Abstract

Microbial secondary infections can contribute to an increase in the risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients, particularly in case of severe diseases. In this study, we collected and evaluated the clinical, laboratory and microbiological data of COVID-19 critical ill patients requiring intensive care (ICU) to evaluate the significance and the prognostic value of these parameters. One hundred seventy-eight ICU patients with severe COVID-19, hospitalized at the S. Francesco Hospital of Nuoro (Italy) in the period from March 2020 to May 2021, were enrolled in this study. Clinical data and microbiological results were collected. Blood chemistry parameters, relative to three different time points, were analyzed through multivariate and univariate statistical approaches. Seventy-four percent of the ICU COVID-19 patients had a negative outcome, while 26% had a favorable prognosis. A correlation between the laboratory parameters and days of hospitalization of the patients was observed with significant differences between the two groups. Moreover, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Candida spp, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae were the most frequently isolated microorganisms from all clinical specimens. Secondary infections play an important role in the clinical outcome. The analysis of the blood chemistry tests was found useful in monitoring the progression of COVID-19.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10238-022-00959-1.

Keywords: SARS-COV-2 infection, COVID-19, Blood chemistry parameters, Microbiological data, Secondary infections, Clinical outcome

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 infection is the cause of COVID-19, a respiratory disease that can range from asymptomatic to symptomatic disease with severe pneumonia, inflammation and death [1, 2]. The clinical outcome and prognosis depend on various factors [3], including bacterial/viral/fungal co-infections or superinfections (secondary infections) which can increase the risk of mortality in these patients [4–7]

The importance of secondary infections during the COVID-19 pandemic has been somewhat investigated [8, 9] as they were reported to be associated with a decreased survival, playing a crucial role especially in those patients with a severe illness admitted to the ICU [10]. Several reports indicated an increased number of COVID-19 patients with secondary infections during hospitalization [11, 12]. SARS-CoV-2, like other respiratory viruses, weakens the host immunity, facilitating such infections [13], especially during hospitalization. While the specific source and nature of these infections have not been thoroughly investigated [5], some evidence suggests that nosocomial, often multidrug-resistant (MDR), pathogens, are likely responsible [10, 14]. The dramatic aspect of this scenario is that during this pandemic up to 50% of patients who died from COVID-19 had secondary infections [9, 15], likely related to the fact that critically ill hospitalized patients needed invasive mechanical ventilation for a prolong period and this rendered them susceptible to hospital-acquired infections [16]. Inflammatory chemical biomarkers and proper microbiological surveillance may be fundamental for the management of COVID-19 patients because they allow the early detection of markers which correlate with the presence of such infections and a negative outcome. Laboratory data are thus fundamental to support clinicians in monitoring the hospitalized patients and follow the clinical evolution of COVID-19 [17].

In this study, we collected the clinical, laboratory and microbiological data of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, admitted to the ICU from March 2020 to May 2021, to evaluate the significance and the prognostic value of these parameters [18].

Methods

COVID-19 patients, positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection (diagnosed through the extraction of RNA and reverse transcription Real-Time PCR) hospitalized in the ICU of the S. Francesco Hospital of Nuoro (Sardinia, Italy) in the period from March 2020 to May 2021 were enrolled in this study (n = 178). The three different phases of the pandemics were classified as follows: (i) March–May 2020; (ii) September–December 2020; and (ii) January–May 2021. The study was conducted in accordance with the current revision of the Helsinki Declaration.

By analyzing the medical records of 156 patients (22 records were not available), it was possible to collect information regarding the symptoms at the onset of the infection, the presence of risk factors and co-morbidities and the microbiological data. Moreover, blood chemistry parameters relative to three different time points were collected: (T0), sampling at the moment of the admission of the patient at the emergency room, the infectious diseases ward, or directly at the ICU; (T1), sampling between the admission day and the clinical outcome; and (T2), the last sampling before the transfer of the patient from the ICU to others hospital wards or the patient' demise.

The blood chemistry parameters considered were: leucocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, hemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, D-dimer, fibrinogen, ferritin, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), sodium and potassium. Details of the selected biomarkers and laboratory instruments used are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Panel of the laboratory parameters evaluated in the study

| Blood chemistry parameters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Panels | Parameters | Instrument |

| Blood count | Hemoglobin | ADVIA 2120 SIEMENS |

| Leukocytes | ||

| Platelet | ||

| Coagulation | D-dimer | CS 1500 SIEMENS |

| Fibrinogen | ||

| Kidney/liver function electrolytes | AST | DIMENSION VISTA 1500 |

| ALT | ||

| Creatinine | ||

| Sodium | ||

| Potassium | ||

| Inflammation and sepsis indices | Ferritin LDH CRP PCT | |

| ADVIA CENTAUR XP SIEMENS | ||

Microbiological data related to blood, bronchoaspirate, urine and intravascular device specimens (central venous catheter, CVC) were collected every day through diagnostic microbiological methods. Each isolate was carefully reviewed by the members of the microbiology team to evaluate its clinical significance. For our analysis, we considered the positivity of the microbiological samples after 7 days of ICU hospitalization to exclude possible bias due to the presence of previous infections.

To determine the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of the clinical isolates, Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF), biotyper (Bruker Daltonics), MicroScan (Beckman Coulter. Inc., Brea, USA), MIC/Combo and NMDR Panel were used. The breakpoint panels use concentrations equivalent to the breakpoint of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) following the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) interpretive criteria. Isolated considered not of clinical relevance, and thus not warranting a specific therapy, were classified as commensal and/or non-significant.

Laboratory data were organized in matrices for statistical analysis. Two different statistical approaches were applied: first, the blood chemistry parameters collected at different time points were processed through multivariate analysis, using the SIMCA-P software (ver. 16.0, Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Umea, Sweden) [19]. Variables were UV scaled, and then the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to explore the sample distributions without classification and identify potential strong outliers through the application of the Hotelling’s T2 test. Subsequently, to study a possible linear relationship between a matrix Y (dependent variable, time) and a matrix X (predictor variables, e.g., blood chemistry parameters), the Partial Least Square (PLS) model was carried out [20]. The variance and the predictive ability (R2X, R2Y, Q2) were evaluated to establish the model’s suitability. In addition, a permutation test (n = 400) was performed to validate the models [21]. The most significant variables were extracted from the PLS model’s loading plot. Variables’ Influence on Projection (VIP) value was also evaluated for the selection of the discriminant variable. This analysis allowed to observe, simultaneously, changing of the variables during the hospitalization of the patients based on the progression of the COVID-19 infection.

Univariate statistical analysis was then performed. In particular, the concentrations of the discriminant parameters were tested through the non-parametric Wilcoxon test. This test is appropriate to investigate differences in paired samples (GraphPad Prism software, version 7.01, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Only differences between variables with p value < 0.05 were considered significant. For these variables, we also evaluated the trend during the three different phases of the pandemic waves specified above.

Results

A total of 178 patients were enrolled in this study. About 74% (131) of these patients died during ICU hospitalization (Deceased patients) while about 26% (47) of them became SARS-CoV-2 negative during the ICU hospitalization and were transferred to other hospital wards (Transferred Patients). Demographic data of the enrolled patients are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic data of the enrolled patients. Data are presented considering firstly the whole cohort of patients and then considering the different phases of the Covid-19 pandemic

| Database Covid-19 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Age mean ± SD (Range) | F/M (%) | Deceased (%) | Transferred (%) | Hospitalization days (Mean ± SD) | |

| All | 178 | 68.1 ± 11.3 (22 − 88) | 31/69 | 74 | 26 | 24 ± 15 |

| Deceased | 132 | 69.7 ± 9.5* (37 − 86) | 31/69 | 17 ± 11 | ||

| Transferred | 46 | 63.2 ± 14.3 (22–88) | 30/70 | 31 ± 20 | ||

| 1 Phase (March–May 2020) | 31 | 69 | ||||

| Deceased | 4 | 81 ± 1.7* (80 − 83) | 67/33 | 11 ± 2 | ||

| Transferred | 9 | 57 ± 15.7 (22 − 78) | 22/78 | 34 ± 24 | ||

| 2 Phase (September–December 2020) | 82 | 18 | ||||

| Deceased | 80 | 69 ± 9.4* (80 − 83) | 25/75 | 17 ± 11 | ||

| Transferred | 18 | 63 ± 14.8 (33 − 88) | 38/62 | 26 ± 18 | ||

| 3 Phase (January–May 2021) | 72 | 28 | ||||

| Deceased | 48 | 70 ± 9.6* (43 − 84) | 39/61 | 18 ± 10 | ||

| Transferred | 19 | 66 ± 11.5 (43 − 82) | 36/64 | 33 ± 21 | ||

* = p < 0.05

For the deceased patients, the mean time from the onset of symptoms to the hospitalization was 5.6 days, and 26% of these patients were admitted directly to the ICU. For the transferred patients, the mean time from the onset of the symptoms to the hospitalization was equal to 6.1 days and 22% of these patients were admitted directly to the ICU. A summary of the onset symptoms, co-morbidities and lifestyle information of the patients is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the onset symptoms and co-morbidities of the patients with COVID-19 classified based on the clinical outcome

| Onset of symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Deceased (%) | Transferred (%) | |

| Dyspnea | 73 | 60 |

| Fever | 72 | 80 |

| Cough | 45 | 53 |

| Asthenia | 31 | 33 |

| Diarrhea | 11 | 16 |

| Myalgia | 9.5 | 16 |

| Hyposmia/Hypogeusia | 5.5 | 3 |

| Headache | 5 | 7 |

| Pharyngodynia | 5 | 7 |

| Sputum | 4 | 0 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 5 | 7 |

| Co-morbidities | ||

| Arterial hypertension* | 57 | 33 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 9.5 | 3 |

| Heart failure | 4 | – |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13 | 10 |

| Aneurysm of the aorta | 3 | 7 |

| Congenital heart disease | – | 3.4 |

| Valvulopathies | 2.4 | – |

| Altered coagulation | 2.4 | 3.4 |

| Brain stroke | 3 | – |

| Dementia | 7 | – |

| Parkinson disease | 1.5 | – |

| Depression | 7 | 7 |

| Dyslipidemia | 21 | 17 |

| Diabetes | 22 | 23 |

| Obesity | 41 | 50 |

| Bronchial asthma | 7.5 | 7 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 14 | 10 |

| Chronic renal failure | 5 | |

| Liver diseases | 2 | – |

| Colon diverticulosis | 3 | – |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases | – | 3 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 11 | – |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4.5 | 14 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | – | 3 |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 | 14 |

| Arthrosis | 3 | – |

| Osteoporosis | 5 | 3 |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 11 | 77 |

| Cancer | 11 | 3 |

| Lifestyle | ||

| BMI | 29.6 | 31 |

| Smokers | 15.9 | 6.9 |

| Habitual alcohol users | 2.3 | 3.4 |

* = p < 0.05

Analysis of the laboratory and microbiological results were based on the different outcomes of the infection to highlight the predictive role of the data concerning the progression and prognosis of the disease.

Analysis of the blood chemistry parameters

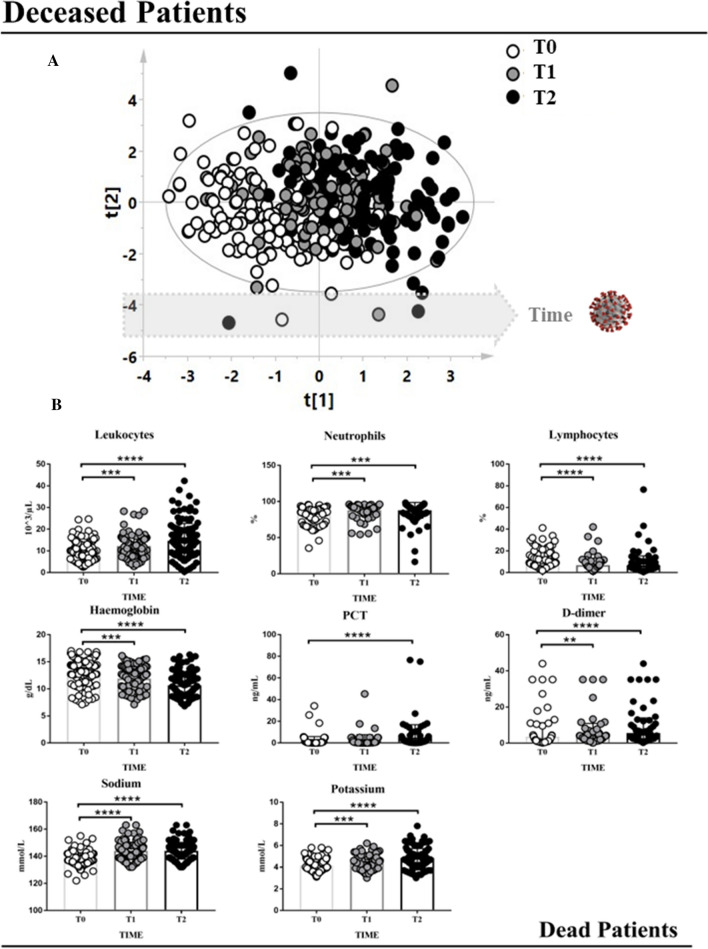

The data matrix of the deceased patients was firstly analyzed with the PCA model to identify outliers that could affect the validity of the analysis. No outliers were identified with this analysis, so all the samples were considered for the subsequent step. Samples were analyzed through a PLS approach, using as Y-variable the three different time points (T0, T1 and T2). The correlation model showed a time-dependent distribution of the samples based on the days of hospitalization (Fig. 1A, statistical parameters were R2X = 0.297, R2Y = 0.464, Q2 = 0.420, p < 0.0001). The model was then validated by using a permutation test (Fig. 1S-A,). This statistical approach allows correlating the number of days of hospitalization with numerical variables, such as the laboratory parameters, with the aim to quickly identify which of them changes its concentration in line with the clinical evolution of the patients.

Fig. 1.

A PLS model built considering the blood chemistry parameters of the deceased patients. This statistical approach allows to correlate the number of the days of hospitalization with numerical variables, such as the laboratory parameters, with the aim to quickly identify which of them change its concentration in line with the clinical evolution of the patients. White circles represent samples at the moment of the hospital admission (T0); gray circles represent samples belonging to the same patients but collected at an intermediate time of hospitalization; black circles represent the samples collected from the same patients before death. B The trend of the discriminant parameters resulted from the multivariate statistical analysis which changed their concentration significantly during the hospitalization of the deceased patients. Wilcoxon test was employed. ** = p value < 0.01, *** = p value < 0.001, **** = p value < 0.0001

Variables (laboratory parameters) that showed a VIP value > 1 were considered discriminant and underwent the Wilcoxon test for paired data. The results are shown in Fig. 1B. Significant changes of some parameters during hospitalization were observed, such as an increase in leukocytes, neutrophils, PCT, D-dimer, sodium and potassium and a decrease in hemoglobin and lymphocyte levels. Moreover, the trend of the laboratory parameters was also evaluated during the three different phases of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (Fig. 2S).

Fig. 2.

A PLS model built considering the blood chemistry parameters of the transferred patients. This statistical approach allows to correlate the number of the days of hospitalization with numerical variables, such as the laboratory parameters, with the aim to quickly identify which of them change its concentration in line with the clinical evolution of the patients. White circles represent samples at the moment of admission to the hospital (T0); gray circles represent samples belonging to the same patients but collected at an intermediate time of hospitalization; blue circles represent the samples collected from the same patients before the transfer from the ICU to other hospital wards. B The trend of the discriminant parameters resulted from the multivariate statistical analysis which significantly changed their concentration during the hospitalization of the transferred patients. Wilcoxon test was employed. ** = p value < 0.01, *** = p value < 0.001, **** = p value < 0.0001

Considering the matrix of the transferred patients, the analysis was conducted following the same workflow applied to the deceased patients. Also in this case, no outliers were identified with this analysis, so all the samples were considered for the subsequent PLS approach, using as Y-variable the three different time points (T0, T1 and T2). The model showed a time-dependent distribution of the samples based on the days of hospitalization (Fig. 2A, statistical parameters were R2X = 0.352, R2Y = 0.49, Q2 = 0.36, p < 0.0001). Also in this case, the distribution of the samples reflected the change in the laboratory parameters used as variables, during the hospitalization. The model was then validated by using a permutation test (Fig. 1S-B).

Variables that showed a VIP value > 1 were considered discriminant and underwent the Wilcoxon test for paired data. The results are shown in Fig. 2B. Changes in some parameters throughout hospitalization were observed with a significant increase in lymphocytes, sodium, platelets, and a significant decrease in neutrophils, hemoglobin, CRP, LDH, fibrinogen, creatinine and AST.

The trend of the laboratory parameters was also evaluated during the three different phases of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (Fig. 3S).

Fig. 3.

PLS-DA model of the T0 samples of the patients which had different outcomes (gray circles are transferred patients while light blue circles represent deceased patients)

To investigate a possible predictive role of the laboratory parameters in terms of prognosis/outcome of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, a supervised model (PLS-DA) of the T0 samples of the transferred and deceased patients was performed. No separation was observed between the two classes of samples and the model was not significant (Fig. 3).

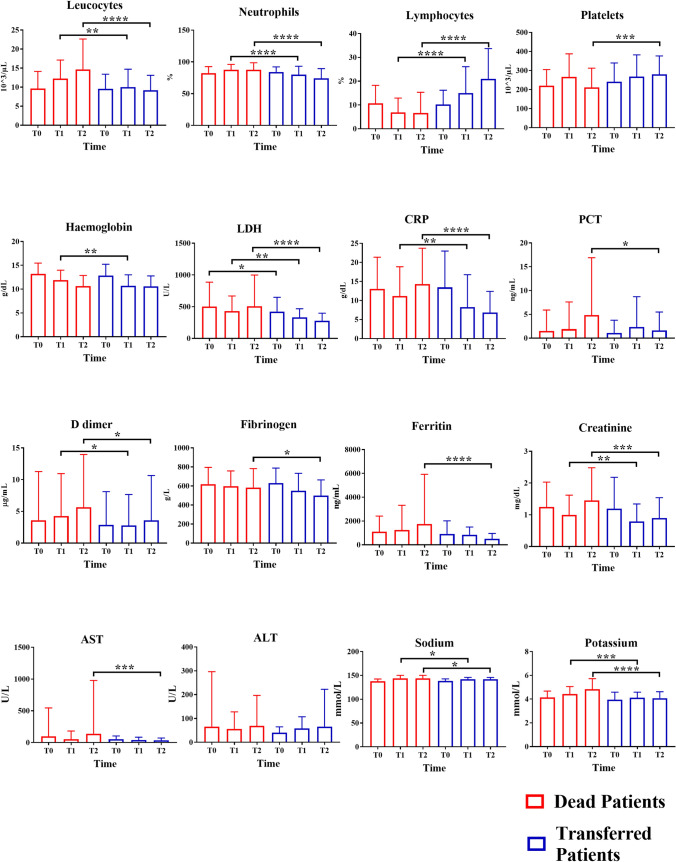

This result was also evidenced when we compared each laboratory parameter of the two classes at T0 time. No significant comparison emerged. However, we also performed the comparisons between deceased and transferred patients considering the laboratory parameters at the three different time points. Interestingly, leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, LDH, CRP, D-dimer, creatinine, sodium and potassium showed significant (p < 0.05) differences in their concentrations starting from the T1 sampling as demonstrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Comparisons of the concentrations of the laboratory parameters considering the three different time points of the deceased and transferred patients (red and blue bars, respectively). Mann–Whitney U test was used (* = p < 0.05, ** = p value < 0.01, *** = p value < 0.001, **** = p value < 0.0001)

Microbiological analysis

Of the enrolled patients, after 7 days of hospitalization, 44% showed the presence of a secondary infection during the hospitalization (and about 80% of these patients had a negative outcome (Fig. 5A). About 38% of the patients showed a microbiological negative result at 7 days, and for about 18% it was not possible to retrieve the information. The microbiological analysis evaluated several specimens: blood, bronchoaspirate, urine and CVC. The summary of the positive samples is reported in Fig. 5B. The analysis of the isolated microbiological species in the different specimens was performed based on the different outcomes of the SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 6). The panel of the antibiotics used is summarized in Fig. 4S. All the patients were exposed to at least 1 dose of an antibiotic.

Fig. 5.

A Percentage of COVID-19 patients with secondary infections after 7 days of hospitalization and mortality relative to the positive patients. B Summary of the positive microbiological specimens in the deceased groups and transferred patients (black and white bars, respectively)

Fig. 6.

A Microbiological results of the different specimens relative to the deceased patients. Blood cultures were positive mainly for CoNS (16%) and S. aureus (12%). Bronchoaspirates were positive mainly for Candida spp. (24%), P. aeruginosa (13%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (8%). Urine cultures were positive for E. faecalis (31%), Candida spp. (18%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (18%); Finally, CVC cultures, were positive for CoNS (37%), while Candida spp. were found in 27% of the cases. B Microbiological results of the different specimens relative to the transferred patients. Blood cultures were positive for CoNS (28%), E. faecalis, E. aerogenes, and K. pneumoniae (12%). Bronchoaspirates were mainly positive for Candida spp. (23%), P. aeruginosa (18%), CoNS and Escherichia Coli (12%); Urine cultures were positive for Candida spp (26%). Finally, in CVC cultures, CoNS were the prevailing bacteria (32%), while P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae were found in 14%

Discussion

By observing the cohort of patients, it emerged that males were more affected by COVID-19 compared to females, regardless of the clinical outcome and the pandemic phase. These data confirm previous studies, in which a higher percentage of males with COVID-19 were reported [22]. Different causes, for example the expression of ACE2 receptor, have been considered as an indicator of gender susceptibility [23].

Based on the demographic data, the mean age of the non-surviving patients was significantly higher than the surviving ones, as expected. If only deceased patients are considered, it is interesting to note that the age of the patients in the first phase was higher, probably because SARS-CoV-2 infection hit the oldest and more susceptible individuals in the population. Other risk factors were also reported, and the percentage of smokers was twice as high in deceased patients compared to the transferred patients, suggesting cigarette smoke as a negative predicting factor of the COVID-19 prognosis [24].

No differences resulted from BMI and alcohol consumption analysis. Several co-morbidities, including hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic renal failure were more frequent in deceased patients [25]. The deceased patients appeared more susceptible to contracting secondary infections and had a reduced ability to compensate for the alterations induced by them [26]. Regarding the onset of symptoms, our data show that only dyspnea, hyposmia/hypogeusia and diarrhea have a higher incidence among deceased patients.

Blood chemistry parameters

Covid-19, and possibly associated secondary infections, caused various laboratory alterations, with a different trend between the two groups analyzed. In deceased patients, there was a statistically significant increase in the indices of inflammation, creatinine, sodium and potassium, and a significant reduction in hemoglobin and lymphocytes, probably due to the organism's failure to counteract infections and consequent organ damage [27]. The same laboratory parameters in surviving patients showed a significant increase in lymphocytes, platelets, sodium, and potassium plus a reduction in the indices of inflammation, hemoglobin and markers of liver damage [28]. These changes are consistent with a probable resolution of the infections and, therefore, improve the clinical outcome.

In this study, the changes in our patients' laboratory test result over time and the differences between the three pandemic waves were also analyzed. Regarding the group of deceased patients, all the considered parameters were stable in the first and third waves. In contrast, in the second wave, leukocytes, procalcitonin, C reactive protein, D-dimer, creatinine, LDH, AST and ALT increased considerably, particularly from T1 to death, while lymphocytes were reduced. These differences over time are probably linked to the fact that in September–December 2020, the patients admitted to the Nuoro ICU were more affected by other bacterial/fungal infections which may have contributed to the poor prognosis of these patients. Regarding the transferred patients, the trend over time of the laboratory results in the three waves was rather stable in the three periods analyzed with minimal variations. In particular, a reduction in the inflammation indices was observed in the first wave, probably because, in our region, this was the phase of the pandemic with fewer COVID-19 cases and fewer deaths, likely related to the geographical position and the severe restrictive measures adopted by the government (national lockdown).

Based on the comparison of the laboratory parameters between the deceased and transferred patients at the admission time (T0), we didn’t find any significant result, and this evidenced the lack of a predictive role of them in terms of prognosis and outcome of the COVID-19 disease. However, several parameters changed significantly their concentrations between the two classes of patients starting from the T1 sampling (leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, LDH, CRP, D-dimer, creatinine, sodium and potassium), suggesting the presence of secondary infections during hospitalization, which may have started to act as reinforcing factors to promote worsening of the disease in vulnerable patients.

Microbiological data

Another crucial aspect of this study was to focus on secondary infections, which comprise the group of all patients with a positive culture (urine, bronchoaspirate, blood culture, and CVC) during hospitalization in the ICU. From our analysis, it emerges that among the 156 patients, approximately 44% presented positive cultures, and of these, 80% died. By analyzing the data from the literature, the percentage of COVID-19 patients with secondary infections is highly variable, ranging between 14 and 100%, depending on the different inclusion criteria used [8, 15, 29].

Differences in the population, specimen source, and pathogens of interest are likely responsible for the wide variations reported [30]. We observed a high percentage of positive samples, and it is probably because, in our study, we considered all the positive cultures occurring after 7 days of hospitalization, including blood and urine cultures, bronchoaspirate and CVC cultures. Another critical aspect to consider is the logistical conditions in which the healthcare personnel had to work, especially during the second wave, as there was a rapid and sudden increase in COVID-19 cases and ICU admissions. The higher incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infection could be explained by the heavy pressure put on the ICU by the COVID-19 outbreak; in fact, during the peak, the ICU capacity of the Nuoro hospital had to be increased by 300% to accommodate all patients requiring critical care. Interestingly, from the microbiological analysis, it emerged that deceased patients showed a higher percentage of positive samples than the transferred patients considering blood cultures and bronchoaspirate. On the other hand, a higher percentage of positive samples in urine cultures and CVC cultures was observed in the group of transferred patients suggesting that it is correlated with the longer period of hospitalization. Indeed, the average ICU stay for the transferred patients was longer than for deceased patients (31 vs 17 days, respectively), explaining the greater occurrence of nosocomial infections in the urine and CVC cultures of the first group of patients.

Our attention focused on the microorganisms likely responsible for the secondary infections in the two groups of patients. Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Candida spp, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and above all CoNS were mainly detected in both groups. These findings are in line with other published studies [15]. During the hospitalization of our patients, Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates developed acquired resistance mechanisms, such as ESBL (Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase) and carbapenem-resistance, determining a difficult challenge for the choice of the antibiotic treatment, especially during the second wave.

Our results are overall consistent with what is already reported in the literature. Microorganisms mainly involved in the COVID-19 secondary infections were Mycoplasma spp., Haemophilus influenzae, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, with a discrete variability in the species most represented and widespread in the various territories and hospitals [12, 31].

Based on our results, it seems clear that secondary infections may have played a critical role in the negative outcome of the patients affected by COVID-19. Secondary infections may have acted as mutually reinforcing factors to promote the progression to severe and fatal disease. Indeed, severe COVID-19 caused multiple damages [32], which may favor rapid bacterial growth; on the other hand, bacterial virulence factors can alter the immune responses, resulting in a rebound of SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease progression, leading to higher mortality in severe and critical patients [33, 34].

Finally, the analysis of our data revealed that the most used antibiotics were Azithromycin (60%), Piperacillin-Tazobactam (40%), and Vancomycin (20%). Such a high percentage of Azithromycin could be attributed to the fact that, in many cases, it was already administered to the patients before hospitalization or in the infectious disease divisions to patients with symptomatic COVID-19. However, despite Azithromycin has been one of the few drugs used in COVID-19 patients during the start of the pandemic, there is currently no evidence to justify the widespread use of this antibiotic [35]. As for Piperacillin-Tazobactam, it has been used in many patients as a broad-spectrum empirical therapy, pending the microbiological and antibiogram results. Finally, Vancomycin was also used in a high percentage of patients to treat infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria resistant to other classes of antibiotics.

Conclusion

The clinical presentation, the presence of co-morbidities, and the laboratory, as well as microbiology data, can be valuable tools for identifying the most severe COVID-19 patients facing a poor prognosis. ICU represented a critical area for the management of patients with severe COVID-19. Between the first and the other two pandemic phase, considered in this study, there has not been an implementation of the resources necessary to properly assist these patients, such as the number of devices and health workers. This may have been an indirect cause for an increased spread of infectious agents within the hospital, particularly in the ICU. Moreover, the higher frequency of isolation of pathogens may have been caused by the fact that the most severe and critically ill COVID-19 cases in ICU underwent invasive procedures, which per se increase the chance of hospital-acquired infections. For these reasons, it is essential to monitor the patients with serial microbiological examinations to undertake optimal targeted treatments to avoid the development of antimicrobial resistance and the spread of MDR microorganisms, which represents a complex global problem that cannot be ignored even in the case of superimposing emergencies as that of the Sars-Cov2 pandemic.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the healthcare operators and the patients included in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization FM, MF, FC, LA, Data curation FM, OM, MM, FC, AP, AA, Formal analysis FM, SP, MA, SO, RA, SS, GM, CM, MGM, SD, Investigation FM, MA, SP, SO, Supervision MCG, LA, Visualization EC, LL, SB, SM, Writing-original draft FM, MF, FC, OM, Writing-review and editing LA, MM, OM, EC, FM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the San Francesco Hospital (428/2022/CE). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Federica Murgia Maura Fiamma Franco Carta and Luigi Atzori have contributed equally.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, et al. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollard CA, Morran MP, Nestor-Kalinoski AL. The COVID-19 pandemic: a global health crisis. Physiol Genomics. 2020;52:549–557. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00089.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parohan M, Yaghoubi S, Seraji A, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Male. 2020;23:1416–1424. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McArdle AJ, Turkova A, Cunnington AJ. When do co-infections matter? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31:209–215. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirzaei R, Goodarzi P, Asadi M, et al. Bacterial co-infections with SARS-CoV-2. IUBMB Life. 2020;72:2097–2111. doi: 10.1002/iub.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jia L, Xie J, Zhao J, et al. Mechanisms of severe mortality-associated bacterial co-infections following influenza virus infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:338. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quah J, Jiang B, Tan PC, et al. Impact of microbial Aetiology on mortality in severe community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:451. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3366-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang G, Hu C, Luo L, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 221 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan. China J Clin Virol. 2020; 127:104364. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendaus MA, Jomha FA. Covid-19 induced superimposed bacterial infection. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39:4185–4191. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1772110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawson TM, Wilson RC, Holmes A. Understanding the role of bacterial and fungal infection in COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie AI, Singanayagam A. Immunosuppression for hyper inflammation in COVID-19: a double-edged sword? Lancet. 2020;395:1111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30691-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blasco ML, Buesa J, Colomina J, et al. Co-detection of respiratory pathogens in patients hospitalized with Coronavirus viral disease-2019 pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1799–1801. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox MJ, Loman N, Bogaert D, et al. Co-infections: potentially lethal and unexplored in COVID-19. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1(1):e11. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa VO, Nicolini EM, da Costa BMA, et al. Evaluation of the Risk of Clinical Deterioration among Inpatients with COVID-19. Adv Virol. 2021;2021:6689669. doi: 10.1155/2021/6689669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murgia F, Fiamma M, Serra S, et al. The impact of secondary infections in COVID-19 critically ill patients. J Infect. 2022;84(6):e116–e117. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson L, Byrne T, Johansson E, et al. Multi- and megavariate data analysis basic principles and applications. Umetrics Academy; 2013. 509.

- 20.Wold S, Sjöström M, Eriksson L. PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2001;58:109–130. doi: 10.1016/S0169-7439(01)00155-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindgren F, Hansen B, Karcher W, et al. Model validation by permutation tests: applications to variable selection. J Chemom. 1996;10:521–532. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-128X(199609)10:5/6<521::AID-CEM448>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P, Lu J-A, Jin Y, et al. Statistical and network analysis of 1212 COVID-19 patients in Henan. China Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Wang Y, et al. Single-Cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:756–759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202001-0179LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kashyap VK, Dhasmana A, Massey A, et al. Smoking and COVID-19: adding fuel to the flame. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:E6581. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ejaz H, Alsrhani A, Zafar A, et al. COVID-19 and comorbidities: deleterious impact on infected patients. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1833–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parohan M, Yaghoubi S, Seraji A, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Male. 2020;23:1416–1424. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang W, Berube J, McNamara M, et al. Lymphocyte subset counts in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Cytometry A. 2020;97:772–776. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.24172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kermali M, Khalsa RK, Pillai K, et al. The role of biomarkers in diagnosis of COVID-19 - a systematic review. Life Sci. 2020;254:117788. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Moreno-García E, et al. Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubin CJ, McConville TH, Dietz D, et al. Characterization of bacterial and fungal infections in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and factors associated with health care-associated infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(6):ofab201. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang ACC, Huang CG, Yang CT, et al. Concomitant infection with COVID-19 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Biomed J. 2020;43(5):458–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghoneim HE, Thomas PG, McCullers JA. Depletion of alveolar macrophages during influenza infection facilitates bacterial superinfections. J Immunol. 2013;191(3):1250–1259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, Zhang Y, Wu J, et al. Risks and features of secondary infections in severe and critical ill COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1958–1964. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1812437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zangrillo A, Beretta L, Scandroglio AM, et al. Characteristics, treatment, outcomes and cause of death of invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19 ARDS in Milan. Italy Crit Care Resusc. 2020;22(3):200–211. doi: 10.1016/S1441-2772(23)00387-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Echeverría-Esnal D, Martin-Ontiyuelo C, Navarrete-Rouco ME, et al. Azithromycin in the treatment of COVID-19: a review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19(2):147–163. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1813024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.