Abstract

Background:

The Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaire for patellar tendinopathy (VISA-P) is currently not available in the Arabic language.

Purpose:

To translate and culturally adapt the VISA-P questionnaire into Arabic and to evaluate its reliability and validity.

Study Design:

Cohort study (diagnosis); Level of evidence, 3.

Methods:

Translation of the VISA-P questionnaire was implemented in compliance with international guidelines. In total, 111 participants (53 with patellar tendinopathy and 58 healthy controls) were recruited to validate the Arabic-language version of the VISA-P (VISA-P-Ar). The patients with patellar tendinopathy completed the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and rated their knee pain using the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS). They completed the VISA-P-Ar twice (within a week) to assess test-retest reliability. Scores between the patients and controls were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test, construct validity was assessed with Spearman rank-order correlation, internal consistency was assessed with the Cronbach alpha, and test-retest reliability was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results:

There was a significant difference in VISA-P-Ar scores between the patellar tendinopathy group (mean, 41.35 ± 13.56) and the control group (mean, 95.22 ± 8.22) (P < .001). In addition, scores on the VISA-P-Ar were significantly positively correlated with the SF-36 (r = 0.630; P < .001) and significantly negatively correlated with the NPRS (r = −0.681; P < .001). The items in the VISA-P-Ar had good internal consistency (α = 0.709) and showed high test-retest reliability (ICC, 0.941; P < .001).

Conclusion:

The results of this study indicated that the VISA-P-Ar is a valid and reliable tool for assessing symptoms of patellar tendinopathy in the Saudi population and can be used in clinical and research settings.

Keywords: patellar tendinopathy, cross-cultural, jumper’s knee, validation

Patellar tendinopathy, also known as jumper’s knee, is an overuse injury of the patellar tendon that typically induces load-related focal pain at the point of attachment of the patellar tendon to the patella. 6 The prevalence of sport-related patellar tendinopathy is approximately 14% among recreational athletes and 45% among professional athletes. 13,20 The condition primarily induces pain and dysfunction in jumping athletes, which may lead to termination of participation in sports. 10,20 In repetitive jumping, cutting, and hill running activities, patellar tendinopathy seems to be an increasingly chronic problem. 5 Patellar tendinopathy is a difficult injury to manage, and about one-third of patients who visit sports medicine clinics are unable to return to sports for up to 6 months after the onset of their injury. 5 A 15-year follow-up report found that 53% of athletes with patellar tendinopathy have stopped engaging in their various sports. 10

The Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaire for patellar tendinopathy (VISA-P) is an outcome measure used to assess symptom severity. The form consists of 8 questions, with the first 6 questions designed to evaluate the severity of patellar tendinopathy symptoms during sports activities, while the last 2 questions assess the ability to participate in sporting activities. The VISA-P has been adapted to several languages. 1,5,8 –10,13,15,21,22

The primary motivation for this study was to provide medical practitioners in Saudi Arabia with a valid and reliable assessment method for patellar tendinopathy. We aimed to translate and culturally adapt the VISA-P questionnaire into Arabic and to evaluate the reliability and validity of the translated questionnaire for the Saudi population.

Methods

Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the VISA-P

In this cross-sectional study, permission for Arabic translation and adaptation was obtained from the author of the original VISA-P questionnaire, K.M. Khan, in 2020. The method of adaptation followed the international guidelines prescribed by Beaton et al 3 and comprised 6 steps: (1) forward translation, (2) synthesis, (3) backward translation, (4) expert committee review, (5) pretesting, and (6) expert committee approval.

Forward translation of the original VISA-P (from English to Arabic) was performed by 2 individuals (first forward translator [T1] and second forward translator [T2]; both were native Arabic speakers who were fluent in English). T1 is a sports physical therapist with clinical knowledge of musculoskeletal conditions, and T2 holds a degree in teaching English and has no affiliation with the medical field. The 2 translators (T1 and T2) participated in questionnaire synthesis meetings with the investigators, during which variations in their translations were addressed to create a single Arabic version by combining the translations of T1 and T2 (T12). Backward translation (from Arabic to English) of the T12 version was performed separately by 2 native English speakers (first backward translator [BT1] and second backward translator [BT2]) who were fluent in Arabic. BT1 is a math teacher, and BT2 is an English teacher.

After the completion of the forward translation, synthesis, and backward translation, a meeting of experts was held to develop the Arabic-language version of the VISA-P (VISA-P-Ar). The expert committee comprised all the authors as well as the 4 translators (T1, T2, BT1, and BT2). The purpose of the meeting was to produce a prefinal version of the questionnaire. A cognitive pretest of the prefinal version was conducted with a sample of 26 athletes who had patellar tendinopathy. The purpose of this step was to assess whether the VISA-P-Ar was understandable, whether it used expressions relevant to Saudi culture, and whether the vocabulary was appropriate. After the pretesting step, the committee of experts approved the final version of the VISA-P-Ar.

Study Participants

Sample size was determined based on recommendations for the respondent-to-item ratio of 5 to 1. 19 A total of 129 participants were originally recruited from outpatient clinics in Saudi Arabia between October 2020 and December 2020. Participant inclusion criteria included age between 18 and 64 years, Saudi native, ability to read and understand Arabic, and current patellar tendinopathy (for the patient group). Exclusion criteria included knee pain unrelated to a diagnosis of patellar tendinopathy or unconfirmed by a diagnosis.

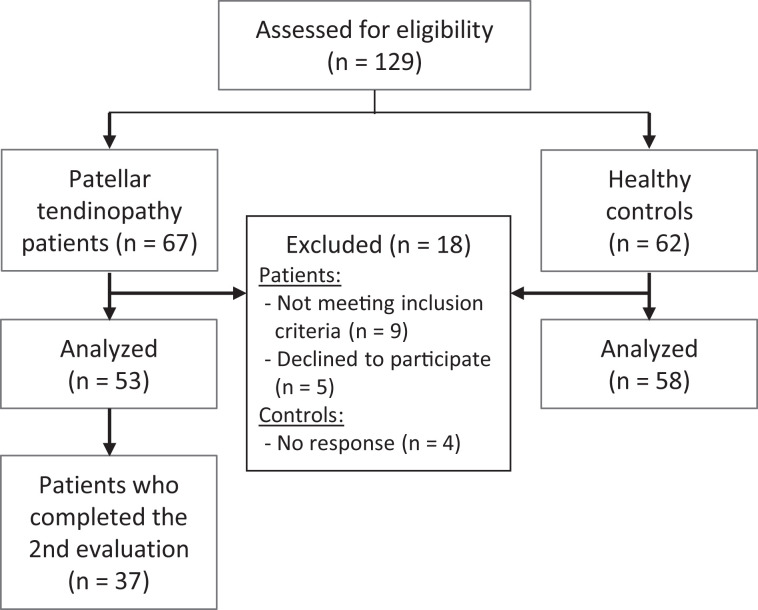

Of the initial participants, 111 participants were included in the study. They were divided into 2 categories: 53 athletes (5 female, 48 male; mean age, 28.8 ± 6.6 years) with patellar tendinopathy at the time of recruitment and 58 controls (24 female, 34 male; mean age, 30.4 ± 8.5 years). All participants eligible for recruitment were given approval by the primary investigator to participate in the study. The study objectives were explained to the participants, and all participants signed an informed consent form. A flowchart of participant recruitment is shown in Figure 1, and the characteristics of the study groups are included in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating participant enrollment.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 111) a

| Patellar Tendinopathy (n = 53) | Control (n = 58) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 28.77 ± 6.58 (18-44) | 30.44 ± 8.54 (18-57) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 48 (90.6) | 34 (58.6) |

| Female | 5 (9.4) | 24 (41.4) |

| Education | ||

| High school | 7 (13.2) | 5 (8.6) |

| Bachelor | 39 (73.6) | 48 (82.8) |

| Master | 5 (9.4) | 3 (5.2) |

| PhD | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.4) |

a Data are reported as mean ± SD (range) or n (%).

Outcome Instruments

The VISA-P contains 8 items. The first 6 items rate pain levels during daily activities on a numerical measurement scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum pain). The last 2 items capture information on sports participation. The overall score on the VISA-P questionnaire is on a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 indicates the worst patellar tendon condition and 100 corresponds to a healthy patellar tendon.

In addition to the VISA-P, the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) for pain intensity were also used. The SF-36 is a quality of life instrument commonly used to assess the impact of medical interventions and the outcomes of health care services. The SF-36 consists of 36 Likert scale questions divided into 8 scales: (1) physical functioning, (2) bodily pain, (3) social functioning, (4) general health perception, (5) role-physical, (6) role-emotional, (7) vitality, and (8) mental health. The SF-36 has been found to be a valid and reliable measure, and the Arabic version of the SF-36 was used in this study. 18 The NPRS has been found to be a valid and reliable measure of pain. 2 Participants were asked to rate their knee pain during the past week on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum pain experienced).

Participants in the patellar tendinopathy group were asked to complete the VISA-P-Ar questionnaire, SF-36, and NPRS. The healthy controls were only asked to complete the VISA-P-Ar questionnaire. In addition, approximately 1 week after their first evaluation, participants in the patellar tendinopathy group were asked to complete the VISA-P-Ar again for test-retest reliability.

Statistical Analysis

For the validity testing of the VISA-P-Ar, we compared the total scores on the VISA-P-Ar between the patellar tendinopathy group and the healthy controls using the Mann-Whitney U test. Additionally, the construct validity of the VISA-P-Ar was determined in the patellar tendinopathy group by assessing their scores on the VISA-P-Ar, SF-36 (Arabic version), and NPRS questionnaire using the Spearman rank-order correlation. The internal consistency of the VISA-P-Ar items was evaluated in the patellar tendinopathy group using the Cronbach alpha coefficient. The test-retest reliability of the VISA-P-Ar was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in patients in the patellar tendinopathy group who completed the second VISA-P-Ar assessment within 1 week of the first assessment. ICC values were interpreted as poor (<0.5), moderate (0.50 to <0.75), good (0.75 to 0.90), and excellent (>0.90). 17

Results

VISA-P-Ar Scores

There was a statistically significant difference in the VISA-P-Ar scores of the patient group (n = 53) and the healthy group (n = 58). The independent samples revealed that the patients with patellar tendinopathy had worse VISA-P-Ar scores (mean, 41.35 ± 13.56) compared with the healthy controls (mean, 95.22 ± 8.22) (P < .001, Mann-Whitney U test).

Construct Validity

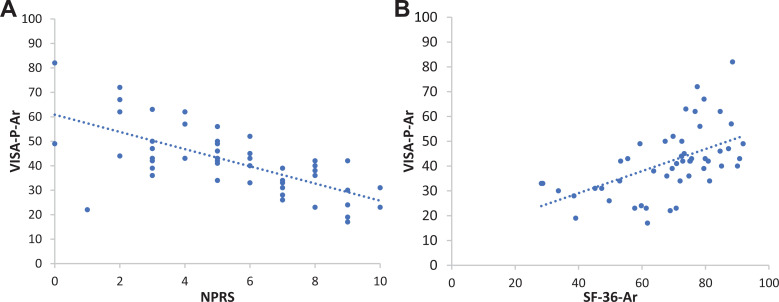

The results of the Spearman rho test showed that scores on the VISA-P-Ar were significantly positively correlated with scores on the SF-36 (r = 0.630; P < .001) (Figure 2A) and that scores on the VISA-P-Ar were significantly negatively correlated with scores on the NPRS (r = −0.681; P < .001) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Results of Spearman correlation analysis between the (A) Arabic-language version of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaire for patellar tendinopathy (VISA-P-Ar) and numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) and (B) VISA-P-Ar and 36-item Short Form Health Survey (Arabic version) (SF-36-Ar).

Internal Consistency and Test-Retest Reliability

The internal consistency of the VISA-P-Ar questionnaire was assessed using data from the patellar tendinopathy group (n = 53). The Cronbach α was 0.709, indicating good reliability.

A test-retest time frame ranging from 1 to 7 days was allowed for participants in the patellar tendinopathy group. Because of restrictions imposed in response to the coronavirus 2019 pandemic, only 37 participants completed the second VISA-P-Ar assessment. For these 37 patients, the VISA-P-Ar scores (mean ± SD) were 40.48 ± 2.35 for the first administration and 41.78 ± 14.21 for the second administration, with no statistically significant difference between scores (P > .05, paired-samples t test).

The ICC of the VISA-P-Ar indicated a high test-retest reliability (ICC, 0.941; P < .001). Statistical analysis performed using the Spearman rho test showed that there was a significant correlation (r = 0.924; P < .01) between the first administration of the VISA-P-Ar questionnaire and its second administration. Thus, there was a strong correlation, and the VISA-P-Ar had a strong test-retest reliability.

Discussion

This study was performed to translate, culturally adapt, and validate the VISA-P questionnaire. For this purpose, the VISA-P was translated into the Arabic language and evaluated using a sample of 111 participants divided into 2 groups: individuals with patellar tendinopathy and healthy participants. The VISA-P questionnaire has already been translated into many major languages, with each version showing good reliability. The main findings of this study were as follows: (1) The VISA-P-Ar had good internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.709). (2) The VISA-P-Ar had high reliability (ICC, 0.941; P < .001). (3) The VISA-P-Ar correlated with the SF-36 (r = 0.630; P < .001) and NPRS (r = −0.681; P < .001). (4) The VISA-P-Ar scores were significantly different between individuals with patellar tendinopathy and healthy participants (P < .001).

Consistent with our findings, several studies have reported good to excellent internal consistency in the different versions of the VISA-P questionnaire. 1,7 –9,12 These studies reporting similar results were conducted by different investigators. The VISA-P has also been found to have good reliability in previous studies. 4,8,21,22 In this study, the ICC values for reliability were excellent, which was similar to the findings with other versions of the VISA-P. 4,16,21 The test-retest reliability showed a significant correlation between the first administration of the VISA-P-Ar and the second administration. A similar study reported no significant difference between the first and second sets of scores on the VISA-P. 22

Spearman rho testing revealed that the VISA-P-Ar had a statistically significantly positive correlation with the SF-36 and a statistically significantly negative correlation with the NPRS. The data used in this study were first analyzed for normality of the outcomes. Based on the results of the Mann-Whitney U test, it was found that the data were not normally distributed. The results indicated that the VISA-P-Ar scores of the patellar tendinopathy group were significantly different from those of the healthy controls. Previous studies have also shown that patients with patellar tendinopathy and healthy participants had significantly different scores on the VISA-P. 16,22 The VISA-P-Ar score among our sample of patients with patellar tendinopathy (41.35 ± 13.56) was worse than the VISA-P scores from previous studies (54.80-67.60), which is an indication that participants in our study were more symptomatic. 4,8,14,16

The VISA-P-Ar had good validity, and thus it captured the difference between the scores of healthy individuals and those with patellar tendinopathy. The VISA-P scale should not be regarded as a diagnostic tool—as the VISA-P researchers stated in the original publication and other publications—because there is no significant difference between the scores of athletes with patellar tendinopathy and individuals with other knee injuries. 7,11,14,15,22

Limitations

The primary limitation of the current study is the limited generalizability to native Saudi Arab speakers. In addition, our sample consisted mainly of male participants, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Future research should include various dialects of the Arabic language. Furthermore, other characteristics such as the responsiveness of VISA-P-Ar should be explored to increase its clinical applicability.

Conclusion

We consider the VISA-P-Ar questionnaire to be a valid and reliable tool for assessing patellar tendinopathy in the Saudi population and among Arabic speakers in general. The importance of the VISA-P-Ar is that it is the first Arabic-language instrument designed to measure the severity of patellar tendinopathy. Future studies should include a wider range of participants to improve the generalizability of the results and to evaluate the responsiveness of the VISA-P-Ar.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Majmaah University for supporting this work (project No. R-2022-248).

Footnotes

Final revision submitted May 11, 2022; accepted August 10, 2022.

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia (reference No. 20-194E).

References

- 1. Acharya GU, Kumar A, Rajasekar S, Samuel AJ. Reliability and validity of Kannada version of Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment for patellar tendinopathy (VISA-PK) questionnaire. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10:S189–S192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alghadir AH, Anwer S, Iqbal ZA. The psychometric properties of an Arabic numeric pain rating scale for measuring osteoarthritis knee pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(24):2392–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Çelebi MM, Köse SK, Akkaya Z, Zergeroglu AM. Cross-cultural adaptation of VISA-P score for patellar tendinopathy in Turkish population. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cook JL, Khan KM, Harcourt PR, Grant M, Young DA, Bonar SF. A. cross sectional study of 100 athletes with jumper’s knee managed conservatively and surgically. The Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31(4):332–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferretti A, Puddu G, Mariani PP, Neri M. Jumper’s knee: an epidemiological study of volleyball players. Phys Sportsmed. 1984;12(10):97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frohm A, Saartok T, Edman G, Renström P. Psychometric properties of a Swedish translation of the VISA-P outcome score for patellar tendinopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hernandez-Sanchez S, Hidalgo MD, Gomez A. Cross-cultural adaptation of VISA-P score for patellar tendinopathy in Spanish population. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2011;41(8):581–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaux JF, Delvaux F, Oppong-Kyei J, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the VISA-P questionnaire in French. Eur J Sport Med. 2015;3(suppl 1):112. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kettunen JA, Kvist M, Alanen E, Kujala UM. Long-term prognosis for jumper’s knee in male athletes: prospective follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(5):689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khan KM, Maffulli N, Coleman BD, Cook JL, Taunton JE. Patellar tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32(4):346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korakakis V, Patsiaouras A, Malliaropoulos N. Cross-cultural adaptation of the VISA-P questionnaire for Greek-speaking patients with patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(22):1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lian ØB, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Prevalence of jumper’s knee among elite athletes from different sports: a cross-sectional study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(4):561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lohrer H, Nauck T. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the VISA-P questionnaire for German-speaking patients with patellar tendinopathy. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2011;41(3):180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maffulli N, Longo UG, Testa V, Oliva F, Capasso G, Denaro V. VISA-P score for patellar tendinopathy in males: adaptation to Italian. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(20-22):1621–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park BH, Seo JH, Ko MH, Park SH. Reliability and validity of the Korean version VISA-P questionnaire for patellar tendinopathy in adolescent elite volleyball athletes. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37(5):698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. Vol 892. Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sheikh KA, Yagoub U, Elsatouhy M, Al Sanosi R, Mohamud SA. Reliability and validity of the Arabic version of the SF-36 health survey questionnaire in population of Khat chewers—Jazan Region-Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Appl Res Qual Life. 2015;10(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsang S, Royse CF, Terkawi AS. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11(suppl 1):S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Ark M, Zwerver J, van den Akker-Scheek I. Injection treatments for patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(13):1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wageck BB, de Noronha MA, Lopes AD, da Cunha RA, Takahashi RH, Pena Costa LO. Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Patella (VISA-P) scale. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2013;43(3):163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zwerver J, Kramer T, van den Akker-Scheek I. Validity and reliability of the Dutch translation of the VISA-P questionnaire for patellar tendinopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]