Abstract

Background:

Although severe irritability is a predictor of future depression according to recent meta-analytic evidence, other mechanisms for this developmental transition remain unclear. In this study, we test whether deficits in emotion recognition may partially explain this specific association in youth with severe irritability, defined as disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD).

Methods:

Participants aged 8–20 years (M = 13.3, SD = 2.8) included youth with DMDD, split by low depressive (DMDD/LD; n = 52) and high depressive (DMDD/HD; n = 25) symptoms, and healthy controls (HC; n = 39). A standardized computer task assessed emotion recognition of faces and voices of adults and children expressing happiness, fear, sadness, and anger. A Group (3) × Emotion (4) × Actor (2) × Modality (2) repeated measures analysis of covariance examined the number of errors and misidentification of emotions. Linear regression was then used to assess whether deficits in emotion recognition were predictive of depressive symptoms at a 1 year follow-up.

Results:

DMDD/HD youth were more likely to interpret happy stimuli as angry and fearful compared to DMDD/LD (happy as angry: p = 0.018; happy as fearful: p = 0.008) and HC (happy as angry: p = 0.014; happy as fearful: p = 0.024). In youth with DMDD, the misidentification of happy stimuli as fearful was associated with higher depressive symptoms at follow-up (β = 0.43, p = 0.017), independent of baseline depressive and irritability symptoms.

Conclusions:

Deficits in emotion recognition are associated, cross-sectionally and longitudinally, with depressive symptoms in youth with severe irritability. Future studies should examine the neural correlates that contribute to these associations.

Keywords: depression, emotion, facial recognition, irritable mood, voice recognition

1. | INTRODUCTION

Irritable children have a substantially increased risk for future depression (Brotman et al., 2006; Stringaris, Cohen, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2009). A recent meta-analysis found an odds ratio of 1.80 for the longitudinal association between irritability and depression (Vidal-Ribas, Brotman, Valdivieso, Leibenluft, & Stringaris, 2016). Although family (Krieger et al., 2013; Propper et al., 2017) and twin studies (Savage et al., 2015; Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan, & Eley, 2012b) suggest a genetic origin for the overlap between both phenotypes, other potential mechanisms involved in this developmental transition remain unclear. Prior research has implicated aberrant emotional processing—including deficits in emotion recognition, as well as attentional and interpretation biases—as a risk factor for mood disorders, making this a plausible mechanism (Bourke, Douglas, & Porter, 2010; Brotman, Kircanski, Stringaris, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2017). In the current study, we used a carefully characterized clinical sample of youth with severe irritability, defined as DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), to test whether deficits in emotion recognition in faces and voices may partially increase the risk for depression.

Emotion recognition, defined as the ability to identify emotions expressed by facial and vocal stimuli, plays a crucial role in the development of social competence and interpersonal well-being. Deficits in emotion recognition have been reported in youth with severe irritability for faces (Guyer et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2008) and voices (Deveney, Brotman, Decker, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2012). Similarly, and consistent with previous reports (Demenescu, Kortekaas, den Boer, & Aleman, 2010; Kohler, Hoffman, Eastman, Healey, & Moberg, 2011), a recent meta-analysis found deficits in recognition of facial emotions in depressed patients compared to healthy controls (HC; Dalili, Penton-Voak, Harmer, & Munafo, 2015). Of note, these deficits cut across all basic emotions except sadness, that is, depressed patients correctly identified sad faces. Emotion recognition deficits in depression have also been reported for emotional voices (Kan, Mimura, Kamijima, & Kawamura, 2004). For example, depressed participants rated voices with negative emotional prosody (i.e., sad, anger, and fear) as more intense than HC (Naranjo et al., 2011), and were more likely to label happy emotional prosody as more fearful or sad (Peron et al., 2011). Although youth with irritability and youth with depression independently display deficits in emotion recognition, no studies have tested whether these deficits increase the risk for depression in youth with severe irritability.

In addition to deficits in emotion recognition, both irritability and depression are also associated with other emotion processing deficits, namely interpretation and attentional biases. Youth with severe irritability show attentional bias toward threatening faces (Hommer et al., 2014) and perceive neutral and ambiguous faces as more threatening (Brotman et al., 2010; Stoddard et al., 2016). Similarly, depressed patients’ attention is also drawn toward negative faces, especially sad faces, (Armstrong & Olatunji, 2012; Gotlib, Krasnoperova, Yue, & Joormann, 2004; Leppanen, 2006; Peckham, McHugh, & Otto, 2010), and they are more likely to interpret neutral and ambiguous faces as sadder or less happy (Leppanen, 2006).

Both irritability and depression show high comorbidity with anxiety disorders (Althoff et al., 2016; Axelson & Birmaher, 2001; Copeland, Angold, Costello, & Egger, 2013), which are also associated with deficits in emotional processing in children and adolescents (Armstrong & Olatunji, 2012; Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van, 2007). However, emotional processing deficits in youth with irritability might be independent of co-occurring anxiety symptoms. Specifically, a recent study found that the association between irritability and threat bias was independent of anxiety symptoms, as well as symptoms of attention hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and oppositionality. However, this association was not independent from broad internalizing symptoms—defined as withdrawing symptoms, somatic complaints, and anxious/depressed symptoms (Salum et al., 2017).

Emotion recognition improves from childhood through adolescence and adulthood (Brosgole & Weisman, 1995; Chronaki, Hadwin, Garner, Maurage, & Sonuga-Barke, 2015). At the same time, most cases of depression have the onset during adolescence (Kessler et al., 2007). It is then possible that the underdevelopment of emotional processing skills during adolescence is associated with an increased risk for depression. Indeed, several studies conducted in people at risk for depression suggest that impaired emotional processing might be an endophenotype of depression (Chan, Norbury, Goodwin, & Harmer, 2009; Joormann, Talbot, & Gotlib, 2007; Mannie, Taylor, Harmer, Cowen, & Norbury, 2011; Monk et al., 2008). Moreover, these deficits are predictive of depression and depressive symptoms in longitudinal studies (Beevers & Carver, 2003; Vrijen, Hartman, & Oldehinkel, 2016). Since irritability is a strong predictor of depression, it is plausible to think that a deficit in emotion recognition in children with severe irritability contributes to increase the risk for depression. Identifying such deficits as early contributors to depression may galvanize novel targeted treatment interventions aimed at preventing the development of depression in at-risk children, such as youth with severe irritability.

In the study, we test the association between depressive symptoms and deficits in emotion recognition in a clinical sample of youth with severe irritability using a well-validated paradigm of facial and vocal emotion recognition. Specifically, we predict that: (a) youth with DMDD and high depressive symptoms will be more likely to interpret positive stimuli (i.e., happy faces and voices) as more negative (i.e., sad, fearful, and angry) than those with DMDD and low depressive symptoms, and HC; and (b) misinterpretation of positive stimuli as negative increases the risk of future depression in youth with DMDD over and above any baseline depressive symptoms. Moreover, we also examine the effects of comorbid anxiety disorders and age on emotion recognition in patients with DMDD and depressive symptoms.

2. | MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. | Participants

Participants and parents gave written informed assent and consent for the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Institutional Review Board-approved study. Participants were 8–20 years old (M = 13.3, SD = 2.8) and included youth with DMDD (n = 77) and HC youths (n = 39).

Participants were assessed by master’s- or doctoral-level clinicians using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS–PL; Kaufman et al., 1997), with a supplemental module to ascertain DMDD. Depressive symptoms in patients with DMDD were assessed by self-report with the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992), whereas irritability was measured in DMDD and HC groups using the Affective Reactivity Index (ARI; Stringaris et al., 2012a). General functioning was measured with the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., 1983).

To explore the effect of depressive symptoms, we divided the group of youth with DMDD into low depressive (DMDD/LD; n = 52) and high depressive (DMDD/HD; n = 25) symptoms based on the cutoff for clinical samples (i.e., 13 points) suggested in the CDI manual (Kovacs, 1992).

A third of the DMDD participants (n = 25, 33%; DMDD/LD n = 19; DMDD/HD n = 6) had measures of depressive symptoms at follow-up (time between assessments, M = 1.04 years, SD = 0.5, range = 0.3–2 years). However, attrition analyses showed no difference in age, sex, race, ethnicity, ARI score, CDI score, or task performance between those participants who had data at follow-up and those participants who had no data.

Control subjects were psychiatrically healthy, based on the K-SADS–PL, and had no first-degree relatives with mood disorders. Exclusion criteria for all groups included IQ <70, as measured with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999), pervasive developmental disorder, unstable medical illness, or substance abuse within the past 2 months.

2.2. | Emotion recognition task

The Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy (DANVA–2; Baum & Nowicki, 1998; Rothman & Nowicki, 2004) was used to compare recognition of emotional displays between all three groups (i.e., DMDD/HD, DMDD/LD, and HC). In the current study, we used both the facial expressions subtest and the paralanguage subtest.

The facial expressions subtest includes standardized photographs of children (n = 24) and adults (n = 24) displaying an expression of happiness, sadness, anger, or fear. After viewing the photograph for 2 s, participants indicated by button-press which emotion was expressed. Of note, people shown in the photographs were majority white Caucasian (children 92%, adults 79%). However, participants’ ethnicity was not associated with emotion recognition.

Similarly, the paralanguage subtest features a standardized set of recordings of voices of children (n = 24) and adult (n = 24) actors repeating a neutral phrase (e.g., I’m going out of the room now, but I’ll be back later) in happy, sad, angry, or fearful tones. Using a button press, participants indicated which emotion the actor expressed.

Primary outcome variables included the number of errors in emotion identification in child and adult faces and voices, as well as the type of misidentifications (e.g., rating a happy face as angry or sad).

2.3. | Statistical analysis

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to assess group differences in age, IQ, and general functioning, whereas chi-square tests were used to assess group differences in sex distribution, ethnicity, and rates of comorbid diagnoses. Because age and sex distribution differed between groups, these were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Using a categorical approach, a Group (DMDD/HD, DMDD/LD, and HC) × Emotion (happy, sad, angry, and fearful) × Actor (child and adult) × Modality (face and voice) repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction examined the number of errors per emotion category, and subsequent misidentification of emotions. Bonferroni-corrected post hoc analyses were used to examine pairwise comparisons.

In post hoc analyses in the patient group, we aimed to replicate the above categorical analysis using depressive symptoms as a dimensional measure. To this end, we performed a CDI × Emotion (happy, sad, angry, and fearful) × Actor (child and adult) × Modality (face and voice) repeated measures ANCOVA. Partial η2 is reported for effect size (small = 0.01, medium = 0.06, and large = 0.14) (Cohen, 1988).

To examine the effects of anxiety disorders, we replicated the categorical analyses in the DMDD participants using a repeated measures ANCOVA with a four-level group (DMDD/LD vs. DMDD/LD with anxiety disorder (ANX) vs. DMDD/HD vs. DMDD/HD+ANX).

Additionally, given the wide range of ages in the current sample, we examined the effects of age on emotion recognition by (a) performing pairwise correlations between age and number of errors in emotion recognition, and (b) rerunning the categorical analyses in the DMDD participants using a repeated measures ANCOVA with a four-level group (DMDD/LD children vs. DMDD/LD adolescents vs. DMDD/HD children vs. DMDD/HD adolescents). For the purposes of this analysis, DMDD children were defined as participants aged 8–11 years, and DMDD adolescents as participants aged 12–20 years.

Finally, given the high levels of attrition, we performed an exploratory dimensional analysis by testing whether emotion recognition accuracy predicted depressive symptoms at follow-up in a subset of DMDD participants. To this end, we used linear regression analyses with depressive symptoms at follow-up as outcome, and emotion labeling accuracy as the predictor of interest, adjusting for age, sex, number of days between assessments, and baseline depressive symptoms.

3. | RESULTS

3.1. | Sample characteristics

Groups differed in age (F[2, 113] = 12.81, p < 0.0001) and sex distribution (χ2[2, 114] = 5.6, p = 0.060). Specifically, mean age of healthy volunteers was higher than in both DMDD groups, and the DMDD/LD group had fewer females when compared with the other two groups. There were no differences in ethnicity, rates of comorbid diagnoses, prescribed medication, IQ, or general functioning (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| HC (n = 39) |

DMDD/LD (n = 52) |

DMDD/HD (n = 25) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Females | 15 | 38 | 13 | 25 | 13 | 52 |

| Ethnicitya | ||||||

| Caucasian | 24 | 65 | 39 | 75 | 15 | 60 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 12 |

| African American | 7 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| Asian | 2 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 4 |

| Multiple races | 2 | 5 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 12 |

| Medication | – | – | 38 | 76 | 17 | 68 |

| Comorbid diagnoses | ||||||

| ADHD | – | – | 36 | 69 | 20 | 80 |

| ODD | – | – | 30 | 58 | 12 | 48 |

| CD | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GAD | – | – | 16 | 31 | 9 | 36 |

| SAD | – | – | 14 | 27 | 7 | 28 |

| SOC | – | – | 7 | 14 | 3 | 12 |

| Any mood | – | – | 6 | 12 | 6 | 24 |

| Any externalizing | – | – | 40 | 77 | 21 | 84 |

| Any anxiety | – | – | 28 | 54 | 13 | 52 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 14.9 | 2.7 | 12.7 | 2.5 | 11.9 | 2.3 |

| IQb | 112.9 | 11.3 | 112.7 | 13.9 | 108.3 | 13.1 |

| CGASc | – | – | 47.4 | 10.2 | 45.6 | 8.1 |

| ARId | 1.3 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 6.2 | 2.9 |

| CDI | – | – | 5.9 | 3.3 | 20.2 | 6.3 |

Notes. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; Any anxiety, includes GAD, SAD, and SOC; Any mood, includes major depression disorder, dysthymia, and mood disorder not otherwise specified; CD, conduct disorder; CDI, Children’s Depression Inventory; DMDD, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; HC, healthy controls; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; SAD, separation anxiety disorder; SOC, social anxiety disorder.

Ethnicity information was missing for n = 2 HC.

Intelligence quotient (IQ) information was available for n = 18 HC, n = 31 DMDD/LD, and n = 17 DMDD/HD.

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) information was available for n = 34 DMDD/LD and n = 19 DMDD/HD.

Affective Reactivity Index (ARI) information was available for n = 29 HC, n = 46 DMDD/LD, and n = 24 DMDD/HD.

3.2. | Categorical analysis

A significant main effect indicated that groups differed in emotion recognition errors overall (F(2,111) = 5.19, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.09). Bonferroni-corrected post hoc analyses revealed that DMDD/HD youth made more errors than DMDD/LD (p = 0.010) and HC (p = 0.017).

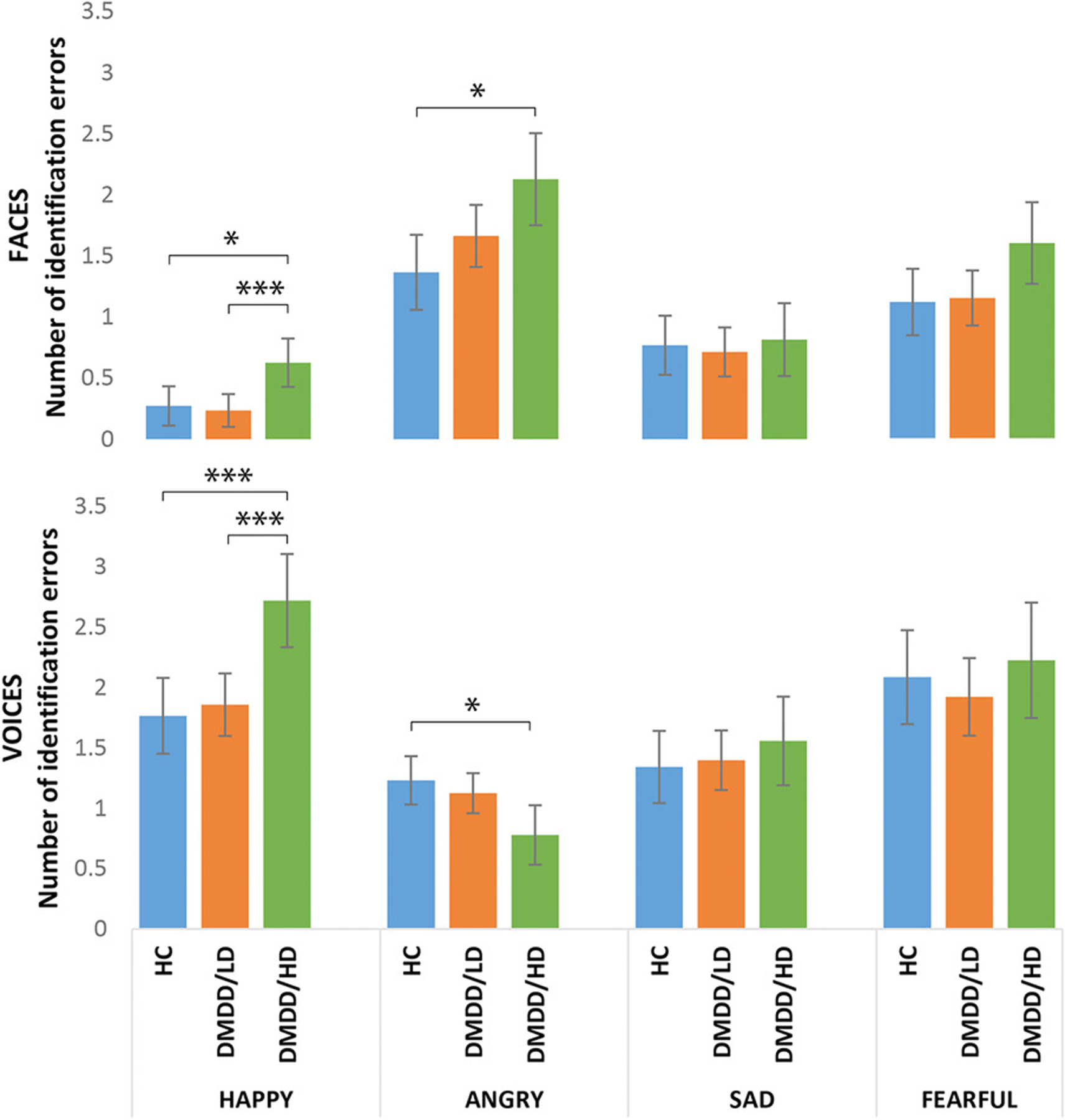

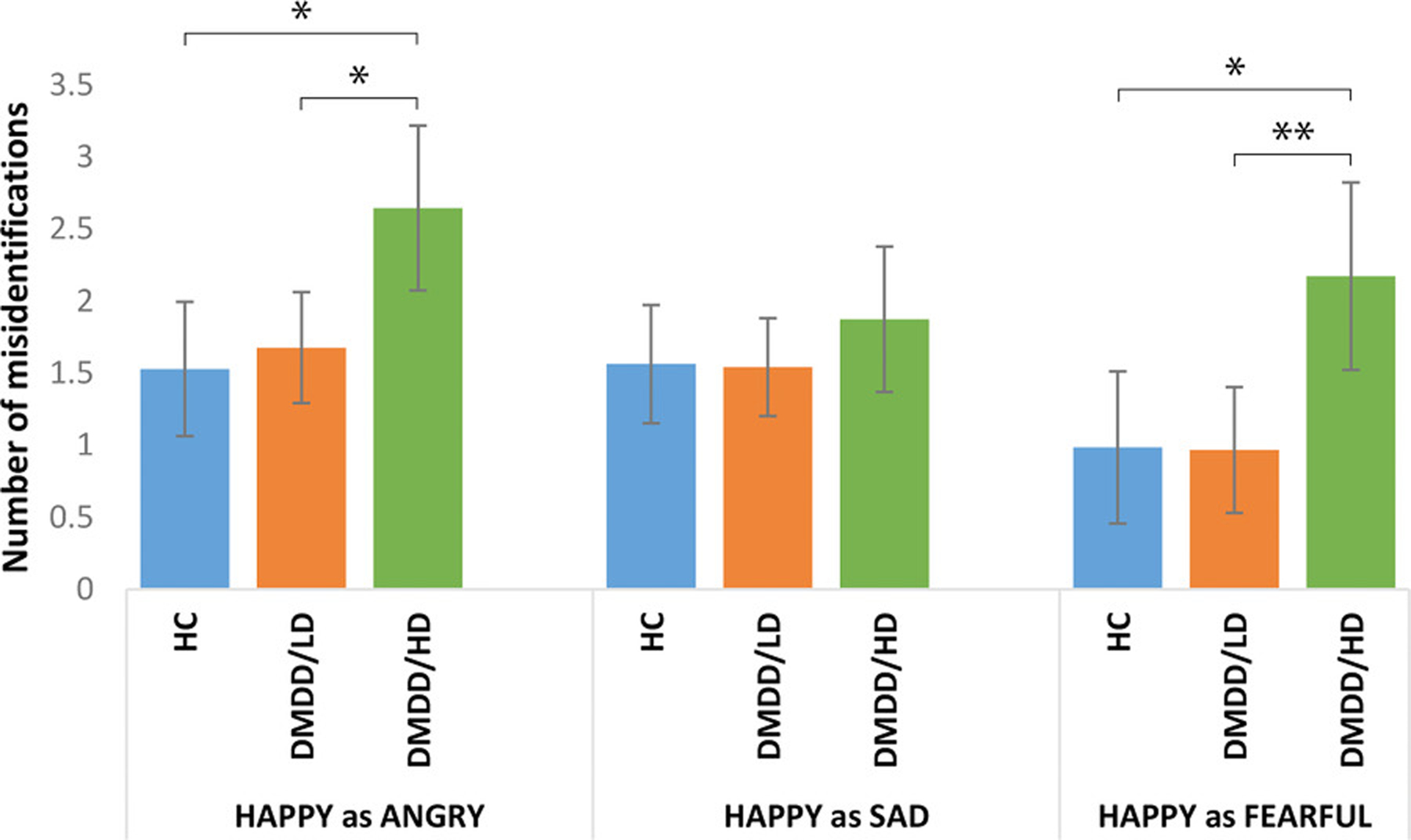

Although there were no significant four-way interactions, a significant three-way interaction emerged involving Group, Emotion, and Modality (F(6,331.7) = 3.95, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.07). Post hoc analyses revealed that DMDD/HD youth made more errors identifying happy faces and voices than DMDD/LD (happy faces: p = 0.004; happy voices: p = 0.001), and HC (happy faces: p = 0.028; happy voices: p = 0.001) with no differences between the latter (Figure 1). Specifically, DMDD/HD youth were more likely to interpret happy stimuli as angry and fearful compared to DMDD/LD (happy as angry: p = 0.018; happy as fearful: p = 0.008) and HC (happy as angry: p = 0.014; happy as fearful: p = 0.024). There were no differences in the misidentification of happy stimuli as sad between groups (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Number of identification errors by emotion and modality across groups. Bars are 95% confidence intervals. Means adjusted for age and sex, and Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005

FIGURE 2.

Misidentification of happy stimuli as other emotions across groups. Bars are 95% confidence intervals. Means adjusted for age and sex, and Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005

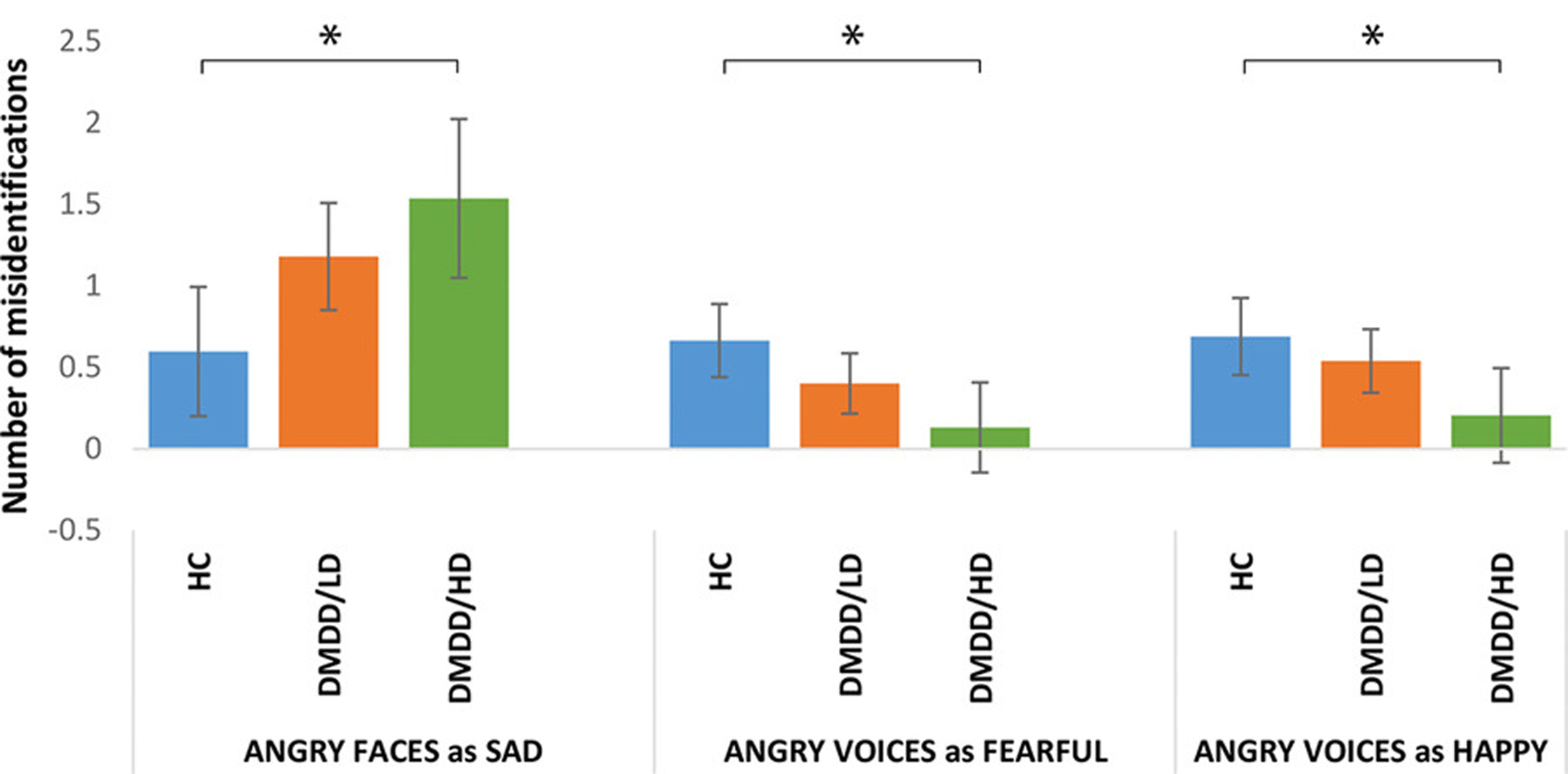

Additionally, whereas DMDD/HD youth made more errors in the recognition of angry faces than HC (p = 0.010), particularly those from child actors (p = 0.028), the opposite was true for voices; that is, DMDD/HD were better at recognizing angry voices than HC (p = 0.023; Figure 1), particularly those from adult actors (p = 0.036). Post hoc analyses showed that DMDD/HD youth misidentified angry faces as sad more frequently than HC (p = 0.016). On the other hand, HC youth misidentified angry voices as fearful (p = 0.015) and happy (p = 0.045) more frequently than DMDD/HD youth (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Misidentification of angry stimuli as other emotions across groups. Bars are 95% confidence intervals. Means adjusted for age and sex, and Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005

Within the DMDD participants, there were no differences between unmedicated and medicated individuals in task performance (all p > 0.30). Furthermore, adding medication status as a covariate did not alter the results. Finally, we reran the analyses after removing the six participants with any mood disorder from the DMDD/LD groups; results remained unchanged (available upon request).

3.3. | Dimensional analysis

An analysis with the CDI, a dimensional measure of depressive symptoms, yielded similar results to the main categorical analyses in youth with DMDD. There was a main effect of CDI (F(1,73) = 7.73, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.10) suggesting that depressive symptoms were associated with more errors overall in the DMDD group. Although there were no significant four-way interactions, a significant three-way interaction emerged involving CDI, emotion, and modality (F(2.9,215) = 3.68, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.05). Linear regression analyses showed that in youth with DMDD, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with the number of identification errors in happy faces (β = 0.31, p = 0.011), happy voices (β = 0.41, p < 0.001), and angry faces (β = 0.26, p = 0.039). Although irritability was significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.51, p < 0.001), these results were also true in models adjusted for irritability symptoms (happy faces: β = 0.32, p = 0.029; happy voices: β = 0.35, p = 0.014; angry faces: β = 0.30, p = 0.045). Of note, irritability itself did not predict accuracy in these analyses. Furthermore, in models adjusted for clinical impairment (happy faces: β = 0.30, p = 0.045; happy voices: β = 0.39, p = 0.007; angry faces: β = 0.37, p = 0.013), impairment was not associated with accuracy.

Consistent with the categorical analyses, in youth with DMDD, depressive symptoms were associated with the misidentification of happy stimuli as fearful (β = 0.38, p = 0.001) and angry (β = 0.25, p = 0.041), but not sad stimuli (β = 0.12, p = 0.336). However, after controlling for co-occurring irritability symptoms, only the association with misidentification of happy stimuli as fearful remained significant (β = 0.38, p = 0.006). Lastly, neither depressive nor irritability symptoms were associated with medication status (all p > 0.35), and adding medication as a covariate did not alter results of the dimensional analysis.

3.4. | Effects of comorbid anxiety disorders on emotion recognition

There were no differences in rates of anxiety disorders between DMDD/LD and DMDD/HD (χ2(2) = 0.02, p = 0.879; Table 1); also, there were no differences in CDI scores between those DMDD youth with and without anxiety disorders, t(75) = 0.025, p = 0.980. Moreover, having an anxiety disorder by itself was not associated with errors in the recognition of emotional stimuli in any modality (all p > 0.20). However, a repeated measures ANOVA with a four-level group (DMDD/LD [n = 24], DMDD/LD+ANX [n = 28], DMDD/HD [n = 12], and DMDD/HD+ANX [n = 13]) revealed a two-way interaction involving group and emotion (F(8,190.4) = 3.49, p = 0.040, η2 = 0.08). After controlling for multiple comparisons, post hoc analyses showed that youths in the DMDD/HD+ANX group made more errors in recognizing happy stimuli than DMDD/LD (p < 0.001), DMDD/LD+ANX (p < 0.001), and DMDD/HD groups (p = 0.015). Specifically, youth in the DMDD/HD+ANX group were more likely to misidentify happy stimuli as fearful than DMDD/LD (p = 0.005), DMDD/LD+ANX (p < 0.001), and DMDD/HD youth (p = 0.003).

3.5. | Effects of age on emotion recognition

In the whole sample, age was negatively associated with number of errors in emotion recognition, overall (r = −0.36, p = 0.0001) as well as for happy (r = −0.27, p = 0.004), angry (r = −0.21, p = 0.02), fearful (r = −0.24, p = 0.009), and sad stimuli (r = −0.20, p = 0.03).

In a repeated measures ANOVA with a four-level group (DMDD/LD children [n = 19], DMDD/LD adolescents [n = 33], DMDD/HD children [n = 14], DMDD/HD adolescents [n = 11]), a two-way interaction emerged involving group and emotion (F[8,191.3] = 3.37, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.12). After controlling for multiple comparisons, post hoc analyses showed that both children (p = 0.002) and adolescents with DMDD/HD (p = 0.004) made more errors in recognizing happy stimuli than DMDD/LD adolescents. In addition, DMDD/HD children made more errors in recognizing fearful stimuli than DMDD/LD children (p = 0.024) and DMDD/LD adolescents (p = 0.028). Finally, within the DMDD/LD group, children made more errors in recognizing sad stimuli than adolescents (p = 0.025).

3.6. | Longitudinal analysis

We used significant associations at baseline as predictors of interest for future depressive symptoms in a subset of DMDD participants. Given the high level of attrition (66%), these analyses are exploratory and the results should be interpreted with caution. All results mentioned below are adjusted for age, sex, days between assessments, and baseline depressive symptoms.

In youth with DMDD, the misidentification of happy stimuli as fearful was associated with higher depressive symptoms at follow-up (β = 0.41, p = 0.016), even when adjusting for baseline irritability symptoms (β = 0.43, p = 0.017). Misidentification of happy stimuli as angry, or angry faces as sad, was not associated with future depressive symptoms (β = −0.20, p = 0.302; β = −0.12, p = 0.441).

By contrast, misidentifying angry voices as fearful was associated with higher depressive symptoms at follow-up (β = 0.34, p = 0.046), a finding that became a trend after controlling for irritability symptoms at baseline (β = 0.34, p = 0.051).

4. | DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a behavioral deficit (i.e., emotion recognition) as a potential candidate to explain the association between irritability and depression (Vidal-Ribas et al., 2016). Cross-sectionally, depressive symptoms in youth with DMDD were mainly associated with impaired recognition of happy stimuli across modalities (i.e., faces and voices); specifically, DMDD youth with higher levels of depressive symptoms were more likely to misinterpret happy stimuli as fearful and angry, independent of current irritability symptoms. Additionally, we found that deficits in emotion recognition predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms at follow-up approximately one year later, independent of baseline depressive and irritability symptoms. These findings are supported by the strengths of the study, which include a careful clinical characterization of the sample and a standardized behavioral task.

The findings of the current study suggest that deficits in emotion recognition in youth with severe irritability are associated with the presence of depressive symptoms, rather than irritability symptoms. Emotion recognition accuracy in healthy volunteers only differed from DMDD youth with high depressive symptoms. In addition, the association between CDI scores and emotion recognition was significant even after accounting for current irritability symptoms, with the latter not being associated with emotion recognition accuracy. These findings contrast with previous studies in which, compared with healthy volunteers, deficits in emotion recognition were found in youth with severe irritability (Deveney et al., 2012; Guyer et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2008). The discrepancy with previous studies may be explained by different operating definitions of chronic severe irritability, that is, previous works have employed youth with severe mood dysregulation, which encompasses hyperarousal symptoms, and includes sadness along anger as negative mood. Differences could also be attributed to the use of distinct tasks (Kim et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2008), less conservative analyses (Deveney et al., 2012; Guyer et al., 2007), distinct features of examined emotion labeling accuracy (Kim et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2008), or simply because the effects of depressive symptoms on emotion recognition were not tested or could not be tested (Guyer et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2008). Nevertheless, our longitudinal analysis showed that regardless of current depressive symptoms, emotion recognition deficits in youth with DMDD—who mostly had low depressive symptoms at baseline—were predictive of more depressive symptoms at follow-up. This finding should be interpreted with caution, because levels of attrition were high, but it might suggest that emotion recognition deficits act as a risk factor for depression in youth with DMDD, as such deficits do in healthy youth (Vrijen et al., 2016). Regardless, our longitudinal findings need replication in a larger sample.

In addition to behavioral deficits in emotion processing, functional magnetic resonance imaging studies show that both irritability and depression are associated with dysfunctional activity and connectivity of fronto-limbic regions, including amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, during explicit (Almeida et al., 2009; Beesdo et al., 2009; Brotman et al., 2010; Carballedo et al., 2011; Coccaro, McCloskey, Fitzgerald, & Phan, 2007; Gaffrey, Barch, Singer, Shenoy, & Luby, 2013; Hall et al., 2014; Keedwell, Andrew, Williams, Brammer, & Phillips, 2005; Lee et al., 2008; Peluso et al., 2009; Wiggins et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2011) and implicit (Fu et al., 2008; Stoddard et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2013) processing of unmasked facial emotions, and also during processing of masked faces (Suslow et al., 2010; Tseng et al., 2016; Victor, Furey, Fromm, Ohman, & Drevets, 2010). Of note, aberrant fronto-limbic response during explicit (Chai et al., 2015; Mannie et al., 2011; Monk et al., 2008) and implicit processing of emotional faces (Goulden et al., 2012; Monk et al., 2008) has also been found in remitted depressed patients and people at high risk for depression. These findings suggest that aberrant neural responses to emotional stimuli might also be a risk factor for depression in both healthy youth and also in those with severe irritability. Future prospective neuroimaging studies should examine whether neural responses to emotional cues in youth with severe irritability are predictive of depression.

Our finding that patients misperceive happiness as fear or anger is consistent with previous studies showing misinterpretation of neutral or ambiguous stimuli as threat in both youths with severe irritability (Brotman et al., 2010; Stoddard et al., 2016) and people with depression (Leppanen, 2006; Peckham et al., 2010). Of note, the misidentification of happy stimuli by DMDD youth was not associated with anxiety disorders unless there were also high levels of depressive symptoms. Although there is strong evidence for attentional bias toward threat in children with anxiety disorders (Bar-Haim et al., 2007), previous reports suggest that depression in youth might be more related to deficits in emotion recognition than anxiety (Demenescu et al., 2010; McClure, Pope, Hoberman, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2003; Morningstar, Dirks, Rappaport, Pine, & Nelson, 2017). In addition, pathophysiological mechanisms associated with threat bias seem to differ between irritability and anxiety (Kircanski et al., 2018). It remains to be seen whether these differ between irritability and depression.

In keeping with previous literature (Brosgole & Weisman, 1995; Chronaki et al., 2015; Morningstar et al., 2017), we found that emotion recognition increased with age. Regardless of depressive symptoms, younger children were more likely to make errors in emotion recognition. However, both children and adolescents with high depressive symptoms made more errors in the recognition of happy stimuli. This suggests that the misidentification of happy stimuli by DMDD youth is closely related to depressive symptoms irrespective of their age and this deficit might increase the risk of depression at any developmental period.

Our findings have potential implications for the prevention and treatment of depression in youth with severe irritability. Several studies have examined the effects on current depression and depressive symptoms of cognitive bias modification, targeting both interpretation and attentional bias. The current evidence suggests that effects are small or nonsignificant, especially in clinical samples (Cristea, Kok, & Cuijpers, 2015; Cristea, Mogoase, David, & Cuijpers, 2015; Hallion & Ruscio, 2011; LeMoult et al., 2018; Mogoase, David, & Koster, 2014). However, promising results have been found in the prevention of depression in high-risk groups (Browning, Holmes, Charles, Cowen, & Harmer, 2012), and further prevention trials employing this approach are underway (Almeida et al., 2014). In addition, an open trial of interpretation bias training (IBT) in youth with DMDD increased happy, as opposed to angry, judgments of ambiguous faces, and this was associated with a reduction in irritability symptoms (Stoddard et al., 2016). A larger-scale RCT of IBT for DMDD is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02531893). Given our current results, one plausible hypothesis is that this treatment might not only reduce irritability symptoms, but also prevent the development of future depression.

With regards to pharmacological approaches, several studies suggest that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) might normalize deficits in emotional processing (Harmer et al., 2003; Harmer et al., 2009), even before changes in mood occur (Pringle & Harmer, 2015). This effect may be explained by the influence of antidepressants on neural circuits involved in emotional processing, such as the amygdala and prefrontal areas (Fu et al., 2004; Godlewska, Norbury, Selvaraj, Cowen, & Harmer, 2012; Roiser et al., 2012; Victor et al., 2010). Whether this effect would be seen in youth with severe irritability remains to be seen. However, there is indirect evidence that SSRIs can be effective in the treatment of irritability (Coccaro, Lee, & Kavoussi, 2009; Fava & Rosenbaum, 1999) and two NIMH funded RCTs testing SSRI in youth with severe irritability are ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT00794040 and NCT01714310). Future studies should examine whether SSRIs normalize emotional processing deficits in youth with irritability, including aberrant neural responses, and whether this is associated with lower rates of future depression.

We also found some unexpected results. Specifically, compared to HC, youth with DMDD and high depressive symptoms had deficits in recognizing angry faces, especially those of children, but performed better in the recognition of angry voices, specifically adults. It should be noted that all emotions were more difficult to identify in voice modality than facial modality, with the exception of anger; DMDD participants found it easier to identify angry voices than angry faces, with no differences within HC. Youth with DMDD are frequently involved in arguments with their parents and peers, hence frequently exposed to angry stimuli. However, depressive symptoms might lead to social withdrawal, loss of contact with peers, isolation within the home environment (e.g., spending more time alone in their bedrooms), and more conflicts at home. Moreover, attention might be drawn inward—thus relying on voices to identify emotion—and negative thoughts about not being liked by others may emerge. Consequently, the combination of these changes with the frequent exposure to angry voices from parents, along with the decreased exposure to the angry faces from friends, might explain this finding. Nonetheless, these results would need replication in a larger sample.

The findings of this study should also be considered in light of its limitations. First, there was considerable attrition at follow-up; our longitudinal findings should be interpreted with caution and need replication in larger samples. However, it should be noted that attrition analyses showed no differences between those participants with follow-up data and those without. Second, information on depressive symptoms was not collected in healthy participants; having this information would have strengthen the dimensional and follow-up analyses. Moreover, having this information would have allowed us to test interactions between irritability and depressive symptoms and its association with emotion recognition. Third, the output of the analyses examining the effects of anxiety disorders and age on emotion recognition should also be interpreted with caution given the small number of observations in some groups. Finally, although not strictly a limitation, in the current study we used an emotion recognition task. Therefore, our study is not directly comparable to other studies that used paradigms to examine attentional bias (Hommer et al., 2014; Salum et al., 2017) or interpretation bias (Brotman et al., 2010; Guyer et al., 2007; Stoddard et al., 2016), the latter usually tested with neutral or ambiguous stimuli. However, the misidentifications in the current task were with regards to specific emotions, such as fear and anger, and not randomly distributed across all possible emotions; this suggests that errors were emotion specific, like the ones seen in attentional and interpretation bias paradigms (Bourke et al., 2010). Regardless, future studies in irritable youth should examine associations between attentional and interpretation biases, and depressive symptoms.

5. | CONCLUSIONS

In summary, deficits in emotion recognition are associated, cross-sectionally and longitudinally, with depressive symptoms in youth with severe irritability. Future studies should examine the neural correlates that contribute to such associations, and test whether treatments targeting emotion recognition deficits could prevent the development of depression in youth with severe irritability.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NIMH Intramural Research Program (ZIAMH002786–15, ZIAMH002778–17), conducted under NIH Clinical Study Protocol 02-M-0021 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00025935). Pablo Vidal-Ribas received funding support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The authors thank the participants and their families for their invaluable time and contribution to this study.

Funding information

National Institute of Mental Health, Grant/Award Numbers: ZIAMH002778–17, ZIAMH002786–15

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Stringaris, before assuming his duties at NIMH in 2016, had received funding from the Wellcome Trust and the UK National Institute of Health Research, funds from University College London for a joint project with Johnson & Johnson and royalties from Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press. The rest of the authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

REFERENCES

- Almeida JR, Versace A, Mechelli A, Hassel S, Quevedo K, Kupfer DJ, & Phillips ML (2009). Abnormal amygdala-prefrontal effective connectivity to happy faces differentiates bipolar from major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 66(5), 451–459. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida OP, MacLeod C, Ford A, Grafton B, Hirani V, Glance D, & Holmes E (2014). Cognitive bias modification to prevent depression (COPE): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 15, 282. 10.1186/1745-6215-15-282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althoff RR, Crehan ET, He JP, Burstein M, Hudziak JJ, & Merikangas KR (2016). Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder at ages 13–18: Results from the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(2), 107–113. 10.1089/cap.2015.0038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong T, & Olatunji BO (2012). Eye tracking of attention in the affective disorders: A meta-analytic review and synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(8), 704–723. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, & Birmaher B (2001). Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depression and Anxiety, 14(2), 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van IMH (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 1–24. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum KM, & Nowicki S (1998). Perception of emotion: Measuring decoding accuracy of adult prosodic cues varying in intensity. Journal of Non-verbal Behavior, 22(2), 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Lau JY, Guyer AE, McClure-Tone EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, … Leibenluft E (2009). Common and distinct amygdala-function perturbations in depressed vs anxious adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(3), 275–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, & Carver CS (2003). Attentional bias and mood persistence as prospective predictors of dysphoria. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(6), 619–637. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke C, Douglas K, & Porter R (2010). Processing of facial emotion expression in major depression: A review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(8), 681–696. 10.3109/00048674.2010.496359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosgole L, & Weisman J (1995). Mood recognition across the ages. International Journal of Neuroscience, 82(3–4), 169–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Kircanski K, Stringaris A, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2017). Irritability in youths: A translational model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(6), 520–532. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Rich BA, Guyer AE, Lunsford JR, Horsey SE, Reising MM, … Leibenluft E (2010). Amygdala activation during emotion processing of neutral faces in children with severe mood dysregulation versus ADHD or bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 61–69. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Schmajuk M, Rich BA, Dickstein DP, Guyer AE, Costello EJ, … Leibenluft E (2006). Prevalence, clinical correlates, and longitudinal course of severe mood dysregulation in children. Biological Psychiatry, 60(9), 991–997. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning M, Holmes EA, Charles M, Cowen PJ, & Harmer CJ (2012). Using attentional bias modification as a cognitive vaccine against depression. Biological Psychiatry, 72(7), 572–579. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballedo A, Scheuerecker J, Meisenzahl E, Schoepf V, Bokde A, Moller HJ, … Frodl T (2011). Functional connectivity of emotional processing in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 134(1–3), 272–279. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai XJ, Hirshfeld-Becker D, Biederman J, Uchida M, Doehrmann O, Leonard JA, … Kagan E (2015). Functional and structural brain correlates of risk for major depression in children with familial depression. NeuroImage: Clinical, 8, 398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SW, Norbury R, Goodwin GM, & Harmer CJ (2009). Risk for depression and neural responses to fearful facial expressions of emotion. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(2), 139–145. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronaki G, Hadwin JA, Garner M, Maurage P, & Sonuga-Barke EJ (2015). The development of emotion recognition from facial expressions and non-linguistic vocalizations during childhood. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33(2), 218–236. 10.1111/bjdp.12075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Lee RJ, & Kavoussi RJ (2009). A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in patients with intermittent explosive disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(5), 653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, McCloskey MS, Fitzgerald DA, & Phan KL (2007). Amygdala and orbitofrontal reactivity to social threat in individuals with impulsive aggression. Biological Psychiatry, 62(2), 168–178. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, & Egger H (2013). Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(2), 173–179. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristea IA, Kok RN, & Cuijpers P (2015). Efficacy of cognitive bias modification interventions in anxiety and depression: Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(1), 7–16. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.146761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristea IA, Mogoase C, David D, & Cuijpers P (2015). Practitioner review: Cognitive bias modification for mental health problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(7), 723–734. 10.1111/jcpp.12383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalili MN, Penton-Voak IS, Harmer CJ, & Munafo MR (2015). Meta-analysis of emotion recognition deficits in major depressive disorder. Psychological Medicine, 45(6), 1135–1144. 10.1017/s0033291714002591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demenescu LR, Kortekaas R, den Boer JA, & Aleman A (2010). Impaired attribution of emotion to facial expressions in anxiety and major depression. PLoS One, 5(12), e15058. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveney CM, Brotman MA, Decker AM, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2012). Affective prosody labeling in youths with bipolar disorder or severe mood dysregulation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(3), 262–270. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02482.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, & Rosenbaum JF (1999). Anger attacks in patients with depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(15), 21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu CH, Williams SC, Cleare AJ, Brammer MJ, Walsh ND, Kim J, … Bullmore ET (2004). Attenuation of the neural response to sad faces in major depression by antidepressant treatment: A prospective, event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(9), 877–889. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu CH, Williams SC, Cleare AJ, Scott J, Mitterschiffthaler MT, Walsh ND, … Murray RM (2008). Neural responses to sad facial expressions in major depression following cognitive behavioral therapy. Biological Psychiatry, 64(6), 505–512. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffrey MS, Barch DM, Singer J, Shenoy R, & Luby JL (2013). Disrupted amygdala reactivity in depressed 4- to 6-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(7), 737–746. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlewska BR, Norbury R, Selvaraj S, Cowen PJ, & Harmer CJ (2012). Short-term SSRI treatment normalises amygdala hyperactivity in depressed patients. Psychological Medicine, 42(12), 2609–2617. 10.1017/s0033291712000591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, & Joormann J (2004). Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 121–135. 10.1037/0021-843x.113.1.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulden N, McKie S, Thomas EJ, Downey D, Juhasz G, Williams SR, … Elliott R (2012). Reversed frontotemporal connectivity during emotional face processing in remitted depression. Biological Psychiatry, 72(7), 604–611. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, McClure EB, Adler AD, Brotman MA, Rich BA, Kimes AS, … Leibenluft E (2007). Specificity of facial expression labeling deficits in childhood psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(9), 863–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LM, Klimes-Dougan B, Hunt RH, Thomas KM, Houri A, Noack E, … Cullen KR (2014). An fMRI study of emotional face processing in adolescent major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 168, 44–50. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallion LS, & Ruscio AM (2011). A meta-analysis of the effect of cognitive bias modification on anxiety and depression. Psychological Bulletin, 137(6), 940–958. 10.1037/a0024355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Bhagwagar Z, Perrett DI, Vollm BA, Cowen PJ, & Goodwin GM (2003). Acute SSRI administration affects the processing of social cues in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(1), 148–152. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, O’Sullivan U, Favaron E, Massey-Chase R, Ayres R, Reinecke A, … Cowen PJ (2009). Effect of acute antidepressant administration on negative affective bias in depressed patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(10), 1178–1184. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommer RE, Meyer A, Stoddard J, Connolly ME, Mogg K, Bradley BP, … Brotman MA (2014). Attention bias to threat faces in severe mood dysregulation. Depression and Anxiety, 31(7), 559–565. 10.1002/da.22145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Talbot L, & Gotlib IH (2007). Biased processing of emotional information in girls at risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 135–143. 10.1037/0021-843x.116.1.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan Y, Mimura M, Kamijima K, & Kawamura M (2004). Recognition of emotion from moving facial and prosodic stimuli in depressed patients. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 75(12), 1667–1671. 10.1136/jnnp.2004.036079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keedwell PA, Andrew C, Williams SC, Brammer MJ, & Phillips ML (2005). The neural correlates of anhedonia in major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 58(11), 843–853. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, & Ustun TB (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(4), 359–364. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Arizpe J, Rosen BH, Razdan V, Haring CT, Jenkins SE, … Leibenluft E (2013). Impaired fixation to eyes during facial emotion labelling in children with bipolar disorder or severe mood dysregulation. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 38(6), 407–416. 10.1503/jpn.120232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircanski K, White LK, Tseng WL, Wiggins JL, Frank HR, Sequeira S, … Brotman MA (2018). A latent variable approach to differentiating neural mechanisms of irritability and anxiety in youth. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(6), 631–639. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Hoffman LJ, Eastman LB, Healey K, & Moberg PJ (2011). Facial emotion perception in depression and bipolar disorder: A quantitative review. Psychiatry Research, 188(3), 303–309. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (1992). The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) manual North Tanawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger FV, Polanczyk VG, Goodman R, Rohde LA, Graeff-Martins AS, Salum G, … Stringaris A (2013). Dimensions of oppositionality in a Brazilian community sample: Testing the DSM-5 proposal and etiological links. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(4), 389–400.e1. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BT, Seok JH, Lee BC, Cho SW, Yoon BJ, Lee KU, … Ham BJ (2008). Neural correlates of affective processing in response to sad and angry facial stimuli in patients with major depressive disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 32(3), 778–785. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMoult J, Colich N, Joormann J, Singh MK, Eggleston C, & Gotlib IH (2018). Interpretation bias training in depressed adolescents: Near- and far-transfer effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(1), 159–167. 10.1007/s10802-017-0285-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen JM (2006). Emotional information processing in mood disorders: A review of behavioral and neuroimaging findings. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(1), 34–39. 10.1097/01.yco.0000191500.46411.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannie ZN, Taylor MJ, Harmer CJ, Cowen PJ, & Norbury R (2011). Frontolimbic responses to emotional faces in young people at familial risk of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(1–2), 127–132. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Pope K, Hoberman AJ, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2003). Facial expression recognition in adolescents with mood and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(6), 1172–1174. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogoase C, David D, & Koster EH (2014). Clinical efficacy of attentional bias modification procedures: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(12), 1133–1157. 10.1002/jclp.22081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Klein RG, Telzer EH, Schroth EA, Mannuzza S, Moulton JL 3rd, … Ernst M (2008). Amygdala and nucleus accumbens activation to emotional facial expressions in children and adolescents at risk for major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(1), 90–98. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morningstar M, Dirks MA, Rappaport BI, Pine DS, & Nelson EE (2017). Associations between anxious and depressive symptoms and the recognition of vocal socioemotional expressions in youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–10. 10.1080/15374416.2017.1350963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Naranjo C, Kornreich C, Campanella S, Noel X, Vandriette Y, Gillain B, … Constant E (2011). Major depression is associated with impaired processing of emotion in music as well as in facial and vocal stimuli. Journal of Affective Disorders, 128(3), 243–251. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham AD, McHugh RK, & Otto MW (2010). A meta-analysis of the magnitude of biased attention in depression. Depression and Anxiety, 27(12), 1135–1142. 10.1002/da.20755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso MA, Glahn DC, Matsuo K, Monkul ES, Najt P, Zamarripa F, … Soares JC (2009). Amygdala hyperactivation in untreated depressed individuals. Psychiatry Research, 173(2), 158–161. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peron J, El Tamer S, Grandjean D, Leray E, Travers D, Drapier D, … Millet B (2011). Major depressive disorder skews the recognition of emotional prosody. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 35, 4, 987–996. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle A, & Harmer CJ (2015). The effects of drugs on human models of emotional processing: An account of antidepressant drug treatment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 477–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propper L, Cumby J, Patterson VC, Drobinin V, Glover JM, MacKenzie LE, … Uher R (2017). Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in offspring of parents with depression and bipolar disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(6), 408–412. 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.198754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich BA, Grimley ME, Schmajuk M, Blair KS, Blair RJ, & Leibenluft E (2008). Face emotion labeling deficits in children with bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. Development and Psychopathology, 20(2), 529–546. 10.1017/s0954579408000266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiser JP, Levy J, Fromm SJ, Goldman D, Hodgkinson CA, Hasler G, … Drevets WC (2012). Serotonin transporter genotype differentially modulates neural responses to emotional words following tryptophan depletion in patients recovered from depression and healthy volunteers. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 26(11), 1434–1442. 10.1177/0269881112442789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AD, & Nowicki S (2004). A measure of the ability to identify emotion in children’s tone of voice. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 28(2), 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Salum GA, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Stringaris A, Gadelha A, Pan PM, … Leibenluft E (2017). Association between irritability and bias in attention orienting to threat in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(5), 595–602. 10.1111/jcpp.12659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, Verhulst B, Copeland W, Althoff RR, Lichtenstein P, & Roberson-Nay R (2015). A genetically informed study of the longitudinal relation between irritability and anxious/depressed symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 377–384. 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, & Aluwahlia S (1983). A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40(11), 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J, Sharif-Askary B, Harkins EA, Frank HR, Brotman MA, Penton-Voak IS, … Leibenluft E (2016). An open pilot study of training hostile interpretation bias to treat disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(1), 49–57. 10.1089/cap.2015.0100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J, Tseng WL, Kim P, Chen G, Yi J, Donahue L, … Leibenluft E (2017). Association of irritability and anxiety with the neural mechanisms of implicit face emotion processing in youths with psychopathology. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(1), 95–103. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2009). Adult outcomes of youth irritability: A 20-year prospective community-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(9), 1048–1054. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R, Ferdinando S, Razdan V, Muhrer E, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2012a). The affective reactivity index: A concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(11), 1109–1117. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02561.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Zavos H, Leibenluft E, Maughan B, & Eley TC (2012b). Adolescent irritability: Phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(1), 47–54. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suslow T, Konrad C, Kugel H, Rumstadt D, Zwitserlood P, Schoning S, … Dannlowski U (2010). Automatic mood-congruent amygdala responses to masked facial expressions in major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 67(2), 155–160. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LA, Kim P, Bones BL, Hinton KE, Milch HS, Reynolds RC, … Leibenluft E (2013). Elevated amygdala responses to emotional faces in youths with chronic irritability or bipolar disorder. NeuroImage: Clinical, 2, 637–645. 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng WL, Thomas LA, Harkins E, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2016). Neural correlates of masked and unmasked face emotion processing in youth with severe mood dysregulation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(1), 78–88. 10.1093/scan/nsv087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor TA, Furey ML, Fromm SJ, Ohman A, & Drevets WC (2010). Relationship between amygdala responses to masked faces and mood state and treatment in major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(11), 1128–1138. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, Valdivieso I, Leibenluft E, & Stringaris A (2016). The status of irritability in psychiatry: A conceptual and quantitative review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(7), 556–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijen C, Hartman CA, & Oldehinkel AJ (2016). Slow identification of facial happiness in early adolescence predicts onset of depression during 8 years of follow-up. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(11), 1255–1266. 10.1007/s00787-016-0846-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1999). Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Brotman MA, Adleman NE, Kim P, Oakes AH, Reynolds RC, … Leibenluft E (2016). Neural correlates of irritability in disruptive mood dysregulation and bipolar disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(7), 722–730. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TT, Simmons AN, Matthews SC, Tapert SF, Frank GK, Max JE, … Paulus MP (2010). Adolescents with major depression demonstrate increased amygdala activation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(1), 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong M, Wang X, Xiao J, Yi J, Zhu X, Liao J, … Yao S (2011). Amygdala hyperactivation and prefrontal hypoactivation in subjects with cognitive vulnerability to depression. Biological Psychology, 88(2–3), 233–242. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]