Abstract

SH-SY5Y is a cell line derived from human neuroblastoma. It is one of the most widely used in vitro models to study Parkinson’s disease. Surprisingly, it has been found that it does not develop a dopaminergic phenotype after differentiation, questioning its usefulness as a Parkinson’s model. There are other in vitro models with better dopaminergic characteristics. BE (2)-M17 is a human neuroblastoma cell line that differentiates when treated with retinoic acid. We compared the dopaminergic and serotonergic properties of both cell lines. BE (2)-M17 has higher basal levels of dopaminergic markers and acquires a serotonergic phenotype during differentiation while maintaining the dopaminergic phenotype. SH-SY5Y has higher basal levels of serotonergic markers but does not acquire a dopaminergic phenotype upon differentiation.

Keywords: SH-SY5Y cell line, Parkinson’s disease, Dopaminergic neurons, Serotonergic neurons, Staurosporine, Retinoic acid

Highlights

-

•

SH-SY5Y is a cell line derived from human neuroblastoma, it is one of the most used Parkinson’s disease in vitro models.

-

•

It has been found that SH-SY5Y cells do not develop a dopaminergic phenotype after differentiation.

-

•

BE (2)-M17 is a human neuroblastoma cell line that differentiates when treated with retinoic acid or staurosporine.

-

•

BE (2)-M17 has higher basal levels of dopaminergic markers and maintains its dopaminergic phenotype after differentiation.

-

•

SH-SY5Y has higher basal levels of serotonergic markers but does not acquire a dopaminergic phenotype upon differentiation.

-

•

BE (2)-M17 is a better in vitro model to study Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

The second most frequent neurodegenerative disorder is Parkinson’s disease (PD), with Alzheimer’s disease being the most common neurodegenerative disorder (de Lau and Breteler, 2006). PD is characterized by dopamine deficiency linked to the loss of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta and the presence of proteinaceous inclusions called Lewy bodies that are found in the surviving dopaminergic neurons (Family et al., 2013). There are few known genetic and environmental factors that cause PD. These factors include protein aggregation, gene duplication or mutation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and exposure to heavy metals, pesticides, and herbicides (Baba et al., 1998, Landrigan et al., 2005, Sherer et al., 2002, Spillantini and Goedert, 2018). Unfortunately, most of the molecular mechanisms related to the cause or progression of PD continue to be unknown or are not well understood. For these reasons, the improvement and development of different in vitro and in vivo models is necessary to unravel the molecular mechanisms involved in PD pathogenesis. Different types of models are complementary. Animal and patient primary cultures have the advantage that they are not transformed, but the resulting cultures have a limited proliferative capacity and, depending on the cell type and differentiation treatment, can be extremely heterogeneous, thus making the comparison between experiments from cells from different patients or animals or laboratories difficult to reproduce and interpret (Shastry et al., 2001). It is also important to consider the ethical implications of using human samples or experimental animals, and these concerns disappear with the use of established immortalized cell lines. Primary cell cultures are more heterogeneous and harder to transfect; immortalized cell lines are more homogenous, highly proliferative, and easier to transfect, and the transfected colonies can be selected with the appropriate resistance genes, ensuring experimental reproducibility if differentiation conditions are correctly reported (Falkenburger and Schulz, 2006). Immortalized cell lines from human neuroblastoma are an important tool for the study of neurodegenerative diseases. These cell lines are simpler to implement and relatively cheap compared to animal models and patient-derived iPSCs (Ohnuki and Takahashi, 2015).

There are several neuroblastoma-derived cell lines, such as LAN-5, UKE NB-4, IMR-32, UKF NB-1, 2, 3, LAN-2, SK-N-SH, IMR-32, NTE-115 and Neuro2A, that have been used for the study of several important pathologies or cellular processes, including cancer, neurotoxicity, neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, viral infections, apoptosis and neural differentiation, demonstrating that immortalized cells in vitro models are a useful and versatile tool for the study of cellular mechanisms related to PD and neurodegenerative diseases (Falkenburger et al., 2016; Harenza et al., 2017a, Harenza et al., 2017b).

The human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (ATCC CRL-2266) has been widely used in PD research (Xicoy et al., 2017). SH-SY5Y is a thrice cloned subline of the neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-SH, which was established in 1970 from a metastatic bone tumor that originated from sympathetic-adrenergic ganglia (H. R. Xie et al., 2010). The main advantage of this cell line is its capacity to differentiate into neuron-like cells (Kovalevich and Langford, 2013a, Kovalevich and Langford, 2013b). The most common differentiation protocol for this cell line is RA treatment, which is almost always used at a 10 µM concentration with no or very little fetal bovine serum; however, the differentiation time after exposing these cells to the differentiation treatment is very variable in the available literature (Kovalevich and Langford, 2013a, Kovalevich and Langford, 2013b, Baba et al., 1998). According to some reports, the SH-SY5Y cell line has molecular markers that are related to catecholaminergic phenotypes, mainly noradrenergic and dopaminergic, such as dopamine-β-hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (Korecka et al., 2013; Kovalevich and Langford, 2013a, Kovalevich and Langford, 2013b; H. Xie et al., 2010). On the other hand, other reports indicate that in this cell line, there is low or no expression of dopaminergic markers, and there is no significant induction of these markers when differentiated (Cheung et al., 2009, Filograna et al., 2015).

Other immortalized cell lines that share similar properties to SH-SY5Y have not been used as much as SH-SY5Y cells, and as a result, they are not used as often as models for PD. The BE (2)-M17 (ATCC CRL-2267) line is one of these lesser-known models that was cloned from an SK-N-BE (2) neuroblastoma cell line established in 1972 from a bone marrow tumor isolated from a 2-year-old male. BE (2)-M17 cells have previously been used as an in vitro model for PD, as it has been reported that alpha-synuclein expression increases dopamine toxicity in these cells (Bisaglia et al., 2010). Additionally, this cell line exhibits functional exocytosis and has higher basal levels of dopaminergic marker expression that increase after differentiation with retinoic acid (RA) (Andres et al., 2013a, Andres et al., 2013b, Filograna et al., 2015).

The aim of this work was to compare side-by-side and under identical conditions the expression levels of dopaminergic and serotonergic markers in undifferentiated and differentiated SH-SY5Y and BE (2)-M17 cells. We found that the BE (2)-M17 line has robust basal expression of dopaminergic markers that are strongly induced when it is differentiated with RA or staurosporine (Stau), a nonselective protein kinase inhibitor that differentiates SH-SY5Y cells at a concentration of up to 25 nM (Prince and Oreland, 1997). This cell line also expresses serotonergic markers after differentiation. The SH-SY5Y cell line does not express dopaminergic markers before or after RA treatment and only has low levels of serotonergic marker expression before differentiation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The cell lines SH-SY5Y (CRL-2266) and BE (2)-M17 (CRL-2267) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium: nutrient mixture F-12 (Gibco/Life Technologies) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco/Life Technologies) and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco/Life Technologies) and grown in the presence of 5 % CO2 in an incubator at 37 °C. Cells were subcultured at 80–90 % confluence. All experiments were performed at passages 1–7. Images were obtained by phase contrast light microscopy (Olympus CKX31).

Differentiation treatment

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Differentiation was induced at 50 % confluence in both lines using 10 µM RA; the RA concentration was used as reported by Andres et al., 2013a, Andres et al., 2013b and Cheung et al. (2009). The Stau concentration was experimentally determined to be optimal at 10 nM for BE (2)-M17 and 20 nM for SH-SY5Y (Supp. Fig. 1). These concentrations are comparable to those previously reported (Filograna et al., 2015, Prince and Oreland, 1997). In the case of RA treatment, the medium was replaced every 2 days for 6 days or 12 days. In the Stau treatment, the medium was replaced every 2 days for 6 days. Additionally, DMSO (vehicle) at 1 % was used in controls.

Image analysis

Eight-bit grayscale images of cells in culture were acquired using an 8 megapixel resolution camera, using phase contrast optics in an inverted Nikon microscope with a 20 × objective. The images were analyzed using Image Processing and Analysis in Java “ImageJ” software (Schneider et al., 2012). Raw images were converted to 2-bit black and white images using ImageJ’s automatic “Make Binary” process. Once converted to 2 bits, the images were then skeletonized using the skeletonize process. Skeletonized images of 60 cells per condition/cell line were then analyzed using ImageJ’s “Analyze Skeleton” plugin using its default settings. Average maximum branch lengths and their standard deviations were quantified. Significance was determined using ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test (Supplementary Table 1).

Western blot

Total protein extracts were obtained from cells from the corresponding lines and treatments. Three independent biological replicates were performed per cell line and condition. Cells were harvested using 1 × trypsin (Sigma), collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 1400 rpm and resuspended in 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM Tris pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 1 × Complete (Roche), and 100 mM PMSF (Sigma). After resuspension, the cells were lysed by supplementation with SDS at a final concentration of 1 %. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. Lysates were stored at − 20 °C until used. Briefly, 50 µg of protein was loaded in 12 % Laemmli-SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad Mini protean gel electrophoresis system) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 3 h at 250 mA in 25 mM Tris, 190 mM glycine and 20 % methanol. For TH detection, membranes were blocked overnight at 4 °C with PBS 0.1 % Tween (PBST) supplemented with 10 % milk. The membranes were then incubated at 4 °C overnight with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase 1:1000 (Inmunostar Cat #22941) in 5 % milk PBST. For tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) detection, membranes were blocked overnight at 4 °C with PBST supplemented with 5 % BSA. The membranes were then incubated at 4 °C overnight with anti-TPH 1:1000 (Micropore Cat# AB1541) in 5 % BSA PBST. The membranes were then washed 6 times with PBST and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with KPL HPRT goat-antimouse (Sera Care) or KPL HPRT rabbit-antisheep (Zymed) in 5 % milk PBST. Blots were then washed 6 times in PBST, and bands were detected using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Substrate (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blot signals were digitalized and quantified using ImageJ. Mouse monoclonal anti-actin, 1:3000 (Developmental Hybridoma Bank Monoclonal (JLA20)) was used as a loading control.

mRNA expression

To determine the expression levels of DAT, SERT and VMAT2, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments were performed. Total RNA was extracted from treated or untreated cells using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher). A RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher) was used for reverse transcription. RNA was extracted from three independent biological replicates; three technical replicates were performed per sample. qRT-PCR assays were performed with SYBR-Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) in a Step One Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the following parameters: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C and 60 s at 60 °C. Melting curve analysis was performed to determine the reaction specificity of each experiment. The sequence primers used were DAT forward 5´CCT CAA CGA CAC TTT TGG GAC C 3´, DAT reverse 5´AGT AGA GCA GCA CGA TGA CCA G 3´, SERT forward 5´CCT CCA GCC ACT TAT TTC C 3´, SERT reverse 5´CAT CAC CTC CCA TCC ACA TC 3´, VMAT2 forward 5´ CCC AGT GAA GAC AAA GAC CTC 3´, VMAT2 reverse 5´ GCA GAA TCC CGC AAA TAT GG 3´, MAP2 Fwd ‘AGG CTG TAG CAG TCC TGA AAG G′, MAP2 Rev ‘CTT CCT CCA CTG TGA CAG TCT G′, TUJ1 Fwd ‘TCA GCG TCT ACT ACA ACG AGG C′, TUJ1 Rev ‘GCC TGA AGA GAT GTC CAA AGG C′, and GAPDH forward 5 ´GTT CCA ATA TGA TTC CAC CC 3´, GAPDH reverse 5 ´AAG ATG GTG ATG GGA TTT CC 3´ for GAPDH. The ΔΔ CT method was used to determine the relative expression levels of target genes (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). GAPDH was used as an internal reference gene. Three biological and three technical replicates were performed for each cell line and each condition evaluated.

Flow cytometry

Intracellular protein staining was performed as previously described (Maciorowski et al., 2017). Briefly, cells were collected in cytometry tubes, fixed with 2% PFA for 10 min at 37 °C (200 µl), washed and permeabilized with methanol for at least 30 min at 4 °C. Methanol was removed by washing the cells in “FACS Juice” (PBS supplemented with 0.02 % sodium azide and 2 % fetal bovine serum). The cells were then incubated in FACS juice supplemented with the primary antibody: 50 µl anti-TH 1:500 or anti-TPH 1:250 for 15 min at 4 °C, and then the secondary 50 µl antibody anti-mouse Alexa 488 (1:250) or anti-sheep-Alexa 568 (1:250) was added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 45 min at 4 °C, washed, resuspended in 100 µl of 2 % PFA and protected from light until analysis. The samples were acquired using a BD FACSAria Fusion flow cytometer with BD FACSDiva software and analyzed using FlowJo v10.5.3. Ten thousand events were quantified per experiment, and three independent biological replicates were performed for each experiment.

RNA-seq analysis

Raw transcriptomic data were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus under accession numbers GSE89413 (GSM2371253 and GSM2371255) (Harenza et al., 2017b). Sequence quality verification was performed using FastQC-v0.11.7. Reads were aligned using Spliced Transcripts Alignment to Reference (STAR) version 2.4.2 aligner to the Homo sapiens genome (hg19). The aligned sequences were counted using the Python package htseq-count, using the GENCODE file gencode.v36lift37.annotation.gtf as the transcriptome annotation database. Finally, a custom R script was used to generate gene fragments per kilobase of exons per million reads (FPKM) with DESeq2, using a padj < 0.1. The R scripts for the generation of FPKM analyses were based on https://github.com/marislab/NBL-cell-line-RNA-seq (Harenza et al., 2017a, Harenza et al., 2017b).

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between the morphology of cell lines/treatments were determined as follows: skeletonized images of treated and untreated cells were measured using ImageJ. Differences between groups were assessed using ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test of the maximum branch length. Blot signals were digitalized and quantified using ImageJ. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. Tukey's post hoc test was used to assess differences between groups. Flow cytometry experiments were analyzed using FlowJo v10.5.3. Ten thousand events were quantified per experiment, and three independent biological replicates were performed for each experiment. Differences between groups were assessed using ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test. Significance was defined as p < 0.05. All but transcriptomic data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software.

To determine if genes associated with dopaminergic, serotonergic or neural function were significantly induced in reported transcriptomes, aligned sequences were counted using the Python package htseq-count, using the GENCODE file gencode.v36lift37.annotation.gtf as the transcriptome annotation database. Finally, a custom R script was used to generate gene fragments per kilobase of exons per million reads (FPKM) with DESeq2, using a padj < 0.1. The R scripts for the generation of FPKM analyses were based on https://github.com/marislab/NBL-cell-line-RNA-seq.

Results

BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells readily differentiate with RA or Stau treatments

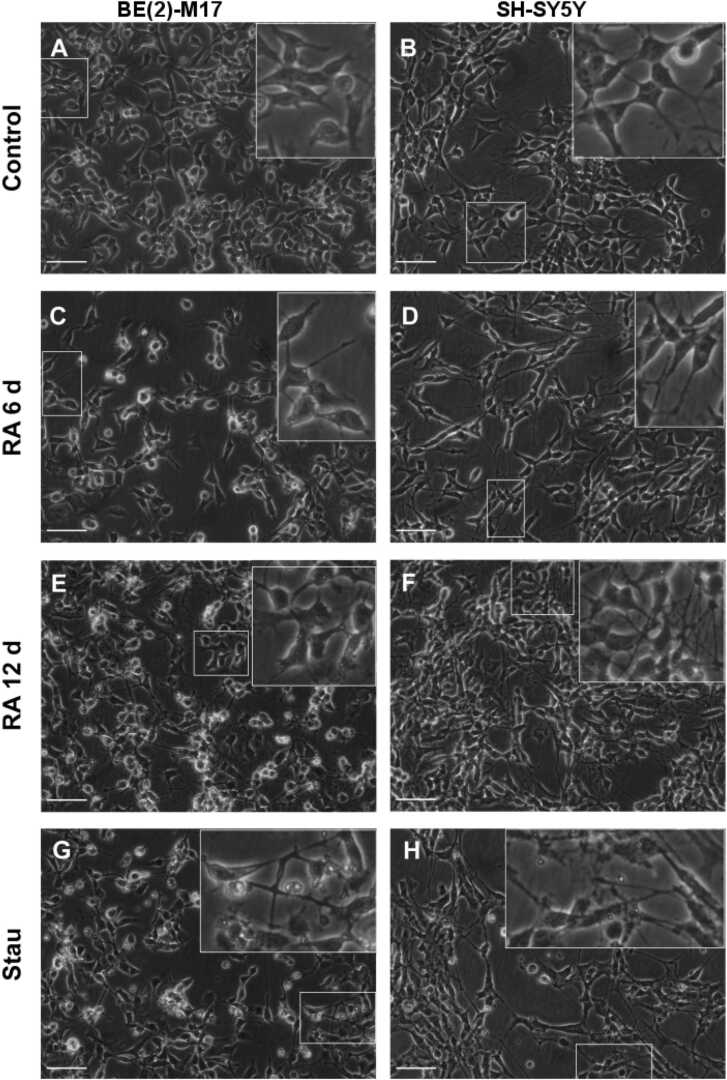

Treatment of BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells with RA (10 µM) or Stau (10 and 20 nM, respectively) completely arrested cell growth in SH-SY5Y cells but had a lesser effect on cell growth in BE (2)-M17 cells. Morphological changes were apparent after six days of treatment with RA, but they were more evident after 12 days. The effect of Stau treatment for 6 days was similar to that obtained after 12 days of RA treatment. We observed that after 12 days of RA treatment or 6 days of Stau treatment, neurites became more robust, and the maximum branch length became significantly shorter after treatment (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). These effects are congruent with what Filograna et al. (2015) reported.

Fig. 1.

Retinoic acid and staurosporine induce morphological changes consistent with neuronal differentiation in BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. A) Untreated BE (2)-M17. B) Untreated SH-SY5Y cells before confluence. C) BE (2)-M17 cells treated with 10 µM RA for 6 days. D) SH-SY5Y cells treated with 10 µM RA for 6 days. E) BE (2)-M17 cells treated with 10 µM RA for 12 days. F) SH-SY5Y cells treated with 10 µM RA for 12 days. G) BE (2)-M17 cells treated with 10 nM Stau for 6 days. H) SH-SY5Y cells treated with 20 nM Stau for 6 days. Neurites become more defined after treatment (inlays). Scale bar = 100 µm, images were acquired using a 20 × objective and phase contrast optics. Inlays show a blow out of the corresponding marked areas.

BE (2)-M17 cells have higher basal tyrosine hydroxylase and tryptophan hydroxylase levels than SH-SY5Y cells

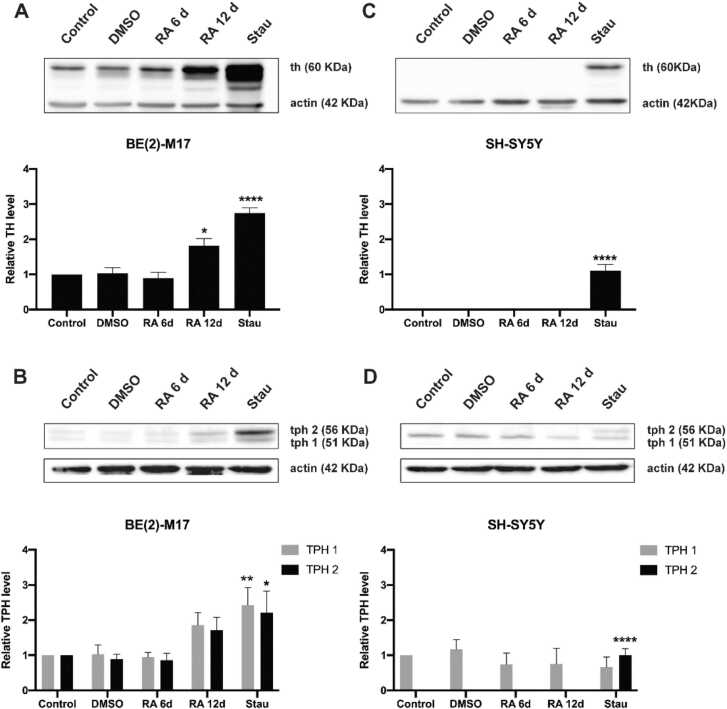

Tyrosine hydroxylase is the limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, and it is considered the most important marker of dopaminergic cells. Western blot analysis of total cell extracts showed that, without treatment, only BE (2)-M17 cells expressed TH. When treated with RA, TH levels were significantly induced in BE (2)-M17 cells after 12 days but remained undetectable in SH-SY5Y cells. When treated with Stau, BE (2)-M17 cells had even higher TH levels than when treated with RA, and the TH induction time was also shorter (6 days). Importantly, SH-SY5Y cells only expressed TH when treated with 20 nM Stau. In all of the conditions tested, TH levels were always higher in BE (2)-M17 cells. Relevantly, the obtained TH levels in SH-SY5Y cells after Stau treatment were at best similar to the predifferentiation TH levels of BE (2)-M17 cells (Fig. 2A and C).

Fig. 2.

Induction of tyrosine hydroxylase and tryptophan hydroxylase determined by western blot of untreated and treated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. A) Induction of TH in BE (2)-M17 cells after treatment with RA and Stau. B) Induction of TPH in BE (2)-M17 cells after treatment with RA and Stau. C) Induction of TH in SH-SY5Y cells after treatment with RA and Stau. D) Induction of TPH in SH-SY5Y cells after treatment with RA and Stau. Two bands appeared in the TPH western blot. The low molecular weight band (TPH1) corresponds to the isoform that is expressed in nonneuronal cells and is irrelevant for this work, while the high molecular weight band (TPH2) is the one involved in neuronal serotonin synthesis. Treatment details and the respective marker are shown for each cell line in the upper part (representative Western blot) and in the lower part (densitometric analysis) of each panel. RA treatment was applied at a concentration of 10 µM in all cases. BE (2)-M17 cells were treated with 10 nM Stau, and SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 20 nM Stau. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA; * P < 0.05, **** P < 0.0001. Error bars = s. e. m. n = 3 biological replicates per cell line and condition.

On the other hand, serotonergic neurons are usually identified by the expression of tryptophan hydroxylase, which is also the limiting enzyme in serotonin synthesis catalyzing the conversion of tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan (Carvajal-Oliveros and Campusano, 2021). TPH has two different isoforms: a low molecular weight isoform (TPH1, isoform 1, 51 kDa), which is not neuronal, and a higher molecular weight isoform (TPH2, isoform 2, 56 kDa), which is characteristic of serotonergic neurons (Sakowski et al., 2006). BE (2)-M17 basally expresses both isoforms, and similar to TH, neural isoform 2 is induced after 6 days of Stau or 12 days of RA treatment. SH-SY5Y cells basally express only the nonneuronal isoform and only express the neuronal isoform (the isoform quantified in Fig. 2B and D) when treated with Stau. The expression of TPH is relatively low in all conditions, with the nonneural isoform being the most common. The neural isoform is only induced after twelve days of RA treatment or when cells are treated with Stau.

The dopaminergic population is enriched in BE (2)-M17 cells, while the serotonergic population is more abundant in SH-SY5Y cells

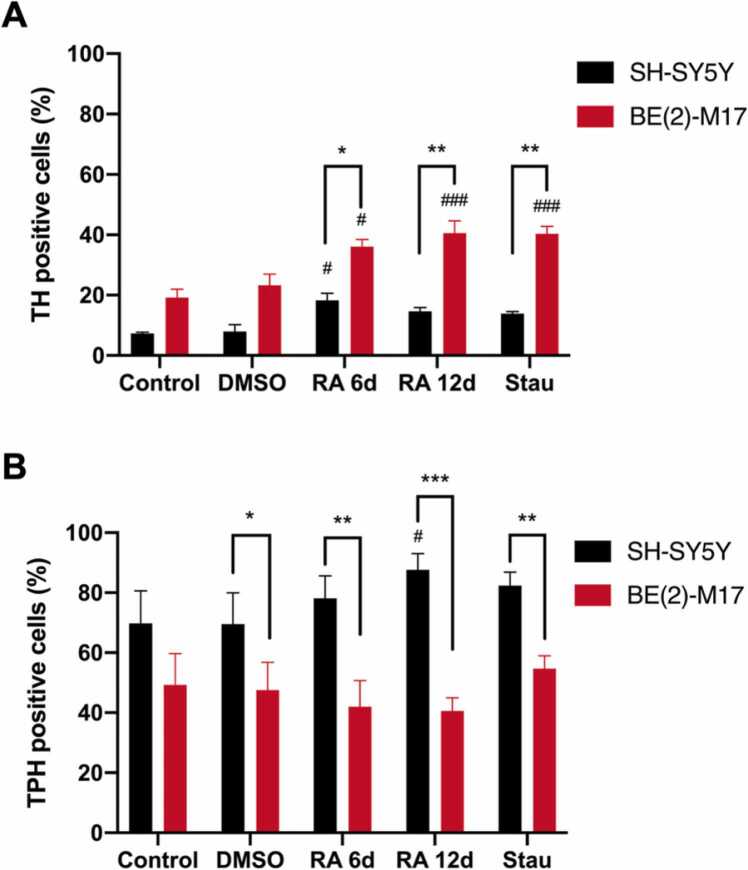

Flow cytometry experiments showed that untreated BE (2)-M17 cells had a higher TH-expressing cell percentage than SH-SY5Y cells and that the percentage increased in BE (2)-M17 cells after RA or Stau treatment. In the case of BE (2)-M17 cells, treatment for 6 days with Stau induced an equivalent percentage of dopaminergic cells to the 12-day RA treatment. In SH-SY5Y cells, the largest population of TH-expressing cells was obtained after 6 days of RA treatment. Regardless of the treatment, the dopaminergic population in SH-SY5Y cells and the amount of TH that they expressed were always smaller than those in the corresponding condition in BE (2)-M17 cells. Conversely, SH-SY5Y cells had in all conditions a higher percentage of serotonergic population than BE (2)-M17 cells; however, as shown in Fig. 2, the TPH-positive population mostly expresses the nonneural isoform (TPH1). In both treatments (RA and Stau), SH-SY5Y cells the population that expresses TPH increased, while in BE (2)-M17 cells the serotonergic population remained constant (Fig. 3 panels A and B).

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry quantification of the dopaminergic and serotonergic populations in undifferentiated and differentiated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. A) Percentage of TH-positive cells after RA and Stau treatment. B) Percentage of TPH (TPH1 and TPH2)-positive cells after RA and Stau. RA treatment was applied at a concentration of 10 µM in all cases. BE (2)-M17 cells were treated with 10 nM Stau, and SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 20 nM Stau. Significance was determined using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Black bars and red bars represent data from SH-SY5Y and BE (2)-M17 cell lines, respectively. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001; # P < 0.05, ### P < 0.001. Asterisks show comparisons between the same treatment and different cell lines, and hash signs show comparisons between the same cell lines and their respective untreated controls. Error bars = s. e. m. n = 3 independent biological replicates, sampling ten thousand events.

The expression levels of MAP2, DAT and VMAT2 neurotransmitter transporters are increased after differentiation in BE (2)-M17 cells

VMAT2 is a nonspecific monoamine transporter that loads dopamine, serotonin and other bioamine neurotransmitters into presynaptic vesicles, so it would be expected to be expressed in differentiated dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons (Koch et al., 2020). DAT is a specific dopamine transporter that recycles dopamine from the synaptic cleft and is also considered a dopaminergic marker. SERT is the equivalent of DAT in serotonergic neurons. Both transporters are considered indispensable parts of the machinery for their respective neurotransmitter systems (Lin et al., 2011). qPCR analysis showed that BE (2)-M17 cells treated with either RA of Stau increased their DAT transcription levels up to four-fold depending on the treatment, and VMAT2 transcription levels up to two hundred-fold depending on treatment, accordingly with dopaminergic differentiation. In these cells RA or Stau treatment also induced the expression of Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2); which is important for neuron development, as it is involved in neuronal determination and stabilization of neuronal morphology (von Bohlen Und Halbach, 2007). On the other hand, treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with either RA or Stau induced the expression of SERT (up to nine-fold when treated with 20 nM Stau) and VMAT2 (up to fifteen hundred-fold when treated with 20 nM Stau), as would be predicted in serotonergic differentiation, treatment of these cells with RA or Stau also induced the expression of the neuron-specific Class III β-tubulin (TuJ1) (Sullivan and Cleveland, 1986) (Fig. 4 panels A–E). Overall, all our results strongly suggest that BE (2)-M17 cells acquire a dopaminergic phenotype and that SH-SY5Y cells become serotonergic.

Fig. 4.

Expression levels of the dopamine (DAT), serotonin (SERT), Class III β-tubulin (TuJ1), Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), and vesicular monoamine (VMAT2) transporters in undifferentiated and differentiated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. A) DAT expression levels in treated and untreated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. B) SERT expression levels in treated and untreated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. C) TuJ1 expression levels in treated and untreated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. D) MAP2 expression levels in treated and untreated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. E) VMAT2 expression levels in treated and untreated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells. RA treatment was applied at a concentration of 10 µM in all cases. BE (2)-M17 cells were treated with 10 nM Stau, and SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 20 nM Stau. Differences in expression levels were determined using the ΔΔCt method. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA; ND = not detectable ** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001. Error bars = s. e. m. n = 3 independent biological replicates with 3 technical replicates each.

Gene profiling analysis identifies differentially expressed genes related to a neuronal phenotype in BE (2)-M17 cells

To further support the hypothesis that BE (2)-M17 cells are predisposed to become dopaminergic neurons, we reanalyzed a transcriptomic database published by Harenza et al. of 39 neuroblastoma cell lines that includes the transcriptomes of undifferentiated BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cell lines (Harenza et al., 2017a). Our analysis shows that transcripts associated with the dopaminergic system, such as TH, SLC18A2, MAP2, NR4A2 and KCNJ6, together with the transcripts MBP, RBFOX3 and NEFL, which are markers of mature neurons, are more abundant in BE (2)-M17 cells, while in SH-SY5Y cells, the transcripts associated with serotonergic neurons, such as TPH and SLC6A4, are enriched. Intriguingly, SH-SY5Y cells strongly expressed the adrenergic markers DBH and NET. Transcriptomic data also corroborate that both cell lines express DDC at similar levels, which is a common marker for dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons (Table 1).

Table 1.

Abundance of transcripts (FPKMa) reported in undifferentiated cells. BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cell lines.

|

Values in FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads)

Discussion

As mentioned in the introduction, PD is an extremely common neurodegenerative disorder, and the risk of developing it increases with age; therefore, as the population ages, the number of PD cases will increase with huge costs to society. There are few genetic and environmental factors involved in PD pathogenesis and progression; however, as the majority of PD cases are idiopathic, most of the causes of this disease are unknown (Dexter and Jenner, 2013, Simon et al., 2020). For these reasons, it is urgent to develop, characterize and perfect in vitro and animal models. The objective of this work was to determine if dopaminergic neurons can be generated from the two immortalized cell lines (BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y) commonly used for the study of Parkinson's disease; using standard differentiation protocols, we investigated the expression levels of genes that are involved in the dopaminergic phenotype and found that BE (2)-M17 cells are a better in vitro model for PD than SH-SY5Y cells, which have been traditionally used for this kind of research. The most important result of this work is that BE2-M17 cells do acquire a dopaminergic phenotype using what is probably the most standard differentiation protocol while SH-SY5Y cells do not. This is a significant finding because it suggests that BE2-M17 cells may be a more suitable model for studying the dopaminergic system than SH-SY5Y cells. Our data show that, as reported before, RA treatment induces differentiation in both cell lines. However, Stau was more effective at differentiating SH-SY5Y cells. Importantly, these two cell lines appear to have divergent differentiation pathways. The BE (2)-M17 cell line basally expresses dopaminergic markers, and their expression is increased upon treatment with either RA or Stau. The SH-SY5Y cell line basally expresses markers that are associated with serotonergic neurons, and correspondingly, these markers are induced after treatment. In both cell lines, Stau induced high levels of VMAT2, a molecule that defines the capacity of a neuron to load neurosecretory vesicles.

There are several problems with the use of SH-SY5Y as a model for PD. First, as mentioned above, this cell line does not have a clear dopaminergic phenotype. Second, there are reports that SH-SY5Y cells become noradrenergic upon differentiation because they begin to express dopamine β-hydroxylase, which converts dopamine into noradrenaline, probably making the interpretation of the results in this model more difficult (Filograna et al., 2015). Finally, there is no consensus in the literature for differentiation protocols used to differentiate this cell line. Approximately 80 % of the reports that use SH-SY5Y do not differentiate it in any way, and approximately 16 % differentiate them with RA or some other supplements; however, the differentiation protocols vary widely. The majority of the reports that differentiate SH-SY5Y cells with RA use it at a concentration of 10 µM; however, differentiation times within these reports also vary widely; for this reason, and to determine if a reasonably short differentiation time would induce the desired phenotype, we studied only the effect of 6 and 12 days treatments (Xicoy et al., 2017). Stau treatment is used in a minority of the reports that use differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Stau is arguably the most efficient differentiation treatment and the only one that in our hands induces modest levels of TH in SH-SY5Y cells but does not induce DAT, and as mentioned before, differentiated SH-SY5Y may express dopamine β-hydroxylase; therefore, this cell line does not acquire a clear dopaminergic phenotype upon differentiation (Filograna et al., 2015). Here, we suggest that although the BE (2)-M17 cell line has been much less used as an in vitro model for dopaminergic disorders such as PD, it is much better suited for this kind of research and that in future reports, the differentiation protocols and induced expression markers should always be reported to assure reproducibility of the results obtained.

The use of immortalized cell lines with defined phenotypes has several advantages: they are easy to acquire, their growth conditions are very standard, and their maintenance is relatively cheap; once a differentiation protocol is established, their phenotypes tend to be very reproducible. We have characterized the effect of a very simple and effective differentiation protocol that only requires 6 days of incubation in standard cultivation media supplemented with either RA or Stau that reliably renders dopaminergic neurons when using BE (2)-M17 cells and serotonergic neurons when using SH-SY5Y cells. Importantly, Alrashidi et al. found that the SH-SY5 cells are serotonergic, as the metabolite 5-HIAA was readily detectable in proliferative and differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. They also showed that despite expressing TH, these cells are inherently dopamine deficient. However, their dopaminergic metabolism becomes stimulated when they are supplemented with L-DOPA, suggesting that this cell line behaves like Parkinson´s diseased cells (Alrashidi et al., 2021). It is important to note that Stau is cytotoxic to BE (2)-M17 cells at a concentration of 20 nM, but it induces their differentiation very efficiently at 10 nM and that SH-SY5Y cells only respond efficiently at a Stau concentration of 20 nM. Although these immortalized cell lines do have limitations, they are an excellent alternative to the use of embryonic stem cells that have limitations of their own, such as higher associated costs, the need for feeder cells, complicated differentiation protocols, low yields of the desired phenotypes and the risk of epigenetic changes, not to mention the ethical concerns that imply obtaining them. The use of patient-derived iPSCs has similar technical and ethical limitations to the ones that embryonic stem cells present (Choumerianou et al., 2008).

The phenotypical divergence observed between BE (2)-M17 and SH-SY5Y cells can be exploited for the development of fine-tuned in vitro models for specific neurological diseases. BE (2)-M17 cells are clearly more adequate for the study of PD and other dopamine-related disorders, while SH-SY5Y cells are probably better suited for the study of serotonin-related diseases such schizophrenia and depression, as differentiation treatment induces the expression of TPH, the enzyme for the limiting step for serotonin synthesis and SERT. Furthermore, it is currently known that PD also has a serotonergic component; thus, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells may become an important model for research on this less known aspect of PD, while BE (2)-M17 cells should be used for the study of the dopaminergic component of the disease.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

A.C.O., M.U.A. and E.R. were responsible for the research design and experimental conception, A.C.O. and M.U.A. performed all experiments. E.M.P. assisted A.C.O. and M.U.A. in flow cytometry experiments. A.C.O., V.N.P., M.Z. and E. R reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by funds from DGAPA/UNAM, PAPIIT-IN206517 and CONACyT Grant 255478. We would also like to thank the National University of México (UNAM).

Ethical approval

No humans or vertebrates were used in this work. The project was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Instituto de Biotecnología and performed according to the ethical guidelines of our institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank M.Sc. René Hernández Vargas and Dr. Iván Sánchez Díaz for technical support, Santiago Becerra for oligonucleotide synthesis, Ing. Roberto Pablo Rodríguez and David Santiago Castañeda of the “Unidad de cómputo of the Instituto de Biotecnología” for computer maintenance and technical support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ibneur.2022.11.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Availability of data and materials

All biological materials are available upon request. All the information generated this work is within the manuscript and its figures, therefore there are no data sets or databases available.

References

- Alrashidi H., Eaton S., Heales S. Biochemical characterization of proliferative and differentiated SH-SY5Y cell line as a model for Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2021;145 doi: 10.1016/J.NEUINT.2021.105009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres D., Keyser B.M., Petrali J., Benton B., Hubbard K.S., McNutt P.M., Ray R. Morphological and functional differentiation in BE(2)-M17 human neuroblastoma cells by treatment with Trans-retinoic acid. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-49/FIGURES/8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres D., Keyser B.M., Petrali J., Benton B., Hubbard K.S., McNutt P.M., Ray R. Morphological and functional differentiation in BE(2)-M17 human neuroblastoma cells by treatment with Trans-retinoic acid. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14(1):49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M., Nakajo S., Tu P.H., Tomita T., Nakaya K., Lee V.M.Y., Trojanowski J.Q., Iwatsubo T. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152(4):879. (/pmc/articles/PMC1858234/?report=abstract) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M., Nakajo S., Tu P.-H., Tomita T., Nakaya K., M-Y Lee V., Trojanowski J.Q., Iwatsubo T., Lee M.-Y., John Trojanowski V.Q. Aggregation of α-synuclein in lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaglia M., Greggio E., Maric D., Miller D.W., Cookson M.R., Bubacco L. α-Synuclein overexpression increases dopamine toxicity in BE(2)-M17 cells. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal-Oliveros A., Campusano J.M. Studying the contribution of serotonin to neurodevelopmental disorders. Can this fly? Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021:14. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.601449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Y.T., Lau W.K.W., Yu M.S., Lai C.S.W., Yeung S.C., So K.F., Chang R.C.C. Effects of all-trans-retinoic acid on human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma as in vitro model in neurotoxicity research. NeuroToxicology. 2009;30(1):127–135. doi: 10.1016/J.NEURO.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choumerianou D.M., Dimitriou H., Kalmanti M. Stem cells: promises versus limitations. Tissue Eng. Part B: Rev. 2008;14(1):53–60. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau L.M., Breteler M.M. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(6):525–535. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter D.T., Jenner P. Parkinson disease: from pathology to molecular disease mechanisms. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;62:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburger B.H., Saridaki T., Dinter E. Cellular models for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2016:121–130. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburger B.H., Schulz J.B. Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders. Springer; Vienna: 2006. Limitations of cellular models in Parkinson’s disease research; pp. 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family A., Gazewood J.D., Richards D.R. Parkinson disease: an update. Am. Fam. Phys. 2013;87(4):267–273. 〈www.aafp.org/afp〉 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filograna R., Civiero L., Ferrari V., Codolo G., Greggio E., Bubacco L., Beltramini M., Bisaglia M. Analysis of the catecholaminergic phenotype in human SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-M17 neuroblastoma cell lines upon differentiation. PLoS One. 2015;10(8) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0136769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harenza J.L., DIamond M.A., Adams R.N., Song M.M., Davidson H.L., Hart L.S., Dent M.H., Fortina P., Reynolds C.P., Maris J.M. Transcriptomic profiling of 39 commonly-used neuroblastoma cell lines. Sci. Data. 2017:4. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harenza J.L., DIamond M.A., Adams R.N., Song M.M., Davidson H.L., Hart L.S., Dent M.H., Fortina P., Reynolds C.P., Maris J.M. Transcriptomic profiling of 39 commonly-used neuroblastoma cell lines. Sci. Data. 2017;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch J., Shi W.-X., Dashtipour K. VMAT2 inhibitors for the treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders. Pharm. Ther. 2020;212 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korecka J.A., van Kesteren R.E., Blaas E., Spitzer S.O., Kamstra J.H., Smit A.B., Swaab D.F., Verhaagen J., Bossers K. Phenotypic characterization of retinoic acid differentiated SH-SY5Y cells by transcriptional profiling. PLoS One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0063862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevich J., Langford D. Considerations for the use of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells in neurobiology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1078:9–21. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-640-5_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevich J., Langford D. Considerations for the use of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells in neurobiology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1078:9–21. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-640-5_2/COVER/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan P.J., Sonawane B., Butler R.N., Trasande L., Callan R., Droller D. Early environmental origins of neurodegenerative disease in later life. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113(9):1230–1233. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Canales J.J., Björgvinsson T., Thomsen M., Qu H., Liu Q.R., Torres G.E., Caine S.B. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Elsevier B.V.; 2011. Monoamine transporters: vulnerable and vital doorkeepers; pp. 1–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciorowski Z., Chattopadhyay P.K., Jain P. Basic multicolor flow cytometry. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2017;117(1) doi: 10.1002/cpim.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuki M., Takahashi K. Present and future challenges of induced pluripotent stem cells. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2015;370(1680) doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince J.A., Oreland L. Staurosporine differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cultures exhibit transient apoptosis and trophic factor independence. Brain Res. Bull. 1997;43(6):515–523. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(97)00328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakowski S.A., Geddes T.J., Thomas D.M., Levi E., Hatfield J.S., Kuhn D.M. Differential tissue distribution of tryptophan hydroxylase isoforms 1 and 2 as revealed with monospecific antibodies. Brain Res. 2006;1085(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9(7):671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shastry P., Basu A., Rajadhyaksha M.S. Neuroblastoma cell lines–a versatile in Vztro model in neurobiology. Int. J. Neurosci. 2001;108(1–2):109–126. doi: 10.3109/00207450108986509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer T.B., Betarbet R., Stout A.K., Lund S., Baptista M., Panov A. v, Cookson M.R., Greenamyre J.T. An in vitro model of Parkinson’s disease: linking mitochondrial impairment to altered α-synuclein metabolism and oxidative damage. J. Neurosci. 2002;22(16):7006–7015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07006.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D.K., Tanner C.M., Brundin P. Parkinson disease epidemiology, pathology, genetics, and pathophysiology. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2020;36(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini M.G., Goedert M. Neurodegeneration and the ordered assembly of α-synuclein. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;373(1):137–148. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2706-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K.F., Cleveland D.W. Identification of conserved isotype-defining variable region sequences for four vertebrate beta tubulin polypeptide classes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83(12):4327–4331. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.83.12.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bohlen Und Halbach O. Immunohistological markers for staging neurogenesis in adult hippocampus. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;329(3):409–420. doi: 10.1007/S00441-007-0432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xicoy H., Wieringa B., Martens G.J.M. The SH-SY5Y cell line in Parkinson’s disease research: a systematic review. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H., Hu L., Li G. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line: in vitro cell model of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Chin. Med. J. 2010;123(8):1086–1092. 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20497720〉 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H.R., Hu L. sen, Li G.Y. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line: in vitro cell model of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Chin. Med. J. 2010;123(8):1086–1092. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

All biological materials are available upon request. All the information generated this work is within the manuscript and its figures, therefore there are no data sets or databases available.