Abstract

ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels are multimeric protein complexes made of four inward rectifying potassium channel (Kir6.x) subunits and four ABC protein sulfonylurea receptor (SURx) subunits. Kir6.x subunits form the potassium ion conducting pore of the channel, and SURx functions to regulate Kir6.x. Kir6.x and SURx are uniquely dependent on each other for expression and function. In pancreatic β-cells, channels comprising SUR1 and Kir6.2 mediate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and are the targets of anti-diabetic sulfonylureas. Mutations in genes encoding SUR1 or Kir6.2 are linked to insulin secretion disorders, with loss- or gain-of-function mutations causing congenital hyperinsulinism or neonatal diabetes mellitus, respectively. Defects in the KATP channel in other tissues underlie human diseases of the cardiovascular and nervous systems. Key to understanding how channels are regulated by physiological and pharmacological ligands and how mutations disrupt channel assembly or gating to cause disease is the ability to observe structural changes associated with subunit interactions and ligand binding. While recent advances in the structural method of single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) offers direct visualization of channel structures, success of obtaining high-resolution structures is dependent on highly concentrated, homogeneous KATP channel particles. In this chapter, we describe a method for expressing KATP channels in mammalian cell culture, solubilizing the channel in detergent micelles and purifying KATP channels using an affinity tag to the SURx subunit for cryoEM structural studies.

1. Introduction

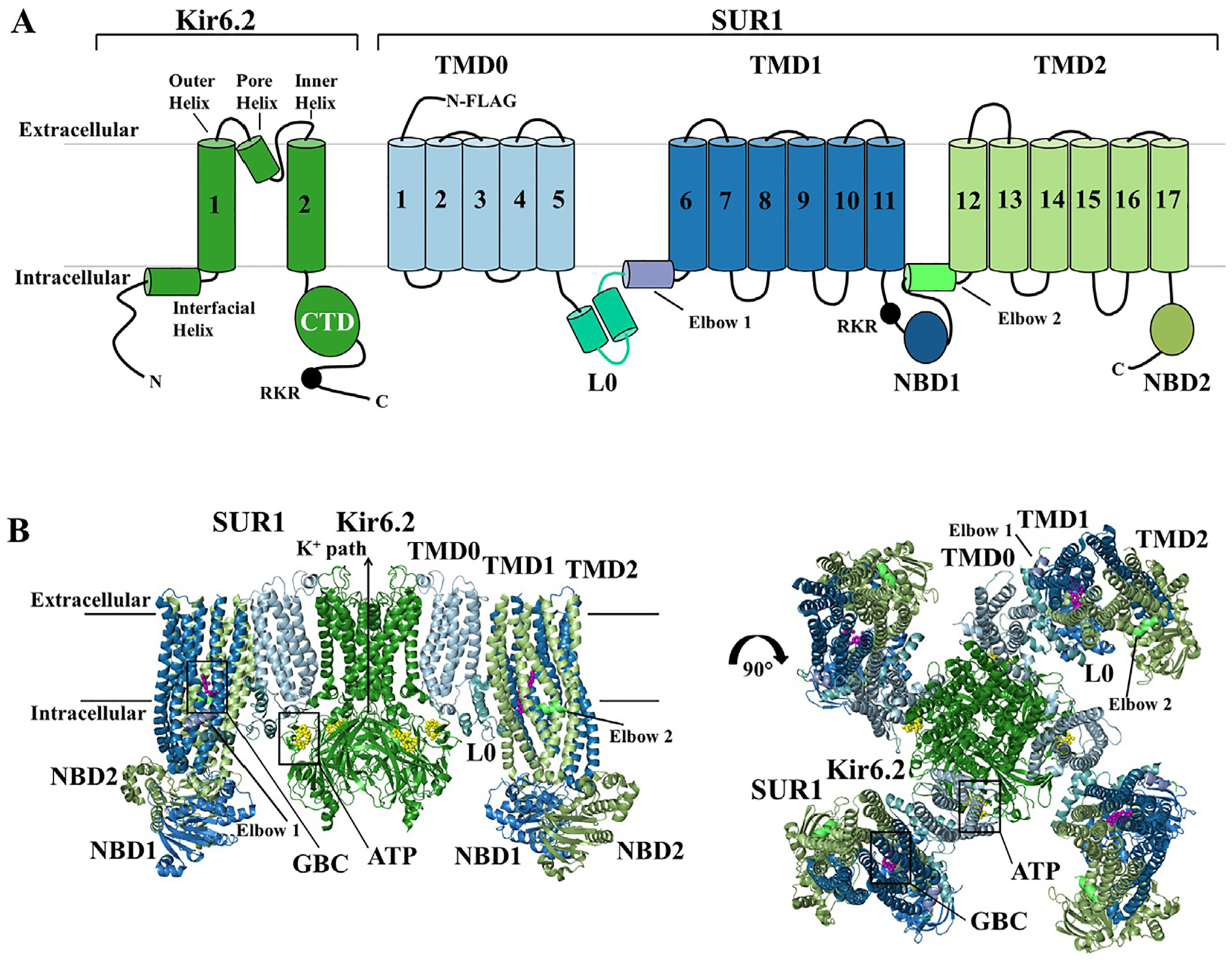

ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP) are a unique class of ion channels expressed in a variety of tissues including the pancreas, various regions of the brain, cardiac, skeletal, and vascular smooth muscle (Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1998). By regulating K+ flux at the plasma membrane in response to changes in intracellular ATP and ADP concentrations, KATP channels function as molecular sensors that couple cell metabolism to changes in membrane excitability (reviewed in, Nichols, 2006). KATP channels are made of four inward rectifying potassium channel (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2) subunits that form the core, and four sulfonylurea receptor (SUR1, SUR2A, or SUR2B) subunits that regulate the channel (Fig. 1). Kir6.x and SURx isoforms have distinct tissue expression patterns and co-assemble to form KATP channel subtypes, each with distinct biophysical properties and sensitivities to intracellular ATP and ADP (reviewed in, Nichols, 2006).

Fig. 1.

Overall Topology and CryoEM structure of the KATP channel. KATP channels are hetero-octamers of four Kir6.x subunits that form the K+ conducting pore and four regulatory SURx subunits. (A) Topology of SUR1 and Kir6.2 with domains labeled and colored to match the 3D structures shown below. (B) Structural model of the pancreatic KATP channel generated using coordinates from PDB ID 6BAA (Martin, Kandasamy, DiMaio, Yoshioka, & Shyng, 2017), with the core Kir6.2 tetramer forming the potassium ion pore (Forest green). The outer regulatory proteins SUR1 has three transmembrane domains, TMD0 (pale cyan), TMD1 (sky blue) and TMD2 (pale green), two cytoplasmic nucleotide binding domains, NBD1 (sky blue) and NBD2 (pale green), and a cytoplasmic linker L0 (teal) that connects TMD0 to the ABC core structure of the protein. Each Kir6.2 subunit has two transmembrane helices, the inner helix and outer helix, an intermembrane pore helix, and cytoplasmic N- and C-terminus. ATP is bound to Kir6.2 (yellow spheres), and the K+ ion path is closed. Sulfonylureas also bind and inhibit the channel, and glibenclamide (GBC) is captured bound to the channel (purple spheres). Sulfonylureas and ATP binding help stabilize the full-channel complex in the closed conformation represented in this figure.

The pancreatic β-cell KATP channel comprising Kir6.2 and SUR1 was the first to be cloned and reconstituted, and has been studied extensively (Inagaki et al., 1995). In β-cells, KATP channels act as a key link in glucose-induced insulin secretion (Aguilar-Bryan & Bryan, 1999; Ashcroft, 2005). In these cells, fluctuations in the [ATP]/[ADP] ratio, brought about by changes in blood glucose levels, push the equilibrium of KATP channels toward the closed or open state. Thus, when blood glucose levels rise, the intracellular [ATP]/[ADP] ratio also rises, blocking K+ efflux through KATP channels. This depolarizes the β-cell and opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels; the subsequent Ca2+ influx then triggers exocytosis of insulin secretory granules. When blood glucose levels fall, the intracellular [ATP]/[ADP] ratio will fall, pushing the equilibrium toward open KATP channels, repolarizing the β-cell, and blocking further insulin release. Mutations in the genes encoding KATP channel subunits (ABCC8 for SUR1 and KCNJ11 for Kir6.2) that disrupt channel expression or function lead to a breakdown in glucose homeostasis. In general, mutations that cause gain-of-function where constitutively open channels preclude insulin secretion result in neonatal diabetes (Ashcroft, Puljung, & Vedovato, 2017; Pipatpolkai, Usher, Stansfeld, & Ashcroft, 2020). By contrast, mutations that cause loss-of-function lead to β-cell depolarization and persistent insulin release even when blood glucose levels are dangerously low as seen in the disorder congenital hyperinsulinism (Macmullen et al., 2011; Martin, Chen, Devaraneni, & Shyng, 2013; Stanley, 1997; Yan et al., 2007). Below we provide an overview of the studies that led up to our effort to resolve high resolution structures of KATP channels.

1.1. Functional regulation of KATP channels

The opposing inhibitory action of ATP and stimulatory action of MgADP is a primary mode of physiological regulation of KATP channel function. The ATP concentration is relatively stable in most cells, but small changes in [ATP] that are coupled with much larger changes in [ADP] result in significant changes in the [ATP]/[ADP] ratio (Detimary et al., 1998; Nilsson, Schultz, Berggren, Corkey, & Tornheim, 1996), and shift the apparent ATP sensitivity and effectively regulate channel activity (Tarasov, Dusonchet, & Ashcroft, 2004).

Both the pore-forming Kir6.2 subunit and the regulatory SUR1 subunit are required to confer the full range of gating regulation. Kir6.2, a member of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel family, contains two transmembrane helices, a pore helix, and cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domains (Fig. 1A). SUR1 belongs to the ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) transporter family, although it has no known transporter activity. SUR1 contains a prototypical ABC core module with two transmembrane domains (TMD1 and TMD2) and two nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2), and in addition has an N-terminal transmembrane domain called TMD0 connected to the ABC core by a cytoplasmic loop referred to as L0 (Fig. 1B) (also classified as a member of the ABC transporter type IV based on its TMD fold; (Thomas et al., 2020)). Extensive mutagenesis in conjunction with biochemical and electrophysiological studies have been carried out to define the functional role of the two subunits in channel gating (reviewed in Ashcroft et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2020).

In the absence of ATP, KATP channels display so-called burst kinetics, characterized by periods of rapid openings and closings separated by long closed intervals (Alekseev, Kennedy, Navarro, & Terzic, 1997; Craig, Ashcroft, & Proks, 2008). Activity in this ATP-free condition is dependent on membrane phosphoinositides, in particular phosphatidylinositol-4,-5-bisphosphate (PIP2) (Baukrowitz et al., 1998; Branstrom et al., 1998; Enkvetchakul, Loussouarn, Makhina, Shyng, & Nichols, 2000; Shyng & Nichols, 1998). PIP2 opens the channel by direct interactions with Kir6.2; SUR1 increases the sensitivity of the channel to PIP2 stimulation by more than 10-fold (Baukrowitz et al., 1998; Shyng & Nichols, 1998). This hypersensitizing effect of SUR1 is mediated by its N-terminal transmembrane domain TMD0, which interacts with Kir6.2 and stabilizes the interaction between Kir6.2 and PIP2 (Pratt, Tewson, Bruederle, Skach, & Shyng, 2011). However, whether SUR1-TMD0 directly participates in PIP2 binding remains an open question.

ATP inhibition of KATP channels, involving non-hydrolytic binding at the intracellular face of Kir6.2, acts to decrease the frequency and length of the burst periods and increases the duration of the closed intervals (Babenko, Gonzalez, & Bryan, 1999). Mutagenesis studies indicate that ATP and PIP2 may have overlapping but non-identical binding sites in Kir6.2 and that they compete functionally to close or open the channel, respectively (Antcliff, Haider, Proks, Sansom, & Ashcroft, 2005; Cukras, Jeliazkova, & Nichols, 2002a, 2002b; Shyng, Cukras, Harwood, & Nichols, 2000). Each channel contains four ATP-binding sites, although ATP binding at a single site appears sufficient to close the channel, suggesting a concerted gating model (Drain, Geng, & Li, 2004; Markworth, Schwanstecher, & Schwanstecher, 2000). As is the case for PIP2, SUR1 sensitizes Kir6.2 to ATP inhibition by about a factor of 10 (Tucker, Gribble, Zhao, Trapp, & Ashcroft, 1997). There is converging evidence from mutagenesis, structural and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments that a positively charged lysine residue (K205) in L0 of SUR1 contributes to ATP binding (Ding, Wang, Wu, Kang, & Chen, 2019; Pratt, Zhou, Gay, & Shyng, 2012; Usher, Ashcroft, & Puljung, 2020).

Nucleotide activation occurs at the nucleotide binding domains of SUR1 and acts to antagonize ATP inhibition (Gribble, Tucker, & Ashcroft, 1997). The requirement of Mg2+ in this process has prompted studies to examine nucleotide interactions and hydrolysis at the NBDs. These studies led to a proposal that hydrolysis of MgATP to MgADP at NBD2, which contains the consensus ATPase site, stabilizes ATP binding at NBD1, which carries a degenerate ATPase site, and drives dimerization of the NBDs to promote channel opening at Kir6.2 (Masia & Nichols, 2008; Matsuo, Kimura, & Ueda, 2005; Zingman et al., 2001). It is worth noting that direct measurements of MgATP hydrolysis using purified SUR or recombinant SUR NBDs indicate relatively poor hydrolysis efficiency (de Wet et al., 2007; Masia, Enkvetchakul, & Nichols, 2005), suggesting that increased MgADP binding at NBD2 as intracellular [ADP] rises may be sufficient to induce or stabilize conformational changes at the NBDs to stimulate channel opening.

SUR1 is also the primary binding site of sulfonylureas, which are widely used antidiabetics that stimulate insulin secretion by inhibiting KATP channels (Aguilar-Bryan & Bryan, 1999; Gribble & Reimann, 2003). Discovered in the 1940s as sulfonamide drugs that have hypoglycemic effects, sulfonylureas were subsequently shown to interact specifically with the sulfonylurea receptor SUR, giving it its namesake (Aguilar-Bryan, Nichols, Rajan, Parker, & Bryan, 1992). Tolbutamide was part of the first generation of hypoglycemic compounds, later replaced by second-generation compounds like glibenclamide, which have 100 to 1000-fold higher affinity and potency in blocking KATP currents. These drugs reduce channel activity, in part, by stabilizing the ABC-core structure of SUR1 in a so called “inward-facing” conformation and preventing NBD dimerization even in the presence of MgADP (Ortiz, Gossack, Quast, & Bryan, 2013). By contrast, diazoxide, a potassium channel opener, which is effective in treating certain congenital hyperinsulinism patients who have reduced KATP channel activity, interacts with SUR1 and stabilizes it in a MgATP/MgADP-bound, NBD-dimerized state to stimulate channel activity (Zingman et al., 2001). Even though SUR1 harbors the binding sites of these inhibitory and stimulatory pharmacological modulators, Kir6.2 also plays a role. Deletion of the distal N-terminus of Kir6.2 has been shown to reduce channel inhibition by sulfonylureas and affect the extent to which diazoxide stimulates channel activity (Koster, Sha, & Nichols, 1999).

Thus, in the multimeric KATP complex physiological and pharmacological ligands may interact with the Kir6.2 pore subunit, the SUR1 regulatory subunit, or both to induce conformational changes that result in changes in channel behavior. To understand the mechanism of these processes, high resolution channel structures are essential. With recent advances in single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) techniques and increased access to microscopes through local institutional investment and national laboratories, obtaining high resolution KATP channel structures is attainable, provided that sufficient quality and quantity of the channel can be produced and purified for use in cryoEM.

1.2. Assembly and trafficking of KATP channels

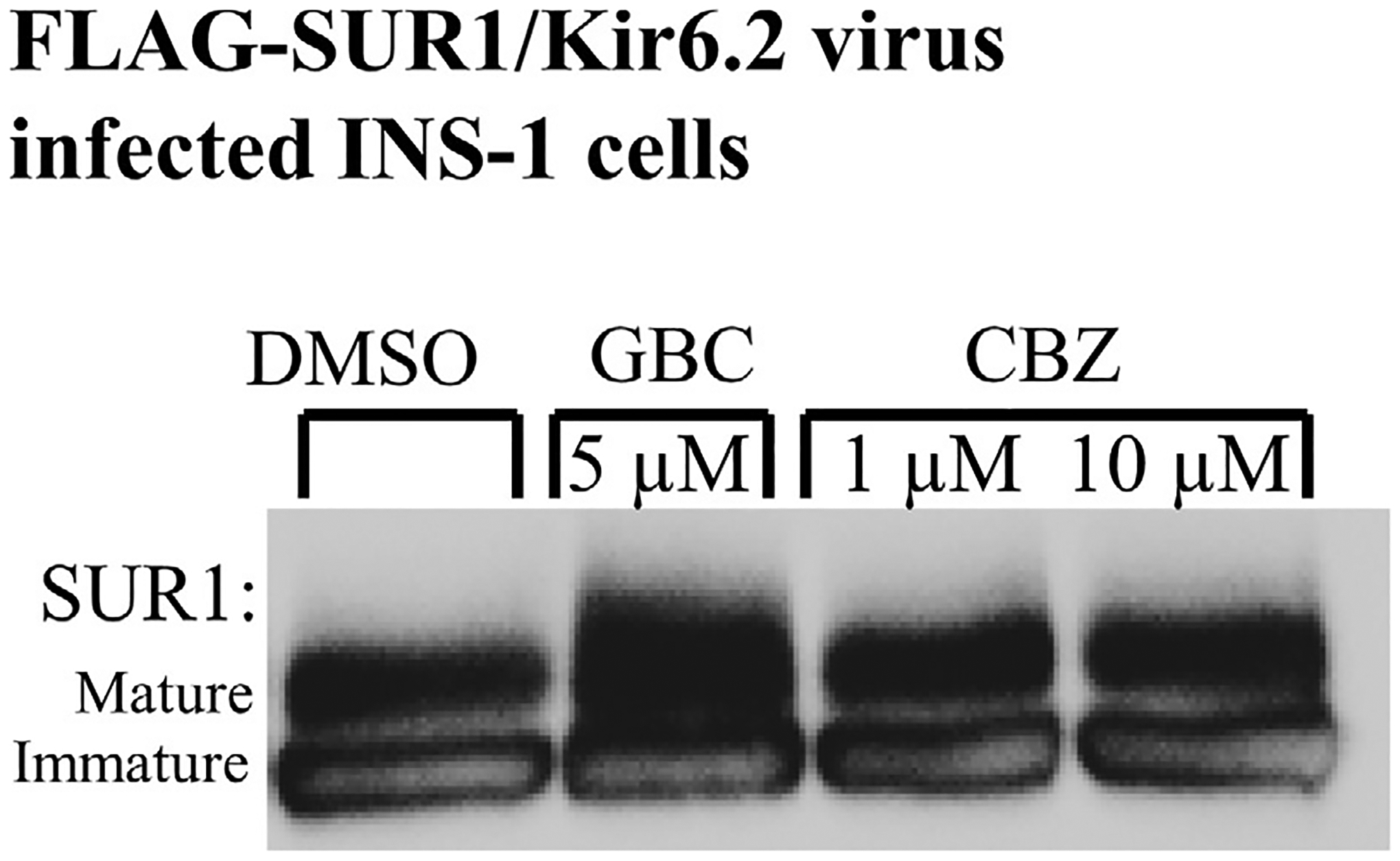

Biogenesis and assembly of KATP channel subunits occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and both Kir6.2 and SUR1 are required for channel expression at the cell surface (Zerangue, Schwappach, Jan, & Jan, 1999). When either SUR1 or Kir6.2 is expressed alone, an ER retention/retrieval signal-RKR- in each of the subunits prevents ER exit (Zerangue et al., 1999). In the fully assembled hetero-octameric KATP channel complex the RKR motifs are concealed, allowing the channel to exit the ER and traffic to the cell surface. SURx is glycosylated, first in the ER, then further modified when the channel complex traffics through the Golgi to yield mature SUR1 protein (Fig. 2). Mutation of these glycosylation sites causes ER retention of SUR1, suggesting that lectin chaperones calnexin/calreticulin, which assist in the folding of glycoproteins, participate in the folding and assembly of KATP channels (Conti, Radeke, & Vandenberg, 2002). Mature or complex-glycosylated SUR1 protein destined for the plasma membrane migrates slower on SDS-PAGE than the immature, core-glycosylated SUR1 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Glibenclamide and carbamazepine increase SUR1 maturation as evidenced by SUR1 glycosylation. Western blot of whole cell lysates of INS-1 clone 832/13 cells transduced with recombinant Kir6.2 plus FLAG-tagged SUR1 (f-SUR1) adenovirus and the tTA virus. SUR1, a glycoprotein, shows two bands in immunoblots: a lower core-glycosylated (immature) form that has not exited the ER and an upper complex-glycosylated (mature) band that has trafficked through the Golgi and is the form expressed in the plasma membrane. Incubation of cells with glibenclamide (GBC) or carbamazepine (CBZ) increases the levels of the mature band compared to those treated with DMSO control. This demonstrates the ability of sulfonylureas and carbamazepine to enhance expression and maturation of the KATP channel.

Unassembled or misassembled subunits in which the—RKR- ER retention motif is exposed are prevented from reaching the plasma membrane and are cleared through ER-associated degradation (ERAD), allowing for quality control in the KATP biogenesis pathway (Yan, Lin, Cartier, & Shyng, 2005). Thus, the ubiquitin and proteasome-mediated ERAD is a primary check on KATP channels during biogenesis and this process, in part, regulates the surface expression of KATP channels. Studies examining the kinetics of the biogenesis pathway using metabolic pulse-chase labeling have demonstrated the intrinsic inefficiency of KATP assembly, estimating that only about 20% of newly synthesized SUR1 or Kir6.2 actually forms mature complexes, with the remaining pool being rapidly degraded (Chen, Bruederle, Gaisano, & Shyng, 2011; Yan et al., 2004, 2005, 2010). Similar studies also showed increased stability of SUR1 and Kir6.2 when the two subunits were co-expressed, indicating the subunits become more stable upon multi-meric assembly (Crane & Aguilar-Bryan, 2004; Yan et al., 2005). Interestingly, Yan et al. demonstrated that inhibiting the proteasome increases surface expression of KATP channels (Yan et al., 2005). This provided the first evidence that ERAD-targeted nascent channel proteins could be redirected to enhance channel expression by manipulating KATP proteostasis mechanisms.

Studies over the past 20 years on disease mutations, particularly those associated with congenital hyperinsulinism, have identified a class of KATP channel mutations, mostly in SUR1, that cause loss of channel function by preventing proper biogenesis and trafficking, and thus, compromise surface expression of the channel (Cartier, Conti, Vandenberg, & Shyng, 2001; Crane & Aguilar-Bryan, 2004; Partridge, Beech, & Sivaprasadarao, 2001; Taneja et al., 2009; Taschenberger et al., 2002; Yan et al., 2004, 2007). These mutations are collectively referred to as trafficking mutations. In most cases, mutant proteins are synthesized but fail to reach the plasma membrane, likely due to a disruption in the folding or oligomeric assembly process. The result is a constitutively depolarized β-cell with unregulated levels of insulin release. Patients with such mutations often undergo partial or subtotal pancreatectomy to avoid life-threatening hypoglycemia, which could lead to life-long insulin dependency.

1.3. Pharmacological chaperones of KATP channels

Identification of KATP trafficking mutations prompted search for small molecules that can correct channel trafficking defects to restore channel surface expression. In a number of diseases caused by protein misfolding and mistrafficking, including cystic fibrosis (CF), familial hypercholesteremia, retinitis pigmentosa, and diabetes insipidus (Hanrahan, Sampson, & Thomas, 2013; Powers, Morimoto, Dillin, Kelly, & Balch, 2009), small molecules that bind to defective proteins and facilitate their proper folding and localization, termed pharmacological chaperones, have been shown to correct trafficking defects and in some cases restore full or partial function to reverse disease phenotypes (Powers et al., 2009). Our group showed that sulfonylureas including tolbutamide and glibenclamide, as well as another class of KATP channel inhibitors known as glinides such as repaglinide, act as pharmacological chaperones and rescue trafficking-impaired mutant KATP channels from the ER to the cell surface (Martin et al., 2016, 2019; Martin, Sung, & Shyng, 2020; Yan et al., 2004, 2007). SUR1 shares structural similarity with CFTR, which is also a member of the ABC transporter family. ΔF508 is the most prevalent cystic fibrosis-causing mutation that results in misfolding of CFTR and many small molecules have been identified to correct the trafficking defect through chemical library screens (Hanrahan et al., 2019). We, therefore, also explored these smaller molecules for their ability to correct KATP channel trafficking defects caused by SUR1 mutations. This led to the discovery that carbamazepine, a clinically used anticonvulsant best known for its inhibitory action on voltage-gated sodium channels and also shown to be effective in rescuing CFTRΔF508, is a highly effective pharmacological chaperone for KATP channels (Sampson et al., 2013). Functional testing revealed that carbamazepine is, surprisingly, also a highly potent KATP channel inhibitor, with an IC50 ~25 nM. The aforementioned KATP pharmacological chaperones not only correct trafficking defects of mutant channels but also significantly enhance maturation and surface expression of wild-type channels (Fig. 2). In contrast to KATP inhibitors, small molecule activators of KATP channels including diazoxide, NN414, and VU0071063 do not rescue trafficking mutants; in fact, they reduce maturation and surface expression of wild-type KATP channels (Martin et al., 2016, 2020). These findings indicate that channel inhibitors facilitate channel biogenesis and assembly while channel activators have the opposite effect.

Intriguingly, the KATP channel pharmacological chaperones identified thus far all seem to only correct trafficking mutations located in TMD0 of SUR1, a domain capable of assembling with Kir6.2 on its own (Babenko & Bryan, 2003; Chan, Zhang, & Logothetis, 2003; Martin et al., 2020). Moreover, in the absence of Kir6.2, pharmacological chaperones do not rescue SUR1-TMD0 mutants retained in the ER even when the ER retention signal in SUR1 is inactivated, suggesting the chaperones act on the channel complex, rather than SUR1 alone (Yan, Casey, & Shyng, 2006). Specifically, deletion of the Kir6.2 N-terminus abolishes the ability of pharmacological chaperones to rescue channel trafficking defects caused by SUR1-TMD0 mutations, and also markedly reduces maturation and surface expression of wild-type channels, indicating that the Kir6.2 N-terminus has a critical role for channel biogenesis, assembly, and/or trafficking (Devaraneni, Martin, Olson, Zhou, & Shyng, 2015; Schwappach, Zerangue, Jan, & Jan, 2000). Using genetically encoded photocrosslinkable unnatural amino acid p-azidophenylalanine placed at the N-terminus of Kir6.2, we showed that channel inhibitors enhance crosslinking between Kir6.2 N-terminus and SUR1, suggesting their pharmacological chaperoning effects involve stabilizing the interactions between Kir6.2 and mutant SUR1 (Devaraneni et al., 2015). Taken together, the studies above suggest that despite having diverse chemical structures, KATP channel inhibitors likely share a common mechanism to modulate channel biogenesis and activity.

Importantly, many KATP trafficking mutants rescued to the cell surface by pharmacological chaperones are functional (reviewed in, Martin et al., 2020), offering potential therapeutic promise to affected congenital hyperinsulinism patients. However, the lack of a full mechanistic understanding of how KATP pharmacological chaperones work hinders further progress. In this regard, several key questions remain. First, how do KATP pharmacological chaperones with diverse chemical structures interact with the channel to inhibit channel activity and facilitate channel biogenesis and trafficking? Second, why do only trafficking mutations in TMD0 of SUR1 respond to pharmacological rescue? Third, what is the role of Kir6.2 in channel response to these drugs? These are the driving questions that led us to pursue high resolution structures of KATP channels.

2. General considerations: Expression system and construct design

Inefficient KATP channel assembly is an obstacle in producing enough KATP channel for cryoEM structural studies. Moreover, maintaining the integrity of a large multimeric protein complex like KATP channel also presents a challenge. Our work on pharmacological chaperones shed light on strategies to improve channel assembly efficiency and stabilize the channel complex during purification. For production of KATP channels, we chose recombinant adenovirus-mediated overexpression in a rat insulinoma cell line called INS-1 clone 832/13 (Hohmeier et al., 2000), which naturally expresses KATP channels. The cell line provides a native-like environment and high capacity for synthesis, folding and assembly of the channel. Although other expression systems have been employed such as insect Sf9 cells, which have previously been used to generate a negatively stained cryoEM structure of channels formed by a SUR1-Kir6.2 fusion protein (Mikhailov et al., 2005) and the BacMam system in HEK293 GnTl- cells that lack complex glycosylation (Lee, Chen, & MacKinnon, 2017; Li et al., 2017), which is popular for expressing membrane proteins for structural studies (Goehring et al., 2014), we did not find these systems to be superior.

For expression constructs, we chose to co-express Kir6.2 and SUR1 as separate proteins as in native channels. Other groups have used fusion protein constructs where the C-terminus of SUR1 is linked to the N-terminus of Kir6.2 with a linker ranging from 6 to 39 amino acids (Ding et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017; Mikhailov et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2018), presumably to help maintain the integrity of the channel complex during purification. However, such fusion design imposes undesired physical constraints that may alter channel structures and properties (Cartier et al., 2001; Ding et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2018). For purification, a FLAG-tag is placed at the N-terminus of SUR1, which does not alter channel gating or trafficking (Cartier et al., 2001; Yan et al., 2007). Alternative purification strategies such as His tag in tandem with strep tag or GFP tag at the C-terminus of Kir6.2 or SUR1-Kir6.2 fusion have been reported by others (Lee et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017).

INS-1 cells clone 832/13 are infected with three different recombinant adenoviruses encoding genes for (1) an N-terminal FLAG-tagged (DYKDDDDK) hamster SUR1, (2) rat Kir6.2, and (3) a tetracycline-inhibited transactivator (tTA) for the tTA-regulated f-SUR1 expression (Pratt, Yan, Gay, Stanley, & Shyng, 2009). We use hamster SUR1/rat Kir6.2 recombinant channels in part for historical reasons as this channel protein combination has been used by many groups for numerous structure-function studies, but also because these channels express at a higher level compared with human channels (Chen et al., 2013; Macmullen et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2007). Hamster SUR1 and rat Kir6.2 are 95% and 96% identical to the human sequences, respectively, and these heterologously expressed channels have gating properties indistinguishable from endogenously expressed KATP channels in INS-1 clone 832/13 cells (Pratt et al., 2009). Recombinant adenoviruses were constructed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the AdEasy kit (Stratagene). INS-1 cells clone 832/13, cultured in RPMI 1640 with 11.1 mM d-glucose plus 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, were infected with the adenoviral constructs in 15 cm tissue culture plates. Protein was expressed in the presence of 1 mM Na butyrate, which improves transcription, and 5 μM glibenclamide, which promotes channel biogenesis and surface expression. Alternative pharmacological chaperones such as tolbutamide, carbamazepine (CBZ), repaglinide (RPG) may be considered to enhance expression and purification efficiency. Glibenclamide and repaglinide have high affinity for the channel and are not easily removed from purified samples. Therefore, lower affinity pharmacological chaperones are preferred if they are to be removed from the final sample for cryoEM. 40–48h post-infection, cells were harvested by scraping and cell pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen before being stored at −80 °C until purification (for up to 2 months).

For purification, cells were re-suspended in hypotonic buffer (15 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 0.25 mM DTT, pH 7.5) and lysed by Dounce homogenization. The total membrane fraction was prepared, and membranes were re-suspended in ‘Membrane Solubilization Buffer’ (MSB: 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 M KCl, 0.05 M HEPES, 0.25 mM DTT, 4% sucrose or trehalose, 1 mM ATP, 1 μM GBC, pH 7.5) and solubilized with 0.5% Digitonin. Alternative detergents such as DDM, GDN, CHS may be considered, although in our experience digitonin gives the best outcome. Nanodiscs may also be considered (Autzen, Julius, & Cheng, 2019); however, given the large size of the channel complex reconstitution into nanodiscs may be challenging. The solubilized membrane fraction was incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity agarose for 4–16h and eluted with MSB containing 0.25 mg/mL FLAG peptide and 0.06% digitonin. Note in our initial study, proteins eluted from the FLAG-beads were further separated by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to improve sample homogeneity (Martin, Kandasamy, et al., 2017). However, in our experience SEC requires large volumes of costly digitonin-containing buffer, and results in lower yield of purified KATP channel, without being necessary for achieving samples suitable for cryoEM. We, therefore, no longer include this step in our routine sample preparations. Purified channels were concentrated to 0.7–1 mg/mL and used immediately for grid preparation for both negative stain EM and cryoEM grid preparation. To achieve high quality cryoEM grids, the sample is purified fresh and maintained on ice for as short of duration as possible before being vitrified on cryoEM grids (Dubochet et al., 1988). This time sensitivity necessitates the ownership or access to a vitrobot. Note, we do not recommend using purified channels that have been frozen and thawed for cryoEM grid preparation as freezing and thawing cause protein aggregation and precipitation.

3. Protocol of KATP channel production and purificiation

3.1. Equipment

Hettich Zentrifugen Refrigerated Centrifuge (or equivalent refrigerated centrifuge)

Beckman Optima LTX Ultracentrifuge

Beckman TLA 55 S/N 02U 656 Rotor

A Tube Rotator or Rotisserie in 4 °C refrigerated cabinet or cold room

Eppendorf Thermomixer (Heated rotation block suitable for eppendorph tubes)

Tight Dounce glass homogenizer

15 cm diameter culture plates

SANYO CO2 incubator

ESCO Labculture Reliant Class II Type A2 Biological Safety Cabinet

Leica Microscope

Amicon Ultra Centrafugal filters Ultacel -100 K

33 mm Syringe filter 0.2 μm, PVDF (Fisherbrand)

Beckman centrifuge tubes 1.5 mL capacity

1000 μl Large Oriface Pipet tip (USA scientific)

Analytical Balance (OHAUS)

pH meter (Corning)

T-25 Flasks

Liquid Nitrogen Cryo Dewar

15 mL Sterile Conical Vial (Falcon Tube)

50 mL Sterile Conical Vial (Falcon Tube)

Hemocytometer

250 mL Nalgene centrifugation bottles

F14 rotor (or equivalent capable of holding 250 mL centrifugation bottles)

Cell Scrapers

3.2. Chemicals

Potassium Chloride (Fisher Scientific)

Sodium Chloride (Fisher Scientific)

HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; Fisher Scientific)

Magnesium Chloride (Fisher Scientific)

Potassium Hydroxide (Fisher Scientific)

D-Trehalose, 99% anhydrous (ACROS ORGANICS)

1,4-Dithiothreitol (DTT) (Sigma)

Adenosine 5′-Triphosphate Magnesium Salt (Sigma-Aldrich)

Tolbutamide (Sigma-Aldrich)

Glibenclamide (GBC) (Sigma-Aldrich)

anti-FLAG M2 affinity agarose (Sigma-Aldrich)

FLAG peptide 5 mg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich)

cOmplete™ Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche)

Digitonin, High Purity (EMD Millipore Corp, USA)

OptiMEM (Fisher Scientific)

INS-1 Growth Media (RPMI 1640 with 11.1 mM d-glucose plus 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol)

Phosphate Buffered Saline pH 7.4 (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM KCl)

Trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich)

Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline ((PBS + 9 mM MgCl2 + 5.9 mM CaCl2; DPBS; Sigma-Aldrich)

Sodium Butyrate (Store NaBu at 4 °C as a 0.5 M stock in OptiMEM)

3.3. Expression (7–14 days)

NOTE: To help prevent contamination, preform all manipulations in a Class II Type A2 biological safety cabinet, and regularly test for mycoplasma contamination.

Day 1: Thawing cells and starting growth

Pre-warm water bath to 37 °C, and prepare a 15 mL sterile conical tube with 5 mL of INS-1 growth media. Warm media to 37 °C.

Remove vial of frozen INS-1 clone 832/13 cells (~5 × 106 to 1 × 107 cells in 1 mL volume) from LN2 cryo dewar (−196 °C), and immediately place vial in 37 °C water bath for ~1 min (to thaw as quickly as possible).

Transfer cells into the pre-warmed tube of 5 mL of INS-1 growth media, gently rock to mix.

Centrifuge cells at ~1000xRCF for 5 min.

Aspirate media and gently re-suspend cells in 5 mL of pre-warmed growth media.

Transfer to a T-25 flask and incubate in a standard incubator for adherent cultures overnight at 37 °C, 5.0% CO2.

Day 2 ~ 10: Maintaining growth and amplifying cells

Replace media with fresh INS-1 growth media the following day. Aspirate old media and replace with 5 mL of pre-warmed INS-1 growth media

When cells reach 70–80% confluency, split cells. Typically, cells will need to be split every 2–4 days. Split at a density ratio of 1:3 to 1:6. Aim to have six to eight T-150 flasks worth of confluent cells to seed before infection. This will be enough for ten 15 cm plates

Day ~11: Seeding cells for infection

NOTE: Work in small batches of 3 or 4 plates to reduce the amount of time cells are left exposed without solution. Plates can be reused for infection if washed three times with PBS to remove residual cells.

Aspirate media and gently wash monolayer of cells with 10 mL 37 °C PBS

Aspirate PBS. Add 5 mL of trypsin (0.05% EDTA). Make sure entire surface is covered by rocking the dish. Place in incubator for approximately 1–2 min

Retrieve cells and make sure they are detached from surface (tilt the vessel and the monolayer of cells should slide down). Add 5 mL of INS-1 growth media to the first trypsinized plate. Resuspend cells, triturate, and transfer volume to the next plate to collect all the cells. Once all the plates have been washed, transfer the media to a 50 mL conical tube

Rinse the first plate again with 20 mL of media, and wash each subsequent plate by transferring the media over. Collect the cells in the same 50 mL conical tube

Centrifuge cells down at room temperature (~000xRCF Beckman table top centrifuge for 10 min)

Aspirate trypsin/ growth media solution and resuspend cells initially in 10 mL of media. Count cells to determine how much additional media to add

Count Cells: Before pipetting cells into a hemocytometer, gently invert cells to obtain an equal distribution of suspended cells in the media. Pipette 10 μL of cells into a hemocytometer

Calculate the number of cells per mL and seed approximately 0.9–1.0 × 107 cells per plate

Seed cells in a total volume of 20 mL for each 15 cm plate. Rock 15 cm plate back and forth to distribute the cells evenly (do not swirl, swirling will cause cells to settle in the middle). Keep the plate level in the incubator so the cells settle evenly onto the plate. Be cautious of how many plates you can work with at any given time. Typically ten 15 cm plates are infected by working in two batches of five plates each

Passage remaining cells to propagate for additional infections

Day 12: Infecting INS-1 clone 832/13 cells with adenovirus

NOTE: Since the WT f-SUR1 (in Ad:TetR:EGFP) gene expression is regulated by the tetracycline promotor, co-infection of cells with an Ad: CMV:tTA virus carrying tetracycline-inhibited transactivator (tTA) gene is needed for SUR1 expression.

Calculate the amount of virus needed to achieve the necessary MOI: (Number of cells in dish or well x desired MOI)/Titer of the virus stock (pfu/ml) = volume of virus needed to achieve the MOI. For example, to infect a 15 cm plate of 1.2 × 107 INS-1 cells with WT Kir6.2 at an MOI of 60, use the following values in the equation to determine how much virus stock to use per plate: ((12 × 106) × (60))/(7.2 × 1011 pfu/mL virus stock) = 0.001 mL (1 μL) of virus stock per plate

Because INS-1 cells have a doubling rate of about 48–72h, the number of cells can be estimated to increase by about 1/3 after 20–24h. The number of cells at the time of infection can also be verified by counting an identical plate

Before beginning the infection thaw an appropriate number of virus tubes on ice (prepared according to AdEasy kit (Stratagene) instructions).

Create a master mix of all three viruses (SUR1, Kir6.2, tTA) in OptiMEM. Infections are carried out in OptiMEM at a volume that is half the working volume of the vessel, so for a 15 cm plate with a working volume of 20 mL, preform the infection in 10 mL of OptiMEM

Remove cells from the incubator, aspirate media, and wash cells with 10 mL of 37 °C DPBS

Aspirate DPBS and carefully add virus mixture dropwise to cells. Rock back and forth to ensure the entire surface is covered

Return to incubator for 2 h, rocking plate halfway through incubation to mix

After 2h, terminate the infection by aspirating the media from each plate, and gently replace with 20 mL of 37 °C INS-1 growth media, optionally add Sodium Butyrate (NaBu) to a final concentration of 1 mM to cells

Return cells to incubator. Harvest 40–48h post-infection

Day 13: Supplement with pharmacological chaperones (e.g., Glibenclamide, repaglinide, or carbamazepine):

Add glibenclamide (GBC) to a final concentration of 5 μM. Store lyophilized GBC at 4 °C, and dissolve fresh in DMSO at 50 mM. Make a 50 μM stock in INS-1 growth media. Mix 2 mL of the 50 μM stock with 18 mL of INS-growth media per plate to refresh each plate’s media each day during growth.

Day 14: Harvest cells

NOTE: Before retrieving plates from the incubator, prepare ice-cold PBS (without magnesium and calcium), prepare an ice bucket, pre-wet a 250 mL Nalgene centrifugation bottle by rinsing with cold deionized H2O, and prepare a scraper (rubber policeman).

Retrieve a plate from the incubator and place on ice

Aspirate media, add 10 mL of ice-cold PBS

Scrape cells, triturate and transfer to 250 mL Nalgene centrifugation bottle

Add 10 mL of PBS to the same plate, collect any remaining cells and transfer to the same centrifugation bottle

Repeat for all plates, keep the harvested cells in the centrifugation bottle on ice during the harvest

Place bottle in pre-chilled F14 rotor in centrifuge. Centrifuge at 7000 RPM for 15 min to pellet cells. Decant PBS. Snap freeze pellet using liquid N2

Store in clearly labeled tube with date, number of plates, passage number of INS-1 cells, and infection conditions (such as batch of viruses used), and whether a pharmacological chaperone was included. Store in a −80 °C freezer until protein purification

3.4. Purification (2 days)

Day 0: Prepare reagents

20 × Protease Inhibitor solution (PI): 1 cOmplete™ Mini Protease inhibitor tablet (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in 0.5 mL deionized H2O (Store at −20 °C)

100 mM ATP pH 7.5 solution in deionized H2O; adjust pH to neutral with KOH as high concentrations of ATP can lower pH of the buffer, and alter KATP channel activity (Store at −80 °C)

Hypotonic Solution (Make with 95% volume water, such that 5% addition of PI will result in the following):15 mMKCl, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5

Membrane Solubilization Buffer (Make with 95% volume water, such that 5% addition of PI will result in the following): 200 mM NaCl, 100 mM KCl, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5

Day 1

-

1

Remove INS-1 clone 832/13 cells expressing SUR1/Kir6.2/tTA from the −80 °C freezer and defrost on ice. Use five to ten 15 cm plates worth of cells for cryoEM sample preparation and one 15 cm plate worth of cells for negative-stain EM sample preparation; remove 6–11 plates total. This protocol is for six plates

-

2

Turn on Beckman J2–21 Centrifuge (or equivalent refrigerated centrifuge) and an ultracentrifuge capable of 54,000xRCF, to allow centrifuges to cool to 4 °C. Place the ultracentrifuge tubes on ice, and cool centrifuge rotor to 4 °C. Defrost frozen stocks of 20 × Protease inhibitor (cOmplete™ protease inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), 100 mM ATP pH 7.5 solution, and defrost any solutions of pharmacological chaperones. Place the glass homogenizer on ice

-

3

To prepare the hypotonic solution with protease inhibitor and ATP: First, add 300 μL of the 20 × Protease Inhibitor Stock in 5.7 mL of “95%” Hypotonic Solution stock. Second, 60 μL of the 100 mM ATP pH 7.5 stock is added to a final concentration of 1 mM, then cool the hypotonic solution on ice

-

4

Resuspend cell pellet in cold hypotonic solution with protease inhibitor and ATP, 6 mL for six 15 cm plates worth of cells

-

5

Pipette the solution up and down to re-suspend the cell pellet. This step should be done gently to make sure there are no bubbles, but thoroughly to suspend the cells. (Bubbles create a water/air interface, which cause loss and denaturation of protein.)

-

6

Leave on ice for 20–30 min (cell lysis can be checked on the microscope at this step), gently mixing by tipping the tube back and forth occasionally. The purpose of this step is to swell and burst the cells

-

7

Gently pipette up and down to re-suspend the cell pellet and pipette solution with cells into the cold glass homogenizer. Keep on ice while mixing, and avoid generating bubbles. Pull the pestle up just to the top level of the solution, twisting while pulling up. Accidently bringing the pestle higher than the top of the meniscus of the solution will cause bubble formation. Push the pestle back in again twisting while pushing down, with purposeful but gentle force. Repeat with ~25–30 strokes, where one stroke is one up and down motion with care so as to minimize bubble formation. Excessive homogenization will cause the nuclear fractions to lyse which will release the DNA and cause loss/aggregation of protein

-

8

Transfer using a pipette the lysed cells from the glass homogenizer to the cold ultracentrifuge tubes without generating bubbles, carefully balance the tubes within 0.01 g

-

9

Place tubes in the 4 °C Beckman TLA55 rotor (or equivalent capable of high speeds), centrifuge the lysed cells at 54,000 xRCF for 45 min

-

10

During this spin make a 10% Digitonin solution (only good for ~1 day). Accurately weigh 28 mg (or more, if need be for accuracy) dissolve into 280 μL deionized H2O. Use an Eppendorf Thermomixer at 70 °C with rotation at ~225 rpm to dissolve the 10% digitonin solution. When dissolved the solution becomes clear (~15 min).

-

11

During centrifugation and Digitonin solubilization, prepare the Membrane Solubilization Buffer: Add 300 μL of 20 × Protease inhibitor to 5.7 mL Membrane Solubilization Buffer. Add 4% w/v trehalose to MSB. Add 60 μL of the 100 mM ATP pH 7.5 stock (1 mM ATP), and add 1 μM GBC. When digitonin is solubilized add 300 μL of 10% stock. Filter solution with a 0.2 μm syringe filter. Chill on ice

-

12

When the centrifugation is complete, remove and discard the supernatant containing soluble proteins and other soluble cellular components. Re-suspend the insoluble pellet containing the membrane fraction in cold Digitonin-MSB buffers prepared above. It is important to re-suspend the visible chunks of the pellet containing the membrane fraction, which can be done by gently pipetting 25–35 times. Take care to minimize bubble formation and keep sample cool on ice

-

13

Cover the ultracentrifugation tubes containing the resuspended insoluble pellet with parafilm and incubate with rotation at 4 °C for 90 min. About 30 min before 4 °C incubation is completed, gently thaw anti-FLAG gel resin on ice (described below).

-

14

After the 90 min incubation at 4 °C is complete, ultracentrifuge sample at 54,000xRCF at 4 °C for 45 min to pellet insoluble cell debris, save supernatant which contains membrane fraction solubilized in digitonin micelles in the 0.5% digitonin MSB (Digitonin CMC value of 0.02%).

-

15

Prepare anti-FLAG beads during centrifuge run. Using a large-orifice P1000 tip pipette 300 μL of 50% bead slurry into an Eppendorf tube (100 μL of beads is capable for binding to ~60 μg of the FLAG-tagged KATP channel). Wash beads two times with filtered cold PBS. Add 1000 μL of cold PBS to beads, mix by inversion, and centrifuge at 4000xRCF for ~30 s. Let tube sit on ice for 1 min to allow beads to completely settle. Carefully pipette off and discard supernatant. Repeat PBS wash. Next, wash the beads with MSB + PI (without digitonin). Add 650 μL of MSB + PI solution to tube, mix by inversion, and centrifuge at 4000xRCF for ~30 s. Let tube sit on ice for 1 min to allow beads to completely settle. Carefully pipette off and discard supernatant. Last, wash the beads with MSB + 0.5% Digitonin + PI + ATP + GBC (Same as sample buffer). Add 650 μL of MSB + 0.5% Digitonin + PI + ATP + GBC solution to the tube, mix by inversion, and centrifuge at 4000xRCF for ~30 s. Let tube sit on ice for 1 min to allow beads to completely settle. Carefully pipette off and discard supernatant

-

16

From the ultracentrifugation tubes from the completed centrifugation run, pipette the supernatant containing the solubilized membrane fraction into the freshly prepared anti-FLAG beads (no need to mix, be gentle).

-

17

Incubate the solubilized membrane fraction containing KATP channels on the anti-FLAG bead suspension with rotation at 4 °C overnight (at least 4h but less than 16h).

Day 2

Before removing the sample from incubation with rotation at 4 °C, prepare wash buffers and elution buffer and cool on ice. Prepare 10 mL of Membrane Solubilization Buffer without digitonin: Add 500 μL of 20 × Protease inhibitor to 9.5 mL Membrane Solubilization Buffer. Add 4% w/v trehalose to MSB. Add 50 μL of the 100 mM ATP pH 7.5 stock (1 mM ATP), and add 1 μM GBC. Prepare Wash buffers by 2-fold serial-dilution of digitionin concentrations.

Wash Buffers:

W1: 2 mL MSB with 0.5% Digitonin

W2: 2 mL MSB with 0.25% Digitonin

W3: 2 mL MSB with 0.125% Digitonin

W4: 3.4 mL MSB with 0.06% Digitonin

Elution Buffer: 600 μL of W4 (MSB with 0.06% Digitonin) plus 0.2 mg/mL FLAG peptide for six plates worth of cells.

NOTE: With the typical levels of expression that we achieve, 100 μL elution per plate of cells will yield ~150 μg/mL or ~170 nM KATP channel. Smaller volumes of elution buffer lead to more concentrated KATP channel, and so desired concentration can be achieved by adjusting elution volume depending on INS-1 expression or desired concentration. This will potentially avoid the need for downstream concentration steps using a centrifugal concentration device.

-

18

Remove the rotating sample incubating at 4 °C and centrifuge at 4 °C at 4000xRCF for ~30 s. Let tube sit on ice for 1 min to allow the beads to settle. Pipette off almost all of the supernatant, but carefully to avoid disturbing the soft anti-FLAG bead pellet that contains the KATP channel in digitonin particles

-

19

Wash beads with a decreasing 2-fold step-gradient of Digitonin concentrations in MSB. Place 2 mL of W1 buffer (0.5% Digitonin wash buffer) with the beads, being sure to minimize bead loss. Mix by gentle swirling, and incubate on ice for 10 min. Centrifuge at 4 °C for 30s at ~2000xRCF. Let tube sit on ice for 1 min to allow beads to settle. Remove a small amount for testing later. (W1, W2 and W3)

-

20

Pipette off remaining supernatant and repeat the wash steps again, with the next wash being with W2, then W3, then W4. Use the nanodrop to monitor the absorbance of 280 nm light by the sample. Typically one wash at each concentration is sufficient, but a second wash at 0.06% can be carried out

-

21

Elute KATP channels by adding 600 μL of elution buffer for six 15 cm plate worth of cells (MSB + 0.06% Digitonin, FLAG peptide to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml). Incubate with rotation at 4 °C for 1 h to elute. After about an hour, spin down the beads at approximately 4000 rpm for 30 s. Carefully transfer supernatant. The beads can be spun again, at higher speeds, to get all of the supernatant without getting any beads. Measure concentration via nanodrop or Bradford assay

-

22

Centrifuge elution at 45000xRCF at 4 °C for 30 min to remove any residual beads and aggregated proteins. Transfer supernatant to a cold eppendorph tube. The KATP channel particles are ready for setup of cryoEM grids and negative stain grids

CRITICAL: Freezing and thawing the sample causes aggregation and loss of protein, therefore sample preparation for cryoEM grids and Negative-stain EM grids needs to be carried out in the same day for the highest quality KATP particles.

4. Sample preparation for electron microscopy

4.1. Equipment

PELCO easiGlow™ Glow Discharge Cleaning System

Carbon-film, 400 mesh copper grid from Electron Microscopy Sciences (215–412-8400) CF400-CU

Whatman Filter Papers

Vitrobot Mark III (FEI, Hilsboro, OR)

UltraAu foil gold grids

Parafilm

4.2. Chemicals

1% Uranyl Acetate

Ultrapure H2O

Ethylene

Liquid Nitrogen

4.3. Negative stain grid preparation

NOTE: Preparation of samples for cryoEM is non-trivial, and requires valuable time on powerful electron microscopes. Before samples are deemed appropriate for cryoEM, sample quality should be confirmed using negative stain that provides high contrast to the particles and can be imaged using a regular electron microscope that is more accessible.

Care must be taken to minimize the radioactive waste generated during this procedure, and anything that touches the uranyl acetate solution must be stored separately for proper disposal including pipette tips and filter paper used for blotting. A station approved for radioactive use is specifically set up for negative stain, and proper approval for radioactive use must be obtained.

Day 2 (continued on same day as second day of purification)

Before beginning the protocol prepare a strip of Parafilm for holding drops of water, and prepare strips of filter paper for blotting the grids.

Place grids on slide or tray suitable for glow discharge, carbon side up. We use Carbon-film, 400 mesh copper grid from Electron Microscopy Sciences (215–412-8400) CF400-CU

Glow discharge grids to make hydrophilic (easiGlow™ 0.39 mBar, 15 mA, 30 s). While the grids are glow discharging place two ~15 μL drops of water onto a piece of parafilm for each grid to be used for negative stain

Spot each grid with 3 μL of ~0.1 mg/mL KATP channel sample, incubate 10–45s (A few different concentrations and incubation times are used for each preparation)

Wick sample using filter paper from edge of grid (take care not to let grid dry), and touch grid onto a water drop on the parafilm, then blot with filter paper

Touch grid into second water drop and blot with filter paper

Apply 3 μL of a 1% Uranyl Acetate solution and incubate for 30 s

Blot with filter paper and allow grid to dry for 10 min

Once dry store in cassette and the grid is ready to image with an electron microscope

4.4. CryoEM grid preparation protocol

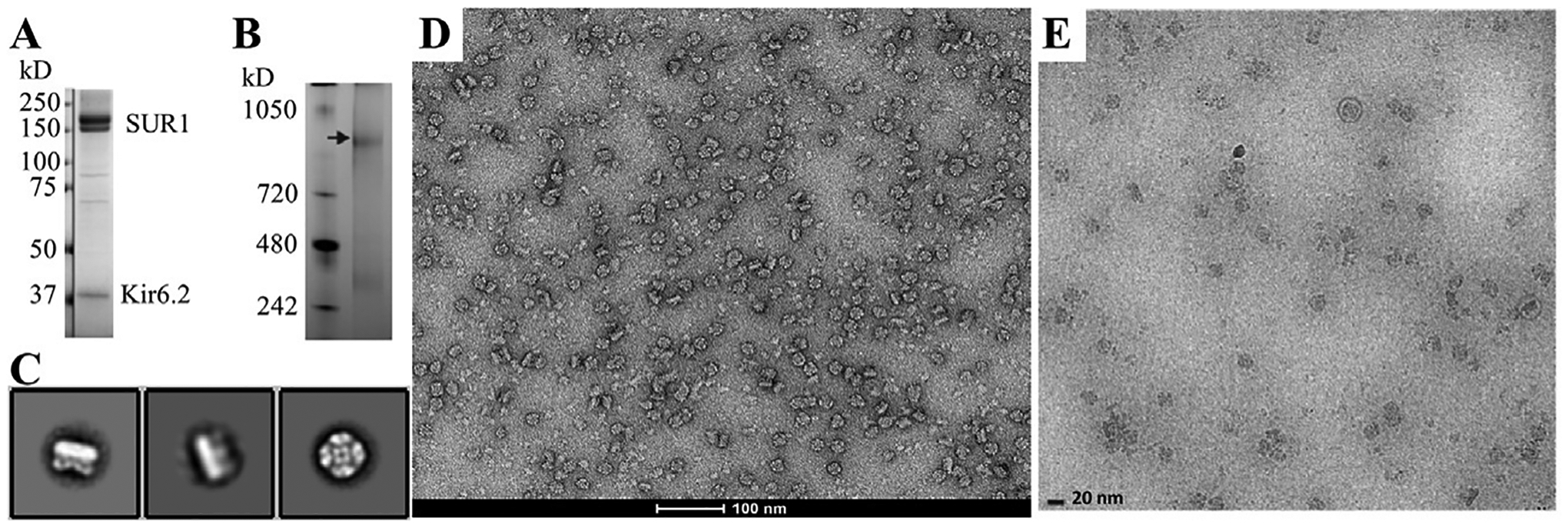

NOTE: Grid preparation for CryoEM is carried out using a Vitrobot, for which detailed operation instructions are available by the manufacturer. Clipping grids is also a well-established protocol not unique to KATP channel particles, and is not described here in detail. Typically we need to obtain sample that is 10 × more concentrated for CryoEM than for negative stain, but alternative grids and surfaces can be considered that may help to increase particle distribution (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of KATP channel post-purification by single particle imaging. (A) SDS PAGE gel of purified sample showing SUR1 (lower band: core-glycosylated and upper band: complex-glycosylated forms) and Kir6.2 as the dominant bands. (B) A blue native gel confirms the ~1 mDa (arrow) size of the (Kir6.2/SUR1)4 complex. Both of these gel images were published previously (Martin et al., 2017). (C) Two-dimensional class averages of negative-stained KATP channels with two side views (left) and one top/down view (right). (D) A representative negative stain micrograph at 68,000 × showing monodispersed KATP channel particles. (E) A typical cryoEM image of purified KATP channel sample on an UltrAuFoil grid used in our published studies to resolve the first Kir6.2/SUR1 structure (Martin, Yoshioka, et al., 2017). A top/down view and a side view particles are highlighted with red circles. Scale bar: 20 nm. Note the protein concentration used for negative stain was about 1/5–1/10 of that used for the cryoEM grids. Reproduced from Martin, G. M., Yoshioka, C., Rex, E. A., Fay, J. F., Xie, Q., Whorton, M. R. et al. (2017). Cryo-EM structure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel illuminates mechanisms of assembly and gating. eLife, 6. e24149. doi:10.7554/eLife.24149.

Day 2 (continued on same day as purification)

Place UltrAuFoil grids on slide or tray suitable for glow discharge

Glow discharge grids to make them hydrophilic (easiGlow™ 0.39 mBar, 15 mA, 30 s)

Load a grid into the Vitrobot, setting chamber to 100% humidity

Apply a 3 μL drop of purified KATP channel complex concentrated to ~1 mg/mL or ~1.1 μM, as determined appropriate by negative stain. Typically a CryoEM sample on grids without support requires a concentration about 10 times as that used for negative stain to have the same particle density

Incubate the purified KATP channel complex sample for 30s to 60s

Blot for 2s (Blot force −4; 100% humidity)

Cryo-plunge into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen

Clip grids, being careful to not thaw or the sample will be destroyed

Grids can be stored in liquid nitrogen until they can be imaged by a cryoEM microscope

5. Summary

The protocols presented in this chapter have yielded high quality monodispersed KATP channels for cryoEM structural studies (Fig. 3). To date, we have determined structures of the channel in the apo state, in the presence of ATP, and in the presence of ATP together with glibenclamide, repaglinide, or carbamazepine at 3.7–4.6 Å overall resolutions (Martin et al., 2016, 2019; Martin, Kandasamy, et al., 2017). These structures have revealed the three-dimensional architecture of the channel complex and the binding sites for glibenclamdie, repaglinide and carbamazepine, providing insights into the mechanisms of KATP pharmacological chaperones (Martin et al., 2019, 2020; Martin, Kandasamy, et al., 2017; Martin, Yoshioka, et al., 2017). From these structures, we learned that all three drugs share a common binding pocket in the transmembrane helix bundle above NBD1 (Fig. 1B), explaining how these diverse compounds have similar inhibitory and chaperoning effects on the channel. The structures show that SUR1-TMD0 is the primary domain that anchors SUR1 to Kir6.2, which explains why many trafficking mutations are found in TMD0. Importantly, in the drug-bound structures, we see that the distal N-terminus of Kir6.2 inserts into the central cavity formed by the two halves of the SUR1-ABC core, and may even participate in drug binding. This offers an explanation for why deletion of the Kir6.2 N-terminus diminishes the ability of the pharmacological chaperones to rescue trafficking mutants (Martin et al., 2020). Moreover, the observation suggests that interactions between the Kir6.2 N-terminus and the SUR1-ABC core, stabilized by drug binding, may provide a handle to allow mutant TMD0 to assemble with Kir6.2, thus rescuing TMD0 trafficking mutants out of the ER.

It is anticipated that with increased accessibility of cryoEM facilities, single-particle cryoEM will become a routine technique to study KATP channels. We hope that by sharing our expression and purification protocol, we will help accelerate the pace of KATP channel structure-function research and ultimately drive drug discovery to improve therapies for disease caused by channel dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

A portion of this research was supported by an R01 (R01 DK066485-13) to Show-Ling Shyng and an OHSU N. L. Tartar Trust Research Fellowship (2020 – 21) to Camden M. Driggers. A portion of this research was supported by NIH grant U24GM129547 and performed at the PNCC at OHSU and accessed through EMSL (grid.436923.9), a DOE Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. We would like to specifically thank Nancy Meyer at the PNCC and Steven Admanu for sharing their expertise in electron microscopy. We would also like to thank Min Woo Sung and Veronica Cochrane for critically reading this methods chapter, and Min Woo Sung and Zhongying Yang for sharing their technical expertise and everyone in the Shyng lab for useful discussions.

Abbreviations

- CBZ

carbamazepine

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CHI

congenital hyperinsulinism

- GBC

Glibenclamide

- HS

hypotonic solution

- KATP

ATP-sensitive potassium channel

- Kir6.2

inwardly rectifying potassium channel 6.2

- MSB

Membrane Solubilization Buffer

- NBD

nucleotide binding domain

- PNDM

permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus

- RPG

repaglinide

- SU

sulfonylureas

- SUR1

sulfonylurea receptor 1

- TMD

transmembrane domain

References

- Aguilar-Bryan L, & Bryan J (1999). Molecular biology of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Endocrine Reviews, 20(2), 101–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Clement J. P.t., Gonzalez G, Kunjilwar K, Babenko A, & Bryan J (1998). Toward understanding the assembly and structure of KATP channels. Physiological Reviews, 78(1), 227–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Nichols CG, Rajan AS, Parker C, & Bryan J (1992). Co-expression of sulfonylurea receptors and KATP channels in hamster insulinoma tumor (HIT) cells. Evidence for direct association of the receptor with the channel. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 267(21), 14934–14940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev AE, Kennedy ME, Navarro B, & Terzic A (1997). Burst kinetics of co-expressed Kir6.2/SUR1 clones: Comparison of recombinant with native ATP-sensitive K+ channel behavior. The Journal of Membrane Biology, 159(2), 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antcliff JF, Haider S, Proks P, Sansom MS, & Ashcroft FM (2005). Functional analysis of a structural model of the ATP-binding site of the KATP channel Kir6.2 subunit. The EMBO Journal, 24(2), 229–239. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM (2005). ATP-sensitive potassium channelopathies: Focus on insulin secretion. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 115(8), 2047–2058. 10.1172/JCI25495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Puljung MC, & Vedovato N (2017). Neonatal diabetes and the KATP channel: From mutation to therapy. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 28(5), 377–387. 10.1016/j.tem.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autzen HE, Julius D, & Cheng Y (2019). Membrane mimetic systems in CryoEM: Keeping membrane proteins in their native environment. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 58, 259–268. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko AP, & Bryan J (2003). Sur domains that associate with and gate KATP pores define a novel gatekeeper. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(43), 41577–41580. 10.1074/jbc.C300363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko AP, Gonzalez G, & Bryan J (1999). Two regions of sulfonylurea receptor specify the spontaneous bursting and ATP inhibition of KATP channel isoforms. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274(17), 11587–11592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Schulte U, Oliver D, Herlitze S, Krauter T, Tucker SJ, et al. (1998). PIP2 and PIP as determinants for ATP inhibition of KATP channels. Science, 282(5391), 1141–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branstrom R, Leibiger IB, Leibiger B, Corkey BE, Berggren PO, & Larsson O (1998). Long chain coenzyme A esters activate the pore-forming subunit (Kir6. 2) of the ATP-regulated potassium channel. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273(47), 31395–31400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier EA, Conti LR, Vandenberg CA, & Shyng SL (2001). Defective trafficking and function of KATP channels caused by a sulfonylurea receptor 1 mutation associated with persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98(5), 2882–2887. 10.1073/pnas.051499698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KW, Zhang H, & Logothetis DE (2003). N-terminal transmembrane domain of the SUR controls trafficking and gating of Kir6 channel subunits. The EMBO Journal, 22(15), 3833–3843. 10.1093/emboj/cdg376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PC, Bruederle CE, Gaisano HY, & Shyng SL (2011). Syntaxin 1A regulates surface expression of beta-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 300(3), C506–C516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PC, Olson EM, Zhou Q, Kryukova Y, Sampson HM, Thomas DY, et al. (2013). Carbamazepine as a novel small molecule corrector of trafficking-impaired ATP-sensitive potassium channels identified in congenital hyperinsulinism. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(29), 20942–20954. 10.1074/jbc.M113.470948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti LR, Radeke CM, & Vandenberg CA (2002). Membrane targeting of ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Effects of glycosylation on surface expression. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(28), 25416–25422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig TJ, Ashcroft FM, & Proks P (2008). How ATP inhibits the open K(ATP) channel. The Journal of General Physiology, 132(1), 131–144. 10.1085/jgp.200709874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane A, & Aguilar-Bryan L (2004). Assembly, maturation, and turnover of K(ATP) channel subunits. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(10), 9080–9090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukras CA, Jeliazkova I, & Nichols CG (2002a). The role of NH2-terminal positive charges in the activity of inward rectifier KATP channels. The Journal of General Physiology, 120(3), 437–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukras CA, Jeliazkova I, & Nichols CG (2002b). Structural and functional determinants of conserved lipid interaction domains of inward rectifying Kir6. 2 channels. The Journal of General Physiology, 119(6), 581–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wet H, Mikhailov MV, Fotinou C, Dreger M, Craig TJ, Venien-Bryan C, et al. (2007). Studies of the ATPase activity of the ABC protein SUR1. The FEBS Journal, 274(14), 3532–3544. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detimary P, Dejonghe S, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Schuit F, & Henquin JC (1998). The changes in adenine nucleotides measured in glucose-stimulated rodent islets occur in beta cells but not in alpha cells and are also observed in human islets. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273(51), 33905–33908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraneni PK, Martin GM, Olson EM, Zhou Q, & Shyng SL (2015). Structurally distinct ligands rescue biogenesis defects of the KATP channel complex via a converging mechanism. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290(12), 7980–7991. 10.1074/jbc.M114.634576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Wang M, Wu JX, Kang Y, & Chen L (2019). The structural basis for the binding of repaglinide to the pancreatic KATP channel. Cell Reports, 27(6), 1848–1857.e1844. S2211–1247(19)30523–6 [pii]. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drain P, Geng X, & Li L (2004). Concerted gating mechanism underlying KATP channel inhibition by ATP. Biophysical Journal, 86(4), 2101–2112. 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74269-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubochet J, Adrian M, Chang JJ, Homo JC, Lepault J, McDowall AW, et al. (1988). Cryo-electron microscopy of vitrified specimens. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics, 21(2), 129–228. 10.1017/s0033583500004297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkvetchakul D, Loussouarn G, Makhina E, Shyng SL, & Nichols CG (2000). The kinetic and physical basis of K(ATP) channel gating: Toward a unified molecular understanding. Biophysical Journal, 78(5), 2334–2348. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76779-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehring A, Lee CH, Wang KH, Michel JC, Claxton DP, Baconguis I, et al. (2014). Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nature Protocols, 9(11), 2574–2585. 10.1038/nprot.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, & Reimann F (2003). Sulphonylurea action revisited: The post-cloning era. Diabetologia, 46(7), 875–891. 10.1007/s00125-003-1143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, & Ashcroft FM (1997). The essential role of the Walker A motifs of SUR1 in K-ATP channel activation by Mg-ADP and diazoxide. The EMBO Journal, 16(6), 1145–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan JW, Sampson HM, & Thomas DY (2013). Novel pharmacological strategies to treat cystic fibrosis. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 34(2), 119–125. 10.1016/j.tips.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan JW, Sato Y, Carlile GW, Jansen G, Young JC, & Thomas DY (2019). Cystic fibrosis: Proteostatic correctors of CFTR trafficking and alternative therapeutic targets. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 23(8), 711–724. 10.1080/14728222.2019.1628948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, & Newgard CB (2000). Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes, 49(3), 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, et al. (1995). Reconstitution of IKATP: An inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science, 270(5239), 1166–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster JC, Sha Q, & Nichols CG (1999). Sulfonylurea and K(+)-channel opener sensitivity of K(ATP) channels. Functional coupling of Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits. The Journal of General Physiology, 114(2), 203–213. 10.1085/jgp.114.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KPK, Chen J, & MacKinnon R (2017). Molecular structure of human KATP in complex with ATP and ADP. eLife, 6, e32481. 10.7554/eLife.32481(pii] 32481 [pii). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Wu JX, Ding D, Cheng J, Gao N, & Chen L (2017). Structure of a pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Cell, 168(1–2), 101–110.e110. S0092–8674(16) 31744–5 [pii]. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmullen CM, Zhou Q, Snider KE, Tewson PH, Becker SA, Aziz AR, et al. (2011). Diazoxide-unresponsive congenital hyperinsulinism in children with dominant mutations of the beta-cell sulfonylurea receptor SUR1. Diabetes, 60(6), 1797–1804. 10.2337/db10-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markworth E, Schwanstecher C, & Schwanstecher M (2000). ATP4- mediates closure of pancreatic beta-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels by interaction with 1 of 4 identical sites. Diabetes, 49(9), 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Chen PC, Devaraneni P, & Shyng SL (2013). Pharmacological rescue of trafficking-impaired ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Frontiers in Physiology, 4, 386. 10.3389/fphys.2013.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Kandasamy B, DiMaio F, Yoshioka C, & Shyng SL (2017). Anti-diabetic drug binding site in a mammalian KATP channel revealed by Cryo-EM. eLife, 6, e31054. 10.7554/eLife.31054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Rex EA, Devaraneni P, Denton JS, Boodhansingh KE, DeLeon DD, et al. (2016). Pharmacological correction of trafficking defects in ATP-sensitive potassium channels caused by sulfonylurea receptor 1 mutations. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 291, 21971–21983. 10.1074/jbc.M116.749366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Sung MW, & Shyng SL (2020). Pharmacological chaperones of ATP-sensitive potassium channels: Mechanistic insight from cryoEM structures. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 502, 110667. 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Sung MW, Yang Z, Innes LM, Kandasamy B, David LL, et al. (2019). Mechanism of pharmacochaperoning in a mammalian KATP channel revealed by cryo-EM. eLife, 8, e46417. 10.7554/eLife.46417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Yoshioka C, Rex EA, Fay JF, Xie Q, Whorton MR, et al. (2017). Cryo-EM structure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel illuminates mechanisms of assembly and gating. eLife, 6, e24149. 10.7554/eLife.24149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masia R, Enkvetchakul D, & Nichols CG (2005). Differential nucleotide regulation of KATP channels by SUR1 and SUR2A. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 39(3), 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masia R, & Nichols CG (2008). Functional clustering of mutations in the dimer interface of the nucleotide binding folds of the sulfonylurea receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283(44), 30322–30329. 10.1074/jbc.M804318200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo M, Kimura Y, & Ueda K (2005). KATP channel interaction with adenine nucleotides. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 38(6), 907–916. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailov MV, Campbell JD, de Wet H, Shimomura K, Zadek B, Collins RF, et al. (2005). 3-D structural and functional characterization of the purified KATP channel complex Kir6.2-SUR1. The EMBO Journal, 24(23), 4166–4175. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG (2006). KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature, 440(7083), 470–476. 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson T, Schultz V, Berggren PO, Corkey BE, & Tornheim K (1996). Temporal patterns of changes in ATP/ADP ratio, glucose 6-phosphate and cytoplasmic free Ca2 + in glucose-stimulated pancreatic beta-cells. The Biochemical Journal, 314(Pt. 1), 91–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz D, Gossack L, Quast U, & Bryan J (2013). Reinterpreting the action of ATP analogs on K(ATP) channels. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(26), 18894–18902. 10.1074/jbc.M113.476887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge CJ, Beech DJ, & Sivaprasadarao A (2001). Identification and pharmacological correction of a membrane trafficking defect associated with a mutation in the sulfonylurea receptor causing familial hyperinsulinism. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(38), 35947–35952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipatpolkai T, Usher S, Stansfeld PJ, & Ashcroft FM (2020). New insights into KATP channel gene mutations and neonatal diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology, 16(7), 378–393. 10.1038/s41574-020-0351-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers ET, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW, & Balch WE (2009). Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 78, 959–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt EB, Tewson P, Bruederle CE, Skach WR, & Shyng SL (2011). N-terminal transmembrane domain of SUR1 controls gating of Kir6.2 by modulating channel sensitivity to PIP2. The Journal of General Physiology, 137(3), 299–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt EB, Yan FF, Gay JW, Stanley CA, & Shyng SL (2009). Sulfonylurea receptor 1 mutations that cause opposite insulin secretion defects with chemical chaperone exposure. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284(12), 7951–7959. 10.1074/jbc.M807012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt EB, Zhou Q, Gay JW, & Shyng SL (2012). Engineered interaction between SUR1 and Kir6.2 that enhances ATP sensitivity in KATP channels. The Journal of General Physiology, 140(2), 175–187. 10.1085/jgp.201210803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson HM, Lam H, Chen PC, Zhang D, Mottillo C, Mirza M, et al. (2013). Compounds that correct F508del-CFTR trafficking can also correct other protein trafficking diseases: An in vitro study using cell lines. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 8, 11. 10.1186/1750-1172-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach B, Zerangue N, Jan YN, & Jan LY (2000). Molecular basis for K(ATP) assembly: Transmembrane interactions mediate association of a K+ channel with an ABC transporter. Neuron, 26(1), 155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng SL, Cukras CA, Harwood J, & Nichols CG (2000). Structural determinants of PIP(2) regulation of inward rectifier K(ATP) channels. The Journal of General Physiology, 116(5), 599–608. 10.1085/jgp.116.5.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng SL, & Nichols CG (1998). Membrane phospholipid control of nucleotide sensitivity of KATP channels. Science, 282(5391), 1138–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley CA (1997). Hyperinsulinism in infants and children. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 44(2), 363–374. 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja TK, Mankouri J, Karnik R, Kannan S, Smith AJ, Munsey T, et al. (2009). Sar1-GTPase-dependent ER exit of KATP channels revealed by a mutation causing congenital hyperinsulinism. Human Molecular Genetics, 18(13), 2400–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov A, Dusonchet J, & Ashcroft F (2004). Metabolic regulation of the pancreatic beta-cell ATP-sensitive K+ channel: A pas de deux. Diabetes, 53(Suppl. 3), S113–S122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschenberger G, Mougey A, Shen S, Lester LB, LaFranchi S, & Shyng SL (2002). Identification of a familial hyperinsulinism-causing mutation in the sulfonylurea receptor 1 that prevents normal trafficking and function of KATP channels. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(19), 17139–17146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Aller SG, Beis K, Carpenter EP, Chang G, Chen L, et al. (2020). Structural and functional diversity calls for a new classification of ABC transporters. FEBS Letters, 594, 3767–3775. 10.1002/1873-3468.13935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, & Ashcroft FM (1997). Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature, 387(6629), 179–183. 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher SG, Ashcroft FM, & Puljung MC (2020). Nucleotide inhibition of the pancreatic ATP-sensitive K+ channel explored with patch-clamp fluorometry. eLife, 9, e52775. 10.7554/eLife.52775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JX, Ding D, Wang M, Kang Y, Zeng X, & Chen L (2018). Ligand binding and conformational changes of SUR1 subunit in pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Protein & Cell, 9(6), 553–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-018-0530-y. 10.1007/s13238-018-0530-y [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Lin CW, Weisiger E, Cartier EA, Taschenberger G, & Shyng SL (2004). Sulfonylureas correct trafficking defects of ATP-sensitive potassium channels caused by mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(12), 11096–11105. 10.1074/jbc.M312810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan FF, Casey J, & Shyng SL (2006). Sulfonylureas correct trafficking defects of disease-causing ATP-sensitive potassium channels by binding to the channel complex. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 281(44), 33403–33413. 10.1074/jbc.M605195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan FF, Lin CW, Cartier EA, & Shyng SL (2005). Role of ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway in biogenesis efficiency of {beta}-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 289(5), C1351–C1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan FF, Lin YW, MacMullen C, Ganguly A, Stanley CA, & Shyng SL (2007). Congenital hyperinsulinism associated ABCC8 mutations that cause defective trafficking of ATP-sensitive K+ channels: Identification and rescue. Diabetes, 56(9), 2339–2348. 10.2337/db07-0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan FF, Pratt EB, Chen PC, Wang F, Skach WR, David LL, et al. (2010). Role of Hsp90 in biogenesis of the beta-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channel complex. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 21(12), 1945–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN, & Jan LY (1999). A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane K(ATP) channels. Neuron, 22(3), 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingman LV, Alekseev AE, Bienengraeber M, Hodgson D, Karger AB, Dzeja PP, et al. (2001). Signaling in channel/enzyme multimers: ATPase transitions in SUR module gate ATP-sensitive K+ conductance. Neuron, 31(2), 233–245. 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]