Abstract

Pesticides are a major public health issue connected with excessive use because they negatively impact health and the environment. Pesticide toxicity has been connected to various human illnesses by means of pesticide exposure in direct or indirect ways. A total of 4513 samples of imported fresh fruits were collected from Dubai ports between 2018 to 2020. Their contamination by pesticides was evaluated using gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The display of monitoring results was based on the Maximum Residue Limit (MRL) standard as per the procedures of the European Union. Eighty-one different pesticide residues were detected in the tested fruit samples. In 73.2% of the samples, the pesticide levels were ≥ MRL, while 26.8% were > MRL standards. Chlorpyrifos, carbendazim, cypermethrin, and azoxystrobin were the most frequently detected pesticides in more than 150 samples. Longan (81.4%) and rambutan (66.7%) showed the highest number of imported samples with multiple pesticide residues > MRL. These results highlight the need to continuously monitor pesticide residues in fruits, particularly samples imported into the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Fruit samples with residues > MRL are considered unfit for consumption and prevented from entering commerce in the UAE.

Keywords: LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, Maximum residue limit, Fruit, Organophosphorus

LC-MS/MS; GC-MS/MS; Maximum residue limit; Fruit; Organophosphorus.

1. Introduction

Pesticides are chemical compounds used for preventing, diminishing, or terminating undesirable effects of insects, weeds, fungi, and plant pests. Pesticides are a major public health issue connected with excessive use and can negatively impact health and the environment (WHO, 2018). In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), harsh climatic conditions, shortage of water, and poor soils are obstacles to food production. As a result, the production of fruits consumed in the country accounts for only 20% of the total demand, while the remaining 80% is imported from all over the world (PMA, 2020).

According to the World Health Organization and UNICEF, developing nations account for 20–25% of global pesticide use (Pan, 2012; UNICEF, 2018). These pesticides can easily contaminate the interior of fruits after their direct application by spraying and through soil and water contact (Trapp and Legind, 2011). Heavy and improper use of pesticides can result in significant detrimental health and environmental effects on society (Bakırcı et al., 2014). The widespread use of pesticides in agricultural programs has created extreme health hazards and environmental pollution (Singh et al., 2017). Pesticide toxicity has been connected to various human illnesses characterized by headaches, nausea, rashes, neurotoxicity, cancer, and endocrine dysfunction due to pesticide exposure in direct or indirect ways (Alavanja et al., 2013; Shah, 2020). The presence of pesticide residues has also resulted in environmental issues such as soil contamination, hazards to non-target organisms, bioaccumulation, and biomagnification in the food chain (Hjorth et al., 2011; Ali et al., 2019; Neuwirthová et al., 2019).

Various government and international organizations regulate and monitor the use of pesticides in food commodities to minimize adverse health and environmental risks. Pesticide residues permitted in foods are generally defined by maximum residue limit (MRL) which are expressed in mg kg−1. These are frequently adopted as regional or international standards and have toxicologically-based origins that represent quantities considered to have no toxic effect over a lifetime daily consumption at that level. The number of pesticide poisonings as reported by two main hospitals in Al Ain, UAE in 1999 reached 246 cases of adults and 298 cases of children (Ahmed et al., 2017). In the UAE, pesticide residues in domestically produced or imported foodstuffs have been strictly monitored and MRL are verified and expressed as national and international standards (UAE's GCC Standardization Organization, GSO-125, 1990, CODEX, 2021; EU, 2021).

Numerous studies have reported intensive use of pesticides in fruits, especially by developing countries (Hjorth et al., 2011; Algharibeh; AlFararjeh, 2019; Abd El-Mageed et al., 2020) which are the main exporters of fruits to the UAE. Therefore, it would appear to be prudent to monitor pesticide residues in fruit samples that are imported into the UAE. The objective of the current study was to assess pesticide residues in imported fresh fruits that had entered the UAE through Dubai Emirate ports.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Acetonitrile, anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), anhydrous sodium acetate, glacial acetic acid, graphitized carbon black (GCB), primary and secondary amine exchange material sorbents (PSA), and triphenyl phosphate (TPP) were purchased from Merck GmbH (Darmstadt, Germany). Milli-Q ultra-pure water was prepared using a water purification and dispensing unit (Merck, Milli-Q® IQ Element Water Purification, MA, USA). Chemicals and solvents used in the entire extraction procedures and the mobile phase preparation were carried out using LC-MS/MS reagent grade materials from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Taufkirchen, Germany). Two hundred and sixty-two pesticide reference standards, with purity ranging from 97 to 99%, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH. The preparation method used for pesticide reference standards has been described previously in detail (Osaili et al., 2022).

2.2. Study setting and sample collection

The research was conducted in the Emirate of Dubai, UAE, and in 2020 its population was estimated to be 3.4 million. The Emirate of Dubai has been a center for regional and international trade since the early 20th century (Dubai Statistics Centre, 2020). The UAE is one of the largest net importers of fresh fruits and vegetables in the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region (Syed et al., 2014; Osaili et al., 2022). Fruit samples were collected every day from March 2018 until December 2020 at the Dubai ports. A total of 4513 samples of fresh fruit representing 56 types from 70 countries were collected from containers, refrigerator trucks, or carts at the warehouses. Fruit samples were divided into 6 categories: berries; citrus fruits; melons; pome fruits; stone fruits, and tropical fruits (common and exotic) (Table 1). Samples were collected in the presence of authorized food inspectors from the Dubai municipality, placed in an icebox at 4 °C and immediately transported to the food analysis laboratory. Overall, the sampling methodologies followed were those approved by EU Directive 2002/63/EC (EU, 2002).

Table 1.

Gradient program used in the present study.

| Time (min) | A (%) | B (%) | Flow (ml/min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 80 | 20 | 0.500 |

| 2.00 | 80 | 20 | 0.500 |

| 12.00 | 5 | 95 | 0.500 |

| 21.00 | 5 | 95 | 0.500 |

| 22.00 | 80 | 20 | 0.500 |

| 24.00 | 80 | 20 | 0.500 |

2.3. Sample preparation technique

Unwashed fruit samples weighing 200–250 g were homogenized for 1–3 min using a high-speed blender (Robot Coupe Blixer-2, Robot Coupe Inc., MA, USA). QuEChERS methods were followed; in brief, 15 g homogenized sample was mixed with 15 mL acetonitrile with 1% acetic acid (v/v)in a 50 mL polypropylene tube. Then the tubes were incubated for 30 min at -18 °C. After incubation, 1.5 g anhydrous sodium acetate and 6 g anhydrous MgSO4 were added, mixed for 1 min and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. After centrifugation, 5 mL of supernatant was added to 150 mg of PSA and 900 mg of anhydrous MgSO4 for fruits with low pigment content, or for fruits with high pigment content 5 mL of supernatant was added to 900 mg anhydrous MgSO4, 50 mg of GCB, and 150 mg of PSA. The sample mixture was vortex-mixed for 1 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 rpm. One mL extract and 1 mL of TPP solution (100 μg mL−1 in toluene) in a 10 mL glass tube were evaporated in a nitrogen evaporator to 1 mL by removing the acetonitrile. The resulting extract was filtered using 0.2 μM nylon syringe filters and analyzed using GC-MS/MS for the GC-amenable pesticide residues. For LC-MS/MS analysis, 0.25 mL from final extract sample was diluted with 0.75 mL 0.1% formic acid solution in water and filtered through 0.2 μM nylon syringe filters before injecting into the LC-MSMS.

2.4. LC-MS/MS test conditions

LC-MS/MS analysis was carried out as per the protocol previously described (Osaili et al., 2022). An Agilent 6460 Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (Agilent, CA, USA) equipped with an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (2.1 mm × 150 mm × 3 μm) with autosampler, a binary pump and degasser, and Electrospray Ionization (ESI) source. The mobile phases consisted of a solution (A) containing 0.1% formic acid with water and a solution of 5 mM ammonium formate; and solution (B) containing 0.1% formic acid with methanol plus 5 mM ammonium formate. The gradient elution program was as illustrated clearly in Table 1. The injection volume and the flow rate were 5 μL and 0.5 mL min−1, respectively. The MS parameters included a nebulizer pressure of 45 psi; nitrogen gas temperature: 300 °C; drying gas: 7 L min−1; sheath gas temperature: 250 °C, gas flow: 11 L min−1; capillary spray voltage: 3500 v, and the cycle time was 20 min. Each compound was monitored by multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions in the positive ion mode with delta EMV 300.

2.5. GC–MS/MS test conditions

A gas chromatograph (Agilent, CA, USA, 7890B) equipped with a triple-quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (7010B; Agilent, MS/MS), capillary column (HP-5MS, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) and electron impact (EI) ionization source (GC-MS/MS) was used to measure the concentrations of pesticides (Osaili et al., 2022). In brief, 3.0 μL of the sample was injected in solvent vent injection mode, and a silica liner with 4 mm diameter. The carrier gas was high-purity helium used with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The collision cell gas was high–purity nitrogen at a flow rate of 1.5 mL min−1, while the quench gas, helium, had a flow rate of 4 mL min−1. The oven temperature initially was held at 70 °C for 2 min before being raised to 150 °C min−1, after which the temperature was increased immediately to 200 °C and held for 5 min. Carrier gas was adjusted to a flow rate of 2 mL min−1and the temperature was raised to 280 °C min−1 for 8 min. The temperature was then further increased to 300 °C min−1 for 5 min. The transfer line temperature was 280 °C. The compounds were analyzed using MRM as previously noted.

2.6. Quality control and quality assurance

The selected tests and/or calibrations in the Dubai Municipality laboratories meet the general requirements of ISO/IEC 17025:2005 (ISO, 2005). As per the procedures of the European Union, the method and quality control procedures for pesticide residue analyses in food (or fruits) were validated (true and acceptable) (EU, 2006). The lowest concentration that could be quantified was considered being the limit of quantification (LOQ). A recovery range of about 60–140% was observed with a corresponding mean recovery precision of ±2 x the RSD (%) (EU, 2006). For fruit samples that exceeded the MRL, a second similar analysis was performed to verify the first result. In addition, statistical analysis was conducted in terms of a chi-square test to compare the proportions of fit and unfit condition across the different fruit categories.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Prevalence of pesticides residues in fruits

Out of 262 pesticide reference standards analyzed in the current study, a total of 81 pesticides were present in fruit samples with organophosphorus (44.6%) and pyrethroids (32.1%) being the most commonly found (Table 2). Similarly, Pico et al. (2018) reported that pyrethroids and organophosphorus classes were frequently detected in fruit samples at high concentrations. Worldwide, organophosphorus and pyrethroids are used in agriculture because of their high effectiveness in controlling pests at low cost (Yao et al., 2020). Several studies have found that high levels of organophosphorus pesticide exposure in humans can result in liver and kidney dysfunction as well as cardiac, respiratory, and neuromuscular disorders (Kori et al., 2019; Sealey et al., 2016).

Table 2.

Total number of samples and presence of pesticides found in fruit categories.

| S. No | Food Items (No. of Samples (n = 4513)) | Percent of samples with residues below the MRLs (No. of samples) | Percent of samples with residues above the MRLs (No. of samples) | Pesticides Found | Pesticide Class | Agricultural based uses | PFD∗ | Mean ± Sd (mg kg−1) | MRL (mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Berries (n = 577) | |||||||||

| 1. | Blackberries (25) | 92.0 % (23) | 8.0 % (2) | Propetamphos | Organophosphate | I | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Propiconazole | Triazole | F | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 2. | Blueberry (74) | 97.3 % (72) | 2.7 % (2) | Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorous | I | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Iprodione | Hydantoin | F,N | 1 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 3. | Gooseberry (84) | 46.4 % (39) | 53.6 % (45) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 10 | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Bendiocarb | Carbamates | I | 2 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbendazim | Benzamidizole | F | 4 | 0.40 ± 0.00 | 0.10 | ||||

| Fenpropathrin | Pyrethroids | I | 28 | 0.25 ± 0.39 | 0.01 | ||||

| Monocrotophos | Carbamate | I | 31 | 0.97 ± 0.88 | 0.01 | ||||

| 4. | Grapes (63) | 87.3 % (55) | 12.7 % (8) | Chlorpropham | Carbamate | H | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 2 | 0.65 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Diethofencarb | Carbamate | F | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methomyl | Oxime carbamate | A, I | 2 | 0.9 ± 0.14 | 0.30 | ||||

| Monocrotophos | Carbamate | I | 2 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Myclobutanil | Triazole | F | 1 | 1.53 ± 0.00 | 0.90 | ||||

| Prothiofos | Organophosphate | I | 3 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| 5. | Kiwi Fruit (26) | 96.2 % (25) | 3.8 % (1) | Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, M | 1 | 0.28 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 6. | Raspberries (27) | 96.3 % (26) | 3.7 % (1) | Buprofezin | Thiadiazinanes | I | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 7. | Strawberry (278) | 83.1 % (231) | 16.9 % (47) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 5 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Carbofuran | Carbamate N-methyl | A, I, N | 3 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 2 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.07 | ||||

| Cyprodinil | Anilinopyrimidines | F | 9 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.09 | ||||

| Dichlorvos | Organophosphorus | A,I | 3 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.02 | ||||

| Metalaxyl | Acylalanine | F | 1 | 0.70 ± 0.00 | 0.60 | ||||

| Methamidophos | Organophosphate | A, I | 5 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methomyl | Oxime carbamate | A, I | 3 | 0.13 ± 0.15 | 0.01 | ||||

| Myclobutanil | Triazole | F | 2 | 1.55 ± 0.00 | 0.80 | ||||

| Profenofos | Organophosphorus | A, I | 2 | 0.19 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Propiconazole | Triazole | F | 6 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Pyrimethanil | Anilinopyrimidine | F | 6 | 0.83 ± 0.83 | 0.05 | ||||

| Spiroxamine | Spiroketalamines | F | 6 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| II. Citrus Fruit (n = 299) | |||||||||

| 8. | Grapefruit (5) | 100.0 % (5) | 0.0 | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 9. | Kinoo (2) | 100.0% (2) | 0.0 | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 10. | Kumquat (1) | 100.0% (1) | 0.0 | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 11. | Lemon (91) | 91.2 % (83) | 8.8 % (8) | Bromopropylte | Benzilates | A | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Carbendazim | Benzimidizole | F | 1 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.10 | ||||

| Profenofos | Organophosphorus | I | 2 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| 12. | Lime (76) | 40.8 % (31) | 59.2 % (45) | Ametryn | Triazine | H | 1 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Azinphos Ethyl | Organophosphate | I | 1 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Fenobucarb | Carbamate | I | 3 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.01 | ||||

| Hexaconazole | Triazole | F | 9 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.01 | ||||

| Paclobutrazole | Conazole | F | 13 | 0.13 ± 0.14 | 0.01 | ||||

| Profenofos | Organophosphorus | A, I | 13 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propargite | Unclassified | A | 17 | 0.07 ± 0.08 | 0.01 | ||||

| 13. | Mandarin (22) | 90.9 % (20) | 9.1 % (2) | Imazalil | Imidazole | F | 1 | 13.3 ± 0.00 | 5.00 |

| Triazophos | Organophosphate | A,I | 1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 14. | Oranges (97) | 79.4 % (77) | 20.6 % (20) | Cyfluthrin | Pyrethroids | I | 1 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 9 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Ethion | Pyrethroid | I | 1 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Flutriafol | Triazole | F | 2 | 0.31 ± 0.41 | 0.01 | ||||

| Hexaconazole | Triazole | F | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Imazalil | Imidazole | F | 2 | 18.3 ± 0.00 | 5.00 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A,I | 6 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 15. | Pomelo (5) | 100.0 % (5) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| III. Melons (n = 180) | |||||||||

| 16. | Honey Dew Melon (9) | 100.0 % (9) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 17. | Rock Melon (11) | 100.0 % (11) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 18. | Sweet Melon (19) | 84.2 % (16) | 15.8 % (3) | Chlorfenapyr | Arylepyrole | I | 3 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 19. | Watermelon (141) | 90.8 % (128) | 9.2 % (13) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 8 | 0.45 ± 0.48 | 0.01 |

| Bromopropylate | Benzilates | A | 2 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Imazalil | Imidazole | F | 2 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Methamidophos | Organophosphate | A, I | 6 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methomyl | Oxime carbamate | A, I | 2 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Prochloraz | Imidazole | F | 1 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.03 | ||||

| IV. Pome Fruit (n = 180) | |||||||||

| 20. | Apples (143) | 83.2 % (119) | 16.8 % (24) | Azoxystrobin | Strobilurin | F | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Bromopropylate | Benzilates | A | 6 | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos: | Organophosphorus | A, I, M | 1 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Diazinon: | Organophosphorus | A, I, N | 2 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenpropathrin | Pyrethroid | A, I | 4 | 0.21 ± 0.2 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenvalerate | Pyrethroid | I | 2 | 0.67 ± 0.2 | 0.10 | ||||

| Formetanate | Formamidine | I A | 1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Phosalone | Organophosphate | I A | 4 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Profenophos | Organophosphorus | I | 2 | 0.4 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propargite | Unclassified | A | 2 | 3.86 ± 0.00 | 3.00 | ||||

| Xystrobin | Strobilurin | F | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 21. | Loquat (10) | 70.0 % (7) | 30.0 % (3) | Triadimenol | Triazole | F | 3 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 22. | Pear (22) | 100.0 % (22) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 23. | Quince (1) | 100.0 % (1) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 24. | Wood Apples (4) | 100.0 % (4) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| V. Stone Fruit (n = 415) | |||||||||

| 25. | Avocado (240) | 90.4 % (217) | 9.6 % (23) | Allethrin | Pyrethroid | I | 4 | 1.87 ± 0.32 | 0.01 |

| Azoxystrobin | Strobilurin | F | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Fenazaquin | Quinazoline | A I | 3 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Permethrin | Pyrethroid | I | 14 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | 0.04 | ||||

| 26. | Apricot (16) | 81.3 % (13) | 18.8 % (3) | Bifenthrin | Pyrethroid | A, I | 3 | 0.16 ± 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Iprodione | Hydantoin | F, N | 1 | 0.17 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 27. | Cherries (31) | 93.5 % (29) | 6.5 % (2) | Bendiocarb | Carbamate | I | 2 | 0.2 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Monocrotophos | Carbamate | I | 2 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 28. | Nectarine (12) | 50.0 % (6) | 50.0 % (6) | Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 6 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 4 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 29. | Peaches (86) | 66.3 % (57) | 33.7 % (29) | Anthraquinon | Anhydride | I, F | 12 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, N | 2 | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.08 | ||||

| Deltamethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 4 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 29 | 0.22 ± 0.19 | 0.01 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 11 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| 30. | Plums (15) | 100.0 % (15) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 31. | Prickly Pear (15) | 100.0 % (15) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| VI. Tropical Fruit (Common And Exotic) (n = 2862) | |||||||||

| 32. | Banana (588) | 87.2 % (513) | 12.8 % (75) | Bifenthrin | Pyrethroids | A, I | 2 | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.10 |

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 7 | 0.49 ± 0.21 | 0.20 | ||||

| Chlorfenapyr | Arylepyrole | I | 5 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Demeton-Smethyl Sulfone | Organophosphate | I | 4 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenpropathrin | Pyrethroids | A, I | 2 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Iprodione | Hydantoin | F, N | 5 | 0.24 ± 0.13 | 0.01 | ||||

| Phorate | Organophosphorus | I | 2 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Prochloraz | Imidazole | F | 37 | 0.31 ± 0.22 | 0.05 | ||||

| Pyraclostrobin | Pyrazole | F | 2 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| 33. | Breadfruit (2) | 100.0 % (2) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 34. | Chickoo (44) | 95.5 % (42) | 4.5 % (2) | Imazalil | Imidazole | F | 2 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.05 |

| 35. | Coconut (20) | 100.0 % (20) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 36. | Custard Apple (33) | 93.9 % (31) | 6.1 % (2) | Cyhalothrin Lambda | Pyrethroids | I | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Thiamethoxam | Neonicotinoid | I | 2 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 37. | Dates (4) | 100.0 % (4) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 38. | Dragon Fruit (35) | 71.4 % (25) | 28.6 % (10) | Azoxystrobin | Strobilurin | F | 2 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 4 | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.10 | ||||

| Imazalil | Imidazole | F | 2 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.01 | ||||

| Iprodione | Hydantoin | F, N | 6 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Metalaxyl | Acylalanine | F | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 39. | Fig (31) | 93.5 % (29) | 6.5 % (2) | Propargite | Unclassified | A | 2 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 40. | Guava (249) | 49.4 % (123) | 50.6 % (126) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 3 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Acetamiprid | Neonicotinoid | I | 13 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Azoxystrobin | Strobilurin | F | 30 | 0.11 ± 0.15 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 8 | 0.33 ± 0.17 | 0.1 | ||||

| Chlorfenapyr | Arylepyrole | I | 2 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorpropham | Carbamate | H | 1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, M | 32 | 0.08 ± 0.11 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyfluthrin | Pyrethroids | I | 16 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin | Pyrethroid | I | 3 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin Lambda | Pyrethroids | I | 9 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroid | I | 1 | 0.40 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 16 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.02 | ||||

| Ethion | Pyrethroid | I | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenobucarb | Carbomate | I | 4 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenpropathrin | Pyrethroid | A, I | 4 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.01 | ||||

| Metalaxyl | Acylalanine | F | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methamidophos | Organophosphate | A, I | 1 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methomyl | Oxime carbamate | A, I | 12 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 9 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Profenofos | Organophosphorus | A, I | 22 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Thiamethoxam | Neonicotinoid | I | 3 | 0.13 ± 0.18 | 0.01 | ||||

| Triadiminol | Triazole | F | 8 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 41. | Jack Fruit (20) | 100.0 % (20) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 42. | Jamun (2) | 0.0 % | 100.0 % (2) | Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 2 | 0.2 ± 0.00 | 0.10 |

| 43. | Jujube (35) | 45.7 % (16) | 54.3 % (19) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 1 | 0.40 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Bendiocarb | Carbamates | I | 6 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorfenapyr | Arylepyrole | I | 12 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methamidophos | Organophosphate | A, I | 1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propiconazole | Triazole | F | 6 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 44. | Longan (242) | 18.6 % (45) | 81.4 % (197) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 4 | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Azoxystrobin | Strobolurin | F | 135 | 0.14 ± 0.13 | 0.01 | ||||

| Bifenthrin | Pyrethroid | A, I | 2 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Buprofezin | Unclassified | A, I | 2 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Carbaryl | Carbamate | I | 12 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 96 | 0.89 ± 0.78 | 0.10 | ||||

| Chlorothalonil | Organochloride | F | 9 | 0.88 ± 0.26 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, N | 112 | 0.43 ± 0.24 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin Lambda | Pyrethroids | I | 18 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 33 | 2.55 ± 1.32 | 1.00 | ||||

| Difenoconazole | Triazole | F | 35 | 0.24 ± 0.12 | 0.06 | ||||

| Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 4 | 0.2 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Dimethomorph | Morpholine | F | 7 | 0.1 ± 0.06 | 0.01 | ||||

| Hexaconazole | Triazole | F | 17 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.01 | ||||

| Metalaxyl | Acylalanine | F | 6 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Methamidophos | Organophosphate | A, I | 4 | 0.07 ± 0.07 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methomyl | Oxime carbamate | A, I | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 3 | 0.2 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 8 | 0.18 ± 0.13 | 0.01 | ||||

| Pirimiphos Methyl | Organophosphate | A, I | 4 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propargite | Unclassified | A | 2 | 0.1 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propiconazole | Triazole | F | 6 | 0.16 ± 0.16 | 0.01 | ||||

| Prothiofos | Organophosphate | I | 4 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Pyraclostrobin | Pyrazole | F | 29 | 0.17 ± 0.25 | 0.02 | ||||

| Tetraconazole | Triazole | F | 2 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| 45. | Lychee (12) | 66.7 % (8) | 33.3 % (4) | Chlorothalonil | Organochloride | F | 2 | 0.38 ± 0.40 | 0.01 |

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, M | 1 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Diflubenzuron | Benzoylurea | I | 1 | 0.72 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Tebuconazole | Triazole | F | 1 | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| 46. | Mangoes (593) | 82.0 % (486) | 18.0 % (107) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 10 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Acetamiprid | Neonicotinoid | I | 1 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Bendiocarb | Carbamates | I | 3 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Boscalid | Carbaxomide | F | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 1 | 1.10 ± 0.00 | 0.10 | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, N | 36 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyfluthrin | Pyrethriods | I | 9 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin (Lambda) | Pyrethroids | I | 1 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 1 | 1.90 ± 0.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Difenconazole | Triazole | F | 2 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.07 | ||||

| Fenobucarb | Carbamate | I | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenpropathrin | Pyrethroids | A, I | 3 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fludioxonil | Phenylpyrole | F | 2 | 10.0 ± 0.00 | 2.00 | ||||

| Hexaconazole | Triazole | F | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Metalaxyl | Acylalanine | F | 1 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methomyl | Oxime carbamate | A, I | 1 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Monocrotophos | Carbamate | I | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Myclobutanil | Triazole | F | 1 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 8 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Phenthoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 4 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propiconazole | Triazole | F | 4 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Quinalphos | Organophosphate | I | 6 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Triazophos | Organophosphate | A, I | 8 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 47. | Mangosteen (11) | 100.0 % (11) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 48. | Marian Plum (Gandaria) (1) | 0.0 % | 100.0 % (1) | Chlorothalonil | Organochloride | F | 1 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 49. | Papaya (258) | 76.4 % (197) | 23.6 % (61) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 4 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Acetamiprid | Neonicotinoid | I | 11 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbaryl | Carbamate | I | 1 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 9 | 0.31 ± 0.22 | 0.14 | ||||

| Carbofuran | Carbamate N-methy | A, I, N | 12 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyfluthrin | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin Lambda | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Deltamethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 4 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenpropathrin | Pyrethroids | I | 4 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Kresoxim | Strobilurin | F, B | 6 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Procymidone | Dicoboximide | F | 4 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Pyridaben | Organochlorine | I | 1 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Thiamethoxam | Neonicotinoid | I | 2 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.01 | ||||

| 50. | Passionfruit (94) | 54.3 % (51) | 45.7 % (43) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 1 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 7 | 0.29 ± 0.14 | 0.10 | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, N | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyhahothrin Lambda | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin | Pyrethroids | I | 10 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyretheroids | I | 9 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Diazinon | Organophosphorus | A, I, N | 6 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Difenoconazole | Triazole | F | 3 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 3 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Metalaxyl | Acylalanine | F | 13 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Monocrotophos | Carbamate | I | 3 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Permethrin | Pyrethroid | I | 1 | 1.07 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| 51. | Persimmon (37) | 56.8 % (21) | 43.2 % (16) | Acetamiprid | Neonicotinoid | I | 3 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, N | 4 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.05 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 1 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 10 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 7 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| 52. | Pineapple (126) | 92.1 % (116) | 7.9 % (10) | Chlorothalonil | Organochloride | F | 4 | 3.98 ± 1.35 | 0.01 |

| Pyraclostrobin | Pyrazole | F | 2 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| 53. | Pomegranate (163) | 52.1 % (85) | 47.9 % (78) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 7 | 0.10 ± 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Acetamiprid | Neonicotinoid | I | 7 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Azoxystrobin | Strobilurin | F | 7 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Bifenthrin | Pyrethroid | A, I | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Boscalid | Carboxamide | F | 1 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 5 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.1 | ||||

| Carbofuran | Carbamate N-methyl | A, I, N | 4 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorothalonil | Organochloride | F | 4 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, M | 15 | 0.09 ± 0.09 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyfluthrin | Pyrethroids | I | 6 | 0.17 ± 0.4 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin | Pyrethroids | I | 6 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin Lambda | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.22 ± 0.16 | 0.01 | ||||

| Deltamethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 10 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Difenoconazol | Triazole | I | 5 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.1 | ||||

| Dimethoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Dimethomorph | Morpholine | F | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Ethion | Pyrethroids | I | 1 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenpropathrin | Pyrethroids | A, I | 22 | 0.20 ± 0.22 | 0.01 | ||||

| Hexaconazole | Triazole | F | 7 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Iprovalicarb | Carbamate | F | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Metalaxyl | Acylalanine | F | 5 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methamidophos | Organophosphate | A, I | 3 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methomyl | Oxime carbamate | A, I | 1 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Monocrotophos | Carbamate | I | 6 | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Omethoate | Organophosphate | A, I | 9 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Phenthoate | Organophosphorus | A, I | 3 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propamocarb | Carbamate | F | 3 | 0.19 ± 0.14 | 0.01 | ||||

| Propargite | Unclassified | A | 2 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Pyraclostrobin | Pyrazole | F | 4 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Tebuconazole | Triazole | F | 3 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||

| Thiamethoxam | Neonicotinoid | I | 1 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| 54. | Rambutan (252) | 33.3 % (84) | 66.7 % (168) | Acephate | Organophosphorus | I | 2 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Acetamiprid | Neonicotinoid | I | 8 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Azoxystrobin | Stribilurin | F | 2 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Bitertanol | Triazole | F | 2 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Boscalid | Carboxamide | F | 2 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Buprofezin | Unclassified | A, I | 2 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | F | 67 | 0.56 ± 0.00 | 0.10 | ||||

| Chlorfenapyr | Arylepyrole | I | 1 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus | A, I, M | 39 | 0.07 ± 0.07 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin | Pyrethroids | I | 3 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cyhalothrin Lambda | Pyrethroids | I | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroids | I | 139 | 0.4 ± 0.51 | 0.10 | ||||

| Deltamethrin | Pyrethroid ester | I | 2 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Etofenprox | Pyrethroid | I | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fenarimol | Triazole | I | 2 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| Hexaconazole | Organophosphate | F | 21 | 0.09 ± 0.15 | 0.01 | ||||

| Methamidophos | Pyrethroids | A, I | 2 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Permethrin | Pyrethroid | I | 1 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| Dimethomorph | Morpholine | F | 2 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Prothiofos | Organochlorine | I, A | 1 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Pyridaben | Pyridazinone | F | 1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Tetraconazole | Traizole | F | 1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||

| 55. | Soursop (2) | 100.0% (2) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

| 56. | Tamarind (8) | 100.0% (8) | 0.0 % | ND | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

A- Acaricide; F- Fungicide; H- Herbicide; I- Insecticide; M- Milicide; N- Nematicide; ∗PFD- Pesticide Frequency number of Detection; ND- Not Detected; NA- Not Applicable.

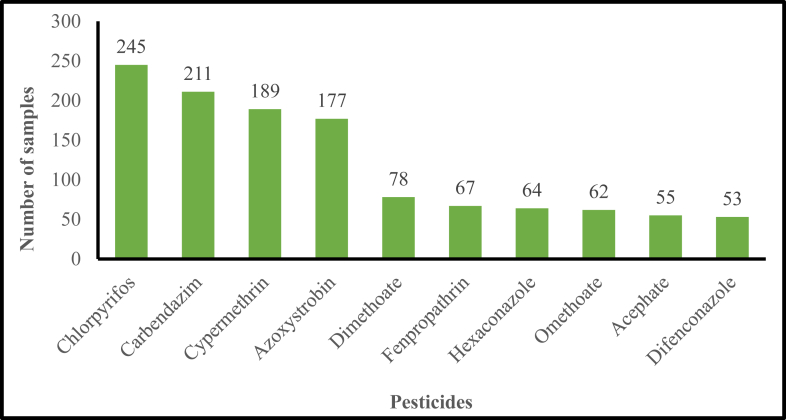

Chlorpyrifos, carbendazim, cypermethrin, and azoxystrobin were frequently found in the tested fruit samples at concentrations above the MRL (Figure 1). Similar to our findings, Bakırcı et al. (2014) reported that levels of chlorpyrifos, carbendazim, and cypermethrin were predominantly above their MRL in fruit samples analyzed. A number of studies have found that fruit samples frequently had significant quantities of chlorpyrifos residues above the MRL (Hjorth et al., 2011; Mebdoua et al., 2017; Mojsak et al., 2018; Mac Loughlin et al., 2018). Chlorpyrifos is moderately toxic to humans, because it inhibits acetylcholinesterase (an enzyme involved in neural signal transmission) and can also affect the neuroendocrine development of unborn and newborn children (Burke et al., 2017). Very high exposures to chlorpyrifos can lead to chronic kidney disease, respiratory paralysis, and death (Yang et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Frequency of the most commonly detected pesticides in fruit samples.

Slightly less than 3/4 of the fruit samples (73.2%) were found to be contaminated with different pesticide residues at concentrations ≤ MRL, whereas 26.8% of samples were found contaminated with pesticide residues at concentrations > MRL. The present results are similar to those of Ciscato et al. (2009) who found 23.2% of fruit samples from Brazil contained pesticide residues > MRL. In another study, Jallow et al. (2017) reported pesticide residues > MRL in 54.4% of fruit samples collected from Kuwait, however, the number of samples tested was small (n = 46), and results may not accurately reflect the true level of pesticide residues in fruits in the country. In the present study, fruits with pesticide residues > MRL included: berries at 18.4%, citrus fruits at 25.1%, melons at 8.9%, pome fruits at 15.0%, stone fruits at 15.2% and tropical fruits at 32.3%. Tropical and citrus fruits showed the highest percentage of pesticide residues compared to the others. These findings are in agreement with the earlier study by Ciscato et al. (2009) who found that 13.4% of tropical fruits (figs, persimmons and papaya) in Brazil had pesticide concentrations > MRL. In other work conducted regionally, pesticide residues > MRL were found in 68.2% of citrus fruits examined in Jordan (Al-Nasir et al., 2020). It was notable that with samples of citrus and tropical fruits in the present study the proportion of unfit samples because of pesticide residues > MRL was substantially higher than desirable and the results illustrated a significant difference between proportions/percentages across all fruit categories at p < 0.001 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of fruit samples in different categories with pesticide residues below/above the MRLs. Below or at the MRLs: pesticide-free/with amounts below LOQ or samples with pesticides below MRLs. a,b Different letters indicate significant differences in the proportions of fit and unfit samples across the different fruit categories (p < 0.001).

The fruit samples tested in the current study were imported from 70 countries (Table 3) and samples from 34 countries had detectable pesticide residues. The majority of fruits (>200 samples) were imported from countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines, Egypt, India, Kenya, Iran and Sri Lanka. The number of imported samples from these countries was generally high because they are geographically near the UAE ports. In addition, the majority of tropical fruits (>150 samples), came from each of these countries as well, except that the number analyzed from Iran was quite small at 5 samples. The percentage of fruit samples imported from these 8 countries with pesticide residues > MRL were: 61.1% of those from Vietnam; 58.2% from Thailand; 25.8% from the Philippines; 23.0% from Egypt; 21.6% from India; 19.8% from Kenya; 16.7% from Iran, and 10.8% from Sri Lanka. In particular, the tropical fruit category from these countries showed a higher percentage of MRL exceedance with the exception of pome fruits imported from Iran. The results of the current study confirm previous findings on pesticide residues in imported vegetable samples that found most of the contaminated samples were imported to the UAE from developing countries (Osaili et al., 2022).

Table 3.

Main fruit categories grouped according to country of origin.

| Country of Origin | Berries | Citrus Fruit | Melons | Pome Fruit | Stone Fruit | Tropical Fruit | No. of samples with residues below the MRLs | No. of samples with residues above the MRLs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 13 | 13 | 13 | ||||||

| Algeria | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Argentina | 5 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 29 | 4 | 33 | ||

| Australia | 27 | 6 | 22 | 6 | 16 | 64 | 13 | 77 | |

| Bangladesh | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||||||

| Belgium | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Bolivia | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Brazil | 1 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 21 | 1 | 22 | ||

| Canada | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Chile | 7 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 11 | ||||

| China | 9 | 25 | 15 | 36 | 13 | 49 | |||

| Colombia | 1 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 9 | ||||

| Ecuador | 49 | 47 | 2 | 49 | |||||

| Egypt | 114 | 15 | 17 | 171 | 244 | 73 | 317 | ||

| Ethiopia | 31 | 2 | 20 | 13 | 33 | ||||

| France | 9 | 9 | 9 | ||||||

| Georgia | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Germany | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Ghana | 10 | 6 | 4 | 10 | |||||

| Greece | 11 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 18 | 18 | |||

| Honduras | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| India | 97 | 7 | 28 | 8 | 773 | 716 | 197 | 913 | |

| Indonesia | 72 | 64 | 8 | 72 | |||||

| Iran | 12 | 43 | 93 | 56 | 5 | 174 | 35 | 209 | |

| Israel | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Italy | 7 | 10 | 1 | 18 | 18 | ||||

| Jordan | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Kenya | 79 | 168 | 198 | 49 | 247 | ||||

| Korea (South) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Lebanon | 13 | 42 | 12 | 26 | 35 | 90 | 38 | 128 | |

| Macedonia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Madagascar | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Malaysia | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 9 | ||||

| Mauritius | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | |||||

| Mexico | 21 | 1 | 95 | 92 | 25 | 117 | |||

| Morocco | 23 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 36 | 2 | 38 | ||

| Mozambique | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Namibia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Netherlands | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| New Zealand | 2 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| Nigeria | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Oman | 16 | 13 | 48 | 74 | 3 | 77 | |||

| Pakistan | 9 | 4 | 2 | 78 | 82 | 11 | 93 | ||

| Palestine | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Peru | 18 | 2 | 7 | 26 | 1 | 27 | |||

| Philippines | 3 | 206 | 155 | 54 | 209 | ||||

| Poland | 4 | 1 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Portugal | 5 | 1 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Rwanda | 17 | 17 | 17 | ||||||

| Senegal | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Serbia | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| Slovenia | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| South Africa | 59 | 24 | 8 | 13 | 16 | 111 | 9 | 120 | |

| Spain | 5 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 27 | 27 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 13 | 209 | 198 | 24 | 222 | ||||

| Swaziland | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Syria | 1 | 10 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 12 | |||

| Tajikistan | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Tanzania | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Thailand | 1 | 2 | 641 | 269 | 375 | 644 | |||

| Tunisia | 6 | 1 | 2 | 72 | 11 | 56 | 36 | 92 | |

| Turkey | 4 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 29 | 1 | 30 | |

| Uganda | 22 | 4 | 26 | 26 | |||||

| Ukraine | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| UK | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| USA | 77 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 80 | 16 | 96 | |

| Uzbekistan | 1 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 12 | |||

| Vietnam | 73 | 2 | 2 | 216 | 114 | 179 | 293 | ||

| Yemen | 9 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |||||

| Zimbabwe | 10 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 14 | ||||

| Grand Total | 577 | 299 | 180 | 180 | 415 | 2862 | 3303 | 1210 | 4513 |

3.2. Pesticide residues in berries

Samples in the berry category were found to be contaminated with pesticide residues > MRL from a low of 2.7% for blueberries, to 16.9% for strawberries and then 53.6% in gooseberries. A study carried out in Poland by Matyaszek et al. (2013) found that 58.4% of gooseberry samples contained pesticide residues > MRL. Among these, the concentrations of difenoconazole and propiconazole were 0.31 and 0.08 mg kg−1, respectively. The major pesticides in gooseberry samples imported from India included fenoprotharin and monocrotophos with mean concentrations of 0.25 and 0.97 mg kg−1, respectively. Bakırcı et al. (2014) found that 9% of strawberry samples contained pesticide residues > MRL, which was slightly lower than the results in the current study, but the most common pesticide found in the current and the previous study was dichlorvos where the mean concentration in both studies was found to be 0.08 mg kg−1 (>MRL). Furthermore, 21% of the grape samples in the Bakırcı et al. (2014) study that exceeded the MRL contained a mean concentration of 1.4 mg kg−1 methomyl, whereas the mean concentration of methomyl in the present study was 0.9 mg kg−1.

3.3. Pesticide residues in citrus fruits

In the citrus fruit category, 25.1% of the samples exceeded the MRL. After tropical fruit it was the second-largest category which exceeded the MRL during the course of the present study. Of 8 different samples examined, lemon, lime, mandarin, and orange showed pesticide residues > MRL. Bakırcı et al. (2014) reported that 26% of lemon samples contained pesticide residues. In comparison to the above study, the results from the current work showed 8.8% of lemon samples contained pesticide residues above the MRL, although this category had the lowest concentrations of pesticide residues among all tested fruit. An exception was the finding that 59.2% of lime samples had pesticide residues > MRL. Propargite and profenos residues were the most dominant pesticides with mean concentrations of 0.07 and 0.06 mg kg−1, respectively. The higher concentrations may have been due to some farmers violating regulations or not following the proper precautions as in the case of propargite, since it is not authorized by the European Union to be used on crops (EU, 2015; Algharibeh and AlFararjeh, 2018). Furthermore, the current study showed that 20.6% of orange samples contaminated with pesticide residues (dimethoate and omethate) exceeded the MRL. As with the current study, pesticide residues in 30% of the orange samples in the Argentine domestic market were found to be > MRL (Mac Loughlin et al., 2018). Suárez-Jacobo et al. (2017) found that a total of 11% orange samples in Mexico exceeded the EU MRL including dimethoate (1%), malathion (5%), chlorpyrifos-ethyl (1%), and methidathion (4%).

3.4. Pesticide residues in melons

With pesticide residues > MRL in 8.9% of samples, the melon category represented the lowest levels of all categories tested. However, it was found that 15.8% of sweet melons contained chlorfenapyr residues at a mean concentration of 0.02 mg kg−1. In contrast, all (100%, n = 25) melon samples analyzed from Jordan contained pesticide residues that were < MRL (Algharibeh and AlFararjeh 2019). Of watermelon samples, 9.2% were found to contain multiple (>2) pesticide residues, and these were largely acephate (0.45 mg kg−1) and methamidophos (0.06 mg kg−1) and found in the same tissue samples. According to recent pesticide classification, acephate and methamidophos are considered to be moderately dangerous (Class II) (WHO, 2020). In contrast to the present study, Jallow et al. (2017) found 50% of watermelon samples from Kuwait had multiple pesticide residues > MRL. The most frequent pesticides found in their study were deltamethrin (0.06–0.29 mg kg−1), imidacloprid (not detected to 0.23 mg kg−1), and monocrotophos (not detected to 0.02 mg kg−1).

3.5. Pesticide residues in pome fruit

About 17% of the imported apple samples contained 11 different pesticide residues > MRL. Several studies from different countries have also reported multiple pesticide residues in apples exceeded the MRL, ranging from 0.45 to 80% (Abd El-Mageed et al., 2020; Bakırcı et al., 2014; Mebdoua et al., 2017; Hjorth et al., 201; Jallow et al., 2017). It is thought that multiple residues in apples occur because their production is unquestionably associated with high pesticide use in various parts of the world in concert with conventional production methods (Lozowicka and Kaczyński, 2011). In contrast, 100% of pears, quinces, and wood apples examined in the current study were found to contain pesticide residues ≤ MRL, although Bakırcı et al. (2014) found that 9.7% of pear samples contained pesticide residues (imidacloprid, 0.54 mg kg−1, and lambda-cyhalothrin, 0.47 mg kg−1) > MRLs.

3.6. Pesticide residues in stone fruit

Pesticide residues > MRL were found in 50% of nectarines, 33.7% of peaches, 18.8% of apricots, 9.6% of avocados and 6.5% of cherries. Among the pesticides detected, dimethoate and omethate were in the highest concentrations and were found in nectarines at 0.20 and 0.02 mg kg−1 and in peaches at 0.22 and 0.05 mg kg−1, respectively. As in the present study, Mebdoua et al. (2017) reported that 50% of nectarines and 35% of peaches were contaminated with chlorpyrifos and metalaxyl at levels > MRL. Again, similar to the findings here, most of the pesticides found were in the organophosphorus class, which are used widely as an insecticide in both nectarine and peach cultivation (Fytianos et al., 2006). It was notable that plum and prickly pear samples were below the MRL. Lozowicka et al. (2016) concluded that stone fruits, including cherries, peaches, and plums had not been exposed to pesticide contamination because only 0.4% exceeded the MRL.

3.7. Pesticide residues in tropical fruit

The proportion of samples in the tropical fruit group category containing pesticides > MRL was 32.3% higher than other categories. Of the 25 types of tropical fruits in this category, 100.0% of Jamun and marian plum, 81.4% of longan, 66.7% of rambutan, 54.3% of jujube and 50.6% of guava had residues > MRL. Chlorpyrifos, carbendazim, cypermethrin, and azoxystrobin were detected in the majority of the samples tested in this fruit category. The pesticides detected in the current study suggest that they were used at pre-harvest stages as an insecticide and fungicide through plant-by-plant application to protect the fruit (Gentil-Sergent et al., 2021). Again, in the tropical fruit group, 81.4% of longan and 66.7% of rambutan also showed the highest number of imported samples with multiple pesticide residues > MRL. It is probable that competitive pressures in modern horticulture practice to protect entire fruit orchards from various pests and enhance the cultivation of fruits contributed to the results observed (Liu et al., 2016).

4. Conclusion

The present study explored the levels of pesticide residues in a cross-section of all fruits imported to the UAE via Dubai ports. In 73.2% of fruit samples, pesticide levels were ≥ MRL, while 26.8% were > MRL standards. Chlorpyrifos, carbendazim, cypermethrin, and azoxystrobin were the pesticides most frequently detected > MRL and were found in >150 samples. Greatest frequencies of imported fruit contamination were found in longan (81.4% or 197 of 242 samples) and rambutan (66.7% or 168 of 252 samples). The results clearly emphasize the need for regular pesticide residue monitoring programs to ensure that imported foods are safe for human consumption.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Tareq Osaili; Reyad Obaid: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Maryam S. Al Sallagi; Wael A. M. Bani Odeh; Hajer J. Al Ali; Ahmed A. S. A. Al Ali: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Dinesh K. Dhanasekaran: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Leila C. Ismail; Richard Holley: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Khadija O. Al. Mehri; Vijayan A. Pisharath: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

The work was supported by the Dubai Municipality.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Univeristiy of Sharjah, UAE.

References

- Abd El-Mageed N.M., Abu-Abdoun I.I., Janaan A.S. Monitoring of pesticide residues in imported fruits and vegetables in the United Arab Emirates during 2019. Int. Res. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020;21(23):239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed J., Maraqa M., Hasan M., Al-Marzouqi M. Management of pesticides in the United Arab Emirates. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2017;16(1):15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nasir F.M., Jiries A.G., Al-Rabadi G.J., Alu'datt M.H., Tranchant C.C., Al-Dalain S.A., et al. Determination of pesticide residues in selected citrus fruits and vegetables cultivated in the Jordan Valley. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2020;123 [Google Scholar]

- Alavanja M.C., Ross M.K., Bonner M.R. Increased cancer burden among pesticide applicators and others due to pesticide exposure. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2013;63(2):120–142. doi: 10.3322/caac.21170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algharibeh G.R., AlFararjeh M.S. Pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables in Jordan using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Food Addit. Contam. B. 2018;12(1):65–73. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2018.1548505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N., Khan S., Li Y., Zheng N., Yao H. Influence of biochars on the accessibility of organochlorine pesticides and microbial community in contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;647:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PMA PMA Fresh Produce Industry: United Arab Emirates. 2020. https://www.pma.com/-/media/pma-files/research-and-development/uaepresentationletter_v2_rev121919.pdf?la=en Retrieved from.

- Bakırcı G.T., Acay D.B.Y., Bakırcı F., Ötleş S. Pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from the Aegean region, Turkey. Food Chem. 2014;160:379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R.D., Todd S.W., Lumsden E., Mullins R.J., Mamczarz J., Fawcett W.P., et al. Developmental neurotoxicity of the organophosphorus insecticide chlorpyrifos: from clinical findings to preclinical models and potential mechanisms. J. Neurochem. 2017;142:162–177. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciscato C.H.P., Bertoni Gebara A., Henrique Monteiro S. Pesticide residue monitoring of Brazilian fruit for export 2006–2007. Food Addit. Contam. 2009;2(2):140–145. doi: 10.1080/19440040903330326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CODEX. 2021. http://www.fao.org/fao-whocodexalimentarius/codextexts/dbs/pestres/pesticides/en/

- Dubai Statistics Centre . Government of Dubai; 2020. Population and Vital Statistics.https://www.dsc.gov.ae/Report/DSC_SYB_2020_01_03.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- EU Commission . Vol. 2. 2002. Commission directive 2002/63/EC of 11 July 2002 establishing community methods of sampling for the official control of pesticide residues in and on products of plant and animal origin and repealing directive 79/700/EEC; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- EU Commission Commission amending regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council to establish Annex I listing the food and feed products to which maximum levels for pesticide residues apply (Off. J. E.U).EU (2021). EU pesticide residues database for all the eupropean union-MRLs. 2006. https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/mrls/?event=search.pr

- EU Commission Commission regulation (EU) 2015/400 of 25 February 2015 amending annexes II, III and V to regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European parliament and of the council as regards maximum residue levels for bone oil, carbon monoxide, cyprodinil, dodemorph, iprodione, metaldehyde, metazachlor, paraffin oil (CAS 64742-54-7), petroleum oils (CAS 92062-35-6) and propargite in or on certain products. Jeu L. 2015;71:56–113. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015R0400&qid=1430383915086&from=EN [Google Scholar]

- Fytianos K., Raikos N., Theodoridis G., Velinova Z., Tsoukali H. Solid phase microextraction applied to the analysis of organophosphorus insecticides in fruits. Chemosphere. 2006;65(11):2090–2095. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentil-Sergent C., Basset-Mens C., Gaab J., Mottes C., Melero C., Fantke P. Quantifying pesticide emission fractions for tropical conditions. Chemosphere. 2021;275 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GSO-125 Methods of sampling fresh fruits and vegetables. 1990. https://www.gso.org.sa/store/standards/GSO:477749/file/2032/preview Available:

- Hjorth K., Johansen K., Holen B., Andersson A., Christensen H.B., et al. Pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from South America–A Nordic project. Food Control. 2011;22(11):1701–1706. [Google Scholar]

- ISO . International Standards Organization; Geneva: 2005. General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. [Google Scholar]

- Jallow M.F., Awadh D.G., Albaho M.S., Devi V.Y., Ahmad N. Monitoring of pesticide residues in commonly used fruits and vegetables in Kuwait. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2017;14(8):833. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kori R.K., Hasan W., Jain A.K., Yadav R.S. Cholinesterase inhibition and its association with hematological, biochemical and oxidative stress markers in chronic pesticide exposed agriculture workers. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2019;33(9) doi: 10.1002/jbt.22367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Li S., Ni Z., Qu M., Zhong D., Ye C., Tang F. Pesticides in persimmons, jujubes and soil from China: residue levels, risk assessment and relationship between fruits and soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;542:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łozowicka B.O., Kaczyński P.I.O.T.R. Pesticide residues in apples (2005–2010) Arch. Environ. Protect. 2011;37(3):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lozowicka B., Mojsak P., Jankowska M., Kaczynski P., Hrynko I., Rutkowska E., et al. Toxicological studies for adults and children of insecticide residues with common mode of action (MoA) in pome, stone, berries and other small fruit. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;566:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Loughlin T.M., Peluso M.L., Etchegoyen M.A., Alonso L.L., de Castro M.C., Percudani M.C., Marino D.J. Pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables of the Argentine domestic market: occurrence and quality. Food Control. 2018;93:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Matyaszek A., Szpyrka E., Podbielska M., Slowik-Borowiec M., Kurdziel A. Pesticide residues in berries harvested from South-Eastern Poland (2009-2011) Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2013;64(1):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebdoua S., Lazali M., Ounane S.M., Tellah S., Nabi F., Ounane G. Evaluation of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from Algeria. Food Addit. Contam. B. 2017;10(2):91–98. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2016.1278047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojsak P., Łozowicka B., Kaczyński P. Estimating acute and chronic exposure of children and adults to chlorpyrifos in fruit and vegetables based on the new, lower toxicology data. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;159:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwirthová N., Trojan M., Svobodová M., Vašíčková J., Šimek Z., Hofman J., Bielská L. Pesticide residues remaining in soils from previous growing season (s). - can they accumulate in non-target organisms and contaminate the food web? Sci. Total Environ. 2019;646:1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaili T.M., Al Sallagi M.S., Dhanasekaran D.K., Odeh W.A.B., Al Ali H.J., Al Ali A.A., et al. Pesticide residues in fresh vegetables imported into the United Arab Emirates. Food Control. 2022;133 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G. Bochum: Pestizide und Gesundheitsgefahren: Daten und Fakten. 2012. Pesticides and health hazards facts and figures. [Google Scholar]

- Pico Y., El-Sheikh M.A., Alfarhan A.H., Barcelo D. Target vs non-target analysis to determine pesticide residues in fruits from Saudi Arabia and influence in potential risk associated with exposure. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;111:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealey L.A., Hughes B.W., Sriskanda A.N., Guest J.R., Gibson A.D., Johnson-Williams L., et al. Environmental factors in the development of autism spectrum disorders. Environ. Int. 2016;88:288–298. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah R. In: Emerging Contaminants. Emerging Contaminants. Nuro A., editor. IntechOpen Book Series Pages 638 - 355; London, UK: 2020. Pesticides and human health. [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Gupta V.K., Kumar A., Sharma B. Synergistic effects of heavy metals and pesticides in living systems. Front. Chem. 2017;5:70. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Jacobo A., Alcantar-Rosales V.M., Alonso-Segura D., Heras-Ramírez M., Elizarragaz-De La Rosa D., Lugo-Melchor O., Gaspar-Ramirez O. Pesticide residues in orange fruit from citrus orchards in Nuevo Leon State, Mexico. Food Addit. Contam. B. 2017;10(3):192–199. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2017.1315743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed J.H., Alamdar A., Mohammad A., Ahad K., Shabir Z., Ahmed H., et al. Pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from Pakistan: a review of the occurrence and associated human health risks. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2014;21(23):13367–13393. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S., Legind C.N. Dealing with Contaminated Sites. Springer; Dordrecht: 2011. Uptake of organic contaminants from soil into vegetables and fruits; pp. 369–408. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; New York: 2018. Understanding the Impact of Pesticides on Children. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Pesticide residues in food. 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/pesticide-residues-in-food Available from.

- WHO . 2019 edition. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Recommended Classification of Pesticides by hazard and Guidelines to Classification. [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Wu X., Brown K.A., Le T., Stice S.L., Bartlett M.G. Determination of chlorpyrifos and its metabolites in cells and culture media by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2017;1063:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J., Wang Z., Guo L., Xu X., Liu L., Xu L., et al. Advances in immunoassays for organophosphorus and pyrethroid pesticides. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Zhu H., Yan B., Xu Y., Bañuelos G., Shutes B., et al. Removal of chlorpyrifos and its hydrolytic metabolite 3, 5, 6-trichloro-2-pyridinol in constructed wetland mesocosms under soda saline-alkaline conditions: effectiveness and influencing factors. J. Hazard Mater. 2019;373:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.