Summary

Objective

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease with no approved disease modifying therapy. The enzyme autotaxin (ATX) converts lysophoshatidylcholine analogues to lysophosphatidic acid. Systemic inhibition of ATX reduces pain in animal models of OA; however, OA disease-modifying effects associated with ATX inhibition remain unknown. Here, we sought to determine whether local (knee joint) injection of an ATX inhibitor attenuates surgically-induced OA in mice.

Methods

ATX expression was evaluated in human knee OA cartilage. Ten-week-old mice were subjected to surgically-induced OA. ATX inhibitor (PF-8380, 2.5ng/joint) was injected intra-articularly either at three and five weeks post-surgery or at two, four, six and eight weeks post-surgery and knee joints were evaluated by histopathology and immunohistochemistry to study the expression of catabolic and cell death markers. mRNA sequencing of human OA chondrocytes treated with/without ATX inhibitor was performed to identify differentially expressed transcripts, followed by pathway enrichment analysis.

Results

ATX expression was elevated in severely degenerated cartilage compared to less degenerated human OA cartilage. In surgically-induced OA mice, intra-articular injection of ATX inhibitor at three and five weeks post-surgery partially protected knee joints from cartilage degeneration. Interestingly, earlier and more frequent ATX inhibitor injections did not confer significant protection. Immunohistochemical analysis showed decreased expression of catabolic and apoptotic markers with two ATX inhibitor injections. mRNA sequencing followed by pathway analysis identified pathways related to cholesterol analogue metabolism and cell-cycle that could be modulated by ATX inhibition in human OA chondrocytes.

Conclusion

Local delivery of ATX inhibitor partially attenuates surgically-induced OA in mice.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Autotaxin, Cartilage, Synovium

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive joint disease associated with loss of articular cartilage and synovitis [1]. It is estimated that 250 million people worldwide are affected by OA and the prevalence of this disease is increasing [2]. Thus, there is a substantial need to find disease modifying drugs for the treatment of OA. Autotaxin (ATX) (also known as ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodieterase [ENPP]-2) is a 125 kDa glycoprotein that acts as the key enzyme to generate lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), an inflammatory mediator, through its lysophospholipase D (lyso-PLD) activity [3]. Levels of ATX in plasma and synovial fluid correlate with OA disease severity whereas expression levels of ATX in synovial fibroblasts correlate with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) disease pathology [4,5]. Consistent with its inflammatory contribution, conditional ablation of ATX in mesenchymal cells (including synovial fibroblasts) attenuates collagen induced arthritis in mice [5]. Inhibition of ATX also reduces pain in rat models of OA [6]; however, to the best of our knowledge, the OA disease-modifying capabilities of inhibiting ATX, in particular as it relates to articular cartilage degeneration and synovitis in knee joints, is largely unknown. The aim of our study was to determine if local pharmacological inhibition of ATX can attenuate knee joint pathogenesis in a surgically-induced OA mouse model.

2. Methods

2.1. Animal study design and treatment

Right knees of 10-week-old C57BL/6 J male mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbour, ME, USA) were subjected to destabilization of medial meniscus (DMM) or sham surgery, as previously reported [7]. Mice were injected with PBS + DMSO (vehicle) or ATX inhibitor (PF-8380, Pfizer). Mice were injected using two different regimens: i) at three and five weeks post-surgery (n = 5 for each Sham group, n = 10 for each DMM group) (Fig. 1C), or ii) at two, four, six and eight weeks post-surgery (n = 9 for each group) (Supple Fig. 1A). For each injection paradigm, mice were randomly allocated into four treatment groups: Sham Surgery + vehicle injection; Sham + ATX inhibitor injection; DMM + vehicle injection; DMM + ATX inhibitor injection. For both treatment regimens, 1 mg of lyophilized ATX inhibitor was dissolved in PBS and DMSO in a 1:1 ratio and 5 μl of ATX inhibitor was intra-articularly injected to the knee joints at a final dose of 2.5 ng per mouse joint [8]. Mouse knee joints were collected at 10 weeks post-surgery followed by histopathological and immunohistochemical studies. Procedures were approved by the institutional animal care committee (#3729.19).

Figure 1.

Intra-articular injection of ATX inhibitor partially attenuates DMM-induced cartilage damage. (A) Safranin-O/Fast green staining showing the less degenerated and severely degenerated regions of human knee OA articular cartilage; (B) immunohistochemical expression of autotaxin (ATX) in less degenerated (control) and severely degenerated knee OA human articular cartilage. Immunohistochemical quantification of ATX positive cells in less degenerated and severely degenerated sections of human knee OA articular cartilage (n = 4). Data are mean ± 95% CI. Data were log-transformed prior to analysis by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s Correction, (∗) p < 0.05. (C) Schematic diagram showing the experimental design of ATX inhibitor (PF-8380) intra-articular injections in C57BL/6J mice subjected to DMM surgery. (D) Ten-week-old mice were subjected to DMM surgery followed by intra articular injections of ATX inhibitor (2.5 ng per joint) or vehicle at three and five weeks post-DMM surgery. Joints were collected at ten weeks post-surgery and stained with Safranin-O/Fast green. Representative histological images of knee joint sections of Sham surgery + vehicle (n = 5), Sham surgery + ATX inhibitor (n = 5), DMM surgery + vehicle (n = 10) or DMM surgery + ATX inhibitor (n = 10). Magnification is 10x and 20x. (E) OARSI grading of mouse medial femoral condyle and tibial plateau and chondrocyte cellularity per area. Data are mean ± 95% CI. Data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post-hoc tests corrected for multiple comparisons by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Kriegar and Yekutieli. ∗, #, adjusted p < 0.01 compared to data not labelled with the same individual symbol.

2.2. Patient samples

Knee OA cartilage and chondrocytes were obtained from consented patients (approved REB protocol #14-7592-AE) undergoing total knee replacement (TKR) surgery (n = 4, age: 63–78 years, BMI 24.54–48.46, Kellgren-Lawrence Grade III/IV). Chondrocytes obtained from 4 separate patients were treated with 10 μM ATX inhibitor or DMSO (control) for 24 h and subjected to RNA sequencing and computational analysis as described in the supplementary methods.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data has been presented as scatter dot plots with mean ± 95% CI. Percent and count data was log-transformed prior to statistical analysis. Statistical significance comparing two groups with parametric data was assessed by two-tailed, unpaired Student's T-tests with Welch's correction and non-parametric data was assessed by Mann-Whitney tests. Statistical analysis comparing multiple groups with non-parametric data was performed by Kruskal-Wallis with Geisser-Greenhouse correction or Freidman tests followed by post-hoc tests corrected for multiple comparisons by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Kriegar and Yekutieli. Adjusted (multiple comparisons) or unadjusted p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparison tests.

Detailed methodology is provided in the Supplementary Methods. The mRNA sequencing data have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE151937.

3. Results

We first investigated whether ATX expression is modified in the local tissue environment in human OA cartilage. In cartilage collected from OA patients undergoing total knee replacement (TKR) exhibiting Kellgren Lawrence (KL) grade III/IV, we identified significantly higher proportions of ATX positive chondrocytes in more severely degenerated cartilage as compared to less degenerated cartilage (Fig. 1A and B). We also investigated the expression of ATX in mouse knee joints at two and five weeks post-DMM surgery. We found that expression of ATX was detectable in the articular cartilage, synovium and fibrocartilage with no significant difference in expression (p > 0.05) in each tissue at two and five weeks post-surgery.

We next investigated if local delivery of the ATX inhibitor protects knee cartilage from degeneration and reduces synovitis in a pre-clinical model of injury-induced OA. Histomorphometric OARSI scoring of Safranin O-stained mouse knee joints at 10 weeks post-surgery showed that mice that received DMM surgery and ATX inhibitor injections at three and five weeks post-surgery exhibited a partial protection from cartilage degeneration in the medial tibial plateau, compared to mice that received DMM surgery and vehicle treatment (Fig. 1C, D, E). No significant changes in OARSI scores in the medial femoral condyle were observed in DMM mice injected with vehicle or ATX inhibitor. We also observed significantly higher chondrocyte cellularity in the medial tibial plateau in DMM mice treated with ATX inhibitor compared to DMM mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 1E), suggesting reduced chondrocyte loss with ATX inhibitor treatment.

Since we observed partial cartilage-protective effects in mice treated with two intra-articular injections of ATX inhibitor, we next tested whether increasing the frequency injection could provide better protection against cartilage loss in DMM mice. At 10 weeks post-surgery, we found no significant change in OARSI scores of the medial femoral condyles or tibial plateaus of DMM mice injected with ATX inhibitor at two, four, six and eight weeks post-surgery compared to vehicle-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 2A&B). These histopathological studies indicate that inhibition of ATX using PF-8380 at three and five weeks post-surgery partially attenuated cartilage degeneration and chondrocyte loss in the DMM-induced OA mouse model; however, changing the initial timing and increasing the frequency of ATX inhibitor injections did not impart any cartilage-protective effects.

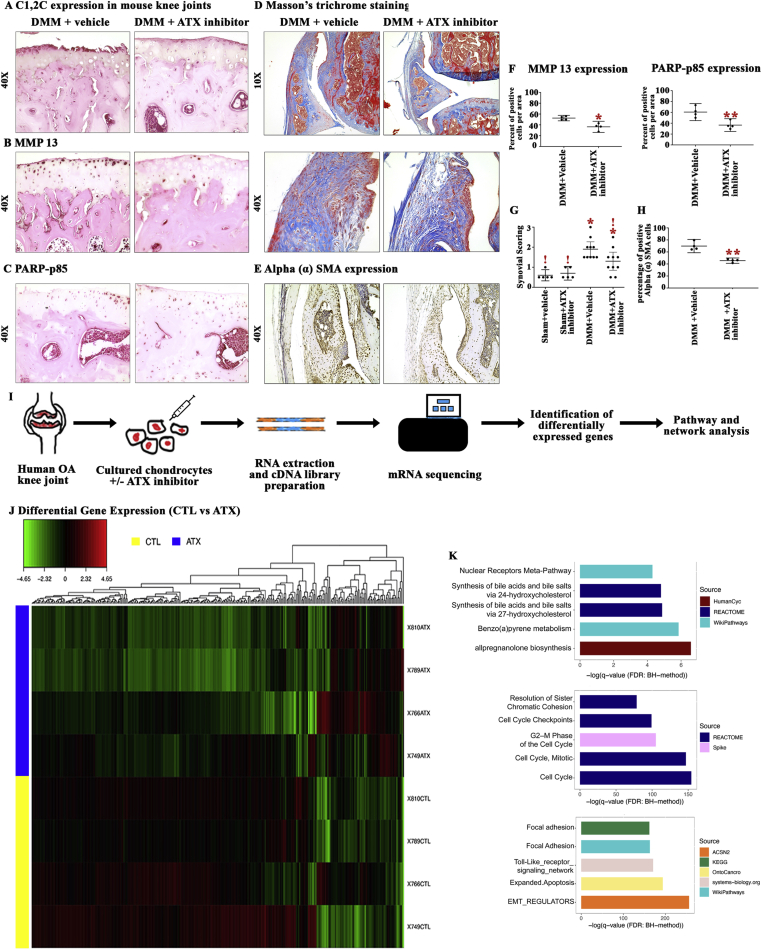

We next performed immunohistochemical studies on knee joint sections from mice injected with vehicle or ATX inhibitor at three and five weeks post-surgery to evaluate markers of cell death (PARP p85), type II cartilage catabolic enzymes (MMP13) and MMP13-mediated cartilage catabolism (C1,2C). We found the intensity of C1, 2C staining was reduced in the superficial zone of articular cartilage of ATX inhibitor-treated DMM mice whereas cartilage fibrillations and intense staining were present at the cartilage surface in DMM mice injected with vehicle (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining of mouse knee cartilage revealed a reduced percentage of MMP13- and PARP p85-positive chondrocytes in ATX inhibitor-compared to vehicle-treated DMM mice (Fig. 2B, C, F). Thus, our data suggest that local pharmacological inhibition of ATX partially protects knee cartilage from damage in DMM-induced OA associated with the reduced cartilage catabolic activity and chondrocyte apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Effect of ATX inhibition on the expression of key OA phenotypic markers in vivo and mRNA sequencing of ATX-treated human OA chondrocytes. (A, B, C) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for C1, 2C (Type II collagen proteolysis), MMP13 (type II collagenase) and PARP p85 (apoptotic marker) in mouse medial tibial plateau (n = 4). (D) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome stained sections of mouse synovium following DMM surgery + vehicle or DMM surgery + ATX inhibitor injection. (E) Immunohistochemical stained images of αSMA positive cells in DMM surgery + vehicle and DMM surgery + ATX inhibitor injected mice groups (n = 4). (F) Quantification of the percentage of MMP13 & PARP p85 positive cells per area in DMM surgery + vehicle and DMM surgery + ATX inhibitor injected mice. Data are mean ± 95% CI. Data was log-transformed prior to analysis by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s T-test with Welch’s correction. (∗) p < 0.05, (∗∗) p < 0.01. (G) Degree of synovitis was scored in knee sections from Sham and DMM mice injected with ATX inhibitor or vehicle (Sham n = 5/group, DMM n = 10/group). Data are mean ± 95% CI. Synovial scoring data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post-hoc tests corrected for multiple comparisons by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Kriegar and Yekutieli. ∗, !, p < 0.01 compared to bars not labeled with the same individual symbol. (H) The proportion of αSMA positive synoviocytes was quantified in DMM surgery + vehicle and DMM surgery + ATX inhibitor injected mice groups (n = 4/group). Data are mean ± 95% CI. Data was log-transformed prior to analysis by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s T-test with Welch’s correction. (∗∗) p < 0.01. (I) Schematic diagram of sample preparation, sequencing and analysis workflow. (J) The heatmap shows the log Fold Change (logFC) relative to the mean of all samples within each gene, calculated using TMM adjusted CPM+1 counts. (K) Top 5 pathways obtained using pathDIP that are enriched in upregulated and downregulated genes, and common interactors (see supplementary Tables 2–4 for full lists of enriched pathways). Color of each bar shows the source database for each pathway, while the x-axis shows the negative logarithm of q-value (FDR: BH-method).

To determine whether ATX inhibitor exhibits any effect on ECM remodeling of the synovium in the DMM mouse model, we stained mouse knee joint sections with Masson's trichrome and graded the severity of synovitis. Synovitis scores in joints of mice were significantly greater in joints of mice with DMM-surgery alone compared to sham-operated mice with or without ATX-inhibitor injection. Intra-articular injection of ATX inhibitor at three and five weeks post-surgery exhibited a moderate decrease in the degree of synovitis compared to DMM mice injected with vehicle (adjusted p = 0.0610). It is important to note that the degree of synovitis in DMM mice injected with ATX inhibitor was not significantly different from sham mice injected with vehicle or ATX inhibitor (adjusted p = 0.0597 and 0.0737, respectively; Fig. 2D and G). Using immunohistochemistry, we also determined that expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA), a marker of myofibroblasts, highly active fibrogenic cells [9], was significantly reduced in DMM mice injected with ATX inhibitor compared to DMM mice injected with vehicle (Fig. 2E and H). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the degree of synovitis of DMM-surgical mice that received ATX inhibitor injections at two, four, six and eight weeks post-surgery, as compared to DMM mice treated with vehicle (Supplementary Fig 2C). These results indicate that local injection of ATX inhibitor at three and five weeks post-surgery partially reduces the degree of cartilage degeneration with a moderate decrease in the severity of synovitis in DMM-induced OA in mice.

Since we observed partial cartilage-protective effects of ATX inhibition in vivo, to understand the effects of ATX inhibition on chondrocyte expression profiles, we next subjected human OA chondrocytes isolated from TKR cartilage and treated with/without ATX inhibitor to mRNA sequencing followed by pathway enrichment analysis (see schematic in Fig. 2I). ATX inhibition in OA chondrocytes altered the expression of 2650 genes (False Discovery Rate < 0.05; Supplementary Table 1), 80 of which were significantly upregulated (with minimum Log2 Fold Change ≥ 1) and 265 were significantly downregulated (with minimum Log2 Fold Change ≤ −1 as highlighted in the heat map (Fig. 2J). Fig. 2J lists the top ten genes that were up or downregulated in ATX-treated chondrocytes.

We then identified common protein-protein interactors (PPIs) for the lists of 80 up and 265 downregulated genes in response to ATX inhibition to identify common PPIs using the Integrated Interactions Database v.2018–11 (IID, http://iid.ophid.utoronto.ca/; Supplementary Fig. 3) and the network was visualized using NAViGaTOR 3.0.8 (http://142.150.188.236/navigatorwp).

We then subjected upregulated and downregulated genes and common PPIs to pathway enrichment analysis using pathDIP (http://ophid.utoronto.ca/pathDIP/; Fig. 2K). The top five pathways identified from the list of upregulated genes in response to ATX inhibition, which were involved in metabolism of cholesterol analogues. All eight pathways associated with the upregulated genes are available in Supplementary Tables 2. The top five pathways identified from the list of downregulated genes in response to ATX inhibition were associated with cell cycle processes. A complete list of the 252 pathways associated with downregulated genes are listed in Supplementary Table 3. From the group of common interactors, 2581 genes were found corresponding to 1958 enriched pathways (Supplementary Table 4), with the top five pathways involved in mechanisms and signaling associated with ECM and inflammation. Furthermore, word enrichment on enriched pathways using Wordle highlighted key pathways related to metabolism, cell cycle, inflammation and ECM in response to ATX inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 4).

4. Discussion

Herein, we tested the OA disease modifying effects of ATX inhibitor (PF-8380) in a mouse model of OA. In our previous study, we identified that lysophosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylcholine metabolites increase during OA pathogenesis in mice and that destructive mechanisms associated with OA are, in part, ATX-dependent [10]. Moreover, increased expression levels of ATX in synovial fibroblasts of human patients with RA and mouse models of arthritis are associated with the disease pathology [5]. ATX, the main lipase that converts lysoPC to lysophosphatidic acid, has been suggested to be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of several diseases [11]. In the present study, we determined that degenerated human knee OA cartilage has increased expression of ATX. Thus, levels of ATX not only increase systemically in patients with OA [4], but also locally in joint articular cartilage. Next, we investigated whether local pharmacological inhibition of ATX would attenuate pathogenesis in the DMM mouse model of OA. We chose two treatment regimens to see whether short or persistent treatment with ATX inhibitor modifies OA pathogenesis. We showed that acute treatment (three and five weeks post-surgery) partially reduced cartilage damage accompanied by reduced chondrocyte loss and moderate reduction in the degree of synovitis compared to prolonged, more frequent treatments (two, four, six and eight weeks post-surgery). This could be due to toxicity of the therapy accumulating over the prolonged treatment period or through multiple injections creating additional inflammatory insults contributing to joint damage.

Autotaxin also has ATPase and pyrophosphate (PPi)-producing activities [12]. To our knowledge, the effect of PF-8380 on ATPase or PPi-producing activity of ATX has not been studied. Reduced calcium pyrophosphate crystals and increased ATP signaling by purinergic receptors, including P2X7, can have opposite effects on OA pathology [13,14]. Although beyond the scope of this study, these alternative enzymatic functions of ATX could also contribute to the partial protection of DMM-induced OA observed in this study and the failure of earlier and more frequent treatment to provide disease modification.

Our early and acute treatment protocol with ATX inhibitors in the DMM model of OA suggests that the therapy may exhibit cartilage-protective effects, in addition to pain and fibrosis-modifying properties [6,15,16]. In addition to cartilage degeneration, synovitis is associated with OA and we identified that ATX inhibitor injections at three and five weeks post-surgery moderately reduced synovitis in DMM-induced OA mice. Mechanistically, reductions in cartilage degeneration and synovitis by ATX inhibition were likely a result of increased chondrocyte survival, reduced catabolic activity (MMP13-mediated type II collagen breakdown) and reduced myofibroblast differentiation (αSMA-expressing fibroblasts), as observed in our study.

To better understand the mechanism of action of ATX inhibitor on chondrocytes, we subjected ATX-treated and vehicle-treated human OA chondrocytes to mRNA sequencing and identified a list of 80 up and 265 downregulated genes in response to ATX inhibition. This list was used to identify common PPIs in IID, and then upregulated and downregulated genes and common PPIs were used to perform pathway enrichment analysis, to identify key pathways involved in cholesterol analogue metabolism, ECM remodeling process, inflammation and cell cycle that could be modulated by ATX inhibition, mechanisms associated with ATX activity associated with cartilage injury and other pathologies [[17], [18], [19], [20]].

Thus, our study, for the first time, shows that local injection of ATX inhibitor is partially protective of knee joint pathologies associated with the DMM mouse model of OA. Further studies using ATX inhibitors are still required to validate its exact mechanism of action and additional optimization to improve the effectiveness of ATX inhibition to OA disease modification warrants further investigation.

Contributorship

PD was involved in the design of the study, immunohistochemistry assays, cell culture study, next generation library preparation, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. RG performed extraction of the clinical samples for the in vitro study, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. SN performed animal surgeries in the mouse knee joints, performed tissue dissections along with PD, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. SL performed and helped library preparations for the next generation sequencing, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. ER performed histology and staining of mice knee joints, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. PP performed the next generation sequencing data analysis using bio informatics tools, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. KS performed the bio statistical analysis of the next generation sequencing data, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. HE performed cell culture study with PD, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. CP & IJ performed protein interaction network and pathway enrichment analysis of the next generation sequencing data, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. JSR was involved in design of the study, the interpretation of data, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. MK was involved in the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, drafted, revised the article critically and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

501100001804This work is supported in part by the Canada Research Chairs Program (#950-232237), Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating grant (#377743), The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC; #2017-06360), Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Ontario Research Fund (RDI #34876), IBM, Lenovo, Ian Lawson van Toch Fund, The Toronto General and Western Hospital Foundation and The Arthritis Program, University Health Network.

Ethical approval information

Animal procedures were approved by the animal care committee of the Krembil Research Institute, University Health Network (Animal Protocol Number: 3729.19). Use of human tissue was approved by the UHN Institutional Ethics Committee Board (REB: 14-7592-AE).

Data sharing statement

All relevant data to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Kim Perry for her contribution to tissue biobanking and processing as part of these studies.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2020.100080.

Appendix. ASupplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Dickson B.M., Roelofs A.J., Rochford J.J., Wilson H.M., De Bari C. The burden of metabolic syndrome on osteoarthritic joints. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019;21:289. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-2081-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter D.J., Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393:1745–1759. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotoh M., Fujiwara Y., Yue J., Liu J., Lee S., Fells J., et al. Controlling cancer through the autotaxin-lysophosphatidic acid receptor axis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012;40:31–36. doi: 10.1042/BST20110608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mabey T., Taleongpong P., Udomsinprasert W., Jirathanathornnukul N., Honsawek S. Plasma and synovial fluid autotaxin correlate with severity in knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2015;444:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikitopoulou I., Oikonomou N., Karouzakis E., Sevastou I., Nikolaidou-Katsaridou N., Zhao Z., et al. Autotaxin expression from synovial fibroblasts is essential for the pathogenesis of modeled arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:925–933. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thirunavukkarasu K., Swearingen C.A., Oskins J.L., Lin C., Bui H.H., Jones S.B., et al. Identification and pharmacological characterization of a novel inhibitor of autotaxin in rodent models of joint pain. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:935–942. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasson S.S., Blanchet T.J., Morris E.A. The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gierse J., Thorarensen A., Beltey K., Bradshaw-Pierce E., Cortes-Burgos L., Hall T., et al. A novel autotaxin inhibitor reduces lysophosphatidic acid levels in plasma and the site of inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:310–317. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.165845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun K.H., Chang Y., Reed N.I., Sheppard D. alpha-Smooth muscle actin is an inconsistent marker of fibroblasts responsible for force-dependent TGFbeta activation or collagen production across multiple models of organ fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2016;310:L824–L836. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00350.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datta P., Zhang Y., Parousis A., Sharma A., Rossomacha E., Endisha H., et al. High-fat diet-induced acceleration of osteoarthritis is associated with a distinct and sustained plasma metabolite signature. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8205. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07963-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matralis A.N., Afantitis A., Aidinis V. Development and therapeutic potential of autotaxin small molecule inhibitors: from bench to advanced clinical trials. Med. Res. Rev. 2019;39:976–1013. doi: 10.1002/med.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clair T., Lee H.Y., Liotta L.A., Stracke M.L. Autotaxin is an exoenzyme possessing 5'-nucleotide phosphodiesterase/ATP pyrophosphatase and ATPase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:996–1001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fam A.G., Morava-Protzner I., Purcell C., Young B.D., Bunting P.S., Lewis A.J. Acceleration of experimental lapine osteoarthritis by calcium pyrophosphate microcrystalline synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:201–210. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu H., Yang B., Li Y., Zhang S., Li Z. Blocking of the P2X7 receptor inhibits the activation of the MMP-13 and NF-kappaB pathways in the cartilage tissue of rats with osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016;38:1922–1932. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bain G., Shannon K.E., Huang F., Darlington J., Goulet L., Prodanovich P., et al. Selective inhibition of autotaxin is efficacious in mouse models of liver fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;360:1–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.237156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ongenaert M., Dupont S., Blanqué R., Brys R., van der Aar E., Heckmann B. Strong reversal of the lung fibrosis disease signature by autotaxin inhibitor GLPG1690 in a mouse model for IPF. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;48:OA4540. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu L., Petrigliano F.A., Ba K., Lee S., Bogdanov J., McAllister D.R., et al. Lysophosphatidic acid mediates fibrosis in injured joints by regulating collagen type I biosynthesis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keune W.J., Hausmann J., Bolier R., Tolenaars D., Kremer A., Heidebrecht T., et al. Steroid binding to Autotaxin links bile salts and lysophosphatidic acid signalling. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11248. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castelino F.V., Bain G., Pace V.A., Black K.E., George L., Probst C.K., et al. An autotaxin/lysophosphatidic acid/interleukin-6 amplification loop drives scleroderma fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68:2964–2974. doi: 10.1002/art.39797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakai N., Bain G., Furuichi K., Iwata Y., Nakamura M., Hara A., et al. The involvement of autotaxin in renal interstitial fibrosis through regulation of fibroblast functions and induction of vascular leakage. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7414. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43576-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.