Abstract

Many treatments have been used for glucose metabolism diseases such as type 2 diabetes, and all of those treatments have several advantages as well as limitations. This review introduces a 3D co-culture intestinal organoid system developed from stem cells, which has the special function of simulating human tissues. Recent studies have revealed that the gut is an important site for exploring the interactions among glucose metabolism, gut microbial metabolism, and gut microbiota. Therefore, 3D intestinal organoid systems can be used to imitate the congenital errors of human gut development, drug screening, food transportation and toxicity analysis. The intestinal organoid system construction methods and their progress as compared with traditional 2D culture methods have also been summarised in the manuscript. This paper discusses the research progress in terms of intestinal organoids applicable to glucose metabolism and provides new ideas for developing anti-diabetic drugs with high efficiency and low toxicity.

Keywords: 3D co-culture, Intestinal organoid, Glucose metabolism

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Normal organoid construction and diabetic organoid construction are summarised.

-

•

Effects of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway on organoid differentiation.

-

•

Intestinal insulin secreted by intestinal-like organs for diabetes treatment.

-

•

Secretion of intestinal insulin is controlled by intestinal transporter proteins.

1. Introduction

Diabetes and its complications are one of the world's major public health challenges (Agunloye and Oboh, 2022). Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a typical metabolic disease characterised by impaired islet sensitivity and relatively insufficient insulin secretion (Zhao et al., 2020). At present, the main treatment strategies for T2DM include surgery, medication, and diet (Koch and Shope, 2020). Insulin injections are the most effective method for controlling blood sugar (Home et al., 2014). However, these injections confer also accompanied by an increased risk of cardiovascular complications. Therefore, a therapeutic strategy for T2DM needs to be explored. Diabetes is caused by various factors. Recently, many studies have proposed that diabetes can be tackled by regulating the metabolism by the gut microflora (Lin et al., 2021). A model of glucose metabolism for differentiating intestinal stem cells into islet-producing cells has been widely studied.

The intestine consists of four layers the outermost epithelial layer, submucosa, innermost muscular layer, and innermost mucosal layer (a hollow lumen) (Zhao et al., 2020). The intestinal epithelium is part of the mucosal layer, which is one of the fastest-renewing tissues. The regulation of intestinal homeostasis is mediated by a combination of signalling pathways involving mature secretory cells, mature absorptive cells, progenitor/transporter-amplified cells, the cellular ecotone of stem cells, and the physical ecotone of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Meran et al., 2017). Intestinal stem cells are the main driving force for updating the intestinal epithelium once every 5 days and are nourished by the ecological niche to maintain self-renewal and cell differentiation (Zhang et al., 2020). Intestinal stem cells are located at the bottom of the intestinal crypt and constantly migrate to the apex to produce intestinal mucosal cells, which are important for maintaining environmental homeostasis in the intestinal epithelium.

2. Progress on organoid research

Organoids came into being owing to the diversity and complexity of intestinal epithelial cells and the inability to accurately study the function of the intestinal epithelium using a single cell line. Organoids are an in vitro 3D culture system developed for various diseases simulate healthy tissues, pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and patient organoids in a culture medium containing specific growth factors that can recapitulate all cell species found in vivo and mimic the special functions of tissue in vivo (Tsakmaki et al., 2020a, Tsakmaki et al., 2020b). Organoid formation can be initiated by two types of stem cells from different sources: adult stem cells (ASCs) and PSCs (Drost and Clevers, 2017; Sinagoga and Wells, 2015). ASCs are important for mature cell regeneration and homeostasis. PSCs can be used in the development of the organs responsible for embryonic stem cell (ESC) and induced PSC (IPSC) formation (Artegiani and Clevers, 2018). At present, organoids of the intestinal tract, stomach, pancreas, liver, kidney, prostate, lung, brain, muscle, fat, and retina have been established (Fligor et al., 2020; Homan et al., 2019; Loomans et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2019; Pellegrinelli et al., 2014; Smits and Schwamborn, 2020; Takebe et al., 2014; Broda et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020a, Zhao et al., 2020b; Zietek and Daniel, 2015, Zietek et al., 2015). As the first generation of organoids, 3D organoids of the small intestine may be the most typical example with organoid characteristics (Zhang et al., 2020). PSC formation occurs through several steps, including definitive endoderm formation, intestinal tube formation, and intestinal growth and morphogenesis, after which PSC eventually develops into the intestinal tissue (Spence et al., 2011; Wells and Spence, 2014). Intestinal organoids can be used for modelling congenital functional defects in human intestinal development, screening drugs, and in toxicity tests. Effective treatment measures were developed by establishing a model to study bacteriosis, inflammation, cancer, genetics, and glucose metabolism (Bouchi et al., 2014; Burkitt et al., 2017; Dekkers et al., 2013; Leslie et al., 2015; Fujii et al., 2016). As the site of digestion and absorption, the intestine plays an important role in the formation of a protective epithelial barrier between the body and digestive environment, as well as aids digestion, absorption, and secretion. The effects of diet and nutrients on intestinal growth and development, ion and nutrient transport, secretory and absorption processes, the intestinal barrier, and the location-specific functions of the colon have all been studied using intestinal organoids as models (Yin et al., 2019a; Yin et al., 2019b). Intestinal organoids can simulate the digestion and absorption of natural phytochemicals in the body, with the characteristics of substitution, simplification, and accuracy (Huang et al., 2021).

The formation of organoids is complex and diverse. The traditional 2D single-layer culturing cannot reproduce many morphogenesis models in organ development. For example, only a single cell can be cultured using 2D culturing, and the cultured cells are flat at the same stage. Besides, the source of cultured tissues is limited, and the cell life after transplantation is short (Table 1). By proving certain culture objects, intestinal organoids help form crypt villus structures ex vivo and intestinal epithelial tissue formation in vivo, with many advantages including 3D nature, multicellularity, self-regeneration, long life, and high similarity with the original tissue, and can fully simulate the microenvironment (Table 1); these characteristics provide a good platform for developing treatments against diseases (Lancaster and Knoblich, 2014). 3D organoids also have some limitations; for example, gene operation in 3D culturing is not as effective as that using 2D cell lines and single-cell types, and the relationship between intestinal and other cells can be easily ignored. Moreover, the top of the intestinal organoids is not easy to be stimulated, may lack response to stimulation, show inconsistency in culture, and may its 3D structure construction may be complicated (Tsakmaki et al., 2020a, Tsakmaki et al., 2020b; Zhao et al., 2020a, Zhao et al., 2020b). Organoids are generated by stem cells through a series of complex mechanisms. This complexity leads to inconsistencies in tissue, structural quality, and research results. For example, there are many cell types in brain cells, which will be affected by other cells when brain organoids are applied to vira infection. Organoids derived from cells in different culture conditions and parts show obvious heterogeneity. Overcoming this complexity is a difficult problem that must be solved in drug development and disease treatment (Pak and Sun, 2021). Patients with T2DM usually have multiple organ dysfunction, and infection with SARS-CoV-2 can also result in multiple organ failure (Pak and Sun, 2021). Thus, it is necessary to form functional connections between different organoids. The existing co-culture system, the microinjection platform, air-liquid interface differentiation systems and organoid chip models have compensated for these defects (Bartfeld et al., 2015; Biton et al., 2018; Neal et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of the 2D and 3D culture methods.

| Comparison item | Traditional 2D culturing | 3D organoid culturing | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological structure |

|

|

Costa et al. (2016); Jensen and Teng, 2020; Langhans, 2018 |

| Physiologic functions |

|

|

Brafman, 2013 Cukierman et al. (2001) Park et al. (2019) Gattazzo et al. (2014); Holmes et al. (2011); Liu et al. (2018); Park et al. (2019); Sato et al. (2011); Tsakmaki et al., 2020a, Tsakmaki et al., 2020b |

| Applications |

|

|

Dunne et al. (2014); Costa et al. (2016); Haisler et al., 2013; Imamura et al. (2015); Jensen and Teng, 2020; Langhans, 2018; Le et al. (2014); Park et al. (2019); Ravi et al. (2015); Takebe et al. (2017) |

Notes: ■ Indicates defects in 2D culture; ● Indicates advantages in 3D culture.

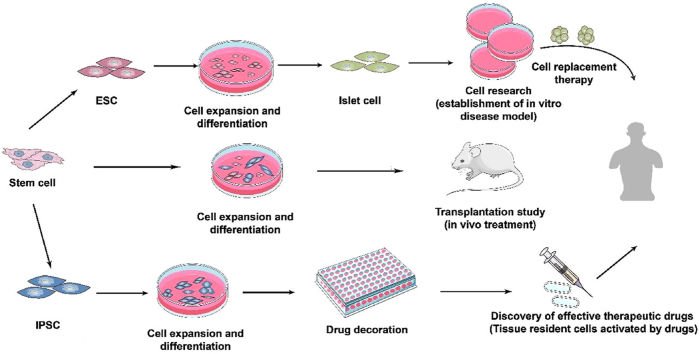

Organoid-like organs not only have microscopic anatomical characteristics and complex structures similar to real organs in the body, but also reproduce some physiological functions of their source tissues or organs. Therefore, organoids technology can highly mimic the occurrence, maintenance, and pathological processes of human tissues and organs in vitro, which is expected to compensate for the lack of model animals. Organoids have wide applications in research related to disease regulation, regenerative medicine, drug screening, and the development of new methods for disease diagnosis and treatment. At present, the organs commonly used for treating diabetes are produced by ESC, iPSC, and tissue-specific stem cells. ESCs are a type of cells originating from the inner cell mass of the vesicle and can undergo multi-embryonic differentiation and infinitely proliferate and differentiate in vitro (Thomson et al., 1998). Like ESC, PSC also has a multi-directional differentiation ability. It can be used to establish a disease model in vitro for cell research, animal experiments for organ transplantation research, and drug screening, which can help develop effective drugs against diabetes (Fig. 1) (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Application of intestinal organoids in the treatment of diabetes.

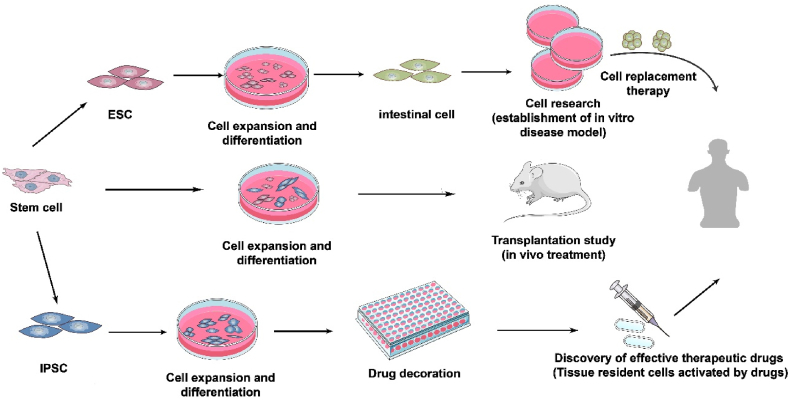

Fig. 2.

Culturing of the human islet organoids.

Of all the organs related to diabetes, pancreatic islet cells are the most important. Islet organoids have attracted attention because islet cells are closely associated with the development and progression of diabetes. With the development and functional characterisation of islet organoids that highly physiological human islet, islet organoids can be used as substitutes for human islet cells, especially islet-specific organoids from individuals with diabetes, which can be obtained from ESCs and iPSCs (Balboa et al., 2018; Manzar et al., 2017; Millman et al., 2016; Saarimäki-Vire et al., 2017).

When islet-like devices were transplanted into diabetic mice, the blood glucose balance ability of the mice was well restored. Yang et al. (2020) used islet organoids to screen small molecules that promote the proliferation of β cells in vitro. Ma et al. (2018) successfully corrected the pathogenic mutations in patients with congenital diabetes by combining gene editing and islet organ differentiation in vitro, and effectively restored the normal function of the β cells. Pancreatic organ technology is expected to simulate the development of the pancreas in vitro, and this process is conducive to the construction of diabetes models, thereby promoting the study of the mechanism of diabetes. For example, researchers have established pancreatic-like organ models using patient-derived iPSCs (Drost and Clevers, 2017). Simultaneously, patients' cells and humanoid organs can be utilised as instructive disease models that recreate the pathogenesis and phenotype of specific patients and can be used to test patient-specific drug responses during screening owing to improvements in iPSC-derived technology and personalised medicine. Millman et al. (2016) used treated stem cell-derived β-cells from human iPSCs derived from patients with type 1 diabetes with dobutamine, liraglutide and LY2608204 in an evaluation drug screening validation experiment, and their results showed that insulin release was increased after the procedure.

3. Construction and application of intestinal organoids

3.1. Methods of organoid construction

3.1.1. Normal intestinal organoids

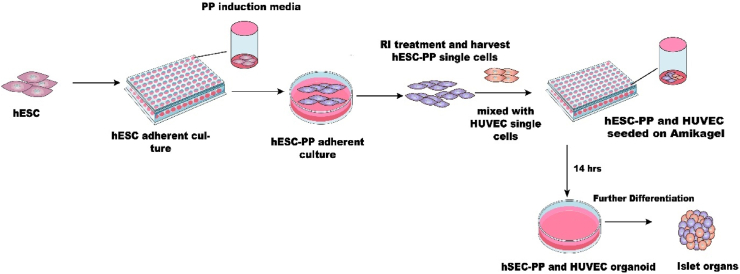

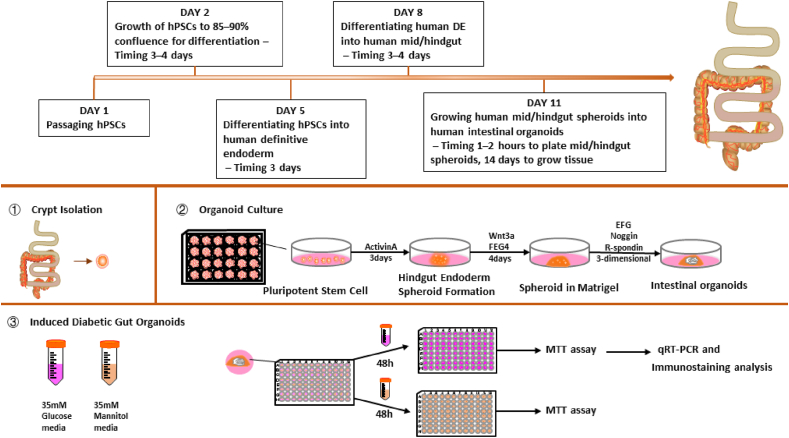

Sato et al. (2009) built the first intestinal epithelium organoid with villi and crypt structure of the small intestine using a single Lgr5+ intestinal stem cell. Matrigel is a soluble basement membrane extract isolated from Engelbreth–Holm–Swarm mouse sarcoma and supports cell morphogenesis, differentiation, and tumour growth (Kleinman and Martin, 2005). The crypts of the mouse small intestine were isolated and planted in Matrigel, after which growth factors, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) and R-Spondin1 were added. Under suitable culture conditions, a 3D structure similar to the human intestine can be cultivated (Sato et al., 2009). Spence et al. (2011) induced differentiation of human PSCs to intestinal tissues in vitro using a series of growth factors, which was the first attempt to establish 3D organoids that were very similar to foetal intestinal tissue. The basic principle of organoid construction is to add various inducing factors required for stem cell growth at a specific time, such that cells with differentiation potential can spontaneously differentiate into corresponding organoids. McCracken et al. (2011) exposed human PSCs to activin A for 3 days for definitive endoderm induction and to FGF4/WNT3A for 3–4 days for differentiating the definitive endoderm into the mid/hind-gut. Finally, the cultivation of human mid/hind-gut spheroids into human intestinal organoids (HIOs) in Matrigel with R-Spondin1, Noggin, and EGF in 3D culture (Fig. 3) (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling Pathway. Abbreviations: LRP5/6, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6; FZD, frizzled; β-cat, β-catenin; P, phosphorylation; R-spo, R-spondin; CK, casein kinase; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; Dvl, Dishevelled; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; TCF/LEF, T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor; RNF43, RING finger protein 43; LGR5, leucine-rich-repeat containing G-protein coupled receptor 5.

Fig. 4.

Human intestinal organoid culture and induction of diabetic intestinal organoids.

Organoid establishment and differentiation depend on multiple growth factors. R-spondin1, EGF, and noggin are three essential growth factors in the medium. Among them, R-spondin1, an essential Wnt signalling enhancer and Lgr5 ligand, leads to the massive proliferation of crypts in vitro (KIM et al., 2005). EGF signalling mainly promotes the proliferation of intestinal stem cells (Spit et al., 2018). Noggin, a bone morphogenetic protein pathway inhibitor, hinders the proliferation of stem cells and increases the crypt number in organoids (Lanik et al., 2018). Additionally, the choice of ECM is also a key factor that affects the development of organoids (Lanik et al., 2018). Therefore, as a basement membrane to support the growth of intestinal crypts, Matrigel is the most important material for culturing organoids. However, Matrigel may vary significantly from batch to batch, and it is difficult to guarantee that each batch will have the same number of growth factors and other vital components (Yin et al., 2019c). Furthermore, Matrigel has certain safety concerns for clinical use, especially in terms of its ability to control biochemical and biophysical properties, as well as the possibility of pathogen transfer and the tissue-specific signals essential for organoid development and maturation (Capeling et al., 2019). The use of decellularised small intestine-derived hydrogel instead of Matrigel maximises the recapitulation of the gut's inherent ECM microenvironment to support the growth and development of intestinal organoids, reaching a level comparable to that of Matrigel. Giobbe et al. (2019) built decellularised tissue-derived ECM hydrogels using decellularised porcine small intestine (SI) mucosa/submucosa. These ECM gels can be employed for mouse and human organoid cultures, organoid administration in vivo, and cell growth with stable transcriptome signatures. Capeling et al. (2019) used non-adhesive alginate hydrogels as a substitute for Matrigel to culture HIOs differentiated from human PSCs. In this study, alginate-grown and Matrigel-grown HIOs were hardly distinguishable, and both were similar to human foetal intestine. Moreover, non-adhesive alginate hydrogels overcome many of the limitations of Matrigel and are more cost-effective than Matrigel or polyethylene glycol (Kim et al., 2022).

Except for external factors, the growth of organoids is mainly controlled by multiple signalling pathways. Essential growth signals, Wnt3, EGF and Notch ligands, are produced by Paneth cells (Jensen and Teng, 2020). The source of Wnt pathway agonists and the level of Wnt pathway activation they achieve are the most critical factors affecting human intestinal organoid cultures. A Wnt gradient peaking near the base of the crypt is essential to maintain the Lgr5+ stem cell population and drive progenitor cell proliferation in the adult intestinal epithelium. Compared with that of mouse enteroids, the culture of human crypts requires exogenous Wnt as a growth factor (Farin et al., 2016). For the preservation of intestinal stem cells and homeostatic self-renewal, a large amount of local Wnt signalling is required. Wnt activation at high levels causes cystic organoids to retain most of their cells in a stem cell or transit-expanded state, allowing the culture to grow indefinitely. On the cell surface, Wnt proteins bind the receptor complexes of two molecules: low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6) and Frizzled (FZD) (Fig. 3). The binding of Dishevelled (Dvl) and the cytoplasmic fraction of FZD may promote the formation of LRP-FZD dimers by binding axin molecules to form multimers. The degradation of β-catenin interferes with a series of molecular rearrangements. RNF43/ZNRF3 is bound and removed from the stem cell surface by the complex produced by Rspo and LGR4/5/6 receptors, resulting in the accumulation of FZD receptors and the preservation of the stem cell population's heightened Wnt-responsive state. The redistribution of axin-associated kinase GSK and CK complexes at the plasma membrane leads to the inactivation of β-catenin destruction. Wnt target gene transcription is induced by intracellular-catenin translocation to the nucleus and by binding DNA transcription factors of TCF/TEF (Bar-Ephraim et al., 2020; Idris et al., 2021; Nusse and Clevers, 2017; Tsakmaki et al., 2020a, Tsakmaki et al., 2020b). Li et al. found that cell volume compression enhances Wnt/β-catenin signalling to regulate intestinal organoid growth. Compression of cell volume stabilised the formation of LRP6 signal bodies. Thus, the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway was strengthened, driving the self-renewal of intestinal stem cells in intestinal organoids, and promoting organoid growth (Li et al., 2021).

3.1.2. Diabetic pathological intestinal organoids

The gut is an important component of luminal signalling and metabolic control. It is home to enteroendocrine cells that produce more than 20 different bioactive peptides linked to local absorption and motility regulation, satiety signalling, and β cell function augmentation (Filippello et al., 2021). Compared with the normal gut, diabetic gut cells are exposed to hyperglycemia for a long time, leading to intestinal stem cell dysfunction, impaired development, and impaired gastrointestinal hormone secretion. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) produced by L-cells are important in regulating glucose homeostasis. Glucotoxicity can impair L-cell differentiation. Organoids from the normal gut preserve tissue-specific characteristics well. Intestinal organoids exposed to high-glucose environments impair the expression of TF, Ngn3, and Neurod1, leading to impaired differentiation of enteroendocrine cells and L-cells, and the induction of diabetes (Matano et al., 2015). Normal colon epithelium transforms into colorectal cancer and requires multiple gene mutations. Colorectal cancer reportedly occurs owing to cellular mutations that lead to deregulation of cell proliferation regulation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Matano et al. (2015) used the CRISPR Cas9 genome editing system to insert mutants into colonic epithelial cells to achieve clonal expansion of mutant stem cells by modifying culture conditions, such as growth factors. Because 90% of colorectal cancers have an abnormally active Wnt pathway, the use of a Wnt-free Lgr5+ stem cell medium allows for creating a tumour-like organoid biobank (Idris et al., 2021). Modified from normal organoids, colorectal cancer organoids allow for better study of tumour organoids. Normal intestinal organoids were exposed to hypoxia and lipopolysaccharides for 48 h. These phenomena could demonstrate intestinal epithelial inflammation when damaged organoids increasingly express pro-inflammatory cytokine genes, including interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α (Chusilp et al., 2020). Massive removal of the small intestine results in a condition known as short bowel syndrome, which causes the loss of nutrients and makes it difficult to prevent kidney failure. Sugimoto et al. (2021) used the structural similarity between the small intestine and colon to generate a functional small intestinalized colon by replacing ileal epithelial cells with small intestinal epithelial cells through organoid xenografts, providing a new idea for treating short bowel syndrome.

3.2. Application of intestinal organoids in the research of glucose metabolism

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most challenging health problems faced by our society and increases the risk of morbidity and mortality due to complications. Current treatments do not allow patients to fully recover. To better understand human diabetes and develop treatment regimens or targets to alleviate the condition, it is necessary to develop new disease models to describe the pathology of diabetes more accurately. Scientists have proposed the ‘organoids therapy’. The key aspects of their simulated tissues in vivo and simulated specific organ functions have been summarised by Lancaster and Knoblich (2014) and Tsakmaki et al. (2020a). Compared with animal models, organoid compounds can originate from human beings. Thus, it is not necessary to extrapolate the discovery of animal models to human beings. In comparison with organ models derived directly from humans, organoid models are easier to obtain and can be personalised. Because of their functionality, organic analogues can be employed in clinical applications as tailored high-throughput drug screening platforms for evaluating the possible therapeutic effects and as a novel source for organ donation (Dutta et al., 2017; Fatehullah et al., 2016; Clevers, 2016). During organoid culture, stem cells aggregate and differentiate according to the biophysical clues to form complex cell structures and imitate the structure and functions of mature tissues (Dutta et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; McCauley and Wells, 2017). Organoid culture is a bound-breaking technique for researching organ development, pathogenicity, disease models, and drug development. The intestine is an organ with various physiological functions. Intestinal epithelial cells include goblet cells, columnar cells, endocrine cells, and Pan's cells. These cells are distributed in the inner intestinal wall and play significant roles in physiological activities. Sato and colleagues first reported the production of 3D intestinal organoids in vitro, which were produced from intestinal tissues isolated from mice or humans (Sato et al., 2009). Generally, the applications of mouse and HIOs in glucose metabolism-related research are mainly focussed towards disease modelling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine.

3.3. Application of 3D intestinal organoids in diabetes treatment

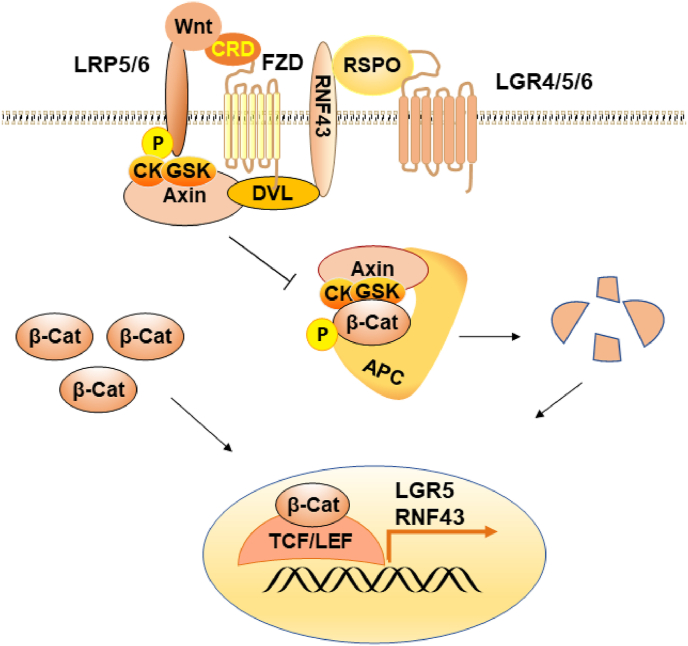

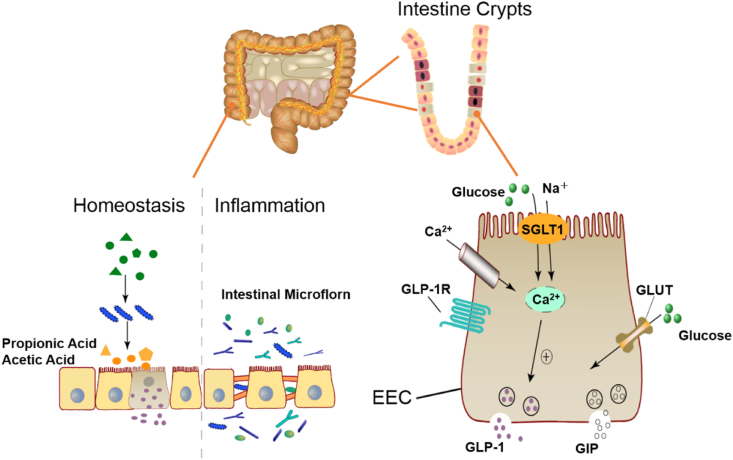

The intestinal epithelium is composed of villi and crypts, where many intestinal endocrine cells gather. GLP-1 and GIP, two types of incretins, can regulate blood glucose in the human body. Additionally, GIP-1 is a potent inhibitor of insulin secretion and glucagon (Gilbert and Pratley, 2020). In reaction to consumed foods, the gut releases hormones known as incretins. These hormones result in a glucose-induced insulin response (Kazeem et al., 2021). They are secreted by intestinal endocrine L-cells and K-cells. L-cells and K-cells are important components of intestinal endocrine cells, which are differentiated from stem cells from the small intestinal recess (Tsakmaki et al., 2017). L-cells are mainly distributed in the jejunum and ileum and can establish contacts with proteins, fats, glucose and other nutrients entering the intestinal tract through the apical villi structures, thereby promoting the secretion of GLP-1 (Filippello et al., 2021; Gómez and Boudreau, 2021). K-cells are mainly distributed in the duodenum and secrete GIP. GIP can act in adipocytes and islet cells, and finally promote insulin secretion (Svendsen and Holst, 2016). Because the intestine has the function of nutrition perception, it can recognise incoming nutrients. The enteroendocrine cells can release some peptide hormones, such as GLP-1 and GIP (Chen et al., 2014) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Intestinal microbiota in homeostasis and dysbiosis and an overview of the intestinal microbiota promoting insulin secretion.

Entero-insulin secreted by intestinal organoids is used as an alternative and renewable source of pancreatic β cells in diabetes treatment. This is an application of intestinal organoids in the study of glucose metabolism. Chen et al. (2014) transferred key transcription factors (Ngn3, Pdx-1, and MafA) into intestinal crypts, which can promote the differentiation of intestinal crypt cells into endocrine cells. These cells formed ‘new islets’ in the middle and lower crypt base, and these ‘new islets’ produced insulin and showed characteristics of β cells. Additionally, they transplanted these intestinal organs into diabetic mice to show their regulatory effects on hyperglycaemia. If this research can be achieved in the human body, this will open up new ideas for treating diabetes. Bouchi et al. (2014) found that the inhibition of the transcription factor Foxo1 resulted in the differentiation of mouse enteroendocrine progenitor cells into glucose-responsive insulin-producing cells. Using intestinal organoids derived from human iPSCs, they found that the inhibition of Foxo1 using either dominant, negative mutant or lentivirus-encoded small hairpin RNAs promoted the generation of insulin-positive cells. Finally, insulin produced from the gastrointestinal tract was transferred into STZ-induced diabetic mice and found to improve diabetes. Talchai and Accili (2015) found that inhibiting Foxo1 expression in pancreatic or endocrine progenitor cells increased the number of β cells. However, the islets of mice lacking Foxo1 did not respond well to glucose, leading to glucose intolerance. The reason is that Foxo1 integrates cues that determine the developmental timing, pool size, and functional characteristics of endocrine progenitors, resulting in legacy effects on adult β cell quality and function.

Developing or enhancing the anorexic potential of the intestine can improve the health of glucose metabolism. For example, the density of peptide YY (PYY) can affect the anorexic potential of the intestine. Brooks et al. (2016) used targeted free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2)-deficient mice and intestinal organoids to explore the mechanism in vivo and found that FFAR2 signalling drives the expansion of the PYY cell population, resulting in increased PYY secretion, which in turn increases the intestinal anorexia signalling. After Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) operation on obese mice, the intake of food and liquid sucrose decreased, and the intestinal flora, faecal metabolites, fat distribution in plasma, and brain neuron activity of obese mice changed after operation (Zizmare et al., 2022). Obese patients with diabetes have reduced food intake after RYGB due to increased postoperative levels of GLP-1 and PYY, which stimulate insulin secretion and reduce patient appetite after ingesting food (Goldspink et al., 2020). Using IEC-18 cells and mouse organoids, Kwon et al. (2021) demonstrated that administration of RYGB or AREG-induced GLUT1 overexpression in small intestinal enterocytes, thereby enhancing the ability of glucose uptake.

Intestinal organoids can also be used to study the physiological function of the intestinal epithelium and functional gastrointestinal process. For example, organoids are used to study intestinal nutrient transport, and drug absorption, intestinal endocrine and intracellular signal transduction (Zietek et al., 2015). Intestinal transporters such as SGLT1 and PepT1 are involved not only in absorbing nutrients, but also in transporting some drugs and controlling the secretion of incretin such as GLP-1 (Dye et al., 2015). Research on enteral nutrition translocation and sensing is of great importance for treating malabsorption syndrome and metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity. Zietek et al. (2015) demonstrated that mouse intestinal organoids are the most ideal in vitro model for studying intestinal nutrient transport and sensing. As an in vitro model, the intestinal organoid model provides a unique platform for the study of gastrointestinal basic nutrition, drug bioavailability, and fluorescent live-cell imaging of intracellular signal transduction. In 2020, their team also verified the applicability of 3D intestinal organoids in vitro research, such as intestinal biochemical processes related to nutrient transport, drug absorption, transport, and metabolism (Zietek et al., 2020). This provides an innovative method for in vitro testing in the field of intestinal research and metabolomics.

Intestinal organoids are also used to explore the pathology of the intestinal tract in obesity or diabetes. Tissues from obese and patients with diabetes, or patients before and after bariatric surgery, are then cultured in 3D to investigate the effect of obesity on enteroendocrine cell function, or to investigate whether there is a benefit to epithelial cell function after intestinal surgery (Bewick and Jacobs, 2021). However, no research has been conducted on the organs of the obese or patients with diabetes before and after intestinal surgery. Most of them still use mouse or human intestinal samples. Rhee's research team reported the distribution and changes of intestinal endocrine cells in obese volunteers who had not suffered from or had T2DM after RYGB operation (Rhee et al., 2015). They found that after the RYGB operation, the expression of GCG increased and the immune response cells of GLP-1 increased. Although the expression levels of PYY, CCK and GIPmRNA did not increase, the number of their positive cells increased, which was consistent with the results of Kwon et al. (2021). Glucose and palmitic acid have lipotoxic effects on many human organs. At the intestine level, palmitate impairs intestinal insulin sensitivity and is associated with an increased incidence of obesity and T2DM. Filippello et al. (2022) constructed mouse intestinal organoids to grow in a high concentration of palmitate (0.5 mM) for 48 h, and found that lipotoxicity affected the differentiation of enterocytes, goblet cells and CCK cells, which may lead to obesity and diabetes.

Gut organoids are also a new tool for studying microbes in the field of diabetes, as they allow selected microorganisms to be added during organoid culture or injected into the lumen of the organoid. The microbial diversity in obese diabetes is studied through organoids, and a controlled study of intestinal microbes and metabolites can be carried outconducted. Short chain fatty acids are the main intestinal microbial metabolite, which is mainly composed of acetate, propionate, butyrate, and other components. Propionate can trigger the secretion of GLP-1, PYY, and GPR and affect glucose homeostasis (Cunningham et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). Patients with T2DM are accompanied by intestinal disorders. The intestinal barrier damage and abnormal absorption of metabolites caused by intestinal flora imbalance in patients will promote harmful bacteria and substances to enter the circulation, resulting in an imbalance of glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion disorders, which finally causes multiple organ damage (Bielka et al., 2022). The changes in intestinal flora were observed in the duodenal mucosa samples of type 1 diabetes (T1D) patients by Pellegrini et al. (2017), in which is the ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes increased, and the content of Proteobacteria and Bacteroides decreased. Siljander et al. (2019) suggested that the pro-inflammatory environment in the gut of T1D patients was altered with an increased relative abundance of Bacteroides and decreased levels of Firmicutes. Therefore, the gut microbiota may be a new target for treating diabetes and its complications. Xu and colleagues explored the role and mechanism of the metabolite of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (MAM) in the intestinal epithelium of diabetic mice by analysing the microbial population in the colonic tissue of T2DM mice (Xu et al., 2020). MAM from F. prausnitzii can restore the structure and function of the intestinal barrier under DM conditions by regulating tight junction pathways and protein ZO-1 expression. Intestinal organoids provide a valuable platform in vitro platform for us to study the interaction between dietary patterns, intestinal microbial metabolites, and the microbiome.

4. Conclusions

Over the past decade, the development of organoid technology in the fields of disease treatment, regenerative medicine, personalised medicine, and drug research has made great achievements. Organoids were applied to build disease models with real and effective characteristics, which pave the way for exploring the disease mechanism, the development of efficient and safe treatment drugs. The studies of cell replacement therapy and primary tissue-building organoids for diabetes are relatively mature, but there are still limitations to immune response and transplantation techniques. Whether suitable cultures can be screened is a huge challenge for the mass production of living organoids. Human-on-a-chip combines a single-organ chip with a multi-organ chip, which enables the organs to cooperate. In the future, the application of the organ chip model to the treatment of various complex diseases and drug testing should be further explored. New biomaterials that can replace matrix gels need to be continuously developed as synthetic scaffolds to improve biocompatibility and mass transport properties, and to improve reproducibility and reduce toxicity. Advances in organoid culture technology require the study of the new culture methods, accurate control of the growth conditions, making the formation of organoids more efficient and specialised, improving the 3D image processing technology, overcoming the complexity and heterogeneity in the process of organoid culture, and realising the real-time multi-directional monitoring of organoid growth. Finally, the application of organoids in drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics research enables constantly to be promoted.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jianping Nie: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Wei Liao: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zijie Zhang: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Minjiao Zhang: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yuxi Wen: Writing – review & editing. Esra Capanoglu: Writing – review & editing. Md Moklesur Rahman Sarker: Writing – review & editing. Ruiyu Zhu: Writing – review & editing. Chao Zhao: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Key Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2020J02032) and Fujian ‘Young Eagle Program’ Youth Top Talent Program.

References

- Agunloye O.M., Oboh G. Blood glucose lowering and effect of oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus)- and shiitake (Lentinus subnudus)-supplemented diet on key enzymes linked diabetes and hypertension in streptozotocin-induced diabetic in rats. Food Frontiers. 2022;3:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Artegiani B., Clevers H. Use and application of 3d-organoid technology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27(R2):R99–R107. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balboa D., Saarimäki-Vire J., Borshagovski D., Survila M., Lindholm P., Galli E., Eurola S., Ustinov J., Grym H., Huopio H., Partanen J., Wartiovaara K., Otonkoski T. Insulin mutations impair beta-cell development in a patient-derived iPSC model of neonatal diabetes. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.38519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Ephraim Y.E., Kretzschmar K., Clevers H. Organoids in immunological research. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20(5):279–293. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0248-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartfeld S., Bayram Tülay, Marc V.D.W., Huch M., Begthel H., Kujala P., Vries R., Peters P.J., Clevers H. In vitro expansion of human gastric epithelial stem cells and their responses to bacterial infection. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):126–136. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.042. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick G., Jacobs M. The way to the heart of diabetes is through your gut. Biochemist. 2021;43(2):10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bielka W., Przezak A., Pawlik A. The role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(1):480. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biton M., Haber A.L., Rogel N., Burgin G., Beyaz S., Schnell A., Ashenberg O., Su C.W., Smillie C., Shekhar K., Chen Z., Wu C., Ordovas-Montanes J., Alvarez D., Herbst R.H., Zhang M., Tirosh I., Dionne D., Nguyen L.T., Xifaras M.E., Xavier R.J. T helper cell cytokines modulate intestinal stem cell renewal and differentiation. Cell. 2018;175(5):1307–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.008. e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchi R., Foo K.S., Hua H., Tsuchiya K., Ohmura Y., Sandoval P.R., Ratner L.E., Egli D., Leibel R.L., Accili D. FOXO1 inhibition yields functional insulin-producing cells in human gut organoid cultures. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4242. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brafman D.A. Constructing stem cell microenvironments using bioengineering approaches. Physiol. Genom. 2013;45(23):1123. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00099.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broda T.R., McCracken K.W., Wells J.M. Generation of human antral and fundic gastric organoids from pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2018;14(1):28–50. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks L., Viardot A., Tsakmaki A., Stolarczyk E., Howard J.K., Cani P.D., Everard A., Sleeth M.L., Psichas A., Anastasovskaj J., Bell J.D., Bell-Anderson K., Mackay C.R., Ghatei M.A., Bloom S.R., Frost G., Bewick G.A. Fermentable carbohydrate stimulates FFAR2-dependent colonic PYY cell expansion to increase satiety. Mol. Metabol. 2016;6(1):48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkitt M.D., Duckworth C.A., Williams J.M., Pritchard D.M. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric pathology: insights from in vivo and ex vivo models. Dis. Model. Mech. 2017;10(2):89–104. doi: 10.1242/dmm.027649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capeling M.M., Czerwinski M., Huang S., Tsai Y.H., Wu A., Nagy M.S., Juliar B., Sundaram N., Song Y., Han W.M., Takayama S., Alsberg E., Garcia A.J., Helmrath M., Putnam A.J., Spence J.R. Nonadhesive alginate hydrogels support growth of pluripotent stem cell-derived intestinal organoids. Stem Cell Rep. 2019;12(2):381–394. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.J., Finkbeiner S.R., Weinblatt D., Emmett M.J., Tameire F., Yousefi M., Yang C., Maehr R., Zhou Q., Shemer R., Dor Y., Li C., Spence J.R., Stanger B.Z. De novo formation of insulin-producing "neo-β cell islets" from intestinal crypts. Cell Rep. 2014;6(6):1046–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chusilp S., Li B., Lee D., Lee C., Vejchapipat P., Pierro A. Intestinal organoids in infants and children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2020;36(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00383-019-04581-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell. 2016;165(7):1586–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E.C., Moreira A.F., Melo-Diogo D.D., Gaspar V.M., Carvalho M.P., Correia I.J. 3D tumor spheroids: an overview on the tools and techniques used for their analysis. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016;34(8):1427–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukierman E., Pankov R., Stevens D.R., Yamada K.M. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294(5547):1708–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham A.L., Stephens J.W., Harris D.A. Intestinal microbiota and their metabolic contribution to type 2 diabetes and obesity. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2021;20(2):1855–1870. doi: 10.1007/s40200-021-00858-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers J.F., Wiegerinck C.L., de Jonge H.R., Bronsveld I., Janssens H.M., de Winter-de Groot K.M., Brandsma A.M., de Jong N.W., Bijvelds M.J., Scholte B.J., Nieuwenhuis E.E., van den Brink S., Clevers H., van der Ent C.K., Middendorp S., Beekman J.M. A functional CFTR assay using primary cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. Nat. Med. 2013;19(7):939–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drost J., Clevers H. Translational applications of adult stem cell-derived organoids. Development. 2017;144(6):968–975. doi: 10.1242/dev.140566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne L.W., Huang Z., Meng W., Fan X., Zhang N., Zhang Q., An Z. Human decellularized adipose tissue scaffold as a model for breast cancer cell growth and drug treatments. Biomaterials. 2014;35(18):4940–4949. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D., Heo I., Clevers H. Disease modeling in stem cell-derived 3D organoid systems. Trends Mol. Med. 2017;23(5):393–410. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye B.R., Hill D.R., Ferguson M.A., Tsai Y.H., Nagy M.S., Dyal R., Wells J.M., Mayhew C.N., Nattiv R., Klein O.D., White E.S., Deutsch G.H., Spence J.R. In vitro generation of human pluripotent stem cell derived lung organoids. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farin H.F., Jordens I., Mosa M.H., Basak O., Korving J., Tauriello D.V., de Punder K., Angers S., Peters P.J., Maurice M.M., Clevers H. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature. 2016;530(7590):340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature16937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatehullah A., Tan S., Barker N. Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18(3):246–254. doi: 10.1038/ncb3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippello A., Di Mauro S., Scamporrino A., Malaguarnera R., Torrisi S.A., Leggio G.M., Di Pino A., Scicali R., Purrello F., Piro S. High glucose exposure impairs L-cell differentiation in intestinal organoids: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(13):6660. doi: 10.3390/ijms22136660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippello A., Di Mauro S., Scamporrino A., Torrisi S.A., Leggio G.M., Di Pino A., Scicali R., Di Marco M., Malaguarnera R., Purrello F., Piro S. Molecular effects of chronic exposure to palmitate in intestinal organoids: a new model to study obesity and diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(14):7751. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fligor C.M., Huang K.C., Lavekar S.S., VanderWall K.B., Meyer J.S. Differentiation of retinal organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2020;159:279–302. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M., Shimokawa M., Date S., Takano A., Matano M., Nanki K., Ohta Y., Toshimitsu K., Nakazato Y., Kawasaki K., Uraoka T., Watanabe T., Kanai T., Sato T. A colorectal tumor organoid library demonstrates progressive loss of niche factor requirements during tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(6):827–838. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattazzo F., Urciuolo A., Bonaldo P. Extracellular matrix: a dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840(8):2506–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M.P., Pratley R.E. GLP-1 analogs and DPP-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes therapy: review of head-to-head clinical trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2020;11:178. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giobbe G.G., Crowley C., Luni C., Campinoti S., Khedr M., Kretzschmar K., De Santis M.M., Zambaiti E., Michielin F., Meran L., Hu Q., van Son G., Urbani L., Manfredi A., Giomo M., Eaton S., Cacchiarelli D., Li V., Clevers H., Bonfanti P., Elvassore N., De Coppi P. Extracellular matrix hydrogel derived from decellularized tissues enables endodermal organoid culture. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):5658. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldspink D.A., Lu V.B., Miedzybrodzka E.L., Smith C.A., Foreman R.E., Billing L.J., Kay R.G., Reimann F., Gribble F.M. Labeling and characterization of human GLP-1-secreting L-cells in primary ileal organoid culture. Cell Rep. 2020;31(13) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez D.P., Boudreau F. Organoids and their use in modeling gut epithelial cell lineage differentiation and barrier properties during intestinal diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.732137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisler W.L., Timm D.M., Gage J.A., Tseng H., Souza G.R. Three-dimensional cell culturing by magnetic levitation. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8(10):1940–1949. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes T.D., El-Sherbiny Y.M., Davison A., Clough S.L., Blair G.E., Cook G.P. A human NK cell activation/inhibition threshold allows small changes in the target cell surface phenotype to dramatically alter susceptibility to NK cells. J. Immunol. 2011;186(3):1538–1545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan K.A., Gupta N., Kroll K.T., Kolesky D.B., Skylar-Scott M., Miyoshi T., Mau D., Valerius M.T., Ferrante T., Bonventre J.V., Lewis J.A., Morizane R. Flow-enhanced vascularization and maturation of kidney organoids in vitro. Nat. Methods. 2019;16(3):255–262. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0325-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home P., Riddle M., Cefalu W.T., Bailey C.J., Raz I. Insulin therapy in people with type 2 diabetes: opportunities and challenges? Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1499–1508. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Chen Y., Lu S., Zhao C. Recent advance of in vitro models in natural phytochemicals absorption and metabolism. eFood. 2021;2:307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Idris M., Alves M.M., Hofstra R.M.W., Mahe M.M., Melotte V. Intestinal multicellular organoids to study colorectal cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Rev. Cancer. 2021;1876(2) doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura Y., Mukohara T., Shimono Y., Funakoshi Y., Chayahara N., Toyoda M., Kiyota N., Takao S., Kono S., Nakatsura T., Minami H. Comparison of 2D- and 3D-culture models as drug-testing platforms in breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2015;33(4):1837–1843. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen C., Teng Y. Is it time to start transitioning from 2d to 3d cell culture? Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020;7:33. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazeem M., Bankole H., Ogunrinola O., Wusu A., Kappo A. Functional foods with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitory potential and management of type 2 diabetes: a review. Food Frontiers. 2021;2:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.A., Kakitani M., Zhao J., Oshima T., Tang T., Binnerts M., Liu Y., Boyle B., Park E., Emtage P., Funk W.D., Tomizuka K. Mitogenic influence of human R-spondin1 on the intestinal epithelium. Science. 2005;309(5738):1256–1259. doi: 10.1126/science.1112521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Choi Y.S., Lee J.S., Jo S.H., Kim Y.G., Cho S.W. Intestinal extracellular matrix hydrogels to generate intestinal organoids for translational applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022;25(107):155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman H.K., Martin G.R. Matrigel: basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005;15(5):378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T.R., Shope T.R. Laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy as a treatment option for adults with diabetes mellitus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1307:299–320. doi: 10.1007/5584_2020_487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon I.G., Kang C.W., Park J.P., Oh J.H., Wang E.K., Kim T.Y., Sung J.S., Park N., Lee Y.J., Sung H.J., Lee E.J., Hyung W.J., Shin S.J., Noh S.H., Yun M., Kang W.J., Cho A., Ku C.R. Serum glucose excretion after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a potential target for diabetes treatment. Gut. 2021;70(10):1847–1856. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster M.A., Knoblich J.A. Organogenesis in a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science. 2014;345(6194) doi: 10.1126/science.1247125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhans S.A. Three-dimensional in vitro cell culture models in drug discovery and drug repositioning. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:6. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanik W.E., Mara M.A., Mihi B., Coyne C.B., Good M. Stem cell-derived models of viral infections in the gastrointestinal tract. Viruses. 2018;10(3):124. doi: 10.3390/v10030124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le V.M., Lang M.D., Shi W.B., Liu J.W. A collagen-based multicellular tumor spheroid model for evaluation of the efficiency of nanoparticle drug delivery. Artif. Cell Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2014;44(2):540–544. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2014.968820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie J.L., Huang S., Opp J.S., Nagy M.S., Kobayashi M., Young V.B., Spence J.R. Persistence and toxin production by clostridium difficile within human intestinal organoids result in disruption of epithelial paracellular barrier function. Infect. Immun. 2015;83(1):138–145. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02561-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Chen M., Hu J., Sheng R., Lin Q., He X., Guo M. Volumetric compression induces intracellular crowding to control intestinal organoid growth via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(1):63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.09.012. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Zhang J., Li S., Zheng B., Hu J. Polysaccharides isolated from Laminaria japonica attenuates gestational diabetes mellitus by regulating the gut microbiota in mice. Food Frontiers. 2021;2(1):208–217. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Oikonomopoulos A., Sayed N., Wu J.C. Modeling human diseases with induced pluripotent stem cells: from 2D to 3D and beyond. Development. 2018;145(5) doi: 10.1242/dev.156166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomans C., Williams Giuliani N., Balak J., Ringnalda F., van Gurp L., Huch M., Boj S.F., Sato T., Kester L., de Sousa Lopes S., Roost M.S., Bonner-Weir S., Engelse M.A., Rabelink T.J., Heimberg H., Vries R., van Oudenaarden A., Carlotti F., Clevers H., de Koning E. Expansion of adult human pancreatic tissue yields organoids harboring progenitor cells with endocrine differentiation potential. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;10(3):712–724. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Viola R., Sui L., Cherubini V., Barbetti F., Egli D. β Cell replacement after gene editing of a neonatal diabetes-causing mutation at the insulin locus. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;11(6):1407–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzar G.S., Kim E.M., Zavazava N. Demethylation of induced pluripotent stem cells from type 1 diabetic patients enhances differentiation into functional pancreatic β cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292(34):14066–14079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.784280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matano M., Date S., Shimokawa M., Takano A., Fujii M., Ohta Y., Watanabe T., Kanai T., Sato T. Modeling colorectal cancer using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated engineering of human intestinal organoids. Nat. Med. 2015;21(3):256–262. doi: 10.1038/nm.3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley H.A., Wells J.M. Pluripotent stem cell-derived organoids: using principles of developmental biology to grow human tissues in a dish. Development. 2017;144(6):958–962. doi: 10.1242/dev.140731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken K.W., Howell J.C., Wells J.M., Spence J.R. Generating human intestinal tissue from pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6(12):1920–1928. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meran L., Baulies A., Li V.S.W. Intestinal stem cell niche: the extracellular matrix and cellular components. Stem Cells Int. 2017. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/7970385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.J., Dye B.R., Ferrer-Torres D., Hill D.R., Overeem A.W., Shea L.D., Spence J.R. Generation of lung organoids from human pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14(2):518–540. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0104-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millman J.R., Xie C., Van Dervort A., Gürtler M., Pagliuca F.W., Melton D.A. Generation of stem cell-derived β-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal J.T., Li X., Zhu J., Giangarra V., Grzeskowiak C.L., Ju J., Liu I.H., Chiou S.H., Salahudeen A.A., Smith A.R., Deutsch B.C., Liao L., Zemek A.J., Zhao F., Karlsson K., Schultz L.M., Metzner T.J., Nadauld L.D., Tseng Y.Y., Alkhairy S., On C., Keskula P., Mendoza-Villanueva D., De La Vega F.M., Kunz P.L., Liao J.C., Leppert J.T., Sunwoo J.B., Sabatti C., Boehm J.S., Hahn W.C., Zheng G.X.Y., Davis M.M., Kuo C.J. Organoid modeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Cell. 2018;175(7):1972–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.021. e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R., Clevers H. Wnt/β-Catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169(6):985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak C.H., Sun Y. Organoids: expanding applications enabled by emerging technologies: organoids: emerging technologies and applications. J. Mol. Biol. 2021;434(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.E., Georgescu A., Huh D. Organoids-on-a-chip. Science. 2019;364(6444):960–965. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw7894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrinelli V., Rouault C., Veyrie N., Clement K., Lacasa D. Endothelial cells from visceral adipose tissue disrupt adipocyte functions in a three-dimensional setting: partial rescue by angiopoietin-1. Diabetes. 2014;63(2):535–549. doi: 10.2337/db13-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini S., Sordi V., Bolla A.M., Saita D., Ferrarese R., Canducci F., Clementi M., Invernizzi F., Mariani A., Bonfanti R., Barera G., Testoni P.A., Doglioni C., Bosi E., Piemonti L. Duodenal mucosa of patients with type 1 diabetes shows distinctive inflammatory profile and microbiota. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2017;102(5):1468–1477. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi M., Paramesh V., Kaviya S.R., Anuradha E., Paul Solomon F. 3D cell culture systems: advantages and applications. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015;230(1):16–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee N.A., Wahlgren C.D., Pedersen J., Mortensen B., Langholz E., Wandall E.P., Friis S.U., Vilmann P., Paulsen S.J., Kristiansen V.B., Jelsing J., Dalboge L.S., Poulsen S.S., Holst J.J., Vilsboll T., Knop F.K. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on the distribution and hormone expression of small-intestinal enteroendocrine cells in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58(10):2254–2258. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarimäki-Vire J., Balboa D., Russell M.A., Saarikettu J., Kinnunen M., Keskitalo S., Malhi A., Valensisi C., Andrus C., Eurola S., Grym H., Ustinov J., Wartiovaara K., Hawkins R.D., Silvennoinen O., Varjosalo M., Morgan N.G., Otonkoski T. An activating STAT3 mutation causes neonatal diabetes through premature induction of pancreatic differentiation. Cell Rep. 2017;19(2):281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Stange D.E., Ferrante M., Vries R.G., Van Es J.H., Van den Brink S., Van Houdt W.J., Pronk A., Van Gorp J., Siersema P.D., Clevers H. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and barrette's epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Vries R.G., Snippert H.J., van de Wetering M., Barker N., Stange D.E., van Es J.H., Abo A., Kujala P., Peters P.J., Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459(7244):262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siljander H., Honkanen J., Knip M. Microbiome and type 1 diabetes. EBioMedicine. 2019;46:512–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinagoga K.L., Wells J.M. Generating human intestinal tissues from pluripotent stem cells to study development and disease. EMBO J. 2015;34(9):1149–1163. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits L.M., Schwamborn J.C. Midbrain organoids: a new tool to investigate Parkinson's disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:359. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence J.R., Mayhew C.N., Rankin S.A., Kuhar M.F., Vallance J.E., Tolle K., Hoskins E.E., Kalinichenko V.V., Wells S.I., Zorn A.M., Shroyer N.F., Wells J.M. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011;470(7332):105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spit M., Koo B.K., Maurice M.M. Tales from the crypt: intestinal niche signals in tissue renewal, plasticity and cancer. Open Biol. 2018;8(9) doi: 10.1098/rsob.180120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto S., Kobayashi E., Fujii M., Ohta Y., Arai K., Matano M., Ishikawa K., Miyamoto K., Toshimitsu K., Takahashi S., Nanki K., Hakamata Y., Kanai T., Sato T. An organoid-based organ-repurposing approach to treat short bowel syndrome. Nature. 2021;592(7852):99–104. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen B., Holst J.J. Regulation of gut hormone secretion. Studies using isolated perfused intestines. Peptides. 2016;77:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe T., Zhang B., Radisic M. Synergistic engineering: organoids meet organs-on-a-chip. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(3):297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe T., Zhang R.R., Koike H., Kimura M., Yoshizawa E., Enomura M., Koike N., Sekine K., Taniguchi H. Generation of a vascularized and functional human liver from an ipsc-derived organ bud transplant. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9(2):396–409. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talchai S.C., Accili D. Legacy effect of Foxo1 in pancreatic endocrine progenitors on adult β-cell mass and function. Diabetes. 2015;64(8):2868–2879. doi: 10.2337/db14-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J.A., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Shapiro S.S., Waknitz M.A., Swiergiel J.J., Marshall V.S., Jones J.M. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakmaki A., Fonseca Pedro P., Bewick G.A. Diabetes through a 3D lens: organoid models. Diabetologia. 2020;63(6):1093–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakmaki A., Fonseca Pedro P., Bewick G.A. 3D intestinal organoids in metabolic research: virtual reality in a dish. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2017;37:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakmaki A., Fonseca Pedro P., Bewick G.A. Diabetes through a 3D lens: organoid models. Diabetologia. 2020;63(6):1093–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J.M., Spence J.R. How to make an intestine. Development. 2014;141(4):752–760. doi: 10.1242/dev.097386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Liang R., Zhang W., Tian K., Li J., Chen X., Yu T., Chen Q. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii-derived microbial anti-inflammatory molecule regulates intestinal integrity in diabetes mellitus mice via modulating tight junction protein expression. J. Diabetes. 2020;12(3):224–236. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Wei J., Liu P., Zhang Q., Tian Y., Hou G., Meng L., Xin Y., Jiang X. Role of the gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes and related diseases. Metabolism. 2021;117 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Lee M., Jones P.A., Liu S.S., Zhou A., Xu J., Sreekanth V., Wu J., Vo L., Lee E.A., Pop R., Lee Y., Wagner B.K., Melton D.A., Choudhary A., Karp J.M. A 3D culture platform enables development of zinc-binding prodrugs for targeted proliferation of β cells. Sci. Adv. 2020;6(47) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.B., de Jonge H.R., Wu X., Yin Y.L. Mini-gut: a promising model for drug development. Drug Discov. Today. 2019;24(9):1784–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.B., de Jonge H.R., Wu X., Yin Y.L. Enteroids for nutritional studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019;63(16) doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201801143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.B., Guo S.G., Wan D., Wu X., Yin Y.L. Enteroids: promising in vitro models for studies of intestinal physiology and nutrition in farm animals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67(9):2421–2428. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Huang S., Zhong W., Chen W., Yao B., Wang X. 3D organoids derived from the small intestine: an emerging tool for drug transport research. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;11(7):1697–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Lai S.S., Wu D., Liu D., Zou X., Amin I., Hesham E.S., Randolph R.J.A., Xiao J. miRNAs as regulators of antidiabetic effects of fucoidans. eFood. 2020;1(1):2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Guan J., Wang X. Intestinal stem cells and intestinal organoids. J. Genet. Genom. 2020;47(6):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zietek T., Daniel H. Intestinal nutrient sensing and blood glucose control. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2015;18(4):381–388. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zietek T., Rath E., Giesbertz P., Ewers M., Reichart F., Weinmüller M., Urbauer E., Haller D., Demir I.E., Ceyhan G.O., Kessler H. Organoids to study intestinal nutrient transport, drug uptake and metabolism - update to the human model and expansion of applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.577656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zietek T., Rath E., Haller D., Daniel H. Intestinal organoids for assessing nutrient transport, sensing and incretin secretion. Sci. Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep16831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizmare L., Boyle C.N., Buss S., Louis S., Kuebler L., Mulay K., Krüger R., Steinhauer L., Mack I., Rodriguez Gomez M., Herfert K., Ritze Y., Trautwein C. Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) surgery during high liquid sucrose diet leads to gut microbiota-related systematic alterations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(3):1126. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]