Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Lipedema exhibits excessive lower-extremity subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) deposition, that is frequently misidentified as obesity until lymphedema presents. MR lymphangiography may have relevance to distinguish lipedema from obesity or lymphedema.

HYPOTHESIS:

Hyperintensity profiles on 3-T MR lymphangiography can identify distinct features consistent with SAT edema in participants with lipedema.

STUDY TYPE:

Prospective cross-sectional study.

SUBJECTS:

Participants (48 females, matched for age [mean=44.8years]) with lipedema (n=14), lipedema with lymphedema (LWL, n=12), cancer treatment-related lymphedema (lymphedema, n=8), and controls without these conditions (n=14).

FIELD STRENGTH/SEQUENCE:

3-T MR lymphangiography (non-tracer 3D turbo-spin-echo).

ASSESSMENT:

Review of lymphangiograms in lower extremities by three radiologists was performed independently. Spatial patterns of hyperintense signal within the SAT were scored for extravascular (focal, diffuse, or not apparent) and vascular (linear, dilated, or not apparent) image features.

STATISTICAL TESTS:

Inter-reader reliability was computed using Fleiss Kappa. Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the proportion of image features between–study groups. Multinomial logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between image features and study groups. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of SAT extravascular and vascular features was reported in groups compared to lipedema. The threshold of statistical significance was p<0.05.

RESULTS:

Reliable agreement was demonstrated between three independent, blinded reviewers (p<0.001). The frequency of SAT hyperintensities in participants with lipedema (36% focal, 36% diffuse), LWL (42% focal, 33% diffuse), lymphedema (62% focal, 38% diffuse), and controls (43% focal, 0% diffuse) was significantly distinct. Compared with lipedema, SAT hyperintensities were less frequent in controls (focal: OR=0.63, CI=0.11-3.41; diffuse: OR=0.05, CI=0.00-1.27), similar in LWL (focal: OR=1.29, CI=0.19-8.89; diffuse: OR=1.05, CI=0.15-7.61), and more frequent in lymphedema (focal: OR = 9.00, CI=0.30-274.12; diffuse: OR = 5.73, CI=0.18-186.84).

DATA CONCLUSION:

Noninvasive MR lymphangiography identifies distinct signal patterns indicating SAT edema and lymphatic load in participants with lipedema.

Keywords: lymphangiography, lymphedema, lipedema, lipoedema, obesity

Introduction

The diagnosis and treatment of lipedema have both been hindered by the combination of a similar external appearance to obesity and lymphedema, as well as limited appreciation in medicine(1). Internally, legs affected by lipedema contain an excessive volume of subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) compared to body mass index (BMI)-matched controls as indicated by MRI(2,3). Importantly, leg SAT deposition due to lipedema is refractory to dieting, exercise, or even bariatric surgery, resulting in minimal impact on leg girth(4). Alternative mechanisms for lipedema SAT deposition with evidence of fluid retention implicate disrupted lymphatic homeostasis, although the etiology of lipedema, in general, remains an active area of research(5).

One of the fundamental limitations in lipedema management is a lack of specific, objective biomarkers(6). Currently, clinical examination is required to distinguish lipedema from primary or secondary lymphedema or obesity at specialized centers(6). Classically, extremities affected by lipedema often present with somatic pain and easy bruising, and demonstrate morphological changes such as SAT dimpling and ankle cuffing while the feet are generally spared(6). Patients with lipedema may also develop overt secondary lymphedema (lipedema with lymphedema, LWL)(7). Early detection of tissue edema in patients with lipedema, even in the absence of overt clinical manifestations of lymphedema, would serve as a much needed strategy to potentially offer prophylactic therapies that may delay or prevent lymphedema onset in lipedema (8,9).

Noninvasive MR lymphangiography has demonstrated the ability to identify regions of edema in diseases with known lymphatic etiology such as cancer-related lymphedema following lymph node dissection(10,11). This methodology is based on heavily T2-weighted turbo-spin-echo (TSE) sequences that exploit the long T2-relaxation time of lymph (T2=610 ms) compared to blood and muscle (T2=30-120 ms)(12). Furthermore, a multi-pulse refocusing train that dephases fast flowing blood signal while maintaining slower flowing signal from lymphatic fluid is used to increase contrast between lymphatic fluid and surrounding tissues(10).

Imaging review of 3-T- MR lymphangiography in individuals with unilateral cancer treatment-related lymphedema revealed lateralized hyperintensities consistent with tissue edema and lymph stasis in affected limbs(10). Similar imaging patterns are expected in lipedema SAT where microaneurysms, leaky lymphatic vessels, and slow transport dynamics have been reported using elegant tracer-based MRI or optical modalities(13-15).

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to apply clinically feasible noninvasive 3-T MR lymphangiography, with sensitivity to edema in diseases with known lymphatic failure, to evaluate the topography of hyperintense signal patterns in participants who meet clinical criteria for lipedema, LWL, cancer treatment-related leg lymphedema, and controls matched for age and BMI without these conditions. Our hypothesis was that spatial patterns of signal hyperintensities on lymphangiograms are unique among study groups consisting of participants who meet clinical criteria for lipedema, LWL, cancer treatment-related leg lymphedema, or control participants without these diseases, and could provide imaging evidence of SAT edema and disrupted lymphatic homeostasis in lipedema.

Materials and Methods

This prospective cross-sectional study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed written consent.

Study cohort

Participants were recruited from the Vanderbilt University Medical Center lymphedema clinic and lipedema database, patient support groups, and campus-wide advertisements. Participants were screened for their study eligibility and placed in their assigned cohort based on their medical documentation and physical evaluation by a Lymphology Association of North America (LANA) certified lymphedema therapist (PMCD; experience=19 years).

Measurements of height and weight were recorded to assess BMI. Each participant’s experience of generalized leg pain was quantified using a visual analogue scale (VAS: 0-100). Participants with lipedema (Figure 1) met all primary criteria (external appearance matches lipedema stage 1-3) and one or more secondary criteria (lower extremity pain, family history of lipedema, joint hypermobility, or easy leg bruising)(6). Participants with cancer treatment-related lymphedema (hereafter referred to as lymphedema) had a medical history of cancer and lymphedema following lymph node resection or dissection of the inguinal or pelvic nodes of at least one lower extremity. Participants with lipedema and/or lymphedema were evaluated for lymphedema stage following criteria of the International Society of Lymphology(16).

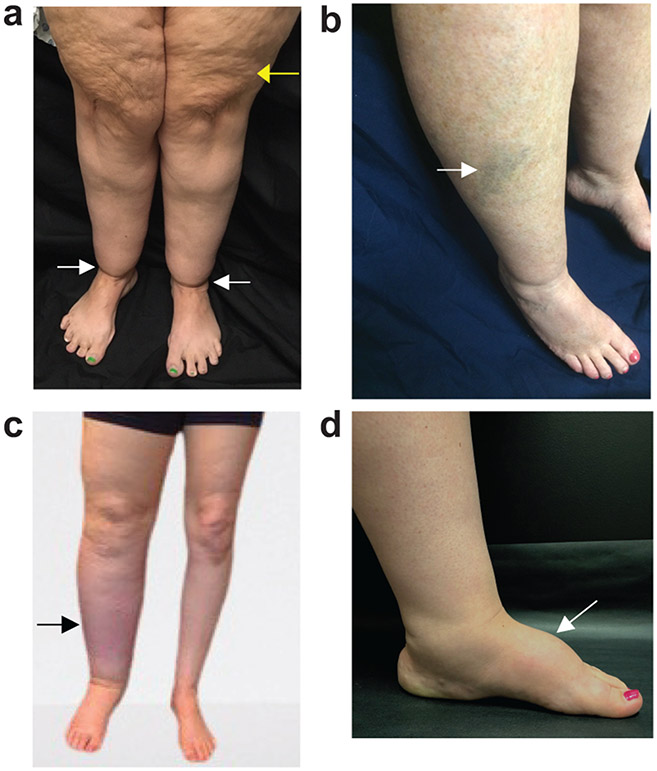

Figure 1. Lower-extremity clinical features of lipedema and lymphedema.

a) Lipedema presents with skin and subcutaneous abnormalities including skin dimpling in stage 2 (yellow arrow) and ankle cuffing from adipose deposition in type 3 sparing the feet (white arrow). b) Easy-bruising commonly accompanies lipedema (arrow). c) Secondary leg lymphedema due to cancer therapies often presents with asymmetrical swelling of the limbs and may only involve one limb (arrow). d) Dorsal foot swelling is characteristic of primary or secondary lymphedema (arrow).

Participants without lipedema or lymphedema were enrolled as healthy controls with similar age (range for inclusion=20 to 70 years of age) and BMI (range for inclusion=18 to 40 kg/m2). Only female participants were recruited, given that lipedema has a strong female predilection(6). Exclusion criteria were uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, current skin infections, or other signs of acute inflammation identified at the time of physical exam.

MR lymphangiography

MRI and MR lymphangiography were performed on a 3-T-scanner (dStream, Philips Ingenia; Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Scans were acquired in the supine feet-first position using phased-array reception and dual-channel body coil transmission.

Whole-body chemical-shift-encoded MRI was performed in six stacked acquisitions from the crown of head to ankles using the body coil and the following protocol parameters: three-dimensional (3D) spoiled gradient echo two-point Dixon, repetition time/echo time TR/TE1/TE2=3.8/2.39/4.77 ms, flip angle=10 degrees, each stack’s field of view (FOV)=530 x 348 x 221 mm3, spatial resolution=2 x 1.4 x 2.6 mm3, cumulative scan duration=6 min.

T1-weighted anatomical imaging was acquired in the calf with the following parameters: two-dimensional (2D) multi-shot TSE readout, TR/TE=992/15 ms, FOV=180 x 180 mm2, slice thickness=5.5 mm, number of slices=31, spatial resolution=0.5 x 0.5 mm2, scan duration=5 min 35s.

Non-tracer MR lymphangiography was acquired in the distal lower extremities bilaterally from popliteal fossa to the top of the malleolus with the following parameters: 3D TSE readout, TR/TE=3000/600 ms, TSE factor=65, constant refocusing angle=110 degrees, FOV=445 x 240 x 180 mm3, spatial resolution=1.39 x 1.39 x 3 mm3, oversampling=120 mm in anterior/posterior direction, fat suppression using spectral presaturation with inversion recovery (SPIR) at 190 Hz absolute resonance frequency of fat species which is visually checked during scan pre-check, two 60 mm thick rest slabs placed 20 mm inferior and superior to the imaging volume, number of signal acquisitions=2, scan duration=10 min 51s.

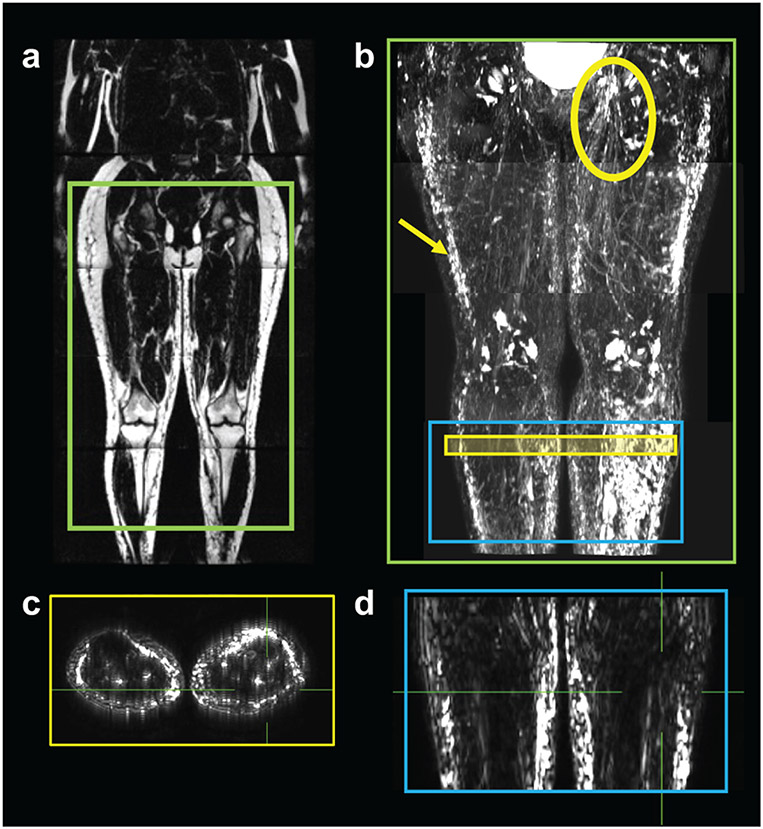

The imaging scheme and example images from MRI and MR lymphangiography acquisitions are presented in Figure 2. For demonstration purposes, MR lymphangiography was acquired in four stacked acquisitions in a participant with lipedema (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Imaging protocol to evaluate MR lymphangiography of the lower extremities.

a) Example MRI is displayed in a whole-body manner in a patient with lipedema with lymphedema (age=44 years, BMI=27.1 kg/m2, lipedema stage 2 and lymphedema stage 2). Chemical-shift-encoded fat-weighted MRI is displayed for anatomical reference. b) MR lymphangiography was acquired in this participant in the pelvis, thigh, knee, and calf regions. Acquisitions are rendered stacked as a maximum-intensity-projection (green box). Hyperintensities in the subcutaneous tissue (arrow) and inguinal lymph node territories (circle) are observed, consistent with lymphatic anatomy and the patient’s symptomatology of bilateral lymphedema. MR lymphangiography was acquired at the level of the calf (blue box) for all participants. c) Transverse and d) coronal source images were viewed in orthogonal planes to evaluate image features (case example given: extravascular focal, vascular dilated).

Image scoring system and analysis

The noninvasive MR lymphangiography images were presented to three radiologists (initials, years experience: YL, 15 years; GH, 8 years; KG, 3 years). Radiologists performed independent, blinded review of all cases. Axial source images and orthogonal planes were viewed in Horos™ (version 3.3; Horos Project, https://horosproject.org/), and window/level settings were modified to achieve a null background (Figure 2c-d). A scoring system was utilized to describe signal hyperintensities in the SAT where distinct features are hypothesized between study cohorts. Each case was assigned one extravascular (focal, diffuse, or not apparent) and one vascular (linear, dilated, or not apparent) image feature (Table 1). Assigned features were scored numerically (present=1, absent=0).

Table 1.

Image features describe the spatial extent of SAT hyperintensities on non-tracer 3.0T MR lymphangiography.

| Extravascular features: |

|---|

| Focal: localized hyperintensities affecting a portion of the region; noncircumferential in the SAT region |

| Diffuse: extensive hyperintensities in the region; circumferential in the SAT region |

| Not apparent: signal is scant, normointense or hypointense approaching background |

| Vascular features: |

| Linear: hyperintensities that traverse multiple slices in tubes and channels are linear and consistent in caliber |

| Dilated: hyperintensities that traverse multiple slices in tubes and channels are nonlinear, dilated, ectatic, or tortuous |

| Not apparent: tubes and channels are thin, scant, or normointense or hypointense approaching background |

SAT: subcutaneous adipose tissue

Imaging features describe signal patterns on heavily T2-weighted lymphangiography according to clinically standard practice(17). Signal hyperintensities on MR lymphangiography represent long T2-weighted slow-moving fluid in the interstitium and lymphatic vasculature, while blood-water signal is effectively null, as simulated previously(10). Extravascular focal hyperintensities represent tissue edema in the interstitium isolated to a portion of the region of interest, whereas diffuse hyperintensities are circumferential or more spatially extensive, indicating a greater area of involvement(17). Vascular signal is differentiated from extravascular signal when hyperintensities traverse multiple, sequential axial slices which may be confirmed on orthogonal views(10). Vascular hyperintensities represent apparent fluid in tubular lymphatic channels, which can exhibit conspicuous linear profiles when lymph is present, and dilated caliber or tortuosity indicating increased lymphatic load(18).

T1-weighted images were used for visualization purposes of anatomy in reference to MR lymphangiography. Whole-body chemical-shift-encoded MRI was acquired for visualization purposes. Chemical-shift-encoded MRI fat-weighted and water-weighted images at the widest part of the calf were used to evaluate leg tissue composition metrics of volumetric fat/water (ratio), circumference (cm), SAT area (mm2), and muscle area (mm2) following previously published methods2. Image analyses were performed in MATLAB (R.2018b; MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R, version 3.6.3 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, frequency and percentages for categorical variables) were summarized for demographics and clinical characteristics by the study groups, (i.e., lipedema, LWL, lymphedema, and controls). Continuous measure in this study include age, BMI, leg pain, fat/water, circumference, SAT area, and muscle area. The continuous variables between study groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests. Categorical measures in this study include lipedema stage, lymphedema stage, and image features consisting of extravascular (focal, diffuse, or not-apparent) and vascular (linear, dilated, or not-apparent) features. The difference in proportion of categorical variable between study groups was assessed by Fisher’s exact test. The inter-reader reliability (IRR) using Fleiss Kappa evaluated the reliability of agreement among three radiologists who assigned three categorical ratings for extravascular and vascular features, and 95% confidence intervals are reported based on normal approximation. The majority score is reported, and in the few participants where each rater provided a different score, the score from the senior radiologist is reported.

To further assess the relationship between the dependent variables (image features) and independent variable (study groups), multinomial response models were conducted using the Poisson trick via the Poisson log-linear model for more than two levels of the dependent variable (model 1: SAT extravascular signal: 0=not apparent, 1=focal, 2=diffuse; model 2: SAT vascular signal: 0=not apparent, 1=linear, 2=dilated). The maximum penalized likelihood with powers of the Jeffreys prior as the penalty was used to reduce the bias in parametric estimation for solving the rare-event counts(19). The likelihood ratio (LR) test was used to determine the goodness-of-fit between the full model including intercept and independent (study group) variables and the reduced model, which contained intercept only. The study groups (k=4, categorical levels) would be transformed into three (k-1) dummy variables (control, LWL, and lymphedema) where lipedema was the reference group. Post-hoc paired group comparisons of the likelihood of each image feature among a group compared to lipedema are reported as the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The odds of focal or diffuse (or the odds of linear or dilated) relative to the baseline (e.g., 0=not apparent) were calculated based on the multinomial model (i.e., fitting two logistic models simultaneously). The p-value of Wald test was used for testing the null hypothesis that the coefficient of each dummy variable was equal to zero in the model.

Statistical interpretation.

The interpretation of the Fleiss Kappa is based on Cohen’s suggestion: 0.21 to 0.40=fair agreement, and 0.01 to 0.20=slight agreement for two readers and two categories. Note that increased number of categories or readers will reduce Kappa value (20). The OR<1 indicates a feature is less likely in the comparison group than lipedema, and OR>1 indicates it is more likely than in lipedema. The threshold of statistical significance was defined as two-sided p<0.05 for all tests.

Results

Forty-eight females were included in this study (mean age=44.8 years; age range=23 to 68 years; mean BMI=29.6 kg/m2; BMI range=21.3 to 39.5 kg/m2) (Table 2). Cohorts consisted of participants with lipedema (n=14), LWL (i.e., met clinical criteria for lipedema and lymphedema; n=12), lymphedema (n=8), and female controls without these conditions (n=14). Participants with lipedema or LWL had typical disease characteristics of elevated leg pain, and MRI-based metrics of increased leg fat/water volume ratio, circumference, and SAT area compared to the control and lymphedema cohorts (Table 2). Clinical stages of lipedema and lymphedema are also provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohorts

| Characteristic | Control (n = 14) |

Lipedema (n = 14) |

Lipedema with Lymphedema (n = 12) |

Lymphedema (n = 8) |

*P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 42.8 ± 13.2 (23.0, 68.0) | 41.9 ± 10.7 (23.0, 60.0) | 44.5 ± 9.8 (24.0, 58.0) | 54.0 ± 6.4 (44.0, 64.0) | 0.07 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.8 ± 4.4 (21.9, 38.5) | 30.5 ± 4.5 (21.3, 34.9) | 30.3 ± 4.3 (23.7, 36.9) | 28.3 ± 6.3 (21.4, 39.5) | 0.46 |

| Pain, VAS | 3.7 ± 6.7 (0.0, 25.0) | 43.5 ± 22.4 (2.0, 71.0) | 46.8 ± 24.3 (0.0, 75.0) | 28.2 ± 26.9 (0.0, 90.0) | <0.001 |

| Leg fat/water, ratio | 0.6 ± 0.2 (0.2, 1.0) | 1.1 ± 0.4 (0.5, 1.9) | 0.9 ± 0.3 (0.4, 1.6) | 0.6 ± 0.2 (0.4, 0.9) | <0.001 |

| Leg circumference, cm | 39.1 ± 4.2 (31.8, 45.9) | 44.0 ± 3.5 (39.1, 49.0) | 42.3 ± 3.8 (36.9, 49.3) | 39.6 ± 4.9 (33.5, 46.0) | 0.03 |

| Leg SAT area, mm2 | 3,974.9 ± 1,751.3 (1,268.0, 6,715.0) | 7,062.8 ± 2,353.2 (3,492.0, 11,813.0) | 5,749.8 ± 2,177.8 (3,149.0, 9,252.0) | 4,836.5 ± 2,388.8 (2,470.0, 8,459.0) | 0.009 |

| Leg muscle area, mm2 | 6,907.7 ± 1,005.8 (4,962.0, 8,592.0) | 6,719.6 ± 909.4 (5,159.0, 8,193.0) | 6,819.6 ± 1,080.4 (5,403.0, 8,621.0) | 5,973.6 ± 959.5 (4,834.0, 7,721.0) | 0.2 |

| Values reported as mean ± standard deviation (range) | |||||

| *Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, significance level p<0.05 | |||||

| VAS: visual analogue scale | |||||

| Characteristic | Control (n = 14) |

Lipedema (n = 14) |

Lipedema with lymphedema (n = 12) |

Lymphedema (n = 8) |

†P- value |

| Lipedema Stage | 0.13 | ||||

| 1 | N/A | 3 (21.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | N/A | |

| 2 | N/A | 10 (71.4%) | 6 (50.0%) | N/A | |

| 3 | N/A | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (41.7%) | N/A | |

| Lymphedema Stage | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 | N/A | 0 (0%) | 7 (58.3%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| 2 | N/A | 0 (0%) | 5 (41.7%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| 3 | N/A | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (50.0%) | |

| Values reported as (n)umber of subjects (%) | |||||

| N/A reported as not applicable | |||||

| †Fisher's exact test, significance level p<0.05 | |||||

Reliable agreement was demonstrated between three independent, blinded reviewers (p<0.001). The IRR of subcutaneous features overall (present, or absent) was in fair agreement(Kappa=0.31; CI=0.15, 0.48). The IRR of subcutaneous extravascular features (not apparent, focal, or diffuse) indicates fair agreement(Kappa=0.34; CI=0.23, 0.46). The IRR of subcutaneous vascular features (not apparent, linear, or dilated) indicates slight agreement(Kappa=0.14; CI=0.03, 0.26).

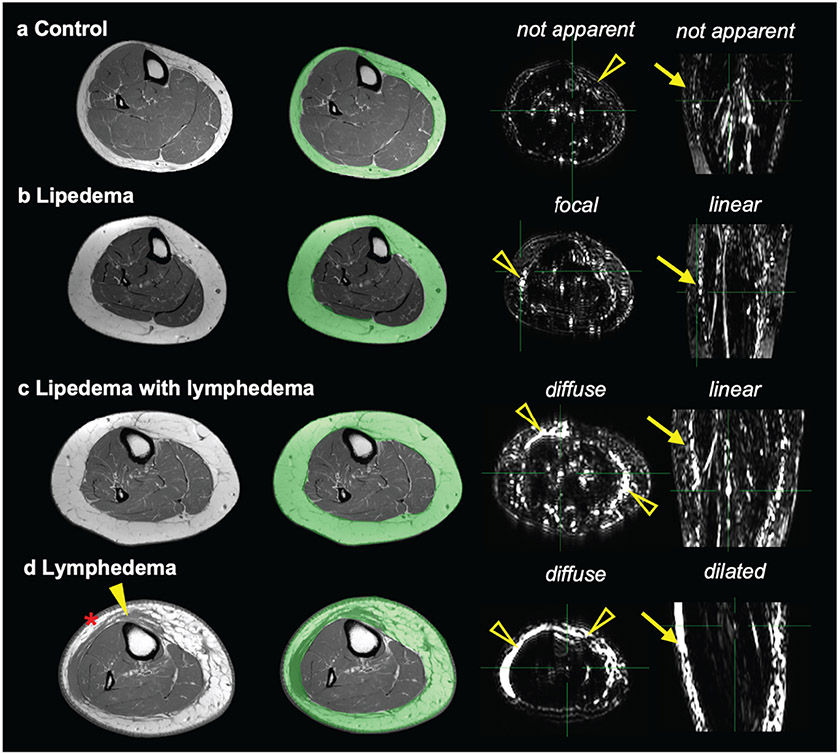

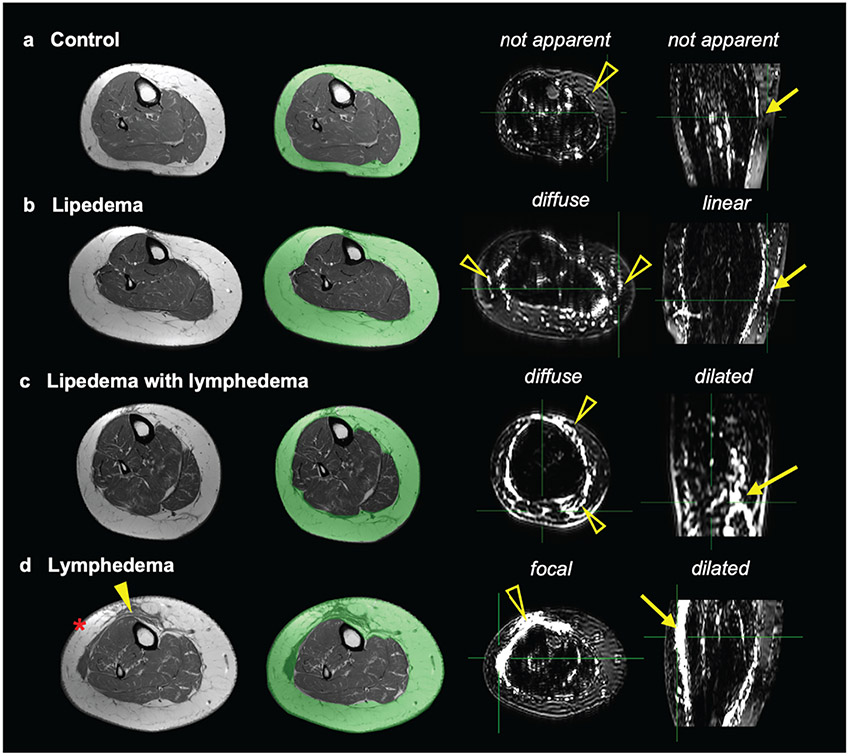

Case examples of non-tracer MR lymphangiography that exhibit representative features of study cohorts in the SAT are presented (Figure 3). All case examples in Figure 3 exhibited BMI<30 kg/m2, and yet the legs of patients with lipedema, LWL, or lymphedema exhibit thick SAT with evident hyperintensities on MR lymphangiography. Case examples in participants with BMI>30 kg/m2 are provided in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Representative MR lymphangiography features in subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) in participants with BMI<30 kg/m2.

Lower-extremity T1-weighted images show the SAT region (green overlay). Adjacent images are MR lymphangiography axial-source and coronal-MIP (maximum intensity projection) images. Cases are presented with annotated extravascular (open arrowheads) and vascular (arrows) signal patterns on MR lymphangiography for participants: a) female control (40 y/o, BMI=29.2 kg/m2, calf-circumference=41 cm), b) lipedema (23 y/o, 22.7 kg/m2, calf-circumference=40 cm, lipedema stage 1), c) lipedema with lymphedema (46 y/o, 24.9 kg/m2, calf-circumference=43 cm, lipedema stage 2, lymphedema stage 1), and d) cancer treatment-related lymphedema (60 y/o, 24.8 kg/m2, calf-circumference=37 cm, lymphedema stage 3). The participant with cancer-related lymphedema displays on T1-weighted imaging thick skin (asterisk) and band-like soft tissue (closed arrowhead) within the SAT.

Figure 4. Representative MR lymphangiography features in the subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) in participants with BMI>30 kg/m2.

Lower-extremity T1-weighted images show the SAT region (green overlay). Adjacent images are MR lymphangiography axial-source and coronal-MIP (maximum intensity projection) images. Cases are presented with annotated extravascular (open arrowheads) and vascular (arrows) signal patterns on MR lymphangiography for participants: a) female control (61 y/o, BMI=31.4 kg/m2, calf-circumference=41 cm), b) lipedema (34 y/o, BMI=34.1 kg/m2, calf-circumference=49 cm, lipedema stage 2), c) lipedema with lymphedema (48 y/o, BMI=36.3 kg/m2, calf-circumference=42 cm, lipedema stage 3, lymphedema stage 2), and d) cancer treatment-related lymphedema (age=64 years, BMI=39.5 kg/m2, calf circumference=46 cm, lymphedema stage 3). The participant with cancer-related lymphedema displays on T1-weighted imaging thick skin (asterisk) and band-like soft tissue (closed arrowhead) within the SAT.

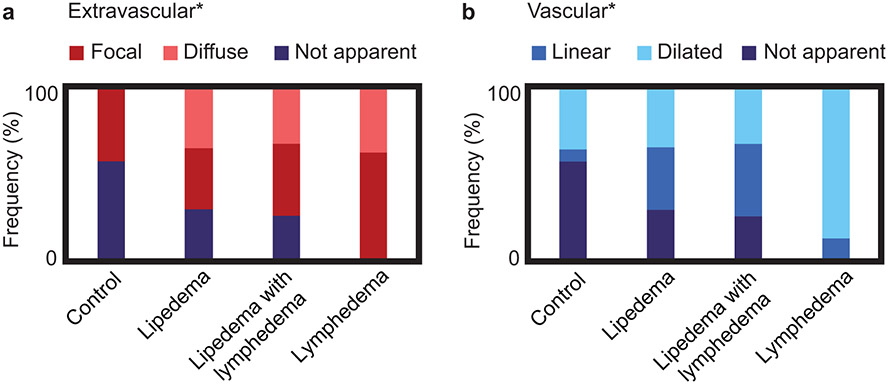

The frequency of imaging features in the SAT are reported in Figure 5. Notably, SAT diffuse hyperintensities were only observed in participants with lipedema, LWL, or lymphedema; in contrast, SAT hyperintensities were not apparent in the majority of controls. Patterns of SAT extravascular hyperintensities were significantly distinct among study cohorts with lipedema (36% focal, 36% diffuse), LWL (42% focal, 33% diffuse), lymphedema (62% focal, 38% diffuse), and controls (43% focal, 0% diffuse) (Figure 5a). Patterns of SAT vascular hyperintensities were also significantly distinct among study cohorts with lipedema (36% linear, 36% dilated), LWL (42% linear, 33% dilated), lymphedema (12% linear, 88% dilated), and controls (7% linear, 36% dilated) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Subcutaneous hyperintense signal patterns were scored on MR lymphangiography in study groups for a) extravascular (focal, diffuse, or not apparent) and b) vascular (linear, dilated, or not apparent) image features. The frequency (%) of image features present within each group is represented by the length of colorbars, and the sum of frequencies equals 100% in each group because all cases were scored. Notably, all image features had similar frequency between lipedema cohorts (i.e. with or without lymphedema). Image features were significantly associated with study group (Fisher’s exact test, *two-sided p<0.05 defined as the level of statistical significance).

SAT extravascular hyperintensities were less likely in controls than lipedema for focal (OR=0.63, CI=0.11-3.41) and diffuse (OR=0.05, CI=0.00-1.27) signal patterns (Table 3). SAT extravascular hyperintensities were similarly observed in LWL (focal: OR=1.29, CI=0.19-8.89; diffuse: OR=1.05, CI=0.15-7.61) and more likely observed in lymphedema (focal: OR=9.00, CI=0.30-274.12; diffuse: OR=5.73, CI=0.18-186.84) compared to participants with lipedema (Table 3). SAT vascular hyperintensities were less likely in controls than lipedema (linear: OR=0.14, CI=0.02-1.37; dilated: OR=0.53, CI=0.09-2.99). SAT vascular hyperintensities were similarly observed in LWL (linear: OR=1.29, CI=0.19=8.89; dilated: OR=1.05, CI=0.15=7.61) and more likely observed in lymphedema (linear: OR=2.45, CI=0.06-101.89; dilated: OR=12.27, CI=0.42-361.83) compared to participants with lipedema.

Table 3.

The relationship between image features and study group.

| Control vs. Lipedema |

Lipedema with lymphedema vs. Lipedema |

Lymphedema vs. Lipedema |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Feature | OR (CI) | OR (CI) | OR (CI) | |

| *Extravascular | focal | 0.63 (0.11, 3.41) | 1.29 (0.19, 8.89) | 9.00 (0.30, 274.12) |

| diffuse | 0.05 (0.00, 1.27) | 1.05 (0.15, 7.61) | 5.73 (0.18, 186.84) | |

| †Vascular | linear | 0.14 (0.02, 1.37) | 1.29 (0.19, 8.89) | 2.45 (0.06, 101.89) |

| dilated | 0.53 (0.09, 2.99) | 1.05 (0.15, 7.61) | 12.27 (0.42, 361.83) | |

Multinomial logistic regression: focal, diffuse, or not apparent as the baseline category

Multinomial logistic regression: linear, dilated, or not apparent as the baseline category

OR(CI) reported as odds ratio with 95% confidence interval

All models demonstrated a goodness-of-fit likelihood ratio test p<0.05

Discussion

We report distinct image patterns in the SAT of lower extremities on 3-T non-tracer MR lymphangiography among individuals with lipedema, LWL, cancer treatment-related lymphedema, and female controls matched for age and BMI but without lipedema or lymphedema. SAT extravascular and vascular hyperintensities were less likely in controls than lipedema. Similar MR lymphangiography SAT features were observed in cases of lipedema with or without clinical symptoms of lymphedema. SAT hyperintensities were most prevalent in cases with advanced stages of lymphedema due to cancer therapies, as expected, and is consistent with MR lymphangiography contrast specificity for edema and lymphatic load.

Our findings corroborate other non-tracer MR lymphography and lymphoscintigraphy studies revealing imaging evidence of subcutaneous edema and lymphatic disruption in lipedema, and provide further evidence of unique lymphangiography profiles compared to obesity and lymphedema(21,22). Our study performed noninvasive 3-T MR lymphangiography and demonstrated that SAT diffuse hyperintensities were observed in participants with lipedema, LWL, or cancer-related lymphedema. In contrast, SAT hyperintensities were frequently not apparent in BMI-matched female controls without lymphedema or lipedema. Together, these observations may confirm specificity of MR lymphangiography to edema and increased lymphatic load in diseases of known etiologies (i.e., due to cancer therapies), and could provide evidence of a similar imaging profile in lipedema SAT. Despite modest sample sizes, these observations potentially underscore the feasibility for MR lymphangiography to provide further quantitative information and biomarkers of edema in adipose tissue of lower extremities in lipedema.

MR lymphangiography features revealed that SAT edema can be present in lipedema, despite the absence of clinical signs of overt lymphedema. A similar frequency of all SAT features, particularly diffuse hyperintensities and conspicuous linear vasculature, were observed in cases of lipedema and LWL. These MR lymphangiography patterns are consistent with tissue edema and excess lymph load in lipedema, a precursor to overt lymphedema development that could have implications for timely provision of clinical care. Persistent edema can disrupt lymphatic homeostasis when lymphatic load surpasses lymphatic transport capacity with either a dynamic or mechanical dysfunction(23). When left unmanaged, persistent edema will eventually result in lymphatic failure leading to lymphedema(23). Early detection of tissue edema in patients with lipedema is clinically relevant to potentially offer therapies such as compression and manual lymphatic drainage earlier in the natural history of the disease(8,9). More broadly, the quantification of lymphatic impairment in the setting of chronic edema is of growing clinical interest for differentiating between edema etiologies, assessing disease risk, and targeting treatments to mitigate associated morbidities(24).

Distinct lymphangiography patterns in lipedema SAT are also consistent with the growing body of evidence supporting the profound impact of lipedema on the SAT(6). Elevated tissue sodium (23Na) by multi-nuclear MRI, enlarged SAT area by conventional MRI, and SAT thickness by ultrasonography reveal tissue profiles in lipedema distinct from obesity(2,3,7). MR lymphangiography could provide additional imaging evidence, as suggested by blinded radiology review, that SAT abnormalities include edema and lymphatic involvement in lipedema.

This imaging strategy may also be useful as part of a noninvasive lymphedema surveillance exam for lipedema, similar to the lymphedema surveillance model used in the cancer population(25). Further development of imaging methods sensitive to lymphatic physiology could have clinical relevance for overcoming gaps in the clinical management of lipedema highlighted by the United States committee on Standard of Care for Lipedema and the Advanced Training Statement on Vascular Medicine(6,26). For instance, noninvasive 3-T MR lymphangiography uses commercially available hardware and radiofrequency pulse sequences, and can be accomplished in a clinically feasible scan time of approximately 11 minutes. MR lymphangiography can feasibly be implemented at most imaging centers, along with soft-tissue imaging of SAT expansion demonstrated previously, as part of a screening protocol for lipedema(2). Additional surveillance for persistent edema could be implemented for triaging patients to conservative physical therapies. For instance, lymphatic stimulation by standard complete decongestive therapy including manual lymphatic drainage is typically prescribed for patients with lipedema with lymphedema(6). However recent evidence demonstrates a benefit for manual therapy and early intervention in patients with early stage 1-2 lipedema(8). MR lymphangiography is a feasible modality that could possibly help detect early subcutaneous edema in patients with lipedema, although further study is needed to better understand the onset of edema in lipedema and whether manual therapy is beneficial for these patients prior to lymphedema onset.

Lymphatic involvement in lipedema has been speculated to occur in association with obesity but not lipedema(27). However, secondary lymphedema is associated with morbid obesity (generally defined as BMI>40 kg/m2), which was not a comorbidity of participants in this study who were limited to BMI<40 kg/m2 for MRI compatibility(28). Rather, compared to women matched for BMI, distinct lymphangiography hyperintensities persisted in the SAT of cases with lipedema. These findings could provide an additional layer of support for lipedema as a distinct entity from obesity. Future studies could incorporate MR lymphangiography with molecular MRI metrics of adipose tissue composition including sodium, which has previously demonstrated sensitivity for lipedema(2,3). Developing a comprehensive and objective diagnostic radiology test for lipedema should enhance our understanding of various stages of lipedema while controlling for obesity. The continued investigation of lipedema as a distinct clinical entity from obesity is critical given that many patients have concomitant lipedema and obesity(6).

The presence of SAT edema observed on MR lymphangiography in lipedema aids our understanding of the distinct nature of SAT in lipedema. Histopathology of SAT in patients with lipedema revealed that adipocytes are larger and hypertrophic, even in the SAT of non-obese persons with lipedema(29,30). These observations suggest alternative mechanisms of SAT expansion in lipedema, resulting in an abnormal accumulation of fluid. Possible mechanisms may involve microangiopathies, or altered integrity of the extracellular matrix implicating lipedema as a loose connective tissue disease(6,13). Lymphatic capillaries are sparse in human adipose tissue and do not exhibit morphological anomalies in lipedema biopsies other than infrequent dilation(30,31). Lymphatic homeostasis in lipedema could be impacted by circulating exosomes with increased platelet-factor 4 in lipedema(32). Evidence of fluid retention in the perivascular spaces in non-obese lipedema SAT, increased interstitial fluid area, intercellular fibrosis, and macrophages among adipocytes each contribute to increased lymph load in lipedema SAT(5,30,31).

Much work is remaining to understand the complex interplay between lymphatics and adipose tissue physiology(33,34). Lymphatic imaging methodologies are advancing, and will likely play a role in discoveries of elusive mechanisms that could be central to diseases such as cancer, hypertension, and heart failure (35,36). Lipedema may be an ideal condition in which to study how extreme adipose deposition exists in a milieu of lymph fluid stasis. Using in vivo imaging modalities to identify whether fat or fluid occurs earlier in disease, and how these components respond to non-metabolic interventions, should help further identify the drivers and mitigators of disease.

Limitations

A moderate sample of 48 participants were investigated including 4 subgroups with lipedema (n=14), LWL (n=12), lymphedema (n=8) or control (n=14) participants without these conditions. Despite the limited sample size, study participants were well-characterized by 3-T MRI, MR lymphangiography, and clinical examination and matched for multiple potentially confounding variables such as sex, age, and BMI. Independent raters provided fair agreement, which is not unreasonable considering this is a new contrast mechanism and scoring system with three categories and three reviewers, which together reduces the Kappa magnitude. Additionally, MR lymphangiography rating was applied in the less-frequently imaged cohort of lipedema for which reference images and interpretations provided herein could help improve the clinical utility of this modality. Further methodological developments are needed to quantify the spatial extent and range of signal intensities on MR lymphangiography, as well as to improve MR lymphangiography familiarity for diagnostic radiologists and imaging scientists.

It has been suggested that MR lymphangiography lacks specificity for lymphatics and appears similar to venography(18,37). Recent methodological reviews and practical considerations highlight this important discussion as non-tracer MR lymphangiography enters the clinical arena(35,38,39). To address this, our implementation of MR lymphangiography is designed to suppress fast flowing arterial and venous blood-water spins flowing into the FOV by applying regional saturations followed by dephasing gradients. Previous simulations of the long-TSE refocusing pulse train demonstrated that TSE factors >40 (shot duration ~528 ms) were sufficient to maintain signal from lymphatic fluid compared to residual blood-water signal(10). We acknowledge that while the contrast mechanism of MR lymphangiography has been sensitized to the kinetics (low flow velocity) and chemistry (long T2-relaxation times) of lymphatic fluid compared to blood and other tissues, in vivo lymphatic biology in humans is complex. It should be noted that lymphatics differentiate from the venous system in development and are often observed adjacent to venules in human skeletal muscle(40). It is therefore not surprising that lymphangiography appears similar to expected vascular features on venography. Prior work has shown clear visualization of conspicuous lymphatic vessels using MR lymphangiography (e.g., lymphatic duct) and sensitivity to lateralizing disease in individuals with unilateral secondary lymphedema, pointing to a primary contrast mechanism derived from lymphatic fluid(10,11). Future studies could incorporate MR venography or complementary near-infrared fluorescence lymphatic imaging to better define the specificity of MR lymphangiography to interstitial fluid clearance and the lymphatic network(15).

Conclusion

Imaging review of noninvasive 3-T MR lymphangiography identifies hyperintense signal patterns consistent with lower-extremity edema and increased lymphatic load in the SAT of participants with lipedema, including those with or without clinical symptoms of lymphedema. Observed lymphangiography profiles were distinct among participants who met clinical criteria for lipedema, compared to those with obesity or cancer treatment-related leg lymphedema.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Steven Dean, DO, FACP, RPVI for providing clinical photos to demonstrate lipedema and lymphedema symptomatology. Imaging experiments were performed in the Vanderbilt Human Imaging Core, using research resources supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1S10OD021771-01. We are grateful for Philips support from Charles Nockowski and Ryan Robinson, and to core MRI technologists Christopher Thompson, Clair Jones, Marisa Bush, Josh Hageman, and Cori Welliever. Recruitment through www.ResearchMatch.org and services at the Clinical Research Center are supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) Program, award number 5UL1TR002243-03.

Grant funding:

NIH/NINR R01NR015079, NIH/NHLBI 1R01HL155523, NIH/NHLBI 1R01HL157378, NIH 1S10OD021771-01, NIH/NHLBI K23 HL151871, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) Program award number 5UL1TR002243-03, Institutional National Research Service Award (NRSA) T32 EB001628, Lipedema Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship, Lipedema Foundation Collaborative Grant #12, American Heart Association 18CDA34110297, American Heart Association 19IPLOI34760518, American Heart Association 18SFRN33960373.

Footnotes

Disclosures: M.J.D. receives research related support from Philips North America; is a paid consultant for Pfizer Inc, Global Blood Therapeutics, and LymphaTouch; is a paid advisory board member for Novartis and bluebird bio; receives research funding from Pfizer Inc; and is the CEO of biosight, LLC which provides healthcare technology consulting services. A.W.A reports receiving personal fees from OptumCare outside of the current work. J.A.B. reports consulting honoraria for JanOne, Janssen, and Novartis.

References

- 1.Herbst KL. Rare adipose disorders (RADs) masquerading as obesity. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2012;33(2):155–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crescenzi R, Donahue PMC, Petersen KJ, et al. Upper and Lower Extremity Measurement of Tissue Sodium and Fat Content in Patients with Lipedema. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(5):907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crescenzi R, Marton A, Donahue PMC, et al. Tissue Sodium Content is Elevated in the Skin and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue in Women with Lipedema. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(2):310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pouwels S, Huisman S, Smelt HJM, Said M, Smulders JF. Lipoedema in patients after bariatric surgery: report of two cases and review of literature. Clin Obes 2018;8(2):147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen M, Schwartz M, Herbst KL. Interstitial Fluid in Lipedema and Control Skin. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) 2020;1(1):480–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst KL, Kahn LA, Iker E, et al. Standard of care for lipedema in the United States. Phlebology 2021:2683555211015887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iker E, Mayfield CK, Gould DJ, Patel KM. Characterizing Lower Extremity Lymphedema and Lipedema with Cutaneous Ultrasonography and an Objective Computer-Assisted Measurement of Dermal Echogenicity. Lymphat Res Biol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donahue PMC, Crescenzi R, Petersen KJ, et al. Physical Therapy in Women with Early Stage Lipedema: Potential Impact of Multimodal Manual Therapy, Compression, Exercise, and Education Interventions. Lymphat Res Biol 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst KL, Ussery C, Eekema A. Pilot study: whole body manual subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) therapy improved pain and SAT structure in women with lipedema. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2017;33(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crescenzi R, Donahue PMC, Hartley KG, et al. Lymphedema evaluation using noninvasive 3T MR lymphangiography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017;46(5):1349–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cellina M, Martinenghi C, Panzeri M, et al. Noncontrast MR Lymphography in Secondary Lower Limb Lymphedema. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rane S, Donahue PMC, Towse T, et al. Clinical feasibility of noninvasive visualization of lymphatic flow with principles of spin labeling MR imaging: implications for lymphedema assessment. Radiology 2013;269(3):893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amann-Vesti BR, Franzeck UK, Bollinger A. Microlymphatic aneurysms in patients with lipedema. Lymphology 2001;34(4):170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohrmann C, Foeldi E, Langer M. MR imaging of the lymphatic system in patients with lipedema and lipo-lymphedema. Microvasc Res 2009;77(3):335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen JC, Herbst KL, Aldrich MB, et al. An abnormal lymphatic phenotype is associated with subcutaneous adipose tissue deposits in Dercum's disease. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22(10):2186–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Executive Committee of the International Society of L. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2020 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2020;53(1):3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhry AA, Baker KS, Gould ES, Gupta R. Necrotizing fasciitis and its mimics: what radiologists need to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;204(1):128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu N, Wang C, Sun M. Noncontrast three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging vs lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lymph circulation disorders: A comparative study. J Vasc Surg 2005;41(1):69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosmidis I, Firth D. Jeffreys-prior penalty, finiteness and shrinkage in binomial-response generalized linear models. Biometirka URL: 10.1093/biomet/asaa052. 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 2005;85(3):257–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cellina M, Gibelli D, Soresina M, et al. Non-contrast MR Lymphography of lipedema of the lower extremities. Magn Reson Imaging 2020;71:115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gould DJ, El-Sabawi B, Goel P, Badash I, Colletti P, Patel KM. Uncovering Lymphatic Transport Abnormalities in Patients with Primary Lipedema. J Reconstr Microsurg 2020;36(2):136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin-Almedina S, Mortimer PS, Ostergaard P. Development and physiological functions of the lymphatic system: insights from human genetic studies of primary lymphedema. Physiol Rev 2021;101(4):1809–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moffatt C, Keeley V, Quere I. The Concept of Chronic Edema-A Neglected Public Health Issue and an International Response: The LIMPRINT Study. Lymphat Res Biol 2019;17(2):121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stout NL, Binkley JM, Schmitz KH, et al. A prospective surveillance model for rehabilitation for women with breast cancer. Cancer 2012;118(8 Suppl):2191–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creager MA, Hamburg NM, Calligaro KD, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SVM/ACP Advanced Training Statement on Vascular Medicine (Revision of the 2004 ACC/ACP/SCAI/SVMB/SVS Clinical Competence Statement on Vascular Medicine and Catheter-Based Peripheral Vascular Interventions). Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14(2):e000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertsch T, Erbacher G, Corda D, et al. Lipoedema - myths and facts, Part 5 European Best Practice of Lipoedema Summary of the European Lipoedema Forum consensus. PHLEBOLOGIE 2020;49(1). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fife CE, Carter MJ. Lymphedema in the morbidly obese patient: unique challenges in a unique population. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54(1):44–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felmerer G, Stylianaki A, Hagerling R, et al. Adipose Tissue Hypertrophy, An Aberrant Biochemical Profile and Distinct Gene Expression in Lipedema. J Surg Res 2020;253:294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Ghadban S, Cromer W, Allen M, et al. Dilated Blood and Lymphatic Microvessels, Angiogenesis, Increased Macrophages, and Adipocyte Hypertrophy in Lipedema Thigh Skin and Fat Tissue. J Obes 2019;2019:8747461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felmerer G, Stylianaki A, Hollmen M, et al. Increased levels of VEGF-C and macrophage infiltration in lipedema patients without changes in lymphatic vascular morphology. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma W, Gil HJ, Escobedo N, et al. Platelet factor 4 is a biomarker for lymphatic-promoted disorders. JCI Insight 2020;5(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kataru RP, Park HJ, Baik JE, Li C, Shin J, Mehrara BJ. Regulation of Lymphatic Function in Obesity. Front Physiol 2020;11:459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutkowski JM, Davis KE, Scherer PE. Mechanisms of obesity and related pathologies: the macro- and microcirculation of adipose tissue. FEBS J 2009;276(20):5738–5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mills M, van Zanten M, Borri M, et al. Systematic Review of Magnetic Resonance Lymphangiography From a Technical Perspective. J Magn Reson Imaging 2021;53(6):1766–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fudim M, Salah HM, Sathananthan J, et al. Lymphatic Dysregulation in Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78(1):66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee BB. Regarding "Noncontrast three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging vs lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lymph circulation disorders: a comparative study". J Vasc Surg 2005;42(4):821; author reply 821–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Misere RML, Wolfs J, Lobbes MBI, van der Hulst R, Qiu SS. A systematic review of magnetic resonance lymphography for the evaluation of peripheral lymphedema. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2020;8(5):882–892 e882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guerrini S, Gentili F, Mazzei FG, Gennaro P, Volterrani L, Mazzei MA. Magnetic resonance lymphangiography: with or without contrast? Diagn Interv Radiol 2020;26(6):587–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breslin JW, Yang Y, Scallan JP, Sweat RS, Adderley SP, Murfee WL. Lymphatic Vessel Network Structure and Physiology. Compr Physiol 2018;9(1):207–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]