Abstract

Understanding the mechanics of acute kidney injury from toxins, ischemia and sepsis remains challenging. Molecular probes with high renal clearance have now been developed for real-time optical detection of early-stage biomarkers of drug-induced acute kidney injury, and for the understanding of the mechanisms of injury.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) panics physicians and frustrates nephrologists. A ‘bump’ or ‘spike’ in creatinine often precipitates a nephrology consult; unfortunately, the lack of scientific evidence leads to general advice of fluids, avoiding nephrotoxins and watchful waiting, but no specific therapy. In 2010, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and subsequently the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) credentialed a series of surrogate serum or plasma biomarkers for evaluation of drug toxicity in rodent models, in place of the histomorphologic evaluation of the kidneys1. In 2018, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium and Critical Path Institute developed a composite measure of six biomarkers into human clinical safety biomarkers, opening the door to stopping a drug before harm ensued2. Writing in Nature Materials, Kanyi Pu and colleagues3 describe imaging probes for the real-time evaluation of acute kidney injury in mouse models.

The AKI biomarker and drug development fields remain challenging, with only a handful of FDA-approved tests, which are not widely used. Development of drugs for the prevention or treatment of AKI has been stymied by the lack of robust early detection markers, infrequent hard outcomes such as dialysis or patient death in typical clinical trial scenarios, and reliance on biomarkers that do not directly measure renal function4. For example, the de facto biomarker of AKI — change in creatinine — that reports glomerular filtration is also heavily influenced by changes in extra-renal production and renal tubular transport. Despite many studies and trials, the development of AKI-specific biomarkers and drugs for AKI remains elusive. Many of these issues are driven by patient heterogeneity (AKIs not AKI, since it manifests with varying clinical profiles), and the lack of the human mechanistic data required to understand human AKIs and progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD). In 2017, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) initiated the Kidney Precision Medicine Program (KPMP) to merge the efforts to understand the pathophysiology and pathobiology at the molecular level of AKIs and CKDs5.

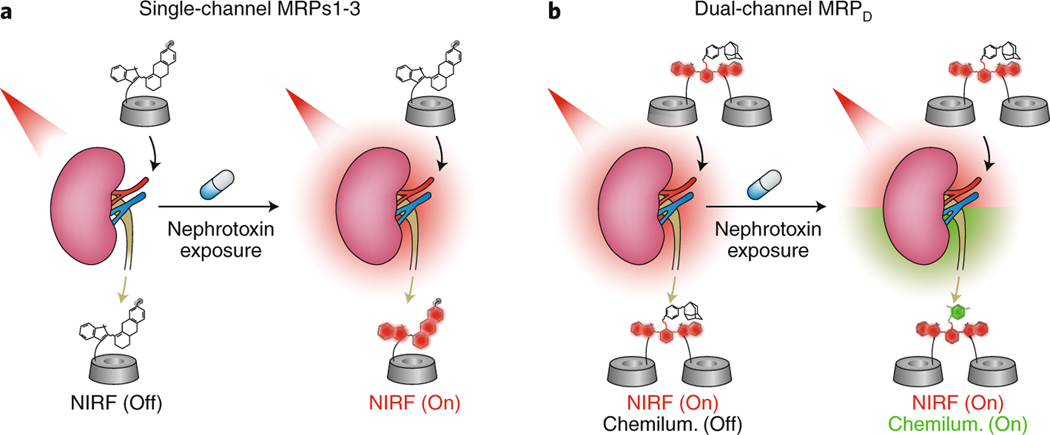

In this latest paper, Pu and colleagues describe the synthesis of advanced cleavable probes that report directly on renal molecular injury mechanisms. The molecular probes contain three components: biomarker reactive moieties, a luminescent signalling moiety and a renal clearance moiety. The probes were designed to individually detect superoxide anion (O2−), lysosomal enzyme N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) and caspase-3. These biomarkers were selected based on their role in the sequential progression of cellular injury, prior to detectable changes in glomerular filtration by serum creatinine. The probes were designed for single near-infrared fluorescence as well as dual fluorescence and chemiluminescence imaging (Fig. 1). Intravenous injection of the probes followed by simultaneous real-time near-infrared fluorescence and chemiluminescent imaging of mice after exposure to nephrotoxic agents demonstrated that signals in the kidneys could be detected progressively with time from the earliest biomarker (superoxide anion) to the late-stage biomarker (caspase-3). The chemiluminescent signal of the dual molecular renal probe was also detected following drug exposure, thereby creating a profile of the changes in the kidney as a function of time following drug exposure. The probes are informative beyond the in vivo imaging, as the cleaved probes can be detected in urine samples and in tissue. These newly developed probes detected changes associated with injury before there were noticeable changes in glomerular filtration as measured by serum creatinine, and ultimately outperformed current injury biomarkers.

Fig. 1 |. Molecular renal probes for the detection of drug-induced acute kidney injury.

a,b, Real-time detection of AKI following nephrotoxin exposure using single-channel molecular renal probes that rely on near infra-red fluorescence (NIRF) signals (a), and dual-channel molecular renal probes that rely on near infra-red fluorescence and chemiluminescent signals (b). Adapted from ref. 3, Springer Nature Ltd.

Clearly, these probes are a mechanistic step forward in understanding the progression of AKI in animal model systems. Although the data are from a murine model, and presumably can be quickly translated to other organisms, such as pigs, additional steps are needed for translation into humans, including testing against a wider range of acute, chronic and acute-on-chronic injury models in other laboratories to ensure rigour and reproducibility as well as extensive safety testing.

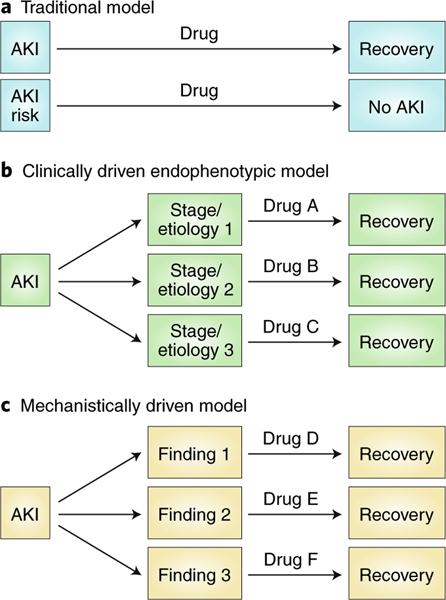

These non-invasive reporters are an important step forward in the molecular understanding of AKI. Even if the activated probes can only be detected in the urine (and not by a whole-body scanner), this may allow more detailed understanding of which pathways are activated in which settings or in which patients. The time frame (initiation and duration) and magnitude of the signal will provide further insight into the nature of the injury and recovery. If the reporters can be translated towards human use, they can be used to categorize patients into mechanistic endophenotypes that might respond to certain classes of repurposed or investigational drugs (Fig. 2)6. This could help research translation — by designing animal models that replicate human disease mechanisms, aiding classification of drugs by mechanism of action. The critical mechanistic information can be used in clinical trials as an element of enrolment or stratification to match patients with specific drugs, or to identify patients likely to respond to a given investigational agent, and to aid rational selection or drug dosage and treatment schedules. As they appear to be more sensitive than existing injury and functional biomarkers, they may allow earlier enrolment when a drug is more likely to act (therapeutic window). Ultimately, development of biomarkers that report on injury in the kidney will advance our understanding of AKI.

Fig. 2 |. The approaches conventially used in drug development for acute kidney injury.

a, Single therapies have been developed for all patients with AKI or at risk of AKI. b, Clinically driven endophenotypic approaches may rely on parameters such as the underlying etiology or the stage of the disease. c, Mechanistically driven endophenotypic approaches may be useful in the future to distinguish differences in pathophysiologic mechanisms of acute kidney injury. Adapted from ref. 6, ASN.

References

- 1.Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 431 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FNIH. https://fnih.org/what-we-do/biomarkers-consortium/programs/kidney-safety-biomarkers(2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang J, Li J, Lyu Y, Miao Q. & Pu K. Nat. Mater. 10.1038/s41563-019-0378-4(2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattes WB et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 432–433 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/research-funding/researchprograms/kidney-precision-medicine-project-kpmp(2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuk A. et al. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 13, 1113–1123 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]