Abstract

Heme proteins, the stuff of life, represent an ingenious biologic strategy that capitalizes on the biochemical versatility of heme, and yet is one that avoids the inherent risks to cellular vitality posed by unfettered and promiscuously reactive heme. Heme proteins, however, may be a double-edged sword because they can damage the kidney in certain settings. Although such injury is often viewed mainly within the context of rhabdomyolysis and the nephrotoxicity of myoglobin, an increasing literature now attests to the fact that involvement of heme proteins in renal injury ranges well beyond the confines of this single disease (and its analog, hemolysis); indeed, through the release of the defining heme motif, destabilization of intracellular heme proteins may be a common pathway for acute kidney injury, in general, and irrespective of the underlying insult. This brief review outlines current understanding regarding processes underlying such heme protein-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Topics covered include, among others, the basis for renal injury after the exposure of the kidney to and its incorporation of myoglobin and hemoglobin; auto-oxidation of myoglobin and hemoglobin; destabilization of heme proteins and the release of heme; heme/iron/oxidant pathways of renal injury; generation of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species by NOX, iNOS, and myeloperoxidase; and the role of circulating cell-free hemoglobin in AKI and CKD. Also covered are the characteristics of the kidney that render this organ uniquely vulnerable to injury after myolysis and hemolysis, and pathobiologic effects emanating from free, labile heme. Mechanisms that defend against the toxicity of heme proteins are discussed, and the review concludes by outlining the therapeutic strategies that have arisen from current understanding of mechanisms of renal injury caused by heme proteins and how such mechanisms may be interrupted.

Keywords: acute kidney injury and ICU nephrology, AKI, auto-oxidation, CKD, heme, hemoglobin, hemolysis, myoglobin, rhabdomyolysis

Introduction

Heme proteins (HPs) are defined by a tetrapyrrole (heme) prosthetic group liganded to a specific protein moiety. Numbering in the hundreds, HPs are characterized by ubiquity, heterogeneity, versatility, and biochemical ingenuity. HPs are present in virtually all cellular and extracellular compartments and are involved in essential cellular processes that maintain homeostasis and health (Table 1). HPs represent an ingenious chemical strategy because they capitalize on the biochemical versatility of heme but circumvent the intrinsic toxicity and insolubility of free heme (1): the heme prosthetic group with its central iron atom can shuttle electrons and engage in assorted oxidation-reduction and catalytic processes; heme possesses the ability to bind and transport various gases (oxygen, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide); and heme may influence gene expression. However, when unliganded, free, and “labile,” heme is toxic (Table 2), and because of its lipophilicity, heme can intercalate and thereby access plasma and cell membranes and cellular compartments (1). This article provides an overview of kidney injury caused by HPs.

Table 1.

Functions of heme proteins

| Function | Relevant Heme Protein |

|---|---|

| Oxygen transport and storage | Hemoglobin, myoglobin, neuroglobin |

| Mitochondrial respiration | Mitochondrial cytochromes |

| Cellular metabolism and detoxification | Cytochrome P450 enzymes |

| Vasodilation | eNOS, cyclooxygenase |

| Endothelial and vascular integrity | eNOS |

| Antioxidant function | Glutathione peroxide, catalase |

| Cellular signaling | cGMP |

| Immune regulation | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| Antimicrobial defense | iNOS, NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase |

Table 2.

Toxic effects of free heme

| • Acute renal vasoconstriction |

| • Stimulates lipid peroxidation and generation of hydrogen peroxide |

| • Functions as a Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern (DAMP) |

| • Impairs glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| • Perturbs certain cytoskeletal proteins |

| • Inhibits cell proliferation |

| • Damages mitochondria |

| • Induces cell death |

| • Activates NF-κB and induces proinflammatory cytokines |

| • Signals through the TLR4 receptor |

| • Activates the inflammasome |

| • Chemoattractant for leukocytes |

| • Promotes leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium |

| • Promotes formation of NETs |

| • Induces platelets to discharge their Weibel–Palade bodies |

| • Induces platelets to activate macrophages |

| • Induces tissue factor expression |

| • Thrombogenic |

NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps.

Overview of HP-Based Processes that Injure the Kidney

Table 3 broadly summarizes how HPs are involved in kidney injury, and this is detailed below.

Table 3.

Major pathways for heme protein-induced renal injury

| Pathway | Relevant Heme Protein | Mechanism of Injury |

|---|---|---|

| Destabilization of HPs | Cytochrome p450, others | Heme/Fe-mediated |

| Cellular egress and delivery to the kidney | Myoglobin, hemoglobin | See Figure 1 |

| Autoxidation of HPs | Myoglobin, hemoglobin | See Figure 2 |

| Aberrant/inordinate HP activation | iNOS, NADPH oxidase | ROS, RNS |

| Mitochondrial release into the cytosol | Cytochrome c | Apoptosis |

| Neutrophil/monocyte degranulation | Myeloperoxidase | ROS, hypohalous acid, NETs |

HPs, heme proteins; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; NET, neutrophil extracellular traps.

Destabilization of HPs

HPs can be destabilized when cells are stressed, leading to the weakening of the union between heme and protein moieties, with the resulting release of heme (1–3). Indeed, renal free heme content is increased not only in AKI induced by myoglobin (Mb) and hemoglobin (Hb) (4,5), but also in AKI caused by “non-HP-related” insults such as ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) (6) and cisplatin (7). Such scission of HPs may especially apply to the relatively unstable cytochrome p450 enzymes (8), proteins abundant in the kidney and needed for diverse metabolic processes. Studies almost 30 years ago called attention to the involvement of catalytic iron, released from destabilized cytochrome p450 enzymes, in the pathogenesis of AKI (8). Destabilized intracellular HPs and attendant increased levels of free heme/Fe may thus provide one of the final common pathways for AKI, irrespective of the original insult. The following support this concept (1): (1) intracellular heme is generally elevated in AKI, and worsening of AKI occurs when heme degradation is compromised by impairment in or deficiency of heme oxygenase-1 or heme oxygenase-2 (4,9,10); (2) free heme is damaging to the kidney and other organs and tissues (Table 2) (1,3,11–14); and (3) heme, when used in large amounts to abort human porphyria, causes fulminant AKI (15).

Cellular Egress and Renal Delivery

The nephrotoxicity of Mb and Hb has been superbly discussed by a prior comprehensive review of the pathogenesis and salient clinical features of HP-AKI (16). The molecular weight (MW) of Mb, released during myolysis, enables rapid filtration into the urinary space. Hb, released during hemolysis, is bound initially to haptoglobin (Hpt) after which the free tetrameric Hb (MW 64 kD) dissociates into dimers (MW 32 kD), the latter also filtered into the urinary space, albeit less easily compared with Mb (1,17). Megalin and cubilin, receptors on the apical surface of the renal proximal tubule, reclaim Mb and Hb present in urine (18,19).

Aberrant/Inordinate Activation of Oxidant-Generating HPs

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and NADPH oxidase (NOX) are inducible HPs that kill microbes, the former by generating peroxynitrite, the latter by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, in disease states, these HPs may be aberrantly or inordinately activated, in the absence of an infectious process, for example, iNOS by numerous cytokines (20), and NOX by angiotensin II (21).

HP Transfer from Mitochondria to the Cytosol

Cytochrome c is an essential member of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. When mitochondria are injured, as invariably occurs in AKI, cytochrome c is released into the cytosol. When present in the cytosol, cytochrome c activates Apaf-1 and caspases 9 and 3, which may culminate in apoptosis (22).

Degranulation of Neutrophils and Monocytes

Activation of these cells releases myeloperoxidase in the extracellular space (23,24). Myeloperoxidase generates abundant ROS and reactive nitrogen species and, in particular, powerful oxidants such as hypohalous acid (from hydrogen peroxide and chloride). Hypohalous acid generates damaging products such as chloramines and glycated proteins (23,24). Myeloperoxidase is required in the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (25). Myeloperoxidase contributes to renal injury in renal vasculitides and glomerulonephritides, and is implicated in IRI and the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy (24).

Rhabdomyolysis/Hemolysis as a Paradigm for HP-Induced AKI

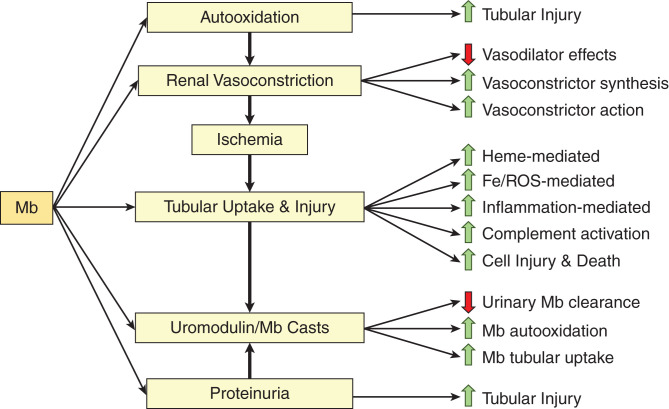

An intriguing aspect of rhabdomyolysis is why the kidney is singled out such that this organ bears the brunt of this disease, a systemic one caused by a toxin released into the circulation (extracellular Mb). Table 4 summarizes the basis for the vulnerability of the kidney to acute injury caused by Mb or Hb. Figure 1 outlines the intrarenal pathways involved in AKI caused by Mb (and likely applies to Hb-AKI) and is detailed as follows.

Table 4.

Vulnerability of the kidney to AKI after myolysis or hemolysis

| • Renal O2 consumption, second highest among tissues, relies on high renal blood flow rates. The kidney is particularly sensitive to the vasoconstricting actions of HPs. |

| • The proximal tubule expresses megalin/cubilin, which reclaim HPs filtered into urine. |

| • The proximal tubule has the second highest mitochondrial volume density of all organs/tissues; mitochondria are vulnerable to the damaging effects of heme. |

| • The kidney is enriched in cytochrome p450 enzymes, which are prone to destabilization under stress; heme and iron may be thereby released. |

| • The kidney uniquely produces uromodulin, a glycoprotein with a proclivity for forming casts with Mb and Hb. |

| • H2O2, present in urine (in µM amounts), promotes auto-oxidation of Mb and Hb. |

| • Urinary acidification promotes uromodulin-HP cast formation. |

| • Urinary acidification promotes lipid peroxidation by HP-Fe4+. |

HPs, heme proteins; Mb, myoglobin; Hb, hemoglobin.

Figure 1.

Outline of intrarenal pathways involved in AKI. Please see relevant text for details. Please see Figure 2 for auto-oxidation of HPs. Processes listed on the right of the figure are either causes or consequences of the relevant pathways listed to their left and are linked by an arrow. HP, heme protein; Mb, myoglobin; Fe, iron; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Renal Vasoconstriction

Vasodilation of the intact kidney is largely dependent on production of nitric oxide (and, to a much less extent, carbon monoxide). Mb and Hb induce renal vasoconstriction through three main processes. First, the heme prosthetic group of these HPs avidly binds nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, thereby siphoning off these vasodilators from the renal vasculature with resulting renal vasoconstriction (17,26). These HPs, when in plasma, also undergo auto-oxidation with the generation of superoxide anion (see below), which further depletes vascular nitric oxide because superoxide anion avidly interacts with nitric oxide to generate peroxynitrite. Second, Mb and Hb also stimulate the production of potent vasoconstrictors in the kidney, including isoprostanes (27,28), endothelin-1 (29), and thromboxanes (30), in large part via the oxidative stress imposed by these HPs; notably, the kidney may be particularly sensitive to vasoconstrictors such as endothelin-1 and isoprostanes (28,31). Glycerol-induced AKI (G-AKI), a commonly used model of HP-AKI, reflects the pathogenetic involvement of isoprostanes (27,28) and endothelin-1 (32,33). Third, Mb potentiates the vasoconstrictive effects of angiotensin II produced by the kidney (34). Renal vasoconstriction not only impairs renal delivery of oxygen and nutrients but also imposes renal ischemia. Ischemia exerts adverse metabolic effects, including the reduction in kidney content of ATP, NAD+, and glutathione (GSH, a major component of the antioxidant GSH/glutathione peroxidase system) (35), all of which would heighten the sensitivity of the renal proximal tubule to injury when subsequently exposed to Mb or Hb.

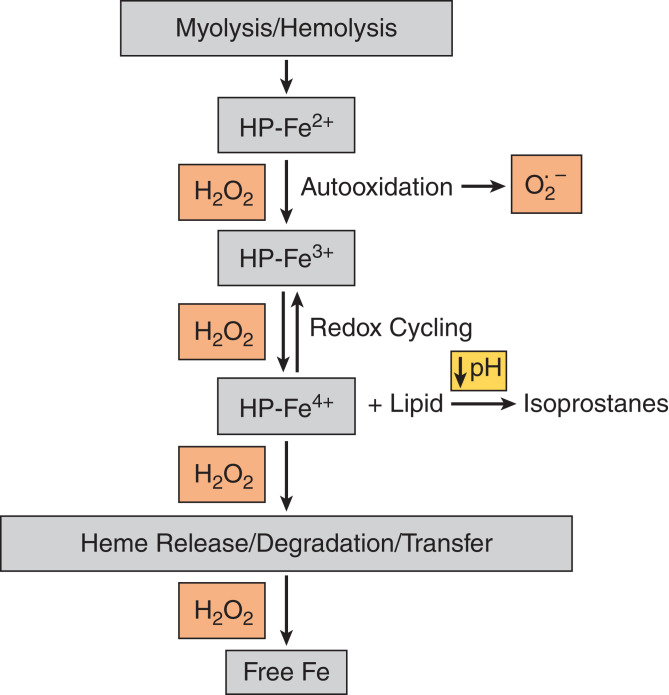

Auto-Oxidation of Mb/Hb

Figure 2 broadly summarizes these biochemical processes, as previously discussed (2,36,37). When Mb and Hb are released into the circulation, they undergo auto-oxidation because they are no longer surrounded by the reducing and antioxidant intracellular milieu of myocytes and red blood cells (RBCs); such an intracellular milieu maintains the heme iron of these HPs in the ferrous (Fe2+) state needed for oxygen transport and storage. Extracellularly, however, the HP-Fe2+ species is oxidized (by oxygen and/or hydrogen peroxide) first to HP-Fe3+, accompanied by the generation of superoxide anion (and subsequently hydrogen peroxide). HP-Fe3+ is further oxidized by hydrogen peroxide to HP-Fe4+ and other radical species, which induce lipid peroxidation and the formation of isoprostanes; redox cycling occurs between HP-Fe4+ and HP-Fe3+. Two unique attributes of the kidney promote Mb/Hb auto-oxidization and its harmful effects. First, even in the presence of normal kidney function, urine contains hydrogen peroxide in micromolar amounts (38). As shown in Figure 2, hydrogen peroxide promotes the auto-oxidation of HPs; redox cycling between their ferric and ferryl species; and the degradation, release, or transfer of heme in HP-Fe4+. Second, urinary acidification heightens lipid peroxidation caused by HP-Fe4+ and the accompanying generation of the potent renal vasoconstrictor, isoprostanes, an effect that underlies, in part, the protective effects of alkali in HP-AKI (27). Through such Mb/Hb auto-oxidation, occurring in plasma and urine, ROS/heme/Fe-mediated damage may occur in the kidney.

Figure 2.

Auto-oxidation of HPs (myoglobin/hemoglobin). Please see relevant text for details.

Impaired Glomerular Filtration Barrier and Proteinuria

Approximately 50% or more of patients with rhabdomyolysis may be proteinuric, with substantial subsets being frankly nephrotic (39). In traversing the glomerular filtration barrier, Mb and Hb may be incorporated by the podocyte, which, like the proximal tubule, has an active endocytic process (40). Such Mb/Hb incorporation may damage the podocyte by processes akin to those in the proximal tubule, thereby impairing glomerular permselectivity with attendant proteinuria (40). For example, Hb is endocytosed via megalin/cubilin receptors by podocytes in vitro and in vivo, and in the course of the metabolism of Hb, cellular oxidative stress occurs with attendant podocyte injury and apoptosis of podocytes (40). Glomerular leakage of protein may contribute to tubular injury in HP-AKI because proteinuria is a risk factor for tubulointerstitial injury for virtually all kidney diseases (41).

Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cell Injury

The proximal tubule bears the brunt of functional impairment and structural damage in G-AKI (42). Present on the apical surface of the proximal tubule, megalin/cubilin receptors are a Trojan horse that incorporate Mb and Hb intracellularly. Studies based on an innovative, inducible, proximal tubule-specific genetic deficiency of megalin in mice demonstrate that such mice are markedly protected against G-AKI, and that the administration of cilastin, an inhibitor of megalin, similarly confers protection in G-AKI (18). These HPs are then split intracellularly into their heme and protein moieties. The rise in renal intracellular heme levels reflects not only heme originating from Mb and Hb, but also heme derived from destabilized cytochrome p450 HPs (1). Heme also causes tubular injury through the release of iron when the heme ring is degraded (43); increased intracellular levels of free iron is reactive, catalyzing the Fenton reaction and the generation of ROS (44,45). Abundant evidence indicates the involvement of iron and ROS in HP-AKI. In G-AKI, there is increased generation of hydrogen peroxide (46), increased lipid peroxidation (47), depletion of GSH (48), and increased amounts of catalytic iron (49), whereas scavengers of hydrogen peroxide (50), inhibitors of lipid peroxidation (28,51), GSH repletion (48), scavengers of the hydroxyl radical (49), iron chelation (49), the potent antioxidant thioredoxin (52), and antioxidant anti-inflammatory nutrients (53) are all protective in G-AKI.

Heme-Dependent Mitochondrial Injury

The fundamental role of acute mitochondrial injury in driving IRI is now supported by abundant evidence (54–56). Some 25 years ago, we posited that intracellular free heme targets mitochondria because heme would permeate their lipid-rich outer membrane, whereas heme’s toxicity would be amplified by the low-level mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide (5). In G-AKI, studied at 24 hours, mitochondrial respiration was profoundly impaired, whereas mitochondria exhibited swelling and loss of cristae (5). Even at 3 hours, mitochondria were functionally and structurally injured; mitophagy was also observed (5). Mitochondrial heme content increased more than six-fold, and exposing normal mitochondria to such levels of heme led to cessation of respiration within 1 hour (5). Our recent studies in G-AKI demonstrate that mitochondrial biogenesis is impaired whereas mitochondrial fission is enhanced. Consistent with these findings is the observation that heme-exposed proximal tubule epithelial cells demonstrate suppression of PGC-1α (a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis) and marked induction of DRP1 (a key participant in mitochondrial fission) (57). We also demonstrated that mitochondrial injury and mitophagy occurred in the kidney in hemolysis-induced human AKI (58). Regarding these preclinical and clinical observations, we speculate that mitophagy confers a nephroprotective effect because mitophagy cordons off injured mitochondria and thereby sequesters these injured organelles away from potentially viable tissue.

Inflammation

Proinflammatory responses are robust in G-AKI (59), and clear evidence supports the role of specific proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α in G-AKI (60). Proinflammatory cytokines are commonly induced by the transcription factor NF-κB, and studies in vitro demonstrate that NF-κB is activated by heme, reactive iron, and ROS (61). However, although there is evidence that protective strategies in G-AKI are attended by decreased activation of NF-κB (62,63), there do not appear to be studies examining the effect of directly suppressing activation of NF-κB per se on G-AKI. NF-κB activation occurs, in part, after signaling through the TLR4 receptor (3), and studies in vitro demonstrate that the proinflammatory effects of heme occur through the TLR4 receptor (3,64). However, studies in vivo using TLR4−/− mice or an inhibitor of the TLR4 receptor have failed to demonstrate a protective effect of these strategies in G-AKI (64). Two investigative lines regarding inflammation and AKI induced by Mb or Hb merit emphasis. First, infiltrating macrophages contribute to the severity of G-AKI (65) because these macrophages are polarized to a proinflammatory (and injurious) M1 phenotype. Additionally, platelets, activated by heme, engage macrophage receptors to generate ROS and form macrophage extracellular traps, which, in turn, lead to TLR-dependent pathways of AKI (66). The other investigative line explored in AKI induced by Mb or Hb attests to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the attendant production of proinflammatory cytokines and the instigation of pathways of cell death (67–71). Finally, it should be noted that not all macrophages or cytokines are injurious in G-AKI (65). For example, erythropoietin is protective in G-AKI by inducing polarization of macrophages to the potentially protective M2 phenotype (72), whereas the cytokine G-CSF protects against G-AKI (73).

Complement-Mediated Renal Injury

Heme activates the alternative complement pathway (26). Recent studies demonstrate that complement activation occurs in both humans with rhabdomyolysis and rodents with G-AKI (74,75). Complement depletion by cobra venom factor protects against G-AKI, as do genetic deficiency of C3 and strategies that bind heme (74,75). Activation of complement occurs via two pathways: the lectin pathway and the alternative complement pathway (74).

Tubular Cast Formation

The thick ascending limb uniquely generates abundant amounts of uromodulin (Tamm–Horsfall protein), a glycoprotein with a strong proclivity for forming casts with Mb or Hb, especially under acidotic conditions and when urinary flow rate is low (76). Cast formation promotes renal injury for three reasons (Figure 1). First, this impedes the urinary clearance of Mb and Hb. Second, this promotes auto-oxidation of HPs by urinary hydrogen peroxide. Third, nephron obstruction prolongs the exposure of proximal tubules to Mb and Hb, thereby promoting cellular uptake of Mb and Hb and tubular damage. Proximal tubule cell injury and the sloughing of cells and their fragments into the urinary space foster cast formation; proteins leaked into the urinary space because of impaired glomerular permselectivity also promote cast formation. However, such involvement of uromodulin in AKI induced by Mb and Hb must be viewed within the context of recent seminal insights regarding uromodulin (77,78). Uromodulin serves assorted homeostatic functions in the healthy kidney and protects against IRI by suppressing the IL-23/IL-17 axis and neutrophil recruitment, among other actions (77,78). Uromodulin’s interaction with Mb or Hb and its resulting adverse effects thus mask and overwhelm the homeostatic and otherwise nephroprotectant effects of this unique protein.

Circulating Cell-Free Hb and AKI

In hemolytic states, circulating cell-free Hb (CFH) is detected and is implicated in the pathogenesis of AKI. Salient examples include cardiopulmonary bypass surgery (79), sickle cell anemia (80), paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (81), transfusion reactions (82), infectious processes (82), preeclampsia and the HELLP syndrome (83), thrombotic microangiopathy (82), and sepsis (82). Sepsis is a major cause of AKI (84), and the appearance of CFH in sepsis may reflect either the underlying cause for sepsis or adverse effects of sepsis on RBCs (82). Sepsis leads to impaired deformability of RBCs and RBC damage in the turbulence-prone areas of the macrocirculation and in the constraining luminal space of the microcirculation (82,85). Additionally, the inflammatory and prothrombotic milieu of sepsis can provoke eryptosis (RBC cell death) and/or disseminated intravascular coagulation, either of which may lead to CFH (82). CFH, in turn, exacerbates the severity of AKI caused by sepsis (86). A proximate step in sepsis-associated damage to the kidney and other organs is endothelial injury. Such injury is characterized by degradation of the glycocalyx lining the endothelium, increased endothelial leakiness with transendothelial egress of fluids and proteins from the circulation, and an endothelium that promotes inflammation, leukocyte adhesion, and thrombosis (87). Such endothelial changes may all result from the damaging effects of auto-oxidation of CFH and the release of heme (88). Heme is not only proinflammatory but also thrombogenic (89).

HPs/Heme and CKD

Recurrent Exposure to Rhabdomyolysis/Hemolysis

We previously described a triphasic response when the kidney is exposed intermittently to HPs: first, AKI; second, acquired resistance to AKI; and third, CKD (90). These studies articulated the concept that AKI can eventuate in CKD (90). Such occurrence of CKD represents the culmination of recurrent episodes of ischemia and oxidative stress imposed by HPs and is likely mediated through upregulation of oxidant-inducible cytokines such as MCP-1 and TGF-β1 (81,90).

Hematuric Glomerular Disease

Thirty years ago, we postulated that hematuria (a source of Hb) can contribute to CKD (41), a thesis based on studies demonstrating that hematuric glomerulonephritis leads to endocytosis by and degradation of RBCs within the proximal tubule (91), and that microinjection of RBCs into the tubular lumen of proximal tubules leads, progressively, to endocytosis of RBCs and their intracellular destruction, proximal tubule injury, peritubular interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, and CKD (92). In support of this thesis of hematuria-instigated, Hb-driven CKD is the demonstration in large national databases that persistent asymptomatic isolated microscopic hematuria is a risk factor for progressive CKD and ESKD (93).

Tubulointerstitial Disease

Activated leukocytes infiltrating the tubulointerstitium can upregulate iNOS and NOX, and/or release myeloperoxidase that injures the kidney as previously discussed. Renal tubules, when stimulated by cytokines or angiotensin II, may upregulate iNOS and NOX, and thereby serve as additional sources for ROS and reactive nitrogen species.

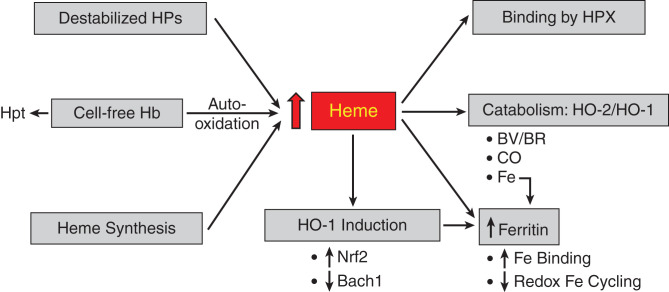

Defense against HPs

Such defenses include superoxide/hydrogen peroxide-scavenging systems and those that are specifically geared to Hb, heme, and iron (Figure 3). Superoxide dismutase converts superoxide anion to hydrogen peroxide, whereas the latter is degraded by the glutathione/glutathione peroxidase system and by catalase. Nonenzymatic degradation of hydrogen peroxide also occurs by α-keto acids, and, pyruvate, an α-keto acid, protects against G-AKI (50). Ascorbate and uric acid provide antioxidant defense in plasma, whereas α-tocopherol and ubiquinone reduce membrane lipid peroxidation.

Figure 3.

Major pathways that lead to increased amounts of free heme and those that bind or catabolize heme. Please see relevant text for details. Heme stimulates ferritin synthesis via iron released from the heme prosthetic group by HO activity. Hb, hemoglobin; Hpt, haptoglobin; HPX, hemopexin; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; HO-2, heme oxygenase-2; BV/BR, biliverdin/bilirubin; CO, carbon monoxide.

The toxicity of CFH is interrupted by the binding of Hb to Hpt, the complex then incorporated by phagocytes via the CD163 receptor (2,17). Such binding negates Hb auto-oxidation and Hb’s permeation into the urinary space. The significance of Hb-Hpt binding is reflected by the increased sensitivity of Hpt−/− mice to AKI after hemolysis (94) and that the administration of Hpt to individuals undergoing cardiac surgery (a CFH-associated condition) reduces the risk for AKI (95). Free heme is bound to proteins and/or degraded. Hemopexin (HPX) is, overwhelmingly, the dominant heme-binding protein; albumin binds heme but only quite weakly (2,17). Genetic deficiency of HPX promotes AKI in sickle cell disease, the latter attended by CFH; administration of HPX reduces such injury in sickle cell disease (96). Alpha1-microglobulin also binds heme and scavenges ROS and protects against heme-mediated injury in vitro and in a model of preeclampsia (83,97). Hepcidin, a protein involved in iron homeostasis and one that may suppress inflammation, is protective in IRI (98), and, interestingly, hepcidin protects cells of the distal nephron against cell death caused by Hb/heme (99).

Studies in G-AKI were the first to demonstrate the cytoprotectant actions of HO-1 in any tissue (9) and were predicated on the long and singular history in nephrology of seeking to understand the basis of tissue resistance to injury (100). HO catabolizes heme to biliverdin during which iron is released from the heme ring and carbon monoxide evolves; biliverdin is then converted to bilirubin via biliverdin reductase. HO-1 and HO-2 are the inducible and constitutive isoforms, respectively. HO-2 provides an already existing mechanism for catabolizing heme, whereas HO-1 induction, commonly facile and fulminant, markedly increases the cellular capacity for degrading heme. Induction of HO-1 was subsequently shown to protect against other forms of renal injury (101–103) and contribute to acquired resistance to renal injury (104). Induction of HO-1 is coupled to increased synthesis of ferritin, the dominant iron-binding protein (9,105). The virtue of this system is that it ensures not only the removal of heme but also the safe sequestration by ferritin of iron released from the heme ring. Ferritin not only binds iron with very high capacity (one molecule of ferritin binds 4500 atoms of iron), but the ferritin h-chain prevents the redox cycling of iron and thus the propagation of oxidative stress (105,106). If, however, the increase in free heme overwhelms the existing or induced heme oxygenase-ferritin system, heme- and iron-dependent pathways of injury will ensue. Heme can be degraded nonenzymatically (e.g., by ROS) that circumvents the seamlessly protective coupling of induction of ferritin to that of HO-1, and iron-mediated oxidant damage may occur. The protective effects of the HO system arise not only from degrading heme but also from the intrinsic protective effects of ferritin, bile pigments, and carbon monoxide. Biliverdin and bilirubin are anti-inflammatory and antioxidant, and, in relatively low amounts, are cytoprotective. Carbon monoxide, in low concentrations, is vasorelaxant, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic. In G-AKI, persuasive evidence attests to the protective effects of ferritin (106) and carbon monoxide (107). In an in vitro model of HP-induced renal injury, bilirubin, in micromolar amounts, exerts dose-dependent cytoprotection (108). The cytoprotective effects of the HO-1/ferritin system ramify widely; for example, they enable the kidney to degrade safely free labile heme appearing during hemolytic episodes caused by malaria (109). Upstream of HO-1 is the transcription factor Nrf2, which is readily activated by heme (110). Activation of Nrf2 is protective in HP-AKI (111–115) via the induction of HO-1 and other antioxidant enzymes. An innovative approach to activating Nrf2 in G-AKI involves the inhibition of HO activity and the administration of iron, in essence exerting renal stress, which then elicits robust Nrf2 activation and induction of assorted cytoprotective genes, including HO-1 gene/protein (115,116).

A repressor of HO-1 expression is the protein bach1 (117). Increased amounts of heme release HO-1 expression from repression by bach1, with the attendant induction of HO-1 mRNA. The applicability of this construct for HO-1 induction has been shown in G-AKI.

G-AKI is attenuated not only by constitutive and inducible defense mechanisms but also by regenerative and reparative responses; such responses and attendant AKI recovery are fostered by mesenchymal stromal cells and derived extracellular vesicles (118).

Conclusions

This brief review outlines current understanding of the pathogenetic processes underlying such HP-induced kidney damage and from which diverse therapeutic strategies have been uncovered (Table 5). Translating these preclinical strategies into therapeutic realities is, indubitably, the challenge that lies ahead, and will likely involve a multipronged approach.

Table 5.

Therapeutic strategies in preclinical studies that reduce AKI induced by HPs

| • Vasodilators (27,28,32,33,51) |

| • Bicarbonate (27,76) |

| • Antioxidants (28,48,49,50,52) |

| • Curcumin (53,114) |

| • Haptoglobin (94,95) |

| • Hemopexin (74) |

| • α1-microglobulin (83,97) |

| • Hepcidin (99) |

| • Ferritin (106) |

| • Iron-binding agents (49) |

| • Inhibitors of megalin (18) |

| • Inhibitors of complement (74,75) |

| • Anti-inflammatory compounds (60,62,63,70,71,73) |

| • Acetaminophen (51) |

| • Erythropoietin (72) |

| • Inducers of HO-1/HO products (9,106–108) |

| • Activators of Nrf2 (111–115) |

| • Preconditioning (115,116) |

| • Mesenchymal stromal cells and extracellular vesicles (118) |

HPs, heme proteins.

Disclosures

C.M. Adams reports ownership interest in Emmyon, Inc.; research funding from Emmyon, Inc.; patents or royalties from Emmyon, Inc.; and an advisory or leadership role for Emmyon, Inc. K.A. Nath reports an advisory or leadership role for the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology and Mayo Clinic Proceedings. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

K.A. Nath was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK11916).

Author Contributions

A.J. Croatt, K.A. Nath, and R.D. Singh wrote the original draft of the manuscript; K.A. Nath was responsible for the formal analysis, funding acquisition, and supervision; K.A. Nath and R.D. Singh were responsible for the conceptualization; R.D. Singh and K.A. Nath were responsible for the methodology and visualization; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Tracz MJ, Alam J, Nath KA: Physiology and pathophysiology of heme: Implications for kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 414–420, 2007. 10.1681/ASN.2006080894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaer DJ, Buehler PW, Alayash AI, Belcher JD, Vercellotti GM: Hemolysis and free hemoglobin revisited: Exploring hemoglobin and hemin scavengers as a novel class of therapeutic proteins. Blood 121: 1276–1284, 2013. 10.1182/blood-2012-11-451229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belcher JD, Nath KA, Vercellotti GM: Vasculotoxic and proinflammatory effects of plasma heme: Cell signaling and cytoprotective responses. ISRN Oxidative Med 2013: 831596, 2013. 10.1155/2013/831596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nath KA, Haggard JJ, Croatt AJ, Grande JP, Poss KD, Alam J: The indispensability of heme oxygenase-1 in protecting against acute heme protein-induced toxicity in vivo. Am J Pathol 156: 1527–1535, 2000. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65024-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nath KA, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, Likely S, Hebbel RP, Enright H: Intracellular targets in heme protein-induced renal injury. Kidney Int 53: 100–111, 1998. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maines MD, Mayer RD, Ewing JF, McCoubrey WK Jr: Induction of kidney heme oxygenase-1 (HSP32) mRNA and protein by ischemia/reperfusion: Possible role of heme as both promotor of tissue damage and regulator of HSP32. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 264: 457–462, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal A, Balla J, Alam J, Croatt AJ, Nath KA: Induction of heme oxygenase in toxic renal injury: A protective role in cisplatin nephrotoxicity in the rat. Kidney Int 48: 1298–1307, 1995. 10.1038/ki.1995.414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paller MS, Jacob HS: Cytochrome P-450 mediates tissue-damaging hydroxyl radical formation during reoxygenation of the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 7002–7006, 1994. 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nath KA, Balla G, Vercellotti GM, Balla J, Jacob HS, Levitt MD, Rosenberg ME: Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid, protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest 90: 267–270, 1992. 10.1172/JCI115847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nath KA, Grande JP, Farrugia G, Croatt AJ, Belcher JD, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM, Katusic ZS: Age sensitizes the kidney to heme protein-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F317–F325, 2013. 10.1152/ajprenal.00606.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balla J, Zarjou A: Heme burden and ensuing mechanisms that protect the kidney: Insights from bench and bedside. Int J Mol Sci 22: 8174, 2021. 10.3390/ijms22158174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gbotosho OT, Kapetanaki MG, Kato GJ: The worst things in life are free: The role of free heme in sickle cell disease. Front Immunol 11: 561917, 2021. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.561917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Michaca L, Farrugia G, Croatt AJ, Alam J, Nath KA: Heme: A determinant of life and death in renal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F370–F377, 2004. 10.1152/ajprenal.00300.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Immenschuh S, Vijayan V, Janciauskiene S, Gueler F: Heme as a target for therapeutic interventions. Front Pharmacol 8: 146, 2017. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhar GJ, Bossenmaier I, Cardinal R, Petryka ZJ, Watson CJ: Transitory renal failure following rapid administration of a relatively large amount of hematin in a patient with acute intermittent porphyria in clinical remission. Acta Med Scand 203: 437–443, 1978. 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1978.tb14903.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zager RA: Rhabdomyolysis and myohemoglobinuric acute renal failure. Kidney Int 49: 314–326, 1996. 10.1038/ki.1996.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rother RP, Bell L, Hillmen P, Gladwin MT: The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin: A novel mechanism of human disease. JAMA 293: 1653–1662, 2005. 10.1001/jama.293.13.1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsushita K, Mori K, Saritas T, Eiwaz MB, Funahashi Y, Nickerson MN, Hebert JF, Munhall AC, McCormick JA, Yanagita M, Hutchens MP: Cilastatin ameliorates rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 2579–2594, 2021. 10.1681/ASN.2020030263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gburek J, Verroust PJ, Willnow TE, Fyfe JC, Nowacki W, Jacobsen C, Moestrup SK, Christensen EI: Megalin and cubilin are endocytic receptors involved in renal clearance of hemoglobin. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 423–430, 2002. 10.1681/ASN.V132423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aktan F: iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production and its regulation. Life Sci 75: 639–653, 2004. 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takaishi K, Kinoshita H, Kawashima S, Kawahito S: Human vascular smooth muscle function and oxidative stress induced by NADPH oxidase with the clinical implications. Cells 10: 1947, 2021. 10.3390/cells10081947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE, Didelot C, Kroemer G: Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 13: 1423–1433, 2006. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins CL, Davies MJ: Role of myeloperoxidase and oxidant formation in the extracellular environment in inflammation-induced tissue damage. Free Radic Biol Med 172: 633–651, 2021. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malle E, Buch T, Grone HJ: Myeloperoxidase in kidney disease. Kidney Int 64: 1956–1967, 2003. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Sullivan KM, Holdsworth SR: Neutrophil extracellular traps: A potential therapeutic target in MPO-ANCA associated vasculitis? Front Immunol 12: 635188, 2021. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.635188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Avondt K, Nur E, Zeerleder S: Mechanisms of haemolysis-induced kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol 15: 671–692, 2019. 10.1038/s41581-019-0181-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore KP, Holt SG, Patel RP, Svistunenko DA, Zackert W, Goodier D, Reeder BJ, Clozel M, Anand R, Cooper CE, Morrow JD, Wilson MT, Darley-Usmar V, Roberts LJ 2nd: A causative role for redox cycling of myoglobin and its inhibition by alkalinization in the pathogenesis and treatment of rhabdomyolysis-induced renal failure. J Biol Chem 273: 31731–31737, 1998. 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nath KA, Balla J, Croatt AJ, Vercellotti GM: Heme protein-mediated renal injury: A protective role for 21-aminosteroids in vitro and in vivo. Kidney Int 47: 592–602, 1995. 10.1038/ki.1995.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng G, Yu WH, Yan C, Liu Y, Li WJ, Zhang DD, Liu N: Nuclear factor-κB is involved in oxyhemoglobin-induced endothelin-1 expression in cerebrovascular muscle cells of the rabbit basilar artery. Neuroreport 27: 875–882, 2016. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieberthal W, LaRaia J, Valeri CR: Role of thromboxane in mediating the intrarenal vasoconstriction induced by unmodified stroma free hemoglobin in the isolated perfused rat kidney. Biomater Artif Cells Immobilization Biotechnol 20: 663–667, 1992. 10.3109/10731199209119698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhaun N, Webb DJ, Kluth DC: Endothelin-1 and the kidney—Beyond BP. Br J Pharmacol 167: 720–731, 2012. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02070.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karam H, Bruneval P, Clozel JP, Löffler BM, Bariéty J, Clozel M: Role of endothelin in acute renal failure due to rhabdomyolysis in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274: 481–486, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu T, Kuroda T, Ikeda M, Hata S, Fujimoto M: Potential contribution of endothelin to renal abnormalities in glycerol-induced acute renal failure in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286: 977–983, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu ZZ, Mathia S, Pahlitzsch T, Wennysia IC, Persson PB, Lai EY, Högner A, Xu MZ, Schubert R, Rosenberger C, Patzak A: Myoglobin facilitates angiotensin II-induced constriction of renal afferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F908–F916, 2017. 10.1152/ajprenal.00394.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nath KA, Norby SM: Reactive oxygen species and acute renal failure. Am J Med 109: 665–678, 2000. 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00612-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rifkind JM, Mohanty JG, Nagababu E: The pathophysiology of extracellular hemoglobin associated with enhanced oxidative reactions. Front Physiol 5: 500, 2015. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson MT, Reeder BJ: The peroxidatic activities of myoglobin and hemoglobin, their pathological consequences and possible medical interventions. Mol Aspects Med 84: 101045, 2022. 10.1016/j.mam.2021.101045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nath KA, Ngo EO, Hebbel RP, Croatt AJ, Zhou B, Nutter LM: alpha-Ketoacids scavenge H2O2 in vitro and in vivo and reduce menadione-induced DNA injury and cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol 268: C227–C236, 1995. 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.1.C227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabow PA, Kaehny WD, Kelleher SP: The spectrum of rhabdomyolysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 61: 141–152, 1982. 10.1097/00005792-198205000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubio-Navarro A, Sanchez-Niño MD, Guerrero-Hue M, García-Caballero C, Gutiérrez E, Yuste C, Sevillano Á, Praga M, Egea J, Román E, Cannata P, Ortega R, Cortegano I, de Andrés B, Gaspar ML, Cadenas S, Ortiz A, Egido J, Moreno JA: Podocytes are new cellular targets of haemoglobin-mediated renal damage. J Pathol 244: 296–310, 2018. 10.1002/path.5011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nath KA: Tubulointerstitial changes as a major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am J Kidney Dis 20: 1–17, 1992. 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)80312-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westenfelder C, Arevalo GJ, Crawford PW, Zerwer P, Baranowski RL, Birch FM, Earnest WR, Hamburger RK, Coleman RD, Kurtzman NA: Renal tubular function in glycerol-induced acute renal failure. Kidney Int 18: 432–444, 1980. 10.1038/ki.1980.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baliga R, Zhang Z, Baliga M, Shah SV: Evidence for cytochrome P-450 as a source of catalytic iron in myoglobinuric acute renal failure. Kidney Int 49: 362–369, 1996. 10.1038/ki.1996.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker VJ, Agarwal A: Targeting iron homeostasis in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 36: 62–70, 2016. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scindia Y, Leeds J, Swaminathan S: Iron homeostasis in healthy kidney and its role in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 39: 76–84, 2019. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guidet B, Shah SV: Enhanced in vivo H2O2 generation by rat kidney in glycerol-induced renal failure. Am J Physiol 257: F440–F445, 1989. 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.3.F440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paller MS: Hemoglobin- and myoglobin-induced acute renal failure in rats: Role of iron in nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol 255: F539–F544, 1988. 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.3.F539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abul-Ezz SR, Walker PD, Shah SV: Role of glutathione in an animal model of myoglobinuric acute renal failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88: 9833–9837, 1991. 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah SV, Walker PD: Evidence suggesting a role for hydroxyl radical in glycerol-induced acute renal failure. Am J Physiol 255: F438–F443, 1988. 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.3.F438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salahudeen AK, Clark EC, Nath KA: Hydrogen peroxide-induced renal injury. A protective role for pyruvate in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest 88: 1886–1893, 1991. 10.1172/JCI115511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boutaud O, Moore KP, Reeder BJ, Harry D, Howie AJ, Wang S, Carney CK, Masterson TS, Amin T, Wright DW, Wilson MT, Oates JA, Roberts LJ 2nd: Acetaminophen inhibits hemoprotein-catalyzed lipid peroxidation and attenuates rhabdomyolysis-induced renal failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 2699–2704, 2010. 10.1073/pnas.0910174107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishida K, Watanabe H, Ogaki S, Kodama A, Tanaka R, Imafuku T, Ishima Y, Chuang VT, Toyoda M, Kondoh M, Wu Q, Fukagawa M, Otagiri M, Maruyama T: Renoprotective effect of long acting thioredoxin by modulating oxidative stress and macrophage migration inhibitory factor against rhabdomyolysis-associated acute kidney injury. Sci Rep 5: 14471, 2015. 10.1038/srep14471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guerrero-Hue M, García-Caballero C, Palomino-Antolín A, Rubio-Navarro A, Vázquez-Carballo C, Herencia C, Martín-Sanchez D, Farré-Alins V, Egea J, Cannata P, Praga M, Ortiz A, Egido J, Sanz AB, Moreno JA: Curcumin reduces renal damage associated with rhabdomyolysis by decreasing ferroptosis-mediated cell death. FASEB J 33: 8961–8975, 2019. 10.1096/fj.201900077R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clark AJ, Parikh SM: Targeting energy pathways in kidney disease: The roles of sirtuins, AMPK, and PGC1α. Kidney Int 99: 828–840, 2021. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Hepokoski M, Gu W, Simonson T, Singh P: Targeting mitochondria and metabolism in acute kidney injury. J Clin Med 10: 3991, 2021. 10.3390/jcm10173991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang C, Cai J, Yin XM, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA, Dong Z: Mitochondrial quality control in kidney injury and repair. Nat Rev Nephrol 17: 299–318, 2021. 10.1038/s41581-020-00369-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh RD, Croatt AJ, Ackerman AW, Grande JP, Trushina E, Salisbury JL, Christensen T, Adams CM, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, Nath KA: Prominent mitochondrial injury as an early event in heme protein-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney360 3: 1672–1682, 2022. 10.34067/KID.0004832022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qian Q, Nath KA, Wu Y, Daoud TM, Sethi S: Hemolysis and acute kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 780–784, 2010. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zager RA, Johnson AC: Progressive histone alterations and proinflammatory gene activation: Consequences of heme protein/iron-mediated proximal tubule injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F827–F837, 2010. 10.1152/ajprenal.00683.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shulman LM, Yuhas Y, Frolkis I, Gavendo S, Knecht A, Eliahou HE: Glycerol induced ARF in rats is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Kidney Int 43: 1397–1401, 1993. 10.1038/ki.1993.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanakiriya SK, Croatt AJ, Haggard JJ, Ingelfinger JR, Tang SS, Alam J, Nath KA: Heme: A novel inducer of MCP-1 through HO-dependent and HO-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F546–F554, 2003. 10.1152/ajprenal.00298.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin W, Wu X, Wen J, Fei Y, Wu J, Li X, Zhang Q, Dong Y, Xu T, Fan Y, Wang N: Nicotinamide retains Klotho expression and ameliorates rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Nutrition 91-92: 111376, 2021. 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi Y, Xu L, Tang J, Fang L, Ma S, Ma X, Nie J, Pi X, Qiu A, Zhuang S, Liu N: Inhibition of HDAC6 protects against rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F502–F515, 2017. 10.1152/ajprenal.00546.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nath KA, Belcher JD, Nath MC, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, Ackerman AW, Katusic ZS, Vercellotti GM: Role of TLR4 signaling in the nephrotoxicity of heme and heme proteins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 314: F906–F914, 2018. 10.1152/ajprenal.00432.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Belliere J, Casemayou A, Ducasse L, Zakaroff-Girard A, Martins F, Iacovoni JS, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Buffin-Meyer B, Pipy B, Chauveau D, Schanstra JP, Bascands JL: Specific macrophage subtypes influence the progression of rhabdomyolysis-induced kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1363–1377, 2015. 10.1681/ASN.2014040320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okubo K, Kurosawa M, Kamiya M, Urano Y, Suzuki A, Yamamoto K, Hase K, Homma K, Sasaki J, Miyauchi H, Hoshino T, Hayashi M, Mayadas TN, Hirahashi J: Macrophage extracellular trap formation promoted by platelet activation is a key mediator of rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Nat Med 24: 232–238, 2018. 10.1038/nm.4462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dutra FF, Alves LS, Rodrigues D, Fernandez PL, de Oliveira RB, Golenbock DT, Zamboni DS, Bozza MT: Hemolysis-induced lethality involves inflammasome activation by heme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E4110–E4118, 2014. 10.1073/pnas.1405023111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giuliani KTK, Kassianos AJ, Healy H, Gois PHF: Pigment nephropathy: Novel insights into inflammasome-mediated pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 20: 1997, 2019. 10.3390/ijms20081997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grivei A, Giuliani KTK, Wang X, Ungerer J, Francis L, Hepburn K, John GT, Gois PFH, Kassianos AJ, Healy H: Oxidative stress and inflammasome activation in human rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Free Radic Biol Med 160: 690–695, 2020. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Komada T, Usui F, Kawashima A, Kimura H, Karasawa T, Inoue Y, Kobayashi M, Mizushina Y, Kasahara T, Taniguchi S, Muto S, Nagata D, Takahashi M: Role of NLRP3 inflammasomes for rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Sci Rep 5: 10901, 2015. 10.1038/srep10901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Song SJ, Kim SM, Lee SH, Moon JY, Hwang HS, Kim JS, Park SH, Jeong KH, Kim YG: Rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI was ameliorated in NLRP3 KO mice via alleviation of mitochondrial lipid peroxidation in renal tubular cells. Int J Mol Sci 21: 8564, 2020. 10.3390/ijms21228564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang S, Zhang C, Li J, Niyazi S, Zheng L, Xu M, Rong R, Yang C, Zhu T: Erythropoietin protects against rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury by modulating macrophage polarization. Cell Death Dis 8: e2725, 2017. 10.1038/cddis.2017.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wei Q, Hill WD, Su Y, Huang S, Dong Z: Heme oxygenase-1 induction contributes to renoprotection by G-CSF during rhabdomyolysis-associated acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F162–F170, 2011. 10.1152/ajprenal.00438.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boudhabhay I, Poillerat V, Grunenwald A, Torset C, Leon J, Daugan MV, Lucibello F, El Karoui K, Ydee A, Chauvet S, Girardie P, Sacks S, Farrar CA, Garred P, Berthaud R, Le Quintrec M, Rabant M, de Lonlay P, Rambaud C, Gnemmi V, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Frimat M, Roumenina LT: Complement activation is a crucial driver of acute kidney injury in rhabdomyolysis. Kidney Int 99: 581–597, 2021. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang X, Zhao W, Zhang L, Yang X, Wang L, Chen Y, Wang J, Zhang C, Wu G: The role of complement activation in rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. PLoS One 13: e0192361, 2018. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zager RA, Gamelin LM: Pathogenetic mechanisms in experimental hemoglobinuric acute renal failure. Am J Physiol 256: F446–F455, 1989. 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.3.F446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.El-Achkar TM, Wu XR: Uromodulin in kidney injury: An instigator, bystander, or protector? Am J Kidney Dis 59: 452–461, 2012. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Micanovic R, LaFavers K, Garimella PS, Wu XR, El-Achkar TM: Uromodulin (Tamm–Horsfall protein): Guardian of urinary and systemic homeostasis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 33–43, 2020. 10.1093/ndt/gfy394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haase M, Haase-Fielitz A, Bagshaw SM, Ronco C, Bellomo R: Cardiopulmonary bypass-associated acute kidney injury: A pigment nephropathy? Contrib Nephrol 156: 340–353, 2007. 10.1159/000102125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nath KA, Hebbel RP: Sickle cell disease: Renal manifestations and mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 161–171, 2015. 10.1038/nrneph.2015.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nath KA, Vercellotti GM, Grande JP, Miyoshi H, Paya CV, Manivel JC, Haggard JJ, Croatt AJ, Payne WD, Alam J: Heme protein-induced chronic renal inflammation: Suppressive effect of induced heme oxygenase-1. Kidney Int 59: 106–117, 2001. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kerchberger VE, Ware LB: The role of circulating cell-free hemoglobin in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 40: 148–159, 2020. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wester-Rosenlöf L, Casslén V, Axelsson J, Edström-Hägerwall A, Gram M, Holmqvist M, Johansson ME, Larsson I, Ley D, Marsal K, Mörgelin M, Rippe B, Rutardottir S, Shohani B, Akerström B, Hansson SR: A1M/α1-microglobulin protects from heme-induced placental and renal damage in a pregnant sheep model of preeclampsia. PLoS One 9: e86353, 2014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Agarwal A, Dong Z, Harris R, Murray P, Parikh SM, Rosner MH, Kellum JA, Ronco C; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative XIII Working Group : Cellular and molecular mechanisms of AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1288–1299, 2016. 10.1681/ASN.2015070740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Piagnerelli M, Boudjeltia KZ, Vanhaeverbeek M, Vincent JL: Red blood cell rheology in sepsis. Intensive Care Med 29: 1052–1061, 2003. 10.1007/s00134-003-1783-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shaver CM, Paul MG, Putz ND, Landstreet SR, Kuck JL, Scarfe L, Skrypnyk N, Yang H, Harrison FE, de Caestecker MP, Bastarache JA, Ware LB: Cell-free hemoglobin augments acute kidney injury during experimental sepsis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 317: F922–F929, 2019. 10.1152/ajprenal.00375.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Joffre J, Hellman J, Ince C, Ait-Oufella H: Endothelial responses in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 202: 361–370, 2020. 10.1164/rccm.201910-1911TR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Larsen R, Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Tokaji L, Bozza FA, Japiassú AM, Bonaparte D, Cavalcante MM, Chora A, Ferreira A, Marguti I, Cardoso S, Sepúlveda N, Smith A, Soares MP: A central role for free heme in the pathogenesis of severe sepsis. Sci Transl Med 2: 51ra71, 2010. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nath KA, Grande JP, Belcher JD, Garovic VD, Croatt AJ, Hillestad ML, Barry MA, Nath MC, Regan RF, Vercellotti GM: Antithrombotic effects of heme-degrading and heme-binding proteins. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 318: H671–H681, 2020. 10.1152/ajpheart.00280.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nath KA, Croatt AJ, Haggard JJ, Grande JP: Renal response to repetitive exposure to heme proteins: Chronic injury induced by an acute insult. Kidney Int 57: 2423–2433, 2000. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hill PA, Davies DJ, Kincaid-Smith P, Ryan GB: Ultrastructural changes in renal tubules associated with glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 36: 992–997, 1989. 10.1038/ki.1989.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Madsen KM, Applegate CW, Tisher CC: Phagocytosis of erythrocytes by the proximal tubule of the rat kidney. Cell Tissue Res 226: 363–374, 1982. 10.1007/BF00218366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vivante A, Afek A, Frenkel-Nir Y, Tzur D, Farfel A, Golan E, Chaiter Y, Shohat T, Skorecki K, Calderon-Margalit R: Persistent asymptomatic isolated microscopic hematuria in Israeli adolescents and young adults and risk for end-stage renal disease. JAMA 306: 729–736, 2011. 10.1001/jama.2011.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lim SK, Kim H, Lim SK, bin Ali A, Lim YK, Wang Y, Chong SM, Costantini F, Baumman H: Increased susceptibility in Hp knockout mice during acute hemolysis. Blood 92: 1870–1877, 1998. 10.1182/blood.V92.6.1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kubota K, Egi M, Mizobuchi S: Haptoglobin administration in cardiovascular surgery patients: Its association with the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury. Anesth Analg 124: 1771–1776, 2017. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ofori-Acquah SF, Hazra R, Orikogbo OO, Crosby D, Flage B, Ackah EB, Lenhart D, Tan RJ, Vitturi DA, Paintsil V, Owusu-Dabo E, Ghosh S; SickleGenAfrica Network : Hemopexin deficiency promotes acute kidney injury in sickle cell disease. Blood 135: 1044–1048, 2020. 10.1182/blood.2019002653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kristiansson A, Davidsson S, Johansson ME, Piel S, Elmér E, Hansson MJ, Åkerström B, Gram M: α1-Microglobulin (A1M) protects human proximal tubule epithelial cells from heme-induced damage in vitro. Int J Mol Sci 21: 5825, 2020. 10.3390/ijms21165825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scindia Y, Dey P, Thirunagari A, Liping H, Rosin DL, Floris M, Okusa MD, Swaminathan S: Hepcidin mitigates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulating systemic iron homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2800–2814, 2015. 10.1681/ASN.2014101037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Swelm RPL, Vos M, Verhoeven F, Thévenod F, Swinkels DW: Endogenous hepcidin synthesis protects the distal nephron against hemin and hemoglobin mediated necroptosis. Cell Death Dis 9: 550, 2018. 10.1038/s41419-018-0568-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nath KA: The role of renal research in demonstrating the protective properties of heme oxygenase-1. Kidney Int 84: 3–6, 2013. 10.1038/ki.2013.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nath KA: Heme oxygenase-1: A provenance for cytoprotective pathways in the kidney and other tissues. Kidney Int 70: 432–443, 2006. 10.1038/sj.ki.5001565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nath KA: Heme oxygenase-1 and acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 23: 17–24, 2014. 10.1097/01.mnh.0000437613.88158.d3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bolisetty S, Zarjou A, Agarwal A: Heme oxygenase 1 as a therapeutic target in acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 531–545, 2017. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.10.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vogt BA, Shanley TP, Croatt A, Alam J, Johnson KJ, Nath KA: Glomerular inflammation induces resistance to tubular injury in the rat. A novel form of acquired, heme oxygenase-dependent resistance to renal injury. J Clin Invest 98: 2139–2145, 1996. 10.1172/JCI119020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Balla G, Jacob HS, Balla J, Rosenberg M, Nath K, Apple F, Eaton JW, Vercellotti GM: Ferritin: A cytoprotective antioxidant strategem of endothelium. J Biol Chem 267: 18148–18153, 1992. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)37165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zarjou A, Bolisetty S, Joseph R, Traylor A, Apostolov EO, Arosio P, Balla J, Verlander J, Darshan D, Kuhn LC, Agarwal A: Proximal tubule H-ferritin mediates iron trafficking in acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 123: 4423–4434, 2013. 10.1172/JCI67867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Taguchi K, Ogaki S, Nagasaki T, Yanagisawa H, Nishida K, Maeda H, Enoki Y, Matsumoto K, Sekijima H, Ooi K, Ishima Y, Watanabe H, Fukagawa M, Otagiri M, Maruyama T: Carbon monoxide rescues the developmental lethality of experimental rat models of rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 372: 355–365, 2020. 10.1124/jpet.119.262485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Leung N, Croatt AJ, Haggard JJ, Grande JP, Nath KA: Acute cholestatic liver disease protects against glycerol-induced acute renal failure in the rat. Kidney Int 60: 1047–1057, 2001. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0600031047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ramos S, Carlos AR, Sundaram B, Jeney V, Ribeiro A, Gozzelino R, Bank C, Gjini E, Braza F, Martins R, Ademolue TW, Blankenhaus B, Gouveia Z, Faísca P, Trujillo D, Cardoso S, Rebelo S, Del Barrio L, Zarjou A, Bolisetty S, Agarwal A, Soares MP: Renal control of disease tolerance to malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 5681–5686, 2019. 10.1073/pnas.1822024116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Alam J, Killeen E, Gong P, Naquin R, Hu B, Stewart D, Ingelfinger JR, Nath KA: Heme activates the heme oxygenase-1 gene in renal epithelial cells by stabilizing Nrf2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F743–F752, 2003. 10.1152/ajprenal.00376.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kadıoğlu E, Tekşen Y, Koçak C, Koçak FE: Beneficial effects of bardoxolone methyl, an Nrf2 activator, on crush-related acute kidney injury in rats. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 47: 241–250, 2021. 10.1007/s00068-019-01216-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rubio-Navarro A, Vázquez-Carballo C, Guerrero-Hue M, García-Caballero C, Herencia C, Gutiérrez E, Yuste C, Sevillano Á, Praga M, Egea J, Cannata P, Cortegano I, de Andrés B, Gaspar ML, Cadenas S, Michalska P, León R, Ortiz A, Egido J, Moreno JA: Nrf2 plays a protective role against intravascular hemolysis-mediated acute kidney injury. Front Pharmacol 10: 740, 2019. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Uchida A, Kidokoro K, Sogawa Y, Itano S, Nagasu H, Satoh M, Sasaki T, Kashihara N: 5-Aminolevulinic acid exerts renoprotective effect via Nrf2 activation in murine rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 28–38, 2019. 10.1111/nep.13189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wu J, Pan X, Fu H, Zheng Y, Dai Y, Yin Y, Chen Q, Hao Q, Bao D, Hou D: Effect of curcumin on glycerol-induced acute kidney injury in rats. Sci Rep 7: 10114, 2017. 10.1038/s41598-017-10693-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Johnson ACM, Delrow JJ, Zager RA: Tin protoporphyrin activates the oxidant-dependent NRF2-cytoprotective pathway and mitigates acute kidney injury. Transl Res 186: 1–18, 2017. 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Frostad KB: Combined iron sucrose and protoporphyrin treatment protects against ischemic and toxin-mediated acute renal failure. Kidney Int 90: 67–76, 2016. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yamaoka M, Shimizu H, Takahashi T, Omori E, Morimatsu H: Dynamic changes in Bach1 expression in the kidney of rhabdomyolysis-associated acute kidney injury. PLoS One 12: e0180934, 2017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Collino F, Bruno S, Incarnato D, Dettori D, Neri F, Provero P, Pomatto M, Oliviero S, Tetta C, Quesenberry PJ, Camussi G: AKI recovery induced by mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles carrying microRNAs. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2349–2360, 2015. 10.1681/ASN.2014070710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]