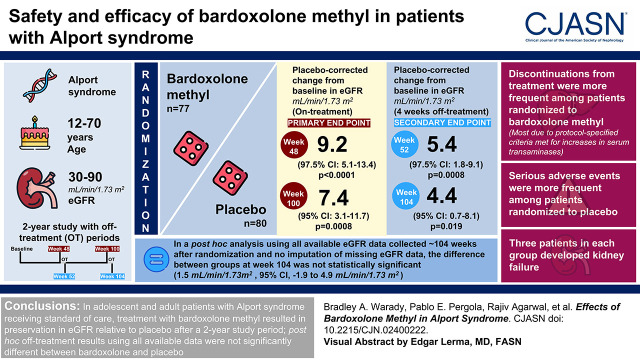

Visual Abstract

Keywords: Alport syndrome, bardoxolone methyl, CKD

Abstract

Background and objectives

Alport syndrome is an inherited disease characterized by progressive loss of kidney function. We aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of bardoxolone methyl in patients with Alport syndrome.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We randomly assigned patients with Alport syndrome, ages 12–70 years and eGFR 30–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, to bardoxolone methyl (n=77) or placebo (n=80). Primary efficacy end points were change from baseline in eGFR at weeks 48 and 100. Key secondary efficacy end points were change from baseline in eGFR at weeks 52 and 104, after an intended 4 weeks off treatment. Safety was assessed by monitoring for adverse events and change from baseline in vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiograms, laboratory measurements (including, but not limited to, aminotransferases, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, magnesium, and B-type natriuretic peptide), and body weight.

Results

Patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl experienced preservation in eGFR relative to placebo at 48 and 100 weeks (between-group differences: 9.2 [97.5% confidence interval, 5.1 to 13.4; P<0.001] and 7.4 [95% confidence interval, 3.1 to 11.7; P=0.0008] ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively). After a 4-week off-treatment period, corresponding mean differences in eGFR were 5.4 (97.5% confidence interval, 1.8 to 9.1; P<0.001) and 4.4 (95% confidence interval, 0.7 to 8.1; P=0.02) ml/min per 1.73 m2 at 52 and 104 weeks, respectively. In a post hoc analysis with no imputation of missing eGFR data, the difference at week 104 was not statistically significant (1.5 [95% confidence interval, −1.9 to 4.9] ml/min per 1.73 m2). Discontinuations from treatment were more frequent among patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl; most discontinuations were due to protocol-specified criteria being met for increases in serum transaminases. Serious adverse events were more frequent among patients randomized to placebo. Three patients in each group developed kidney failure.

Conclusions

In adolescent and adult patients with Alport syndrome receiving standard of care, treatment with bardoxolone methyl resulted in preservation in eGFR relative to placebo after a 2-year study period; off-treatment results using all available data were not significantly different.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number:

A Phase 2/3 Trial of the Efficacy and Safety of Bardoxolone Methyl in Patients with Alport Syndrome - CARDINAL (CARDINAL), NCT03019185

Introduction

Alport syndrome is an inherited kidney disease characterized by abnormalities in type IV collagen. Mutations in COL4A3, COL4A4, or COL4A5 genes result in defective type IV collagen and splitting in the glomerular basement membrane, resulting in podocyte effacement, glomerulosclerosis, and loss of kidney function that often progresses to kidney failure (1). In untreated male patients with X-linked Alport syndrome, the median age at onset of kidney failure is 25 years, with an incidence of 90% by 40 years, and nearly 100% by 60 years (2). The risk of kidney failure in patients with autosomal dominant and female patients with X-linked Alport syndrome can be as high as 20% and 25%, respectively (3,4).

In patients with Alport syndrome and proteinuria, current management recommendations include treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (5,6). Despite the use of these agents, which slow disease progression, patients with Alport syndrome may still experience rapid disease progression and endure a high lifetime risk for kidney failure (7).

Bardoxolone methyl activates NF erythroid 2-like 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor modulating the expression of genes involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular energy metabolism (8–10). Bardoxolone methyl analogues in animal models suppress inflammation-mediated remodeling and fibrosis of the kidney, suppressive effects attenuating GFR loss over time (11,12). In clinical trials that, in aggregate, have enrolled 3138 patients with CKD, bardoxolone methyl has preserved kidney function, as assessed by either inulin clearance, creatinine clearance, or eGFR (13–16). The CARDINAL study evaluated the safety and efficacy of bardoxolone methyl in adolescent and adult patients with Alport syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Oversight

CARDINAL was an international, multicenter, phase 2/3 trial. The phase 2 trial was open label and the phase 3 trial was double blind, randomized, and placebo controlled. Results of the CARDINAL phase 3 trial are discussed herein. Trial design and baseline characteristics of participants have been previously described (17).

An independent data monitoring committee reviewed interim safety data approximately every 3 months or upon request. An independent statistical group (Statistics Collaborative, Washington, DC) provided support to the independent data monitoring committee. The trial was approved by the institutional review boards at participating study sites and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Population

The study included patients aged 12–70 years with histologic or genetic confirmation of Alport syndrome, eGFR of 30–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) of ≤3500 mg/g. Maximally tolerated labeled doses of an ACE inhibitor or ARB were required unless medically contraindicated. Patients with clinically significant cardiovascular disease or B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels >200 pg/ml during screening were excluded from trial participation. Additional eligibility criteria are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Randomization and Masking

Randomization was stratified by baseline UACR (≤300 mg/g, >300 to ≤1000 mg/g, and >1000 to ≤3500 mg/g), 1:1 to bardoxolone methyl or placebo. The sponsor, investigators, and trial participants were unaware of group assignments.

A prespecified data access plan ensured that blinding was maintained in the second year of the trial for all patients and individuals involved with conduct of the trial after analysis of outcomes at 48 and 52 weeks.

Intervention

Adult patients started once-daily dosing by receiving 5 mg and increased the dose every 2 weeks to their target dose of 20 or 30 mg (the latter for patients with baseline UACR of >300 mg/g). Patients <18 years of age started dosing by receiving 5 mg every other day during the first week, 5 mg daily during the second week, and then increased the dose every 2 weeks according to the dose-titration scheme noted above for adults. Patients did not receive study drug during a 4-week withdrawal period between week 48 and week 52, after which treatment was restarted at the same dose received at week 48 and continued through 100 weeks. Patients were to be reassessed after a second 4-week withdrawal period at 104 weeks to evaluate potential retained off-treatment benefit of bardoxolone methyl measured as eGFR. Supplemental Figure 1 depicts the dose-titration scheme and schedule of assessments.

Outcomes

Primary efficacy end points were the change from baseline eGFR by randomized group after 48 and 100 weeks of treatment. We calculated eGFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration 2009 equation for adult patients or the bedside Schwartz equation throughout the entirety of the trial for patients <18 years at the time of consent. Key secondary efficacy end points were the change from baseline eGFR by randomized group at 52 and 104 weeks, corresponding to 4 weeks after the last administration of study drug. Exploratory end points are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Safety was assessed through week 104. Safety assessments included the frequency and intensity of adverse events, and the investigator’s assessment of relatedness to study drug, along with change from baseline in vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiograms, laboratory measurements (including, but not limited to, aminotransferases, UACR, magnesium, and BNP), and body weight.

Statistical Analyses

Power Calculation.

We calculated that enrollment of 150 patients would provide approximately 80% power to test the primary hypotheses, assuming a between-group difference at 48 and 100 weeks in change from baseline eGFR of 3.1 ml/min per 1.73 m2. The estimate for the between-group difference was derived from phase 2 study results in 30 patients with Alport syndrome. Our calculation assumed a two-sided type 1 error rate of 0.05, and SD of 8 ml/min per 1.73 m2. We split the total significance level (0.05) between the end points assessed in the first and second years of the trial as a strategy to reserve α to test the year 2 results if the year 1 testing sequence was not statistically significant (18). If there was a significant treatment effect for both year 1 end points, then the significance level for year 1 (0.025) remained available to be carried forward to the year 2 testing sequence. Thus, if both year 1 end points were significant, the year 2 testing sequence was tested using a significance level of 0.05.

Primary End Points.

We used a mixed model repeated measures approach to analyze the primary end points, with eGFR through 48 or 100 weeks as the response, with baseline eGFR, baseline UACR strata, and geographic location (United States, yes/no; week 100 only) as covariates and the following fixed factors: treatment group, time, interaction between treatment group and time, and interaction between baseline eGFR and time. The model included all measurements collected through 48 or 100 weeks, irrespective of study drug administration (i.e., intention-to-treat principle). Missing data were not imputed, and off-treatment eGFR determinations at 52 and 104 weeks were not included in the mixed model repeated measures analyses.

Key Secondary End Points.

For key secondary end points, we compared changes from baseline in eGFR at 52 and 104 weeks (or 4 weeks after last dose for patients who discontinued study drug) using analysis of covariance, with baseline eGFR, randomized UACR strata, and geographic location (United States, yes/no; week 104 only) as covariates and treatment group as the fixed effect. We imputed missing eGFR data at 52 or 104 weeks, including data among patients who progressed to kidney failure, using multiple imputation on the basis of the randomized treatment group with adjustments for baseline eGFR and randomized UACR. Analysis of week 52 results included eGFR values that were 14–35 days after the last dose in the first year of treatment. Analysis of week 104 results included eGFR values that were ≥14 days and closest to 28 days after the last dose in the second year of treatment. We conducted an additional post hoc analysis using all available eGFR data. Additional details of patients with off-treatment eGFR values outside the specified visit windows are provided in Supplemental Figure 2.

Tipping Point Sensitivity Analysis.

We conducted a tipping point analysis using treatment-based multiple imputation to determine the extent to which the eGFR of patients with missing data would have to have changed to render the primary end point nonsignificant.

Control-Based Sensitivity Analysis.

We conducted sensitivity analyses using control-based multiple imputation to examine the robustness of the week 100 and week 104 end point findings when missing data were assumed to be missing not at random. We adjusted multiple imputation for baseline eGFR and randomized UACR strata.

We conducted statistical analyses with SAS software, version 9.3 (or higher). Additional details, including analysis of exploratory outcomes and sensitivity analyses, are provided in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

Results

Patients

Between July 2017 and November 2018, we screened 371 and randomized 157 patients at 48 sites in the United States, Europe, Japan, and Australia. Supplemental Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 4 detail the disposition of trial participants.

Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two treatment groups (Table 1). A total of 23 patients <18 years of age were enrolled into the trial. Mean baseline eGFR was 63 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for both groups. Geometric mean baseline UACR was 148 and 134 mg/g for the bardoxolone methyl and placebo groups, respectively. Most of the patients (81% in the bardoxolone methyl group and 75% in the placebo group) were receiving an ACE inhibitor or ARB; all but one of these patients, in the bardoxolone methyl group, received an ACE inhibitor or ARB at the maximum tolerated dose as determined clinically by their provider.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients in the intention-to-treat population

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=80) | Bardoxolone Methyl (n=77) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 40 (16) | 39 (15) |

| Age <18 years, n (%) | 12 (15) | 11 (14) |

| Female, n (%) | 48 (60) | 43 (56) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Asian | 12 (15) | 14 (18) |

| Black or African American | 2 (3) | 3 (4) |

| White | 63 (79) | 55 (71) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Other | 2 (3) | 4 (5) |

| Hispanic or Latino, n (%) | 10 (13) | 9 (12) |

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2), mean (SD); range (min–max) | 63 (18); 28–91 | 63 (18); 30–97 |

| eGFR category, n (%) | ||

| ≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 33 (41) | 33 (43) |

| >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 47 (59) | 44 (57) |

| Baseline UACR (mg/g), geometric mean (SEM) | 134 (33) | 148 (34) |

| Baseline UACR ≤300 mg/g, n (%) | 43 (54) | 42 (55) |

| Baseline UACR >300 mg/g, n (%) | 37 (46) | 35 (46) |

| Baseline hematuria present, n (%) | 68 (85) | 67 (87) |

| Hearing loss (yes), n (%) | 34 (43) | 36 (47) |

| Visual impairment (yes), n (%) | 19 (24) | 18 (23) |

| Age at diagnosis (yr), mean (SD) | 30 (19) | 30 (17) |

| Histologic diagnosis (yes), n (%) | 15 (19) | 17 (22) |

| Genetic diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| X-linked AS subtype | 51 (64) | 47 (61) |

| Males with X-linked AS subtype | 21 (26) | 23 (30) |

| Females with X-linked AS subtype | 30 (38) | 24 (31) |

| Non–X-linked AS subtype | 24 (30) | 24 (31) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB use (yes), n (%) | 60 (75) | 62 (81) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26 (6) | 27 (6) |

min, minimum; max, maximum; UACR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio; AS, Alport syndrome; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker.

Drug Exposure

A total of 51 (66%) patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl and 67 (84%) patients randomized to placebo completed treatment through 100 weeks. The median (interquartile range) duration of exposure was 671 (428–674) days (96 weeks) among patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl and 672 (669–675) days (96 weeks) among patients randomized to placebo. Study drug was discontinued more frequently in the bardoxolone methyl group due to protocol-specified criteria (the majority of which were related to aminotransferases increases; Supplemental Table 5) or adverse events (Supplemental Table 6), primarily during the first year of the trial. Of the randomized patients, 98% completed safety follow-up through 104 weeks, and 72 (94%) patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl and 78 (98%) patients randomized to placebo had eGFR values collected approximately 104 weeks after randomization (Supplemental Table 4).

Primary and Key Secondary End Points

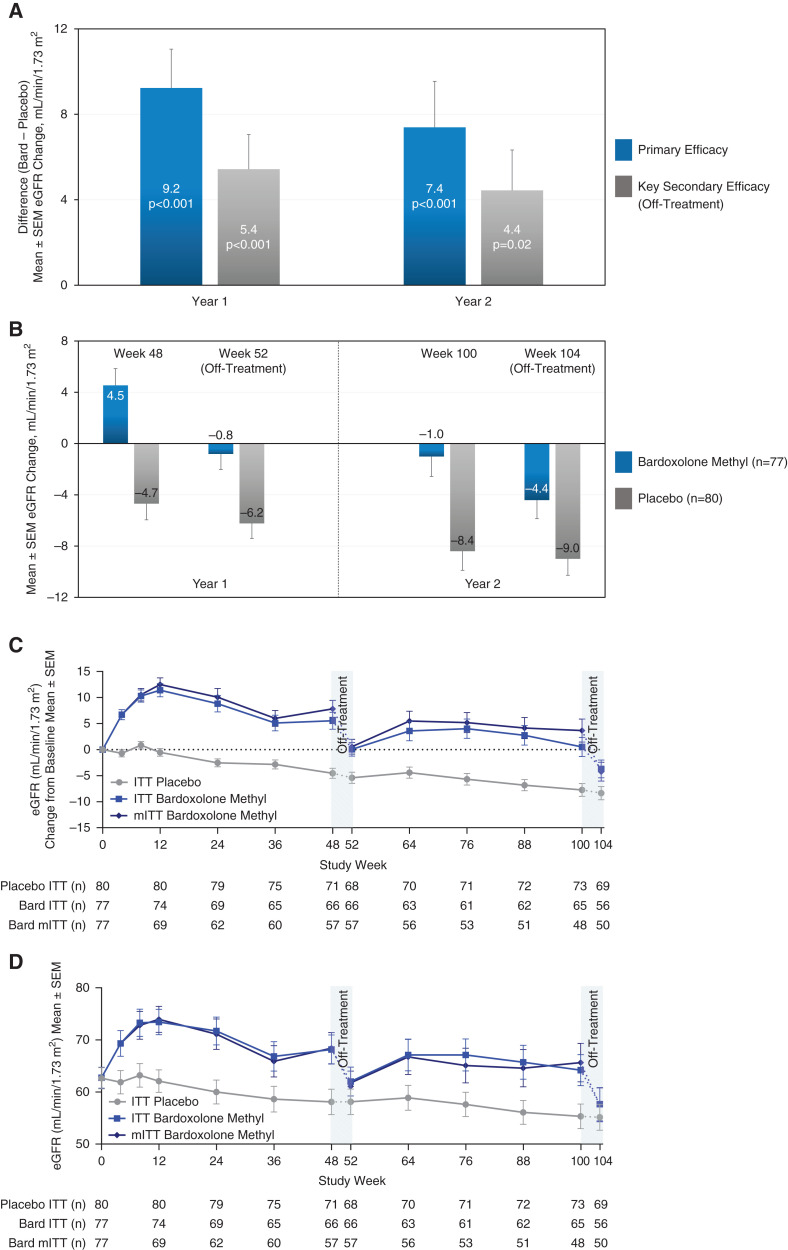

Patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl experienced preservation in mean eGFR relative to placebo at 48 weeks, 9.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (97.5% confidence interval [CI], 5.1 to 13.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P<0.001), that was retained at 100 weeks (7.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, 3.1 to 11.7 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P<0.001; Figure 1A). Corresponding mean eGFR changes from baseline at 100 weeks were −1.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −4.1 to 2.1 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and −8.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −11.3 to −5.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2) for patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl and placebo, respectively (Figure 1B). Figure 1C shows the trajectory of changes in eGFR over time (absolute eGFR values are shown in Figure 1D). Three participants in each randomized group developed kidney failure during the trial.

Figure 1.

Primary and key secondary efficacy results from CARDINAL (intention-to-treat population). (A) Mean difference between treatment groups for the primary end point, changes from baseline in eGFR at 48 weeks (year 1) and 100 weeks (year 2), and for the key secondary end point, off-treatment changes from baseline in eGFR at 52 weeks (year 1) and 104 weeks (year 2). The primary end point was analyzed using mixed model repeated measures. The model included all available eGFR values collected through week 100 (excluding week 52) for the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (n=157, with n=80 for placebo and n=77 for bardoxolone methyl). eGFR data were available for 71 patients randomized to placebo and 66 patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (bard) at 48 weeks, and for 73 patients randomized to placebo and 65 patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl at 100 weeks, and missing data were not imputed. We assessed key secondary end points 4 weeks after last dose in year 1 at 52 weeks and in year 2 at 104 weeks and analyzed using analysis of covariance for the ITT population (n=157, with n=80 for placebo and n=77 for bardoxolone methyl). Off-treatment eGFR data (collected 4 weeks after last dose) were available for 68 patients randomized to placebo and 66 patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl at 52 weeks, and for 69 patients randomized to placebo and 56 patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl at 104 weeks. For the key secondary end points, we imputed missing data using multiple imputation on the basis of the randomized treatment group. (B) Mean changes from baseline in patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (n=77) and placebo (n=80) contributing to primary (at 48 and 100 weeks) and key secondary (at 52 and 104 weeks) efficacy analyses. (C) Observed mean (±SEM) change from year 1 baseline (i.e., before starting intervention) in eGFR for the ITT population and the modified ITT population (mITT) through the 104 weeks of the study. The mITT analysis assesses the effect of receiving study drug in the ITT population and excludes any eGFR values collected after final dose (detailed in Supplemental Table 3). Off-treatment periods are represented by the dash and only include eGFR data collected 4 weeks after last dose. Additional eGFR values, collected approximately 104 weeks after randomization, irrespective of time off study drug, were available for a total of 78 patients randomized to placebo and 72 patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (Table 2). (D) Observed mean (±SEM) eGFR values for the ITT population and the mITT population through the 104 weeks of the study. The mITT analysis assesses the effect of receiving study drug in the ITT population and excludes any eGFR values collected after final dose. Off-treatment periods are represented by the dash.

Key secondary analyses, which analyzed the 4-week off-treatment change from baseline in eGFR, demonstrated preservation in mean eGFR (off treatment) relative to placebo at 52 weeks, 5.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (97.5% CI, 1.8 to 9.1 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P<0.001), that was largely retained at 104 weeks, 4.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 0.7 to 8.1 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P=0.02; Figure 1, A and B).

We conducted a post hoc analysis using all available eGFR data collected approximately 104 weeks after randomization. The average (±SD) time off treatment for the patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (n=72) at the time the off-treatment eGFR was collected was 23 (±37) weeks. This included 14 patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl who discontinued study drug administration before 48 weeks of treatment; the average (±SD) time off treatment for these patients was 90 (±27) weeks. Results of this analysis did not achieve statistical significance (1.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, −1.9 to 4.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2; Table 2). Table 2 shows additional post hoc analyses.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis for primary and key secondary end points

| Sensitivity Analysis | Mean±SEM eGFR Change (ml/min per 1.73 m2) (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=80) | Bardoxolone Methyl (n=77) | Difference between Treatment Groups | ||

| Year 2 primary end point (week 100 eGFR change) | ||||

| Control-based multiple imputation | −8.5±1.5 (−11.4 to −5.6) | −1.4±1.6 (−4.5 to 1.7) | 7.1±2.1 (2.9 to 11.3) | 0.001 |

| Tipping point analysis: bardoxolone week 100 shift=–22 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −8.5±1.7 (−11.7 to −5.3) | −3.8±1.7 (−7.2 to −0.4) | 4.7±2.4 (0.0 to 9.4) | 0.05 |

| Year 2 key secondary end point (week 104 eGFR change) | ||||

| Control-based multiple imputation | −10.8±1.3 (−13.4 to −8.2) | −7.8±1.4 (−10.6 to −5.0) | 3.0±1.8 (−0.5 to 6.4) | 0.09 |

| Post hoc analysis using all available eGFR values collected approximately 104 weeks after randomization | −10.4±1.3 (−13.0 to −7.9) | −8.9±1.3 (−11.6 to −6.3) | 1.5±1.7 (−1.9 to 4.9) | 0.38 |

| Post hoc imputation for patients progressing to kidney failure | ||||

| Week 104 eGFR=5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −11.5±1.3 (−14.2 to −8.9) | −7.1±1.5 (−10.1 to −4.1) | 4.4±1.9 (0.7 to 8.2) | 0.02 |

| Week 104 eGFR=0 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −11.8±1.4 (−14.5 to −9.1) | −7.4±1.6 (−10.5 to −4.3) | 4.4±2.0 (0.5 to 8.3) | 0.03 |

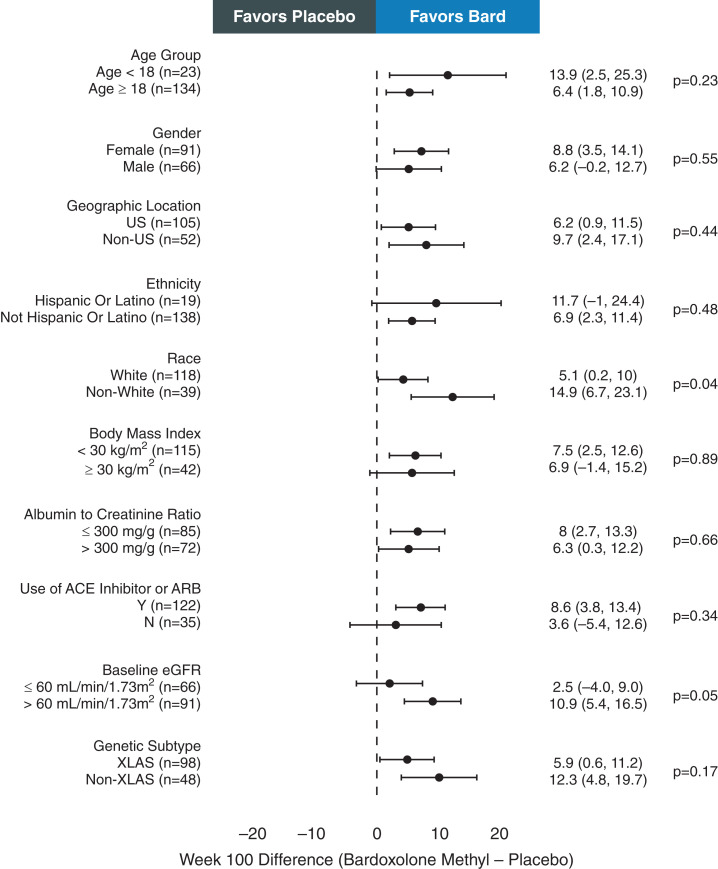

The effects of bardoxolone methyl on eGFR were similar across most prespecified subgroups. Noteworthy were the differences in eGFR between treatment groups in the adolescent subpopulation, who are often at highest risk for progression to kidney failure (17): 13.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 2.5 to 25.3 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P=0.02) and 14.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 4.7 to 24.3 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P=0.004) at 100 and 104 weeks, respectively (Figure 2). Similar results were observed at week 48 (Supplemental Figure 3). As shown in Figure 2, at week 100, the difference between treatment groups in eGFR change from baseline for patients receiving ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy was 8.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 3.8 to 13.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P<0.001), which was larger than the difference between treatment groups for patients not receiving an ACE inhibitor or ARB (3.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, −5.4 to 12.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P=0.43). In addition, at week 100, the difference between treatment groups in eGFR change from baseline for patients with baseline eGFR >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was 10.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 5.4 to 16.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P<0.001), which was larger than the difference between treatment groups for patients with baseline eGFR ≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (2.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, −4.0 to 9.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P=0.45). Similar results were observed at week 48 as it relates to ACE inhibitor or ARB use but, in subpopulations with baseline eGFR >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and baseline eGFR ≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, similar improvements in eGFR were observed at week 48 (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of eGFR change from baseline to week 100 by subgroups. Forest plot summarizing mean±95% confidence interval difference between bardoxolone methyl (bard) and placebo groups in the change from baseline in eGFR at 100 weeks for subgroups on the basis of baseline characteristics at randomization. Mean difference between treatment groups at 100 weeks was analyzed for each subgroup using mixed model repeated measures and included all available eGFR values collected through week 100 for the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, with the number of patients contributing to the analysis for each subgroup noted in the figure and the P value indicating the difference between subgroups. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; N, no; US, United States; XLAS, X-linked Alport syndrome; Y, yes.

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses for the efficacy end points are presented in Table 2. Tipping point analyses showed that missing eGFR values in the bardoxolone methyl group would have to be 22 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower than observed values for the trial to lose statistical significance at 100 weeks (4.7 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, 0.0 to 9.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2; Table 2).

A control-based multiple imputation analysis indicated that, when missing week 104 eGFR values for patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl were imputed on the basis of observed placebo week 104 eGFR results, the 4-week off-treatment effect favored bardoxolone methyl but was not statistically significant (3.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, −0.5 to 6.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2; Table 2).

Overall Safety

Serious adverse events occurred less frequently in the bardoxolone methyl group than in the placebo group (12 events in eight patients versus 19 events in 15 patients; Supplemental Table 7). Table 3 shows the most commonly reported adverse events; most were mild to moderate in severity. Supplemental Table 8 shows all reported adverse events by system organ class. Ten (13%) patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl and four (5%) randomized to placebo discontinued treatment early because of an adverse event.

Table 3.

Summary of treatment-emergent adverse events

| Adverse Event | Placebo (n=80) | Bardoxolone Methyl (n=77) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with SAE, n (%) | 15 (19) | 8 (10) |

| Patients with AE, n (%) | 77 (96) | 75 (97) |

| Discontinuations due to AE, n (%) | 4 (5) | 10 (13) |

| AEs reported in >10% of patients in either treatment group, n (%) | ||

| Muscle spasms | 27 (34) | 38 (49) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 2 (3) | 36 (47) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 1 (1) | 19 (25) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 24 (30) | 18 (23) |

| Headache | 16 (20) | 16 (21) |

| Fatigue | 12 (15) | 14 (18) |

| Nausea | 11 (14) | 13 (17) |

| Peripheral edema | 11 (14) | 12 (16) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (8) | 12 (16) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 8 (10) | 12 (16) |

| Hyperkalemia | 5 (6) | 11 (14) |

| B-type natriuretic peptide increased | 3 (4) | 11 (14) |

| Weight decreased | 1 (1) | 10 (13) |

| Back pain | 13 (16) | 9 (12) |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (16) | 8 (10) |

| Proteinuria | 7 (9) | 8 (10) |

| Urine albumin-creatinine ratio increased | 7 (9) | 8 (10) |

| Cough | 3 (4) | 8 (10) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 9 (11) | 5 (7) |

| Dizziness | 12 (15) | 3 (4) |

SAE, serious adverse event; AE, adverse event.

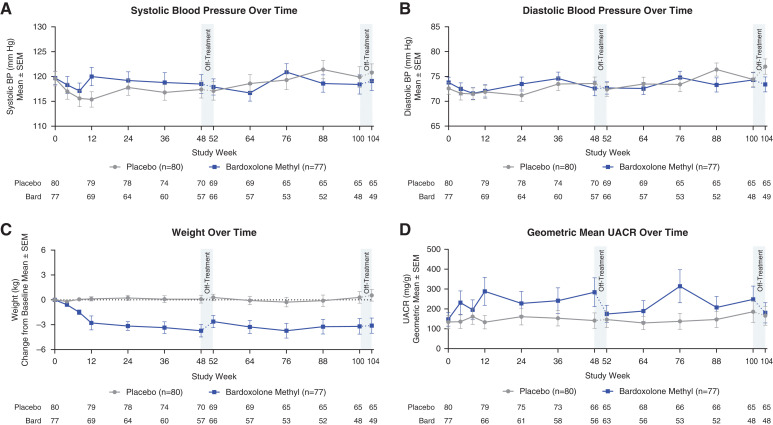

There were no significant changes in mean systolic and diastolic BP in patients treated with bardoxolone methyl relative to baseline and relative to patients receiving placebo (Figure 3, A and B). Patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl experienced weight loss relative to baseline and relative to patients receiving placebo at 100 weeks (Figure 3C), which was generally more pronounced in patients with baseline body mass index >30 kg/m2 (Supplemental Figure 4A). UACR initially increased with bardoxolone methyl, but decreased after stopping study drug (Figure 3D). When indexed to eGFR, UACR was generally lower in patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl relative to placebo (Supplemental Figure 5A).

Figure 3.

Safety parameters over time. (A and B) Mean (±SEM) systolic and diastolic BP for patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (bard; n=77) or placebo (n=80) through the 104 weeks of the study. Data collected during the on-treatment period are represented by the solid line, and off-treatment data are represented by the dashed line. Mean values at 52 and 104 weeks include data collected 28 days after last dose for patients that discontinued early in the first or second year of treatment, respectively. (C) Mean (±SEM) change from baseline in weight for patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (n=77) and patients randomized placebo (n=80) through 104 weeks. Data collected during the on-treatment period are represented by the solid line, and off-treatment data are represented by the dashed line. Mean values at 52 and 104 weeks include data collected 28 days after last dose for patients that discontinued early in the first or second year of treatment, respectively. (D) Geometric mean (±SEM) urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) for patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (n=77) and patients randomized to placebo (n=80) through 104 weeks. Data collected during the on-treatment period are represented by the solid line, and off-treatment data are represented by the interrupted line. Mean values at 52 and 104 weeks include data collected 28 days after last dose for patients that discontinued early in the first or second year of treatment, respectively.

There were transient, reversible increases in mean serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase concentrations in patients treated with bardoxolone methyl (Supplemental Figure 6). Although nearly all (70 of 77) patients treated with bardoxolone methyl had ALT increases above the upper limit of the population reference range during the trial, mean ALT concentrations returned to baseline at week 52 and again at week 104, after study drug had been stopped for 4 weeks. Increases in aminotransferases were not associated with increases in total bilirubin and no Hy law cases were reported. Other physiologic and laboratory variables are summarized in Supplemental Table 9 and Supplemental Figure 8.

Safety in Adolescents

A generally favorable safety profile was observed in adolescent patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl; no serious adverse events or adverse events leading to permanent treatment discontinuation occurred in the bardoxolone methyl group. Mean changes in body weight were modest (Supplemental Figure 4B); adolescent patients treated with bardoxolone methyl generally continued along their growth curves for height and weight (Supplemental Figure 7). Geometric mean UACR did not change significantly over time in adolescent patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl (Supplemental Figure 5B).

Discussion

Results from this phase 3, placebo-controlled trial in patients with Alport syndrome show that treatment with bardoxolone methyl for 48 and 100 weeks was safe and preserved kidney function over 2 years. The time course of mean eGFR showed that increases were apparent by 4 weeks.

Patients randomized to placebo experienced a decrease from baseline in eGFR during the trial. The decline in kidney function observed in the placebo arm was more rapid than that reported in other forms of CKD, including diabetic kidney disease, hypertensive CKD, and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (19–21) and consistent with historical eGFR data collected before starting the trial (17).

A statistically significant difference between treatment groups was also observed at 52 and 104 weeks after a 4-week off-treatment period. Because >99% of drug is cleared within 14 days, the 4-week off-treatment period allowed for resolution of acute pharmacodynamic effects and was appropriate for characterizing bardoxolone methyl’s effects on disease progression, in accordance with the National Kidney Foundation (NKF)–Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–European Medicines Agency Scientific Working group recommendations (22). However, a post hoc analysis of the difference between treatment groups at week 104, using all available eGFR data, did not achieve statistical significance.

The safety profile of bardoxolone methyl was generally consistent with that observed in prior trials (13,14). Several common adverse events are hypothesized to be related to the pharmacologic effects of bardoxolone methyl. Aminotransferase elevations observed with bardoxolone methyl are believed to be associated with Nrf2 activation and resulting increases in glutathione biosynthesis and mitochondrial energy metabolism (23). Nevertheless, additional data are needed to determine longer-term hepatic safety with bardoxolone methyl. The observed decreases in body weight may be explained by Nrf2-dependent changes in lipid metabolism, fatty acid oxidation, and glycemic control that have been observed in animal studies with bardoxolone methyl and analogues (24–26). Increased glomerular filtration and an associated decreased tubular reabsorption of albumin (due to an increased rate of tubular transit), accompanied by downregulation of megalin, may explain the reversible increases in UACR observed in patients treated with bardoxolone methyl in this trial and in prior studies (14,15,27,28).

CARDINAL excluded patients with a history of heart failure or a baseline BNP >200 ng/ml. Despite a small numeric increase in mean BNP observed with bardoxolone methyl treatment in CARDINAL, no patients treated with bardoxolone methyl developed major cardiac events, and the number of cardiac adverse events reported by investigators was lower in patients randomized to bardoxolone methyl compared with those randomized to placebo.

Although CARDINAL is the largest, global, phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of a therapeutic agent in patients with CKD due to Alport syndrome, it has several limitations. The overall sample size of the trial was modest and had limited power to detect clinically meaningful interactions using conventional levels of statistical significance due to smaller patient numbers in certain subgroups. Discontinuations from study treatment were more frequent among patients who received bardoxolone methyl; increases in aminotransferases that were not associated with clinical evidence of liver injury constituted the bulk of the difference. Although the discontinuation rate contributed to missing data in the trial, several sensitivity analyses, including alternate imputation methods and a tipping point analysis, demonstrated missing data were unlikely to have influenced the qualitative results of the trial. Consistent with the unanimous recommendation of its advisory committee, the FDA concluded that, on the basis of currently available information, bardoxolone methyl does not have a favorable risk-benefit profile when evaluated for the treatment of patients with Alport syndrome. Nevertheless, results of the CARDINAL trial will inform the design of future studies of potential therapeutic agents for this rare disorder.

In conclusion, among adolescent and adult patients with Alport syndrome receiving standard of care, treatment with bardoxolone methyl resulted in significant preservation in eGFR relative to placebo after a 2-year study period.

Disclosures

R. Agarwal reports having consultancy agreements with Akebia, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chinook, Diamedica, Eli Lilly, Janssen Research & Development LLC, Lexicon, Merck & Co., Relypsa, Sanofi US Services Inc., Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma Ltd., and Vertex; having travel, lodging, and food paid for by Akebia Therapeutics Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim BV, Boehringer Ingelheim International GMBH, Boehringer Ingelheim International GMBH &Co.KG, Eli Lily and Company, E.R. Squibb & Sons LLC, Fresenius USA Marketing Inc., Janssen Research & Development LLC, Merck & Co, Opko Pharmaceuticals LLC, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc., Relypsa Inc., Sanofi-Aventus US LLC, Sanofi US Services Inc., and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma Ltd.; receiving honoraria from Akebia, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chinook, Diamedica, Eli Lilly, Relypsa, and Vertex; serving in advisory or leadership roles for Akebia, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chinook, Diamedica, Eli Lilly, Hypertension, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), Journal of the American Society of Hypertension, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Relypsa, Seminars in Dialysis, and Vertex; serving on steering committees for Akebia Therapeutics Inc., Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Janssen Research & Development LLC, Relypsa Inc., Sanofi-Aventus US LLC, and Sanofi US Services Inc.; serving on data safety monitoring boards for AstraZeneca AB, Chinook, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals Inc.; serving on adjudication committees for Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim International GMBH, and Janssen Research & Development LLC; receiving payment for speaking by Fresenius USA Marketing Inc.; serving on a steering committee and consulting for Reata Pharmaceuticals (including having travel, lodging, and food paid for); receiving royalties from UpToDate; and being employed by VA Medical Center. S. Andreoli reports serving in an advisory or leadership role for Journal of Renal Nutrition and Pediatric Nephrology and having consultancy agreements with Reata. G.B. Appel reports having consultancy agreements with Achillion, Alexion, Apellis, Aurinia, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chemocentryx, E. Lilly, EMD Serono, Genentech, Genzyme-Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Ionis, Mallinkrodt, Merck, Novartis, Omeros, Pfizer, Reata, Regulus, Roche, Travere Therapeutics, UpToDate, Vera Therapeutics, and Zyversa; receiving research funding from Achillion-Alexion, Apellis, Aurinia, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calliditas, Chemocentryx, EMD Serono, Equillium, Genentech-Roche, Goldfinch, Mallinkrodt, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Novartis, Reata, Retrophin, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Zyversa; serving on medical advisory boards for Alexion, Alexion-Achillion, Apellis, Aurinia, Bristol Myers Squib, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Reata, Roche, and Sanofi; receiving honoraria from Aurinia and GlaxoSmithKline; serving on speakers bureaus for Aurinia and GlaxoSmithKline (both for lectures on lupus nephritis); and receiving royalties from, and serving on the editorial board of, UpToDate. S. Bangalore reports having consultancy agreements with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Pfizer, and Reata; receiving honoraria from Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Pfizer, and Reata; serving on speakers bureaus for Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Inari, and Pfizer; receiving research funding from Abbott Vascular, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and Reata Pharmaceuticals; and serving on an advisory board for Reata Pharmaceuticals. G.A. Block reports receiving research funding from Akebia; serving in an advisory or leadership role for Ardelyx; having ownership interest in Ardelyx Inc. and US Renal Care Inc.; and being employed by US Renal Care. A.B. Chapman reports having other interests in, or relationships with, Department of Defense Review Committee and NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and Small Business Innovation Research Special Emphasis Panels and Review Panels; receiving research funding from NIDDK, Palladio, Reata, and Sanofi; serving as an external advisor for O’Brien Center Northwestern University; serving on a speakers bureau for Otsuka; receiving honoraria from Otsuka and Reata; having consultancy agreements with Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Reata, and Sanofi Pharmaceuticals; and serving on steering committees for Reata Pharmaceuticals (for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease) and Sanofi-Genzyme. G.M. Chertow reports having consultancy agreements with Akebia, Ardelyx, AstraZeneca, Cricket, DiaMedica, Gilead, Miromatrix, Reata, Sanifit, Unicycive, and Vertex; serving on steering committees for Akebia, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Sanifit, and Vertex; receiving research funding from Amgen, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and NIDDK; serving on data and safety monitoring boards for Angion, Bayer, Gilead, Mineralys, NIDDK, Palladio, and ReCor; serving on advisory boards for Ardelyx, Baxter, CloudCath, Cricket, DiaMedica, Durect, Miromatrix, and Reata Pharmaceuticals; having ownership interest in Ardelyx, CloudCath, Durect, DxNow, Eliaz Therapeutics, Outset, Physiowave, PuraCath, and Renibus; having stock options in Ardelyx, CloudCath, Durect, and Miromatrix; and serving on the Satellite Healthcare Board of Directors and as coeditor of Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney (Elsevier). M.P. Chin reports being employed by, having ownership interest in, and receiving patents or royalties from Reata Pharmaceuticals. K.L. Gibson reports receiving honoraria for the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Premeeting in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019; serving on a pediatric advisory board for Aurinia Inc., on a CKD advisory board for Reata Pharmaceuticals, and on an advisory board for Retrophin Inc.; serving as a clinical trial coinvestigator for Aurinia Inc. and Retrophin Inc.; having consultancy agreements with Aurinia Inc. and Travere Inc. (formally Retrophin); receiving research funding from Aurinia Inc. and Travere Inc.; having other interests or relationships with International Pediatric Nephrology Association Writing Group (nonpaid) and KDIGO Writing Group (nonpaid); and serving in an advisory or leadership role for Travere Inc. A. Goldsberry reports being employed by and having ownership interest in Reata Pharmaceuticals Inc. K. Iijima reports receiving research funding from Astellas Pharma Inc., Air Water Medical Inc., Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd., Eisai Co. Ltd., Enomoto-Yakuhin Co. Ltd., JCR Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Nihon Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Shionogi & Co. Ltd., and Zenyaku Kogyo Co. Ltd.; receiving honoraria from Astellas Pharma Inc., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Integrated Development Associates Co. Ltd., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., and Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Ltd.; serving on the editorial boards of CJASN and Pediatric Nephrology; having consultancy agreements with JCR Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tejin Pharma Ltd., Sanofi K.K., and Zenyaku Kogyo Co. Ltd.; and having a patent application on the development of “Antisense nucleotides for exon skipping therapy in Alport syndrome.” L.A. Inker reports serving in an advisory or leadership role for Alport’s Foundation; serving as a member of ASN, NKF, and National Kidney Disease Education Program; having consultancy agreements with Diamtrix; receiving research funding to institute for research and contracts with the NIH, NKF, Omeros, Otsuka, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Retrophin, and Travere; having consulting agreements with Omeros Corp. and Tricida Inc.; and receiving other support from Omeros Corp. and Tricida. C.E. Kashtan reports having consultancy agreements with Acceleron, Boehringer Ingelheim, BridgeBio, Daiichi Sankyo, Metis, Ono, Retrophin, and Travere; serving in an advisory or leadership role for Alport Syndrome Foundation; receiving research funding from Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research, Reata, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Travere Therapeutics; and receiving honoraria from UpToDate. B. Knebelmann reports receiving honoraria from Enyo, Reata, Sanofi, Travere, and Vertex and having consultancy agreements with Sanofi and Travere. L.H. Mariani reports receiving honoraria from ASN Board Review Course and Update, Reata Pharmaceuticals CKD Advisory Committee, Calliditas Therapeutics Advisory Board, and Travere Therapeutics Advisory Board; receiving research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, NIH-NIDDK, and Travere Therapeutics; having consultancy agreements with Calliditas Therapeutics Advisory Board, Reata Pharmaceuticals CKD Advisory Committee, and Travere Therapeutics Advisory Board; and serving in advisory or leadership roles for Calliditas Therapeutics, Reata Pharmaceuticals, and Travere Therapeutics. C.J. Meyer reports being employed by, having ownership interest in, and receiving patents or royalties from Reata Pharmaceuticals Inc. K. Nozu reports receiving lecture fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Company, Novartis pharma Co. Ltd., and Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd.; receiving research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Company, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharmaceutical Company, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Company, and Shionogi Inc.; receiving patents or royalties from Daiichi Sankyo Pharmaceutical Company; receiving consultation fees from Kyowa Kirin; serving in advisory or leadership roles for Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Company and Toa Eiyo Ltd.; and having a patent issued titled “Antisense nucleotides for exon skipping therapy in Alport syndrome.” M. O’Grady reports being employed by and having ownership interest in Reata Pharmaceuticals. P.E. Pergola reports having consultancy agreements with Akebia Therapeutics, Ardelyx, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Caladrius, Corvidia Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, Otsuka, Reata Pharmaceuticals, and Unicycive; serving as a consultant for, and on advisory boards of, Akebia, Ardelyx, Bayer, Gilead, Corvidia, Fibrogen, Tricida, and Unicycive Therapeutics; serving in an advisory or leadership role for Ardelyx and Unicycive; serving as a consultant for, and on speakers bureaus for, AstraZeneca; receiving honoraria from Reata Pharmaceuticals; being employed by Renal Associates PA; having ownership interest in Unicycive Therapeutics; and receiving research funding as principal or subinvestigator on multiple clinical trials (the contracts are with the practice, not the individual). M.N. Rheault reports performing data safety and monitoring board services for Advicenne; serving in advisory or leadership roles for Alport Syndrome Foundation Medical Advisory Board, NephJC (501c3) Board of Directors, Pediatric Nephrology Research Consortium (501c3) Steering Committee, and Women In Nephrology (501c3); receiving research funding from Chinook, Kaneka, Reata, Sanofi, and Travere; serving as a clinical trial site principal investigator for Genentech, Sanofi, and Travere trials; receiving clinical trial payments (to institution) from Reata Pharmaceuticals as site principal investigator for this study; and having consultancy agreements with Visterra. A.L. Silva reports receiving research funding from Akebia, Ardelyx, AstraZeneca, Cara, Diamedica, Gilead, Goldfinch Bio, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, OPKO Renal, ProKidney, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Travere; serving on speakers bureaus for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Aurinia, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, OPKO Renal, and Vifor; serving in advisory or leadership roles for Ardelyx, Aurinia, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, ProKidney, and Reata; and having consultancy agreements with Aurinia, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, ProKidney, Reata Pharmaceuticals. P. Stenvinkel reports serving in advisory or leadership roles for Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Fresenius Medical Care (FMC), GlaxoSmithKline, Reata, and Vifor; receiving honoraria from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baxter, FMC, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer/Bristol Square Myers (BSM); receiving research funding from AstraZeneca and Bayer; serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Baxter, FMC, GlaxoSmithKline, Reata, and Vifor; and receiving personal fees from Reata Pharmaceuticals. R. Torra reports serving as president of the scientific committee AIRG-E; having consultancy agreements with Alnylam, Amicus, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Kyowa Kirin, Otsuka, Retrophin, Sanofi, and Takeda; receiving honoraria from Amicus, Chiesi, Otsuka, Sanofi, and Takeda; serving on the editorial boards of Clinical Kidney Journal and Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases; and serving as a member of the council of the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association and coordinator of WGIKD (Spanish Society of Nephrology). B.A. Warady reports having consultancy agreements with Amgen, Bayer, Lightline Medical, Reata, Relypsa, Roche, and UpToDate; receiving honoraria from Amgen, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Reata, Relypsa, and UpToDate; receiving research funding from Baxter Healthcare and grant support from the NIH; serving in advisory or leadership roles for Midwest Transplant Network Governing Board, NKF, Nephrologists Transforming Dialysis Safety, and North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies; and serving on the advisory board for Reata Pharmaceuticals.

Funding

This work was funded by Reata Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the supportive role of all CARDINAL investigators, support staff, and patients. We thank Svetlana Pitts, Shannon Rich, Suneeta Chimalapati, and Shobhana Natarajan, of Reata Pharmaceuticals, for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Bardoxolone Methyl for Alport Syndrome: Opportunities and Challenges,” on pages 1713–1715.

Author Contributions

R. Agarwal, S. Andreoli, G.B. Appel, S. Bangalore, G.A. Block, A.B. Chapman, G.M. Chertow, M.P. Chin, K.L. Gibson, A. Goldsberry, K. Iijima, L.A. Inker, C.E. Kashtan, B. Knebelmann, L.H. Mariani, C.J. Meyer, K. Nozu, M. O’Grady, P.E. Pergola, M.N. Rheault, A.L. Silva, P. Stenvinkel, and R. Torra reviewed and edited the manuscript; G.B. Appel, G.A. Block, K. Iijima, L.A. Inker, B. Knebelmann, K. Nozu, P.E. Pergola, M.N. Rheault, A.L. Silva, and R. Torra were responsible for investigation; B.A. Warady wrote the original draft; and all authors conceptualized the study.

Data Sharing Statement

Because the sponsor, Reata Pharmaceuticals Inc., remains engaged in discussions with regulatory agencies with regard to the data presented in this manuscript, these data cannot be disclosed at this time.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02400222/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Eligibility and exclusion criteria.

Supplemental Table 2. Full list of efficacy end points in CARDINAL.

Supplemental Table 3. Detailed description of CARDINAL analysis methodologies.

Supplemental Table 4. Detailed disposition and reasons for discontinuation in CARDINAL.

Supplemental Table 5. Summary of protocol-specified criteria leading to study drug discontinuation.

Supplemental Table 6. Summary of treatment-emergent adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation.

Supplemental Table 7. Treatment-emergent serious adverse events.

Supplemental Table 8. Treatment-emergent adverse events by system organ class.

Supplemental Table 9. Change from baseline in laboratory results at week 100.

Supplemental Figure 1. Study design and schema.

Supplemental Figure 2. CONSORT diagram.

Supplemental Figure 3. Forest plot of eGFR change from baseline to week 48 by subgroups.

Supplemental Figure 4. Mean changes from baseline in body weight by baseline BMI and age subgroups.

Supplemental Figure 5. Log UACR adjusted for eGFR over time for ITT population and geometric mean UACR change over time for adolescent patients and ITT patients by baseline UACR category.

Supplemental Figure 6. Laboratory evaluations related to hepatic function.

Supplemental Figure 7. Growth chart for adolescent patients.

Supplemental Figure 8. Serum magnesium over time for ITT population.

References

- 1.Kruegel J, Rubel D, Gross O: Alport syndrome--Insights from basic and clinical research. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 170–178, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jais JP, Knebelmann B, Giatras I, Marchi M, Rizzoni G, Renieri A, Weber M, Gross O, Netzer KO, Flinter F, Pirson Y, Verellen C, Wieslander J, Persson U, Tryggvason K, Martin P, Hertz JM, Schröder C, Sanak M, Krejcova S, Carvalho MF, Saus J, Antignac C, Smeets H, Gubler MC: X-linked Alport syndrome: Natural history in 195 families and genotype- phenotype correlations in males. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 649–657, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jais JP, Knebelmann B, Giatras I, De Marchi M, Rizzoni G, Renieri A, Weber M, Gross O, Netzer KO, Flinter F, Pirson Y, Dahan K, Wieslander J, Persson U, Tryggvason K, Martin P, Hertz JM, Schröder C, Sanak M, Carvalho MF, Saus J, Antignac C, Smeets H, Gubler MC: X-linked Alport syndrome: Natural history and genotype-phenotype correlations in girls and women belonging to 195 families: A “European Community Alport Syndrome Concerted Action” study. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2603–2610, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamiyoshi N, Nozu K, Fu XJ, Morisada N, Nozu Y, Ye MJ, Imafuku A, Miura K, Yamamura T, Minamikawa S, Shono A, Ninchoji T, Morioka I, Nakanishi K, Yoshikawa N, Kaito H, Iijima K: Genetic, clinical, and pathologic backgrounds of patients with autosomal dominant Alport syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1441–1449, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savige J, Gregory M, Gross O, Kashtan C, Ding J, Flinter F: Expert guidelines for the management of Alport syndrome and thin basement membrane nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 364–375, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashtan CE, Gross O: Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-An update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol 36: 711–719, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross O, Licht C, Anders HJ, Hoppe B, Beck B, Tönshoff B, Höcker B, Wygoda S, Ehrich JH, Pape L, Konrad M, Rascher W, Dötsch J, Müller-Wiefel DE, Hoyer P, Knebelmann B, Pirson Y, Grunfeld JP, Niaudet P, Cochat P, Heidet L, Lebbah S, Torra R, Friede T, Lange K, Müller GA, Weber M; Study Group Members of the Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Nephrologie : Early angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in Alport syndrome delays renal failure and improves life expectancy. Kidney Int 81: 494–501, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wardyn JD, Ponsford AH, Sanderson CM: Dissecting molecular cross-talk between Nrf2 and NF-κB response pathways. Biochem Soc Trans 43: 621–626, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi EH, Suzuki T, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Hayashi M, Sekine H, Tanaka N, Moriguchi T, Motohashi H, Nakayama K, Yamamoto M: Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun 7: 11624, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz S, Pergola PE, Zager RA, Vaziri ND: Targeting the transcription factor Nrf2 to ameliorate oxidative stress and inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 83: 1029–1041, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aminzadeh MA, Reisman SA, Vaziri ND, Shelkovnikov S, Farzaneh SH, Khazaeli M, Meyer CJ: The synthetic triterpenoid RTA dh404 (CDDO-dhTFEA) restores endothelial function impaired by reduced Nrf2 activity in chronic kidney disease. Redox Biol 1: 527–531, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagasu H, Sogawa Y, Kidokoro K, Itano S, Yamamoto T, Satoh M, Sasaki T, Suzuki T, Yamamoto M, Wigley WC, Proksch JW, Meyer CJ, Kashihara N: Bardoxolone methyl analog attenuates proteinuria-induced tubular damage by modulating mitochondrial function. FASEB J 33: 12253–12263, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nangaku M, Kanda H, Takama H, Ichikawa T, Hase H, Akizawa T: Randomized clinical trial on the effect of bardoxolone methyl on GFR in diabetic kidney disease patients (TSUBAKI Study). Kidney Int Rep 5: 879–890, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pergola PE, Raskin P, Toto RD, Meyer CJ, Huff JW, Grossman EB, Krauth M, Ruiz S, Audhya P, Christ-Schmidt H, Wittes J, Warnock DG; BEAM Study Investigators : Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 365: 327–336, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Zeeuw D, Akizawa T, Audhya P, Bakris GL, Chin M, Christ-Schmidt H, Goldsberry A, Houser M, Krauth M, Lambers Heerspink HJ, McMurray JJ, Meyer CJ, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Toto RD, Vaziri ND, Wanner C, Wittes J, Wrolstad D, Chertow GM; BEACON Trial Investigators : Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2492–2503, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin MP, Wrolstad D, Bakris GL, Chertow GM, de Zeeuw D, Goldsberry A, Linde PG, McCullough PA, McMurray JJ, Wittes J, Meyer CJ: Risk factors for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. J Card Fail 20: 953–958, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chertow GM, Appel GB, Andreoli S, Bangalore S, Block GA, Chapman AB, Chin MP, Gibson KL, Goldsberry A, Iijima K, Inker LA, Knebelmann B, Mariani LH, Meyer CJ, Nozu K, O’Grady M, Silva AL, Stenvinkel P, Torra R, Warady BA, Pergola PE: Study design and baseline characteristics of the CARDINAL trial: A phase 3 study of bardoxolone methyl in patients with Alport syndrome. Am J Nephrol 52: 180–189, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung HM, Wang SJ, O’Neill R: Statistical considerations for testing multiple endpoints in group sequential or adaptive clinical trials. J Biopharm Stat 17: 1201–1210, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, Mahaffey KW, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Barrett TD, Weidner-Wells M, Deng H, Matthews DR, Neal B: Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: Results from the CANVAS Program randomised clinical trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6: 691–704, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Perrone RD, Koch G, Ouyang J, McQuade RD, Blais JD, Czerwiec FS, Sergeyeva O; REPRISE Trial Investigators : Tolvaptan in later-stage autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 377: 1930–1942, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas-Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group : Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: Results from the AASK trial. JAMA 288: 2421–2431, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Gansevoort RT, Coresh J, Inker LA, Heerspink HL, Grams ME, Greene T, Tighiouart H, Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Sang Y, Vonesh E, Ying J, Manley T, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, Levin A, Perkovic V, Zhang L, Willis K: Change in albuminuria and GFR as end points for clinical trials in early stages of CKD: A scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation in collaboration with the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency. Am J Kidney Dis 75: 84–104, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis JH, Jadoul M, Block GA, Chin MP, Ferguson DA, Goldsberry A, Meyer CJ, O’Grady M, Pergola PE, Reisman SA, Wigley WC, Chertow GM: Effects of bardoxolone methyl on hepatic enzymes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 CKD. Clin Transl Sci 14: 299–309, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chertow GM, Appel GB, Block GA, Chin MP, Coyne DW, Goldsberry A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Meyer CJ, Molitch ME, Pergola PE, Raskin P, Silva AL, Spinowitz B, Sprague SM, Rossing P: Effects of bardoxolone methyl on body weight, waist circumference and glycemic control in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. J Diabetes Complications 32: 1113–1117, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saha PK, Reddy VT, Konopleva M, Andreeff M, Chan L: The triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic-acid methyl ester has potent anti-diabetic effects in diet-induced diabetic mice and Lepr(db/db) mice. J Biol Chem 285: 40581–40592, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin S, Wakabayashi J, Yates MS, Wakabayashi N, Dolan PM, Aja S, Liby KT, Sporn MB, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW: Role of Nrf2 in prevention of high-fat diet-induced obesity by synthetic triterpenoid CDDO-imidazolide. Eur J Pharmacol 620: 138–144, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossing P, Block GA, Chin MP, Goldsberry A, Heerspink HJL, McCullough PA, Meyer CJ, Packham D, Pergola PE, Spinowitz B, Sprague SM, Warnock DG, Chertow GM: Effect of bardoxolone methyl on the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 96: 1030–1036, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reisman SA, Chertow GM, Hebbar S, Vaziri ND, Ward KW, Meyer CJ: Bardoxolone methyl decreases megalin and activates nrf2 in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1663–1673, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.