Abstract

In the search of the antigenic determinants of a 65-kDa mannoprotein (MP65) of Candida albicans, tryptic fragments of immunoaffinity-purified MP65 preparations were tested for their ability to induce lymphoproliferation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Five major peptides (T1 to T5) were shown to induce a vigorous proliferation of PBMC from the majority of the eight healthy human subjects tested. With the use of synthetic peptides, critical amino acid sequences of the two most immunoactive (T1 and T2) peptides were determined. Similar to what was found for the MP65 molecule, no PBMC multiplication was induced by the antigenic peptides in cultures of naive cord blood cells. The amino acid sequence analysis of tryptic and chymotryptic peptides of MP65 demonstrated a substantial homology with the deduced sequences of two cell wall proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encoded by the genes YRM305C and YGR279C. However, the antigenic peptides were those showing the least similarity with the corresponding regions of the above proteins. In particular, the lymphoproliferation-inducing sequence of the T1 peptide scored only 20% identity with the homologous regions of S. cerevisiae proteins. Besides disclosing the amino acid sequence of MP65, this study provides an initial characterization of some of its antigenic determinants, as well as of synthetic peptides of potential use to detect specific immune responses against MP65, a major target of anticandidal cell-mediated immunity in humans.

Yeasts belonging to the genus Candida are major fungal pathogens for the immunocompromised host. Candida albicans is especially prevalent in subjects infected by the human immunodeficiency virus with severe functional and numerical deficits in CD4+ T lymphocytes, which are critical components of cell-mediated immunity (CMI) (24). Despite the increased awareness of the important role that CMI plays in the defense against this fungal pathogen (reviewed in references 1 and 38), very few CMI antigen targets for it have so far been identified. These include heat shock proteins, enolase, and a number of as yet uncharacterized mannoproteins, some with adhesin function (6, 12, 15, 27, 29, 30, 40).

We have long been studying a 65-kDa mannoprotein (designated MP65) which is present in both the structural and secretory mannoprotein material and which is recognized by T cells of peripheral blood of practically all healthy individuals (quasiuniversal antigen) (20, 42–44). In mice immunized with whole fungal cells or MP65-rich mannoprotein extract (MP-F2) (44), a vigorous lymphoproliferative response with a prevalent T-helper type 1 (Th1) cytokine pattern was elicited in in vitro MP65-stimulated lymphomonocyte cultures (31). In addition, the MP-F2 extract was capable of inducing a moderate but significant degree of protection against a challenge with a highly virulent C. albicans strain in a model of murine disseminated candidiasis. This protection was significantly increased by coadministration of interleukin-12 (IL-12) or by treatment with antibodies against IL-10 (32, 33).

Thus, MP65 contains Th1-inducing and potentially protective T-cell epitopes, and its further biochemical and immunological characterization could be extremely useful for devising an immunotherapeutic or vaccination strategy. With this aim in mind, we have sequenced a large number of peptides obtained by enzymatic digestion of a immunoaffinity-purified antigen. This sequencing revealed that MP65 of C. albicans, while bearing substantial homology to the products of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene family encoding putative glucanase enzymes (10), also possesses rather distinctive antigenic determinants in the N-terminal region of the protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

C. albicans BP, serotype A, from the established stock collection of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità, was used throughout this study. Its origin and culture maintenance have been described elsewhere (44). It was grown in Winge broth (0.2% glucose, 0.3% yeast extract; Difco) or modified Lee's medium (28) buffered in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, as specified for single experiments.

Sera and MAbs.

7H6 is a mouse immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b) monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific for a peptide epitope of MP65. MAb 4H12 is a mouse IgG2a specific for the protein moiety of a 70-kDa mannoprotein of C. albicans (20). Both MAbs were prepared by fusion of the myeloma cell line X63-Ag8.653 with splenocytes of mice immunized with a secreted mannoprotein material from hyphal cell cultures of C. albicans and purified as described in detail elsewhere (20). Polyclonal anti-MP65 antibodies were raised in 2-month-old, female BALB/c mice (Charles River, Calco, Italy) by immunization with the purified MP65 coupled to concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.)-agarose beads, as follows. Thirty micrograms (polysaccharide) of MP65 was incubated with 150 μg of ConA (12 mg of ConA per ml; Sigma) in 100 μl of buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.5) for 1 h at 25°C; the mixture was brought to 1 ml with double-distilled H2O and emulsified into an equal volume of complete Freund's adjuvant. Two doses (200 μl) of this preparation were administered intraperitoneally to four previously pristanized mice (0.5 ml of pristane given up to 2 weeks before) at an 8-week interval. Five weeks later, mice received a third dose of 8 μg of the soluble MP65 in incomplete Freund's adjuvant. Ascites developed after the second or third injection, and ascites fluid was collected and tested in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (20).

MP65 purification.

The MP65 was affinity purified from the material spontaneously released from C. albicans mycelial cultures, as previously reported (20). Briefly, the fungus was grown in Lee's medium with 1 μg of tunicamycin/ml for 24 h at 37°C. The culture supernatant was concentrated and dialyzed by ultrafiltration (Diaflow Ultrafilter YM10; Amicon Corp., Danvers, Mass.) and passed through two sequential affinity columns which were prepared by covalently coupling MAb 7H6 or MAb 4H12 to protein A-Sepharose CL4B (Pharmacia) with dimethylpimelimidate (Sigma). The first (MAb 4H12) column was used to minimize nonspecific binding of material from the mycelial secretion to the MP65-specific MAb 7H6 column. MP65 was eluted from the second (MAb 7H6) column with 100 mM triethylamine, pH 11.5, neutralized with 2 M Tris, dialyzed against double-distilled H2O, and kept at −20°C. The purified antigen was substantially free from other mannoproteins or proteins, as assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), silver staining, ConA detection, and immunoblotting with MAbs or polyclonal antibodies directed against other components of the mycelial secretion (16).

Total polysaccharide and protein compositions of MP65 were determined by the phenol-sulfuric acid method (18) and the Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) protein assay, respectively.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (immunoblotting).

Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with 5 to 15 or 5 to 20% gradient acrylamide slab gels with a 3.5% acrylamide stacking gel (25, 27). After electrophoresis, samples were either stained with the Bio-Rad silver stain kit or transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose (0.1- or 0.2-μm pore size) or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) for detection with ConA, MAbs, or polyclonal antibodies or for amino acid sequencing, as previously described (7, 20).

Enzyme treatments.

For limited proteolysis, 10 μg of denatured MP65 (0.1% SDS, 100°C, 5 min) was resuspended in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0, and digested with trypsin (Sigma Chemical Co.) (enzyme/substrate ratio, 1:10 or 1:50) or chymotrypsin (enzyme/substrate ratio, 1:100) for 1 h at 37°C. For extensive proteolysis with trypsin or chymotrypsin, 400 μg of heat-denatured (100°C, 5 min) MP65 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, was treated with the corresponding enzyme (enzyme/substrate ratio, 1:10) for 2 to 5 h at 37°C. Cleavage with endoproteinase Asp-N (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) (enzyme/substrate ratio, 1:50) was carried out (under the same conditions) in the presence of 8% acetonitrile. The extent of digestion was assessed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation.

The peptide mixtures obtained following the enzymatic digestions with trypsin (T peptides) or chymotrypsin (CH peptides) were purified using the Beckman Gold chromatography system on a macroporous reversed-phase column (Acquapore RP-300; 4.6 by 250 mm, 7 μm; Brownlee Labs, Foster City, Calif.). Peptides were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 70% acetonitrile in 0.2% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid, at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The elution was monitored using a diode array detector (Beckman; model 168) at 220 and 280 nm. Peptides represented by peaks were collected, lyophilized, and finally resuspended in 200 μl of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Oxoid).

Amino acid sequencing.

The peptides obtained by limited proteolysis were separated in a 15 to 20% acrylamide gradient gel and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After being stained with 0.1% Coomassie blue in 50% methanol and destained with 50% methanol, visualized bands were excised and subjected to automated Edman degradation on a gas phase sequencer (model AB 476A; Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) (15). HPLC-purified peptides were spotted (20 μl) in PVDF membranes before sequencing. In some cases, the peptides were covalently linked to the membrane (Sequelon AA membranes, Millipore) to avoid its detachment throughout sequencing cycles (31).

Synthetic peptides.

Synthetic peptides were purchased from Tana Laboratories, Houston, Tex.). They were provided as >80% pure and were further assessed for purity by HPLC amino acid analysis and sequencing, as described above. Because of their high hydrophobicity, they were dissolved in 5% dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma) at a concentration of 1 mg/20 μl and then diluted to the desired concentration in RPMI 1640 medium. DMSO controls demonstrated that the concentrations used for peptide solubilization did not affect peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proliferation.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay.

Lymphoproliferation assays were performed as previously reported (2, 3, 44). Briefly, PBMC from venous blood samples of healthy human donors were isolated by centrifugation on a density gradient (Lymphoprep; Nyegaard, Oslo, Norway) and cultured at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere in RPMI 1640 medium–5% pooled AB human serum (Sigma) in 96-microwell trays (106 cells per ml, 200 μl per well) in the presence of various doses of the stimulant and controls, as indicated in each single experiment. Peptides isolated by HPLC were resuspended in Dulbecco's PBS, heat inactivated (80°C, 10 min) as specified before, filtered, and used at 1:100 or 1:1,000 (final dilution). In some experiments, antigen-unresponsive PBMC from umbilical cord blood were used as responder cells. Cell proliferation was measured on day 7 of the culture by [3H]thymidine incorporation and expressed as counts per minute per 2 × 105 cells (mean ± standard deviation of triplicate wells) and by stimulation index (SI; test counts per minute divided by control counts per minute for the PBMC culture without stimulant). SI > 3 was considered to indicate a positive lymphoproliferation.

RESULTS

MP65 purification.

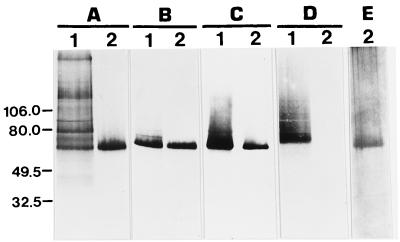

The MP65 was purified from protein-enriched secretory mannoprotein from hyphal cells of C. albicans by double sequential immunoaffinity chromatography. To this end, two MAbs, one of which (MAb 4H12) adsorbed an abundant 70-kDa molecule and other irrelevant mannoproteins of the secretory material and the other of which (MAb 7H6) bound specifically the MP65 constituent, were used. As shown in Fig. 1, the purified antigen intensely reacted with specific reagents and was substantially free from other mannoproteins or proteins, as assessed by silver staining, measurement of ConA reactivity, and immunoblotting with MAb 4H12 directed against the 70-kDa mannoprotein-rich material. This purification procedure was reproduced with similar efficiencies for all four batches of MP65 used throughout our experiments. The immunoaffinity-purified MP65 did not contain Limulus amoebocyte lysate-detectable lipopolysaccharide (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Chemical and immunochemical detection of immunoaffinity-purified MP65. (A) ConA stain; (B to D) immunoreactivity with MAb 7H6 (B), anti-MP65 mouse serum (C), and MAb 4H12 (D); (E) silver stain. Lanes 1, secretory mannoprotein material from tunicamycin-treated mycelial cultures of C. albicans used as starting material for the immunoaffinity purification of MP65, for which 2 μg of polysaccharide material was reacted with ConA and 10 μg was reacted with each antibody preparation; lanes 2, 50 ng of purified MP65 was reacted with ConA, 100 ng was reacted with antibodies, and 1 μg was reacted with silver. Molecular mass markers (left) are in kilodaltons.

MP65 protease digestion and PBMC proliferation.

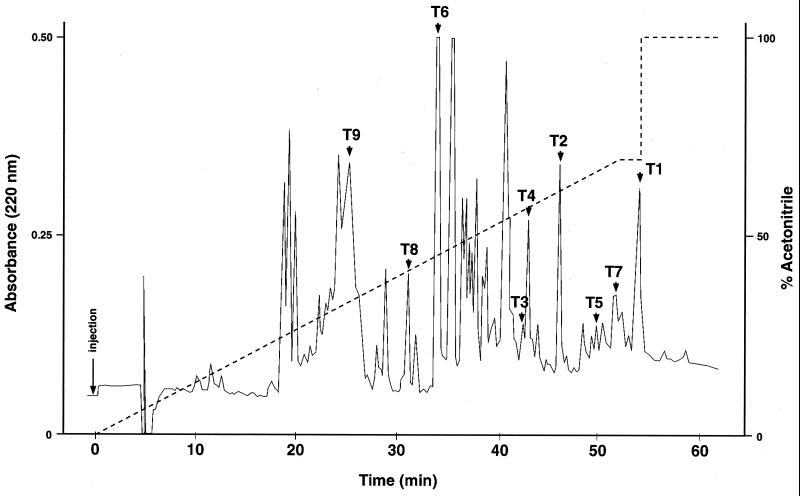

To identify enzymatic treatments useful to generate MP65 peptides with functional antigenic determinants, several preparations of the purified molecule were subjected to enzymatic digestion with trypsin or chymotrypsin or Asp-N endoproteinase and tested in a lymphoproliferation assay. Only the peptide mixture generated by trypsin cleavage had preserved the capacity of inducing a strong proliferation of PBMC from MP65-responsive donors in vitro (data not shown). Therefore, tryptic digestions of four different batches of MP65 were carried out, and the resulting main peptides obtained were separated by reversed-phase HPLC. The chromatographic profiles obtained in the four digestions were similar, but some minor differences in the number (from 40 to 45) or in the height of the main peptide peaks were seen. Figure 2 is a representative chromatogram of a trypsin digest of one of the four immunoaffinity-purified MP65 preparations.

FIG. 2.

HPLC separation of MP65 peptides obtained by complete proteolysis with trypsin. The chromatogram is one representative of four independent preparations. Arrows, peptides analyzed for amino acid sequence (T1 to T9); dashed line, gradient concentration.

PBMC from eight unrelated healthy blood donors were tested with all the HPLC-separated peptides, five of which (T1 to T5, at a dilution of 1:100) were found to induce proliferation of PBMC from at least one of the donors. At the above dilution, two peptides (T1 and T2) stimulated cell proliferation in all (T1) or the majority (T2) of PBMC donors, with proliferation indices falling in the same range as those achievable with MP65 and the polyclonal stimulant IL-2 (data not shown; see also below). No cell proliferation was induced by control buffers. On this basis, all the subsequent experiments of PBMC stimulation by antigenic MP65 fragments and synthetic peptides were carried out with the peptides T1 and T2 (see below).

The antigenic nature of the peptide-induced lymphoproliferative response, such as that previously shown for MP65 (20, 44), was confirmed by the inability of the relevant preparation to stimulate lymphoproliferation in cultures of mitogen-responsive, naive lymphocytes from the human umbilical cord blood (data not shown). Table 1 shows the actual lymphoproliferative responses of all eight donors whose PBMC were stimulated in vitro with peptides T1 and T2. Peptide T6 served as the negative control.

TABLE 1.

Lymphoproliferation induced by MP65 and some of the internal peptides separated from MP65 by HPLC of human PBMC cultures from adult healthy donors or umbilical cord blood

| Stimulator | Concentrationb | Lymphoproliferationa for PBMC donor:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| None | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | |

| IL-2 | 100 U/ml | 40.7 ± 6.1 | 21.0 ± 3.3 | 25.5 ± 3.8 | 22.4 ± 3.7 | NDc | 23.2 ± 2.1 | ND | 59.1 ± 3.0 |

| MP65 | 1 μg/ml | 30.7 ± 2.4 | 25.2 ± 1.7 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 23.8 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 21.9 ± 1.2 | 16.1 ± 1.3 | 30.6 ± 7.2 |

| 0.1 μg/ml | 16.5 ± 1.0 | 11.0 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 10.9 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 11.5 ± 1.6 | 10.4 ± 0.9 | 5.6 ± 3.3 | |

| T1 | 1:100 | 12.0 ± 1.8 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 0.7 | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 7.9 ± 5.0 | 10.5 ± 2.3 |

| 1:1,000 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 2.8 | |

| T2 | 1:100 | 16.5 ± 3.1 | ND | ND | 19.3 ± 3.9 | 10.7 ± 1.6 | 18.7 ± 0.7 | 10.7 ± 8.6 | 3.0 ± 0.3 |

| 1:1,000 | ND | ND | ND | 11.0 ± 2.5 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | |

| T6 | 1:25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| 1:100 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | |

| 1:1,000 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | |

| ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | |||

| Buffer | 1:25 | ND | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | ND | ND | ND | 0.9 ± 0.4 | ND |

| 1:100 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | ||||||||

Evaluated as [3H]thymidine incorporation and expressed as counts per minute (103) (mean ± standard deviation).

For MP65 internal peptides, fractions obtained by HPLC separation of 400 μg of trypsin-digested MP65 were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS and tested at the indicated final dilutions.

ND, not done.

Amino acid sequences of antigenic and nonantigenic peptides.

The amino acid sequences of the MP65 peptides were determined following total digestion with trypsin or chymotrypsin. In particular, the complete amino acid sequence of peptide T1 was determined after a further cleavage with chymotrypsin, HPLC separation, sequencing of the resulting peptides, and comparison with the amino acid composition of the whole, initial peptide from trypsin digestion. None of the main peptides examined had overlapping amino acid sequences, indicating that they were indeed distinct MP65 fragments (Table 2). The sequence of the T9 peptide corresponded to the previously reported N-terminal sequence (20).

TABLE 2.

N-terminal amino acid sequences of T-cell proliferation-inductive and -noninductive (control) peptides

| Peptide | Amino acid sequenceb |

|---|---|

| T1 | IFAGIFDVSSITSGIESLAEAVK |

| T2 | SSSQIASEIAQLSGFNVIR |

| T3 | LYGVDXX |

| T4 | XYGWDDIYTVSIGNELVNAGXA |

| T5 | Blockeda |

| T6 | YWGIYSN |

| T7 | XXXGXXAILFTAFNDLWK |

| T8 | XITYSPY |

| T9 | AVHVVX |

Chemical block at the N-terminal amino acid; no sequence could be determined.

X, unidentified amino acid.

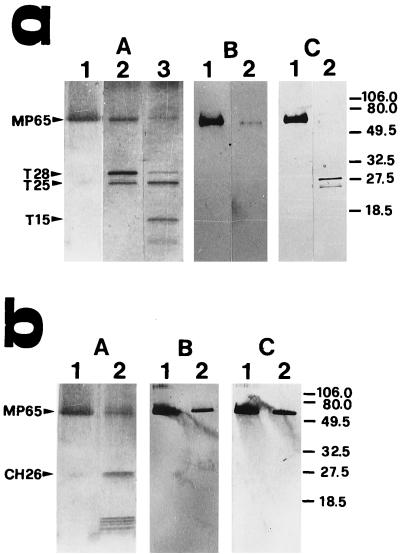

For the amino acid homology search, the peptides above and other MP65 fragments obtained by partial or complete cleavage with trypsin or chymotrypsin were sequenced and screened with database protein sequences. Following limited digestion with trypsin or chymotrypsin, several fragments ranging in apparent molecular mass from around 28 to less than 14 kDa were obtained (Fig. 3). Only fragments of trypsin digestion with molecular masses of 28, 25, and 15 kDa (T28, T25, and T15, respectively) as well as one from chymotrypsin digestion with a molecular mass of 26 kDa (CH26) were detected after electrophoretic transfer to a PVDF membrane and Coomassie blue staining. None of these large fragments reacted with ConA in Western blotting showing that they were minimally, if at all, glycosylated, and none was recognized by MAb 7H6 (Fig. 3). As shown in Table 3, the amino acid sequences of the 28- and 25-kDa tryptic fragments were similar and overlapped with the sequence of the 26-kDa chymotryptic fragment. Other overlappings with peptides generated by extensive proteolysis were seen; in particular, the 15- and 28-kDa tryptic fragments clearly contained the T1 and T2 peptides, respectively (compare with Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Analysis by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting of the MP65 fragments obtained by limited cleavage with trypsin (a) or chymotrypsin (b). Samples of MP65 (lanes 1 of both panels) were digested at an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:50 or 1:10 for trypsin (a, lanes 2 and 3, respectively) or 1:100 for chymotrypsin (b, lanes 2). Protein fragments were separated in 15 to 20% acrylamide gels and visualized with silver stain (A) or with ConA (B) (both panels) or anti-MP65 mouse serum (a, C) or MAb 7H6 (b, C) after electrophoretic transfer to PVDF membranes. Peptide fragments analyzed for amino acid sequence were CH26, T28, T25, and T15. Molecular mass markers (right) are in kilodaltons.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid sequences of major MP65 fragments from limited trypsin or chymotrypsin digestion or complete chymotrypsin digestion

| Treatment | Peptide | Amino acid sequenceb |

|---|---|---|

| Limited proteolysis | ||

| Trypsin | T28 | GIIYSPYSDNGGCKSSSQIASEIAQL |

| T25 | GMYSPYSa | |

| T15 | TSXQKIFAGIFDVSSITXGIEXLA | |

| Chymotrypsin | CH26 | XPYSDNGXXXK |

| Complete proteolysis with chymotrypsin | CH1 | TVSIGNEL |

| CH2 | TGPVVSVDTF | |

| CH3 | ITETGWPS |

The sequencing was arrested after the seventh amino acid.

X, unidentified amino acid.

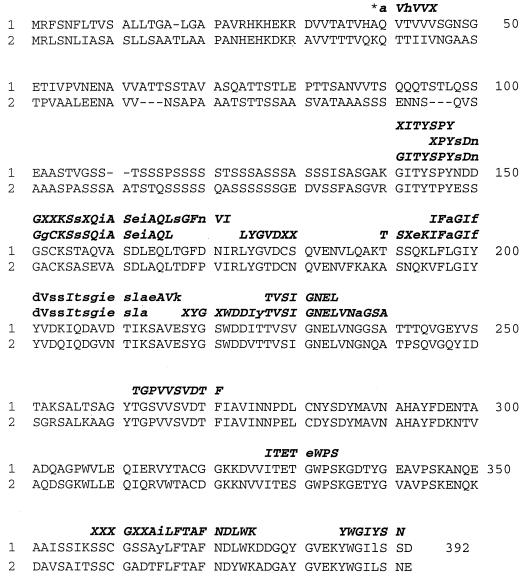

A search of protein databases revealed a high degree of similarity between the sequences of most of the MP65 peptides and the deduced amino acid sequences of two proteins encoded by the S. cerevisiae genes YRM305C and YGR279C. Figure 4 shows the sequences of these S. cerevisiae gene products aligned with the putative corresponding peptides of Candida MP65. The previously reported N terminus sequence of MP65 is also shown. Based on sequence comparison, the homology between the sequences of the MP65 peptides and the deduced amino acid sequences encoded by the S. cerevisiae genes is particularly high (up to 70% identity) in several regions of the C-terminal moiety of the protein. However, the identity score was much lower in the MP65 antigenic peptides, in particular for the T1 peptide (compare sequences of amino acids 195 to 217 of Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Alignment of C. albicans MP65 sequenced peptides (boldface) and the predicted amino acid sequences of S. cerevisiae YRM305C (sequence 1) and YGR279C (sequence 2) gene products as described by Cappellaro et al. (10). Lowercase letters were used when the MP65 amino acids were different from the corresponding amino acids of either of the S. cerevisiae proteins. The asterisk indicates the start of the N-terminal sequence of the mature MP65 protein.

Identification of T1 and T2 as putatively immunodominant MP65 sequences.

Since all (for T1) or most (for T2) of the subjects tested responded to the T1 and T2 peptides, we focused our attention on these two peptides as highly antigenic, putatively immunodominant determinants of MP65 (see above). To this end, the whole T1 and T2 peptides and two partially overlapping sequences (14 to 16 amino acids) of each of the two peptides were synthesized by using the sequence information derived from complete and incomplete MP65 enzymatic digestion (Tables 2 and 3) and used to stimulate in vitro PBMC from MP65- and natural T1- and T2-responsive donors. The whole T1 and T2 synthetic peptides were extremely hydrophobic and could hardly be dissolved at sufficient concentrations in PBS to be tested in lymphoproliferation assays. As shown in Table 4, the synthetic peptides possessing the last six and four C terminus amino acids of T1 and T2 peptides, respectively, induced lymphoproliferation in all four donors tested, although by magnitudes that differed greatly, as exemplified by both absolute counts per minute and proliferation indices. These data confirm that the recognition of the natural T1 and T2 peptides by PBMC was genuine and specific and did not depend upon contamination with other lymphoproliferation-inducing natural peptides with undefined amino acid sequences. They also indicate that the C terminus sequences ESLAEAVK and NVIR were critical components of T1 and T2 antigen recognition, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Synthetic peptides and induction of lymphoproliferation

| Peptide | Sequence | Lymphoproliferationa for PBMC donor:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| T1a | IFAGIFDVSSITSGI | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| T1b | SSITSGIESLAEAVK | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 44.5 ± 2.8 | 9.6 ± 2.0 |

| T2a | SSSQIASEIAQLSGF | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.5 |

| T2b | IASEIAQLSGFNVIR | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 26.9 ± 1.8 | 13.5 ± 2.7 |

| MP65b | 27.1 ± 2.4 | 13.1 ± 2.9 | 74.6 ± 5.2 | 8.4 ± 1.1 | |

| None | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | |

Evaluated as described in footnote a to Table 1. Each peptide was used at 1 to 10 μg/ml. The data (means ± standard deviations) shown are for 10 μg/ml.

Concentration, 10 μg/ml.

Biochemical properties of MP65, YRM305C, and YGR279C.

The two S. cerevisiae gene products and MP65 of C. albicans share a number of biochemical properties. They have acidic pI values and similar overall amino acid compositions, with high relative contents (>10% of the whole composition) of aspartic acid/asparagine, serine, glycine, alanine, and valine. The total content of hydroxy amino acids was particularly high (>20% of total amino acids) for all three proteins (Table 5). In S. cerevisiae protein sequences, around 50% of the hydroxy amino acids are located in the first (N-terminal) portion of the molecule, being particularly concentrated between residues 106 and 135 (Fig. 4). This suggests that most of the O glycosylation may occur in this area also in C. albicans MP65. One putative N glycosylation site was also identified in both S. cerevisiae deduced amino acid sequences, but no such a site was present in any of the MP65 sequenced peptides.

TABLE 5.

Comparison between the deduced amino acid compositions of the S. cerevisiae mature proteins encoded by YRM305C and YGR279C and that of C. albicans MP65a

| Amino acid residue | YRM305C

|

YGR279C

|

MP65b (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of residues | % | No. of residues | % | ||

| Asp/Asn | 38 (22/16) | 10.6 | 39 (19/20) | 11.0 | 9.8 |

| Thr | 38 | 10.6 | 29 | 8.2 | 6.8c |

| Ser | 61 | 16.7 | 53 | 14.9 | 15.1c |

| Glu/Gln | 33 (17/16) | 9.2 | 34 (17/17) | 9.6 | 3.9 |

| Pro | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 2.8 | 3.9 |

| Gly | 28 | 7.8 | 24 | 6.7 | 13.6 |

| Ala | 37 | 10.3 | 48 | 13.5 | 12.0 |

| Cys | 5 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.4 | NDd |

| Val | 38 | 10.6 | 36 | 10.1 | 11.3 |

| Met | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Ile | 15 | 4.2 | 15 | 4.2 | 5.2 |

| Leu | 15 | 4.2 | 12 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| Tyr | 16 | 4.4 | 15 | 4.2 | 3.2 |

| Phe | 6 | 1.7 | 8 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| His | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | Traces |

| Lys | 14 | 3.9 | 16 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Arg | 0.6 | 4 | 1.1 | 4.5 | |

| Trp | 1.4 | 6 | 1.7 | ND | |

See reference 20. For YRM305C, YGR279C, and MP65, the following values, respectively, were found: amino acid number, 360, 356, and unknown; pI, 4.54, 4.72, and 4.1; molecular mass by SDS-PAGE, 66, 66, and 65 kDa; molecular weight of the protein moiety, 40,448, 40,158, and unknown.

The amino acid analysis was performed with affinity-purified MP65 subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrophoretic transfer to PVDF membranes. The absolute numbers of amino acids in the whole molecule could not be determined since the molecular weight of the protein moiety remains unknown.

No correction for the destructive loss of Ser and Thr during hydrolysis was made.

ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, a 65-kDa mannoprotein (MP65), a major antigen target of anti-Candida CMI, has been dissected into a number of PBMC-stimulatory peptide fragments. At least two peptides have been found to contain major antigenic determinants of the fungus. They were seen to belong to a protein closely homologous to S. cerevisiae cell wall mannoproteins, designated by Cappellaro et al. (10) Scw4p and Scw10p and apparently encoded by the yeast genes YRM305C and YGR279C (20).

To our knowledge, MP65 is the first cell wall mannoprotein antigen of C. albicans that has been partially dissected into its antigenic determinants after molecular characterization and sequencing. There are several other mannoproteins of this fungus which approximate the molecular weight of the MP65 constituent, and some of them have been, in part, characterized at a molecular level. In general, they have usually been studied for adhesion to plastic or the cell surface or as receptors for soluble factors of host immunity rather than as CMI targets (4, 5, 8, 9, 19, 45, 46). A few of them have also been shown to be recognized as antigens. For instance, the C3d-binding protein (a doublet of 55 to 60 kDa and with a pI around 4) was antigenically expressed and it induced in vitro proliferation of splenocytes from Candida-infected mice (8). However, no precise identification of its antigenic determinants has been made, and the protein remains quite distinct from the MP65 antigen of C. albicans. Lack of biochemical characterization and sequence data for other MP-rich antigenic preparations of C. albicans precludes any sensible structural and functional comparison with our antigenic constituent (16, 17, 35).

Besides the remarkable technical difficulties in purifying (and sequencing) individual mannoproteins from polydispersed, highly glycosylated material, as previously discussed (11, 34), the paucity of data on the protein constituent of mannoproteins is also due to the fact that most research has been focused on saccharide determinants of the antibody response for serotyping and diagnostic purposes (39, 41). Consequently, a wealth of knowledge has been accumulated on α- and β-linked oligomannosides involved as B-cell epitopes, one of which has recently been shown to induce antibody-mediated protective immunity (21, 22). In contrast, the protein moieties of most mannoproteins remain rather mysterious, despite previous indirect evidence that their epitopes may constitute the target of such responses as delayed type hypersensitivity in vivo, ex vivo lymphoproliferation, and Th1 cytokine production (2, 3, 16, 17, 32), all critical elements of anti-Candida immunity (36, 38).

Amino acid sequence analysis of MP65 fragments obtained from partial or complete trypsin and chymotrypsin digestion revealed a substantial homology of this protein to products of a family of S. cerevisiae open reading frames (ORF), mostly YRM305C and YGR279C, recently identified by Cappellaro et al. (10) and shown to belong to a family of cell wall glucanases or transglycosidases. Among the sequenced MP65 peptides, those having the strongest homology to the deduced S. cerevisiae amino acid sequences were present in the C-terminal half of the molecule. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of fragments T28 and T25 and, mostly, the T1 fragment from the complete trypsin digestion showed the lowest degree of sequence homology with the S. cerevisiae gene products. All these sequences apparently belonged to the N-terminal half of the molecule. The two S. cerevisiae gene products show a high degree of potential O-glycosydic bonds, serine and threonine accounting for more than 20% of all amino acids. A long stretch of serine residues in positions 106 to 130 also characterizes the products of the two S. cerevisiae ORF. This region should be therefore considered as putatively involved in most of the MP65 O glycosylation. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that MP65 peptides obtained by limited proteolysis (T28, T25, T15, and CH26), while matching the corresponding S. cerevisiae regions (amino acid positions 146 and 144 of YRM305C and YGR279C, respectively) did not react with ConA in Western blotting (Fig. 3), nor did antigenic peptides T1 to T5 react with this lectin (as indicated in Fig. 2).

Other close resemblances between MP65 and the Scw10p and Scw4p of S. cerevisiae concern the nature of their cell walls and of their secretory mannoproteins and their release from the cell wall by reducing agents (10, 44). Although one site of potential N glycosylation (NXS or NXT) is present in both Scw10p and Scw4p, no such sites were identified in the putatively corresponding positions in any of the sequenced MP65 peptides. Previous studies showed that α-mannosidase and β-elimination, but not endoglycosidase, treatments affected the molecular mass of MP65 (20, 45). Moreover, the purified molecule was not reactive with any MAb recognizing common α- or β-mannan epitopes of a large variety of Candida mannoproteins (M. J. Gomez and A. Cassone, unpublished observations). It is possible that N glycosylation sites reside in other nonsequenced MP65 regions or that the protein is not N glycosylated, as happens for other cell wall mannoproteins (23).

Since MP65 is particularly abundant in the secretory mannoprotein material from the hyphal cells of C. albicans (44), its apparent homology with enzymes of the glucan metabolism would suggest a major function of it during mycelial growth, when the level of β-glucanase activity is high and dramatic rearrangements of cell wall structure and cell surface antigen modulations occur (14). However, no direct data on the biochemical function of MP65 are presently available.

A main purpose of the present study was the dissection of MP65 into its main antigenic determinants recognized by human PBMC. A number of tryptic or chymotryptic fragments were indeed separated by HPLC, their amino acid sequences were largely determined, and their abilities to induce PBMC proliferation in a number of subjects were tested. A more extensive testing with a high number of subjects and with various exact (molar) concentrations of each peptide could not be done as the amounts of peptide recovered from HPLC were low and the amount of MP65 itself achievable on a laboratory scale was not sufficiently high for complete chemical characterization of its trypsin digests. Moreover, the methods used could not guarantee that the antigenic peptides identified were totally sequenced, so as to exactly define their concentrations. Nonetheless, initial experiments with synthetic peptides provided direct evidence that at least two peptides (T1 and T2) contained genuine antigenic determinants and helped to more closely define the T1 and T2 regions representing or containing the epitope sequences. Interestingly, upon alignment of their sequences with the corresponding sequences of S. cerevisiae cell wall proteins, both peptides appeared to be localized in that portion of the molecule showing the least homology with the corresponding region of the yeast proteins. In fact, the immunoactive T1b peptide showed 80% sequence diversity compared to the corresponding S. cerevisiae region, whereas for the T2b peptide the diversity was >40%. The distinctiveness of what putatively contains major T-cell epitopes of MP65 might explain why mannoprotein extracts of S. cerevisiae, also containing MP65-like molecules, are substantially devoid of lymphoproliferation induction ability (A. Cassone, M. J. Gomex, and A. Torosantucci, unpublished data). In addition, the Scw10p and Scw4p sequences did not contain the lymphoproliferation-relevant epitope recognized by MAb 7H6 (20) that has recently been identified close to the N-terminal end of MP65 (C. Bromuro, R. La Valle, and A. Cassone, unpublished data).

It was previously shown that the MP65-containing MP-F2 fraction is recognized by human PBMC as a classical antigen rather than as a mitogen or a superantigen because its recognition requires antigen-presenting cells, is blocked by antibodies against class II histocompatibility antigens, and does not occur in naive cord-blood lymphocytes (2, 3, 26, 45). Although more studies with T-cell lines or clones are required for a full definition of the antigenic properties of MP65 peptides, including their recognition by T-cell epitopes, we have confirmed here that both T1 and T2 peptides are unable to stimulate naive cord blood lymphocytes to proliferate, thus possibly behaving as true antigens. A point of interest is also the low level or absence of glycosylation of these peptides, as shown by their inability to react with ConA. This suggests that the MP65 molecule is not uniformly glycosylated and that highly antigenic determinants of the human anti-Candida response have been selected among the least-glycosylated molecular regions of it. The immunoactivity of the synthetic peptides T1b and T2b supports this interpretation.

As discussed elsewhere (11, 12), MP65 is recognized by almost all healthy subjects that have so far been tested in our and other laboratories (overall totaling several hundred subjects). The T1 and T2 peptides studied here also induced lymphoproliferation in the great majority of the subjects examined, although the number of subjects was rather small. A mixture of well-defined MP65 peptides or a recombinant MP65 could therefore constitute a much more reliable reagent than those crude antigenic fractions used as recall antigens to assess the CMI response under various conditions, including the loss and recovery of CD4+ T-cell function in human immunodeficiency virus-positive subjects under therapy (13, 37). Crude antigenic fractions are indeed difficult to standardize and often produce unreliable results. The peptide sequences described here along with the recognized homology with the S. cerevisiae cell wall mannoproteins (10) will also facilitate the molecular cloning and the expression of a recombinant protein, a necessary step for a full evaluation of the immunogenicity and protective values of this immunodominant antigen of C. albicans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National AIDS Project, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Contract no. 50B/B.

The authors are grateful to Anna Botzios and Francesca Girolamo for help in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashman R B, Papadimitriou J M. Production and function of cytokines in natural and acquired immunity to Candida albicans infection. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:664–672. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.646-672.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausiello C M, Spagnoli G C, Boccanera M, Casalinuovo I, Malavasi F, Casciani C U, Cassone A. Proliferation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells induced by Candida albicans and its cell wall fractions. J Med Microbiol. 1986;22:195–202. doi: 10.1099/00222615-22-3-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausiello C M, Urbani F, Gessani S, Spagnoli G C, Gomez M J, Cassone A. Cytokine gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated by mannoprotein constituents from Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4105–4111. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4105-4111.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendel C M, St. Sauver J, Carlson S, Hostetter K. Epithelial adhesion in yeast species: correlation with surface expression of the integrin analog. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1660–1663. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchara J P, Tronchin G, Annaix V, Robert R, Senet J M. Laminin receptors on Candida albicans germ tubes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:48–54. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.48-54.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bromuro C, La Valle R, Sandini S, Urbani F, Ausiello C M, Morelli L, d'Ostiani C F, Romani L, Cassone A. A 70-kilodalton recombinant heat shock protein of Candida albicans is highly immunogenic and enhances systemic murine candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2154–2162. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2154-2162.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnette N. “Western blotting”: electrophoretic transfer of protein from dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calderone R, Enache E, Eskandri T, Wadsworth E, Sturtevant J. Adherence of Candida albicans to mammalian cells in vitro: nutritional influences. In: Suzuki S, Suzuki M, editors. Fungal cells in biodefense mechanism. Tokyo, Japan: Saikon Publishing Co., Ltd.; 1997. pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderone R A, Linehan L, Wadsworth E, Sandberg L. Identification of C3d receptors on Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1988;56:252–258. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.252-258.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappellaro C, Marsa V, Tanner W. New potential cell wall glucanases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their involvement in mating. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5030–5037. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5030-5037.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassone A. Mannoproteins of Candida albicans in host-parasite relationship. In: Suzuki S, Suzuki M, editors. Fungal cells in biodefense mechanism. Tokyo, Japan: Saikon Publishing Co., Ltd.; 1997. pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassone A, De Bernardis F, Ausiello C M, Gomez M J, Boccanera M, La Valle R, Torosantucci A. Immunogenic and protective Candida albicans constituents. Res Immunol. 1998;149:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cauda R, Tacconelli E, Tumbarello M, Morace G, De Bernardis F, Torosantucci A, Cassone A. Role of protease inhibitors in preventing recurrent oral candidosis in patients with HIV infections: a prospective case-control study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;21:20–25. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Bernardis F, Molinari A, Boccanera M, Stringaro A, Robert R, Senet J M, Arancia G, Cassone A. Modulation of cell surface-associated mannoprotein antigen expression in experimental candidal vaginitis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:509–519. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.509-519.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deepe G S., Jr Prospects for the development of fungal vaccines. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:585–596. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domer J E. Candida cell wall mannan: a polysaccharide with diverse immunologic properties. Crit Rev Immunol. 1989;17:33–51. doi: 10.3109/10408418909105721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domer J E, Li S, Wang Y, Lee S. Immunoregulatory studies with Candida albicans mannan. In: Suzuki S, Suzuki M, editors. Fungal cells in biodefense mechanism. Tokyo, Japan: Saikon Publishing Co., Ltd.; 1997. pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilmore B J, Retsinas E M, Lorenz J S, Hostetter M K. A C3d receptor on Candida albicans: structures, function and correlates for pathogenicity. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:38–41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez M J, Torosantucci A, Arancia S, Maras B, Parisi L, Cassone A. Purification and biochemical characterization of a 65-kilodalton mannoprotein (MP65), a main target of anti-Candida cell-mediated immune responses in humans. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2577–2584. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2577-2584.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Y, Cutler J E. Antibody response that protects against disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2714–2719. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2714-2719.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han Y, Kanbe T, Cherniak R, Cutler J E. Biochemical characterization of Candida albicans epitopes that can elicit protective and nonprotective antibodies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4100–4107. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4100-4107.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapteyn J C, Van Den Ende H, Klis F M. The contribution of cell wall proteins to the organization of the yeast cell wall. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1426:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein R S, Harris C A, Small C B, Moll B, Lesser M, Friedland G H. Oral candidiasis in high-risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.La Sala A, Urbani F, Torosantucci A, Cassone A, Ausiello C M. Mannoproteins from Candida albicans elicit a Th-type1 cytokine profile in human Candida specific long-term T cell cultures. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 1996;10:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.La Valle R, Bromuro C, Ranucci L, Muller H M, Crisanti A, Cassone A. Molecular cloning and expression of 70kDa heat shock protein of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4039–4045. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4039-4045.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee K L, Buckley H R, Campbell C C. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1975;13:148–153. doi: 10.1080/00362177585190271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathews R, Burnie J. The role of hsp90 in fungal infection. Immunol Today. 1992;13:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathews R, Smith D, Midgley J, Burnie J, Clark I, Conolly M, Gazzard B. Candida and AIDS: evidence for protective antibody. Lancet. 1988;ii:263–265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsudaira P. Limited N-terminal sequence analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:602–613. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mencacci A, Torosantucci A, Spaccapelo R, Romani L, Bistoni F, Cassone A. A mannoprotein constituent of Candida albicans that elicits different levels of delayed-type hypersensitivity, cytokine production, and anticandidal protection in mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5353–5360. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5353-5360.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mencacci A, Spaccapelo R, Del Sero G, Essle K H, Cassone A, Bistoni F, Romani L. CD4+ T-helper cell responses in mice with low-level Candida albicans infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4907–4914. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4907-4914.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson R D, Shibata N, Podzorski P R, Herror M J. Candida mannan: chemistry, suppression of cell-mediated immunity, and possible mechanisms of action. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:1–19. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson R D. Effects of Candida albicans mannans and mannan catabolites on human cell-mediated immune function in vitro. In: Suzuki S, Suzuki M, editors. Fungal cells in biodefense mechanism. Tokyo, Japan: Saikon Publishing Co., Ltd.; 1997. pp. 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puccetti P, Romani L, Bistoni F. A TH-1-TH-2-like switch in candidiasis: new perspectives for therapy. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88931-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinti I, Palma C, Guerra B C, Gomez M J, Torosantucci A, Cassone A. Proliferative and cytotoxic responses to mannoproteins of Candida albicans by peripheral blood lymphocytes of HIV-infected subjects. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;85:485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romani L, Howard D H. Mechanisms of resistance to fungal infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:517–523. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shibata N, Arai M, Haga E, Kikuchi T, Najima M, Satoh T, Kobayashi H, Suzuki S. Structural identification of an epitope of antigenic factor 5 in mannan of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4100–4110. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4100-4110.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundstrom P, Jensen J, Balish E. Humoral and cellular immune response to enolase after alimentary tract colonization or intravenous immunization with Candida albicans. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:390–395. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki S. Structural investigation of mannans of medically relevant Candida species. Determination of chemical structures of antigenic factors 1, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 13b. In: Suzuki S, Suzuki M, editors. Fungal cells in biodefense mechanism. Tokyo, Japan: Saikon Publishing Co., Ltd.; 1997. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torosantucci A, Palma C, Boccanera M, Ausiello C M, Spagnoli G C, Cassone A. Lymphoproliferation and cytotoxic responses of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells to mannoprotein constituents of Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:664–672. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-11-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torosantucci A, Gomez M J, Bromuro C, Casalinuovo J, Cassone A. Biochemical and antigenic characterization of mannoprotein constituents released from yeast and mycelial form of Candida albicans. J Med Vet Mycol. 1991;29:361–372. doi: 10.1080/02681219180000591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torosantucci A, Bromuro C, Gomez M J, Ausiello C M, Urbani F, Cassone A. Identification of a 65kDa mannoprotein as a main target of human cell-mediated immune response to Candida albicans. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:427–435. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tronchin G, Bouchara J P, Annaix V, Robert R, Senet J M. Fungal cell adhesion molecules in Candida albicans. Eur J Epidemiol. 1991;7:23–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00221338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu L, Lee K K, Ens K, Doig P C, Carpenter M R, Staddon W, Hodges R S, Paranchych W, Irvin R. Partial characterization of a Candida albicans fimbrial adhesin. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2834–2842. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2834-2842.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]