Abstract

Pharmaceutical cocrystals, which contain at least one active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), are still an attention-grabbing field for researchers. Two or more discrete molecules unite together by non-covalent bonds, e.g., hydrogen, Van der Waals, and π⋯π bonds. Those bonds are strong enough to stack molecules in solid form lattice, and thus possessing the stability of crystal material, concurrently, non-covalent bonds are weak enough to dissociate when dissolving in water. Therefore, cocrystal delivers drug as a ‘ready-to-be absorbed’ neutral molecule. Besides, it affects many physicochemical properties, e.g., stability, compressibility, etc. The literature is full of publications that discuss pharmaceutical cocrystals screening and evaluation. This review spots the light on all cocrystals that contain antibiotic (AB) drugs which mentioned in the literature to our knowledge. Focusing on their reported properties like solubility, intrinsic dissolution rate (IDR), stability against humidity/light, powder flowability, compressibility and bioactivity and how they get improved compared to parent AB. Although not many publications imply antimicrobial activity studies in their work, a thorough investigation of how AB cocrystal is affecting bacteria is a persisted necessity. Bacterial ability to develop resistance to known ABs is increasing, making them no longer-efficient. Antibacterial resistance should provoke scientists to use cocrystal modification features to overcome it. This review highlights, classifies and compares all studied AB cocrystals. In addition, it urges research labs, which are interested in cocrystallization, to fill the gap of confronting antimicrobial resistance in their future work.

Keywords: Cocrystal, Antibiotics, Antibacterials, Antimicrobial resistance, Nitrofurantoin, Linezolid, Sulfonamides, Fluroquinolones, Ciprofloxacin, Norfloxacin

Highlights

-

•

Many antibiotic classes members have successful cocrystal.

-

•

Antibiotic cocrystals have unique properties like solubility, dissolution rate, stability, etc.

-

•

Sulfonamides are the majority of published antibiotic cocrystals.

-

•

Few papers study the influence of cocrystallization on antibacterial activity.

-

•

More in-vivo studies are needed.

Cocrystal; Antibiotics; Antibacterials; Antimicrobial Resistance; Nitrofurantoin; Linezolid; Sulfonamides; Fluroquinolones; Ciprofloxacin; Norfloxacin.

1. Introduction

Cocrystal is a crystalline solid form that unites two or more hetero-molecules in the same lattice by non-covalent bonds, e.g., hydrogen bonds, Van der Waals bonds and π⋯π bonds, which easily break upon dissolution [1]. In fact, hydrogen bond is the most common and favorable interaction in defining cocrystal due to their good strength and spatial-directional freedom compared to other non-covalent bonds [2]. If at least one of the cocrystal components was a drug molecule, it, then, can be referred to as pharmaceutical cocrystal. The other “partner” component is called coformer, and it is usually a member of Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) group of materials [3]. The most known regulatory organisations: Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA), presented their regulatory classification of cocrystal to distinguish it from other solid forms of a substance, i.e., salts, solvates and hydrates. While FDA treats cocrystal as a new polymorph of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) rather than a new drug [4], the EMA considers it as a new form of the same API, as salt or solvate, that needs validation if it has different characterisations [5]. Figure 1 summarizes solid forms classification according to homogeneity of components.

Figure 1.

Available forms that a solid API can be exist in.

Although cocrystal field has been well studied throughout the last decade of 20th century worldwide [6], it is still an appealing aspect to researchers due to its various application in chemistry in general [7] and in pharmaceutical industry in special [1, 8, 9]. There are always API molecules to cocrystallize, various methods to try, and many chemical candidates to act as coformers, and that makes cocrystallization always attractive. Although coformers can be any organic molecule that has a complementary synthon to form hydrogen bonds with the API molecule, like amino acids [10] and carboxylic acids, it must be either food additives, listed as Generally Regarded as Safe (GRAS) or even a different API molecule [2, 3]. Besides, when a neutral organic molecule, e.g., API, cocrystallizes with organic/inorganic salt the results will be ionic cocrystal or in other name, salt cocrystal [11]. Contrariwise, a non-covalent interaction would be binding a drug salt and a neutral coformer molecule to form a salt cocrystal [12].

Cocrystal tailors the parent molecule characterisations so it gives, in general, different solubility, permeability, bioavailability, efficacy and stability against humidity and/or light [9], in addition to modification on flowability, compressibility, and compaction behavior [6]. As well as increasing effectiveness of fertilizers in agriculture e.g., urea-catechol cocrystal [13, 14], and more safe-handling in explosives [15],

Some pharmaceutical cocrystals have successfully gained FDA approval and reached the market commercially; i.e., Depakote® is a marketed drug of sodium valproate-valproic acid cocrystal [9], Entresto® is a cocrystal of valsartan and sacubitril (angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor), Suglat® which is a cocrystal of iprogliflozin and L-proline for treatment of type 2 diabetes [6] and Lexapro® is a cocrystal of escitalopram oxalate with oxalic acid for depression and anxiety [16]. However, the regulations for pharmaceutical cocrystals issued by the FDA and EMA need greater international harmonization and agreement to promote the development of pharmaceutical cocrystals.

Although the mechanism of cocrystallization is not exactly well defined, it is agreeable that the integration in functional groups between molecules entities to form hydrogen bonds is the basis of crystal engineering, as introduced by Etter [17] and Desiraju [7]. Since that, many attempts to predict the suitable coformers and narrowing the list of choices in order to save time and efforts have been endeavored. As summarized by Khalaji et al. [18] Fábián utilized molecular complementarity method to statically analyze the data on cocrystal from the Cambridge Structural Database. Shape and polarity of molecules have the biggest influence among other molecular properties [19]. On the other hand, Galek et al. presented the Logit Hydrogen-bonding Propensity (LHP) survey method, which calculates the propensity of hydrogen bond formation between cocrystal pair [20]. Meanwhile, molecular electrostatic potential surfaces calculation method was developed by Musumeci et al. introducing ΔE parameter, which expresses a factor for evaluating cocrystallization probability [21]. Additionally, Mohammad et al., introduced Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSPs) calculations, which sums up the energy of intermolecular bonds and the affinity between the pair of targeted cocrystal [22, 23]. Furthermore, most multicomponent crystals contain acids and bases can be divided into salts and cocrystals according to the position of the proton revealed by single crystal X ray diffraction. pKa rule was extensively studied by Cruz-Cabeza to correlate it with the proton transfer in the solid state, and a linear relationship between ΔpKa (pKa [protonated base] – pKa [acid]) and the probability of proton transfer between acid-base pairs was reported. ΔpKa must be < −1 in order to increase the probability of non-ionized acid-base complexes (cocrystals) over 90% of situations, while ΔpKa > 3 will yield salts due to complete proton transfer [24]. However, ΔpKa alone shouldn't be the only criteria when searching for successful coformers. Childs et al. mentioned many cases that ΔpKa predictive ability is actually poor in the range of 0–3 (the gray region), where: “complexes between acids and bases can still form, although they can be salts or cocrystals or can contain shared protons or mixed ionization states that cannot be assigned to either category”, that denotes the importance of focusing on molecular complementary and crystallization environment, e.g., solvent, temperature and time of reaction [25]. Another example is reported for sulfamethazine-saccharin solid complex. This pair have ΔpKa = 0.45 when evaporating the mixture from acetonitrile, chloroform, ethanol, or isopropanol, a salt phase is obtained, but if the used solvent was much polar (methanol or methanol/water) a cocrystal is resulted [26].

Antibiotics (AB) are wide category of APIs that have the ability to stop growth or to kill bacteria. It can be classified by mechanism of action, spectrum of activity or chemical structure [27]. Like other APIs, most of AB have solubility, absorption and stability hindrances in addition to increasing ability to develop resistance by bacteria [28].

Crystal engineering has been applied on AB drugs to overcome previously mentioned problems by turning AB molecule into salt, hydrate, solvate or even using different polymorphs. Cocrytsallization was one of the used tricks, too. Improving antibacterial properties compared to the parent drug, e.g., (genistein: 4,4′-bipyridine) cocrystalwhich was reported for its improved solubility thus better antibacterial efficacy than parent genistein [29]. Proflavine-AgNO3 and Proflavin-CuCl ionic cocrystals prepared by mechanochemical method showed enhancing antibacterial activity against E. coli, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus [30]. Amoxicillin trihydrate was purified easily and efficiently when the impurity 4-hydroxyphenylglycine was cocrystallized with either of picolinic acid, lysine, leucine or isoleucine, compared to classical solution purification technique [31].

After the misuse of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections in humans, as well as in animals and plants, an urgent search for ways to overcome microbial resistance has been an important demand [32]. Researchers have been working either on exploring new molecules that would act as antibiotics, or on manipulating already known antibiotic molecules by producing them as polymorphs, salts, solvates and cocrystals in order to improve their efficacy [33].

The literature is full of reviews that thoroughly discuss cocrystal topic from many points of view. But this work aims to highlight all studies of antibiotic cocrystal to date. Their structures, method of preparation, physicochemical properties modification, overcoming bacterial drug-resistance and their antibacterial efficacy compared to parent AB would be discussed thoroughly. Table 1 sums up all AB cocrystals in this review article.

Table 1.

Antibiotic cocrystals reported in the literature.

| Antibiotic | Coformer | Cocrystallization method | Resulted solid form | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norfloxacin | Isonicotinamide | Slow evaporation solution | Cocrystal | [34] |

| Succinic acid | " | Salt | [34] | |

| Malonic acid | " | " | [34] | |

| Maleic acid | " | " | [34] | |

| Sebacic acid | " | Salt cocrystal | [35] | |

| Azeliac acid | " | " | [35] | |

| Norfloxacin saccharinate | Saccharin | Liquid Assisted grinding | " | [36] |

| Ciprofloxacin | Thymol | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [33] |

| Carvacrol | " | " | [33] | |

| Nicotinic acid | Neat grinding and liquid assisted grinding | " | [37] | |

| Isonicotinic acid | " | " | [37] | |

| Fumaric acid | " | Salt | [38] | |

| Maleic acid | " | " | [38] | |

| Adipic acid | " | " | [38] | |

| Barbituric acid | Solvent evaporation | Salt cocrystal | [39] | |

| Levofloxacin | Stearic acid | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [40] |

| Na Saccharine | " | " | [40] | |

| Metacetamol | Cogrinding and heating | " | [41] | |

| Phthalimide | Solvent evaporation | " | [42] | |

| Pefloxacin | Oxalic acid | Solvent-drop grinding followed by solution crystallization | Salt cocrystal | [43] |

| Fumaric acid | " | " | [43] | |

| Glutaric acid | " | " | [43] | |

| Sparfloxacin | 4-Hydroxy methyl benzoate | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [44] |

| Ethyl benzoate | " | " | [44] | |

| Propyl benzoate | " | " | [44] | |

| Isopropyl benzoate | " | " | [44] | |

| Nitrofurantoin | Urea | Liquid assisted grinding | Cocrystal | [45, 46] |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | " | " | [46, 47] | |

| Nicotinamide | " | " | [46] | |

| Citric acid | " | " | [46] | |

| L-proline | " | " | [2, 46] | |

| Vanillic acid | " | " | [46] | |

| Vanillin | " | " | [46] | |

| Melamine | Solvent evaporation | " | [48] | |

| Linezolid | Benzoic acid | Liquid assisted grinding | Cocrystal | [49] |

| p-Hydroxy benzoic acid | " | " | [49] | |

| Protochatechuic acid | " | " | [49] | |

| γ-Resorcylic acid | " | " | [49] | |

| Gallic acid | " | " | [49] | |

| p-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) | " | " | [49] | |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA) | " | " | [18] | |

| Sulfaguanidine | Thiobarbutaric acid | Solvent-evaporation | Cocrystal | [50] |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | Liquid assisted grinding | " | [50] | |

| Sulfamethoxazole | Trimethoprim | Solvent evaporation | Salt | [51] |

| " | Seal-heating | Cocrystal | [52] | |

| " | Slurry method | " | [53] | |

| " | Milling | " | [54] | |

| Sulfadimidine | Trimethoprim | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [51, 55] |

| 2-Aminobenzoic acid (Anthranilic acid) | " | " | [51] | |

| 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) | " | " | [51] | |

| 4-Aminosalicylic acid (PAS) | " | " | [51] | |

| Aspirin | " | " | [51] | |

| Salicylic acid | Cogrinding | " | [51] | |

| Benzoic acid | " | " | [51] | |

| Benzene-1,2-dicarboxylic acid (o-phthalic acid, PHA) | " | " | [51] | |

| 4-Chlorobenzoic acid (p-chlorobenzoic acid, PCL) | " | " | [51] | |

| Sulfamethoxypyridazine | Trimethoprim | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [56] |

| 5-methoxysulfadiazine | Aspirin | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [57] |

| Sulfamethazine | Indole-2-carboxylic acid | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [58] |

| 2,4-Dinitrobenzoic acid | " | " | [58] | |

| Nicotinamide | Microwave-assisted slurry conversion | " | [59] | |

| Salicylic acid | " | " | [59] | |

| Anthranilic acid | " | " | [59] | |

| Benzamide | " | " | [59] | |

| Aspirin | " | " | [59] | |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | Solvent evaporation | " | [60] | |

| 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | " | " | [60] | |

| 3,4-Dichlorobenzoic acid | " | " | [60] | |

| Sorbic acid | " | " | [60] | |

| Fumaric acid | " | " | [60] | |

| 1-Hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | " | " | [60] | |

| Benzamide | " | " | [60] | |

| Picolinamide | " | " | [60] | |

| 4-Hydroxybenzamide | " | " | [60] | |

| 3-Hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | " | " | [60] | |

| p-Aminobenzoic acid | Grinding, solvent evaporation | " | [61] | |

| Theophylline | " | " | [62] | |

| Saccharin | Solvent evaporation | Salt or cocrystal | [26] | |

| Sulfamerazine | Anthranilic acid | Microwave-assisted slurry conversion | Cocrystal | [59] |

| Salicylamide | " | " | [59] | |

| Sulfamethiazole (syn., sulfamethizole) | L-proline | Solvent evaporation | Cocrystal | [63] |

| Saccharine | Liquid assisted grinding and solvent evaporation | " | [64] | |

|

" | " | [64] | |

| 4-Aminobenzoic acid | " | " | [65] | |

| Adipic acid | " | " | [65] | |

| Vanillic acid | " | " | [65] | |

| 4-Aminobenzamide | " | " | [65] | |

| 4,4′-Bipyridine | " | " | [65] | |

| Suberic acid | " | " | [65] | |

| Oxalic acid | " | Salt | [65] | |

| Sulfathiazole | Amantadine HCl | Liquid assisted grinding | Cocrystal | [66] |

2. Fluroquinolones

2.1. Norfloxacin

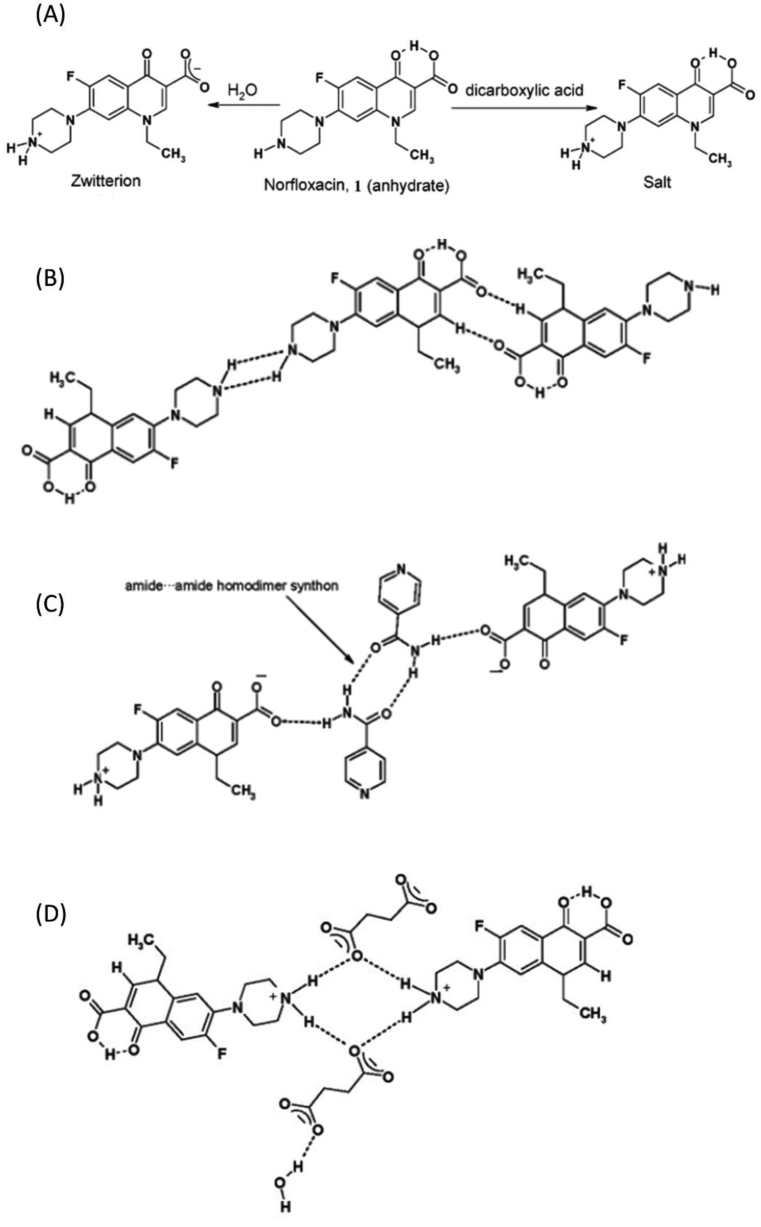

Norfloxacin (NOR) available forms to year 2008 were three polymorphs (A, B, C), an amorphous, hydrates and a methanol hydrate [67] It is also known as a zwitterion molecule (Figure 2(A)), which explains its low solubility at pH = 7 aqueous solutions (its isoelectric point) and made it logical to think of a way to keep NOR unionized and at the same time water soluble for better bioavailability [68]. On the other hand, crystallization process between NOR and dicarboxylic acids (e.g., succinic, malonic and maleic acids) yields salts due to full proton transfer from the acids COOH group to piperazinyl ring N atom of NOR as shown in Figure 2(B) and (D) [34]. In 2006, Basavoju et al. reported a new solid state of NOR that is connected by hydrogen bonds with isonicotinamide (ISNIC) to form a solid cocrystal [34]. It was prepared by slow evaporation solution method, using CHCl3 as a solvent. Using single crystal X ray diffraction (ScXRD), powder Xray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transformation Infra-red (FTIR) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) techniques, so the structure of NOR:ISNIC cocrystal as 1:1 hetero-synthon lattice was determined, where NOR exists in zwitterion state and form (N–H⋯O) bonds with the coformer molecule (Figure 2(C)). That design reflected in an improved solubility of NOR (about 3 times better) compared to NOR anhydrous form. However, salts of NOR with carboxylic acids in the same paper showed solubility increase about 20–45 times better than the anhydrous NOR form. The researchers described this phenomenon by a change in the crystal energy (ΔHsolvation) of the cocrystal, and the increased tendency in salts to ionize and dissolve [34].

Figure 2.

(A) Zwitterionic form of Norfloxacin and the protonated form by dicarboxylic acid (e.g., succinic acid). (B) Molecular diagram showing interactions in the Norfloxacin crystal. (C) Molecular diagram showing interactions in the Nor:IsNIC cocrystal. (D) Molecular diagram showing interactions in Nor:Succinic acid salt. Reprinted with permission from [34]. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

Another cocrystal of NOR was reported by Velaga et al. (2008). It consisted of a saccharinate salt of NOR with saccharine molecule (SAC) as a coformer resulting in (NOR saccharinate:SAC) salt cocrystal (Figure 3(1)). It was obtained by dispersing 1:1 NOR and SAC in a few drops of water and the slurry was heated for full dissolution. The mixture was left to dry slowly in ambient condition. The resulted solid after two days was both the NOR saccharinate dihydrate salt and NOR saccharinate-SAC dihydrate cocrystal, which were both characterized by DSC, PXRD and ScXRD. The authors reported that they were able to scale-up the salt, whereas they obtained the cocrystal for once and never got it again [36]. Recently, two ternary molecular ionic cocrystals (salt cocrystals) have been reported by O'Malley et al. [35] the detailed structure is shown in Figure 3(2 and 3). Using azeliac acid (az) and sebacic acid (seb) as coformers yielded (nor+)2 (az2−)·az·4H2O and (nor+) (seb−)·nor·H2O. Depending on the solvent applied in solution evaporation method and liquid assisted grinding, different solid forms have been obtained.

Figure 3.

(1) Saccharin and saccharinate ions interacting with norfloxacin and water molecules via O–H⋯O, O–H⋯N–, N–H⋯O, N+–H⋯O and N+–H⋯N– interactions. Reprinted with permission from [36]. Copyright 2008 Elsevier. (2) (nor+)2 (az2−)·az·4H2O: red, nor + A; blue, nor + B; green, az2−; and purple, az; and (3) (nor+) (seb−)·nor·H2O: red, nor+; blue, nor; green, H2O. Adapted from [35].

2.2. Ciprofloxacin

In 2020, two cocrystals of neutral ciprofloxacin (CIP) have been reported with thymol (Thy) and carvacrol (Car). Their antimicrobial activity against E. coli were about twice the one that belongs to CIP or to the physical mixture of CIP and coformers [33] Figure 4(A) and (B) shows the structure of CIP:Thy4 and CIP:Thy2 cocrystals, respectively.

Figure 4.

(A) Hydrogen bond interactions between ciprofloxacin and the thymol molecules in crystalline CIP·THY4. (B) Ciprofloxacin and the thymol molecules in crystalline CIP·THY2. Reprinted with permission from [33]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Nicotinic acid (NA) and isonicotinic acid (INA) were also used as coformers with CIP as reported by de Almeida et al., and the structures have been confirmed using DSC, thermal gravimetry-differential thermal analysis (TG-DTA), FTIR and XRD analysis, after preparation via mechanochemical method (neat and liquid assisted grinding by ethanol). The solubility study revealed better aqueous solubility than the parent drug (Figure 5 A and B), taking into consideration that CIP is in its neutral form which is more bioavailable than the commercial HCl salt type [37].

Figure 5.

Solubility study results of pure ciprofloxacin CIP, and two cocrystals with nicotinic acid NCA and isonicotininc acid INCA in pure water (A) and pH = 6.8 (B) Adapted from [37]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier. Dissolution profile at 28 °C for salts and pure CIP in pH = 1.2 (C) and in pH = 6.8 (D). Reprinted with permission from [38]. Copyright 2015 Elsevier.

Common carboxylic acid like fumaric, maleic and adipic acid formed ionic bonds with CIP yielding salts, due to ΔpKa values > 4 between ciprofloxacin piperazine fragment (pKa = 8.74) and studied acids, indicating the occurrence of proton transfer and salt formation. These salts showed different dissolution rates compared to CIP HCl or pure CIP in different pH aqueous solution. CIP was more soluble than salts in acidic medium (pH = 1.2), but in pH = 6.8 CIP salts have dissolved better and faster than parent CIP [38] (Figure 5 C and D). That can be attributed to the isoelectric point per component and the degree of ionization could be reached in each pH medium. Another research on CIP salts have proposed a “salt cocrystal” when crystalized with a specific amount of barbituric acid that allows both the ionized and nonionized barbituric acid molecules to crystallize concurrently [39]. Here, intermolecular hydrogen bonds N–H⋯O and O–H⋯O formed by water molecules and the components ions make a stable 3D network.

2.3. Levofloxacin

Levofloxacin (LV) exists as hydrated crystal. By utilizing different coformers, different properties resulted. Bandari et al. tried to cocrystallize LV in order to mask the bitter taste and to enhance its solubility using stearic acid. On the other hand, using sodium saccharine as a coformer improved dissolution rate of LV without influencing its palatability [40]. A drug-drug cocrystal of LV and metacetamol (LV:AMAP) was produced via cogrinding and heating method for full dehydration, that surpassed the parent drugs physiochemically, especially during dissolution tests, hygroscopicity, physical and humidity stability (Figure 6 (I, II)) in addition to photostability, due to hydrogen bonds formation between the hydroxyl group of metacetamol and the N-methyl piperazine group of LV [41]. Meanwhile, another drug-drug of LV and phthalimide (LV:PTH) has recently been reported with better dissolution rate and antibacterial efficiency in-vitro [42]

Figure 6.

(I) Water sorption/desorption isotherm of Levofloxacin hemihydrate and Levofloxacin:Metacetamol (LVFX:AMAP) cocrystal at 25 °C. (II) XRPD patterns of (a) Levofloxacin hemihydrate marked with blue circles and (b) LVFX:AMAP cocrystal marked with pink square, stored at each stressed condition for 4 weeks. Reprinted with permission from [41]. Copyright 2019 Elsevier.

2.4. Pefloxacin

Pefloxacin is a zwitterion molecule that is encountered as a neutral hexahydrate stable crystal structure because of C–H⋯O and C–H⋯F intermolecular hydrogen bonds. It has been synthesized as five salts, two salt hydrates, and three salt cocrystals depending on the ΔpKa rule. Salt cocrystal was found to occur with oxalic acid, fumaric acid and glutaric acid. Single crystal X-Ray diffraction revealed the type of interactions contributing in stability of the reported salt cocrystals, i.e., N+–H⋯O–, O–H⋯O, C–H⋯O, C–H⋯F, and π–π stacking. Those novel cocrystals have shown better solubility and dissolution rate compared to pure pefloxacin [43].

2.5. Sparfloxacin

Sparfloxacin (SPX) is a zwitterion fluoroquinolone antibiotic that has solubility and bioavailability problems, which were overcome by cocrytsallization with paraben esters, i.e., 4-hydroxy methyl benzoate (MBZ), ethyl benzoate (EBZ), propyl benzoate (PBZ) and isopropyl benzoate (IBZ) resulting in four cocrystals of 1:1 stoichiometry and two cocrystal hydrates (SPX–EBZ–HYD and SPX–PBZ–HYD) of 1:1: 3 stoichiometry. These cocrystals keep SPX in its neutral form (as illustrated in Figure 7(I)), which is better for absorption, concurrently, increases its dissolution rate when compared to SPX neutral trihydrate (Figure 7(II)) [44].

Figure 7.

(I) Proposed mechanism of (a) neutral to zwitterionic transformation of SPX in the presence of water. (b) Conversion of the zwitterionic to neutral form of SPX in the presence of the paraben coformer. (II) Intrinsic dissolution rate curves of neutral sparfloxacin, zwitterionic SPX and its cocrystals in pH 7 buffer. Readapted from reference [44]. Copyright 2016 Royal Society of Chemistry.

3. Nitrofurantoin

Alhalaweh et al. described pharmacokinetic features of nitrofurantoin (NTF) cocrystals with urea, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, nicotinamide, citric acid Figure 8(b), L-proline, vanillic acid and vanillin using liquid-assisted grinding (LAG) method. Figure 8(a) shows NTF molecular structure. Better solubility and stability in ethanol compared to parent NTF were reported, but aqueous stability was weak where cocrystals tend to disassociate immediately to the metastable α form NTF [46]. Pandey et al., predicted the NF:L-prolin cocrystal formation by computational approach and confirmed it through experiments [2] and so did Khan et al. with urea [45] and melamine Figure 8(c) [48]. Another study by Shukla et al. reported cocrystals of NTF:4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HBA) where interaction happens through N–H⋯O–H bond between imide N–H of nitrofurantoin and phenolic –OH of 4-HBA, Figure 8(d), these bonds are confirmed not only by IR spectroscopy and PXRD but also by natural bond orbital (NBO) and Quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analyses [47].

Figure 8.

Chemical structure of Nitrofurantoin (NTF) (a), Crystal structure of NTF:citric acid showing the interactions between the citric acid molecules and NTF (b). Reprinted with permission from [46]. Copyright 2012 The Royal Society of Chemistry. The optimized geometry of the ground state of the NTF-melamine-H2O (monomer) (c) Reprinted with permission [48]. Copyright 2019 Elsevier, and Optimized structure of NF-4Hydroxy Benzoic acid (4HBA) (monomer model) (d). Reprinted with permission [47]. Copyright 2018 the Royal Society of Chemistry.

4. Linezolid

Linezolid (LIN) belongs to oxazolidinone class. It is a poor soluble antibiotic which has two enantiotropic polymorphic forms. The stable form II transforms to the metastable form III by heating to 120–140 °C for appropriate time [69]. So, it is important to find a way to maintain the stable form of LIN during processes containing elevated temperature. Cocrystals via liquid assisted grinding of LIN and benzoic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, 2,6-dihydroxybenzoic acid (γ-resorcylic acid, 2,6-DHBA), 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (protocatechuic acid, 3,4-DHBA) and gallic acid (GA, 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) have melting points lower than the transition phase temperature from II form to III form. Although there is structure similarity between those coformers, there are differences of number, localization and strength of the interactions in each cocrystals, and that will reflect on energetic stability and physicochemical performance (solubility of LIN-benzoic acid was 10% more than LIN, while it was 43% for LIN:4-DHBA. The π⋯π interaction stabilizes the structure. It was also found that the additional hydroxyl group of p-hydroxy benzoic acid offers a possibility of saturating more hydrogen-bond acceptor sites [49].

5. Sulfonamides

As Caira mentioned in his review article, Sulfa drugs (e.g., sulphathiazole, sulfamethoxazole, sulfadimidine, etc.) have been used as model molecules for extensive study on crystal polymorphism since early 1970s. This group of molecules contains many possible hydrogen donors and receptors that allow hydrogen bonds to form, which gives the supramolecular motifs the ability to re-arrange differently according to crystallization conditions (Figure 9). He has also gathered all the work of his research team in sulfonamides from 1980s till 2007 [51].

Figure 9.

Chemical structures of common sulfonamide drugs. Reprinted with permission from [51]. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

5.1. Sulfaguanidine

Abidi et al., 2018 have reported in their work [50] the formation of two new solid form of the antibiotic sulfaguanidine (SG) with thiobarbutaric acid (TBA) and 1,10 Phenanthroline (PT), they referred to them as cocrystals. Solvent evaporation method was used with acetonitrile and methanol to obtain the hydrate cocrystal (SG:TBA:H2O), and liquid assisted grinding method with ethanol to obtain (SG:PT) cocrystal.

DSC, XRD, FTIR and ScXRD analysis were all applied to confirm the new solid form structure. Abidi et al. performed a biological study as an important aspect to the antibiotic cocrystal evaluation. They have compared the antibacterial effect and the cytotoxicity on red blood cells between SG base and (SG:TBA:H2O), (SG:PT) cocrystals, then reported that the latter have higher potential anti-bacterial growth by about two folds in addition to a noticeable decrease in hemolytic affect due to functional groups engagement in cocrystal interactions which leads to reduced interaction with red blood cells [50].

5.2. Sulfamethoxazole

Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and trimethoprim (TMP) complex (SMX-TMP) was reported by Caira, 2007 as a salt due to complete proton transfer [51] (Figure 10). The exact arrangement of protons in intermolecular hydrogen bonds have been confirmed by Nakai et al. [70] however, when Zaini et al. applied seal-heating method to the SMX-TMP mixture, the resulted solid phase was confirmed to be a drug-drug cocrystal using PXRD and DSC techniques [52]. Later on, more studies by Zaini's team were performed to get SMX-TMP cocrystal via slurry technique [53], and milling method [54].

Figure 10.

Salt formation between sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and trimethoprim (TMP). Reprinted with permission from [51]. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

5.3. Sulfadimidine

Sulfadimidine (SDMD) yields a drug-drug cocrystal solid phase with TMP by two N–H⋯N hydrogen bonds with no proton transfer when prepared by LAG method with methanol. The methanol molecule is attached to an O atom of the sulfonamido group through a strong O–H⋯O interaction and does not play a significant role in stabilizing the crystal packing (Figure 11) [71]. In order to apply pKa rule [24], it is found that SDMD pKa acid = 7.65, and TMP pKa base = 7.12, that makes Δ pKa = - 0.53 which is < 0 and definitely lead to cocrystal, whereas in case of sulfametrole (pKa acid = 4.8), ΔpKa of sulfametrol-TMP pair = 2.32 units (it is in the gray region). The experimental single crystal X-ray diffraction data confirmed the full proton transferring, thus salt formation [72].

Figure 11.

Cocrystal formation between sulfadimidine (SDMD) and trimethoprim. Reprinted with permission from [51]. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

Serrano et al. were able to obtain sulfadimidine:para-aminosalycilc acid (SDMD:PAS) cocrystal by different methods in order to carry out a comparison study between the resulted cocrystal habits. As polymorphism in cocrystal phase was confirmed [73], the effect of crystal habit of the same cocrystal was notably evaluated through micromeritics tests [74], dissolution studies, in addition to antibacterial activity assessment [75]. Liquid assisted grinding resulted in small polyhedral crystals with improved solubility and bioactivity than sulfadimidine base with high compressibility index and poor flowability, while cocrystals by solvent evaporation and spray drying methods yielded a plate-like (good flowability) or sphere-like (better compaction) habits that tend to aggregate in aqueous solution due to their hydrophobic surfaces [74]. Aggregates were confirmed by shadowgraph imaging during dissolution test using flow-through apparatus. Cocrystal aggregation can be attributed to the lower solubility and limited antibacterial activity [75]. Additional coformers were reported in Caira's, 2007 review [51] and can be reached in Table 1.

5.4. Sulfa methoxy pyridazine

Sulfa methoxy pyridazine (SMPD), gave an anhydrous cocrystal with TMP (SMPD:TMP) via solution crystallization from methanol, and a hydrate cocrystal when crystallizing from water (SMPD:TMP:1.5H2O) [56]. These findings have a pharmaceutical technology importance due to reported clotting and pouring problems in the mass prepared for suppositories marketed as Velaten®. This problem was interpreted by the formation of SMPD:TMP cocrystal and easily hydration during manufacturing process, which gave the needle-shape hydrate cocrystals (SMPD:TMP:1.5H2O) [76]. That phenomenon spotted the light on the importance of studying the potential interaction between all ingredients in formulation before proceeding to manufacture.

5.5. Sulfamerazine

Ahuja et al. have reported two cocrystals of sulfamerazine (SMR) by microwave assisted slurry conversion sulfamerazine:anthranilic acid (SMR:AA) and sulfamerazine: salicylamide (SMR:SA). Here, the microwave as a heating source during slurry crystallization appears to increase the rate of cocrystal formation compared to liquid assisted grinding. A slurry with acetonitrile was irradiated by microwave for 4 min at 70 °C. The tunable electromagnetic field appears to promote solid-state transformation. Scale-up can be increased from 0.2 g to 20 g with the same result. The new cocrystals have enhanced dissolution rates compared to parent materials [59].

5.6. Sulfamethazine

Ghosh et al. mentioned ten coformers that were successfully able to form cocrystals with sulfamethazine. They were either carboxylic acids or amides, i.e., 4-hydroxybenzoic acid PABA, 2,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4-dichlorobenzoic acid, sorbic acid, fumaric acid, 1-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid, benzamide, picolinamide, 4-hydroxybenzamide and 3-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid [60]. Whereas, using p-aminobenzoic acid as a coformer was established by Pan et al., 2019 via slow evaporation method and an increasing in solubility and in vitro antibacterial activity have been reported (Figure 12). Although Sulfamethazine has 59.2% inhibition rate (using concentration = 500 μg/mL) against E. coli, the cocrystal revealed a 2-fold higher than sulfamethazine (50 and 100 μg/mL) [61]. The synergistic antibacterial effect was probably because of the improved solubility of cocrystal samples. Previous studies also indicated that the dissolution performance would be an important factor in the antibacterial activity [75].

Figure 12.

Antibacterial effect of Sulfamethazine (STH), p-Amino Benzoic Acid (PABA), physical mixture and STH−PABA cocrystal on E. coli. Different letters within figure denote a significant difference (p < 0.05). Reprinted with permission from [61]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

Lately, Ahuja et al. have applied a new method to prepare cocrystals and reported a new cocrystal of sulfamethazine with nicotinamide, as well as four coformers that were also reported previously by other researchers, i.e., salicylic acid, anthranilic acid, benzamide and aspirin. Those solid forms were prepared by microwave assisted slurry conversion method which was proven to be faster than the classical liquid crystallization methods due to the heating energy provided via microwave. This technique appeared to be more effective than normal heating. Analytical tests were applied to confirm the new solid form in addition to performing experiments for solubility enhancement validation [59]. As mentioned earlier in this work, Fu et al., reported sulfamethazine-saccharin solid complex as either salt or cocrystal depending on the solvent of crystallization; if it is less polar (e.g., acetonitrile), a salt will be formed. But if the solvent is more polar (methanol or methanol/water), the result will be cocrystal phase. Both solid mixtures have the same main intermolecular bonds sites but different location of acidic proton. The solvent-mediated phase transformation study reveals that SMT-SAC cocrystal has less Gibbs free energy at ambient conditions, which explains the enhanced solubility of the salt form [26]. Figure 13 shows the structure of SMT-SAC salt (a) and SMT-SAC cocrystal (b).

Figure 13.

The main intermolecular hydrogen bonding sites in (a) SMT-SAC salt and (b) SMT-SAC cocrystal. (Symmetry code: (i) −1+ x, y, z.). Adapted from [26]. Copyright 2016 Royal Society of Chemistry.

5.7. Sulfamethiazole

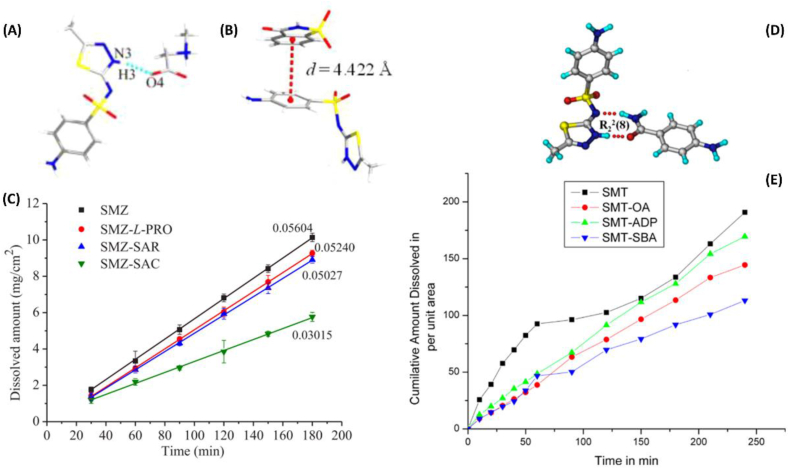

Sulfamethiazole (SMZ) molecule has two H bond donors: amine NH2 and imine NH; and five H bond acceptors: two sulfonyl O atoms, thiazolidine N and S, and imidine N. so it is capable of forming cocrystals with suitable partners. SMZ has been successfully formed cocrystals with L-proline [63], sarcosine and saccharin (Figure 14 A and B) [64]. Unlike usual situation, those cocrystals exhibits lower solubility than SMZ itself, which was pharmaceutically preferred in order to reduce elimination time and raise in vivo bioavailability of the drug. Figure 14(C) shows the reduced dissolution rate of the cocrystal phases [64].

Figure 14.

(A) Crystal structure of Sulfamethizole-sarcosine (SMZ−SAR) (1:1) cocrystal. (B) Crystal structure of Sulfamethizole-saccharin (SMZ−SAC) (1:1) cocrystal. (C) IDR profiles of SMZ and cocrystals in pH 1.2 HCl medium at 37 °C. (D) SMT−ABA (p-Aminobenzamide) cocrystal is assembled via two-point hydrogen bond synthon between amide−thiadiazidol groups through N–H⋯O and N–H⋯N hydrogen bonds in an R22 (8) ring motif. (E) Intrinsic dissolution rate curves of SMT, SMT-ADP (adipic acid), SMT-SBA (suberic acid), and SMT-OA (oxalic acid) in pH 1.2 HCl medium. Measurement time is 4 h. A, B, and D are adapted from [64]. C and E are adapted from [65].

Another study confirmed designing six cocrystals of sulfamethizole (which is a synonym for sulfamethiazole) with each of 4-aminobenzoic acid, adipic acid (ΔpKa [SMZ-ADA] = 2.75), vanillic acid, 4-aminobenzamide (Figure 14D), ,4′-bipyridine and suberic acid (Δ pKa [SMZ-SBA] = 2.95), and one salt with oxalic acid (Δ pKa [SMZ-OA] = 0.59) in using liquid assisted grinding. Those reported molecular complexes also exhibited intrinsic dissolution rate (IDR) lower than initial SMZ, which would be useful in enhancing bioavailability of SMZ that has short half-life as shown in Figure 14(E). Researchers have explained this decrease in dissolution by the tighter close packing and strong H-bonds interactions in the crystal lattice, although SMZ-OA is salt and OA alone is very soluble, but the salt has the lowest solubility and may be it is correlated with the highest melting point of oxalic acid compared to the lower melting cocrystals [65].

Recently, a sulfathiazole-amantadine hydrochloride cocrystal (drug-drug cocrystal) was reported by Wang et al. Its structure was determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction, in addition to solubility, penetrability, antibacterial activity study. An enhancement in physicochemical properties compared to sulfathiazole has been established with the cocrystal solid form. Better solubility of the cocrystal reflects on better antibacterial effect, i.e., larger quantity of drug interacting with bacterial cell wall, and improved permeability means more ability to penetrate the cytomembrane even on resistant strains that are used studied in the published work of Wang et al [66].

6. Conclusions

Cocrytsallization is a profound way to tailor antibiotic (AB) features as desired by the formulator. Many researches have proven that AB cocrystals have better solubility, bioavailability, stability permeability or antibacterial activity than the parent drug, but while this review was prepared, the literature concerning AB cocrystal is found to be lacking for these important points: (1) comprehensive research that begins with a specific AB cocrystal screening, characterizing its structure, physicochemical properties, stability tests, and ends with anti-bacterial efficacy validation compared to the parent drug. (2) Comparison research between different cocrystals of the same AB, and exploring the effect of different coformers on their properties. (3) Formulate AB cocrystals in suitable dosage forms and evaluate their features. And the most demanding (4) an evaluation of new cocrystals' ability to overcome antimicrobial resistance. We recommend interested researchers to imply these previous points in their works in order to make them more comprehensive and effective.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Almarsson O., Zaworotko M.J. Crystal engineering of the composition of pharmaceutical phases. Do pharmaceutical co-crystals represent a new path to improved medicines? Chem. Commun. (Camb). 2004:1889–1896. doi: 10.1039/b402150a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandey J., Prajapati P., Shimpi M.R., Tandon P., Velaga S.P., Srivastava A., Sinha K. Studies of molecular structure, hydrogen bonding and chemical activity of a nitrofurantoin-l-proline cocrystal: a combined spectroscopic and quantum chemical approach. RSC Adv. 2016;6:74135–74154. [Google Scholar]

- 3.V Trask A. An overview of pharmaceutical cocrystals as intellectual property. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:301–309. doi: 10.1021/mp070001z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FDA; CDER Regulatory classification of pharmaceutical co-crystals, guidance for industry. Food Drug Adm. U.S. Dep. Heal. Hum. Serv. 2018:1–4. https://www.fda.gov/media/81824/download (accessed August 24, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 5.EMA/CHMP/CVMP Reflection Paper on the Use of Cocrystals of Active Substances in Medicinal Products. Eur. Med. Agency. 2015:1–10. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-use-cocrystals-active-substances-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed August 23, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yousef M.A.E., Vangala V.R. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: molecules, crystals, formulations, medicines. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019;19:7420–7438. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desiraju G.R. Crystal and co-crystal. CrystEngComm. 2003;5:466. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavanagh O.N., Croker D.M., Walker G.M., Zaworotko M.J. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: from serendipity to design to application. Drug Discovery Today. 2019;24:796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duggirala N.K., Perry M.L., Almarsson Ö., Zaworotko M.J. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: along the path to improved medicines. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:640–655. doi: 10.1039/c5cc08216a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilborg A., Norberg B., Wouters J. Pharmaceutical salts and cocrystals involving amino acids : a brief structural overview of the state-of-art. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;74:411–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braga D., Grepioni F., Shemchuk O. Organic–inorganic ionic co-crystals: a new class of multipurpose compounds. CrystEngComm. 2018;20:2212–2220. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chierotti M.R., Gaglioti K., Gobetto R., Braga D., Grepioni F., Maini L. From molecular crystals to salt co-crystals of barbituric acid via the carbonate ion and an improvement of the solid state properties. CrystEngComm. 2013;15:7598–7605. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casali L., Mazzei L., Shemchuk O., Honer K., Grepioni F., Ciurli S., Braga D., Baltrusaitis J. Smart urea ionic co-crystals with enhanced urease inhibition activity for improved nitrogen cycle management. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:7637–7640. doi: 10.1039/c8cc03777a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casali L., Mazzei L., Shemchuk O., Sharma L., Honer K., Grepioni F., Ciurli S., Braga D., Baltrusaitis J. Novel dual-action plant fertilizer and urease inhibitor: urea·Catechol cocrystal. Characterization and environmental reactivity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019;7:2852–2859. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer D., Risse B., Schnell F., Pichot V., Klaumünzer M., Schaefer M.R. Continuous engineering of nano-cocrystals for medical and energetic applications. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4–9. doi: 10.1038/srep06575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaikh R., Singh R., Walker G.M., Croker D.M. Pharmaceutical cocrystal drug products: an outlook on product development. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;39:1033–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etter M.C. Hydrogen bonds as design elements in organic chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:4601–4610. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalaji M., Potrzebowski M.J., Dudek M.K. Virtual cocrystal screening methods as tools to understand the formation of pharmaceutical cocrystals—a case study of linezolid, a wide-range antibacterial drug. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021;21:2301–2314. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fábián L. Cambridge structural database analysis of molecular complementarity in cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009;9:1436–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galek P.T.A., Samuel W.D., Allen F.H., Feeder N. 2007. Research Papers Knowledge-Based Model of Hydrogen-Bonding Propensity in Organic Crystals Research Papers; pp. 768–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musumeci D., Hunter C.A., Prohens R., Scuderi S., McCabe J.F. Virtual cocrystal screening. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:883–890. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bashimam M. Hansen solubility parameters : a quick review in pharmaceutical aspect. J. Chem. Pharmaceut. Res. 2015;7:597–599. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammad Amin M., Alhalaweh A., Bashimam M., Almardini M.A., Velaga S. Utility of Hansen solubility parameters in the cocrystal screening. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010:1360–1361. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruz-Cabeza A.J. Acid-base crystalline complexes and the pKa rule. CrystEngComm. 2012;14:6362–6365. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Childs S.L., Stahly G.P., Park A. The Salt−Cocrystal Continuum: the influence of crystal structure on ionization state. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:323–338. doi: 10.1021/mp0601345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu X., Li J., Wang L., Wu B., Xu X., Deng Z., Zhang H. Pharmaceutical crystalline complexes of sulfamethazine with saccharin: same interaction site but different ionization states. RSC Adv. 2016;6:26474–26478. [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Souza Mendes C.D.U., de Souza Antunes A.M. Pipeline of known chemical classes of antibiotics. Antibiotics. 2013;2:500–534. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics2040500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (n.d.) (accessed August 24, 2022)

- 29.Zhang Y.N., Yin H.M., Zhang Y., Zhang D.J., Su X., Kuang H.X. Preparation of a 1:1 cocrystal of genistein with 4,4’-bipyridine. J. Cryst. Growth. 2017;458:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shemchuk O., Braga D., Grepioni F., Turner R.J. Co-crystallization of antibacterials with inorganic salts: paving the way to activity enhancement. RSC Adv. 2020;10:2146–2149. doi: 10.1039/c9ra10353h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsi K.H.Y., Concepcion A.J., Kenny M., Magzoub A.A., Myerson A.S. Purification of amoxicillin trihydrate by impurity-coformer complexation in solution. CrystEngComm. 2013;15:6776–6781. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown E.D., Wright G.D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shemchuk O., D’Agostino S., Fiore C., Sambri V., Zannoli S., Grepioni F., Braga D. Natural antimicrobials meet a synthetic antibiotic: carvacrol/thymol and ciprofloxacin cocrystals as a promising solid-state route to activity enhancement. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020;20:6796–6803. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basavoju S., Boström D., Velaga S.P. Pharmaceutical cocrystal and salts of norfloxacin. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006;6:2699–2708. [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Malley C., McArdle P., Erxleben A. formation of salts and molecular ionic cocrystals of fluoroquinolones and α,ω-dicarboxylic acids. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022;22:3060–3071. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.1c01509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velaga S.P., Basavoju S., Boström D. Norfloxacin saccharinate–saccharin dihydrate cocrystal – a new pharmaceutical cocrystal with an organic counter ion. J. Mol. Struct. 2008;889:150–153. [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Almeida A.C., Torquetti C., Ferreira P.O., Fernandes R.P., dos Santos E.C., Kogawa A.C., Caires F.J. Cocrystals of ciprofloxacin with nicotinic and isonicotinic acids: mechanochemical synthesis, characterization, thermal and solubility study. Thermochim. Acta. 2020;685 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Surov A.O., Manin A.N., Voronin A.P., Drozd K.V., Simagina A.A., Churakov A.V., Perlovich G.L. Pharmaceutical salts of ciprofloxacin with dicarboxylic acids. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2015;77:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golovnev N.N., Molokeev M.S., Lesnikov M.K., Atuchin V.V. Two salts and the salt cocrystal of ciprofloxacin with thiobarbituric and barbituric acids: the structure and properties. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2018;31:e3773. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandari S., Dronam V.R., Eedara B.B. Development and preliminary characterization of levofloxacin pharmaceutical cocrystals for dissolution rate enhancement. J. Pharm. Investig. 2017;47:583–591. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shinozaki T., Ono M., Higashi K., Moribe K. A novel drug-drug cocrystal of levofloxacin and metacetamol: reduced hygroscopicity and improved photostability of levofloxacin. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019;108:2383–2390. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Islam N.U., Umar M.N., Khan E., Al-Joufi F.A., Abed S.N., Said M., Ullah H., Iftikhar M., Zahoor M., Khan F.A. Levofloxacin cocrystal/salt with phthalimide and Caffeic acid as promising solid-state approach to improve antimicrobial efficiency. Antibiotics. 2022;11:797. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11060797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunnam A., Suresh K., Nangia A. Salts and salt cocrystals of the antibacterial drug pefloxacin. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018;18:2824–2835. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunnam A., Suresh K., Ganduri R., Nangia A. Crystal engineering of a zwitterionic drug to neutral cocrystals: a general solution for floxacins. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:12610–12613. doi: 10.1039/c6cc06627e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan E., Shukla A., Jadav N., Telford R., Ayala A.P., Tandon P., Vangala V.R. Study of molecular structure, chemical reactivity and H-bonding interactions in the cocrystal of nitrofurantoin with urea. New J. Chem. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alhalaweh A., George S., Basavoju S., Childs S.L., Rizvi S.A.A., Velaga S.P. Pharmaceutical cocrystals of nitrofurantoin: screening, characterization and crystal structure analysis. CrystEngComm. 2012;14:5078. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shukla A., Khan E., Alsirawan M.B., Mandal R., Tandon P., Vangala V.R. Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, and 13 C SS-NMR) and quantum chemical investigations to provide structural insights into nitrofurantoin–4-hydroxybenzoic acid cocrystals. New J. Chem. 2019;43:7136–7149. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan E., Shukla A., Jhariya A.N., Tandon P., Vangala V.R. Nitrofurantoin-melamine monohydrate (cocrystal hydrate): probing the role of H-bonding on the structure and properties using quantum chemical calculations and vibrational spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;221 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khalaji M., Wróblewska A., Wielgus E., Bujacz G.D., Dudek M.K., Potrzebowski M.J. Structural variety of heterosynthons in linezolid cocrystals with modified thermal properties. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2020;76:892–912. doi: 10.1107/S2052520620010896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abidi S.S.A., Azim Y., Khan S.N., Khan A.U. Sulfaguanidine cocrystals: synthesis, structural characterization and their antibacterial and hemolytic analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018;149:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caira M.R. Sulfa drugs as model cocrystal formers. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:310–316. doi: 10.1021/mp070003j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaini E., Sundani N.S., Azul H. Cocrystal formation between trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole by sealed-heating method. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 2008;64 C490–C490. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zaini E., Sumirtapura Y.C., Soewandhi S.N., Halim A., Uekusa H., Fujii K. Cocrystalline phase transformation of binary mixture of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole by slurry technique. Asian J. Pharmaceut. Clin. Res. 2010;3:26–29. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266208439_COCRYSTALLINE_PHASE_TRANSFORMATION_OF_BINARY_MIXTURE_OF_TRIMETHOPRIM_AND_SULFAMETHOXAZOLE_BY_SLURRY_TECHNIQUE (accessed August 3, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaini E., Sumirtapura Y.C., Halim A., Fitriani L., Soewandhi S.N. Formation and characterization of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim cocrystal by milling process. J. Appl. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017;7:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bettinetti G., Sardone N. Methanol solvate of the 1:1 molecular complex of trimethoprim and sulfadimidine. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1997;53:594–597. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bettinetti G., Caira M.R., Callegari A., Merli M., Sorrenti M., Tadini C. Structure and solid-state chemistry of anhydrous and hydrated crystal forms of the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxypyridazine 1:1 molecular complex. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000;89:478–489. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6017(200004)89:4<478::AID-JPS5>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caira M.R. Molecular complexes of sulfonamides. 3. Structure of 5-methoxysulfadiazine (form II) and its 1:1 complex with acetylsalicylic acid. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 1994;24:695–701. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lynch D.E., Sandhu P., Parsons S. 1 : 1 molecular complexes of 4-amino-N-(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)benzene-sulfonamide (sulfamethazine) with indole-2-carboxylic acid and 2,4-dinitrobenzoic acid. Aust. J. Chem. 2000;53:383–387. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahuja D., Ramisetty K.A., Sumanth P.K., Crowley C.M., Lusi M., Rasmuson Å.C. Microwave assisted slurry conversion crystallization for manufacturing of new co-crystals of sulfamethazine and sulfamerazine. CrystEngComm. 2020;22:1381–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghosh S., Bag P.P., Reddy C.M. Co-crystals of sulfamethazine with some carboxylic acids and amides: Co-former assisted tautomerism in an active pharmaceutical ingredient and hydrogen bond competition study. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011;11:3489–3503. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pan X., Zheng Y., Chen R., Qiu S., Chen Z., Rao W., Chen S., You Y., Lü J., Xu L., Guan X. Cocrystal of sulfamethazine and p -aminobenzoic acid: structural establishment and enhanced antibacterial properties, Cryst. Growth Des. 2019;19:2455–2460. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu J., Rohani S. Synthesis and preliminary characterization of sulfamethazine-theophylline Co-crystal. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;99:4042–4047. doi: 10.1002/jps.22142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li D., Kong M., Li J., Deng Z., Zhang H. Amine–carboxylate supramolecular synthon in pharmaceutical cocrystals. CrystEngComm. 2018;20:5112–5118. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan Y., Li D., Wang C., Chen S., Kong M., Deng Z., Sun C.C., Zhang H. Structural features of sulfamethizole and its cocrystals: beauty within. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019;19:7185–7192. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suresh K., Minkov V.S., Namila K.K., Derevyannikova E., Losev E., Nangia A., Boldyreva E.V. Novel synthons in sulfamethizole cocrystals: structure-property relations and solubility. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015;15:3498–3510. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang L., Bu F., Li Y., Wu Z., Yan C. A sulfathiazole–amantadine hydrochloride cocrystal: the first Codrug simultaneously Comprising antiviral and antibacterial components. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020;20:3236–3246. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roy S., Goud N.R., Babu N.J., Iqbal J., Kruthiventi A.K., Nangia A. Crystal structures of norfloxacin hydrates. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008;8:4343–4346. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takács-Novák K., Noszál B., Hermecz I., Keresztúri G., Podányi B., Szasz G. Protonation equilibria of quinolone antibacterials. J. Pharm. Sci. 1990;79:1023–1028. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600791116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maccaroni E., Alberti E., Malpezzi L., Masciocchi N., Vladiskovic C. Polymorphism of linezolid: a combined single-crystal, powder diffraction and NMR study. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;351:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakai H., Takasuka M., Shiro M. X-ray and infrared spectral studies of the ionic structure of trimethoprim - sulfamethoxazole 1 : 1 molecular complex. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1984;2:1459–1464. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bettinetti G., Sardone N. Methanol solvate of the 1:1 molecular complex of trimethoprim and sulfadimidine. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1997;53:594–597. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Giuseppetti G., Tadini C., Bettinetti G.P. 1:1 Molecular complex of trimethoprim and sulfametrole. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1994;50:1289–1291. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grossjohann C., Serrano D.R., Paluch K.J., O’Connell P., Vella-Zarb L., Manesiotis P., McCabe T., Tajber L., Corrigan O.I., Healy A.M. Polymorphism in sulfadimidine/4-aminosalicylic acid cocrystals: solid-state characterization and physicochemical properties. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015;104:1385–1398. doi: 10.1002/jps.24345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Serrano D.R., O’Connell P., Paluch K.J., Walsh D., Healy A.M. Cocrystal habit engineering to improve drug dissolution and alter derived powder properties. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016;68:665–677. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Serrano D.R.R., Persoons T., Arcy D.M.D., Galiana C., Dea-ayuela A., Healy A.M., D’Arcy D.M., Galiana C., Dea-Ayuela M.A., Healy A.M. Modelling and shadowgraph imaging of cocrystal dissolution and assessment of in vitro antimicrobial activity for sulfadimidine/4-aminosalicylic acid cocrystals. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2016;89:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Giordano F., La Manna A., Bettinetti G.P., Zampa-rutti M. Preformulation studies on suppositories by thermal methods. Boll. Chim. Farm. 1990:160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.