Abstract

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations experience physical health, mental health, and socioeconomic status disadvantages relative to cisgender heterosexual populations. But extant population research tends to use objective measures and ignore subjective measures, examines well-being outcomes in isolation, and lacks information on less well-studied but possibly more disadvantaged SGM groups such as queer, transgender, and non-binary/genderqueer individuals. In this paper, we use Gallup’s National Health and Well-being Index (NHWI), which permits identification of a broader group of the SGM community. We estimate bivariate associations and Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models to examine differentials on five dimensions of well-being: (1) life purpose; (2) community belonging; (3) physical and mental health; (4) financial well-being; and (5) social connectedness. Results reveal stark disadvantages for most SGM groups; these disadvantages are most pronounced among bisexual, queer, and non-binary/genderqueer populations. Inter- and intra-group variations illuminate even greater disparities in well-being than prior research has uncovered, bringing us closer to a holistic profile of SGM well-being at the population level.

Keywords: Well-being, Health, Sexuality, Gender, SGM Populations

Introduction

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations, including people who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, transgender, and gender non-binary, are a growing demographic in the U.S. today (Jones 2021). Past research shows that SGM populations face disadvantages relative to heterosexual and cisgender populations on a range of health outcomes (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2020), including higher rates of poor physical health, poor mental health, and risky health behaviors (Boehmer et al. 2012; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2017; Gonzales et al. 2016; Liu and Reczek 2021; Meyer 2003; Reisner et al. 2015; Rimes et al. 2019; Ueno 2010). Those health disadvantages are theorized to be the result of structural and interpersonal anti-SGM stigma and discrimination described by the minority stress theory model (Brooks 1981; Meyer 1995).

Following that critically important research, three knowledge gaps prevent a more holistic understanding of SGM well-being. First, research tends to prioritize single “objective” physical and mental health outcomes, preventing a more inclusive view of a general well-being profile of SGM populations. The singular use of more “objective” measures (e.g., functional limitations, smoking use, cardiovascular disease) may underestimate the level of disadvantage faced by SGM populations. In contrast, leveraging both “objective” and “subjective” measures of well-being (e.g., having enough energy to do daily what one wants to do, satisfaction with standard of living relative to others) may provide better insight into how SGM people experience their everyday reality and illuminate how disadvantage accumulates. Second, compared to health, we know relatively less about community belonging, social connectedness, and financial well-being among SGM groups. Third, due to data limitations, research examining health and other disparities primarily compares gay, lesbian, same-sex partnered, and (less often) bisexual people to heterosexual people. Few population-level sources of data include other SGM people, particularly gender minorities (e.g., people who identify as transgender, gender non-binary), or compare SGM groups to one another. Such limitations have precluded a fuller view of the well-being of those who might be most disadvantaged.

To address the above limitations, we explore the associations of sexual and gender identities with five well-being indices—life purpose, community belonging, physical and mental health, financial well-being, and social connectedness.1 Advancing past work, we examine differences between SGM groups and cisgender and heterosexual people as well as differences within the SGM population. Given the fundamental association of SES, union status, and parental status with both SGM status and well-being (Spiker et at. 2021), we also consider how these characteristics explain differences in well-being. Our data come from Gallup’s National Health and Well-being Index, a nationally representative repeated cross-sectional study with a diverse sample of sexual and gender minorities. With these data, we shed new light on how sexual and gender identities are associated with well-being, showing more pronounced disparities than previous research.

Background

Social demographers have amassed an impressive body of work on the relationship between SGM identity and a variety of outcomes, most predominantly physical health and mental health (Hsieh and Liu 2019; Gonzales et al. 2016; Reczek et al. 2017; Williams and Mann 2017). However, research lacks a more holistic understanding of disparities in well-being relative to cisgender and heterosexual people, as well as well-being differences within the SGM population. To address these gaps, we outline minority stress theory (MST) (Brooks 1981; Meyer 1995) to articulate why SGM groups might experience disadvantages in well-being relative to cisgender and heterosexual people, as well as why some SGM subgroups may be disadvantaged relative to others. We then review empirical studies that reflect the current state of literature on the relationships between sexual and gender identities and well-being, broadly, noting how the use of indices can illuminate composite well-being disparities. In the final section, we theorize how composite measures of well-being provide an important opportunity to begin building a more complete profile of SGM well-being.

SGM Populations and Health, Financial, and Social Disparities

We apply the dominant paradigm used to explain SGM health disparities, minority stress theory (Brooks 1981), to examine health, financial, and social disparities. Minority stress is unique, chronic, and socially based, materializing from the totality of experience in the dominant culture (Meyer 1995). SGM individuals are subject to cisnormative (i.e., presumption of being cisgender) and heteronormative (i.e., presumption of heterosexuality) environments that normalize and legitimize heterosexuality and congruence between sex assigned at birth and gender identity (i.e., cisgender identity) (Martin 2009; Sumerau et al. 2016). Dominant culture subjects SGM people to distal stressors through direct experiences of discrimination, stigma, and violence (Herek and Berrill 1992; Meyer 2015) and proximal stressors through the expectations of discrimination, stigma, and violence (Ross 1985) which often result in the concealing of one’s identity and internalized queerphobia2 (DiPlacido 1998). Over time, the tolls of minority stressors accumulate in the form of stress, ultimately leading to physical and mental health disparities (Meyer 2003; Meyer et al. 2021; Liu and Reczek 2021).

Minority stress theory further emphasizes that minority stressors are unevenly distributed across the SGM population. For instance, issues like bisexual erasure, in which both heterosexuals and other sexual minorities invalidate bisexuality (Yoshino 1999), present unique stressors that likely differentially expose bisexual people to heightened stress, likely creating unique disadvantages in well-being. Additionally, transgender and gender non-binary people may face unique stressors that shape health in distinct ways from cisgender sexual minorities (Lagos 2019).

SGM Health Disparities and a Composite Measure of Health

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people experience more chronic conditions (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2017); worse health behavior such as drinking, smoking, and drug use (Amroussia et al. 2020; Boehmer et al. 2012; McCabe et al. 2018; Wheldon et al. 2019); and worse mental health outcomes than heterosexual people (Gonzales et al. 2016; Meyer 2003; Ueno 2010). Additionally, due to economic discrimination in society and bias in the medical community, SGM people are more likely to skip medication and health care than cisgender and heterosexual people (Dahlhamer et al. 2016). As a result of varying minority stressors, bisexuals have significantly higher risk of substance use, suicidality, and lower self-rated health, and are less likely to use primary and preventive health care, compared to their same-gender sexual minority and heterosexual counterparts (Dahlhamer et al. 2016; Boehmer et al., 2012; Hsieh and Liu 2019).

Gender minorities—people who identify as transgender, gender non-binary, genderqueer, agender, or other non-cisgender categories—experience stark disadvantages compared to cisgender people due to societal, institutional, and interpersonal stigma and discrimination, which present stressors that can undermine health and well-being. Gender minorities report higher rates of substance use and suicide ideation than cisgender men and cisgender women (Reisner et al. 2015; Rimes et al. 2019). Moreover, transgender people report elevated levels of skipping medication and healthcare visits (Dahlhamer et al. 2016; Shuster 2021), lower health insurance rates, and lower primary care and general healthcare access (Gonzales and Henning-Smith 2017) compared to the cisgender population. They also experience higher rates of psychological distress and mental disorders than cisgender people (Timmins et al. 2017). Lastly, recent research suggests that there are important within-group differences in the experiences of stressors and health outcomes among gender minorities. For instance, gender nonconforming individuals experience worse self-rated health than transgender women, in addition to cisgender men and cisgender women (Lagos 2018).

Taken together, this body of research suggests that SGM populations experience detriments in physical and mental health on a wide range of outcomes, at least in part due to minority stressors. Examining isolated measures, however, can obscure a more holistic picture of well-being, providing little information in the way of composite well-being. For example, heightened psychological distress and greater functional limitations relative to cisgender and heterosexual populations (Meyer et al. 2021; Hsieh and Liu 2019) might be fully or in part made up for by more health-promoting behaviors (e.g., exercising, eating healthily), the absence of other conditions (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, etc.), or other dimensions of health (e.g., BMI). For these reasons, analyzing differentials in a physical and mental health index—including functional limitations, psychological health, health behaviors, and the presence of certain conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and cancer—among a nationally representative sample provides a comprehensive understanding of health beyond that provided by examining isolated outcomes.

SGM Socioeconomic Disparities and a Composite Measure of Financial Well-being

SGM groups experience socioeconomic disadvantages resulting from heterosexism and cisnormativity. Resume audit studies show employment discrimination against gay men (Tilcsik 2011) and queer women (Mishel 2016), and a plethora of studies show that gay men tend to earn less than heterosexual men while lesbians earn about the same or more than heterosexual women (Badgett 1995; Baumle and Poston 2011; Black et al. 2003; Denier and Waite 2019). However, bisexual men and women tend to experience the greatest wage penalties relative to heterosexuals and gays and lesbians, partly driven by discrimination in the workplace (Mize 2016). Indeed, sexual minorities are more than four times more likely than heterosexuals to report being fired from a job (Mays and Cochran 2001), while transgender individuals report heightened workplace discrimination relative to cisgender people (Granberg et el. 2020; James et al. 2016). SGM individuals also experience higher risk of poverty (Badgett et al. 2019; James et al. 2016). Disparities in education also exist, wherein gay and lesbian individuals have higher average educational attainment than heterosexuals, but bisexual women (Black et al. 2000; Mollborn and Everett 2015) and transgender adults (Carpenter et al. 2020) experience disadvantages in high school and college completion relative to their cisgender and heterosexual counterparts.

Minority stressors may shape financial well-being given that SGM people tend to experience disadvantages attributable to discrimination and institutional exclusion, such as when it comes to securing a job, unemployment rates, and wage penalties. Yet beyond these measures, we know less about how SGM individuals experience and rate their subjective financial well-being. SGM populations might be disadvantaged relative to cisgender and heterosexual populations subjectively—having insufficient economic resources to do what one wants to do daily, frequent worries about money, and lower levels of satisfaction with standard of living (Chai and Maroto 2020). An index of these measures, combined with a nationally representative sample, can illuminate deeper financial disparities and subjective stratification that objective, single measures cannot.

SGM Social Disparities and Composite Measures of Social Well-being

Although research on other aspects of SGM well-being (e.g., life purpose, community belonging, and social connectedness) is sparse, some existing evidence links SGM status to neighborhoods and social networks. For instance, sexual minorities tend to think of their neighborhoods as less trustworthy and less helpful than heterosexuals do (Henning-Smith and Gonzales 2018; King 2016), save for those who live in “gayborhoods”—neighborhoods containing a predominant number or at least a sizable minority of LGBTQ residents (Ghaziani 2015). Similarly, sexual minorities in later life tend to experience more loneliness than heterosexuals (Hsieh and Liu 2021), which is largely attributable to lower partnership rates and, to a lesser extent, a lack of familial support and friendship strain. Sexual minorities enjoy larger networks than heterosexuals, but fewer family-of-origin ties (Fischer 2022). However, research is relatively scant and overwhelmingly focuses on gay and lesbian people, ignoring queer and bisexual people as well as gender minorities. Minority stressors in the form of queerphobia in one’s neighborhood or tension with or estrangement from one’s family-of-origin could lead to social disparities (Reczek and Bosley-Smith 2022).

Similar to the potential of health and financial well-being indices, there are benefits to examining life purpose, community belonging, and social connectedness indices at the population level. Those aspects of well-being are relatively overlooked in past research on SGM people but important for holistically understanding SGM well-being. In addition, these measures can illuminate how individuals take stock of the broader state of their lives. The life purpose index measures whether people feel they are reaching their goals and enjoying what they do each day (Zilioli et al. 2015). The community belonging index shows whether people feel as if where they live is great for them, if they feel safe and secure, and if they derive pride from where they live (Ross 2002). Finally, the social connectedness index provides knowledge beyond what examining loneliness or networks can offer (Fischer 2022; Hsieh and Liu 2021), including the presence of supportive and loving relationships and positive energy from a support network.

Toward a Broader Understanding of Well-being for Sexual and Gender Minorities

As past research and minority stress theory suggests, SGM populations experience acute disadvantages relative to cisgender and heterosexual populations in physical and mental health, with relatively less work examining other aspects of well-being. Yet most analyses have examined outcomes in isolation, sacrificing breadth for depth, and few have leveraged the strength of subjective measures. Consequently, examining both objective and subjective measures of well-being should be a priority for social demographers interested in SGM well-being.

The strength of well-being profiles lies in their ability to capture perceptions of well-being in a more holistic way. Asking people to assess various aspects of their lives—from health to community to finances—is an important way to understand well-being. When people examine their lives, they are unlikely to do so as it relates to single outcomes in isolation from other dimensions of their lives. For instance, rather than thinking about one aspect of health, people are more likely to think about the state of their health holistically, taking into account their health behaviors, how they feel, their functional limitations, and their medical conditions, among other things, rather than to think about one aspect as separate from others. Indeed, this is one reason why self-rated health is an important and independent predictor of mortality, morbidity, and disability (Idler and Benyamini 1997; Jylhä 2009). When it comes to finances, we contend that people are unlikely to examine their educational attainment in reference to averages or perhaps even to others, and are instead thinking about the ability to provide food for themselves or their families (Gundersen and Ziliak 2015), whether they can do what they want to do with the money they have (Ringen 1981), and whether they worry about making ends meet (Cooper 2014). We posit that the five indices of well-being provide a window into collective understandings of well-being.

In this study, we propose taking a broader view of “well-being” to include (1) life purpose; (2) community belonging; (3) physical and mental health; (4) financial well-being; and (5) social connectedness. Gallup’s indices operationalize each dimension of well-being, allowing us to examine composite well-being differentials. In doing so, we provide a more holistic demographic profile of SGM well-being at the population level than previous research. Our well-being analysis is one of the first to harness Gallup’s unparalleled SGM sample. We include sexual minorities who identify as queer, same-gender loving, or more than one sexual identity, in addition to gay, lesbian, and bisexual; we also include transgender men, transgender women, and gender non-binary/genderqueer individuals (Schilt and Lagos 2017). Our study improves upon past work that relied on limited sexual identity categories (e.g., lesbian, gay), inferred sexual identity from partnership status, or binary measures of sex and/or gender—which conflate sex and gender and preclude identification of transgender and other gender minority populations (Westbrook and Saperstein 2015; Westbrook et al. forthcoming). Importantly, we move research forward by not only comparing SGM people to cisgender and heterosexual people, but also comparing within SGM populations to understand who is most vulnerable to poor well-being.

Data and Method

Data

We use data from Gallup’s National Health and Well-being Index (NHWI), proprietary data from Gallup’s U.S. Daily Tracking Microdata files. The survey began in 2008, using a repeated cross-section design, sampling around 1,000 respondents each day on a wide array of topics including politics, health and well-being, and sociodemographic characteristics. We limit our analysis to 2018 and 2019 due to recency and the level of detail on our predictors and outcomes of interest.

Starting in January 2018, NHWI data were collected from U.S. adults aged 18 and older using a dual mail and web-based methodology. Gallup sampled individuals via an address-based sampling frame, which included a representative list of all U.S. households in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Sample members were provided a mail survey and a link with a unique access code to complete the survey online if interested. Respondents within households were chosen based on which member has the next birthday. Gallup sent surveys once a month at the start of the month and closed data collection for that month on the fifth day of the following calendar month, and survey responses returned after that date were not accepted. In 2018, the response rate was 17.3%. Most data were collected in 2018, as we discuss below, while a small portion of data come from 2019. This was due to a deteriorating funding situation at Gallup that limited data collection.

Outcome Variables

Our dependent variables include five indices of various dimensions of health and well-being: (1) life purpose; (2) community belonging; (3) physical and mental health; (4) financial well-being; and (5) social connectedness. The items and response categories are described in Table 1. The life purpose index includes five measures of feelings of meaningfulness and inspiration. The community belonging index is comprised of four measures and captures respondents’ feelings of safety, pride, and belonging in their communities. The physical and mental health index, composed of sixteen different items, includes many measures of physical and mental health and how they affect daily life. The financial well-being index includes four items that tap into subjective measures of socioeconomic status. Finally, the social connectedness index includes four measures that capture the strength of close relationships with family and significant others. The five well-being indices were created by Gallup and leverage the insights of both objective and subjective measures to profile a broad view of well-being. Each index has a range of 0–100, with higher values indicating better well-being.

Table 1.

Breakdown of Well-being Indices

| Well-being Index | Individual Items | Response Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Life purpose | There is a leader in your life who makes you enthusiastic about the future | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree |

| You like what you do every day | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| In the past 12 months, you have reached most of your goals | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| You get to use your strengths to do what you do best every day | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| You learn or do something interesting every day | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| Residential Community Belonging | The city or area where you live is a perfect place for you | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree |

| You are proud of your community or the area where you live | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| You always feel safe and secure | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| In the last 12 months, you have received recognition for helping to improve the city or area where you live | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| Physical and Mental Health | Your physical health is near-perfect | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree |

| In the last seven days, you have felt active and productive every day | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| Over the last two weeks, how often have you had little interest or pleasure in doing things? | Nearly every day, more than half the days, several days, not at all | |

| Do you have any health problems that prevent you from doing any of the things people your age normally can do? | Yes, no | |

| Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday?… Physical pain | Yes, no | |

| Did you eat healthy all day yesterday? Do you smoke? | Yes, no | |

| Have you ever been told by a physician or nurse that you have any of the following, or no? | ||

| … High blood pressure | Yes, no | |

| … High cholesterol | Yes, no | |

| … Diabetes | Yes, no | |

| … Depression | Yes, no | |

| … Heart attack | Yes, no | |

| … Cancer | Yes, no | |

| In the last seven days, on how many days did you | ||

| … Exercise for 30 or more minutes | 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 4 days, 5 days, 6 days, 7 days | |

| … Have five or more servings of fruits and vegetables | 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 4 days, 5 days, 6 days, 7 days | |

| BMI | ||

| What is your height? | Feet Inches | |

| What is your approximate weight? | Pounds | |

| Financial Well-being | Have there been times in the past twelve months when you did not have enough money to buy food that you or your family needed? | Yes, no |

| You have enough money to do everything you want to do. | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| In the last seven days, you have worried about money. | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| Compared to the people you spend time with, you are satisfied with your standard of living. | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| Social Connectedness | Your relationship with your spouse, partner, or closest friend is stronger than ever. | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree |

| You always make time for regular trips or vacations with friends and family. | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| Someone in your life always encourages you to be healthy. | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| Your friends and family give you positive energy every day. | Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree |

Gallup created each well-being index to comprehensively and reliably capture global aspects of well-being. The indices show valid and reliable psychometric measurement, high correlation with previously validated well-being measures, and predictive power regarding important outcomes, such as productivity and health care use (see Sears et al. 2014). To develop the indices, Gallup engaged in the following steps: (1) item reduction, to reduce the number of items necessary to achieve measurement goals from widely accepted health and well-being items; (2) exploratory factor analysis, to identify the underlying latent data structure and provide insight into scoring; (3) scoring, whereby items were assigned to one of the five latent factors (purpose, community, physical, financial, and social well-being), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the structural validity of the model; and (4) score validation, using accepted criteria, such as goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values. The five well-being indices show impressive fit to the data, high or acceptable reliability, and very high convergent validity between indices and other measures, as well as impressive Cronbach’s alpha scores, suggesting high consistency among items in each index (see Sears et al. 2014).

Independent Variables

To capture a broader picture of the SGM population, we use two independent variables: sexual identity and gender identity. Scholars have long suggested incorporating additional sexual identity and gender response categories to facilitate the identification of SGM populations (Westbrook and Saperstein 2015; Westbrook et al. forthcoming; Lagos and Compton 2021). In this paper, we leverage recent advancements in measurement and data collection to include more diverse SGM populations. First, we include queer identified people, a growing subset of the SGM community, same-gender loving individuals3, and those who identify as more than one sexuality, alongside lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Second, we use a three-way measure of gender to include transgender and non-binary/genderqueer respondents in our analysis.

For sexual identity, respondents were asked, “Which of the following do you consider yourself to be? You may select one or more.” Response categories included (1) Straight or heterosexual, (2) Lesbian, (3) Gay, (4) Bisexual, (5) Queer, and (6) Same-gender loving. We collapsed lesbian and gay into one category due to the gendered nature of the terms.4 A sizable portion of sexual minorities identified themselves as belonging to more than one sexual identity category, so we created an additional response category to capture these individuals.5

Our second independent variable is gender identity. We constructed our gender identity indicator from a three-part gender question that circumvents problems with binary sex/gender measures and allows for the identification of transgender and gender nonconforming respondents. Respondents were first asked about their sex assigned at birth: “On your original birth certificate, was your sex assigned as male or female?” and could answer (1) Male or (2) Female. Next, a question was asked: “Do you currently describe yourself as a man, woman, or transgender?”6 If a participant identified as transgender, a follow-up question appeared that asked “Are you…?” Response categories included (1) “Trans Woman (Male-to-female),” (2) “Trans Man (Female-to-male),” and (3) “Nonbinary/Genderqueer.” We used this three-part gender question to create a new gender indicator. Respondents were coded as cisgender men if assigned male at birth and currently identify as men and as cisgender women if assigned female at birth and currently identify as women. Respondents were coded as transgender men if assigned female at birth and currently identify as men or if assigned female at birth, identify as transgender, and identify as transgender men. Respondents were coded as transgender women if assigned male at birth and identify as women or if assigned male at birth, identify as transgender, and identify as transgender women. Finally, respondents were coded as non-binary/genderqueer if they currently identify as transgender and then, in the follow up question, identify as non-binary/genderqueer regardless of the sex they reported being assigned at birth. Based on the wording and branching of this gender indicator, only those non-binary/genderqueer individuals who also identify as transgender are identifiable in these data. While some non-binary people consider themselves transgender, others do not (see Darwin 2021; Garrison 2018), and thus our sample of non-binary/genderqueer people is inclusive only of those who also identify as transgender. We return to the implications of this methodological limitation in the discussion section.

Covariates

We adjust for several sociodemographic characteristics in our models that might confound the association between SGM identity and well-being. Sociodemographic variables include age (in years), race/ethnicity (White, Other7, Black, Asian, Hispanic), region (South, Northeast, Midwest, West), and year (2018, 2019). We also include objective measures of SES, including current employment status (yes, no), education (less than high school, high school degree or GED, technical/vocational/some college, college degree or more), and income (under $11,999, $12,000 to $35,999, $36,000 to $59,999, $60,000 to $89,999, $90,000 to $119,999, and $120,000 and over). Finally, we control for union status (single/never married, married, cohabiting/domestic partnership, and divorced/widowed/separated), and whether any children are present in the household (yes, no).

We adjust for sociodemographic variables to account for the possibility that some existing sociodemographic differences between SGM groups might influence our primary associations. We then adjust for SES characteristics, union status, and residential parent status in separate models because these characteristics have been shown to be influenced by sexual and gender identities (e.g., Mize 2016; Mishel 2016) and are predictive of health and well-being (e.g., Clouston and Link 2021). Additionally, because a substantial portion of the measures used in the indices are subjective, and any observed subjective differences might be the result of objective differences among and between SGM groups, we adjust for more objective indicators of SES and family characteristics. In doing so we can demonstrate which results remain significant after adjusting for SES, union status, and residential parent status.

Analytic Plan

From an eligible 123,200 individuals, we limited the analytic sample to 107,310 after excluding 15,890 individuals who had no reported well-being index values across one or more of the outcomes, or who did not report their sexual identity or sex or gender identity. To avoid the additional loss of data, we employed multiple imputation using chained equations (imputations = 20) to impute missing values on our covariates: (a) race (n = 969); (b) age (n = 626); (c) employment status (n = 493); (d) income (n = 4,628); (e) education (n = 211); (f) union status (n = 162); and (g) residential parent status (n = 1,160). We did not impute missing information on our main independent variables because it is reasonable to expect that those who refused to report their sexual or gender identity are qualitatively different than those who did, and that this might have implications for respondents’ well-being.8 Multiply imputed results are nearly identical to results using listwise deletion, highlighting result robustness. To account for the sampling design, adjust for nonresponse, and achieve population representation, we weight the analyses using the sample weights provided by Gallup. We employed the 2018 sample weights for the 94% of the sample surveyed in 2018 and the 2019 sample weights for the remaining 6% surveyed the following year.

We first discuss descriptive statistics of our analytic sample prior to multiple imputation. We then present weighted bivariate analyses of the association between sexual and gender identities and the five well-being indices, using Bonferroni-adjusted significance tests. Finally, we estimate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models to predict each well-being index as a function of sexual identity and gender identity. In the first set of models, we include basic sociodemographic characteristics: age, race, region, and year of survey. In the second set of models, we add objective socioeconomic status (employment status, education, and income) characteristics, union status and residential parent status variables to examine whether these measures explain any of the association between SGM identities and our measures of well-being. All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 2 shows the unweighted and weighted descriptive statistics for our sample prior to multiple imputation. The weighted means are 59.3 for life purpose, 61.8 for community belonging, 61.0 for physical and mental health, 61.0 for financial well-being, and 50.7 for social connectedness. About 2.3% of the sample are gay or lesbian, 2.2% are bisexual, 0.3% are queer, 0.9% are same-gender loving, and 1.3% identified as more than one sexual identity. In total, sexual minorities comprise more than 7% percent of the sample. Lastly, transgender men comprise 0.17% of the sample, 0.12% of the sample are transgender women, and 0.16% are non-binary/genderqueer.

Table 2.

Unweighted and Weighted Descriptive Statistics (N = 100,142)

| Unweighted | Weighted | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Sample Size (N) | Mean/Percentage (SD) | Mean/Percentage (SD) | |

|

|

|||

| Purpose Index | 59.39 (19.45) | 59.29 (19.79) | |

| Community Index | 63.74 (17.38) | 61.76 (18.05) | |

| Physical Index | 61.75 (15.55) | 60.96 (15.27) | |

| Financial Index | 66.03 (24.35) | 60.98 (24.91) | |

| Social Index | 59.48 (21.58) | 50.70 (20.9) | |

| Sexual Identity | |||

| Heterosexual (ref) | 94,954 | 94.82 | 92.98 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 2,103 | 2.10 | 2.28 |

| Bisexual | 1,316 | 1.31 | 2.20 |

| Queer | 191 | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| Same-gender Loving | 718 | 0.72 | 0.93 |

| More than one | 860 | 0.86 | 1.27 |

| Gender Identity | |||

| Cisgender Man (ref) | 44,833 | 44.77 | 48.64 |

| Cisgender Woman | 55,047 | 54.97 | 50.91 |

| Transgender Man | 88 | 0.09 | 0.17 |

| Transgender Woman | 101 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Non-binary/Genderqueer | 73 | 0.07 | 0.16 |

| Age | 56.79 (16.36) | 47.56 (17.54) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 82,286 | 82.17 | 66.84 |

| Other | 2,742 | 2.74 | 3.56 |

| Black | 6,009 | 6.00 | 10.74 |

| Asian | 3,058 | 3.05 | 4.10 |

| Hispanic | 6,047 | 6.04 | 14.76 |

| Region | |||

| South | 34,326 | 34.28 | 37.26 |

| Northeast | 17,696 | 17.67 | 17.54 |

| Midwest | 26,281 | 26.24 | 21.41 |

| West | 21,839 | 21.81 | 23.79 |

| Year | |||

| 2018 | 93,785 | 93.65 | 93.65 |

| 2019 | 6,357 | 6.35 | 6.35 |

| Employed | 60,442 | 60.36 | 68.32 |

| Education | |||

| Less than HS | 2,533 | 2.53 | 8.70 |

| HS Degree | 16,532 | 16.51 | 27.61 |

| Technical/Vocational/Some College | 32,891 | 32.84 | 29.56 |

| College | 22,231 | 22.20 | 17.19 |

| Advanced Degree | 25,955 | 25.92 | 16.94 |

| Income | |||

| Under $11,999 | 6,491 | 6.48 | 10.99 |

| $12,000 to $35,999 | 20,320 | 20.29 | 21.58 |

| $36,000 to $59,999 | 19,873 | 19.84 | 19.39 |

| $60,000 to $89,999 | 18,493 | 18.46 | 17.00 |

| $90,000 to $119,999 | 13,013 | 12.99 | 11.78 |

| $120,000 and over Union Status | 21,952 | 21.92 | 19.26 |

| Single/Never Married | 13,589 | 13.57 | 21.46 |

| Married | 56,560 | 56.48 | 55.71 |

| Cohabiting/Domestic Partnership | 4,113 | 4.11 | 6.40 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 25,880 | 25.84 | 16.43 |

| Residential Parent Status | 23,596 | 23.56 | 35.16 |

Note: Results for non-imputed sample.

Bivariate Results

Next, we turn to weighted bivariate analyses of well-being by sexuality and gender identity, respectively, in Table 3. Table 3 shows that gays and lesbians experience disadvantages across each measure of well-being relative to heterosexuals except for physical and mental health, with the largest disparities in financial well-being and social connectedness. Bisexual and queer people are the most disadvantaged across each well-being index relative to heterosexuals and gays and lesbians. On financial well-being, for instance, bisexuals have an average score of 45.4, 16.5 units lower than heterosexuals (p < 0.001). Table 3 further shows that on physical health, queer people tend to average 52.3, nearly 9.0 units lower than heterosexuals (p < 0.001). Further, same-gender loving individuals, an oft-overlooked but important sexual minority group, face only physical and mental health and financial well-being disadvantages relative to heterosexual people. In fact, same-gender loving people experience advantages relative to heterosexuals and other sexual minorities on most well-being indices. Finally, those who identified as more than one sexual identity tend to experience disadvantage across each index relative to heterosexuals.

Table 3.

Weighted Bivariate Analyses showing Average Well-being Index Scores by Sexuality and Gender Identities (N = 107,310)

| Life Purpose | Community Belonging | Physical and Mental Health | Financial Well-being | Social Connectedness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

|

|

|||||

| Sexual Identity | |||||

| Heterosexual | 59.59 (19.70) | 62.08 (17.93) | 61.27 (15.17) | 61.92 (24.59) | 60.02 (20.86) |

| Gay/Lesbian | 58.12** (19.72) | 59.59***(18.73) | 60.43 (15.33) | 55.94*** (26.90) | 57.49*** (22.23) |

| Bisexual | 52.68***a (20.97) | 53.89***a (19.81) | 54.78***a (16.07) | 45.42***a (25.47) | 53.82***a (21.57) |

| Queer | 52.66***a (23.23) | 50.50***a (21.94) | 52.32***a (17.32) | 44.54***a (23.80) | 50.40***a (22.55) |

| Same-gender Loving | 63.58***abc (20.81) | 65.21***abc (20.82) | 59.36**bc (15.52) | 55.77***bc (23.69) | 61.83abc (21.66) |

| More than one | 54.00***ad (21.47) | 56.82***abcd (19.47) | 57.59***abc (16.02) | 51.18***abcd (26.00) | 56.25***bcd (21.42) |

| Gender Identity | |||||

| Cisgender Man | 59.61 (19.63) | 62.03 (17.91) | 61.44 (14.86) | 63.40 (24.32) | 58.94 (20.99) |

| Cisgender Woman | 59.20** (19.96) | 61.62** (18.26) | 60.68*** (15.58) | 59.19*** (25.13) | 60.66*** (20.84) |

| Transgender Man | 56.44 (21.03) | 52.17***x (22.51) | 56.34* (17.41) | 49.34***x (25.20) | 53.51x (20.81) |

| Transgender Woman | 51.00***x (23.73) | 56.98* (22.96) | 55.12***x (17.00) | 48.71***x (26.76) | 52.21**x (22.56) |

| Non-binary/Genderqueer | 46.05***xy (25.29) | 47.11***xz (20.79) | 48.67***xyz (16.08) | 43.98***x (25.57) | 41.44***xy (25.58) |

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

compared to heterosexual. All tests are two-tailed.

Compared to gay/lesbian (p < 0.05).

Compared to bisexual (p < 0.05).

Compared to queer (p < 0.05).

Compared to same-gender loving (p < 0.05)

Compared to cisgender woman (p < 0.05).

Compared to transgender man (p < 0.05).

Compared to transgender woman (p < 0.05).

Table 3 shows bivariate results for well-being indices across gender identity categories. Transgender men tend to be disadvantaged on community belonging, physical and mental health, and financial well-being relative to cisgender men and on social connectedness relative to cisgender women. On community belonging, transgender men score on average 9.9 points lower than cisgender men (p < 0.001) and 9.5 points lower than cisgender women (p < 0.001), and the discrepancies are even greater when it comes to financial well-being. Transgender women and non-binary/genderqueer individuals experience disadvantages on all indices relative to cisgender men, providing initial evidence that these two gender minority groups might be the worst off when it comes to well-being. Bivariate results show stark disparities in financial well-being for transgender women and non-binary/genderqueer populations relative to cisgender populations. On the financial well-being index, transgender women average 48.7, and non-binary/genderqueer individuals average about 44.0, which are 14.7 (p < 0.001) and 19.4 (p < 0.001) units lower, respectively, compared to cisgender men.

Regression Results

Model 1 in Table 4 shows the OLS regression results of each of the five well-being indices on sexual and gender identities adjusting for basic demographic covariates (age, race, region, and year of survey). Sexual minorities experience many disadvantages relative to heterosexual individuals. Gay and lesbian people report significantly worse well-being than heterosexual people on each index except community belonging, where a bivariate difference was explained by sociodemographic characteristics. Bisexual individuals fare worse than heterosexuals and gay/lesbian populations on all well-being indices, especially financial well-being. Queer people also experience disadvantage relative to heterosexuals except in life purpose, where a bivariate disparity was explained by added controls. Controlling for basic sociodemographic factors accounted for the same-gender loving group’s disadvantage on physical and mental health, compared to heterosexual populations. Model 1 of Table 4 further shows that the same-gender loving are only disadvantaged relative to heterosexuals on financial well-being. Finally, disadvantages persist for those who identified as more than one sexual identity relative to heterosexuals.

Table 4.

Weighted OLS Regression Results Predicting Well-being Indices (N = 107,310)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | |

|

| ||

| Life Purpose | ||

|

| ||

| Sexual Identity (reference = heterosexual) | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | −1.61* (0.69) | −1.19 (0.69) |

| Bisexual | −7.08***a (0.95) | −4.52***a (0.95) |

| Queer | −5.26 (2.81) | −3.39 (2.63) |

| Same-gender Loving | 4.10***abc (105) | 6.99***abc (107) |

| More than one | −5.19***ad (120) | −3.61**d (122) |

| Gender Identity (reference = cisgender men) | ||

| Cisgender Woman | −0.28 (0.20) | 1.13*** (0.20) |

| Transgender Man | −0.58 (3.12) | 1.06 (3.01) |

| Transgender Woman | −6.21 (3.48) | −4.50 (3.57) |

| Non-Binary/Genderqueer | −9.35*x (4.04) | −6.94x (3.73) |

| R-squared | 0.01 | 0.07 |

|

| ||

| Community Belonging | ||

|

| ||

| Sexual Identity (reference = heterosexual) | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | −1.26 (0.68) | −0.73 (0.68) |

| Bisexual | −5.68***a (0.89) | −4.01***a (0.90) |

| Queer | −7.00**a (2.56) | −5.64* (2.53) |

| Same-gender Loving | 2.76*abc (113) | 4.89***abc (114) |

| More than one | −2.51*bd (110) | −1.28bd (109) |

| Gender Identity (ref = cisgender men) | ||

| Cisgender Woman | −0.15 (0.19) | 0.65*** (0.19) |

| Transgender Man | −5.59 (3.58) | −4.22 (3.49) |

| Transgender Woman | −2.17 (3.20) | −1.24 (3.29) |

| Non-Binary/Genderqueer | −8.67**x (3.31) | −7.26*x (3.12) |

| R-squared | 0.03 | 0.06 |

|

| ||

| Physical and Mental Health | ||

|

| ||

| Sexual Identity (ref = heterosexual) | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | −1.19* (0.53) | −1.42** (0.54) |

| Bisexual | −6.84***a (0.71) | −4.90***a (0.71) |

| Queer | −7.56***a (196) | −6.69***a (178) |

| Same-gender Loving | −1.23bc (0.85) | 1.56abc (0.82) |

| More than one | −3.56***ab (0.87) | −2.48*bcd (0.89) |

| Gender Identity (reference = cisgender men) | ||

| Cisgender Woman | −0.45** (0.14) | 0.61*** (0.15) |

| Transgender Man | −2.53 (2.42) | −0.92 (2.31) |

| Transgender Woman | −3.50 (2.38) | −2.17 (2.32) |

| Non-Binary/Genderqueer | −8.54**x (2.54) | −6.40**x (2.23) |

| R-squared | 0.02 | 0.08 |

|

| ||

| Financial Well-being | ||

|

| ||

| Sexual Identity (reference = heterosexual) | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | −4.60*** (0.93) | −5.28*** (0.85) |

| Bisexual | −11.72***a (104) | −7.09*** (1.01) |

| Queer | −10.98***a (2.54) | −8.28*** (2.16) |

| Same-gender Loving | −5.75***b (125) | 2.11abc(123) |

| More than one | −6.66***b (132) | −3.61**bd (135) |

| Gender Identity (reference = cisgender men) | ||

| Cisgender Woman | −3.52*** (0.24) | −0.71** (0.23) |

| Transgender Man | −5.64 (3.56) | −0.28 (2.95) |

| Transgender Woman | −7.80* (3.67) | −4.34 (4.51) |

| Non-Binary/Genderqueer | −7.62 (3.98) | −3.00 (3.75) |

| R-squared | 0.07 | 0.25 |

|

| ||

| Social Connectedness | ||

|

| ||

| Sexual Identity (reference = heterosexual) | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | −2 10** (0.76) | −1 46 (0.75) |

| Bisexual | −6 49***a (0.90) | −3.58*** (0.88) |

| Queer | −6.86** (2.33) | −4.68* (2.23) |

| Same-gender Loving | 1.93abc (118) | 5.1***abc (122) |

| More than one | −2.92**bd (105) | −0.98d (106) |

| Gender Identity (reference = cisgender men) | ||

| Cisgender Woman | 1.98*** (0.20) | 3.58*** (0.20) |

| Transgender Man | −2.91 (2.82) | −0.75 (2.69) |

| Transgender Woman | −4.36x (3.00) | −1.74 (3.04) |

| Non-Binary/Genderqueer | −13.82***xy (3.97) | −11.71**xyz (3.48) |

| R-squared | 0.01 | 0.09 |

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

compared to heterosexual. All tests are two-tailed.

Compared to gay/lesbian (p < 0.05).

Compared to bisexual (p < 0.05).

Compared to queer (p < 0.05).

Compared to same-gender loving (p < 0.05)

Compared to cisgender woman (p < 0.05).

Compared to transgender man (p < 0.05).

Compared to transgender woman (p < 0.05).

The basic sociodemographic controls introduced in Model 1 of Table 4 explain transgender men’s bivariate disadvantages relative to cisgender men. In contrast, transgender women fare worse than cisgender men on financial well-being, and worse than cisgender women on social connectedness. After adding basic sociodemographic controls, transgender women no longer experienced lower life purpose, community belonging, and physical and mental health scores relative to the cisgender population. Non-binary/genderqueer people remain disadvantaged across each well-being index except for financial well-being relative to cisgender men, faring the worst on the social connectedness index relative to cisgender peers. In fact, non-binary/genderqueer populations tend to score lower on the social connectedness index compared to transgender men, another gender minority group.

The Role of Socioeconomic Status, Union Status, and Residential Parental Status

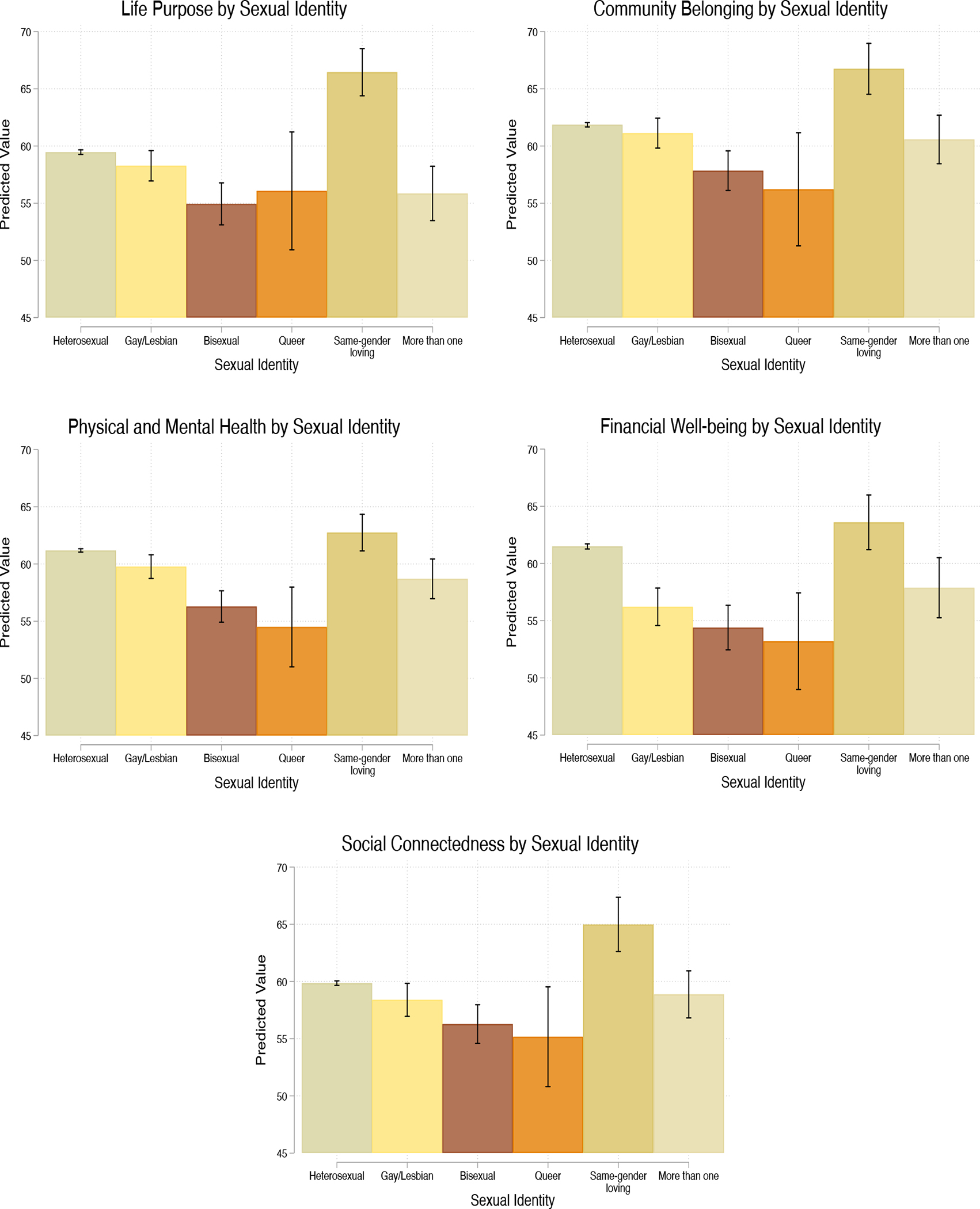

In Model 2 of Table 4, we add employment status, income, education, union status, and whether children are present in the household as additional covariates. After adjusting for these additional controls, most associations remain negative across sexual identity categories, suggesting that socioeconomic, union, and residential parent statuses do not explain most of the well-being disparities. Gays and lesbians score lower on physical and mental health and financial well-being relative to heterosexuals after adjusting for all covariates. Bisexuals fare worse on each outcome relative to heterosexuals and score lower than gays and lesbians and same-gender loving individuals on life purpose, community belonging, and physical and mental health. Disadvantages for queer people persisted compared to heterosexuals on community belonging, physical and mental health, financial well-being, and social connectedness indices with controls in Model 2 of Table 4. Conversely, same-gender loving people scored higher than heterosexuals on several well-being measures after accounting for SES, union status, and whether children were present in the home. This implies that SES and family status differentials suppress differences between same-gender loving and heterosexual respondents. Finally, those who identified as more than one sexual identity tend to experience disadvantages on life purpose, physical and mental health, and financial well-being relative to heterosexuals net of additional covariates. Figure 1 shows the predicted values of the well-being indices across categories of the sexual identity variable, with covariates held at their means.

Figure 1. Predicted Values of Well-being Indices by Sexual Identity.

Note: Estimates are the average predicted values of life purpose, community belonging, physical and mental health, financial well-being, and social connectedness indices values across categories of sexual identity, based on results from Model 2. All results adjust for age, race, region, year, employment status, education, household income, union status, and residential children. All covariates are centered at their means (N=107,310).

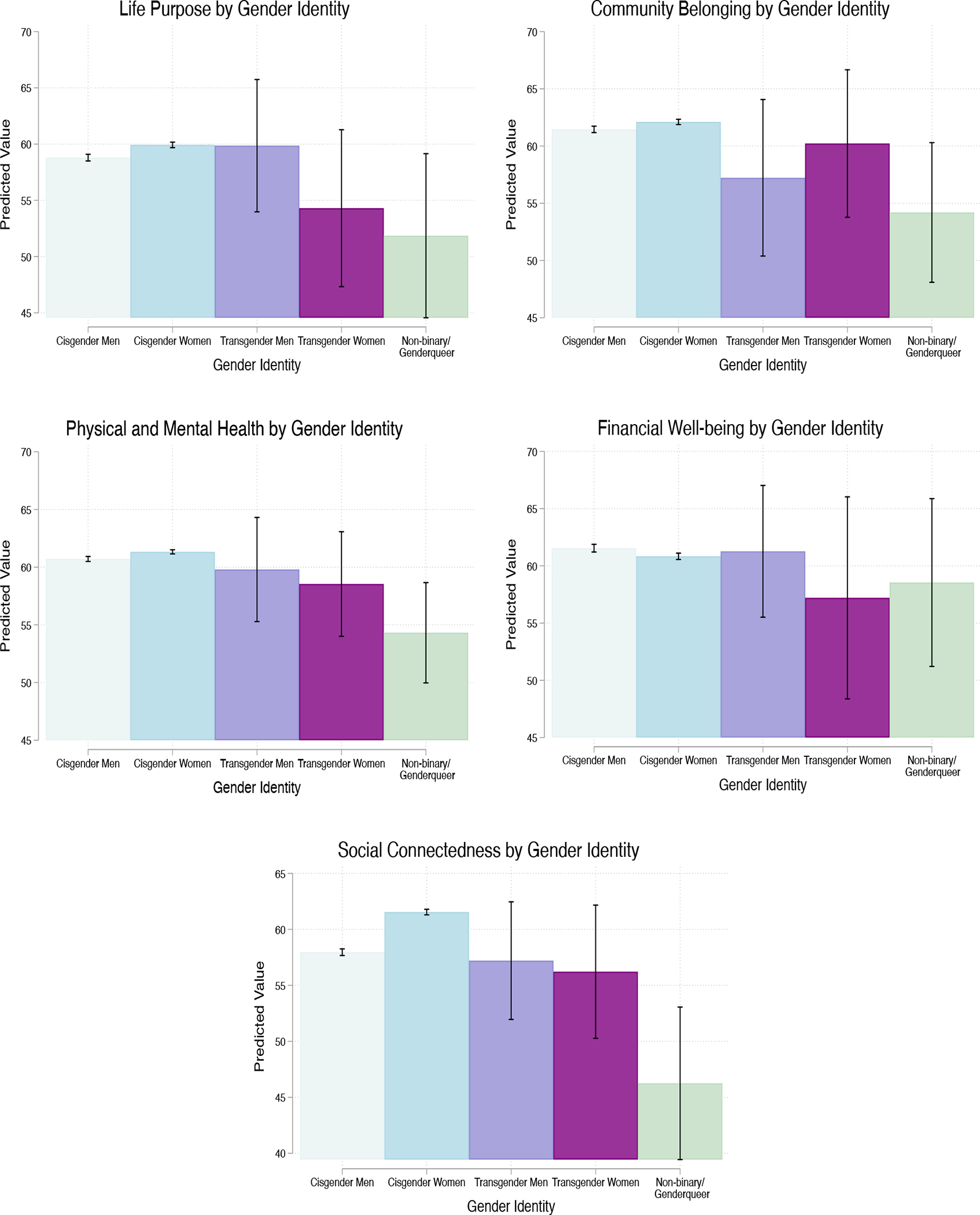

Model 2 in Table 4 shows that non-binary/genderqueer people score lower on community belonging, physical and mental health, and social connectedness relative to cisgender men and cisgender women, in addition to lower life purpose scores compared to cisgender women. They appear to fare the worst on social connectedness, where a detriment of more than 10 units separates them from cisgender men (p < 0.001). Importantly, this group also averages lower well-being scores than some other gender minorities across some outcomes, such as lower social connectedness scores than transgender men and transgender women, underscoring acute disadvantage. Figure 2 shows the predicted values of the well-being indices across categories of the gender identity variable, holding covariates at their means.

Figure 2. Predicted Values of Well-being Indices by Gender Identity.

Note: Estimates are the average predicted values of life purpose, community belonging, physical and mental health, financial well-being, and social connectedness indices values across categories of gender identity, based on results from Model 2. All results adjust for age, race, region, year, employment status, education, household income, union status, and residential children. All covariates are centered at their means (N=107,310).

There are other cases where the inclusion of SES, union status, and residential children controls fully explain associations between sexuality or gender identity and our well-being outcomes in Model 2 of Table 4. Additional controls account for the disadvantages gays and lesbians experienced on life purpose and social connectedness, and that the same-gender loving experienced on financial well-being, relative to heterosexuals. After adding these additional controls, non-binary/genderqueer people no longer fare worse on life purpose and transgender women no longer experienced worse financial well-being compared to cisgender men. After adding all controls, transgender women tend to score similarly on the well-being indices relative to cisgender people.

Discussion

A burgeoning body of work finds physical health and mental health disadvantages for SGM populations compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts, with additional disadvantages for bisexuals compared to their gay and lesbian counterparts (e.g., National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2020; Hsieh and Shuster 2021; Meyer et al. 2021). Those findings are often explained by the distal and proximal stressors unique to one’s minority status, such as discrimination, stigma, and violence (Meyer 2003; Williams and Mann 2017). While past work contributed immensely to our understanding of SGM health, the literature lacks a holistic account of well-being. In analyzing a population-based SGM sample, we found global well-being disparities associated with sexual and gender identities. Generally, bisexual, queer, and non-binary/genderqueer individuals tended to experience the greatest well-being disadvantages relative to their cisgender and heterosexual counterparts as well as many of their SGM counterparts. Remarkably, objective indicators of SES, union status, and whether respondents had residential children did not explain most of these associations. This study makes notable strides in increasing our knowledge of SGM well-being in the U.S. today, and we discuss its contributions and implications below.

Sexuality and Well-Being

In terms of sexuality, past studies show disadvantages for sexual minority individuals on one or two measures of physical health such as self-rated health (Reczek et al. 2017), functional limitations (Hsieh and Liu 2019), or financial well-being such as wages (Mize 2016). Our results support previous research but also widen the scope of known SGM well-being disadvantages (Meyer 2003; Williams and Mann 2017). After accounting for covariates, gays and lesbians showed well-being detriments only on physical and mental health and financial well-being, relative to heterosexuals. Those findings align with research on self-rated health, functional limitations, and psychological distress (Meyer 2003; Williams and Mann 2017), and wages (Badgett 1995; Mize 2016) and elevated poverty rates (Badgett et al. 2019). Accounting for SES, union status, and the presence of residential children explained life purpose and social connectedness disadvantages for gays and lesbians, implying that these characteristics play a part in driving these disparities. In this sense, it is important to continue striving for socioeconomic equality and toward a society that does not differentially confer status to some family forms more than others (see Mize 2016), as doing so might continue to narrow the well-being gaps that we observed by decreasing exposure to distal and proximal stressors that are inversely related to health and well-being.

Bisexuals faced disadvantages on each well-being index relative to heterosexuals, and in some cases gays and lesbians, after adjusting for all covariates. Minority stressors might explain those findings, as the conditions of heterosexism and heteronormativity in the U.S. may undermine the well-being of bisexuals in unique ways relative to the detriments gays and lesbians experience. Experiences of biphobia, the “double discrimination” bisexuals experience from both heterosexual and lesbian and gay communities (Ochs 1996), greatly impact the well-being of bisexuals in diverse arenas of social life (Mulick and Wright 2002). Further, queer-identified people in our data are in a similar position of relative disadvantage to heterosexuals, save for life purpose. Although those who identified as more than one sexual identity category are likely a heterogenous group, disadvantages were quite pronounced and even paralleled disadvantages experienced by queer people.

Taken together, living outside of the heterosexual/homosexual binary is associated with worse well-being that might be explained by relatively acute minority stressors, as is the case for those who are bisexual, queer, or identify with more than one sexual identity. This minority stress might materialize due to harsher stereotypes (Herek 2002), more negative attitudes (Yost and Thomas 2012), or heightened erasure and invisibility (Yoshino 1999) applied to bisexual and potentially queer people relative to gay and lesbian populations. Or perhaps the essentialist “born this way” discourse benefitted gays and lesbians while largely leaving behind more marginalized sexual minorities (see Mize 2016). People who identify as queer, bisexual, and those who identify as more than one sexual identity might experience stressors of increased magnitude (Meyer et al. 2021), or in more harmful ways, undermining health and well-being in ways that diverge from heterosexual, gay, and lesbian populations.

Surprisingly, same-gender loving individuals were relatively advantaged on most dimensions of well-being relative to heterosexuals and many sexual minorities. The term same-gender loving tends to be a “culturally affirming alternative” relative to other terms (Lassiter 2014), such as “men who have sex with men,” which Black sexual minority men describe as dehumanizing (Truong et al. 2016). The use of and identification processes with the term same-gender loving understandably involve some selection effects, in that those who identify with the term knowing its history likely have achieved higher levels of self-acceptance—sexually and racially—relative to other sexual minorities of color. Black same-gender loving men are likelier to think that homophobia is a problem within communities of color compared to gay and bisexual Black men and report higher levels of connectedness to the LGBT community compared to bisexual Black men (Keene et al. 2021). For these reasons, same-gender loving individuals might exhibit lower levels of internalized racism and queerphobia, leading to relatively better health and well-being (Gale et al. 2020; James 2020; Meyer 2003). For White respondents, for whom the term was not meant but who chose this identity category anyway, these findings are more difficult to interpret. Diffusion of the term into White sexual minority communities offers one explanation; identification with the action-oriented “same-gender loving” and a misunderstanding of the broader context of the term’s origins offers another. In any case, more evidence is needed to fully understand the advantages we have observed.

One key theme of our findings is that financial well-being constitutes a key axis of disadvantage for nearly all sexual minorities, the index that was most prominently stratified by sexual identity. Remarkably, accounting for objective measures of SES—employment status, income, and education—did not fully explain disparities in financial well-being for gays and lesbians, bisexuals, queer people, and those who identified as more than one sexual identity relative to heterosexuals, suggesting that other factors help explain subjective financial well-being detriments. As the financial well-being index includes measures of food insecurity (Gundersen and Ziliak 2015), relative satisfaction with standard of living (Ringen 1981), and worrying about making ends meet (Cooper 2014), the presence of more heterogenous class interactions among sexual minorities might lead sexual minorities to create reference categories from higher-SES sexual minorities. In that sense, relative deprivation might play a larger role among sexual minorities than heterosexuals (Crosby 1976), explaining why objective SES measures do not account for disadvantages in subjective financial well-being. While future work is needed to fully understand the causes of these disparities, our results show that the average financial well-being of sexual minorities pales in comparison to heterosexuals.

Gender and Well-Being

Our findings suggest that non-binary/genderqueer populations face the strongest well-being disadvantages compared to cisgender people, and in some cases relative to other gender minorities. Non-binary/genderqueer people faced pronounced disparities in community belonging, physical and mental health, and social connectedness. Recent population-level research shows that gender nonconforming individuals experience the greatest detriments in self-rated health relative to cisgender and transgender populations (Lagos 2018). While some non-binary/genderqueer people might also identify as gender nonconforming, and vice versa, the two populations might differ from one another to no small degree—but both appear to live outside of the gender binary. In this way, our study is one of the first to examine population-level non-binary/genderqueer well-being. Our findings align with those of Lagos (2018), and build on past work by illuminating that disparities persist on comprehensive health indices and extend to other dimensions of well-being.

Transgender men and transgender women experience many bivariate disadvantages relative to cisgender men and cisgender women, but sociodemographic characteristics explained many disparities. That may unfortunately be explained by very small sample sizes, which render only stark differences or differences with low variance detectable. We urge caution in interpreting the results to mean transgender men and transgender women face negligible disadvantages relative to cisgender people. Given the magnitude of the bivariate disadvantages, the regression results may reflect an artifact of sample size rather than a genuine finding of no difference.

Limitations and Conclusions

Several limitations to this study warrant consideration. First, sexuality is comprised of three distinct components: sexual identity, sexual attraction, and sexual behavior (see Mishel 2019; Mize 2016; Westbrook et al. forthcoming). Similarly multiple dimensions combine to create gender, such as identity and expression, and still gender is interpreted in various ways by social actors, all of which affect health and well-being (see Hart et al. 2019; Lagos 2019). Our data only reflect sexual and gender identities, precluding us from analyzing other aspects of sexuality or gender which might show different associations with well-being. For instance, those who identify as straight but engage in same-sex behavior might experience their communities or workplaces differently and their communities and workplaces might react to them differently, affecting their well-being scores. Second, the cross-sectional data do not permit causal claims, and we are unable to address issues of reverse causality. An individual’s community or their financial well-being, for example, might provide one with the social and economic resources to realize that they are indeed bisexual or transgender. Finally, the sample of non-binary/genderqueer people included only those who also identified as transgender. Those who identify as non-binary/genderqueer and transgender might differ considerably from those who identify as only non-binary/genderqueer. Considerable ambivalence exists among non-binary people about identifying as transgender, with some not feeling “trans enough,” citing concerns about not suffering sufficiently or not undergoing hormonal therapy or surgery (Darwin 2021). Well-being disparities for this group, then, might likely exceed those relative to those non-binary/genderqueer people who do not also identify as transgender.

Future work should keep these limitations in mind and attempt to build on the present study. Important next steps include directly examining the associations of both sexual and gender minority stress on well-being. Such research could also highlight stress proliferation at the intersection of sexual and gender minority stress. Additionally, research could test whether well-being indices mediate SGM health disparities (Liu and Reczek 2021; Timmins et al. 2017). All of those endeavors would help extend research on SGM well-being and MST to more holistically examine health and well-being.

Our study builds on previous work by examining associations between sexual and gender identities and five dimensions of well-being: (1) life purpose; (2) community belonging; (3) physical and mental health; (4) financial well-being; and (5) social connectedness. In so doing, we provide a more holistic profile of SGM well-being at the population level, reflecting a wide range of measures that encapsulate people’s everyday experience of reality. Decades of research on disadvantages in health and well-being by race, class, and gender exist in demographic work, but demographers have been slower to incorporate sexuality and non-dichotomous measures of gender (Schnabel 2018; Westbrook and Saperstein 2015). A lack of available data that includes informative measures of sex, gender, and sexuality often precludes SGM inclusion (Compton 2018). For this reason, we echo others in encouraging improved measures to better understand how sex, gender, and sexuality are associated with and pattern inequality (for important suggestions see Lagos and Compton 2021; Saperstein and Westbrook 2021; Westbrook et al. forthcoming). As evidence of the deficit in understanding created by the dearth of SGM inclusion, our results show marked associations between sexuality and gender identities and well-being, even after adjusting for sociodemographic and socioeconomic covariates. Taken together, these results echo and bolster suggestions of other scholars to pay more attention to sexuality and a more complex form of gender (Schnabel 2018), as both show important associations with well-being. Most importantly, our approach shows more ubiquitous SGM well-being disparities across five important dimensions than previous research using single measures suggests, highlighting the necessity of more holistic profiles of well-being.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by the Institute for Population Research at the Ohio State University and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health through center grant P2CHD058484. For thought-provoking questions and insightful comments, we thank Trent Mize and participants of the Sexual and Gender Minority Populations session at the 2021 Population Association of America annual meeting where an earlier version of this paper was presented. We are also indebted to Jake Hays and Natasha Quadlin, without whom our figures would not be nearly as colorful or as illustrative. Finally, we want to acknowledge and thank the three anonymous reviewers, the deputy editor, and Mark Hayward, all of whose feedback improved our work considerably.

Footnotes

When we refer to community belonging in this paper, we are referring to residence-based communities (i.e., neighborhood community). Many sexual and gender minorities might be involved in communities outside their residential community, but we are most concerned with well-being in terms of residence-based communities since where respondents live and spend most of their time is paramount in our conceptualization of well-being.

We use queerphobia as an umbrella term to broadly refer to internalized homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia as it relates all SGM individuals.

“Same-gender loving” was coined by Cleo Manago, a Black activist, in the early 1990s. Viewing mainstream terms for sexual minorities, such as lesbian and gay, through the lens of whiteness, Manago sought to create a term that was decidedly Afrocentric. Descriptive results show that those who identify as same-gender loving are disproportionately people of color (37.33%), many of whom are Black, even though a sizeable portion identified racially as White (62.67%).

We collapse lesbian and gay into one category for both theoretical and methodological reasons. Theoretically, both lesbian and gay individuals are reporting an identity predicated on same-sex attraction or behavior and both terms imply something about the gender of the person claiming the identity and the gender of the person to whom one is attracted and/or with whom one engages in sexual behavior. Methodologically, only 3.6% of gay individuals identified as cisgender women or transgender women, while only 1.7% of lesbian individuals identified as cisgender men or transgender men. Therefore, we collapse these categories to avoid inadvertently modeling interaction associations between sexual identity and gender identity for lesbian and gay populations regarding the predicting of our outcome variables.

Those who identified as exclusively lesbian and gay were categorized as belonging to the collapsed lesbian/gay category.

Unlike the sexuality measure, the gender measure does not allow an individual to choose more than one gender. The three-part gender question’s phrasing is an improvement on past binary gender measurements, but is also limited in that implies that those who are men or women are not transgender and vice versa (see Westbrook and Saperstein 2015) and that it relies on anachronistic terms to describe transgender individuals (e.g., “Male-to-female”).

Those coded as “Other” in the race/ethnicity variable identified as either “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander” or identified as more than one racial category. These groups were combined and collapsed into one category of the variable due to small sample sizes and for ease of interpretation.

While it is also reasonable to expect that those who did not specify their race/ethnicity are different from those who did, we imputed missing information on race/ethnicity because we are chiefly interested in associations of sexual identity and gender identity on well-being. Moreover, only a small portion (less than 1%) left their race/ethnicity blank, which is unlikely to substantially alter results, especially compared to sexual identity where more than a tenth of the data are missing. Finally, because our listwise deleted regression results are nearly identical to our multiply imputed results, this suggests that we can impute data on our missing covariates without sacrificing accuracy.

Contributor Information

Lawrence Stacey, Department of Sociology, Ohio State University.

Rin Reczek, Department of Sociology, Ohio State University.

R Spiker, Independent Scholar.

References

- Amroussia N, Gustafsson PE, & Pearson JL (2020). Do inequalities add up? Intersectional inequalities in smoking by sexual orientation and education among US adults. Preventive Medicine Reports, 17, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett ML (1995). The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48(4), 726–739. [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MVL, Choi SK, & Wilson BDH (2019). LGBT poverty in the United States: A study of differences between sexual orientation and gender identity groups. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, University of California. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/content/qt37b617z8/qt37b617z8.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Baumle AK, & Poston DL Jr (2011). The economic cost of homosexuality: Multilevel analyses. Social Forces, 89(3), 1005–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, & Taylor L (2000). Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: Evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography, 37(2), 139–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DA, Makar HR, Sanders SG, & Taylor LJ (2003). The earnings effects of sexual orientation. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 56(3), 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U, Miao X, Linkletter C, & Clark MA (2012). Adult health behaviors over the life course by sexual orientation. American Journal of Public Health, 102(2), 292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VR (1981). Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CS, Eppink ST, & Gonzales G (2020). Transgender status, gender identity, and socioeconomic outcomes in the United States. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 73(3), 573–599. [Google Scholar]

- Chai L, & Maroto M (2020). Economic insecurity among gay and bisexual men: Evidence from the 1991–2016 US General Social Survey. Sociological Perspectives, 63(1), 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Clouston SA, & Link BG (2021). A Retrospective on Fundamental Cause Theory: State of the Literature and Goals for the Future. Annual Review of Sociology, 47(1), 131–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M (2014). Cut adrift: Families in insecure times. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Compton D (2018). How many (queer) case do I need? Thinking through research design. In Compton D, Meadow T, & Schilt K (Eds.), Other, please specify: Queer methods in sociology (pp. 185–201). Oakland: Univeristy of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby FJ (1976). A model of egoistical relative deprivation. Psychological Review, 83(2), 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, Joestl SS, & Ward BW (2016). Barriers to health care among adults identifying as sexual minorities: A US national study. American Journal of Public Health, 106(6), 1116–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin H (2020). Challenging the cisgender/transgender binary: Nonbinary people and the transgender label. Gender & Society, 34(3), 357–380. [Google Scholar]

- Denier N, & Waite S (2019). Sexual orientation at work: Documenting and understanding wage inequality. Sociology Compass, 13(4), e12667. [Google Scholar]

- DiPlacido J (1998). Minority stress among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: A consequence of heterosexism, homophobia, and stigmatization. In Herek GM (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation: Vol 4. Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 138–159). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MJ (2022). Social exclusion and resilience: Examining social network stratification among people in same-sex and different-sex relationships. Social Forces, 100(3), 1284–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Shui C, & Bryan AE (2017). Chronic health conditions and key health indicators among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older US adults, 2013–2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107(8), 1332–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale MM, Pieterse AL, Lee DL, Huynh K, Powell S, & Kirkinis K (2020). A meta-analysis of the relationship between internalized racial oppression and health-related outcomes. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(4), 498–525. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison S (2018) On the limits of “trans enough”: Authenticating trans identity narratives. Gender & Society, 32(5), 613–637. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziani A (2015). There goes the gayborhood? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales G, & Henning-Smith C (2017). The Affordable Care Act and health insurance coverage for lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Analysis of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. LGBT Health, 4(1), 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales G, Przedworski J, & Henning-Smith C (2016). Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the United States: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(9), 1344–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granberg M, Andersson PA, & Ahmed A (2020). Hiring discrimination against transgender people: Evidence from a field experiment. Labour Economics, 65, 101860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen C, & Ziliak JP (2015). Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Affairs, 34(11), 1830–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CG, Saperstein A, Magliozzi D, & Westbrook L (2019). Gender and health: Beyond binary categorical measurement. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 60(1), 101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith C, & Gonzales G (2018). Differences by sexual orientation in perceptions of neighborhood cohesion: Implications for health. Journal of Community Health, 43(3), 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2002). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. Journal of Sex Research, 39(4), 264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, & Berrill KT (1992). Hate crimes: Confronting violence against lesbians and gay men. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N, & Liu H (2021). Social relationships and loneliness in late adulthood: Disparities by sexual orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83, 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N, & Liu H (2019). Bisexuality, union status, and gender composition of the couple: reexamining marital advantage in health. Demography, 56(5), 1791–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N, & Shuster SM (2021). Health and Health Care of Sexual and Gender Minorities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 62(3), 318–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, & Benyamini Y (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D (2020). Health and health-related correlates of internalized racism among racial/ethnic minorities: A review of the literature. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7, 785–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, & Anafi MA (2016). Executive summary of the report of the 2015 US transgender survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]