Abstract

Objectives

Human monkeypox virus (MPXV) infection is a recently declared public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization. Besides, there is scant literature available on the use of antivirals in MPXV infection. This systematic review compiles all evidence of various antivirals used on their efficacy and safety and summarizes their mechanisms of action.

Methods

A review was done of all original studies mentioning individual patient data on the use of antivirals in patients with MPXV infection.

Results

Of the total 487 non-duplicate studies, 18 studies with 71 individuals were included. Tecovirimat was used in 61 individuals, followed by cidofovir in seven and brincidofovir (BCV) in three individuals. Topical trifluridine was used in four ophthalmic cases in addition to tecovirimat. Of the total, 59 (83.1%) were reported to have complete resolution of symptoms; one was experiencing waxing and waning of symptoms, only one (1.8%) had died, and the others were having a resolution of symptoms. The death was thought unrelated to tecovirimat. Elevated hepatic panels were reported among all individuals treated with BCV (leading to treatment discontinuation) and five treated with tecovirimat.

Conclusion

Tecovirimat is the most used and has proven beneficial in several aggravating cases. No major safety concerns were detected upon its use. Topical trifluridine was used as an adjuvant treatment option along with tecovirimat. BCV and cidofovir were seldom used, with the latter often being used due to the unavailability of tecovirimat. BCV was associated with treatment discontinuation due to adverse events.

Keywords: Antiviral, Monkeypox, Tecovirimat, Brincidofovir, Cidofovir, Treatment

Introduction

The global health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation of public health. Furthermore, as the adverse effects of this pandemic subsided, another public health threat in the form of the Monkeypox virus (MPXV) outbreak stirred nations across the globe. MPXV belongs to the same family as the smallpox virus eradicated in 1980. First reported in 1970, it has historically been largely confined to endemic regions in Western and Central Africa. However, it has spread rapidly throughout the globe in 2022.

Moreover, it has become a public health emergency of international concern, the seventh such declaration ever by the World Health Organization [1]. As of November 6, 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports 78,229 confirmed cases and 41 deaths. These cases are spread across 109 countries, with most (102) countries reporting MPXV cases for the first time ever [2]. MPXV infection could lead to severe disease in certain groups, especially children, the immunocompromised, and pregnant women [3].

MPXV belongs to the orthopoxvirus family. Studies have revealed that poxviruses are generally large, double-stranded DNA-structured viruses, and their genome size lies between 130 to 360 kbp. Due to their large size, they are slow at replicating and surviving in the host body. The orthopoxviruses are surrounded by virulent genes acting as modulators against the host immune system [4]. Some in vitro studies suggest these modulators enable the MPXV to invade the host's immune system. On entering the human host cells, the MPXV replicates in the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal mucosa. Then, the viral load spreads through the lymph nodes and various organs [5].

The common clinical manifestations of MPXV infection can be categorized based on the rapid spread from the site of inoculation to other lymph nodes in different stages of infection. The incubation period lasts for 7-17 days. The prodromal period includes fever, headache, and lymphadenopathy, lasting about 1-4 days. Rashes initially appear over the face and then spread centrifugally to cover other body parts like the palms, soles, and oral cavity. These stay for about 14-28 days [6].

In various studies, supportive treatments and antivirals were used. This review will explore the use of antivirals and their mechanisms against MPXV in clinical settings. Although antivirals and vaccines have been recommended for treatment and prevention, numerous protocols for treating poxvirus are restricted to various at-risk populations, children, pregnant women, or other immunocompromised individuals. Drugs have been selected based on the target range involved in viral replication [7]. Tecovirimat is an antiviral used against poxviruses, and it is the first antiviral drug approved in the United States of America (USA) against orthopoxvirus [8]. In vitro studies also indicate the effective use of cidofovir (CDV) and brincidofovir (BCV) against pox viruses [9].

Depending on how closely related the various orthopoxvirus (including MPXV) are to one another, immune responses to one orthopoxvirus can recognize other orthopoxvirus and produce different degrees of protection. This cross-reactivity is because of shared immune epitopes and a broad extensive response covering at least two dozen structural and membrane proteins. Vaccinations against smallpox and MPXV infection can be administered pre-exposure and post-exposure. [10] Previous smallpox vaccines coincidentally protected against MPXV. Two live-attenuated vaccines for preventing MPXV infection have received US Food and Drug Administration approval: ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS. The former is of replicating type, while the latter is not. Fewer complications have been reported in JYNNEOS, as compared to ACAM2000 [11]. Specifically for MPXV, a vaccine is currently being developed [12].

Insufficient evidence on a particular treatment regimen hinders decision-making in the clinical setting. This ambiguity could be resolved by developing clinical guidelines enabling standardization of care across different sites. Therefore, this study aims to summarize and give a detailed view of the use of antivirals for treating MPXV infection, including the resolution of disease and complications during treatment. It also summarizes their mechanisms of action and clinical pharmacology. This study can throw light on a scenario of uncertainty regarding antiviral therapy in MPXV infection.

Methods

The trial protocol was submitted to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022355596) [13]. The preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement was complied with. The search strategy, criteria for eligibility of studies, and variables of interest were pre-specified in the protocol. The variables of interest were chosen to keep in mind the lack of guidelines for managing human MPXV disease and the subsequently anticipated heterogeneity in managing and reporting the same. The variables of interest are the resolution of the disease and complications during treatment among individuals with MPXV disease receiving antiviral therapy.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Following the protocol, three reviewers (MAS, SDV, CC) independently conducted an extensive literature search. ‘Monkeypox’ was searched along with terms like ‘management,’ ‘treatment,’ ‘antiviral,’ ‘tecovirimat,’ ‘cidofovir,’ and ‘brincidofovir’ in the title or abstract. A comprehensive search was carried out in Ovid-MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and preprint servers for all the articles from the inception of each database through September 9, 2022. The search was repeated on November 1, 2022, to add new articles. For uniformity, the search was limited to studies on humans with MPXV disease. Reference lists were manually reviewed for additional relevant studies. Other details of the search strategy can be referred to in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Given the lack of data on this topic, all original studies on the usage of antivirals in human MPXV infections were included. Clinical trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, and case studies were eligible. Pooled fraction of recovered individuals will be calculated.

Studies performed on animals, in vitro studies, and any study not involving human patients of MPXV infection were excluded. Studies involving related diseases like smallpox were also excluded. If a case was detected to be published more than once, it was reported only once. Studies were excluded where some individuals received antivirals while others did not, and individual patient data was unavailable in the article or the accompanying Supplementary Material. This was done to ensure homogeneity in the review by not combining the data of those who received antivirals with those who did not.

The deduplication of studies was verified by a reviewer (MAS). This was followed by three reviewers (MAS, SDV, CC) independently considering the eligibility of each study based on the title and abstract obtained from the literature search. The full text was screened for the eligible studies, and ineligible studies were further excluded. Disagreements were resolved by mutual consensus. In the absence of consensus, the opinion of a fourth independent reviewer (ST) was considered binding.

Study quality

Because no validated tools are available for assessing the risk of bias in uncontrolled cohort studies or case reports and case series, a previously used and adapted iteration of the Newcastle Ottawa scale was implemented [14], [15], [16]. This tool has a good inter-rater agreement [17]. For uncontrolled studies, items assessing comparability and adjustment were excluded, while those assessing selection, representativeness, and ascertainment were retained. Thus, five questions were finalized, as listed in Table 1 . Studies were qualitatively assessed as good when none of the items gave a negative response, as moderate when one was negative, and poor when more than one was negative.

Table 1.

Assessment of risk of bias of the included studies

| Is the case definition adequate? | Representativeness of the cases | Exclusion of other important diagnoses | Presence of all important data | Ascertainment of outcome | Risk of bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adler et al. [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Rao et al. [36] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Higha |

| Matias et al. [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Ajmera et al. [23] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Desai et al. [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Moschese et al. [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Lucar et al. [28] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Mailhe et al. [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Peters et al. [34] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Shaw et al. [38] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Mbrenga et al. [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Hernandez et al. [27] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Cash-Goldwasser et al. [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Raccagni et al. [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Pastula et al. [33] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Viguier at al. [39] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Hermanussen et al. [26] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Scandale et al. [37] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

This study focused more on the public health response, rather than the management of the individual patient.

Data extraction

Using a standard form, the following data were extracted: antivirals used, dosage, number of individuals in the study, clinical features, resolution of disease, complications during antiviral therapy, and duration of hospitalization after initiation of antiviral therapy. Data were extracted by three independent reviewers (MAS, SDV, CC). Disagreements were solved by consensus. In the absence of consensus, the opinion of a fourth independent reviewer (ST) was considered binding.

Results

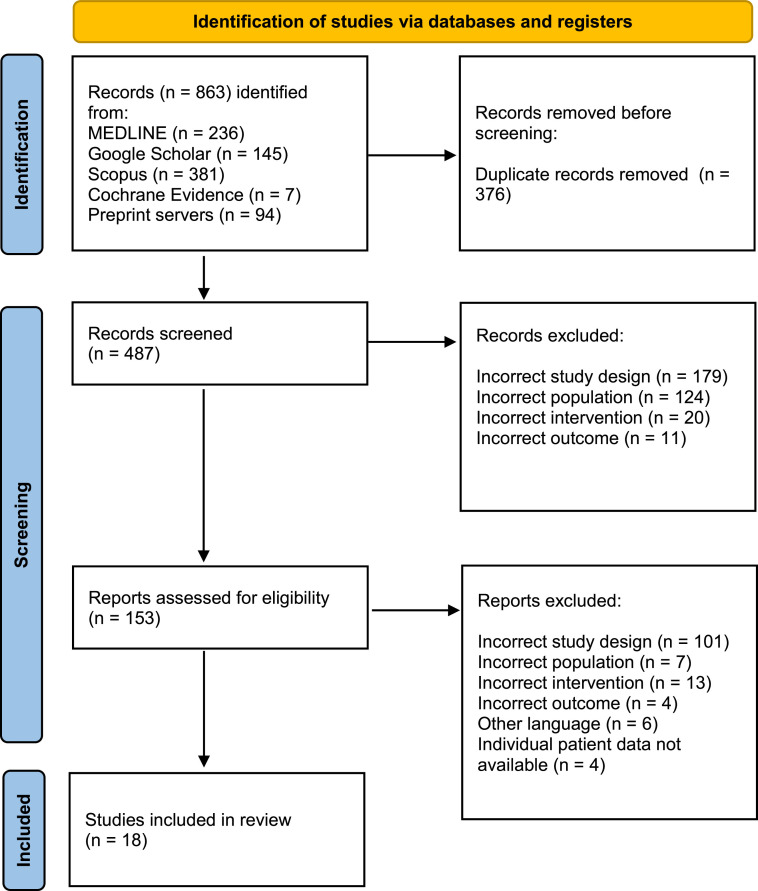

A summary of the complete search process followed by the subsequent selection of studies is shown in Figure 1 . Following a comprehensive literature search, a total of 22 studies that reported the use of antivirals in human individuals with MPXV infection were included. However, four studies were excluded in the final phase as not all the participants had received antivirals, and the authors presented summarized patient data without individual data [18], [19], [20], [21]. Efforts were made by sending an email to them requesting individual patient data for individuals who received antivirals. We have not received the requested information to date, and therefore, we could not include these studies in our review. Table 2 depicts the findings of 18 eligible studies, all of which were uncontrolled studies [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. Thus, a total of 71 individuals have been considered. No published randomized or controlled studies were found on antiviral use for humans with MPXV infection. The heterogeneity of studies led to not all the data being included in all the studies.

Figure 1.

Summary of the search process, screening, and selection of studies

Table 2.

Synthesis of evidence pertaining to usage of antivirals in human monkeypox disease

| Study | Country | Study design | Antiviral | Dosage | Patients | Clinical features (apart from MPXV lesions) | MPXV lesions | Resolution | Complications during treatment | Important details | Duration of hospitalization$ | Age | Sex | Comorbidities & co-infections | Concomitant medications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adler et al. [22] | UK | R | BCV | 200 mg once weekly orally | 3 | Fever, coryzal illness, lypmhadenopathy | Face, scalp, trunk, limbs, palms, glans penis, soles, hands(incuding nail bed), labia majora, penile shaft, legs and scrotum | Resolved | All had elevated transmainase, and course could not be completed; two each had conjuctivitis and lower limb abscess; one had neuropsychiatric issues |

In one patient, all skin lesions and viraemia resolved except ulcerative genital lesions that were PCR positive for monkeypox virus and took longer to resolve | 20, 21, 28 | 30-40 | 2 M, 1 F | Bacterial conjunctivitis | Antibiotics, opioid analgesics, neuropathic analgesics |

| TPOXX | 600 mg twice daily orally | 1 | Malaise, headache, pharyngitis | Face, trunk, arms, and hands | Resolved | - | No new lesions developed after 24 hours; and URT swab PCR came negative 48 hours later |

7 | 30-40 | F | - | - | |||

| Rao et al. [36] | USA | C/R | TPOXX | - | 1 | Fever, GI upset, cough, fatigue | Face | Resolved | - | - | 32 days (date of starting antiviral not known) |

Middle age | M | - | - |

| Matias et al. [30] | USA | C/S | TPOXX | 600 mg twice daily orally | 3 | Fever, malaise, chills, tonsillar pain with odynophagia | Face, oropharynx, hands, feet (including the soles), arm, chest, foreskin of penis and lower eyelid. | Resolved in one; almost completely resolved in the other two till the last date of follow-up mentioned (day 7, 14) | ALT rose to <2 time UNL and resolved without discontinuation of drug in one; loose stool after each dose in another |

- | 2, 5, not mentioned for third | 20-30 *2, 40-50 *1 | M | One had gonococcal urethritis, one had HIV | Prophylactic HIV treatment |

| Ajmera et al. [23] | USA | C/R | TPOXX | 200 mg twice daily orally post discharge | 1 | Sore throat, tongue swelling, burning sensation in mouth, odynophagia, lypmhadenopathy | Mouth, tongue, and face | Resolving at discharge | - | Lesions were aggravating during hospitalization. TPOXX was started on day 3 of hospitalizations, and patient started improving 2 days later |

2 | 26 | M | Syphillis | Tenofovir/emtricitabine for HIV PrEP |

| Desai et al. [25] | USA | u/C | TPOXX | Weight-based, twice or thrice daily orally | 25 | Fever, lymphadenopathy, headache, fatigue, sore throat, chills, backache, myalgia, nausea, and diarrhea | Perianal, genital, chest, eyelid, face, neck, arm, buttocks, back, thigh, wrist, shin, throat, abdomen and forearm. One had all over the body | Resolved in 23 by day 21; only one of the other two developed new lesions |

Fatigue, headache, nausea, itching, and diarrhea | - | Outpatients were evaluated | 26 - 76 (median of 40.7) |

M | Nine had HIV | - |

| Moschese et al. [32] | Italy | C/S | CDV | 5 mg/kg day 1 and 7 | 1 | Fever, chills, sweat, lymphadenopathy | Nose and limb | Resolved | Patient was administered CDV because of unavailability of TPOXX | 7 | 26 | M | Possible bacterial superinfection in nasal lesions | Amoxicillin, Clavulanic acid | |

| Lucar et al. [28] | USA | C/S | TPOXX | 600 mg twice daily orally | 2 | Fever, proctitis, lymphadenopathy, ocular pain and redness, fatigue, rectal bleeding | Mouth, face, limbs, trunk and perianal area | Resolved | Mild transient fatigue in one | Both patients were developing new lesions, and pain required opioids. TPOXX was started on day 9 and 10. Pain improved within 2 days and no new lesions developed. |

One patient was clearly not hospitalized during antiviral therapy, while hospitalization is not mentioned for the other |

26, 37 | M | - | HIV PrEP |

| Mailhe et al. [29] | France | u/C | CDV | 5 mg/kg | 1 | Fever, paronychia, lymphangitis, blepharitis, conjunctivitis, keratitis | Eye | Evolving till the last date of follow-up mentioned | - | - | 7 day(date of starting antiviral not known) | 30 | M | - | Acetaminophen |

| Peters et al. [34] | USA | C/S | TPOXX | - | 1 | Lesions on tongue, fever, fatigue | Tongue | Resolving | - | After testing positive for monkeypox, the patient developed several new lesions involving his arms, legs, and torso. He is still symptomatic but improving with TPOXX. |

- | 38 | M | - | Emtricitabine-tenofovir for the prevention of HIV |

| Shaw et al. [38] | USA | C/R | TPOXX* | 600 mg twice daily orally | 1 | Fever, chills, myalgia, fatigue | Face, back, public region and left foot | Resolving | - | Patient had multiple vesicular lesions, and were positive for both Herpes Simplex Virus-1, and monkeypox Lesions continued to aggravate though fever subsided within 72 hours, and the patient was discharged from the hospital |

3 | 30-40 | M | Hypertension otosyphilis | Pre-exposure (HIV) prophylaxis |

| Mbrenga et al. [31] | Central African Republic | u/C | TPOXX | 600 mg twice daily orally in adults; weight-based |

14 | Muscle pain, headache, lymphadenopathy, fever, back pain, and upper respiratory symptoms | Hands, feet, face, back, thighs, legs, arms, forearms, abdomen and chest | Resolved in 13; one died |

Death in one, and anemia in one; both considered unrelated to TPOXX |

An unusually high 85% comorbidity with malaria was seen | - | 23 (median) | 4 M, 10 F |

Few patients had malaria infection | |

| Hernandez et al. [27] | USA | C/R | TPOXX | 600 mg twice daily orally | 1 | Fever, chills, headaches, sore throat, generalized malaise, and rectal pain and discomfort | Pustules on the trunk, upper and lower extremities, groin, and peri-anal region | Resolved | - | - | - | 37 | M | Metastatic Kaposi sarcoma and hypertension. HIV and secondary syphilis. hypertension. |

Emtricitabine-tenofovir, doravarine, darunavir-cobicistat, and hydrochlorothiazide. |

| Cash-Goldwasser et al. [24] | USA | C/S | TPOXX | - | 5 | Eye pain, itching, redness, swelling, discharge, foreign body sensation, photosensitivity, vision changes, rectal pain | Eye, facial skin, scalp, chest, abdomen, wrist, rectum, penis, vagina | Resolved in four, one is experiencing waxing and waning of symptoms |

- | Four patients were hospitalized, and one experienced marked vision impairment. | 10,5,3 One patient was not admitted One patient is still admitted (day 14) |

20-29 *1, 30-39 *4 | 4 M, 1 F |

Two had HIV disease | Topical povidone iodine, antiretroviral therapy, antibiotics |

| FTD | - | 4# | Eye pain, itching, redness, swelling, discharge, foreign body sensation, photosensitivity, vision changes | Eye, facial skin, scalp, chest, abdomen, wrist, penis, vagina | Resolved in three, one is experiencing waxing and waning of symptoms |

- | All four patients were hospitalized, and one experienced marked vision impairment | 10,5,3 One patient is still admitted (day 14) |

20-29 *1, 30-39 *3 | 3 M, 1 F |

Two had HIV disease | Topical povidone iodine, antiretroviral therapy, antibiotics |

|||

| Raccagni et al. [35] | Italy | C/S | CDV | 5 mg/kg day single dose |

4 | Dyspnea, dysphonia, dysphagia, perianal pain, intrarenal pain, ocular pain, photophobia |

Pharyngo laryngeal, cutaneous, genital, rectal, ocular |

Resolved | - | The second administration of CDV was not required as a positive clinical evolution of MPX lesions was observed among all individuals following the first dose. | 8, 7, 4, 3 | 36, 36, 37, 53 | M | Two of four had HIV disease Crohn's disease in one, chronic gastritis in one |

Antiretroviral therapy, sulfasalazine, testosterone, probenecid |

| Pastula et al. (33) | USA | C/S | TPOXX | - | 2 | Fever, chills, malaise, hemiparesis, paraparesis, urinary retention, bladder and bowel incontinence, priapism, myalgia |

Face | Resolved | - | Both were cases of monkeypox virus-associated encephalitis in presumedly immunocompetent gay man | - | 30-39 | M | Several tests including those for chlamydia, HIV, gonococci, syphillis were negative | Methylprednisolone, IV immunoglobulin, penicillin, plasma exchange, rituximab |

| Viguier at al. [39] | France | C/R | TPOXX | 600 mg twice daily orally | 1 | Fever, asthenia, shivers, watery diarrhea | Face, scalp, trunk, limbs, and anal margins | Resolved | Transient rise in ALT (acme 97 IU/l) and AST activities (acme 86 IU/l) | His clinical condition deteriorated for 37 days, with fever, skin lesions and diarrhea before going to the infectious diseases department, where his severe, protracted infection was treated with TPOXX for 14 day | 14 | 28 | M | HIV, latent syphillis, scalp superinfections with Klebsiella aerogenes and Staphylococcus lugdunensis |

Cotrimoxazole, benzathine benzylpenicillin, antiretroviral therapy |

| Hermanussen et al. [26] | Germany | C/S | TPOXX | 1200 mg daily | 3 | Lymphadenitis, fever, malaise, fatigue |

Penis, anus, face | Resolved in two, Resolving in one |

Transient increase of the γ-glutamyltransferase in 1 | Overall, the antiviral treatment with tecovirima was well-tolerated with no significant side effects. | 7 | 31, 44, 54 | M | Ulcerative colitis, syphillis, HIV positive in 1 |

Vedolizumab, HIV PrEP, penicillin |

| Scandale et al. [37] | Italy | C/R | CDV | 5 mg/kg day single dose |

1 | Ocular pain, photophobia, generalized lymphadenopathy, fever |

Conjunctiva, oropharynx, skin, rectum | Resolved | - | Unilateral ocular involvement with multiple papules at conjunctiva, the fornix, and at the temporal limbus |

- | 35 | M | - | - |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; C/R: case report; C/S: case series; F: female; GI: gastrointestinal; IV: intravenous; M: male; MPX: monkeypox virus; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis; R: retrospective observational; TPOXX: tecovirimat; u/C: uncontrolled cohort; UK: United Kingdom; UNL: upper normal limit; URT: upper respiratory tract; USA: United States of America.

Number of days after initiation of antiviral therapy.

The majority (58, 81.7%) of 71 participants were male. Most individuals (47, 66.2 %) were from the USA. Around 14 (19.7%) individuals were from the Central African Republic, while 10 (14.1%) were from Europe - Italy, the United Kingdom, and France. Of the total included individuals, 59 (83.1%) were reported to have complete resolution of symptoms, one is experiencing waxing and waning of symptoms, only one (1.8%) had died, and the others were having a resolution of symptoms at the study report (Table 2). The death was thought not related to tecovirimat. Elevated hepatic panels were reported among three of three individuals treated with BCV and five of 61 treated with tecovirimat.

Drugs for MPXV infection are still under research. To date, only five drugs have been considered for treatment: tecovirimat, CDV, BCV, trifluridine, and vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) intravenous (IV). VIG has been used in only one individual in a single study [21]. However, individual patient data could not be retrieved, so we have not included this study in our review.

Tecovirimat was the most used drug in these studies. An individual had oral and facial lesions, a burning sensation in the mouth, and dysphagia [23]. The lesions were aggravating while he was initially on vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, dexamethasone, acyclovir, and fluconazole. Later, penicillin was also added. Two days after tecovirimat was started, the individual improved and was subsequently discharged. Two individuals presented with severe proctitis [28], and both had rectal pain, and new lesions were cropping up in the trunk and limbs requiring opioids. On days 9 and 10, respectively, tecovirimat was started for both individuals. In both cases, there was an improvement in pain within 48 hours. An individual had lesions in the tongue, later spreading to the limbs and torso [34]. Tecovirimat was given, and the individual started recovering. An individual had vesicular lesions positive for both herpes simplex virus-1 and MPXV [38]. Tecovirimat was started, and lesions continued to aggravate, but the fever subsided within 72 hours, and the individual was discharged. Two individuals with encephalomyelitis started improving within days of starting tecovirimat and other supportive therapies and were subsequently discharged [33].The clinical condition of an immunocompromised individual living with HIV deteriorated for over a month before starting tecovirimat, and symptoms subsided in 2 days [39]. A case series from Germany describes rapid improvement in two individuals. However, the third individual is slowly recovering [26]. Overall, tecovirimat does indeed seem to help individuals with progressive disease.

Tecovirimat was associated with a few complications, like fatigue, headache, and nausea during treatment. However, one individual developed loose stools a few hours after each dose, while three developed transiently elevated hepatic enzymes that resolved itself [26,30,39]. Treatment did not have to be paused or stopped in any case. The death and anemia seen in one case each were deemed unrelated to tecovirimat [31].

BCV and CDV have been used in one and four studies, respectively. In three studies, individuals receiving CDV recovered [32,35,37]. Another individual presented with severe ocular involvement [29]. Here, two doses of CDV have been administered, and the lesions are evolving as of the last follow-up. None of the four studies reported any adverse events (AEs). As for BCV, all three individuals developed elevated hepatic enzymes (peak alanine transaminase of 127, 331, and 550 U/l, respectively), and the course of medication had to be stopped prematurely. Conjunctivitis, lower limb abscess, and neuropsychiatric symptoms were the other problems encountered [22].

Four individuals with ocular MPXV disease received trifluridine eye drops in addition to tecovirimat therapy. Three of them have recovered, while one has suffered marked vision impairment, and his symptoms were fluctuating. No individual reported any AE [24].

Curating their mechanisms of action, tecovirimat decreases the production of extracellular forms of MPXV by inhibiting the p37 viral proteins needed for cellular localization and formation of the viral envelopment. By inhibiting the envelope on the virus, tecovirimat prevents the systemic spread of the virus by not letting out the virus from the infected cell, thereby preventing subsequent damage to the host cell. For children weighing less than 13 kg, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-held Emergency Access Investigational New Protocol allows opening the capsule to mix the medicine with liquid or soft food. The Strategic National Stockpile offers tecovirimat as an oral capsule formulation (600 mg twice daily for 14 days) or an IV injection. Side effects associated with tecovirimat are usually minimal, such as headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. Injections-site reactions may happen with IV administration. Although there are currently no known contraindications, it should be prescribed or administered with caution in individuals with renal or hepatic impairment [40], [41], [42].

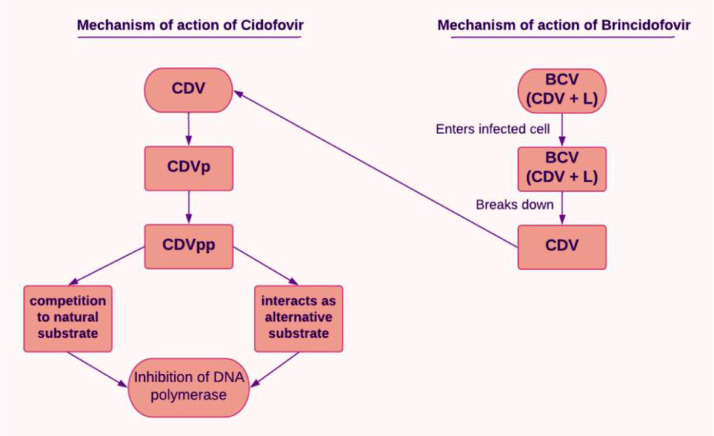

CDV is mainly considered in cytomegalovirus retinitis, a condition commonly seen among the immunosuppressed, including people living with HIV. Cellular enzymes are required to activate CDV once it has entered the cells. CDV is converted to its monophosphoryl form (CDVp), which is then further phosphorylated to CDV diphosphoryl (CDVpp), the active form. These reactions are catalyzed by pyrimidine nucleoside monophosphate kinase and nucleoside 5′-diphosphate kinase, respectively. CDVpp interacts with the viral DNA polymerase, finally getting incorporated into the DNA. CDVpp can behave as a competitive inhibitor. Alternatively, it can substitute the substrate and get incorporated, leading to chain termination [9]. This has been explained diagrammatically in Figure 2 . BCV is a pro-drug and a lipid conjugate of CDV that resembles a natural lipid. Thus, it enters infected cells by taking on the natural lipid absorption mechanisms [43]. Following absorption, the lipid molecule is broken down, thereby releasing CDV for additional intracellular kinase phosphorylation to form CDV diphosphate, the active form of the drug used. Comparing these two drugs, in contrast to CDV, BCV does not act as a substrate for organic anion transporter 1, which makes BCV less harmful to the kidneys. Therefore, compared to CDV, BCV is safer for the kidneys. CDV is less well-tolerated than BCV. BCV is available in oral or suspension form, whereas CDV is in IV form. A dosage of 200 mg weekly for 2 weeks of BCV is recommended in adults weighing ≥48 kg, for adults and children weighing from 10 to 48 kg: 4 mg/kg weekly for 2 weeks are recommended, and for children with body weight below 10 kg, 6 mg/kg is recommended weekly for 2 weeks. The recommended dosage of CDV is 5 mg/kg once weekly for 14 days, followed by 5 mg/kg IV once every other week. Those on BCV may experience minor AEs such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. In contrast, CDV presents side effects such as decreased serum bicarbonate, proteinuria, neutropenia, infection, hypotony of the eye, iritis, uveitis, nephrotoxicity, and fever. BCV is contraindicated in pregnant and lactating women. It may elevate hepatic transaminases and serum bilirubin; therefore, the individual must be assessed for liver function before and after the therapy. In contrast, CDV may harm the kidneys; therefore, dose adjustment must be made in case of renal impairment [42,44].

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of cidofovir

CDV: cidofovir; CDVp: CDV monophosphoryl; CDVpp: CDV diphosphoryl; BCV (CDV + L): Brincidofovir (as CDV conjugated to a lipid molecule).

Regarding trifluridine, there are limited data on managing ocular manifestations of MPXV disease per se [45]. Topical trifluridine eye drops have been approved for other ophthalmological conditions like herpes simplex keratitis and vaccinia. It has also been beneficial against other viruses of the same family in vitro [46,47]. It is being used in MPXV infection also. It is used as a 1% ophthalmic solution. It is administered as a single drop every 2 hours till re-epithelialization occurs. Then, it is administered 4-hourly. Long-term administration exceeding 3 weeks is avoided due to fear of toxicity. It is generally well-tolerated. Transient burning and edema of eyelids are common AEs [48,49].

VIG is prepared from the pooled blood of the recipients of the vaccine for smallpox. The main component is immunoglobulin G (IgG), which is involved in the human body's physiological response to infection. VIG may prevent extracellular orthopoxvirus from infecting its target cells, limiting the ability of viruses to spread from an extracellular to an intracellular location. It is administered IV at 6000 U/kg after symptoms appear. Another dose may be given depending on the clinical profile and treatment response. The dose may be increased to 9000 U/kg in case of lack of response. Headache, nausea, rigors, and dizziness may occur following the administration. It is contraindicated in isolated vaccinia keratitis, a history of anaphylactic response to human globulins, IgA deficiency with antibodies against IgA, and a history of IgA hypersensitivity. No contraindications have been reported for this drug; however, it should be used carefully in individuals with renal insufficiency [42,50].

Discussion

In this first systematic review, we report the antiviral treatment of individuals infected with MPXV. A previous study reviewed the quality of the available guidelines [51]. Many in vitro and animal-model studies are present on this topic, and we included only reported cases/studies of therapy in humans. However, this review aimed to gather the evidence and compile the available information on the usage of antivirals in human individuals with MPXV infection.

Tecovirimat has shown promising results and has been tested earlier on non-human primates [52,53]. It has been conditionally approved for MPXV infection by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency [54]. It has been beneficial in several cases of progressive MPXV infection among the reported cases. It also did not generate any major signal for AEs. Hepatic dysfunction was transient, unlike in the case of BCV, where all three individuals had to discontinue treatment [22]. The solitary case of death among those receiving tecovirimat was also considered unrelated to the drug. CDV is the next most used drug. Of the four studies, it was only used in two because of the unavailability of tecovirimat [29,32]. CDV has been well-tolerated in these studies, which are in line with findings from other studies where IV CDV showed a good tolerability profile when used in different indications [55], [56], [57]. The major concern with its use is nephrotoxicity. However, this was fortunately not seen in any of the individuals. Topical trifluridine has been used as an adjuvant to tecovirimat in some cases with MPXV-associated ocular lesions [24]. Most recovered, and no complications were reported. However, readers should be aware that even in these ocular cases, topical trifluridine has not yet been used as monotherapy.

Given the limited number of individuals in published studies who have received antivirals, there is a need for better-designed studies on the efficacy and safety of antivirals and other drugs in human MPXV disease. The promising results seen with tecovirimat should be investigated further in well-designed research. An exploration of ClinicalTrials.gov and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials shows a few results. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has sponsored two blinded randomized controlled trials comparing tecovirimat to a placebo. These studies are underway (NCT05534984, NCT05559099). PLATINUM-CAN seeks to assess tecovirimat in MPXV infection in Canada and is expected to start recruiting soon (NCT05534165).

The strength of our study is that this is the first systematic review of the management, specifically the pharmacological treatment, of MPXV infection in humans. All the sparsely available information was compiled. However, the study has a few limitations. Only 18 studies could be included and were summarized in this review according to the inclusion criteria. Moreover, all were uncontrolled studies. However, no more eligible studies on the usage of antivirals in individuals with MPXV infection are present. Thus, we could not draw enough conclusions to draft guidelines or recommendations. We faced another limitation in not having individual patient data from a few studies. Important data on the use of tecovirimat and CDV could not be incorporated. We tried our best to use this data, including sending a mail to the concerned authors, but after failing to retrieve this data, we could not include them in our systematic review. Additionally, as anticipated, the data were not amenable to performing a quantitative synthesis and meta-analysis.

This first systematic review on the usage of antivirals in humans with MPXV infection shows that antivirals—tecovirimat, CDV, BCV, trifluridine, and VIG—have been used so far. Among these, tecovirimat was used most often. It demonstrated promising results in individuals with progressive disease and a better safety profile than some other drugs. The data available are limited, and randomized controlled trials can add valuable evidence.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required for this study.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Shailesh Advani (Terasaki Institute of Biomedical Innovation) and Dr. Gitismita Naik (All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani) for their assistance during the development of the protocol of this systematic review. We also thank Dr. Rabbanie Tariq Wani (Directorate of Health Services, Kashmir) for suggesting a few edits in the text.

Author contributions

BKP, MAS, and SDV conceptualized and designed the study. MAS, SDV, CC, ST, PS, CC, and ST were involved in the screening of articles, assessment of the risk of bias, and data extraction. MAS, BKP, VKC, and JAT contributed to the methodology. Software, data analysis, and interpretation were done by AP, PD, AM, AJR, RS, ATA, and JAT. Project administration was done by BKP, RS, and VKC. Resources were provided by BNK, VKC, and RS. The original draft of various sections in the initial phase was contributed by MAS, NA, AP, and BKP. BNK, VKC, and JAT provided critical comments and edited the final draft. Each author had access to all the data in the study and provided inputs to the preparation of the final manuscript. All the authors accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing

All data used in this review were obtained from studies available online. The protocol has been made publicly available at International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, CRD42022355596.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.11.040.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Multi-country outbreak of monkeypox: external situation report, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-monkeypox–external-situation-report–2–25-july-2022; 2022 [accessed 7 November 2022].

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox outbreak global map, https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html; 2022 [accessed 7 November 2022].

- 3.Huang YA, Howard-Jones AR, Durrani S, Wang Z, Williams PCM. Monkeypox: a clinical update for paediatricians. J Paediatr Child Health. 2022;58:1532–1538. doi: 10.1111/jpc.16171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okyay RA, Bayrak E, Kaya E, Şahin AR, Koçyiğit BF, Taşdoğan AM, Avcı A, Sümbül HE. Another epidemic in the shadow of Covid 19 pandemic: a review of monkeypox. EJMO. 2022;6:95–99. doi: 10.14744/ejmo.2022.2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolonen N, Doglio L, Schleich S, Krijnse Locker J. Vaccinia virus DNA replication occurs in endoplasmic reticulum-enclosed cytoplasmic mini-nuclei. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2031–2046. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, Byrareddy SN. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker RO, Bray M, Huggins JW. Potential antiviral therapeutics for smallpox, monkeypox and other Orthopoxvirus infections. Antiviral Res. 2003;57:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaler J, Hussain A, Flores G, Kheiri S, Desrosiers D. Monkeypox: a comprehensive review of transmission, pathogenesis, and manifestation. Cureus. 2022;14:e26531. doi: 10.7759/cureus.26531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrei G, Snoeck R. Cidofovir activity against poxvirus infections. Viruses. 2010;2:2803–2830. doi: 10.3390/v2122803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poland GA, Kennedy RB, Tosh PK. Prevention of monkeypox with vaccines: a rapid review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e349–e358. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelaal A, Reda A, Lashin BI, Katamesh BE, Brakat AM, Al-Manaseer BM, Kaur S, Asija A, Patel NK, Basnyat S, Rabaan AA, Alhumaid S, Albayat H, Aljeldah M, al Shammari BRA, Al-Najjar AH, Al-Jassem AK, AlShurbaji ST, Alshahrani FS.…Sah R. Preventing the next pandemic: is live vaccine efficacious against monkeypox, or is there a need for killed virus and mRNA vaccines? Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10:1419. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10091419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pruc M, Chirico F, Navolokin I, Szarpak L. Monkey pox — a serious threat or not, and what about EMS? Disaster Emerg Med J. 2022;7:136–138. doi: 10.5603/DEMJ.a2022.0022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shamim MA, Veeramachaneni SD, Chatterjee C, Tripathy S. A systematic review of use of antivirals in human monkeypox outbreak: Report No.: PROSPERO 2022 CRD42022355596, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022355596; 2022 [accessed 7 November 2022].

- 14.Bazerbachi F, Leise MD, Watt KD, Murad MH, Prokop LJ, Haffar S. Systematic review of mixed cryoglobulinemia associated with hepatitis E virus infection: association or causation? Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017;5:178–184. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gox021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazerbachi F, Sawas T, Vargas EJ, Prokop LJ, Chari ST, Gleeson FC, Levy MJ, Martin J, Petersen BT, Pearson RK, Topazian MD, Vege SS, Abu Dayyeh BK. Metal stents versus plastic stents for the management of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.08.025. 30–42.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haffar S, Bazerbachi F, Prokop L, Watt KD, Murad MH, Chari ST. Frequency and prognosis of acute pancreatitis associated with fulminant or non-fulminant acute hepatitis A: a systematic review. Pancreatology. 2017;17:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:60–63. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, Martín-Ezquerra G, Fernandez-Gonzalez P, Revelles-Peñas L, Simon-Gozalbo A, Rodríguez-Cuadrado FJ, Castells VG, de la Torre Gomar FJ, Comunión-Artieda A, de Fuertes de Vega L, Blanco JL, Puig S, García-Miñarro ÁM, Fiz Benito E, Muñoz-Santos C, Repiso-Jiménez JB, López Llunell C.…Fuertes I. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765–772. doi: 10.1111/bjd.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Laughlin K, Tobolowsky FA, Elmor R, Overton R, O'Connor SM, Damon IK, Petersen BW, Rao AK, Chatham-Stephens K, Yu P, Yu Y, CDC Monkeypox Tecovirimat Data Abstraction Team Clinical use of tecovirimat (Tpoxx) for treatment of monkeypox under an investigational new drug protocol - United States, May–August 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1190–1195. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7137e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel A, Bilinska J, Tam JCH, da Silva Fontoura D, Mason CY, Daunt A, Snell LB, Murphy J, Potter J, Tuudah C, Sundramoorthi R, Abeywickrema M, Pley C, Naidu V, Nebbia G, Aarons E, Botgros A, Douthwaite ST, van Nispen Tot Pannerden C.…Nori A. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series. BMJ. 2022;378 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, Rockstroh J, Antinori A, Harrison LB, Palich R, Nori A, Reeves I, Habibi MS, Apea V, Boesecke C, Vandekerckhove L, Yakubovsky M, Sendagorta E, Blanco JL, Florence E, Moschese D, Maltez FM.…SHARE-net Clinical Group Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries - April–June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:679–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, Snell LB, Wong W, Houlihan CF, Osborne JC, Rampling T, Beadsworth MB, Duncan CJ, Dunning J, Fletcher TE, Hunter ER, Jacobs M, Khoo SH, Newsholme W, Porter D, Porter RJ, Ratcliffe L, Schmid ML, Semple MG, Tunbridge AJ, Wingfield T, Price NM, NHS England High Consequence Infectious Diseases (Airborne) Network Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajmera KM, Goyal L, Pandit T, Pandit R. Monkeypox - an emerging pandemic. IDCases. 2022;29:e01587. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2022.e01587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cash-Goldwasser S, Labuda SM, McCormick DW, Rao AK, McCollum AM, Petersen BW, Chodosh J, Brown CM, Chan-Colenbrander SY, Dugdale CM, Fischer M, Forrester A, Griffith J, Harold R, Furness BW, Huang V, Kaufman AR, Kitchell E, Lee R.…CDC Monkeypox Clinical Escalations Team Ocular monkeypox - United States, July–September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1343–1347. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7142e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desai AN, Thompson GR, III, Neumeister SM, Arutyunova AM, Trigg K, Cohen SH. Compassionate use of tecovirimat for the treatment of monkeypox infection. JAMA. 2022;328:1348–1350. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.15336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hermanussen L, Grewe I, Tang HT, Nörz D, Bal LC, Pfefferle S, Unger S, Hoffmann C, Berzow D, Kohsar M, Aepfelbacher M, Lohse AW, Addo MM, Lütgehetmann M, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Schmiedel S. Tecovirimat therapy for severe monkeypox infection: longitudinal assessment of viral titers and clinical response pattern-A first case-series experience. J Med Virol. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jmv.28181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez LE, Jadoo A, Kirsner RS. Human monkeypox virus infection in an immunocompromised man: trial with tecovirimat. Lancet. 2022;400:e8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01528-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucar J, Roberts A, Saardi KM, Yee R, Siegel MO, Palmore TN. Monkeypox virus-associated severe proctitis treated with oral tecovirimat: a report of two cases. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1626–1627. doi: 10.7326/L22-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mailhe M, Beaumont AL, Thy M, le Pluart D, Perrineau S, Houhou-Fidouh N, Deconinck L, Bertin C, Ferré VM, Cortier M, de La Porte Des Vaux C, Phung BC, Mollo B, Cresta M, Bouscarat F, Choquet C, Descamps D, Ghosn J, Lescure FX.…Peiffer-Smadja N. Clinical characteristics of ambulatory and hospitalized patients with monkeypox virus infection: an observational cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matias WR, Koshy JM, Nagami EH, Kovac V, Moeng LR, Shenoy ES, Hooper DC, Madoff LC, Barshak MB, Johnson JA, Rowley CF, Julg B, Hohmann EL, Lazarus JE. Tecovirimat for the treatment of human monkeypox: an initial series from Massachusetts, United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac377. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mbrenga F, Nakouné E, Malaka C, Bourner J, Dunning J, Vernet G, Horby P, Olliaro PL. Monkeypox treatment with tecovirimat in the Central African Republic under an Expanded Access Programme. medRxiv. 26 August 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.08.24.22279177. (accessed DD Month 2022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moschese D, Giacomelli A, Beltrami M, Pozza G, Mileto D, Reato S, Zacheo M, Corbellino M, Rizzardini G, Antinori S. Hospitalisation for monkeypox in Milan, Italy. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;49 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pastula DM, Copeland MJ, Hannan MC, Rapaka S, Kitani T, Kleiner E, Showler A, Yuen C, Ferriman EM, House J, O'Brien S, Burakoff A, Gupta B, Money KM, Matthews E, Beckham JD, Chauhan L, Piquet AL, Kumar RN.…O'Connor SM. Two cases of monkeypox-associated encephalomyelitis - Colorado and the District of Columbia, July–August 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1212–1215. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7138e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters SM, Hill NB, Halepas S. Oral manifestations of monkeypox: a report of 2 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;80:1836–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2022.07.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raccagni AR, Candela C, Bruzzesi E, Mileto D, Canetti D, Rizzo A, Castagna A, Nozza S. Real-life use of cidofovir for the treatment of severe monkeypox cases. J Med Virol. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jmv.28218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao AK, Schulte J, Chen TH, Hughes CM, Davidson W, Neff JM, Markarian M, Delea KC, Wada S, Liddell A, Alexander S, Sunshine B, Huang P, Honza HT, Rey A, Monroe B, Doty J, Christensen B, Delaney L, Massey J, Waltenburg M, Schrodt CA, Kuhar D, Satheshkumar PS, Kondas A, Li Y, Wilkins K, Sage KM, Yu Y, Yu P, Feldpausch A, McQuiston J, Damon IK, McCollum AM, July 2021 Monkeypox Response Team Monkeypox in a traveler returning from Nigeria - Dallas, Texas, July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:509–516. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM7114A1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scandale P, Raccagni AR, Nozza S. Unilateral blepharoconjunctivitis due to monkeypox virus infection. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:1274. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw Z, Selvaraj V, Finn A, Lorenz ML, Santos M, Dapaah-Afriyie K. Inpatient management of monkeypox. Brown Hosp Med. 2022;1:1–6. doi: 10.56305/001c.37605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viguier C, de Kermel T, Boumaza X, Benmedjahed NS, Izopet J, Pasquier C, Delobel P, Mansuy JM, Martin-Blondel G. A severe monkeypox infection in a patient with an advanced HIV infection treated with tecovirimat: clinical and virological outcome. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;125:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DrugBank. Tecovirimat, https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB12020; 2020 [accessed 7 November 2022].

- 41.National Center for Biotechnology Information . 2022. PubChem compound summary for CID 56842239.https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/omega-3-Fatty-acids [accessed 7 November 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, Forthal DN, Rizk Y. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs. 2022;82:957–963. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01742-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chimerix. Highlights of prescribing information: TEMBEXA, https://www.chimerix.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/TEMBEXA-USPI-and-PPI-04June2021.pdf; 2021 [accessed 7 November 2022].

- 44.Das D, Hong J. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2019. Herpesvirus polymerase inhibitors. Viral polymerases; pp. 333–356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaufman AR, Chodosh J, Pineda R. Monkeypox virus and ophthalmology-a primer on the 2022 monkeypox outbreak and monkeypox-related ophthalmic disease. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022 doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kern ER. In vitro activity of potential anti-poxvirus agents. Antiviral Res. 2003;57:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu J, Mahendra Raj S. Efficacy of three key antiviral drugs used to treat Orthopoxvirus infections: a systematic review. Glob Biosecur. 2019;1:28. doi: 10.31646/gbio.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milligan AL, Koay SY, Dunning J. Monkeypox as an emerging infectious disease: the ophthalmic implications. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106:1629–1634. doi: 10.1136/bjo-2022-322268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carmine AA, Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Trifluridine: a review of its antiviral activity and therapeutic use in the topical treatment of viral eye infections. Drugs. 1982;23:329–353. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198223050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elsevier . Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2022. Drug monograph: vaccinia immune globulin, VIG.https://elsevier.health/en-US/preview/vaccinia-immune-globulin-vig [accessed 7 November 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webb E, Rigby I, Michelen M, Dagens A, Cheng V, Rojek AM, Dahmash D, Khader S, Gedela K, Norton A, Cevik M, Cai E, Harriss E, Lipworth S, Nartowski R, Groves H, Hart P, Blumberg L, Fletcher T.…Horby PW. Availability, scope and quality of monkeypox clinical management guidelines globally: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berhanu A, Prigge JT, Silvera PM, Honeychurch KM, Hruby DE, Grosenbach DW. Treatment with the smallpox antiviral tecovirimat (ST-246) alone or in combination with ACAM2000 vaccination is effective as a postsymptomatic therapy for monkeypox virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4296–4300. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00208-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russo AT, Berhanu A, Bigger CB, Prigge J, Silvera PM, Grosenbach DW, Hruby D. Co-administration of tecovirimat and ACAM2000TM in non-human primates: effect of tecovirimat treatment on ACAM2000 immunogenicity and efficacy versus lethal monkeypox virus challenge. Vaccine. 2020;38:644–654. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Guidance for tecovirimat use under expanded access investigational new drug protocol during 2022 U.S. Monkeypox cases, https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html; 2022 [accessed 7 November 2022].

- 55.Caruso Brown AE, Cohen MN, Tong S, Braverman RS, Rooney JF, Giller R, Levin MJ. Pharmacokinetics and safety of intravenous cidofovir for life-threatening viral infections in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:3718–3725. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04348-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cesaro S, Zhou X, Manzardo C, Buonfrate D, Cusinato R, Tridello G, Mengoli C, Palù G, Messina C. Cidofovir for cytomegalovirus reactivation in pediatric patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Virol. 2005;34:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Held TK, Biel SS, Nitsche A, Kurth A, Chen S, Gelderblom HR, Siegert W. Treatment of BK virus-associated hemorrhagic cystitis and simultaneous CMV reactivation with cidofovir. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:347–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.