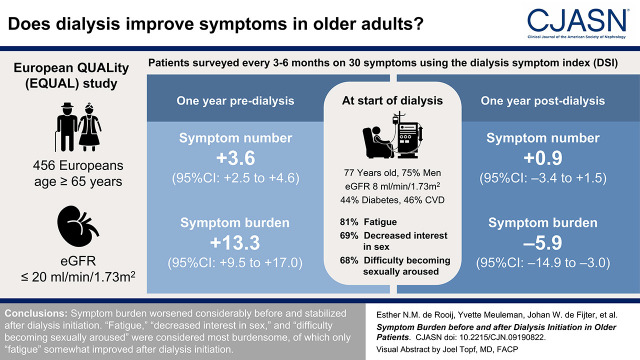

Visual Abstract

Keywords: dialysis, end stage kidney disease, epidemiology and outcomes, elderly, chronic kidney disease

Abstract

Background and objectives

For older patients with kidney failure, lowering symptom burden may be more important than prolonging life. Dialysis initiation may affect individual kidney failure–related symptoms differently, but the change in symptoms before and after start of dialysis has not been studied. Therefore, we investigated the course of total and individual symptom number and burden before and after starting dialysis in older patients.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The European Quality (EQUAL) study is an ongoing, prospective, multicenter study in patients ≥65 years with an incident eGFR ≤20 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Using the dialysis symptom index (DSI), 30 symptoms were assessed every 3–6 months between 2012 and 2021. Scores for symptom number range from zero to 30 and, for burden, from zero to 150, with higher scores indicating more severity. Using mixed effects models, we studied symptoms during the year preceding and the year after dialysis initiation.

Results

We included 456 incident patients on dialysis who filled out at least one DSI during the year before or after dialysis. At dialysis initiation, mean (SD) participant age was 76 (6) years, 75% were men, mean (SD) eGFR was 8 (3) ml/min per 1.73 m2, 44% had diabetes, and 46% had cardiovascular disease. In the year before dialysis initiation, symptom number increased +3.6 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], +2.5 to +4.6) and symptom burden increased +13.3 (95% CI, +9.5 to +17.0). In the year after, symptom number changed −0.9 (95% CI, −3.4 to +1.5) and burden decreased −5.9 (95% CI, −14.9 to −3.0). At dialysis initiation, “fatigue,” “decreased interest in sex,” and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” had the highest prevalence of 81%, 69%, and 68%, respectively, with a burden of 2.7, 2.4, and 2.3, respectively. “Fatigue” somewhat improved after dialysis initiation, whereas the prevalence and burden of sexual symptoms further increased.

Conclusions

Symptom burden worsened considerably before and stabilized after dialysis initiation. “Fatigue,” “decreased interest in sex,” and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” were considered most burdensome, of which only “fatigue” somewhat improved after dialysis initiation.

Introduction

Globally, the number of older (≥65 years) patients with kidney failure doubled over the past three decades, mainly driven by the increasing prevalence of diabetes and hypertension (1,2). CKD-related symptom burden increases considerably as kidney function declines and is more pronounced in the elderly (3–6). Because older patients with kidney failure are frequently ineligible for kidney transplantation due to comorbidity, dialysis is the most common KRT (7). Given the limited life expectancy and treatment options in older patients with kidney failure, the goal of dialysis initiation can be to improve quality of life by lowering symptom burden rather than primarily the prolongation of life (8–10).

The 2019 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guideline identified “To what extent do uremic symptoms change after initiation of dialysis?” as a knowledge gap (11). Indeed, uremic toxins may cause kidney failure–related symptom burden and adversely affect health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (12,13). Dialysis treatment, however, does not effectively remove uremic toxins bound to proteins (14,15). Furthermore, both uremic and nonuremic kidney failure–related symptoms often have a multifactorial origin, and dialysis will not treat all causes (16). Finally, dialysis treatment itself can lead to the development of symptoms.

We recently showed that older patients experienced a clinically relevant decline of both mental and physical HRQOL before dialysis initiation, which stabilized thereafter (17). A better understanding of the effect of dialysis initiation on individual kidney failure–related symptoms is essential for targeting interventions and addressing those symptoms that contribute most to overall symptom burden to improve HRQOL (12). Furthermore, knowledge on the evolution of symptoms before and after dialysis initiation could aid both nephrologists and patients who decided to start dialysis. This is especially relevant for older patients with kidney failure, considering their limited life expectancy and treatment options. To our knowledge, the change in symptom burden before and after the initiation of dialysis has not been studied before in older patients, although dialysis may affect individual kidney failure–related symptoms differently in this population. Therefore, our aim is to investigate the evolution of total symptom number and burden and individual symptoms in the year before and after starting dialysis in older patients with kidney failure.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

The European Quality (EQUAL) study on treatment in advanced CKD, starting April 2012, is an ongoing, prospective, multicenter follow-up study in six European countries: Germany, Italy, Poland, Sweden, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. All patients gave informed consent, and all local medical ethics committees or corresponding institutional review boards (as appropriate) approved the study. A full description of the EQUAL study has been published elsewhere (18). Briefly, patients ≥65 years with advanced CKD followed in a nephrology clinic were included with an incident eGFR drop to or below 20 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the last 6 months. Patients were excluded when the eGFR drop was the result of an acute event or when a history of KRT was present. Identified patients who met the eligibility criteria were consecutively approached. Patients were followed every 3–6 months until kidney transplantation, death, refusal for further participation, transfer to a nonparticipating center, loss to follow-up, or end of follow-up, whichever came first. For the analyses, we included all patients who started dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) and filled out at least one symptom questionnaire during the year before or after dialysis initiation. End of follow-up was in December 2021, when the data were extracted.

Data Collection

In the EQUAL study, patients were followed while receiving routine medical care as provided by their nephrology clinic. Data were collected every 3–6 months and entered into a web-based clinical record form that was developed for this specific purpose. Extra follow-up visits were conducted at dialysis initiation and after the eGFR dropped <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for the first time. The collected information included patients’ demographics, ethnicity, primary kidney disease, comorbid conditions, physical examination, and laboratory data. All laboratory investigations and physical examinations were performed through standard protocols and procedures according to routine care at the local participating centers. Subsequently, all data were recalculated into one uniform unit of choice. The eGFR was calculated according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (19). Primary kidney disease was classified by the treating nephrologist according to the codes of the European Renal Association (ERA) (20).

Kidney failure–related symptoms were assessed every 3–6 months using the dialysis symptom index (DSI; Supplemental Table 1), a previously validated questionnaire (21). Through this questionnaire, patients indicated the presence of 30 symptoms in the past month, resulting in a total sum score for symptom number ranging from 0 to 30. Additionally, for each symptom present, patients rated symptom burden on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one for “not at all” to five for “very much” burdensome. Absent symptoms were assigned a score of zero, resulting in an overall symptom burden score ranging from zero to 150, with higher scores indicating larger burden.

Statistical Analyses

For this study, baseline was defined as the date of the first dialysis treatment. Baseline characteristics are presented as mean±SD, median (interquartile range), or number (proportion), where appropriate.

First, we used linear mixed models to explore the evolution of the total symptom number and burden during the year preceding and after dialysis initiation. A random intercept and slope for time were used to account for repeated measurements, allowing the trajectory over time to vary between individuals. We assumed the relation between symptoms and time to be nonlinear around dialysis initiation. Therefore, we modeled time in a three-knot restricted cubic spline function with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) to allow for more flexibility (22). The knots were chosen at dialysis initiation, 0.5 year before dialysis initiation, and 0.5 year after dialysis initiation. We repeated this analysis with additional knots at 1 or 3 months before and after dialysis initiation. Finally, we repeated this model with adjustments for age, sex, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease to correct for symptom data missing at random (23).

Second, we compared linear change in total symptom number and burden during the year before with the linear change after dialysis initiation. In these linear mixed models, we used three fixed variables to allow for a discontinuous change at dialysis initiation: (1) time, (2) indicator whether dialysis was already started (yes or no), and (3) interaction between time and the indicator.

Third, for individual symptoms, we assessed the prevalence and burden at dialysis initiation. For this analysis, we included all participants (n=278) who completed a questionnaire during the 30 days before or after dialysis initiation. If a symptom was scored as present but the accompanying burden score was missing, the latter was indicated as “score missing.”

Fourth, for individual symptoms, we studied the evolution of prevalence and burden during 1 year before and after dialysis initiation. For symptom prevalence, we used logistic mixed effects models (24). For symptom burden, we used linear mixed effects models. Follow-up time was added as a restricted cubic spline, with knots at dialysis initiation, 0.5 year before dialysis initiation, and 0.5 year after dialysis initiation.

Fifth, we studied the linear change of symptom burden before and after dialysis initiation in various subgroups. The methods and results of these analyses are described in Supplemental Tables 2–5.

Finally, we conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we restricted follow-up time to 6 months after dialysis initiation. Patients who died in the year after dialysis initiation were no longer able to fill out questionnaires. Because these patients may have experienced a worse symptom burden than those who survived, informative dropout due to death should be considered. Second, we extended the inclusion and follow-up time to 3 years before dialysis initiation. This extended inclusion was made because, in our main analyses, we only included patients with at least one symptom number or burden score available in the 1 year before or after dialysis. All analyses were performed using R version 4.0.3 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Follow-Up

Of all EQUAL participants who started dialysis (n=590), defined as baseline, 456 patients filled a DSI questionnaire during the 1 year before or after dialysis initiation and were thus included (Supplemental Figure 1). No relevant baseline differences were observed between included and excluded patients (Supplemental Table 6). For included patients at dialysis initiation, mean±SD age was 76±6 years, 75% were men, 96% were White, 44% had diabetes, 9% were current smokers, 46% had a history of cardiovascular disease, the mean±SD eGFR was 8±3 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and mean±SD hemoglobin was 10.3±1.5 g/dl (Table 1). Mean±SD symptom number and burden was 16±7 and 49±24, respectively. During 1 year after dialysis initiation, 74 (16%) patients died, of whom 24 and 41 within 3 and 6 months of follow-up, respectively. Of the patients who died, 64% completed at least one DSI after dialysis initiation.

Table 1.

Characteristics and symptom number and burden of 456 participants in the European Quality study on treatment of older people with advanced CKD at start of dialysis

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 76 (6) |

| Men, n (%) | 343 (75) |

| Country, n (%) | |

| Germany | 77 (17) |

| Italy | 91 (20) |

| The Netherlands | 69 (15) |

| Poland | 35 (8) |

| Sweden | 93 (20) |

| United Kingdom | 91 (20) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 317 (71) |

| Divorced | 27 (6) |

| Widowed | 82 (19) |

| Never married | 19 (4) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Low | 95 (25) |

| Intermediate | 225 (54) |

| High | 90 (21) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Primary kidney disease, n (%) | |

| Diabetes | 110 (24) |

| Hypertension | 124 (27) |

| Systemic/glomerular disease | 116 (26) |

| Other/unknown | 106 (23) |

| Dialysis modality, n (%) | |

| Hemodialysis | 325 (77) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 99 (23) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 6.9 (1.9) |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 199 (44) |

| History of cardiovascular disease, n (%)a | 200 (46) |

| History of heart failure, n (%) | 77 (18) |

| History of chronic lung disease, n (%) | 53 (12) |

| History of malignancy, n (%) | 95 (22) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 40 (9) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD)b | 28 (6) |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg), mean (SD)b | 147 (22) |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg), mean (SD)b | 75 (11) |

| Blood chemistry b | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl), mean (SD)c | 10.3 (1.5) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl), mean (SD)d | 6.6 (2.3) |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2), mean (SD)e | 8 (3) |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dl), mean (SD)f | 92 (42) |

| Uric acid (mg/dl), mean (SD)g | 7.4 (1.9) |

| Albumin (g/dl), mean (SD)h | 3.5 (0.6) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl), mean (SD)i | 159 (54) |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/ml), median (IQR)j | 218 (141–396) |

| Dialysis symptom index, mean (SD) b | |

| Symptom number | 16 (7) |

| Symptom burden | 48 (24) |

BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

Cardiovascular disease was defined as any history of a cerebral vascular accident, a myocardial infarction, or peripheral vascular disease.

Measured at start of dialysis or within 30 days before start of dialysis.

To convert the values for hemoglobin to millimoles per liter, divide by 1.61.

To convert the values for creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.40.

eGFR was estimated on the basis of serum creatinine using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula.

To convert the values for urea nitrogen to milllimoles per liter, multiply by 0.3571.

To convert the values for uric acid to micromoles per liter, multiply by 59.48.

To convert the values for albumin to grams per liter, multiply by 10.

To convert the values for cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.02586.

To convert the values for parathyroid hormone to picomoles per liter, divide by 9.43.

Questionnaires

In total, 1497 DSI questionnaires were available during the year before and after dialysis initiation, with an average of 3.3 questionnaires per patient (Supplemental Figure 2). On average, questionnaires were missing in 18% and 35% of all follow-up visits in the year before or after dialysis initiation, respectively. Of all included patients, 320 (70%) completed a DSI both before and after dialysis initiation, with a median (interquartile range) of 135 (90–184) days between questionnaires. Of the remaining 137 (30%) patients, 121 only filled DSI questionnaires before and 16 only after dialysis initiation. Missing follow-up visits and questionnaires are shown in Supplemental Table 7.

Evolution of Symptom Burden and Individual Symptoms

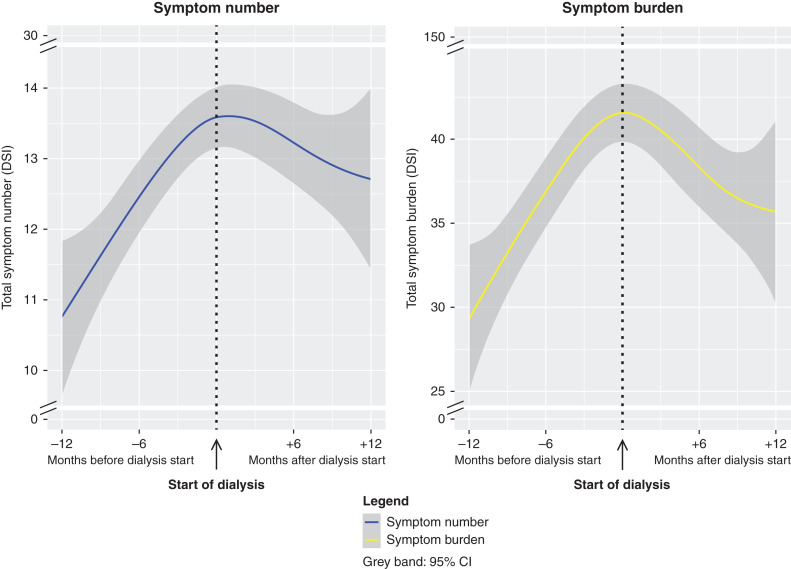

We observed a clear increase in symptom number and burden during the year before dialysis initiation, which stabilized thereafter (Figure 1). Modeling time with knots closer to dialysis initiation, at −3 and +3 or −1 and +1 months before and after dialysis, or adjustments for age, sex, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease showed similar results (Supplemental Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

Symptom number and symptom burden worsened considerably in the year before and stabilized in the year after start of dialysis in 456 older patients. These results represent the change in total symptom number and burden during the year preceding and after dialysis initiation. To obtain these results, linear mixed models were used in which time (days before or after start of dialysis) was modeled in a three-knot restricted cubic spline function with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) to allow for more flexibility. The knots were chosen at the start of dialysis initiation, 6 months before dialysis initiation, and 6 months after start of dialysis initiation. A random intercept and slope for time were used to account for repeated measurements, allowing the trajectory before and after the discontinuity to vary between individuals. DSI, dialysis symptom index.

During the year preceding dialysis, mean symptom number and burden increased +3.6 (95% CI, +2.5 to +4.6) and +13.3 (95% CI, +9.5 to +17.0), respectively (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 5). In the year after dialysis initiation, mean symptom number changed −0.9 (95% CI, −3.4 to +1.5) and burden decreased −5.9 (95% CI, −14.9 to −3.0), respectively (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 5).

Table 2.

Evolution of symptom number and burden before and after start of dialysis in older patients

| Period of Time | Symptom Number, Change (95% Confidence Interval) | Symptom Burden, Change (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Main analyses (n=456) | ||

| −1 year before to start of dialysis | +3.6 (+2.5 to +4.6) | +13.3 (+9.5 to +17.0) |

| Start of dialysis to +1 year after | −0.9 (−3.4 to +1.5) | −5.9 (−14.9 to −3.0) |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||

| −3 years before to start of dialysis (n=496) | +3.2 (+2.2 to +4.3) | +12.9 (+9.1 to +16.8) |

| Start of dialysis to +0.5 year after (n=449) | −3.6 (−7.7 to +0.5) | −19.9 (−35.2 to −4.5) |

These results represent linear changes in symptom number and burden during different time periods before or after dialysis initiation. For example, symptom number increased +3.2 (95% confidence interval, +2.2 to +4.3) in total during the 3 years before dialysis initiation. Linear changes were calculated with linear mixed models in which we used three fixed variables to allow for a discontinuous change at start of dialysis initiation: (1) time, (2) indicator whether dialysis was already started (yes or no), and (3) interaction between time and the indicator. In this model, the interaction term estimates the difference in change before and after start dialysis. A random intercept and slope for time were used to account for repeated measurements, allowing the trajectory before and after the discontinuity to vary between individuals.

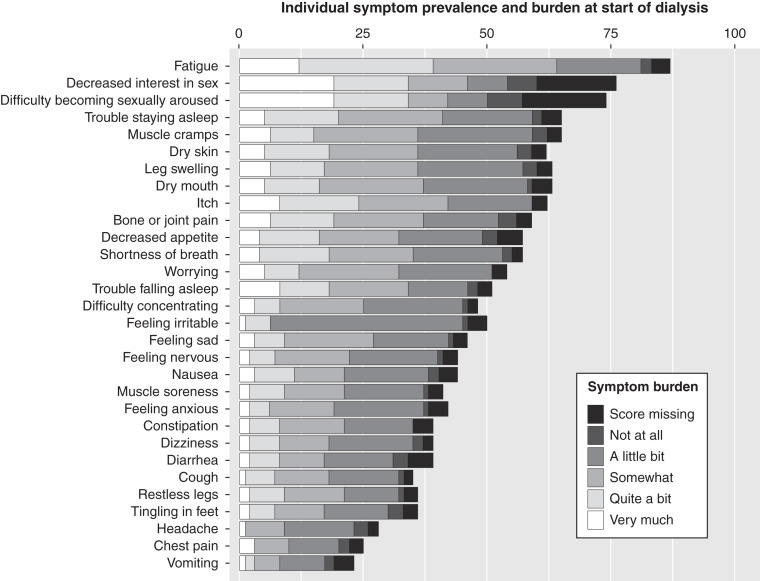

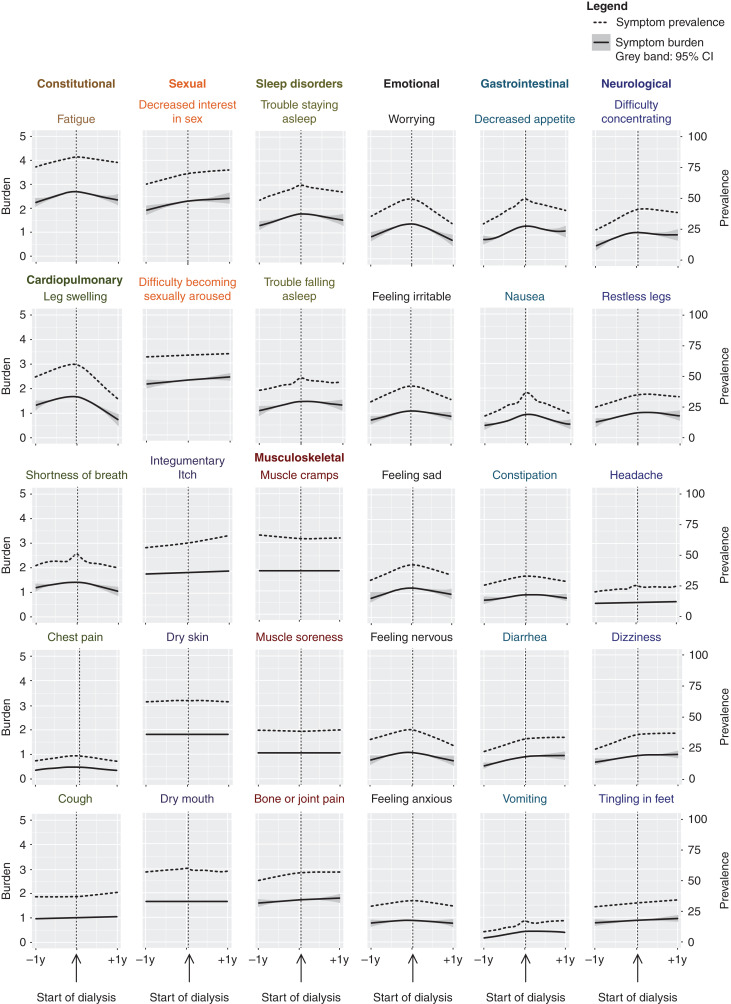

The prevalence and burden of the 30 individual symptoms at dialysis initiation (n=278) is shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 8 demonstrate the change of prevalence and burden for all 30 individual symptoms during the year before and after dialysis initiation (n=456). We present symptoms grouped in nine symptom systems according to the review of systems (Supplemental Table 2) (25). “Fatigue,” “decreased interest in sex,” and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” had the highest prevalence and burden during the year before and after dialysis, which peaked at dialysis initiation with a prevalence of 81%, 69%, and 68%, respectively, and a mean burden of 2.7, 2.4, and 2.3, respectively. Overall, the prevalence and burden of cardiopulmonary symptoms, emotional symptoms, sleep disorders, and fatigue mostly increased during the year before and stabilized or decreased after dialysis initiation. The prevalence and burden of gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms also increased in the year before dialysis initiation, but afterward only decreased in half of the symptoms concerned, the other half increased further. The prevalence and burden of sexual, integumentary, and musculoskeletal symptoms also increased further after dialysis initiation or did not change at all (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 8).

Figure 2.

At dialysis initiation, “fatigue,” “decreased interest in sex,” and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” had the highest mean symptom prevalence and burden (x axis) according to the five-point Likert scale (legend) of 30 kidney failure–related symptoms in 278 older patients during the 30 days before and after start of dialysis.

Figure 3.

“Fatigue,” “decreased interest in sex,” and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” were the most prevalent and burdensome of all 30 kidney failure-related symptoms during the year before and after starting dialysis. Prevalence (dotted line, right y axis) and burden (solid line, left y axis) of 30 kidney failure–related symptoms in the year before and after start of dialysis in 456 older patients, ordered by their nine corresponding symptom systems.

Sensitivity Analyses

After restriction of follow-up to 6 months after dialysis initiation, mean (95% CI) symptom number and burden declined by −3.6 (95% CI, −7.7 to +0.5) and −19.9 (95% CI, −35.2 to −4.5) (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 6). By extending inclusion and follow-up time from 1 year to 3 years before dialysis initiation, we included 40 extra patients and found that mean (95% CI) symptom number and burden increased by +3.2 (95% CI, +2.2 to +4.3) and +12.9 (95% CI, +9.1 to +16.8) (Table 2). This increase was mainly driven by changes in the year before dialysis initiation (Supplemental Figure 7). Thus, the results of these sensitivity analyses are in line with the main results.

Discussion

In this large, European, multicenter cohort of 456 older incident patients on dialysis, we found a considerable increase in symptom burden before dialysis initiation that stabilized thereafter. In the year before dialysis, symptom number and burden increased +3.6 and +13.3, and stabilized or decreased with changes of −0.9 and −5.9 in the year after dialysis initiation. At the start of dialysis, the most common symptoms with the highest burden were “fatigue” (81%, burden 2.7), “decreased interest in sex” (69%, burden 2.4), and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” (68%, burden 2.3).

Most previous studies assessing symptom burden in patients with advanced CKD did so cross-sectionally (26). Studies investigating longitudinal symptom evolution were often limited to either patients not on dialysis or patients on dialysis (27,28). Patients with CKD stage 4–5 have a high symptom burden and may suffer from six to 20 kidney failure–related symptoms (29). This symptom burden increases by 0.5–2.9 symptoms as kidney function declines (27,30,31). An increase in symptom burden may negatively affect HRQOL and is associated with a combined poor health outcome of starting dialysis, receiving a kidney transplant, or death (5,31). We are the first to study symptom burden longitudinally before and after dialysis initiation in older patients.

“Fatigue,” “decreased interest in sex,” and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” were the most prevalent and burdensome symptoms during the year before and after dialysis initiation. These results are in line with a recent study among 512 patients on dialysis showing that “fatigue” was the most common and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” the most bothersome symptom (32). The high burden of fatigue in older patients starting dialysis is often multifactorial, among others including older age, low residual kidney function, uremic toxins, heart failure, anemia, high ultrafiltration volume, anxiety, depression, and poor sleep quality (12,13,33). The prevalence and burden of decreased interest in sex and difficulty becoming sexually aroused did not improve after dialysis initiation, which is in line with a study investigating the evolution of sexual dysfunction in 43 patients on maintenance dialysis (34). Research on sexual dysfunction in CKD is scarce, but several studies showed various underlying factors, such as stress, fatigue, antihypertensive use, presence of dialysis access device, and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (35,36). Furthermore, aging is associated with physiologic changes in sexual function. However, chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, may accelerate progression of sexual dysfunction (37,38).

We found different patterns of evolution in the year before and after dialysis initiation among the 30 kidney failure–related symptoms that we studied. Although some of these 30 symptoms improved, almost half (e.g., “cough,” “itch,” “tingling in feet,” “diarrhea,” and sexual symptoms) only stabilized or further worsened after dialysis initiation. The change in burden may differ depending on the effect of dialysis initiation and the origin of the experienced symptoms. First, cardiopulmonary symptoms, such as “leg swelling” and “shortness of breath,” clearly improved after dialysis initiation, as could be expected after a better control of fluid overload due to dialysis treatment. Second, in contrast, the burden of itch, a classic uremic symptom, did not improve after dialysis initiation. This is in line with previous studies that also found a high burden of itching in patients on dialysis (39,40). This may be partly explained by the fact that dialytic clearance of uremic toxins is limited to the unbound fraction that can diffuse across the dialysis membrane (14,15). Protein-bound uremic toxins are cleared via tubular secretion, for which residual kidney function is essential (15). Indeed, previous research suggests that patients with residual kidney function experience less uremic symptoms (41).

Third, dialysis treatment itself can induce symptoms, such as pain from vascular access cannulation and muscle cramps or headache from excess volume removal and electrolyte fluctuations (12,42). We found no change in muscle cramps and headache after dialysis initiation, although these symptoms did not alter in the year preceding dialysis initiation either. The increase in burden of all emotional symptoms observed in the year before dialysis might partly be explained by fear of dialysis treatment, and the burden of these symptoms, in particular “worrying,” indeed somewhat improved after dialysis initiation (43). Finally, symptoms can be multifactorial and, especially in the elderly, can also be driven by comorbidities or medication use (12,44).

Our results emphasize the importance of identifying and discussing kidney failure–related symptoms in routine clinical care and considering their differing patterns of evolution before and after dialysis initiation (12). Indeed, increased physician awareness may lead to better symptom control and improve total symptom burden (45). Furthermore, inquiring about sexual symptoms may help patients to address these sensitive but burdensome symptoms. As patient-reported outcome measures, such as symptom questionnaires, are becoming more frequently incorporated in routine nephrology clinical care, individual symptom burden can now be measured in a standardized manner (46). Routine use of symptom questionnaires might help clinicians in addressing symptoms important to the individual patient. However, considering multifactorial causes or limited effective treatment options, adequate management of identified symptoms may remain a challenge.

Two phenomena need to be considered for an appropriate interpretation of our results. First, patients starting dialysis are partly selected on their relatively high or increased symptom burden shortly before dialysis initiation, because symptoms are one of the reasons for dialysis initiation (11). Because of this selection, regression to the mean may, to some extent, explain a decrease in symptom burden after dialysis initiation (47). Second, response shift might also contribute to the stabilization of symptom burden after dialysis initiation. Response shift is a change in the meaning of one’s evaluation of a self-reported outcome over time (48). Because dialysis initiation is an event with a large effect on daily life, the frame of reference of a patient on dialysis might differ from that before dialysis initiation. Through this, response shift could have a beneficial effect on the experienced symptom burden after dialysis initiation.

There are several strengths to our study. First, we used a validated questionnaire to assess the presence of a broad spectrum of kidney failure–related symptoms and their burden longitudinally, both before and after dialysis initiation, in a large cohort of older patients. This allowed us, for the first time, to describe the evolution of this important patient-reported outcome before and after dialysis initiation. Second, we included older patients from six European countries, whereas previous studies were often restricted to a single nation or center. Because the origin and perception of symptom burden and treatment strategies can vary across country and nationality, our broad patient sample will increase the generalizability of our results (49).

Our study also has some limitations. First, we could not include all EQUAL patients on dialysis in this analysis because DSI questionnaires were only available in 77% of all patients on dialysis during the year before and after dialysis initiation. However, clinical characteristics at dialysis initiation did not differ between included and excluded EQUAL patients on dialysis. Second, in 32% of all study visits during follow-up, a DSI was missing. By using linear mixed effects models, we could take into account symptom data missing completely at random (e.g., a study coordinator forgot to send out a DSI) and missing at random (e.g., women are more likely to complete questionnaires), but not data missing not at random (e.g., a DSI not completed because a patient feels too sick and did not report this) (23). The latter may have resulted in an underestimation of symptom scores. However, adjusting for age, sex, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease showed similar results. Third, 16% of the older patients on dialysis in our study died in the year after dialysis initiation. This 1-year mortality rate is comparable to the rate of 15% established in 65- to 75-year-old European patients on dialysis and somewhat lower than the value of 24% of European patients on dialysis who are >75 years old (50). After restriction of follow-up time to 6 months after starting dialysis, symptom number and burden declined even more. This may imply that informative dropout due to death did not result in a large overestimation of the symptom burden that we calculated 1 year after dialysis initiation. Fourth, the effect of frailty on symptoms could not be assessed because frailty was not formally measured. Fifth, we only assessed patients starting dialysis and could not investigate symptom burden in patients not starting dialysis, e.g., those treated with conservative care or those who died before initiating dialysis. Therefore, our results can only inform patients with kidney failure who already decided to start dialysis and will survive up to dialysis initiation. Because conservative care is becoming increasingly considered as an alternative to dialysis initiation in patients who are frail or older, assessing its effect on symptom burden would be important.

In conclusion, our results indicate that, on average, symptom number and burden worsened considerably during the year preceding dialysis, but stabilized after dialysis initiation. During the year before and after dialysis initiation, “fatigue,” “decreased interest in sex,” and “difficulty becoming sexually aroused” were the most burdensome symptoms. The pattern of symptom burden evolution varied among individual symptoms, possibly because of their different causes. These results could help inform older patients with kidney failure who decided to start dialysis on what to expect regarding the development of their symptom burden.

Disclosures

F.J. Caskey reports serving in unpaid advisory or leadership roles for International Society of Nephrology (treasurer, honorary secretary, executive committee member), and receiving research funding from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). F.W. Dekker reports receiving research funding from Astellas, Chiesi, and Vifor. C. Drechsler reports receiving research funding from Genzyme. M. Evans reports receiving an institutional grant from Astellas Pharma; receiving payment for lectures by Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care, and Vifor Pharma; serving in advisory or leadership roles for Astellas, AstraZeneca, and Vifor Pharma advisory boards; having consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca and Vifor Pharma; and serving as a member of the European Renal Association (ERA) Registry Committee and a member of the steering committee of the Swedish Renal Registry. K.J. Jager reports serving on the editorial boards of African Journal of Nephrology, Journal of Renal Nutrition, Kidney International Reports, and Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation and serving on the European Renal Best Practice Committee of the ERA; this was all unpaid. C. Wanner reports having consultancy agreements with Akebia, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, Glaxo-SmithKline, MSD, Sanofi, Tricida, and Vifor; receiving honoraria from Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, FMC, Eli-Lilly, Sanofi, and Takeda; serving as president of, and having other interests in, or relationships with, the ERA; and receiving an Idorsia grant (to institution) and a Sanofi grant (to institution). All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was mainly funded by the European Renal Association (ERA) and contributions from the Swedish Medical Association (SLS), the Stockholm County Council ALF Medicine and Center for Innovative Research (CIMED), the Italian Society of Nephrology (SIN-Reni), the Dutch Kidney Foundation (SB 142), the Young Investigators Grant in Germany, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in the United Kingdom.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the patients and health professionals participating in the EQUAL study.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: EQUAL study investigators, Andreas Schneider, Anke Torp, Beate Iwig, Boris Perras, Christian Marx, Christiane Drechsler, Christof Blaser, Christoph Wanner, Claudia Emde, Detlef Krieter, Dunja Fuchs, Ellen Irmler, Eva Platen, Hans Schmidt-Gürtler, Hendrik Schlee, Holger Naujoks, Ines Schlee, Sabine Cäsar, Joachim Beige, Jochen Röthele, Justyna Mazur, Kai Hahn, Katja Blouin, Katrin Neumeier, Kirsten Anding-Rost, Lothar Schramm, Monika Hopf, Nadja Wuttke, Nikolaus Frischmuth, Pawlos Ichtiaris, Petra Kirste, Petra Schulz, Sabine Aign, Sandra Biribauer, Sherin Manan, Silke Röser, Stefan Heidenreich, Stephanie Palm, Susanne Schwedler, Sylke Delrieux, Sylvia Renker, Sylvia Schättel, Theresa Stephan, Thomas Schmiedeke, Thomas Weinreich, Til Leimbach, Torsten Stövesand, Udo Bahner, Wolfgang Seeger, Adamasco Cupisti, Adelia Sagliocca, Alberto Ferraro, Alessandra Mele, Alessandro Naticchia, Alex Còsaro, Andrea Ranghino, Andrea Stucchi, Angelo Pignataro, Antonella De Blasio, Antonello Pani, Aris Tsalouichos, Bellasi Antonio, Biagio Raffaele Di Iorio, Butti Alessandra, Cataldo Abaterusso, Chiara Somma, Claudia D’alessandro, Claudia Torino, Claudia Zullo, Claudio Pozzi, Daniela Bergamo, Daniele Ciurlino, Daria Motta, Domenico Russo, Enrico Favaro, Federica Vigotti, Ferruccio Ansali, Ferruccio Conte, Francesca Cianciotta, Francesca Giacchino, Francesco Cappellaio, Francesco Pizzarelli, Gaetano Greco, Gaetana Porto, Giada Bigatti, Giancarlo Marinangeli, Gianfranca Cabiddu, Giordano Fumagalli, Giorgia Caloro, Giorgina Piccoli, Giovanbattista Capasso, Giovanni Gambaro, Giuliana Tognarelli, Giuseppe Bonforte, Giuseppe Conte, Giuseppe Toscano, Goffredo Del Rosso, Irene Capizzi, Ivano Baragetti, Lamberto Oldrizzi, Loreto Gesualdo, Luigi Biancone, Manuela Magnano, Marco Ricardi, Maria Di Bari, Maria Laudato, Maria Luisa Sirico, Martina Ferraresi, Michele Provenzano, Moreno Malaguti, Nicola Palmieri, Paola Murrone, Pietro Cirillo, Pietro Dattolo, Pina Acampora, Rita Nigro, Roberto Boero, Roberto Scarpioni, Rosa Sicoli, Rosella Malandra, Silvana Savoldi, Silvio Bertoli, Silvio Borrelli, Stefania Maxia, Stefano Maffei, Stefano Mangano, Teresa Cicchetti, Tiziana Rappa, Valentina Palazzo, Walter De Simone, Anita Schrander, Bastiaan van Dam, Carl Siegert, Carlo Gaillard, Charles Beerenhout, Cornelis Verburgh, Cynthia Janmaat, Ellen Hoogeveen, Ewout Hoorn, Friedo Dekker, Johannes Boots, Henk Boom, Jan-Willem Eijgenraam, Jeroen Kooman, Joris Rotmans, Kitty Jager, Liffert Vogt, Maarten Raasveld, Marc Vervloet, Marjolijn van Buren, Merel van Diepen, Nicholas Chesnaye, Paul Leurs, Pauline Voskamp, Peter Blankestijn, Sadie van Esch, Siska Boorsma, Stefan Berger, Constantijn Konings, Zeynep Aydin, Aleksandra Musiała, Anna Szymczak, Ewelina Olczyk, Hanna Augustyniak-Bartosik, Ilona Miśkowiec-Wiśniewska, Jacek Manitius, Joanna Pondel, Kamila Jędrzejak, Katarzyna Nowańska, Łukasz Nowak, Maciej Szymczak, Magdalena Durlik, Szyszkowska Dorota, Teresa Nieszporek, Zbigniew Heleniak, Andreas Jonsson, Anna-Lena Blom, Björn Rogland, Carin Wallquist, Denes Vargas, Emöke Dimény, Fredrik Sundelin, Fredrik Uhlin, Gunilla Welander, Isabel Bascaran Hernandez, Knut-Christian Gröntoft, Maria Stendahl, Maria Svensson, Marie Evans, Olof Heimburger, Pavlos Kashioulis, Stefan Melander, Tora Almquist, Ulrika Jensen, Alistair Woodman, Anna McKeever, Asad Ullah, Barbara McLaren, Camille Harron, Carla Barrett, Charlotte O'Toole, Christina Summersgill, Colin Geddes, Deborah Glowski, Deborah McGlynn, Dympna Sands, Fergus Caskey, Geena Roy, Gillian Hirst, Hayley King, Helen McNally, Houda Masri-Senghor, Hugh Murtagh, Hugh Rayner, Jane Turner, Joanne Wilcox, Jocelyn Berdeprado, Jonathan Wong, Joyce Banda, Kirsteen Jones, Lesley Haydock, Lily Wilkinson, Margaret Carmody, Maria Weetman, Martin Joinson, Mary Dutton, Michael Matthews, Neal Morgan, Nina Bleakley, Paul Cockwell, Paul Roderick, Phil Mason, Philip Kalra, Rincy Sajith, Sally Chapman, Santee Navjee, Sarah Crosbie, Sharon Brown, Sheila Tickle, Suresh Mathavakkannan, and Ying Kuan

Author Contributions

J.W. de Fijter, F.W. Dekker, E.K. Hoogeveen, and Y. Meuleman provided supervision; F.W. Dekker, E.N.M. de Rooij, E.K. Hoogeveen, and Y. Meuleman conceptualized the study and were responsible for methodology; E.N.M. de Rooij was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, and investigation; E.N.M. de Rooij and E.K. Hoogeveen wrote the original draft and were responsible for visualization; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.09190822/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Summary 1. Collaborator information.

Supplemental Table 1. Dialysis symptom index (DSI) symptom list.

Supplemental Table 2. The 30 symptoms from the dialysis symptom index (DSI) according to nine symptom systems.

Supplemental Table 3. Description of the methods and results of the conducted subgroup analyses.

Supplemental Table 4. Evolution of symptom number and burden in the year before and after start of dialysis within subgroups, adjusted for potential confounders.

Supplemental Table 5. Median (IQR) symptom number and burden scores at start of dialysis or within 30 days before start of dialysis per subgroup in those who filled a DSI at that time.

Supplemental Table 6. Characteristics of 590 patients in the European Quality (EQUAL) study on treatment of older people with advanced chronic kidney disease at start of dialysis.

Supplemental Table 7. The number (%) of patients who did or did not have a study visit of all included patients (n=456) within each follow-up interval.

Supplemental Table 8. Evolution of burden of 30 kidney disease-related symptoms in the year before and after start of dialysis in 456 older patients, ordered by their nine corresponding symptom systems.

Supplemental Figure 1. Flow diagram indicating the selection of EQUAL study participants.

Supplemental Figure 2. Histograms indicating the number of completed DSI questionnaires per dialysis patient in total (left) or during the year before or after start of dialysis (right).

Supplemental Figure 3. Evolution of symptom number (blue) and burden (yellow) with additional knots at 3 (left) and 1 (right) months before and after start of dialysis in 456 older patients.

Supplemental Figure 4. Evolution of symptom number (blue) and burden (yellow) in the year before and after start of dialysis in 456 older patients, with adjustments for age, sex, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in order to correct for symptom data missing at random explained by these variables.

Supplemental Figure 5. Linear change of symptom number (blue) and burden (yellow) in the year before and after start of dialysis in 456 older patients, including a discontinuous change at start of dialysis.

Supplemental Figure 6. Evolution of symptom number (blue) and burden (yellow) with restriction of follow-up to 1 year before and 0.5 year after start of dialysis in 449 older patients.

Supplemental Figure 7. Evolution of symptom number (blue) and burden (yellow) with extension of follow-up to 3 years before and 1 year after start of dialysis in 496 older patients.

References

- 1.Xie Y, Bowe B, Mokdad AH, Xian H, Yan Y, Li T, Maddukuri G, Tsai CY, Floyd T, Al-Aly Z: Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study highlights the global, regional, and national trends of chronic kidney disease epidemiology from 1990 to 2016. Kidney Int 94: 567–581, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoogeveen EK: The epidemiology of diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Dial 2: 433–442, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almutary H, Bonner A, Douglas C: Which patients with chronic kidney disease have the greatest symptom burden? A comparative study of advanced CKD stage and dialysis modality. J Ren Care 42: 73–82, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nixon AC, Wilkinson TJ, Young HML, Taal MW, Pendleton N, Mitra S, Brady ME, Dhaygude AP, Smith AC: Symptom-burden in people living with frailty and chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 21: 411, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Goeij MC, Ocak G, Rotmans JI, Eijgenraam JW, Dekker FW, Halbesma N: Course of symptoms and health-related quality of life during specialized pre-dialysis care. PLoS One 9: 93069, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janmaat CJ, van Diepen M, Meuleman Y, Chesnaye NC, Drechsler C, Torino C, Wanner C, Postorino M, Szymczak M, Evans M, Caskey FJ, Jager KJ, Dekker FW; EQUAL Study Investigators : Kidney function and symptom development over time in elderly patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: Results of the EQUAL cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 36: 862–870, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ERA-EDTA Registry : ERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report 2017. Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Department of Medical Informatics, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuhara S, Lopes AA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Kurokawa K, Mapes DL, Akizawa T, Bommer J, Canaud BJ, Port FK, Held PJ; Worldwide Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study : Health-related quality of life among dialysis patients on three continents: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int 64: 1903–1910, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goto NA, van Loon IN, Boereboom FTJ, Emmelot-Vonk MH, Willems HC, Bots ML, Gamadia LE, van Bommel EFH, Van de Ven PJG, Douma CE, Vincent HH, Schrama YC, Lips J, Hoogeveen EK, Siezenga MA, Abrahams AC, Verhaar MC, Hamaker ME: Association of initiation of maintenance dialysis with functional status and caregiver burden. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1039–1047, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesnaye NC, Meuleman Y, de Rooij ENM, Hoogeveen EK, Dekker FW, Evans M, Pagels AA, Caskey FJ, Torino C, Porto G, Szymczak M, Drechsler C, Wanner C, Jager KJ; EQUAL Study Investigators : Health-related quality-of-life trajectories over time in older men and women with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 205–214, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CT, Blankestijn PJ, Dember LM, Gallieni M, Harris DCH, Lok CE, Mehrotra R, Stevens PE, Wang AY, Cheung M, Wheeler DC, Winkelmayer WC, Pollock CA; Conference Participants : Dialysis initiation, modality choice, access, and prescription: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 96: 37–47, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lockwood MB, Rhee CM, Tantisattamo E, Andreoli S, Balducci A, Laffin P, Harris T, Knight R, Kumaraswami L, Liakopoulos V, Lui SF, Kumar S, Ng M, Saadi G, Ulasi I, Tong A, Li PK: Patient-centred approaches for the management of unpleasant symptoms in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 18: 185–198, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massy ZA, Chesnaye NC, Larabi IA, Dekker FW, Evans M, Caskey FJ, Torino C, Porto G, Szymczak M, Drechsler C, Wanner C, Jager KJ, Alvarez JC; EQUAL study Investigators : The relationship between uremic toxins and symptoms in older men and women with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J 15: 798–807, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer TW, Hostetter TH: Uremia. N Engl J Med 357: 1316–1325, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowenstein J, Grantham JJ: Residual renal function: A paradigm shift. Kidney Int 91: 561–565, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Kader K: Symptoms with or because of kidney failure? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 475–477, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Rooij ENM, Meuleman Y, de Fijter JW, Le Cessie S, Jager KJ, Chesnaye NC, Evans M, Pagels AA, Caskey FJ, Torino C, Porto G, Szymczak M, Drechsler C, Wanner C, Dekker FW, Hoogeveen EK; EQUAL Study Investigators : Quality of life before and after the start of dialysis in older patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1159–1167, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jager KJ, Ocak G, Drechsler C, Caskey FJ, Evans M, Postorino M, Dekker FW, Wanner C: The EQUAL study: A European study in chronic kidney disease stage 4 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: iii27–iii31, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ERA/EDTA Registry : ERA/EDTA Registry Annual Report 2009, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Academic Medical Center, Department of Medical Informatics, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Rotondi AJ, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Switzer GE: Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: The Dialysis Symptom Index. J Pain Symptom Manage 27: 226–240, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Rosati RA: Regression modelling strategies for improved prognostic prediction. Stat Med 3: 143–152, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibrahim JG, Molenberghs G: Missing data methods in longitudinal studies: A review. Test (Madr) 18: 1–43, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Haubo Bojesen Christensen R, Singmann H, Dai B, Scheipl F, Grothendieck G, Green P, Fox J, Bauer A, Krivitsky PN: Linear Mixed-Effects Models using Eigen and S4 [R package LMEE4 version 1.1-30]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN), 2022. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/. Accessed October 24, 2022

- 25.Phillips A, Frank A, Loftin C, Shepherd S: A detailed review of systems: An educational feature. J Nurse Pract 13: 681–686, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Xie L, Yang J, Pang X: Symptom burden amongst patients suffering from end-stage renal disease and receiving dialysis: A literature review. Int J Nurs Sci 5: 427–431, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wulczyn KE, Zhao SH, Rhee EP, Kalim S, Shafi T: Trajectories of uremic symptom severity and kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 496–506, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor K, Chu NM, Chen X, Shi Z, Rosello E, Kunwar S, Butz P, Norman SP, Crews DC, Greenberg KI, Mathur A, Segev DL, Shafi T, McAdams-DeMarco MA: Kidney disease symptoms before and after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1083–1093, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almutary H, Bonner A, Douglas C: Symptom burden in chronic kidney disease: A review of recent literature. J Ren Care 39: 140–150, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson TJ, Nixon DGD, Palmer J, Lightfoot CJ, Smith AC: Differences in physical symptoms between those with and without kidney disease: A comparative study across disease stages in a UK population. BMC Nephrol 22: 147, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voskamp PWM, van Diepen M, Evans M, Caskey FJ, Torino C, Postorino M, Szymczak M, Klinger M, Wallquist C, van de Luijtgaarden MWM, Chesnaye NC, Wanner C, Jager KJ, Dekker FW: The impact of symptoms on health-related quality of life in elderly pre-dialysis patients: Effect and importance in the EQUAL study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 1707–1715, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Willik EM, Hemmelder MH, Bart HAJ, van Ittersum FJ, Hoogendijk-van den Akker JM, Bos WJW, Dekker FW, Meuleman Y: Routinely measuring symptom burden and health-related quality of life in dialysis patients: First results from the Dutch registry of patient-reported outcome measures. Clin Kidney J 14: 1535–1544, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davey CH, Webel AR, Sehgal AR, Voss JG, Huml A: Fatigue in individuals with end stage renal disease. Nephrol Nurs J 46: 497–508, 2019 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soykan A, Boztas H, Kutlay S, Ince E, Nergizoglu G, Dileköz AY, Berksun O: Do sexual dysfunctions get better during dialysis? Results of a six-month prospective follow-up study from Turkey. Int J Impot Res 17: 359–363, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison TG, Skrtic M, Verdin NE, Lanktree MB, Elliott MJ: Improving sexual function in people with chronic kidney disease: A narrative review of an unmet need in nephrology research. Can J Kidney Health Dis 7: 2054358120952202, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou J, Kiebalo T, Jagiello P, Pawlaczyk K: Multifaceted sexual dysfunction in dialyzing men and women: Pathophysiology, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Life (Basel) 11: 311, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindau ST, Tang H, Gomero A, Vable A, Huang ES, Drum ML, Qato DM, Chin MH: Sexuality among middle-aged and older adults with diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes: A national, population-based study. Diabetes Care 33: 2202–2210, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raheem OA, Su JJ, Wilson JR, Hsieh TC: The Association of Erectile Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Disease: A systematic critical review. Am J Men Health 11: 552–563, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rayner HC, Larkina M, Wang M, Graham-Brown M, van der Veer SN, Ecder T, Hasegawa T, Kleophas W, Bieber BA, Tentori F, Robinson BM, Pisoni RL: International comparisons of prevalence, awareness, and treatment of pruritus in people on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2000–2007, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Willik EM, Lengton R, Hemmelder MH, Hoogeveen EK, Bart HAJ, van Ittersum FJ, Ten Dam MAG, Bos WJW, Dekker FW, Meuleman Y: Itching in dialysis patients: Impact on health-related quality of life and interactions with sleep problems and psychological symptoms–Results from the RENINE/PROMs registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 37: 1731–1741, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong JH, Davies MRP, Mount PF: Relationship between residual kidney function and symptom burden in haemodialysis patients. Intern Med J 51: 52–61, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosa AA, Fryd DS, Kjellstrand CM: Dialysis symptoms and stabilization in long-term dialysis. Practical application of the CUSUM plot. Arch Intern Med 140: 804–807, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henry SL, Munoz-Plaza C, Garcia Delgadillo J, Mihara NK, Rutkowski MP: Patient perspectives on the optimal start of renal replacement therapy. J Ren Care 43: 143–155, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hovstadius B, Petersson G: Factors leading to excessive polypharmacy. Clin Geriatr Med 28: 159–172, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jawed A, Moe SM, Moorthi RN, Torke AM, Eadon MT: Increasing nephrologist awareness of symptom burden in older hospitalized end-stage renal disease patients. Am J Nephrol 51: 11–16, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nair D, Wilson FP: Patient-reported outcome measures for adults with kidney disease: Current measures, ongoing initiatives, and future opportunities for incorporation into patient-centered kidney care. Am J Kidney Dis 74: 791–802, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ: Regression to the mean: What it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol 34: 215–220, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Willik EM, Terwee CB, Bos WJW, Hemmelder MH, Jager KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Meuleman Y: Patient-reported outcome measures ( PROMs): Making sense of individual PROM scores and changes in PROM scores over time. Nephrology (Carlton) 26: 391–399, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weisbord SD, Bossola M, Fried LF, Giungi S, Tazza L, Palevsky PM, Arnold RM, Luciani G, Kimmel PL: Cultural comparison of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Hemodial Int 12: 434–440, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.ERA Registry : ERA Registry Annual Report 2019. Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Department of Medical Informatics, 2021 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.