Abstract

The family of variable surface lipoproteins (Vsps) of the bovine pathogen Mycoplasma bovis includes some of the most immunogenic antigens of this microorganism. Vsps were shown to undergo high-frequency phase and size variations and to possess extensive reiterated coding sequences extending from the N-terminal end to the C-terminal end of the Vsp molecule. In the present study, mapping experiments were conducted to detect regions with immunogenicity and/or adhesion sites in repetitive domains of four Vsp antigens of M. bovis, VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF. In enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay experiments, sera obtained from naturally infected cattle showed antibodies to different repeating peptide units of the Vsps, particularly to units RA1, RA2, RA4.1, RB2.1, RE1, and RF1, all of which were found to contain immunodominant epitopes of three to seven amino acids. Competitive adherence trials revealed that a number of oligopeptides derived from various repeating units of VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF partially inhibited cytoadhesion of M. bovis PG45 to embryonic bovine lung cells. Consequently, putative adherence sites were identified in the same repeating units (RA1, RA2, RA4.1, RB2.1, RE1, and RF1) and in RF2. The positions and lengths of the antigenic determinants were mostly identical to those of adhesion-mediating sites in all short repeating units, whereas in the considerably longer RF1 unit (84 amino acid residues), there was only one case of identity among four immunogenic epitopes and six adherence sites. The identification of epitopes and adhesive structures in repetitive domains of Vsp molecules is consistent with the highly immunogenic nature observed for several members of the Vsp family and suggests a possible function for these Vsp molecules as complex adherence-mediating regions in pathogenesis.

Mycoplasma bovis is the most important etiological agent of bovine mycoplasmosis in Europe and North America. It is responsible for outbreaks of therapy-resistant mastitis, mostly in larger dairy herds, and cases of pneumonia and arthritis in calves, as well as infections of the genital tract (16).

The antigen repertoire of this pathogen includes a family of variable surface lipoproteins (Vsps) which represents a set of immunodominant lipoproteins undergoing high-frequency phase and size variations, a phenomenon resulting in a multitude of phenotypes in a cultured mycoplasma population (1). While phase variation involves noncoordinated switching between on and off expression states of individual Vsps and is accompanied by DNA rearrangements (8), size variation leads to a set of differently sized proteins within a given Vsp as a consequence of spontaneous additions or deletions of repeating units within the vsp structural gene.

The biological function of Vsp antigens in M. bovis is not yet understood. Recent data indicated an escape mechanism based on modulation of the expression of certain variable proteins to evade opsonization of specific antibodies (7), which can be regarded as part of the strategy of the pathogen for subverting the host defense system in response to the presence of cognate antibodies. In a more functional aspect, Vsps as a whole or at least some members of the Vsp family are known to be involved in M. bovis cytoadhesion to host cells (6). Variable membrane proteins of other mycoplasma species, such as Vaa of M. hominis (27) and M. synoviae protein A or B (MSPA or MSPB) (12), were also shown to possess adhesive functions. Although considerably longer than those of M. bovis, repeating elements in the genome of M. genitalium are supposed to optimize cellular adhesion and to evade the host immune response (15).

Meanwhile, the vsp genomic locus of M. bovis has been cloned and characterized, and nucleotide sequences of 13 distinct vsp genes are available (8, 9). Examination of deduced amino acid sequences revealed an unusual structural motif. Most of the Vsp molecules are composed of repeating units extending from the N terminus to the C terminus of the protein chain. The majority of repetitive sequences are arranged as tandem domains consisting of units of 6 to 87 amino acids (aa). Since repeated units comprise the major part of most Vsp molecules, they may harbor active sites with certain biological functions, i.e., antigenic determinants, sites for cytoadhesion, or a different, as-yet-unknown function. Detailed characterization of Vsp functional domains appeared to be an essential prerequisite for understanding the molecular interactions between the pathogen and the host cell surface during pathogenesis.

In the present work, the repetitive domains of four selected Vsp antigens of M. bovis, VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF, were examined for the presence of potential continuous epitopes with respect to immunogenic and/or adhesion sites. Therefore, sera of diseased animals infected with M. bovis were screened by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibodies to repeating units. The ability of defined oligopeptides to reduce cytoadhesion was examined with a competitive adherence assay. To characterize the location of functional domains at the amino acid level, mapping of immunodominant epitopes and adherence sites was conducted with overlapping oligopeptides covalently bound to a membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal sera.

Sera from six dairy cows (cows 1, 4, 7, 14, 22, and 23) with mastitis due to natural infection with M. bovis were investigated. M. bovis in milk samples from all animals was verified by culturing. No other bacterial agent was detected. Serum from an M. bovis-free healthy animal from the same herd was included as a control.

Sera from a calf which was experimentally infected with M. bovis 981/84 by use of an aerosol and which developed clinical signs of pneumonia were collected on days 0, 7, 15, 21, and 28 postinfection (p.i.).

Preliminary checks revealed that the sera from the mastitic cows as well as the serum from the pneumonic calf on day 28 p.i. were reactive in immunoblotting against whole-cell proteins of type strain M. bovis PG45.

Computer analysis of protein structures.

Amino acid sequences of variable surface proteins were deduced from nucleotide sequences of the following genes: vspA (GenBank accession no. L81118), vspB (AF162138), vspE (AF162139), and vspF (AF162140) (8, 9). Hydrophobicity plots, secondary structure analysis, and calculation of total amino acid composition were carried out with the following programs: (i) MacVector version 4.1 (IBI Kodak, New Haven, Conn.) and (ii) Winpep 1.0, developed by Lars Hennig, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, and available from http://www.biologie.uni-freiburg.de/data/schaefer/winpep1.html.

Synthetic oligopeptides.

Oligopeptides were synthesized and purified by reversed-phase (RP) high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) at MWG-Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). Peptides used as capture antigens in ELISAs were linked to an additional terminal cysteine residue to allow covalent coupling to ovalbumin.

Specific antibody ELISA.

Eight different oligopeptides based on the repeating units RA1, RA2, RA3, RA4.1, RA4.2, RE1, and RF2 and a 14-aa peptide of RF1 (positions 50 to 63) were covalently linked to ovalbumin as a carrier protein with the Imject Activated Immunogen Conjugation Kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Microtiter plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) were coated by adding 100 μl of ovalbumin-coupled peptide (containing 0.5 μg of peptide) in carbonate buffer (0.05 M sodium carbonate [pH 9.6]) to each well and incubating the plates for 4 h at 4°C. Between incubation steps, microtiter plates were washed three times with 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (12 mM Na2HPO4, 12 mM NaH2PO4, 0.145 M NaCl [pH 7.0]). One hundred microliters of serum (dilution, 1:40) was added to each well, and the plates were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Subsequently, 100 μl of peroxidase-labeled anti-bovine immunoglobulin G (dilution, 1:1000; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) was added, and incubation was carried out at 37°C for 1 h. Finally, 100 μl of ABTS [2,2-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate-6); Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany] was added, and the color reaction was allowed to proceed for 20 min. Absorbances were read at 405 nm.

Competitive adherence assay.

The procedure used for the competitive adherence assay was described previously (20). Briefly, embryonic bovine lung (EBL) cells were cultivated in 24-well tissue culture plates to form confluent monolayers. To each well, 108 CFU of 3H-labeled M. bovis PG45 was added together with 0.5 μmol of the oligopeptide. To allow adhesive interactions, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min with gentle shaking. After three washing steps and solubilization of attached cells, the adherence rates were measured by liquid scintillation counting. Each oligopeptide was tested in at least three separate trials on different plates. Control trials of strain PG45 without the addition of peptides were run in parallel (in quadruplicate) on each plate, and this adherence was taken as 100%. The relative standard deviation of the method is 13.3%.

MAbs.

Details on the preparation and characteristics of Vsp-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) 1E5, 4D7, and 2A8 are given elsewhere (2). Immunoglobulin fractions were obtained by affinity chromatography (Sepharose-protein A column; Amersham Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany) of culture supernatants from a hollow-fiber fermentation system (Tecnomouse; Integra Biosciences, Fernwald, Germany).

Epitope analysis with synthetic peptides spotted on cellulose membranes (Pepscan method).

For peptide spot synthesis as described by Frank (5), the Auto Spot Robot ASP 222 (ABIMED Analysentechnik, Langenfeld, Germany) was used. Overlapping oligopeptides (5 to 10 aa) derived from amino acid sequences of repeating units in VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF were synthesized with 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl-protected amino acids spotted on cellulose membranes derivatized with a polyethylene glycol spacer (300 spots on a membrane measuring 8 by 12 cm).

Before each trial of epitope analysis, nonspecific active sites were blocked by incubation of the membranes in PBS–0.3% Tween 20 (PBS-T) containing 2% (wt/vol) skim milk powder at room temperature for 30 min. Membranes were incubated with 10 ml of animal serum (1:20) in PBS-T at room temperature for 1 h, and reactive spots were visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL Western Blotting Detection System; Amersham) after 30 min of incubation with peroxidase-labeled anti-bovine immunoglobulin G diluted 1:10,000. Membranes were used again after 30 min of incubation at 50°C in stripping buffer (100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol sulfonic acid [sodium salt], 2% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 62.5 mM Tris [pH 6.7]).

Potential adherence determinants were identified by use of a modified version of the Western blot adherence assay (19). Briefly, membranes loaded with oligopeptides (see above) were incubated with 5 to 10 ml of a host cell suspension, i.e., EBL tissue culture cells metabolically labeled with 35S-methionine (0.74 MBq per 5 ml of culture; Amersham), at 37°C with intensive shaking for 2 h. After three washes in PBS-T, membranes were air dried, and reactive spots were visualized within 1 to 4 days by autoradiography with Hyperfilm-ßmax (Amersham).

RESULTS

Structural features of four Vsps of M. bovis.

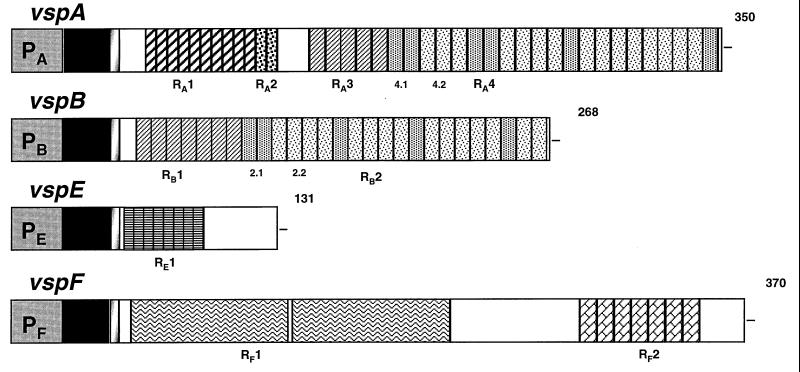

The primary structure of VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF, as deduced from nucleotide sequences of their genes (8, 9), is schematically depicted in Fig. 1. Examination of hydrophobicity profiles revealed that mature VspA, VspB, and VspE are entirely hydrophilic, whereas the VspF molecule harbors both hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions. As the main structural feature, these antigens possess several distinct domains of reiterated sequences which extend from the N-terminal end to the C-terminal end and create a periodic polypeptide chain. In VspA, for instance, where the repetitive portion represents about 80% of the entire protein chain, four distinct internal regions of contiguous tandemly repeating units were identified and designated RA1, RA2, RA3, and RA4. The latter can be further divided into subunits RA4.1 and RA4.2, which differ in three of eight amino acid residues. While VspB has only two distinct repetitive regions, RB1 and RB2, which are highly homologous to RA3 and RA4, respectively, the structures of repeated peptide units in VspE and VspF are markedly different. Thus, in VspE there is only one region of short tandem repeats, RE1, and VspF is unique among these four Vsps for its relatively long repeats, RF1 (84 aa) and RF2 (10 aa). (See Fig. 4 and Table 3 for amino acid sequences of repetitive units for RF1 and all others.) Another structural characteristic is the high content of the amino acid proline, particularly in VspA (10%), VspB (8.2%), and VspE (13.7%). In addition, glycine and glutamine are abundant in VspA and VspB, while glutamic acid and lysine are highly represented in VspE and VspF. A summary of characteristic features of the antigens is given in Table 1. A comparison of both nucleotide and amino acid sequences of Vsps with those contained in GenBank databases failed to identify homologs in other organisms.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of gene sequences coding for four Vsps of M. bovis: VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF. Solid blocks at the N terminus depict promoter (PX) or putative signal peptide (black) sequences. Blocks with different types of hatching or shading and designated RAn, RBn, REn, and RFn represent repeating units. Subunits within the RA4 domain (4.1 and 4.2) or within the RB2 domain (2.1 and 2.2) are indicated. Numbers at the right end of each Vsp represent the length of the polypeptide chain.

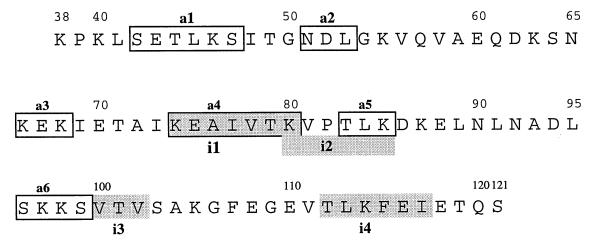

FIG. 4.

Localization of epitopes of immunogenicity and adhesion sites in repeating unit RF1 of VspF, as determined by epitope mapping. Methodology, serum samples, and adherent cells were the same as those described in the legend to Fig. 3. Potential immunogenic epitopes (shaded areas) are designated i1 to i4, and adherence sites (boxed areas) are designated a1 to a6. (Epitopes i3 and i4 are probably nonspecific, as they were also recognized by preimmune control sera.)

TABLE 3.

Effect of oligopeptides derived from repeating units of Vsp antigens on the adherence of M. bovis to EBL cells

| Repeat(s) (sequence) | Oligopeptide(s) showing the following effect on the adherence rate (% change):

|

Adherence epitopeb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reductiona | No reduction | ||

| RA1 (PGENKT) | PGENKT (+6.9 ± 0.1) | TPGEN | |

| PGENK (+31.5 ± 3.2) | |||

| RA2 (PEENKK) | PEENKKPEENKK (−28.2 ± 4.4) | ENKKP (−2.0 ± 0.1) | KPEENK |

| NKKP (−5.0 ± 0.3) | |||

| KPEEN (+8.5 ± 1.3) | |||

| RA3 and RB1 (GTPANPDQ) | GTPANPDQ (+6.0 ± 0.3) | ||

| GTPANP (+9.2 ± 2.5) | |||

| RA4.1 and RB2.1 (GAGTKPGQ) | GAGTKPGQ (−26.2 ± 2.0) | GTK | |

| AGTKP (−20.1 ± 4.1) | |||

| AGTK (−33.2 ± 4.5) | |||

| GTKP (−33.4 ± 3.3) | |||

| RA4.2 and RB2.2 (GAGTNSQQ) | GAGTNSQQ (+6.8 ± 0.7) | ||

| AGTNS (−12.9 ± 1.9) | |||

| RE1 (PETPKG) | TPKGP (−24.4 ± 1.8) | PETPKG (+3.8 ± 0.5) | TPKGP |

| RF1 (see Fig. 4) | GNDLGKVQVAEQDK (−37.3 ± 5.0) | NDL | |

| KVPTLK (−21.0 ± 3.8) | TLK | ||

| KSVTV (−20.8 ± 3.3) | SKKS | ||

| KEKIETA (−0.6 ± 4.6) | KEK | ||

| KEAIVTK (−1.0 ± 4.4) | KEAIVTK | ||

| TLKFEI (+3.1 ± 0.2) | |||

| RF2 (QGTGAPKSPQ) | QGTGAPKSPQ (−25.0 ± 3.3) | GAPKS (−7.7 ± 1.8) | APKS |

Decrease in adherence rate of at least 20% in comparison to the value in the control trial (rate, 100).

The sequence was determined by epitope mapping on a membrane.

TABLE 1.

Characteristic features of selected Vsps of M. bovisa

| Protein | Mature form | Content (molar %) of:

|

Share of repetitive portion (%) | PG-containing repeats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proline | Glycine | Other amino acids >10% | ||||

| VspA | Hydrophilic | 10.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 (Q) | 78 | RA4.1, RA3, RA1 |

| VspB | Hydrophilic | 8.2 | 20.9 | 16.8 (Q) | 81 | RB2.1, RB1 |

| VspE | Hydrophilic | 13.7 | 8.4 | 15.3 (K), 12.2 (E) | 37 | RE1 |

| VspF | Hydrophilic and hydrophobic | 6.8 | 8.1 | 13.5 (K), 10.8 (E) | 62 | RF2 |

Quantitative data are for sequences obtained from clonal variant 6 of strain PG45.

Detection of antibodies to Vsp repeating units in sera of infected animals.

Bovine sera previously found positive for M. bovis by both a polyclonal antibody ELISA and immunoblotting were analyzed together with control sera by means of a specific antibody ELISA designed to capture cognate antibodies. The assay was conducted with microtiter plates coated with eight different ovalbumin-coupled synthetic oligopeptides representing distinct repetitive amino acid sequences of VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF. Among a group of six naturally infected cows with clinical symptoms of mastitis, at least 50% of the animals tested positive (i.e., more than twice the value for the control) for antibodies to repetitive peptide sequences RA1, RA2, RA4.1, RE1, and RF1 (Table 2). The levels of antibodies to peptides RA3, RB1, and RF2 were only slightly increased compared to the levels in the control serum. Because of the high background, the levels of antibodies to peptides RA4.2 and RB2.2 could not be defined.

TABLE 2.

Examination of sera from naturally infected cows with the specific antibody ELISAa

| Animal | Antibody levels to peptide(s):

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA1 | RA2 | RA3 and RB1 | RA4.1 and RB2.1 | RA4.2 and RB2.2 | RE1 | RF1 | RF2 | |

| 1 | 0.557 | 0.310 | 0.400 | 0.256 | 1.681 | 0.390 | 1.435 | 0.671 |

| 4 | 1.826 | 0.576 | 1.108 | 0.545 | 2.755 | 0.750 | 2.005 | 0.818 |

| 7 | 0.411 | 0.521 | 0.374 | 0.265 | 1.780 | 0.685 | 0.833 | 0.868 |

| 14 | 0.453 | 0.436 | 0.309 | 0.369 | 1.492 | 0.764 | 0.833 | 0.778 |

| 22 | 0.544 | 0.343 | 0.339 | 0.223 | 1.074 | 0.313 | 0.941 | 0.641 |

| 23 | 0.477 | 0.618 | 0.431 | 0.387 | 2.750 | 0.869 | 1.739 | 0.921 |

| Control | 0.209 | 0.228 | 0.278 | 0.178 | 2.683 | 0.301 | 0.676 | 0.512 |

Results are expressed in units of optical density. Readings more than twice the value for the control are shown in bold type.

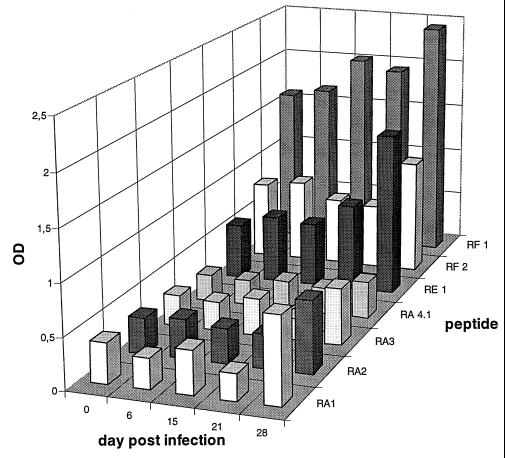

In a second trial, we examined five sera taken at different times from a calf which was experimentally infected with M. bovis and which developed pneumonia. Preliminary data from immunoblotting indicated a measurable host immune response on day 28 p.i. (data not shown), when clinical symptoms were fully apparent. The specific ELISA revealed that there was also a general increase in Vsp antibody titers after 4 weeks (Fig. 2). However, only antibody titers to peptides RA1, RA2, and RE1 were elevated to more than twice the value for the control serum.

FIG. 2.

Examination of sera from a calf experimentally infected with M. bovis by a specific antibody ELISA. Sera were collected on days 0, 6, 15, 21, and 28 p.i. Each serum was examined for antibodies to seven different synthetic oligopeptides representing distinct repetitive amino acid sequences of VspA, VspB, VspE, or VspF. OD, optical density.

Inhibition of M. bovis adhesion by synthetic oligopeptides and MAbs.

The possible involvement of Vsp repetitive domains in cytoadhesion was examined through the ability of Vsp oligopeptides to inhibit M. bovis attachment to mammalian host cells. This was done by a competitive adherence assay with tissue culture plates and several synthetic peptides identical to the complete repeat sequences (Table 3). Subsequently, tetrapeptides and pentapeptides representing partial sequences of repeats were used to refine the search for epitopes. A 20% reduction of M. bovis adherence rates due to blocking of host cell receptor sites under standardized conditions was considered a minimal criterion of inhibitory activity. The results presented in Table 3 show that the cytoadhesion of strain PG45 was partially inhibited by 10 oligopeptides derived from repeats RA2, RA4.1, RE1, RF1, and RF2. On the other hand, 14 other peptides (tetramers to octamers) derived from repeats RA1, RA2, RA3, RB1, RA4.2, RB2.2, RE1, RF1, and RF2 failed to reduce adherence.

To check the accessibility of putative Vsp contact sites on the surface of viable mycoplasma cells, we conducted adherence inhibition trials with three Vsp-specific MAbs, designated 1E5, 4D7, and 2A8. The results summarized in Table 4 show that all three MAbs partially inhibited the cytoadherence of M. bovis PG45 to EBL cells by 34, 41, and 35%, respectively. Target amino acid sequences recognized by these MAbs were determined by epitope mapping experiments (see below).

TABLE 4.

Verification of putative adherence sites with MAbs

| MAb | Recognized site(s) (repeat)a | Reduction of adherence rate (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| 1E5 | AGTK (RA4.1) | 34c |

| AGTN (RA4.2) | ||

| GNDLGKVQVA and SKKSVTV (RF1) | ||

| GTGA (RF2) | ||

| 4D7 | TPGENK (RA1) | 41 |

| KPEENK (RA2) | ||

| 2A8 | GENK (RA1) | 35 |

| NKKP (RA2) | ||

| (G)AGT (RA4.1) | ||

| SETLKS, KVPTL, and KSVTV (RF1) | ||

| 5D8d | 6c |

Amino acid residues belonging to adherence sites identified in this study are shown in bold type.

Standard conditions: 60 μg of affinity-purified MAb and 108 mycoplasma cells.

Data are from reference 21.

MAb 5D8 was included as a control. It was previously shown to recognize a nonvariant intracellular 41-kDa protein of M. bovis (19).

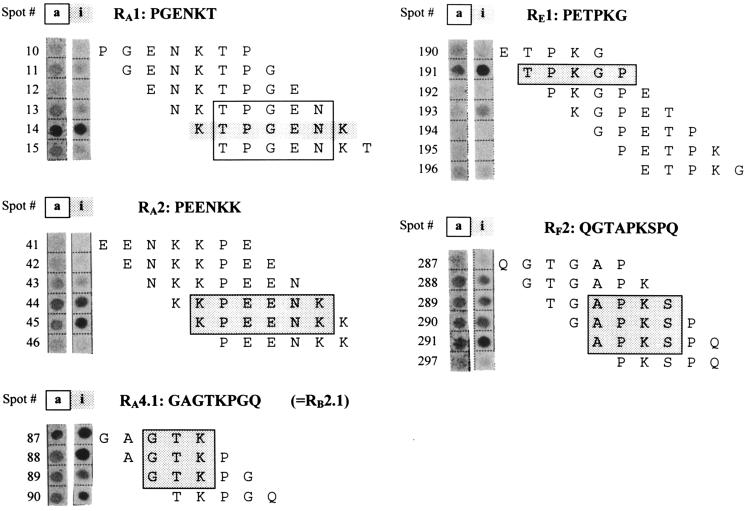

Epitope mapping with membrane-bound overlapping oligopeptides (Pepscan method).

The precise location of antigenic determinants on repetitive domains of Vsp molecules was determined with a set of overlapping oligopeptides (trimers to decamers) spanning distinct Vsp repetitive regions and covalently attached to cellulose membranes. These membranes were incubated with the same set of animal sera as those used in the ELISA. Characteristic reactive patterns led to the identification of putative epitopes present within the periodic structures of Vsps (Fig. 3, lanes i).

FIG. 3.

Identification of immunogenic epitopes and adherence sites in repeating units of VspA, VspB, VspE, and VspF. Cellulose membranes loaded with a series of covalently attached overlapping oligopeptides were incubated with 11 different sera from infected cattle or 35S-labeled EBL cells. Reactivities of peptide spots with serum from an experimentally infected animal (28 days p.i.) and adherent tissue culture cells are shown in lanes i (immunogenicity) and a (adhesion), respectively. The amino acid sequence corresponding to the respective spot is given in the same line. Presumed immunogenic epitopes are indicated by shaded areas, and adherence sites are boxed. Amino acid sequences of complete repeating units, printed in bold type, are given in each panel for comparison.

Altogether, epitope-like targets in repeating units RA1 (KTPGENK), RA2 (KPEENK), RA4.1 (GTK, the same as in RB2.1), RE1 (TPKGP), RF1 (see below), and RF2 (APKS) were recognized by at least half of the sera, and reactive peptide sequences appeared to be identical with all positive sera tested. However, as in the ELISA findings, individual antibody titers tended to vary between animals, and only the epitope sequences of RA1, RA2, RA4.1, RB2.1, and RF1 were recognized by all sera from the mastitic cows and the pneumonic calf on day 28 p.i. Potential contact sites for cytoadhesion were identified by incubation of the peptide-loaded membranes with a suspension of metabolically labeled EBL cells, which served as host cells in this in vitro assay. The results are illustrated in Fig. 3, lanes a. Notably, the putative adherence epitopes of repeating units RA1, RA2, RA4.1, RB2.1, RE1, and RF2 either fully coincided with antigenic determinants or slightly deviated by one or two amino acid residues.

To map reactive sites within the 84-aa-residue repeating unit RF1, a series of 75 overlapping decapeptides covering the entire sequence were covalently attached to the membranes. Incubation with the same series of animal sera and labeled host cells revealed four potential immunogenic and six adherence sites, respectively. The resultant distribution of putative epitopes along the RF1 peptide chain is shown in Fig. 4. However, sites i3 (VTV) and i4 (TLKFEI) are probably nonspecific because of the binding of two preimmune control sera (data not shown).

The adherence-inhibiting MAbs 1E5, 4D7, and 2A8 were also tested for binding to overlapping peptides derived from repeating units. Table 4 shows that the majority of the target sequences recognized by the MAbs included adherence determinants of Vsp molecules presented in Table 3 or some of them; i.e., MAb 1E5 recognized AGTK, GNDLGKVQVA, and SKKSVTV, MAb 4D7 recognized TPGENK and KPEENK, and MAb 2A8 recognized GENK, NKKP, and (G)AGT.

DISCUSSION

The ability of microorganisms to alter the antigenic features of their cell surface was suggested to be part of a strategy of adaptive evolution (11), especially if surface components interacting with a changeable environment are involved. Other potential biological functions of variable lipoproteins include substrate binding and participation in protein secretion and signal transduction (18, 22, 28).

For a number of bacterial pathogens, e.g., group B streptococci (10), staphylococci (6), Haemophilus influenzae (23), and Neisseria spp. (14), contiguous repetitive DNA sequences encoding membrane-bound proteins were described, and the corresponding tandemly repeated peptide units were suggested to be involved in eliciting a host immune response and/or to participate in cell attachment and binding processes (4, 10, 24).

While the data of this study provide the first experimental evidence of the involvement of repetitive domains of Vsps in M. bovis interactions with host cells, they also represent further confirmation of the immunogenic and adhesive functions of Vsps.

Detection by an ELISA of specific antibodies to repeating units RA1, RA2, RA4.1, RB2.1, RE1, and RF1 in the sera of at least 50% of the mastitic cows (Table 2) was further substantiated by the identification of immunogenic epitopes in these repeats by the Pepscan method (Fig. 3). For RF2, for which an active site was also seen on the membrane, ELISA antibody titers appeared to be elevated, but not to the same extent as with the other peptides mentioned. While RA3 and RB1 seemed to be nonimmunogenic, the situation with RA4.2 and RB2.2 remains unclear from the present data. Very high ELISA readings, as shown in Table 2, as well as an occasional background of immunostained spots on the membrane (data not shown) could be a consequence of nonspecific binding caused by polar residues of RA4.2 and RB2.2 (GAGTNSQQ).

The immune response in the experimentally infected pneumonic calf showed a general rise in anti-Vsp titers but appeared to be less intense than that in naturally infected cows (Fig. 2). The M. bovis strain used for infection, 981/84, was previously shown to coexpress in vitro at least two Vsps, VspA and VspB (2).

Considering the locations and sizes of putative adherence epitopes, it is not surprising that the results of epitope mapping could not be verified in all cases in the tissue culture plate adherence assay (Table 3). Obviously, there are essential differences in the spatial arrangement of ligand-receptor reactions between both approaches. The membrane assay involves the specific attachment of tissue culture cells to immobilized but freely accessible peptide chains, so that, in principle, relatively few binding events can generate a positive signal. This characteristic renders the membrane assay more sensitive than the tissue culture plate assay, in which comparatively more recognition events may be necessary to produce measurable adherence inhibition, since a larger number of peptide molecules have to bind to one EBL cell to attain blocking of all receptor sites. Another limitation of the latter includes the difficulties in synthesizing certain tetrapeptides and pentapeptides of sufficient purity.

Important evidence in support of the in vivo function of adherence epitopes identified by the Pepscan method was provided by the demonstration of adherence-inhibiting activity of three MAbs, all of which recognized adherence-related epitopes (Table 4).

Combining adherence data from the present study with previous results from our group, which included (i) selective binding of mammalian host cells to Western-blotted Vsps (21), (ii) enhancement of M. bovis cytoadhesion by purified native Vsps, and (iii) retention of purified Vsp antigens on host cell layers in a cell binding assay (K. Sachse, unpublished results), provides ample evidence demonstrating the involvement of Vsp antigens in cytoadhesion. This conclusion is also supported by reports of proline-rich sequences and proline-rich repeats being involved in a variety of attachment and binding processes (25, 26). Indeed, all epitopes identified in repeats RA1, RA2, RE1, and RF2 contain one proline residue, and the GTK motif in RA4.1 is adjacent to a proline.

Concerning positions of epitopes relative to the repeating units, two different patterns were observed. In the case of RA1, RA2, and RE1, epitope sequences covered 5 to 7 aa of two contiguous repeats, whereas those from RA4.1, RB2.1, RF1, and RF2 (3 to 7 aa) were found to remain within the boundaries of a single unit.

A comparison of positions and lengths of putative antigenic determinants with those of adhesive sites in the short repeating units revealed identity in most cases, with a minor shift only in RA2 (KPEENK versus NKKP; Fig. 3). It is not certain whether this finding really indicates differences in locations between immunogenic and adherence epitopes or whether it is due to inherent limitations of the Pepscan method. Conversely, mapping data from the considerably longer RF1 unit indicate that the locations of immunogenic functional sites differed from those of adherence epitopes in three of four instances. Divergent positions between immunodominant and adherence epitopes were also observed for the P1 protein of M. pneumoniae and the MgPa protein of M. genitalium (13, 17). Interestingly, adherence epitopes were found to be distributed over the entire length of the RF1 repeat, while antigenic determinants appeared to be concentrated in the central part of the C-terminal domain. In addition, the positions of active sites roughly coincided with major or minor peaks in the hydrophobicity plot of this repeating unit (data not shown).

While the present results from epitope mapping will contribute to a better understanding of functional structures of Vsp antigens, it must be emphasized that the methodology used in this study can determine only continuous epitopes. Since the conformation prevailing in the native protein is not retained in linear oligopeptide fragments, it is likely that most of the active sites identified represent only portions of more complex discontinuous epitopes. Consequently, conformational epitopes that are characteristic of the antigens in vivo may either appear as several continuous sites or be left unidentified (3).

Nevertheless, the presence of epitopes in tandemly arranged repetitive peptide units may help to explain the high immunogenicity of several members of the Vsp family, which places VspA, VspB, and VspC among the most prominent antigens of M. bovis (2, 19). In this context, size variation of individual Vsps would result in the generation of more epitopes on the M. bovis surface or a reduction in their numbers, which could be regarded as a way for the pathogen to modulate its immunogenic potential and/or its capability to attach to the host cell surface. The multiplicity of repetitive peptide units may enable the surface protein to bind several ligands, either of the same sort or of a different sort, thus allowing a wide range of avidity and specificity of binding. It is conceivable that favorable or hostile external factors, e.g., from the host immune response or environmental conditions, may cause mycoplasmas to increase or decrease the intensity of their interaction with the host.

Although the findings of the present study on epitope localization should provide important clues for vaccine development, the straightforward approach, i.e., using purified Vsps or synthetic peptides for immunization, may not be effective, as experience with the P1 protein of M. pneumoniae has shown (17). In the case of M. bovis, ways have to be found to deal with its ability to evade the host immune response by modulating the expression of certain Vsps in the presence of cognate antibodies (7). Instead, DNA vaccination with vectors encoding a number of epitopes from distinct variable and nonvariable antigens may be a promising alternative.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development (GIF) grant I-367-147.13/94.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behrens A, Heller M, Kirchhoff H, Yogev D, Rosengarten R. A family of phase- and size-variant membrane surface lipoprotein antigens (Vsps) of Mycoplasma bovis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5075–5084. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5075-5084.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beier T, Hotzel H, Lysnyansky I, Grajetzki C, Heller M, Rabeling B, Yogev D, Sachse K. Intraspecies polymorphism of vsp genes and expression profiles of variable surface protein antigens (Vsps) in field isolates of Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Microbiol. 1998;63:189–203. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(98)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler J E. The behavior of antigens and antibodies immobilized on a solid phase. In: van Regenmortel M H V, editor. Structure of antigens. Vol. 1. London, England: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dramsi S, Dehoux P, Cossart P. Common features of Gram-positive bacterial proteins involved in cell recognition. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1119–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank R. Spot synthesis: an easy technique for the positionally addressable, parallel chemical synthesis on a membrane support. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:9217–9232. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenay H M E, Bunschoten A E, Schouls L M, van Leeuwen W J, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M J E, Verhoef J, Mooi F R. Molecular typing of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of protein A gene polymorphisms. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:60–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01586186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeGrand D, Solsona M, Rosengarten R, Poumarat F. Adaptive surface antigen variation in Mycoplasma bovis to the host immune response. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lysnyansky I, Rosengarten R, Yogev D. Phenotypic switching of variable surface lipoproteins in Mycoplasma bovis involves high-frequency chromosomal rearrangements. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5395–5401. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5395-5401.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lysnyansky I, Sachse K, Rosenbusch R, Levisohn S, Yogev D. The vsp locus of Mycoplasma bovis: gene organization and structural features. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5734–5741. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5734-5741.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madoff L C, Michel J L, Gong E W, Kling D E, Kasper D L. Group B streptococci escape host immunity by deletion of tandem repeat elements of the alpha C protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4131–4136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moxon E R, Rainey P B, Nowak M A, Lenski R E. Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Curr Biol. 1995;4:24–33. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noormohammadi A H, Markham P F, Whithear K G, Walker I D, Gurevich V A, Ley D H, Browning G F. Mycoplasma synoviae has two distinct phase-variable major membrane antigens, one of which is a putative hemagglutinin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2542–2547. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2542-2547.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opitz O, Jacobs E. Adherence epitopes of Mycoplasma genitalium adhesion. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1785–1790. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-9-1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peak I R A, Jennings M P, Hood D W, Bisercic M, Moxon E R. Tetrameric repeat units associated with virulence factor phase variation in Haemophilus also occur in Neisseria spp. and Moraxella catarrhalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:109–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson S N, Bailey C C, Jensen J S, Borre M B, King E S, Bott K F, Hutchinson C A., III Characterization of repetitive DNA in the Mycoplasma genitalium genome: possible role in the generation of antigenic variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11829–11833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfützner H, Sachse K. Mycoplasma bovis as an agent of mastitis, pneumonia, arthritis and genital disorders in cattle. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epiz. 1996;15:1477–1494. doi: 10.20506/rst.15.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Razin S, Jacobs E. Mycoplasma adhesion. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:407–422. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Razin S, Yogev D, Naot Y. Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1094–1156. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1094-1156.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosengarten R, Behrens A, Stetefeld A, Heller M, Ahrens M, Sachse K, Yogev D, Kirchhoff H. Antigen heterogeneity among isolates of Mycoplasma bovis is generated by high-frequency variation of diverse membrane surface proteins. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5066–5074. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5066-5074.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sachse K. Detection and analysis of mycoplasma adhesins. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;104:299–307. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-525-5:299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachse K, Grajetzki C, Rosengarten R, Hänel I, Heller M, Pfützner H. Mechanisms and factors involved in Mycoplasma bovis adhesion to host cells. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1996;284:80–92. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutcliffe C I, Russell R B. Lipoproteins of gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1123–1128. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1123-1128.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Belkum A, Scherer S, van Leeuwen W, Willemse D, van Alphen L, Verbrugh H. Variable number of tandem repeats in clinical strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5017–5027. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5017-5027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wern B W. A family of clostridial and streptococcal ligand-binding proteins with conserved C-terminal repeat sequences. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:797–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williamson M P. The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem J. 1994;297:249–260. doi: 10.1042/bj2970249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilton J L, Scarman A L, Walker M J, Djordjevic S P. Reiterated repeat region variability in the ciliary adhesin gene of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Microbiology. 1998;144:1931–1943. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q, Wise K S. Molecular basis of size and antigenic variation of a Mycoplasma hominis adhesin encoded by divergent vaa genes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2737–2744. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2737-2744.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, Wise K S. Localized reversible frameshift mutation in an adhesion gene confers a phase-variable adherence phenotype in mycoplasma. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:859–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]