Abstract

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic has resulted in pronounced changes for college students, including shifts in living situations and engagement in virtual environments. Although college drinking decreased at the onset of the pandemic, a nuanced understanding of pandemic‐related changes in drinking contexts and the risks conferred by each context on alcohol use and related consequences have yet to be assessed.

Methods

Secondary data analyses were conducted on screening data from a large parent clinical trial assessing a college student drinking intervention (N = 1669). Participants across six cohorts (from Spring 2020 to Summer 2021) reported on the frequency of drinking in each context (i.e., outside the home, home alone, home with others in‐person, and home with others virtually), typical amount of drinking, and seven alcohol‐related consequence subscales.

Results

Descriptive statistics and negative binomial regressions indicated that the proportion and frequency of drinking at home virtually with others decreased, while drinking outside the home increased from Spring 2020 to Summer 2021. Limited differences were observed in the proportion or frequency of individuals drinking at home alone or at home with others in‐person. Negative binomial and logistic regressions indicated that the frequency of drinking outside the home was most consistently associated with more alcohol‐related consequences (i.e., six of the seven subscales). However, drinking at home was not without risks; drinking home alone was associated with abuse/dependence, personal, social, hangover, and social media consequences; drinking home with others virtually was associated with abuse/dependence and social consequences; drinking home with others in‐person was associated with drunk texting/dialing.

Conclusion

The proportion and frequency of drinking in certain contexts changed during the COVID‐19 pandemic, although drinking outside the home represented the highest risk drinking context across the pandemic. Future prevention and intervention efforts may benefit from considering approaches specific to different drinking contexts.

Keywords: alcohol use, college students, context, COVID‐19

The COVID‐19 pandemic incited changes in environments for college students. Students across six cohorts (Spring 2020 – Summer 2021) reported frequency of drinking outside the home, home alone, home with others in‐person, and home with others virtually. Drinking at home virtually with others decreased, drinking outside the home increased, few changes for drinking home with others in‐person and home alone were observed. Drinking outside the home represented the highest risk drinking context for consequences, followed by drinking at home alone.

INTRODUCTION

On March 11, 2020, the COVID‐19 virus was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020). From its discovery to April 2022, COVID‐19 led to over 80.1 million cases in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022) and created significant societal changes for Americans' daily lives, including lockdown measures and education systems moving to virtual environments. These disruptions evoke questions regarding the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on college students' health and risk behaviors, including alcohol use—specifically the contexts in which it was used—and associated consequences.

Several contextual factors associated with risk for college student drinking have been affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic. Typically, students are provided with less parental oversight while in college, and this increased autonomy can be associated with more risk‐taking behaviors, including heavy alcohol use (Calhoun et al., 2018; Fromme et al., 2008). College students report few barriers in accessing alcohol (Wechsler & Nelson, 2008; Williams et al., 2018), and students may increase their alcohol use to facilitate new social bonds when transitioning to college (Baer, 2002; Brown & Murphy, 2020; Stewart et al., 2006). The increased autonomy and decreased supervision college typically affords was likely removed for students who moved back with their parents or family when campuses canceled in‐person classes and/or did not allow students on campus. Several studies showed reduced drinking for college students at the onset of the pandemic (Bollen et al., 2022; Bonar et al., 2021) with more pronounced decreases for students who had moved (Jaffe et al., 2021; White et al., 2020). Students who remained on campus or moved into a private residence were still impacted by state‐level restrictions (i.e., lockdown regulations; safety guidelines) on where they could go and how many people they could be with. Thus, the onset of the pandemic may have impacted student drinking outcomes by affecting the contexts in which students could drink. However, a comprehensive understanding of these drinking contexts is lacking.

During lockdown, many activities moved to a virtual environment including classes, work, and entertainment. Use of video conferencing platforms such as Zoom and FaceTime increased dramatically (Koeze & Popper, 2020). Lockdown restrictions may have decreased in‐person social interactions typically associated with increased drinking for college students, while other contexts may have emerged or become more relevant—specifically drinking alone and drinking with others in virtual settings. Research on drinking contexts during the pandemic has been minimal and rarely focused on college students. Early in the pandemic, 49% of Canadian adolescents reported using substances alone, 32% used with friends in virtual settings, and 24% reported using in face‐to‐face settings (Dumas et al., 2020). Another study assessing adults who attended electronic dance music (EDM) events prior to the pandemic found that during the pandemic, more than half attended virtual raves and 70% attended virtual happy hours; during virtual raves and happy hours, 60% and 80% reported using alcohol or other drugs, respectively (Palamar & Acosta, 2021). The one known study to examine changes in endorsement of college student drinking contexts found that from pre‐ to postclosure of a university campus at the pandemic onset, college students' drinking at one's house/home did not change, drinking alone increased, and drinking at parties, bars/restaurants, and others' homes decreased (Jackson et al., 2021). Notably, this study did not assess drinking with others in virtual settings (e.g., virtual happy hours). Although these studies focused on the onset of the pandemic, over 2 years have now passed since the start of the COVID‐19 pandemic. During this time, there has been substantial variability in lockdown regulations, availability and uptake in COVID‐19 vaccines, and surges in cases of COVID‐19 and its variants. Given these changes, it is prudent to assess how college students' drinking contexts may have continued to shift since the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic, as this may indicate times of increased or differential risk for drinking in different contexts.

Drinking contexts are important to understand because they may confer different levels of risk—both for alcohol consumption and related consequences (Bersamin et al., 2012; Huckle et al., 2016). College students' drinking commonly occurs in social settings, with social motives frequently endorsed (LaBrie et al., 2007). Higher reports of social drinking motives have been associated with greater alcohol consumption and consequences (Engels et al., 2005; Vaughan et al., 2009). Thus, drinking in settings with others present (especially outside the home) may provide risky environments for increased drinking and consequences through the social influences of peers. In contrast to social drinking, drinking alone is associated with drinking to cope motivations and expecting alcohol will reduce tension and negative emotions (Creswell, 2021). Drinking alone has been associated with greater alcohol use and related problems, including dependence symptoms (Gonzalez & Skewes, 2013; see Skrzynski & Creswell, 2021 for review). Some research suggests drinking alone, and not social drinking, has a direct association with alcohol‐related consequences (Corbin et al., 2020; Fleming et al., 2021; Waddell et al., 2021). One of the only studies to examine the effects of social and solitary drinking contexts during the COVID‐19 pandemic indicated increased drinking alone—but not changes in drinking with friends—was associated with increased alcohol use and consequences (Dyar et al., 2021). Collectively, this research supports increased risk for both drinking with others and drinking alone.

Virtual environments provide an additional context unique from drinking in‐person inside or outside the home and drinking alone. While virtual environments became a large part of many college students' lives during the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is unclear how virtual environments may provide similar or differential risk from other drinking contexts. There is a dearth of literature examining drinking with others in virtual settings. Drinking in virtual environments, such as virtual happy hours, occurs socially with others; however, it is unknown if social factors provide a similar influence to drinking with others in‐person or if it is more similar to drinking alone since others are not physically present.

The current study utilized a cross‐sectional panel design from March 2020 to September 2021 to assess drinking contexts, alcohol use, and alcohol‐related consequences in a sample of college students. First, we assessed changes over time in endorsement and frequency of drinking in various contexts, including drinking outside the home, at home with others in‐person, at home with others virtually, and at home alone. We expected differences in reports of drinking contexts across cohorts with fewer reports of drinking outside the home and more drinking at home (both alone and in virtual settings) occurring at the onset of the pandemic—when more restrictions were in place—followed by more reports of drinking outside the home later in the pandemic, when these restrictions were relaxed. Additionally, we examined how frequency of drinking in each context was associated with quantity of alcohol use and alcohol‐related consequences. Due to the importance of social motives for college student drinking (LaBrie et al., 2007), we hypothesized higher frequencies of drinking with others in‐person would be associated with increased alcohol use and consequences. Despite recent research indicating parents may have been more permissive of drinking at the home for their adolescent children during the pandemic (Maggs et al., 2021), we hypothesized drinking outside the home provided a riskier context than drinking at home with others in‐person and thus would be associated with more types of alcohol‐related consequences. Given the heightened risk profile associated with drinking alone (Corbin et al., 2020; Creswell, 2021; Dyar et al., 2021), we hypothesized drinking alone more frequently during the COVID‐19 pandemic would be associated with more alcohol consumption and related consequences. Given the paucity of research examining drinking in virtual settings, associations between frequency of drinking in virtual settings and alcohol use and related consequences were explored. Additionally, we explored associations between drinking frequency in each of these four contexts and specific types of alcohol‐related consequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedure

Students from a large public university in Washington State were randomly invited from the registrar's list if they were in their 1st or 2nd year of college and their birthday fell within a range of 2–4 months specific to the design of the parent study (clinical trial registration #NCT04030325). Invited students received an email explaining the study and a personalized link to the screening survey of the parent study. A total of 3802 students completed screening (34.8% response rate) across eight cohorts recruited between Fall of 2019 and Summer of 2021. Due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, pandemic‐related adaptations and additions (including drinking context items) were made to the measures starting with the third cohort in Spring 2020. Therefore, the current study utilizes screening data (preintervention in the parent study) from six cohorts between Spring 2020 and Summer 2021 (see Table 1 for recruitment dates) providing a cohort‐sequential design. Given the focus of the current study on drinking contexts, only participants who reported drinking at least once in the past month (n = 1669) were included for analyses. All procedures were approved by the university's Institutional Review Board.

TABLE 1.

Demographic information

| Variable | Responses (n = 1669) |

|---|---|

| Cohorts | |

| Spring 2020 (04/23–05/23) | 270 (16.18%) |

| Summer 2020 (08/20–09/19) | 314 (18.81%) |

| Fall 2020 (10/22–11/20) | 126 (7.55%) |

| Winter 2021 (01/10–02/09) | 303 (18.15%) |

| Spring 2021 (04/23–05/23) | 320 (19.17%) |

| Summer 2021 (08/20–09/19) | 336 (20.13%) |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 19.11 (0.97) |

| Race | |

| Racial Minority | 264 (15.82%) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 18 (1.08%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 9 (0.54%) |

| Black/African American | 31 (1.86%) |

| Multiracial | 164 (9.83%) |

| Other | 42 (2.52%) |

| Asian/Asian‐American | 447 (26.78%) |

| White/Caucasian | 952 (57.04%) |

| Missing | 6 (0.36%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 183 (10.97%) |

| White/Caucasian | 97 (5.81%) |

| Asian/Asian American | 5 (0.30%) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 11 (0.66%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.06%) |

| Black/African American | 2 (0.12%) |

| Multiracial | 31 (1.86%) |

| Other | 30 (1.80%) |

| Missing Race | 6 (0.36%) |

| White/Caucasian, non‐Hispanic or Latino/a | 854 (51.17%) |

| Asian/Asian American, non‐Hispanic or Latino/a | 441 (26.42%) |

| Racially Diverse, non‐Hispanic or Latino/a | 188 (%) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 7 (0.42%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 8 (0.48%) |

| Black/African American | 29 (1.74%) |

| Multiracial | 132 (7.91%) |

| Other | 12 (0.72%) |

| Missing | 3 (0.18%) |

| Sex Assigned at Birth | |

| Male | 597 (35.77%) |

| Female | 1070 (64.11%) |

| Missing | 2 (0.12%) |

| Gender | |

| Gender Minority | 40 (2.40%) |

| Transwoman | 1 (0.06%) |

| Transman | 7 (0.42%) |

| Genderqueer/gender nonconforming | 24 (1.44%) |

| Not listed/prefer not to answer | 8 (0.48%) |

| Cisgender | 1628 (97.54%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.06%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Sexual Orientation Minority | 430 (25.76%) |

| Bisexual/Pansexual | 268 (16.06%) |

| Gay | 47 (2.82%) |

| Lesbian | 27 (1.62%) |

| Queer | 3 (0.18%) |

| Asexual | 3 (0.18%) |

| Questioning | 50 (3.00%) |

| Not listed/prefer not to answer | 32 (1.92%) |

| Straight/Heterosexual | 1239 (74.24%) |

| Living Situation | |

| On campus | 244 (14.62%) |

| Off‐campus without parents | 706 (42.30%) |

| At home with parents | 702 (42.06%) |

| Missing | 17 (1.02%) |

Regarding context during data collection, the first COVID‐19 case in Washington State was officially reported on January 21, 2020. Governor Jay Inslee declared a state of emergency in Washington State on February 29, 2020 (Proclamation No. 20–05, 2020). The current study's university moved to virtual classes beginning March 9, 2020, which continued through Fall 2021. Thus, all the study's participants were recruited while classes were conducted virtually (with a few exceptions for lab‐based classes). The “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order was executed by Governor Inslee on March 23, 2020, and remained effective through May 2020, after which a phase‐based opening was instituted. These orders greatly reduced outings, only allowing those who pursue an essential activity, work, or exercise outdoors to leave their homes. No counties began the re‐opening phase until October 2020, which allowed some counties to reinstate in‐door dining at 50% capacity (MyNorthwest, 2021). Specifics of phases changed over time, but all counties reinstated indoor dining at 50% capacity in March 2021, and all restrictions (except for large‐scale indoor events) were removed as of June 30, 2021.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported on their age, sex assigned at birth, race, ethnicity (i.e., Hispanic/Latinx or non‐Hispanic), gender, sexual orientation, and living situation. Based on distribution of responses, race and ethnicity was recoded into four categories of non‐Hispanic (NH) White, NH Asian/Asian‐American, Hispanic, and NH racial minority (i.e., American Indian/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Black/African‐American, Multiracial, Other). Gender minority status was created by recoding gender into two categories: cis‐gender (i.e., woman, man) and trans/gender diverse (TGD; i.e., transwoman, transman, genderqueer/gender nonconforming, not listed/prefer not to answer). Similarly, sexual minority status was created by recoding sexual orientation into two categories: straight/heterosexual and sexual minority (i.e., bisexual/pansexual, gay, lesbian, queer, asexual, questioning, not listed/prefer not to answer). See Table 1 for details of the demographic distributions.

Living situation

To assess living situation, participants were asked “As of today, where do you currently live.” Response options were recoded to (1) on‐campus (i.e., “In an on‐campus/school residence hall,”), (2) off‐campus without parents (i.e., “In an off‐campus residence hall that is owned by the college,” “In fraternity/sorority housing,” or “In an apartment/house/residence that is not campus‐owned (not with parents)”), and (3) off‐campus with parents (i.e., “At home, with my parents,”). Participants were also given the option “Somewhere else” followed by an open‐ended response option. Due to the small sample and lack of clarity in answers, those who reported “Somewhere else” (n = 16) were recoded as missing.

Drinking context frequency

Drinking context was measured by 10 items asking how often participants consumed alcohol in different locations during the COVID‐19 pandemic over the past month. Responses were on a nine‐point scale including, 0 (Never), 4 (2 days a week), and 8 (Multiple times a day) and were recoded to represent number of past 28‐day drinking days based on the maximum number in a response option of the scale. For example, “Once a month” was recoded as 1 time, and “3‐4 days a week” was recoded as 16 times in the past 28 days (i.e., 4 times per week multiplied by 4 weeks per 28 days). Response options “Every day” and “Multiple times a day” were both recoded to 28 days.

Drinking frequency was examined in four overarching contexts of interest: (1) Drinking outside the home (i.e., “In a bar/restaurant,” “In a public outdoor space (e.g., lake, park, etc.),” “At a party with more than 10 in‐person attendees,” “At a friend's house”), (2) Drinking at home with other people in‐person (i.e., “At your house with friends present,” “At your house with family present”), (3) Drinking at home with other people virtually (i.e., “At a virtual party (e.g., Zoom party) including both friends and other people (strangers or people you don't know well),” “At your house with friends virtually present (e.g., Skype/FaceTime/Zoom),” “At your house with family virtually present (e.g., Skype/FaceTime/Zoom)”), and (4) Drinking at home alone (i.e., “At your house alone”). Because we were interested in drinking frequencies across any context listed within the items, each context variable was calculated by taking the maximum 1 drinking frequency value on any item within each subscale. For example, if a participant reported they drank “3–4 times a week” in a bar/restaurant and “never” in a public outdoor space, drinking frequency for “Drinking outside the home” was recorded as 3–4 week (recoded to 16 times in the past 28 days as described above). Thus, the four resulting context variables represent the maximum frequency of drinking in each context over the past 28 days. (See Appendix S1 for full list of original and recoded response options).

Typical drinking frequency

Participants reported on number of days per week they drank alcohol in the past month on a scale ranging from 0 (I do not drink at all) to 11 (Every day). These responses were recoded to be on a similar metric as Drinking Context Frequency, such that responses reflected the number of days drank in the past 28 days (0 to 28).

Typical drinking quantity

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985) was used to measure how much alcohol, on average, participants drank on each day of a typical week in the past month. Participants were provided with a standard drink definition. The number of drinks for each day was summed to create a composite score of the number of alcohol drinks consumed in a typical week.

Alcohol‐related consequences

Alcohol‐related consequences were assessed with items from the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989). Consistent with past research (Martens et al., 2007; Patrick et al., 2011), index scores were used to create three subscales (Abuse/Dependence, Personal, Social) detailed below. Additional consequence items were assessed to create additional subscales detailed below. All consequences assessed past month experiences on a scale from 0 (Never) to 4 (More than 10 times). Items were recoded using a similar procedure to drinking frequency variables utilizing the higher value within a response option range to represent the number of consequences in the past month (i.e., Never = 0; 1 to 2 times = 2; 3 to 5 times = 5). Response options 6 to 10 times and More than 10 times were both recoded to 10.

Abuse/dependence consequences

Twelve items from the RAPI abuse/dependence subscale were assessed and summed to create a total score (α = 0.83). Example items included “Felt that you needed more alcohol than you used to use in order to get the same effect?” and “Was told by a friend or neighbor to stop or cut down on drinking?”

Personal consequences

Personal consequences were measured using the 7‐item RAPI subscale which was summed to calculate a total score (e.g., “Not able to do your homework or study for a test?”, “Missed out on other things because you spent too much money on alcohol?”; α = 0.80).

Social consequences

Social consequences were calculated by summing the four‐item RAPI social subscale yielding a total score (e.g., “Got into fights, acted bad, or did mean things?”, “Caused shame or embarrassment to someone?”; α = 0.76).

Driving under the influence

Participants reported how many times they drove shortly after having: (1) one drink, (2) more than two drinks, and (3) more than 4 drinks (Neighbors et al., 2019; α = 0.74). Because more than 90% of the responses were 0 (Never) or 1 (1 to 2 times), responses were dichotomized to differentiate never (0) from any (1+) driving after drinking.

Hangover consequences

Two items from the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Scale were used to assess hangovers (Hurlburt & Sher, 1992): “Have you had a headache (hangover) the morning after you had been drinking?” and “Have you felt very sick to your stomach or thrown up after drinking?” Responses were summed to create a composite score (α = 0.74).

Drunk texting/dialing consequences

Participants were asked how often they drunk text/dialed. Response options varied from 1 (Never) to 4 (More than 10 times).

Social media consequences

Participants answered a single item regarding how often they posted something they regretted on social media while they were drinking or because of their alcohol use. Because more than 90% of the responses were 0 (Never) or 1 (1 to 2 times), responses were dichotomized such that values greater than 1 were recoded to 1.

Data analyses

To assess differences in drinking in each context over time, average cohort‐specific drinking frequencies were examined by cohort. Additionally, the percentage of students in each cohort who endorsed any drinking in each context was examined descriptively. Although frequency response options were ordinal, values reflect counts, and data were overdispersed. Therefore, following McGinley et al. (2015) recommendations, negative binomial regressions were used to assess significant cohort differences in frequency of drinking in each context. Covariates included age, race/ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, TGD status, sexual minority status, and living situation as these factors have been associated with alcohol use or disparate impacts from COVID‐19 (McKnight‐Eily et al., 2021; Pollard et al., 2020; Salerno et al., 2020; SAMHSA, 2020; White et al., 2020). To evaluate differences in cohorts (when adjusting for covariates), pairwise comparisons were conducted using the emmeans package (Lenth, 2022) in R (R Core Team, 2022). The p‐values in each pairwise comparison used the Tukey method to adjust for comparing a family of 6 estimates (i.e., cohorts). Then, p‐values with a Bonferroni adjustment (p < 0.0125) were used to determine significant cohort differences for each of the 4 contexts. To determine if differences among cohorts in the frequency of drinking within each context followed a similar pattern to typical drinking frequency, a negative binomial model and pairwise comparisons using the same alpha adjustments were conducted to assess for differences between cohorts in typical drinking frequency that included the same covariates as previous negative binomial models.

Lastly, regression models were used to assess the associations between frequency of drinking in each context and drinking quantity and consequences. Six separate negative binomial regression models were conducted to assess each of the four drinking contexts (i.e., drinking outside the home, drinking at home virtually, drinking at home in‐person, drinking at home alone) as predictors of typical weekly drinking quantity and dependence/abuse, personal, social, hangover, and social media consequence subscales. Similar to previous models, the outcomes were overdispersed and contained count data, and therefore negative binomial models were utilized. Logistic regression was used to examine the associations between drinking in each context and both the driving after drinking and drunk texting/dialing consequence outcomes. In the drinking quantity model, covariates included living situation, sexual minority status, race, TGD status, sex assigned at birth, ethnicity, age, and indicator‐coded cohort with Spring 2020 (first assessment during the pandemic) as the reference. All seven consequence models included the aforementioned covariates and also included typical drinking quantity. Each of the regressions was conducted using glmmTMB in R (Brooks et al., 2017). Coefficients in each model were exponentiated to calculate incident rate ratios for negative binomial regressions and odds ratios for logistic regressions. Of note, missingness was minimal, with only 0.32% of the data missing; being less than 5%, this amount of missingness was deemed negligible (Schafer, 1999).

RESULTS

Characterizing drinking contexts across cohorts

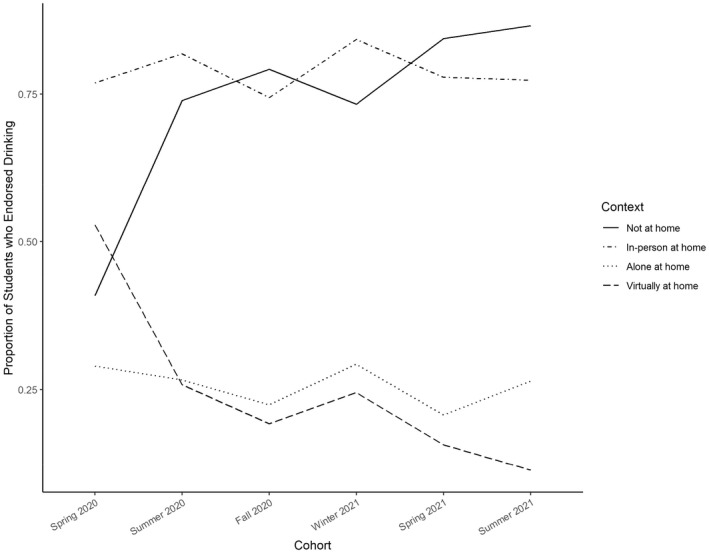

Descriptives for individual drinking context items as well as the four collapsed drinking contexts by cohort are reported in Table 2. Differences in the proportion of individuals endorsing any drinking in each context are shown in Figure 1. From Spring 2020 to Summer 2021, the proportion of individuals drinking at home virtually with others appeared to decrease (53% to 11%) and drinking outside the home increased (41% to 87%). Notably, no trends of change across cohorts were observed for individuals drinking at home alone (Range: 20.7% to 29.0%), nor drinking at home in‐person (Range: 76.9% to 84.2%).

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics for drinking in each context by cohort

| Variable | Cohort | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring 2020 | Summer 2020 | Fall 2020 | Winter 2021 | Spring 2021 | Summer 2021 | |||||||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

| Typical Drinking Frequency | 5.08 | 4.81 | 0–24 | 4.60 | 5.17 | 0–28 | 4.06 | 3.70 | 0–16 | 4.18 | 4.32 | 0–24 | 5.32 | 5.04 | 0–28 | 5.01 | 5.21 | 0–28 |

| Drinking Frequency in Different Contexts | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Outside the Home | 1.26 | 2.81 | 0–24 | 2.96 | 4.28 | 0–28 | 2.54 | 2.89 | 0–16 | 2.99 | 4.12 | 0–24 | 4.07 | 5.18 | 0–28 | 4.18 | 5.21 | 0–28 |

| In a bar/restaurant | 0.15 | 1.52 | 0–24 | 0.55 | 1.72 | 0–16 | 0.52 | 1.39 | 0–8 | 0.44 | 1.86 | 0–16 | 1.02 | 2.24 | 0–16 | 1.28 | 2.52 | 0–24 |

| In a public outdoor space (e.g., lake, park) | 0.54 | 1.79 | 0–16 | 1.42 | 2.81 | 0–16 | 0.98 | 2.25 | 0–16 | 1.00 | 2.73 | 0–24 | 1.40 | 3.40 | 0–28 | 1.36 | 2.79 | 0–28 |

| At a party with more than 10 in‐person attendees | 0.15 | 0.72 | 0–8 | 0.99 | 3.41 | 0–28 | 0.76 | 1.64 | 0–8 | 0.99 | 2.55 | 0–16 | 2.17 | 4.19 | 0–24 | 2.27 | 4.19 | 0–28 |

| At a friend's house | 0.73 | 1.88 | 0–16 | 1.76 | 2.49 | 0–16 | 1.98 | 2.44 | 0–16 | 2.18 | 3.29 | 0–16 | 2.50 | 3.70 | 0–28 | 2.74 | 3.75 | 0–24 |

| 2. Virtually at Home | 1.81 | 3.07 | 0–28 | 0.94 | 2.96 | 0–24 | 0.99 | 3.73 | 0–28 | 0.88 | 3.15 | 0–28 | 0.68 | 2.72 | 0–28 | 0.56 | 2.69 | 0.24 |

| At a virtual party (e.g., Zoom party) including both friends and other people (strangers or people you do not know well) | 1.41 | 2.61 | 0–24 | 0.66 | 2.52 | 0–24 | 0.66 | 2.78 | 0–28 | 0.51 | 2.32 | 0–28 | 0.33 | 1.49 | 0–16 | 0.16 | 1.01 | 0–16 |

| At your house with friends virtually present (e.g., Skype/FaceTime/Zoom) | 1.56 | 2.72 | 0–28 | 0.70 | 2.41 | 0–16 | 0.52 | 2.13 | 0–16 | 0.56 | 2.36 | 0–28 | 0.46 | 2.31 | 0–28 | 0.39 | 2.17 | 0–24 |

| At your house with family virtually present (e.g., Skype/FaceTime/Zoom) | 0.34 | 1.60 | 0–16 | 0.18 | 1.49 | 0–24 | 0.32 | 2.22 | 0–24 | 0.30 | 2.05 | 0–28 | 0.20 | 1.07 | 0–8 | 0.26 | 1.95 | 0–24 |

| 3. In‐person at Home | 4.30 | 5.61 | 0–28 | 3.90 | 5.88 | 0–28 | 2.81 | 4.33 | 0–28 | 3.48 | 4.97 | 0–28 | 3.59 | 4.89 | 0–28 | 3.90 | 5.76 | 0–28 |

| At your house with friends present | 1.11 | 2.89 | 0–24 | 2.12 | 3.97 | 0–28 | 2.22 | 3.75 | 0–24 | 2.18 | 3.91 | 0–28 | 2.90 | 4.27 | 0–28 | 2.98 | 5.18 | 0–28 |

| At your house with family present | 3.61 | 5.46 | 0–28 | 2.47 | 5.14 | 0–28 | 1.10 | 3.08 | 0–28 | 2.03 | 4.04 | 0–28 | 1.22 | 3.15 | 0–28 | 1.88 | 3.99 | 0–28 |

| 4. Home Alone | 0.98 | 2.48 | 0–16 | 0.99 | 3.29 | 0–28 | 0.91 | 2.50 | 0–16 | 1.39 | 4.49 | 0–28 | 0.69 | 2.52 | 0–28 | 0.95 | 2.71 | 0–28 |

Note: This table shows the mean, standard deviation, and range for the maximum frequency of drinking for participants in each context for each cohort.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of students drinking in each context during the COVID‐19 pandemic. This figure displays trends over time of the proportion of participants in each cohort who reported drinking in each context.

After controlling for all covariates (i.e., age, sex assigned at birth, race, ethnicity, TGD and sexual minority statuses, and living situation), the negative binomial regressions showed significant cohort differences in drinking outside the home, drinking at home virtually, and in‐person at home (Tables S1–S4). There were no significant differences across cohorts for frequencies of drinking at home alone. Cohort comparisons revealed that compared to Spring 2020, all later cohorts drank more frequently outside the home. Greater drinking outside the home over time was also indicated by a significantly higher frequency in Spring 2021 compared to Fall 2020, and Summer of 2021 compared to Summer 2020, Fall 2020, and Winter 2021. Conversely, for cohort differences in frequency of drinking virtually at home, participants in Spring 2020 reported significantly higher frequencies compared to three later cohorts: Summer 2020, Spring 2021, and Summer 2021. Compared to the Spring 2020 cohort, the Fall 2020 cohort drank significantly less in‐person. All other cohort comparisons for drinking context frequencies were not statistically significant. There were significant cohort differences in typical drinking frequency (Table S5). Pairwise comparisons revealed the Spring 2020 cohort reported higher typical drinking frequency than Fall 2020 and Winter 2021. No other significant cohort comparisons were observed.

Associated outcomes of drinking contexts

Aggregating across cohorts, the mean, standard deviation, and correlations for drinking in each context, typical alcohol use, and consequences subscales are provided in Table 3. Drinking frequencies in various contexts were examined as conditional predictors of alcohol consumption and consequences (see Table 4). Controlling for the same covariates, drinking outside the home and drinking at home in‐person were associated with more consumption. Drinking outside the home, drinking at home virtually, and drinking at home alone were associated with abuse/dependence consequences. Drinking outside the home and drinking at home alone were associated with more personal consequences. More frequent drinking outside the home, at home virtually, and at home alone were associated with more social consequences. None of the drinking contexts uniquely predicted driving after drinking consequences. Drinking outside the home and drinking at home alone were associated with more hangover consequences. Drinking outside the home and at home in‐person was uniquely associated with more drunk texting or dialing. Lastly, drinking outside the home and drinking at home alone were associated with more frequent regretted social media posting.

TABLE 3.

Mean, standard deviations, and correlations for drinking contexts, alcohol use, and consequence subscales

| Variable | M | SD | Correlations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |||

| 1. Outside the home | 3.12 | 4.47 | ‐ | ||||||||||

| 2. At home virtually | 0.95 | 3.01 | 0.17*** | ‐ | |||||||||

| 3. At home in person | 3.75 | 5.37 | 0.45*** | 0.25*** | ‐ | ||||||||

| 4. At home alone | 0.99 | 3.14 | 0.19*** | 0.35*** | 0.29*** | ‐ | |||||||

| 5. Alcohol Use | 6.09 | 8.71 | 0.54*** | 0.08*** | 0.42*** | 0.05* | ‐ | ||||||

| 6. Abuse/ dependence | 3.68 | 8.41 | 0.30*** | 0.22*** | 0.26*** | 0.24*** | 0.36*** | ‐ | |||||

| 7. Personal | 2.63 | 5.65 | 0.33*** | 0.16*** | 0.23*** | 0.16*** | 0.41*** | 0.74*** | ‐ | ||||

| 8. Social | 1.47 | 3.07 | 0.32*** | 0.17*** | 0.22*** | 0.14*** | 0.33*** | 0.64*** | 0.64*** | ‐ | |||

| 9. Driving | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.15*** | 0.05* | 0.14*** | 0.07** | 0.15*** | 0.21*** | 0.22*** | 0.21*** | ‐ | ||

| 10. Hangover | 3.16 | 3.95 | 0.43*** | 0.12*** | 0.30*** | 0.13*** | 0.56*** | 0.46*** | 0.55*** | 0.48*** | 0.17*** | ‐ | |

| 11. Drunk texting/dialing | 1.45 | 2.34 | 0.28*** | 0.11*** | 0.27*** | 0.10*** | 0.41*** | 0.41*** | 0.45*** | 0.39*** | 0.09*** | 0.48*** | ‐ |

| 12. Social Media | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.17*** | 0.09*** | 0.16*** | 0.12*** | 0.17*** | 0.29*** | 0.33*** | 0.26*** | 0.10*** | 0.29*** | 0.35* |

Note: Drinking contexts assess the maximum frequency of drinking for participants in each context; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

TABLE 4.

Results from negative binomial and logistic regression models assess associations between drinking contexts and alcohol use and alcohol‐related consequences

| Alcohol Quantity | Consequences | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abuse/Dependence | Personal | Social | Driving | Hangover | Drunk Texting/Dialing | Social Media | ||

| Predictors | IRR | IRR | IRR | IRR | OR | IRR | IRR | OR |

| Drinking Context | ||||||||

| Outside the home | 1.09*** | 1.04* | 1.04** | 1.05** | 1.00 | 1.03** | 1.02* | 1.05* |

| (1.08–1.11) | (1.01–1.07) | (1.01–1.07) | (1.02–1.08) | (0.95–1.05) | (1.01–1.04) | (1.004–1.05) | (1.01–1.08) | |

| Virtually at home | 1.01 | 1.04* | 1.04 | 1.04* | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| (0.99–1.03) | (1.001–1.08) | (1.00–1.08) | (1.0003–1.09) | (1.00–1.06) | (1.00–1.04) | (0.98–1.04) | (0.96–1.05) | |

| In‐person at home | 1.04*** | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.02* | 1.02 |

| (1.03–1.06) | (1.00–1.04) | (0.98–1.02) | (0.97–1.01) | (0.99–1.08) | (0.99–1.02) | (1.01–1.04) | (0.99–1.05) | |

| Alone at home | 1.02 | 1.08*** | 1.06*** | 1.05* | 1.03 | 1.03** | 1.02 | 1.05* |

| (1.00–1.03) | (1.04–1.13) | (1.02–1.10) | (1.01–1.09) | (0.98–1.08) | (1.01–1.04) | (0.99–1.05) | (1.01–1.10) | |

| Cohort | ||||||||

| Spring 2020 | REF | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Summer 2020 | 0.62** | 0.62** | 0.56*** | 0.87 | 1.66 | 0.91 | 0.70* | 0.58* |

| (0.45–0.87) | (0.45–0.87) | (0.41–0.77) | (0.61–1.25) | (0.81–3.03) | (0.75–1.11) | (0.53–0.92) | (0.34–0.99) | |

| Fall 2020 | 0.78* | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.95 | 0.66* | 0.67 |

| (0.63–0.97) | (0.56–1.28) | (0.57–1.26) | (0.49–1.21) | (0.24–1.92) | (0.74–122) | (0.46–0.95) | (0.34–1.29) | |

| Winter 2021 | 0.62*** | 0.71 | 0.61** | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.73* | 0.66 |

| (0.53–0.74) | (0.55–1.00) | (0.44–0.85) | (0.69–1.43) | (0.44–1.81) | (0.77–1.15) | (0.55–0.97) | (0.39–1.11) | |

| Spring 2021 | 0.77** | 0.79 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.65** | 0.56* |

| (0.65–0.91) | (0.61–1.18) | (0.70–1.32) | (0.57–1.17) | (0.44–1.76) | (0.85–1.26) | (0.49–0.86) | (0.34–1.01) | |

| Summer 2021 | 0.68*** | 0.88 | 0.68** | 1.03 | 1.88* | 1.05 | 0.63** | 0.59 |

| (0.57–0.80) | (0.67–1.16) | (0.50–0.94) | (0.72–1.48) | (1.03–3.44) | (0.86–1.28) | (0.47–0.84) | (0.34–1.01) | |

| Observations | 1629 | 1617 | 1628 | 1628 | 1627 | 1629 | 1629 | 1629 |

Note: Incidence Rate Ratios (IRR)/Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals for model depending on distribution of outcome. All models control for age, race, ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, TGD status, sexual minority status, and living situation. Drinking context variables represent the past‐month frequency of drinking in each context. All consequence models also control for Alcohol Quantity; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.00.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies to assess differences in endorsement and frequency of drinking within various contexts during the COVID‐19 pandemic and relations between these contexts and typical drinking and alcohol‐related consequences. We anticipated drinking alone and drinking in virtual environments to be greatest at the onset of the pandemic and drinking outside of the home would be higher as the pandemic progressed. Consistent with research finding an increase in drinking in virtual contexts at the onset of the pandemic (Dumas et al., 2020; Palamar & Acosta, 2021), students reported the highest frequency of drinking at home with others virtually in Spring 2020. Over time, fewer students reported drinking in virtual settings and more students reported drinking outside their home. This may reflect virtual happy hours, and other online drinking events were largely an initial response to pandemic‐related constraints but did not have the staying power of other changes brought on by the pandemic (e.g., remote work). Beginning in Summer 2020, frequency of drinking outside the home was higher than Spring 2020, suggesting students returned to drinking outside their homes quickly as pandemic restrictions were relaxed, reflecting preferences for in‐person drinking contexts. By Spring 2021, the majority of participants (87%) reported drinking outside their home. Only one cohort difference was observed for drinking at home in‐person: Spring 2020 was significantly higher than Fall 2020. Following a reduction in cases, there was a surge of cases Washington State starting in Fall of 2020 (Washington State Department of Health, 2021), which may have influenced a reduction of drinking at home with others. Despite observed changes in other drinking contexts and COVID‐related changes in regulations and vaccines during this time, no other differences among cohorts in drinking at home in‐person or drinking home alone were observed. Importantly, when comparing differences in frequency of drinking in specific contexts to typical drinking frequency, differential patterns emerged. Similar to drinking alone and drinking at home with others in‐person, typical drinking frequency largely did not differ across cohorts (with the exception that the Spring 2020 cohort reported drinking more frequently than the Fall 2020 and Winter 2021 cohorts). This indicates a lack of systematic change in overall frequency of drinking across cohorts, but some contexts in which students drank significantly shifted across the first year and a half of the pandemic.

These drinking contexts also differentially related to the quantity of alcohol use and alcohol‐related consequences. Our hypotheses that drinking more frequently with others in‐person, both at home and outside the home, would be associated with greater alcohol use was supported. This is consistent with prior work suggesting college students report more alcohol use when in social groups compared to when they are alone (Cullum et al., 2012; Varela & Pritchard, 2011). Interestingly, drinking more frequently with people virtually was not associated with greater alcohol use. Given the dearth of literature on virtual drinking contexts, it was unclear if social groups in virtual contexts would have similar drinking patterns as in‐person social groups. It is possible certain mechanisms which contribute to more drinking in groups, like drink matching (Peterson et al., 2005), may have a reduced impact in virtual environments.

Drinking contexts were differentially related to risks for alcohol‐related consequences after accounting for alcohol use, demographic variables, and living situation. We anticipated more frequent drinking outside the home and home alone would both be associated with greater risk for alcohol‐related consequences. Supporting these ideas, more frequent drinking outside the home was associated with the greatest range of consequences. Drinking outside the home may introduce more opportunities for risk‐taking behavior and experiencing consequences. This context reflects the range of consequences experienced in college environments influenced by drinking for social facilitation (Baer, 2002) without significant parental supervision (Arnett, 2014; Fromme et al., 2008). Additionally, leaving home to socialize early in the pandemic before vaccines were available may have been a risky behavior itself. Therefore, students choosing to drink outside the home may have a greater propensity for risk‐taking, and this propensity has been associated with increased alcohol use and consequences (Lejuez et al., 2002; Padovano et al., 2019; Treloar et al., 2015). Presumably, both the environments in which students drank outside their home and self‐selection to leave home during a pandemic contributed to the range of consequences students experienced.

While drinking outside the home likely contributes to alcohol consequences related to social motivations for drinking in this context, it appears this context does not fully explain the breadth of consequences experienced. Drinking more frequently at home with others in‐person was only associated with one subscale: drunk texting or calling. This may be indicative that those who drank at home with others wanted to reach out to those (e.g., friends, partners) who were currently not present. The limited association with consequences could indicate drinking at home with others may be more protective than other contexts, partly due to the characteristics or identities of drinking companions inside the home. Although living situation was controlled for, the presence of parents may have contributed to limiting drinking at home, leading to fewer consequences.

Given the lack of previous research, we did not make specific predictions about how drinking with others virtually would be associated with various alcohol‐related consequences. Results indicated drinking more frequently in a virtual context was associated with greater abuse and dependence consequences, as well as social consequences. Social consequences were also associated with drinking outside the home, but not at home with others in‐person, suggesting having others present virtually may present similar social dynamics to drinking outside the home that contribute to potential negative social experiences. Possibly, students were able to socialize with more people both outside their home and virtually due to limitations in the number of people allowed to gather indoors during COVID‐related restrictions. This is consistent with virtual environments replacing larger gatherings such as raves and happy hours (Palamar & Acosta, 2021), while drinking with others at home may have been limited to family, roommates, or a small group of friends. Additionally, virtual settings may provide an environment where people are more likely to engage in behaviors with social consequences, such as getting into fights and causing embarrassment, because they are not physically with others and may feel less pressure to engage in prosocial behaviors. Further research is needed to understand whether this pattern of consequences would be consistent for virtual drinking environments independent of the pandemic.

Finally, we expected drinking alone to be associated with more alcohol‐related consequences. This hypothesis was partially supported with drinking alone being associated with several consequence subscales despite not being associated with more alcohol use. Drinking more frequently at home alone was associated with more abuse or dependence, social, personal, hangover, and social media consequences. These associations with multiple consequence subscale in the absence of an association with increased drinking provide further evidence drinking alone has unique mechanisms of risk compared to social drinking settings. Previous research suggests affective states and motives to drink may differ between drinking alone and drinking in social groups, such that drinking alone is associated more with negative mood and drinking to cope (Creswell, 2021; O'Hara et al., 2015). Thus, in addition to a lack of social interaction while drinking alone, the differences in mood and motives for drinking may increase risk of experiencing specific alcohol‐related consequences.

Limitations and future directions

Findings should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, generalizability may be limited given that data were drawn from one study of college students. Although the response rate (i.e., 35% of invited students) is similar to many online surveys (e.g., Moskow et al., 2022; Nulty, 2008), there may be differences between participants and the overall student population. Additionally, as COVID‐19 regulations vary by state, it is unclear to what extent these findings generalize to other locations. Data were also cross‐sectional in nature and did not include prepandemic data to examine how changes have occurred prepandemic to during the pandemic. Time‐related differences between cohorts should be interpreted with caution, as any differences may represent differences in who was more likely to select into the study at any given timepoint and the study recruitment design. Specifically, since cohorts were recruited based of predetermined birthday windows, the Fall 2020 cohort had a smaller sample due to having a smaller random selection of students with eligible birthdates from which to recruit. Relatedly, participants did not report on whether they lived on campus prior to COVID‐19 restrictions, and we cannot determine differences among students who lived on campus and then moved off versus those who never lived on campus. Longitudinal data assessing drinking contexts throughout the pandemic and assessing if students ever lived on campus prior to COVID‐19 may be helpful for further elucidation of these questions.

Relatedly, although we conceptualized drinking contexts as predictors of consumption and consequences, the temporal ordering and causal effects could not be determined in this cross‐sectional study. Drinking contexts were assessed only in terms of frequency, and quantity of alcohol consumption and occurrence of alcohol‐related consequences in each drinking context were not examined. Thus, although we considered whether frequency of drinking in various contexts was associated with heavier drinking or more consequences in the past month overall, we cannot infer from this study whether effects of drinking context are proximal (e.g., within a given night) or more distal (e.g., risk accrues over time). We also were not able to determine if a participant drank in multiple contexts within one day, or if multiple contexts occurred simultaneously, such as drinking at home with others physically and virtually present. Further, while we used a maximum score for frequency to account for the possibility of drinking in multiple within a day (to prevent overcounting), this approach may have led to undercounting frequency of drinking in the contexts examined. Event‐specific information is needed to determine how drinking within different contexts might be associated with subsequent alcohol use and consequences. Such data may be able to support development of individualized and adaptive interventions that provide relevant intervention material associated with a student's reported social plans and/or location.

Finally, the COVID‐19 pandemic is ongoing, and it remains unclear how drinking contexts will continue to shift for college students as the pandemic and more targeted drinking prevention efforts progress. Our results indicate even during the most restrictive times of the pandemic, some students chose to connect with others while drinking, both inside and outside the home. Frequency of drinking outside the home was associated with the largest range of alcohol‐related consequences, highlighting the importance of targeting this drinking context through interventions. Importantly, some students may have been motivated by prosocial factors to reduce the spread of COVID‐19 and chose to drink at home, instead of outside the home. These socially motivated individuals may be amenable to social norms‐based interventions, such as normative feedback intervention (Agostinelli et al., 1995; Neighbors et al., 2004) to reduce social harms from drinking at home. Tailoring norms‐based interventions to provide context‐specific feedback (e.g., quantity and frequency of drinking in different contexts) may be warranted, but additional monitoring of how drinking in these contexts progresses through the COVID‐19 pandemic and afterward is needed. Further, although a notable reduction in virtual drinking contexts has already been documented in the current study, for students who continue drinking in this context, interventions should be evaluated for how well they generalize to this drinking context. For example, protective behavioral strategies (Martens et al., 2004; Treloar et al., 2015) for reducing social and abuse/dependence consequences may look different in a virtual drinking context and students may find benefit in engaging with certain strategies more in specific contexts.

CONCLUSION

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, we had an opportunity to observe natural shifts in drinking contexts between cohorts of college student drinkers participating in a larger study. Although these shifts occurred during the pandemic—which includes many unique considerations such as health‐related anxiety, economic stressors, virtual learning, and navigating the long‐term medical effects of COVID‐19 in themselves or others—current findings may also have implications beyond the pandemic. Specifically, findings add to a growing body of literature establishing differential risk for alcohol use and consequences by drinking context. The current study findings have important implications for prevention and intervention, suggesting context‐related adaptations to normative feedback and protective behavioral strategies may be warranted, and continued assessment of shifts in drinking context is needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA); data collection was funded by R37AA012547 (PI: Larimer); manuscript preparation was supported by K01AA027771 (PI: Hultgren), T32AA007455 (PI: Larimer), K08AA028546 (PI: Jaffe), and F31AA027471 (PI: Canning). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA.

Hultgren, B.A. , Smith‐LeCavalier, K.N. , Canning, J.R. , Jaffe, A.E. , Kim, I.S. & Cegielski, V.I. et al. (2022) College students' virtual and in‐person drinking contexts during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 46, 2089–2102. Available from: 10.1111/acer.14947

Endnote

We chose to take the maximum instead of a mean or sum score for several reasons. First, the number of items captured within each overarching context variable is different. Thus, a sum score would be difficult to compare across contexts. Second, a sum score may also involve overcounting drinking events that are reported on multiple items (e.g., at a party that occurred at a friend's house). Third, a mean score may reflect lower drinking frequency than what occurred if some contexts assessed in the investigator‐generated questionnaire were not applicable for participants. For example, drinking every day at home with friends, but never at home with parents, would yield a mean score of 14 days per 28 days drinking at home with others; we believe the maximum score of 28 days is a more accurate way to reflect the past 28 day frequency of drinking at home with other people in this example.

REFERENCES

- Agostinelli, G. , Brown, J.M. & Miller, W.R. (1995) Effects of normative feedback on consumption among heavy drinking college students. Journal of Drug Education, 25(1), 31–40. 10.2190/XD56-D6WR-7195-EAL3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. (2014) Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, J.S. (2002) Student factors: understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. Supplement, 14, 40–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin, M.M. , Paschall, M.J. , Saltz, R.F. & Zamboanga, B.L. (2012) Young adults and casual sex: the relevance of college drinking settings. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 274–281. 10.1080/00224499.2010.548012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, Z. , Pabst, A. , Creupelandt, C. , Fontesse, S. , Laniepce, A. & Maurage, P. (2022) Longitudinal assessment of alcohol consumption throughout the first COVID‐19 lockdown: contribution of age and pre‐pandemic drinking patterns. European Addiction Research, 28(1), 48–55. 10.1159/000518218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonar, E.E. , Parks, M.J. , Gunlicks‐Stoessel, M. , Lyden, G.R. , Mehus, C.J. , Morrell, N. et al. (2021) Binge drinking before and after a COVID‐19 campus closure among first‐year college students. Addictive Behaviors, 118, 106879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, M.E. , Kristensen, K. , Van Benthem, K.J. , Magnusson, A. , Berg, C.W. , Nielsen, A. et al. (2017) glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero‐inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal, 9(2), 378–400. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. & Murphy, S. (2020) Alcohol and social connectedness for new residential university students: implications for alcohol harm reduction. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44, 216–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, B.H. , Maggs, J.L. & Loken, E. (2018) Change in college students' perceived parental permissibility of alcohol use and its relation to college drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2022) COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/covid‐data/covidview/index.html [Accessed 12th April 2022].

- Collins, R.L. , Parks, G.A. & Marlatt, G.A. (1985) Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self‐administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 189–200. 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, W.R. , Waddell, J.T. , Ladensack, A. & Scott, C. (2020) I drink alone: mechanisms of risk for alcohol problems in solitary drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 102, 106147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, K.G. (2021) Drinking together and drinking alone: a social‐contextual framework for examining risk for alcohol use disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30, 19–25. 10.1177/0963721420969406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum, J. , O'Grady, M. , Armeli, S. & Tennen, H. (2012) The role of context‐specific norms and group size in alcohol consumption and compliance drinking during natural drinking events. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34, 304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, T.M. , Ellis, W. & Litt, D.M. (2020) What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID‐19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic‐related predictors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67, 354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar, C. , Morgan, E. , Kaysen, D. , Newcomb, M.E. & Mustanski, B. (2021) Risk factors for elevations in substance use and consequences during the COVID‐19 pandemic among sexual and gender minorities assigned female at birth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 227, 109015. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels, R.C. , Wiers, R. , Lemmers, L.E.X. & Overbeek, G. (2005) Drinking motives, alcohol expectancies, self‐efficacy, and drinking patterns. Journal of Drug Education, 35(2), 147–166. 10.2190/6Q6B-3LMA-VMVA-L312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, C.B. , Mason, W.A. , Stevens, A.L. , Jaffe, A.E. , Cadigan, J.M. , Rhew, I.C. et al. (2021) Antecedents, concurrent correlates, and potential consequences of young adult solitary alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35(5), 553–564. 10.1037/adb0000697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme, K. , Corbin, W.R. & Kruse, M.I. (2008) Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, V.M. & Skewes, M.C. (2013) Solitary heavy drinking, social relationships, and negative mood regulation in college drinkers. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(4), 285–294. 10.3109/16066359.2012.714429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huckle, T. , Gruenewald, P. & Ponicki, W.R. (2016) Context‐specific drinking risks among young people. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(5), 1129–1135. 10.1111/acer.13053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt, S.C. & Sher, K.J. (1992) Assessing negative alcohol consequences in college students. Journal of American College Health, 41(2), 700–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, K.M. , Merrill, J.E. , Stevens, A.K. , Hayes, K.L. & White, H.R. (2021) Changes in alcohol use and drinking context due to the COVID‐19 pandemic: a multimethod study of college student drinkers. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 45, 752–764. 10.1111/acer.14574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, A.E. , Kumar, S.A. , Ramirez, J.J. & DiLillo, D. (2021) Is the COVID‐19 pandemic a high‐risk period for college student alcohol use? A comparison of three spring semesters. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 45, 854–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeze, E. , & Popper, N. (2020) The virus changed the way we internet. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/07/technology/coronavirus‐internet‐use.html. [Accessed 7th January 2022].

- LaBrie, J.W. , Hummer, J.F. & Pedersen, E.R. (2007) Reasons for drinking in the college student context: the differential role and risk of the social motivator. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 393–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez, C.W. , Read, J.P. , Kahler, C.W. , Richards, J.B. , Ramsey, S.E. , Stuart, G.L. et al. (2002) Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the balloon analogue risk task (BART). Journal of Experimental Psychology, 8, 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R (2022). _emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least‐squares Means_. R package version 1.7.5 . Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans

- Maggs, J.L. , Cassinat, J.R. , Kelly, B.C. , Mustillo, S.A. & Whiteman, S.D. (2021) Parents who first allowed adolescents to drink alcohol in a family context during spring 2020 COVID‐19 emergency shutdowns. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68, 816–818. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens, M.P. , Taylor, K.K. , Damann, K.M. , Page, J.C. , Mowry, E.S. & Cimini, M.D. (2004) Protective behavioral strategies when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol‐related consequences in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(4), 390–393. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens, M.P. , Neighbors, C. , Dams‐O'Connor, K. , Lee, C.M. & Larimer, M.E. (2007) The factor structure of a dichotomously scored Rutgers alcohol problem index. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 597–606. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley, J.S. , Curran, P.J. & Hedeker, D. (2015) A novel modeling framework for ordinal data defined by collapsed counts. Statistics in medicine, 34(15), 2312–2324. 10.1002/sim.6495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight‐Eily, L.R. , Okoro, C.A. , Strine, T.W. , Verlenden, J. , Hollis, N.D. , Njai, R. et al. (2021) Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic – United States, April and may 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(5), 162–166. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskow, D.M. , Lipson, S.K. & Tompson, M.C. (2022) Anxiety and suicidality in the college student population. Journal of American College Health, 31, 1–8. 10.1080/07448481.2022.2060042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MyNorthwest . (2021) Timeline: A look back at Washington state's COVID‐19 response . Available at: https://mynorthwest.com/2974047/timeline‐washington‐states‐covid‐19‐response/ [Accessed 21st November 2021].

- Neighbors, C. , Larimer, M.E. & Lewis, M.A. (2004) Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: efficacy of a computer‐delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 434–447. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors, C. , DiBello, A.M. , Young, C.M. , Steers, M.L.N. , Rinker, D.V. , Rodriguez, L.M. et al. (2019) Personalized normative feedback for heavy drinking: an application of deviance regulation theory. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 115, 73–82. 10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nulty, D.D. (2008) The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3), 301–314. 10.1080/02602930701293231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara, R.E. , Armeli, S. & Tennen, H. (2015) College students' drinking motives and social‐contextual factors: comparing associations across levels of analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 420–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padovano, H.T. , Janseen, T. , Emery, N.N. , Carpenter, R.W. & Miranda, R. (2019) Risk‐taking propensity, affect, and alcohol craving in adolescents' daily lives. Substance Use & Misuse, 54, 2218–2228. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1639753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar, J.J. & Acosta, P. (2021) Virtual raves and happy hours during COVID‐19: new drug use contexts for electronic dance music partygoers. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 93, 102904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, M.E. , Lee, C.M. & Larimer, M.E. (2011) Drinking motives, protective behavioral strategies, and experienced consequences: identifying students at risk. Addictive Behaviors, 36(3), 270–273. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.B. , Morey, J. & Higgins, D.M. (2005) You drink, I drink: alcohol consumption, social context and personality. Individual Differences Research, 3, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, M.S. , Tucker, J.S. & Green, H.D. (2020) Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2022942. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proclamation 20‐05 . (2020). State of Washington Office of the Governor . Available at: https://www.governor.wa.gov/sites/default/files/proclamations/20‐05%20Coronavirus%20%28final%29.pdf [Accessed 16th November 2021].

- R Core Team . (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at https://www.R‐project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, J.P. , Devadas, J. , Pease, M. , Nketia, B. & Fish, J.N. (2020) Sexual and gender minority stress amid the COVID‐19 pandemic: implications for LGBTQ young persons' mental health and well‐being. Public Health Reports, 135(6), 721–727. 10.1177/0033354920954511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Statistics and Quality . (2020) National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 2.29B Heavy alcohol use in past month: Among people aged 12 or older; by age group and demographic characteristics, percentages, 2019 and 2020 . Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020‐nsduh‐detailed‐tables [Accessed 18th March 2022].

- Schafer, J.L. (1999) Multiple imputation: a primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 8(1), 3–15. 10.1177/096228029900800102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrzynski, C.J. & Creswell, K.G. (2021) A systematic review and meta‐analysis on the association between solitary drinking and alcohol problems in adults. Addiction, 116, 2289–2303. 10.1111/add.15355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, S.H. , Morris, E. , Mellings, T. & Komar, J. (2006) Relations of social anxiety variables to drinking motives, drinking quantity and frequency, and alcohol‐related problems in undergraduates. Journal of Mental Health, 15, 671–682. 10.1080/09638230600998904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar, H. , Martens, M.P. & McCarthy, D.M. (2015) The protective behavioral strategies Scale‐20: improved content validity of the serious harm reduction subscale. Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 340–346. 10.1037/pas0000071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela, A. & Pritchard, M.E. (2011) Peer influence: use of alcohol, tobacco, and prescription medications. Journal of American College Health, 59, 751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, E.L. , Corbin, W.R. & Fromme, K. (2009) Academic and social motives and drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(4), 564–576. 10.1037/a0017331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, J.T. , Corbin, W.R. & Marohnic, S.D. (2021) Putting things in context: longitudinal relations between drinking contexts, drinking motives, and negative alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35, 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Department of Health . (2021) COVID‐19 transmission across Washington State (No. 820–114) . Available at: https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2022‐03/820‐114‐SituationReport‐20211020.pdf [Accessed 16th March 2020].

- Wechsler, H. & Nelson, T.F. (2008) What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College alcohol study: focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69(4), 481–490. 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, H.R. & Labouvie, E.W. (1989) Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 50(1), 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, H.R. , Stevens, A.K. , Hayes, K. & Jackson, K.M. (2020) Changes in alcohol consumption among college students due to COVID‐19: effects of campus closure and residential change. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 81, 725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.A. , Thomas, N.S. , Adkins, A.E. & Dick, D.M. (2018) Perception of peer drinking and access to alcohol mediate the effect of residence status on alcohol consumption. American Journal of Undergraduate Research, 14(4), 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020) WHO director‐General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19 . Available at: https://www.who.int/director‐general/speeches/detail/who‐director‐general‐s‐opening‐remarks‐at‐the‐media‐briefing‐on‐covid‐19‐‐‐11‐march‐2020 [Accessed 2nd February 2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Appendix S2