Abstract

Cystatin C has been shown to be a reliable and accurate marker of kidney function across diverse populations. The 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommended using cystatin C to confirm the diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) determined by creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and to estimate kidney function when accurate eGFR estimates are needed for clinical decision-making. In the efforts to remove race from eGFR calculations in the United States, the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Joint Task Force recommended increasing availability and clinical adoption of cystatin C to assess kidney function. This review summarizes the key advantages and limitations of cystatin C use in clinical practice. Our goals were to review and discuss the literature on cystatin C; understand the evidence behind the recommendations for its use as a marker of kidney function to diagnose CKD and risk stratify patients for adverse outcomes; discuss the challenges of its use in clinical practice; and guide clinicians on its interpretation.

Keywords: clinical nephrology, cystatin C, eGFR

Introduction

Recent years have brought on a reckoning of the use of race in medicine. For example, the National Kidney Foundation and American Society of Nephrology Joint Task Force recommended the adoption of a race-free creatinine-based GFR equation (eGFRcr) (1). Although this represents a step toward equity in kidney disease diagnosis, the new eGFRcr equation developed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology (CKD-EPI) Consortium is less accurate compared with its predecessor and eGFR equations that include cystatin C (CysC). Consequently, the Task Force also recommended increasing the availability and adoption of CysC into clinical practice.

Although CysC testing availability remains limited, the Task Force’s recommendations have prompted several health systems to adopt CysC testing. As observed in our institutions where CysC testing has been available, we anticipate that its use will beget further use as clinicians recognize CysC’s merits relative to serum creatinine (sCr).

Herein, we summarize the literature supporting CysC as a kidney function biomarker and provide guidance on how to incorporate CysC into clinical practice. Specifically, this review serves to address the following questions: (1) How does CysC differ from sCr as a marker of kidney function? (2) What is the epidemiologic evidence supporting CysC’s role in kidney disease detection, staging, and prognosis? (3) What are health system barriers in CysC adoption? (4) How should clinicians approach clinical decision making when using CysC in conjunction with sCr? (5) Where should we go from here with CysC testing?

CysC as a Marker of GFR

CysC is a 13-kDa low-molecular-weight protein that is produced constantly by all nucleated cells, freely filtered at the glomerulus, and metabolized in the proximal tubule (1). Although both sCr and CysC are affected by non-GFR factors, CysC appears to be affected by fewer factors (Table 1) and is influenced to a lesser extent than sCr (2–4). sCr levels are known to be affected by age, sex, muscle mass, physical activity, nutritional status, and protein intake (5–9), whereas systemic inflammation, adiposity, thyroid disease, and steroid use have been reported as non-GFR determinants of CysC (2–5,10,11).

Table 1.

| Creatinine | Cystatin C |

|---|---|

| Muscle mass/physical activity | Steroids |

| Dietary protein intake | Thyroid dysfunction |

| Functional status (i.e., frailty) | Adiposity |

| Factors affecting tubular creatinine secretion (e.g., medications) | Inflammation |

Compared with sCr, CysC is more uniformly produced across diverse populations; therefore, the CysC-based eGFR equation (eGFRcys) does not include an adjustment for race (12). Conversely, eGFRcr equations have previously included an adjustment for Black race on the basis of studies that showed higher sCr levels at the same measured GFR (mGFR) in Black versus non-Black individuals (12,13). In 2021, the CKD-EPI Consortium developed and validated new eGFR equations for sCr alone and in combination with CysC (eGFRcr-cys) that adjusted only for age and sex. Table 2 summarizes the bias and accuracy, represented by the proportion of eGFR within 30% of mGFR, of these new equations compared with eGFRcys. eGFRcys was the least biased equation among both Black and non-Black participants (12,13). Compared with eGFRcys, the new eGFRcr-cys equation had similar bias among Black participants and overestimated mGFR by 3 ml/min per 1.73 m2 among non-Black participants; however, it had the highest accuracy among the three equations (13). Whether eGFRcys’s lower accuracy stems from issues of CysC assay standardization across studies remains unclear. Nonetheless, these results support the use of CysC as a kidney function biomarker across diverse populations within the United States.

Table 2.

Performance of the CysC-based eGFR equation and the 2021 creatinine-based eGFR equations alone and combined with CysC by race (13)

| eGFR Equation | Black Participants | Non-Black Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Bias, median difference between mGFR and eGFR (95% CI) | ||

| AS-eGFRcr | 3.6 (1.8 to 5.5) | −3.9 (–4.4 to –3.4) |

| eGFRcys | −0.1 (–1.5 to 1.6) | 0.7 (0.2 to 1.2) |

| AS-eGFRcr-cysc | 0.1 (–0.9 to 1.6) | −2.9 (–3.3 to –2.5) |

| Accuracy, P30: proportion of eGFR within 30% of mGFR (95% CI) | ||

| AS-eGFRcr | 87.2 (84.5 to 90) | 86.5 (85.4 to 87.6) |

| eGFRcys | 84.6 (81.7 to 87.6) | 88.9 (87.9 to 89.9) |

| AS-eGFRcr-cysc | 90.5 (88.1 to 92.9) | 90.8 (89.9 to 91.8) |

CysC, cystatin C; AS-eGFRcr, creatinine-based eGFR rate adjusted for age and sex; eGFRcysc, cystatin C-based eGFR adjusted for age and sex; AS-eGFRcr-cysc, creatinine- and cystatin C-based eGFR adjusted for age and sex; mGFR, measured GFR; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

CysC’s Role in Kidney Disease Detection and Prognostication

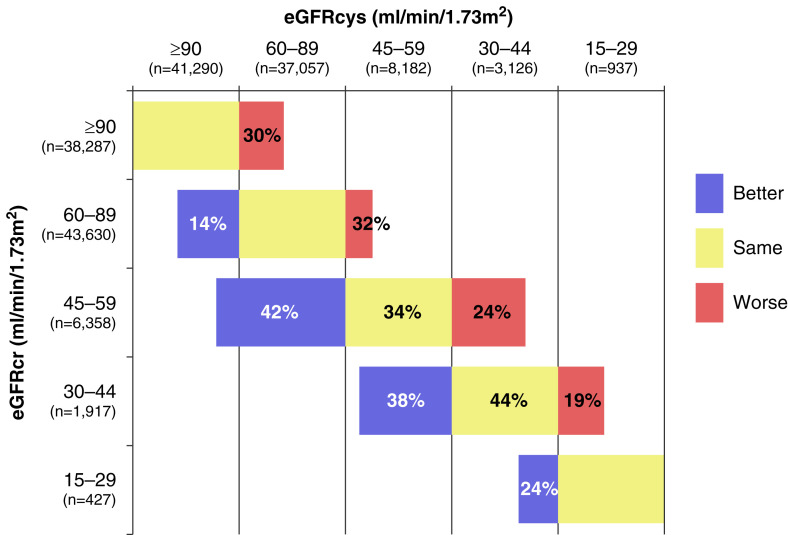

Detection and staging of CKD are integral for risk stratification because CKD confers elevated risks for adverse clinical outcomes, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), ESKD, and mortality (14,15). In a meta-analysis of 11 studies with more than 90,000 participants from general populations cohorts, the prevalence of an eGFR of <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was 10% by sCr and 14% by CysC (16). Of the 37,057 individuals with an eGFRcr of 60–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2, eGFRcys reclassified 14% to <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Among those with an eGFRcr of 45–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2, CysC reclassified 42% of individuals into lower eGFR categories and 24% into higher eGFR categories (Figure 1) (16).

Figure 1.

CKD stage reclassification by the cystatin C–based eGFR equation relative to the race-free creatinine-based GFR equation (16).

Moreover, eGFRcys reclassification to a less severe CKD stage compared with eGFRcr was associated with a reduced risk of ESKD, whereas eGFRcys reclassification to a worse CKD stage was associated with an increased risk (16). These findings have been consistent across studies. Among 26,643 US adults in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study, individuals who were reclassified to a more advanced CKD stage by eGFRcys had a four-fold higher ESKD risk than those who were reclassified to earlier CKD stages (17). In the Cardiovascular Health Study, an eGFR of <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was associated with an elevated risk of ESKD only if confirmed by CysC (18).

Although ESKD is an important outcome for individuals with kidney disease, most patients with CKD die before progressing to ESKD (19–21). Within the last 20 years, multiple large-scale observational studies and a meta-analysis including participants with and without CKD have shown that CysC has stronger, more linear associations with mortality and CVD risk than sCr (2,3,16,17,22–24). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that CysC identifies a substantial subgroup of individuals with high-risk CKD who may go unrecognized by sCr and provide strong evidence supporting the utility of CysC for accurate detection, staging, and risk stratification of patients with CKD.

Health System–Related Barriers to Adopting CysC Testing

In a 2020 survey of a subset of nephrology respondents of the International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas, 67% reported that CysC testing was available within their region (25). However, the 2019 General Chemistry Survey of the College of American Pathologists showed that only 7% of US clinical laboratories offered CysC tests, with >90% of these labs referring CysC testing to external commercial labs (26).

Concerns for assay accuracy and agreement across laboratories have impeded broader clinical CysC adoption. To address these concerns, certified reference materials (ERM-DA471/IFCC), which enable assay manufacturers to calibrate their methods, were made available in 2010. All major Food and Drug Administration–approved manufacturers of CysC reagents now have methods traceable to the reference material. An earlier assessment of eight automated CysC assays using serum samples with known CysC concentrations demonstrated that although most assays yielded acceptable accuracy across all concentrations, bias remained suboptimal, with biases from –3% to as high as 20% (27). Moreover, the assay performance varied according to the analyzer used. Similar issues across measurement methods were noted in the 2014 CAP Cystatin C Proficiency Testing Program (28). Conversely, a 2019 study by the same CAP program found much improved accuracy and agreement across CysC measurement methods, with coefficients of variation <10% and biases of <0.9% for healthy and CKD samples (26). Although certified reference measurement procedures are still needed to attain a similar level of confidence in assay performance to that for sCr measurements (26), these recent findings are reassuring as clinical use of CysC grows.

Second, concerns of assay cost and excessive CysC testing are pervasive among health care systems. Because CysC assays can run on standard analyzers housed in most laboratories, CysC and sCr testing have similar labor costs. However, CysC reagents cost around $5–$10 per test compared with around $0.50 per test for sCr within the US; this cost differential will likely decline as CysC testing increases. In cost simulations of implementing CysC testing using the Gentian assay in Canada, the cost was estimated to be $2.88 per test for 1200 tests per year versus $2.17 per test on the basis of 10,000 tests per year (29). The reimbursement profile for CysC testing also appears favorable for most clinical laboratories. The 2021 Medicare Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory Fee Schedule lists CysC reimbursement at $18.52 per test versus $5.12–$10.56 per test for sCr (30). However, CysC testing reimbursement is determined by local policies, and clinicians must document that each of the following conditions are met: (1) the patient has an eGFRcr of 45–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; (2) eGFR warrants confirmation because eGFRcr is thought to be inaccurate; and (3) eGFR warrants confirmation for clinical decision making (31). As the medical community moves toward race-free kidney function measurement, these conditions for Medicare reimbursement of CysC deserve reconsideration and revision.

The third major barrier is clinicians’ awareness of CysC’s utility and comfort with using CysC in routine clinical practice. During the successful implementation of CysC in three Canadian medical centers, clinical champions who recognized CysC’s value as a filtration biomarker were instrumental in advocating to laboratory leaders for CysC adoption. Within the Mayo Clinic where CysC testing has been available for >8 years, a qualitative study among 15 clinicians examined hospitalists’, nephrologists’, and pharmacists’ perceptions of CysC testing in the inpatient setting (32). Although all clinicians believed that CysC reflects kidney health more accurately than sCr, their knowledge and overall comfort with using CysC ranged from “novice” to “expert.” Table 3 summarizes the factors influencing CysC use that were identified. Consistent with prior literature, the strongest facilitator leading to enhanced CysC use was interaction with knowledgeable colleagues. This finding parallels patterns seen with other diagnostic tests, such as procalcitonin, in which multiple modalities were needed to facilitate sustained uptake (33).

Table 3.

Factors found to influence cystatin C use in the Mayo health system (32)

| Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|

| Absence of institutional practice guidance and policy | Team-based multidisciplinary care model |

| Lack of education provided about CysC | Formal and informal education about CysC |

| Location of CysC results in EHR | Ease of test and rapid test turnaround time (<3 h) |

| Fluency with sCr versus unfamiliarity with CysC | Automated eGFR reporting in her |

| Access to knowledgeable individuals and CysC advocates |

CysC, cystatin C; EHR, electronic health record; sCr, serum creatinine.

In Whom to Measure CysC

To begin overcoming the last barrier, we share some early guidance on CysC’s use in clinical practice. The 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommend CysC testing when eGFRcr may be unreliable due to non-GFR determinants of sCr; the 2019 KDIGO Controversies Conference on CKD Screening expert panel further concluded that both sCr and CysC are needed for initial CKD diagnosis and staging. In line with these reports, we recommend at least a one-time assessment of eGFRcys for patients at high risk for CKD, particularly among patients who are frail or unusually fit or who are from groups underrepresented in the CKD-EPI collaboration cohorts. Epidemiologic observations suggest that such an approach could “un-diagnose” CKD in patients with abnormal eGFRcr but normal eGFRcys and no albuminuria. Because these patients are unlikely to progress to ESKD (34), CysC testing enables clinicians to reassure such patients that their abnormal eGFRcr is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. Importantly, eGFRcys can also identify occult kidney disease (35) and restage CKD. More accurate CKD staging can re-enforce interventions to mitigate risks for CKD progression and CVD and to prioritize nephrology referrals.

In addition, eGFRcys may guide decision making surrounding medication dosing and interventions. The 2012 KDIGO CKD guidelines suggest CysC testing when precision is needed for dosing of medications with narrow therapeutic windows. However, many drug dosing guidelines still rely on thresholds of creatinine clearance (CrCl) on the basis of the Cockcroft–Gault equation for dosing. In contrast, a systematic review of 28 studies (around 3500 patients), which evaluated CysC’s use in predicting drug clearance of 16 different medications, including antibiotics and anticoagulants, showed that eGFRcys predicted observed drug clearance and blood concentrations as well or better than sCr in nearly all studies (36). The most studied medication is vancomycin, wherein eGFRcys predicted its drug clearance and trough levels better than eGFRcr. Among critically ill patients, a vancomycin dosing algorithm that included CysC doubled the proportion of patients who reached target trough levels compared with usual care (37) and improved vancomycin dosing in overweight and obese hospitalized patients (38). Although further studies are needed for drugs with important consequences when under- or over-dosed, such as chemotherapeutic agents, we believe that eGFRcys may be an appropriate alternative to CrCl for some drug dosing decisions.

Approach to Patients with Discrepant eGFRs by CysC versus Creatinine

Clinicians will commonly encounter patients with discordant GFR estimates on the basis of sCr versus CysC. Among participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study, approximately one-third had eGFRcr and eGFRcys values that differed by ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Individuals with eGFRcys values that were much lower than eGFRcr values generally were older, had a greater comorbidity burden, and had more proteinuria than individuals who had concordant or higher eGFRcys values relative to eGFRcr values. These differences between eGFRcr and eGFRcys are prognostic of ESKD, hospitalization, CVD, and mortality (39–41). For an individual patient, the interpretation of the various eGFR estimates is crucial for clinical decision making. Below, we present cases that highlight such clinical scenarios.

Case 1

A 75-year-old woman with hypertension for 30 years, coronary artery disease status-post two prior coronary artery bypasses, and well-controlled HIV, was referred for evaluation for CKD.

Two months ago, her sCr was 1.6 mg/dl (eGFRcr=33 ml/min per 1.73 m2) on routine testing. Confirmatory labs a week later showed an eGFRcr of 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and a concurrent CysC of 1.3 mg/L (eGFRcys=48 ml/min per 1.73 m2). She stated that she had switched to an antiretroviral regimen comprising dolutegravir and rilpivirine a few months ago, and that she was currently training for her 20th marathon.

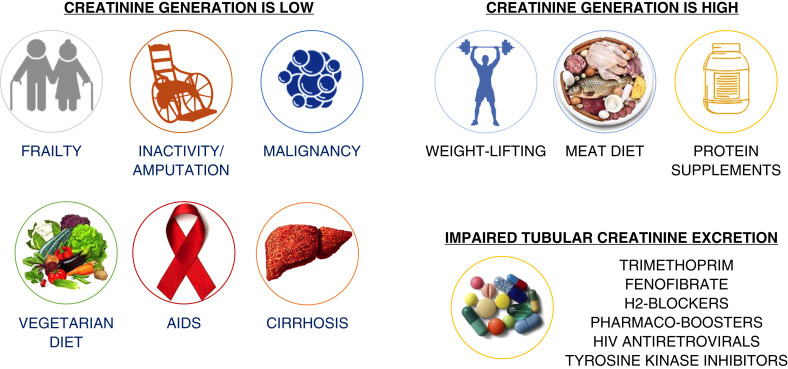

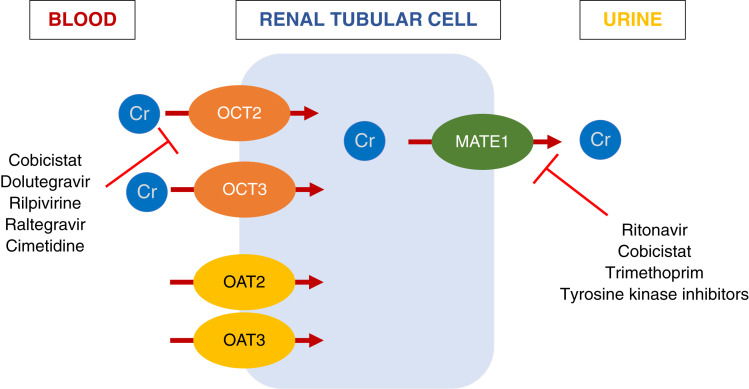

On the basis of her eGFRcr, she was referred to nephrology for evaluation of advanced CKD. However, her elevated sCr is likely explained by enhanced creatinine production from high muscle turnover and impairment of creatinine tubular secretion by dolutegravir and rilpivirine rather from impaired kidney function. Figure 2 shows several scenarios in which non-GFR factors may affect sCr levels, and Figure 3 shows a list of medications known to impair creatinine tubular secretion through interference of basolateral and apical transporters (42–45).

Figure 2.

Clinical scenarios in which serum creatinine is likely influenced by non-GFR factors.

Figure 3.

Drug effects on kidney tubular creatinine secretion (42–45).

Case 2

A healthy 60-year-old man with a baseline sCr of 1.1 mg/dl (eGFRcr=77 ml/min per 1.73 m2), was admitted for injuries related to a motor vehicle accident.

On presentation, the patient had a creatine kinase level of >20,000 IU/L, with non-oliguric acute kidney injury (AKI) from rhabdomyolysis. He was treated with intravenous fluids. Although the patient’s myalgia and creatine kinase were improving, his sCr rose to 7.1 mg/dl over the ensuing days. His only electrolyte derangement was an elevated serum phosphorus level of 6.4 mg/dl, and his urine output remained robust. The nephrology team was asked whether the patient required dialysis initiation on the basis of his seemingly worsening kidney function; however, a concurrent CysC level at his peak sCr level was 1.2 mg/L, suggesting a much better kidney function.

Because sCr derives from muscle metabolism, rhabdomyolysis leads to significant elevations in sCr that do not necessarily reflect underlying kidney injury (46). Moreover, due to sCr’s distribution in total body water versus CysC’s distribution in extracellular fluid and differences in how they are handled by kidney tubules, CysC levels reach steady state much faster than sCr; thus, CysC may reflect changes in GFR more quickly and accurately in this clinical context (47–49). More studies are needed to evaluate CysC’s potential role in early detection of AKI and monitoring kidney function during prolonged hospitalizations during which sCr may decline due to diminished physical activity and worsened nutritional status.

Case 3

A 67-year-old woman with a history of smoking and hypothyroidism on thyroid replacement therapy, presented to the primary care clinic with 15-pound weight loss and hematuria.

After a broad workup, she was diagnosed with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Her sCr was 0.9 mg/dl (eGFRcr=70 ml/min per 1.73 m2, CrCl=65 ml/min) and CysC was 1.7 mg/L (eGFRcys=35 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Cisplatin was part of a curative chemotherapy regimen for her; however, its use should be avoided in patients with a CrCl of <60 ml/min (50).

Given this patient’s weight loss and new malignancy, she likely underproduces sCr, leading to falsely elevated creatinine-based kidney function estimates. On the other hand, smoking and thyroid dysfunction may increase CysC levels, leading to underestimation of kidney function by eGFRcys. In this scenario, we recommend obtaining mGFR, using exogenous filtration markers such as iothalamate or iohexol, to determine eligibility and dosing of curative chemotherapy. We caution against using 24-hour urinary CrCl because collection errors commonly occur, leading to imprecise measures of kidney function (51).

From our collective clinical experiences, when eGFRcys and eGFRcr differ widely (by ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2), there are likely non-GFR factors disproportionately affecting one biomarker relative to the other. Although the combined CKD-EPI equation is the most accurate eGFR equation (13), this equation was developed among a relatively healthy population with a mean age of 47 years and a mean mGFR of 68 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Overall, real-world patients who are seen in the nephrology clinic tend to be older and have more comorbidities, resulting in a higher prevalence of non-GFR factors, such as low muscle mass, which affect levels of creatinine more than CysC. Nevertheless, when eGFRcys and eGFRcr are highly discordant, choosing which eGFR to use for clinical decision making remains complex, particularly in the inpatient setting, and should be individualized. Both eGFRcys and eGFRcr are approximations of true kidney function, with a greater margin of error at higher levels of kidney function. Therefore, both sCr and CysC require careful interpretation among patients with non-GFR determinants of their serum concentrations.

Future Potential Use of CysC

The growing availability of CysC testing offers an opportunity to evaluate its use beyond that of a confirmatory test for eGFRcr. Emerging research implicates that CysC may have additional value when measured longitudinally within an individual and in the context of transplant nephrology. Chen et al. (39) have shown that among individuals with CKD, those with a faster decline in eGFRcys relative to eGFRcr had higher risk of progression to ESKD and mortality compared with individuals in whom the two eGFRs declined in parallel. If replicated by other studies, these findings suggest that CysC may identify individuals whose CKD progression could be underappreciated due to the stability of sCr in the setting of worsening overall health.

CysC may have a role in facilitating earlier kidney transplant waitlist registration in some individuals with high-risk CKD and help mitigate racial disparities in kidney transplantation. Although racial disparities in predialysis accruable waiting time between Black and White people in the CRIC Study were not alleviated by the use of eGFRcys (52), CysC may help identify individuals with a higher risk of ESKD irrespective of race. In addition, the use of eGFRcys may identify potential kidney transplant donors at risk for the development of CKD. In the perioperative period, CysC appeared to predict delayed graft function better than sCr in a retrospective China-based study (53). A few small studies (54–57) including stable kidney transplant recipients found that CysC-based equations more closely approximated mGFR than sCr-based equations; however, these studies were performed before the CKD-EPI eGFRcys equation was created (12).

Conclusion

After nearly a century of relying solely on sCr for estimating kidney function, CysC is now increasingly incorporated into routine clinical practice. To optimize its clinical utility, educational efforts and sharing of experiences are needed to familiarize the nephrology field and other frontline clinical providers with its interpretation in conjunction with eGFRcr. CysC has important implications for kidney function monitoring and clinical decision making for much broader clinical contexts than CKD detection and staging; we anticipate that CysC testing in these other contexts will come as clinicians become familiar with using CysC clinically.

Disclosures

M.M. Estrella reports consultancy for Eiland & Bonnin, PC; research funding from Bayer and Booz Allen Hamilton; honoraria from the American Kidney Fund, AstraZeneca, and Boehringer Ingelheim, Inc.; and an advisory or leadership role for CJASN (editorial board member) and the American Journal of Kidney Disease (editorial board member). D.E. Rifkin reports an advisory or leadership role for the ABIM Nephrology Exam Committee and the American Journal of Kidney Disease (editorial board feature editor), and being a co-investigator, US site, for the EMPA-KIDNEY study (pending). All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

All authors were responsible for conceptualization and data curation, wrote the original draft of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Grubb A, Simonsen O, Sturfelt G, Truedsson L, Thysell H: Serum concentration of cystatin C, factor D and beta 2-microglobulin as a measure of glomerular filtration rate. Acta Med Scand 218: 499–503, 1985. 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb08880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shlipak MG, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Fried LF, Newman AB, Stehman-Breen C, Seliger SL, Kestenbaum B, Psaty B, Tracy RP, Siscovick DS: Cystatin C and prognosis for cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in elderly persons without chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 145: 237–246, 2006. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Stehman-Breen CO, Fried LF, Jenny NS, Psaty BM, Newman AB, Siscovick D, Shlipak MG; Cardiovascular Health Study : Cystatin C concentration as a risk factor for heart failure in older adults. Ann Intern Med 142: 497–505, 2005. 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grubb A, Björk J, Nyman U, Pollak J, Bengzon J, Ostner G, Lindström V: Cystatin C, a marker for successful aging and glomerular filtration rate, is not influenced by inflammation. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 71: 145–149, 2011. 10.3109/00365513.2010.546879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, Li L, Beck GJ, Joffe MM, Froissart M, Kusek JW, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS: Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int 75: 652–660, 2009. 10.1038/ki.2008.638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster MC, Levey AS, Inker LA, Shafi T, Fan L, Gudnason V, Katz R, Mitchell GF, Okparavero A, Palsson R, Post WS, Shlipak MG: Non-GFR determinants of low-molecular-weight serum protein filtration markers in the elderly: AGES-Kidney and MESA-Kidney. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 406–414, 2017. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Foster MC, Tighiouart H, Anderson AH, Beck GJ, Contreras G, Coresh J, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Hamm LL, He J, Horwitz E, Lewis J, Ricardo AC, Shou H, Townsend RR, Weir MR, Inker LA, Levey AS; CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study Investigators : Non-GFR determinants of low-molecular-weight serum protein filtration markers in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 892–900, 2016. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Beck GJ, Greene T, Coresh J, Levey AS: Changes in dietary protein intake has no effect on serum cystatin C levels independent of the glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int 79: 471–477, 2011. 10.1038/ki.2010.431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinge E, Lindergård B, Nilsson-Ehle P, Grubb A: Relationships among serum cystatin C, serum creatinine, lean tissue mass and glomerular filtration rate in healthy adults. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 59: 587–592, 1999. 10.1080/00365519950185076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight EL, Verhave JC, Spiegelman D, Hillege HL, de Zeeuw D, Curhan GC, de Jong PE: Factors influencing serum cystatin C levels other than renal function and the impact on renal function measurement. Kidney Int 65: 1416–1421, 2004. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manetti L, Pardini E, Genovesi M, Campomori A, Grasso L, Morselli LL, Lupi I, Pellegrini G, Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Martino E: Thyroid function differently affects serum cystatin C and creatinine concentrations. J Endocrinol Invest 28: 346–349, 2005. 10.1007/BF03347201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS; CKD-EPI Investigators : Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367: 20–29, 2012. 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, Crews DC, Doria A, Estrella MM, Froissart M, Grams ME, Greene T, Grubb A, Gudnason V, Gutiérrez OM, Kalil R, Karger AB, Mauer M, Navis G, Nelson RG, Poggio ED, Rodby R, Rossing P, Rule AD, Selvin E, Seegmiller JC, Shlipak MG, Torres VE, Yang W, Ballew SH, Couture SJ, Powe NR, Levey AS; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration : New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med 385: 1737–1749, 2021. 10.1056/NEJMoa2102953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004. 10.1056/NEJMoa041031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menon V, Wang X, Sarnak MJ, Hunsicker LH, Madero M, Beck GJ, Collins AJ, Kusek JW, Levey AS, Greene T: Long-term outcomes in nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 73: 1310–1315, 2008. 10.1038/ki.2008.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, Inker LA, Katz R, Polkinghorne KR, Rothenbacher D, Sarnak MJ, Astor BC, Coresh J, Levey AS, Gansevoort RT; CKD Prognosis Consortium : Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med 369: 932–943, 2013. 10.1056/NEJMoa1214234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menon V, Shlipak MG, Wang X, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens L, Kusek JW, Beck GJ, Collins AJ, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ: Cystatin C as a risk factor for outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 147: 19–27, 2007. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Judd S, Cushman M, McClellan W, Zakai NA, Safford MM, Zhang X, Muntner P, Warnock D: Detection of chronic kidney disease with creatinine, cystatin C, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and association with progression to end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA 305: 1545–1552, 2011. 10.1001/jama.2011.468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foley RN, Murray AM, Li S, Herzog CA, McBean AM, Eggers PW, Collins AJ: Chronic kidney disease and the risk for cardiovascular disease, renal replacement, and death in the United States Medicare population, 1998 to 1999. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 489–495, 2005. 10.1681/ASN.2004030203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Fan D, Ordoñez J, Lash JP, Chertow GM, Go AS: Risks for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular events, and death in Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white adults with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2892–2899, 2006. 10.1681/ASN.2005101122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH: Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med 164: 659–663, 2004. 10.1001/archinte.164.6.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Fried LF, Seliger SL, Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Stehman-Breen C: Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med 352: 2049–2060, 2005. 10.1056/NEJMoa043161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lees JS, Welsh CE, Celis-Morales CA, Mackay D, Lewsey J, Gray SR, Lyall DM, Cleland JG, Gill JMR, Jhund PS, Pell J, Sattar N, Welsh P, Mark PB: Glomerular filtration rate by differing measures, albuminuria and prediction of cardiovascular disease, mortality and end-stage kidney disease [published correction appears in Nat Med 26: 1308, 2020 10.1038/s41591-020-0996-z]. Nat Med 25: 1753–1760, 2019. 10.1038/s41591-019-0627-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shlipak MG, Wassel Fyr CL, Chertow GM, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Satterfield S, Cummings SR, Newman AB, Fried LF: Cystatin C and mortality risk in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 254–261, 2006. 10.1681/ASN.2005050545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tummalapalli SL, Shlipak MG, Damster S, Jha V, Malik C, Levin A, Johnson DW, Bello AK: Availability and affordability of kidney health laboratory tests around the globe. Am J Nephrol 51: 959–965, 2020. 10.1159/000511848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karger AB, Long T, Inker LA, Eckfeldt JH; College of American Pathologists Accuracy Based Committee and Chemistry Resource Committee : Improved performance in measurement of serum cystatin C by laboratories participating in the College of American Pathologists’ 2019 CYS survey [published online ahead of print February 22, 2022]. Arch Pathol Lab Med 10.5858/arpa.2021-0306-CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bargnoux AS, Piéroni L, Cristol JP, Kuster N, Delanaye P, Carlier MC, Fellahi S, Boutten A, Lombard C, González-Antuña A, Delatour V, Cavalier E; Société Française de Biologie Clinique (SFBC) : Multicenter evaluation of cystatin C measurement after assay standardization. Clin Chem 63: 833–841, 2017. 10.1373/clinchem.2016.264325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckfeldt JH, Karger AB, Miller WG, Rynders GP, Inker LA: Performance in measurement of serum cystatin C by laboratories participating in the College of American Pathologists 2014 CYS survey. Arch Pathol Lab Med 139: 888–893, 2015. 10.5858/arpa.2014-0427-CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ismail OZ, Bhayana V, Kadour M, Lepage N, Gowrishankar M, Filler G: Improving the translation of novel biomarkers to clinical practice: The story of cystatin C implementation in Canada: A professional practice column. Clin Biochem 50: 380–384, 2017. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services : Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files, file CLAB2022Q1. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentclinicallabfeeschedclinical-laboratory-fee-schedule-files/22clabq1. Accessed February 22, 2022

- 31.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services : Local Coverage Determination: Cystatin C Measurement. LCD ID: L37561. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/lcd.aspx?LCDId=37561&DocType=2. Accessed February 22, 2022

- 32.Markos JR, Schaepe KS, Teaford HR, Rule AD, Kashani KB, Lieske JC, Barreto EF: Clinician perspectives on inpatient cystatin C utilization: A qualitative case study at Mayo Clinic. PLoS One 15: e0243618, 2020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen I, Haug JB, Berild D, Bjørnholt JV, Jelsness-Jørgensen LP: Hospital physicians’ experiences with procalcitonin—Implications for antimicrobial stewardship; A qualitative study. BMC Infect Dis 20: 515, 2020. 10.1186/s12879-020-05246-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peralta CA, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Ix J, Fried LF, De Boer I, Palmas W, Siscovick D, Levey AS, Shlipak MG: Cystatin C identifies chronic kidney disease patients at higher risk for complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 147–155, 2011. 10.1681/ASN.2010050483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peralta CA, Muntner P, Scherzer R, Judd S, Cushman M, Shlipak MG: A risk score to guide cystatin C testing to detect occult-reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate. Am J Nephrol 42: 141–147, 2015. 10.1159/000439231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teaford HR, Barreto JN, Vollmer KJ, Rule AD, Barreto EF: Cystatin C: A primer for pharmacists. Pharmacy (Basel) 8: 35, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frazee E, Rule AD, Lieske JC, Kashani KB, Barreto JN, Virk A, Kuper PJ, Dierkhising RA, Leung N: Cystatin C-guided vancomycin dosing in critically ill patients: A quality improvement project. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 658–666, 2017. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teaford HR, Stevens RW, Rule AD, Mara KC, Kashani KB, Lieske JC, O’Horo J, Barreto EF: Prediction of vancomycin levels using cystatin C in overweight and obese patients: A retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65: e01487-20, 2020. 10.1128/AAC.01487-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen DC, Shlipak MG, Scherzer R, Bauer SR, Potok OA, Rifkin DE, Ix JH, Muiru AN, Hsu CY, Estrella MM: Association of intraindividual difference in estimated glomerular filtration rate by creatinine vs cystatin C and end-stage kidney disease and mortality. JAMA Netw Open 5: e2148940, 2022. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potok OA, Katz R, Bansal N, Siscovick DS, Odden MC, Ix JH, Shlipak MG, Rifkin DE: The difference between cystatin C- and creatinine-based estimated GFR and incident frailty: An analysis of the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). Am J Kidney Dis 76: 896–898, 2020. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Potok OA, Ix JH, Shlipak MG, Katz R, Hawfield AT, Rocco MV, Ambrosius WT, Cho ME, Pajewski NM, Rastogi A, Rifkin DE: The difference between cystatin C- and creatinine-based estimated GFR and associations with frailty and adverse outcomes: A cohort analysis of the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). Am J Kidney Dis 76: 765–774, 2020. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lepist EI, Zhang X, Hao J, Huang J, Kosaka A, Birkus G, Murray BP, Bannister R, Cihlar T, Huang Y, Ray AS: Contribution of the organic anion transporter OAT2 to the renal active tubular secretion of creatinine and mechanism for serum creatinine elevations caused by cobicistat. Kidney Int 86: 350–357, 2014. 10.1038/ki.2014.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reese MJ, Savina PM, Generaux GT, Tracey H, Humphreys JE, Kanaoka E, Webster LO, Harmon KA, Clarke JD, Polli JW: In vitro investigations into the roles of drug transporters and metabolizing enzymes in the disposition and drug interactions of dolutegravir, a HIV integrase inhibitor. Drug Metab Dispos 41: 353–361, 2013. 10.1124/dmd.112.048918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Curtis L, Nichols G, Stainsby C, Lim J, Aylott A, Wynne B, Clark A, Bloch M, Maechler G, Martin-Carpenter L, Raffi F, Min S: Dolutegravir: Clinical and laboratory safety in integrase inhibitor-naive patients. HIV Clin Trials 15: 199–208, 2014. 10.1310/hct1505-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Omote S, Matsuoka N, Arakawa H, Nakanishi T, Tamai I: Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on renal handling of creatinine by MATE1. Sci Rep 8: 9237, 2018. 10.1038/s41598-018-27672-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yap M, Lamarche J, Peguero A, Courville C: Serum cystatin C versus serum creatinine in the estimation of glomerular filtration rate in rhabdomyolysis. J Ren Care 37: 155–157, 2011. 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sjöström P, Tidman M, Jones I: The shorter T1/2 of cystatin C explains the earlier change of its serum level compared to serum creatinine. Clin Nephrol 62: 241–242, 2004. 10.5414/CNP62241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soto K, Coelho S, Rodrigues B, Martins H, Frade F, Lopes S, Cunha L, Papoila AL, Devarajan P: Cystatin C as a marker of acute kidney injury in the emergency department. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1745–1754, 2010. 10.2215/CJN.00690110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tenstad O, Roald AB, Grubb A, Aukland K: Renal handling of radiolabelled human cystatin C in the rat. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 56: 409–414, 1996. 10.3109/00365519609088795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galsky MD, Hahn NM, Rosenberg J, Sonpavde G, Hutson T, Oh WK, Dreicer R, Vogelzang N, Sternberg C, Bajorin DF, Bellmunt J: A consensus definition of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Lancet Oncol 12: 211–214, 2011. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70275-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levey AS: Measurement of renal function in chronic renal disease. Kidney Int 38: 167–184, 1990. 10.1038/ki.1990.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ku E, McCulloch CE, Adey DB, Li L, Johansen KL: Racial disparities in eligibility for preemptive waitlisting for kidney transplantation and modification of eGFR thresholds to equalize waitlist time. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 677–685, 2021. 10.1681/ASN.2020081144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou C, Chen Y, He X, Xue D: The value of cystatin C in predicting perioperative and long-term prognosis of renal transplantation. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 82: 1–5, 2022. 10.1080/00365513.2021.1989714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Risch L, Blumberg A, Huber AR: Assessment of renal function in renal transplant patients using cystatin C. A comparison to other renal function markers and estimates. Ren Fail 23: 439–448, 2001. 10.1081/JDI-100104727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White C, Akbari A, Hussain N, Dinh L, Filler G, Lepage N, Knoll GA: Estimating glomerular filtration rate in kidney transplantation: A comparison between serum creatinine and cystatin C-based methods. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3763–3770, 2005. 10.1681/ASN.2005050512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christensson A, Ekberg J, Grubb A, Ekberg H, Lindström V, Lilja H: Serum cystatin C is a more sensitive and more accurate marker of glomerular filtration rate than enzymatic measurements of creatinine in renal transplantation. Nephron, Physiol 94: 19–27, 2003. 10.1159/000071287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maillard N, Mariat C, Bonneau C, Mehdi M, Thibaudin L, Laporte S, Alamartine E, Chamson A, Berthoux F: Cystatin C-based equations in renal transplantation: Moving toward a better glomerular filtration rate prediction? Transplantation 85: 1855–1858, 2008. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181744225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]