Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is one of the major microvascular complications of diabetes and is leading cause of end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) and one of major risk factors of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is one of the major microvascular complications of diabetes and is represented by albuminuria and a decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in people with diabetes. DKD is the leading cause of end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) and one of major risk factors of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The number of diabetic patients has increased continuously over the past few decades, and the prevalence of DKD is also increasing despite the rapid advances in medical care. According to Wang et al. 1 , the prevalence of DKD among diabetic patients in Taiwan was 13.32% in 2000, 15.42% in 2009, and 17.92% in 2014, increasing steadily. And the prevalence of ESRD requiring dialysis among people with diabetes increased from 1.32% in 2005 to 1.47% in 2014. In addition, Global Burden of Disease data from 1990 to 2017 showed a significant increase in the global burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as a result of type 2 diabetes worldwide 2 . To reduce the social and economic burden of DKD, early diagnosis and active intervention are required.

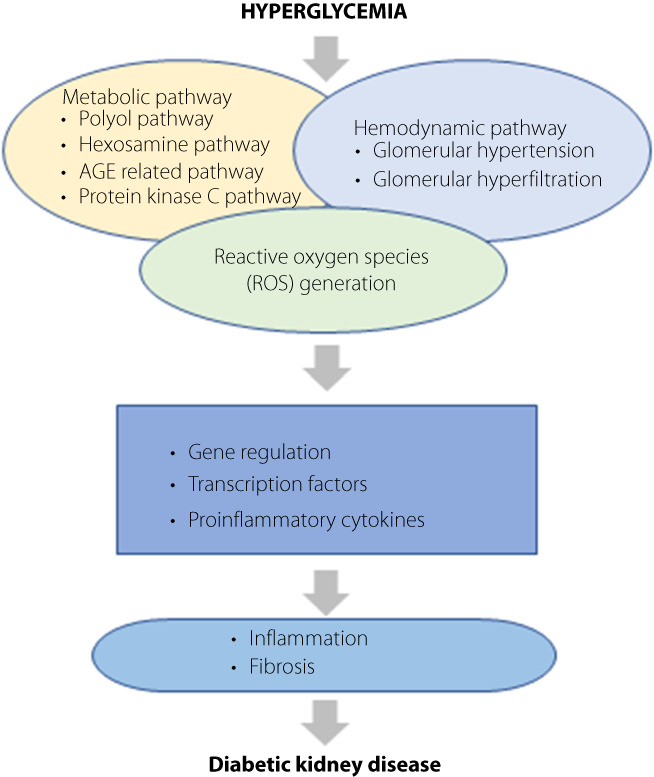

The pathophysiology of DKD is very complicated and not yet understood completely. Various pathophysiological pathways, including hemodynamic, metabolic, and inflammatory pathways, are thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of DKD (Figure 1) 3 , 4 , 5 . The hemodynamic pathway involves increased intraglomerular pressure and hyperfiltration. Hyperglycemia leads to several metabolic pathways: polyol pathway, hexosamine pathway, production of advanced glycation end‐product (AGE), and protein kinase C (PKC) pathway. In addition, the inflammatory process has also been considered as an important factor in the development and progression of DKD. Various studies reported the association between inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) and interleukin (IL) – 1, 6, 18 and DKD development 4 . Gohda et al. 6 reported that albuminuria and eGFR had a stronger association with serum tumor necrosis factor receptors (TNFRs) than urine TNFRs in type 2 diabetic patients. They suggested serum TNFRs could be sensitive markers for renal function compared with urinary TNFRs.

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). The pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is most likely the result of the interaction of multiple pathways, including metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities. In hyperglycemia, increased glucose filtration in the glomerulus and reabsorption in the proximal tubules leads to an inadequate decrease in afferent arteriole resistance and a subsequent increase in intraglomerular pressure, followed by glomerular hypertension and hyperfiltration. In addition, hyperglycemia activates several metabolic pathways, such as polyol pathway, hexosamine pathway, protein kinase C activation, and advanced glycation end‐product (AGE) formation. This all results in the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The interaction between metabolic abnormalities, hemodynamic factors and ROS generation affects gene regulation and the activation of transcription factors and stimulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. This leads to kidney inflammation and fibrosis, finally resulting in DKD. AGE, advanced glycation end‐product; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

It is important to identify the risk factors of renal impairment in diabetic patients and to prevent progression to ESRD. Hyperglycemia and hypertension are traditional risk factors for the progression of DKD, and glomerular hyperfiltration, smoking, race, male, age, and genetic factors are also known to be involved in the development and progression of DKD 7 . The other putative risk factor for DKD is dyslipidemia, but whether statin‐assisted lipid‐lowering therapy is beneficial in the progression of DKD remains controversial. However, Shikata et al. 8 reported that lowering low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol using statins improved renal outcomes in patients with advanced DKD with overt proteinuria. A recent study has shown that urine glucose levels also influence the renal prognosis in diabetic patients. Itano et al. reported that high urinary glucose excretion in diabetic patients not using sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors has a favorable renal prognosis, especially in men and in long duration diabetes (>10 years) 9 . Although the renoprotective mechanism of SGLT2 inhibitors are not yet clear, it is suggested that an increase in renal glucosuria has a therapeutic effect.

In the past few years, many studies have been published showing that the SGLT2 inhibitors have a protective effect on CVD and the progression of DKD. Wada et al. 10 performed a post hoc analysis evaluating the efficacy and safety of canagliflozin in a subgroup of participants from East and South‐East Asian (EA) countries at high risk of renal complications. Consistent with the results of the Canagliflozin and Renal Events in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) trial, canagliflozin reduced the risk of renal and cardiovascular events in patients with high‐risk renal events in EA. Hirai et al. 11 reported that SGLT2 inhibitors could slow the rate of eGFR decline even in patients with type 2 diabetes with reduced renal function (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2). SGLT2 inhibitors reduce the risk of adverse renal events, but conversely, SGLT2 inhibitors may cause acute kidney injury (AKI) as a result of hypovolemia due to osmotic diuresis. Horii et al. 12 investigated risk factors for AKI in patients with type 2 diabetes using SGLT2 inhibitors, and they reported that the risk of AKI is increased in men, aged 65 and older, low body mass index (BMI), history of heart failure, and diuretic use. As SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to ameliorate cardiovascular and renal disease events, the percentage administration of SGLT2 inhibitors may be increased in patients with type 2 diabetes with impaired renal or cardiac function. In order to safely use SGLT2 inhibitors, it is necessary to understand the drug properties, including the side effects.

This article briefly reviews the mechanism of development of DKD, and examines the latest trends and the risk factors of DKD. Recently, antidiabetic drugs with renal protective effects such as SLGT2 inhibitors and glucagon‐like peptide (GLP)‐1 receptor agonist have been developed, which is expected to lead to great progress in the management of DKD.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wang JS, Yen FS, Lin KD, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of diabetic kidney disease in Taiwan. J Diabetes Investig 2021; 12: 2112–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li H, Lu W, Wang A, et al. Changing epidemiology of chronic kidney disease as a result of type 2 diabetes mellitus from 1990 to 2017: estimates from global burden of disease 2017. J Diabetes Investig 2021; 12: 346–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sugahara M, Pak WLW, Tanaka T, et al. Update on diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of diabetic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2021; 26: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toth‐Manikowski S, Atta MG. Diabetic kidney disease: pathophysiology and therapeutic targets. J Diabetes Res 2015; 2015: 697010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cao Z, Cooper ME. Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Investig 2011; 2: 243–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gohda T, Kamei N, Kubota M, et al. Fractional excretion of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2 in patients with type 2 diabetes and normal renal function. J Diabetes Investig 2021; 12: 382–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, et al. Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 164–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shikata K, Haneda M, Ninomiya T, et al. Randomized trial of an intensified, multifactorial intervention in patients with advanced‐stage diabetic kidney disease: diabetic nephropathy remission and regression team trial in Japan (DNETT‐Japan). J Diabetes Investig 2021; 12: 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Itano Y, Sobajima H, Ohashi N, et al. High urinary glucose is associated with improved renal prognosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2021; 12: 998–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wada T, Mori‐Anai K, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Renal, cardiovascular and safety outcomes of canagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy in east and south‐east Asian countries: results from the canagliflozin and renal events in diabetes with established nephropathy clinical evaluation trial. J Diabetes Investig 2022; 13: 54–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirai T, Kitada M, Monno I, et al. Sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes patients with renal function impairment slow the annual renal function decline, in a real clinical practice. J Diabetes Investig 2021; 12: 1577–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horii T, Oikawa Y, Kunisada N, et al. Acute kidney injury in Japanese type 2 diabetes patients receiving sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: a nationwide cohort study. J Diabetes Investig 2022; 13: 42–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]