Abstract

Background

Avoiding use of opioids while alone reduces overdose fatality risk; however, drug use-related stigma may be a barrier to consistently using opioids in the presence of others.

Methods

We described the frequency of using opioids while alone among 241 people reporting daily heroin use or non-prescribed use of opioid analgesic medications (OAMs) in the month before attending a substance use disorder treatment program in the Midwestern USA. We investigated drug use-related stigma as a correlate of using opioids while alone frequently (very often vs. less frequently or never) and examined overdose risk behaviors associated with using opioids while alone frequently, adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

The sample was a median age of 30 years, 34% female, 79% white, and nearly all (91%) had experienced an overdose. Approximately 63% had used OAMs and 70% used heroin while alone very often in the month before treatment. High levels of anticipated stigma were associated with using either opioid while alone very often (adjusted PR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.04–1.38). Drinking alcohol and taking sedatives within two hours of OAMs very often (vs. less often or never) and using OAMs in a new setting very often (vs. less often or never) were associated with using OAMs while alone very often. Taking sedatives within two hours of using heroin and using heroin in a new setting very often (vs. less often or never) were associated with using heroin while alone very often.

Conclusion

Anticipated stigma, polysubstance use, and use in a new setting were associated with using opioids while alone. These findings highlight a need for enhanced overdose harm reduction options, such as overdose detection services that can initiate an overdose response if needed. Addressing stigmatizing behaviors in communities may reduce anticipated stigma and support engagement and trust in these services.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12954-022-00723-4.

Keywords: Opioids, Overdose, Harm reduction, Stigma, Using alone, Polysubstance use

Introduction

Using drugs while alone, away from bystanders who could potentially respond to an overdose, may contribute to growing overdose mortality, particularly in the context of COVID-19 and growing social isolation [1]. Fatal overdose deaths involving opioids and/or stimulants commonly occur during solitary use. Across studies of fatal overdose events, 39–83% of overdose deaths occurred when an individual was alone at the time of the overdose [2–9]. Overdose reversal through naloxone administration is an effective strategy to decrease deaths associated with opioid-involved overdose. However, naloxone by itself is inadequate to prevent death in the case of solitary drug use, as no bystanders are present to administer naloxone even if it is available [10].

Using drugs while alone is a well-recognized risk factor for fatal overdose, demonstrated by the recommendation to avoid using drugs while alone in public health overdose harm reduction campaigns (e.g., [11]). However, there is limited research into how commonly this behavior occurs or why and when individuals use opioids while alone vs. in the vicinity of others. Existing estimates suggest wide heterogeneity in the prevalence of solitary use, from 7 to 81% depending on the population studied, drugs used, and route of administration [12–25]. To our knowledge, only one prior study summarized the prevalence of solitary use by opioid type, finding that 7% of a sample of male veterans used heroin while alone and 17% reported non-prescribed opioid analgesic medication use while alone [12]. Solitary use was markedly higher among a subgroup of participants who frequently used heroin. Further, prior studies have primarily focused on injecting while alone [13–15, 17, 22–25] and/or recruited participants from harm reduction service venues commonly accessed by those injecting [16, 19–21]. Taken together, a better understanding of how often people use specific types of opioids and their route of administration while they are alone could help inform future harm reduction programming.

People who use drugs cite several reasons for using substances while alone in prior studies. Qualitative research has suggested that self-stigma, anticipated stigma, and discrimination related to substance use, economic concerns (i.e., sharing drugs when with others), and a sense of urgency to ameliorate withdrawal symptoms may drive decision-making around using while alone [26]. It is not yet known how depression, suicidal thinking, self-stigma, and anticipated stigma are quantitatively associated with solitary use, though these are known correlates of overdose and disengagement in substance use treatment [27–31]. One recent study found that the most common reason people used alone related to preferences for convenience and comfort within the setting of use [20]. Other settings, such as public settings (e.g., outdoors), have been associated with overdose, perhaps related to rushed use in unfamiliar or non-private settings due to fear of law enforcement [29]. Methods to garner privacy when in public or shared spaces (e.g., using behind a closed or locked door [26, 32]) may also raise fatality risk as these can preclude bystander access to an overdose victim.

Several additional behaviors increase the likelihood that an overdose occurs or is fatal, regardless of whether someone uses while alone. Polysubstance use may raise the possibility of drug–drug interactions [33–36]. Alcohol and benzodiazepines are of particular concern when mixed with opioids [34]. Further research is needed to characterize other overdose risk behaviors that may co-occur with using while alone.

This study sought to analyze the prevalence and correlates of using opioids while alone among a sample of patients surveyed during residential substance use disorder treatment by evaluating differences in overdose risk behaviors and psychosocial and behavioral characteristics between individuals who reported frequently using opioids while alone relative to those who did not. First, we describe the prevalence of using opioid analgesic medications and heroin while alone with data from a cross-sectional study of 241 people receiving treatment for a substance use disorder who had used opioids daily in the month prior to treatment. Second, we examine other overdose risk behaviors reported by individuals who use while alone frequently, including polysubstance use (e.g., opioids with benzodiazepines or alcohol). Finally, we examine how several psychosocial and behavioral correlates are associated with using while alone, including stigma related to substance use, depression, living situation, type of opioid used, and route of administration. This research will help inform future overdose harm reduction and prevention interventions tailored to people who use opioids while alone and elucidate possible barriers and solutions to adopting public health recommendations to avoid solitary use.

Methods

Analytic sample

Data for the present study came from a cross-sectional survey completed by 817 patients in a residential treatment program for any type of substance use disorder in suburban Michigan during 2014–2016. Participants were in treatment at study enrollment, and the dataset used for this analysis was originally collected to assess eligibility for participation in a randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02152397). English-speaking patients aged ≥ 18 years were approached by research staff. Interested participants provided informed consent, self-administered a 45-min paper and pencil survey, and received $5 remuneration. The majority of participants in the parent study, like most of those who receive treatment at the study site, were diverted to treatment from jail, prison, or after other types of involvement with the criminal justice system [37].

Inclusion in the present analysis was restricted to 274 participants who reported using opioids daily in the month before treatment or jail. Specifically, these individuals reported either 1) using heroin for ≥ 7 consecutive days in the month before jail or treatment or 2) using opioid analgesic medications for ≥ 7 consecutive days in the month before jail or treatment and having evidence of recent non-prescribed use of opioid analgesic medications (described further below in Measures). After removing individuals missing key measures described below, 241 participants remained for the analysis.

Measures

Because many participants were diverted to treatment from jail or prison, measures used in this study referred to time periods when participants were last in the community (i.e., before they attended treatment or went to jail or prison).

Daily opioid use eligibility criteria

Participants from the parent study were included in this analysis if they met at least one of two criteria pertaining to opioid use. First, they reported “Yes” when asked, “In the month before you entered treatment or jail, have you used heroin at least 7 days in a row?” Alternatively, participants were eligible if they had evidence of recent non-prescribed use of opioid analgesic medications. This was defined as reporting “Yes” when asked, “In the month before you entered treatment or jail, have you used opioid pain medications at least 7 days in a row?” and additionally having a score indicative of moderate or severe opioid misuse based on the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) [38–40]. For the COMM, participants were asked six questions about how often (range: 0 [Never] to 4 [Very Often]) in the month before entering treatment or jail they: 1) went to someone other than their prescribing physician to get sufficient pain relief from prescription opioids, 2) took prescription opioids differently than prescribed, 3) needed to take prescription opioids belonging to someone else, 4) took more than prescribed, 5) borrowed prescription opioids from someone else, or 6) used prescription opioids to treat symptoms other than pain. Summed responses from these six items were used to classify the severity of misuse (none/mild: score of 0–9 vs. moderate/severe: score of 10–24) based on thresholds described in prior research [40].

Using opioids while alone

Participants were asked, “In the month before you entered treatment or jail, how often have you used opioid pain medications when nobody else was around?” and “In the month before you entered treatment or jail, how often have you used heroin when nobody else was around?” Answer choices were “Never,” “Rarely,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” or “Very Often”. Based on the skewed distributions of responses in the sample (76% of participants reported “Very Often” using any opioid while alone and 98% reported using any opioid while alone “Very Often,” “Often,” or “Sometimes”), three binary indicators were created for main analyses: 1) using opioid analgesic medications while alone very often (vs. never, rarely, sometimes, or often), 2) using heroin while alone very often (vs. never, rarely, sometimes, or often), 3) using either opioid while alone very often (vs. never, rarely, sometimes, or often). Additional binary variables were created for sensitivity analyses, including using while alone very often or often (vs. sometimes, rarely, or never), as well as using while alone very often, often, or sometimes (vs. rarely or never).

Overdose risk behaviors

Several additional overdose risk behaviors were examined to determine if any were more frequently reported among those using while alone very often. These included frequency of taking prescription sedatives (e.g., Xanax) within two hours of opioid analgesic medications or within two hours of heroin, drinking alcohol within two hours of using opioid analgesic medications or within two hours of using heroin, and using heroin or opioid analgesic medications in a new setting or place in the month before treatment or jail. To be consistent with the binary outcome measures summarizing using while alone, those who endorsed these behaviors very often (vs. never, rarely, sometimes, or often) were examined in main analyses, with separate indicators for opioid analgesic medications, heroin, and either substance. Other binary variables that combined often or sometimes with very often responses were examined in sensitivity analyses.

Sociodemographic, psychosocial, and behavioral variables

Several psychosocial and behavioral correlates of using while alone were examined. First, self-stigma and anticipated stigma were measured using two subscales from the validated Substance Abuse Self-Stigma Scale [41]. Self-stigma was from the 8-item self-devaluation stigma subscale (α = 0.82; example question: “I have the thought that a major reason for my problems with substances is my own poor character”). Anticipated stigma was from the 9-item fear of enacted stigma subscale (α = 0.88; example question: “People think I’m worthless if they know about my substance use history”). Participants rated their agreement with each question on a scale of 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (very often). Questions from each subscale are included in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Other correlates included symptoms of major depressive disorder at the time of the survey based on validated cutoffs (score of 10 or above) from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [42], predominant living situation in the past 3 months (temporary housing [rooming house or hotel, halfway house, group home, hospital, inpatient treatment center, jail, prison, shelter, or homeless] vs. stable housing [house, apartment, or living with a friend or family member]), current marital status or cohabitation with a significant other (vs. not), route of administration (i.e., snorting drugs in the month before treatment or jail; injecting drugs in the month before treatment or jail), whether the participant had witnessed an overdose in their lifetime, and whether the participant had personally experienced an overdose in their lifetime. Sociodemographic characteristics included self-reported age, gender (male, female, or another gender), race (categorized as white, black or African American, another race [American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Asian, or Other race]) and education level (categorized as high school, GED, or greater vs. less than high school education).

Statistical analysis

First, frequencies of the main outcomes (i.e., using while alone) and other overdose risk behaviors were described. To further contextualize opioid use behaviors in the sample, differences between those reporting daily use of heroin vs. opioid analgesic medications were also described. Associations between overdose risk behaviors with using heroin or opioid analgesic medications while alone very often (vs. often, sometimes, rarely, or never) in the month before treatment or jail were examined using Poisson generalized estimating equation models with robust standard errors to estimate prevalence ratios (PRs) [43]. Using similar statistical methods, associations between psychosocial and behavioral correlates and using any opioid while alone very often (vs. often, sometimes, rarely, or never) were examined. Both unadjusted and adjusted PRs for these associations were examined. Adjusted models included sociodemographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, gender) and other variables associated with using opioids while alone in bivariate analyses. Finally, dichotomous variables comparing those using opioids while alone very often or often vs. never, rarely, or sometimes and variables comparing those using opioids while alone very often, often, or sometimes vs. never or rarely were examined in sensitivity analyses to determine whether conclusions differed when the frequency of overdose risk behaviors were grouped differently.

Results

We included 241 participants who reported using opioid analgesic medications or heroin at least daily in the month prior to treatment or jail. Approximately 79% of participants were white, 34% were female, and the average age was 30 years (Table 1). Approximately 81% graduated high school or obtained a GED and 55% lived in temporary housing in the past three months. The most common type of temporary housing reported was prison or jail (n = 95), and 10 participants reported being homeless or living in a shelter.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of participants reporting daily non-prescribed OAM use, heroin use, or both

| Total n (%) | OAMs only n (%) | Heroin only n (%) | Heroin and OAMs n (%) | Chi-squared p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 241 (100) | 43 (17.8)a | 62 (25.7)a | 136 (56.4)a | – |

| Age, median (IQR) | 30 (25–37) | 34 (27–46) | 29 (25–35) | 29 (25–35) | 0.03b |

| Female gender | 83 (34.4) | 11 (25.6) | 23 (37.1) | 49 (36.0) | 0.4 |

| Race | 0.2b | ||||

| African American | 19 (7.9) | 6 (14.0) | 3 (4.8) | 10 (7.4) | |

| White | 190 (78.8) | 33 (76.7) | 46 (74.2) | 111 (81.6) | |

| Other | 32 (13.3) | 4 (9.3) | 13 (21.0) | 15 (11.0) | |

| Temporary housing in Past 3 Months | 132 (55.2) | 22 (51.2) | 31 (50.0) | 79 (59.0) | 0.4 |

| Married or living with someone | 43 (17.8) | 12 (27.9) | 11 (17.7) | 20 (14.7) | 0.1 |

| High School, GED, or greater education | 195 (80.9) | 35 (81.4) | 56 (90.3) | 104 (76.5) | 0.07 |

| Symptoms of major depressive disorder | 142 (58.9) | 25 (58.1) | 32 (51.6) | 85 (62.5) | 0.4 |

| Injected or snorted any drugd | 229 (95.8) | 35 (81.4) | 61 (98.3) | 133 (99.3) | < 0.001c |

| Snorted any drug very oftend | 50 (20.7) | 12 (27.9) | 3 (4.8) | 35 (25.7) | 0.001 |

| Injected any drug very oftend | 152 (63.1) | 4 (9.3) | 46 (74.2) | 102 (75.0) | < 0.001 |

| Experienced an overdose in lifetime | 218 (90.5) | 38 (88.4) | 54 (87.1) | 126 (92.6) | 0.4c |

| Experienced an overdose in the past year | 166 (68.8) | 26 (60.5) | 36 (58.1) | 104 (76.5) | 0.01 |

| Witnessed an overdose in lifetime | 216 (89.6) | 37 (86.0) | 56 (90.3) | 123 (90.4) | 0.7c |

aPercents among total n = 241. bKruskal–Wallis test. cFisher’s exact test. dIn the month before treatment or jail. Abbreviations: IQR: interquartile range; OAM: opioid analgesic medication

Over half of participants (n = 136, 56%) reported daily use of both opioid analgesic medications and heroin in the month before treatment or jail. Of the remaining participants, 43 (18%) reported daily non-prescribed opioid analgesic medication use but not heroin, and 62 (26%) used heroin daily but not opioid analgesic medications. There were several differences between participants who reported non-prescribed opioid analgesic medication use, heroin use, or both substances. Those who reported non-prescribed opioid analgesic medication use but who had not used heroin tended to be older (median age: 34 years) than either group that used heroin (median age: 29, p = 0.03). Route of administration also differed: > 98% of participants who had used heroin reported injecting or snorting drugs in the month prior to treatment or jail, but only 81% of those misusing opioid analgesic medications reported injecting or snorting (p < 0.001). Personally experiencing an overdose in the past year was reported by 77% of the group who reported both non-prescribed opioid analgesic medication use and heroin use compared to approximately 60% of participants who had used one type of opioid (p = 0.01).

Prevalence of overdose risk behaviors

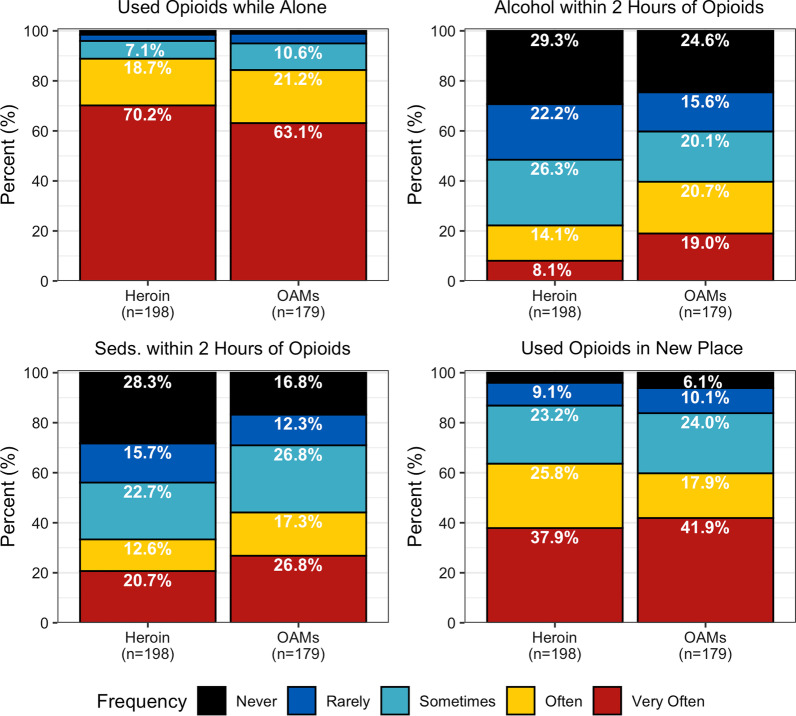

Among 179 participants who had reported non-prescribed opioid analgesic medication use, 63% reported using them while alone very often in the month before treatment or jail (Fig. 1). Only 1% (n = 2 participants) reported never using while alone, and only 4% (n = 7) rarely used while alone. Among 198 participants who had used heroin, 70% reported using heroin while alone very often in the month before treatment or jail. Only 2% (n = 3) reported never using heroin while alone and 3% (n = 5) reported rarely using heroin while alone.

Fig. 1.

Past-month frequency of overdose risk behaviors among a sample of people using opioids daily, 2014–2016

Among other overdose risk behaviors examined, concomitant opioid analgesic medication use with sedatives or drinking alcohol were more common than concomitant sedative use or drinking with heroin. Whereas 22% of participants reported that they often or very often drank alcohol within 2 h of using heroin, 40% reported often or very often drinking alcohol within 2 h of taking opioid analgesic medications. Similarly, whereas 33% often or very often used sedatives within 2 h of heroin, 44% often or very often used sedatives within 2 h of opioid analgesic medications. Finally, 60% of participants reported using opioids in a new setting or place often or very often, regardless of the type of opioid.

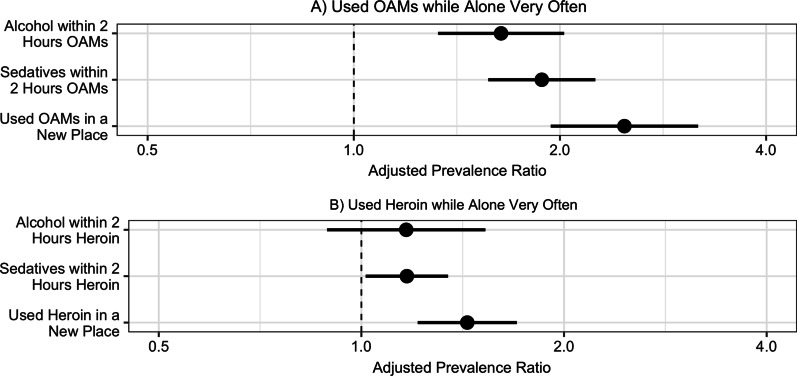

Associations of overdose risk behaviors with using opioid analgesic medications while alone

In bivariate (Additional file 1: Table S2) and adjusted analysis (Fig. 2), all three overdose risk behaviors examined were associated with using opioid analgesic medications while alone. Participants who reported drinking alcohol within two hours of using opioid analgesic medications very often (vs. often, sometimes, rarely, or never) were 60% more likely (aPR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.3–2.0) to report using opioid analgesic medications while alone very often after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and route of administration. Likewise, participants taking sedatives within two hours of opioid analgesic medications very often were 88% more likely (aPR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.6–2.3) to report using opioid analgesic medications while alone very often. Those who very often used opioid analgesic medications in a place they did not usually use them were 2.5-fold more likely (aPR: 2.5, 95% CI: 1.9–3.2) to report using opioid analgesic medications while alone very often. In a sensitivity analysis including those who “often” endorsed these behaviors with those who “very often” endorsed them, we found that these associations were attenuated, but similar in direction, suggesting that participants who endorsed using sedatives or using in a new place often or very often were also more likely to report using while alone often or very often (Additional file 1: Table S3). A sensitivity analysis including those who “sometimes” endorsed these behaviors with those who “often” or “very often” endorsed them resulted in further attenuated associations.

Fig. 2.

Overdose risk behaviors associated with using opioids while alone very oftena. Adjusted associations of engaging in several overdose risk behaviors very often (vs. less often or not at all) with using opioid analgesic medications (OAMs, panel A) and heroin (panel B) very often (vs. often, sometimes, rarely, or never). All overdose risk behaviors, including using while alone, were assessed in the past month. After adjustment for age, race, gender, and injecting or snorting any drug, participants who used alcohol or sedatives within two hours of OAMs very often and who used OAMs in a place they didn’t usually use them very often were more likely to also report using OAMs alone very often. After adjustment for age, race, gender, injecting or snorting, and ever experiencing an overdose, using sedatives or OAMs within two hours of using heroin very often and using heroin in a place they didn’t usually use heroin very often were more likely to also report using heroin alone very often. Abbreviations: OAMs: opioid analgesic medications. aOutcome modeled is those who used opioids Very Often vs. Often, Sometimes, Rarely, or Never

Associations of overdose risk behaviors with using heroin while alone

Two of the three overdose risk behaviors examined were associated with using heroin while alone in bivariate (Additional file 1: Table S4) and adjusted analysis (Fig. 2). Participants who took sedatives within two hours of using heroin very often were 17% more likely (aPR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.0–1.4) to also report using heroin while alone very often after adjustment for age, race, gender, route of administration, and ever experiencing an overdose. Further, those who reported using heroin in a new setting very often were 44% more likely (aPR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.2–1.7) to also use heroin while alone very often. Drinking alcohol within two hours of taking heroin was reported by fewer than 10% of participants who reported daily heroin use and was not associated with using while alone.

In sensitivity analyses, using sedatives often or very often (vs. sometimes, rarely, or never) was not associated with using heroin while alone often or very often (aPR: 1.0, 95% CI: 0.9–1.1, Additional file 1: Table S5). The association of using heroin in a new place often or very often (vs. sometimes, rarely, or never) with using while alone often or very often was attenuated by comparison to the main analysis (aPR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1–1.4). A sensitivity analysis including those who “sometimes” endorsed these behaviors with those who “often” or “very often” endorsed them resulted in similar associations.

Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of using any opioid while alone

In adjusted analysis, anticipated stigma and route of administration were associated with using heroin or opioid analgesic medications while alone very often (Table 2). Specifically, participants who scored in the top quartile on the fear of enacted stigma sub-scale (vs. those scoring < 75th percentile) were 20% more likely (aPR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.0–1.4) to report using any opioid while alone very often after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, type of opioid used, route of administration, personal overdose experience, and self-stigma. Further, participants who reported injecting or snorting drugs very often in the month before treatment were 71% more likely (aPR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.3–2.3) to report using opioids while alone very often. Other correlates we examined were not associated with using any opioid while alone very often in bivariate analyses, including symptoms of major depressive disorder, self-stigma score, predominantly living in temporary housing, or being married or co-habitating with a significant other.

Table 2.

Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of using any opioid while alone very often

| Covariate | Used opioids alone less frequently n (%) | Used opioids alone very often n (%) | Bivariate PR (95% CI) | Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 59 (24.5)a | 182 (75.5)a | – | – |

| Age, median (IQR) | 31 (27–45) | 30 (25–36) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

| Female gender | 18 (30.5) | 65 (35.7) | 1.06 (0.91–1.22) | 1.09 (0.95–1.25) |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 7 (11.9) | 12 (6.6) | ref | ref |

| White | 46 (78.0) | 144 (79.1) | 1.20 (0.84–1.71) | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) |

| Other | 6 (10.2) | 26 (14.3) | 1.29 (0.88–1.88) | 1.10 (0.77–1.56) |

| Temporary housing in past 3 Mos | 28 (47.5) | 105 (57.7) | 1.11 (0.95–1.28) | – |

| Married or living with someone | 13 (22.0) | 30 (16.5) | 0.91 (0.74–1.12) | – |

| High school, GED, or greater education | 49 (83.1) | 146 (80.2) | 0.96 (0.80–1.14) | – |

| Symptoms of major depressive disorder | 36 (61.0) | 106 (58.2) | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) | – |

| Heroin and OAM use, mo. before treat. or jail | ||||

| Used OAMs (No Heroin) ≥ 7 consecutive days | 16 (27.1) | 27 (14.8) | Ref | Ref |

| Used Heroin (No OAMs) ≥ 7 consecutive days | 21 (35.6) | 41 (22.5) | 1.05 (0.79–1.41) | 0.83 (0.61–1.12) |

| Used Heroin & OAMs ≥ 7 consecutive days | 22 (37.3) | 114 (62.6) | 1.33 (1.05–1.70) | 0.99 (0.75–1.31) |

| Injected or snorted any drug very often, mo. before treat. or jail | 26 (44.1) | 151 (83.0) | 1.76 (1.36–2.28) | 1.71 (1.30–2.26) |

| Experienced an overdose in lifetime | 48 (81.4) | 170 (93.4) | 1.49 (1.00–2.22) | 1.25 (0.89–1.76) |

| Experienced an overdose in the past year | 35 (59.3) | 131 (72.0) | 1.16 (0.98–1.38) | – |

| Witnessed an overdose in lifetime | 53 (89.8) | 163 (89.6) | 0.99 (0.79–1.25) | – |

| Self-stigma (self-devaluation Z-score), mean (SD) | − 0.02 (0.86) | 0.01 (1.04) | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | – |

| Self-stigma (self-devaluation score top quartile)b | 8 (13.6) | 43 (23.6) | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 0.94 (0.80–1.09) |

| Anticipated stigma (fear of enacted stigma Z-score), mean (SD) | − 0.20 (0.94) | 0.06 (1.01) | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | – |

| Anticipated stigma (fear of enacted stigma score top quartile)c | 6 (10.2) | 52 (28.6) | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) |

IQR: interquartile range; Mo: month; OAM: opioid analgesic medication; PR: prevalence ratio; SD: standard deviation; Treat: treatment

Outcome modeled is those who used opioids Very Often vs. Often, Sometimes, Rarely, or Never

aPercent among total n = 241

bTop quartile: ≥ 35 points

cTop quartile: ≥ 39 points

In sensitivity analyses (Additional file 1: Table S6), anticipated stigma was not associated with using any opioid while alone often or very often (aPR: 1.1, 95% CI: 1.0–1.2), nor was injecting or snorting drugs often or very often (aPR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.0–1.5). A sensitivity analysis analyzing predictors of using any opioid while alone sometimes, often, or very often was not possible, as only four participants reporting using both heroin and opioid analgesic medications while alone “never” or “rarely.”

Discussion

Frequently using opioids while alone was extremely common in this sample, as three-quarters of participants reported using heroin or opioid analgesic medications while alone very often. Using while alone increases the risk of fatal overdose, as solitary use precludes the possibility of a bystander response or call for emergency medical assistance. Participants who used while alone very frequently in our study were also more likely to endorse other overdose risk behaviors compared to those who used while alone less frequently. For example, concomitantly using opioids and sedatives was associated with using heroin or opioid analgesics while alone, a behavior that increases the likelihood that an overdose will occur due to drug–drug interactions [34–36]. We also found that anticipated stigma related to substance use was associated with frequently using while alone.

These results extend previous research. Estimates of the prevalence of using opioids while alone vary widely, from 7 to 81%, depending on the studied population [12–25]. The frequency of using while alone in our study was generally higher than prior research suggests. Most prior studies involved people who injected drugs and those recruited from syringe services or harm reduction programs primarily located in urban areas. Among those examining injecting while alone, 15% to 46% injected while alone at frequencies such as “always,” “all the time,” or “usually” [14, 21–23, 25]. To our knowledge, only one prior study evaluated how commonly people using drugs by any route of administration reported using opioids while alone. One study of Veterans who had recently used opioids (only 7% of whom used by injection at least once in the past month) found that 7% of participants used heroin while alone on at least half the days in the past month, and 17% took a higher dose of prescription opioids than advised while they were alone on at least half the days in the past month [12]. In our study, the vast majority of participants used while alone “very often,” including those using opioid analgesic medications and those who reported other overdose risk behaviors that could further raise the risk of overdose. These findings suggest that interventions aimed at reducing overdose harms related to solitary use might additionally be delivered beyond harm reduction settings, such as in substance use disorder treatment, pain clinics, emergency medical settings, or primary care. These settings could have greater reach to those engaging in non-prescribed use of opioid analgesic medications or located in rural or suburban communities that may have less access to harm reduction services. Using while alone and overdose have only become more prevalent during COVID-19 [13, 44], further emphasizing the potential need to reach more individuals.

One promising new tool that could reach those receiving services across these settings is overdose detection technologies, such as the Never Use Alone telephone hotline [45] and the Brave smartphone application [46]. These technologies set up virtual safer use spaces, similar to brick-and-mortar overdose prevention centers, which are just beginning to emerge and operate in a minimal number of places in the USA [47, 48]. These technologies connect callers about to use drugs with an operator who monitors and facilitates an emergency response if a caller becomes unresponsive. Our finding that using in a new setting was associated with using while alone very often further emphasizes the need for flexible and accessible overdose detection services, a need that telephone hotlines and smartphone applications may be capable of meeting. Rural or other communities where population dispersion makes sustaining substance use disorder treatment and harm reduction programs challenging may also be particularly well-served by these flexible overdose detection technologies.

This study extends a small number of prior qualitative studies [26, 49] supporting that anticipated stigma related to substance use is associated with frequently using opioids while alone. Anticipated stigma is the expectation that one will be rejected, mistreated, or devalued in the future if their identity as a person who uses drugs is found out [31, 50]. Though few studies have focused on stigma and using while alone specifically, prior research exploring reasons underlying preferences to maintain privacy while using drugs may help to explain this relationship. These include distrust of peers or police, the need to be discrete and use quickly to avoid being interrupted or found out, fear of violence or exploitation, and emotional pain [26, 32, 49, 51–55]. These reasons further codify the fundamental role stigma plays in raising overdose risk [31, 56]. Beyond stigma, many people who use drugs while alone do so for highly practical reasons, such as the inability to afford sharing drugs or a preference for using in a convenient and comfortable space [20, 26, 51]. Encouragingly, both of the aforementioned overdose detection technologies we suggest above as a flexible intervention to reduce harms among those engaging in solitary use emphasize a non-stigmatizing environment involving acceptance and respect for privacy in recognition of stigma and fear of punishment as barriers to safer drug use. For example, Never Use Alone’s tagline is, “No judgement, no shaming, no preaching, just love!”.

We also found that polysubstance use was associated with using opioids while alone, further increasing risk of fatal and non-fatal overdose [33–36]. Specifically, using opioids and sedatives (e.g., Xanax) within two hours of one another very often was associated with using opioid analgesic medications or heroin while alone very often, and drinking within two hours of taking opioid analgesic medications very often was associated with using opioid analgesic medications while alone very often. These associations were generally stronger in magnitude among those using opioid analgesic medications than those using heroin, suggesting that overdose harm reduction messaging may not adequately reach those engaging in non-medical use of opioid analgesic medications. Education efforts to reduce or stagger polysubstance use and publicizing overdose detection services beyond harm reduction venues may thus assist in reducing risk among these individuals. Professionals working in settings frequented by people engaging in non-medical use of opioid analgesic medications, such as pharmacies, emergency medical settings, primary care, substance use disorder treatment settings, and pain clinics would further be well-positioned to engage clients in discussions about overdose risk and provide tools like naloxone that reduce harm. Outreach to individuals who recently survived an overdose through community-based mobile response teams offer additional opportunities to deliver harm reduction tools to these individuals and their peer networks as well as connect them with services like substance use treatment [57, 58]. Given the recent uptick in fentanyl contamination of illicitly manufactured pills sold as opioid analgesic medications, this is essential now more than ever [59, 60].

Our study has several limitations. First, the data were collected during 2014–2016, just as illicitly manufactured fentanyl began contaminating the US drug supply, and prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent study suggests the potential that using fentanyl may be associated with using while alone [16], highlighting the importance of this study and further research on this topic. Our study was also a cross-sectional, secondary analysis of people sampled while receiving treatment for a substance use disorder. Thus, we cannot rule out reverse causation (e.g., stigma could result in using alone or vice versa) or assume that the results are generalizable to other populations, though we provide detailed data on substances used in the sample to assist with comparisons to other samples. We additionally aimed to define a sample who used opioids frequently so that using while alone “never” was not conflated with not using opioids at all. However, we were limited in the questions available to define the sample in this secondary analysis. Subsequent research designed to examine using while alone specifically will be able to more rigorously define who is at risk of overdose while alone. We also report on associations between reported overdose risk behaviors (e.g., drinking while taking opioids and using opioids while alone) but cannot comment on whether these behaviors truly co-occurred in the same drug using episode, which would only be possible with detailed, event-level data collected by techniques like ecological momentary assessment. Our results were further sensitive to the frequency threshold (i.e., very often, often, or sometimes) used to create indicators of using while alone and other overdose risk behaviors. Further study of the frequency of these behaviors is needed. Finally, we did not collect and thus could not analyze several key covariates, including those related to motivations for using alone (e.g., economic concerns, withdrawal, suicidal ideation, convenience) or other key factors such as whether the participant resided in a rural versus urban location.

Conclusions

Recently using opioids while alone was highly common in this sample of people with a history of daily opioid use. Endorsing other overdose risk behaviors very often, such as using sedatives within two hours of opioids, was associated with using opioids while alone very often. Anticipated stigma may also be associated with using opioids while alone. These findings highlight the need for enhanced overdose harm reduction options for people engaging in solitary opioid use, including those using heroin or non-prescribed opioid analgesic medications. This need may be met by broadening the use of novel overdose detection options, such as the Never Use Alone hotline or Brave smartphone application.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplemental Tables S1 (questions from the Substance Abuse Self-Stigma Scale used in the study) and S2–S6 (supplemental results from sensitivity analyses).

Acknowledgements

We thank Emily Yeagley and Laura Thomas for providing project oversight and Mary Jannausch for collating data. We also thank the participants and staff at the addiction treatment facility who facilitated this research.

Abbreviations

- aPR

Adjusted prevalence ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COMM

Current opioid misuse measure

Author contributions

ASBB conceptualized the study, obtained funding, and collected data. REG conducted analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors conceptualized the analysis design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The parent study and ASBB were supported by DA035331. REG and JLM were supported by AI102623. REG and BLG were supported by AI094189. ACF was supported by AA023869.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (HUM00078507). All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wakeman SE, Green TC, Rich J. An overdose surge will compound the COVID-19 pandemic if urgent action is not taken. Nat Med Nature Publishing Group. 2020;26:819–820. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0898-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.British Columbia Coroners Service Death Review Panel. A Review of Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths [Internet]. 2022 Mar p. 1–60. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/review_of_illicit_drug_toxicity_deaths_2022.pdf

- 3.Darke S, Ross J, Zador D, Sunjic S. Heroin-related deaths in New South Wales, Australia, 1992–1996. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:141–150. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darke S, Duflou J. The toxicology of heroin-related death: estimating survival times. Addiction. 2016;111:1607–1613. doi: 10.1111/add.13429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson PJ, McLean RL, Kral AH, Gleghorn AA, Edlin BR, Moss AR. Fatal heroin-related overdose in San Francisco, 1997–2000: a case for targeted intervention. J Urban Health. 2003;80:261–273. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerostamoulos J, Staikos V, Drummer OH. Heroin-related deaths in Victoria: a review of cases for 1997 and 1998. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61:123–127. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynn TM, Lynn E, Keenan E, Lyons S. Trends in injector deaths in ireland, as recorded by the national drug-related deaths index, 1998–2014. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79:286–292. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and u-47700 - 10 states, July-December 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1197–1202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6643e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stam NC, Gerostamoulos D, Smith K, Pilgrim JL, Drummer OH. Challenges with take-home naloxone in reducing heroin mortality: a review of fatal heroin overdose cases in Victoria, Australia. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;1–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wojcicki JM. Dying alone: the sad irrelevance of naloxone in the context of solitary opiate use. Addiction. 2019;114:574–575. doi: 10.1111/add.14508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bmore Power. Fentanyl is here. Go slow. Have a plan. 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. https://www.goslow.org/

- 12.Bennett AS, Golub A, Elliott L. A behavioral typology of opioid overdose risk behaviors among recent veterans in New York City. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0179054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genberg BL, Astemborski J, Piggott DA, Woodson-Adu T, Kirk GD, Mehta SH. The health and social consequences during the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic among current and former people who inject drugs: A rapid phone survey in Baltimore. Maryland Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108584. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagan H, Campbell JV, Thiede H, Strathdee SA, Ouellet L, Latka M, et al. Injecting alone among young adult IDUs in five US cities: evidence of low rates of injection risk behavior. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(Suppl 1):S48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi K, Wood E, Dong H, Buxton JA, Fairbairn N, DeBeck K, et al. Awareness of fentanyl exposure and the associated overdose risks among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Karamouzian M, Papamihali K, Graham B, Crabtree A, Mill C, Kuo M, et al. Known fentanyl use among clients of harm reduction sites in British Columbia. Canada Int J Drug Policy. 2020;77:102665. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuat OTH, Morrow M, Nguyen TNN, Armstrong G. Social context, diversity and risk among women who inject drugs in Vietnam: descriptive findings from a cross-sectional survey. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12:35. doi: 10.1186/s12954-015-0067-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latkin CA, Dayton L, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE. Fentanyl and drug overdose: perceptions of fentanyl risk, overdose risk behaviors, and opportunities for intervention among people who use opioids in Baltimore, USA. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Morissette C, Cox J, De P, Tremblay C, Roy E, Allard R, et al. Minimal uptake of sterile drug preparation equipment in a predominantly cocaine injecting population: implications for HIV and hepatitis C prevention. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papamihali K, Yoon M, Graham B, Karamouzian M, Slaunwhite AK, Tsang V, et al. Convenience and comfort: reasons reported for using drugs alone among clients of harm reduction sites in British Columbia. Canada Harm Reduct J. 2020;17:90. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouhani S, Park JN, Morales KB, Green TC, Sherman SG. Harm reduction measures employed by people using opioids with suspected fentanyl exposure in Boston, Baltimore, and Providence. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16:39. doi: 10.1186/s12954-019-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vazan P, Mateu-Gelabert P, Cleland CM, Sandoval M, Friedman SR. Correlates of staying safe behaviors among long-term injection drug users: psychometric evaluation of the staying safe questionnaire. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1472–1481. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wechsberg WM, Cavanaugh ER. Differences found between women injectors in and out of treatment: implications for interventions. Drugs Soc. 1998;13:63–79. doi: 10.1300/J023v13n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, Li K, Kerr T, Hogg RS, et al. Unsafe injection practices in a cohort of injection drug users in Vancouver: could safer injecting rooms help? CMAJ. 2001;165:405–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahnow R, Winstock AR, Maier LJ, Levy J, Ferris J. Injecting drug use: gendered risk. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;56:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winiker AK, Tobin KE, Gicquelais RE, Owczarzak J, Latkin C. When you’re getting high… you just don’t want to be around anybody. A qualitative exploration of reasons for injecting alone: perspectives from young people who inject drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55:2079–86. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2020.1790008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bohnert ASB, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Ilgen MA, Barry K, Chermack ST, et al. Overdose and adverse drug event experiences among adult patients in the emergency department. Addict Behav. 2018;86:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gicquelais RE, Jannausch M, Bohnert ASB, Thomas L, Sen S, Fernandez AC. Links between suicidal intent, polysubstance use, and medical treatment after non-fatal opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;212:108041. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latkin CA, Gicquelais RE, Clyde C, Dayton L, Davey-Rothwell M, German D, et al. Stigma and drug use settings as correlates of self-reported, non-fatal overdose among people who use drugs in Baltimore. Maryland Int J Drug Policy. 2019;68:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fendrich M, Becker J, Hernandez-Meier J. Psychiatric symptoms and recent overdose among people who use heroin or other opioids: Results from a secondary analysis of an intervention study. Addict Behav Rep. 2019;10:100212. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, Beletsky L, Keyes KM, McGinty EE, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med. 2019 [cited 2021 May 23];16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6957118/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: evidence from an ethnographic investigation. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White JM, Irvine RJ. Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose. Addiction. 1999;94:961–972. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Day C. Benzodiazepines in combination with opioid pain relievers or alcohol: greater risk of more serious ED visit outcomes. The CBHSQ Report [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2013 [cited 2022 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384672/ [PubMed]

- 35.Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Alcohol involvement in opioid pain reliever and benzodiazepine drug abuse-related emergency department visits and drug-related deaths - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:881–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones CM, McAninch JK. Emergency department visits and overdose deaths from combined use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gicquelais RE, Mezuk B, Foxman B, Thomas L, Bohnert ASB. Justice involvement patterns, overdose experiences, and naloxone knowledge among men and women in criminal justice diversion addiction treatment. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16:46. doi: 10.1186/s12954-019-0317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashrafioun L, Bohnert ASB, Jannausch M, Ilgen MA. Evaluation of the current opioid misuse measure among substance use disorder treatment patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;55:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, et al. Development and validation of the current opioid misuse measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez AC, Bush C, Bonar EE, Blow FC, Walton MA, Bohnert ASB. Alcohol and drug overdose and the influence of pain conditions in an addiction treatment sample. J Addict Med. 2019;13:61–68. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luoma JB, Nobles RH, Drake CE, Hayes SC, O’Hair A, Fletcher L, et al. Self-stigma in substance abuse: development of a new measure. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2013;35:223–234. doi: 10.1007/s10862-012-9323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose Deaths Accelerating During COVID-19 [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 23]. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html

- 45.Never Use Alone [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 22]. https://neverusealone.com/

- 46.Brave Cooperative. BRAVE [Internet]. BRAVE. [cited 2022 Mar 22]. https://www.brave.coop

- 47.Harocopos A, Gibson BE, Saha N, McRae MT, See K, Rivera S, et al. First 2 months of operation at first publicly recognized overdose prevention centers in US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2222149. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kral AH, Lambdin BH, Wenger LD, Davidson PJ. Evaluation of an unsanctioned safe consumption site in the United States. New Engl J Med. 2020;383:589–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins AB, Boyd J, Czechaczek S, Hayashi K, McNeil R. (Re)shaping the self: an ethnographic study of the embodied and spatial practices of women who use drugs. Health Place. 2020;63:102327. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:96–112. doi: 10.2307/2095395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bardwell G, Boyd J, Kerr T, McNeil R. Negotiating space & drug use in emergency shelters with peer witness injection programs within the context of an overdose crisis: a qualitative study. Health Place. 2018;53:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang JS, Behar E, Coffin PO. Narratives of people who inject drugs on factors contributing to opioid overdose. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;74:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cruz MF, Mantsios A, Ramos R, Case P, Brouwer KC, Ramos ME, et al. A qualitative exploration of gender in the context of injection drug use in two US-Mexico border cities. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:253–262. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore D. Governing street-based injecting drug users: a critique of heroin overdose prevention in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rhodes T, Watts L, Davies S, Martin A, Smith J, Clark D, et al. Risk, shame and the public injector: a qualitative study of drug injecting in South Wales. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:572–585. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:813–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagner KD, Oman RF, Smith KP, Harding RW, Dawkins AD, Lu M, et al. “Another tool for the tool box? I’ll take it!”: feasibility and acceptability of mobile recovery outreach teams (MROT) for opioid overdose patients in the emergency room. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;108:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canada M, Formica S. Implementation of a post-overdose quick response team in the rural Midwest: a team case study. J Commun Saf Well-Being. 2022;7:59–66. doi: 10.35502/jcswb.233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Counterfeit prescription pills containing fentanyls: a global threat. 2016 Jul p. 9. Report No.: DEA-DCT-DIB-021–16. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/docs/Counterfeit%2520Prescription%2520Pills.pdf

- 60.United States Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA Issues Public Safety Alert on Sharp Increase in Fake Prescription Pills Containing Fentanyl and Meth [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 23]. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2021/09/27/dea-issues-public-safety-alert

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplemental Tables S1 (questions from the Substance Abuse Self-Stigma Scale used in the study) and S2–S6 (supplemental results from sensitivity analyses).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.