Abstract

The experiment aimed to study effects of dietary metabolizable energy (ME) and crude protein (CP) levels alone and in interaction on performance, pectoral muscle composition and gut microbiota in native growing chickens. A total of 648 10-wks-old Beijing-You Chicken (BYC) female chickens were randomly allocated to 9 groups with 6 replicates per group and 12 chickens per replicate, and the chickens were fed with a 3 × 3 factorial diets (3 levels of dietary ME: 11.31 MJ/kg, 11.51 MJ/kg, 11.71 MJ/kg; and 3 levels of dietary CP: 14%, 15%, 16%). The results showed that dietary ME and CP levels didn't affect average feed intake (AFI), body weight gain, feed gain ratio (P > 0.05), but ME level significantly affected the AFI (P < 0.05); mortality rate of 11.31 MJ/kg group was the highest (P < 0.05). Dietary ME, CP levels, and the interaction significantly affected pectoral CP and crude fat (CF) content of the growing chickens (P < 0.01). Dietary CP level had opposite effects on pectoral CP and CF content (P < 0.01). The 16% CP increased the pectoral CF content, which may have a negative impact on meat flavor. Dietary ME level affected 11 types of pectoral free amino acids (FAA) contents, including aspartic acid, L-threonine (P < 0.05), also amino acid classification, for example, total amino acid (TAA) and essential amino acid (EAA) content (P < 0.05). The 11.51 MJ/kg group had the highest TAA, EAA, delicious amino acid (DAA) content and EAA percentage (P < 0.05), while 11.31 MJ/kg group had the lowest bitter amino acid (BAA) content and BAA percentage and the highest fresh and sweet amino acid (FSAA) percentage (P < 0.05). Dietary CP level significantly affected glutamine and tyrosine content (P < 0.05). The interaction of dietary ME and CP level affected C20:3n6 content, saturated fatty acid (SFA), and unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) percentage (P < 0.05). The CP level significantly affected SFA percentage (P < 0.05). The 16% CP level increased the diversity of gut microbiota, but at the same time increased the relative abundance of Proteobacteria (P < 0.05), which is a sign of microbiota disorder. The increase of dietary ME level resulted in a gradual decrease in the diversity and relative abundance of gut microbiota. In conclusion, the present study suggested that the medium dietary ME (11.51 MJ/kg) and low CP (14–15%) levels can be helpful for enhancing pectoral muscle composition, increase meat quality such as flavor and nutritional value, and benefit for gut microbiota in native growing chickens.

Key words: crude protein, energy, meat quality, growing chicken, gut microbiota

INTRODUCTION

The gut microbiota plays an important role in the overall health and function of the host (Stanley et al., 2014; Sánchez et al., 2008). The gut microbiota of poultry is influenced by diet, age, antibiotic use, and infection by pathogenic organisms (Zimmermann et al., 2019; Pont et al., 2020). Diet is one of the most critical factors in shaping the gut microbiota (De Filippo et al.,2010; Carmody et al., 2015), and the most critical aspects are dietary metabolizable energy (ME) and crude protein (CP) levels. Low CP diets helped control faecal microbiota characteristics without affecting production of AA broilers (Laudadio et al., 2012). Variation in dietary ME levels had a significant effect on bacterial composition of animals (Daniel et al., 2014). A study on Pekin ducks showed that ME levels affected the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota (Liu et al., 2019).

Appropriate levels of ME and CP are necessary to ensure nutritional level of the diet and to promote healthy growth of poultry. When the ME and CP ratio is appropriate, poultry grow faster, have higher feed conversion and production (Musigwa et al., 2021). Previous studies on the interaction of ME and CP levels varied depending on different environment, production system, breeds, etc.

In recent years, with the improvement of people's living standards, consumers have placed higher demands on meat quality. Dietary ME and CP levels are two most important factors affecting meat quality. Low dietary ME reduced abdominal fat of broilers (Fan et al., 2008; Abdel-Hafeez et al., 2016) and improved tenderness. Increasing CP levels significantly reduced content of abdominal fat, carcass, and breast and leg muscles, and increased pectoral CP content in broiler (Marcu et al., 2013), affecting the quality indicators (Jlali et al., 2012). Excess dietary ME can lead to increased fat deposition and reduced carcass quality, while low CP diets can reduce the energy required to break down dietary protein and excrete excess amino acids, while improving nitrogen utilization and reducing nitrogen emissions (Girish et al., 2013). Oyedeji et al. (2005) suggested that 13.38 MJ/Kg is optimal for broiler chickens; while energy level is 12.96 MJ/Kg for broilers at 0 to 4 wk of age and 13.18 MJ/Kg at 4 to 8 wk of age (Nahashon et al., 2005).

Dietary ME and CP also affect the meat composition, especially protein and fat contents and free amino acids (FAA), fatty acids (FA) composition. The content and composition not only determine its nutritional value but also affect meat quality indicators such as tenderness and flavor. Dietary ME and CP levels had significant effects on pectoral Glu content and FA content in 63-day-old yellow broilers (Jiang et al., 2013). While higher ME levels improved pectoral quality of Cobb broiler chicks and had a positive effect on pectoral FAA (Akbari et al., 2017).

Beijing You Chicken (BYC), a native chicken for meat and egg production in Beijing district, is generally marketed at 110 to 120 days of age with an average weight of 1.4 to 1.6 kg. The FAA, intramuscular fat, and unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) content of BYC meat were significantly higher than that of other chickens, with the FAA content reaching 6.4 g/kg, the intramuscular fat content reaching 10.9 g/kg and the UFA content reaching 4.9 g/kg, having delicious meat and a rich flavor (Liu, 2020). However, whether dietary ME and CP levels affect the pectoral muscle composition and gut microbiota remains unclear for the native bird. Our group compared 6 levels of dietary CP (16.0%, 15.8%, 15.6%, 15.4%, 15.2%, and 15.0%) on performance and found that 15.8% CP can meet the requirement of BYC laying hens aged from 32 to 43 wks (Geng et al., 2014). This study was conducted to compare the effects of dietary ME and CP levels alone and in interaction on performance, pectoral muscle composition and gut microbiota in growing chickens, in order to provide a reference for healthy breeding of the native chickens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design and Chickens

The experiment was conducted at a BYC rearing farm, Shunyi district, Beijing. A total of 648 10-wks-old BYC female growing chickens were randomly allocated to 9 groups with 6 replicates per group and 12 chickens per replicate (one replicate three cages, 4 birds a cage) and the average weight was 581.46 g. A 3 × 3 factorial experiment was arranged, and the chickens were fed with 3 levels of dietary ME (11.31 MJ/kg, 11.51 MJ/kg, 11.71 MJ/kg) and 3 levels of dietary CP (14%, 15%, 16%). The settings of ME and CP levels were adjusted up and down according to the recommended levels in “Technical regulation of Beijing You Chicken Feed and Management” (DB11/T 1378, 2016). Each group was randomly fed with one of the 9 diets. The composition and nutrient levels of the diets were seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition and nutrient levels of the experimental diets.

| ME, MJ/kg | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.71 | 11.71 | 11.71 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP, % | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Corn | 65.3 | 63.5 | 62.8 | 68.8 | 66 | 62.6 | 68 | 68 | 66 |

| Wheat bran | 13.5 | 12 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| Soybean meal | 15.7 | 19 | 22.5 | 16.5 | 19.5 | 22.5 | 17 | 20.5 | 23.5 |

| Soybean oil | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Premix1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Nutritional levels2 | |||||||||

| ME, MJ/kg | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.32 | 11.51 | 11.52 | 11.51 | 11.72 | 11.71 | 11.70 |

| CP, % | 14.01 | 15.04 | 16.03 | 14.00 | 14.98 | 15.99 | 14.04 | 15.04 | 16.03 |

| Lysine, % | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Methione + Cystine, % | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| Calcium, % | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.72 |

| Total phosphorus, % | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.60 |

| Available phosphorus, % | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

Premix provided per kilogram of diet: Vitamin A, 6000 IU; Vitamin D, 2800 IU; Vitamin E, 20 IU; Vitamin K, 2.4 mg; Vitamin B12, 0.027 mg; Thiamine, 2.0 mg; Riboflavin, 5.2 mg; D-Calcium pantothenate, 11 mg; Niacin, 30 mg; Pyridoxine, 3.6 mg; Biotin, 0.2 mg; Folic acid, 1.2 mg; Choline, 800 mg; Manganese, 90 mg; Iodine, 1.8 mg; Ferrous, 100 mg; Copper, 8 mg; Zinc, 80 mg; Selenium, 0.30 mg. Any deficiencies in the methionine and lysine content of the diets were made up in the 5% premix.

CP, calcium, and available phosphorus are measured values, the rest of the nutrient levels are calculated from the data provided by Feed Database in China (2013).

Feeding and Management

The chickens were reared in 3-story A-type cages, and the replicate cages were evenly distributed in the house. The chickens were fed ad libitum, and immunized according to normal immunization procedures. The management were manipulated according to “Technical regulation of Beijing You Chicken Feed and Management” (DB11/T 1378, 2016). The adjustment experimental period was 3 days and formal experimental period was from 10 to 16 wks of age.

Measurement Indicators and Methods

Feed intake and body weight of each replicate cage were recorded and the average feed intake (AFI), body weight gain (BWG), feed gain ratio (F/G) and mortality rate were calculated at 10 to 16 wks of age. Once a chicken was found dead, the weight of the dead chicken, the time of death, and the remaining feed for the cage will be recorded in time, and the F/G were corrected from mortality.

At the end of 16 wks, 6 chickens from each group were randomly chosen and euthanized by cervical dislocation, then pectoral muscle composition were measured. The pectoral muscles were freeze-dried by using freeze dryer (LD53, Millrock Technology, Kingston, NY) and pectoral CP, CF, FAA, FA were measured. The cecum was separated and the digesta was gently extruded, stored in liquid nitrogen, and then transferred to −80°C for later analysis. 0.25 g freeze dried sample was used to measure pectoral CP by using Kjeldahl nitrogen tester (K1160, Hanon, China); 5 g freeze dried sample was used to measure pectoral CF by Soxhlet extraction method by using a CF tester (SER148, VELP, Italy); 1 g freeze dried samples with fat extracted were used for FAA analysis by using an amino acid analyzer (L8900, HITACHI, Japan); 5 g freeze dried sample was used to measure FA content by using high performance gas chromatograph (HP 6890, Agilent, Palo Alto, CA).

Cecal contents from 4 chickens in each group were used for measurement of microbiota. Microbial community genomic DNA was extracted from cecal content using E.Z.N.A. soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA) according to manufacturer's instructions. The DNA extract was checked on 1% agarose gel, and DNA concentration and purity were determined with NanoDrop 2000 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, NC). The hypervariable region V3 to V4 of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified with primer pairs 343F-5′-TACGGRAGGCAGCAG-3′ and the back-end primer: 798R-5′- AGGGTATCTAATCCT-3′ by an ABI Gene Amp 9700 PCR thermocycler (ABI, CA). PCR reactions were performed in triplicate. The PCR product was extracted from 2% agarose gel and purified using Axy Prep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axy gen Biosciences, Union City, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions and quantified using Quantus Fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI). After PCR reactions, amplification products were recovered, library construction was completed, library fragment ranges and concentrations were checked. Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar and paired-end sequenced (2 × 300) on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the standard protocols by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The DNA sequences are publicly available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive and are accessible under BioProject accession number PRJNA841792.

Statistical Analysis

The main effects of ME and CP levels were analyzed using the general linear model (GLM) in SPSS 25.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Duncan's Test was used for multiple comparisons. The percentage was arcsine transformed before the normality test, with P < 0.01 as very statistically significant, P < 0.05 as statistically significant, and 0.05< P < 0.10 as having a significant trend.

RESULTS

Performance

Table 2 showed that the interaction of dietary ME and CP levels had no significant effects on AFI, BWG, F/G (P > 0.05), but ME level alone significantly affected AFI (P < 0.05); mortality rate of 11.51 MJ/kg and 11.71 MJ/kg group were significantly lower than that of 11.31 MJ/kg group (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on performance of 10–16 wks of age.

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % | AFI, g | BWG, g | F/G | Mortality, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 14 | 3,621.38 | 535.01 | 6.78 | 6.94 |

| 11.31 | 15 | 3,591.03 | 591.22 | 6.07 | 4.17 |

| 11.31 | 16 | 3,698.43 | 627.93 | 5.88 | 4.17 |

| 11.51 | 14 | 3,550.00 | 558.75 | 6.35 | 0 |

| 11.51 | 15 | 3,594.17 | 636.39 | 5.64 | 0 |

| 11.51 | 16 | 3,552.39 | 546.84 | 6.49 | 4.17 |

| 11.71 | 14 | 3,519.82 | 517.12 | 6.81 | 4.17 |

| 11.71 | 15 | 3,623.06 | 559.26 | 6.48 | 1.38 |

| 11.71 | 16 | 3,332.45 | 512.19 | 6.50 | 1.38 |

| SEM | 26.96 | 11.39 | 0.11 | 0.59 | |

| Main effects | |||||

| ME | 11.31 | 3,636.95 | 584.72 | 6.22 | 5.09a |

| 11.51 | 3,565.21 | 580.66 | 6.14 | 1.39b | |

| 11.71 | 3,491.77 | 529.53 | 6.59 | 2.31b | |

| P-value | 0.079 | 0.072 | 0.132 | 0.023 | |

| CP | 14 | 3,563.73 | 536.90 | 6.64 | 3.70 |

| 15 | 3,602.75 | 595.63 | 6.05 | 1.85 | |

| 16 | 3,527.76 | 562.32 | 6.27 | 3.24 | |

| P-value | 0.493 | 0.089 | 0.082 | 0.365 | |

| ME × CP | P-value | 0.145 | 0.288 | 0.409 | 0.216 |

Data in the same column without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P < 0.01 as highly significant, P < 0.05 as significant), the same below.

Pectoral CP, CF and Moisture Content

Table 3 showed that dietary ME and CP levels alone and in interaction affected pectoral CP and CF content (P < 0.01). The pectoral CP content of 11.51 MJ/kg ME group (94.80%) was lower than that of the other 2 groups (P < 0.05), the pectoral CF content of 11.31 MJ/kg ME group (3.31%) was lower than that of the other two groups (P < 0.01), the pectoral CF content of 11.51 MJ/kg group (4.79%) was the highest (P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on pectoral CP, CF, and moisture content (dry matter basis).

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % | Crude protein, % | Crude fat, % | Moisture, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 14.0 | 95.86b | 3.33c | 74.77 |

| 11.31 | 15.0 | 95.01cd | 3.60bc | 74.80 |

| 11.31 | 16.0 | 95.57c | 3.00ce | 74.78 |

| 11.51 | 14.0 | 92.84e | 6.43a | 74.07 |

| 11.51 | 15.0 | 96.67a | 3.27c | 74.92 |

| 11.51 | 16.0 | 94.88d | 4.67b | 74.24 |

| 11.71 | 14.0 | 95.09cd | 4.46bc | 74.99 |

| 11.71 | 15.0 | 96.16ab | 3.29c | 74.70 |

| 11.71 | 16.0 | 95.31cd | 4.90b | 74.70 |

| SEM | 0.072 | 0.148 | 0.153 | |

| Main effects | ||||

| ME | 11.31 | 95.48a | 3.31b | 74.79 |

| 11.51 | 94.80b | 4.79a | 74.41 | |

| 11.71 | 95.52a | 4.22a | 74.80 | |

| P-value | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.51 | |

| CP | 14.0 | 94.60c | 4.74a | 74.61 |

| 15.0 | 95.94a | 3.39b | 74.81 | |

| 16.0 | 95.26b | 4.19a | 74.58 | |

| P-value | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.80 | |

| ME × CP | P-value | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.783 |

Data in the same column without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P < 0.01 as highly significant, P < 0.05 as significant)

The pectoral CP content of 15% CP group (95.94%) was significantly higher than that of the other 2 groups (P < 0.01), while the pectoral CF content (3.39%) was the lowest in 15% CP group (P < 0.01).

Pectoral FAA Content and Proportions

Table 4a showed that the interaction of dietary ME and CP levels affected most of free amino acid content including aspartic acid (Asp), L-threonine (Thr), serine (Ser), glutamine (Glu), alanine (Ala), methionine (Met), leucine (Leu), tyrosine (Tyr), lysine (Lys), arginine (Arg), total amino acid (TAA), essential amino acid (EAA), fresh and sweet amino acid (FSAA), bitter amino acid (BAA), delicious amino acid (DAA) (P < 0.05), and there was a significant trend for proline (Pro), glycine (Gly), and isoleucine (Ile) (0.05<P<0.1).

Table 4a.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on pectoral free amino acid content (dry matter basis) g/100 g.

| ME, MJ/kg | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.71 | 11.71 | 11.71 | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP, % | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

| Asp# | 7.59ab | 7.38b | 7.42b | 7.59ab | 7.63ab | 7.63ab | 7.46b | 7.70a | 7.56ab | 0.02 | 0.018 |

| Thr*# | 3.65a | 3.54ab | 3.52b | 3.48b | 3.48b | 3.49bc | 3.42bc | 3.63a | 3.57ab | 0.01 | 0.002 |

| Ser# | 3.02a | 2.85b | 2.79bc | 2.67c | 2.67c | 2.69c | 2.68c | 2.97ab | 2.96ab | 0.02 | 0.001 |

| Glu# | 11.72a | 11.18b | 11.22b | 11.68a | 11.82a | 11.67a | 11.67a | 11.80a | 11.55a | 0.03 | 0.009 |

| Pro*# | 3.21a | 3.00b | 3.06ab | 3.03ab | 3.19a | 3.01b | 3.12ab | 3.00b | 3.07ab | 0.02 | 0.063 |

| Gly# | 4.00a | 3.71b | 3.81ab | 3.81ab | 4.01a | 3.75ab | 3.92ab | 3.79ab | 3.93ab | 0.03 | 0.069 |

| Ala# | 4.84ab | 4.64bc | 4.68bc | 4.73bc | 4.89a | 4.82ab | 4.75ab | 4.92a | 4.87a | 0.02 | 0.004 |

| Val*^ | 3.96b | 3.87b | 4.03b | 4.45ab | 4.50a | 4.55a | 4.34b | 4.31b | 4.25b | 0.02 | 0.141 |

| Met*^ | 2.79a | 2.71b | 2.70bc | 2.65bc | 2.69bc | 2.68bc | 2.62c | 2.81a | 2.72b | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| Ile*^ | 3.78c | 3.68c | 3.83c | 4.17ab | 4.19ab | 4.22a | 4.07b | 4.13ab | 4.01b | 0.02 | 0.072 |

| Leu*^ | 6.48ab | 6.31b | 6.37b | 6.45b | 6.47ab | 6.48ab | 6.34b | 6.59a | 6.46ab | 0.02 | 0.009 |

| Tyr^ | 2.80a | 2.71ab | 2.70ab | 2.37c | 2.37c | 2.40c | 2.36c | 2.74ab | 2.67b | 0.01 | 0.000 |

| Phe*^ | 4.36ab | 4.26b | 4.29b | 4.38ab | 4.39ab | 4.45a | 4.29b | 4.38ab | 4.39ab | 0.01 | 0.156 |

| Lys* | 7.22bc | 7.02c | 7.10c | 7.36ab | 7.37ab | 7.40ab | 7.28ab | 7.43a | 7.26b | 0.02 | 0.026 |

| His*^ | 2.78b | 2.84ab | 2.83ab | 3.06ab | 2.96ab | 3.19a | 2.69b | 2.97ab | 3.14ab | 0.04 | 0.481 |

| Arg*^ | 5.37a | 5.20b | 5.23b | 5.32ab | 5.40a | 5.32ab | 5.29ab | 5.41a | 5.35ab | 0.02 | 0.033 |

| TAA | 77.55ab | 74.80b | 75.55b | 77.20ab | 78.00a | 77.73ab | 76.30b | 78.57a | 77.75ab | 0.19 | 0.004 |

| EAA | 43.58b | 42.42c | 42.95bc | 44.32a | 44.61a | 44.77a | 43.45bc | 44.66a | 44.20ab | 0.12 | 0.049 |

| FSAA | 38.01a | 36.30b | 36.49b | 36.99b | 37.67ab | 37.05b | 37.01b | 37.81ab | 37.51ab | 0.11 | 0.004 |

| BAA | 32.31b | 31.56b | 31.97b | 32.82ab | 32.95ab | 33.28a | 31.99b | 33.33a | 32.97ab | 0.10 | 0.039 |

| DAA | 70.32ab | 67.85b | 68.46b | 69.81ab | 70.62a | 70.32ab | 69.00b | 71.14a | 70.48ab | 0.17 | 0.003 |

| EAA/TAA | 56.20c | 56.71b | 56.85b | 57.41ab | 57.20ab | 57.60a | 56.94b | 56.84b | 56.85b | 0.06 | 0.130 |

| FSAA/TAA | 49.01a | 48.52ab | 48.30ab | 47.91b | 48.29b | 47.66b | 48.51ab | 48.12b | 48.24b | 0.08 | 0.331 |

| BAA/TAA | 41.66b | 42.18ab | 42.32ab | 42.52ab | 42.25ab | 42.81a | 41.92b | 42.42ab | 42.41ab | 0.08 | 0.410 |

In the first column, “*” mean EAA, “#” mean FSAA, “^” mean BAA, “#” add “^” mean DAA.

Data in the same line without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P < 0.01 as highly significant, P < 0.05 as significant).

Table 4b showed that Asp, Thr, Ser, Glu, Ala, Val, Ile, Tyr, Phe, Lys, and Arg were affected by the dietary ME level (P < 0.05). Glu and Tyr were significantly affected by dietary CP level (P < 0.05). TAA, EAA, BAA, DAA contents and the EAA/TAA ratio were the highest in 11.51 MJ/kg ME group and significantly higher than in the other 2 groups (P < 0.05); the FSAA/TAA ratio (48.61%) was the highest in 11.31 MJ/kg group (P < 0.05).

Table 4b.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on pectoral free amino acid content (dry matter basis) g/100 g.

| ME |

CP |

ME*CP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 11.51 | 11.71 | P-value | 14 | 15 | 16 | P-value | P-value | |

| Asp# | 7.47b | 7.62a | 7.57a | 0.017 | 7.55 | 7.57 | 7.54 | 0.773 | 0.018 |

| Thr*# | 3.57a | 3.48b | 3.54a | 0.017 | 3.52 | 3.55 | 3.53 | 0.442 | 0.002 |

| Ser# | 2.89a | 2.68b | 2.87a | 0.000 | 2.79 | 2.83 | 2.81 | 0.625 | 0.001 |

| Glu# | 11.37b | 11.72a | 11.67a | 0.000 | 11.69a | 11.60ab | 11.48b | 0.035 | 0.009 |

| Pro*# | 3.09 | 3.08 | 3.07 | 0.861 | 3.12 | 3.07 | 3.05 | 0.334 | 0.063 |

| Gly# | 3.84 | 3.86 | 3.88 | 0.872 | 3.91 | 3.84 | 3.83 | 0.454 | 0.069 |

| Ala# | 4.72b | 4.81a | 4.85a | 0.006 | 4.78 | 4.81 | 4.79 | 0.602 | 0.004 |

| Val*^ | 3.95c | 4.50a | 4.30b | 0.000 | 4.25 | 4.23 | 4.28 | 0.491 | 0.141 |

| Met*^ | 2.73a | 2.68b | 2.72ab | 0.053 | 2.69b | 2.74a | 2.70ab | 0.077 | 0.001 |

| Ile*^ | 3.77c | 4.19a | 4.07b | 0.000 | 4.01 | 4.00 | 4.02 | 0.869 | 0.072 |

| Leu*^ | 6.39 | 6.47 | 6.47 | 0.116 | 6.42 | 6.46 | 6.44 | 0.651 | 0.009 |

| Tyr^ | 2.74a | 2.38c | 2.59b | 0.000 | 2.51b | 2.61a | 2.59a | 0.011 | 0.000 |

| Phe*^ | 4.30b | 4.41a | 4.35ab | 0.016 | 4.34 | 4.34 | 4.38 | 0.433 | 0.156 |

| Lys* | 7.12b | 7.38a | 7.32a | 0.000 | 7.29 | 7.28 | 7.25 | 0.706 | 0.026 |

| His*^ | 2.82b | 3.07a | 2.93ab | 0.086 | 2.84 | 2.92 | 3.05 | 0.163 | 0.481 |

| Arg*^ | 5.27b | 5.35a | 5.35a | 0.056 | 5.33 | 5.34 | 5.30 | 0.584 | 0.033 |

| TAA | 75.97b | 77.64a | 77.54a | 0.002 | 77.02 | 77.12 | 77.01 | 0.963 | 0.004 |

| EAA | 42.99b | 44.57a | 44.10a | 0.001 | 43.79 | 43.90 | 43.98 | 0.803 | 0.049 |

| FSAA | 36.93 | 37.24 | 37.45 | 0.168 | 37.34 | 37.26 | 37.02 | 0.444 | 0.004 |

| BAA | 31.95b | 33.02a | 32.77a | 0.001 | 32.38 | 32.62 | 32.74 | 0.338 | 0.039 |

| DAA | 68.88b | 70.25a | 70.21a | 0.005 | 69.712 | 69.872 | 69.757 | 0.922 | 0.003 |

| EAA/TAA% | 56.58b | 57.40a | 56.88b | 0.000 | 56.85 | 56.91 | 57.10 | 0.178 | 0.130 |

| FSAA/TAA% | 48.61a | 47.95b | 48.29ab | 0.013 | 48.48 | 48.31 | 48.06 | 0.136 | 0.331 |

| BAA/TAA% | 42.05b | 42.52a | 42.25ab | 0.064 | 42.03b | 42.28ab | 42.51a | 0.059 | 0.410 |

In the first column, “*” mean EAA, “#” mean FSAA, “^” mean BAA, “#” add “^” mean DAA.

Data in the same line without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P < 0.01 as highly significant, P < 0.05 as significant).

Pectoral FA Composition

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, the pectoral FA mainly consisted of palmitic, oleic, linolenic, stearic, and arachidonic acids, with a total share of over 90% and a lower share of the remaining FA. Table 5a showed that there was a significant interaction of dietary ME and CP level on C20:3n6 (P = 0.046), and the highest content was in group with 11.31 MJ/kg ME and 15% CP; There had an influence trend for C20:1 and C20:2 (0.05 < P < 0.1). Table 5b showed that dietary ME level affected the C20:0 (P = 0.050), had an influence trend on C20:2 (P = 0.080); Dietary CP levels had an influence trend on C20:4n6 (P = 0.063). The interaction of ME and CP levels had an influence trend on C20:2 (P = 0.055).

Table 5a.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on proportion of pectoral free fatty acid content (dry matter basis) g/100 g.

| ME/(MJ/kg) | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.71 | 11.71 | 11.71 | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP/% | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

| C20:4n6345 | 0.425a | 0.360ab | 0.250b | 0.374ab | 0.344ab | 0.302ab | 0.372ab | 0.253b | 0.291ab | 0.018 | 0.647 |

| C14:01 | 0.020 | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.032 | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.030 | 0.028 | 0.003 | 0.754 |

| C14:12 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.935 |

| C15:01 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.860 |

| C16:01 | 0.740b | 1.171ab | 0.909ab | 1.471a | 0.846ab | 0.930ab | 1.038ab | 0.916ab | 1.179ab | 0.074 | 0.184 |

| C16:12 | 0.070 | 0.122 | 0.101 | 0.199 | 0.079 | 0.102 | 0.137 | 0.108 | 0.181 | 0.016 | 0.350 |

| C17:01 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.753 |

| C18:01 | 0.370b | 0.534a | 0.277b | 0.631a | 0.418ab | 0.440ab | 0.456ab | 0.399ab | 0.484ab | 0.028 | 0.163 |

| C18: 1n9c2 | 0.750b | 1.268ab | 0.999ab | 1.890a | 0.928ab | 1.082ab | 1.220ab | 0.994ab | 1.438ab | 0.112 | 0.232 |

| C18:2n6c345 | 0.600b | 0.910ab | 0.804ab | 1.085a | 0.755ab | 0.712ab | 0.934ab | 0.670ab | 0.788ab | 0.05 | 0.217 |

| C18:3n3346 | 0.015b | 0.029ab | 0.050a | 0.031ab | 0.029ab | 0.025ab | 0.030ab | 0.022ab | 0.027ab | 0.004 | 0.402 |

| C20:12 | 0.009b | 0.017ab | 0.012b | 0.024a | 0.009b | 0.011b | 0.014ab | 0.011b | 0.016ab | 0.001 | 0.072 |

| C20:23 | 0.011b | 0.016a | 0.014ab | 0.017a | 0.012ab | 0.012b | 0.013ab | 0.009b | 0.010b | 0.001 | 0.055 |

| C20:3n6345 | 0.031b | 0.044a | 0.029b | 0.039ab | 0.030b | 0.033ab | 0.037ab | 0.026b | 0.031b | 0.001 | 0.046 |

| C22:1n92 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.712 |

| C22:6n3346 | 0.048a | 0.035ab | 0.027b | 0.038ab | 0.036ab | 0.031ab | 0.036ab | 0.027b | 0.030ab | 0.002 | 0.751 |

| C23:01 | 0.000b | 0.001ab | 0.001ab | 0.004a | 0.002ab | 0.003ab | 0.002ab | 0.003ab | 0.004a | 0.001 | 0.384 |

| C24:12 | 0.006a | 0.006a | 0.004ab | 0.005ab | 0.004ab | 0.005ab | 0.005ab | 0.003b | 0.005ab | 0.001 | 0.286 |

| C18:1n9t2 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.446 |

| SFA | 1.131b | 1.745ab | 1.215b | 2.147a | 1.302ab | 1.402ab | 1.528ab | 1.357ab | 1.706ab | 0.102 | 0.181 |

| UFA | 1.979b | 2.822ab | 2.301ab | 3.721a | 2.243ab | 2.333ab | 2.815ab | 2.138ab | 2.835ab | 0.171 | 0.207 |

| MUFA | 0.846b | 1.428ab | 1.127ab | 2.138a | 1.038ab | 1.218ab | 1.393ab | 1.131ab | 1.658ab | 0.129 | 0.24 |

| PUFA | 1.133b | 1.394ab | 1.174ab | 1.583a | 1.205ab | 1.115b | 1.422ab | 1.007b | 1.177ab | 0.05 | 0.167 |

| EFA | 1.121b | 1.377ab | 1.160ab | 1.567a | 1.193ab | 1.103b | 1.409ab | 0.998b | 1.167ab | 0.05 | 0.171 |

| TFA | 3.110b | 4.567ab | 3.516ab | 5.868a | 3.545ab | 3.735ab | 4.343ab | 3.494ab | 4.541ab | 0.273 | 0.199 |

| n6PUFA | 1.059b | 1.313ab | 1.083ab | 1.498a | 1.128ab | 1.047b | 1.344ab | 0.949b | 1.110ab | 0.048 | 0.164 |

| n3PUFA | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.078 | 0.069 | 0.064 | 0.056 | 0.065 | 0.048 | 0.057 | 0.004 | 0.753 |

| n6/n3 | 16.969 | 20.456 | 18.106 | 21.409 | 17.931 | 19.174 | 21.024 | 19.917 | 19.588 | 0.795 | 0.699 |

| PUFA/SFA | 1.023a | 0.823ab | 0.986ab | 0.785ab | 0.965ab | 0.818ab | 0.938ab | 0.761b | 0.708b | 0.029 | 0.150 |

Data in the first column: the letters superscripts “1” means SFA, “2” means MFA, “3” means PUFA, “4” means EFA, “5” means n6PUFA, “6” means n3PUFA, “2” add “3” means UFA.

Data in the same line without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P>0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P<0.01 as highly significant, P<0.05 as significant).

Table 6a.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on pectoral fatty acid proportion (dry matter basis)%.

| ME, MJ/kg | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.31 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.51 | 11.71 | 11.71 | 11.71 | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP, % | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

| C20:4n6345 | 14.30a | 8.37ab | 7.35b | 7.96b | 10.45ab | 8.32ab | 8.75ab | 7.70b | 6.70b | 0.71 | 0.351 |

| C14:01 | 0.52b | 0.55ab | 0.65ab | 0.52ab | 0.64ab | 0.55ab | 0.54ab | 0.80a | 0.60ab | 0.03 | 0.572 |

| C14:12 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.618 |

| C15:01 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.978 |

| C16:01 | 23.70b | 25.47ab | 26.85a | 24.63ab | 23.44b | 24.67ab | 23.86b | 26.29ab | 25.85ab | 0.28 | 0.204 |

| C16:12 | 2.17b | 2.72ab | 2.94ab | 2.95ab | 2.11b | 2.59ab | 3.11ab | 3.04ab | 3.87a | 0.19 | 0.717 |

| C17:01 | 0.14ab | 0.12ab | 0.07ab | 0.12ab | 0.24a | 0.16ab | 0.13ab | 0.06b | 0.13ab | 0.02 | 0.492 |

| C18:01 | 12.00a | 11.68a | 7.32ab | 11.25ab | 11.90a | 11.90a | 10.54ab | 11.64a | 10.70ab | 0.45 | 0.288 |

| C18: 1n9c2 | 23.33b | 26.93ab | 29.17ab | 30.50a | 25.12ab | 28.35ab | 27.95ab | 28.49ab | 30.96a | 0.80 | 0.395 |

| C18:2n6c345 | 19.44b | 19.95ab | 23.51a | 18.42b | 21.33ab | 19.55ab | 21.48ab | 19.40b | 17.62b | 0.45 | 0.049 |

| C18:3n3346 | 0.47b | 0.60b | 1.38a | 0.49b | 0.84ab | 0.66b | 0.69ab | 0.60b | 0.59b | 0.08 | 0.20 |

| C20:12 | 0.28ab | 0.34ab | 0.34ab | 0.41a | 0.26b | 0.30ab | 0.31ab | 0.33ab | 0.35ab | 0.02 | 0.256 |

| C20:23 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.868 |

| C20:3n6345 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.924 |

| C22:1n92 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.422 |

| C22:6n3346 | 1.60a | 0.84b | 0.78b | 0.83b | 1.10ab | 0.84b | 0.84b | 0.81b | 0.69b | 0.08 | 0.277 |

| C23:01 | 0.00b | 0.02ab | 0.05ab | 0.09ab | 0.07ab | 0.06ab | 0.03ab | 0.08ab | 0.09a | 0.01 | 0.68 |

| C24:12 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.608 |

| C18:1n9t2 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.931 |

| SFA | 36.39b | 37.98ab | 35.02b | 36.63b | 36.36b | 37.42ab | 35.18b | 39.00a | 37.47ab | 0.25 | 0.032 |

| UFA | 63.67b | 61.72b | 67.24a | 63.12b | 63.04b | 62.44b | 64.82ab | 61.90b | 62.23b | 0.34 | 0.023 |

| MUFA | 26.44b | 30.54ab | 32.92ab | 34.30ab | 28.09ab | 31.84ab | 31.88ab | 32.33ab | 35.67a | 0.96 | 0.437 |

| PUFA | 37.22a | 31.18ab | 34.31ab | 28.82ab | 34.95ab | 30.61ab | 32.93ab | 29.57ab | 26.55b | 1.01 | 0.291 |

| EFA | 36.85a | 30.81ab | 33.90ab | 28.50ab | 34.58ab | 30.25ab | 32.62ab | 29.30ab | 26.32b | 0.99 | 0.283 |

| n6PUFA | 34.78a | 29.37ab | 31.74 ab | 27.17 ab | 32.65 ab | 28.76 ab | 31.09ab | 27.89 ab | 25.04b | 0.941 | 0.330 |

| n3PUFA | 2.07 | 1.44 | 2.16 | 1.33 | 1.94 | 1.50 | 1.53 | 1.41 | 1.28 | 0.107 | 0.314 |

Data in the first column: the letters superscripts “1” means SFA, “2” means MFA, “3” means PUFA, “4” means EFA, “5” means n6PUFA, “6” means n3PUFA, “2” add “3” means UFA.

Data in the same line without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P>0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P<0.01 as highly significant, P<0.05 as significant).

Table 5b.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on pectoral free fatty acid content (dry matter basis) g/100 g.

| ME |

CP |

ME × CP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 11.51 | 11.71 | P-value | 14 | 15 | 16 | P-value | P-value | |

| C20:4n6345 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.620 | 0.39a | 0.32ab | 0.28b | 0.063 | 0.647 |

| C14:01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.640 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.853 | 0.754 |

| C14:12 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.500 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.836 | 0.935 |

| C15:01 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.700 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.452 | 0.860 |

| C16:01 | 0.94 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 0.720 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.839 | 0.184 |

| C16:12 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.510 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.676 | 0.350 |

| C17:01 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.490 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.902 | 0.753 |

| C18:01 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.360 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.471 | 0.163 |

| C18: 1n9c2 | 1.00 | 1.30 | 1.22 | 0.550 | 1.29 | 1.06 | 1.17 | 0.725 | 0.232 |

| C18:2n6c345 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.810 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.647 | 0.217 |

| C18:3n3346 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.850 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.607 | 0.402 |

| C20:12 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.750 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.572 | 0.072 |

| C20:23 | 0.01a | 0.01ab | 0.01b | 0.080 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.470 | 0.055 |

| C20:3n6345 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.560 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.394 | 0.046 |

| C22:1n92 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.800 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.693 | 0.712 |

| C22:6n3346 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.540 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.134 | 0.751 |

| C23:01 | 0.001b | 0.003a | 0.003ab | 0.050 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.796 | 0.384 |

| C24:12 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.260 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.609 | 0.286 |

| C18:1n9t2 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.640 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.976 | 0.446 |

| SFA | 1.36 | 1.62 | 1.53 | 0.600 | 1.60 | 1.47 | 1.44 | 0.791 | 0.181 |

| UFA | 2.37 | 2.77 | 2.60 | 0.640 | 2.84 | 2.40 | 2.49 | 0.555 | 0.207 |

| MUFA | 1.13 | 1.46 | 1.40 | 0.560 | 1.46 | 1.20 | 1.33 | 0.717 | 0.240 |

| PUFA | 1.23 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 0.720 | 1.38 | 1.20 | 1.15 | 0.186 | 0.167 |

| EFA | 1.22 | 1.29 | 1.19 | 0.730 | 1.37 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 0.186 | 0.171 |

| TFA | 3.73 | 4.38 | 4.13 | 0.630 | 4.44 | 3.87 | 3.93 | 0.650 | 0.199 |

| n6PUFA | 1.15 | 1.22 | 1.13 | 0.730 | 1.30 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 0.176 | 0.164 |

| n3PUFA | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.560 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.800 | 0.753 |

| n6/n3 | 18.51 | 19.50 | 20.18 | 0.700 | 19.80 | 19.43 | 18.96 | 0.910 | 0.699 |

| PUFA/SFA | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.170 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.516 | 0.150 |

Data in the first column: the letters superscripts “1” means SFA, “2” means MFA, “3” means PUFA, “4” means EFA, “5” means n6PUFA, “6” means n3PUFA, “2” add “3” means UFA.

Data in the same line without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P < 0.01 as highly significant, P < 0.05 as significant).

Table 6a showed that C18:2n6c, SFA and UFA were significantly affected by the interaction of dietary ME and CP levels (P < 0.05). Table 6b showed that dietary CP level affected SFA percentage (P < 0.05), and had an influence on C16:0 and UFA content (0.05 < P < 0.01).

Table 6b.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on the proportion of pectoral fatty acid contents (dry matter basis)%.

| ME |

CP |

ME × CP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 11.51 | 11.71 | P-value | 14 | 15 | 16 | P-value | P-value | |

| C20:4n6345 | 10.008 | 8.909 | 7.713 | 0.435 | 10.338 | 8.839 | 7.453 | 0.278 | 0.351 |

| C14:01 | 0.576 | 0.567 | 0.646 | 0.543 | 0.522 | 0.663 | 0.602 | 0.212 | 0.572 |

| C14:12 | 0.142 | 0.171 | 0.143 | 0.741 | 0.157 | 0.141 | 0.159 | 0.899 | 0.618 |

| C15:01 | 0.080 | 0.061 | 0.107 | 0.596 | 0.049 | 0.109 | 0.090 | 0.403 | 0.978 |

| C16:01 | 25.339 | 24.247 | 25.332 | 0.224 | 24.064b | 25.064ab | 25.789a | 0.070 | 0.204 |

| C16:12 | 2.61 | 2.553 | 3.34 | 0.192 | 2.743 | 2.627 | 3.133 | 0.527 | 0.717 |

| C17:01 | 0.112 | 0.174 | 0.104 | 0.355 | 0.130 | 0.142 | 0.119 | 0.904 | 0.492 |

| C18:01 | 10.333 | 11.687 | 10.96 | 0.477 | 11.264 | 11.742 | 9.973 | 0.270 | 0.288 |

| C18: 1n9c2 | 26.479 | 27.988 | 29.132 | 0.416 | 27.259 | 26.846 | 29.494 | 0.368 | 0.395 |

| C18:2n6c345 | 20.966 | 19.763 | 19.501 | 0.382 | 19.781 | 20.224 | 20.224 | 0.897 | 0.049 |

| C18:3n3346 | 0.816 | 0.662 | 0.622 | 0.592 | 0.549 | 0.676 | 0.876 | 0.271 | 0.200 |

| C20:12 | 0.322 | 0.322 | 0.330 | 0.974 | 0.334 | 0.310 | 0.330 | 0.801 | 0.256 |

| C20:23 | 0.383a | 0.347ab | 0.273b | 0.123 | 0.334 | 0.336 | 0.333 | 0.999 | 0.868 |

| C20:3n6345 | 0.993 | 0.852 | 0.790 | 0.339 | 0.899 | 0.906 | 0.831 | 0.837 | 0.924 |

| C22:1n92 | 0.110 | 0.112 | 0.078 | 0.603 | 0.120 | 0.102 | 0.078 | 0.545 | 0.422 |

| C22:6n3346 | 1.071 | 0.923 | 0.782 | 0.362 | 1.092 | 0.916 | 0.769 | 0.284 | 0.277 |

| C23:01 | 0.023 | 0.072 | 0.070 | 0.127 | 0.040 | 0.058 | 0.068 | 0.558 | 0.680 |

| C24:12 | 0.156 | 0.112 | 0.103 | 0.184 | 0.131 | 0.121 | 0.119 | 0.904 | 0.608 |

| C18:1n9t2 | 0.151 | 0.151 | 0.167 | 0.831 | 0.136 | 0.169 | 0.164 | 0.483 | 0.931 |

| SFA | 36.462 | 36.808 | 37.219 | 0.489 | 36.070b | 37.780a | 36.639ab | 0.038 | 0.032 |

| UFA | 64.207 | 62.869 | 62.981 | 0.229 | 63.868ab | 62.218b | 63.971a | 0.086 | 0.023 |

| MUFA | 29.968 | 31.411 | 33.294 | 0.382 | 30.878 | 30.318 | 33.478 | 0.374 | 0.437 |

| PUFA | 34.239 | 31.457 | 29.688 | 0.205 | 32.991 | 31.901 | 30.491 | 0.605 | 0.291 |

| EFA | 33.853 | 31.112 | 29.412 | 0.208 | 32.657 | 31.564 | 30.157 | 0.594 | 0.283 |

| n6PUFA | 31.966 | 29.526 | 28.005 | 0.249 | 31.015 | 29.970 | 28.513 | 0.562 | 0.330 |

| n3PUFA | 1.889 | 1.586 | 1.406 | 0.207 | 1.642 | 1.595 | 1.644 | 0.978 | 0.314 |

Data in the first column: the letters superscripts “1” means SFA, “2” means MFA, “3” means PUFA, “4” means EFA, “5” means n6PUFA, “6” means n3PUFA, “2” add “3” means UFA.

Data in the same line without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P>0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P<0.01 as highly significant, P<0.05 as significant).

Alpha Diversity

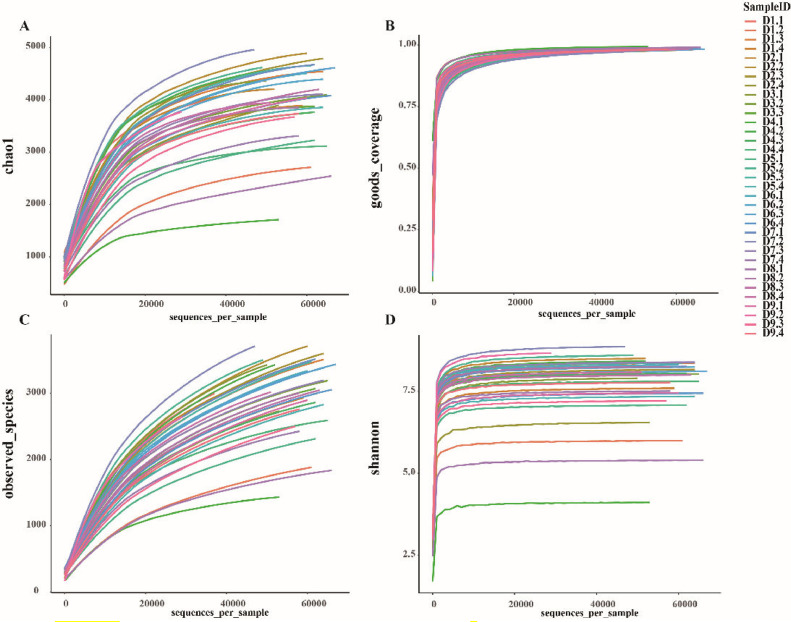

As seen from Figure 1(A), all rarefraction curves of Chao1 were close to the maximum value of OTU contained in all samples, but the community richness showed some differences among samples, and the rising trend of each sample curve gradually flattened out and approaches a plateau, indicating that the amount of sequencing data of the samples was reasonable and reliable. The Good_Coverage of all samples in Figure 1(B) were close to 100%, which confirmed the reliability of the data. The rarefraction curve was shown as the number of OTUs constructed at different sampling depths. The curve provided an initial assessment of sequencing saturation, with the final curve leveling off as shown in Figure 1 (C), representing sufficient saturation of the current sequencing volume. At the same time, the Shannon of the sequenced samples was analyzed to construct a rarefraction curve, and the results were shown in Figure 1(D). It could be seen from Figure 1(D), all curves of the Shannon had a rapid rising process and then flatten out to a steady state, which indicated that the amount of sequencing data of the samples was sufficient for effective subsequent analysis.

Figure 1.

Alpha Index Rarefraction Curve Graph. Figure A is Chao1, B is Goods_Coverage, C is Observed and D is Shannon, showing the saturation of sequencing and the differences between samples (different Y-axis coordinates, that is, the Alpha diversity varies greatly). As well as the large differences between each sample (each line in the graph represents one sample).

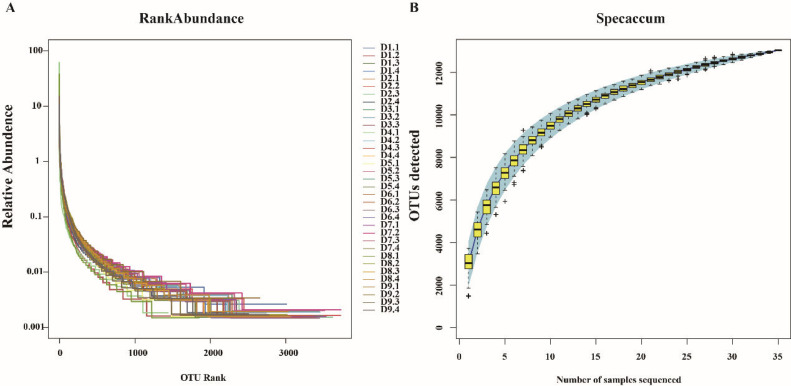

As shown in Figure 2(A), the Rank Abundance curves for each group were wider and gradually flatter, indicating a richer and more homogeneous species composition for all samples. In Figure 2(B) the curves in the sample curves flatten out with increasing sample size, indicating that the species in each group did not increase significantly with increasing sample size, indicating that the groups were adequately sampled.

Figure 2.

Rank-abundance curve and Specaccum species accumulation curve, Figure A is Rank-abundance, Figure B is Specaccum.

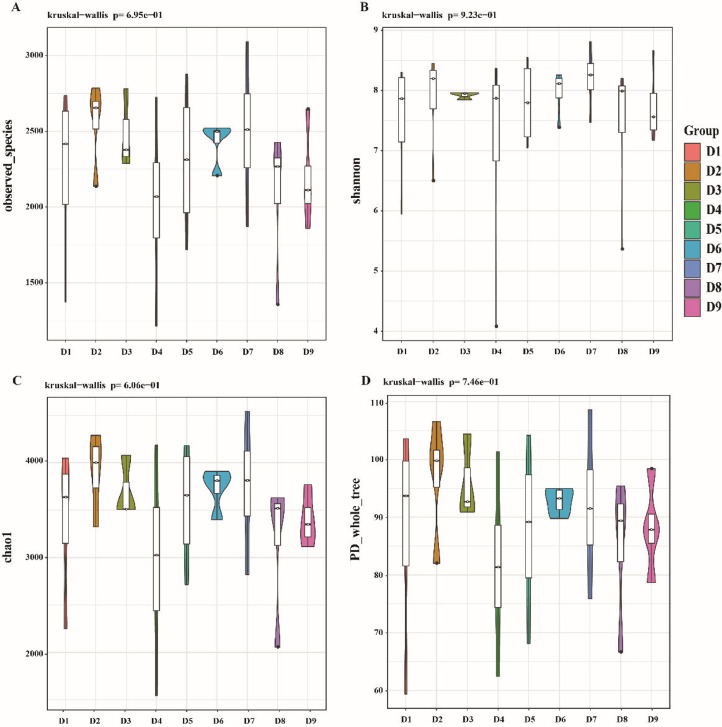

As shown in Table 7 and Figure 3, the Chao1, Observed species, and PD_whole_tree indices were higher than the rest of the groups at 11.31 MJ/kg and 15% CP group, but the difference was not significant (P > 0.05).

Table 7.

Effect of dietary ME and CP levels on the alpha diversity of gut microbiota.

| ME,MJ/kg | CP, % | goods _coverage | chao1 | observed_species | Shannon | PD_whole_tree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 14.0 | 96.71 | 3,392.23 | 2,235.58 | 7.49 | 87.59 | ||

| 11.31 | 15.0 | 96.17 | 3,902.84 | 2,557.70 | 7.84 | 97.03 | ||

| 11.31 | 16.0 | 96.32 | 3,698.12 | 2,482.40 | 7.92 | 95.98 | ||

| 11.51 | 14.0 | 97.23 | 2,944.02 | 2,018.78 | 7.05 | 81.62 | ||

| 11.51 | 15.0 | 96.55 | 3,550.55 | 2,305.25 | 7.80 | 87.65 | ||

| 11.51 | 16.0 | 96.36 | 3,731.72 | 2,431.03 | 7.97 | 92.82 | ||

| 11.71 | 14.0 | 96.42 | 3,745.85 | 2,495.85 | 8.20 | 91.88 | ||

| 11.71 | 15.0 | 96.92 | 3,180.32 | 2,079.45 | 7.39 | 85.22 | ||

| 11.71 | 16.0 | 96.71 | 3,395.64 | 2,182.15 | 7.74 | 88.18 | ||

| SEM | 0.116 | 112.322 | 77.236 | 0.175 | 2.122 | |||

| ME | 11.31 | 96.40 | 3,664.39 | 2,425.23 | 7.75 | 93.54 | ||

| 11.51 | 96.71 | 3,408.76 | 2,251.68 | 7.60 | 87.36 | |||

| 11.71 | 96.68 | 3,440.60 | 2,252.48 | 7.78 | 88.43 | |||

| P-value | 0.501 | 0.615 | 0.59 | 0.909 | 0.457 | |||

| CP | 14.0 | 96.79 | 3,360.70 | 2,250.07 | 7.58 | 87.03 | ||

| 15.0 | 96.54 | 3,544.57 | 2,314.13 | 7.67 | 89.97 | |||

| 16.0 | 96.46 | 3,608.49 | 2365.19 | 7.87 | 92.33 | |||

| P-value | 0.503 | 0.65 | 0.833 | 0.789 | 0.599 | |||

| ME × CP | P-value | 0.363 | 0.326 | 0.394 | 0.58 | 0.67 | ||

Data in the same column without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P>0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P<0.01 as highly significant, P<0.05 as significant).

Figure 3.

Comparison of OTU diversity indices between groups violin plot, Fig. A is Observed species, Fig. B is Shannon index represent the diversity of microflora in the samples tested, Fig. C is Chao1 index to measure species richness, Fig. D is PD_whole tree. The violin plot shows the degree of sample dispersion within groups and the difference in the level of indices between groups.

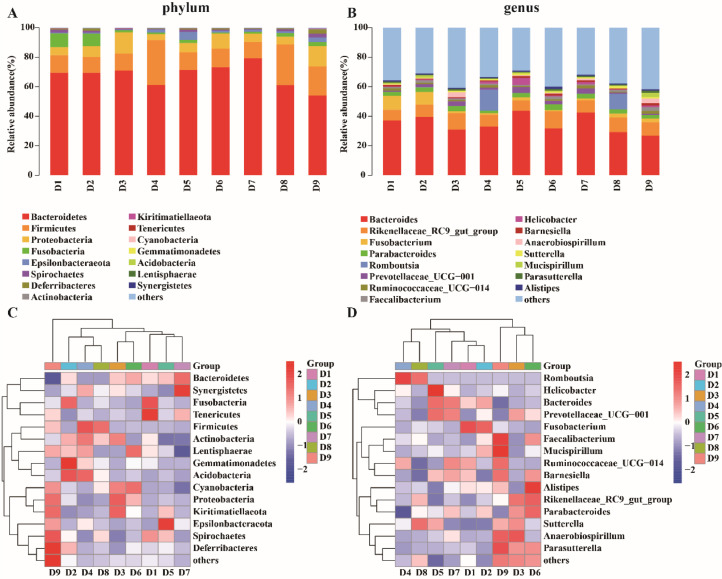

Intestinal Flora Community

Figure 4(A)(C) showed the composition of microbiota in the cecum of chickens at the phylum level. The composition of Top 15 phyla was approximately equal in each group, and the top 3 dominant phyla of most groups were Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria. The third dominant phylum at the ME level of Fusobacteria replaced Proteobacteria as the third dominant phylum in the two groups with ME level of 11.31 MJ/kg and CP levels of 14% and 15%. The relative abundance of Proteobacteria increased with dietary CP level.

Figure 4.

Relative abundance of gut microbial at phylum level and genus level, A and C show the histogram and clustering heat map at the phylum level, B and D show the histogram and clustering heat map at the genus level, showing the Top15 phyla and genus respectively.

The relative abundance of the main microbial phyla for each sample was statistically analyzed, and the results were shown in Table 8. Firmicutes showed a significant difference by the interaction of ME and CP levels (P < 0.05), the group with 11.51 MJ/kg ME and 14% CP had the highest abundance (31.42%). The abundance of Proteobacteria was significantly affected by dietary CP levels (P < 0.01) and increased with the dietary CP levels, got the maximum value at 16% CP group (12.68%) (P < 0.05).

Table 8.

Relative abundance of dietary ME and CP levels at the phylum level of the gut microbiota (%).

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % | Bacteroidetes | Firmicutes | Proteobacteria | Fusobacteria | Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 14.0 | 69.18 | 11.85b | 6.08b | 9.17 | 0.166b |

| 11.31 | 15.0 | 69.04 | 10.59b | 7.15ab | 9.05 | 0.150b |

| 11.31 | 16.0 | 70.33 | 11.55b | 14.90a | 1.49 | 0.173b |

| 11.51 | 14.0 | 60.10 | 31.42a | 4.01b | 1.12 | 1.029a |

| 11.51 | 15.0 | 71.77 | 12.03b | 6.10b | 1.99 | 0.178b |

| 11.51 | 16.0 | 73.35 | 12.45b | 10.30ab | 0.76 | 0.177b |

| 11.71 | 14.0 | 79.25 | 11.01b | 5.66b | 1.16 | 0.142b |

| 11.71 | 15.0 | 61.86 | 26.81ab | 5.12b | 2.52 | 0.543ab |

| 11.71 | 16.0 | 56.05 | 19.74ab | 12.83ab | 2.28 | 0.362ab |

| SEM | 2.41 | 1.93 | 0.921 | 1.23 | 0.095 | |

| ME | 11.31 | 69.52 | 11.33 | 9.38 | 6.57 | 0.163 |

| 11.51 | 68.41 | 18.63 | 6.80 | 1.29 | 0.461 | |

| 11.71 | 65.72 | 19.18 | 7.87 | 1.99 | 0.349 | |

| P-value | 0.809 | 0.199 | 0.521 | 0.177 | 0.454 | |

| CP | 14.0 | 69.51 | 18.09 | 5.25b | 3.82 | 0.446 |

| 15.0 | 67.56 | 16.47 | 6.12b | 4.52 | 0.29 | |

| 16.0 | 66.58 | 14.58 | 12.68a | 1.51 | 0.237 | |

| P-value | 0.884 | 0.758 | 0.005 | 0.578 | 0.653 | |

| ME × CP | P-value | 0.149 | 0.046 | 0.952 | 0.769 | 0.213 |

Data in the same column without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P>0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P<0.01 as highly significant, P<0.05 as significant).

Figure 4(B)(D) showed the composition of gut microbiota at the genus level in each treatment group. The main dominant genus in each treatment group was Bacreroides, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group, Fusobacterium, Parabacteroides, but Romboutsia was the dominant genus in D4 and D8.

Table 9 indicated the relative abundance statistics at the genus level of gut microbiota for each group. It was found that the ME and CP levels of the diets did not affect the genus of top4 (P > 0.05). In contrast, the abundance of Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group and Parabacteroides showed a gradual increase with the increasing dietary CP level, and both obtained maximum abundance at 16% CP level (10.62%, 3.38%).

Table 9.

Relative abundance of dietary ME and CP levels at the genus level of the gut microbiota (%).

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % | Bacteroides | Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group | Fusobacterium | Parabacteroides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.31 | 14.0 | 35.65ab | 7.40 | 9.17 | 2.53ab |

| 11.31 | 15.0 | 39.15ab | 8.23 | 9.05 | 3.19ab |

| 11.31 | 16.0 | 30.23ab | 11.31 | 1.49 | 3.66ab |

| 11.51 | 14.0 | 31.87ab | 8.14 | 1.12 | 1.73b |

| 11.51 | 15.0 | 43.65a | 7.14 | 1.98 | 2.92ab |

| 11.51 | 16.0 | 31.75ab | 11.67 | 0.76 | 3.92a |

| 11.71 | 14.0 | 42.28ab | 8.44 | 1.16 | 3.24ab |

| 11.71 | 15.0 | 29.57ab | 10.15 | 2.52 | 3.02ab |

| 11.71 | 16.0 | 27.64b | 8.89 | 2.27 | 2.55ab |

| SEM | 1.82 | 0.63 | 1.23 | 0.21 | |

| ME | 11.31 | 35.01 | 8.98 | 6.57 | 3.13 |

| 11.51 | 35.75 | 8.98 | 1.29 | 2.86 | |

| 11.71 | 33.16 | 9.16 | 1.98 | 2.94 | |

| P-value | 0.83 | 0.991 | 0.177 | 0.885 | |

| CP | 14.0 | 36.60 | 7.99 | 3.82 | 2.50 |

| 15.0 | 37.45 | 8.51 | 4.52 | 3.04 | |

| 16.0 | 29.87 | 10.62 | 1.51 | 3.38 | |

| P-value | 0.195 | 0.222 | 0.578 | 0.303 | |

| ME × CP | P-value | 0.256 | 0.599 | 0.769 | 0.339 |

Data in the same column without letters or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P>0.05), different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P<0.01 as highly significant, P<0.05 as significant).

From the above results, it was found that the top three dominant phyla in each group were Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, and the composition of all phyla tended to be stable. The abundance of Proteobacteria was significantly affected by dietary CP levels (P < 0.01), and the abundance of Proteobacteria increased with the dietary CP levels.

DISCUSSION

Dietary ME and CP are two of the most critical nutritional parameters and have important impacts on growth and development of poultry (Mir et al., 2017). One study in Mexican Creole birds showed that the males with 10.67 MJ/kg diet had a high performance, without compromising carcass yield and body composition (Matus-Aragón et al., 2022). Reducing dietary CP levels did not affect the growth performance of broiler chickens (Chrystal et al., 2020), and the high ME level tended to increase body weight and daily gain and reduce feed conversion ratio of yellow-feathered male chickens (Abouelezz et al., 2019). Our group compared the performance of BYC laying hens with 3 levels of CP (16.0%, 15.5%, and 15.0%), and suggested that the egg laying rate was not significantly affected by CP levels at 19 to 55 wks of age (Geng et al., 2011). In this study, dietary ME and CP levels did not affect performance of growing chickens, but the mortality rate of 11.31 MJ/kg was the highest, probably because the 11.31 MJ/kg ME was not enough to build up the chicken's resistance.

The pectoral muscle composition is directly related to its nutritional characteristics and is a concrete expression of its nutritional value, flavor, juiciness and other traits. Pectoral nutritional indicators mainly include CP, CF, and water content (Zhang et al., 2021). The CP content is an important reflection of the nutritional value of breast meat (Irm et al., 2020), while CF is also one of the important indicators of meat quality. Proper intramuscular fat can improve the tenderness and flavor of breast meat (Aaslyng et al., 2017).

It has been found that the pectoral CP content decreased significantly and the CF content increased significantly with the increase of ME level (Peter et al., 1998). The growth rate of the BYC was slow, the pectoral CP content was the lowest and the CF content was the highest when the dietary ME level was 11.51 MJ/kg, which was similar to the study of yellow-feathered broilers from 22 to 42 d of age (Zhou et al., 2004). Ferreira et al. (2015) found that pectoral CF content of broiler appeared lower after feeding diets with lower ME levels. When ME level increased, the pectoral CF content also increased in AA broilers (Fang et al., 2002), which was similar to the present results.

Proper pectoral fat is important to maintain good palatability and flavor, but meat quality decreases when fat content exceeds a certain range, and meat with higher fat content is not always popular with consumers (Chen et al., 2008). Pectoral CF is also linked to tenderness and flavor, and moderate fat deposition can lead to juicier, tastier chicken products (Glitsch, 2000; Hocquette et al., 2010). In this study, the pectoral CF content showed a trend of increasing and then decreasing with the increase of ME level, which may be related to the CP level, at low CP levels, the CF content increased and then decreased with the increase of ME levels. The pectoral CF increased gradually with increasing ME level at 16% CP. This indicates that a certain amount of protein is beneficial for promoting the growth of breast, but excess protein is deposited as body fat, suggesting that the maximum protein utilization can be obtained at 15% CP, which is in agreement with the findings of Fang et al. (2002).

Poultry have the characteristic of “eating for energy” (Hossain et al., 2012), and there is a dynamic equilibrium between the energy conversion rate and protein conversion rate in the body (Marcu et al., 2012). In this experiment, the pectoral CP and CF contents were in dynamic equilibrium, with one indicator increasing and the other decreasing, the higher dietary CP levels may result in deposition of body fat, therefore, it is not recommended to have a higher dietary CP to avoid protein waste. Especially in the context of the worldwide shortage of protein resources, appropriate reduction of dietary CP level can not only make greater use of limited resources, but also reduce the nitrogen content excreted from chicken manure, which is of great significance to reduce environmental pollution.

FAA is one of the important taste substances and aroma precursors of chicken meat, many of which have sweet, sour, salty, fresh and other flavors. Among them the content of amino acids with taste function has a significant impact on muscle flavor (del Olmo et al., 2015; Qi et al., 2017; Diez-Simon et al., 2019). The present study showed that dietary ME and CP levels affected the FAA, not only some amino acids content but also amino acid types, especially the flavoring amino acids. Dietary ME level significantly affected TAA and EAA content, with 11.71 MJ/kg ME group having a higher TAA and EAA content, while dietary CP level did not differ, suggesting that an increase in dietary ME level could significantly increase the TAA and EAA content. About flavoring amino acids, higher dietary ME levels increased the content of flavoring amino acids and the content of FSAA and BAA. However, we found that the proportion of EAA, FSAA, and BAA in TAA, with the increase of dietary ME level, FSAA content in the low ME group accounted for the largest proportion, and the smallest proportion of BAA, while the proportion of EAA showed a trend of rising first and then declining, indicating that a tasty chicken meat can be obtained at a moderate ME level.

Dietary CP levels affected the Glu content, which was one of the fresh flavor substances (Kurihara., 2009), and at the 14% CP level, BAA accounted for a relatively small proportion of the total FAA and a higher proportion of FSAA.

Fatty acids are important chemical substances that make up fats and are part of tissue cells that determine the physicochemical properties of fats and influence the flavor of meat (Diez-Simon et al., 2019; Zhan et al., 2022). Among them, UFA contribute considerably to human health and can inhibit the development of many diseases by increasing n−3 PUFA content of food (i.e., reducing the n−6/n−3 PUFA ratio) (Kouba et al., 2003; Theodoratou et al., 2007; Simopoulos., 2008). The FA composition of the bird can be directly regulated by nutritional level of the diet (Wood et al., 2004; Simopoulos, 2006; Wood et al., 2008; Kouba et al., 2011). Diet-regulated chicken meat can be an important source of PUFA (especially n−3 PUFA) for human health (Howe et al., 2006). Jahan et al. (2005) found a correlation between α-tocopherol, PUFA, ω-3 FA content and flavor abundance in cooked chicken meat, with PUFA and α-tocopherol content strongly correlated with total flavor abundance

This study showed that the dietary ME and CP levels affect the pectoral FA composition, especially PUFA. In the group with 11.51 MJ/kg ME and 14% CP, the TFA content was increased, which had an impact on each FA content, with a significant increase in PUFA content, which is a determinant of flavor. In contrast, the highest PUFA content group had higher values for both n−6 PUFA and n−3 PUFA, but also had the highest value for n−6/n−3, indicating that the increase in n−6 PUFA content was much higher than that of n−3 PUFA under this condition.

In this study, the pectoral n−6 PUFA content increased and then decreased with increasing ME level, while the n−3 PUFA content continued to decrease. The reason may be due to the competition between n−3 PUFA and n−6 PUFA (Woods et al., 2009). Increasing n−3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid content did not increase n−6 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid content at the same time (Schmitz and Ecker, 2008). In this study the healthiness of chicken meat may gradually decrease with the increasing nutrition level, while higher ME could increase the PUFA content of flavor substance. This further supports that higher flavor chicken meats can be obtained at moderate ME levels and CP level. Yang. (2001) studied the effects of dietary ME and CP levels on Hetian chickens and found that, when fed diets with high ME levels, the pectoral SFA and MFA contents increased significantly, while PUMA content decreased, and when fed diets with high CP level, the PUFA content increased and the SFA and MUFA content decreased, which was similar to the results of this study. Yang (2001) found that the pectoral muscle had the highest PUFA content in the group with 11.93 MJ/kg ME and 14.5% CP (energy protein ratio was 0.823), while the group with 11.51 MJ/kg ME and 14% CP had the closest energy protein ratio (0.822) in this present study.

The diversity of the gut microbiota and the number of dominant microbiota are important to improve the immunity of the organism and improving intestinal health. In adult chickens, the phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria were found to be the dominant phyla in the gut microbiota (Oakley et al., 2014), Their abundance accounted for more than 90% of the total sequences (Wei et al., 2013), with Firmicutes accounting for 70%, Bacteroidetes 12.3%, and Proteobacteria 9.3%. This study showed that the dominant phyla for each group was Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, which was consistent with Oakley et al. (2014).

The gut microbiota consists mainly of two dominant phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (Qin et al., 2010; Lei et al., 2022). Bacteroidetes are associated with carbohydrate metabolism in the body, breaking down sugars to produce volatile fatty acid, which are absorbed and utilized by the intestine (Lozupone et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2015). Firmicutes help the host absorb energy from the diet, effectively promoting calorie absorption as well as weight gain (Ley et al., 2006; De Filippo et al., 2010; Krajmalnik et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2020). The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) values are closely associated with obesity (De Bandt et al., 2011; Koliada et al., 2017; Zou et al., 2020). The ability of the Bacteroidetes to promote nutrient absorption and the Firmicutes to inhibit nutrient absorption in chicken intestines explains the relationship between Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes and growth (Islam et al., 2019; Magne et al., 2020). In this study, the abundance of Bacteroidetes continued to decrease with increasing dietary ME levels and CP levels, while the abundance of Firmicutes didn't increase, the F/B value increased relatively, and there was a tendency for the growing chickens to become obese. This suggests that a higher ME level and CP level can affect energy absorption by altering the F/B value in the gut microbiota, which was consistent with that in humans (Dong et al., 2020).

Proteobacteria are the largest phylum of bacteria and include many pathogenic bacteria (Rizzatti et al., 2017), whereas the abundance of the Proteobacteria is associated with obesity (Zhang et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2013) and diabetes (Geurts et al., 2011; Karlsson et al., 2013). Its increased abundance often represents an imbalance in the composition of the gut microbiota (Shin et al., 2015) and brings about metabolic disorders (Fei et al., 2013; Suez et al., 2014). The increasing dietary CP level increase the abundance of Proteobacteria in this study. Experiments in the mouse also confirmed that with the increase of Proteobacteria abundance, the energy imbalance and unstable microbiota increased in the host (Shin et al., 2015). Majority of microorganisms in gut microbiota are obligate anaerobe, but members of the Proteobacteria are facultative anaerobe. This unique oxygen requirement of the Proteobacteria may affect the relationship between the abundance of the Proteobacteria and the oxygen homeostasis or concentration in the gut microbiota (Litvak et al., 2017). In contrast, Proteobacteria is more abundant in the gut of dogs and cats fed a high-protein diets (Moon et al., 2018). Therefore, excessive dietary CP may lead to a certain degree of imbalance in the gut microbiota, which in turn may affect health.

Bacteroides promote the maturation of the immune system, but also facilitate the absorption of UFA, accelerate fat deposition and regulate the structure and function of gut microbiota through nutritional intervention. This explains why Bacteroides is the dominant genus (Oh et al., 2016). The present study found that the relative abundance of the Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group increased with increasing ME and CP levels, which is consistent with Ahmad et al. (2020) on rumen microbial diversity in yaks. The relative abundance of Fusobacterium tended to decrease with increasing ME and CP levels, whereas the abundance of Parabacteroides indicated a gradual increase with increasing dietary CP level, and a decreasing trend with increasing dietary ME level. The Parabacteroides and its strains have been shown to be negatively associated with obesity, and high protein diets could improve lipid metabolism and have a preventive effect on obesity brought about by diet (Wu et al., 2019).

The stability and dynamic balance of the gut microbiota is important for disease resistance and nutrient uptake in animals (Annuk et al., 2010), and the diversity of gut microbiota plays an important role in animal health (Diaz Carrasco et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021). Dietary CP level plays an important role in regulating microbial diversity (Ma et al., 2017), with different CP levels can change diversity of gut microbiota, and the composition of animal gut microbiota becomes simpler under low level protein diet (Cho et al., 2015). In this study, the diversity and relative abundance of gut microbial tended to decrease as dietary ME level increased, while an increase in dietary CP level led to a gradual increase in gut microbial diversity and relative abundance.

CONCLUSION

-

a.

Dietary ME level significantly affected mortality rate, the mortality rate of 11.31 MJ/kg group was the highest.

-

b.

The 11.31 MJ/kg ME significantly increased the proportion of pectoral FSAA and decreased the proportion of BAA. Dietary CP level significantly affected glutamate content, the BAA to TAA ratio was relatively small and FSAA ratio was higher at the 14% CP level.

-

c.

The 16% CP level increased gut microbiota diversity and relative abundance, but at the same time increased Proteobacteria abundance, which may result in unstable gut microbiota and metabolic disturbances.

-

d.

The present study suggested that the medium dietary ME (11.51 MJ/kg) and low CP (14–15%) levels can be helpful for enhancing pectoral muscle composition, increase meat quality such as flavor and nutritional value, and benefit for gut microbiota in native growing chickens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank BAAFS Academy Capacity Building Project (KJCX20200421), the earmarked fund for CARS (CARS-41-Z04), and Beijing Innovation Consortium of Agriculture Research System (BAIC06-2022) for providing financial supports, and the staff from Lvdudu Farm for feeding and management of the experimental birds.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declared that we have no conflicts of interest to this work.

REFERENCES

- Aaslyng M.D, Meinert L. Meat flavour in pork and beef–from animal to meal. Meat. Sci. 2017;132:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hafeez H.M., Saleh E.E.S., Tawfeek S.S., Youssef I., Hemida M. Effects of high dietary energy, with high and normal protein levels, on broiler performance and production characteristics. J. Vet. Med. Res. 2016;23:94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Abouelezz K.F.M., Wang Y., Wang W., Lin X., Li L., Gou Z., Fan Q., Jiang S. Impacts of graded levels of metabolizable energy on growth performance and carcass characteristics of slow-growing yellow-feathered male chickens. Animals (Basel) 2019;9:461. doi: 10.3390/ani9070461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A.A., Yang C., Zhang J., Kalwar Q., Ding X. Effects of dietary energy levels on rumen fermentation, microbial diversity, and feed efficiency of Yaks (Bos grunniens) Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:625. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari S.M., Sadeghi A.A., Aminafshar M., Shawerang P., Chamani M. The effect of energy sources and levels on performance and breast amino acids profile in Cobb 500 broiler chicks. Iran J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2017;7:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Annuk H., Shchepetova J., Kullisaar T., Songisepp E., Zilmer M., Mikelsaar M. Characterization of intestinal lactobacilli as putative probiotic candidates. J. Appl. Microbio. 2010;94:403–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody R., Gerber G., Luevano J., Gatti D., Somes L., Svenson K. Diet dominates host genotype in shaping the murine gut microbiota. Cell Host. Microbe. 2015;17:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.L., Zhao G.P., Zheng M.Q., Wen J., Yang N. Estimation of genetic parameters for contents of intramuscular fat and inosine-5’-monophosphate and carcass traits in Chinese Beijing-You chickens. Poult. Sci. 2008;87:1098–1104. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Luo S.C., Yan Gut microbiota implications for health and welfare in farm animals: a review. Animals (Basel) 2021;12:93. doi: 10.3390/ani12010093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Hwang O., Park S. Effect of dietary protein levels on composition of odorous compounds and bacterial ecology in pig manure. Asian Austral. J. Anim. 2015;28:1362. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrystal P.V., Moss A.F., Khoddami A., Naranjo V.D., Selle P.H., Liu S.Y. Effects of reduced crude protein levels, dietary electrolyte balance, and energy density on the performance of broiler chickens offered maize-based diets with evaluations of starch, protein, and amino acid metabolism. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:1421–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2019.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel H., Gholami A.M., Berry D., Desmarchelier C., Hahne H., Loh G., Mondot S., Lepage P., Rothballer M., Walker A., Böhm C., Wenning M., Wagner M., Blaut M., Kopplin P.S., Kuster B., Haller D., Clavel T. High-fat diet alters gut microbiota physiology in mice. ISME J. 2014;8:295–308. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DB11/T 1378-2016. Technical regulations of feeding and management of Beijing You Chicken. 312 Beijing, Beijing Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision. 2016.

- De Bandt J.P., Waligora-Dupriet A.J., Butel M.J. Intestinal microbiota in inflammation and insulin resistance: relevance to humans. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. 2011;14:334–340. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328347924a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippo C., Cavalieri D., Di Paola M., Ramazzotti M., Poullet J.B., Massart S., Collini S., Pieraccini G., Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Olmo A., Calzada J., Gaya P., Nuñez M. Proteolysis and flavor characteristics of Serrano ham processed under different ripening temperature conditions. J. Food Sci. 2015;80:C2404–C2412. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Carrasco J.M., Casanova N.A., Fernández Miyakawa M.E. Microbiota, gut health and chicken productivity: what is the connection? Microorganisms. 2019;7:374. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7100374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Simon C., Mumm R., Hall R.D. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics of volatiles as a new tool for understanding aroma and flavour chemistry in processed food products. Metabolomics. 2019;15:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11306-019-1493-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong T.S., Luu K., Lagishetty V., Sedighian F., Woo S.L., Dreskin B.W., Katzka W., Chang C., Zhou Y., Arias-Jayo N., Yang J., Ahdoot A., Li Z., Pisegna J.R., Jacobs J.P. A high protein calorie restriction diet alters the gut microbiome in obesity. Nutrients. 2020;12:3221. doi: 10.3390/nu12103221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H.P., Xie M., Wang W.W., Hou S.S., Huang W. Effects of dietary energy on growth performance and carcass quality of white growing Pekin ducks from two to six weeks of age. Poult. Sci. 2008;87:1162–1164. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L.C., Song D.J., Kan N., Dong G.Z., Zhang J.H. Effects of various levels of dietary energy and protein on meat quality of broilers. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2002;3:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Feed Database in China. Tables of feed composition andnutritive values in China. Beijing: Feed Database in China; 2013. http://www.chinafeeddata.org.cn.

- Fei N., Zhao L. An opportunistic pathogen isolated from the gut of an obese human causes obesity in germfree mice. ISME J. 2013;7:880–884. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira G.D.S., Pinto M.F., Neto M.G., Ponsano E.H.G., Gonçalves C.A., Bossolani I.L.C., Pereira A.G. Accurate adjustment of energy level in broiler chickens diet for controlling the performance and the lipid composition of meat. Cienc Rural. 2015;45:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Geng A.L., Shi X.L., Wang H.H., Zhang J., Chu Q., Liu H.G. Effects of dietary crude protein levels on laying performance and egg quality of Beijing You Chicken under free range system. Chinese J. Anim. Nutr. 2011;23:307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Geng A.L., Zhou Y.X., Zhang Y., Zhao F.R. Crude protein level of 32 to 43 weeks of age Beijing You Chicken under free-range system. China Poult. 2014;36:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts L., Lazarevic V., Derrien M., Everard A., Van Roye M., Knauf C., Valet P., Girard M., Muccioli G.G., François P., de Vos W.M., Schrenzel J., Delzenne N.M., Cani P.D. Altered gut microbiota and endocannabinoid system tone in obese and diabetic leptin-resistant mice: impact on apelin regulation in adipose tissue. Front. Microbiol. 2011;2:149. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girish C.K., Rao S.V., Payne R.L. Wageningen Academic Publishers; Wageningen: 2013. Effect of Reducing Dietary Energy and Protein on Growth Performance and Carcass Traits of Broilers. In Energy and Protein Metabolism and Nutrition in Sustainable Animal Production; pp. 175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch K. Consumer perceptions of fresh meat quality: cross-national comparison. Brit. Food J. 2000;102:177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hocquette J.F., Gondret F., Baéza E., Médale F., Jurie C., Pethick D.W. Intramuscular fat content in meat-producing animals: development, genetic and nutritional control, and identification of putative markers. Animal. 2010;4:303–319. doi: 10.1017/S1751731109991091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.A., Islam A.F., Iji P.A. Energy utilization and performance of broiler chickens raised on diets with vegetable proteins or conventional feeds. Asian J. Poult. Sci. 2012;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Howe P., Meyer B., Record S., Baghurst K. Dietary intake of long-chain ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: contribution of meat sources. Nutrition. 2006;22:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irm M., Taj S., Jin M., Luo J., Andriamialinirina H.J.T., Zhou Q. Effects of replacement of fish meal by poultry by-product meal on growth performance and gene expression involved in protein metabolism for juvenile black sea bream (Acanthoparus schlegelii) Aquaculture. 2020;528 [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.R., Lepp D., Godfrey D.V., Orban S., Ross K., Delaquis P., Diarra M.S. Effects of wild blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) pomace feeding on gut microbiota and blood metabolites in free-range pastured broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:3739–3755. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahan K., Paterson A., Piggott J., Spickett C. Chemometric modeling to relate antioxidants, neutral lipid fatty acids, and flavor components in chicken breasts. Poult. Sci. 2005;84:158–166. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.Q., Jiang Z.Y., Zheng C.T., Lin Y.C., Hong P., Chen F., Ruan D. Effects of levels of dietary metabolic energy and crude protein on growth performance and meat quality of chinese yellow broilers between 43 and 63 days. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2013;46:5205–5216. [Google Scholar]

- Jlali M., Gigaud V., Metayer-Coustard S., Sellier N., Tesseraud S., Bihan-Duval E.Le, Berri C. Modulation of glycogen and breast meat processing ability by nutrition in chickens: Effect of crude protein level in 2 chicken genotypes. J. Anim. Sci. 2012;90:447–455. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D.R., Lee T.K., Park J., Fenner K., Helbling D.E. The functional and taxonomic richness of wastewater treatment plant microbial communities are associated with each other and with ambient nitrogen and carbon availability. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;17:4851–4860. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson F.H, Tremaroli V., Nookaew I., Bergström G., Behre C.J., Fagerberg B., Nielsen J., Bäckhed F. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliada A., Syzenko G., Moseiko V., Budovska L., Puchkov K., Perederiy V., Gavalko Y., Dorofeyev A., Romanenko M., Tkach S., Sineok L., Lushchak O., Vaiserman A. Association between body mass index and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in an adult Ukrainian population. BMC Microbial. 2017;17:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1027-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouba M., Enser M., Whittington F.M., Nute G.R., Wood J.D. Effect of a high-linolenic acid diet on lipogenic enzyme activities, fatty acid composition, and meat quality in the growing pig. J. Anim. Sci. 2003;81:1967–1979. doi: 10.2527/2003.8181967x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouba M., Mourot J. A review of nutritional effects on fat composition of animal products with special emphasis on n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochimie. 2011;93:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajmalnik-Brown R., Ilhan Z.E., Kang D.W., DiBaise J.K. Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2012;27:201–214. doi: 10.1177/0884533611436116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara K. Glutamate: from discovery as a food flavor to role as a basic taste (umami) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;90:719S–722S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudadio V., Dambrosio A., Normanno G., Khan R.U., Naz S., Rowghani E., Tufarelli V. Effect of reducing dietary protein level on performance responses and some microbiological aspects of broiler chickens under summer environmental conditions. Avian. Biol. Res. 2012;5:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lei J.Q., Dong Y.Y., Hou Q.H., He Y., Lai Y.J., Liao C.Y., Kawamura Y., Li J.Y., Zhang B.K. The intestinal microbiota regulate certain meat quality parameter in chicken. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.747705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R.E., Turnbaugh P.J., Klein S., Gordon J.I. Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvak Y., Byndloss M.X., Tsolis R.M., Bäumler A.J. Dysbiotic Proteobacteria expansion: a microbial signature of epithelial dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017;39:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.G. Current situation and future outlook of the oil chicken industry in Beijing. China Poult. 2020;37:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.B., Yan H.L., Zhang Y., Hu Y.D., Zhang H.F. Effects of dietary energy and protein content and lipid source on growth performance and carcass traits in Pekin ducks. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:4829–4837. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C.A., Stombaugh J.I., Gordon J.I., Jansson J.K., Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N., Tian Y., Wu Y., Ma X. Contributions of the interaction between dietary protein and gut microbiota to intestinal health. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2017;18:795–808. doi: 10.2174/1389203718666170216153505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magne F., Gotteland M., Gauthier L., Zazueta A., Pesoa S., Navarrete P., Balamurugan R. The firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio: a relevant marker of gut dysbiosis in obese patients? Nutrients. 2020;12:1474. doi: 10.3390/nu12051474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcu A., Vacaru-Opriş I., Dumitrescu G., Marcu A., Petculescu C.L., Nicula M., Dronca D., Kelciov B. Effect of diets with different energy and protein levels on breast muscle characteristics of broiler chickens. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013;46:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Marcu A., Vacaru-Opriş I., Marcu A., Nicula M., Dronca D., Kelciov B. Effect of different levels of dietary protein and energy on the growth and slaughter performance at “Hybro PN+” broiler chickens. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2012;45:424–431. [Google Scholar]

- Matus-Aragón MÁ., Salinas-Ruiz J., González-Cerón F., Sosa-Montes E., Pro-Martínez A., Hernández-Mendo O., Cuca-García JM., Mendoza-Pedroza SI., Hernández-Blancas B. Productive performance of mexican creole pullets and immature males fed different levels of metabolizable energy and crude protein. Poultry. 2022;1:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mir N.A., Rafiq A., Kumar F., Singh V., Shukla V. Determinants of broiler chicken meat quality and factors affecting them: a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017;54:2997–3009. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2789-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]