Abstract

Motivational dysfunction constitutes one of the fundamental dimensions of psychopathology cutting across traditional diagnostic boundaries. However, it is unclear whether there is a common neural circuit responsible for motivational dysfunction across neuropsychiatric conditions. To address this issue, the current study combined a meta-analysis on psychiatric neuroimaging studies of reward/loss anticipation and consumption (4308 foci, 438 contrasts, 129 publications) with a lesion network mapping approach (105 lesion cases). Our meta-analysis identified transdiagnostic hypoactivation in the ventral striatum (VS) for clinical/at-risk conditions compared to controls during the anticipation of both reward and loss. Moreover, the VS subserves a key node in a distributed brain network which encompasses heterogeneous lesion locations causing motivation-related symptoms. These findings do not only provide the first meta-analytic evidence of shared neural alternations linked to anticipatory motivation-related deficits, but also shed novel light on the role of VS dysfunction in motivational impairments in terms of both network integration and psychological functions. Particularly, the current findings suggest that motivational dysfunction across neuropsychiatric conditions is rooted in disruptions of a common brain network anchored in the VS, which contributes to motivational salience processing rather than encoding positive incentive values.

Keywords: Motivation, Ventral striatum, Meta-analysis, Lesion network mapping, Monetary incentive delay task

1. Introduction

Organisms survive, develop, and prosper by properly approaching rewards and avoiding potential harm/punishments (Higgins, 1997). To achieve these goals, a sufficient level of motivation for goal-directed actions is necessary (Elliot, 2006). Disrupted reward/loss processing constitutes a vulnerability and a maintenance factor for motivation-related symptoms (e.g., anhedonia and apathy) that are pervasive across various diagnostic categories (Bressan & Crippa, 2005; Husain & Roiser, 2018; B. Zhang et al., 2016). For instance, patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) exhibit a diminished motivation to seek for rewards and they show no response bias toward rewarding stimuli (Eshel & Roiser, 2010). Similar symptoms have been associated with other diagnoses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorder, suggesting a cross-diagnostic nature of these motivation-related symptoms (Strauss, Waltz, & Gold, 2014; Volkow, Fowler, & Wang, 2003; Whitton, Treadway, & Pizzagalli, 2015). These impairments in motivation significantly compromise quality of life, produce poor financial outcomes, and increase burdens for caregivers and society. It is thus imperative to increase our knowledge about abnormal motivational processing across neuropsychiatric conditions and underlying neural signatures with a functional construct approach (Zald & Lahey, 2017).

Motivational processing is not a unitary construct but rather consists of multiple facets, such as anticipatory and consummatory dimensions. Anticipation refers to the expectation of (and preparation for) future rewards and punishments, whereas consumption refers to a state of experiencing rewards or punishments and encoding their motivational salience (Berridge, Robinson, & Aldridge, 2009; Tarantola, Kumaran, Dayan, & De Martino, 2017). These two distinct aspects of motivational processing are well captured by the monetary incentive delay (MID) task and its variants (Diekhof, Kaps, Falkai, & Gruber, 2012; Gu et al., 2019; Oldham et al., 2018; Wilson, et al., 2018), in which a cue indicating the amount of potential reward or loss is followed by a short delay (anticipation phase), then a target is presented that requires a behavioral response; finally, the outcome (consumption phase) is revealed based on participant’s performance (; Knutson, Westdorp, Kaiser, & Hommer, 2000). Combined with brain imaging techniques, the MID paradigm allows for decomposing neural signatures of anticipatory and consummatory aspects of motivation (; Lutz & Widmer, 2014). Specifically, the ventral striatum (VS), insula, amygdala, and thalamus are consistently engaged by the anticipation of both reward and loss (Wilson, et al., 2018), indicating that these regions consist of a general brain circuit encoding motivational salience rather than positive incentive value per se (Oldham et al., 2018). Moreover, the consumption of outcome consistently recruits the VS and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) (Cao, et al., 2019; Diekhof et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2019; Knutson & Greer, 2008; Oldham et al., 2018; Plichta & Scheres, 2014; Wilson, et al., 2018).

The MID task has been extensively employed in a wide range of neuropsychiatric conditions, offering a promising opportunity to uncover potential neural markers of motivation-related deficits that may transcend disorders (Knutson & Heinz, 2015; Ziauddeen & Murray, 2010). In particular, VS hypoactivation during the MID anticipation phase is evident across multiple neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia (Grimm et al., 2014), mood disorders (Knutson, Bhanji, Cooney, Atlas, & Gotlib, 2008), social anxiety (Maresh, Allen, & Coan, 2014), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Ströhle et al., 2008), and alcohol use disorder (Beck et al., 2009). Blunted VS activation is associated with self-reported anhedonia, reductions in anticipatory pleasure, and severity of depressive symptoms (Arrondo et al., 2015; Juckel et al., 2006; Schlagenhauf et al., 2008; Stoy et al., 2012; Stringaris, et al., 2015). Conversely, many studies have revealed comparable striatal responses to the consummatory phase between psychiatric patients and healthy controls (e.g., Bjork, Smith, Chen, & Hommer, 2012; Figee et al., 2011; Hanssen et al., 2015; Murray, Shaw, Forbes, & Hyde, 2017; Ubl et al., 2015; Wotruba et al., 2014). Together, advances in experimental paradigms and brain imaging techniques have provided a more nuanced understanding of dysfunctional motivation processing in neuropsychiatric conditions.

With an increasing body of evidence showing the dysfunctional motivation processing in different disorders, motivation processing deficits have been frequently proposed to constitute a fundamental domain that cut across traditional diagnoses (e.g., Bjork, Knutson, & Hommer, 2008; Cuthbert, 2014a; Cuthbert & Insel, 2013). This transdiagnostic view of the motivational dysfunctions is well in line with a hierarchical model of psychopathology, holding that psychopathological symptoms consist of four levels in an ordered structure: individual symptoms, first-order dimensions (resembling traditional diagnoses), broader second-order factors (e.g., internalizing vs. externalizing) and a general psychopathology factor (i.e., the p-factor) (Lahey, Krueger, Rathouz, Waldman, & Zald, 2017; Zald & Lahey, 2017). In light of this framework, common motivational processing deficits might represent neuropsychological markers of higher-order dimensions that cut across specific diagnoses (Husain & Roiser, 2018; Knutson & Heinz, 2015). Nevertheless, this proposal has been mainly based on narrative reviews, focuses on reward-related (but not loss-related) processing, and largely ignores the heterogeneity of findings in the literature. Therefore, a meta-analytic study is needed to quantitatively synthesize common neural circuit disruptions in motivation (i.e., both reward and loss) processing across diagnoses, while overcoming the heterogeneity and divergence of previous results from limited-size samples (Fox, 2018; Gurevitch, Koricheva, Nakagawa, & Stewart, 2018).

Recent meta-analytic studies on the MID task have examined the neural circuits commonly engaged by anticipatory and consummatory aspects of motivation in healthy populations (Dugre, Dumais, Bitar, & Potvin, 2018; Gu et al., 2019; Oldham et al., 2018; Wilson, et al., 2018). However, to date, there has been no meta-analytic evidence on the common neural signatures underlying motivational processing in different clinical/at-risk conditions, and more specifically, on the common brain function disruptions in anticipatory motivation processing. Beyond the MID task, recent meta-analytic studies have examined reward-processing deficits in specific clinical populations, such as mood disorders (Halahakoon et al., 2020; Keren et al., 2018; W. N. Zhang, Chang, Guo, Zhang, & Wang, 2013) and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Radua et al., 2015). These case-control meta-analyses provide important insights into the aberrant neural reward processing for specific diagnoses, but they cannot uncover the common neural circuit responsible for abnormal motivation processing across disorders. In other words, the widely-used case-control approach reflects the endeavor to map neurobehavioral markers to the first-order dimensions of psychopathology, but it ignores the shared variance among first-level dimensions and thus impedes investigations of transdiagnostic mechanisms of psychopathology (Li et al., 2020; Zald & Lahey, 2017).

A transdiagnostic meta-analysis of psychiatric neuroimaging studies is well-suited to address this issue by synthesizing neural underpinnings nonspecifically associated with multiple forms of psychopathology. That is, the transdiagnostic approach aims at the shared variance among first-level dimensions and thus investigates higher-order dimensions of psychopathology (see also Zald & Lahey, 2017). Notably, more and more evidence has indicated that mappings between psychopathology and neurobehavioral systems might be more robust at the higher-order factors than at lower first-order dimensions (Kaczkurkin et al., 2018; Kaczkurkin et al., 2019; Katharina, White, Tseng, Jillian, & Wiggins, 2018; Neumann et al., 2020; Romer et al., 2018; Shanmugan et al., 2016; Snyder, Hankin, Sandman, Head, & Davis, 2017; Weissman et al., 2019). For instance, a wide array of psychiatric disorders broadly share a large portion of their common genetic variation (Brainstorm et al., 2018), suggesting that higher-order factors account for a larger proportion of heritable variance than first-order dimensions (Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman, & Rathouz, 2011). These findings highlight the importance of identifying neurobiological systems linked to overarching dimensions of psychopathology that cut across diagnoses. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on the MID task across categorical diagnoses to search for transdiagnostic brain dysfunctions in motivational processing, leveraging abundant evidence from brain imaging studies of the MID task in the past decades as well as the distinction between reward-related and loss-related processing and that between anticipatory and consummatory aspects of motivation in the MID paradigm.

Notably, the current transdiagnostic meta-analysis was complemented with a novel and validated technique termed lesion network mapping (Boes et al., 2015; Darby, Horn, Cushman, & Fox, 2018; Darby, Joutsa, Burke, & Fox, 2018) to examine potential networks encompassing lesion locations causing motivation-relevant functional deficits (e.g., anhedonia and apathy). This novel approach maps lesion-induced symptoms to brain networks rather than specific regions by combining lesion locations with maps of resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) derived from normal nonsymptomatic populations (Boes et al., 2015; Darby, Laganiere, Pascual-Leone, Prasad, & Fox, 2017; Ferguson et al., 2019). Specifically, the lesion network mapping consists of the following steps: (i) the volume of each lesion is reproduced onto a reference brain; (ii) the network of brain areas functionally connected to each lesion location is assessed with RSFC; and (iii) the networks associated with each lesion are thresholded and overlaid to determine common network sites across the lesions. Lesion network mapping is well-suited to examine the neurobiological basis of complex symptoms embedded in a distributed brain network consisting of heterogeneous regions (Fox, 2018). In our case, lesion network mapping can provide complementary evidence for the meta-analysis by revealing whether brain networks causally linked to motivational deficits (e.g., anhedonia and apathy) overlap with brain areas ensuing from reward/loss processing deficits across neuropsychiatric conditions. Despite of recent narrative reviews linking different lesion locations to motivational impairments (e.g., Husain & Roiser, 2018; Le Heron, Holroyd, Salamone, & Husain, 2019), to our knowledge, no study has so far quantitatively examined convergence across lesion locations causing apathy or anhedonia in terms of their functional connectivity profiles. Such a network approach is particularly relevant to identify neurobiological systems causally linking to motivational functioning as a complex and multidimensional construct. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly acknowledged that human motivation-related processing can be better understood in terms of interactions across large-scale brain networks comprising of distributed brain locations rather than in terms of specific structures (see also Husain & Roiser, 2018). Together, the current study aimed to identify transdiagnostic neural circuit disruptions in motivational processing across neuropsychiatric conditions and to provide data-driven quantitative inference on the functions of identified nodes from the perspective of system neuroscience with the lesion network mapping approach.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Literature search and selection

A systematic online database search was performed in accordance with the PRISMA-guidelines (Shamseer, et al., 2015) and best practice recommendations for neuroimaging meta-analysis (Müller et al., 2017; Tahmasian et al., 2019). The search was finished in April 2022 and included the PubMed and ISI Web of Science databases using the combination of relevant search terms (i.e., [“monetary incentive delay” OR “MID task” OR “anticipation of reward” OR “reward anticipation” OR “social incentive delay” OR “SID task” OR “incentive delay task”] AND [“functional magnetic resonance imaging” OR “fMRI” OR “positron emission tomography” OR “PET”]). Moreover, we explored several other sources, including: (i) the BrainMap database (http://brainmap.org); (ii) the bibliography and citation indices of the preselected articles; (iii) the reference list of relevant reviews (Balodis et al., 2012; Grimm, Kaiser, Plichta, & Tobler, 2017; Haber & Knutson, 2010; Knutson & Cooper, 2005; Knutson & Heinz, 2015; Oldham et al., 2018; Plichta & Scheres, 2014); and (iv) direct searches of the names of frequently occurring authors. The identified articles were further assessed according to the following criteria. First, subjects performed a MID task or its variants (Knutson, Adams, Fong, & Hommer, 2001; Knutson, Fong, Adams, Varner, & Hommer, 2001). Second, we restricted the meta-analysis to studies that employed the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) imaging modality. Third, results from whole-brain general-linear-model-based analyses (rather than region of interest [ROI] analyses) were provided, given that the activation likelihood estimation (ALE) approach assumes that each voxel has a priori the same chance of being activated (Müller et al., 2018). Fourth, each study referred to at least one comparison between a neuropsychiatric/at-risk group versus a control group using functional brain imaging data. Finally, activations were presented in standardized stereotaxic space (Talairach or Montreal Neurological Institute, MNI). Note that for publications reporting Talairach coordinates, a conversion to MNI coordinates was employed with an icbm2tal algorithm (Lancaster et al., 2007). Filtering the search results according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria yielded a total of 129 published fMRI or PET articles (Table S1).

2.2. Main ALE approach

A coordinate-based meta-analysis of selected neuroimaging studies was conducted, employing the ALE algorithm (in-house MATLAB scripts) (Eickhoff et al., 2009; Eickhoff, Laird, Fox, Lancaster, & Fox, 2017). The ALE algorithm determines the convergence of foci reported from different functional (e.g., blood-oxygen-level dependent contrast imaging) or structural (e.g., voxel-based morphometry) neuroimaging studies with published foci in either Talairach or MNI space (Laird et al., 2005; Turkeltaub, Eden, Jones, & Zeffiro, 2002). The ALE algorithm interprets reported foci as spatial probability distributions, whose widths are based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty due to between-subject and between-template variability of the neuroimaging data (Eickhoff et al., 2009). The ALE algorithm weights between-subject variability based on the number of subjects analyzed, modeling larger sample sizes with smaller Gaussian distributions and, thus, presupposing more reliable approximations of the “true” activation observed in larger sample sizes (Eickhoff et al., 2009).

The union of the individual modulated activation maps, first created from the maximum probability associated with any one focus (always the closest one) for each voxel (Turkeltaub et al., 2012), was then calculated to obtain an ALE map across studies. This ALE map was assessed against a null-distribution of random spatial associations between studies using a non-linear histogram integration algorithm (Eickhoff, Bzdok, Laird, Kurth, & Fox, 2012; Turkeltaub et al., 2012). Furthermore, the average non-linear contribution of each experiment for each cluster was calculated from the fraction of the ALE values at the cluster with and without the corresponding experiment (Eickhoff et al., 2016). Based on the calculated contribution, we employed two additional criteria to select significant clusters: (i) the contributions to one cluster were from at least two experiments to prevent findings from being driven by the results from a single experiment; and (ii) the average contribution of the most dominant experiment (MDE) did not exceed 50%, and the average contribution of the two most dominant experiments (2MDE) did not exceed 80% (Eickhoff et al., 2016).

Applying the ALE algorithm, the reported coordinates of brain areas associated with reward/loss anticipation or consumption converged across different experiments. Neural signatures of reward/loss processing converged using the following meta-analytic schemes: (i) reward anticipation in healthy controls (101 experiments, 1415 foci, and 2421 subjects) or clinical/at-risk conditions (37 experiments, 371 foci, and 911 subjects); (ii) hypoactivity (40 experiments, 277 foci, and 1748 subjects) or hyperactivity (25 experiments, 191 foci, and 1565 subjects) of reward anticipation in clinical/at-risk conditions compared to healthy controls; (iii) loss anticipation in healthy controls (52 experiments, 514 foci, and 1309 subjects) or clinical/at-risk conditions (26 experiments, 219 foci, and 688 subjects); (iv) hypoactivity (18 experiments, 74 foci, and 697 subjects) of loss anticipation in clinical/at-risk conditions compared to healthy controls; (v) reward consumption in healthy controls (44 experiments, 454 foci, and 1122 subjects) or clinical/at-risk conditions (21 experiments, 210 foci, and 636 subjects); and (vi) hypoactivity (15 experiments, 106 foci, and 504 subjects) or hyperactivity (17 experiments, 209 foci, and 970 subjects) of reward consumption in clinical/at-risk conditions compared to healthy controls. It should be noted that meta-analyses were not conducted for hyperactivity of loss anticipation (11 experiments, 71 foci, and 530 subjects) or contrasts associated with loss outcome (healthy controls: 15 experiments, 101 foci, and 445 subjects; clinical/at-risk conditions: 9 experiments, 47 foci, and 385 subjects; hypoactivity: 4 experiments, 24 foci, and 164 subjects; hyperactivity: 3 experiments, 25 foci, and 160 subjects) due to the limited number of experiments (see also Müller et al., 2018) (Table S1–S5).

All maps were thresholded using a cluster-level family-wise error correction (P < 0.05) with a cluster-forming threshold of P < 0.001 using 10,000 permutations for correcting multiple comparisons.

2.3. Conjunction analyses

To further examine the overlaps or correspondence between different processes and conditions, conjunction analyses were implemented for the following pairs of contrasts: (i) reward anticipation among healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions; (ii) loss anticipation among healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions; (iii) reward consumption among healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions; and (iv) hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to the controls for reward and loss anticipation. The conjunction analyses were implemented by identifying the intersection between two corrected ALE results.

2.4. Modulation effects

For the clusters identified in contrasts involving direct comparisons between healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions (i.e., hypoactivation in the reward or loss anticipation and hyperactivation in the reward consumption), per-voxel probabilities were extracted to investigate potential modulating effects of demographic, clinical, and imaging-specific factors, including mean age, sex ratio, medication status, neuropsychiatric condition, comorbidity, and MRI magnetic field strength (see also Goodkind et al., 2015; Jenkins et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020). Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis H, Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, and Spearman’s rank correlation tests were utilized as warranted. However, it should be noted that we did not assess modulating effects of some potentially influential factors (e.g., IQ, duration of disease) that were not reported in most studies.

2.5. Lesion network analysis

2.5.1. Case selection

Case reports of lesion-induced apathy or anhedonia were identified from PubMed and ISI Web of Science databases using the combination of relevant search terms (“apathy” OR “anhedonia” OR “avolition” OR “abulia” OR “akinetic mutism”) AND (“MRI” OR “CT” OR “neuroimaging”) AND (“damage” OR “stroke” OR “hemorrhage” OR “tumor” OR “lesion”) in April 2022. The search resulted in 618 articles, and the abstract or full text was read from 382 publications which were considered to be relevant according to their titles. These publications were subjected to additional inclusion/exclusion criteria in light of previous studies (Boes et al., 2015; Darby et al., 2017; Fasano, Laganiere, Lam, & Fox, 2017; Fisher, Towler, & Eimer, 2016; Joutsa, Horn, Hsu, & Fox, 2018; Laganiere, Boes, & Fox, 2016). The inclusion criteria were: (i) case description of motivational deficits in a patient; (ii) neurological examination documenting apathy or anhedonia symptoms presumed to be caused by an intraparenchymal brain lesion; and (iii) clearly delineated and circumscribed brain lesions displayed to be transcribed onto a standard brain template. The exclusion criteria were: (i) extrinsic compression injuries without a clearly represented intraparenchymal lesion; (ii) poor image resolution such that lesion boundaries could not be delineated; (iii) significant mass effects. Filtering the searched articles according to the above inclusion/exclusion criteria yielded a total of 105 cases from 67 published articles (Table S18).

2.5.2. Lesions

Lesion locations from originally published figures were manually traced onto a standard template brain as described previously (Boes et al., 2015; Darby et al., 2017; Fasano et al., 2017; Fischer et al., 2016; Joutsa et al., 2018; Laganiere et al., 2016). Neuroanatomical landmarks were used to ensure accurate transfer onto the template. Specifically, lesions were mapped by hand onto the MNI152 T1 template with 2 mm isotropic voxels using FSL (Jenkinson, Beckmann, Behrens, Woolrich, & Smith, 2012) to make binary lesion masks (value 1 for voxels included to the lesions and value 0 for other voxels). It should be noted that when utilizing this methodology, it was unrealistic to capture the whole 3D lesion volume but only representative 2D slices. However, earlier works suggest that 2D slices can fill in equitable approximation of 3D lesions for lesion network mapping (Boes et al., 2015; Darby et al., 2017). In cases where multiple lesions were displayed, all lesions were mapped together and treated as a single lesion for ensuing analyses (Fasano et al., 2017; Laganiere et al., 2016).

2.5.3. Lesion network mapping

Lesion network mapping was used to investigate the networks associated with apathy or anhedonia. The analysis steps of this technique have been described in the Introduction (see also Boes et al., 2015; Corp et al., 2019; Darby et al., 2017; Darby, Horn, et al., 2018; Fischer et al., 2016; Laganiere et al., 2016).

2.5.4. Specificity

To access the specificity of lesion brain mapping results, we implemented two control analyses. First, we conducted the same analysis with 105 random lesions to assure that the results were specific to apathy and/or anhedonia rather than reflecting a collection of similarly sized but randomly distributed lesions. Specifically, ten separate randomized control groups were generated through ten repetitions of the lesion randomization process, each with 105 randomized lesions, thus resulting in a total of 1050 randomized lesions. When conducting this randomized method, we controlled for the degree of lesion overlap as well as interlesion distances (see also Boes et al., 2015; Laganiere et al., 2016). Second, we adopted lesions causing an assortment of different neurological symptoms from a previous study (Boes et al., 2015) as control samples, including peduncular hallucinosis, auditory hallucinosis, central post-stroke pain, and subcortical expressive aphasia.

3. Results

3.1. Studies included in meta-analyses

Our meta-analyses included 129 PET/fMRI studies that recruited healthy controls and/or different clinical/at-risk conditions. In particular, the following clinical/at-risk conditions were included in the current meta-analysis (see also Table 1): (1) addiction-related conditions, including alcohol-dependence, cannabis users, cocaine-dependence, nicotine smokers, and pathological gambling (68 experiments); (2) mood/anxiety-related conditions, including anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, early life stress, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and rumination symptoms (50 experiments); (3) neurodevelopmental conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder (37 experiments); (4) psychosis-related conditions, including schizophrenia, subclinical psychotic experiences, and high risk for psychosis (25 experiments); (5) personality-related conditions, including borderline personality, external disorder (mainly oppositional defiant disorder), and high sociodemographic risk for antisocial behaviors (9 experiments); (6) eating disorder conditions, including binge eating disorder and obesity (4 experiments); and (7) other conditions, including body focused repetitive behaviors, Huntington’s disease, and impulsivity traits (6 experiments).

Table 1.

A summary of clinical/at-risk conditions included in meta-analyses.

| Clinical/at-risk conditions | Reward Anticipation |

Reward Anticipation |

Reward Anticipation |

Reward Consumption |

Reward Consumption |

Reward Consumption |

Loss Anticipation |

Loss Anticipation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | HC vs NC | NC vs HC | NC | HC vs NC | NC vs HC | NC | HC vs NC | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Addicction-related | Alcohol-dependence | 8 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| Cannabis users | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Cocaine-dependence | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Nicotine smokers | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Pathological gambling | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Mood/Anxiety-related | Anxiety disorders | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Early life stress | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Major depressive disorder | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Rumination symptoms | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Neurodevelopmental disorders | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Psychosis | High risk for psychosis | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Schizophrenia | 4 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| subclinical psychotic | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| experiences | |||||||||

| Personality-related | Borderline personality disorder | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| External disorder (mainly oppositional defiant disorder) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| High sociodemographic risk for antisocial behaviors | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Eating disorders | Binge eating disorder | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Obesity | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Others | Body focused repetitive behaviors | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Huntington’s disease | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Impulsivity traits | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

HC – healthy controls, NC - Neuropsychiatric conditions.

3.2. Main ALE meta-analyses

3.2.1. Reward anticipation

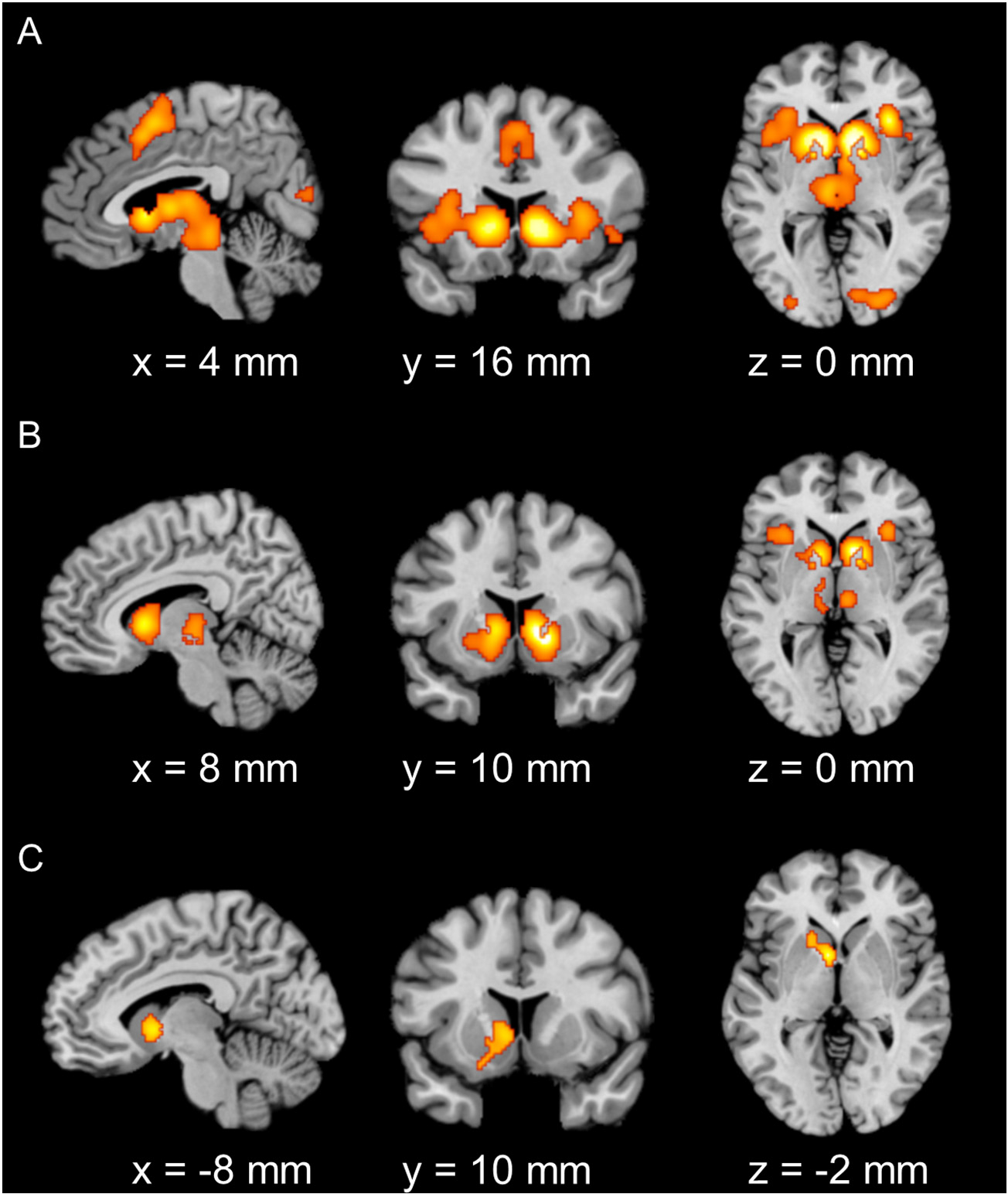

In healthy controls, consistent maxima were identified in the bilateral VS (extending to the amygdala, thalamus, and anterior insula [AI]), supplementary motor area (SMA), precentral gyrus, middle occipital gyrus, and right calcarine (Fig. 1A). In clinical/at-risk conditions, consistent maxima were found in the bilateral VS, AI, and left precentral gyrus (Fig. 1B). Examining the contrasts of hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls demonstrated consistent maxima in the left VS (Fig. 1C). No significant consistent maxima were identified for the contrasts of hyperactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls. More details on the contribution of each study in each identified brain region are illustrated in Table S6–S9. The main findings described above have been validated using the leave-one-experiment-out (LOEO) scheme (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Significant clusters from the main meta-analysis of reward anticipation in (A) healthy controls, (B) clinical/at-risk conditions and (C) hypoactivation of clinical/at-risk conditions relative to healthy controls (cluster-level family-wise error correction, P < 0.05, with a cluster-forming threshold of P < 0.001 using 10,000 permutations). (A). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS (extending to the amygdala, thalamus, and AI), SMA, precentral gyrus, middle occipital gyrus, and right calcarine were identified for healthy controls. (B). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS and AI were identified for clinical/at-risk conditions. (C). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS were found for hypoactivation of clinical/at-risk conditions relative to healthy controls.

Moreover, for the left VS identified in the contrasts of hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls, modulation analyses revealed no significant modulating effects of clinical, demographic, or imaging-specific factors (P > 0.05 for all).

3.2.2. Loss anticipation

In healthy controls, consistent maxima were identified in the bilateral VS (extending to the amygdala, thalamus, and AI), SMA and left middle occipital gyrus (Fig. 2A). In clinical/at-risk conditions, consistent maxima were found in the bilateral VS, thalamus, SMA, precentral gyrus, and left AI (Fig. 2B). Examining the contrasts of hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls demonstrated consistent maxima in the left VS, middle occipital gyrus, and cuneus (Fig. 2C). Details on the contribution of each study in each identified brain region are included in Table S10–S13. The main findings described above have been validated using the LOEO scheme (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Significant clusters from the main meta-analysis of loss anticipation in (A) healthy controls, (B) clinical/at-risk conditions, and (C) hypoactivation of clinical/at-risk conditions relative to healthy controls (cluster-level family-wise error correction, P < 0.05, with a cluster-forming threshold of P < 0.001 using 10,000 permutations). (A). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS (extending to the amygdala, thalamus, and AI) and SMA were identified for healthy controls. (B). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS, AI, SMA, thalamus, and precentral gyrus were identified for clinical/at-risk conditions. (C). Consistent maxima in the left VS, middle occipital gyrus, and cuneus were found for hypoactivation of clinical/at-risk conditions relative to healthy controls during loss anticipation.

Moreover, for the left VS, middle occipital gyrus, and cuneus identified in the contrasts of hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls, modulation analyses revealed no significant modulating effects of clinical, demographic, or imaging-specific factors (P > 0.05 for all).

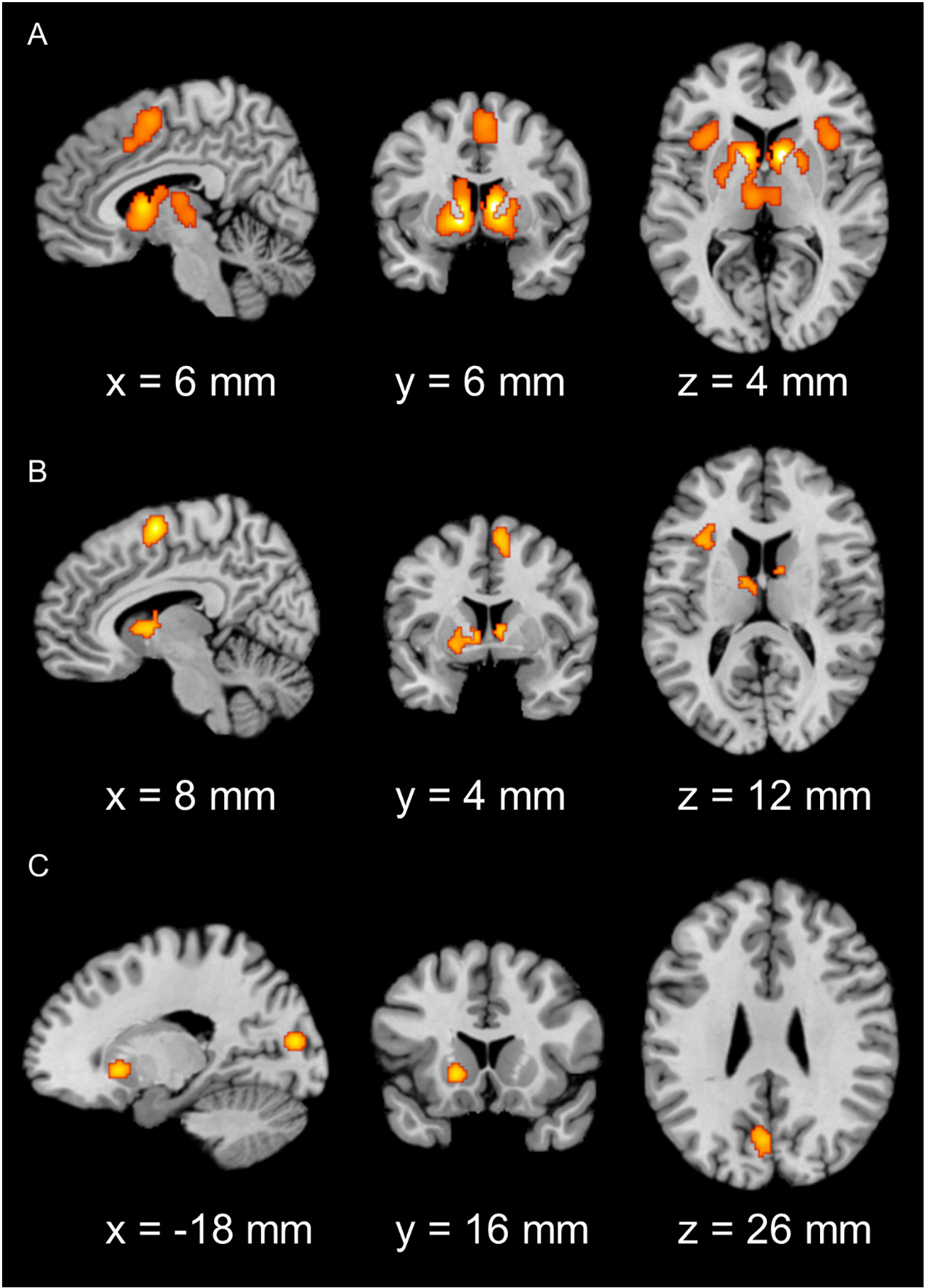

3.2.3. Reward consumption

In healthy controls, consistent maxima were identified in the bilateral VS, vmPFC, and posterior cingulate cortex (Fig. 3A). In clinical/at-risk conditions, consistent maxima were found in the bilateral VS and vmPFC (Fig. 3B). No significant consistent maxima were identified for the contrasts of hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to healthy controls. Examining the contrasts of hyperactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls demonstrated consistent maxima in the left inferior parietal lobule (IPL) (Fig. 3C). Details on the contribution of each study in each identified brain region are included in Table S14–S17. The main findings described above, except the hyperaction in the IPL, have been validated using the LOEO scheme (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S3).

Fig. 3. Significant clusters from the main meta-analysis of reward consumption in (A) healthy controls, (B) clinical/at-risk conditions, and (C) hyperactivation of clinical/at-risk conditions relative to healthy controls (cluster-level family-wise error correction, P < 0.05, with a cluster-forming threshold of P < 0.001 using 10,000 permutations).

(A). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS, vmPFC, and PCC were identified for healthy controls. (B). Consistent maxima in the vmPFC and right VS were identified for clinical/at-risk conditions. (C). Consistent maxima in the left IPL were found for hyperactivation of clinical/at-risk conditions relative to healthy controls during reward consumption.

Moreover, for the left IPL identified in the contrasts of hyperactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls, modulation analyses revealed a significant effect of sex ratio in the clinical/at-risk conditions (P < 0.05, uncorrected), but modulating effects of other clinical, demographic, or imaging-specific factors were not significant (P > 0.05 for all).

In summary, our main ALE meta-analyses revealed that anticipations of both reward and loss engage the involvement of the VS, AI, and SMA in both healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions. These findings are in line with recent meta-analytic findings in the healthy populations (e.g., Dugre et al., 2018; Gu et al., 2019; Oldham et al., 2018; Wilson, et al., 2018) but further provide novel evidence in the clinical/at-risk conditions. More importantly, our results provided the first meta-analytic evidence on the transdiagnostic hypoactivation of the left VS in response to both reward and loss anticipation. Regarding the reward consumption, our results revealed that reward outcome activates the vmPFC and VS among both healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions. Finally, clinical/at-risk conditions (vs. healthy controls) exhibited common hyperactivation of the IPL in response to reward outcome.

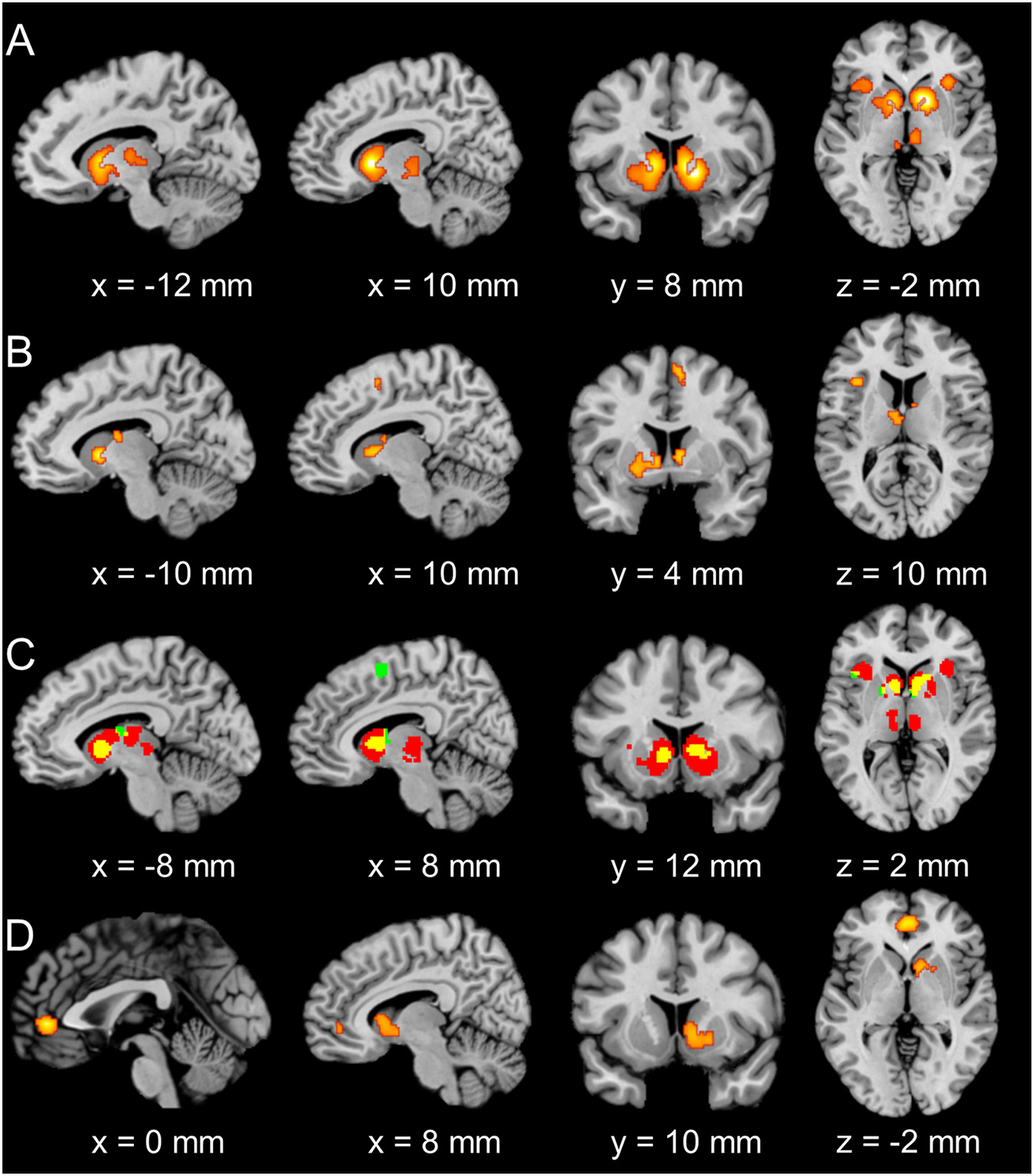

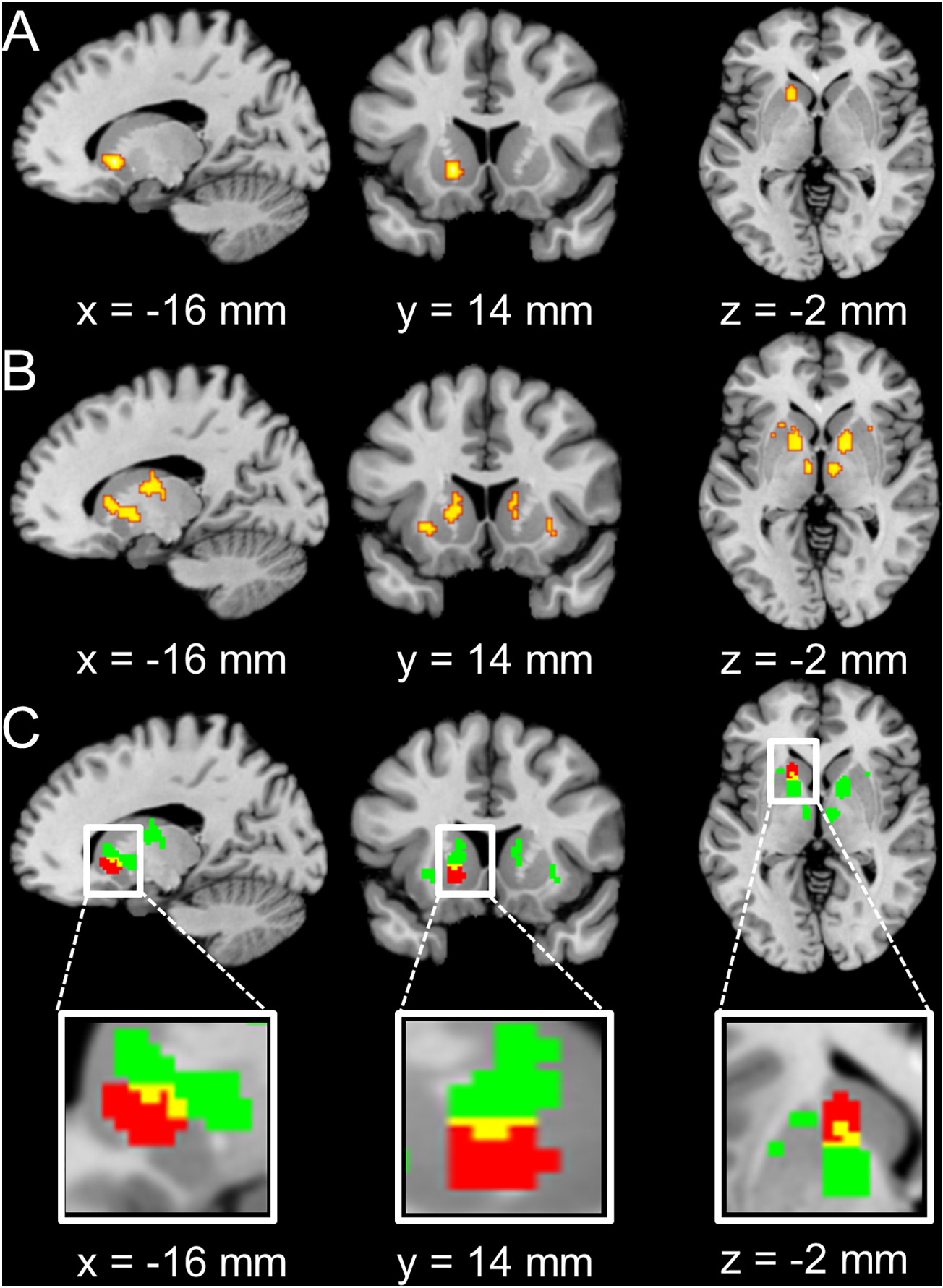

3.3. Conjunction findings

The conjunction analysis revealed common activation maxima in the bilateral VS, AI, and left precentral gyrus for reward anticipation among healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions (Fig. 4A). The conjunction analysis of loss anticipation between healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions revealed overlaps in the bilateral VS, SMA, left AI, and thalamus (Fig. 4B). Overlaps of the above two conjunction analyses were identified in the bilateral VS, left AI, and thalamus (Fig. 4C). Finally, reward consumption among healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions showed overlaps in the bilateral vmPFC and right VS (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. The conjunction analyses for common regions for clinical/at-risk conditions and healthy controls.

(A). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS, vmPFC, and PCC were identified for overlap of activation between clinical/at-risk conditions and healthy controls during reward anticipation. (B). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS and vmPFC were identified for overlap of activation between clinical/at-risk conditions and healthy controls during loss anticipation. (C). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS and vmPFC (yellow) were identified for overlap of conjunction results from A (red) and B (green). (D). Consistent maxima in the bilateral VS and vmPFC were identified for overlap of activation between clinical/at-risk conditions and healthy controls during reward consumption. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

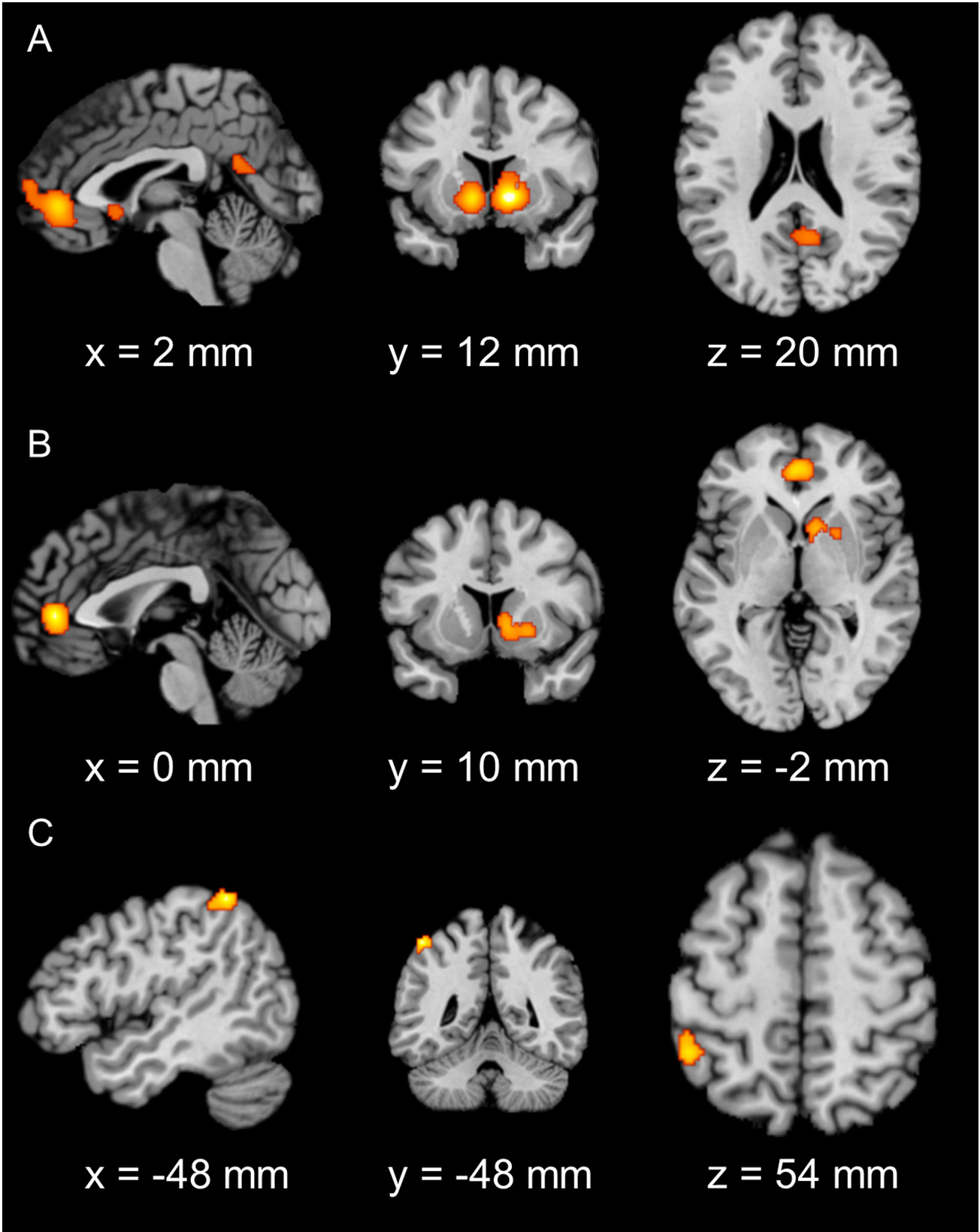

Regarding the contrasts of hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls, reward and loss anticipation showed an overlap in the left VS. That is, clinical/at-risk conditions showed hypoactivation of the left VS compared to healthy controls during the anticipation of both reward and loss (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. The conjunction analyses for common regions for clinical/at-risk conditions vs. healthy controls as well as lesion network results.

(A). Consistent maxima in the left VS were identified in the hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls during reward and loss anticipation conjunction analysis. (B). Bilateral VS and ACC were identified for the overlap of lesion-derived networks (75%). (C). The conjuction (yellow) between results from A (red) and B (green). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In short, our conjunction analyses demonstrated that reward and loss anticipation commonly activate the VS, AI, and thalamus across both healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions. Moreover, reward outcome activates the vmPFC and VS across healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions. Finally, there was a transdiagnostic hypoactivation of the left VS for both reward and loss anticipation.

3.4. Lesions causing apathy or anhedonia

In our literature search for lesions causing apathy or anhedonia, we identified 105 lesion cases (Fig. S4). Lesions were anatomically heterogeneous and comprised of various brain areas. Next, we computed the network associated with each lesion location and identified areas of an overlapping network (Fig. S5).

In spite of marked heterogeneity in lesion location, the lesions causing apathy or anhedonia were parts of a common brain substrate. The level of overlap of lesion-derived networks was high (75%) and occurred mainly within the bilateral VS and anterior cingulate cortex (Fig. 5B). Notably, the left VS was found in the conjunction between the lesion brain network and brain regions identified within the hypoactivation in clinical/at-risk conditions relative to controls within the reward and loss anticipation conjunction analysis (Fig. 5C). In this region of interest (ROI) in the left VS, the connectivity strength was higher for the lesions causing apathy and/or anhedonia compared to those from similarly sized lesions randomized to different locations (P < 3.66 × 10−18) or a group of lesions causing irrelevant neurological symptoms (P < 0.008). Furthermore, similar results were found for the VS ROI identified with the ALE conjunction analysis (i.e., hypoactivation contrast, reward anticipation ∩ loss anticipation), such that the connectivity strength was higher for the lesions causing apathy or anhedonia compared to those from similarly sized lesions randomized to different locations (P < 1.05 × 10−12) or a group of lesions causing irrelevant neurological symptoms (P < 0.003).

In short, our lesion network mapping results indicated that heterogeneous lesions causing loss of motivation are parts of a distributed brain network with the VS as one of its cores. Notably, our results demonstrated an overlap in the left VS between the key nodes identified in the lesion network mapping and the meta-analytic findings on the hypoactivation in the reward and loss anticipation. Finally, the identified network overlap was specific compared to randomized lesions and to lesions causing irrelevant neurological symptoms (Boes et al., 2015). To the best of our knowledge, these findings provide the first empirical evidence showing that the VS subserves a key node in a distributed brain network which encompasses heterogeneous lesion locations causing motivation-related symptoms.

4. Discussion

Motivational dysfunction has been proposed to constitute one of the fundamental dimensions of psychopathology cutting across traditional diagnostic boundaries (e.g., Knutson & Heinz, 2015). The current study examined the hypothesis by exploring the common neurobiological basis of motivation-related deficits across neuropsychiatric conditions, leveraging extensive brain imaging studies employing the MID task among diverse clinical and preclinical samples as well as cumulative cases of lesion-induced motivational symptoms. Consistent with recent frameworks, our meta-analytic results identified transdiagnostic hypoactivation in the VS during the anticipation of both reward and loss. The reliability of meta-analysis findings was further validated by the LOEO analysis. Our findings were also robust to the modulation effects of demographic (e.g., mean age, sex ratio), clinical (e.g., clinical diagnoses, comorbidity), or imaging-specific (e.g., MRI magnetic field strength) factors. Second, the lesion network mapping approach revealed that heterogeneous lesions causing loss of motivation are parts of a distributed brain network with the VS as one of its cores. Notably, we further demonstrated correspondence in the VS between the results derived from our meta-analysis and those from lesion network mapping. To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide meta-analytic evidence of transdiagnostic alternations in neural anticipatory motivation processing that are causally linked to motivation-related deficits. In other words, motivational dysfunction across neuropsychiatric conditions is rooted in disruptions of a common large-scale brain network anchored in the VS.

The current findings agree with dimensional or hierarchical models of psychopathology advocated in past years (Cuthbert, 2014b; Insel, 2014; Lahey et al., 2017). For example, the Research Domain Criteria Project (RDoC) claims that mental disorders may reflect dysfunction in a small number of transdiagnostic functional constructs measured at different levels (e.g., brain-imaging measures) (Insel et al., 2010; Insel & Landis, 2013; Charles A Sanislow, Ferrante, Pacheco, Rudorfer, & Morris, 2019; C. A. Sanislow et al., 2010; Victor et al., 2018). In this regard, brain regions revealed in the current transdiagnostic meta-analyses might correspond to the RDoC dimensional functional construct of negative/positive valence, the abnormalities of which manifest in disorder-spanning symptoms. Moreover, our findings align with the hierarchical models of psychopathology, such that the shared VS alterations might reflect nonspecific neural correlates of second-order factors (e.g., externalizing or internalizing) or the general psychopathology factor (Zald & Lahey, 2017). Notably, it is likely that the transdiagnostic functional construct or higher-order psychopathology factors are embedded in large-scale network disruptions, rather than localized dysfunctions in individual nodes (Buckholtz & Meyer-Lindenberg, 2012; Sha, Wager, Mechelli, & He, 2019; Zald & Lahey, 2017). This conjecture is supported by our lesion network mapping showing that the VS represents a key node in a large-scale network consisting of multiple heterogeneous brain regions, the lesions to which cause motivational impairments. In short, our findings indicate that dysfunctions in the VS-related network represent a transdiagnostic functional construct that underlies motivational impairments in a wide array of mental disorders. These findings provide empirical support to previous frameworks based on narrative reviews (e.g., Knutson & Heinz, 2015; Le Heron et al., 2019) and go beyond previous case-control meta-analyses focusing on lower-level dimensions of psychopathology (e.g., Keren et al., 2018; Radua et al., 2015; W. N. Zhang et al., 2013).

At the anticipation stage, our findings revealed that both reward anticipation and loss anticipation consistently involve the VS, AI, and SMA in both healthy and clinical/at-risk conditions. These findings echo recent meta-analyses on healthy samples (e.g., Dugre et al., 2018; Gu et al., 2019; Oldham et al., 2018; Wilson, et al., 2018) and extend previous observations to the clinical/at-risk conditions. It is thus likely that the VS-related network is implicated in signaling salience of an upcoming event rather than encoding expected positive incentive value (Oldham et al., 2018). This conjecture is supported by the evidence showing that the level of VS activation is increased in proportion to the degree of stimulus saliency regardless of valence (Seymour, Daw, Dayan, Singer, & Dolan, 2007; Zink, Pagnoni, Chappelow, Martin-Skurski, & Berns, 2006; Zink, Pagnoni, Martin, Dhamala, & Berns, 2003; Zink, Pagnoni, Martin-Skurski, Chappelow, & Berns, 2004). Considering the key role of the VS in motivational salience, it is convincible that there are similar VS dysfunctions between reward anticipation and loss anticipation, although previous studies have mainly emphasized the role of VS disruptions in reward processing deficits (e.g., Radua et al., 2015; B. Zhang et al., 2016).

Indeed, the current study provided the first meta-analytic evidence showing common blunted VS activity in response to the anticipation of both reward and loss across multiple neuropsychiatric conditions (e.g., schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and substance use disorders). Aberrant VS activation in both reward and loss anticipation indicates a valence-independent alteration in neural systems involved in approach and avoidance (see also Leknes & Tracey, 2008; Spielberg et al., 2012). In line with the current findings, recent brain imaging studies employing a dimensional approach have demonstrated attenuated VS responses to reward across a wide range of clinical diagnoses (Arrondo et al., 2015; Hagele et al., 2015; A. Li, et al., 2020; Satterthwaite et al., 2015). Moreover, VS activation scales with anhedonia scores or overall depression severity across clinical diagnostic categories (e.g., Arrondo et al., 2015; Corral-Frias et al., 2015; Hagele et al., 2015; Keren et al., 2018; Satterthwaite et al., 2015) and predicts individual differences in approach motivation in general populations (Hahn et al., 2009; Hahn et al., 2011). Together, the common VS hypoactivity to reward/loss anticipation might be a brain phenotype underlying the pathophysiology of motivational deficits (e.g., anhedonia and apathy) spanning categories of mental disorders. The impairments in salience processing could help explain motivation-related symptoms associated with not only rewarding but also aversive signaling (Howes & Nour, 2016; Serranova et al., 2011). The shared alterations of motivation-related brain systems might be attributed to common genetic or environmental risk factors for motivational symptomatology in neuropsychiatric conditions (Buckholtz & Marois, 2012; Corral-Frias et al., 2015).

We next demonstrated that the VS, which exhibited transdiagnostic hypoactivation in response to reward and loss anticipation, served as one of the key nodes in a distributed brain network encompassing multiple lesion locations causing motivational impairments. Noteworthy, the lesion network mapping establishes the causal relationship between brain and behaviour from the perspective of large-scale brain networks rather than isolated brain regions (Fox, 2018). Therefore, the identified network overlap in the VS does not indicate that this region alone plays a casual role in determining motivational impairments. Instead, the results demonstrate that the VS represents a key node in a large-scale network in which multiple brain regions work together to support motivational functioning. The lesion network mapping findings thus complement our meta-analytic results in several essential aspects. First, these findings establish a causal relationship between the VS showing common hypoactivity to reward/loss anticipation and motivation-related symptoms, providing empirical support to previous frameworks (e.g., Husain & Roiser, 2018; Le Heron et al., 2019). Second, our findings are the first to demonstrate that despite being heterogeneous in their anatomical localizations, lesions causing motivational deficits are located within a distributed network with shared functional connectivity to the VS (Groenewegen & Trimble, 2007; Park et al., 2019). These results suggest that the VS is a central hub within the human motivation system. In line with the idea, the VS engages rich structural and functional connectivity with multiple subcortical and cortical brain regions and functions as the crossroad between limbic, cognitive, and motor systems (Groenewegen & Trimble, 2007; Groenewegen, Wright, Beijer, & Voorn, 1999; Park et al., 2019). Together, our lesion network mapping findings not only provide converging evidence on the key role of VS in motivational deficits, but also highlight the importance of large-scale brain networks in the pathophysiology of disorder-spanning motivational dysfunction. This is in line with a recent connectome-wide association study showing that dimensional reward deficits across mental disorders are characterized by dysconnectivity of the VS with large-scale functional networks (Sharma et al., 2017).

Regarding the consumption stage, our findings revealed consistent involvement of the VS and vmPFC for both healthy controls and clinical/at-risk conditions, in line with previous evidence showing that these regions are important for reward consumption (Diekhof et al., 2012; Oldham et al., 2018). However, it should be noted that much fewer studies have reported the results associated with loss consumption, which impedes the investigation of the roles of these regions in processing loss outcomes. Moreover, our results did not reveal consistent differences in the engagement of these regions between groups, suggesting that the consumption phase might be less susceptible to various neuropsychiatric conditions. Indeed, it has been proposed that motivation-related symptoms might be mainly driven by anticipatory deficits rather than by hedonic deficits (Nusslock & Alloy, 2017; Treadway, 2016; Treadway & Zald, 2011). Nevertheless, we identified consistent IPL hyperactivation in the MID reward consumption phase across neuropsychiatric conditions. Although the IPL is not commonly recognized as a typical node within the human motivation system, this region has been implicated in integrating reward and other factors into a unified value representation (MacKay, Blum, & Mendonca, 1992; Parr, Coe, Munoz, & Dorris, 2019; Stanford et al., 2013). In accordance, striatal functional connectivity with the IPL is altered across multiple mental disorders (Marchand et al., 2011; J. T. Zhang et al., 2018). Therefore, future studies are needed to examine psychological functions and clinical significance associated with the IPL hyperactivation during the consumption phase. That being said, the current findings on the IPL hyperactivation should be interpreted with caution due to the reason that the results were not validated by the LOEO analysis and modulated by demographic variables.

Several limitations relevant to the current study should be acknowledged. First, the limited number of experiments for each neuropsychiatric condition precluded the possibility to examine diagnosis-specific alterations in the brain (Barch, 2020; Fusar-Poli, 2019), but statistical power for investigation of both common and distinct abnormalities will increase for future meta-analyses owing to a rapidly growing literature on dimensional psychiatry. Both specific and nonspecific neural correlates are important to a more comprehensive understanding of the hierarchical psychopathology structure, which could help explain both comorbidity and heterogeneity across mental disorders (Zald & Lahey, 2017). Second, although the MID task has been extensively deployed in the literature, the task cannot achieve the full picture of motivational processes; for instance, this task did not allow for capturing reward prediction error signals (Oldham et al., 2018; Wilson, et al., 2018). Third, the numbers of included experiments for different neuropsychiatric conditions and experimental contrasts are not well balanced, but modulation analyses demonstrated that our main findings were not modulated by diagnoses. Finally, modulating effects of potentially influential factors such as illness duration could not be assessed comprehensively as this information was not consistently included across primary studies.

To sum up, the current study examined functional disruptions in neural circuitry underlying motivational processing across multiple diagnoses, combining a meta-analysis on brain imaging studies of the MID task and a lesion network mapping approach. Our findings implicate a common VS-based network of motivation-related deficits in multiple neuropsychiatric conditions. These findings suggest that the encoding of motivational salience in the VS during reward/loss anticipation represents a key functional construct of mental health, the dysfunction of which is a cross-diagnostic domain giving rise to disorder-spanning motivation-related symptoms. Our findings complement recent evidence showing transdiagnostic overlap at multiple units of measurement, ranging from symptoms (Caspi et al., 2014; Lahey et al., 2012) and psychological functions (McTeague, Goodkind, & Etkin, 2016) to brain morphology (Goodkind et al., 2015; Rashid & Calhoun, 2020; Sha, Wager, Mechelli, & He, 2018), brain functions (Feng et al., 2018; Hamilton, Chen, Waugh, Joormann, & Gotlib, 2015; McTeague et al., 2017; McTeague et al., 2020), and genetic factors (Consortium, 2018). Finally, our findings provide possible candidate brain phenotypes (i.e., the VS and its associated network) for future work on neuromodulatory, pharmacological, and clinical interventions across types of psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900757, 31971030, 32071083, 32020103008), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515010746), the Major Program of the Chinese National Social Science Foundation (17ZDA324), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, CAS (2019088), the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH074457), and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 785907 (HBP SGA2). The authors thank Dr. Jingwen Jin and Dr. Yuan Zhou for providing comments on an early version of the manuscript.

Biography

Chunliang Feng is an associate professor at the School of Psychology, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, China. His study focuses on the neural mechanisms underlying reward processing and decision making in both healthy and clinical populations. He also investigates the role of neuropeptides in the improvement of human social functioning.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors are unaware of any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102189.

References

- Arrondo G, Segarra N, Metastasio A, Ziauddeen H, Spencer J, Reinders NR, … Murray GK (2015). Reduction in ventral striatal activity when anticipating a reward in depression and schizophrenia: A replicated cross-diagnostic finding. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1280. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balodis IM, Kober H, Worhunsky PD, Stevens MC, Pearlson GD, & Potenza MN (2012). Diminished frontostriatal activity during processing of monetary rewards and losses in pathological gambling. Biological Psychiatry, 71, 749–757. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM (2020). What does it mean to be transdiagnostic and how would we know? American Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 370–372. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Schlagenhauf F, Wustenberg T, Hein J, Kienast T, Kahnt T, … Wrase J (2009). Ventral striatal activation during reward anticipation correlates with impulsivity in alcoholics. Biological Psychiatry, 66, 734–742. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE, & Aldridge JW (2009). Dissecting components of reward: “Liking”, “wanting”, and learning. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 9, 65–73. 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Knutson B, & Hommer DW (2008). Incentive-elicited striatal activation in adolescent children of alcoholics. Addiction, 103, 1308–1319. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Smith AR, Chen G, & Hommer DW (2012). Mesolimbic recruitment by nondrug rewards in detoxified alcoholics: Effort anticipation, reward anticipation, and reward delivery. Human Brain Mapping, 33, 2174–2188. 10.1002/hbm.21351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes AD, Prasad S, Liu H, Liu Q, Pascual-Leone A, Caviness VS Jr., & Fox MD (2015). Network localization of neurological symptoms from focal brain lesions. Brain, 138, 3061–3075. 10.1093/brain/awv228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainstorm C, Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Walters RK, Bras J, … Gormley P (2018). Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science, 360(6395), eaap8757. 10.1126/science.aap8757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan RA, & Crippa JA (2005). The role of dopamine in reward and pleasure behaviour–Review of data from preclinical research. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111, 14–21. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholtz JW, & Marois R (2012). The roots of modern justice: Cognitive and neural foundations of social norms and their enforcement. Nature Neuroscience, 15, 655–661. 10.1038/nn.3087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholtz JW, & Meyer-Lindenberg A (2012). Psychopathology and the human connectome: Toward a transdiagnostic model of risk for mental illness. Neuron, 74, 990–1004. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Bennett M, Orr C, Icke I, Banaschewski T, Barker GJ, … Consortium I (2019). Mapping adolescent reward anticipation, receipt, and prediction error during the monetary incentive delay task. Human Brain Mapping, 40, 262–283. 10.1002/hbm.24370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, … Moffitt TE (2014). The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 119–137. 10.1177/2167702613497473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium TB (2018). Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science, 360(6395), Article eaap8757. 10.1126/science.aap8757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corp DT, Joutsa J, Darby RR, Delnooz CCS, van de Warrenburg BPC, Cooke D, … Fox MD (2019). Network localization of cervical dystonia based on causal brain lesions. Brain, 142(6), 1660–1674. 10.1093/brain/awz112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Frias NS, Nikolova YS, Michalski LJ, Baranger DA, Hariri AR, & Bogdan R (2015). Stress-related anhedonia is associated with ventral striatum reactivity to reward and transdiagnostic psychiatric symptomatology. Psychological Medicine, 45, 2605–2617. 10.1017/S0033291715000525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN (2014a). The RDoC framework: Continuing commentary. World Psychiatry, 13, 196–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN (2014b). The RDoC framework: Facilitating transition from ICD/DSM to dimensional approaches that integrate neuroscience and psychopathology. World Psychiatry, 13, 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, & Insel TR (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: The seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine, 11, Article 126. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby RR, Horn A, Cushman F, & Fox MD (2018). Lesion network localization of criminal behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 601–606. 10.1073/pnas.1706587115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby RR, Joutsa J, Burke MJ, & Fox MD (2018). Lesion network localization of free will. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 10792–10797. 10.1073/pnas.1814117115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby RR, Laganiere S, Pascual-Leone A, Prasad S, & Fox MD (2017). Finding the imposter: Brain connectivity of lesions causing delusional misidentifications. Brain, 140, 497–507. 10.1093/brain/aww288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekhof EK, Kaps L, Falkai P, & Gruber O (2012). The role of the human ventral striatum and the medial orbitofrontal cortex in the representation of reward magnitude - an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies of passive reward expectancy and outcome processing. Neuropsychologia, 50, 1252–1266. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugre JR, Dumais A, Bitar N, & Potvin S (2018). Loss anticipation and outcome during the monetary incentive delay task: A neuroimaging systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ, 6, Article e4749. 10.7717/peerj.4749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Kurth F, & Fox PT (2012). Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited. Neuroimage, 59, 2349–2361. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Fox PM, Lancaster JL, & Fox PT (2017). Implementation errors in the GingerALE software: Description and recommendations. Human Brain Mapping, 38, 7–11. 10.1002/hbm.23342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, & Fox PT (2009). Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: A random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Human Brain Mapping, 30, 2907–2926. 10.1002/hbm.20718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Nichols TE, Laird AR, Hoffstaedter F, Amunts K, Fox PT, … Eickhoff CR (2016). Behavior, sensitivity, and power of activation likelihood estimation characterized by massive empirical simulation. Neuroimage, 137, 70–85. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot AJ (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 111–116. 10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eshel N, & Roiser JP (2010). Reward and punishment processing in depression. Biological Psychiatry, 68, 118–124. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano A, Laganiere SE, Lam S, & Fox MD (2017). Lesions causing freezing of gait localize to a cerebellar functional network. Annals of Neurology, 81, 129–141. 10.1002/ana.24845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Becker B, Huang W, Wu X, Eickhoff SB, & Chen T (2018). Neural substrates of the emotion-word and emotional counting Stroop tasks in healthy and clinical populations: A meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neuroimage, 173, 258–274. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MA, Lim C, Cooke D, Darby RR, Wu O, Rost NS, … Fox MD (2019). A human memory circuit derived from brain lesions causing amnesia. Nature Communications, 10, 3497. 10.1038/s41467-019-11353-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figee M, Vink M, de Geus F, Vulink N, Veltman DJ, Westenberg H, & Denys D (2011). Dysfunctional reward circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 69, 867–874. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DB, Boes AD, Demertzi A, Evrard HC, Laureys S, Edlow BL, … Geerling JC (2016). A human brain network derived from coma-causing brainstem lesions. Neurology, 87, 2427–2434. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K, Towler J, & Eimer M (2016). Facial identity and facial expression are initially integrated at visual perceptual stages of face processing. Neuropsychologia, 80, 115–125. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD (2018). Mapping symptoms to brain networks with the human connectome. New England Journal of Medicine, 379, 2237–2245. 10.1056/NEJMra1706158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P (2019). TRANSD recommendations: Improving transdiagnostic research in psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 18, 361–362. 10.1002/wps.20681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, Jiang Y, Chang A, Jones-Hagata LB, … Etkin A (2015). Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 305–315. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm O, Heinz A, Walter H, Kirsch P, Erk S, Haddad L, … Meyer-Lindenberg A (2014). Striatal response to reward anticipation: Evidence for a systems-level intermediate phenotype for schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 531–539. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm O, Kaiser S, Plichta MM, & Tobler PN (2017). Altered reward anticipation: Potential explanation for weight gain in schizophrenia? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 75, 91–103. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, & Trimble M (2007). The ventral striatum as an interface between the limbic and motor systems. CNS Spectrums, 12, 887–892. 10.1017/S1092852900015650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Wright CI, Beijer AV, & Voorn P (1999). Convergence and segregation of ventral striatal inputs and outputs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 877, 49–63. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu R, Huang W, Camilleri J, Xu P, Wei P, Eickhoff SB, & Feng C (2019). Love is analogous to money in human brain: Coordinate-based and functional connectivity meta-analyses of social and monetary reward anticipation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 100, 108–128. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevitch J, Koricheva J, Nakagawa S, & Stewart G (2018). Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature, 555, 175–182. 10.1038/nature25753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, & Knutson B (2010). The reward circuit: Linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 4–26. 10.1038/npp.2009.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagele C, Schlagenhauf F, Rapp M, Sterzer P, Beck A, Bermpohl F, … Heinz A (2015). Dimensional psychiatry: Reward dysfunction and depressive mood across psychiatric disorders. Psychopharmacology, 232, 331–341. 10.1007/s00213-014-3662-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn T, Dresler T, Ehlis AC, Plichta MM, Heinzel S, Polak T, … Fallgatter AJ (2009). Neural response to reward anticipation is modulated by Gray’s impulsivity. Neuroimage, 46, 1148–1153. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn T, Heinzel S, Dresler T, Plichta MM, Renner TJ, Markulin F, … Fallgatter AJ (2011). Association between reward-related activation in the ventral striatum and trait reward sensitivity is moderated by dopamine transporter genotype. Human Brain Mapping, 32, 1557–1565. 10.1002/hbm.21127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halahakoon DC, Kieslich K, O’Driscoll C, Nair A, Lewis G, & Roiser JP (2020). Reward-processing behavior in depressed participants relative to healthy volunteers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77, 1286–1295. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JP, Chen MC, Waugh CE, Joormann J, & Gotlib IH (2015). Distinctive and common neural underpinnings of major depression, social anxiety, and their comorbidity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10, 552–560. 10.1093/scan/nsu084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen E, van der Velde J, Gromann PM, Shergill SS, de Haan L, Bruggeman R, … van Atteveldt N (2015). Neural correlates of reward processing in healthy siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, Article 504. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280–1300. 10.1037//0003-066x.52.12.1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes OD, & Nour MM (2016). Dopamine and the aberrant salience hypothesis of schizophrenia. World Psychiatry, 15, 3–4. 10.1002/wps.20276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain M, & Roiser JP (2018). Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: A transdiagnostic approach. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19, 470–484. 10.1038/s41583-018-0029-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR (2014). The NIMH research domain criteria (RDoC) project: Precision medicine for psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 395–397. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, … Wang P (2010). Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a New Classification Framework for Research on Mental Disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, & Landis SC (2013). Twenty-five years of Progress: The View from NIMH and NINDS. Neuron, 80, 561–567. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins LM, Barba A, Campbell M, Lamar M, Shankman SA, Leow AD, … Langenecker SA (2016). Shared white matter alterations across emotional disorders: A voxel-based meta-analysis of fractional anisotropy. NeuroImage: Clinical, 12, 1022–1034. 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, & Smith SM (2012). FSL. Neuroimage, 62, 782–790. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutsa J, Horn A, Hsu J, & Fox MD (2018). Localizing parkinsonism based on focal brain lesions. Brain, 141, 2445–2456. 10.1093/brain/awy161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Wustenberg T, Villringer A, Knutson B, … Heinz A (2006). Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenia. Neuroimage, 29, 409–416. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczkurkin AN, Moore TM, Calkins ME, Ciric R, Detre JA, Elliott MA, … Rosen A (2018). Common and dissociable regional cerebral blood flow differences associate with dimensions of psychopathology across categorical diagnoses. Molecular Psychiatry, 23(10), 1981–1989. 10.1038/mp.2017.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczkurkin AN, Park SS, Sotiras A, Moore TM, Calkins ME, Cieslak M, … Satterthwaite TD (2019). Evidence for dissociable linkage of dimensions of psychopathology to brain structure in youths. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 1000–1009. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18070835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katharina K, White L, Tseng W-L, Jillian L, & Wiggins A (2018). Latent Variable Approach to Differentiating Neural Mechanisms of Irritability and Anxiety in Youth. JAMA Psychiatry, 75, 631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keren H, O’Callaghan G, Vidal-Ribas P, Buzzell GA, Brotman MA, Leibenluft E, … Stringaris A (2018). Reward processing in depression: A conceptual and meta-analytic review across fMRI and EEG studies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 1111–1120. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Adams CM, Fong GW, & Hommer D (2001). Anticipation of increasing monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience, 21, Article RC159. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0002.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Bhanji JP, Cooney RE, Atlas LY, & Gotlib IH (2008). Neural responses to monetary incentives in major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 686–692. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, & Cooper JC (2005). Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reward prediction. Current Opinion in Neurology, 18, 411–417. 10.1097/01.wco.0000173463.24758.f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, & Hommer D (2001). Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport, 12, 3683–3687. 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, & Greer SM (2008). Anticipatory affect: Neural correlates and consequences for choice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B: Biological Sciences, 363, 3771–3786. 10.1098/rstb.2008.0155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, & Heinz A (2015). Probing psychiatric symptoms with the monetary incentive delay task. Biological Psychiatry, 77, 418–420. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Westdorp A, Kaiser E, & Hommer D (2000). FMRI visualization of brain activity during a monetary incentive delay task. Neuroimage, 12, 20–27. 10.1006/nimg.2000.0593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganiere S, Boes AD, & Fox MD (2016). Network localization of hemichorea-hemiballismus. Neurology, 86, 2187–2195. https://doi.org/10.1212WNL.0000000000002741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Hakes JK, Zald DH, Hariri AR, & Rathouz PJ (2012). Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 971–977. 10.1037/a0028355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ, Waldman ID, & Zald DH (2017). A hierarchical causal taxonomy of psychopathology across the life span. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 142–186. 10.1037/bul0000069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Singh AL, Waldman ID, & Rathouz PJ (2011). Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 181–189. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird AR, Fox PM, Price CJ, Glahn DC, Uecker AM, Lancaster JL, … Fox PT (2005). ALE meta-analysis: Controlling the false discovery rate and performing statistical contrasts. Human Brain Mapping, 25, 155–164. 10.1002/hbm.20136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster JL, Tordesillas-Gutiérrez D, Martinez M, Salinas F, Evans A, Zilles K, … Fox PT (2007). Bias between MNI and Talairach coordinates analyzed using the ICBM 152 brain template. Human Brain Mapping, 2, 1194–1205. 10.1002/hbm.20345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Heron C, Holroyd CB, Salamone J, & Husain M (2019). Brain mechanisms underlying apathy. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 90, 302–312. 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leknes S, & Tracey I (2008). A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 314–320. 10.1038/nrn2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Zalesky A, Yue W, Howes O, Yan H, Liu Y, … Li B (2020). A neuroimaging biomarker for striatal dysfunction in schizophrenia. Nature Medicine, 26, 558–565. 10.1038/s41591-020-0793-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Wang L, Camilleri JA, Chen X, Li S, Stewart JL, … Feng C (2020). Mapping common grey matter volume deviation across child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 115, 273–284. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz K, & Widmer M (2014). What can the monetary incentive delay task tell us about the neural processing of reward and punishment. Neuroscience and Neuroeconomics, 3, 33–45. 10.2147/NAN.S38864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay WA, Blum B, & Mendonca AJ (1992). Visual responses to reward-related cues in inferior parietal lobule. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 12, 209–214. 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1992.tb00292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand WR, Lee JN, Garn C, Thatcher J, Gale P, Kreitschitz S, … Wood N (2011). Striatal and cortical midline activation and connectivity associated with suicidal ideation and depression in bipolar II disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133, 638–645. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]