency, I2 = 82% and χ2 = 5.47, P = 0.02

7We did not downgrade for inconsistency, I2 = 9% and χ2 = 3.29, P = 0.35

8We did downgrade for inconsistency, I2 = 69% and χ2 = 9.77, P = 0.02

9We did not downgrade for inconsistency, I2 = 0% and χ2 = 2.93, P = 0.40

10We did downgrade for inconsistency, I2 = 79% and χ2 = 29.00, P < 0.0001

Discussion

This meta-analysis summarizes in detail the effects of aquatic physical therapy on pain intensity, quality of life, and disability in patients with chronic low back pain. In this meta-analysis, we included 13 randomized controlled trials. The results showed that compared with no aquatic physical therapy, aquatic physical therapy can reduce pain intensity, improve quality of life and disability of patients in the short-term.

Pain is the main symptom of patients with chronic low back pain. A VAS was used to assess the patient's pain intensity [28]. It was evaluated as an effective, reliable and responsive technique for pain intensity assessment [16]. In this review, the overall results show that, it can be considered that there is statistical difference, and aquatic physical therapy can relieve the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain in the short-term. This result was confirmed in subgroup analysis. In addition, another meta-analysis also showed that there was a positive correlation between aquatic physical therapy and pain intensity relief, aquatic physical therapy can significantly reduce the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain [10]. There are two studies [20, 27] giving the VAS score at rest. But it not can be considered that aquatic physical therapy can relieve the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain at rest in the short-term. In addition, in subgroup analyses, the VAS at rest scores also was not statistically significant for aquatic physical therapy compared with land based exercise. The reason for this result may be that too few studies were included in the analysis, resulting in bias in the results.

The quality of life was assessed by short form 36 health survey or short form 12 health survey. SF-36 or SF-12 can detect the health changes of the general population. It is a simple and cheap method to measure the health results. It is a continuous ruler to detect the health changes. However, in this review, because other aspects of the data can’t be summarized, we only analyzed the effect on the physical component and mental component. On the physical component and mental component, it can be considered that aquatic physical therapy can improve the physical and mental condition of patients with chronic low back pain in the short-term. This result was confirmed in subgroup analysis. Aquatic physical therapy can help patients relieve their physical and psychological burden.

Low back pain has an impact on a patient's disability because pain limits its activity [29]. Disability was assessed by RMDQ, ODI, ODQ. RMDQ, ODI, ODQ are the three most commonly used scales to assess disability in patients with chronic low back pain [30]. In RMDQ, ODI or ODQ, meta-analysis showed that compared with the control group, the intervention group showed statistically significant, and aquatic physical therapy can improve the disability of patients with chronic low back pain in the short-term. This may be because aquatic physical therapy alleviates the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain, thus reducing the impact of pain on the disability of patients, thus improving the disability of patients. However, in the comparison between aquatic physical therapy and land based exercise, the disability of patients was not improved, which may be due to the different intervention protocols included in the studies and the low number of included studies. In addition, subgroup analyses showed that aquatic physical therapy improved disability compared with no aquatic physical therapy in the medium-term.

Aquatic physical therapy is often used as a rehabilitation therapy for patients with musculoskeletal diseases [31]. Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of aquatic physical therapy [32]. And, the current study included trials related to aquatic physical therapy in patients with chronic low back pain. The results also showed that aquatic physical therapy was effective for patients with chronic low back pain. It is proved that aquatic physical therapy can effectively relieve the pain intensity of patients with chronic low back pain, improve the quality of life and functional ability. It may provide reference for medical staff to make exercise plan for patients with chronic low back pain.

This systematic review included the latest studies for meta-analysis, including 13 randomized controlled trials, while the recently published systematic review only included 8 studies. In addition, this systematic review analyzed the short-term and medium-term effects of aquatic physical therapy on patients with chronic low back pain. However, this review still has some limitations. First, some outcome indicators are measured with different research tools, and there may be measurement bias. Secondly, the modified Jadad tool was planned to be used to evaluate the quality of the included studies at the initial registered protocol. Later, we was considered that the Cochrane bias risk assessment tool was domain-based evaluation. In addition, it requires the evaluation results of each risk bias to have specific judgment reasons and achieve transparency [33].Therefore, we finally used the Cochrane bias risk assessment tool to evaluate the quality of the included studies. Thirdly, researchers should explore the long-term effects of aquatic physical therapy on patients with chronic low back pain. Finally, this review cannot determine the best intervention time and intensity of intervention measures.

Conclusions

Aquatic physical therapy may be effective and safe in improving pain intensity, quality of life and functional ability in patients with chronic low back pain. Aquatic physical therapy can provide some reference for patients with chronic low back pain when making exercise plans, and encourage patients to carry out aquatic physical therapy. However, more high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to verify the effectiveness and safety of aquatic physical therapy.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1. PRISMA check list. Appendix 2. Search strategy for Pubmed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dean Qin and Lijun Li for their assistance with this study.

Abbreviations

- APT

Aquatic physical therapy

- No APT

No aquatic physical therapy

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- CQVIP

Chongqing VIP

- CBM

Chinese Biomedical Literature Database

- CI

Confidence intervals

- MD

Mean difference

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

Authors’ contributions

QZ and HYC conceived and designed the article. QZ, HYC and XL screened the literature, extracted the data and evaluated the quality of the included literature. JM, TZ and YPH analyzed the data and wrote papers. Each author agrees with the final version of the article submitted. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specifc grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-proft sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ji Ma, Teng Zhang and Yapeng He contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ji Ma, Email: Majisxty@163.com.

Teng Zhang, Email: zhangteng0622@163.com.

Yapeng He, Email: heyapeng0111@163.com.

Xin Li, Email: lx99728@126.com.

Haoyang Chen, Email: chenhaoyangy@126.com.

Qian Zhao, Email: zhaoqian_sara@126.com.

References

- 1.Know I, Pain A, Physiology B, Cephalic C, Investigating I. Core Curriculum for Professional Education in Pain, edited by J. Edmond Charlton,. Epidemiology. 2005;16:1–2.

- 2.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, Jackman AM, Darter JD, Wallace AS, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):251–258. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maher CG. Effective physical treatment for chronic low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scaturro D, Asaro C, Lauricella L, Tomasello S, Varrassi G, Mauro GL. Combination of rehabilitative therapy with ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide for chronic low back pain: an observational study. Pain Ther. 2020;9(1):319–326. doi: 10.1007/s40122-019-00140-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J, Klaber Moffett J, Kovacs F, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl 2):S192–300. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camilotti BM, Rodacki A, Israel VL, Fowler NE. Stature recovery after sitting on land and in water. Man Ther. 2009;14(6):685–689. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cimbiz A, Bayazit V, Hallaceli H, Cavlak U. The effect of combined therapy (spa and physical therapy) on pain in various chronic diseases. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13(4):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva LE, Valim V, Pessanha AP, Oliveira LM, Myamoto S, Jones A, et al. Hydrotherapy versus conventional land-based exercise for the management of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2008;88(1):12–21. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez-de la Cruz S. Influence of an aquatic therapy program on perceived pain, stress, and quality of life in chronic stroke patients a randomized trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Z, Zhou H, Lu L, Pan B, Wei Z, Yao X, et al. Aquatic exercises in the treatment of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of eight studies. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;97(2):116–122. doi: 10.1097/phm.0000000000000801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins J, Green S. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0; 2011.

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ming Liu, Hongmei Wu, Maoling Wei. Systematic review, meta-analysis design and implementation methods. People's Medical Publishing House; 2011.

- 14.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abadi FH, Sankaravel M, Zainuddin FF, Elumalai G, Razli AI. The effect of aquatic exercise program on low-back pain disability in obese women. J Exerc Rehabil. 2019;15(6):855–860. doi: 10.12965/jer.1938688.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bello AI, Kalu NH, Adegoke BOA, Agyepong-Badu S. Hydrotherapy versus land-based exercises in the management of chronic low back pain: A comparative study. J Musculoskelet Res. 2010;13(4):159–165. doi: 10.1142/S0218957710002594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costantino C, Romiti D. Effectiveness of Back School program versus hydrotherapy in elderly patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Acta Biomed. 2014;85(3):52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuesta-Vargas AI, Garcia-Romero JC, Arroyo-Morales M, Diego-Acosta AM, Daly DJ. Exercise, manual therapy, and education with or without high-intensity deep-water running for nonspecific chronic low back pain a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(7):526–534. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31821a71d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuesta-Vargas AI, Adams N, Salazar JA, Belles A, Hazañas S, Arroyo-Morales M. Deep water running and general practice in primary care for non-specific low back pain versus general practice alone: randomized controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(7):1073–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-1977-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dundar U, Solak O, Yigit I, Evcik D, Kavuncu V. Clinical effectiveness of aquatic exercise to treat chronic low back pain a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34(14):1436–1440. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a79618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han G, Cho M, Nam G, Moon T, Kim J, Kim S, et al. The effects on muscle strength and visual analog scale pain of aquatic therapy for individuals with low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2011;23(1):57–60. doi: 10.1589/jpts.23.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahfouz Marwa M, Sedhom Magda G, Essa Mohamed M, KamelRagia M, Yosry AH. Effect of aquatic versus conventional therapy in treatment of chronic low back pain. Int J Physiother. 2018;5:6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nardin DMK, Stocco MR, Aguiar AF, Machado FA, de Oliveira RG, Andraus RAC. Effects of photobiomodulation and deep water running in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;37(4):2135–2144. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng MS, Wang R, Wang YZ, Chen CC, Wang J, Liu XC, et al. Efficacy of therapeutic aquatic exercise vs physical therapy modalities for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawant RS, Shinde SB. Effect of hydrotherapy based exercises for chronic nonspecific low back pain [Academic Journal] Indian J Physiother Occu Ther. 2019;13(1):133–138. doi: 10.5958/0973-5674.2019.00027.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yalfani A, Raeisi Z, Koumasian Z. Effects of eight-week water versus mat pilates on female patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: Double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2020;24(4):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yücesoy H, Dönmez A, Atmaca-Aydın E, Yentür SP, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Ankaralı H, et al. Effects of balneological outpatient treatment on clinical parameters and serum cytokine levels in patients with chronic low back pain: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Int J Biometeorol. 2021;65(8):1367–1376. doi: 10.1007/s00484-021-02109-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiradejnant A, Maher CG, Latimer J, Stepkovitch N. Efficacy of "therapist-selected" versus "randomly selected" mobilisation techniques for the treatment of low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49(4):233–241. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delitto A, George SZ, Van Dillen L, Whitman JM, Sowa G, Shekelle P, et al. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;42(4):A1–57. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.42.4.A1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire and the quebec back pain disability scale. Phys Ther. 2001;81(2):776–788. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.2.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhagen AP, Cardoso JR, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Aquatic exercise & balneotherapy in musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waller B, Lambeck J, Daly D. Therapeutic aquatic exercise in the treatment of low back pain: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(1):3–14. doi: 10.1177/0269215508097856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma J, Liu Y, Zhong LP, Zhang CP, Zhang ZY. Comparison between Jadad scale and Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias on the quality and risk of bias evaluation in randomized controlled trials. China J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2012;10(05):417–422. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Appendix 1. PRISMA check list. Appendix 2. Search strategy for Pubmed.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.