Nephrology has seen a revolution over the last decade with the discovery of multiple therapies to slow the progression of CKD and reduce cardiovascular disease burden. In addition to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), there is trial-level evidence for nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, endothelin receptor antagonists, glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists, and, at the head of the pack, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is). This watershed provides tremendous opportunities to turn CKD from an inevitably progressive and lethal disease into one that can be managed proactively, but the lack of implementation has kept this possibility from becoming reality.

The barriers are myriad. First, screening rates for CKD are very low, with receipt of albuminuria testing in only 35% of people with diabetes and 4% of people with hypertension (1). The recommendation for urine albumin-creatinine ratio testing in people with diabetes is well established; however, despite consensus that such testing is indicated for other high-risk populations (2), there is a dearth of guidelines to support it. Even after CKD is diagnosed, prescribing rates for ACEis/ARBs and SGLT2is remain unacceptably low, with only 30%–50% of patients eligible for ACEis/ARBs and only 3%–8% of patients eligible for SGLT2is prescribed treatment (3,4). Rates of prescription to patients from historically marginalized communities are even lower than those in the general population, contributing to existing inequities in kidney care (5). In eligible patients, low prescribing rates may be related to perceived side effects, cost, and access to medicine and clinical inertia. Limited recognition of the clear and impactful benefits of nephroprotective treatments among patients and prescribers impedes their uptake. This problem is particularly relevant to people with nondiabetic CKD, in whom few effective treatment options have been available.

In this issue of CJASN, Vart et al. (6) attempt to address this barrier by providing robust estimates of the real-world benefits (in terms of eventfree life years gained) when patients are appropriately treated with combination nephroprotective medications ACEis/ARBs plus SGLT2is versus no therapy. The authors took advantage of individual-level trial data from three large randomized studies that enrolled people with albuminuric, nondiabetic CKD: Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy (7), the Guangzhou trial (8), and Dapagliflozin in Chronic Kidney Disease (9). The primary composite kidney end point consisted of sustained doubling of serum creatinine, kidney failure, or all-cause mortality, with a secondary end point of sustained creatinine doubling or kidney failure. Assuming independent treatment effects, hazard ratios were estimated for combination therapy versus no treatment using indirect comparison methods. To account for the effect of age on effect size, eventfree survival was estimated for combination versus no therapy on the basis of age of initiation, ranging 50–75 years.

The treatment effects were, perhaps not surprisingly, remarkable. Over 3 years, combination therapy resulted in absolute risk reductions of 17%–29% for the primary end point and 15%–22% for the secondary end point. Corresponding numbers needed to treat were four to six and five to seven, respectively. This sizeable risk reduction translated into an additional 7.4 years free from the primary composite end point between the ages of 50 and 75 when treated with the ACEi plus SGLT2i combination. Treatment benefits declined, but were still significant, when therapy was started later than age 50, with improvements of 5.6, 3.6, and 2.8 years when treatment was initiated at ages 55, 60, and 65 years, respectively. In a sensitivity analysis using observational data from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort, participants with nondiabetic CKD who were not treated with ACEi/ARB therapy showed similar results, with combination therapy expected to provide a benefit of 7.7 years of eventfree survival. The authors explored variations in effect size depending on less than fully additive models, lower adherence, and loss of efficacy over time. Even when all three variables were projected as suboptimal, eventfree years gained remained meaningful at 3.7 years.

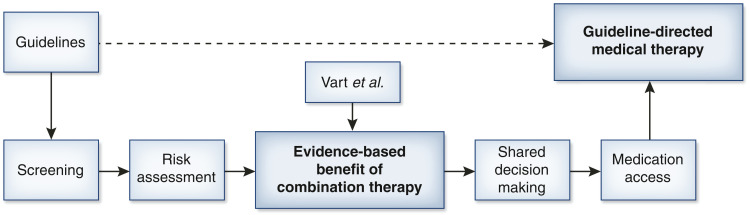

The work by Vart et al. (6) thus provides the first clear, evidence-derived assessments of the tangible benefits of combination ACEi/ARB and SGLT2i therapy to patients with albuminuric, nondiabetic kidney disease. These data provide an entryway for nephrology to implement goal-directed medical therapy in CKD (Figure 1). Such information will prove invaluable for providers, both in how they balance the risks and benefits of therapy and in joint decision making. Ideally, such information will translate to improved personalized risk assessments, such as the Kidney Failure Risk Equation (10), if it was to include estimates with versus without treatments, assisting patients and providers in the decision to advance therapy. The authors are also to be commended for integrating age into their calculated benefit from combination therapy, as they note that competing risks are greater with advancing age, resulting in diminished effect size. This notion is particularly relevant to the rising elderly population, in whom CKD is highly prevalent but who often have greater treatment burdens, altering the risk to benefit profile.

Figure 1.

Proposed flow chart for establishing guideline-directed medical therapy. The dashed arrow represents the theoretical direct connection between guidelines and therapy, whereas the solid arrows represent the necessary steps to real-world implementation. The figure is focused on a specific guideline for combination therapy and puts the work of Vart et al. into context.

The impressive findings by Vart et al. (6) also provide a tool for advocacy efforts to improve access to and coverage for nephroprotective medicines, especially SGLT2is, which are currently cost prohibitive to many, particularly those who are most in need. Although SGLT2is are expected to become generic over the next few years, the drug pipeline for CKD consists of other recently approved treatments, and more appear to be on the way. The ability to convey the importance of slowing CKD progression to policy makers and payors is critical to maximizing the broad availability of these medications. Study methods allowing for indirect comparisons, such as those used in this study, will also become increasingly important as more treatments become available, such that we can tailor combinations that are better suited to specific populations.

Lastly, the major effect made by combination therapy to disease prevention provides a platform from which to launch guidelines for albuminuria screening in people without diabetes but still at high risk of progressive CKD. In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) decided against review or update to recommendations for CKD screening. Much has changed since 2012, including an increase in the appreciation of CKD risk factors apart from diabetes and hypertension, including cardiovascular disease, obesity, and genetic factors, particularly APOL1-associated kidney disease in people of African ancestry. The importance of CKD as a “coronary equivalent” and the role that both eGFR and urine albumin-creatinine ratio play in the independent risk for future cardiovascular events and death have also come to the forefront. Lastly, as evidenced by the article from Vart et al. (6), we now have clearly effective therapies for nondiabetic CKD, and at least for now, the presence of albuminuria is a major indicator for ACEi/ARB and SGLT2i use. USPTF has again been asked to consider review of albuminuria screening for people at risk, regardless of the presence of diabetes, and hopefully, the results from this study will be considered.

Nephrology is on the cusp of an era of evidence-based medical therapy that will reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with CKD. The development of new treatments has been critical to reaching this point, but equally essential is their implementation in order for patients to be afforded their benefit. Cardiology has led the way in guideline-directed medical therapy, and nephrology now has the opportunity to follow suit. A shared understanding of the benefits of combination medical therapy is a crucial first step.

Disclosures

A.K. Mottl reports consulting fees from Bayer and Chinook; research funding from Alexion, Aurinia, Bayer, Calliditas, the Duke Clinical Research Institute, Pfizer, and the University of Pennsylvania; honoraria from Bayer and UpToDate; and advisory or leadership roles for Bayer and Chinook. E.M. Zeitler's spouse reports research funding from Dexcom, Novo Nordisk, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, and VTV Therapeutics.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related article, “Estimated Lifetime Benefit of Combined RAAS and SGLT2 Inhibitor Therapy in Patients with Albuminuric CKD without Diabetes,” on pages 1754–1762.

Author Contributions

A.K. Mottl and E.M. Zeitler conceptualized the study; A.K. Mottl provided supervision; A.K. Mottl and E.M. Zeitler wrote the original draft; and A.K. Mottl and E.M. Zeitler reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hundemer GL, Tangri N, Sood MM, Ramsay T, Bugeja A, Brown PA, Clark EG, Biyani M, White CA, Akbari A: Performance of the kidney failure risk equation by disease etiology in advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1424–1432, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, Grams ME, Ix JH, Jha V, Kengne AP, Madero M, Mihaylova B, Tangri N, Cheung M, Jadoul M, Winkelmayer WC, Zoungas S; Conference Participants : The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 99: 34–47, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamprea-Montealegre JA, Madden E, Tummalapalli SL, Chu CD, Peralta CA, Du Y, Singh R, Kong SX, Tuot DS, Shlipak MG, Estrella MM: Prescription patterns of cardiovascular- and kidney-protective therapies among patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease [published online ahead of print September 23, 2022]. Diabetes Care 10.2337/dc22-0614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiao Y, Shin JI, Chen TK, Sang Y, Coresh J, Vassalotti JA, Chang AR, Grams ME: Association of albuminuria levels with the prescription of renin-angiotensin system blockade. Hypertension 76: 1762–1768, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eberly LA, Yang L, Eneanya ND, Essien U, Julien H, Nathan AS, Khatana SAM, Dayoub EJ, Fanaroff AC, Giri J, Groeneveld PW, Adusumalli S: Association of Race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor use among patients with diabetes in the US. JAMA Netw Open 4: e216139, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vart P, Vaduganathan M, Jongs N, Remuzzi G, Wheeler DC, Hou FF, McCausland F, Chertow GM, Heerspink HJL: Estimated lifetime benefit of combined RAAS and SGLT2 inhibitor therapy in patients with albuminuric CKD without diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1754–1762, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia) : Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. Lancet 349: 1857–1863, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou FF, Zhang X, Zhang GH, Xie D, Chen PY, Zhang WR, Jiang JP, Liang M, Wang GB, Liu ZR, Geng RW: Efficacy and safety of benazepril for advanced chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 354: 131–140, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, Mann JFE, McMurray JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, Sjöström CD, Toto RD, Langkilde AM, Wheeler DC; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators : Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 383: 1436–1446, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, Coresh J, Appel LJ, Astor BC, Chodick G, Collins AJ, Djurdjev O, Elley CR, Evans M, Garg AX, Hallan SI, Inker LA, Ito S, Jee SH, Kovesdy CP, Kronenberg F, Heerspink HJ, Marks A, Nadkarni GN, Navaneethan SD, Nelson RG, Titze S, Sarnak MJ, Stengel B, Woodward M, Iseki K; CKD Prognosis Consortium : Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: A meta-analysis. JAMA 315: 164–174, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]