Abstract

Background:

After a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders, people living with dementia (PWD) and caregivers wonder what disease trajectory to expect and how to plan for functional and cognitive decline. This qualitative study aimed to identify patient and caregiver experiences receiving anticipatory guidance about dementia from a specialty dementia clinic.

Objective:

To examine PWD and caregiver perspectives on receiving anticipatory guidance from a specialty dementia clinic.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with PWD, and active and bereaved family caregivers, recruited from a specialty dementia clinic. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and systematically summarized. Thematic analysis identified anticipatory guidance received from clinical or non-clinical sources and areas where respondents wanted additional guidance.

Results:

Of 40 participants, 9 were PWD, 16 were active caregivers, and 15 were bereaved caregivers. PWD had a mean age of 75 and were primarily male (n=6/9); caregivers had a mean age of 67 and were primarily female (n=21/31). Participants felt they received incomplete or “hesitant” guidance on prognosis and expected disease course via their clinicians and filled the gap with information they found via the internet, books, and support groups. They appreciated guidance on behavioral, safety, and communication issues from clinicians, but found more timely and advance guidance from other non-clinical sources. Guidance on legal and financial planning was primarily identified through non-clinical sources.

Conclusions:

PWD and caregivers want more information about expected disease course, prognosis, and help planning after diagnosis. Clinicians have an opportunity to improve anticipatory guidance communication and subsequent care provision.

MESH Search terms: dementia, prognosis, communication, patients, caregiver

INTRODUCTION

Anticipatory guidance is defined as proactive counseling on what to expect in the trajectory of disease, prognosis, and how to plan for the future. It is recognized as an important component of clinician communication in oncology [1] and other medical specialties [2-4]. It is perhaps most commonly used in pediatrics to provide proactive counseling on physical, emotional, psychological, and developmental changes expected to occur in the interval between visits [5]. Anticipatory guidance is thought to reduce uncertainty, decrease distress, and facilitate adjustment to illness [1].

Anticipatory guidance is critical for persons living with dementia (PWD) and their caregivers. It is distinct from diagnostic disclosure in that it is a process of continued explanation and guidance on what to expect in the course of illness, the prognosis, and how to plan for the future. This understanding is necessary to prioritize values and goals for care in the future, known as advance care planning (ACP) [6]. ACP is important in dementia because progressive cognitive and functional disability often requires proxies to make decisions on behalf of the PWD [7].

Research on PWD and caregiver needs [8] is limited regarding information and communication needs, specifically for anticipatory guidance and prognostic disclosure. Prior research on communication in dementia has focused on diagnostic disclosure, which focuses primarily on the first time PWD and/or caregivers are told about the diagnosis of dementia [9-10]. Prognostication research has focused largely on advanced dementia [11]. However, PWD and their caregivers have to manage a long disease course between diagnosis and death, and it is unclear what guidance they receive in this interval period. Prior needs assessments for case management have shown PWD and caregivers are interested in receiving education and counseling, information about relevant services, legal assistance, financial support and planning, advance care planning, care coordination, development of care plans, and a well-defined care pathway [8]. PWD and caregivers have shown interest in learning more about prognosis and planning for the future [9], and more work is needed to understand the experiences of PWD and caregivers with anticipatory guidance after disclosure of a diagnosis.

This study examines PWD and caregiver perspectives on receiving anticipatory guidance from a specialty dementia clinic, other clinical sources, and non-clinical sources. Participants also identified areas where additional guidance was desired, and where additional information was received. This data was collected as part of a broader mixed methods study to understand lived experiences and unmet needs of caregivers and people with dementia and design better clinical supports.

METHODS

Design:

We conducted a descriptive qualitative study [12] with people living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), active caregivers, and bereaved family caregivers recruited from a specialty dementia clinic at a large academic medical center on the west coast. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and comports with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) [13].

Participants:

In order to capture a full range of disease severity and diversity of dementia types, we purposively sampled individuals with at least one visit at a dementia specialty clinic with personal or caregiving experience with one of six types of dementia syndromes: Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), corticobasal syndrome (CBS), dementia with Lewy body disease (LBD), behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), primary progressive aphasia (PPA), or progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Potentially eligible participants were identified via chart review. We aimed to capture both patient and caregiver perspectives at different disease stages; prospective and retrospective experiences of mild/moderate stages, and retrospective experience of severe/advanced disease and bereavement. Therefore eligibility criteria included being a) a patient living with mild to moderate dementia (e.g. Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) [14] or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [15] >15 in the prior year); b) an active caregiver of a community-dwelling PWD with MMSE or MoCA >15; or c) a bereaved caregiver of a patient who had died with severe or advanced disease >3 months but less than a year prior to recruitment. Participants also had to feel comfortable being interviewed in English.

For all eligible candidates, the study coordinator contacted the associated clinician to confirm the diagnosis and request clinical clearance to approach. Once approved, the study coordinator called the candidate up to three times, leaving voice mails. The study coordinator approached 75 individuals; 40 were ultimately interviewed. Reasons for non-participation included inability to reach the candidate; candidate screening out based on eligibility criteria; and candidate refusal for reasons such as lack of interest and lack of time.

Setting:

The dementia specialty clinic provides interdisciplinary evaluation and management for persons living with cognitive impairment and dementia. Patients are referred for diagnostic evaluation and for ongoing care. The interdisciplinary team typically consists of a behavioral neurologist and neuropsychologist, and if needed, a social worker, advanced practice nurse, and/or genetic counselor for additional evaluation and support. Patients may not interact with all team members depending on staffing, patient preferences, syndrome, needs, and involvement in research. Patients are seen as needed with typical follow-up in-person or by phone every three months to a year. Education and community resources are included in an after-visit summary that is provided to the patient and caregiver as a printed report or made accessible via a patient online portal.

Data Collection:

Interviews were conducted between November 2018 – September 2019 by a PhD sociologist (SBG). Interviews were conducted in-person for PWD to complete teach-to-goal informed consent; interviews with caregivers were conducted in-person or via telephone depending on distance and participant preference. 31 caregivers and 9 PWD were interviewed; 6 interviews reflect 3 caregiver-PWD dyads where each person was interviewed separately. Participants were provided a $30 gift card for their time.

Semi-structured interviews included questions on knowledge of prognosis and expectations of the future, caregiver experiences, and experience receiving anticipatory guidance. Participants self-reported demographic characteristics; race/ethnicity categories aligned with NIH reporting definitions. No data was collected regarding degree of engagement with the clinic (e.g. # of visits or variety of disciplinary contacts). Caregiver interviews lasted 59 – 128 minutes (mean = 83), and PWD interviews lasted 39 – 77 minutes (mean = 56). With respondent permission we digitally recorded all interviews and had them professionally transcribed, then removed personally identifying information. Field notes were taken during the interviews and included among study data.

Data analysis:

We used a template analysis approach [16] that included deductive and inductive coding to identify themes around anticipatory guidance. Multiple authors read the dataset in its entirety (AS, SBG, KLH). First author (AS) created deductive codes to label experiences around anticipatory guidance after diagnosis: participants reporting what they had been told, not been told, or hoped to hear. Then authors iteratively developed and refined codes to label inductively-identified themes within the deductively coded categories, such as uncertainty, prognosis, or issues with behavior. Two authors (AS, KH) iteratively reviewed and double coded 5 transcripts with both inductive and deductive codes, refining until consensus around definitions and applications had been met. Coding and analysis did not compare patterns by dementia subtype. The first author applied the refined codebook to all transcripts, and drafted figures summarizing findings and tables with multiple quotes exemplifying subthemes. All authors reviewed tables of data organized by codes, adjudicated questions, and helped refine themes and subthemes.

RESULTS:

There were 31 caregiver participants, 16 were active caregivers, and 15 were bereaved. Caregivers had a mean age 67 years (range 40-87) (Table 1). The majority (68%) identified as female, 74% were white, 80% college degree or higher, and the modal income category was $100k+. There were 9 PWD participants, with a mean age 75 years (range 67-86). The majority identified as male (67%), and the majority were white (78%) with a college degree or higher (89%). The modal income category for PWD was also $100k+. The majority of the interviews were unrelated PWD and caregivers; 3 were PWD-caregiver dyads. Quotes from participants are identified by a code denoting participant type and participant number, e.g., BC26 refers to the 26th participant who was a “bereaved caregiver”; AC refers to “active caregiver” and P to “PWD”.

Table 1. Demographics of participants.

1. Caregiver data is the dementia type of the person they were taking care of. 2. Other or mixed syndromes includes: 1 corticobasal syndrome (CBS), 1 logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA), 3 AD/LBD (Alzheimer’s Disease/Lewy Body Disease), 1 AD/PCA (posterior cortical atrophy), 3 AD/VD (vascular disease), 1 CBS/PCA, 1 lvPPA/AD, 1 nfvPPA/PSP (nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia/progressive supranuclear palsy).

| Caregivers n=31 | Patients n=9 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age in years (Mean [range]) | 67.3 | 40-87 | 75.3 | 67-86 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 21 | 68% | 3 | 33% |

| Male | 10 | 32% | 6 | 67% |

| Type of Dementia1 | ||||

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 14 | 45% | 5 | 66% |

| Lewy Body Dementia | 3 | 10% | 0 | 0% |

| Frontotemporal | 2 | 6% | 1 | 11% |

| Progressive Supranuclear Palsy | 2 | 6% | 0 | 0% |

| Other or mixed syndromes2 | 10 | 35% | 3 | 33% |

| Martial Status | ||||

| Married/partnered | 15 | 48% | 6 | 67% |

| Widowed | 11 | 35% | 0 | 0% |

| Divorced/separated | 2 | 6% | 2 | 22% |

| Never married | 3 | 10% | 1 | 11% |

| Latinx/Hispanic | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| No | 30 | 97% | 9 | 100% |

| Missing | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0% |

| Race (multiple possible) | ||||

| White | 23 | 74% | 7 | 78% |

| Black/African American | 3 | 10% | 0 | 0% |

| Asian | 3 | 10% | 1 | 11% |

| Other [text available] | 2 | 6% | 0 | 0% |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | 1 | 11% |

| Education (highest completed) | ||||

| High school graduate | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0% |

| Some college/no degree | 2 | 6% | 1 | 11% |

| Assoc. deg/trade/vocational school | 3 | 10% | 0 | 0% |

| College graduate | 10 | 32% | 1 | 11% |

| Masters/PhD/Professional degree | 15 | 48% | 7 | 78% |

| Has health insurance | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 100% | 9 | 100% |

| Income category (total household) | ||||

| <$20,000-<$40,000 | 3 | 10% | 1 | 11% |

| $40,000-<$80,000 | 7 | 23% | 3 | 33% |

| $80,000-$100,000+ | 18 | 58% | 5 | 56% |

| Missing | 3 | 10% | 0 | 0% |

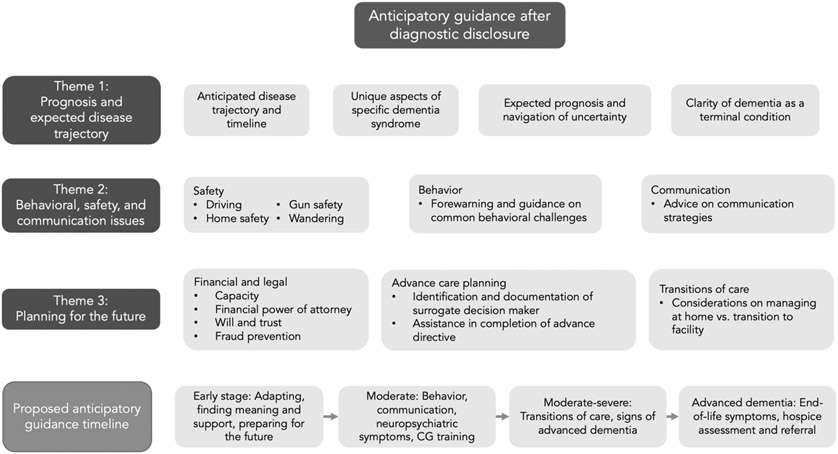

We identified three main themes participants reported related to anticipatory guidance: (1) prognosis and expected disease trajectory; (2) behavioral, safety, and communication issues; and (3) planning for the future. A fourth and overarching theme, uncertainty, was identified within the other three themes. Throughout we refer to participants without quantifying them; this does not imply themes were raised by all participants.

Guidance on prognosis and expected disease trajectory (table 2)

Table 2. Theme 1: Guidance on prognosis and expected disease trajectory.

AD = Alzheimer’s Disease, CBS = corticobasal syndrome, LBD = Dementia with lewy body, bvFTD = behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, VD = vascular dementia, nfvPPA = nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia, PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy

| Subtheme | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|

| Participants had mixed experiences learning about prognosis and expected disease trajectory from their providers, and noted hesitancy to provide details due to uncertainty | AC27 (AD): “And, of course, the doctors, at least our doctor, was reticent to say, this is how much time you have or how much time you have for [[Wife]] to be functional. And here's when she’ll start to not be functional. And I get why they’re like that but that is sort of what you're trying to figure out and plan for, not that any of us can. But, you know, doctors like to be circuitous and just kind of, ‘Oh, everybody is different. You never know.’ They don't want to give you too much information about it, I guess, because they don't really know.” |

| AC22 (CBS): “They said he's going to lose the ability to speak. He's going to lose-- they went through the list of everything that was going to happen that they knew, but it was no "For sure these things are going to happen." At the time they told us in the United States about 5,000 people they had diagnosed with this disease and a lot of times that it was misdiagnosed, so there wasn't a lot of information on it, but these were some of the things that we could expect to happen.” | |

| Non-clinical sources such as books and the internet, filled a gap in information about prognosis and disease trajectory | Interviewer: Do you feel like you’ve received helpful guidance regarding what to expect in thinking of the future, how things may change in the future? AC12 (AD): “The neurologist has not dealt with that. I mean, it’s a recent diagnosis, maybe that’s reasonable, I don’t know. Where I’d gotten it is from the support group, and from the two women whose husband died of Lewy body disease. I have a book called “The Savvy Caretaker,” that I guess there’s a course out offered by the Alzheimer’s Association in Lafayette, and so this friend gave me that book that goes through the stages. I wonder if that’s the only thing I have. No doctor has provided information about stages at all. So my information is from “The Savvy Caretaker” or online. I mean, I just research Alzheimer’s.” |

| Interviewer: “Do you remember early on whether you received from your local neurologist or at the [[memory clinic]] anything regarding, ‘Here’s a likely time span,’ or, ‘Here’s how the disease may progress’? BC21 (AD/LBD): I’m sure I asked that, and I can’t say definitively whether, importantly, [neurologist] provided a response. More than likely he did, but he was also very hands-off as it relates to timing. The best thing that I had for guidance was the Alzheimer’s website, which described the disease by stage, and there’s about a half a dozen different stages that they describe with the symptoms associated with each of those stages, and that gave, for me, that was the best, although things don’t always match up, but generally they did, and so I had an awareness that, you know, 8 to 10 years would probably be about right" | |

| Participants wished providers would share more information about prognosis and where they were along the disease trajectory, acknowledging there is uncertainty. | AC29 (bvFTD): “I guess what I would really like to know is ‘What's going to happen next? What's the next thing that's going to happen?’ I mean, how is this man going to-- I mean, what's going to happen with this type of dementia? What's the next thing that happens? I mean, does he just quit eating? Does he just quit breathing? What can I do to prolong and help his life?” |

| Interviewer: Also, thinking about your interactions with the memory and aging center, what did you learn from them, if anything, about how things might change or what you might be able to expect in the future? AC25 (AD/VD): We haven't gotten there. And I haven't asked. Our visits have always been together. I feel kind of reluctant about asking about the future for fear that the self-fulfilling prophecy may make things worse than they would otherwise be. I don't think anybody has said that it’s going to improve. INT:So I know you just said you've been there together and you’re reluctant to ask outright. How important or interesting is it to you to get information about what might be becoming? AC25: You know, from the support groups, the conversations that I've heard people say is you really can't predict. Everybody is different. Don't believe what they tell you is happening next. because it's all individually unique. So I think that probably my kids would like to know what might be happening but I really don't believe that anyone can. Having been through a decline of my father that was quite different than the decline of our friend, it would be helpful to me from a standpoint of my own planning but I just don't give it much credence. If I thought they could tell me what was happening I’d ask them and plan on it. " “INT: What more would you want to know? What other information would you like? P10 (nfvPPA/PSP): Gradually it’s going to progress, what I’m facing. INT:So you’re indicating you want more information about what that will look like as it progresses? Is that accurate? P10:Yeah, and the people that I met reluctantly described the progression and hesitantly.” |

Participants reported mixed experiences learning about prognosis and expected disease trajectory from their clinicians and noted clinician hesitancy in providing details. Some participants, especially those impacted by less common but more clinically distinct syndromes, such as PPA, received specific information about disease course. One active caregiver stated, “they told us in the United States about 5,000 people they had diagnosed with this disease … so there wasn't a lot of information on it, but these were some of the things that we could expect to happen” (AC22, CBS). Some participants recalled hearing about expected disease progression, such as swallowing difficulty, only after it happened, and said that the clinicians “didn’t look forward too much” (BC26, AD/posterior cortical atrophy). One PWD said he could tell the clinicians were “hesitant” and expressed wanting to know about how long he would have before developing swallowing difficulty (P10, PPA/PSP). Participants perceived clinician’s uncertainty, stating, “You know what I needed – and nobody could provide – was someone to tell me how this was going to go, and no one can do that. So it’s that cloud of unknowing” (BC05, CBS/PCA). One caregiver noted wanting an opportunity to speak with their clinician about prognosis or trajectory without the PWD present (AC10, LBD).

Participants wished clinicians would share more information about prognosis and where they were along the disease trajectory. Caregivers hoped both for more guidance in advance on “more about how this would proceed…There was a learning curve for me, and I don’t ever want to learn it again” (BC05, CBS/PCA). One caregiver wanted both a “general prediction of what I’m going to be facing in the future” and “what does this disease look like when it’s bad?” in addition to where their loved one was in their trajectory (AC10, LBD). One caregiver wanted close follow up after diagnosis to ask questions, noting that at diagnosis “you're in such shock. It's not like they're going to do a lot of download” (AC27, AD).

Participants often alluded to an inherent uncertainty in discussions about prognosis and planning for the future, noting they could tell clinicians were reticent to commit to a certain timeline and they understood it was difficult to predict. One caregiver said, “nobody’s able to tell me, and maybe they can’t”, noting “if you had a diagnosis of cancer or something, they would say, ‘Well, you’ve got six months,’ or, ‘You’ve got six years,’ or something. But this you don’t know, and that’s the very <sighs> frustrating part" (AC10, LBD). One caregiver stated that, based on their personal experience of seeing different declines in dementia, a prognosis “would be helpful from a standpoint of my own planning but I just don’t give it much credence. If I thought they could tell me what was happening I’d ask them and plan on it” (AC25, AD/vascular dementia).

Participants described seeking information from non-clinical sources, such as books and the internet, to fill their perceived gap in information about prognosis and disease trajectory. Participants sometimes noted the source of this information but rarely attributed it to the dementia specialty clinic. One caregiver noted that the neurologist was “hands-off as it relates to timing” of the disease and prognosis, but they found good guidance via the “Alzheimer’s website” and found the description of stages and related symptoms to be useful and accurate to their experience (BC21, AD/LBD). Another caregiver said, “if you look at information online about Alzheimer's, you know, typical lifespan is six years from diagnosis” and that their spouse lived seven years (BC13, AD/LBD). Participants also found guidance from support groups and books, noting that, “even though it's depressing and you're hoping it doesn't happen, you kind of know that it-- this probably will happen” (BC06, LBD). Participants also noted the role in support groups in normalizing and validating difficult experiences. One caregiver noted that “with the group that you found there were people that you weren’t alone, there were people that were far more advanced and others that weren’t” thus seeing the spectrum of disease (BC12, AD).

Guidance on behavioral, safety, and communication issues (table 3)

Table 3. Theme 2: Guidance on behavioral, safety, and communication issues.

lvPPA = logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia, AD = Alzheimer’s Disease, VD = vascular dementia

| Subtheme | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|

| Guidance from providers was helpful but often received late in the course after symptoms had started | BC15 (lvPPA): “When [[spouse]] started wild combative behavior, I told the nurse, I said, “I don’t know why he’s doing it.” She said, “Oh, it’s normal, they all do that,” and so I felt much better about it. I thought something I was doing wrong or something like that. You need to know-- the word normal, of course, it doesn’t apply in the usual sense here, but you need to know that it is something frequently experienced, even if it’s not normal”. |

| BC17. (AD): “[nurse practitioner] took [patient] and we dealt with behavior. That was very beneficial. I didn't really understand the spatial difficulty until [nurse practitioner] explained it to me, that instead of finding the chair, he's on the edge, and the chair falls off, and the chair tilts over because he's-- he was a good size…what I miss the most really was constant behavioral assistance, and that's where the Alzheimer's support group helped.” | |

| Participants received helpful information from books and support groups that they didn’t find elsewhere | P04 (AD): “I mean, in the group that I've been to I've heard, I've gotten some good information, I've also gotten some scary information. Well, the scariest thing was that I think people with Alzheimer's can sometimes get to the point of physically abusing their partner. So I've told my two children that if I get to that point they need to step in.” |

| BC17 (AD): “But I was really interested in the behavior, and most doctors don’t have time to deal with the behavior. So I did a lot of reading, and then toward the end or mid, I guess, I had an Alzheimer’s group that really helped, and I found this book way too late that everybody should have. ‘Coping with Behavior Change in Dementia’ by Beth Spencer and Laurie White and why they pee all over the floor and just dealing with the day-to-day logistics.” Interviewer: How did you find this book? BC17: I found it through my Alzheimer's group." | |

| Participants noted feeling behind on anticipating behavioral and safety concerns, and wished they had forewarning | BC13 (AD/LBD): “Yeah. But she had gone into Trader Joe’s and apparently had no money with her but was looking to buy bananas or something. You know? And so they walked her back up here, but so at that point I realized I couldn’t just go off and leave her by herself.” Interviewer: “But that was a surprise?” BC13: “Yeah. But it was a surprise. And so, you know, I think I would have appreciated some better or more explicit descriptions of things that are likely to happen in terms of behaviors…I always felt like I was kind of behind the curve on when something new would happen. It was kind of always a surprise, you know, like the wandering or taking off.” |

| BC4 (AD/VD): “I think knowing better how to communicate with people with dementia. I tried to, I think, for too long I tried to be, act as normal as possible. If [husband] would get off track I’d try to get him on track instead of following his track.” |

Caregivers reported a desire for guidance from clinicians about behavioral, safety, and communication issues and appreciated input, though noted they received guidance later in the disease course after more challenging symptoms had started to appear. For example, one caregiver noted her spouse had “started wild combative behavior” and upon mentioning it to the nurse and hearing it was typical, “felt much better about it. I thought something I was doing wrong or something like that” (BC15, PPA). Another caregiver learned from the neurologist that “the alcoholism [of the spouse] was being driven by the dementia… we weren’t dealing with classic alcoholic behavior” (BC31, FTD). Participants appreciated tips for communication, such as “[Doctor]…said ‘Use five words or less when speaking’ so that it's always tracked, what I'm saying” (AC23, AD).

Participants wished they had forewarning from clinicians to anticipate behavioral and safety concerns. A bereaved caregiver stated he was always “behind the curve on when something new would happen. It was kind of always a surprise, you know, like the wandering or taking off” (BC13, AD). Caregivers also hoped for additional strategies on how to best communicate with their loved ones, feeling that “for too long I tried to be, act as normal as possible. If [husband] would get off track I’d try to get him on track instead of following his track” (BC4, AD/VD).

Participants also found guidance on behavioral and safety issues from support groups and books, including challenges to anticipate and plan for in the future. One caregiver noted “most doctors don’t have time to deal with the behavior” (BC17, AD) so they filled the gap with a support group and reading. A PWD also learned from their support group that “people with Alzheimer's can sometimes get to the point of physically abusing their partner. So I've told my two children that if I get to that point they need to step in” (P04, AD). Support groups even provided specific strategies for managing issues, such as “put a color around the toilet seat so they know where to aim” (BC17, AD) to avoid toileting in unintentional places. Many participants said that books were useful guidance throughout the disease course, with one caregiver stating: “I got several books, and I kind of flipped through them-- the one that was really helpful, later on, and-- but never picked it up again, until things got worse” (C6, LBD). Books named by participants are included in the quotes in table 3.

Guidance on planning for the future (table 4)

Table 4. Theme 3: Planning for the future.

AD = Alzheimer’s Disease, PCA = posterior cortical atrophy, lvPPA = logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia.

| Subtheme | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|

| Advance care planning was frequently brought up by providers, though some participants wanted additional help completing the documentation | BC26 (AD/PCA), discussing ACP “They said, ‘Well, have you filled out this thing?’ and, ‘That's a very important thing,’ and stuff like that. .. it kind of slips through the cracks that I wasn't handling it which is kind of a living alone thing in a way because at that point I was living alone in a way. And sometimes things don't communicate, don't get past, ‘Don't you figure out what's going on with him?’ you know. And I was BSing the doctors, I mean I wasn't meaning to but I'd say, ‘Yeah, we'll get that done,’ and then the next time I'd say, ‘I know what you're going to say, I'm going to get it done,’ or, ‘Here, give me a new one, I lost it.’ And it was just something about it, I don't know. BC26, during hospital stay: “someone mentioned something about … the directive and I said, ‘Yeah, we're going to do that.’ And then this nice doctor came over and said, ‘I can come back and help you with that,’ and I said, ‘Great, you do that.’ And so she did and we got it all filed and I almost broke down in tears and just said, ‘Thank you, I can't thank you enough, I didn't know how to do this.’ Anyway it was so nice of her … It was unbelievable, I needed that." |

| Participants reported getting tips on important documentation from support groups rather than providers | Interviewer: “The idea of you needing to update your legal paperwork, for example, is that something that any of your providers have enquired about yours? For example, [memory center neurologist]? AC30 (lvPPA/AD): “No. I'm going to say it's more something we talk about in our Alzheimer's group. It's brought there more. But no. I would say nothing that stands out in my mind right now that [memory center neurologist] or even the general practitioner has brought up necessarily." |

| Interviewer: Was it Dr. [[M]] herself who brought up the idea of doing this paperwork and planning? AC27 (AD): “No. Well, I don't know. No, I think we learned it through the group. Yeah, we learned it through the group that you could go and get-- yeah. We learned it through the group for sure. That group was very helpful because everybody had different solutions and different things that they had gone through where they could be helpful with what you do and what you don't do.” | |

| Participants welcomed more input and guidance from providers on future planning, and note difficulties planning ahead for an uncertain future | AC25 (AD/VD): “I'm kind of a planful person. And I think my concerns are the uncertainty. I don't know when I need to plan on more care or when I need to rearrange the furniture for a wheelchair; maybe I won’t have to. So I’m kind of captive by the uncertainty.” |

| BC14 (AD): “I'm thinking now to wouldn't it be nice for someone to actually have a list and mark it off and go over it with you, you know, to actually say, ‘Have you addressed this? If not, maybe we can send you-- Maybe we have a list of lawyers,’ Or whatever, maybe just someone who does some homework for you so you're not just-- because you're so exhausted at a certain point. I mean, I wasn't sleeping at all. My mother was constantly waking me up. I was-- So my point is I guess you need to have extra strength, an extra set of-- an extra mind even to help you because if you're sleep deprived, you know, someone to say, hey, you know. It's kind of an assistant in a way, you know. " | |

| Participants felt they needed additional guidance in advance of considering transitions of care, such as to care facilities | BC16 (AD/LBD): “I think the only thing that I could imagine being better is if there was some sort of a liaison team that helped people like myself who were needing to put their loved ones in a care facility, if there was some additional assistance that could be given, I think. And what would that additional assistance be? For lack of a better way of saying it, I think it's a bit more handholding. And I don't even know if that's even a reasonable thing to expect, but it does feel like you're floating out there sometimes. And you've been given some guidance, but you need more. I almost wonder if an additional person that's in your profile that is, again, one of these people who helps with these transitions. Again, I don't – I can't identify exactly what that would be, but I just remember how alone I felt during the period of time where [[Spouse]] was needing to – something had to change at home. It was definitely leading up to a care facility.” |

| AC02 (AD): “Preparing for end of life. Say location of care. And this is, you know, sometimes, you know, it comes to my mind. If it comes to a time that, you know, it's so difficult to care, you know, by one person, by me or by caretaker, and then should I keep him home or should I, you know, send him to the what do you call it, institution, you know, for this type of special patient care. And then I personally, my own feeling is I'd like to keep him home. And then but to keep him home, you know, how worse, you know, he could-- how difficult, you know, that would be that I don't know. So often that comes to my mind, how could I prepare, you know, for the worst.” |

Clinicians frequently brought up advance care planning (ACP). One caregiver recalled “[Doctor] recommended that we have these conversations and get everything in order now, better now than later, so that we didn't run into any hurdles later in life” (C22, CBS). However, some participants wanted help completing documentation of surrogate decision-makers and care preferences, and recalled difficulty completing an advance directive and other ACP documentation without clinician assistance.

Participants reported getting tips on important legal and financial documentation from support groups rather than clinicians. Caregivers specifically recalled learning about key documentation to complete via their groups rather than their clinicians, as one caregiver recalled “I’m going to say it’s more something we talk about in our Alzheimer’s group. It’s brought there more. But no. I would say nothing that stands out in my mind right now that [dementia center neurologist] or even the general practitioner has brought up necessarily” (AC30, PPA/AD).

Participants welcomed more input and guidance from clinicians on future planning and noted the difficulty of planning ahead for an uncertain future. One caregiver noted “legal support, information, financial planning are also important. And sometimes it's too late for some of those things once you're really down the road” (AC01, AD). One PWD who lived alone also felt he needed advice on what legal and financial planning to complete ahead of time, wanting “instructions on how I should protect myself in life. Should I not live alone and things like that” (P11, bvFTD). Participants simultaneously wanted advice but knew there was a degree of uncertainty, with one active caregiver noting, “I don't know when I need to plan on more care or when I need to rearrange the furniture for a wheelchair; maybe I won’t have to. So, I’m kind of captive by the uncertainty” (AC25, AD/VD).

Participants felt they needed additional guidance on how to think ahead about timing and source of caregiving help as the disease progressed, and sometimes received this via support groups and community organizations. There was a desire for more guidance in determining when more help was needed at home, whether it was feasible to try to keep taking care of their loved ones at home, and how to find and choose paid help if necessary. One caregiver questioned whether she was doing the right thing trying to keep her loved one home: “I mean, I have to just ask, ‘Do you think I'm providing the level of care that she needs?’ You know, because …my sister's saying, ‘[[Spouse]] should be in a facility.’ You know, and, it's like, I don't think so, you know. But am I deluding myself? I mean, it's a weekly question. It depends on the next level of decline. It's a crazy path. Maybe it's clearer for some people. I don't know.” (C09, LBD). One caregiver found advice to look at dementia care facilities in advance helpful since, “they said when that point arrives I'll probably be very overwhelmed and stressed out, and so the best thing would be to have investigated in what memory care facilities offer, what ones don't I like” (AC12, AD). Another caregiver noted wanting more assistance for a transition in care to a facility, saying “what would that additional assistance be? For lack of a better way of saying it, I think it’s a bit more handholding. And I don’t even know if that’s even a reasonable thing to expect, but it does feel like you’re floating out there sometimes. And you’ve been given some guidance, but you need more” (BC16, AD/LBD).

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study provides an enriched perspective on the experiences of PWD and their caregivers with anticipatory guidance after a dementia diagnosis, especially with respect to disease trajectory and prognosis. PWD and caregivers felt they received incomplete or “hesitant” guidance on prognosis and expected disease course via their clinicians and filled the gap with information they found via the internet, books, and support groups. They appreciated guidance on behavioral, safety, and communication issues from clinicians, but noted it often occurred after challenges had already appeared and found more timely or advance guidance from other non-clinical sources. When planning for the future, they were asked about advance care planning documentation by clinicians but did not always receive help completing it. Participants found information about legal and financial planning through support groups, and hoped for more guidance to determine if it was feasible to stay at home versus transitioning to a long-term care facility.

Participants in this study expressed interest and desire in obtaining more information from their clinicians about disease trajectory, prognosis, and behavioral and safety issues in advance of facing these issues, despite receiving care at a specialty dementia clinic. Participants often alluded to an inherent uncertainty in discussions about prognosis and planning for the future, noting they could tell clinicians were reticent to commit to a certain timeline and they understood it was difficult to predict. However, they valued even general timelines regarding stages and duration of illness that they found through other sources such as the internet or books. Systematic reviews regarding practices in disclosing dementia diagnoses show PWD and caregivers want to know more about the future and prognosis [9], and after diagnosis feel uncertain of the prognosis, disease progression, and management options [17]. Though one would hope that this uncertainty improves with subsequent clinician visits, this study demonstrates that in routine care after diagnostic disclosure, PWD and their caregivers want and need further information on disease trajectory and prognosis to aid planning. A recent survey on dementia prognostic awareness found that only 30% of caregivers reported their physician discussing life expectancy/prognosis, 43% did not know the estimated life expectancy/prognosis in years, and only 42% knew it was a terminal condition [18].

There are many possible reasons PWD and caregivers reported receiving inadequate anticipatory guidance. Clinicians often have difficulty accurately prognosticating, especially in the earlier stages of the disease; much of the prognostication literature is focused on advanced dementia [11]. The heterogeneity of the disease spectrum makes it difficult to predict what the trajectory will be like for an individual patient, and comorbid conditions and co-pathologies (e.g. vascular + Alzheimer dementia) can further complicate prognostication. More frequent and longitudinal follow up may assist clinicians in better understanding the symptoms and trajectory of the syndrome, and hence become better at providing anticipatory guidance that is specific to each patient. Clinicians also have to feel comfortable and adequately trained in serious illness communication, including communication about uncertainty, as the way information is communicated can often influence how information is received. [19] Availability and appropriate engagement of an interdisciplinary team, including clinical nurse specialists [20], advance practice nurses, and social workers may improve guidance, as has been the case in dementia care management programs [21].

In a complementary study, many clinicians at the dementia clinic from which participants of this study were recruited stressed the importance of providing and explaining diagnosis, in addition to addressing behavioral concerns and caregiver support [22]. They also identified challenges due to lack of time to have appropriate conversations, as well as in how to initiate and frame conversations about prognosis and disease progression [22]. The contrast between what the clinicians report and what PWD and caregivers reported in this study is not surprising. Even when clinicians feel they communicated clearly, patients and caregivers can often have a different perception of what was said, or not feel ready to hear the news [23].

Our findings suggest that even if prognosis and disease trajectory information is shared, it may not be communicated in a manner that allows PWD and caregivers to understand and recall this information. Participants in our study expressed wanting to plan for the future and thought that understanding prognosis and likely timelines for cognitive and physical disability would assist in making arrangements. Not knowing prognosis is one barrier to effective ACP, which is critical to naming a surrogate decision maker and defining goals and values prior to losing capacity to make decisions [6]. Prior research indicates understanding the terminal nature of dementia correlates with a higher likelihood of appropriate symptom management at the end of life [24]. A qualitative study of people living with Parkinson disease and their care partners showed interest in a “roadmap” as a guide for decision making and planning [2,25].

PWD’s and caregivers’ perception of insufficient guidance and desire for more information offers an opportunity to provide systematic structured anticipatory guidance for PWD and CG. We provide an initial framework for anticipatory guidance that incorporates palliative care communication principles as well as the information received and wanted by participants in this study (figure 1). A broad overview of the disease trajectory and prognosis, and explicitly stating that dementia is a terminal disease, is important to future planning and advance care planning. To the extent the disease trajectory and unique features of the dementia subtype are known (i.e. hallucinations with LBD, worsening aphasia with PPA), clinicians should offer to share this with the PWD and CG. More detailed information may be shared in a step-wise approach between interval follow up visits, focusing on safety concerns (wandering, driving, financial fraud) in the early stages, and behavioral issues and other neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in the moderate stages. Guidance should be provided for how to plan for progressive functional impairment (home modifications, additional caregiving) as dementia progresses, and symptoms and management of end-stage dementia.

Figure 1. Proposed model of anticipatory guidance for dementia.

Suggested anticipatory guidance topics per themes raised by participants, and proposed anticipatory guidance timeline. Diagram represents intersection of study findings and clinical expertise. Certain topics (safety, financial and legal, and advance care planning) are time-sensitive after diagnosis. Each PWD and their caregiver may have different needs depending on stage of diagnosis and individual knowledge.

Offering close follow-up after diagnostic disclosure allows patients and caregivers to recover from the initial shock [9], and ideally an opportunity for caregivers to have separate conversations with clinicians to ask questions they may not feel comfortable asking in front of the PWD. Assistance with identifying important legal and financial paperwork and referrals to assistance completing it while the PWD has capacity is important as PWD and their caregivers may not get this information elsewhere. Timely completion of legal and financial documentation is important before the PWD loses capacity to make these decisions and sign paperwork [26-27]. ACP was underutilized in the specialty dementia clinic that provided care to participants in this study [28]. Though there are many barriers to completion of ACP, opportunities for discussion and completion with the clinical team may help PWD and their caregivers reflect on and document care preferences [29-30]. Support groups also play a key role in providing information as seen in this study and others [31-32]. Evidence-based dementia care programs such as Care Ecosystem [33] can provide a platform for ongoing conversations and anticipatory guidance, in addition to specialty center visits.

Palliative care focuses on symptom management, assessment and support of caregiver needs, and coordination of care for people living with serious illness [34]. There is an international effort to define optimal palliative care in dementia, with consensus that person-centered care, communication, and shared decision-making is one of the most important domains [35]. Given the shortage of palliative care specialists, integrating primary palliative care – palliative care provided by clinicians who are not palliative care specialists – into dementia practices will be of utmost importance [22].

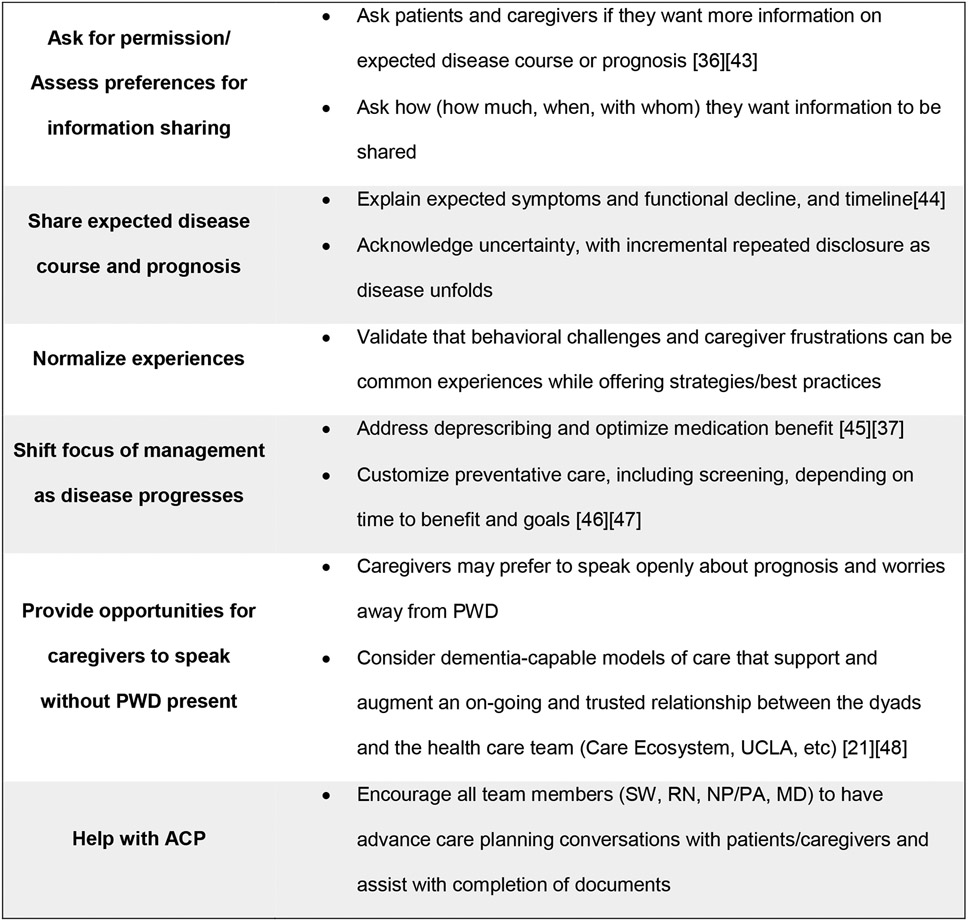

Palliative care communication frameworks can be adapted to help provide systematic anticipatory guidance and prognostic disclosure to PWD and their caregivers (figure 2). Asking for permission [36] before sharing information on prognosis allows the PWD and their caregiver to decline if they do not want information and alleviates the clinician of concerns that the information is not wanted. Validating and normalizing difficult experiences and uncertainty can also be important tools in communication. As dementia progresses, it is important to reevaluate the risks versus benefits of medications and preventative care, and ensure they still meet the goals of the person living with dementia [37]. These strategies should be utilized and shared across the interdisciplinary team. For practices with primarily or only behavioral neurologists, they may consider doing all these tasks or referring to case management if available for additional support. Dementia specialty clinics with interdisciplinary team might share responsibilities; clinical nurse specialists [20] and social workers can play an especially critical role in educating and supporting PWD and their caregivers.

Figure 2. Adapting palliative care communication to anticipatory guidance for dementia.

Adapted palliative care communication principles as applied to anticipatory guidance in dementia. This table is informed by PWD and caregiver experiences in this study though primarily based on clinical expertise. References for additional resources included when available. Additional guidance is available from the Center for Advancement of Palliative Care. [44]

Many challenges exist in providing appropriate anticipatory guidance to PWD and their caregivers, including time limitations, difficulty obtaining reimbursement, and the regular absence of a full interdisciplinary team in all dementia care settings. There is a need for alternative reimbursement models that would value time spent counseling on what to expect as much as diagnosis. For example, some CPT codes can be used to provide comprehensive care planning [38], and legislation is being proposed for a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation demonstration project to reimburse dementia care management programs [39].

Limitations

Limitations to this study include that it was a single site with a primarily white and high-income population that may not be representative of other memory specialty centers. Given existing racial/ethnic differences in prevalence of dementia [40], disparities in dementia treatment [41], and awareness of diagnosis [42], it is plausible there are disparities in access to memory specialty centers and anticipatory guidance that should be investigated in the future. Participants were also community-dwelling and the views of PWD in long term care facilitates are underrepresented; however, bereaved caregiver participants often had experience with long term care facilities. We only recruited English-speaking participants and did not collect data on degree of engagement (e.g. number of visits, number of disciplines involved) with the dementia specialty clinic due to limitations of the study personal. There may be different needs and preferences in more diverse populations, or in primary care settings. Participants recollections, especially bereaved caregivers, may be impacted by recall bias regarding clinical experiences from early in the disease course. Future research could evaluate experiences with anticipatory guidance in other settings (such as primary care), and if enrollment in dementia care management programs provides more knowledge and confidence in anticipated disease trajectory and prognosis.

Conclusion

Patients and caregivers that received a diagnosis of dementia at a specialty memory center recalled being asked about advance care planning, but stated they often found information about prognosis, stages of the disease, behavioral management, and legal and financial planning lacking, and many sought this information through other sources. PWD and their caregivers expressed interest and desire in obtaining more information about disease trajectory, prognosis, and behavioral and safety issues in advance of facing these issues, noting that they often received information after the fact or while new challenges were occurring. Standardizing anticipatory guidance after diagnosis within a palliative care communication framework may help improve patient and caregiver understanding of expected disease course and prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We appreciate the time and expertise of our study participants who contributed data.

Global Brain Health Institute dementia palliative care team members who participated in team meetings where preliminary analysis was conducted yet did not meet criteria for authorship included Talita Rosa, Brenda Perez-Cerpa, Shamiel McFarlane, Maritza Pintado Caipa, and Tala Al-Rousan. Nicole Boyd, study coordinator, helped study administration and participant recruitment.

This study was funded by the Global Brain Health Institute, NIA K01AG059831, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH KL2TR001870 (Harrison).

Author funding:

Eric Widera – Archstone Foundation

Sarah B. Garrett - AHRQ T32HS022241

Christine Ritchie —Funded by NIH, the John A Hartford Foundation, Centene Foundation, Johns Hopkins University/Humana, Inc.

Alissa Bernstein - National Institute on Aging (K01AG059840)

Krista Lyn Harrison - National Institute of Aging (K01AG059831), Career Development Award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (KL2TR001870); UCSF Hellman Fellows Award; National Palliative Care Research Center Junior Faculty Award; Atlantic Fellowship of the Global Brain Health Institute

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to report

References

- [1].Thompson AL, Young-Saleme TK (2015) Anticipatory Guidance and Psychoeducation as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 Suppl 5, S684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jordan SR, Kluger B, Ayele R, Brungardt A, Hall A, Jones J, Katz M, Miyasaki JM, Lum HD (2020) Optimizing future planning in Parkinson disease: suggestions for a comprehensive roadmap from patients and care partners. Ann Palliat Med 9, S63–S74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kutner JS, Steiner JF, Corbett KK, Jahnigen DW, Barton PL (1999) Information needs in terminal illness. Soc Sci Med 48, 1341–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Owusuaa C, van Beelen I, van der Heide A, van der Rijt CCD (2021) Physicians’ views on the usefulness and feasibility of identifying and disclosing patients’ last phase of life: a focus group study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Weber-Gasparoni K (2019) 14 - Examination, Diagnosis, and Treatment Planning of the Infant and Toddler. In Pediatric Dentistry (Sixth Edition), Nowak AJ, Christensen JR, Mabry TR, Townsend JA, Wells MH, eds. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp. 200–215.e1. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fried TR, Cohen AB, Harris JE, Moreines L (2021) Cognitively Impaired Older Persons’ and Caregivers’ Perspectives on Dementia-Specific Advance Care Planning. J Am Geriatr Soc 69, 932–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals - Harrison Dening Karen, Sampson Elizabeth L, De Vries Kay, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Khanassov V, Vedel I (2016) Family Physician-Case Manager Collaboration and Needs of Patients With Dementia and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Ann Fam Med 14, 166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yates J, Stanyon M, Samra R, Clare L (2021) Challenges in disclosing and receiving a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review of practice from the perspectives of people with dementia, carers, and healthcare professionals. Int Psychogeriatr 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Derksen E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Scheltens P, Olde-Rikkert M (2006) A model for disclosure of the diagnosis of dementia. Dementia 5, 462–468. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Davis RB, Shaffer ML (2010) The advanced dementia prognostic tool: a risk score to estimate survival in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage 40, 639–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rendle KA, Abramson CM, Garrett SB, Halley MC, Dohan D (2019) Beyond exploratory: a tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research. BMJ Open 9, e030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiartr Res 12(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H (2005) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53, 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N (2015) The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research. Qual Res Psychol 12, 202–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kunneman M, Pel-Littel R, Bouwman FH, Gillissen F, Schoonenboom NSM, Claus JJ, van der Flier WM, Smets EMA (2017) Patients’ and caregivers’ views on conversations and shared decision making in diagnostic testing for Alzheimer’s disease: The ABIDE project. Alzheimers Dement N Y N 3, 314–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gabbard J, Johnson D, Russell G, Spencer S, Williamson JD, McLouth LE, Ferris KG, Sink K, Brenes G, Yang M (2020) Prognostic Awareness, Disease and Palliative Understanding Among Caregivers of Patients With Dementia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 37, 683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Paladino J, Koritsanszky L, Nisotel L, Neville BA, Miller K, Sanders J, Benjamin E, Fromme E, Block S, Bernacki R (2020) Patient and clinician experience of a serious illness conversation guide in oncology: A descriptive analysis. Cancer Med 9, 4550–4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Barton C, Merrilees J, Ketelle R, Wilkins S, Miller B (2014) Implementation of advanced practice nurse clinic for management of behavioral symptoms in dementia: a dyadic intervention (innovative practice). Dement Lond Engl 13, 686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Possin KL, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, Bonasera SJ, Chiong W, Lee K, Hooper SM, Allen IE, Braley T, Bernstein A, Rosa TD, Harrison K, Begert-Hellings H, Kornak J, Kahn JG, Naasan G, Lanata S, Clark AM, Chodos A, Gearhart R, Ritchie C, Miller BL (2019) Effect of Collaborative Dementia Care via Telephone and Internet on Quality of Life, Caregiver Well-being, and Health Care Use: The Care Ecosystem Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 179, 1658–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bernstein Sideman A, Harrison KL, Garrett SB, Naasan G, Dementia Palliative Care Writing Group, Ritchie CS (2021) Practices, challenges, and opportunities when addressing the palliative care needs of people living with dementia: Specialty memory care provider perspectives. Alzheimers Dement N Y N 7, e12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fried TR, Bradley EH, O’Leary J (2003) Prognosis communication in serious illness: perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc 51, 1398–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].van der Steen JT, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Knol DL, Ribbe MW, Deliens L (2013) Caregivers’ understanding of dementia predicts patients’ comfort at death: a prospective observational study. BMC Med 11, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Scherer LD, Matlock DD, Allen LA, Knoepke CE, McIlvennan CK, Fitzgerald MD, Kini V, Tate CE, Lin G, Lum HD (2021) Patient Roadmaps for Chronic Illness: Introducing a New Approach for Fostering Patient-Centered Care. MDM Policy Pract 6, 23814683211019948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hooper S, Sabatino CP, Sudore RL (2020) Improving Medical-Legal Advance Care Planning. J Pain Symptom Manage 60, 487–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hirschman KB, Kapo JM, Karlawish JHT (2008) Identifying the factors that facilitate or hinder advance planning by persons with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 22, 293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Naasan G, Boyd ND, Harrison KL, Garrett SB, Rosa TD, Pérez-Cerpa B, McFarlane S, Miller BL, Ritchie CS, Group G dementia geriatric palliative care writing (2021) Advance Directive and POLST Documentation in Decedents With Dementia at a Memory Care Center: The Importance of Early Advanced Care Planning. Neurol Clin Pract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cotter VT, Hasan MM, Ahn J, Budhathoki C, Oh E (2019) A Practice Improvement Project to Increase Advance Care Planning in a Dementia Specialty Practice. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 36, 831–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].deLima Thomas J, Sanchez-Reilly S, Bernacki R, O’Neill L, Morrison LJ, Kapo J, Periyakoil VS, Carey EC (2018) Advance Care Planning in Cognitively Impaired Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 66, 1469–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lauritzen J, Pedersen PU, Sørensen EE, Bjerrum MB (2015) The meaningfulness of participating in support groups for informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 13, 373–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chien L-Y, Chu H, Guo J-L, Liao Y-M, Chang L-I, Chen C-H, Chou K-R (2011) Caregiver support groups in patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 26, 1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bernstein A, Harrison KL, Dulaney S, Merrilees J, Bowhay A, Heunis J, Choi J, Feuer JE, Clark AM, Chiong W, Lee K, Braley TL, Bonasera SJ, Ritchie CS, Dohan D, Miller BL, Possin KL (2019) The Role of Care Navigators Working with People with Dementia and Their Caregivers. J Alzheimers Dis JAD 71, 45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th edition. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CMPM, de Boer ME, Hughes JC, Larkin P, Francke AL, Jünger S, Gove D, Firth P, Koopmans RTCM, Volicer L, European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) (2014) White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 28, 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Berkey FJ, Wiedemer JP, Vithalani ND (2018) Delivering Bad or Life-Altering News. Am Fam Physician 98, 99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sawan MJ, Moga DC, Ma MJ, Ng JC, Johnell K, Gnjidic D (2021) The value of deprescribing in older adults with dementia: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 14, 1367–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia, Care Planning. https://alz.org/professionals/health-systems-clinicians/care-planning; Last modified 2021; last accessed July 22, 2021.

- [39].Text - S.1125 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Comprehensive Care for Alzheimer’s Act, Last updated April 14, 2021, Accessed on April 14, 2021.

- [40].Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia, Facts and Figures. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures; Modified 2021; Last accessed December 2, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zuckerman IH, Ryder PT, Simoni-Wastila L, Shaffer T, Sato M, Zhao L, Stuart B (2008) Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of dementia among Medicare beneficiaries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 63, S328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lin P-J, Emerson J, Faul JD, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, Fillit HM, Daly AT, Margaretos N, Freund KM (2020) Racial and Ethnic Differences in Knowledge About One’s Dementia Status. J Am Geriatr Soc 68, 1763–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP (2000) SPIKES—A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer. The Oncologist 5, 302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Communicating About What to Expect as Dementia Progresses. https://www.capc.org/training/best-practices-in-dementia-care-and-caregiver-support/communicating-about-what-to-expect-as-dementia-progresses/, Last modified August 1, 2018, Last accessed December 11, 2021.

- [45].Growdon ME, Gan S, Yaffe K, Steinman MA (2021) Polypharmacy among older adults with dementia compared with those without dementia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 69, 2464–2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kotwal AA, Walter LC (2020) Cancer Screening in Older Adults: Individualized Decision-Making and Communication Strategies. Med Clin North Am 104, 989–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lee SJ, Leipzig RM, Walter LC (2013) Incorporating lag time to benefit into prevention decisions for older adults. JAMA 310, 2609–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tan ZS, Jennings L, Reuben D (2014) Coordinated care management for dementia in a large academic health system. Health Aff Proj Hope 33, 619–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.