Abstract

Background:

Myocardial injury as indicated by elevation of cardiac troponin levels is common after acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and linked to poor outcomes. Previous studies rarely reported on serial hs-cTn measurements to distinguish whether myocardial injury is acute or chronic. Thus, little is known about frequency, associated variables, and outcome of acute myocardial injury in AIS.

Methods and patients:

In this single-centered observational cohort study, from 01/2019 to 12/2020, consecutive patients with neuroimaging-confirmed AIS <48 h after symptom onset, and serial troponin measurements within the first 2 days after admission (Roche Elecsys®, hs-cardiac troponin T) were prospectively registered. Acute myocardial injury was defined according to the fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (troponin above the upper reference limit and rise/fall>20%). Outcomes of interest were in-hospital mortality and unfavorable functional status at discharge (modified Rankin Scale >1).

Results:

Out of 1067 analyzed patients, 25.3% had acute myocardial injury, 40.4% had chronic myocardial injury and 34.3% had no myocardial injury. Older age, higher stroke severity, thrombolytic treatment, and impaired kidney function were independently associated with acute myocardial injury. In-hospital mortality was higher in patients with acute myocardial injury than in those without (13% vs 3%, adjusted OR, 2.9% [95% CI, 1.6–5.5]). Compared with no myocardial injury, both acute and chronic myocardial injury were associated with unfavorable functional status at discharge (adjusted OR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.1–2.5] and OR, 1.7 [95% CI, 1.2–2.4], respectively).

Conclusions:

A quarter of patients with AIS have evidence of acute myocardial injury according to the fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. The strong association with in-hospital mortality highlights the need for clinical awareness and future studies on underlying mechanisms.

Keywords: Ischemic stroke, cardiac biomarkers, Troponin, hs-cTnT, Stroke-Heart Syndrome, central autonomic network

Background

The current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guideline for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) recommends measuring cardiac troponin values in the early phase after the event to evaluate the cardiac status of the patient. 1 Cardiac troponin is a heart-specific biomarker to sensitively detect and quantify myocardial injury. It has been shown in various cohort studies that approximately 30%–60% of patients with AIS have evidence of myocardial injury during the first few days when high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays are applied.2–4 It is also well-established that myocardial injury in ischemic stroke is associated with poor functional outcome and increased short-term and long-term mortality.2–6

In 2018, the fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (4th UDMI) introduced for the first time the concept of “acute myocardial injury” defined as the presence of an elevated cardiac troponin value above the assay-specific 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL) together with a rise or fall (>20%) in serial measurements. 7 The 4th UDMI does not specify a strict time window which is required to define acute myocardial injury. 7 However, in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome the applied interval usually ranges from 1 to 6 h in emergency settings.7,8 Although acute myocardial injury is an essential component of myocardial infarction diagnosis, it may be caused by various ischemic and non-ischemic mechanisms.7,9,10 Until now, this concept has not been applied to ischemic stroke cohorts. Previous studies analyzed the role of elevated hs-cTn in AIS in general but did not differentiate between acute or chronic myocardial injury according to the 4th UDMI. To evaluate the necessity of further immediate diagnostic tests, it is important though to assess the dynamic of myocardial injury by applying serial measurements of hs-cTn.7,9,10 Furthermore, knowledge on short-term outcome of AIS patients with acute myocardial injury as compared with patients with normal hs-cTn values or chronic myocardial injury is limited.

Therefore, the aim of this analysis was to determine the frequency, associated variables, and short-term outcomes of acute myocardial injury according to the 4th UDMI in patients with AIS.

Methods

Study population

All consecutive patients admitted to our tertiary care hospital for ischemic stroke were prospectively screened for participation in the ongoing observational study “cardiomyocyte injury following acute ischemic stroke” (CORONA-IS; Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03892226). CORONA-IS aims at gaining mechanistic insights into stroke-associated myocardial injury by using a broad diagnostic approach including cardiovascular MRI, transthoracic echocardiography, autonomic ECG-markers and extensive biobanking. 11 In November 2018, the Ethics Committee/Internal Review Board of the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin approved the study (EA4/123/18). Screening started in January 2019.

Inclusion criteria for registration in the prospective screening data base are neuroimaging-confirmed diagnosis of AIS (i.e. acute lesion in the diffusion weighted imaging sequence in cerebral MRI or acute lesion in cranial CT) and admission to the hospital within 48 h after symptom onset.

Furthermore, patients required a serial measurement of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) within the first 2 days after admission (assay characteristics: hs-troponin-T, Roche Elecsys®, Gen 5; 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL) = 14 ng/L; 10% coefficients of variation (CV) precision = 13 ng/l; limit of detection = 5 ng/L).

According to the fourth UDMI, patients were divided into three groups.7,11,12

no myocardial injury (both values ⩽URL),

chronic myocardial injury (at least one value >URL, but no rise/fall >20%) and

acute myocardial injury (at least one value >URL and rise/fall >20%).

In case the first value is <URL, the second one needs to show an increase of >50% of the URL (i.e. 7 ng/L with our deployed assay), to classify as acute myocardial injury. 12

Data collection and outcomes

Patients’ demographics, previous medical history, information regarding stroke onset and severity, in-hospital treatment and diagnostics, as well as length of hospital stay were collected from clinical records according to previously published standards. 13 Impaired kidney function was defined as known medical history or serum creatinine above the normal cut-off (1.2 mg/dL in males and 0.9 mg/dL in females). Pre-stroke functional dependency was defined as living in a nursing home or requiring nursing care at home. Stroke severity and functional status were assessed via National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and modified Rankin Scale (mRS).

Outcomes of interest were (1) in-hospital mortality and (2) functional status at hospital discharge. An unfavorable neurological functional status at hospital discharge was defined as mRS-value >1, meaning at least slight disability (i.e. independent, but can’t do work/leisure/school activities fulltime). 14

In sensitivity analyses, (I) all deceased patients with early withdrawal of care ⩽72 h after hospital admission were excluded to correct for potential withdrawal of care bias and (II) the cut-point for unfavorable functional status at discharge was set at mRS > 2 (instead of the more restrictive mRS > 1 used in the main analysis) to account for heterogeneity of cut-offs applied in the literature.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were reported as absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) in case of normally distributed variables and as median with interquartile range [IQR] in case of variables with skewed distribution. Group characteristics were compared using χ2 test for categorical variables. Group comparisons of continuous data were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for skewed and normally distributed variables, respectively. In case of comparison of two groups, paired t-test was used for normally distributed data and Mann-Whitney-U-test for non-normally distributed data.

First, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify variables independently associated with the presence of acute myocardial injury (reference were all patients without acute myocardial injury). Possible multicollinearity was defined as VIF ⩾2.5. 15 Second, unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios [OR] with corresponding 95% confidence interval were calculated regarding the association of acute myocardial injury with the respective outcomes. The adjusted model included all variables associated with the respective outcomes in univariable comparison with p < 0.1. Regarding in-hospital mortality, adjustments were made for age, sex, NIHSS at admission, impaired kidney function, history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and pre-stroke functional dependency. Regarding unfavorable functional status, the model additionally included previous stroke and history of diabetes. To evaluate the impact of chronic versus acute myocardial injury on the respective outcomes, we repeated the analyses entering myocardial injury as categorical variable with no myocardial injury as reference.

All tests were two-sided and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. No corrections were made for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, version 27.0) and RStudio (RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, version 1.2.5019).

Results

Patient characteristics

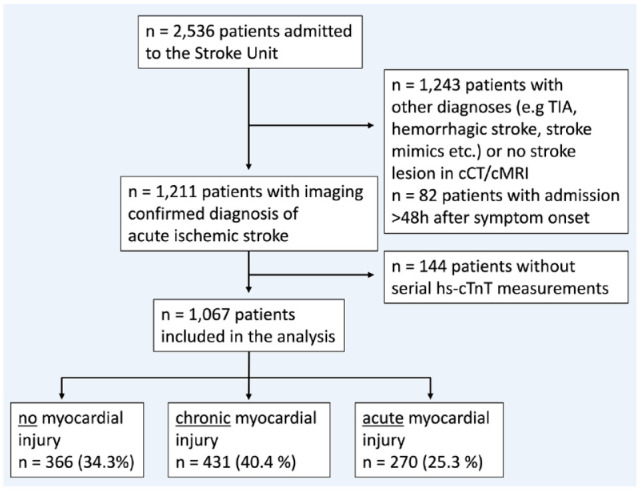

From Jan 1st, 2019, until Dec 31st, 2020, 2536 patients were admitted to our stroke unit with suspected ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, TIA or other acute neurological diseases that required continuous monitoring, for example, status epilepticus. Out of these, 1243 patients had other final diagnoses than AIS or the diagnosis of AIS was not confirmed through neuroimaging. One hundred forty-four patients had no serial cTnT-measurements and n = 82 patients an hospital admission >48 h after symptom onset, leading to n = 1067 patients included in the further analysis in total (see Figure 1). Patients without serial hs-cTnT measurements (n = 144) were younger (mean age 71 vs 75 years), had lower rates of intravenous thrombolysis and higher rates of thrombectomy, but did not differ regarding sex, rates of cardiovascular risk factors, baseline hs-cTnT values, NIHSS, or outcomes of interest (all p > 0.05, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the included patients in the analysis; TIA transient ischemic attack, cMRI cranial magnetic resonance imaging, hs-cTnT high sensitivity Troponin-T.

In the analyzed study cohort (n = 1067), mean age was 75.2 years (SD, ±11.6), 573 (53.7%) were male, and median baseline NIHSS was 3 (IQR, 1–7). Median time from symptom onset to first and second hs-cTnT measurement was 8 h (IQR, 3–19 h) and 25 h (IQR, 18–37 h), respectively. Median time interval between serial hs-cTnT measurements was 16 h (IQR, 7–21 h). In total, 33 patients underwent coronary angiography before discharge, and 16 patients had a cardiologist-confirmed diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Of these 16 patients, 13 had acute myocardial injury and three had chronic myocardial injury in serial hs-cTnT measurements.

Frequency of acute myocardial injury

In total, a hs-cTnT level above URL was determined in 56.3% at the first and in 64.2% at the second measurement time-point. Out of the 1067 patients, 366 (34.3%) showed normal hs-cTnT levels in both measurements and were therefore classified as no myocardial injury, 431 patients (40.4%) had chronic myocardial injury, and 270 (25.3%) patients had acute myocardial injury.

Variables associated with acute myocardial injury

Table 1 displays baseline characteristics of patients with and without acute myocardial injury. In multivariable regression analysis, older age (OR, 1.04 per year [95% CI, 1.02–1.06]), higher baseline stroke severity (OR, 1.09 per point on NIHSS [95% CI, 1.06–1.11]), intravenous thrombolysis (OR, 1.49 [95% CI, 1.08–2.08]), and impaired kidney function (OR, 1.49 [95% CI, 1.04–2.13]) showed independent associations with acute myocardial injury (see Supplemental Table I).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes according to presence of acute myocardial injury.

| Entire cohort | No acute myocardial injury | Acute myocardial injury | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1067 | n = 797 (74.7%) | n = 270 (25.3) | ||

| Age (years), mean ±SD | 75.2 (±11.7) | 73.8 (±12.0) | 79.3 (±9.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 494 (46.3) | 353 (44.4) | 141 (52.2) | 0.024 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 808 (75.7) | 589 (73.9) | 219 (81.1) | 0.017 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 304 (28.5) | 207 (26.0) | 97 (35.9) | 0.002 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 193 (18.1) | 132 (16.6) | 61 (22.6) | 0.026 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 356 (33.4) | 263 (33.0) | 93 (34.4) | 0.663 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 526 (49.3) | 394 (49.4) | 132 (48.9) | 0.877 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 252 (23.6) | 183 (23.0) | 69 (25.6) | 0.386 |

| Impaired kidney function, n (%) | 213 (20.0) | 138 (17.3) | 75 (27.8) | <0.001 |

| Pre-stroke functional dependency, n (%)* a | 196 (18.4) | 127 (16.0) | 69 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| First available hs-cTnT [ng/L], median [IQR] | 16 [10–29] | 13 [8–24] | 24 [17–52] | <0.001 |

| Second available hs-cTnT [ng/L], median [IQR] | 19 [11–36] | 15 [9–24] | 39 [25–80] | <0.001 |

| i.v. thrombolysis, n (%) | 287 (26.9) | 194 (24.3) | 93 (34.4) | 0.001 |

| NIHSS at admission, median [IQR]* b | 3 [1–7] | 3 [1–6] | 6 [2–14] | <0.001 |

| Suspected AIS etiology, n (%) | ||||

| Cardioembolic | 366 (34.3) | 259 (32.5) | 107 (39.6) | 0.033 |

| Small vessel disease | 109 (10.2) | 91 (11.4) | 18 (6.7) | 0.026 |

| Non-cardioembolic or undetermined | 592 (55.5) | 447 (56.1) | 145 (53.7) | 0.496 |

| Outcome | ||||

| mRS at discharge, median [IQR] | 2 [1–4] | 2 [1–4] | 4 [1–5] | <0.001 |

| Unfavorable functional status at discharge (mRS > 1), n (%) | 618 (57.9) | 421 (52.8) | 197 (73.0) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 56 (5.2) | 22 (2.8) | 34 (12.6) | <0.001 |

IQR: interquartile range; hs-cTnT: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS: modified Rankin Scale.

Data available in an = 1065 and bn = 1055 patients.

Supplemental Table II shows baseline characteristics of patients according to the presence of acute, chronic, and no myocardial injury separately. In brief, patients with chronic myocardial injury had similar age distribution and a slightly higher burden of comorbidities compared with patients with acute myocardial injury, while stroke severity and sex distribution resembled those observed in patients with normal hs-cTnT values.

In-hospital mortality and functional status at discharge

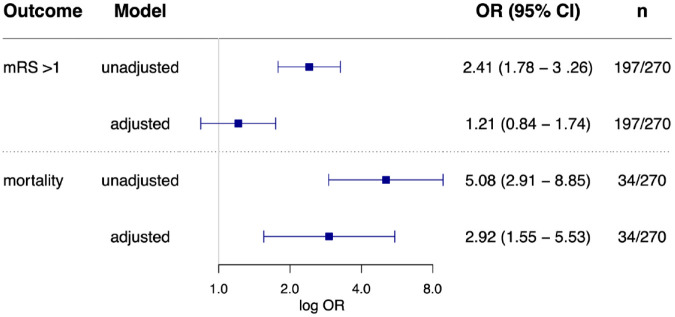

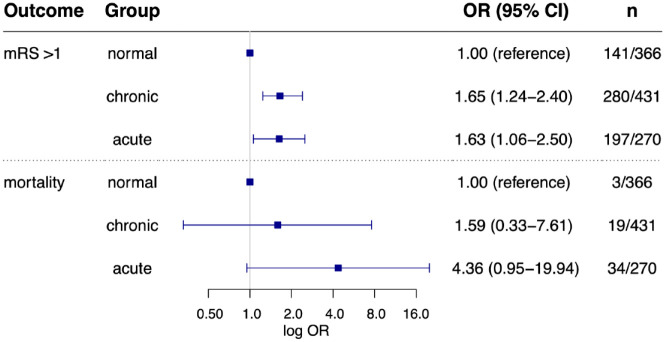

A total of 618 (57.9%) patients scored mRS > 1 at discharge and 56 patients (5.2%) died during a median length of hospital stay of 4 days (IQR 3–7 days). Cause of death was considered neurological in 35 patients (e.g. space-occupying brain edema or secondary intracerebral hemorrhage) and non-neurological in 21 patients including eight cardiac and 13 other medical conditions (e.g. sepsis, severe kidney failure, end-stage malignancy). In 14 patients death occurred following an early withdrawal of care. In-hospital mortality differed between the groups ranging from 3/366 (0.8%) in patients without myocardial injury to 19/431 (4.4%) in chronic myocardial injury, and 34/270 (12.6%) in patients with acute myocardial injury. Presence of acute myocardial injury was associated with in-hospital mortality in univariate comparison (13% vs 3%, OR, 5.08 [95% CI, 2.91–8.85], p < 0.001) as well as after full adjustment (OR, 2.92 [95% CI, 1.55–5.53], p = 0.001, Figure 2). In the categorical comparison, chronic myocardial injury was not independently associated with mortality (OR, 1.59 [95% CI, 0.33–7.61], p = 0.56), while there was a trend toward a more than fourfold higher in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial injury (OR, 4.36 [95% CI, 0.95–19.94], p = 0.058] Figure 3). Results remained robust after exclusion of patients with early withdrawal of care (see Supplemental Table III).

Figure 2.

Association of acute myocardial injury with unfavorable functional status at discharge and inhospital mortality. Regarding in-hospital mortality adjustments were made for age, NIHSS, sex, history of coronary artery disease, impaired kidney function, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and pre-stroke dependency. Regarding unfavorable status at discharge, additional adjustments were made for diabetes and history of stroke.

Figure 3.

Association of acute and chronic myocardial injury with unfavorable functional status and inhospital mortality compared to patients with normal troponin values Log. scaled odds ratios (with 95% confidence interval) for in-hospital mortality and unfavorable status at discharge (mRS > 1) after full adjustments. Presence of acute or chronic myocardial injury was entered as a categorical variable with no myocardial injury (“normal”) as reference. n = prevalence of the respective outcome in the three groups (acute, chronic, or normal).

In univariate comparison, patients with acute myocardial injury were more likely to have an unfavorable functional status at discharge (73% vs 53%, OR, 2.41 [95% CI, 1.78–3.26], p < 0.001) than patients without acute myocardial injury. After multiple adjustment acute myocardial injury was not associated with unfavorable functional status when compared to patients without acute myocardial injury (OR, 1.21 [95% CI, 0.84–1.74], p = 0.317, Figure 2). When entered as a categorical variable with no myocardial injury as reference, both acute and chronic myocardial injury were independently associated with unfavorable status at discharge (adjusted OR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.06–2.50], p = 0.026 and OR, 1.65 [95% CI, 1.24–2.40], p = 0.008, respectively; Figure 3).

When applying a dichotomized cut-off of mRS > 2 in the sensitivity analysis, the presence of acute myocardial injury remained associated with unfavorable functional status at discharge in univariate analysis and after multiple adjustment (see Supplemental Tables III and IV).

Discussion

Our prospective observational study provides four major findings. First, a quarter of patients with AIS had acute myocardial injury according to the 4th UDMI. Second, acute myocardial injury was independently associated with higher age, impaired kidney function, intravenous thrombolysis, and higher stroke severity. Third, ischemic stroke patients with acute myocardial injury had a two- to threefold increased risk of in-hospital mortality compared to those without. Fourth, both acute and chronic myocardial injury were associated with unfavorable functional status at discharge (mRS > 1). Our findings could be helpful to identify a high-risk subgroup of stroke patients who should be monitored carefully and may require further cardiac diagnostics. These findings may also have implications for designing future interventional studies that aim to reduce the burden of acute cardiac complications and mortality after stroke.

A high frequency of elevated cardiac troponin values in the early phase of AIS is well-established.2,10,16 This large hospital-based cohort confirms that more than half of the patients with imaging confirmed AIS have evidence of myocardial injury (i.e. hs-cTnT > URL) early after the event. Until now, only few studies applied serial measurements to evaluate hs-cTnT dynamics,2,17,18 and so far, no study has applied the current definition of acute myocardial injury as specified in the 4th UDMI in stroke patients. Compared with previous findings of our study group, we detected a higher rate of dynamic hs-cTnT levels in this analysis (1/4 vs 1/7-8). 2 This difference might be explained by the variance in applied cut-offs and definitions (difference of >50% instead of >20% as applied in this analysis), since the concept of acute myocardial injury was not yet defined at that time. In a smaller study, Faiz et al. 18 also used a 20% change cut-off and reported a rate of 81/264 (30.7%) dynamic elevation in stroke patients with a median measurement-interval of 16 h. Anders et al. detected a dynamic pattern (defined as >30% rise/fall) in 40% of patients (55/138) with elevated troponin I values that underwent serial measurement after 3 h. These even slightly higher rates of acute myocardial injury could be attributed to the use of meanwhile outdated definitions of “dynamic” troponin pattern, less specific assays, and differences between study cohorts.

We observed an independent association for higher age, impaired kidney function, baseline NIHSS, and i.v. thrombolysis with the occurrence of post-stroke acute myocardial injury. It is well-established that older age is a non-modifiable risk factor of troponin elevation and cardiac complications after stroke.5,10,19 In addition, the association of acute myocardial injury with impaired kidney function is well in line with previous studies in stroke and other cardiac patient populations.2,7,20 Interestingly, there is evidence that elevated hs-cTnT values in patients with impaired kidney function are not primarily caused by reduced renal clearance but rather due to other uremia-associated factors damaging the myocardium. 21 Importantly, impaired kidney function alone does not explain the presence of a rise or fall pattern of troponin but may represent a risk factor leading to a higher susceptibility for developing acute myocardial injury during physically stressful events such as AIS. The finding that higher stroke severity is associated with acute myocardial injury is well in line with previous studies and highlights the notion that stroke-related factors such as lesion size contribute to the occurrence of cardiac injury.2,4,18 Given the median NIHSS of three in this cohort, rates of acute myocardial injury might be even higher in more severely affected AIS populations (e.g. in intensive care units). Higher stroke severity and stroke lesions involving the central autonomic network may promote the occurrence of a broad spectrum of cardiac complications far beyond myocardial injury and has been summarized under the term Stroke-Heart Syndrome.5,22,23 Interestingly, treatment with thrombolysis was also associated with acute myocardial injury. It has been shown in myocardial infarction that later sampling after symptom onset reduces the probability of detecting changes in hs-cTn levels due to a plateau phase. 7 Given that stroke-induced myocardial injury is believed to be mediated by time-dependent sympathetic overdrive,5,22 one may assume that this facilitates the detection of minor acute myocardial injury patterns that are observable in early presenters that are candidates for thrombolysis.

In our study, rates of unfavorable functional status at discharge and in-hospital mortality differed significantly according to hs-cTnT status. Acute myocardial injury was strongly associated with in-hospital mortality. Although several studies found an association between increased mortality and elevated hs-cTn levels in general, knowledge on the association of acute myocardial injury is limited. In one previous study, patients with a dynamic rise/fall pattern (>50% change) had a statistically significant higher risk of in-hospital mortality than patients with stable hs-cTnT. 2 Our findings indicate that this association is also present when acute myocardial injury is defined according to the 4th UDMI. Of note, when analyzing hs-cTnT status as categorical variable (no/chronic/acute myocardial injury), there was no strong association between chronic myocardial injury and in-hospital mortality which highlights the importance to apply serial measurements.

We observed an association between acute myocardial injury and unfavorable functional status at discharge even when using more restrictive (i.e. mRS > 1) and less restrictive (i.e. mRS > 2) definitions. So far, data exists regarding an independent association of elevated baseline troponin levels in general and worse functional neurological outcome after AIS.2–4 Our study adds that patients with presence of myocardial injury irrespective of its pattern are at increased risk of unfavorable short-term outcome.

Given the high short-term mortality observed in our study, evidence of acute myocardial injury should prompt careful clinical evaluation, prolonged cardiac monitoring, and further diagnostic tests in order to establish the most likely cause. Until now, there are no established practice guidelines how to deal with acute post-stroke myocardial injury, but some preliminary algorithms exist.10,22 Even though mortality and rate of unfavorable functional status were higher in patients with acute myocardial injury, chronic myocardial injury should also be taken seriously. There is evidence that AIS patients with elevated hs-cTnT are at higher risk of cardioembolic stroke etiology, cognitive impairment, and future vascular events.6,24,25 Thus, further diagnostics such as echocardiography or prolonged Holter monitoring, at least in the outpatient setting should be considered in patients with chronic myocardial injury. 10

Limitations

Some considerations must be made when interpreting the results of this analysis. First, there was a variation of the interval between the serial troponin measurements. In patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome the optimal measurement interval is a topic of ongoing discussion. The recommendations of duration between the measurements range mostly from 1 to 6 h. 7 In neurologic patients, so far there are no validated recommendations. However, it is known, that the peak troponin values usually are detected approximately 2 days after stroke onset and have a slower dynamic pattern than in patients with acute coronary syndrome. 16 Furthermore, cardiac complications seem to occur most frequently within the early phase with a peak at the third day after the event.5,19,22 Therefore, to cover the vulnerable early phase, we defined a cut-off for admission within 48 h after onset as inclusion criterion. Second, this analysis of observational data provides new information regarding the prevalence and short-term outcome of acute myocardial injury in AIS, but the exact etiology of elevated hs-cTnT in these patients cannot be differentiated in this study, in part because further cardiac diagnostics such as ECG or echocardiography data were not systematically analyzed. Moreover, patients’ history concerning other cardiac pathologies (besides coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation), such as heart failure or cardiomyopathies were not systematically collected in this screening database but are known to be associated with elevated troponin values.8,9 The further interpretation of possible underlying mechanisms will be the subjects of future studies.

We did not systematically collect data regarding stroke lesion site or pattern including vascular territory. It has been shown that anterior circulation lesions, especially in the insular cortex, which is involved in autonomic cardiac regulation, are associated with dynamic troponin elevation after stroke.2,23,26 Since we aimed to study patients with neuroimaging-confirmed stroke, it is possible that some patients with contraindications to undergo MRI or those with small ischemic lesions not visible in CT were excluded from the analysis. Finally, long-term outcomes beyond the in-hospital phase were not available. This will be assessed in the ongoing CORONA-IS study. 11

Conclusions

Our findings provide an estimate of the burden and outcome of acute myocardial injury after AIS. According to the 4th UDMI, acute myocardial injury is present in a relevant proportion of patients with AIS and associated with a two- to threefold increase of in-hospital mortality. These findings support recommendations that serial hs-cTn measurements should be applied for timely identification of ongoing myocardial involvement after stroke. Our results may inform the design of future studies investigating the burden of post-stroke cardiac complications and the underlying pathways leading to acute myocardial injury after AIS.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873221120159 for Frequency, associated variables, and outcomes of acute myocardial injury according to the fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction in patients with acute ischemic stroke by Helena Stengl, Ramanan Ganeshan, Simon Hellwig, Markus G Klammer, Regina von Rennenberg, Sophie Böhme, Heinrich J Audebert, Christian H Nolte, Matthias Endres and Jan F Scheitz in European Stroke Journal

Acknowledgments

Dr. Helena Stengl is participant in the BIH-Charité Junior Clinician Scientist Program and Prof. Dr. Scheitz is participant in the BIH-Charité Advanced Clinician Scientist Program, both funded by the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). Prof. Christian Nolte is Clinical Fellow of the BIH.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: ME reports grants from Bayer and fees paid to the Charité from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, Covidien, Novartis, and Pfizer. CHN received speaker and/or consultation fees from Abbott, Alexion, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer. HJA reports grants from Pfizer and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Novo-Nordisk, and Pfizer. JFS reports speaker fees from AstraZeneca. All listed grants and fees are outside the submitted work. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: The prospective screening of admitted patients regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria took place as part of the ongoing CORONA-IS study. For retrospective, anonymized analysis of medical data obtained during clinical routine, informed consent is not required in accordance with the laws and regulations of the Federal State of Berlin (§25 Landeskrankenhausgesetz).

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA4/123/18).

Guarantor: JS.

Contributorship: JS, RG, and HS conceived the study. JS, HS, and RG were involved in protocol development, gaining ethical approval. HS, RG, SH, MK, CHN, SB, and RR were involved in patient recruitment and data analysis. HS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Trial registration: CORONA-IS study; clinicaltrials.gov:NCT03892226

ORCID iDs: Helena Stengl  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9270-7665

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9270-7665

Christian H Nolte  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5577-1775

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5577-1775

Jan F Scheitz  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5835-4627

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5835-4627

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021; 52: e364–e467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scheitz JF, Mochmann HC, Erdur H, et al. Prognostic relevance of cardiac troponin T levels and their dynamic changes measured with a high-sensitivity assay in acute ischaemic stroke: analyses from the TRELAS cohort. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177: 886–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wrigley P, Khoury J, Eckerle B, et al. Prevalence of positive troponin and echocardiogram findings and association with mortality in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2017; 48: 1226–1232–Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahn SH, Lee JS, Kim YH, et al. Prognostic significance of troponin elevation for long-term mortality after ischemic stroke. J Stroke 2017; 19: 312–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scheitz JF, Nolte CH, Doehner W, et al. Stroke-heart syndrome: clinical presentation and underlying mechanisms. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17: 1109–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hellwig S, Ihl T, Ganeshan R, et al. Cardiac troponin and recurrent major vascular events after minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. Ann Neurol 2021; 90: 901–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation 2018; 138: e618–e651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 1289–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandoval Y, Jaffe AS. Type 2 myocardial infarction: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 1846–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scheitz JF, Stengl H, Nolte CH, et al. Neurological update: use of cardiac troponin in patients with stroke. J Neurol 2021; 268: 2284–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stengl H, Ganeshan R, Hellwig S, et al. Cardiomyocyte injury following acute ischemic stroke: protocol for a prospective observational cohort study. JMIR Res Protoc 2021; 10: e24186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thygesen K, Mair J, Giannitsis E, et al. How to use high-sensitivity cardiac troponins in acute cardiac care. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2252–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scheitz JF, Gensicke H, Zinkstok SM, et al. Cohort profile: thrombolysis in ischemic stroke patients (TRISP): a multicentre research collaboration. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e023265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saver JL, Chaisinanunkul N, Campbell BCV, et al. Standardized nomenclature for modified rankin scale global disability outcomes: consensus recommendations from stroke therapy academic industry roundtable XI. Stroke 2021; 52: 3054–3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnston R, Jones K, Manley D. Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: a cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Qual Quant 2018; 52: 1957–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jensen JK, Ueland T, Aukrust P, et al. Highly sensitive troponin T in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Eur Neurol 2012; 68: 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anders B, Alonso A, Artemis D, et al. What does elevated high-sensitive troponin I in stroke patients mean: concomitant acute myocardial infarction or a marker for high-risk patients? Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 36: 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faiz KW, Thommessen B, Einvik G, et al. Determinants of high sensitivity cardiac troponin T elevation in acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kallmünzer B, Breuer L, Kahl N, et al. Serious cardiac arrhythmias after stroke: incidence, time course, and predictors–a systematic, prospective analysis. Stroke 2012; 43: 2892–2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. deFilippi C, Seliger SL, Kelley W, et al. Interpreting cardiac troponin results from high-sensitivity assays in chronic kidney disease without acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chem 2012; 58: 1342–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Linden N, Cornelis T, Kimenai DM, et al. Origin of cardiac troponin T elevations in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2017; 136: 1073–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sposato LA, Hilz MJ, Aspberg S, et al. Post-stroke cardiovascular complications and neurogenic cardiac injury: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76: 2768–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahn SH, Kim YH, Shin CH, et al. Cardiac vulnerability to cerebrogenic stress as a possible cause of troponin elevation in stroke. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Broersen LHA, Siegerink B, Sperber PS, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and cognitive function in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2020; 51: 1604–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yaghi S, Chang AD, Ricci BA, et al. Early elevated troponin levels after ischemic stroke suggests a cardioembolic source. Stroke 2018; 49: 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krause T, Werner K, Fiebach JB, et al. Stroke in right dorsal anterior insular cortex is related to myocardial injury. Ann Neurol 2017; 81: 502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873221120159 for Frequency, associated variables, and outcomes of acute myocardial injury according to the fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction in patients with acute ischemic stroke by Helena Stengl, Ramanan Ganeshan, Simon Hellwig, Markus G Klammer, Regina von Rennenberg, Sophie Böhme, Heinrich J Audebert, Christian H Nolte, Matthias Endres and Jan F Scheitz in European Stroke Journal