Abstract

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a major pathogen associated with adult periodontitis. We cloned and sequenced the gene (dpp) coding for dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV (DPPIV) from P. gingivalis W83, based on the amino acid sequences of peptide fragments derived from purified DPPIV. An Escherichia coli strain overproducing P. gingivalis DPPIV was constructed. The enzymatic properties of recombinant DPPIV purified from the overproducer were similar to those of DPPIV isolated from P. gingivalis. The three amino acid residues Ser, Asp, and His, which are thought to form a catalytic triad in the C-terminal catalytic domain of eukaryotic DPPIV, are conserved in P. gingivalis DPPIV. When each of the corresponding residues of the enzyme was substituted with Ala by site-directed mutagenesis, DPPIV activity significantly decreased, suggesting that these three residues of P. gingivalis DPPIV are involved in the catalytic reaction. DPPIV-deficient mutants of P. gingivalis were constructed and subjected to animal experiments. Mice injected with the wild-type strain developed abscesses to a greater extent and died more frequently than those challenged with mutant strains. Mice injected with the mutants exhibited faster recovery from the infection, as assessed by weight gain and the rate of lesion healing. This decreased virulence of mutants compared with the parent strain suggests that DPPIV is a potential virulence factor of P. gingivalis and may play important roles in the pathogenesis of adult periodontitis induced by the organism.

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a gram-negative anaerobic bacterium, is thought to be a major etiologic agent associated with adult periodontitis (13, 15). It produces several proteases, two Arg-specific cysteine proteases and a Lys-specific one, dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV (DPPIV), prolyl tripeptidyl peptidase (PtpA), and others (1, 4, 26, 32). Arg-specific proteases have been implicated in the pathogenesis of adult periodontitis, as shown by genetic approaches (12, 28, 29, 37, 39).

DPPIV (EC 3.4.14.5) is a serine protease that cleaves X-Pro or X-Ala dipeptide from the N-terminal ends of polypeptide chains. DPPIV activity has been found in eukaryotes as well as in bacteria. The genes coding for DPPIV have been cloned and sequenced for some of these organisms (e.g., human [7, 25, 38], mouse [22], Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 35], Chryseobacterium [formerly Flavobacterium] meningosepticum [17]), and P. gingivalis [18]).

Eukaryotic DPPIV has been reported to be associated with several biological functions—e.g., (i) T-cell activation (3, 22, 27, 38, 43), (ii) binding to adenosine deaminase (ADA) (3, 10, 11, 16, 27, 43), and (iii) interaction with collagen and/or fibronectin (3, 6, 33)—as well as with the pathogenesis of diseases, such as AIDS, breast cancer, and diabetes (3, 6, 14, 31, 45). In contrast, the physiological and pathological functions of bacterial DPPIV have not been clarified.

Destruction of periodontal tissue is a critical feature of adult periodontitis. Type I collagen, one of the major components of periodontal tissue, is composed predominantly of Gly-Pro-X. P. gingivalis DPPIV has been suggested to contribute to the degradation of collagen, based on the fact that partially purified DPPIV possessed the activity of releasing the Gly-Pro peptide from Clostridium histolyticum collagenase-treated type I collagen (1). However, the detailed mechanism by which DPPIV participates in the destruction of collagen remains unclear. Considering the functions of eukaryotic DPPIV, P. gingivalis DPPIV was supposed to have some biological roles or to be pathologically associated with periodontitis. In the present study, we demonstrate through animal experiments with DPPIV-deficient mutants that P. gingivalis DPPIV is a potential virulence factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The bacterial strains used in this study are described in Table 1. P. gingivalis was grown anaerobically (80% N2, 10% CO2, 10% H2) in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) or on BHI agar plates supplemented with 5 μg of hemin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml and 0.5 μg of menadione (Sigma-Aldrich) per ml. For animal experiments, P. gingivalis was grown as previously described (12). Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar plates. SY327λpir (24), λpir lysogen of SY327, was the host for transformation with plasmids containing the R6K replicon, pGP704 (24), and its derivatives. SM10λpir (24) was used for conjugal transfer of pGP704 derivatives. BL21 (36) was the host for pTD-T7 (8) and its derivatives, and DH1 (36) was the host for transformation with other plasmids. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations for E. coli: ampicillin sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/ml; kanamycin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/ml; erythromycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 300 μg/ml; and gentamicin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg/ml. For P. gingivalis, 10 μg of erythromycin per ml was added as required.

TABLE 1.

List of strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | ||

| W83 | Laboratory stock | |

| 4351 | W83 Δdpp | Present study |

| 4361 | W83 Δdpp | Present study |

| EM23 | W83 dpp::φ (ermF-ermAM) | Present study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| SY327λpir | Δ(lac pro) argE(Am) rif nalA recA56 pir | 24 |

| SM10λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu Km pir | 24 |

| BL21 | hsdS gal (λcIts857 ind1 Sam7 nin5 lacUV5-T7 gene1) | 36 |

| DH1 | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 36 |

| DPPRWT | BL21/pYKP406 | Present study |

| DPPRSA | BL21/pYKP407 | Present study |

| DPPRDA | BL21/pYKP408 | Present study |

| DPPRHA | BL21/pYKP409 | Present study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC119 | Apr | 36 |

| pUC4K | Apr Kmr | 42 |

| pGP704 | oriR6K mobRP4 Apr | 24 |

| pTD-T7 | Apr T7 promoter | 8 |

| pYKP001 | pVA2198 Kmr | Present study |

| pYKP002 | pGP704 φ(ermF-ermAM) Aps | Present study |

| pYKP009 | pGP704 φ(ermF-ermAM) Aps; one SphI site was eliminated | Present study |

| pYKP200 | pYKP009 ALAR fragment | Present study |

| pYKP300 | pBR322 dpp | Present study |

| pYKP301 | pYKP300 dpp::φ (ermF-ermAM) | Present study |

| pYKP403 | pTD-T7 dpp coding for DPPIV with a putative signal sequence | Present study |

| pYKP406 | pTD-T7 dpp coding for DPPIV without a putative signal sequence | Present study |

| pYKP407 | pTD-T7 dpp expressing S593A | Present study |

| pYKP408 | pTD-T7 dpp expressing D668A | Present study |

| pYKP409 | pTD-T7 dpp expressing H700A | Present study |

Apr, ampicillin resistant; Aps, ampicillin sensitive; Kmr, kanamycin resistant, oriR6K, replication origin of plasmid R6K; mobRP4, oriT region of plasmid RP4.

Purification of DPPIV from P. gingivalis W83.

DPPIV activity was measured with 0.5 mM glycylprolyl p-nitroanilide (Gly-Pro-pNA) (Peptide Institute, Inc., Osaka, Japan) as a substrate in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) at 25°C, and released p-nitroaniline was spectrophotometrically monitored at 405 nm. P. gingivalis W83 was harvested at the stationary phase. Cells were washed with 10 mM potassium phosphate–1 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.5), resuspended in the same buffer, frozen-thawed, sonicated with an Ultrasonic Generator (Nihonseiki, Tokyo, Japan), and centrifuged at 70,000 × g for 1 h. The resulting supernatant was fractionated on a DEAE-Sephacel column (Amersham Pharmacia, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) that had been equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate–1 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.5). Retained proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 50 to 120 mM NaCl in 10 mM potassium phosphate–1 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.5). Pooled active fractions were concentrated with an Ultrafree C3-LGC centrifugal filter unit (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) and applied to a Sephacryl S-300 HR column (Amersham Pharmacia) that had been equilibrated with 20 mM potassium phosphate–100 mM NaCl–1 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.5), followed by elution with the same buffer. Ammonium sulfate was added to the pooled active fractions at a final concentration of 1.5 M (35% saturation), and the fractions were then applied to a butyl-Sepharose column (Amersham Pharmacia) that had been equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate–1 mM EDTA–1.5 M ammonium sulfate buffer (pH 7.5), followed by elution with a linear gradient of 1.5 to 0 M ammonium sulfate in 10 mM potassium phosphate–1 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.5). Combined active fractions were finally applied to a hydroxyapatite column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) that had been equilibrated with 150 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and retained proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 150 to 300 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The purity of proteins was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (20). The protein concentration was determined with bovine serum albumin as a standard by use of the BCA (bicinchoninic acid) Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

DNA manipulation.

DNA was extracted from agarose gels with the Geneclean II Kit (Bio 101, Inc., Vista, Calif.). Transformation of E. coli with plasmids was performed by electroporation with a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad). Preparation of DNA probes, colony hybridization, and Southern hybridization were carried out with the DIG (digoxigenin) DNA Labeling and Detection Kit (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). A series of deletion mutants for DNA sequencing were prepared with the Kilo-Sequence Deletion Kit (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan). Sequencing was performed with the AutoRead Sequencing Kit (Amersham Pharmacia), followed by analysis with an A.L.F.DNA Sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia). Other methods were as described previously (36).

Isolation and sequencing of the gene coding for DPPIV.

When we began and completed sequencing the gene coding for DPPIV, no sequence information was available for DPPIV from any strains of P. gingivalis, including 381 (18) and W83. Therefore, we used amino acid sequences of the purified enzyme to obtain information for cloning. The N-terminal amino acid sequence could not be determined after several attempts. Instead, internal amino acid sequences were determined as follows. The purified enzyme was digested with lysyl endopeptidase (Wako, Osako, Japan) at a 200:1 (mol/mol) ratio at 25°C for 20 h, and the resulting peptides were isolated by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (ODS-120T; Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) with a linear gradient of 0 to 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min. The sequences of the nine fragments were automatically determined with a PPSQ-10 gas-phase peptide sequencer system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Since two of the nine peptides exhibited high homology with other eukaryotic DPPIVs in a search of the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database, primers for PCR were designed based on the sequences of the peptide fragments as follows: 5′-CCGGATCCGA (C/T)GG(A/C/G/T)(A/C/T)G(A/C/G/T)ATGGT(A/C/G/T)GC-3′, containing a BamHI site (underlined), and 5′-GGCTGCAGTC(G/A)TA(G/A)AA(A/C/G/T)C(T/G)CCA(G/A)TC(A/C/G/T)GC-3′, containing a PstI site (underlined). PCR was performed with P. gingivalis W83 chromosomal DNA as the template. The resulting 1.5-kbp PCR fragment was used as a probe to screen a plasmid library made by partially digesting P. gingivalis chromosomal DNA with MboI and ligating the DNA to pUC119 digested with BamHI by colony hybridization. Three overlapping DNA fragments derived from a single gene, as demonstrated by restriction endonuclease analysis, were isolated. Southern blotting revealed that one copy of the gene exists on the chromosome (data not shown). We combined the sequence data for the three clones and obtained a complete sequence.

Construction of E. coli strains harboring expression vectors for P. gingivalis wild-type DPPIV protein and mutant proteins.

A DNA fragment containing the dpp gene was generated by PCR with W83 chromosomal DNA as the template and with the following primers: ML1, 5′-GGGTCGACCATCGTAACCATGTGTGCC-3′, with a SalI site (underlined) beginning at base 33 from the translation initiation codon, and OPR3, 5′-CCGCATGCCTGTATTAAAGATTGTCG-3′, with an SphI site (underlined) ending 5 bp downstream from the stop codon. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with SalI and SphI and ligated to SalI- and SphI-digested pTD-T7 (8) to yield pYKP403. To construct the plasmid for overproducing wild-type DPPIV, pYKP406, “loop-out” mutagenesis was performed by the Kunkel method (19) with primer DP4MQ-2 (5′-TTTGTTCCCCGTCTGCATAGCTGTTTCCTG-3′) according to the instruction manual for Mutan-K (TaKaRa). BL21 was transformed with pYKP406 to create strain DPPRWT. pYKP407 for producing mutant DPPIV protein S593A, pYKP408 for producing D668A, and pYKP409 for producing H700A were created by the Kunkel method (19) with primers DPP4S (5′-GCCGCCATAGGCCCACCCCCA-3′), DPP4D (5′-AACATTGTCGGCTGCCGATCC-3′), and DPP4H-2 (5′-CCCGTATATACTAGCGTTCTTGTCCAT-3′), respectively. BL21 was transformed with these plasmids to produce strains DPPRSA, DPPRDA, and DPPRHA, respectively (Table 1).

Purification of DPPIV from the overproducers.

A 1/20 portion of overnight cultures of E. coli overproducers was added to LB broth without glucose and incubated aerobically at 30°C for 3 h. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to each culture at a final concentration of 0.1 mM, and the cultures were incubated aerobically at 30°C for 4 h. Cells were harvested, resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), frozen-thawed, sonicated with an Ultrasonic Generator, and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was diluted threefold and subjected to chromatography on a hydroxyapatite column equilibrated with 0.2 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). After the column was washed with the same buffer, retained proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0.2 to 0.6 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). The protein concentration and kinetic constants of the purified enzyme were determined.

Antiserum against P. gingivalis DPPIV was prepared by immunizing a rabbit with the wild-type DPPIV sample purified from strain DPPRWT as an antigen according to a previously described method (36). Western blotting was performed as described previously (36).

Binding of DPPIV to ADA.

Binding of P. gingivalis DPPIV or human DPPIV to ADA was investigated by use of modifications of the procedure described by Iwaki-Egawa et al. (16). Briefly, samples of P. gingivalis DPPIV or human DPPIV (1 μg) were incubated with calf intestine mucosa ADA (1 μg) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer. For electrophoresis under nondenaturing conditions, human DPPIV reaction mixtures were loaded onto a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel (NOVEX, San Diego, Calif.) and P. gingivalis DPPIV reaction mixtures were loaded onto a 50 mM Tris-HCl nondenaturing gel (pH 8.8) or onto an isoelectric focusing gel (pH 3 to 10) (NOVEX). Proteins on gels were detected by Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining and by Western blotting with anti-ADA antibody and anti-P. gingivalis DPPIV antibody. ADA affinity column chromatography was performed as previously described (10), except for the detergents.

Construction of dpp mutants of P. gingivalis.

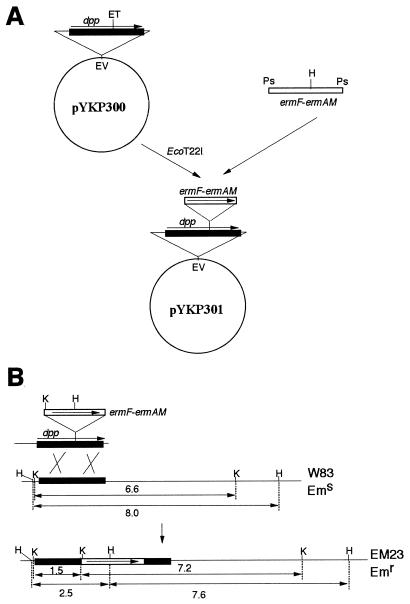

dpp null mutants were constructed as depicted in Fig. 1. The EcoRI fragment of pUC4K (42) containing the kanamycin resistance gene was inserted into the EcoRI site of pVA2198 (12) to yield pYKP001. The PstI fragment containing the ermF-ermAM cassette, which confers erythromycin resistance (Emr) to both P. gingivalis and E. coli (12), was ligated to the PstI site of suicide vector pGP704 (24). The resulting plasmid, pYKP002, was digested with KpnI to eliminate one of the two SphI sites and self-ligated to generate pYKP009. pYKP002 and pYKP009 possess several cloning sites, including SphI and SacI, and are suicide vectors transferable to P. gingivalis and selectable for the Emr phenotype when inserted into P. gingivalis chromosomal DNA. A derivative of pYKP009, pYKP200, which possesses a fused fragment ALAR of the flanking regions with the reading frame of dpp deleted (Fig. 1A), was created to construct null mutants.

FIG. 1.

Isolation of dpp null mutants. (A) Construction of plasmid pYKP200. Details are described in Materials and Methods. (B) One of the recombination events leading to dpp null mutants. Lengths of restriction fragments are shown in kilobases. Abbreviations: kan, the aminoglycoside 3′-phosphotransferase gene conferring kanamycin resistance; bla, the β-lactamase gene; ori R6K, replication origin of plasmid R6K; mob RP4, oriT region of plasmid RP4; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; Ps, PstI; Pv, PvuII; Sa, SacI; Sp, SphI; Emr, erythromycin resistant; Ems, erythromycin sensitive.

The fragment containing the flanking regions was generated by PCR with P. gingivalis W83 chromosomal DNA as the template. The AL fragment (463 bp), located upstream of dpp (positions −511 to −49 from the translation initiation codon), was generated with primer AL1, 5′-GGGCATGCTATCCACAACTATGAAAGAG-3′, with an SphI site (underlined), and primer AL2, 5′-CCCAGCTGCAATGCACGATCCATCTCTC-3′, with a PvuII site (underlined). The AR fragment (422 bp), located downstream of the dpp gene, including 135 bp of the 3′ coding region, was amplified with primer AR1, 5′-GGCAGCTGACAGAGGCACTGGTTCAGGC-3′, containing a PvuII site (underlined), and primer AR2, 5′-CCGAGCTCATCACCACCGATCATGAAGG-3′, containing a SacI site (underlined). The AL and AR fragments were digested with SphI/PvuII and SacI/PvuII, respectively. PCR was performed with a mixture of both the AL and the AR fragments as templates and with primers AL1 and AR2. The resulting ALAR fragment was digested with SphI and SacI and ligated with SphI- and SacI-digested pYKP009 to yield pYKP200 (Fig. 1A).

SM10λpir was transformed with pYKP200, and the plasmid was then transferred to P. gingivalis W83 by selection with erythromycin and counterselection with gentamicin as described elsewhere (28), with some modifications. Emr transconjugants of P. gingivalis W83 thus formed were purified and grown successively in BHI broth to obtain erythromycin-sensitive (Ems) colonies, which were then purified and examined by PCR, Southern hybridization, and Western blotting to confirm that the fragment consisting of the vector and the dpp gene had been lost. Two null mutants, 4351 and 4361, were thus isolated.

The dpp gene insertion mutant, EM23, was constructed as shown in Fig. 2. The EcoRV fragment containing the dpp gene was cloned from W83 chromosomal DNA by colony hybridization with pBR322 as the vector to create pYKP300. The PstI fragment of pYKP001 mentioned above (Fig. 1A) and containing the ermF-ermAM cassette was ligated with pYKP300 digested with EcoT22I, resulting in pYKP301. pYKP301 was linearized by EcoRV digestion, and the EcoRV fragment containing both the dpp gene and the ermF-ermAM cassette was introduced into P. gingivalis W83 by electroporation as previously described (12). Erythromycin was used as a selection marker instead of clindamycin. Except for spontaneous mutants, Emr colonies should have arisen only when the ermF-ermAM cassette was inserted into the dpp gene on the chromosome as a result of a double-crossover event, since the introduced DNA cannot replicate in W83 (Fig. 2B). Emr transformants thus obtained were purified and confirmed to have no DPPIV activity. One of the mutants was designated EM23.

FIG. 2.

Insertion mutation of the dpp gene. (A) Plasmid pYKP301, constructed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Double-crossover event leading to an insertion mutation between W83 chromosomal DNA and the EcoRV fragment excised from pYKP301. Lengths of restriction fragments are shown in kilobases. Abbreviations: ET, EcoT22I; EV, EcoRV; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; Ps, PstI; Emr, erythromycin resistant; Ems, erythromycin sensitive.

Animal experiments.

W83 and DPPIV-deficient mutants were grown until the early stationary phase. The growth phase was judged by measuring the optical densities of cultures. Cells were harvested and washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and W83 and the mutants were adjusted to the same cell concentrations in phosphate-buffered saline. Numbers of viable cells were counted by spreading the cultures on BHI agar plates, and we confirmed the absence of contamination. BALB/c mice (11 weeks) were challenged with a dorsal subcutaneous injection of 0.2 ml of bacterial suspension. General health, weight, and presence and location of lesions were assessed daily. Statistical significance of differences in lesion formation and lethality caused by injection of W83 and mutant strains was examined by Fisher's exact probability test.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DDBJ accession no. assigned to the dpp gene of P. gingivalis W83 is AB008194.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of DPPIV protein from P. gingivalis.

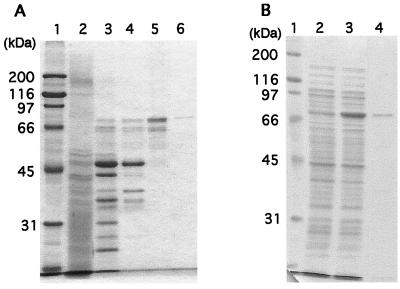

More than 90% of the DPPIV activity was found in the supernatant (hereafter referred to as the soluble fraction) after sonication and centrifugation. No DPPIV activity was found in the culture fluids. The enzyme was purified to about 1,000-fold from the soluble fraction and reached homogeneity (Fig. 3A). Nineteen micrograms of the purified enzyme was obtained from 1.5 liters of bacterial culture.

FIG. 3.

CBB-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels showing purification of DPPIV from P. gingivalis W83 (A) and expression and purification of recombinant DPPIV (B). (A) Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lane 2, crude extract; lane 3, DEAE-Sephacel column; lane 4, Sephacryl S-300 HR column; lane 5, butyl-Sepharose column; lane 6, hydroxyapatite column. (B) Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lanes 2 and 3, crude extracts of BL21/pTD-T7 (lane 2) and DPPRWT (BL21/pYKP406) (lane 3) harvested after incubation at 30°C for 4 h in the presence of 0.1 mM IPTG; lane 4, sample from DPPRWT after purification though a hydroxyapatite column.

The purified enzyme exhibited a 78-kDa single band in SDS-PAGE. When the sample was chromatographed on an HPLC gel filtration column (TSK gel G3000SWXL; Tosoh) under nondenaturing conditions, the retention time was at a position corresponding to a molecular mass of 140 kDa (data not shown). The Km and Vmax values were estimated to be 0.28 mM and 18 μmol/min/mg, respectively, with Gly-Pro-pNA as a substrate. The range of optimum pH of the enzyme was 7.5 to 8.5, with the highest activity occurring at pH 8.0. After incubation at 50°C for 30 min, 70% of the enzyme activity remained. DPPIV activity was not affected by 5 mM dithiothreitol.

Isolation and sequencing of the gene coding for DPPIV.

By the methods described in Materials and Methods, we isolated and sequenced the gene coding for DPPIV, designated dpp, which was composed of a coding region of 2,169 nucleotides. The open reading frame encodes a protein of 723 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 81.8 kDa. This value is in good agreement with that estimated by SDS-PAGE (78 kDa). The deduced amino acid sequence contains sequences of the nine peptides derived from purified DPPIV and mentioned in Materials and Methods.

The amino acid sequence exhibits high homology with those of other DPPIVs—about 30% identical to human DPPIV (7, 25, 38) and mouse DPPIV (22) and 43% identical to C. meningosepticum DPPIV (17). Serine proteases and serine esterases share a Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly consensus motif found around the active serine (5). This motif occurs in the C-terminal catalytic domain of other DPPIVs (21) with the consensus sequence Gly-Trp-Ser-Tyr-Gly. Three residues, Ser624, Asp702, and His734, are thought to form a catalytic triad in mouse DPPIV (9). The consensus motif around the active Ser and the three amino acids corresponding to the catalytic triad are found in P. gingivalis DPPIV from alignment data. The putative catalytic triad in P. gingivalis DPPIV is Ser593, Asp668, and His700. On the other hand, no significant homology with other bacterial peptidases, such as Lactococcus (23, 30) and Lactobacillus (41) X-Pro dipeptidyl aminopeptidases, was found, except for a few residues around the active Ser and the residues of the catalytic triad, even though the enzymatic activities of the peptidases are the same as those of DPPIV.

Enzymatic properties of recombinant DPPIV.

The amino acid sequence deduced from the dpp gene contains a typical signal sequence in its N terminus. The signal sequence consists of three domains, N, H, and C (34). Lys and Arg residues are found in the N domain, the H domain is composed predominantly of hydrophobic residues, and one Gly residue is found in the H domain. When the (−3, −1) rule of von Heijne (44) is applied to the N-terminal sequence of P. gingivalis DPPIV, the enzyme is predicted to be cleaved between residue 19 (Ala) and residue 20 (Gln) upon secretion, since residue 19 Ala (−1) and residue 17 Ala (−3) are in good agreement with the (−3, −1) rule. We constructed an E. coli strain expressing P. gingivalis DPPIV protein whose second amino acid after the initiation Met is Gln (residue 20 of the enzyme). The dpp gene was located between the codon for the initiation Met and the transcription termination signal of plasmid pTD-T7 (8), so that the gene was under the control of the T7 promoter, resulting in pYKP403. Loop-out mutagenesis was carried out to ligate the codons for the initiation Met and for residue 20 Gln to produce pYKP406. Strain DPPRWT, BL21 carrying pYKP406, was cultured, and the expression of DPPIV protein was induced by IPTG. High-level expression was observed by CBB staining (Fig. 3B) and Western blotting (data not shown). The recombinant protein was purified from the overproducer to near homogeneity (Fig. 3B). From 1 liter of bacterial culture, 7.6 mg of recombinant protein was obtained. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the protein was Met followed by Gln, indicating that the initiation Met was not removed in E. coli. The Km and Vmax values of the recombinant protein were estimated to be 0.21 mM and 23 μmol/min/mg, respectively. The values were almost equal to those of DPPIV purified from P. gingivalis, indicating that DPPIV isolated from P. gingivalis and recombinant DPPIV have almost the same enzymatic properties.

Enzymatic characteristics of P. gingivalis DPPIV.

It was reported that human DPPIV cleaved human CC chemokines (β-chemokines) at the C terminus of the Pro residue on the penultimate position of the N terminus (3, 40). Cleavage of two synthetic peptides, Ser-Pro-Tyr-Ser-Ser-Asp-Thr-Thr (corresponding to the N-terminal amino acids of human RANTES) and Gln-Pro-Asp-Ala-Ile-Asn-Ala-Pro (corresponding to the N-terminal amino acids of human MCP1), by recombinant DPPIV was examined. The recombinant enzyme cleaved the peptides in the same fashion as human DPPIV did, as demonstrated by reverse-phase HPLC with a TSK gel ODS-80Ts column (Tosoh) (data not shown).

As reported previously (16), the present study reconfirmed the ability of human DPPIV to bind to ADA. In contrast, we did not detect the binding of P. gingivalis DPPIV to ADA. After incubation of recombinant DPPIV and ADA, the reaction mixture was loaded onto a 50 mM Tris-HCl nondenaturing gel (pH 8.8). Under these conditions, protein bands of DPPIV and ADA were detected not only by CBB staining but also by Western blotting with anti-P. gingivalis DPPIV antibody and anti-ADA antibody, respectively. However, the band detected by anti-P. gingivalis DPPIV antibody was not stained by anti-ADA antibody. The same result was obtained when the reaction mixture was loaded onto an isoelectric focusing gel (pH 3 to 10). DPPIV purified from wild-type P. gingivalis W83 showed the same results (data not shown). When DPPIV from P. gingivalis was tested on an ADA affinity column, binding of the enzyme to the column was not observed.

Amino acid residues involved in the catalytic activity of P. gingivalis DPPIV.

When P. gingivalis DPPIV was aligned with other DPPIVs, Ser593, Asp668, and His700 were suggested to participate in DPPIV activity. To explore the involvement of these three amino acid residues in catalytic function, we performed in vitro site-directed mutagenesis of P. gingivalis DPPIV. Each of the residues was substituted with Ala to create S593A, D668A, and H700A mutant proteins. The levels of expression of the mutant proteins in strains DPPRSA, DPPRDA, and DPPRHA were almost the same as that of the wild-type protein in strain DPPRWT. The specific activity of wild-type DPPIV was estimated to be 15 μmol/min/mg, while those of the mutant proteins were all less than 2 nmol/min/mg, with 0.4 mM Gly-Pro-pNA as a substrate. Reduction of DPPIV activity of the mutant proteins to less than 1/7,500 wild-type activity suggests that the three amino acid residues are directly involved in the catalytic reaction and that Ser593 is likely to be the catalytic Ser.

Molecular characterization of DPPIV-deficient mutants of P. gingivalis.

To investigate the importance of DPPIV in the virulence of P. gingivalis, we constructed DPPIV-deficient mutants of P. gingivalis W83 as described in Materials and Methods. Two null mutants, 4351 and 4361, were isolated. DPPIV activity was detected in neither of them. The chromosomal DNAs of the two strains were analyzed by PCR with the primer sets primer AL1-primer AL2 and primer AL1-primer AR2 (Fig. 1A). A 463-bp fragment was amplified from both W83 and 4351 chromosomal DNAs with the primer AL1-primer AL2 set. A 2,970-bp fragment and an 885-bp fragment were developed from W83 and 4351 chromosomal DNAs, respectively, with the primer AL1-primer AR2 set.

For Southern hybridization analysis, chromosomal DNAs of W83 and 4351 were digested with PvuII or KpnI. With the AR fragment (Fig. 1A) as a probe, 2.7-kbp PvuII and 6.6-kbp KpnI fragments from W83 DNA hybridized, while 2.4-kbp PvuII and 4.5-kbp KpnI fragments from 4351 DNA hybridized (Fig. 1B). For Western blotting, crude extracts prepared from W83 and 4351 were loaded onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and proteins on the gel were transferred to a membrane. The anti-P. gingivalis DPPIV antibody stained a 78-kDa band from W83 but no band from 4351. Strain 4361 showed the same results in PCR, Southern blotting, and Western blotting as strain 4351. Taken together, these results indicate that 4351 and 4361 are null mutants with most of the dpp gene deleted. Mutant 4351 was chosen for further analysis.

One of the insertion mutants derived from W83, EM23 (Fig. 2), was further analyzed by Southern blotting. Chromosomal DNAs of W83 and EM23 were digested with KpnI or HindIII. With the ermF-ermAM fragment (Fig. 2) as a probe, no hybridized band was seen with W83 DNA; on the contrary, a 7.2-kbp KpnI fragment and 7.6- and 2.5-kbp HindIII fragments from EM23 DNA hybridized (Fig. 2B). With the ALAR fragment (Fig. 1) as a probe, a 6.6-kbp KpnI fragment and an 8.0-kbp HindIII fragment from W83 DNA hybridized, while 7.2- and 1.5-kbp KpnI fragments and 7.6- and 2.5-kbp HindIII fragments from EM23 DNA hybridized (Fig. 2B).

The growth rates of the mutants, 4351, 4361, and EM23, were similar to that of parental strain W83 in BHI broth, indicating that DPPIV is not essential for bacterial growth in rich medium.

Animal experiments.

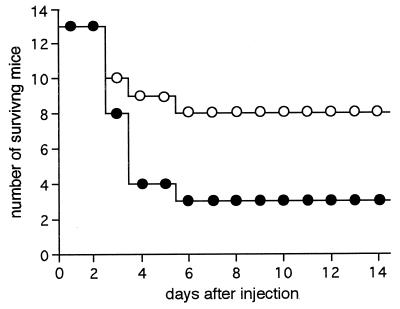

Total cell numbers, as indicated by optical densities of both wild-type W83 and the mutant strains (4351 and EM23), were proportional to viable cell numbers at both the logarithmic and the early stationary phases. In contrast, after the cells reached the stationary phase, the numbers were no longer proportional, presumably because some cells were not viable at this phase. Therefore, we harvested bacterial cells when they were determined by optical density measurements to have reached the early stationary phase. W83 or mutant (4351 or EM23) cells were injected subcutaneously into the dorsal surface of mice. There was no significant decrease in viable cell numbers due to exposure to the atmosphere during the period of injection. Mice displayed ruffled hair within 24 h and began to die 3 days after injection. The numbers of animals dead 6 days after injection of 7 × 109 to 9 × 109 bacterial cells were 13 of 17 with W83, 5 of 13 with 4351, and 1 of 4 with EM23 (Fig. 4 and Table 2). The difference in lethality between W83 and the mutant strains was significant, as determined by Fisher's probability test (P <0.05). There was no significant difference in lethality between the two mutants. All animals that had survived the first 6 days after injection remained alive during the entire observation period of 3 weeks.

FIG. 4.

Number of mice surviving after injection of W83 (●) and dpp-deficient mutant 4351 (○). Data represent the sum of three experiments (experiments 1, 2, and 3 in Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Lesions induced by injection of W83 or dpp-deficient mutants

| Expt (dose/mouse) | Strain | No. of mice/no. tested

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With the following lesions

|

Dead | |||

| Extensivea | Localizedb | |||

| 1 (8 × 109) | W83 | 4/4 | 4/4 | |

| 4351 | 3/4 | 1/4 | 2/4 | |

| 2 (8 × 109) | W83 | 4/4 | 2/4 | |

| 4351 | 1/4 | 2/4 | 1/4 | |

| 3 (9 × 109) | W83 | 4/5c | 4/5 | |

| 4351 | 2/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | |

| 4d (7 × 109) | W83 | 4/4 | 3/4 | |

| EM23 | 4/4 | 1/4 | ||

Covering the abdominal area.

On the abdomen.

One mouse did not develop an extensive lesion but exhibited severe expansion of the abdomen.

The extent of lesion expansion caused by EM23 was much smaller than that caused by W83.

Mice challenged with W83 or mutant strains displayed the following macroscopic findings. (i) Mice exhibited no severe lesions at the sites of injection on the dorsal surfaces, except for redness. (ii) Mice developed abscesses on the abdomens 2 days after injection. Within 1 day of abscess appearance, the abscesses ruptured, and drainage and hemorrhage occurred, resulting in ulcer formation. Sixteen of the 17 W83-challenged animals displayed widespread abscesses or ulcerative lesions covering the abdomens. Among the mutant-challenged animals, 6 of 13 injected with 4351 and 4 of 4 injected with EM23 developed similar extensive lesions on the abdomens. The frequencies of extensive lesions caused by W83 and by mutant strains were significantly different (P < 0.05) (Table 2). (iii) Seven mice injected with 4351 survived throughout the observation period with only localized lesions or with no apparent pathological changes (Table 2). In contrast, one mouse injected with W83 exhibited no abscess on the abdomen but developed severe expansion of the abdomen (Table 2), leading to death in 3 days. Autopsy of this animal revealed that an intestinal protrusion had penetrated through a hole in the peritoneum to reach the subcutaneous region. (iv) Two W83-injected mice and one 4351-challenged animal developed secondary extensive lesions in the thoracic regions within 4 days. (v) Finally, among the surviving animals, one mouse challenged with W83 and three mice challenged with 4351, small ulcerative lesions scattered over several places on the bodies, such as the axillary regions and/or articulations, were found in addition to abscesses on the abdomens.

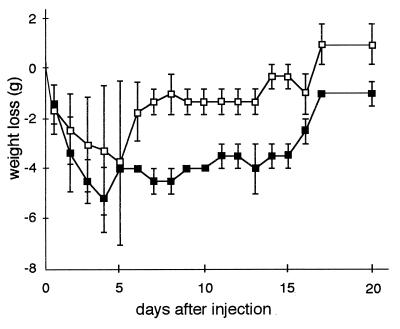

An increase in body weight was observed in 4351-injected mice at 6 days after injection, while it took longer (more than 2 weeks) for the body weight of W83-injected mice to increase in experiment 2 (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained in other experiments shown in Table 2. In concurrence with weight gain, surviving mice showed scarring of ulcerative lesions. Lesions caused by W83 healed much more slowly than those caused by the mutants. The findings indicated that mice challenged with the mutants exhibited faster recovery from the infection than those injected with W83.

FIG. 5.

Average loss of body weight after injection of W83 (■) and dpp-deficient mutant 4351 (□) in experiment 2 of Table 2. Zero grams on the y axis is the average weight of mice just before injection. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

We purified DPPIV from the soluble fraction of P. gingivalis W83 and obtained 19 μg from 1.5 liters of bacterial culture. The amount of protein that we obtained was much higher than that in a previous report (8 μg from 10 liters) in which freezing-thawing had not been carried out (26). P. gingivalis cells could be broken more readily by sonication after freezing-thawing.

The secondary or higher structure of bacterial DPPIV has not been clarified. However, the primary structure of P. gingivalis DPPIV deduced from the DNA sequence revealed high homology with those of eukaryotic DPPIVs, especially in the C-terminal catalytic region. Furthermore, by site-directed mutagenesis, the amino acid residues Ser593, Asp668, and His700 were suggested to participate in catalytic activity. It was suggested that Ser593 is a catalytic Ser residue and that the three residues form a catalytic triad, as previously described for mouse DPPIV (9).

Some enzymatic properties of P. gingivalis DPPIV were similar to those of eukaryotic DPPIVs. First, the enzyme is composed of a homodimer, as proved by gel filtration HPLC. Second, recombinant P. gingivalis DPPIV cleaved peptides that correspond to the N-terminal portion of the CC chemokines RANTES and MCP1, just as human DPPIV did, as demonstrated by reverse-phase HPLC. From the results, P. gingivalis DPPIV is likely to remove dipeptides from some of the CC chemokines, as described for human DPPIV (3, 40). Further investigation is necessary to confirm the cleavage of CC chemokines by P. gingivalis DPPIV.

In contrast to that of human DPPIV, binding of P. gingivalis DPPIV to bovine ADA was not observed by two different experimental methods, gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting and ADA affinity column chromatography. Amino acid residues Leu340, Val341, Ala342, and Arg343 of human DPPIV were identified to be essential for binding to bovine ADA (11). The corresponding amino acids of P. gingivalis DPPIV would be Leu342, Val343, Pro344, and Lys345 when aligned; these residues do not differ greatly from the residues of human DPPIV. Other amino acids which are not conserved in P. gingivalis DPPIV may be required to form the binding domain for bovine ADA. For example, when Glu332-Ser333-Ser334-Gly335-Arg336 in human DPPIV was substituted with Lys-Ile-Asn-Leu-Thr, ADA binding of the mutant human DPPIV decreased significantly (11). Another possible explanation for the difference between P. gingivalis DPPIV and human DPPIV is species specificity of binding to ADA. Bacterial DPPIV may bind to bacterial ADA rather than to eukaryotic ADA. The fact that mouse DPPIV did not bind to bovine ADA (11) supports this supposition.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified DPPIV could not be determined, presumably because the N terminus of the purified protein is blocked. The enzyme seems to be localized on the outside of the cytoplasm, since it possesses a typical signal sequence. Eukaryotic DPPIV has been reported to be localized on membranes such as the T-cell surface (3, 11, 22, 27, 38, 43), both bile canalicular and sinusoidal membranes of hepatocytes (33), and the membrane of the brush border of the small intestine and kidneys (3). P. gingivalis DPPIV is most likely to be localized on the outer membrane, as suggested by the following results. The enzymatic activity of intact whole cells was comparable to that of the sonic extract. Furthermore, DPPIV activity of intact whole cells was reduced to an extent similar to that of the sonic extract after protease treatment (unpublished data). DPPIV activity in the soluble fraction, comprising more than 90% of the total activity, was likely to be derived from the outer membrane. DPPIV may bind loosely to the outer membrane and be released by sonication.

Taken together, the results indicate that P. gingivalis DPPIV and eukaryotic DPPIV share several properties, such as primary structure, catalytic triad, dimer formation, substrate specificity, and localization. The similarity between P. gingivalis DPPIV and eukaryotic DPPIV led us to predict that P. gingivalis DPPIV has significant pathological roles. Eukaryotic DPPIV has been thought to be associated with pathogenesis in several aspects: (i) DPPIV cleaved CC chemokines, and the resulting truncated chemokines exhibited reduced activity as chemoattractants for monocytes and less efficient induction of a Ca2+ response in monocytes (3, 40); (ii) DPPIV removed dipeptide from stromal cell-derived factor 1, and both lymphocyte chemotactic activity and inhibitory activity against human immunodeficiency virus infection disappeared after digestion (3, 31); (iii) DPPIV expressed on the lung endothelial membrane was shown to mediate adhesion and metastasis of breast cancer cells through binding to extracellular matrix proteins (6); (iv) suppression of T cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein occurred through binding of Tat to DPPIV (3, 14, 45); and (v) finally, DPPIV is implicated in the development of diabetes by cleaving glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide 1 (3). We suppose that P. gingivalis DPPIV has similar functions in developing and maintaining periodontitis. P. gingivalis DPPIV may also possess cleaving activity for CC chemokines and stromal cell-derived factor 1, as mentioned above, which reduces the chemotactic activity of monocytes or lymphocytes. This enzyme may also participate in the interaction of P. gingivalis and extracellular matrix proteins.

To investigate whether P. gingivalis DPPIV participates in the virulence of the bacteria, we constructed two types of DPPIV-deficient mutants: null mutants with most of the dpp gene deleted and an insertion mutant. The virulence of wild-type W83 was significantly greater than that of the mutants, as judged by abscess formation, lethality, and recovery from the infection (Fig. 4 and 5 and Table 2). The present results suggest that DPPIV is a virulence factor, although the relationship between the mouse abscess model and periodontitis still remains to be determined. Thus, we are currently carrying out a histopathological study of the lesions and organs obtained from mice that died during the present study, mice that survived until the end of the study, or all mice 3 days after injection.

Banbula et al. (4) have recently reported the purification and DNA sequence of PtpA from P. gingivalis, which cleaves X-Y-Pro from the N termini of peptides. The primary structure of PtpA is highly homologous to that of P. gingivalis DPPIV. The consensus sequence around the active Ser commonly found in DPPIVs, Gly-Trp-Ser-Tyr-Gly, is conserved, and the putative catalytic triad, Ser-Asp-His, is found in PtpA. In addition, some enzymatic properties of DPPIV and PtpA are similar: molecular weight, localization on the cell surface, and possible blockage of the N terminus. PtpA and DPPIV of P. gingivalis may have developed from a common ancestor.

Three additional genes encoding proteases homologous with DPPIV were found in the P. gingivalis genome (4). The possibility that the gene products, if expressed, have enzymatic activity has been suggested (4). However, the proteases are not members of the S9 oligopeptidase family to which DPPIVs belong, since the proteases do not have the consensus sequence around the active Ser of DPPIV. Furthermore, these proteases may not function like DPPIV, at least in rich medium, since measurable DPPIV activity was not detected in the deletion mutants and the insertion mutant in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yasuhiro Watanabe for providing human DPPIV and anti-ADA antibody and Takaaki Aoba for heartfelt understanding.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research 07457071 and 08307004 from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abiko Y, Hayakawa M, Murai S, Takiguchi H. Glycylprolyl dipeptidylaminopeptidase from Bacteroides gingivalis. J Dent Res. 1985;64:106–111. doi: 10.1177/00220345850640020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anna-Arriola S S, Herskowitz I. Isolation and DNA sequence of the STE13 gene encoding dipeptidyl aminopeptidase. Yeast. 1994;10:801–810. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augustyns K, Bal G, Thonus G, Belyaev A, Zhang X M, Bollaert W, Lambeir A M, Durinx C, Goosens F, Haemers A. The unique properties of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (DPPIV/CD26) and the therapeutic potential of DPPIV inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 1999;6:311–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banbula A, Mak P, Bugno M, Silberring J, Dubin A, Nelson D, Travis J, Potempa J. Prolyl tripeptidyl peptidase from Porphyromonas gingivalis. A novel enzyme with possible pathological implications for the development of periodontitis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9246–9252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner S. The molecular evolution of genes and proteins: a tale of two serines. Nature. 1988;334:528–530. doi: 10.1038/334528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng H-C, Abdel-Ghany M, Elble R C, Pauli B U. Lung endothelial dipeptidyl peptidase IV promotes adhesion and metastasis of rat breast cancer cells via tumor cell surface-associated fibronectin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24207–24215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darmoul D, Lacasa M, Baricault L, Marguet D, Sapin C, Trotot P, Barbat A, Trugnan G. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) gene expression in enterocyte-like colon cancer cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4824–4833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Date T, Tanihara K, Numura N. Construction of Escherichia coli vectors for expression and mutagenesis: synthesis of human c-Myc protein that is initiated at a non-AUG codon in exon 1. Gene. 1990;90:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David F, Bernard A-M, Pierres M, Marguet D. Identification of serine 624, aspartic acid 702, and histidine 734 as the catalytic triad residues of mouse dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD26) J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17247–17252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Meester I, Vanhoof G, Lambeir A-M, Scharpé S. Use of immobilized adenosine deaminase (EC 3.5.4.4) for the rapid purification of native human CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV (EC 3.4.14.5) J Immunol Methods. 1996;189:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong R-P, Tachibana K, Hegen M, Munakata Y, Cho D, Schlossman S F, Morimoto C. Determination of adenosine deaminase binding domain on CD26 and its immunoregulatory effect on T cell activation. J Immunol. 1997;159:6070–6076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher H M, Schenkein H A, Morgan R M, Bailey K A, Berry C R, Macrina F L. Virulence of a Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 mutant defective in the prtH gene. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1521–1528. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1521-1528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genco C A, Van Dyke T, Amar S. Animal models for Porphyromonas gingivalis-mediated periodontal disease. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:444–449. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutheil W G, Subramanyam M, Flentke G R, Sanford D G, Munoz E, Huber B T, Bachovchin W W. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Tat binds to dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV (CD26): a possible mechanism for Tat's immunosuppressive activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6594–6598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holt S C, Ebersole J, Felton J, Brunsvold M, Kornman K S. Implantation of Bacteroides gingivalis in nonhuman primates initiates progression of periodontitis. Science. 1988;239:55–57. doi: 10.1126/science.3336774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwaki-Egawa S, Watanabe Y, Kikuya Y, Fujimoto Y. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV from human serum: purification, characterization, and N-terminal amino acid sequence. J Biochem. 1998;124:428–433. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabashima T, Yoshida T, Ito K, Yoshimoto T. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the dipeptidyl peptidase IV gene from Flavobacterium meningosepticum in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;320:123–128. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiyama M, Hayakawa M, Shiroza T, Nakamura S, Takeuchi A, Masamoto Y, Abiko Y. Sequence analysis of the Porphyromonas gingivalis dipeptidyl peptidase IV gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1396:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambeir A-M, Díaz Pereira J F, Chacón P, Vermeulen G, Heremans K, Devreese B, Van Beeumen J, De Meester I, Scharpé S. A prediction of DPP IV/CD26 domain structure from a physico-chemical investigation of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) from human seminal plasma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1340:215–226. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marguet D, Bernard A-M, Vivier I, Darmoul D, Naquet P, Pierres M. cDNA cloning for mouse thymocyte-activating molecule. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2200–2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayo B, Kok J, Venema K, Bockelmann W, Teuber M, Reinke H, Venema G. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:38–44. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.38-44.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misumi Y, Hayashi Y, Arakawa F, Ikehara Y. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV, a serine proteinase on the cell surface. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1131:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90036-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyauchi T, Hayakawa M, Abiko Y. Purification and characterization of glycylprolyl aminopeptidase from Bacteroides gingivalis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989;4:222–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morimoto C, Schlossman S F. The structure and function of CD26 in the T-cell immune response. Immunol Rev. 1998;161:55–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakayama K, Kadowaki T, Okamoto K, Yamamoto K. Construction and characterization of arginine-specific cysteine proteinase (arg-gingipain)-deficient mutants of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23619–23626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakayama K, Yoshimura F, Kadowaki T, Yamamoto K. Involvement of arginine-specific cysteine proteinase (arg-gingipain) in fimbriation of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2818–2824. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2818-2824.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nardi M, Chopin M-C, Chopin A, Cals M-M, Gripon J-C. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of an X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 763. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:45–50. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.45-50.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohtsuki T, Hosono O, Kobayashi H, Munakata Y, Souta A, Shioda T, Morimoto C. Negative regulation of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus and chemotactic activity of human stromal cell-derived factor 1α by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:236–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potempa J, Pavloff N, Travis J. Porphyromonas gingivalis: a protease/gene accounting audit. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:430–434. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piazza G A, Callanan H M, Mowery J, Hixson D C. Evidence for a role of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in fibronectin-mediated interactions of hepatocytes with extracellular matrix. Biochem J. 1989;262:327–334. doi: 10.1042/bj2620327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts C J, Pohlig G, Rothman J H, Stevens T H. Structure, biosynthesis, and localization of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase B, an integral membrane glycoprotein of the yeast vacuole. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1363–1373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schenkein H A, Fletcher H M, Bodnar M, Macrina F L. Increased opsonization of a prtH-defective mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 is caused by reduced degradation of complement-derived opsonins. J Immunol. 1995;154:5331–5337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka T, Camerini D, Seed B, Torimoto Y, Dang N H, Kameoka J, Dahlberg H N, Schlossman S F, Morimoto C. Cloning and functional expression of the T cell activation antigen CD26. J Immunol. 1992;149:481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tokuda M, Karunakaran T, Duncan M, Hamada N, Kuramitsu H. Role of arg-gingipain A in virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1159–1166. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1159-1166.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Coillie E, Proost P, Van Aelst I, Struyf S, Polfliet M, De Meester I, Harvey D J, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Functional comparison of two human monocyte chemotactic protein-2 isoforms, role of the amino-terminal pyroglutamic acid and processing by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12672–12680. doi: 10.1021/bi980497d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vesanto E, Savijoki K, Rantanen T, Steele J L, Palva A. An X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (pepX) gene from Lactobacillus helveticus. Microbiology. 1995;141:3067–3075. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Bonin A, Hühn J, Fleisher B. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV/CD26 on T cells: analysis of an alternative T-cell activation pathway. Immunol Rev. 1998;161:43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Heijne G. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wrenger S, Hoffmann T, Faust J, Mrestani-Klaus C, Brandt W, Neubert K, Kraft M, Olek S, Frank R, Ansorge S, Reinhold D. The N-terminal structure of HIV-1 Tat is required for suppression of CD26-dependent T cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30283–30288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]