Abstract

Background

Honey is a viscous, supersaturated sugar solution derived from nectar gathered and modified by the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Honey has been used since ancient times as a remedy in wound care. Evidence from animal studies and some trials has suggested that honey may accelerate wound healing.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of honey compared with alternative wound dressings and topical treatments on the of healing of acute (e.g. burns, lacerations) and/or chronic (e.g. venous ulcers) wounds.

Search methods

For this update of the review we searched the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 15 October 2014); The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 9); Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to October Week 1 2014); Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations 13 October 2014); Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 13 October 2014); and EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 15 October 2014).

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials that evaluated honey as a treatment for any sort of acute or chronic wound were sought. There was no restriction in terms of source, date of publication or language. Wound healing was the primary endpoint.

Data collection and analysis

Data from eligible trials were extracted and summarised by one review author, using a data extraction sheet, and independently verified by a second review author. All data have been subsequently checked by two more authors.

Main results

We identified 26 eligible trials (total of 3011 participants). Three trials evaluated the effects of honey in minor acute wounds, 11 trials evaluated honey in burns, 10 trials recruited people with different chronic wounds including two in people with venous leg ulcers, two trials in people with diabetic foot ulcers and single trials in infected post‐operative wounds, pressure injuries, cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Fournier's gangrene. Two trials recruited a mixed population of people with acute and chronic wounds. The quality of the evidence varied between different comparisons and outcomes. We mainly downgraded the quality of evidence for risk of bias, imprecision and, in a few cases, inconsistency.

There is high quality evidence (2 trials, n=992) that honey dressings heal partial thickness burns more quickly than conventional dressings (WMD ‐4.68 days, 95%CI ‐5.09 to ‐4.28) but it is unclear if there is a difference in rates of adverse events (very low quality evidence) or infection (low quality evidence).

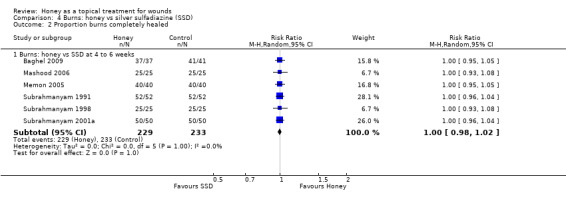

There is very low quality evidence (4 trials, n=332) that burns treated with honey heal more quickly than those treated with silver sulfadiazine (SSD) (WMD ‐5.12 days, 95%CI ‐9.51 to ‐0.73) and high quality evidence from 6 trials (n=462) that there is no difference in overall risk of healing within 6 weeks for honey compared with SSD (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.02) but a reduction in the overall risk of adverse events with honey relative to SSD. There is low quality evidence (1 trial, n=50) that early excision and grafting heals partial and full thickness burns more quickly than honey followed by grafting as necessary (WMD 13.6 days, 95%CI 9.82 to 17.38).

There is low quality evidence (2 trials, different comparators, n=140) that honey heals a mixed population of acute and chronic wounds more quickly than SSD or sugar dressings.

Honey healed infected post‐operative wounds more quickly than antiseptic washes followed by gauze and was associated with fewer adverse events (1 trial, n=50, moderate quality evidence, RR of healing 1.69, 95%CI 1.10 to 2.61); healed pressure ulcers more quickly than saline soaks (1 trial, n= 40, very low quality evidence, RR 1.41, 95%CI 1.05 to 1.90), and healed Fournier’s gangrene more quickly than Eusol soaks (1 trial, n=30, very low quality evidence, WMD ‐8.00 days, 95%CI ‐6.08 to ‐9.92 days).

The effects of honey relative to comparators are unclear for: venous leg ulcers (2 trials, n= 476, low quality evidence); minor acute wounds (3 trials, n=213, very low quality evidence); diabetic foot ulcers (2 trials, n=93, low quality evidence); Leishmaniasis (1 trial, n=100, low quality evidence); mixed chronic wounds (2 trials, n=150, low quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

It is difficult to draw overall conclusions regarding the effects of honey as a topical treatment for wounds due to the heterogeneous nature of the patient populations and comparators studied and the mostly low quality of the evidence. The quality of the evidence was mainly downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision. Honey appears to heal partial thickness burns more quickly than conventional treatment (which included polyurethane film, paraffin gauze, soframycin‐impregnated gauze, sterile linen and leaving the burns exposed) and infected post‐operative wounds more quickly than antiseptics and gauze. Beyond these comparisons any evidence for differences in the effects of honey and comparators is of low or very low quality and does not form a robust basis for decision making.

Keywords: Humans; Honey; Wound Healing; Administration, Topical; Apitherapy; Apitherapy/methods; Burns; Burns/therapy; Leg Ulcer; Leg Ulcer/therapy; Pressure Ulcer; Pressure Ulcer/therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Surgical Wound Infection; Surgical Wound Infection/therapy; Varicose Ulcer; Varicose Ulcer/therapy; Wounds and Injuries; Wounds and Injuries/therapy

Plain language summary

Honey as a topical treatment for acute and chronic wounds

We reviewed the evidence about the effects of applying honey on the healing of any kind of wound. We found 26 studies involving 3011 people with many different kinds of wounds. Honey was compared with many different treatments in the included studies.

The differences in wound types and comparators make it impossible to draw overall conclusions about the effects of honey on wound healing. The evidence for most comparisons is low or very low quality. This was largely because we thought that problems with the design of some of the studies made their results unreliable and for many outcomes there was only a small amount of information available. In some cases the results of the studies varied considerably.

There is high quality evidence that honey heals partial thickness burns around 4 to 5 days more quickly than conventional dressings. There is moderate quality evidence that honey is more effective than antiseptic followed by gauze for healing wounds infected after surgical operations.

It is not clear if honey is better or worse than other treatments for burns, mixed acute and chronic wounds, pressure ulcers, Fournier's gangrene, venous leg ulcers, minor acute wounds, diabetic foot ulcers and Leishmaniasis as most of the evidence that exists is of low or very low quality.

This evidence is current up to October 2014.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Honey compared with conventional dressings for minor acute wounds.

| Honey compared with conventional dressings for minor acute wounds | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Minor acute wounds Settings: Any Intervention: Honey Comparison: Conventional dressings | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Conventional dressings | Honey | |||||

| Complete healing (time to healing)(days) | The mean complete healing (time to healing) in the intervention groups was 2.26 higher (3.09 lower to 7.61 higher) | 213 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| Adverse events | Study population | RR 1.19 (0.69 to 2.05) | 82 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 | ||

| 357 per 1000 | 425 per 1000 (246 to 732) | |||||

| Infection | Study population | RR 0.91 (0.13 to 6.37) | 151 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,5 | ||

| 14 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (2 to 88) | |||||

| Costs Average dressing cost per patient | The mean cost of dressing materials per patient was 0.49 ZAR in the honey group and 12.06 ZAR in the control (hydrogel) group |

82 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low7,8,9 | |||

| Quality of Life6 | Not reported | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded due to risk of bias (one level): High risk of attrition bias in all three included studies 2 Downgraded due to inconsistency (one level): the patient populations and comparator interventions differed between the studies 3 Downgraded due to imprecision (two levels): The plausible range of effects extends from a three day reduction in healing time with honey up to a more than seven day extension in healing time 4 Downgraded due to imprecision (two levels): The 95% confidence interval ranges from 0.69 and 2.05 5 Downgraded due to imprecision (two levels): The relative risk of infection for honey‐treated wounds compared with conventional dressings lies somewhere between 0.13 and 6.37 6 None of the studies reported quality of life 7 ITT analysis not done; cost data from withdrawn patients not included 8 Only report cost of dressing material not other related costs e.g., nursing care, other treatments 9 Only one small study reported costs: honey a non‐proprietary product in this study

Summary of findings 2. Honey compared with conventional dressings for burns.

| Honey compared with conventional dressings for burns | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Burns Settings: Any Intervention: Honey Comparison: conventional dressings | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Conventional dressings | Honey | |||||

| Complete healing (time to healing)(days) Mean time to healing Follow‐up: median 4 weeks | The mean complete healing (time to healing) in the intervention groups was 4.68 lower (5.09 to 4.28 lower) | 992 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: median 4 weeks | Study population | RR 0.56 (0.15 to 2.06) | 992 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 206 per 1000 | 115 per 1000 (31 to 424) | |||||

| Negative wound swab Follow‐up: median 8 days | Study population | RR 1.31 (1.01 to 1.7) | 92 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | ||

| 630 per 1000 | 826 per 1000 (637 to 1000) | |||||

| Costs5 | Not reported | Not estimable5 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Quality of life5 | Not reported | Not estimable5 | N/A | N/A | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded due to inconsistency (one level): High heterogeneity was detected with an I‐squared of 70% 2 Downgraded due to imprecision (two levels): The 95% confidence interval ranges from 0.15 to 2.06 3 Downgraded due to indirectness (one level). The outcome of a negative wound swab at 8 days is only a proxy for clinical infection and difficult to interpret 4 Downgraded for imprecision (two levels): this outcome is only reported for one study involving 92 participants 5 Neither study reported costs or quality of life

Summary of findings 3. Honey compared with silver sulfadiazine for burns.

| Honey compared with silver sulfadiazine for burns | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Burns Settings: Any Intervention: Honey Comparison: Silver sulfadiazine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Silver sulfadiazine | Honey | |||||

| Complete healing Follow‐up: 4‐6 weeks | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 462 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 1000 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (980 to 1000) | |||||

| Mean time to complete healing (days) Follow‐up: 21‐60 days | The mean time to complete healing in the intervention groups was 5.12 lower (9.51 to 0.73 lower) | 332 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 4‐6 weeks | Study population | RR 0.29 (0.2 to 0.42) | 412 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 413 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 (83 to 174) | |||||

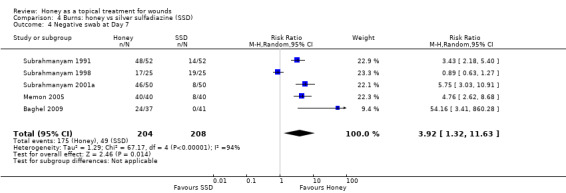

| Negative wound swab Follow‐up: median 7 days | Study population | RR 3.92 (1.32 to 11.63) | 412 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,5 | ||

| 236 per 1000 | 923 per 1000 (311 to 1000) | |||||

| Costs Cost of dressing per percent TBSA affected | The cost of dressing treatment per % TBSA affected was 0.75 PKR for honey and 10 PKR for silver sulfadiazine. | 50 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7,8 | |||

| Quality of Life6 | Not reported | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded due to inconsistency (two levels): Very high level of statistical heterogeneity (I squared of 93%) 2 Downgraded due to imprecision (one level): Although the direction of effect is consistently in favour of honey, the confidence interval around the mean difference ranges from a reduction in healing time of less than one day up to nearly 10 days 3 Downgraded two levels due to inconsistency: Very high level of statistical heterogeneity (I squared of 94%) 4 Downgraded due to indirectness (one level) since the outcome of a negative wound swab at 7 days is only an indirect measure of wound infection. 5 Downgraded due to imprecision (one level): The risk of a negative swab at 7 days favour honey however the confidence interval is extremely wide 6 Quality of life not reported in any of the studies 7 Only cost of dressing materials reported not other associated health care costs 8 Only one small study reported cost of materials

Summary of findings 4. Honey for venous leg ulcers.

| Honey for venous leg ulcers | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Venous leg ulcers Settings: Any Intervention: Honey | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Honey | |||||

| Complete healing (time to healing) Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Study population | HR 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 368 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 497 per 1000 | 531 per 1000 (423 to 644) | |||||

| Complete healing (proportion wounds healed) | Study population | RR 1.15 (0.96 to 1.38) | 476 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| 460 per 1000 | 529 per 1000 (441 to 634) | |||||

| Adverse events | Study population | RR 1.28 (1.05 to 1.56) | 368 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,5 | ||

| 464 per 1000 | 594 per 1000 (487 to 724) | |||||

| Infection Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.49 to 1.04) | 476 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | ||

| 221 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (108 to 230) | |||||

| Costs Incremental cost effectiveness ratio Follow‐up: 12 weeks | The mean cost in the intervention group was 9.45 NZD lower (95%CI 39.63 NZD lower to 16.07 NZD higher)7 | 368 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low8,9 | The ICER was sensitive to the inclusion of hospitalisation costs. Hospitalisation unlikely related to treatment and when these were excluded the ICER was in favour of control. |

||

| Quality of Life SF‐36 PCS Follow‐up: 12 weeks | The mean PCS in the intervention group was 1.1 higher (95% CI 0.8 lower to 3 higher) | 368 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate10 | |||

| Quality of Life SF‐36 MCS Follow‐up: 12 weeks | The mean MCS in the intervention groups was 0.7 higher (95% CI 1.1 lower to 2.4 higher) | 368 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate10 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded due to risk of bias (one level): Unblinded outcome assessment 2 Downgraded due to imprecision (one level): The confidence interval around the estimate of the hazard ratio ranges from a 20% reduction to a 50% increase in the hazard for healing with honey 3 Downgraded due to risk of bias (one level): Neither study used blinded outcome assessment 4 Downgraded due to imprecision (one level): The result is consistent with there being no important difference between the dressings up to honey increasing the risk of healing by just over a third 5 Downgraded due to imprecision (one level): Wide confidence intervals; only one study 6 Downgraded due to risk of bias (two levels): The diagnosis of infection is partly subjective: both trials were open label 7 Including hospitalisation costs (and $11.34 (‐$2.24 to $26.25) in favour of usual care when hospitalisation costs excluded. 8 Large difference in rates of hospitalisations and therefore associated costs between arms unlikely to be related to treatments. ICER sensitive to inclusion/exclusion of hospitalisation costs 9 Large uncertainty on cost data 10 Patients not blinded to treatment

Background

Description of the condition

Acute and chronic wounds are terms in regular use in clinical practice, yet definition of these terms has received little attention. Lazarus 1994 suggested acute wounds proceed through to healing "in an orderly and timely reparative process". Orderliness refers to the healing sequence of inflammation, angiogenesis, matrix deposition, wound contraction, epithelialisation, and scar remodelling. Timeliness is subjective, but refers to a healing time that could be reasonably expected. A chronic wound is, therefore, a wound where the orderly biological progression to healing has been disrupted and healing is delayed.

Description of the intervention

Honey is a viscous, supersaturated sugar solution derived from nectar gathered and modified by the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Honey contains approximately 30% glucose, 40% fructose, 5% sucrose, and 20% water, as well as many other substances, such as amino acids, vitamins, minerals and enzymes (Sato 2000). Honey has been used in wound care since ancient times and is frequently mentioned in early pharmacopeia, although more usually as an ingredient or carrier vehicle rather than a specific treatment. Dioscorides (40‐80 CE) often mentioned honey as a vehicle for carrying therapeutic agents in de materia medicis (Riddle 1985), and Hippocrates (460‐377 BCE), who is often cited as advocating honey for wound care, simply listed it as one of many ingredients in a multitude of unguents (Adams 1939). Probably the first deliberate advocacy of honey as a wound treatment was by the anonymous author of the Edwin Smith papyrus, an Egyptian surgical text written between 2600‐2200 BCE (Breasted 1930). A dressing made from honey and plant material was also recommended for treating burns in the London Medical Papyrus written around 1325 BCE (Trevisanato 2006). Other early medical customs, including Ayurvedic (Johnson 1992), Chinese (Fu 2001) and Roman traditions (Hajar 2002), also used honey in wound care.

How the intervention might work

Between 1996 and 2006 there was a surge in interest about honey as a wound treatment, with 40 case reports or series in 875 patients published (Jull 2008). Recent research has tended to concentrate on the antibacterial activity of the many different types of honey, rather than its effect on wound healing (Molan 1999). Manuka honey, a monofloral honey derived from the Leptospermum tree in New Zealand and Australia, has been of particular interest, as it has antibacterial activity independent of the effect of honey's peroxide activity and osmolarity (Molan 2001). The substance (or substances) responsible for this non‐peroxide activity has not been definitively identified, but has been termed Unique Manuka Factor (UMF). Manuka honey with a UMF rating has an antibacterial activity equivalent to a similar percentage of phenolic acid in solution. Recent research suggests methylglyoxal is the substance responsible for the non‐peroxide activity (Mavric 2008).

There is evidence from different animal models that honey may accelerate healing (Bergman 1983; Oryan 1998; Postmes 1997). Fifteen of the 16 controlled trials in five different animal models (mice, rat, rabbit, pig, and buffalo calf) found that honey‐treated incisional and excisional wounds, and standard burns, healed faster than control wounds (Jull 2008). In addition, a systematic review of honey as a wound dressing found seven randomised trials in humans, six in burns patients and one in infected post‐operative wounds (Moore 2001). Although the poor quality of the trial reports prevented any recommendations, the findings did suggest an effect in favour of honey.

Honey may exert multiple microscopic actions on wounds. It appears to draw fluid from the underlying circulation, providing both a moist environment and topical nutrition that may enhance tissue growth (Molan 1999). Histologically, honey appears to stimulate tissue growth in animal and human controlled trials, with earlier tissue repair noted (Bergman 1983; Subrahmanyam 1998), fewer inflammatory changes (Oryan 1998; Postmes 1997), and improved epithelialisation (Oryan 1998). Macroscopically, reports have also noted the debriding action of honey (Blomfield 1973; Efem 1988; Ndayisaba 1993; Subrahmanyam 1991).

Why it is important to do this review

Honey dressings are widely available and promoted as effective wound treatments. A systematic review of the evidence is therefore warranted as a basis for clinical and policy decision making. This version comprises a substantive update.

Objectives

To assess the effects of honey compared with alternative wound dressings and topical treatments on the healing of acute (e.g. burns, lacerations) and/or chronic (e.g. venous ulcers) wounds.

The publication of the first version of this review (Jull 2008a) was preceded by a published protocol (Jull 2004).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials were included. Quasi‐randomised controlled trials are trials which use a quasi‐random allocation strategy, such as alternate days, date of birth, or hospital number.

Types of participants

Trials involving participants of any age with an acute or chronic wound were included. For the purposes of this review an acute wound was considered to be any of the following: burns, lacerations or other skin injuries resulting from minor trauma, and minor surgical wounds healing by primary or secondary intention. Chronic wounds were considered to be: skin ulcers of any type, pressure ulcers and infected wounds healing by secondary intention.

Types of interventions

The primary intervention was any formulation of honey topically applied by any means, alone or in combination with other dressings or components, to an acute or chronic wound. Eligible comparison interventions were dressings or other topical agents applied to the wound.

Types of outcome measures

Trials had to provide data on one of the primary outcomes listed below, and the unit of analysis had to be by participant (See "Differences between protocol and review" for further information about unit of analysis issues).

Primary outcomes

Time to complete wound healing;

proportion of participants with completely healed wounds.

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of adverse events;

length of hospital stay;

change in wound size:

incidence of infection;

cost;

quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For the search methods used in the original version of this review see Appendix 1.

For this second update we searched the following databases for reports of eligible randomised controlled trials:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 15 October 2014);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 9);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to October Week 1 2014);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations 13 October, 2014);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 13 October, 2014);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 15 October, 2014).

The following search strategy was used in CENTRAL and adapted appropriately for other databases:

#1 MeSH descriptor Skin Ulcer explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Pilonidal Sinus explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Wounds, Penetrating explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor Lacerations explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor Burns explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor Wound Infection explode all trees #7 MeSH descriptor Surgical Wound Dehiscence explode all trees #8 MeSH descriptor Bites and Stings explode all trees #9 MeSH descriptor Cicatrix explode all trees #10 ((plantar or diabetic or heel* or foot or feet or ischaemic or ischemic or venous or varicose or stasis or arterial or decubitus or pressure or skin or leg or mixed or tropical or rheumatoid or sickle cell) NEAR/5 (wound* or ulcer*)):ti,ab,kw #11 (bedsore* or (bed NEXT sore*)):ti,ab,kw #12 (pilonidal sinus* or pilonidal cyst*):ti,ab,kw #13 (cavity wound* or sinus wound*):ti,ab,kw #14 (laceration* or gunshot stab or stabbing or stabbed or bite*):ti,ab,kw #15 ("burn" or "burns" or "burned" or scald*):ti,ab,kw #16 (surg* NEAR/5 infection*):ti,ab,kw #17 (surg* NEAR/5 wound*):ti,ab,kw #18 (wound* NEAR/5 infection*):ti,ab,kw #19 (malignant wound* or experimental wound* or traumatic wound*):ti,ab,kw #20 (infusion site* or donor site* or wound site* or surgical site*):ti,ab,kw #21 (skin abscess* or skin abcess*):ti,ab,kw #22 (hypertrophic scar* or keloid*):ti,ab,kw #23 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22) #24 MeSH descriptor Honey explode all trees #25 honey:ti,ab,kw #26 (#24 OR #25) #27 (#23 AND #26)

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 2. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). The Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL searches were combined with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (SIGN 2008). There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication (taking into account searches from the original review) or study setting.

Searching other resources

For the initial review we contacted experts in the field, authors of the included trials and manufacturers of honey products for wound care (Comvita NZ Ltd and MediHoney Australia Pty Ltd), but did not repeat this for updates. The bibliographies of all obtained studies and review articles were searched for potentially eligible trials for both the initial review and the first update. No language or date restrictions were applied to the trials and both published and unpublished trials were sought.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (either AJ and NW, or for this update JD and NC) independently examined titles and abstracts of potentially relevant trials. Full text copies of all relevant trials, or trials that might be relevant to the review were obtained. The two review authors independently selected the trials using the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted from included trials by one review author and recorded on a standardised form. The extracted data were independently reviewed for accuracy by a second review author and disagreements resolved by discussion. All data have subsequently been verified by a third (MW) and fourth author (NC). If the data from the trial report were inadequate, or ambiguous, additional information was sought from the trial authors. We collected data on the topics listed below:

Author; title; source of reference.

Study setting.

Study design.

A priori sample size calculation; sample size.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Age of participants; sex of participants.

Wound type.

Intervention and comparison.

Outcomes.

Withdrawals and reason for withdrawal.

Funding source.

Co‐interventions

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the first update, one review author (SD) assessed each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011), and this assessment was checked by a second (AJ) review author. For this second update two more pairs of review authors/editors checked risk of bias (either MW and JD or JD and NC) and reviewed by the lead review author (AJ). This tool addresses six specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues, such as extreme baseline imbalance (see Appendix 3 for details of criteria on which the judgement was based). Blinding and completeness of outcome data were assessed for each outcome separately. We completed a risk of bias table for each eligible study and discussed any disagreement amongst all review authors to achieve a consensus.

We present an assessment of risk of bias using a 'risk of bias summary figure', which presents all of the judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by entry. This display of internal validity indicates the weight the reader may give the results of each study.

Data synthesis

Where trials were sufficiently alike in terms of population and comparison interventions, their results were combined. Mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported for continuous outcomes, and risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported for dichotomous variables. Statistical heterogeneity was tested by comparing Cochran's Q statistic and the chi‐squared distribution. Heterogeneity was assumed with P values of less than 0.1 (Higgins 2011). In addition, the I2 statistic was used to determine the percentage of variation due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003), and any sources of heterogeneity were explored. Where significant statistical heterogeneity was present, a random‐effects model was used when combining trials (Ioannidis 2008).

Summary of findings

The evidence was summarised in summary of findings tables using the approach of the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE Working Group) (Langendam 2013). This approach assesses the quality of the body of evidence per comparison and outcome, taking into account five factors: risk of bias across all studies reporting that outcome; indirectness of population, interventions and outcomes, across all studies reporting the outcome; inconsistency amongst studies; imprecision (taking into account the optimum information size and the confidence intervals) and publication bias. The results are reported below according to condition, comparison and outcome and then the different outcomes are brought together in summary of findings tables (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4), which are discussed in the final section (Discussion).

Results

Description of studies

Included studies

Twenty six trials met the inclusion criteria (please see the Characteristics of included studies) and were available for analysis; eight trials were added in updates (Baghel 2009; Gulati 2014; Kamaratos 2014; Mashood 2006; Memon 2005; Nilforoushzadeh 2007; Robson 2009; Shukrimi 2008), including one trial that was mistakenly excluded in the previous review, but was found in the first update to meet the inclusion criteria on re‐screening (Mashood 2006). Another trial was previously wrongly included and has now been excluded in this update (Subrahmanyam 1996c). Three trials are awaiting assessment while attempts are made to contact the authors to request further data (Askarpour 2009; Jan 2012; Maghsoudi 2011).

Ten separate trials were conducted by the same investigator (Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1993a; Subrahmanyam 1993b; Subrahmanyam 1994; Subrahmanyam 1996a; Subrahmanyam 1996b; Subrahmanyam 1998; Subrahmanyam 1999; Subrahmanyam 2001a; Subrahmanyam 2004) based in India. Important information was missing from the published reports of these studies however some was provided on request.

Fourteen trials recruited participants with acute wounds: 11 with burns (Baghel 2009; Mashood 2006; Memon 2005; Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1993b; Subrahmanyam 1994; Subrahmanyam 1996a; Subrahmanyam 1996b; Subrahmanyam 1998; Subrahmanyam 1999; Subrahmanyam 2001a), two with minor surgical excisions (Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006), and one with minor trauma (Ingle 2006). Ten trials recruited participants with chronic wounds including venous leg ulcers (Jull 2008; Gethin 2007), infected surgical wounds (Al Waili 1999), pressure injuries (Weheida 1991), Fournier's gangrene (Subrahmanyam 2004), cutaneous Leishmaniasis (ulcers caused by protozoans injected by sandfly bite) (Nilforoushzadeh 2007), diabetic foot ulcers (Kamaratos 2014; Shukrimi 2008), and a variety of chronic wounds healing by secondary intention though mainly venous leg ulcers (Gulati 2014; Robson 2009). Two trials recruited participants with either chronic or acute wounds (Mphande 2007; Subrahmanyam 1993a).

Eight trials were conducted in community settings or outpatient clinics (Gulati 2014; Kamaratos 2014; Gethin 2007; Ingle 2006; Jull 2008; Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006; Nilforoushzadeh 2007). The remaining trials were conducted in hospital settings, or a mixed inpatient and outpatient setting (Robson 2009). Eight trials reported recruiting only adults (Al Waili 1999; Gulati 2014; Gethin 2007; Ingle 2006; Jull 2008; Kamaratos 2014; Shukrimi 2008; Subrahmanyam 2004). The remaining trials did not specify an age range (Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006; Robson 2009), or recruited both children and adults.

Monofloral honey (aloe, jarrah, jamun, jambhul or manuka) was used in ten trials (Gethin 2007; Gulati 2014; Ingle 2006; Jull 2008; Kamaratos 2014; Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006; Robson 2009; Subrahmanyam 2001a; Subrahmanyam 2004); the type of honey used was not specified in the remaining trials. Honey was delivered as a honey impregnated gauze dressing in six trials (Kamaratos 2014; Mphande 2007; Nilforoushzadeh 2007; Subrahmanyam 1993a; Subrahmanyam 1994; Subrahmanyam 2004); as a honey impregnated alginate dressing in two (Jull 2008; McIntosh 2006); as honey spread between gauze in one trial (Memon 2005) and as topical honey covered with either a film dressing (Ingle 2006; Gulati 2014) or with gauze in the remaining trials. Six trials investigated honey as an adjunct treatment: four included people with venous leg ulcers, and, for these, honey was used as an adjunct to compression (Gethin 2007; Gulati 2014; Jull 2008; Robson 2009). One trial in people with Leishmaniasis gave honey alongside an injection of glucantamine (Nilforoushzadeh 2007). In a further trial, 50% patients receiving honey also received delayed autologous skin grafting, as necessary (Subrahmanyam 1999).

There was a range of comparison treatments in this review, which have been grouped under the broad categories of conventional dressings, silver sulfadiazine (SSD), antiseptics, early excision and atypical dressings. Seven trials compared honey with SSD, and of these, the comparator was a SSD impregnated dressing in four trials (Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1993b; Subrahmanyam 1998; Subrahmanyam 2001a) and SSD cream in three (Baghel 2009; Mashood 2006; Memon 2005). Two studies compared honey with hydrogel (Gethin 2007; Ingle 2006). In the adjunct trials, the comparators were either other dressings plus compression (Gethin 2007; Gulati 2014; Jull 2008; Robson 2009) or glucantamine injection alone (Nilforoushzadeh 2007). The comparator for the trial giving honey plus delayed skin grafting was early tangential excision and skin grafting (Subrahmanyam 1999).

In view of the clinical diversity of the evidence, this review is organised by wound type, and then by comparison type.

There was a great deal of variation in the outcomes reported by the included studies which makes the drawing of overall conclusions very difficult. Many of the included studies report "mean time to healing" but it was frequently not clear whether every participant's wound had healed during follow up (in which case the mean time with associated SD or 95% confidence interval would be acceptable). However if all wounds in a study do not heal during the period of observation, simple calculation of the mean (or median) time to healing without accounting for censoring is inappropriate since, by definition, this approach excludes people who did not heal during follow up (as they cannot contribute to the numerator). Importantly excluding people who failed to heal from the data excludes treatment failures and will over‐estimate treatment success. Time to healing is a type of "time to event" outcome and should be analysed as such using a survival approach which allows people who did not heal to contribute data to the analysis for the period for which they were observed. Only three studies (Jull 2008; Nilforoushzadeh 2007; Robson 2009) analysed time to healing as time to event data. One study (Shukrimi 2008) reported time to readiness for wound closure surgery.

The multiplicity of time points at which healing was reported was a further problem which had not been anticipated in the protocol. We opted to analyse the outcomes for the longest point of follow up shared by several trials of the same comparison (since to extract and analyse all time points risks a Type I error).

Excluded studies

For details on the excluded studies please see Characteristics of excluded studies table. Of the 57 excluded studies, 24 were not RCTs or quasi‐RCTs (Abdelatif 2008; Ahmed 2003; Al Waili 2004c; Al Waili 2005; Bose 1982; Dunford 2004; Freeman 2010; Gethin 2005; Lusby 2002; Marshall 2002; Mayer 2014; Misirligou 2003; Moghazy 2010; Molan 2002; Molan 2006; Mwipatayi 2004; Nagane 2004; Robson 2002; Schumacher 2004; Subrahmanyam 1993; Thurnheer 1983; Tostes 1994; Vijaya 2012; Visscher 1996). Seven of the excluded studies were not in wounds (Al Waili 2003; Albietz 2006; Biswal 2003; Johnson 2005; Quadri 1998; Quadri 1999; Somaratne 2012). Three were studies in animal models (Al Waili 2004a; Al Waili 2004b; Subrahmanyam 2001b). Thirteen studies did not report sufficient information on healing (Bangroo 2005; Chokotho 2005; Gad 1988; Heidari 2013; Jeffery 2008; Lund‐Nielsen 2011; Mat Lazim 2013; Robson 2012; Rogers 2010; Rucigaj 2006; Saha 2012; Subrahmanyam 2003; Ur‐Rehman 2013). Three studies did not evaluate honey (Berchtold 1992; Muller 1985), one evaluated the effect of adding vitamins and polyethylene glycol to honey (Subrahmanyam 1996c) and a further two could not be obtained for assessment (Calderon Espina 1989; Rivero Varona 1999). Four studies had unit of analysis issues, they had randomised, or reported, by wound rather than by the participant. Such unit of randomisation or analysis issues were not considered in the protocol for the review, but we considered that such studies could not contribute usefully to this review. For further discussion on the rationale for this decision see "Differences between protocol and review" (Malik 2010; Okeniyi 2005; Oluwatosin 2000; Yapucu Gunes 2007).

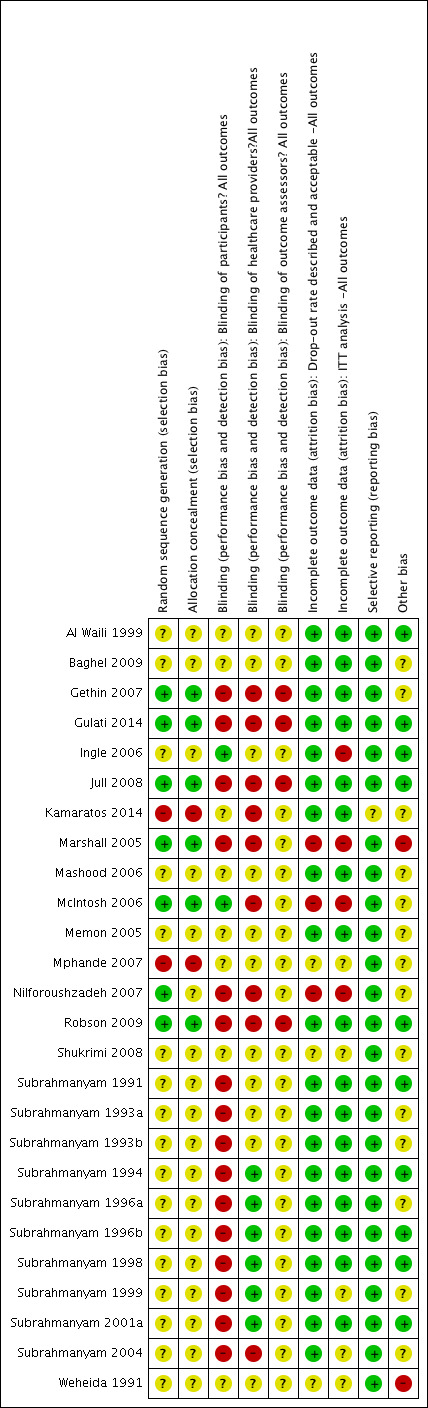

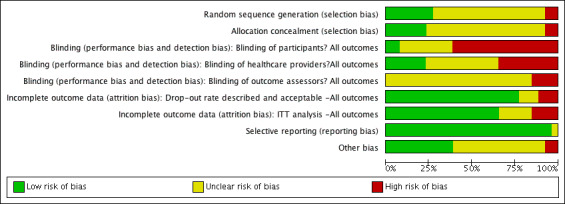

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias is summarised in the figures (Figure 1; Figure 2) with judgements explained in the Characteristics of included studies. Risk of bias was a key consideration in assessing the quality of the evidence and used (and justified) in the Summary of Findings Tables to downgrade the evidence where appropriate. Overall the quality of reporting was poor and it was frequently not possible to determine whether allocation was fully concealed. Two studies (Mphande 2007; Kamaratos 2014) used quasi‐random methods of allocation and these are at high risk of selection bias as a consequence. Most of the included studies were at risk of performance bias as neither participants nor health care providers were blinded to treatment allocation. The main outcomes of complete healing, adverse events and infection have, to varying extents, an element of subjectivity inherent in them and 14 out of 26 included studies reported having used blinded outcome assessment.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

The 26 trials included 3011 participants. The trials were generally small (median sample size 83.5, range 30 to 900), and there was very obvious clinical and methodological heterogeneity. It was not appropriate, therefore, to combine the trials in a single meta‐analysis to produce a summary statistic for honey overall, or even subgroup summary statistics for acute, chronic, or mixed wounds. Within the subgroups (acute, mixed acute and chronic, and chronic wounds) trials have been combined in meta‐analysis where appropriate. Otherwise the trials have been summarised narratively.

In common with wounds research in general, adverse event reporting was variable in nature and often poor in quality. Five trials did not report adverse events (Baghel 2009; Kamaratos 2014; Subrahmanyam 1996a; Subrahmanyam 1998; Weheida 1991), and five trials stated that there were no adverse events or no adverse events related to treatment (Gethin 2007; Gulati 2014; Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006; Subrahmanyam 1996b). One trial reported the number of people with any adverse event (Jull 2008), as well as itemising specific types of events. The remaining trials appear to have limited reporting of events to specific types of events, rather than encouraging reports of any event. Adverse events are presented by wound type, and the comparators indicated in footnotes and any meta‐analysis uses a random‐effects model due to the heterogeneity. Although only one trial explicitly reported frequency of events by participant (Jull 2008), it is assumed one event equals one participant in all other trials (this may be an erroneous assumption).

The "infection" data in these studies are not well reported and impossible to analyse in a robust manner and interpret reliably across all wound types. One of the main problems is the lack of a definition of infection within most trial reports and an inconsistency between trials. Most of the burns trials reported "positive" swab cultures at baseline and then the proportion rendered "sterile" at subsequent time points (usually 7 days). However a positive swab culture is NOT the same as a clinical infection (the diagnosis of the latter being dependent on signs and symptoms as well as culture). Consequently we cannot draw conclusions about the treatment effects of honey dressings and comparators from these data. We have confined our analysis of the burns studies to the outcome of "proportion of burns with negative swabs at 7 days" however this is a less clinically relevant outcome than healing, or clinical infection.

1. Acute wounds

1.1 Minor acute wounds

1.1.1 Honey compared with conventional dressings

Three trials (213 participants) recruited participants with minor acute wounds (Ingle 2006; Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006). In two trials, the wounds were surgical wounds created after partial or total toenail avulsions (Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006), with the control group treated with paraffin gauze in one trial and an iodophor dressing in the other. The remaining trial recruited mine workers with lacerations or shallow abrasions and treated control participants with a hydrogel (Ingle 2006).

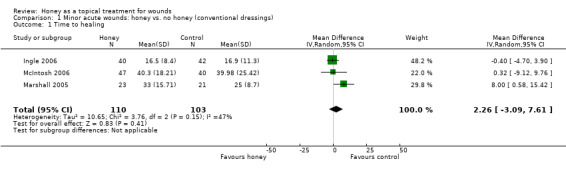

Outcome: healing

We combined the results of the three trials using a random effects model. It is unclear whether there is a difference in time to healing between honey and control (difference in mean days to healing was 2.26 days longer with honey, 95% CI ‐3.09 to 7.61 days (Analysis 1.1). Moderate heterogeneity (I² = 47%). Very low quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision) (Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Minor acute wounds: honey vs. no honey (conventional dressings), Outcome 1 Time to healing.

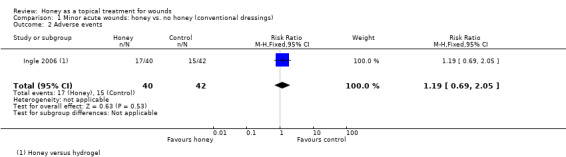

Outcome: adverse events

Ingle and colleagues reported the frequency of itching, burning and pain (Ingle 2006). There was no significant difference in the rates of these events between honey and hydrogel RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.05) (Analysis 1.2). No patient stopped treatment due to these sensations. It remains unclear as to whether there are more or fewer adverse events with honey dressings compared with non‐honey dressings in people with minor acute wounds. Very low quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias, serious inconsistency and imprecision) (Table 1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Minor acute wounds: honey vs. no honey (conventional dressings), Outcome 2 Adverse events.

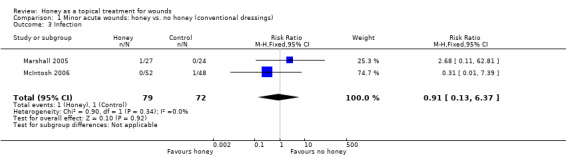

Outcome: infection

Infection was not reported by Ingle 2006. There was only one instance of infection reported in each of the other two trials (Marshall 2005; McIntosh 2006): in 1/27 participants in the honey group compared with 0/24 in the iodine group of Marshall 2005, and in 1/48 participants of the iodine group compared with 0/52 in the honey group of McIntosh 2006 (pooled RR of infection 0.91, 95% CI 0.13 to 6.37, fixed effect, Analysis 1.3). It is therefore unclear if honey affects rates of wound infection in minor acute wounds. Very low quality evidence (downgraded for the reasons outlined above) (Table 1).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Minor acute wounds: honey vs. no honey (conventional dressings), Outcome 3 Infection.

Outcome: costs

Only Ingle 2006 reported on costs, and then only in terms of average costs of dressing materials per patient in each group. These were lower in the honey group (average cost per patient 0.49 Rand) than the hydrogel group (average cost per patient 12.06 Rand) however this does not appear to have been a commercial honey preparation (hence low cost).

Outcome: quality of life

Not reported.

1.2 Burns

There were six comparison treatments, which have been grouped under the four broad categories of conventional dressings, early excision, silver sulfadiazine (SSD) and atypical dressings for this review.

1.2.1 Honey compared with conventional dressings

Two trials (992 participants) compared honey with conventional dressings for the treatment of partial‐thickness burns (Subrahmanyam 1993a; Subrahmanyam 1996a). In one trial (Subrahmanyam 1993a) the comparison was a polyurethane film dressing and in the other trial (Subrahmanyam 1996a) the control participants were treated with a range of interventions: polyurethane film (OpSite, n = 90), paraffin gauze (n = 90), sterile linen dressings (n = 90), antimicrobial impregnated gauze (Soframycin, n = 90) or left exposed (n = 90).

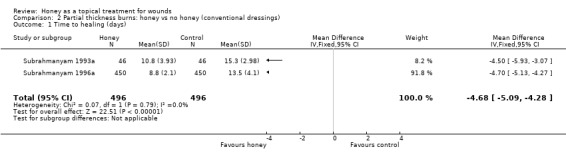

Outcome: healing

Mean days to healing were reported but not the standard deviations, though this information was later provided by the author (personal communication: M Subrahmanyam). The two trials were pooled using a fixed effect model (I2 = 0%). Burns treated with honey healed more quickly (WMD ‐4.68 days, 95% CI ‐5.09 to ‐4.28 days, Analysis 2.1). High quality evidence (Table 2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Partial thickness burns: honey vs no honey (conventional dressings), Outcome 1 Time to healing (days).

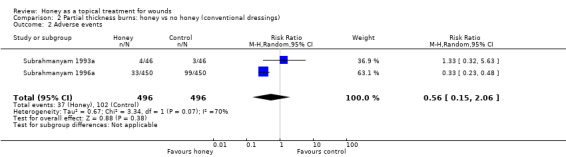

Outcome: adverse events

In Subrahmanyam 1993a there were two cases of over‐granulation and two of contracture in the honey group compared with two of over‐granulation and one of contracture in the control group. In Subrahmanyam 1996a there were five cases of hypergranulation and 28 of scarring with honey and 12 of hypergranulation and 87 of scarring with conventional dressings. These data were pooled (random effects). Overall there was no clear difference in risk of adverse events (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.06) (Analysis 2.2).Very low quality evidence (downgraded for inconsistency i.e., high heterogeneity, and imprecision) (Table 2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Partial thickness burns: honey vs no honey (conventional dressings), Outcome 2 Adverse events.

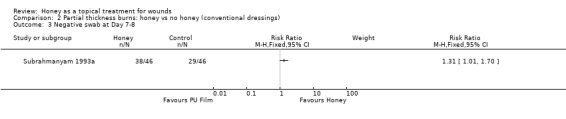

Outcome: infection

Subrahmanyam 1996a did not report infection rates. Subrahmanyam 1993a reported a greater proportion of honey participants having a negative swab at Day 8 (38/46 participants in the honey group cf. 29/46 in the polyurethane film group), (RR of a negative swab 1.31, 95%CI 1.01 to 1.70), Analysis 2.3. Low quality evidence (downgraded for imprecision and indirectness, in that a negative swab on a particular day is not a measure of infection per se)(Table 2).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Partial thickness burns: honey vs no honey (conventional dressings), Outcome 3 Negative swab at Day 7‐8.

Outcomes: costs and quality of life

Not reported.

1.2.2 Honey plus delayed grafting compared with early excision and grafting (no honey)

One trial (50 participants) compared early tangential excision and skin grafting with honey dressings plus delayed skin grafting where needed, for the treatment of mixed partial‐ and full‐thickness burns (Subrahmanyam 1999).

Outcome: healing

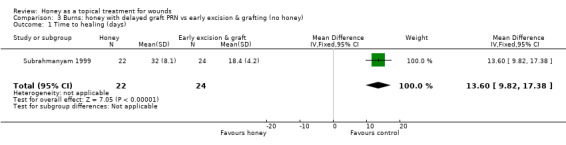

Mean time to healing was not published, but was later provided by the author (personal communication: M Subrahmanyam). Burns healed more slowly when treated with honey (followed by delayed grafting where needed) than with early excision and grafting (no honey) (WMD 13.6 days, 95% CI 9.82 to 17.38 days, Analysis 3.1). The quality of this evidence was downgraded for imprecision on the basis that there is only one trial with a total of 50 participants and whilst the difference in time to healing was statistically significant and clinically important, this is a small single study. We also downgraded the quality of the evidence for indirectness, since honey is not the only systematic difference in the treatments for this comparison as the burn excision and grafting interventions were also different (therefore the trial does not directly address the question of whether honey dressings are effective for burns). Low quality evidence.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Burns: honey with delayed graft PRN vs early excision & grafting (no honey), Outcome 1 Time to healing (days).

Outcome: adverse events

In Subrahmanyam 1999 there was a total of 6 adverse events in the honey group (3 deaths, 3 contractures), compared with one death in the early excision group. Low quality evidence (see above).

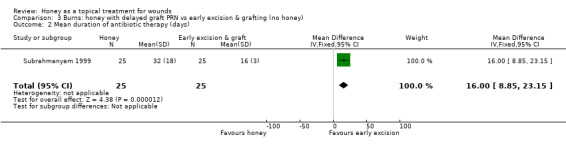

Outcome: infection

Infection rates per se were not reported for Subrahmanyam 1999 however days of antibiotic therapy (which is a proxy for infection), were. Participants in the honey group received a mean of 32 (SD 18) days of antibiotics compared with 16 (SD 3) in the early excision and graft group (difference in mean days of antibiotic therapy 16.00, 95% CI 8.85 to 23.15) (Analysis 3.2). Low quality evidence (downgraded two levels for indirectness since honey is not the only systematic difference between treatments and the outcome "days of antibiotic therapy" is only a proxy for infection).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Burns: honey with delayed graft PRN vs early excision & grafting (no honey), Outcome 2 Mean duration of antibiotic therapy (days).

Outcomes: costs

Not reported.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

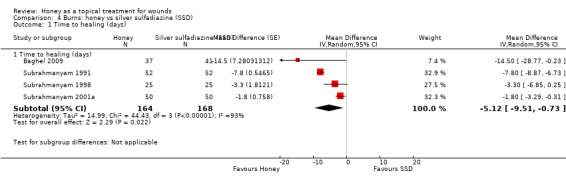

1.2.3 Honey compared with silver sulfadiazine

Six trials (462 participants) compared honey with SSD (Baghel 2009; Mashood 2006; Memon 2005; Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1998; Subrahmanyam 2001a). The trials used different burn grading systems to report the depth of burns, which reflected the age of the trials and the lack of a clinical consensus on reporting burn depth. The burns, however, did tend towards the less severe end of the spectrum, although early staging systems (e.g. first‐, second‐ and third‐degree burns, or superficial, partial‐thickness and full‐thickness) do not have the sensitivity of more recent systems (i.e. epidermal, superficial dermal, mid‐dermal, deep dermal and full‐thickness), and participants with deep partial‐thickness and deep dermal burns are likely to require skin grafting (NZGG 2007).

Trials recruited participants with superficial and partial‐thickness burns (Baghel 2009), superficial burns (Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1998), superficial, partial‐ and deep partial‐thickness burns (Mashood 2006), and one recruited participants with superficial, dermal, mid and deep dermal burns (Memon 2005). The remaining trial did not report their eligibility criteria but some of the participants had full thickness burns (Subrahmanyam 2001a).

The studies used different treatment regimens. All applied honey topically, covered with gauze. Three studies gave SSD as a topical cream covered by gauze (Baghel 2009; Mashood 2006; Memon 2005) and the rest as SSD impregnated gauze. Two studies changed both types of dressings daily (Mashood 2006; Subrahmanyam 1991); two changed both types of dressing on alternate days (Memon 2005; Subrahmanyam 2001a) and the other study did not report the frequency of dressing change (Baghel 2009). The study by Subrahmanyam 1998 changed the SSD dressings daily and the honey dressings on alternate days.

Outcome: healing

One trial reported mean time to healing and the risk of healing at different times (Subrahmanyam 2001a), and five trials reported either mean time to healing without standard deviations (Baghel 2009; Memon 2005), or risk of complete healing (Mashood 2006; Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1998), but at different time points i.e., two, four, and six weeks (Mashood 2006), and seven, 10, 15, 21 and 30 days (Subrahmanyam 1998).

Additional information was sought from authors and provided by one author (personal communication: M Subrahmanyam). Baghel 2009 reported an exact p‐value for the comparison of time to healing and this was used to calculate the standard error for mean time to healing. Thus mean time to healing was used as the outcome, with the result that four trials out of six could be pooled for the outcome of mean time to healing using a random effects model (heterogeneity was extremely high, I² = 93%). In these four trials, people whose burns were treated with honey experienced an average reduction in healing time of 5 days (WMD ‐5.12 days, 95% CI ‐9.51 to ‐0.73) (Analysis 4.1). This was very low quality evidence (downgraded for inconsistency and imprecision) (Table 3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Burns: honey vs silver sulfadiazine (SSD), Outcome 1 Time to healing (days).

In the trial that did not report standard deviations with mean time to healing (Memon 2005), the honey‐treated group had a mean time to healing of 15.3 days and it was 20.0 days in the SSD group (Memon 2005). In the remaining trial (Mashood 2006), all 25 participants in the honey‐treated group were healed by four weeks, while all patients in the SSD group were healed by six weeks.

All six trials reported the risk of complete healing at either 4 or six weeks (or both) as well as several earlier time points. We wished to reduce the risk of Type I errors inherent in multiple endpoint analysis. We therefore report the pooled risk of complete healing for all six trials at 4 to 6 weeks (Mashood 2006; Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1998; Subrahmanyam 2001a; Baghel 2009; Memon 2005) using a random effects model because although the I2 was 0% these trials are clearly different in terms of frequency of dressing changes, types of burns and duration of follow up. There was no difference in the risk of burns healing by 4 to 6 weeks when treated with honey compared with SSD (RR 1.00 95% CI 0.98 to 1.02). High quality evidence (Table 3).

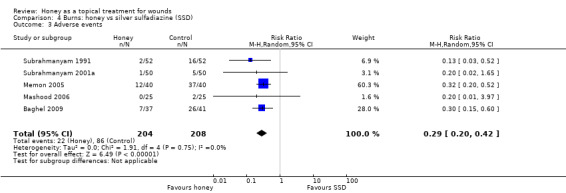

Outcome: adverse events

Burns trials tended to report the frequencies of hypergranulation, contracture, hypertrophic scarring, minor scarring, itching and burning as adverse events however it was generally unclear if events were reported by individual without double counting, or (more likely) some individuals experienced more than one adverse event. Consequently we are not confident of the accuracy of the adverse events data. The adverse event data across the five trials that reported them (Baghel 2009; Mashood 2006; Memon 2005; Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 2001a) were pooled (random effects); importantly Mashood 2006 stated that there was "no difference" between groups in rates of contracture and hypertrophic scarring but only reported rates of itching and burning. Overall there were significantly fewer adverse events with honey than SSD (RR 0.29 95% CI 0.20 to 0.42) (Analysis 4.3). High quality evidence (Table 3).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Burns: honey vs silver sulfadiazine (SSD), Outcome 3 Adverse events.

Outcome: infection

Infection related outcomes were reported in a variety of ways: most consistently five out of six trials reported the proportion of burns yielding negative swabs at Day 7 (Baghel 2009; Memon 2005; Subrahmanyam 1991; Subrahmanyam 1998; Subrahmanyam 2001a). The report of Mashood 2006 merely stated the time to sterility (with no SD or other measure of variance) in each group. There was very high statistical heterogeneity when pooling the five studies (I2=94%). Overall wound swabs from honey treated burns were more likely to be negative at 7 days than were swabs from SSD treated burns (RR 3.92 95% CI 1.32 to 11.63) (Analysis 4.4) however this is very low quality evidence (downgraded for inconsistency, imprecision and indirectness) (Table 3).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Burns: honey vs silver sulfadiazine (SSD), Outcome 4 Negative swab at Day 7.

Outcomes: costs

Only Mashood 2006 reported any cost data and then only as standardised unit costs (per percentage of (total body surface area) TBSA) of dressing treatments. They reported that the honey cost 0.75 Rupees per percentage TBSA compared with SSD which costs 10 Rupees per percentage TBSA.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

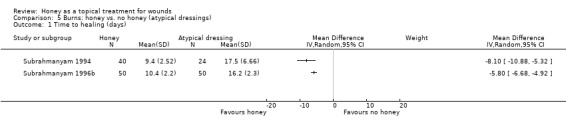

1.2.4 Honey compared with atypical dressings

Two trials (164 participants) by the same investigator compared honey with atypical dressings or materials (Subrahmanyam 1994; Subrahmanyam 1996b). The first trial recruited 64 participants with partial‐thickness burns and compared honey‐impregnated gauze with treatment with amniotic membranes (Subrahmanyam 1994) and the second recruited 100 people with partial thickness burns and compared honey with boiled potato peel dressings (Subrahmanyam 1996b).

Outcome: healing

The mean time to healing was reported for both trials without SDs which were subsequently supplied by the author (personal communication: M Subrahmanyam). Burns treated with honey healed approximately 8 days more quickly than those treated with amniotic membranes (WMD ‐8.10 days, 95% CI ‐10.88 to ‐5.32). In the second trial, burns treated with honey healed approximately 6 days more quickly than those treated with boiled potato peel (WMD ‐5.80 days, 95% CI ‐6.68 to ‐4.92).

The comparator treatments for these two trials are too different to pool them. The evidence for both these comparisons should be downgraded for imprecision (due to the relative lack of evidence) and therefore this constitutes moderate quality evidence.

Outcome: adverse events

Subrahmanyam 1994 reported that 4/40 and 3/40 people in the honey group experienced scarring/contractures and severe pain respectively compared with 5/24 and 6/24 in the amniotic membrane group (we cannot assume that the people experiencing pain were separate from the people having scarring or contractures). It was stated that there were no allergies or side effects in either group in the other study (Subrahmanyam 1996b).

Outcome: infection

Both studies reported the outcome of a negative swab at Day 7. In Subrahmanyam 1994, 36/40 (90%) of honey treated burns had negative swabs at Day 7 compared with 18/24 (75%) of burns treated with amniotic membrane. In Subrahmanyam 1996b, 36/50 (72%) of burns treated with honey had negative swabs at Day 7 compared with 8/50 (16%) treated with potato peel.

Outcomes: costs

Not reported.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

2. Mixed acute and chronic wounds

Two trials (140 participants) each recruited participants with a range of different acute and chronic wounds. Subrahmanyam 1993b recruited 100 participants with burns (50% of the study population), lower limb ulcers caused by trauma, pressure, diabetes, and venous disease, or trophic ulcers and compared honey with SSD. In a quasi‐randomised study, Mphande 2007 recruited 40 participants with ulcers, chronic osteomyelitis, abscesses, post‐surgical or traumatic wounds; the comparison treatment was sugar dressings.

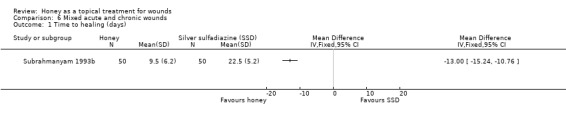

Outcome: healing

For the Subrahmanyam 1993b study, information on overall mean time to healing was provided by the author (personal communication: M Subrahmanyam). Wounds treated with honey healed more quickly than those treated with SSD (difference in mean days to healing ‐13.0 days, 95% CI ‐10.76 to ‐15.24) (Analysis 6.1)

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Mixed acute and chronic wounds, Outcome 1 Time to healing (days).

In the Mphande 2007 study, median time to complete healing was 31.5 days in the honey‐treated group and 56.0 days in the sugar‐treated group.

Outcome: adverse events

Subrahmanyam 1993b reported hypergranulation, hypertrophic scarring, contractures and irritation as adverse events: 2/50 (4%) in the honey group experienced these compared with 14/50 (28%) in the SSD group. Mphande 2007 did not refer to adverse events generally but did report on pain in terms of being pain free during dressing changes at 3 weeks and also pain during mobilisation at 3 weeks. 19/22 participants (86.4%) in the honey group were pain free during dressing changes at 3 weeks compared with 13/18 (72.2%) in the sugar dressing group. 20/22 participants (90.9%) in the honey group and 13/18 (72.2%) in the sugar group were pain free during mobilisation.

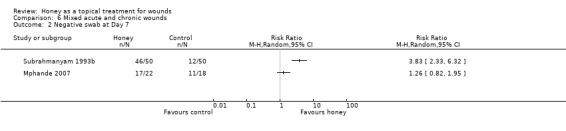

Outcome: infection

Both Mphande 2007 and Subrahmanyam 1993b reported the outcome of negative swabs at 7 days however these results cannot be pooled as the comparator treatments are so different. It is unclear whether honey is associated with more negative swabs at 7 days than either SSD or sugar dressings due to imprecision and risk of (performance) bias (Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Mixed acute and chronic wounds, Outcome 2 Negative swab at Day 7.

Overall there is low quality evidence (downgraded for imprecision on account of the two small studies, and indirectness on account of the mixed patient population and difficulties of interpretation) that, on average, honey heals a heterogeneous population of acute and chronic wounds more quickly than SSD or sugar dressings though the comparative rates of adverse events and infection are unclear.

Outcomes: costs

Not reported.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

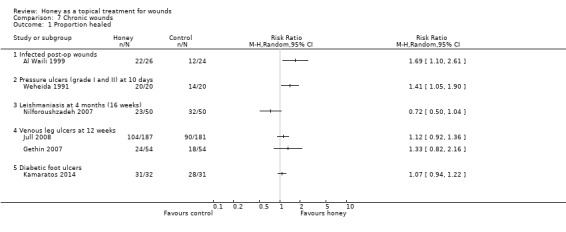

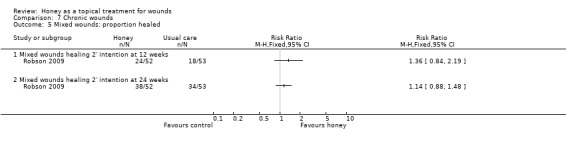

3. Chronic Wounds

Ten trials (819 participants) evaluated the effects of honey in chronic wounds. Two trials recruited people with venous leg ulcers (Gethin 2007; Jull 2008); one study (Robson 2009) recruited participants with any type of wound healing by secondary intention but most of these were leg ulcers (70%); one study recruited people with a range of chronic wounds though most were venous leg ulcers (Gulati 2014). Two studies recruited people with diabetic foot ulcers (Kamaratos 2014; Shukrimi 2008) and one study for each of the following: ulcers caused by Leishmaniasis (Nilforoushzadeh 2007); pressure injuries (Weheida 1991); infected post‐operative wounds (Al Waili 1999), and Fournier's gangrene (Subrahmanyam 2004). Five of these ten studies were added at the first or second update (Gulati 2014; Kamaratos 2014; Nilforoushzadeh 2007; Robson 2009; Shukrimi 2008),

Three trials reported either the mean or median time to healing (Al Waili 1999; Jull 2008), or the mean time to surgical closure (Shukrimi 2008); seven trials reported the proportion of participants with completely healed wounds (Gethin 2007; Gulati 2014; Jull 2008; Kamaratos 2014; Nilforoushzadeh 2007; Robson 2009; Weheida 1991). One trial only reported the outcome, "mean hospital stay", but data on mean time to healing were provided by the author (Subrahmanyam 2004). Given the clinical and methodological heterogeneity between the trials, it was not possible to combine the trials to produce an overall summary statistic for the effect of honey on chronic wounds and instead we consider the evidence by wound type below.

3.1 Infected post‐operative wounds

One trial (50 participants) randomly allocated participants with infected caesarean or hysterectomy wounds to twice daily applications of honey or antiseptic washes of 70% ethanol and povidone‐iodine, followed by gauze dressings (Al Waili 1999), in addition to systemic antibiotics. There was very limited information on baseline comparability and no real indication of the duration of treatment or length of follow‐up.

Outcome: healing

More people healed with honey (84.6%) than with antiseptic washes followed by gauze dressings (50.0%); RR 1.69 (95% CI 1.10 to 2.61) (Analysis 7.1) (moderate quality evidence; downgraded for imprecision). This equates to an increase in the absolute risk of healing of 35% (95%CI 8.7% to 55.4%).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Chronic wounds, Outcome 1 Proportion healed.

Outcome: adverse events

People were less likely to be recorded as having experienced adverse events with honey: 4/26 honey treated wounds (15.3%) compared with 12/24 (50%) of control wounds dehisced; 6/24 (25%) of control wounds needed resuturing compared with none in the honey group (moderate quality evidence; downgraded for imprecision).

Outcome: infection

Al Waili 1999 reported the mean time (days) to a negative swab as a measure of infection; this was 6 days (SD 1.9) for honey compared with 14.8 days (SD 4.2) for antiseptics and gauze (moderate quality evidence, downgraded for imprecision).

Outcomes: costs

Not reported.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

3.2 Pressure injuries

One trial (40 participants) randomly allocated participants with uninfected grade I or grade II pressure injuries greater than 2 cm in diameter to daily applications of honey or saline‐soaked gauze dressings for 10 days treatment (Weheida 1991). There was limited information on baseline comparability.

Outcome: healing

More people treated with honey were healed at 10 days (100%) than those treated with saline soaks (70%); RR 1.41 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.90) Analysis 7.1 (very low quality evidence due to imprecision and potential selection bias as assessed by baseline imbalance).

Outcome: adverse events

Not reported.

Outcome: infection

Not reported.

Outcomes: costs

Not reported.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

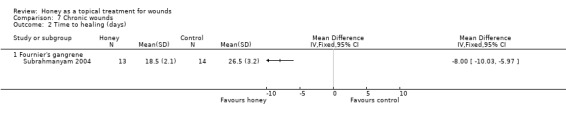

3.3 Fournier's gangrene

One trial in which 30 men with Fournier's gangrene (23 of whom were chronic alcoholics) were randomly allocated to be treated with monofloral (jamun) honey‐soaked gauze dressings or antiseptic EUSOL‐soaked gauze dressings (Subrahmanyam 2004). Fournier's gangrene is an infection of the scrotum that can also involve the perineum and abdominal wall.

Outcome: healing

Secondary suturing and skin grafting were required in 9/14 (64.3%) of the honey group and 9/16 (56.3%) of the EUSOL group. Only mean length of hospital stay was reported in the paper, but mean time to healing was supplied by the author (personal communication M Subrahmanyam). Mean time to healing was shorter in the honey‐treated group (MD ‐8.00 days, 95% CI ‐6.08 to ‐9.92 days, Analysis 7.2), but we note this was a very small sample size and the high rates of further surgical intervention (secondary suturing and skin grafting) required by participants in both groups is worth noting (very low quality evidence, on account of the very small sample size and single study).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Chronic wounds, Outcome 2 Time to healing (days).

Outcome: adverse events

One participant in the honey‐treated group and two in the EUSOL group died.

Outcome: infection

The primary condition (Fournier's gangrene) is itself the result of infection; rates of secondary infection were not reported.

Outcomes: costs

Not reported.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

3.4 Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

One trial (100 participants) randomly allocated participants with ulcers caused by Leishmaniasis to treatment with intralesional injections of meglumine antimoniate (glucantamine) plus honey‐soaked gauze dressings or intralesional injections alone (Nilforoushzadeh 2007).

Outcome: healing

Thirteen participants withdrew from the honey dressings arm due to treatment failure (n=12) or contact dermatitis (n=1) (and therefore remain in this analysis in the denominator) whilst 10 withdrew from the meglumine antimoniate alone group due to treatment failure (similarly remaining in the denominator). Fewer people treated with injections plus honey had healed lesions compared with those not receiving honey at 4 months although this difference was not statistically significant (51.1% versus 71.1%) (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.04) (Analysis 7.1) (low quality evidence due to imprecision and high risk of bias).

Outcome: adverse events

The study by Nilforoushzadeh 2007 reported one withdrawal due to sensitivity in the honey group and none in the control group.

Outcome: infection

Not reported.

Outcomes: costs

Not reported.

Outcomes: quality of life

Not reported.

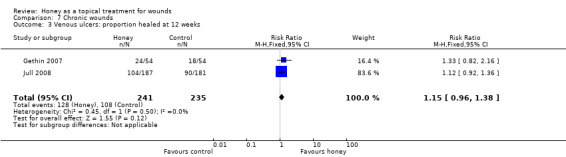

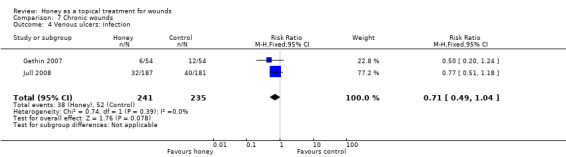

3.5 Venous leg ulcers

Two trials recruited only participants with venous leg ulcers. One trial (368 participants) recruited patients presenting to community‐based nursing services for assessment and treatment of their venous ulcers (Jull 2008). Participants were allocated to receive either manuka honey‐impregnated calcium alginate dressings or usual care. Participants allocated usual care could receive any dressing that was clinically indicated from the wide range normally available to community nurses (non‐adherent, alginate, hydrogel, hydrofibre, hydrocolloid, silver or iodophor dressings). Both groups received compression bandaging as a standard background treatment. Participants were treated for 12 weeks. The second trial recruited 108 participants with uninfected venous ulcers, the surfaces of which were at least 50% covered by slough (Gethin 2007). Participants were allocated to receive either manuka honey dressings or hydrogel dressings for four weeks and then standard care (the nature of which was individually determined by the clinician) for the remaining eight weeks of the 12 week follow‐up. Both groups received compression bandaging as a standard background treatment. A third trial (Robson 2009) compared honey with usual care in a population that included approximately 70% people with venous leg ulcers. Although it was not possible to separate out the results for people with venous leg ulcers that study also found no difference in risk of healing between honey and usual care (see section 3.6 below).

Outcome: healing

The Jull 2008 trial appropriately analysed healing as a time to event outcome using a survival approach. There was no difference in healing between groups treated with honey and usual (non‐honey) care (adjusted hazard ratio, HR, 1.1, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.5, P=0.451). There was no difference in the risk of healing at 12 weeks with or without honey (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.37).

The Gethin 2007 study had change in area of slough at four weeks as the primary outcome and proportion of ulcers healed at 12 weeks as a secondary outcome. In this study 24/54 (44.4%) participants in the honey group had healed at 12 weeks compared with 18/54 (33.3%) in the control group (RR of healing 1.33, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.16).

Although the duration of treatment was dissimilar across the two trials, they were considered sufficiently alike to be able to provide meaningful information when combined (I² 0%). Overall it is not clear whether honey increases the healing of venous leg ulcers compared with no honey (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.38) (Analysis 7.3) (low quality evidence; downgraded for risk of bias due to unblinded outcome assessment and imprecision) (Table 4).

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Chronic wounds, Outcome 3 Venous ulcers: proportion healed at 12 weeks.

Outcome: adverse events

The Jull 2008 trial (368 participants) reported all adverse events, whether or not the event was believed to be related to the treatment, whereas the Gethin 2007 trial (108 participants) only referred to events that were attributable to the wound agent, of which there were none (and this approach is subject to ascertainment bias in an open label study). In the Jull 2008 trial there were significantly more adverse events (including deterioration of the ulcer) reported in the honey‐treated group than the control group (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.56). The frequency of the different adverse events is presented in Table 5. It is notable that there were high frequencies of pain (47/187 versus 18/181) and of ulcer deterioration (19/187 versus 9/181) with honey (low quality evidence, downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision, Table 4).

1. Frequency of adverse events reported in venous ulcer trial (Jull 2008).

| Adverse event | Honey treatment | Control treatment |

| Ulcer pain | 47/187 | 18/181 |

| Bleeding | 3/187 | 3/181 |

| Dermatitis | 8/187 | 8/181 |

| Deterioration of ulcer | 19/187 | 9/181 |

| Erythema | 6/187 | 4/181 |

| Oedema | 4/187 | 1/181 |

| Increased exudate | 5/187 | 1/181 |

| Deterioration of surrounding skin | 5/187 | 3/181 |

| New ulceration | 16/187 | 15/181 |

| Other | 6/187 | 3/181 |

| Cardiovascular | 4/187 | 3/181 |

| Cancer | 2/187 | 2/181 |

| Neurological | 4/187 | 1/181 |

| Gastrointestinal | 4/187 | 2/181 |

| Injury | 10/187 | 9/181 |

| Musculoskeletal | 13/187 | 9/181 |

| Respiratory | 6/187 | 3/181 |

| Other | 3/187 | 8/181 |

Outcome: infection

The Jull 2008 trial reported risk of infection whilst the Gethin 2007 study reported withdrawals due to infection. Infection was operationally defined as clinical signs of infection or a positive swab result, and treatment with antibiotics in Jull 2008.These data were pooled (fixed effect) and it remains unclear if honey reduces leg ulcer infection rates relative to no honey (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.04) (Analysis 7.4) (low quality evidence, downgraded for risk of bias, Table 4).

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Chronic wounds, Outcome 4 Venous ulcers: infection.

Outcome: cost