Abstract

Ureterocele prolapse, an unusual but distinctive finding, may cause voiding difficulty. A 6-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital after his mother discovered that he tapped his lower abdomen when his urinary stream was interrupted during voiding. Voiding cystourethrography indicated a ureterocele prolapse causing the intermittency of voiding; therefore, transvesicoscopic ureteral reimplantation with ureterocelectomy was performed and the voiding consequently improved. However, this condition would not have been diagnosed had the unusual voiding behavior gone unnoticed. Therefore, diagnosing congenital bladder obstructions could be challenging if a patient adapts to a voiding difficulty.

Keywords: Ureterocelectomy, Ureterocele prolapse, Voiding cystourethrography, Voiding intermittency

Abbreviations: UFM, uroflowmetry; VCUG, voiding cystourethrography

1. Introduction

Ureteroceles represent variants of an ectopic ureter, with cystic dilation of the distal ureter located either within the bladder or spanning the bladder neck and urethra.1

Most ureteroceles are detected through prenatal ultrasonography and specifically by identifying hydronephrosis.1 Although infection remains a significant clinical manifestation of ureteroceles,2 abnormalities may not be diagnosed postnatally if there are few subjective symptoms.

Here, we report a case of ureterocele in a 6-year-old male patient who managed intermittent voiding through the unusual behavior of tapping the lower abdomen while urinating.

2. Case presentation

A 6-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital when his mother discovered his behavior of tapping his lower abdomen when his urinary stream was interrupted during voiding. The patient had a history of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder but took no medications. Additionally, the patient was afebrile and had normal vital signs. His urinalysis test results were normal. Abdominal ultrasonography showed no hydronephrosis but indicated a dilated right lower ureter with a cystic structure in the bladder, suggestive of a ureterocele (Fig. 1A and B). No obvious abnormalities were found when observing his voiding behavior, such as the tapping of the lower abdomen, as reported by his mother. Uroflowmetry (UFM) revealed a bell-shaped curve (maximum flow rate, 23.6 mL/s; average flow rate, 10.5 mL/s; voided volume, 121.3 mL); however, bladder ultrasonography showed post-void residual urine. Intravenous pyelography performed at the referring hospital showed bilateral single-system ureters with a dilated right lower ureter and a round defect in the bladder. A dimercaptosuccinic acid scan revealed no differential renal function (right kidney, 51.8%; left kidney, 48.2%).

Fig. 1.

Abdominal ultrasonography findings at the first visit

(A) Transverse plane abdominal ultrasonography showing a ureterocele (white arrowhead).

(B) Sagittal plane abdominal ultrasonography showing a dilated right ureter (black arrowhead) behind the bladder.

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) was performed for a definitive diagnosis. Initially, a defect was observed on the right side of the bladder when a contrast agent was injected through a 6-F catheter (Fig. 2A). VCUG in a standing position revealed no urethral obstruction or vesicoureteral reflux; however, the bladder defect reappeared during the middle stage of voiding (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, the urinary stream was interrupted, and the urethra became invisible when the defect moved to the bladder neck and prolapsed into the urethra (Fig. 2C). Based on the VCUG findings, we concluded that the ureterocele caused bladder outlet obstruction.

Fig. 2.

Voiding cystourethrography findings

(A) The defect (arrow) is observed slightly to the right in the bladder by injecting a contrast medium of 50 mL from a 6-F catheter in the supine position.

(B) Voiding cystourethrography performed in a standing position showed no urethral obstruction (arrowhead) or vesicoureteral reflux; however, the defect (arrow) reappeared and moved to the bladder neck mid-voiding.

(C) The moment the defect (arrow) had prolapsed into the urethra, the contrast medium within the urethra flowed out and the urethra was no longer visible.

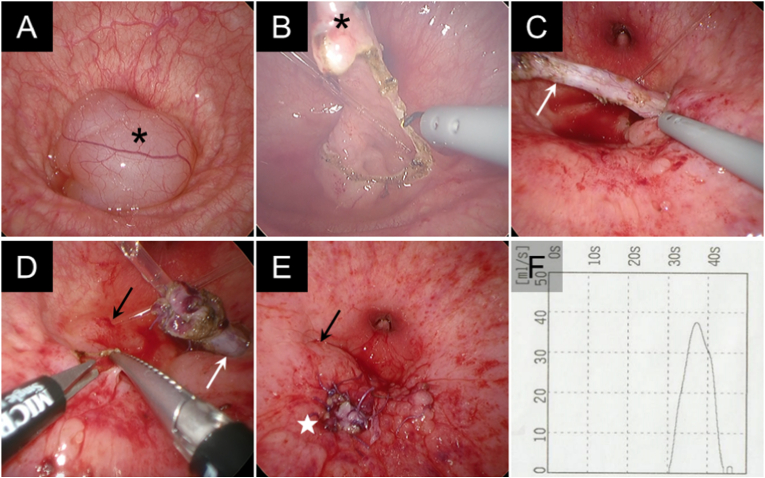

Therefore, to treat the bladder outlet obstruction, transvesicoscopic ureteral reimplantation with ureterocelectomy was performed. Transvesicoscopic findings showed the ureterocele at the bladder neck, obscuring the internal urethral orifice (Fig. 3A). A 5-cm-long 8-F catheter was inserted into the right ureter as a marker to prevent accidental damage to the right orifice. The ureterocele was resected using a monopolar hook (Fig. 3B), and the right ureter was dissected (Fig. 3C). At the site of the new ureteral orifice (above the left ureteral orifice) (Fig. 3D), a submucosal tunnel was created using scissor forceps, and the right ureter was drawn gently through the tunnel. Subsequently, a ureteroneocystostomy was performed using interrupted 4-0 and 5-0 absorbable sutures, and the bladder mucosa was repaired using 5-0 absorbable sutures (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Transvesicoscopy toward the bladder neck (A–E) and postoperative uroflowmetry findings (F) (A) The ureterocele (asterisk) is located in the bladder neck.

(B) The ureterocele (asterisk) was resected using a monopolar hook. A 5-cm-long 8-F catheter is inserted in the right ureter.

(C) The right ureter (white arrow) was dissected using the monopolar hook.

(D) The site of the newly created ureteral orifice and submucosal tunnel using scissor forceps. The white and black arrows indicate the right ureter and left ureteral orifice, respectively. A 5-cm-long 5-F catheter is inserted in the left ureter.

(E) The bladder mucosa was repaired after performing a ureteroneocystostomy. The star indicates the new ureteral orifice.

(F) Postoperative uroflowmetry showing a bell-shaped curve.

A postoperative UFM also showed a bell-shaped curve (maximum flow rate, 37.6 mL/s; average flow rate, 21.6 mL/s; voided volume, 318.5 mL) (Fig. 3F), and bladder ultrasonography after voiding showed no residual urine. Three years postoperatively, the intermittency of voiding had resolved.

3. Discussion

In this case, VCUG successfully showed the ureterocele prolapse into the bladder neck, and the contrast medium within the urethra flowed out when the urinary stream was interrupted in a series of voiding. To our knowledge, this is the first report of VCUG showing a ureterocele prolapse that caused intermittent voiding.

Most ureteroceles are detected through prenatal ultrasonography and only through identifying hydronephrosis.1 The most common manifestations of ureteroceles are urinary tract infections, and rarely, bladder outlet obstruction by a ureterocele prolapse occurs.2,3 Moreover, ureteroceles that present with sudden cessation of the urinary stream while voiding in childhood are exceedingly rare.3

In this case, the ureterocele was successfully diagnosed and treated because of the mother's observation of the patient's behavior of tapping his lower abdomen when his urinary stream was interrupted during voiding. Urinary stream interruption due to a ureterocele prolapse might begin after potty training. It was speculated that shaking his bladder by tapping his lower abdomen resumed voiding by releasing the ureterocele prolapse into the urethra; however, the situation was not actually observed. This patient had learned to control the intermittency of voiding by tapping the lower abdomen. It has been suggested that patients with congenital bladder outlet obstruction are unlikely to experience voiding difficulties compared with patients with acquired dysuria.4

Although ureterocele prolapse is frequently due to an ectopic ureterocele,3 our patient presented with prolapse of a simple ureterocele. VCUG findings showed that the ureterocele was not sufficiently large to be pushed by the wall of the bladder dome and had migrated to the bladder neck, causing bladder outlet obstruction. Our patient did not tap the lower abdomen while voiding during the preoperative UFM at the first visit, the VCUG, and the postoperative UFM; therefore, he apparently controlled the intermittency of voiding by tapping the lower abdomen to only resume voiding when the urinary stream was interrupted with a large amount of residual urine.

4. Conclusion

In this case, the ureterocele prolapse was discovered because of the patient's unusual behavior of tapping the lower abdomen to manage the intermittency of voiding. Furthermore, patients may not explicitly complain of voiding difficulties since they could be accustomed to the obstruction if the bladder outlet obstruction is congenital.

Consent

Informed consent for publication was provided by the patient's parent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Stanasel I., Peters C.A. In: Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. twelfth ed. Partin A.W., Dmochowski R.R., Kavoussi L.R., et al., editors. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2021. Ectopic ureter, ureterocele, and ureteral anomalies; pp. 798–825. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diard F., Eklöf O., Lebowitz R., Maurseth K. Urethral obstruction in boys caused by prolapse of simple ureterocele. Pediatr Radiol. 1981;11:139–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00971815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shetty B.P., John S.D., Swischuk L.E., Angel C.A. Bladder neck obstruction caused by a large simple ureterocele in a young male. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:460–461. doi: 10.1007/BF02019067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishio H., Mizuno K., Kato T., Maruyama T., Yasui T., Hayashi Y. A case of posterior urethral valve identified in an older child by straining to void. Urol Case Rep. 2021;40 doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2021.101886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]