Abstract

Loss of Paneth cells (PCs) and their antimicrobial granules compromises the intestinal epithelial barrier and is associated with Crohn’s disease, a major type of inflammatory bowel disease1–7. Non-classical lymphoid cells, broadly referred to as intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), intercalate the intestinal epithelium8,9. This anatomical position has implicated them as first-line defenders in resistance to infections, but their role in inflammatory disease pathogenesis requires clarification. Identification of mediators that coordinate crosstalk between specific IEL and epithelial subsets could provide insight into intestinal barrier mechanisms in health and disease. Here we show the γδ IEL subset promotes the viability of PCs deficient in the Crohn’s disease susceptibility gene ATG16L1. Using an ex vivo lymphocyte-epithelium co-culture system, we identified apoptosis inhibitor 5 (API5) as a PC-protective factor secreted by γδ IELs. In the Atg16L1-mutant mouse model, viral infection induced a loss of PCs and enhanced susceptibility to intestinal injury by inhibiting secretion of API5 from γδ IELs. Therapeutic administration of recombinant API5 protected PCs in vivo in mice and ex vivo in human organoids harboring the ATG16L1 risk allele. Thus, we identify API5 as a protective γδ IEL effector that masks genetic susceptibility to PC death.

Disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier is a hallmark of Crohn’s disease (CD), an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that often involves debilitating gastrointestinal symptoms and complications. Although immunosuppressive therapies such as antibodies targeting TNFα can be effective, initial treatment fails in approximately 40% of patients and initial responders frequently experience relapse10. Interventions targeting the epithelium would be valuable additions to the clinical armamentarium.

Paneth cells (PCs) are intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) distinguished by their secretory antimicrobial granules and position within the small intestinal (SI) crypts adjacent to Lgr5+ epithelial stem cells11. Investigation of ATG16L1, an autophagy gene linked to CD susceptibility, has supported a link between PCs and intestinal inflammation. Atg16L1 mutant mice and patients with CD homozygous for the ATG16L1T300A risk allele display reductions in the number of PCs with intact granules1. These histologic abnormalities were subsequently shown to have diagnostic and prognostic value, and observed in patients harboring other variants related to the autophagy pathway2–5. Mechanistically, autophagy proteins intersect the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway to prevent intestinal inflammation in mouse models by supporting organelle homeostasis, secretion of the antimicrobial protein lysozyme, and overall viability of PCs6,7,12–14. Understanding the cell-extrinsic signals contributing to PC abnormalities may help determine whether they precede barrier dysfunction or are secondary to inflammation.

We previously demonstrated that PC death in mice with an IEC-specific deletion of Atg16L1 (Atg16L1f/fvillin-Cre; Atg16L1ΔIEC) is dependent on intestinal infection by the single-strand RNA virus murine norovirus (MNV)12,15. In contrast, MNV protects wild-type (WT) mice from chemical and bacterial injury of the gut16,17. WT and Atg16L1 mutant mice display similar viral burden12,15, suggesting that PC defects are not caused by a failure to control MNV, and instead, may reflect immunopathology. Here, we find that MNV acts as an inflammatory trigger in Atg16L1 mutant mice through the intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) compartment. IELs are a group of heterogenous lymphoid cells intercalating the intestinal epithelium8 and include CD4+ and CD8+ T cells harboring the α and β T cell receptor (TCR) dimers and less understood innate-like T cells, such as those that harbor the TCRγ and δ chains (γδIELs)9. γδIELs survey the epithelium for signs of damage18–20 and are protective in a mouse model of colonic injury21. Additionally, γδIELs orchestrate a switch from an antimicrobial to carbohydrate gene expression pattern in the epithelium by suppressing interleukin-22 (IL-22) production from innate lymphoid cells in response to feeding22. Both Celiac disease and CD patients display reductions in γδIEL subsets in the SI23,24, suggesting an anti-inflammatory role. However, how γδIELs prevent SI inflammation has not been established. In this study, we apply our virus-triggered animal model resembling features of CD and an advanced cell culture technique to identify apoptosis inhibitor 5 (API5) as a novel γδIEL effector that enhances the viability of PCs.

MNV impairs the protective function of γδ IELs

The lack of histological defects in WT mice infected with MNV CR6 strain allows investigation of immune-epithelial crosstalk in the absence of overt inflammation or epithelial erosion. We performed intravital imaging of the SI in two independent reporter mice; E8Itomato mice, which labels the vast majority of IEL populations25, and TCRδGFP mice, which labels γδIELs25. CD8α-expressing lymphoid cells including γδIELs associated with the epithelium increased their number and inter-epithelial movements (“flossing”19) while slowing their movement upon MNV infection (Supplementary videos 1–4, Extended Data Fig. 1a, b), suggesting that IELs respond to MNV. Persistent MNV infection leads to differentiation of CD8+ T cells that are retained in the SI without losing functionality26. We found that MNV infection increases the absolute number of IELs in the SI of WT C57BL/6 mice, especially CD4+ and CD8+ TCRαβ+ populations without inducing changes in γδIEL numbers (Extended Data Fig. 2a–f). Single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-Seq) analysis of CD45+ and CD103+ cells sorted from the IEL compartment did not reveal obvious differences in cell type composition between naïve and MNV-infected mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a–c). Because scRNA-Seq has a limited capacity to detect low abundance transcripts including cytokines, we performed flow cytometric analysis and found that MNV infection increased the proportion and number of TNFα+ and/or IFNγ+ TCRαβ+ (αβ) IELs, but did not impact the number of cytokine-producing γδIELs (Extended Data Fig. 2g–l).

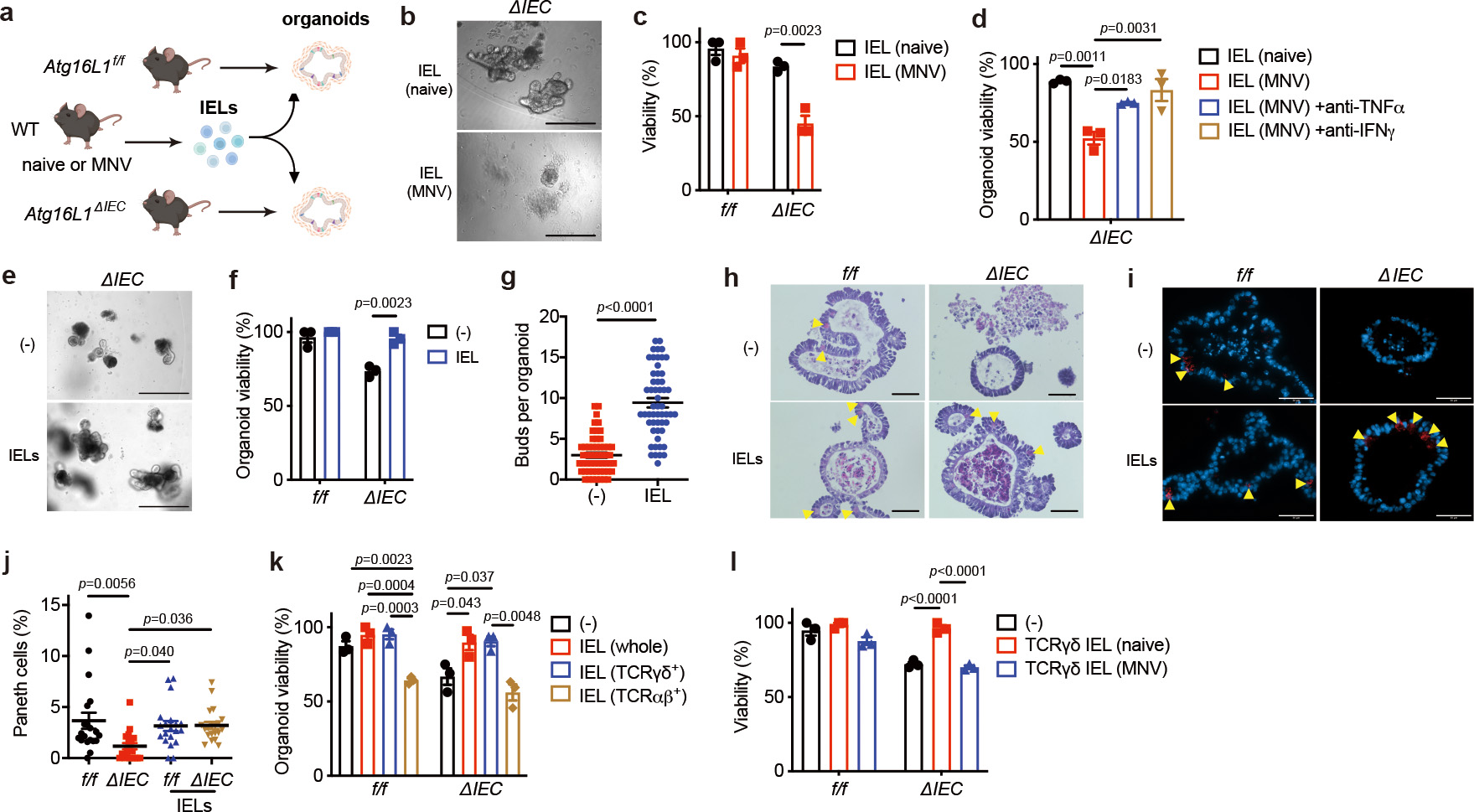

Given that the deleterious effects of MNV in Atg16L1 mutant mice are dependent on TNFα and IFNγ12,15, we tested whether we could recapitulate the viral trigger ex vivo by co-culturing IELs from MNV-infected WT mice with intestinal organoids, a 3D cell culture model in which IECs are differentiated from primary epithelial stem cells (Fig. 1a)14. SI organoids generated from Atg16L1ΔIEC mice but not control Atg16L1f/f mice displayed impaired viability when co-cultured with IELs harvested from MNV-infected mice, and this cytolytic effect was attenuated by blocking TNFα or IFNγ (Fig. 1b–d). IELs harvested from the naïve host did not impair organoid viability (Fig. 1b, c). Rather, we unexpectedly noticed that Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids co-cultured with IELs from the naïve host displayed improved viability and morphology (budding) compared with Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids grown in isolation (Fig. 1e–g). Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids display fewer PCs than Atg16L1f/f organoids12. However, H&E-staining and lysozyme immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy indicated that the addition of IELs from naïve mice to Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids restored PC numbers to control levels (Fig. 1h–j). By sorting IEL subtypes from naïve mice, we identified TCRγδ+ lymphocytes as the protective subset (Fig. 1k). Localization of γδIELs was not altered by MNV infection (Extended Data Fig. 1c–d). However, γδIELs from MNV-infected mice failed to improve the viability of Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids (Fig. 1l), suggesting that viral infection alters their functional properties. Thus, γδIELs from naïve mice protect IECs including PCs in the SI, and MNV infection not only induces an inflammatory phenotype in αβIELs that leads to tissue damage, but also impacts the mobility and tissue protective function of γδIELs.

Fig. 1 |. γδIELs restore Paneth cells and improve viability of ATG16L1-deficient intestinal organoids.

a, Schematic of the organoid-IEL co-culture system. Small intestinal (SI) organoids were derived from Atg16L1f/f (f/f) and Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC) mice, and IELs were separately harvested from naive or MNV CR6 (persistent strain)-infected wild-type (WT) mice. b, c, Representative images (b) and viability (c) of SI organoids cultured for 48 hours with 1 × 105 IELs from naïve or MNV-infected WT mice. Scale bar 400 μm. d, Viability of SI organoids from ΔIEC mice cultured for 48 hours with 1 × 105 IELs harvested from naïve or MNV-infected WT mice and treated with 0.2 μg/ml anti-TNFα or 20 ng/ml anti-IFNγ antibody. e, f, Representative images (e) and viability (f) of f/f and ΔIEC organoids cultured for 48 hours with 1 × 105 IELs from naïve WT mice or media control. Scale bar 400 μm. g, Bud number per organoid in (e). h-j, Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images (h), immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy images of lysozyme (red) and DAPI (blue) (i), and frequency of Paneth cells (PCs) normalized to total IECs (j) in organoids cultured for 48 hours with 1 × 105 IELs from naïve WT mice. Scale bar 50 μm. Arrowheads indicate PCs. k, l, Viability of f/f and ΔIEC organoids cultured for 48 hours with 1 × 105 whole (unsorted), 5 × 104 TCRγδ+, or 3 × 104 TCRαβ+ IELs from naïve WT mice (k) or 5 × 104 TCRγδ+ IELs from naïve or MNV-infected WT mice (l). Amount of TCRγδ+ and TCRαβ+ IELs added to the culture reflect their approximate numbers in the unsorted fraction. Intestinal crypts to generate organoids and IELs were harvested from 3 mice per genotype/condition. Viability assays were performed in triplicate. Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (c, f, g). An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (d, j, k, l). Data points in (c), (d), (f), (k), and (l) represent organoid viability in each well, and data points in (g) and (j) represent individual organoids. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

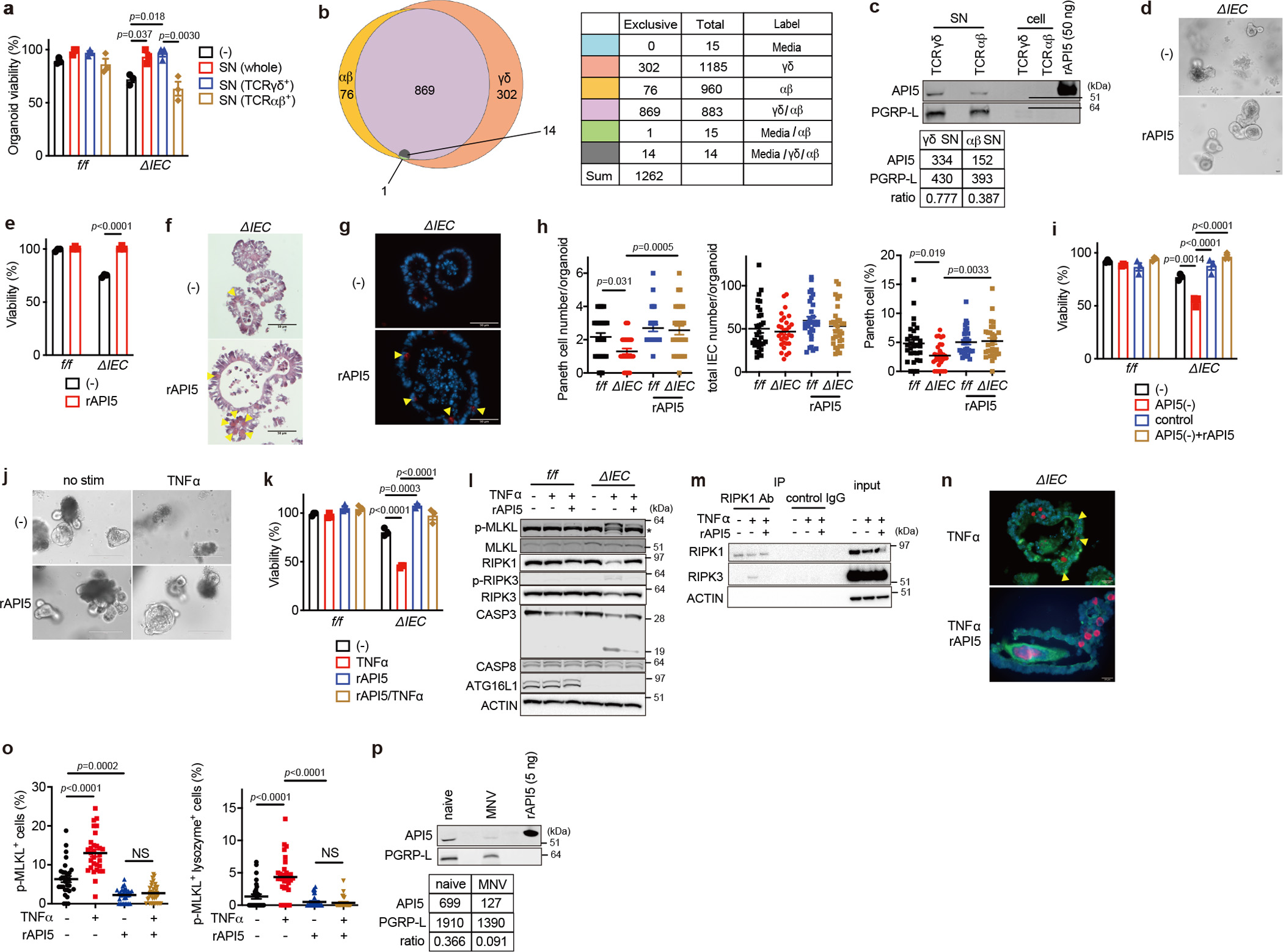

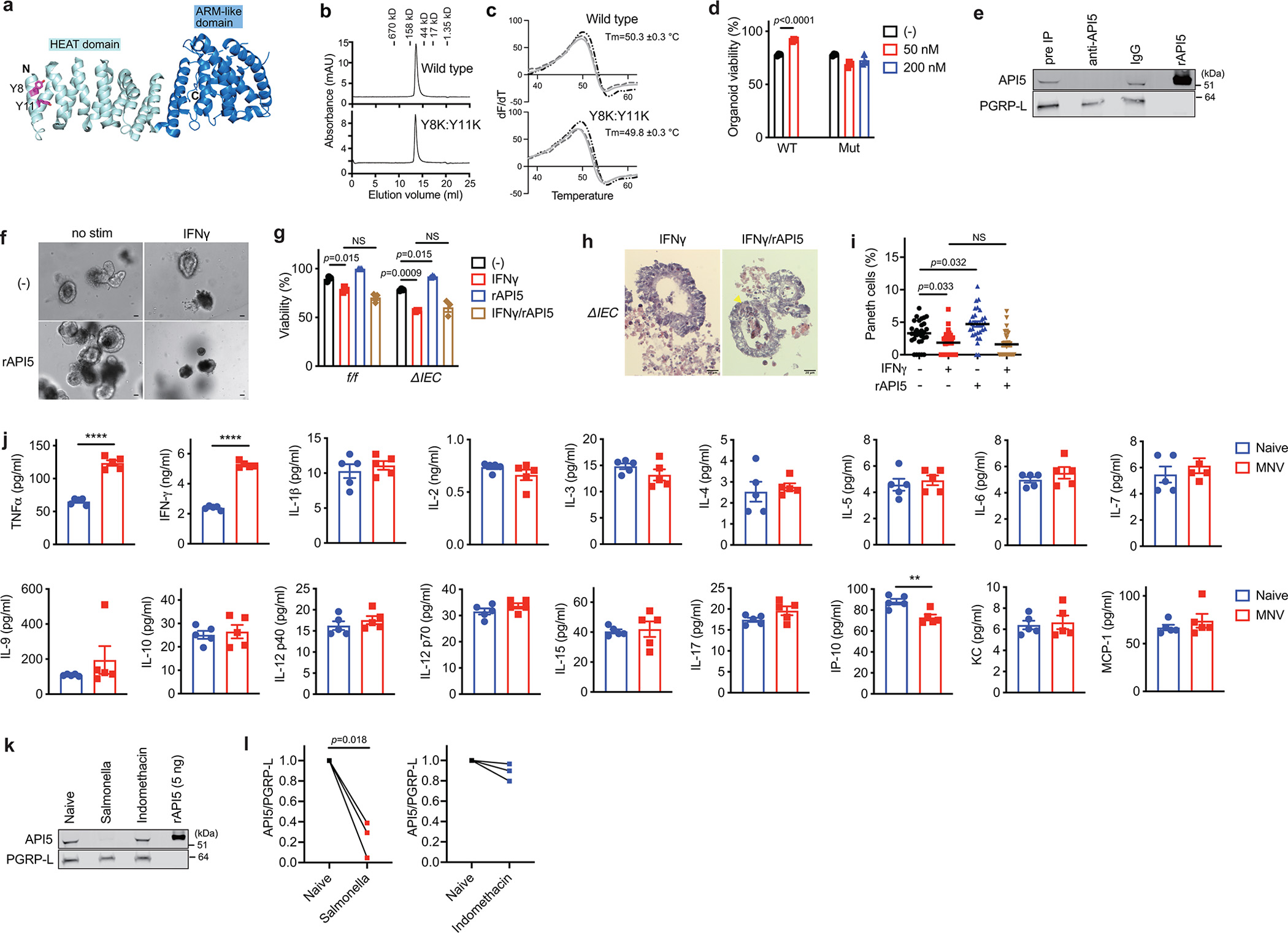

γδIEL-derived protein API5 protects ATG16L1-deficient organoids

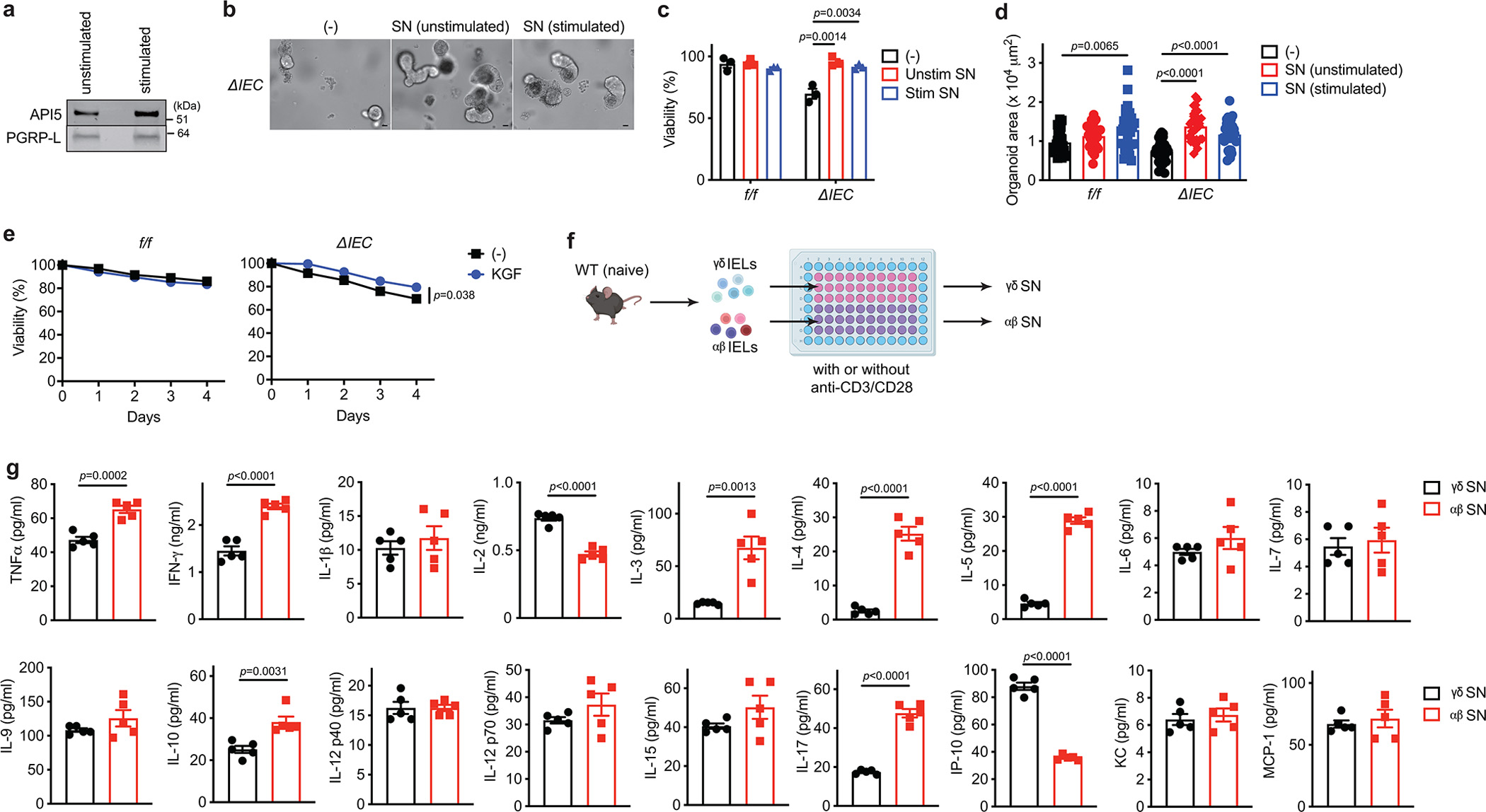

Supernatant from γδIELs (with or without anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation) restored Atg16L1ΔIEC organoid viability, implicating soluble factors (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 4a–d). Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), which mediates protection of the colon by γδIELs21, only modestly increased viability (Extended Data Fig. 4e). We performed liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) proteomics on supernatant from γδ and αβIEL cultures, which detected 1262 proteins in total, with 302 exclusively in the γδIEL secretome (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 4f). Among the 46 proteins with high peptide spectral matches (PSM) (Table S1), we focused on API5 (also known as AAC-11 and FIF) because this under-investigated molecule was previously shown to block cell death and induce proliferation in cell lines when overexpressed intracellularly27–29. API5 does not contain a discernable secretion signal sequence and was not previously known to be produced by lymphocytes. We confirmed the presence of API5 in the supernatant of γδIELs by immunoblotting, which was detected at higher levels than αβIEL supernatant while the secreted loading control PGRP-L30 was similar (Fig. 2c). In addition to less API5, the supernatant from αβIELs contained higher levels of TNFα and IFNγ compared with γδIELs (Extended Data Fig. 4g).

Fig. 2 |. API5 secreted from γδIELs promotes viability of ATG16L1-deficient organoids.

a, Viability of SI organoids from Atg16L1f/f (f/f) and Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC) mice cultured for 48 hours with supernatant (SN) from whole (unsorted), TCRγδ+, and TCRαβ+ IELs from naïve WT mice. b, Venn diagram of proteins detected in LC/MS. c, Western blot (WB) analysis of SN and cell lysate from TCRγδ+ and TCRαβ+ IELs sorted from naïve WT mice and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. Values obtained through densitometric analyses of SN samples shown below. d, e, Representative images (d) and viability (e) of f/f and ΔIEC organoids cultured ± 50 nM recombinant API5 (rAPI5) for 48 hours. Scale bar 25 μm. f, g, h, Representative H&E images (f), IF images of lysozyme (red) and DAPI (blue) (g), and quantification (h) of PC and total IEC number per organoid cultured ± 50 nM recombinant API5 (rAPI5) for 48 hours. Scale bar 50 μm. i, Viability of organoids cultured for 48 hours with indicated SN samples supplemented with growth factors ± 50 nM rAPI5. See Extended Data Fig. 6e for additional information. j, k, Representative images (j) and viability (k) of organoids stimulated ± 20 ng/ml TNFα for 48 hours after pretreatment with 50 nM wild-type rAPI5 for 3 days. Scale bar 200 μm. l, WB analysis of cell death-related proteins of organoids cultured in the presence or absence of rAPI5 for 3 days and stimulated ± 20 ng/ml TNFα for 2 hours on day 3. * denotes non-specific bands. m, WB analysis of RIPK1 and RIPK3 in lysates of ΔIEC organoids cultured and stimulated as in (l), followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-RIPK1 for 6 hours. n, o, Representative IF images (n) of phospho (p)-MLKL (green), lysozyme (red), and DAPI (blue) in ΔIEC organoids stimulated ± 20 ng/ml TNFα for 4 hours after pretreatment with 50 nM wild-type rAPI5 for 3 days, and quantification of p-MLKL+ cells (o, left) and p-MLKL+ lysozyme+ cells (o, right) in organoids. Arrowheads indicate p-MLKL+ lysozyme+ cells. Scale bar 20 μm. p, WB analysis of γδ SN harvested from naïve or MNV-infected WT mice stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. Intestinal crypts for organoids were harvested from 3 mice per genotype. Viability assays were performed in triplicate. An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (a, h, i, k, o) Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (e). Data points in (a), (e), (i), and (k) represent organoid viability in each well, and data points in (h) and (o) represent individual organoids. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

We next produced a recombinant human API5 protein (rAPI5). Mouse and human API5 display >99% amino acid sequence identity in the predominantly helical structured region, which is followed by a short less conserved C-terminal region predicted to be disordered (Extended Data Fig. 5a)31. An inspection of the API5 structure identified a cluster of surface-exposed Tyr resides in the N-terminal HEAT domain, suggestive of a protein-protein interaction interface32. Therefore, we generated a variant that disrupts this surface (Y8K:Y11K) as a control protein. Both proteins were monomeric and stable (Extended Data Fig. 5b, c).

Adding wild-type rAPI5 (rAPI5WT) but not rAPI5Y8K:Y11K to the culture medium was sufficient to increase Atg16L1ΔIEC organoid viability and PC numbers (Fig. 2d–h and Extended Data Fig. 5d). Depleting API5 from γδIEL-supernatant using an anti-API5 antibody led to loss of protection of Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids, and adding rAPI5 back to the supernatant restored protection (Fig. 2i and Extended Data Fig. 5e). Adding TNFα to Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids triggers cell death in a manner dependent on necroptosis signaling molecules RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL12–14. rAPI5 conferred complete resistance to TNFα-mediated killing of Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids and reduced phospho (p)-MLKL and p-RIPK3, hallmarks of necroptosis, as well as cleavage of caspase-3, a hallmark of apoptosis (Fig. 2j–l). Also, adding rAPI5 to TNFα-treated Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids led to decreased RIP1-RIPK3 interaction and p-MLKL+ cells, particularly lysozyme+ cells (Fig. 2m–o).

In our earlier experiment, API5 was detected in supernatant from αβIELs along with cytotoxic cytokines (Fig. 2c). rAPI5 did not protect Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids and their PCs against IFNγ, suggesting that elevated IFNγ can interfere with the protective function of API5 (Extended Data Fig. 4g, 5f–i). Also, we detected lower levels of API5 and higher levels of inflammatory cytokines including IFNγ in the supernatant of γδIELs harvested from MNV-infected mice (Fig. 2p and Extended Data Fig. 5j). Therefore, conditions that increase cytotoxic cytokine levels and reduce API5 are associated with loss of protection. Salmonella enterica Typhimurium infection, which affects the dynamics of γδIELs in vivo19, also suppressed API5 secretion (Extended Data Fig. 5k, l). In contrast, indomethacin treatment, which induces SI injury in a manner dependent on γδIEL migration20, did not alter API5 secretion (Extended Data Fig. 5k, l). These results indicate that interference with API5 secretion by γδIELs may be a broader property of enteric infectious agents.

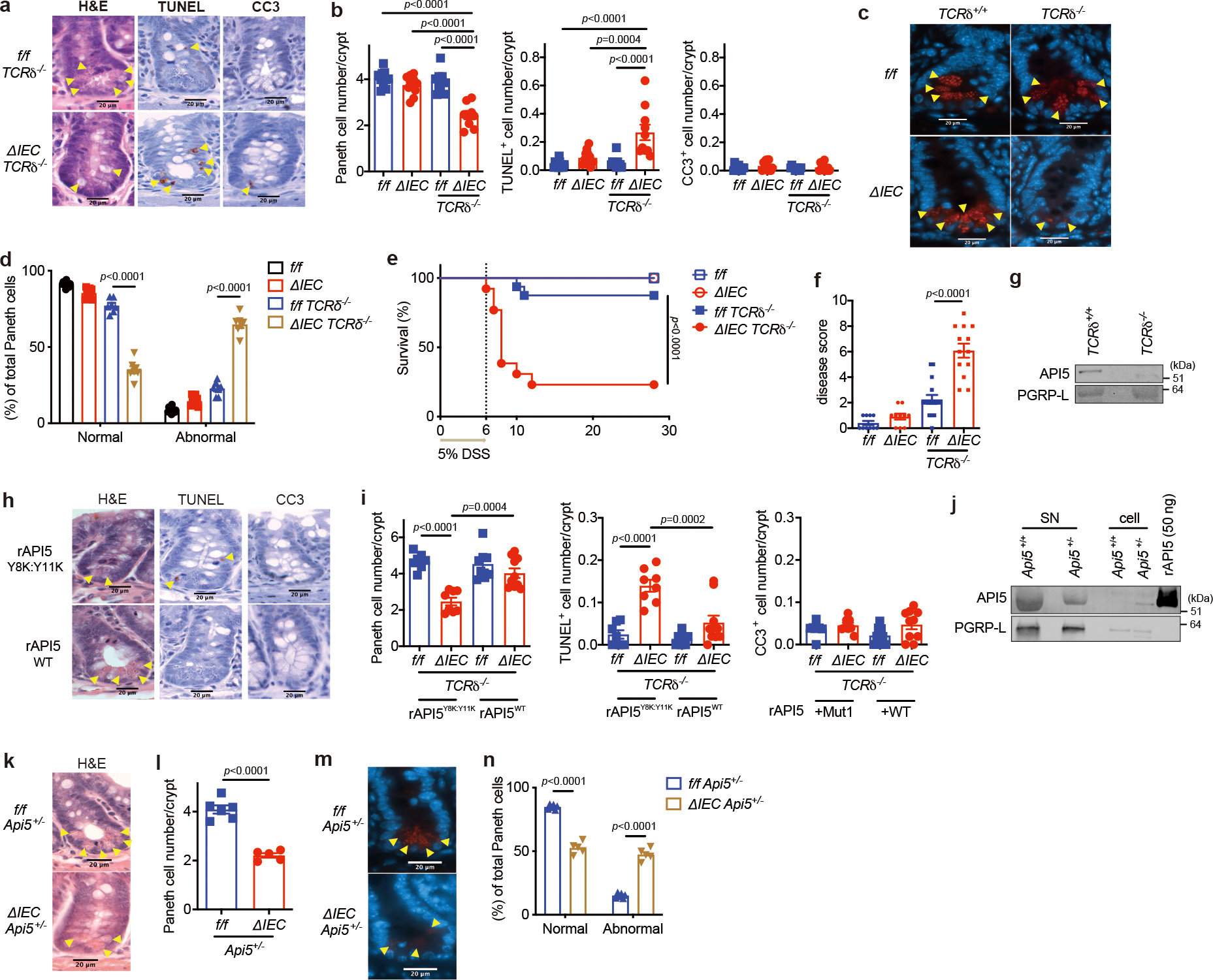

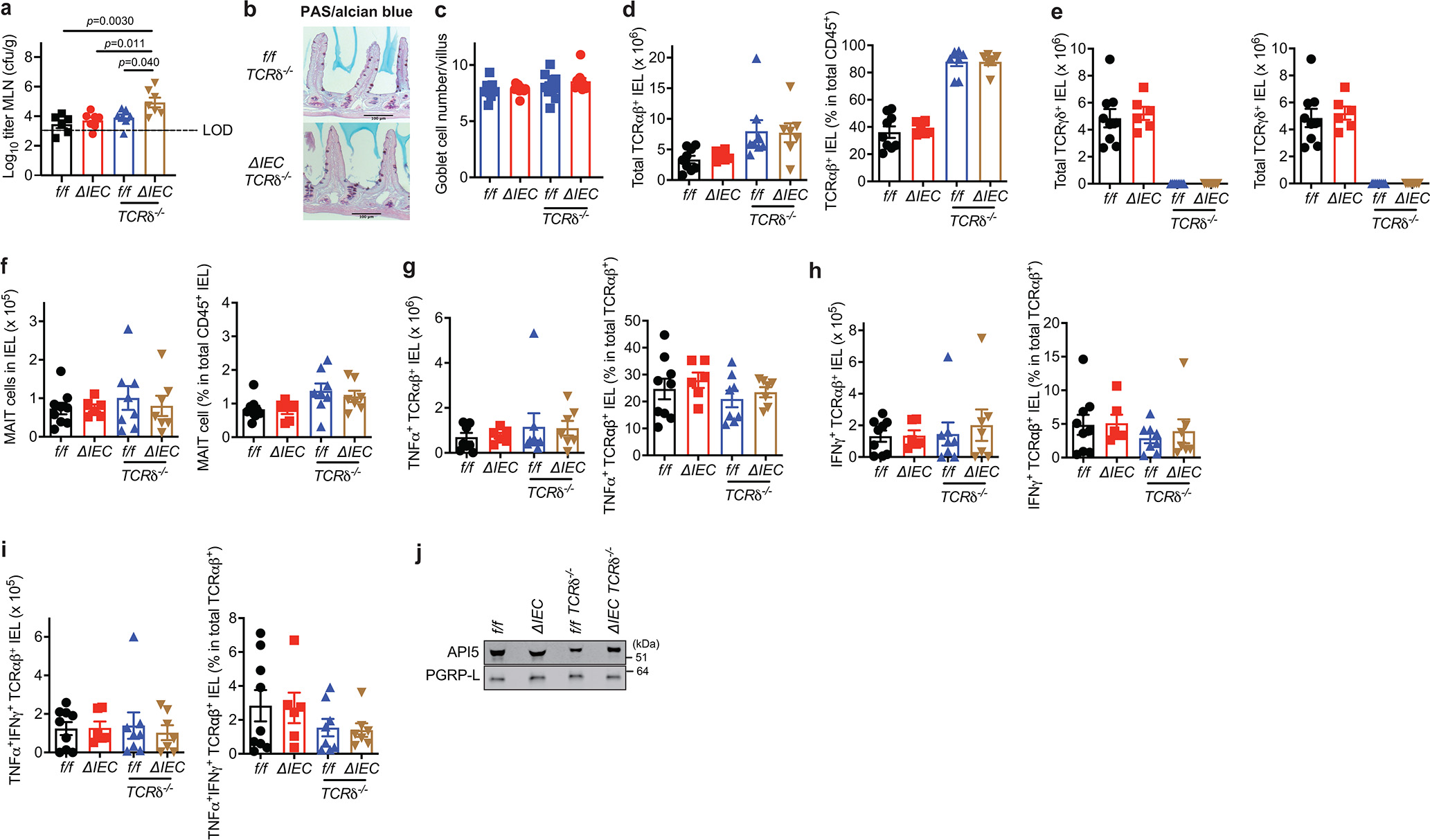

γδIELs and API5 protect ATG16L1-deficient mice

If MNV triggers intestinal disease in Atg16L1ΔIEC mice in part through interfering with this function of γδIELs, then it may be possible to phenocopy the viral trigger by crossing Atg16L1ΔIEC mice with TCRδ−/− mice that lack γδ T cells. Indeed, we found that Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice displayed spontaneous PC loss without having to infect them with MNV (Fig. 3a, b). Similar to MNV-infected Atg16L1ΔIEC mice12, Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice harbored an increase in TUNEL+ but not cleaved caspase-3+ IECs in SI crypts and increased bacterial burden in the mesenteric lymph nodes, whereas goblet cell numbers were similar among groups (Fig. 3a, b, Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). The remaining PCs in Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice displayed an abnormal lysozyme staining pattern (Fig. 3c, d). In a manner dependent on MNV infection, Atg16L1ΔIEC mice display exacerbated mortality following intestinal injury with 5% DSS in the drinking water12. Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice were susceptible to DSS-induced lethality and morbidity compared with single mutant Atg16L1f/fTCRδ−/− or Atg16L1ΔIEC mice, even in the absence of MNV-infection (Fig. 3e, f). Antimicrobials from PCs can affect either the SI or colon33–35. The increased susceptibility to DSS displayed by Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice was accompanied by SI defects, specifically, higher levels of local cytokine production, shorter villi, and fewer PCs (Extended Data Fig. 7a–e).

Fig. 3 |. γδIELs and API5 prevent PC loss and protect against intestinal injury in Atg16L1 mutant mice.

a-d, Representative images (a, c) and quantification (b, d) of H&E, TUNEL, and cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) staining (a) and IF images of lysozyme (red) and DAPI (blue) (c) of Atg16L1f/f (f/f), Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC), Atg16L1f/fTCRδ−/− (f/f TCRδ−/−), and Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−) mice. Arrowheads indicate PCs or IECs positive for the individual markers. Lysozyme staining in (d) was quantified based on whether PCs displayed a typical staining pattern with distinguishable granules (normal) or depleted and/or diffuse staining (abnormal). n=11 (f/f), 11 (ΔIEC), 10 (f/f TCRδ−/−), and 10 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−) in (a) and (b), and n=11 (f/f), 9 (ΔIEC), 7 (f/f TCRδ−/−), and 7 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−) in (c) and (d). Scale bar 20 μm. e, f, Survival (e) and disease score on day 6 (f) of f/f, ΔIEC, f/f TCRδ−/−, and ΔIEC TCRδ−/− mice treated with 5% DSS for 6 days. n=10 (f/f), 10 (ΔIEC), 16 (f/f TCRδ−/−), and 13 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−). g, WB analysis of SN harvested from gut explants derived from TCRδ+/+ or TCRδ−/− mice. h, i, Representative images (h) and quantification (i) of H&E, TUNEL, and CC3 staining of f/f TCRδ−/− and ΔIEC TCRδ−/− mice injected intravenously with 40 μg/mouse of wild-type or Y8K:Y11K rAPI5 protein. Arrowheads indicate PCs or IECs positive for the individual markers. n=7 (f/f TCRδ−/− rAPI5Y8K:Y11K), 8 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/− rAPI5Y8K:Y11K), 8 (f/f TCRδ−/− rAPI5WT), 10 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/− rAPI5WT). Scale bar 20 μm. j, WB analysis of γδ SN and cell lysates from Api5+/+ or Api5+/− mice and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. k, l, m, n, Representative images (k, m) and quantification (l, n) of H&E images (l) and IF images of lysozyme (red) and DAPI (blue) (n) of Atg16L1f/f Api5+/− (f/f Api5+/−) and Atg16L1ΔIEC Api5+/− (ΔIEC Api5+/−) mice. Arrowheads indicate PCs. n=6 (f/f Api5+/−) and 5 (ΔIEC Api5+/−). Scale bar 20 μm. An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (b, d, f, i). Mantel-Cox log-rank test in (e). Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (l, n). Data points in (b), (d), (i), (l), and (n) represent individual mice, data points in (f) are mean of disease scores of viable mice. Bars represent means ± SEM, and survival data in (e) are combined results of 2 experiments performed independently. At least two independent experiments were performed in (g, j).

Lower levels of API5 were detected in the supernatant of gut explants harvested from TCRδ−/− mice than WT mice (Fig. 3g). Also, intravenous injection of rAPI5WT, but not rAPI5Y8K:Y11K, restored PCs in Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice (Fig. 3b, h, i). Moreover, Atg16L1ΔIEC TCRδ−/− mice injected with rAPI5WT, but not rAPI5Y8K:Y11K, displayed 100% survival and an improved disease score (Extended Data Fig. 7f, g). Depletion of γδ T cells increases mucosa-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells in the skin36, raising the possibility that PC defects are explained by changes in other lymphoid populations in Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice. TCRδ−/− and Atg16L1ΔIECTCRδ−/− mice did not show major changes in the number of MAIT cells or TNFα+ and IFNγ+ αβIELs, and API5-secretion from αβIELs was unaltered (Extended Data Fig. 6d–j). Using CRISPR-Cas9 targeting, we were able to obtain only a few viable Api5−/− mice or Atg16L1ΔIECApi5−/− after several rounds of breeding (Extended Data Fig. 8a–d). Although their numbers were lower than expected based on Mendelian inheritance, we were able to analyze Atg16L1ΔIECApi5+/− mice. γδIELs harvested from Api5+/− mice secreted less API5 than Api5+/+ mice and failed to protect Atg16L1ΔIEC organoids and their PCs, and Api5-heterozygosity did not affect the number of TCRαβ+, TCRγδ+, CD4+ or CD8+ IELs (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 8e–i). Atg16L1ΔIECApi5+/− mice had decreased PC numbers, and a higher proportion were morphologically abnormal (Fig. 3k–n). Thus, API5 and γδIELs are essential for protecting PCs in Atg16L1ΔIEC mice.

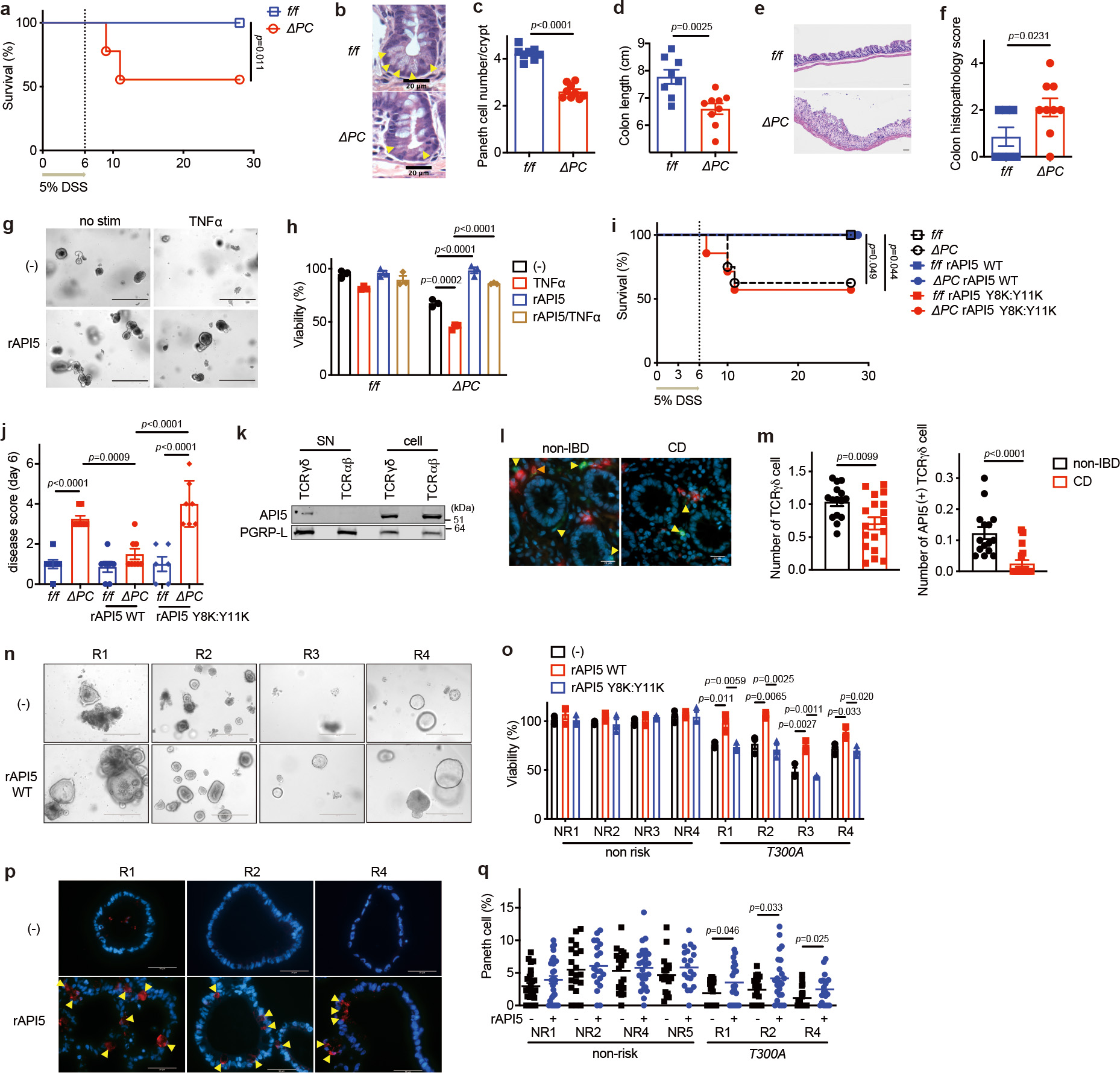

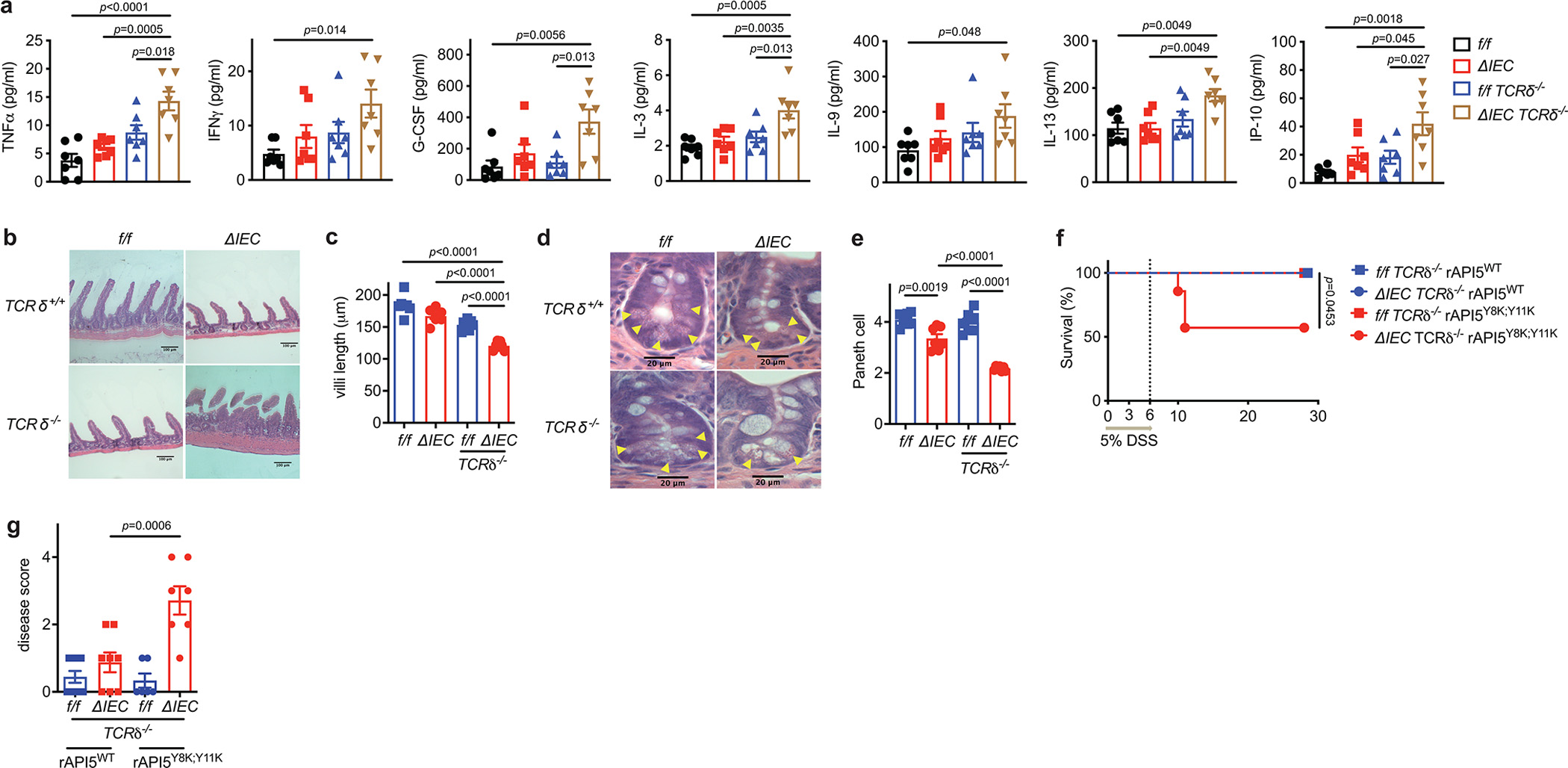

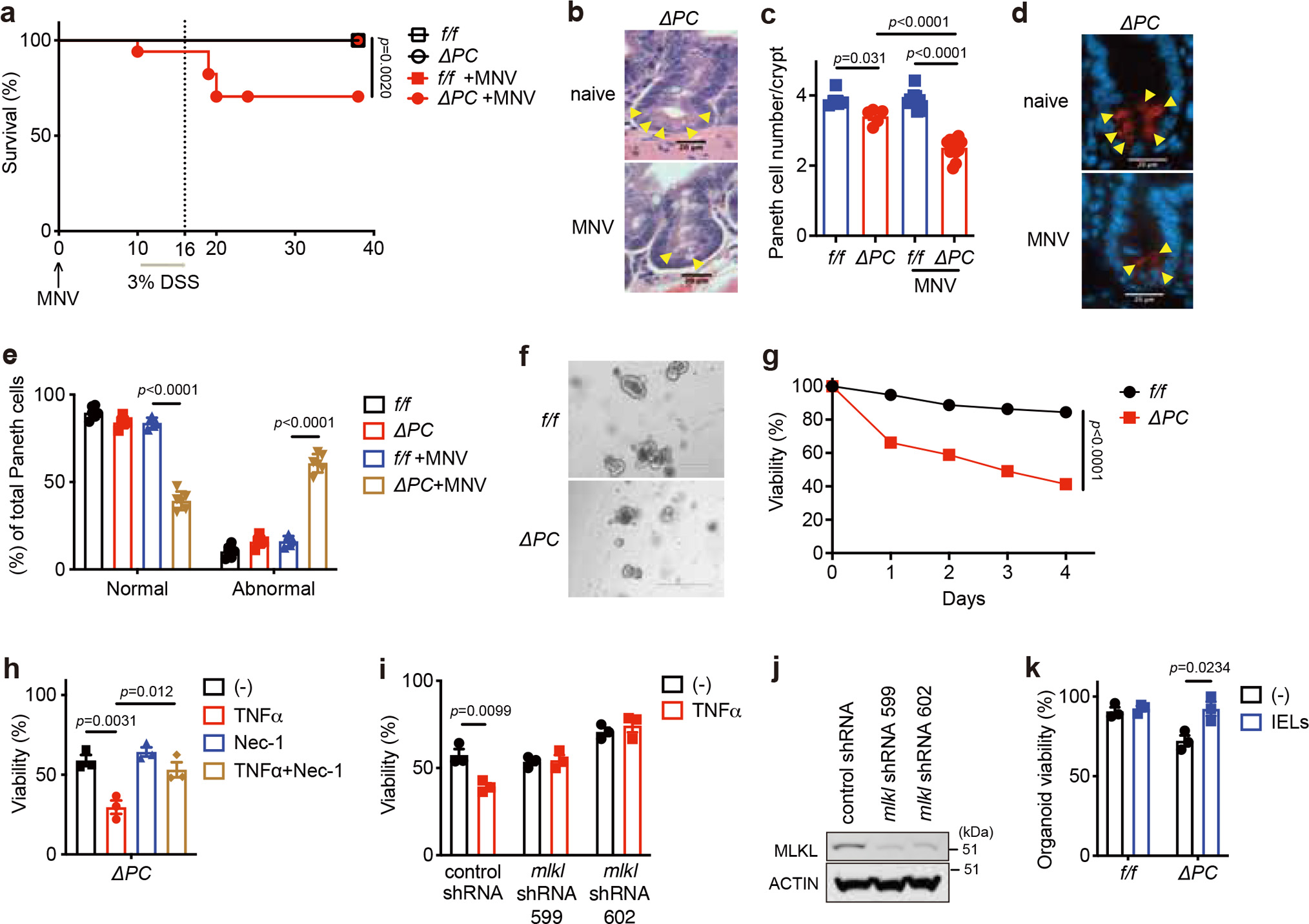

API5 supports ATG16L1-deficient PCs

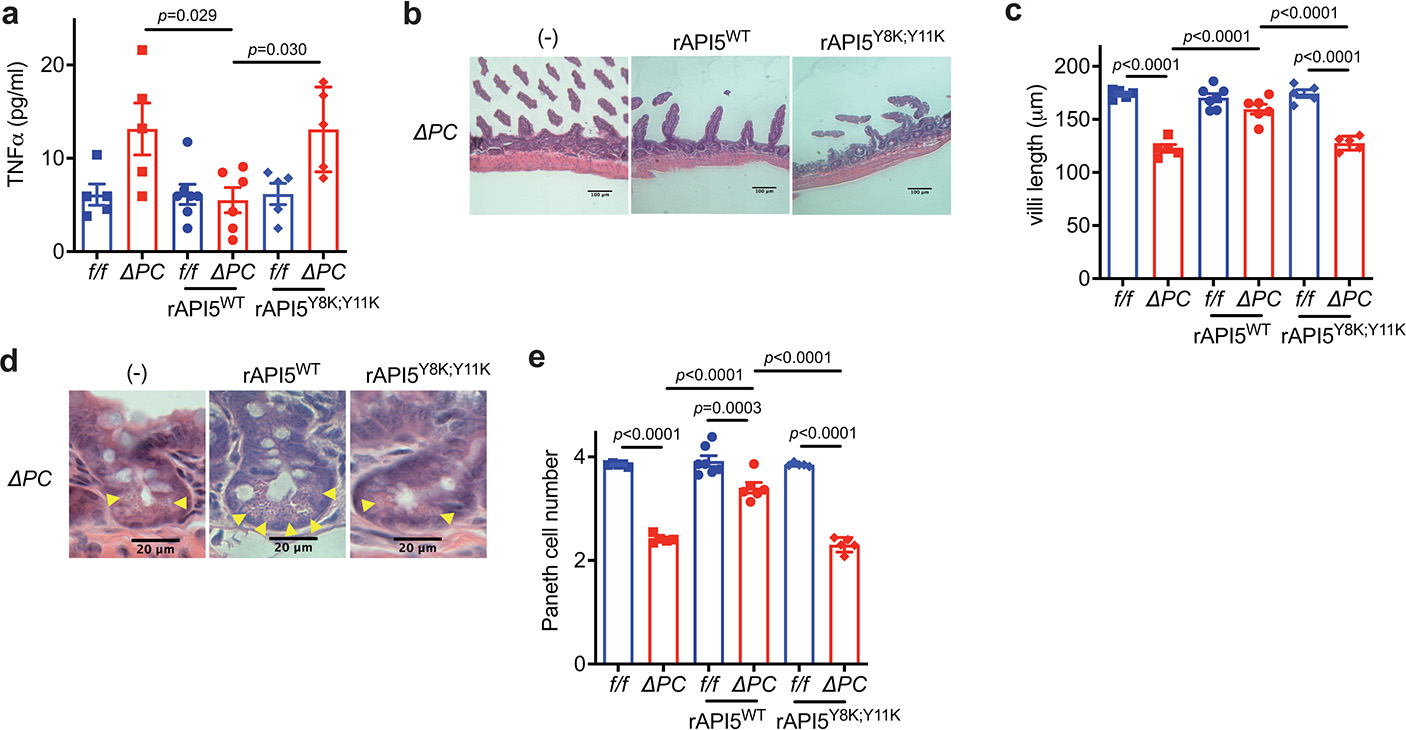

We examined whether ATG16L1 functions in a PC-intrinsic manner in the setting of API5-mediated protection. A concentration of 3% DSS caused lethality and PC defects in mice with a PC-specific deletion of Atg16L1 (Atg16L1f/fdefa6-Cre; Atg16L1ΔPC) following MNV infection (Extended Data Fig. 9a–e). When we administered 5% DSS to Atg16L1ΔPC mice, MNV was dispensable for the heightened lethality and loss of PCs (Fig. 4a–c), highlighting the importance of genetic susceptibility to PC abnormalities in intestinal disease. 5% DSS-treated Atg16L1ΔPC mice displayed shortening of the colon and increased colonic inflammation (Fig. 4d–f). SI organoids derived from Atg16L1ΔPC mice showed impaired growth and susceptibility to TNFα-induced death, which was reversed with RIPK1-inhibitor treatment and MLKL knockdown (Fig. 4g, h, Extended Data Fig. 9f–j). Co-culture with IELs or rAPI5 treatment improved viability and decreased susceptibility to TNFα-induced cell death in Atg16L1ΔPC organoids (Fig. 4g, h and Extended Data Fig. 9k). rAPI5WT-injected Atg16L1ΔPC mice displayed 100% survival, an improved disease score, reduced local TNFα, and less severe villus blunting compared with untreated or rAPI5Y8K:Y11K-injected mice in the DSS model (Fig. 4i, j and Extended Data Fig. 10a–e).

Fig. 4 |. API5 protects mouse and human PCs against the detrimental effects of ATG16L1 mutation.

a, Survival of Atg16L1f/f (f/f) and Atg16L1ΔPC (ΔPC) mice treated with 5% DSS for 6 days. n=12 (f/f) and 9 (ΔPC). b-f, Representative images of H&E (b, e) and quantification of PCs (c), colon length (d), and colon histopathology score (f) of mice treated as in (a) and euthanized on day 6 post 5% DSS. Arrowheads indicate PCs. n=8 (f/f) and 9 (ΔPC). Scale bar 20 μm (b) and 100 μm (e). g, h, Representative images (g) and viability (h) of SI organoids from f/f and ΔPC mice ± 20 ng/ml TNFα for 48 hours after pretreatment with 50 nM wild-type rAPI5 for 3 days. Scale bar 400 μm. i, j, Survival (i) and disease score on day 6 (j) of f/f and ΔPC mice injected intravenously with 40 μg/mouse of wild-type or Y8K:Y11K rAPI5 protein on day 0, 3, and 6 while treated with 5% DSS for 6 days. 100% survival for f/f, f/f rAPI5WT, ΔPC rAPI5WT, and f/f rAPI5Y8K:Y11K. n=7 (f/f), 8 (ΔPC), n=7 (f/f rAPI5WT), 9 (ΔPC rAPI5WT), n=6 (f/f rAPI5Y8K:Y11K), 7 (ΔPC rAPI5Y8K:Y11K). k, WB analysis of γδ SN and cell lysate sorted from mixed human PBMCs and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. l, m, Representative IF images (l) of TCRγ/δ (green), API5 (red), and DAPI (blue) in terminal ileum derived from Crohn’s disease (CD) patients or non-IBD individuals, and quantification of γδIELs (m, left) and API5+ γδIELs (m, right) near crypts (< 20 μm). Yellow arrowheads indicate TCRγδ+ IEL, and orange ones indicate API5+ TCRγδ IEL. n=15 (non-IBD) and n=18 (CD). Scale bar 20 μm. n, o, Representative images (n) and viability (o) of SI organoids derived from indicated individuals harboring 0–1 (non-risk, NR1–4) or 2 (T300A, R1-4) copies of ATG16L1T300A risk allele. Viability was measured 48 hours after the culture medium was changed to the differentiation medium ± 100 nM wild-type or Y8K:Y11K rAPI5. Scale bar 400 μm. p, q, Representative IF images of lysozyme (red) and DAPI (blue) (p) and quantification of PCs (q) in organoids derived from the indicated individuals as in (o). Arrowheads indicate PCs. Organoids were cultured with the differentiation medium for at least 2 months ± 100 nM wild-type rAPI5. Scale bar 50 μm. In mouse organoid experiments in (h), intestinal crypts were harvested from 3 mice per genotype. Organoid viability assays were performed in triplicate. Mantel-Cox log-rank test in (a, i). Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (c, d, f, m, o, q). An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (h, j). Data points in (c), (d), and (f) represent individual mice, data points in (h) represent organoid viability in each well, data points in (j) are mean of disease scores of viable mice, data points in (m) represent individual patients, and data points in (o) and (q) represent individual organoids. Bars represent means ± SEM, and survival data in (a) and (e) are combined results of at least 2 experiments performed independently. At least two independent experiments were performed in (k).

API5 restores PCs in organoids derived from individuals homozygous for the ATG16L1T300A risk allele

We detected API5 in supernatant harvested from γδ but not αβT cells sorted from peripheral blood of healthy human donors (Fig. 4k). Similar to a recent study reporting a reduction of γδIELs in the terminal ileum of CD patients by flow cytometry24, we found less γδIELs, especially API5+ γδIELs, near crypts in the terminal ileum of CD patients (Fig. 4l, m and Table S2). Peripheral γδ T cells are predominantly Vδ2+ and distinct from Vδ1+ tissue-resident IELs37–39. However, IBD patients display aberrant expansion of Vδ1+ T cells in the periphery40,41, which may be a reflection of reshaping the tissue-resident IEL compartment during intestinal inflammation, as documented during celiac disease23. Our results are consistent with such observations and suggest a local inflammatory environment excludes API5+ γδIELs or interferes with API5 secretion. The T300A substitution in the disease variant of ATG16L1 increases proteolytic cleavage and compromises protein-protein interactions42–44. Consistent with reduced functionality in humans45, we previously showed that knock-in mice with the equivalent amino acid substitution display similar MNV-induced defects as Atg16L1ΔIEC mice12. These observations raise the possibility that API5 is a secreted molecule with a protective function in humans with the ATG16L1T300A allele.

A recent study developed a modified human organoid culture medium containing insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) that improves differentiation of mature IECs, including PCs, to better capture the cellular landscape of the human intestine41,46. SI organoids derived from individuals harboring 2 copies of the CD ATG16L1T300A, but not 0 or 1 copy, displayed impaired viability and were deficient in PCs when cultured in this differentiation medium (Fig. 4n–q and Table S3). rAPI5WT but not rAPI5Y8K:Y11K consistently protected ATG16L1T300A homozygous organoids and reversed the PC defect, and had minimal effects on control organoids (Fig. 4n–q). These data indicate that API5 supports human PC viability and differentiation, which in turn protects the viability of organoids.

Discussion

Our previous observations implicating lymphoid cytokine responses downstream of viral infection in Atg16L1 mutant mice led us to scrutinize the IEL compartment in this study. Following our unexpected observation that γδIELs improve the viability of Atg16L1-deficient organoids and PC numbers, we identified API5 as a previously unknown lymphocyte-derived protective factor. Inhibiting γδIELs or API5 in Atg16L1 mutant mice caused a reduction in PCs and exacerbated intestinal injury, providing a remarkable example of how a lymphocyte subset can mask genetic susceptibility to inflammatory disease. It is worth noting that the ATG16L1T300A allele occurs at high frequency in the healthy human population, suggesting environmental stressors can sometimes unmask the deleterious effect of the variant. Although many microbes have been implicated, cause-effect relationships are exceedingly difficult to infer for CD42,47. The observation that both MNV and Salmonella interfere with API5 secretion by γδIELs suggests that the immune state of the host may be more important than a specific infectious agent. Moreover, smoking is associated with PC defects in mice and CD patients with the ATG16L1T300A allele43,48. Rather than a specific microbe or toxic trigger, it is possible that multiple environmental stressors that disrupt IEL function can lead to PC dysfunction and disease. If PC abnormalities contribute to sustaining inflammation, combining anti-inflammatory agents with therapeutic strategies that restore the protective function of IELs such as API5 administration may be particularly effective in reversing the course of disease.

Methods

Mice

Age- and gender-matched 6–15 weeks old mice on the C57BL/6J (B6) background were used. The following mice harboring gene deletions were compared to littermate control mice with the intact genetic locus. Atg16L1f/f;villinCre (Atg16L1ΔIEC) and littermate control Atg16L1f/f mice were generated as previously described12. Atg16L1f/f;defa6-Cre (Atg16L1ΔPC) were generated by crossing Atg16L1f/f mouse with defa6-Cre mouse as previously described7. Atg16L1ΔIEC TCRδ−/− mice were generated for experiments by crossing Atg16L1ΔIEC mice with TCRδ−/− mice. B6 (WT), TCRδ−/− and TCRδGFP reporter mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and bred onsite to generate animals for experimentation. The generation of Api5−/− mice are described below. E8Itomato reporter mice were generated by crossing E8I-Cre mice to RosalsldtTomato mice25. All animal studies were performed according to approved protocols by the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and The Rockefeller University Animal Care and Use committee (IACUCs).

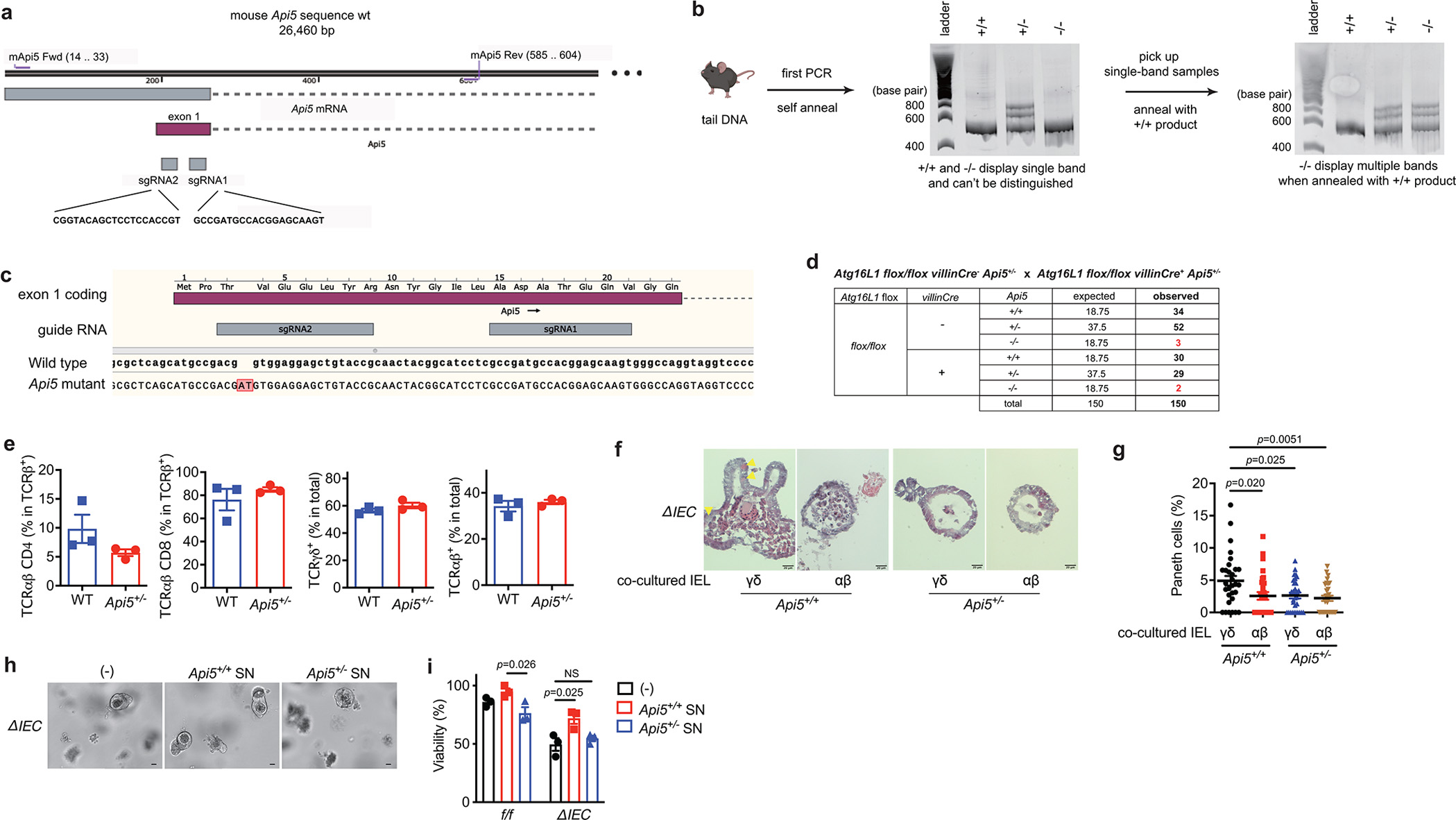

Generation of Api5 knockout mice

The CRISPR-Cas9 gene targeting mixture containing sgRNAs #1 GCCGATGCCACGGAGCAAGT and #2 CGGTACAGCTCCTCCACCGT targeting exon 1 of Api5 (synthesized at Integrated DNA Technologies Inc.) and Cas9 mRNA were injected into the cytoplasm of zygotes generated from Atg16L1f/f females impregnated by Atg16L1f/f;villinCre males, and then the microinjected embryos were incubated in KSOM medium at 37 °C for one day and subsequently transferred into pseudopregnant CD-1 female mice at the two-cell stage by the Rodent Genetic Engineering Laboratory of NYU Grossman School of Medicine. The resulting 23 F0 chimeras were screened through a PAGE-based genotyping approach49: amplicons generated using primers (Fwd: cgcgccagtctctgcgtaga and Rev: gccgcgtgtgagagttccta) flanking the targeting sites and tail DNA from chimeras and wild-type mice as templates were annealed, and heteroduplexes signifying mismatches between the wildtype sequence and the disrupted locus were detected by altered migration on a 15% PAGE-TBE gel (Extended Data Fig. 8a–b). 12 mice were determined to harbor mutations in Api5 through this initial screen (1 homozygous and 11 heterozygous). 3 mice (1 male homozygous and 2 male heterozygous) were backcrossed with Atg16L1f/f;villinCre mice. The one homozygous Api5 mutant failed to breed. After repeated attempts, we were able to obtain 5 pups (F1) from one of the other breeder pairs, 3 of which contained the Api5 mutation. The locus surrounding the targeted region of Api5 was cloned into a plasmid using the TOPO™ TA Cloning™ Kit, and sequencing (Psomagen) identified a dinucleotide AT insertion after the third codon of API5 that causes a frameshift leading to an early stop codon at amino acid position 30 (Extended Data Fig. 8c).

To circumvent the low efficiency breeding and prevent loss of the line, we performed in vitro fertilization (IVF) using 2 Api5+/− males (one was Atg16L1f/f Api5+/− and the other was Atg16L1f/f;villinCre Api5+/−). 13 females (7 Atg16L1f/f;villinCre and 6 Atg16L1f/f) were superovulated by an injection of 5 IU of pregnant mare’s serum gonadotropin and human chorionic gonadotropin according to standard procedures. Superovulated females were used for egg donor for IVF and fertilized eggs at the pronucleus stage were collected in M2 medium. We obtained 7 pups (F2), 3 Api5+/− and 4 Api5+/+ (on the Atg16L1f/f;villinCre background). We crossed the 3 Api5+/− mice with fresh Atg16L1f/f;villinCre mice, and used these pups (F3) for subsequent breeding and experiments. All mice used in experiments were backcrossed at least 3 generations.

Infection with MNV and Salmonella, administration of DSS and Indomethacin

MNV-CR6 concentrated stock was prepared as described12,15–17. Briefly, supernatant from 293FT cells transfected with a plasmid containing the viral genome was applied to RAW264.7 cells to amplify virus production, and virions were concentrated by ultracentrifugation and resupension in endotoxin-free PBS. Mice were infected orally by pipette with 3 × 106 PFUs resuspended in 25 μl PBS. On day 10 post infection, mice were euthanized for flow cytometric analyses or cell sorting. In the virally triggered disease model (see Extended Data Figure 14), Atg16L1ΔPC mice were infected with MNV and administered 3% DSS (TdB Consultancy) in their drinking water on day 10, and on day 16 the DSS-containing water was replaced by regular drinking water for the remainder of the experiment. In other DSS experiments, 5% DSS was administered for the first 6 days and replaced with regular water for the remainder of the experiment. Disease score was quantified on the basis of five parameters as described previously12, including diarrhea (0–2), hunched posture (0–2), fur ruffling (0 or 1), mobility (0–2), and blood stool (0 or 1), in which eight was the maximum score for the pathology.

WT mice were orally inoculated with 108 CFU of Salmonella enterica Typhimurium (SL1344) as previously described19. Briefly, Salmonella was grown in 3 mL of LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml streptomycin overnight at 37°C with agitation, and then the bacteria were sub-cultured (1:30) into 3 mL of LB for an additional 3.5 hours at 37°C with agitation. The bacteria were next diluted to final concentration in 1 mL of PBS. Bacteria were inoculated by gavage into recipient mice in a total volume of 100 μl, and their IELs were harvested 20 hours post infection. Salmonella (SL1344) was kindly provided by Dr. Dan R. Littman (NYU Grossman School of Medicine).

For indomethacin model, 10 mg/kg indomethacin (Millipore Sigma) in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was orally administered to WT mice, and their IELs were harvested 20 hours post administration.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Quantification of all microscopy data was performed blind. Intestinal sections were prepared and stained with H&E and PAS/Alcian blue as previously described12. Colon histopathology was scored by Y.D. by grading semiquantitatively as 0 (no change) to 4 (most severe) for the following inflammatory lesions: severity of chronic inflammation, crypt abscess, and granulomatous inflammation; and for the following epithelial lesions; hyperplasia, mucin depletion, ulceration, and crypt loss12,16. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for cleaved caspase-3 and TUNEL was performed as previously described12,14. Appropriate positive and negative controls were run in parallel to study sections. At least 50 crypt-villus axes per mouse were observed to measure the length of villus or to count Paneth cells, goblet cells, cleaved caspase-3+ and TUNEL+ cells.

For lysozyme staining of mouse small intestine, the tissues were fixed in 10% Buffered Formalin Acetate (fisher chemial) for 48–72 hours and processed through graded ethanol, xylene and into paraffin in a Leica Peloris automated processor. Five-micron paraffin-embedded sections were immunostained on a Leica BondRX® autostainer, according to the manufacturers’ instructions. In brief, sections underwent epitope retrieval for 20 minutes at 100° with Leica Biosystems epitope retrieval 1 solution (ER1, citrate based, pH 6.0), then incubated for 1 hour with an anti-lysozyme primary antibody (Abcam) diluted 1:5000 in Leica diluent (Leica) followed by an Alexa 594 fluor-coupled to Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG secondary (ThermoFisher) diluted 1:100 for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were counter-stained with DAPI and mounted with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen). For quantification of lysozyme staining of mouse intestine, at least 100 crypts/mouse were observed and individual Paneth cells were classified into D0/D1 (normal) or D2/D3 (abnormal) as described previously normal (D0), disordered (D1), depleted (D2), and diffuse (D3)1,15. D0/D1 were grouped as normal, and D2/D3 were grouped as abnormal.

For API5 and TCRγ/δ co-staining of human terminal ileum, frozen sections were prepared by fixing the pinch biopsies with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and cryoprotecting with 30% sucrose (Millipore Sigma). Fixed tissues were mixed with NEG-50 (ThermoFisher) cooled by dry ice, sectioned at 5 μm and collected Plus slides (ThermoFisher), and stored at −80°C prior to use. The frozen slides were air dried overnight followed by fixation in Acetone for 15 minutes and air dried again for 15 minutes. Sequential fluorescent immunohistochemistry (FIHC) was performed using unconjugated rabbit polyclonal anti-FIF antibody (abcam, ab65836) and unconjugated mouse monoclonal TCR gamma/delta antibody (ThermoFisher, TCR1061) on a Ventana Medical Systems Discovery Ultra instrument using Ventana’s reagents and detection kits unless otherwise noted. Anti-FIF was diluted 1:1000 (0.5ug/ml) in Ventana Diluent 219 (Cat# 760–219) and incubated for 3 hours at room temperature. Anti-FiF was detected with HRP conjugated goat anti-rabbit incubated for 8 minutes followed by Tyramide conjugated Rhodamine for 16 minutes. Anti-TCR was diluted 1:10 (1.5 ug/ml) in Ventana Diluent 250 (Cat# ABD250) and incubated for 12 hours at room temperature. Anti-TCR was detected with HRP conjugated goat anti-rabbit (prediluted product) incubated for 8 minutes followed by Tyramide conjugated FITC for 8 minutes. Slides were counterstained with 100.0 ng/ml DAPI (Molecular Probes) for 5 minutes, rinsed with distilled water, and cover-slipped with Prolong Gold Anti-fade media (Molecular Probes). Negative controls consisted of Ventana Antibody Diluent substituted for primary antibody.

For intestinal organoids, frozen sections were prepared as previously described12. The sections were air-dried at room temperature and then stained with H&E or anti-lysozyme (abcam) followed by the secondary Alexa Fluor 594 antibody (Invitrogen). Paneth cells were quantified in at least 20 organoids per sample.

For phospho (p)-MLKL and lysozyme co-staining of intestinal organoids, 5 μm sections were deparaffinized and stained with Akoya Biosciences® Opal™ multiplex automation kit reagents on a Leica BondRX® autostainer, according to the manufacturers’ instructions. In brief, slides were incubated with the first pair of primary and secondary antibodies followed by HRP-mediated tyramide signal amplification with a specific Opal® fluorophore, as indicated in the antibody table (supplementary method Table). The primary and secondary antibodies were subsequently removed with a heat retrieval step, leaving the Opal fluorophore covalently linked to the tissue. This sequence was repeated with the second primary/secondary antibody pair and a different Opal fluorophore. Sections were counterstained with spectral DAPI (Akoya Biosciences) and mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Histology and IHC samples were analyzed using Zeiss AxioObserver.Z1 with Zen Blue software (Zeiss). Microscopic analyses of live organoids were performed using a Zeiss AxioObserver.Z1 with Zeiss Zen Blue software or EVOS FL Auto (Life Technologies). Images were processed and quantified using ImageJ.

Isolation of IELs

Small intestinal IELs were isolated as previously described50. Briefly, small intestine (Peyer’s patches removed) was cut longitudinally and rinsed in HBSS. The tissue was washed in HBSS containing HEPES, sodium pyruvate, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT for 15 min to obtain the IEL fraction. The IEL was filtered and fractionated on a Percoll gradient (40% and 80%). The cells at the interphase of the gradient were collected and washed with complete RPMI.

Gut explant model

1 cm piece of terminal ileum was harvested from mice, cut longitudinally and rinsed in PBS. The tissue was incubated in 1 ml of AIM V Serum Free Medium (ThermoFisher) in the presence of 100 IU Penicillin and 100 μg/ml Streptomycin (Corning) and 125 μg/ml Gentamicin (ThermoFisher) in 24-well plate. Each culture medium was harvested 4 hours post incubation, centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C prior to use.

Flow cytometry, cell sorting, and cytokine analyses

Anti-mouse antibodies were obtained from BioLegend (CD45, CD4, CD8α, TCRβ, TCRγ/δ, CD103, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IgG1 Control) and BD Biosciences (IgG1κ Control). For intracellular staining, Alexa fluor 700 Rat IgG1κ and FITC Mouse IgG1κ isotype antibodies were used as isotype control. The MR1 tetramer technology was developed jointly by Dr. James McCluskey, Dr. Jamie Rossjohn, and Dr. David Fairlie, and the material was produced by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility as permitted to be distributed by the University of Melbourne. Anti-human antibodies were obtained from BioLegend (CD45, TCRα/β) and eBioscience (TCRγ/δ). Cells were stained for 20 min at 4°C in PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (PBS/BSA) after Fc block (Bio X CELL), washed, fixed with Fixation Buffer (Biolegend) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and resuspended in PBS/BSA. Blue fluorescent reactive dye (Invitrogen) or DAPI (Invitrogen) were used to exclude dead cells. Flow cytometry was performed on an LSR II (BD Biosciences), cell sorting was performed with Aria II (BD Biosciences), data collected with FACSDiva and analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star Software).

Cytokine quantification was determined using the MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Kit (MCYTMAG-70K-PX32, Millipore). The assay was conducted as per the manufacturer’s instructions, and plates were run on a MAGPIX Luminex XMAP instrument with xPONENT software (ver 4.3).

Bacterial burden in mesenteric lymph nodes

Mesenteric lymph nodes were weighed and homogenized in sterile PBS. Serial dilutions of the homogenates were plated on blood agar plates and colonies were quantified following up to 24 hours incubation at 37°C. Bacterial titers are shown as cfu/g.

Multiphoton microscopy and computational analysis

Intravital multiphoton microscopy and computational analysis were performed as previously described19. Briefly, E8Itomato or TCRγδGFP reporter mice were anesthetized and injected with Hoechst dye (blue) for visualization of epithelial cell nuclei before surgery for intravital imaging. 10 min following induction of anesthesia, mice were placed on a custom platform. Upon loss of recoil to paw compression, a small incision was made in the abdomen. The ileum entrance to the caecum was located and a loop of ileum was exposed and placed onto a raised block of thermal paste covered with a wetted wipe. The platform was then transferred to the FV1000MPE Twin upright multiphoton system (Olympus) heated stage. Time-lapse was +/− 30sec with a total acquisition time of 30 min. A complete Z-stack (80 μm) of several ileum villi was made during each acquisition. Imaris (Bitplane AG) software was used for cell identification and tracking. The scoring of IEL behavior (flossing, speed, z-movement, location) was entirely computational and unbiased, using Python (Enthought Canopy) integrated with Microsoft Excel and with the application of standard scientific algorithm packages. “Flossing” movements are identified using extensively verified parameters, based on their unique properties (e.g., sequence of specific sharply angled movements). Raw data as imported from the microscope was used for all tracking and subsequent analyses.

Generation of human recombinant API5 protein

Human API5 coding sequence was amplified by the following primers; HBT-API5 Fwd. AGAAAACCTGTACTTCCAGGGAATGCCGACAGTAGAGGAGCTTTACC and HBT-API5 Rev. AGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCCTACTTCCCCTGAAGGCTCCTCTCA using human cDNA, and was cloned into pHBT-vector by Gibson Assembly Cloning Kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The wild type and Y8K:Y11K API5 proteins (isoform b, residues 1–504) were generated in E. coli BL21 (DE3) (MilliporeSigma Novagen) with N-terminal His6-tag and Avi-tag using derivatives of the pHFT vector51. They were first purified using nickel affinity resin, Ni Sepharose® 6 Fast Flow (Cytiva, catalog number 17–5318-06) and dialyzed in TBS (50 mM TrisCl (pH7.5), 150 mM NaCl) with 5 mM beta mercaptoethanol (MilliporeSigma, catalog number M6250) followed with TBS. The proteins were further purified using size exclusion chromatography (SEC), Superdex® 200 Increase 10/300 GL (Cytiva, catalog number 28-9909-44) equilibrated in TBS. For endotoxin removal, a SEC-purified protein was loaded onto Ni Sepharose® 6 Fast Flow column after adjusting NaCl concentration to 500 mM, and washed with 50 column volume of ice-cold 20 mM TrisCl (pH8.0) with 500 mM NaCl and 0.1 % Triton X-114, followed with 25 column volume of ice-cold 20 mM TrisCl (pH8.0) with 500 mM NaCl in a cold room (4°C). The protein was eluted with 15 mM TrisCl (pH8.0) with 375 mM NaCl and 500 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was concentrated and the buffer was exchanged to TBS by repeated dilution and concentration in Amicon15 concentrators with a 30K molecular weight cutoff (Milliporesigma, catalog number UFC903024). For in vivo administration, 40 μg/mouse endotoxin-free rAPI5 (wild-type or Y8K:Y11K) resuspended in 100 μl PBS was injected intraorbitally on day 0, 3, and 6. Mice were euthanized on day 10 (for histological analyses) or observed until day 28 (DSS disease model).

Thermal shift assay

A thermal shift assay was performed using a real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad CFX384). API5 protein samples (3 μM) and 20x SYPRO Orange dye (ThermoFisher, 1:250 dilution) were prepared in 50 mM TrisHCl buffer (pH7.5) containing 150 mM NaCl in a total volume of 25 μl. The temperature was ramped from 25°C to 99.5 °C, increasing the temperature in steps of 0.5 °C / 30 sec. Fluorescence emission signals at 575 nm with excitation at 490 nm were recorded. Data were acquired in triplicate. Samples were processed with the CFX software (Bio-Rad).

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

Sorted IELs were cultured with RPMI1640 (ThrmoFisher) suppled with 2-Mercaptoethanol (ThermoFisher) and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. Supernatant was harvested as described in Extended Data Fig. 5a. Samples were prepared for mass spectrometry analysis as previously described52. In brief, the samples were reduced with 200 mM DTT at 57°C for 1 hour, alkylated with 500 mM iodoacetamide for 45 min at room temperature in the dark, and loaded immediately onto an SDS-PAGE gel and ran as a plug to remove any detergents and LCMS incompatible reagents. The gel plugs were excised, destained, and subjected to proteolytic digestion using 150 ng of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) overnight with gentle agitation. The resulting peptides were extracted and desalted as previously described.

Aliquots of each sample were loaded onto a trap column (Acclaim® PepMap 100 pre-column, 75 μm × 2 cm, C18, 3 μm, 100 Å, Thermo Scientific) connected to an analytical column (EASY-Spray column, 50 m × 75 μm ID, PepMap RSLC C18, 2 μm, 100 Å, Thermo Scientific) using the autosampler of an Easy nLC 1000 (Thermo Scientific) with solvent A consisting of 2% acetonitrile in 0.5% acetic acid and solvent B consisting of 80% acetonitrile in 0.5% acetic acid. The peptide mixture was gradient eluted into the Orbitrap QExactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) using the following gradient: 5%–35% solvent B in 60 min, 35% –45% solvent B in 10 min, followed by 45%- 100% solvent B in 10 min. The full scan was acquired with a resolution of 70,000 (@ m/z 400), a target value of 1e6 and a maximum ion time of 120 ms. Following each full MS scan, twenty data-dependent MS/MS spectra were acquired. The MS/MS spectra were collected with a resolution of 17,500, an AGC target of 5e4, maximum ion time of 120ms, one microscan, 2m/z isolation window, fixed first mass of 150 m/z, dynamic exclusion of 30 sec, and Normalized Collision Energy (NCE) of 27.

All acquired MS2 spectra were searched against a UniProt mouse database using Sequest within Proteome Discoverer 1.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The search parameters were as follows: precursor mass tolerance ± 10 ppm, fragment mass tolerance ± 0.02 Da, digestion parameters trypsin allowing 2 missed cleavages, fixed modification of carbamidomethyl on cysteine, variable modification of oxidation on methionine, and deamidation on glutamine and asparagine. The identifications were first filtered using a 1% peptide and protein FDR cut off searched against a decoy database and only proteins identified by at least two unique peptides were further analyzed.

Human samples/study approval

Pinch biopsies were obtained with consent from adult IBD patients undergoing surveillance colonoscopy, using 2.8-mm standard biopsy forceps, after ptotocol review and approved by the New York University Grossman School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Mucosal Immune Profiling in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease; S12-01137).

Human T cells

T cells from peripheral blood of healthy human donors (Fig. 4k) were prepared as described previously14. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from anonymous, healthy donors (New York Blood Center) were isolated by Ficoll gradient separation. CD14+ monocytes were removed from the PBMC fraction by positive selection. The remaining negative fraction was used to isolate T cells.

After PBMCs from 20 healthy donors were mixed prior to sorting T cells, naïve T cells were isolated with Dynabeads™ Untouched™ Human T cells (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sorted human T cells were frozen with FBS containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Fisher Scientific) in liquid nitrogen tank until the day of FACS sorting.

Intestinal organoids

Mouse and human small intestinal organoids were cultured as described12,14. Mouse organoids were generated from mixed crypts harvested from 3 mice per genotype. Number of buds in each organoid was quantified with Image J. For organoid viability assays, 50 crypts or mature organoids were embedded in 10 μl of Matrigel and cultured in 96-well culture plate in triplicate with or without 20 ng/ml mTNFα (PeproTech), 0.2 μg/ml anti-TNFα, 20 ng/ml anti-IFNγ, 10 ng/ml mKGF (BioLegend), 20 μM Necrostatin-1 (Millipore Sigma), and 50 nM (mouse) or 100 nM (human) recombinant API5. For human organoid viability assay, the culture medium was switched from IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium (Human, STEMCELL) to IGF-1 plus FGF-2 (IF) medium46 on day 0. For lysozyme staining, each human organoid line was cultured with IF medium ±100 nM rAPI5WT for at least 2 months. Percent viable organoids was determined by daily quantification of the number of intact organoids12,14. Opaque organoids with condensed structures or those that have lost adherence were excluded. Dead organoids were marked by staining with 100 μg/ml propidium iodide (Millipore Sigma). Percent organoid viability in each well was calculated by dividing the live organoid numbers on day 2 by day 0. Each data point in the organoid viability assay represents each well. For western blot and histological analyses of organoids, 200 crypts or mature organoids were embedded in 30 μl of Matrigel and cultured in 24-well culture plate for 3 days (western blot) or 5 days (histology) unless mentioned separately.

Genotyping of each human organoid line was performed in our previous study14. The detailed information was described in Supplementary Table S3.

Lentivirus infection and gene knockdown

Lentivirus infection and gene knockdown in organoids was performed as previously described12,14. Briefly, MLKL shRNAs TRCN0000022602 (5’-CGGACAGCAAAGAGCACTAAA-3’) and TRCN0000022599 (5’-GCAGGATTTGAGTTAAGCAAA-3’) and nontargeting shRNA control (SHC016) constructs were purchased from Millipore Sigma. Each lentiviral construct along with lentiviral packaging mix (pLP1, pLP2, and VSVG; Millipore Sigma) was co-transfected into 293FT cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, then the supernatant containing lentivirus was harvested and concentrated using Lenti- X concentrator (Clontech). Small intestinal organoids from Atg16L1ΔPC mice were cultured in antibiotic-free ENR medium, which was replaced with 50% L-WRN (ATCC) conditioned medium53 supplemented with 10 mM nicotinamide (Millipore Sigma). On day 5, the organoids were mechanically dissociated into single cells by pipetting, and the fragments were incubated with TrypLE Express (Gibco) for 5 min at 37°C and centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min. The cell clusters were combined with viral suspension containing IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium (Human) supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632 dihydrochloride (Millipore Sigma) and 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Millipore Sigma). The cells were transferred into 48-well culture plate and centrifuged at 600 g at 32°C for 60 min. After 1 hour of incubation at 37°C, the cells were collected into 1.5 mL tubes and centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min. Finally, the cells were embedded in 30 μl of Matrigel and cultured in 24-well plates in antibiotic-free IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium (Human) supplemented with Y-27632 dihydrochloride. 2 days after infection the medium was changed to 50% L-WRN (ATCC) conditioned medium plus 2 μg/ml puromycin. The medium was changed to ENR in organoid viability assay.

Ex vivo organoid-IEL co-culture system

Mouse small intestinal organoids at day 3 were released from Matrigel (Corning) using Cell Recovery Solution (Corning) and incubated on ice for 45 min. Freshly isolated or FACS-sorted IELs were stimulated with 1x Cell Stimulation Cocktail (eBioscience) for 1 hour at 37 °C before co-culture. Around 250–300 intestinal organoids and separately isolated IELs (5× 105 whole (unsorted), 2.5 × 105 γδ+, or 1.5 × 105 αβ+) were mixed in 1.5 mL tubes with 1 mL of DMEM. After incubation at 37 °C for 5 min, the mixture was centrifuged for 2 min at 200g. The pellet was suspended in 50 μL of Matrigel, and each 10 μL drop was placed in 96-well plates. After Matrigel polymerization, 100 μL of culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added to each well.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Immunoblotting of intestinal organoids were performed as described previously12. Briefly, small intestinal organoids cultured ± 50 nM rAPI5 for 3 days were stimulated with 20 ng/ml mTNFα for 2 hours, released from Matrigel and incubated in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and 1x Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific)) on ice for 20 min, and centrifuged at 15,000g for 20 min. For supernatant samples, albumin was depleted with AlbuSorb Albumin Depletion Kit (Biotech Support Group) according to the manufacturer’s instruction before the samples were incubated in lysis buffer. For RIPK1-immunoprecipitation, anti-RIPK1 antibodies (D94C12 Cell Signaling Technology plus 38/RIP BD) were coupled with Dynabeads Protein G (ThermoFisher Scientific) in PBS for 1 hour. Cell lysates were incubated with the pre-coupled beads for 4 hours at 4°C. For API5-depletion, anti-API5 antibodies (anti-FIF (abcam) plus anti-API5 (E12, Santa Cruz Biotechnology)) were coupled with the Dynabeads for 1 hour. The supernatant samples were incubated with the pre-coupled beads for 24 hours at 4°C. Rabbit (DA1E) mAb IgG XP(R) isotype control antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was used as control in immunoprecipitation experiments.

Sample was resolved on Bolt 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus Gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to Immobilon-FL PVDF membranes (Millipore Sigma). For supernatant samples, 100 μg/ml human serum control (Invitrogen) was added to the Intercept (TBS) blocking buffer (LI-COR). Membrane was probed with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting studies: anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, A5441), p-MLKL (S358) (ThermoFisher Scientific, PA5-105678), MLKL (Cell Signaling Technology, 37705), anti-RIP3 (phospho S232) (Abcam, ab195117), anti-RIP3 (AbD Serotec, AHP1797), anti-RIP (Cell Signaling Technology, 3493), anti-FIF (Abcam, ab65836), PGRP-L (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-166646), Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, 9662), Caspase-8 monoclonal antibody (1G12) (Enzo, ALX-804-447), and anti-Atg16L (MBL, M150-3). After incubation with primary antibody, the membrane was washed and probed with secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. As for secondary antibodies, mouse anti-rabbit IgG (211-032-171) and goat anti-mouse IgG (115-035-174), were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, and IRDye 680RD Goat anti-Rabbit (925–68071), IRDye 800CW Goat anti-Mouse (925–32210), and IRDye 800CW Goat anti-Rat (925–32219) were purchased from LI-COR. After additional washing, protein was then detected with ChemiDoc Imaging system (Biorad) or Image Studio for Odyssey CLx (LI-COR).

Single-cell RNA sequencing and analysis

The sorted IEL suspensions were loaded on a 10x Genomics Chromium instrument to generate single-cell gel beads in emulsion (GEMs). Approximately 10,000 cells were loaded per channel. Single-cell RNA-Seq libraries were prepared using the following Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits v3.1: Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ GEM, Library & Gel Bead Kit v3.1, PN-1000121; Chromium Next GEM Chip G Single Cell Kit, PN-1000120 and Single Index Kit T Set A PN-1000213 (10x Genomics)54, and following the Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits v3.1 User Guide (Manual Part # CG000204 Rev D). Libraries were run on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 paired-end reads, read1 is 28 cycles, i7 index is 8 cycles, and read2 is 91 cycles, one lane per sample). The Cell Ranger Single Cell Software Suite, version 1.3 was used to perform sample de-multiplexing, barcode ad UMI processing, and single-cell 3′ gene counting.

The data were analyzed as previously described55. Briefly, the single cell count matrix was exported from 10x Genomics cell ranger version 3.0.0 output and subsequently analyzed in R version 3.4.1. Louvain clustering and differential expression analysis was performed with the standard functions from Seurat version 2.3.4.

Resource and Data Availability

Requests for unique biological materials generated through the course of the study should be directed to corresponding authors K.C. and S.H. Sequencing data were deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession number GSE204822. UniProt mouse database (Proteomes – Mus musculus) is publicly available on https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000000589.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

GraphPad Prism version 9 was used for statistical analysis. Differences between two groups were assessed by two-tailed unpaired t test when data was distributed normally. An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to evaluate experiments involving multiple groups. Survival was analyzed with the Mantel-Cox log rank test.

Extended Data

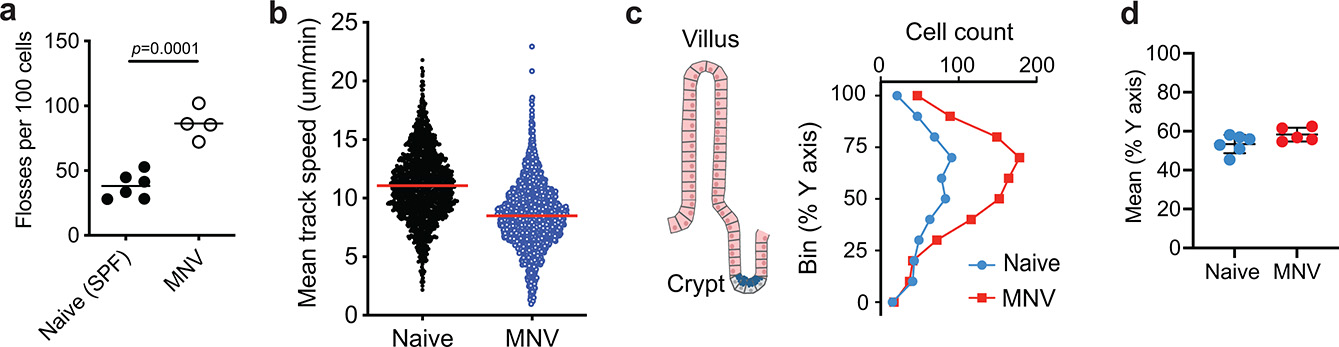

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. IELs display altered motility and positioning in MNV-infected mice (related to supplementary videos 1–4).

a-b, TCRδGFP mice were anesthetized and prepped for intravital imaging analyses 18 hours post MNV-infection. Naïve TCRδGFP mice were used as control (see supplementary movies 3 and 4). a, Unbiased computational quantification (mean and SEM) of flossing. Data analysis with two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. Data points are the average flossing per animal, from 2 independent experiments. b, Unbiased computational quantification (mean and SEM) of cell speed. Each dot represents the average speed of each cell. Data pooled of 3 animals, from 2 independent experiments. c, d, Transversal segments of the ileum from MNV-infected (red) and naïve (blue) TCRδGFP mice were fixed in 4% PFA and imaged using multiphoton microscope. c, γδ T cell distribution along the villi, from crypt (0) to tip of the villus (100). d, Mean distribution of γδ T cell along the villi. Data points in (c) and (d) represent a segment. Bars represent means ± SEM.

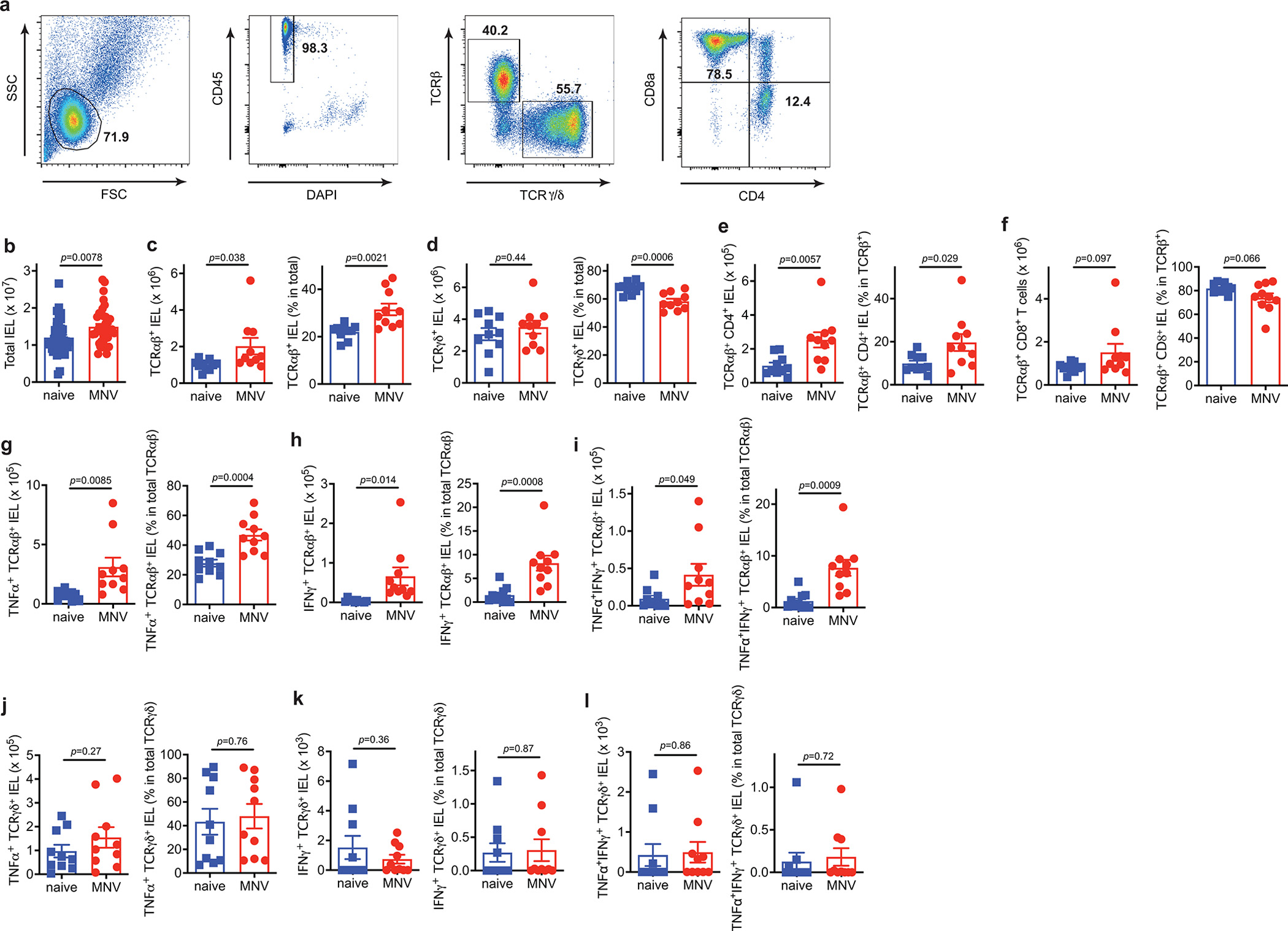

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Flow cytometric characterization of IELs in MNV-infected mice.

a-l, The IEL compartment of the small intestine from WT mice euthanized on day 10 post MNV infection were analyzed by flow cytometry and compared with naïve WT control mice. a, Representative flow cytometry plots showing gating strategy. b, Total number of live IELs harvested from whole small intestine. n= 40 (naïve) and 40 (MNV). c-l, Absolute number and proportion of the indicated subpopulations in the small intestine. n= 10 (naïve) and 10 (MNV). Data analysis with two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (b-l). Data points in (b) - (l) are individual mice. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

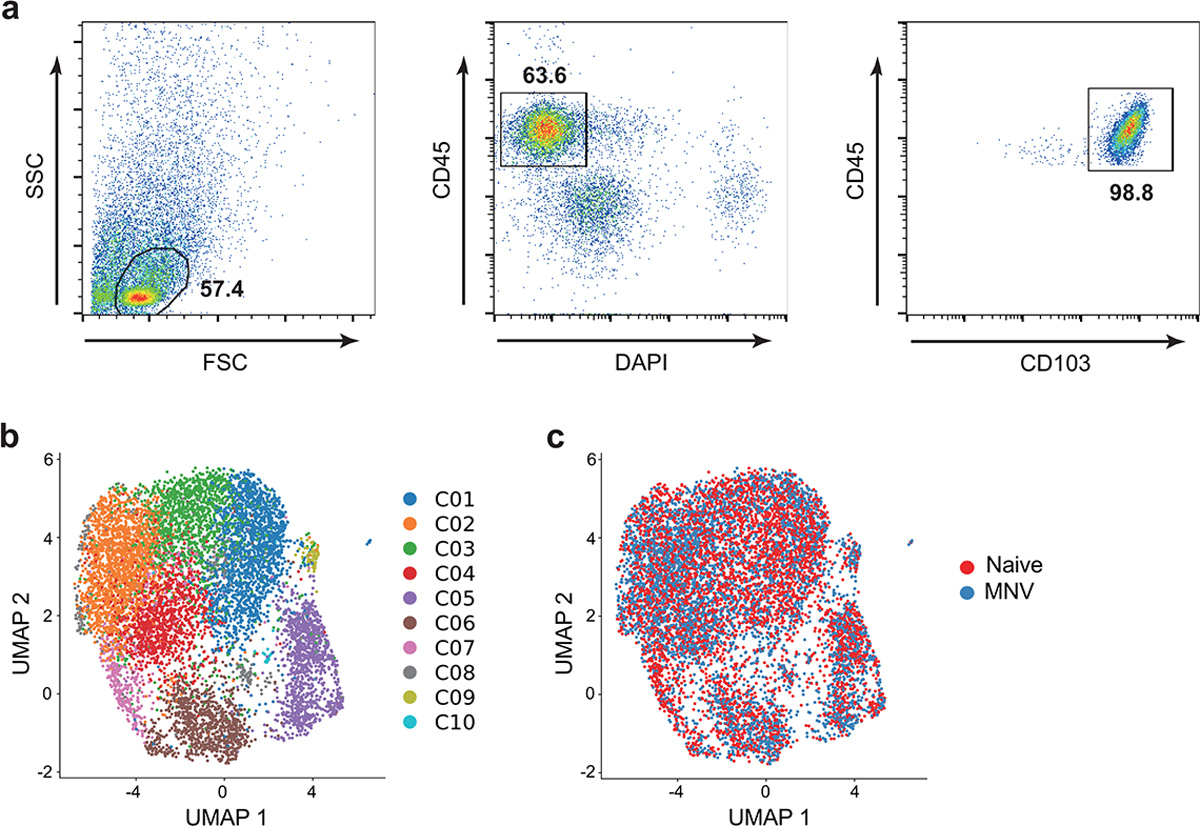

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Single cell RNA sequencing of IELs in MNV-infected mice.

a-c, CD45+CD103+ IELs from the small intestines of WT mice euthanized on day 10 post MNV-infection or naïve mice were analyzed for single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). a, Representative flow cytometry plots showing the gating strategy used to sort CD45+CD103+ IELs. b,c, UMAP analysis of CD45+CD103+ IELs profiled by scRNA-Seq and colored by unbiased louvain clustering (b) and MNV infection status (c). n= 4 (naïve) and 4 (MNV).

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Analyses of secreted products by γδ IELs.

a, Western blot analysis of supernatant (SN) harvested from TCRγδ+ IELs sorted from naïve WT mice either unstimulated (incubated in the medium for 4 hours) or stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. b-d, Representative images (b), viability (c), and area (d) of small intestinal organoids from ΔIEC mice cultured for 48 hours with either unstimulated or stimulated γδ SN in (a). Scale bar 25 μm. e, Viability of small intestinal organoids from Atg16L1f/f (f/f) and Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC) mice cultured ± 10 ng/ml recombinant KGF. Intestinal crypts were harvested from 3 mice per genotype. f, Schematic representation for the preparation of IEL SN for LC-MS. IELs were harvested from small intestine of naïve WT mice, and cultured with serum free medium stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. g, Quantification of the indicated cytokines in either γδ or αβ SN harvested from naïve WT mice (n=5). An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (c, d). Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (e, g). Data points in (c) represent organoid viability in each well, data points in (d) represent individual organoids, data points in (e) are mean of organoid viabilities performed in triplicate, and data points in (g) represent individual mice. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Generation of recombinant API5 protein and effect of environmental triggers on the secretome of IELs.

a, Architecture of API5. The N and C termini, the HEAT and ARM-like domains, residues mutated in our study (Y8, Y11) are indicated. b, Size-exclusion chromatograms of Superdex200 (GE Healthcare) of wild-type and (Y8K:Y11K) rAPI5, indicating that they are predominantly monomeric. c, Thermal denaturation of API5 monitored using SYPRO Orange binding. The graph shows the first derivative of fluorescence intensity (n=3). d, Viability of small intestinal organoids from Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC) mice cultured ± 50 nM and 200 nM wild-type or mutant (Y8K:Y11K) recombinant API5 for 48 hours. e, Western blot analysis of SN samples harvested from TCRγδ+ IELs stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours corresponding to Fig. 2i. Total SN was equally divided into three; 1 left untreated (Pre-IP), and the other 2 were immunoprecipitated with anti-API5 antibody or control IgG antibody-conjugated magnetic beads for 24 hours. f, g, Representative images (f) and viability (g) of small intestinal organoids from ΔIEC mice stimulated ± 0.5 ng/ml IFNγ for 48 hours after pretreatment with 50 nM wild-type rAPI5 for 3 days. Scale bar 25 μm. h, i, Representative H&E images (h) and quantification (i) of Paneth cell and total IEC number per organoid stimulated ± 0.5 ng/ml IFNγ ± 50 nM wild-type rAPI5 for 24 hours after pretreatment with 50 nM wild-type rAPI5 for 4 days. Arrowheads indicate Paneth cells. Scale bar 20 μm. j, Quantification of the indicated cytokines in SN of γδ IELs harvested either from naïve or MNV-infected WT mice (n=5 per condition). k, Western blot analysis of SN from γδ IELs harvested from naïve, Salmonella-infected, or indomethacin-treated WT mice following stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. l, Quantification of API5 normalized to PGRP-L by densitometric analyses of (k). Each value is divided by naïve. In organoid experiments, intestinal crypts were harvested from 3 mice per genotype. Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (d, j). An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (g, i). Two-sided paired Student’s t-test in (l). Data points in (d) and (g) represent organoid viability in each well, data points in (i) represent individual organoids, data points in (j) represent individual mice, and data points in (l) represent API5/PGRP-L value in each western blot. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Additional characterization of mice deficient in γδ T cells and ATG16L1 in the epithelium.

a, Colony forming units (CFU) of bacteria in mesenteric lymph nodes harvested from naïve Atg16L1f/f (f/f), Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC), Atg16L1f/f TCRδ−/− (f/f TCRδ−/−), and Atg16L1ΔIEC TCRδ−/− (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−) mice. n=7 (f/f), 7 (ΔIEC), 7 (f/f TCRδ−/−), and 7 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−). LOD; limit of detection. Data analysis with an ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. b, c, Representative images of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)/Alcian blue staining (b) and quantification of goblet cells (c) in the small intestinal samples harvested from naïve f/f, ΔIEC, f/f TCRδ−/−, and ΔIEC TCRδ−/− mice. n= 11 (f/f), 11 (ΔIEC), 10 (f/f TCRδ−/−), and 10 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−). Scale bar 100 μm. d-i, Absolute number and proportion of the indicated subpopulations in the small intestine. n=9 (f/f), 6 (ΔIEC), 8 (f/f TCRδ−/−), and 7 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−). j, Western blot analysis of SN harvested from TCRαβ+ IELs sorted from naïve f/f, ΔIEC, f/f TCRδ−/−, and ΔIEC TCRδ−/− mice. The IELs were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours. Each cell was pooled from 3 mice per genotype. Data points in (a), (c) - (i) are individual mice. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. γδ IELs and rAPI5 protect Atg16L1ΔIEC mice against DSS-induced intestinal inflammation.

a-e, Atg16L1f/f (f/f), Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC), Atg16L1f/f TCRδ−/− (f/f TCRδ−/−), and Atg16L1ΔIEC TCRδ−/− (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−) mice were treated with 5% DSS, and euthanized on day 5. n=7 (f/f), 7 (ΔIEC), 7 (f/f TCRδ−/−), and 7 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/−). a, Quantification of the indicated cytokines in SN harvested from gut explants. b, c, d, e, Representative images of H&E staining (b and d) and quantification of villi length (c) and Paneth cells (e). Scale bar 100 μm (b) and 20 μm (e). f, g, Survival (f) and disease score on day 6 (g) of f/f TCRδ−/− and ΔIEC TCRδ−/− mice injected intravenously with 40 μg/mouse of wild-type or Y8K:Y11K rAPI5 protein on day 0, 3, and 6, while treated with 5% DSS for 6 days. n=9 (f/f TCRδ−/− rAPI5WT), 8 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/− rAPI5WT), 6 (f/f TCRδ−/− rAPI5Y8K:Y11K), and 7 (ΔIEC TCRδ−/− rAPI5Y8K:Y11K). An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (a, c, e, g). Mantel-Cox log-rank test in (f). Data points in (a), (c), and (e) are individual mice, and data points in (g) are mean of disease scores of viable mice. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Generation and additional characterization of Api5-knockout mice.

a, Schematic strategy for the generation and genotyping of Api5 knockout mouse. The CRISPR-Cas9 gene targeting mixture containing sgRNAs #1 and #2 targeting exon 1 of Api5 and Cas9 mRNA were injected into zygotes generated from Atg16L1f/f females impregnated by Atg16L1ΔIEC males. The 23 resulting chimeras were screened through a PAGE-based genotyping approach4 in which amplicons generated using the indicated primers and tail DNA from chimeras and wildtype mice as templates were annealed. Heteroduplexes signifying mismatches between the wildtype sequence and the disrupted locus were used to identify 12 candidate knockout mice. Three candidates were selected for further backcrossing and breeding, one of which successfully produced reproductively viable offspring. b, Representative genotyping gel images. Middle gel shows byproducts from first PCR reaction and annealing process using primers from (a). Since Api5+/+ and Api5−/− mice cannot be distinguished by this approach, their PCR products were denatured and annealed with wild-type B6 tail DNA in a second reaction shown in the right gel, which yields multiple bands in the presence of sequence mismatches in Api5−/− and Api5+/− mice but not Api5+/+ mice. c, Sequencing of the Api5 locus from Api5 mutant mice identified a dinucleotide AT insertion after the third codon that causes a frameshift leading to an early stop codon at amino acid position 30. d, Expected and observed number of offspring mice with indicated genotypes from Atg16L1 flox/flox villinCre+ Api5+/− and Atg16L1 flox/flox villinCre− Api5+/− breeders. e, Proportion of the indicated IEL subpopulations of the small intestine from Api5+/+and Api5+/− mice. n=3 (Api5+/+) and 3 (Api5+/−). f, g, Representative H&E images (f) and quantification (g) of Paneth cells per organoid from Atg16L1ΔIEC (ΔIEC) mice co-cultured with ~5 × 104 γδ or αβ IELs harvested from Api5+/+ or Api5+/− mice. n=30 per condition. h, i, Representative images (h) and viability (i) of small intestinal organoids from ΔIEC mice. Scale bar 50 μm. In organoid experiments, intestinal crypts were harvested from 3 mice per genotype, and the viability assay was performed in triplicate. An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (g, i). Data points in (e) are individual mice, data points in (g) represent individual organoids, and data points in (i) represent organoid viability in each well. Bars represent means ± SEM. At least two independent experiments were performed.

Extended Data Fig. 9 |. Additional characterization of mice deficient in ATG16L1 in Paneth cells.

a, Survival of Atg16L1f/f (f/f) and Atg16L1ΔPC (ΔPC) mice treated with 3% DSS ± MNV-infection. n=13 (f/f), 14 (ΔPC), 18 (f/f +MNV) and 14 (ΔPC +MNV). b, c, Representative images of H&E (b) and quantification of Paneth cells (c) of indicated mice euthanized on day 10 post MNV-infection. Arrowheads indicate Paneth cells. n=5 (f/f), 5 (ΔPC), 10 (f/f +MNV) and 12 (ΔPC +MNV). Scale bar 20 μm. d, e, Representative images (d) and quantification of lysozyme staining (e) of indicated mice euthanized on day 10 post MNV-infection. Arrowheads indicate Paneth cells. n=6 (f/f), 5 (ΔPC), 5 (f/f +MNV) and 6 (ΔPC +MNV). Scale bar 20 μm. f, g, Representative images (f) and viability (g) of small intestinal organoids from f/f and ΔPC mice. Scale bar 400 μm. h, Viability of small intestinal organoids from ΔPC mice stimulated ± 20 ng/ml TNFα and/or 20 μM Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) for 48 hours. i, Viability of small intestinal organoids from ΔPC mice transduced with lentiviruses encoding shRNA targeting Mlkl or nonspecific control and stimulated ± 20 ng/ml TNFα for 48 hours. j, Representative Western blot image of MLKL and β-actin in small intestinal organoids from ΔPC mice after transduction with lentiviruses encoding indicated shRNAs. k, Viability of small intestinal organoids co-cultured for 48 hours with 1 × 105 IELs harvested from naïve WT mice. In organoid experiments, intestinal crypts were harvested from 3 mice per genotype. Mantel-Cox log-rank test in (a). An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (c, e, h). Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test in (g, i, k). Data points in (c) and (e) represent individual mice, data points in (g) are mean of organoid viabilities performed in triplicate, data points in (h), (i), and (k) represent organoid viability in each well. Bars represent means ± SEM, and survival data in (a) are combined results of at least 3 experiments performed independently. At least two independent experiments were performed in (j).

Extended Data Fig. 10 |. rAPI5 protects Atg16L1ΔPC mice against DSS-induced intestinal inflammation.

Atg16L1f/f (f/f) and Atg16L1ΔPC (ΔPC) mice were treated with 5% DSS with or without injection of rAPI5 (either rAPI5WT or rAPI5Y8K; Y11K) on day 0, 3, and 6, and euthanized on day 8. n=5 (f/f), 5 (ΔPC), 7 (f/f rAPI5WT), and 6 (ΔPC rAPI5WT), 5 (f/f rAPI5Y8K; Y11K), and 5 (ΔPC rAPI5Y8K; Y11K). a, Quantification of TNFα in SN harvested from gut explants. b, c, d, e, Representative images of H&E staining (b and d) and quantification of villi length (c) and Paneth cells (e). Scale bar 100 μm (b) and 20 μm (e). An ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in (a, c, e). Data points in (b), (c), and (e) are individual mice. Bars represent means ± SEM, and at least two independent experiments were performed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Tomoe Shiomi and the Center for Biospecimen Research and Development, Histology and Immunohistochemistry laboratory (NYU Langone Health, NIH/NCI P30CA016087) for technical support in preparation of histology slides of human organoids, Marina Burgos da Silva, Yusuke Shono, and Marcel R. M. van den Brink (MSKCC) for their support in TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3 staining, Keenan A Lacey and Victor J Torres (NYU Langone Health) for their support in cytokine quantification, and Sang Yong Kim and Rodent genetic engineering laboratory (RGEL) (NYU Langone Health, NIH/NCI P30CA016087) for generating Api5 knockout mice. We also would like to thank the NYU Langone Health’s Cytometry and Cell Sorting Laboratory (NIH/NCI P30ACA016087) for their assistance with cell sorting, DART Microcopy Lab (NIH/NCI P30CA016087) for their assistance with microscopic analysis, Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory (NIH/NCI P30CA016087) for their assistance with preparation and staining of mouse intestine samples, and Genome Technology Center (NIH/NCI P30CA0167087) for their assistance with single cell RNA-Sequencing analysis. Cartoon images in Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1c, 4f and 8b are adapted from the template “mouse”, “organoid”, “T cell”, and “intestine” by BioRender (2022). Retrieved from https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates.

Grant support

This work was supported in part by US National Institute of Health (NIH) grants HL123340 (K.C.), DK093668 (K.C.), AI140754 (K.C.), AI121244 (K.C.), AI130945 (K.C.), DK124336 (K.C.), DK088199 (R.S.B.); Faculty Scholar grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (K.C.), Synergy Award from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation (K.C.), Senior Research Award from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (K.C.), Research Fellowship Award from Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (Y.M.-I.), and a pilot award from the Takeda-Columbia-NYU Alliance (K.C., S.K.)

Footnotes

DECLARARION OF INTERESTS

K.C. has received research support from Pfizer, Takeda, Pacific Biosciences, Genentech, and Abbvie. K.C. has consulted for or received an honoraria from Puretech Health, Genentech, Abbvie, GentiBio, and Synedgen. K.C. is an inventor on U.S. patent 10,722,600 and provisional patent 62/935,035, and K.C., S.K., A.K., and Y.M-I. on 63/157,225. S.K. was a SAB member and held equity in and received consulting fees from Black Diamond Therapeutics and has received research support from Argenx BVBA, Black Diamond Therapeutics and Puretech Health, and is a co-founder of Revalia Bio.

References

- 1.Cadwell K et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature 456, 259–263 (2008). 10.1038/nature07416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bevins CL, Stange EF & Wehkamp J Decreased Paneth cell defensin expression in ileal Crohn’s disease is independent of inflammation, but linked to the NOD2 1007fs genotype. Gut 58, 882–883; discussion 883–884 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu B et al. Irgm1-deficient mice exhibit Paneth cell abnormalities and increased susceptibility to acute intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305, G573–584 (2013). 10.1152/ajpgi.00071.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VanDussen KL et al. Genetic variants synthesize to produce paneth cell phenotypes that define subtypes of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 146, 200–209 (2014). 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu TC, Gao F, McGovern DP & Stappenbeck TS Spatial and temporal stability of paneth cell phenotypes in Crohn’s disease: implications for prognostic cellular biomarker development. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20, 646–651 (2014). 10.1097/01.MIB.0000442838.21040.d7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bel S et al. Paneth cells secrete lysozyme via secretory autophagy during bacterial infection of the intestine. Science 357, 1047–1052 (2017). 10.1126/science.aal4677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adolph TE et al. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature (2013). 10.1038/nature12599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]