Abstract

COVID-19 has had dramatic impacts on economic outcomes across the United States, yet most research on the pandemic’s labor-market impacts has had a national or urban focus. We overcome this limitation using data from the U.S. Current Population Survey’s COVID-19 supplement to study pandemic-related labor-force outcomes in rural and urban areas from May 2020 through February 2021. We find the pandemic has generally had more severe labor-force impacts on urban adults than their rural counterparts. Urban adults were more often unable to work, go unpaid for missed hours, and be unable to look for work due to COVID-19. However, rural workers were less likely to work remotely than urban workers. These differences persist even when adjusting for adults’ socioeconomic characteristics and state-level factors. Our results suggest rural-urban differences in the nature of work during the pandemic cannot be explained by well-known demographic and political differences between rural and urban America.

Keywords: COVID-19, Labor force, Employment, Rural, Urban

Introduction

The economic disruptions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic have been unprecedented in the United States, including record-high unemployment claims (Brave, Butters, and Fogarty 2020; Brynjolfsson et al. 2020), widespread food and housing insecurity (Cowin, Martin, and Stevens 2020; Enriquez and Goldstein 2020; Morales, Morales, and Beltran 2020), and rising physical and emotional health challenges (Pfefferbaum and North 2020; Stainback, Hearne, and Trieu 2020). The majority of empirical work (to date) on the pandemic’s labor-market impacts has focused on either the nation as a whole or the urban population, with rural populations—approximately 46 million people—remaining understudied (Mueller et al. 2021).1 This evidence gap reflects an absence of high-quality secondary data on rural areas (Hauer and Santos-Lozada 2021; Mueller et al. 2021; Pender 2020).2 The limited evidence that is available suggests the presence of considerable geographic heterogeneity between rural and urban areas in the pandemic’s impacts. Given varying patterns of disease prevalence, local mitigation strategies (Karim and Chen 2021; Lakhani et al. 2020; Morales et al. 2020; Paul et al. 2020; Souch and Cossman 2021), and economic structure between urban and rural areas (Lichter and Brown 2011; Vias 2012), there are strong a priori reasons to expect rural-urban variation in the labor force impacts of the pandemic. Assessing these disparities advances our understanding of how the pandemic has influenced spatial and regional inequalities in the United States and has the potential to inform mitigation and recovery policies.

We address this knowledge gap by analyzing newly-released monthly data from the COVID-19 supplement of the U.S. Current Population Survey (CPS). We evaluate the pandemic’s impact on the rural and urban labor force through three objectives. First, we estimate the prevalence of four COVID-19-related employment outcomes among rural and urban adults for each month from May 2020 through February 2021. In doing so, we assess whether there was a rural disadvantage (i.e., rural adults more often experienced negative outcomes) over the study period and track changes in the magnitude of rural-urban differences in these outcomes over time. Second, given well-known differences in the demographic composition and policy context of rural and urban areas (Glasgow and Brown 2012; Lee and Sharp 2017; Thiede and Slack 2017) we estimate a series of multiple regression models to evaluate whether any observed rural-urban differences can be explained by these factors. Finally, we evaluate these same employment outcomes separately for more- and less-educated adults, as the latter are often at heightened risk of layoffs, furloughs, and other work disruptions (Kesler and Bash 2021). The findings from this study provide substantive lessons about the immediate impacts of COVID-19 on rural and urban areas and can also inform long-term relief and economic development policies and efforts.

COVID-19 in Rural and Urban America

Scholarly attention to the COVID-19 outbreak has been centered on epidemiology and public health, focusing on infection rates and mortality patterns. However, the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic are also salient and merit attention given their widespread and potentially long-lasting impacts (Matthewman and Huppatz 2020; Ward 2020). In the early months of the pandemic, over 26 million unemployment insurance claims were filed and over 31 percent of families reported some form of material hardship related to COVID-19 (Karpman et al. 2020). Polyakova and colleagues (2020) found for April 2020 that employment disruptions were severe, with employment rates 9.8 percentage points lower than traditional Bureau of Labor Statistics models would have projected. Rates of working remotely also greatly increased, with one study estimating that roughly 35 percent of employed adults switched to remote work due to COVID-19 (Brynjolfsson et al. 2020).

The risk of unemployment and other employment disruptions related to COVID-19 is significantly affected by several demographic factors, with education principal among them (Daly, Buckman, and Seitelman 2020; Kesler and Bash 2021). Kesler and Bash (2021) estimated that less-educated parents were between 2 and 2.5 times more likely to experience COVID-19-related unemployment than highly-educated parents. Employment rates in May 2020 were 8.8 percentage points higher among those with Bachelor’s degree than those with a high school diploma or less (Daly et al. 2020). However, these studies (and many other related analyses) only examined nation-wide, state-level, or metropolitan-area impacts (Brave et al. 2020; Cho, Lee, and Winters 2020), leaving little evidence about whether and how impacts varied between rural and urban areas. This is an important gap since rurality represents an increasingly salient axis of both health and socioeconomic inequality in the United States (Burton et al. 2013; Lichter and Ziliak 2017; Singh and Siahpush 2014).

Indeed, rural and urban areas of the United States differ in a number of important ways relevant to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. First, there is a marked difference in age structure with rural areas being significantly older (Glasgow and Brown 2012; Johnson 2020). The U.S. Census Bureau reports a seven year difference in median age between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties (36.0 vs. 43.0 years) (Cheeseman Day, Hays, and Smith 2016). Differences in age structure are accompanied by disparities in health (Burton et al. 2013), with rural populations characterized by higher prevalence of health-compromised individuals and higher mortality rates than urban populations (Brooks, Mueller, and Thiede 2020; Henning-Smith 2020; Peters 2020). This rural health disadvantage may translate into higher rates of rural adults being unable to work due to heightened fear of contracting COVID-19 (e.g., due to pre-existing conditions) or because of increased caregiving demands.

Beyond these compositional differences, access to healthcare is also lower in rural areas, likely amplifying differences in COVID-19-related employment disruptions between rural and urban residents. Indeed, many rural residents may not be able to be tested for COVID-19, seek medical care upon disease contraction, or obtain a COVID-19 vaccine (Burton et al. 2013; Peters 2020; Souch and Cossman 2021; Ullrich and Mueller 2021). While COVID-19 rates and deaths in rural counties have generally been lower than rates in urban counties (Dobis and McGranahan 2021; Karim and Chen 2021; Paul et al. 2020), the exact differences in rates are difficult to estimate due to both variance in testing (Souch and Cossman 2021) and underlying data constraints affecting data quality for rural populations.

Rural economies may also be more vulnerable to pandemic-related shocks. Many areas of the rural United States are dependent on a single industry such as agriculture or natural amenity-related tourism (Mueller 2020; Thiede and Slack 2017). Industry-specific shutdowns—either governmental or self-mandated—are therefore likely to have amplified effects on employment throughout rural labor markets. Additionally, work in rural America is more precarious than employment in urban areas as measured by rates of underemployment, labor force nonparticipation, and working poverty (Mclaughlin and Coleman-Jensen 2014; Thiede, Lichter, and Slack 2018). For example, Slack and colleagues (2019) find that for 2013–2017, 19.1 percent of rural adults were underemployed, compared to 17.4 percent of comparable urban adults. Rural workers are also more likely to be self-employed or work at small businesses, which have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic (Headd 2010; Vias 2012). Lin et al. (2021) find that individuals employed at small firms—firms with less than 10 employees—experienced COVID-19-related increases in unemployment that were nearly 7.5 percent higher than for individuals employed at large firms with over 1000 employees. Compounding these vulnerabilities, urban adults tend to have higher educational attainment, which is positively associated with labor market outcomes (Farrigan 2020).3 These rural disadvantages in employment and education structure may make rural adults more prone to COVID-19-related layoffs or furloughs and less likely to be compensated for hours not worked.

Importantly, there are also reasons to expect that rural labor markets have fared better during the pandemic. While rural areas are not as overwhelmingly white as often portrayed, they are still home to a higher proportion of white residents than urban areas (Lee and Sharp 2017; Lichter 2012). Given significant inequalities in COVID-19 mortality, infection rates, wealth, and economic hardships between white and non-white Americans due to deep-seated structural inequalities (Cheng, Sun, and Monnat 2020; Dias 2021; Enriquez and Goldstein 2020; Henning-Smith, Tuttle, and Kozhimannil 2021; Morales et al. 2020; Wrigley-Field et al. 2020), it is likely that rural-urban differences in racial composition may create a relative rural advantage in labor force impacts.

Additionally, geographic differences in government mandates and shutdowns may also represent a source of rural advantage in labor force impacts (G. Lin et al. 2021; Pender 2020). For example, Adolph et al. (2020) find that governors of states with lower population density were 31.3 percent less likely to implement social distancing mandates in the early weeks of the pandemic than governors of more densely-populated states.4 This less-aggressive implementation of COVID-19 policy in more rural states may have led to less severe labor force impacts during the pandemic. At the individual level, there is also evidence that rural workers were less likely to choose to work from home and employ other personal disease-prevention behaviors (Callaghan et al. 2021). Further, many industries primarily located in rural areas (e.g., meatpacking) were deemed essential by the federal government, and thus many rural workers were mandated to remain at work despite high infection rates of COVID-19 (Graff Zivin and Sanders 2020; Taylor, Boulos, and Almond 2020). Somewhat perversely, such outcomes may manifest as a rural advantage in labor market outcomes despite their potentially large human toll. Rural school districts were also less likely to remain closed or operate remotely for extended periods of time, lessening childcare-related pressures on employment (Gross and Opalka 2020). Finally, COVID-19 has also been shown to have had less employment impacts on firms whose business cannot be done remotely—such as agriculture and manufacturing (K. Lin et al. 2021)—further suggesting that rural workers may have been less likely to lose work due to the pandemic.

As the review above demonstrates, prior research supports competing expectations about the relative advantages and disadvantages faced by rural workers during the pandemic. While we nonetheless acknowledge valid reasons to expect an urban disadvantage, we conduct our analysis under the provisional hypothesis that rural adults faced more severe labor force impacts than urban adults. We further expect this disadvantage to be partially explained by rural-urban differences in socioeconomic composition and state-level policy.

Current Study

Our overall goal is to evaluate whether and how the labor-force impacts of COVID-19 varied between rural and urban areas of the United States. Using newly-available data from the U.S. Census Bureau, we focus on COVID-19-related disruptions to (a) work, (b) receipt of pandemic-related wage supports, (c) employment seeking, and (d) ability to work remotely. We assess the prevalence of these four outcomes among rural and urban adults by producing unadjusted estimates of monthly trends and regression-adjusted estimates that control for key demographic, economic, and state-level factors.

Data and Measures

We analyze microdata from the COVID-19 supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS), which we extracted via IPUMS-CPS (Flood et al. 2021). Our dataset covers each month from May 2020 through February of 2021, which is the entire period that the supplemental COVID-19 questions were available at the time of writing. Given the CPS sampling strategy, individuals may be observed across multiple months and cases should be interpreted as person-period observations. Our analytic sample includes only working-age civilian adults aged 18 to 65 years (n = 622,388) to avoid biases associated with selective differences in work among younger and older adults. Throughout this study we respectively define rural and urban people as those who live in counties that are defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget as nonmetropolitan and metropolitan, respectively (Office of Management and Budget 2010).5 We also stratify adults based on their education to assess whether less-educated adults were particularly hard-hit by the pandemic’s economic impacts. For that part of our analysis, individuals are classified as less educated if they have a high school education or less (n = 226,398), and more educated if they have some college education or more (i.e. bachelor’s degree+) (n = 395,990).6 Primary emphasis is given to documenting the trends among less-educated adults as they constitute the more vulnerable group.

The four labor force outcomes of interest were all asked in reference to the four weeks preceding survey administration. Importantly, the universes of the questions varied. First, all adults in the sample (n = 622,388) were asked whether they were unable to work because their place of work closed or lost business due to the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., unable to work).7 Data on the second outcome—whether an individual received pay for hours not worked due to COVID-19 (i.e., paid for missed hours)—were collected only among those who were unable to work because their employer closed or lost business due to COVID-19 (n = 60,870). Third, individuals not in the labor force (n = 158,273) were asked whether they were unable to look for work due to the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., unable to look for work). Forth and finally, for whether or not a person worked remotely due to COVID-19 (i.e., worked remotely), the universe included all adults employed at the time of the survey (n = 429,748).

Analytical Strategy

This study contains two sets of analysis. First, we estimate the monthly prevalence of each outcome of interest among rural and urban adults from May 2020 through February 2021.8 These estimates allow us to evaluate whether and how rural individuals were, overall, advantaged or disadvantaged compared to urban adults and to evaluate if these differentials changed over time. Second, we conduct a similar analysis but stratify the sample by educational attainment, distinguishing between less-educated adults and more-educated adults. Within both the overall and stratified analyses, we produce unadjusted estimates of monthly trends and two sets of regression-adjusted estimates.9 We produce adjusted estimates of COVID-19 outcomes by estimating a series of binary logistic regression models, which control for socioeconomic and state-level factors described below.10

Each of our four outcomes is modeled as a function of a binary indicator of rural (urban) status, month, a set of month-by-rural interactions, and a set of controls. These focal variables allow us to estimate adjusted differences in outcomes between rural and urban adults during each month in our data. Standard errors in these regressions are clustered on the person to account for repeated observations inherent to the CPS sampling structure (U.S. Census Bureau 2019).11

The first specification of the regression models includes controls for socioeconomic structure: race, education, industry of employment, age, marital status, immigrant status (ref = immigrant), sex (ref = male), household size, and number of children in the household. We classify individuals as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic of any race, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, and non-Hispanic other race. We utilize four categories of education: less than a high school education, a high school education, some college education, and a bachelor’s degree or higher. We categorize individual’s industry of employment into 13 major groups based on the 2020 Census Industry Codes (U.S. Census Bureau 2020)12, and an additional group for those not in the labor force due to retirement, disability, school, or another reason.13 We utilize age groups of 18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, and 56–65 years old, which allows us to flexibly account for age differences in employment outcomes. Finally, we use three marital status groups: married, divorced, separated, or widowed, and single.

The second specification—which we refer to as policy-adjusted or fully-adjusted estimates—introduces additional controls for state policies and socioeconomic context as captured by an indicator of state-level at-restaurant dining closures and state fixed effects. Accounting for such factors is important since rural and urban populations are distributed unevenly across U.S. states, and thus they are unevenly exposed to relevant state-level factors. Using data produced by Raifman et al. (2021), we create an indicator for whether an individual’s state of residence had an at-restaurant dining closure—meaning restaurants were prohibited from serving individuals at the restaurant (either inside or outside)—during any part of the month. This type of policy has been dynamic at the state level over the study period, and we expect it to be correlated with other pandemic-related restrictions. We also capture time-invariant state factors by including state fixed effects, which account for all time-invariant factors at the state level—meaning they would impact both rural and urban areas within that state—including economic and political structure.

In the body of this study we present our main results visually as adjusted and unadjusted estimates of the prevalence of each outcome and provide the full tabular results of each model in the supplemental materials (Tables A1 to A9). Further, to assist with substantive interpretation of our results, we evaluate the significance of the rural-urban coefficient for each month for each COVID-19 outcome of interest and describe these findings narratively.14 The full results of these significance tests are available in Tables A10 and A11 of the supplemental materials.

Results

We begin by describing general patterns of employment and labor force participation during the pandemic. Overall, we find that the labor-force impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic varied significantly between working-age adults in the rural and urban United States. Employment among those in the labor force declined dramatically in both rural and urban areas. Compared to pre-pandemic (January) employment rates of 95.1 percent and 96.1 percent, in May, just 57.8 percent of rural adults and 41.2 percent of urban adults worked with no COVID-19 related disruptions. Non-disrupted employment rose by February—increasing to 84.1 percent and 66.3 percent for rural and urban areas, respectively—yet remained below pre-pandemic levels.

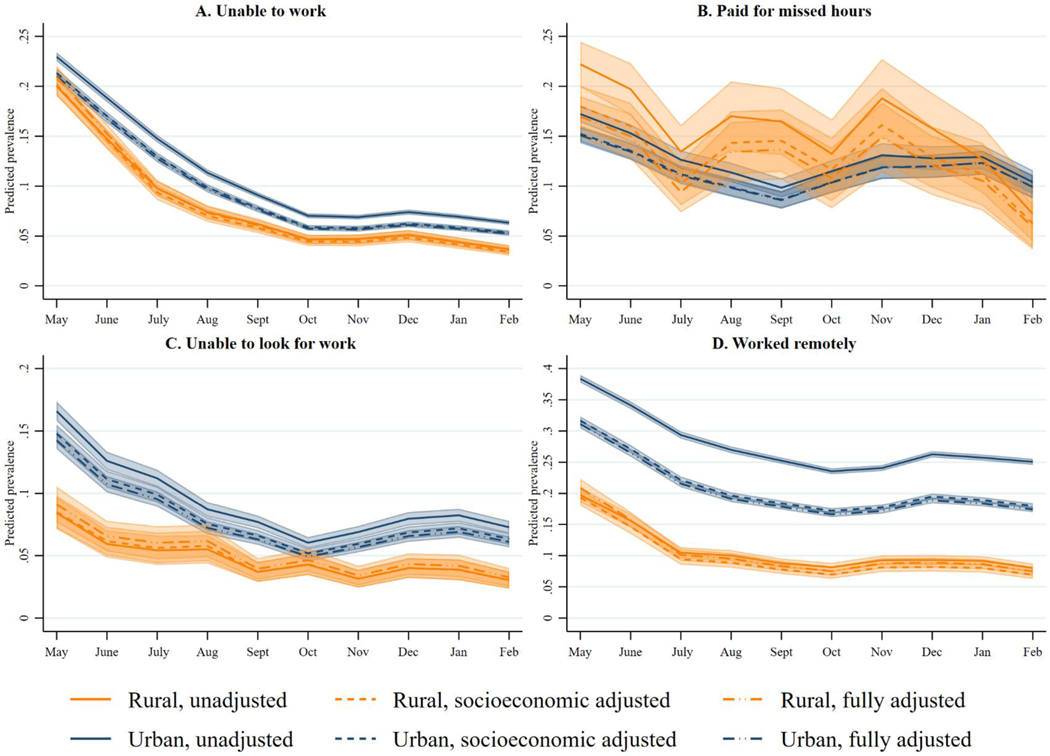

Next, we consider the prevalence of self-reported inability to work due to the pandemic. Consistent with broader trends of employment, in May, 20.0 percent of rural adults reported being unable to work due to COVID-19 compared to 23.0 percent of urban adults (Fig. 1A). The prevalence of this outcome declined substantially by February, with a 16.3 percentage-point decrease in rural areas and a 16.6 percentage-point decline in urban areas. The rural-urban difference thus declined to 2.7 percentage points. When adjusting for socioeconomic composition and state-level policy characteristics, we find that the rural advantage remains statistically significant for the majority of months in both specifications (10 and 9 months, respectively). In May, the rural-urban disparity in the socioeconomic adjusted model stood at 1.2 points. However, rural-urban disparities were not statistically significant in the fully-controlled model for this month, suggesting a substantial share of the disparities in the early months of the pandemic can be attributed to differences in socioeconomic composition and state-level policies.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted, socioeconomic, and fully-adjusted prevalence of COVID-19 outcomes for rural and urban adults by month. Shaded area is 95% confidence interval.

We next consider patterns in the receipt of wage supports. Here, we find evidence of an ephemeral rural advantage in the prevalence of being paid for hours not worked due to COVID-19 (Fig. 1B), wherein we find a significant rural effect in 5 of the 10 study months. In May, 22.2 percent of rural adults with pandemic-related work disruptions reported being paid for missed work, which was 5.0 percentage points higher than the rate among corresponding urban adults (17.2%). Rural-urban differences in pay for those unable to work decreased by February to a statistically non-significant 3.2 percentage points, with rural and urban rates at 7.2 percent and 10.4 percent, respectively.15 Indeed, the prevalence of being paid for hours not worked decreased for both groups indicating that being unable to work became more perilous over time.

Our adjustments explain a non-trivial portion of the rural-urban difference in payment for hours not worked. For example, the May socioeconomic-adjusted and fully-adjusted rural-urban differences were reduced to 2.7 points and 1.8 points, respectively, and were non-significant in the fully adjusted model. Further, we find that there was no statistically significant rural effect in our fully-adjusted model for 7 months of the study period. Overall, these estimates suggest significant nuance over the course of the pandemic, in that while in May (the month with the highest prevalence of this outcome) rural adults were more often paid for missed hours, this advantage declined over time and can be largely explained through socioeconomic and state-level factors.

Next, we consider disruptions to job searching. We find that the prevalence of being unable to look for work due to COVID-19—which was only asked of adults not in the labor force—was significantly lower in rural than urban areas for all study months. In May, 8.4 percent of relevant rural adults were unable to look for work, slightly more than half of the rate for urban adults (16.6%) (Fig. 1C). By February, prevalence of this outcome declined in both areas to 3.0 percent and 7.3 percent, respectively. When adjusting for socioeconomic and state-policy characteristics, we find that rural areas were still significantly advantaged and thus less likely to report being unable to look for work due to COVID-19 in 8 out of 10 months of the study period. That said, socioeconomic composition and state-policy adjustments do explain part of this advantage, with our fully-adjusted estimates yielding a reduced rural advantage of 5.1 and 2.9 points in May and February, respectively.

Our final outcome of interest is the ability to work remotely, which was measured among employed adults. This is the only source of a rural disadvantage that we find in our analysis. Urban adults were decidedly more likely to work remotely than their rural contemporaries, with a significant urban advantage in all study months (Fig. 1D). In May, 19.8 percent of rural employed adults worked remotely, compared to 38.4 percent of urban employed adults—a difference of 18.6 points. Rates of working remotely decreased by February in rural and urban areas to 8.0 percent and 25.1 percent, respectively, with a large difference of 17.1 percentage points remaining. Notably, a large portion of the absolute rural-urban difference in prevalence in working remotely can be attributed to compositional factors. Although our adjustments notably reduce the absolute disparities between rural and urban areas, rural-urban differences in predicted rates of remote work remains sizeable at 10.0 and 10.1 points for these months, respectively. The implication is that rural-urban differences in rates of remote work can jointly be explained by rural-urban differences in socioeconomic characteristics (education and the types of jobs worked by more-less educated individuals likely chief among them), state-level factors, and residual rural-urban differences unaccounted for by our analysis.

Impacts by Educational Attainment

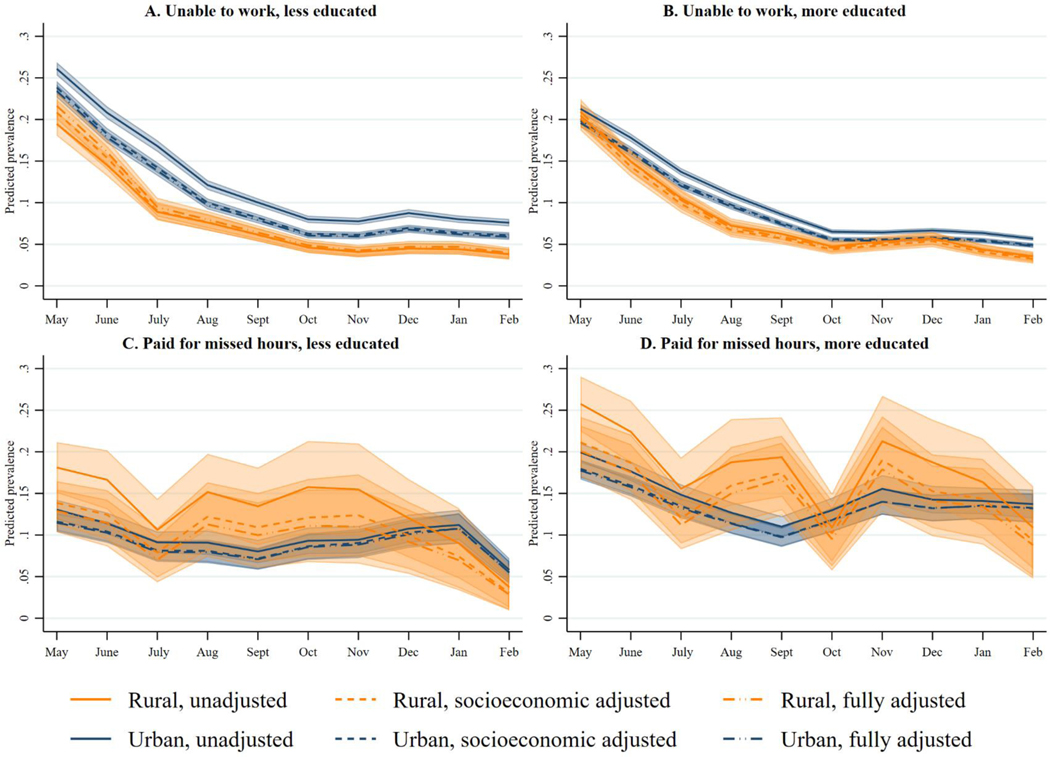

We now focus on the COVID-19 impacts experienced between more- and less-educated rural and urban adults. In May, 26.1 percent of less-educated urban adults reported being unable to work, which is 6.6 percentage points higher than among corresponding rural adults (Fig. 2A-B). By February the rural-urban advantage had declined to 3.8 points, which is still higher than the advantage observed for rural adults of all education levels for that month (2.7%). We find that rural-urban differences are still present at a statistically significant level after both the socioeconomic and policy adjustments; with a May advantage of 3.0 and 1.8 points, respectively. Among more-educated rural and urban adults the disparity in being unable to work was non-significant in May, with an unadjusted disparity of 0.8 points. However, this disparity grew over the study period and was statistically significant in all other months, with more educated urban individuals being more likely to be unable to work by 2.1 points in February. The implication is that rural-urban differences were more pronounced among the less educated.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted, socioeconomic, and fully-adjusted prevalence of select COVID-19 outcomes for more- and less-educated rural and urban adults by month. Shaded area is 95% confidence interval.

Less-educated adults in both rural and urban areas were overall very unlikely to receive pay for missed hours (Fig. 2C-D). In rural areas, only 18.1 percent of such rural adults were paid for missed work in May, and by February this rate had declined to just 3.7 percent. Urban less-educated adults experienced a smaller May to February decline at 7.2 points (13.0% vs. 5.8%), ultimately resulting in a not statistically significant urban advantage in payment for missed work by the end of the study period. In fact, throughout the study period we conclude that the vast majority of less-educated adults (over 80%) who were unable to work were not compensated for missed hours, indicating a clear COVID-19 induced hardship. When adjusting for relevant individual and state-level factors, we find that there are no months in which there are significant differences in rates between rural and urban adults of this education group. Similar to results for the less educated, we find that more-educated rural adults were more often paid for missed work than their urban counterparts, with these effects becoming generally non-significant when adjusting for socioeconomic composition and state-level policy.

Next, we find that rural adults in both education groups reported being unable to look for work due to COVID-19 significantly less often than their urban counterparts. In May, 8.7 percent of less-educated rural adults not in the labor force reported being unable to look for work due to COVID-19, compared to 16.2 percent of their urban counterparts—a difference of 7.5 points (Fig. 3A-B). The unadjusted rural advantage among the less educated remained significant in all months but shrunk to 4.2 points as urban rates fell from 16.2 to 7.6 percent across the study period. We find that socioeconomic and state-level policy adjustments reduce these disparities, particularly in the middle of the study period, but do not change our overall conclusions and do not vary notably across educational groups.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted, socioeconomic, and fully-adjusted prevalence of select COVID-19 outcomes for more- and less-educated rural and urban adults by month. Shaded area is 95% confidence interval.

Finally, we find rates of working remotely were significantly stratified along educational and rural-urban lines. In May—the month with the highest rates of remote work—only 6.9 percent of rural less-educated employed adults worked remotely, compared to 29.2 percent of more-educated employed rural adults (Fig. 3C-D). Our estimates reveal a large 25.0-point difference between educational groupings in urban areas as well (13.4% vs. 48.4%). More-educated adults in urban areas had the highest rates of working remotely out of any group, with nearly half of such adults reporting this outcome in May. These rural-urban differences for both education groups hold above and beyond compositional and policy adjustments, as we find that there is a significant rural effect for all months of the study period for both education groups leaving a clear hierarchy of rates among the four groups.

Discussion and Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to evaluate disparities in COVID-19-related labor force disruptions experienced by rural and urban adults, and to assess the extent to which these disparities can be explained by rural-urban differences in demographic and economic characteristics and state-level policy. Our findings run contrary to the hypothesized rural disadvantage and suggest rural labor markets have generally fared better during the pandemic than urban labor markets. We find that rural adults were less likely to report being unable to work or unable to look for work due to COVID-19. These rural advantages persist even when accounting for rural-urban differences in socioeconomic composition or state-level factors. During the early months of the pandemic, rural adults were also more often paid for missed work than urban adults, however this can be attributed to relevant socioeconomic and state-level differences between rural and urban areas

These rural advantages in labor market outcomes may reflect at least three factors. First, they may be the result of differences in the policy responses to the pandemic vis-à-vis urban areas, where restrictions were more robust. For example, rural school districts were less likely to close or go remote (Gross and Opalka 2020), which in turn may have meant that many rural parents did not have to leave work temporarily or be unable to look for work due to childcare needs unlike many urban parents. Second, the rural advantage may reflect differences in the industrial structure of rural economies that are not captured by our industry-of-employment control variables. For example, the types of jobs classified as manufacturing in rural areas (e.g., food processing) may have been more likely to be classified as essential than those in urban areas (e.g., automobile production). Third and relatedly, rural workers may have been more likely to have faced the choice of going to work or quitting. Rural workers are less likely to be unionized than their urban counterparts (Brady, Baker, and Finnigan 2013; Thiede and Slack 2017), potentially resulting in many rural workers not having the bargaining power to opt out of work during high risk times. In each of these scenarios, the apparent rural labor market advantages during the pandemic stem, perversely, from policies and conditions that have put rural populations’ health at risk and that may leave rural economies less prosperous and more precarious in the long run.

The one exception to this observed rural labor market advantage pertains to remote work—mirroring the findings of Callaghan and colleagues (2021). Urban adults were more likely to work remotely throughout the study period and the gap between rural and urban workers persisted (albeit with diminished magnitude) when accounting for compositional and state-level factors. In addition to rural-urban occupational differences, the remaining urban advantage may be explained by more prevalent home internet access in urban areas (Perrin 2019). Hence, many rural individuals would be unable to work from home even if the option was available from their employer.

Less-educated adults in both rural and urban areas experienced heightened labor force challenges relative to the general population. This population was particularly disadvantaged relative to more-educated adults in their likelihood of being unable to work, paid for missed hours, and able to work remotely. The temporary loss of income posed by this disadvantage likely put these individuals and their families in tenuous economic positions, which may have severely affected other forms of wellbeing such as household food security (Cowin et al. 2020; Morales et al. 2020). While the loss of wages or employment may be temporary for these families, the pandemic’s impacts outside of CPS measurement are likely to be long-term (Van Lancker and Parolin 2020), suggesting the need to continue to monitor how the pandemic has affected these marginalized groups.

Despite these findings, there are at least two notable cautions or limitations to the study that stem from our data. First, we rely upon self-reports of the pandemic’s labor market impacts. While other approaches for inferring impact are not necessarily better, we acknowledge that our data may be influenced by various reporting biases, such as panel conditioning or individual respondents not accurately attributing their current employment situation to COVID-19 (Halpern-Manners and Warren 2012). Second, the CPS does not provide the county of residence of all respondents, which prevents us from considering the differential impacts of county-level COVID-19 mandates and closures between rural and urban areas, as well as differences in infections and deaths. Future research on the differences in impact of COVID-19 in rural and urban areas should address these gaps through the use of alternative data sources (e.g., the American Community Survey).

The COVID-19 pandemic will have significant near- and long-term impacts, which our findings suggest will not be felt equally across society or space. As documented here, urban and rural people have experienced the pandemic quite differently over and above what can be explained by differences in socioeconomic composition and state-level policy. Contrary to what may have been expected from concerns voiced previously (Henning-Smith 2020; Paul et al. 2020; Peters 2020; Souch and Cossman 2021), we find the labor force impacts in urban areas have largely been more severe than those felt in rural areas—with the ability to work remotely being the key exception. There are many potential reasons for worse outcomes in urban America, including the pandemic’s initial peak in the nation’s major cities, more aggressive pandemic-related mandates in urban areas, differential experience of racism across urban and rural America, and the kinds of jobs worked in urban versus rural areas, among others.

These pronounced rural-urban differences highlight the necessity of avoiding one-size-fits-all COVID-19 recovery policies. Even in the most recent waves of data, non-trivial proportions of both rural and urban adults still reported being unable to work due to COVID-19—this is especially true among less-educated adults. The implication is that easing of COVID-19 public supports—including the federal expansion of unemployment insurance—could be pre-mature and would likely disproportionately affect already-marginalized populations. Of course, the pandemic continues to unfold and the general rural advantage found throughout this study may change in magnitude or direction depending on the trajectory of the outbreak and corresponding economic changes. It is essential that we continue to monitor rural and urban outcomes in concert in order to better inform and target future relief efforts.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Common to other demographic research on rural America (Brooks et al. 2020; Johnson and Lichter 2019; Thiede et al. 2018), we elect to use the terms urban and rural to refer to those living in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties, respectively.

Importantly, institutions such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) and the Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI) have produced numerous reports on the effects of COVID-19 on rural America. However, most of this work has focused on disruptions to agriculture or the spread of COVID-19 within rural counties. As such, the nature of the pandemic’s effects on rural employment overall remains a largely open question.

According to recent estimates, 34.7 percent of urban adults aged 25+ have a college education, compared to 20.2 percent of rural adults (Farrigan 2020).

Due to relative recency of research on COVID-19, adequate data on the effects of county-level mandate is not generally available.

According to the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, a county is considered metropolitan if it has either an urban center of at least 50,000 residents or is connected to another metropolitan county by at least 25% of commuting. All counties that do not meet these criteria are classified as nonmetropolitan (Office of Management and Budget 2010). Note that metropolitan and nonmetropolitan status is provided within the CPS, but the actual county of residence is not. We therefore could not include any county-level variables in our analysis.

Although an income stratification may be more desirable for this secondary analysis, we elect to use education instead because monthly income is relatively volatile and affected by the outcomes being studied.

Those who were employed, unemployed, or not in the labor force could report they were unable to work due to the pandemic during the reference period, thereby allowing for temporary bouts of being unable to work, as well as more permanent employment impacts.

Monthly estimates refer to the month in which the survey was taken, as indicated by IPUMS.

All estimates, both unadjusted and adjusted, are produced using the IPUMS-provided basic monthly person weights.

The education-stratified regression analyses match the form of these models but differ in that they each only include individuals in the education group of interest.

Households are included in the CPS for four consecutive months, off for eight months, and then included for another four consecutive months. Due to the specific time frame used in thus study, individuals can be included in the sample up to four times.

See Table A4 in the supplemental materials for a full list of groups used.

Within the CPS, industry of employment for unemployed individuals is reported in reference to their most recent job. The same is true for individuals not in the labor force unless they have not been employed in the past five years, for which they are instead coded as “industry of employment not available.”

As another way of visualizing the results, we have included plots of the marginal rural effect for each month in the supplemental materials (Fig. A1-A3).

This switch from a rural advantage in May to a disadvantage in February is largely the result of a large December to February change in rates of being paid for missed work (8.5%). In December, disparities in this outcome favored rural areas, with a rural-urban disparity of 3.0 percentage points.

References

- Adolph Christopher, Amano Kenya, Bree Bang-Jensen Nancy Fullman, and Wilkerson John. 2020. “Pandemic Politics: Timing State-Level Social Distancing Responses to COVID-19.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law (2007). doi: 10.1215/03616878-8802162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady David, Baker Regina S., and Finnigan Ryan. 2013. “When Unionization Disappears: State-Level Unionization and Working Poverty in the United States.” American Sociological Review 78(5):872–96. doi: 10.1177/0003122413501859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Scott A., Butters R. Andrew, and Fogarty Michael. 2020. “A Closer Look at the Correlation Between Google Trends and Initial Unemployment Insurance Claims.” Chicago Fed Insights. Retrieved (https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/blogs/chicago-fed-insights/2020/closer-look-google-trends-unemployment). [Google Scholar]

- Brooks Matthew M., Mueller J. Tom, and Thiede Brian C.. 2020. “County Reclassifications and Rural–Urban Mortality Disparities in the United States (1970–2018).” American Journal of Public Health 110(12):1814–16. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson Erik, Horton John J., Ozimek Adam, Rock Daniel, Sharma Garima, and TuYe Hong. 2020. “Covid-19 and Remote Work: An Early Look At Us Data.” NBER Working Paper Series (Working Paper No. 27344):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Burton Linda M., Lichter Daniel T., Baker Regina S., and Eason John M.. 2013. “Inequality, Family Processes, and Health in the ‘New’ Rural America.” American Behavioral Scientist 57(8):1128–51. doi: 10.1177/0002764213487348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan Timothy, Lueck Jennifer A., Kristin Lunz Trujillo, and Ferdinand Alva O.. 2021. “Rural and Urban Differences in COVID-19 Prevention Behaviors.” Journal of Rural Health 287–95. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day Cheeseman, Jennifer Donald Hays, and Smith Adam. 2016. “A Glance at the Age Structure and Labor Force Participation of Rural America.” U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved (https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2016/12/a_glance_at_the_age.html). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Kent Jason G., Sun Yue, and Monnat Shannon M.. 2020. “COVID-19 Death Rates Are Higher in Rural Counties With Larger Shares of Blacks and Hispanics.” Journal of Rural Health 36(4):602–8. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Seung Jin, Jun Yeong Lee, and John Winters. 2020. “Employment Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic across Metropolitan Status and Size.” IZA Discussion Paper (No. 13468):1–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin Rebecca L., Martin Hal, and Stevens Clare B.. 2020. “Measuring Evictions during the COVID-19 Crisis.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland July:1–9. doi: 10.26509/frbc-cd-20200717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daly Mary C., Buckman Shelby R., and Seitelman Lily M.. 2020. “The Unequal Impact of COVID-19: Why Education Matters.” The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter 2020(17):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dias Felipe A. 2021. “The Racial Gap in Employment and Layoffs during COVID-19 in the United States: A Visualization.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 7(1):1–3. doi: 10.1177/2378023120988397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobis Elizabeth A., and David McGranahan. 2021. “Rural Death Rates from COVID-19 Surpassed Urban Death Rates in Early September 2020.” Economic Research Service. Retrieved (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=100740). [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez Diana, and Goldstein Adam. 2020. “COVID-19’s Socioeconomic Impact on Low-Income Benefit Recipients: Early Evidence from Tracking Surveys.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 6:1–17. doi: 10.1177/2378023120970794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrigan Tracey. 2020. “Rural Education.” Economic Research Service. Retrieved (https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/employment-education/rural-education/#:∼:text=Between 2000 and 2018%2C the,15 percent to 20 percent.). [Google Scholar]

- Flood Sarah, King Miriam, Rodgers Renae, Ruggles Steven, and Warren J. Robert. 2021. “Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 8.0 [Dataset]. Minnesapolis, MN: IPUMS.” doi: 10.18128/D030.V8.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow Nina, and Brown David L.. 2012. “Rural Ageing in the United States: Trends and Contexts.” Journal of Rural Studies 28(4):422–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zivin Graff, Joshua, and Nicholas Sanders. 2020. “The Spread of COVID-19 Shows the Importance of Policy Coordination.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(52):32842–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022897117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross Betheny, and Opalka Alice. 2020. “Too Many Schools Leave Learning to Chance During the Pandemic.” Center on Reinventing Public Education (June):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Manners Andrew, and John Robert Warren. 2012. “Panel Conditioning in Longitudinal Studies: Evidence From Labor Force Items in the Current Population Survey.” Demography 49(4):1499–1519. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauer Mathew E., and Santos-Lozada Alexis R.. 2021. “Differential Privacy in the 2020 Census Will Distort COVID-19 Rates.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 7:1–6. doi: 10.1177/2378023121994014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Headd Brian. 2010. “An Analysis of Small Business and Jobs.” Small Business: Economic and Development Issues (March):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith Carrie. 2020. “The Unique Impact of COVID-19 on Older Adults in Rural Areas.” Journal of Aging and Social Policy 32(4–5):396–402. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1770036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith Carrie, Tuttle Mariana, and Kozhimannil Katy B.. 2021. “Unequal Distribution of COVID-19 Risk Among Rural Residents by Race and Ethnicity.” Journal of Rural Health 37(1):224–26. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Kenneth M. 2020. “As Births Diminish and Deaths Increase, Natural Decrease Becomes More Widespread in Rural America.” Rural Sociology 85(4):1045–58. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Kenneth M., and Lichter Daniel T.. 2019. “Rural Depopulation: Growth and Decline Processes over the Past Century.” Rural Sociology 0(0):1–25. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karim Saleema A., and Hsueh Fen Chen. 2021. “Deaths From COVID-19 in Rural, Micropolitan, and Metropolitan Areas: A County-Level Comparison.” Journal of Rural Health 37(1):124–32. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpman Michael, Zuckerman Stephen, Gonzalez Dulce, and Kenney Genevieve M.. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Straining Families’ Abilities to Afford Basic Needs: Low-Income and Hispanic Families the Hardest Hit.” Urban Instiute: Health Policy Center 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kesler Christel, and Bash Sarah. 2021. “A Growing Educational Divide in the COVID-19 Economy Is Especially Pronounced among Parents.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 7:1–3. doi: 10.1177/2378023120979804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani Hari Vishal, Pillai Sneha S., Zehra Mishghan, Sharma Ishita, and Sodhi Komal. 2020. “Systematic Review of Clinical Insights into Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic: Persisting Challenges in U.S. Rural Population.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(12):1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancker Van, Wim, and Zachary Parolin. 2020. “COVID-19, School Closures, and Child Poverty: A Social Crisis in the Making.” The Lancet Public Health 5(5):e243–44. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Barrett A., and Sharp Gregory. 2017. “Ethnoracial Diversity across the Rural-Urban Continuum.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 672(1):26–45. doi: 10.1177/0002716217708560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T. 2012. “Immigration and the New Racial Diversity in Rural America.” Rural Sociology 77(1):3–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2012.00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., and Brown David L.. 2011. “Rural America in an Urban Society: Changing Spatial and Social Boundaries.” Annual Review of Sociology 37(1):565–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., and Ziliak James P.. 2017. “The Rural-Urban Interface: New Patterns of Spatial Interdependence and Inequality in America.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 672(1):6–25. doi: 10.1177/0002716217714180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Ge, Zhang Tonglin, Zhang Ying, and Wang Quanyi. 2021. “Statewide Stay-at-Home Directives on the Spread of COVID-19 in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Counties in the United States.” Journal of Rural Health 37(1):222–23. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Ken-hou, Carolina Aragão, and Guillermo Dominguez. 2021. “Firm Size and Employment during the Pandemic.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 7(1):1–16. doi: 10.1177/2378023121992601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthewman Steve, and Huppatz Kate. 2020. “A Sociology of Covid-19.” Journal of Sociology 56(4):675–83. doi: 10.1177/1440783320939416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin Diane K., and Coleman-Jensen Alisha J.. 2014. “Economic Restructing and Family Structure Change, 1980 to 2000.” Pp. 105–23 in Economic Restructuring and Family Well-Being in Rural America, edited by Smith KE and Tickamyer AR. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Danielle Xiaodan, Stephanie Alexandra Morales, and Tyler Fox Beltran. 2020. “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Household Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationally Representative Study.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00892-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J. Tom. 2020. “Defining Dependence: The Natural Resource Community Typology.” Rural Sociology 1–41. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J. Tom, Kathryn McConnell, Paul Berne Burow, Katie Pofahl, Merdjanoff Alexis A., and Justin Farrell. 2021. “Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Rural America.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(1):1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019378118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Management and Budget. 2010. “2010 Standard for Delineating Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas; Notice.” Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Executive Office of the President. (2010–15605):37245–52. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Rajib, Arif Ahmed A., Adeyemi Oluwaseun, Ghosh Subhanwita, and Han Dan. 2020. “Progression of COVID-19 From Urban to Rural Areas in the United States: A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Prevalence Rates.” Journal of Rural Health 36(4):591–601. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pender John. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Rural America.” Economic Research Service. Retrieved (https://www.ers.usda.gov/covid-19/rural-america/). [Google Scholar]

- Perrin Andrew. 2019. “Digital Gap between Rural and Nonrural America Persists.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved (https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/31/digital-gap-between-rural-and-nonrural-america-persists/). [Google Scholar]

- Peters David J. 2020. “Community Susceptibility and Resiliency to COVID-19 Across the Rural-Urban Continuum in the United States.” Journal of Rural Health 36(3):446–56. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum Betty, and North Carol S.. 2020. “Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic.” New England Journal of Medicine 383(6):510–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyakova Maria, Kocks Geoffrey, Udalova Victoria, and Finkelstein Amy. 2020. “Initial Economic Damage from the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States Is More Widespread across Ages and Geographies than Initial Mortality Impacts.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117(45):27934–39. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014279117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raifman Julia, Nocka Kristen, Jones David, Bor Jacob, Lipson Sarah, Jay Johathan, and Chan Phillip. 2021. “COVID-19 US State Policy Database.” Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor]. [Google Scholar]

- Singh Gopal K., and Siahpush Mohammad. 2014. “Widening Rural-Urban Disparities in Life Expectancy, U.S., 1969–2009.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 46(2):e19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack Tim, Thiede Brian C., and Jensen Leif. 2019. “Race, Residence, and Underemployment: Fifty Years in Comparative Perspective, 1968–2017.” Rural Sociology 0(0):1–41. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souch Jacob M., and Cossman Jeralynn S.. 2021. “A Commentary on Rural‐Urban Disparities in COVID‐19 Testing Rates per 100,000 and Risk Factors.” The Journal of Rural Health 37(1):188–90. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainback Kevin, Hearne Brittany N., and Trieu Monica M.. 2020. “COVID-19 and the 24/7 News Cycle: Does COVID-19 News Exposure Affect Mental Health?” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 6:1–15. doi: 10.1177/2378023120969339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Charles A., Boulos Christopher, and Almond Douglas. 2020. “Livestock Plants and COVID-19 Transmission.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117(50):31706–15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010115117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiede Brian C., Lichter Daniel T., and Slack Tim. 2018. “Working, but Poor: The Good Life in Rural America?” Journal of Rural Studies 59:183–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thiede Brian C., and Slack Tim. 2017. “The Old Versus the New Economies and Their Impacts.” in Rural Poverty in the United States, edited by Tickamyer AR, Sherman J, and Warlick J. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. “Design and Methodology: Current Population Survey--America’s Source for Labor Force Data.” U.S. Census Bureau (Technical Paper 77):1–175. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. “Industry and Occupation Classification.” (January). Retrieved (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/technical-documentation/methodology/industry-and-occupation-classification.html). [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich Fred, and Mueller Keith. 2021. “Pharmacy Vaccination Service Availability in Nonmetropolitan Counties (V3).” RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis: Rural Data Brief (2020–10). doi: https://rupri.org/wp-content/uploads/COVID-Pharmacy-Brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Vias Alexander C. 2012. “Perspectives on U.S. Rural Labor Markets in the First Decade of the Twenty-First Century.” Pp. 273–91 in International Handbook of Rural Demography, edited by Kulcsár LJ and Curtis KJ. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Ward Paul R. 2020. “A Sociology of the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Commentary and Research Agenda for Sociologists.” Journal of Sociology 56(4):726–35. doi: 10.1177/1440783320939682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley-Field Elizabeth, Garcia Sarah, Leider Jonathon P., Robertson Christopher, and Wurtz Rebecca. 2020. “Racial Disparities in COVID-19 and Excess Mortality in Minnesota.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 6:1–4. doi: 10.1177/2378023120980918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.