Abstract

Background:

Upper esophageal sphincter opening (UESO), and laryngeal vestibule closure (LVC) are two essential kinematic events whose timings are crucial for adequate bolus clearance and airway protection during swallowing. Their temporal characteristics can be quantified through time-consuming analysis of videofluoroscopic swallow studies.

Objectives:

We sought to establish a model to predict the odds of penetration or aspiration during swallowing based on 15 temporal factors of UES and laryngeal vestibule kinematics.

Methods:

Manual temporal measurements and ratings of penetration and aspiration were conducted on a videofluoroscopic dataset of 408 swallows from 99 patients. A generalized estimating equation model was deployed to analyze association between individual factors and the risk of penetration or aspiration.

Results:

The results indicated that the latencies of laryngeal vestibular events and the time lapse between UESO onset and LVC were highly related to penetration or aspiration. The predictive model incorporating patient demographics and bolus presentation showed that delayed LVC by 0.1s or delayed LVO by 1% of the swallow duration (average 0.018s) was associated with a 17.19% and 2.68% increase in odds of airway invasion, respectively.

Conclusion:

This predictive model provides insight into kinematic factors that underscore the interaction between the intricate timing of laryngeal kinematics and airway protection. Recent investigation in automatic non-invasive or videofluoroscopic detection of laryngeal kinematics would provide clinicians access to objective measurements not commonly quantified in VFSS. Consequently, the temporal and sequential understanding of these kinematics may interpret such measurements to an estimation of the risk of aspiration or penetration which would give rise to rapid computer-assisted dysphagia diagnosis.

Keywords: Aspiration, Dysphagia, Videofluoroscopic swallow studies, Upper esophageal sphincter, Laryngeal vestibule closure

Introduction

Dysphagia is a swallowing disorder that affects up to 30–40% of older individuals and is highly prevalent among populations with head/neck cancer, neurological diseases, and iatrogenic conditions.1–3 Patients with dysphagia are at risk of aspirating material into the lungs, which may result in aspiration pneumonia and other complications such as malnutrition and dehydration1; therefore, comprehensive evaluation of aspiration risk is critical in initiating and managing dysphagia treatment.

Videofluoroscopic swallow studies (VFSS) allow real-time observation of swallowing physiology and kinematics.4 From VFSS images, clinicians can use the 8-point penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) to evaluate the presence and depth of swallowed material in the airway.5 Additionally, they can perform temporal and spatial kinematics analyses to determine significant deviations from the norms of swallowing.6,7,8 Unfortunately, only 16% of speech-language pathologists responding to a research survey always performed frame-by-frame measurements, while 32% of them never perform such measurements.9

During swallowing, a variety of biomechanical events occur in about 1 second, including upper esophageal sphincter opening (UESO) and laryngeal vestibule closure (LVC). Both events are directly related to other kinematics: hyolaryngeal excursion contributes to the sealing of the larynx and pulls open the UES10; intrabolus pressure is generated in balance with reduced UES muscle tension and anterior traction of cricoid cartilage11. The pattern of swallowing momentarily shifts the pharynx from the respiratory mode to the deglutitive mode, closing the larynx and opening the UES, in a sequential manner that enables bolus transport while breathing is interrupted. Therefore, the fine temporal coordination and sufficient duration of UESO and LVC are crucial for effective and safe swallowing.12

The normal sequential relation between LVC and UESO have been studied. Kendall et al13 observed that the onset of aryepiglottic fold elevation always occurs before UESO and complete supraglottic closure occurs almost always prior to UESO among healthy volunteers for liquid swallows regardless of volume. While Molfenter et al14 confirmed that the onset of airway closure commonly occurs before UESO, they disagreed with certain obligatory ordering proposed by Kendall et al. and concluded that the overall swallowing sequence is highly variable across young healthy adults through repeated trials. Herzberg et al15 observed UESO happening before laryngeal closure predominantly among older participants but less frequently among younger ones. All three above-mentioned studies reported no clear influence of bolus viscosity but suggested that smaller bolus volume might cause greater sequence variations. To summarize, current investigations fail to establish a universal obligatory sequence between LVC and UESO for healthy swallows; variable sequencing between these events have been noticed across different bolus volumes, participants’ ages, and repeated trials.

Other studies considered UESO and LVC latencies (referenced to the beginning of the swallow or other events), durations, and the time intervals between these events as swallowing characteristics.14 Steele et al16 found that the average time lapse between UESO and LVC is 0.046 s and UES closure occurred about 0.03 s before the laryngeal reopening among healthy young adults. Park et al17 observed significantly delayed initiation and reduced duration of LVC among patients with stroke who aspirated versus who did not aspirate. Nativ-Zeltzer et al.18 found significantly longer LVC latencies until glossopalatal junction opening for the patients who aspirated and penetrated compared to the healthy subjects but longer UESO latencies only for penetration group. Kiyohara et al19 identified the prolonged time interval between the start of laryngeal elevation and LVC favoring penetration or aspiration during hyolaryngeal displacement, as well as the premature laryngeal reopening during its descent. Both videofluoroscopic and manometric studies revealed the association of post-stroke aspiration with shorter UESO duration.20,21 In addition, Saconato et al22 reported longer duration of supraglottic closure for post-stroke patients who aspirated than patients who did not; however, the duration of UESO was not found significant regardless of volume and consistency. Besides variables measuring individual events, Choi et al23 and Curtis et al24 considered temporal relations between laryngeal events and UESO among patients with dysphagia and Parkinson’s diseases but neither discovered their association to aspiration. Although various temporal measures of UESO and LVC have been examined in the literature, there is no consistent conclusion on which latencies or temporal relations are the most influential and to what extent they influence swallowing safety.

Consequently, the present study sought to estimate the risk of penetration or aspiration in patients suspected of having dysphagia based on the temporal variables (i.e., initiation, termination, duration, and relative time lapse of UESO and LVC) extracted from videofluoroscopic image sequence analyses. This is the first research we are aware of that used duration of pharyngeal swallow segments as a temporal factor to normalize the variables across different swallows. Our hypothesis is that these raw and/or normalized temporal variables of UESO and LVC are associated with aspiration or penetration. We aimed to determine the most significant correlates of airway invasion and quantify how the risk changes as a function of these attributes via a novel repeated-measure multivariable model.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh. All participants provided written informed consent. Patients referred for a VFSS at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian University Hospital (Pittsburgh, PA) were recruited. Each patient underwent VFSS conducted by a speech-language pathologist who determined the bolus size, bolus consistency, and swallowing maneuver according to patients’ conditions under standard clinical protocol. Only swallows with thin liquid boluses (Varibar thin, Bracco Diagnostics, Inc., < 5 cPs viscosity) were considered in the present analysis. Boluses were either self-administered by patients via a cup or a straw for uncued swallows or administered by a clinician using a spoon for cued swallows.

During the VFSS examination, patients were positioned laterally to a standard x-ray machine (Ultimax system, Toshiba, Tustin, CA) at 30 pulses per second with their head in a neutral position. The video stream was captured by AccuStream Express HD (Foresight Imaging, Chelmsford, MA) at a sampling frequency of 30 frames per second.

VFSS Image Analysis

The dataset of this study was accrued during an ongoing larger investigation of surface pharyngeal sensors in characterizing swallow physiology.25 All video clips were preliminarily segmented from the swallow onset (or initiation of the pharyngeal phase) when the head of bolus reached the posterior ramus of the mandible, until the swallow offset when the hyoid bone returned to the lowest position and the bolus has cleared from pharynx. This duration has been defined as pharyngeal transit duration.26 The UES region is considered approximately the height of the third cervical vertebral body (C3) inferiorly from the top edge of tracheal column.27 The timing measurements of UESO and LVC were marked for each swallow according to the following criteria:

UESO onset: The time of the first frame in which air or barium contrast is observed in the UES region.28

UESO offset: The time of the first frame in which air or barium contrast is completely cleared from the UES region.27

LVC: The time of the first frame in which air space is no longer visible in the laryngeal vestibule (between the arytenoids and epiglottic base).29

Laryngeal vestibule reopening (LVO): The time of the first frame of obvious air space reappearance within the laryngeal vestibule.29

All temporal and clinical measurements were performed by trained judges who were blinded to patients’ demographics and diagnoses. Reliability of judges was established and maintained with excellent intra- and inter-rater reliability (> 0.99 intraclass correlation coefficients) on a randomly selected 10% of the swallows.

A set of temporal variables were calculated using the above-mentioned measurements to explore the UESO and LVC timings. Previous studies employed the onset of the swallow as an anchor to calculate the onset of UESO30 and the initiation of LVC17,23,24 (or bolus dwell time31). Similarly, we computed the time between the swallow onset and each UESO and LVC latency component. Additional variables were calculated to describe their durations and temporal relations. These variables were either represented in seconds, or by their ratio to the swallow duration:

Swallow duration (s): The time difference between swallow onset and swallow offset.

UESO-latency (s): The time difference between swallow onset and UESO onset.

UESC-latency (s): The time difference between swallow onset and UESO offset.

LVC-latency (s): The time difference between swallow onset and LVC.

LVO-latency (s): The time difference between swallow onset and LVO.

UESO-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The ratio between UESO-latency and swallow duration.

UESC-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The ratio between UESC-latency and swallow duration.

LVC-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The ratio between LVC-latency and swallow duration.

LVO-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The ratio between LVO-latency and swallow duration.

UESO-duration (s): The time difference between UESO-latency and UESC-latency.

LVC-duration (s): The time difference between LVC-latency and LVO-latency.

UESO-duration-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The ratio between UESO-duration and swallow duration.

LVC-duration-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The ratio between LVC-duration and swallow duration.

UESO-LVC-duration-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The time difference between UESO-latency and LVC-latency divided by swallow duration.

LVO-UESC-duration-normalized-ratio (% swallow duration): The time difference between LVO-latency and UESC-latency divided by swallow duration.

Statistical Analysis

The presence of penetration or aspiration was a dichotomous variable based on PAS ratings. PAS scores of 1–2 represented safe swallows, while PAS ≥ 3 corresponded to penetration or aspiration (unsafe swallows).7 We collected more than one swallow for each participant so correlations may exist among repeated swallow measurements from the same patients32; consequently, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model with a binomial distribution, logit link function, and exchangeable working correlation matrix was used to associate each of the 15 temporal variables with penetration or aspiration. To obtain a parsimonious multivariable model, we used a forward selection strategy on the 15 variables with and without forcing in the demographics and bolus characteristics variables. Previous literature has reported an age effect on swallow events, citing significant differences between healthy younger (<45 years) and older (>65 years) subjects.15,33 However, most of our patients were older than 60 years and thus the correlation between temporal variables and age was neglected. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

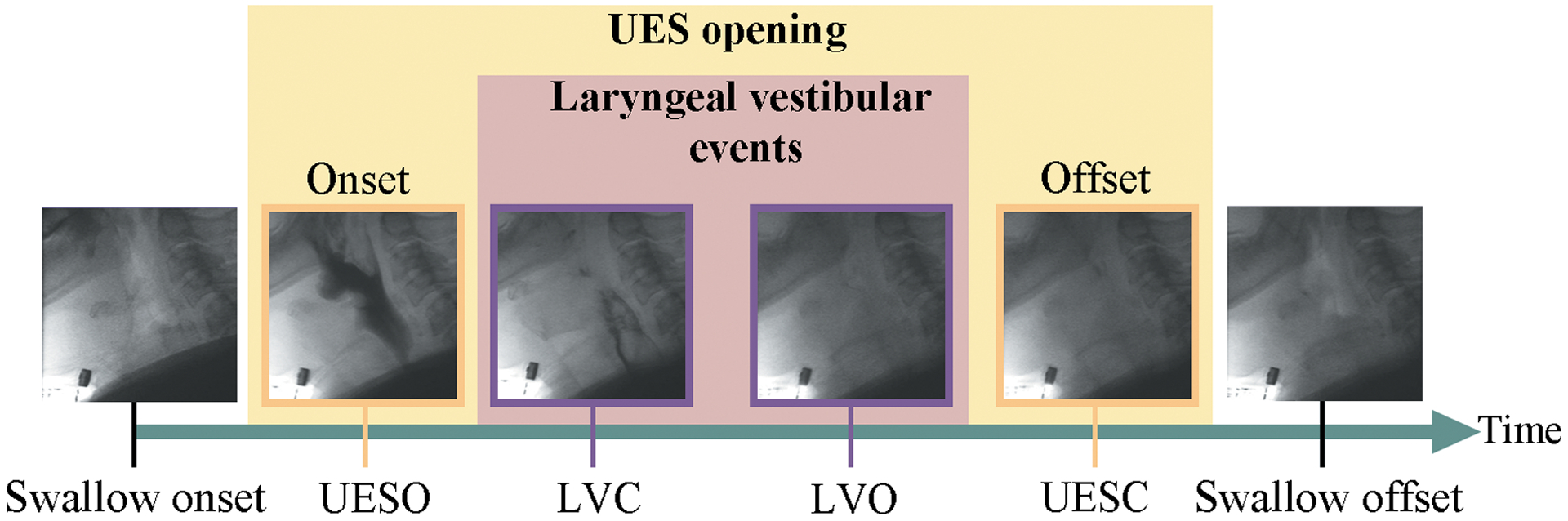

We analyzed 408 swallows from 99 patients of which the characteristics are presented in Table 1. Swallows grouped by PAS scores are shown in Table 2. The most common sequential pattern of UESO and LVC represented 76% of our dataset is shown in Figure 1 (it should be noted that UESO onset can occur before or after LVC, and UES closure can happen before or after laryngeal reopening29).

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics and bolus consistencies.

| Characteristics | Number of Participants (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 99 |

| Female participants | 38 (38.4%) |

| Male participants | 61 (61.6%) |

| Stroke participants | 14 (14.1%) |

| Non-stroke participants | 85 (85.9%) |

| Age (year) | 63.14 ± 15.223 |

| Utensil | Number of Swallows (percentage) |

| Total swallows | 408 |

| Spoon | 140 (34.3%) |

| Cup | 203 (49.8%) |

| Cup with straw | 65 (15.9%) |

TABLE 2.

Number of swallow samples in each penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) value

| Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Swallows | 154 | 175 | 35 | 21 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

FIGURE 1.

Upper esophageal sphincter opening (UESO), and laryngeal vestibule closure (LVC) events occur in sequential manner based on videofluoroscopic analysis.

The averaged values of temporal variables and the results of one-at-a-time statistical analysis with and without demographics and bolus conditions adjustment are shown in Table 3. In both models, swallows with unsafe airway protection (i.e., PAS ≧ 3) had significantly later occurrences of LVC, LVO, LVC-normalized-ratio, LVO-normalized-ratio, and larger UESO-LVC-duration-normalized-ratio as compared to safe swallows (i.e., PAS 1–2).

TABLE 3.

Mean ± standard deviation (SD), and results from the unadjusted univariate and adjusted multivariate generalized estimating equation (GEE) models for one-at-a-time temporal variables, that averaged across multiple swallows from each participant, associated with the risk of penetration or aspiration (PAS≥3).

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (Units for Odds Ratio) | Mean ± SD | Odds Ratio Estimate |

p value | Odds Ratio Estimate |

p values |

| Swallow duration (0.1 s) | 17.939 ± 3.678 | 1.11 | 0.7468 | 1.17 | 0.6439 |

| UESO events | |||||

| UESO-latency (0.1 s) | 3.158 ± 1.325 | 1.08 | 0.4142 | 1.08 | 0.4309 |

| UESC-latency (0.1 s) | 15.462 ± 2.430 | 1.09 | 0.0502 | 1.13 | 0.0114 * |

| UESO-duration (0.1 s) | 12.304 ± 2.165 | 1.08 | 0.1151 | 1.12 | 0.0294 * |

| UESO-normalized-ratio (1%) | 18.046 ± 6.883 | 1.01 | 0.5775 | 1.01 | 0.6274 |

| UESC-normalized -ratio (1%) | 89.561 ± 16.546 | 1.01 | 0.1937 | 1.01 | 0.1116 |

| UESO-duration-normalized-ratio (1%) | 71.515 ± 15.777 | 1.01 | 0.3555 | 1.01 | 0.2136 |

| Laryngeal vestibule events | |||||

| LVC-latency (0.1 s) | 7.549 ± 2.296 | 1.16 | 0.0012 * | 1.20 | 0.0001 * |

| LVO-latency (0.1 s) | 13.863± 3.133 | 1.11 | 0.0015 * | 1.11 | 0.0007 * |

| LVC-duration (0.1 s) | 6.314 ± 2.350 | 1.04 | 0.2999 | 1.04 | 0.3251 |

| LVC-normalized-ratio (1%) | 42.395 ± 10.565 | 1.04 | 0.0005 * | 1.04 | 0.0002 * |

| LVO-normalized-ratio (1%) | 78.590 ± 12.669 | 1.03 | 0.0002 * | 1.03 | <0.0001 * |

| LVC- duration-normalized-ratio (1%) | 36.194 ± 12.330 | 1.00 | 0.6358 | 1.00 | 0.6912 |

| UESO-LVC-duration-normalized-ratio (1%) | 24.349 ± 9.206 | 1.03 | 0.0010 * | 1.03 | 0.0003 * |

| LVO-UESC-duration-normalized-ratio (1%) | 10.971 ± 15.612 | 0.99 | 0.1162 | 0.99 | 0.1888 |

Statistically significant variables

The parsimonious multivariable model only identified the association between airway invasion and laryngeal kinematics: delayed LVO in proportion to the swallow duration (LVO-normalized-ratio) and delayed LVC latency, as shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Swallowing temporal determinants of the risk of penetration or aspiration (PAS≥3) with unadjusted model by forward selection.

| Variable (Units for Odds Ratio) | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVO-normalized-ratio (1%) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.04 | 0.0009 |

| LVC-latency (0.1 s) | 1.14 | 1.04–1.25 | 0.0058 |

Table 5 presents the results combining temporal variables with patients’ ages, sex, and mode of bolus. The forward selection on the adjusted set of variables resulted in the same kinematic variables (i.e., LVO-normalized-ratio and LVC-latency) as the unadjusted model with consistent estimates of coefficients. According to the adjusted model, delayed LVC by 0.1s results in a 17.19% increase in the odds of airway invasion. Delayed LVO by 1% of the swallow duration (average 0.018s) indicated 2.68% more odds to penetrate or aspirate. In consequence, 1s delay in LVC or LVO latencies would magnify these odds by 4.9 (odds ratio [OR] 4.89; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.94–12.29) or 4.4 (OR 4.37; 95% CI 1.96–9.71) times respectively. Additionally, each 10 years of age will increase patients’ odds of penetration or aspiration by 16.07% and females are 12.21% less likely to experience unsafe swallows, but these effects are not statistically significant. However, self-feeding by cup is significantly associated with 68.98% lower risk of airway invasion than feeding by spoon.

TABLE 5.

Patient demographics and utensil type as additional independent variables of the risk of penetration or aspiration (PAS≥3) with adjusted model.

| Variable (Units/Comparisons for Odds Ratio) | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVO-normalized-ratio (1%) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.04 | 0.0003 |

| LVC-latency (0.1 s) | 1.17 | 1.07–1.29 | 0.0007 |

| Age (10 years) | 1.16 | 0.93–1.45 | 0.1952 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.88 | 0.43–1.81 | 0.7249 |

| Administration mode (cup with straw vs. spoon) | 0.74 | 0.39–1.39 | 0.3414 |

| Administration mode (cup vs. spoon) | 0.31 | 0.17–0.56 | <0.0001 |

Discussion

In this study, we sought to determine whether the kinematic timings are predictive of penetration or aspiration among patients with suspected dysphagia. We specifically examined the singular, coordinated, and normalized temporal variables of UESO and LVC, for which the sequential characteristics have not been fully established.

The LVC latency was found to be different between safe and unsafe swallows, which is consistent with previous work on stroke patients34; however, the delayed latency of LVO was also found significant, which has rarely been considered as a predictor. This finding may suggest that the temporal pattern of laryngeal reopening, but not necessarily the duration of LVC, is critical for airway protection. Counterintuitively, delayed laryngeal reopening did not improve airway protection in our cohort; this may be due changes in the duration and timing of swallow apnea among patients with respiratory illnesses and a subsequently higher risk of aspiration or penetration.35,36

According to our analyses, UESC latency and durations were only found associated with penetration or aspiration in adjusted analyses and were not selected in our final prediction models; however, reduced UESO duration and delayed initiation of UESO have shown to be determinative.23,31 This discrepancy may be the result of variations in defining disordered groups. Previous studies placed patients with at least one abnormal swallow (i.e., PAS ≥ 331 or PAS ≥ 623) into disordered/aspirated swallow groups. Conversely, we analyzed single swallow events and considered a PAS ≥ 3 an unsafe swallow sample, rather than placing patients into categories, because a) healthy individuals may have more than one abnormal swallow according to PAS on a VFSS,37 but we would not place them in a disordered swallow group and b) patients who typically aspirate may not during the short window of time of the VFSS, so it would not be accurate to place them in a “normal swallow” group.7,33

We also found that the shorter time lapse between LVC and UESO onset (i.e., UESO-LVC-duration-normalized-ratio) was significantly associated with penetration or aspiration, suggesting that late laryngeal closure prior to UESO and even after UESO may lead to swallowed material entering the airway and incomplete bolus clearance. This finding was not observed previously, because Choi et al23 defined the region of UES by the narrowest part of the upper esophagus between C4 and C6 which is different from our study and analyzed UESO to laryngeal elevation instead of laryngeal closure. Furthermore, Curtis et al24 specifically analyzed patients with Parkinson’s disease and dysphagia while our participants had varied medical conditions. This variable was eventually excluded from our multivariate models which may be due to its collinearity with LVC.

Although the duration of a swallow segment was not correlated with airway invasion, the smaller ratio of the LVC and LVO latencies to swallow duration were associated with increased risk. In addition, the final models suggested that the LVO normalized latency was a better than the raw measurement, indicating that with same laryngeal latencies, swallows with shorter duration are more likely to be unsafe.

Despite of the fact that age was not significantly associated to penetration or aspiration, our final model coefficients were suggestive that older people may be at a greater risk as demonstrated in previous studies.38,39 The magnitude of the model coefficients also indicated that, although the difference between men and women was not significant, females may be less likely to aspirate or penetrate; this finding may be due to the imbalance of gender distribution in our study. Boluses administrated by clinicians using spoons were more likely to cause airway invasion than self-administrated boluses by cup, possibly because aspiration is more affected by cueing and administering conditions than bolus volume.24,40

We believe our findings are essential to add objectivity and accuracy to swallowing assessment. Serial quantification of laryngeal-pharyngeal kinematics importantly reveals the structural and functional integrity for airway protection during VFSS. However, the objective measurements are often time-consuming leading clinicians to form subjective inferences about aspiration risk and outcomes when they do not overtly occur during examination. Recent technological advancements enable non-invasive detection of swallowing kinematics solely based on swallowing sounds and vibrations.41–46 Other computer vision and artificial intelligence techniques were applied for automated frame-by-frame hyoid47 and laryngeal48 analyses on VFSS. These extracted measurements can be incorporated to our temporal understanding of laryngeal kinematics to estimate the risk of penetration or aspiration. Such automated analysis followed by clinician confirmation and interpretation would provide baseline to evaluate the progression of dysphagia and efficacy of treatment.

There are several limitations of current study. The model was established only on thin liquid boluses, thus, does not explain how patients’ risk of aspiration would be affected by boluses consistencies. Other physiological factors that contribute to airway protection were missing to provide a full swallowing analysis. For example, reduced UESO, which may cause post-swallow residue and consequently post-swallow penetration or aspiration, should be associated to residual ratings such as the Modified Barium Study Impairment Profile.31,49,50 Furthermore, the distribution of PAS scores is naturally skewed, and higher scores are in minority. This imbalance distribution might affect the classification performance. Data oversampling and augmentation techniques may be used for future studies to ensure a greater proportion of unsafe swallows.

In this study, we normalized kinematic timings using swallow duration. This conversion allowed us to align swallowing motor pattern among various patients and bolus conditions. The validity of such a normalization is an avenue for further investigation.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the delayed latency of LVC and delayed LVO proportional to swallow duration is associated with the risk of penetration or aspiration of thin liquid swallows. This finding would provide justification to perform objective frame-by-frame temporal VFSS analyses when a) the delay of kinematics is too subtle to be perceived by human, b) no apparent sign of swallowing impairment can be observed during short-time VFSS examination. With recent advancement in non-invasive kinematic detection and computer-assisted VFSS analyses, the delay of laryngeal kinematics can be captured automatically, and our findings would add more objectivity and accuracy to swallowing assessment.

Acknowledgements:

The research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD092239, and the data was collected under Award Number R01HD074819. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Level of Evidence: 2

References

- 1.Clavé P, Shaker R. Dysphagia: current reality and scope of the problem. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. May;12(5):259–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takizawa C, Gemmell E, Kenworthy J, Speyer R. A systematic review of the prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, head Injury, and pneumonia. Dysphagia. 2016. Jun;31(3):434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoyagi Y, Ohashi M, Funahashi R, Otaka Y, Saitoh E. Oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia following coronavirus disease 2019: a case report. Dysphagia. 2020. Jun;35(4):545–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rugiu MG. Role of videofluoroscopy in evaluation of neurologic dysphagia. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2007. Dec;27(6):306–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenbek J, Robbins J, Roecker E, Coyle J, Wood J. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingjie L, Tong Z, Xinting S, Jianmin X, Guijun J. Quantitative videofluoroscopic analysis of penetration-aspiration in post-stroke patients. Neurol India. 2010. Jan;58(1):42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Perera S, Donohue C, et al. The prediction of risk of penetration-aspiration via hyoid bone displacement features. Dysphagia. 2020. Feb;35(1):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y, McCullough GH, Asp CW. Temporal measurements of pharyngeal swallowing in normal populations. Dysphagia. 2005. Fall;20(4):290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vose AK, Kesneck S, Sunday K, Plowman E, Humbert I. A Survey of Clinician Decision Making When Identifying Swallowing Impairments and Determining Treatment. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2018;61(11):2735–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuo K, Palmer JB. Anatomy and physiology of feeding and swallowing: normal and abnormal. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008;19(4):691–vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook IJ. Clinical disorders of the upper esophageal sphincter. GI Motility online. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuo K, Palmer JB. Coordination of mastication, swallowing and breathing. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2009. May;45(1):31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendall KA, Leonard RJ, McKenzie SW. Sequence variability during hypopharyngeal bolus transit. Dysphagia. 2003. Spring;18(2):85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molfenter SM, Leigh C, Steele CM. Event sequence variability in healthy swallowing: building on previous findings. Dysphagia. 2014;29(2):234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzberg EG, Lazarus CL, Steele CM, Molfenter SM. Swallow event sequencing: comparing healthy older and younger adults. Dysphagia. 2018. Dec;33(6):759–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele CM, Peladeau-Pigeon M, Barbon CAE, et al. Reference values for healthy swallowing across the range from thin to extremely thick liquids. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019;62(5):1338–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park T, Kim Y, Ko DH, McCullough G. Initiation and duration of laryngeal closure during the pharyngeal swallow in post-stroke patients. Dysphagia. 2010. Sep;25(3):177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nativ-Zeltzer N, Logemann JA, Kahrilas PJ. Comparison of timing abnormalities leading to penetration versus aspiration during the oropharyngeal swallow. The Laryngoscope. 2014;124:935–941. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiyohara H, Adachi K, Kikuchi Y, Uchi R, Sawatsubashi M, Nakagawa T. Kinematic evaluation of penetration and aspiration in laryngeal elevating and descending periods. The Laryngoscope. 2018;128:806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee T, Park JH, Sohn C, et al. Failed deglutitive upper esophageal sphincter relaxation is a risk factor for aspiration in stroke patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017. Jan;23(1):34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y, Park T, Oommen E, McCullough G. Upper esophageal sphincter opening during swallow in stroke survivors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015. Sep;94(9):734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saconato M, Leite FC, Lederman HM, Chiari BM, Gonçalves MIR. Temporal and sequential analysis of the pharyngeal phase of swallowing in poststroke patients. Dysphagia. 2020. Aug;35(4):598–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KH, Ryu JS, Kim MY, Kang JY, Yoo SD. Kinematic analysis of dysphagia: significant parameters of aspiration related to bolus viscosity. Dysphagia. 2011. Dec;26(4):392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JA, Molfenter S, Troche MS. Predictors of residue and airway invasion in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia. 2020;35:220–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyle JL, Sejdić E. High-resolution cervical auscultation and data science: new tools to address an old problem. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020. Jul;29(2S):992–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lof GL, Robbins J. Test-retest variability in normal swallowing. Dysphagia. 1990;4(4):236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shu K, Coyle JL, Perera S, Khalifa Y, Sabry A, Sejdić E. Anterior-posterior distension of maximal upper esophageal sphincter opening is correlated with high-resolution cervical auscultation signal features. Physiol Meas. 2021. Apr;42(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendell DA, Logemann JA. Temporal sequence of swallow events during the oropharyngeal swallow. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007. Oct;50(5):1256–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logemann JA, Kahrilas PJ, Cheng J, et al. Closure mechanisms of laryngeal vestibule during swallow. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1992. Feb;262(2 Pt 1):G338–G344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Power ML, Hamdy S, Singh S, Tyrrell PJ, Turnbull I, Thompson DG. Deglutitive laryngeal closure in stroke patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007. Feb;78(2):141–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molfenter SM, Steele CM. Kinematic and temporal factors associated with penetration-aspiration in swallowing liquids. Dysphagia. 2014. Apr;29(2):269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballinger GA. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2004. Apr;7(2):127–50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Namasivayam-MacDonald AM, Barbon CEA, Steele CM. A review of swallow timing in the elderly. Physiol Behav. 2018. Feb 1;184:12–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park T, Kim Y, Oh BM. Laryngeal closure during swallowing in stroke survivors with cortical or subcortical lesion. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017. Aug;26(8):1766–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brodsky MB, De I, Chilukuri K, Huang M, Palmer JB, Needham DM. Coordination of pharyngeal and laryngeal swallowing events during single liquid swallows after oral endotracheal intubation for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Dysphagia. 2018; 33(6): 768–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JL. Pulmonary complications of oral-pharyngeal motility disorders. GI Motility online. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robbins J, Coyle JL, Rosenbek JC, Roecker EB, Wood JL. Differentiation of normal and abnormal airway protection during swallowing using the penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1999; 14(4): 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feinberg MJ, Ekberg O. Videofluoroscopy in elderly patients with aspiration: importance of evaluating both oral and pharyngeal stages of deglutition. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991. Feb;156(2):293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feinberg MJ, Knebl J, Tully J, Segall L. Aspiration and the elderly. Dysphagia. 1990;5(2):61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leder SB, Suiter DM, Green BG. Silent aspiration risk is volume-dependent. Dysphagia. 2011. Sep;26(3):304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donohue C, Mao S, Sejdić E, Coyle JL. Tracking hyoid bone displacement during swallowing without videofluoroscopy using machine learning of vibratory signals. Dysphagia. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mao S, Sabry A, Khalifa Y, Coyle JL, Sejdić E. Estimation of laryngeal closure duration during swallowing without invasive X-rays. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2021;115:610–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khalifa Y, Donohue C, Coyle JL, Sejdic E. Upper esophageal sphincter opening segmentation with convolutional recurrent neural networks in high resolution cervical auscultation. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donohue C, Khalifa Y, Perera S, Sejdić E, Coyle JL. How closely do machine ratings of duration of UES opening during videofluoroscopy approximate clinician ratings using temporal kinematic analyses and the MBSImP? Dysphagia. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donohue C, Khalifa Y, Mao S, Perera S, Sejdić E, Coyle JL. Establishing reference values for temporal kinematic swallow events across the lifespan in healthy community dwelling adults using high-resolution cervical auscultation. Dysphagia. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shu K, Mao S, Coyle JL, Sejdić E. Improving non-invasive aspiration detection with auxiliary classifier Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z, Coyle JL, Sejdić E. Automatic hyoid bone detection in fluoroscopic images using deep learning. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee HH, Kwon BM, Yang CK, Yeh CY, Lee J. Measurement of laryngeal elevation by automated segmentation using Mask R-CNN. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(51):e28112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eisenhuber E, Schima W, Schober E, et al. Videofluoroscopic assessment of patients with dysphagia: pharyngeal retention is a predictive factor for aspiration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178(2): 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin-Harris B, Brodsky MB, Michel Y, et al. MBS measurement tool for swallow impairment–MBSImp: establishing a standard. Dysphagia. 2008. Dec;23(4):392–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]