Abstract

Uncontrolled immune system activation amplifies end-organ injury in hypertension. Nonetheless, the exact mechanisms initiating this exacerbated inflammatory response, thereby contributing to further increases in blood pressure (BP), are still being revealed. While participation of lymphoid-derived immune cells has been well described in the hypertension literature, the mechanisms by which myeloid-derived innate immune cells contribute to T cell activation, and subsequent BP elevation, remains an active area of investigation. In this article, we critically analyze the literature to understand how monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes, including mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils, contribute to hypertension and hypertension-associated end-organ injury. The most abundant leukocytes, neutrophils, are indisputably increased in hypertension. However, it is unknown how (and why) they switch from critical first responders of the innate immune system, and homeostatic regulators of BP, to tissue-damaging, pro-hypertensive mediators. We propose that myeloperoxidase-derived pro-oxidants, neutrophil elastase, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and interactions with other innate and adaptive immune cells are novel mechanisms that could contribute to the inflammatory cascade in hypertension. We further posit that the gut microbiota serves as a set point for neutropoiesis and their function. Finally, given that hypertension appears to be a key risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19 patients, we put forth evidence that neutrophils and NETs cause cardiovascular injury post-coronavirus infection, and thus may be proposed as an intriguing therapeutic target for high-risk individuals.

Immune System Activation and Inflammation in Hypertension

Acute inflammation is an important defense mechanism against danger (i.e., infection and cell injury), and facilitates the restoration of homeostasis. On the other end of the continuum, when inflammation goes unresolved, it can contribute to the genesis, maintenance, and worsening of many chronic diseases, including hypertension. In fact, low-grade chronic inflammation has been proposed as a unifying factor linking the three major organ systems responsible for the control of blood pressure (BP): the vasculature, the kidneys, and the brain. Nonetheless, the exact mechanisms that initiate this pathophysiologic response, thereby contributing to further increases in BP, are not well understood. While participation of hematopoietic cells in hypertension has been known for decades (153, 154, 203, 204, 229), the field of immune system activation in hypertension exploded in 2007 with Guzik et al. (74) seminal report that T cells were of particular importance in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Since then, a plethora of hypertension research has been focused on how T cells contribute to hypertension and what precisely activates T cells to mediate further increases in BP. The innate immune system has emerged as an obvious candidate (134).

The innate immune system is comprised of components expressed on peripheral tissues and myeloid-derived immune cells. Components of the innate immune system on non-immune cells include, for example, antimicrobial mediators on epithelial surfaces such as skin and mucosa, the complement system, and pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (e.g., Toll-like receptors and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain receptors) which recognize microbial products and host-derived danger signals. Myeloid-derived immune cells that make up the innate immune system include circulating monocytes, tissue infiltrating macrophages, antigen-presenting dendritic cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (aka granulocytes), such as mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils. These cells similarly contain antimicrobial mediators, the complement system, and PRRs. Collectively, the inflammatory milieu dictated by all these components of the innate immune system attempts to contain and mitigate tissue damage, and bridges the adaptive immune system, allowing it time to mount an antigen-specific response.

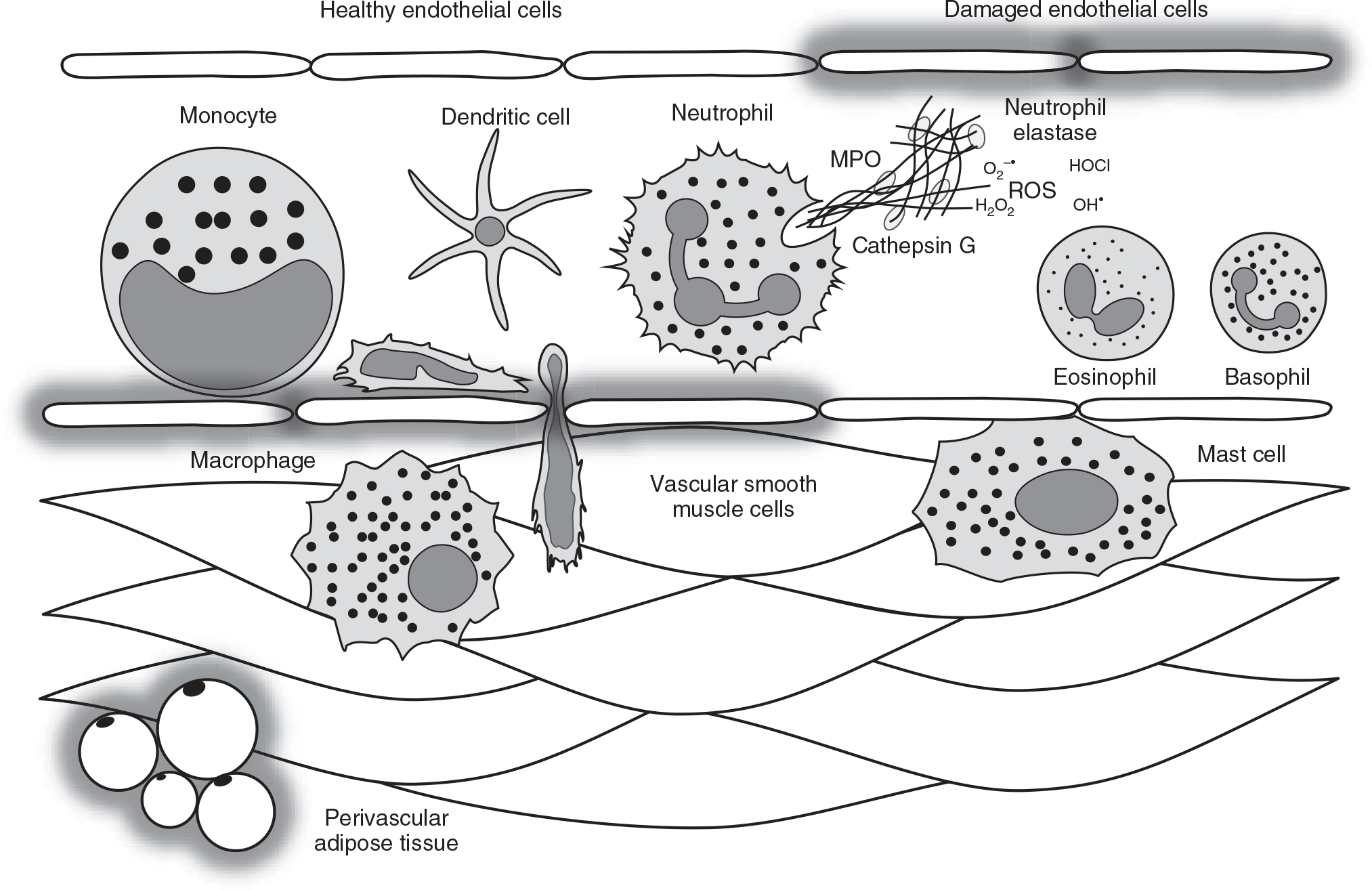

The main objective of this article is to discuss recent evidence on how myeloid-derived innate immune cells, and in particularly neutrophils, contribute to the pathophysiology of hypertension. First, we broadly review the literature on myeloid-derived innate immune cells in hypertension, and we follow this with an in-depth analysis at what makes neutrophils, the most abundant polymorphonuclear leukocyte, particularly detrimental to the organs important for BP control (Figure 1). Finally, we will discuss the role of neutrophils in mediating cardiovascular injury after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, given that hypertension is an important risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19 patients (251).

Figure 1.

Myeloid-derived immune cells that make up the innate immune system include circulating monocytes, tissue-resident macrophages, antigen-presenting dendritic cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (also termed granulocytes), such as mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Physiologically, these cells co-exist to maintain homeostasis. For example, acute and controlled activation of these cells dictates an inflammatory milieu that attempts to contain damage, facilitate tissue repair, and direct the adaptive immune system. On the other hand, chronic and uncontrolled activation of these cells can contribute to vascular damage, including endothelial dysfunction, medial thickening, and perivascular adipose tissue inflammation. For example, one of the major functions of activated neutrophils is the expulsion of their DNA as web-like chromatin structures termed neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). NETs are a network of extracellular fibers comprising primarily of DNA and citrullinated histone 3 released into the extracellular space in combination with other granule proteins, including neutrophil elastase, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and cathepsin G. This expelled DNA generates a pro-oxidative, pro-inflammatory, and pro-thrombotic milieu capable of inducing endothelial damage. Therefore, NETs are a novel mechanism of vascular injury in hypertension. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Monocytes and macrophages

Monocytes are the largest leukocyte in the human body. While their primary function is to circulate and replenish tissue-resident macrophages, monocytes can also generate cytokines as part of the immune response and perform phagocytosis. Phagocytosis in monocytes is performed by using intermediary (opsonizing) proteins such as antibodies or complement peptides that coat the pathogen/debris to be degraded, as well as by binding to PRRs. Monocytes are also capable of killing cells via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (244). Many factors produced by other cells regulate the chemotaxis and tissue infiltration of circulating monocytes.

Tissue infiltration of circulating monocytes results in their differentiation into the professional phagocyte, macrophages. Macrophages are the most abundant immune cells in tissues, including the organ systems involved in hypertension (79). Besides playing an integral role in the innate immune response, macrophages are imperative in the maintenance of homeostasis (e.g., tissue-resident macrophages have shown to be essential for physiology and development) (236). To carry out these duties, macrophages can polarize into subsets that express diverse phenotypes and functions. While several polarization states have been proposed, there is no clearly defined line of separation between each phenotype and therefore, macrophage polarization can be simplified to M1 and M2 populations (178). The concept of macrophage polarization was initially proposed when it was observed that macrophages exposed to interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) expressed a different gene expression profile than those exposed to interleukin (IL)-4 (148, 198). Accordingly, IFN-γ induces the differentiation of M1 macrophages, which are inflammatory and referred to as “classically activated” macrophages, whereas IL-4 induces the anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, which are categorized as “alternatively activated” (191). Based on functional stimuli and transcriptional changes, M2 macrophages have been further categorized into four subdivisions, M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d, though they are not completely characterized according to their functional role (79, 175). Accordingly, IL-4 or IL-13 activate M2a macrophages that induce IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β expression, while also enhancing endocytic activity, stimulating cell growth, and promoting tissue repair (242). Comparatively, M2b macrophages are activated by IL-1β and Toll-like receptor ligands, which release both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (175, 223). M2c macrophages are induced by glucocorticoids, IL-10, and TGF-β, for which they are important for secreting IL-10 and TGF-β and also promoting phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (38, 175, 254). Lastly, M2d macrophages are activated by Toll-like receptor antagonists, and release vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) and IL-10 that promote angiogenesis and tumor progression, respectively (63).

While the specific M2 subtype was not delineated, Binger et al. (22) recently reported that high-salt blunts M2 activation in vitro and in vivo, and this is not compensated with a preference for M1 polarization. This study further delineates that inhibition of M2 differentiation was triggered by high-salt mediated metabolic impairment in glycolysis and nutrient-sensing signaling (22), which implicates a novel mechanistic angle on the metabolic-immune axis in hypertension. Hence, this study provides the notion that perhaps blunting macrophage infiltration is not the only solution, but instigating M2 polarization and thus, promoting anti-inflammatory immune responses could be a therapeutic to alleviate hypertension and its associated tissue injury.

In hypertension research, circulating and endothelial adhering monocytes have been reported to be increased in all the major hypertensive animal models, including angiotensin II (44, 48, 84, 86, 92, 119, 139, 228) and aldosterone (132) induced hypertension, Goldblatt two-kidney, one-clip (2K1C) hypertension (81), spontaneously hypertensive rats (41, 75, 80, 124, 182, 205), deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt-induced hypertension (78), dietary salt and salt-sensitivity (12, 186, 227), and essential hypertension patients (51, 231, 249). Likewise, macrophage infiltration is demonstrated to be elevated in the vasculature (41, 48, 86, 124, 228), perivascular adipose tissue (62), myocardium (75), kidneys (44, 78, 80, 81, 84, 92, 119, 139), and the brain (62, 124, 205) of hypertensive animals. Several important investigations have demonstrated that monocytes and macrophages are instigators of organ dysfunction and high BP (44, 48, 80, 119, 168). Additionally, the measurement of monocytes/macrophages is commonly used as a phenotype of hypertensive end-organ injury (81, 84, 92), and as an indicator of anti-hypertensive therapy efficacy (237, 246).

Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells are professional antigen-presenting cells that bridge the innate and adaptive immune systems. Dendritic cells are equipped with molecular sensors and antigen-processing machinery to recognize danger, integrate chemical information, and guide the specificity, magnitude, and polarity of the adaptive immune response (42). There are several lineages of dendritic cells including, myeloid, plasmacytoid, CD14+ dendritic cells, and tissue-specific dendritic cells (particularly in stratified squamous epithelium and brain parenchyma) (42). Dendritic cells can be further defined based on their functional and anatomical classification, which includes blood/precursor dendritic cells, tissue/migratory dendritic cells, lymphoid/resident dendritic cells, and inflammatory dendritic cells. We refer the reader to the following review for a more comprehensive summary of dendritic cell lineages and functional and anatomical classifications (42).

Dendritic cells develop in the bone marrow, migrate as immature cells to sites of potential damage and antigen presence, and survey the peripheral microenvironment including gastrointestinal sampling. Once they encounter an antigen, they become activated and mature into effector cells that capture, process, and present antigens via their class I and II major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) to T cells, B cells, and Natural Killer (NK) cells in the lymph nodes. Dendritic cells can also initiate the innate immune response via PRRs, which can respond to danger signals (i.e., damage-associated molecular patterns, DAMPs) and microbial ligands (i.e., microbial-associated molecular patterns, MAMPs) (127). PRRs have been shown to trigger dendritic cell differentiation into immunogenic antigen-presenting cells capable of priming and sustaining the expansion of naive T cells, and thus exemplifying a mechanistic link between the innate to the adaptive immune system (171).

Most of our understanding of dendritic cells in hypertension has come fairly recently. Beyond their phenotypic recognition and presence in hypertension-associated end-organ injury (87, 237), it was only in 2010 that it was first reported that co-stimulatory molecules (e.g., CD80 and CD86) are increased in hypertension (217). After antigen presentation by MHC complexes, co-stimulation is the essential secondary signal required for T cell activation (35). Importantly, it was observed that pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of co-stimulatory molecules prevented angiotensin II- and DOCA salt-induced hypertension (217). These results were further refined with the subsequent reports that angiotensin II infusion can specifically activate dendritic cells to promote T cell proliferation and polarization toward an inflammatory phenotype (98). This study was complemented with the observation that isolevuglandin-protein adducts (also known as γ-ketoaldehydes or isoketals), which are highly reactive and harmful dicarbonyl lipid peroxidation products, were increased in hypertension and accumulated in dendritic cells (98). Recent evidence has indicated that dietary salt is also an important contributor of dendritic cell activation and the formation of isolevuglandins (16, 212). What remains to be confirmed is whether dendritic cells can initiate hypertension. They remain a plausible candidate given their link between the innate and adaptive immune systems. Evidence supporting this possibility is that scavenging isolevuglandins prevents dendritic cell activation, T cell proliferation, and hypertension, and that dendritic cells isolated from hypertensive donor mice predispose hypertension in low-dose angiotensin II recipient mice (98).

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes, including mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils, are also called granulocytes because they contain secretory granules in their cytoplasm that are released upon activation. Each of these granulocytes presents a repertoire of receptors on their cell surfaces that include receptors for immunoglobulin Fc, complement, cytokine, chemokine, and eicosanoids (among others) that primes and releases a unique arsenal of histamine, arachidonic acid metabolites, proteases, cytokines, chemokines, and cytotoxic proteins upon activation (200). The extent and pattern of granules released depend on the signal, its intensity, and the inflammatory milieu present. Further, these mediators can be both pre-formed and released rapidly (i.e., within seconds to minutes) or de novo synthesized and released gradually (i.e., after minutes to hours to days), which makes these granulocytes imperative for innate immunity.

Despite a recent Mendelian randomization study suggesting that an increase in non-lymphocyte leukocytes are a consequence of high BP and not the cause (192), it is undisputed that leukocytes are increased in the circulation (65, 90, 107, 182, 186) and end organs (3, 10, 143, 145, 185, 202, 235) of hypertensive patients and animals. When partitioning the effects of mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils it has been revealed that these cell types have diverse effects on end-organ function and BP. However, more work is necessary to fill in the gaps in this significantly understudied area of hypertension research.

Mast cells

Mast cells are tissue-resident granulocytes with high exposure to the external environment, such as epithelial surfaces and the vasculature. Due to their tissue localization, mast cells are major contributors to the early phase of allergic reactions. Mast cells function in hypertension are often overlooked because of similarities to macrophages and T cells (248). Moreover, mast cells have been reported to mediate opposing hemodynamic phenotypes. This is best evidenced in patients with mast cell activation disease. These patients experience both significant increases and decreases in BP, which can fluctuate rapidly from one state to the other (105). The underlying mechanisms of this clinical phenomenon may depend on the tissue where the mast cells are residing and/or the duration of mast cell activation. For example, most of the hypertensive animal models have investigated mast cells in deleterious cardiac remodeling (112, 113, 159, 160, 189) and renal mast cells contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertensive nephropathy (224). On the other hand, intravenous infusion of short cell-penetrating peptides, penetratin, and transportan, cause a significant, albeit transient, decrease in BP and this was blocked by a mast cell stabilizing agent (18). Further, when investigating individual constituents of the secretory granules released from mast cells, it is known that some of these induce vasodilation (94, 156), whereas others cause vasoconstriction (39, 85).

Eosinophils

Eosinophils are found both in the circulation and hematopoietic and lymphatic organs, such as the bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus. Our understanding of eosinophils in traditional hypertension models is limited. However, associations have been found between non-dipper hypertension (108) and hypertensive HIV patients (133). Likewise, eosinophil count is linked to deleterious vascular remodeling in patients with clinical suspicion of coronary heart disease (207), pulmonary arterial hypertension (226), and kidney injury (70). Interestingly, it has been observed that eosinophils are physiologic regulators of normal BP (232), vascular function (232), and metabolic homeostasis (234). Specifically, mice that lack eosinophils have increased mean arterial pressure (232), pro-contractile perivascular adipose tissue (232), and glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in response to a high-fat diet (234). Reconstitution of eosinophils ameliorates each of these dysfunctions (232, 234), which suggests that these immune cells are important for normal cardiovascular physiology and targeting them in hypertension should be cautioned.

Basophils

Basophils are generally only found in the circulation but are known to be rapidly recruited to inflamed tissues (200). To the best of our knowledge, there is no literature directly linking basophils and hypertension. Mechanisms have been proposed between basophils and kidney injury (25, 130) and our group has previously revealed an unexpected involvement of basophils, but not neutrophils or mast cells, to the hypotensive response after hemorrhagic shock (225). As basophils are the least abundant granulocyte population [~1% of circulating leukocytes (196)], this may explain why they have been relatively understudied in hypertension research.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocyte (myeloid- or lymphoid-derived) in the body. They are the first responders of the immune system and potently migrate toward sites of injury, infection, and/or inflammation following chemotactic signals such as IL-8, complement peptides, N-formyl peptides, leukotrienes, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (67). Neutrophils have three mechanisms for mediating immune defense: phagocytosis, degranulation, and the generation of extracellular traps. Initially, the neutrophil was described as a short-lived, non-discriminating killer. While this non-specific defense was important in controlling infection, it often resulted in significant collateral damage to host tissues in an effort to ensure the clearance of the pathogen. Importantly, we now know that neutrophils are essential for the initiation, perpetuation, and resolution of the immune response (174). For example, neutrophils are important for the clearance of cellular debris and the initiation of tissue repair process, which makes them central to the restoration, restitution, and maintenance of tissue homeostasis (174).

It is well established that hypertensive patients are neutrophilic (20, 123) and neutrophil depletion experiments have offered insight into the deleterious contribution of neutrophils in vascular (187), cardiac (60, 77, 193), renal (60, 167), and brain ischemic injury (103), as well as high BP (60, 170). Nonetheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying the functional switch of neutrophils from homeostatic regulators of BP (144), to pro-hypertensive mediators, remains the subject of intense research (34, 88, 140, 151, 152). Indeed, three major intrinsic functions of neutrophils, namely phagocytosis, degranulation, and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), could all be potential mechanisms of this switch, as wells as extrinsic interaction with other innate and adaptive immune cells.

Neutrophil-specific Components Exacerbate Inflammation in Hypertension

Neutrophil-derived reactive oxygen species

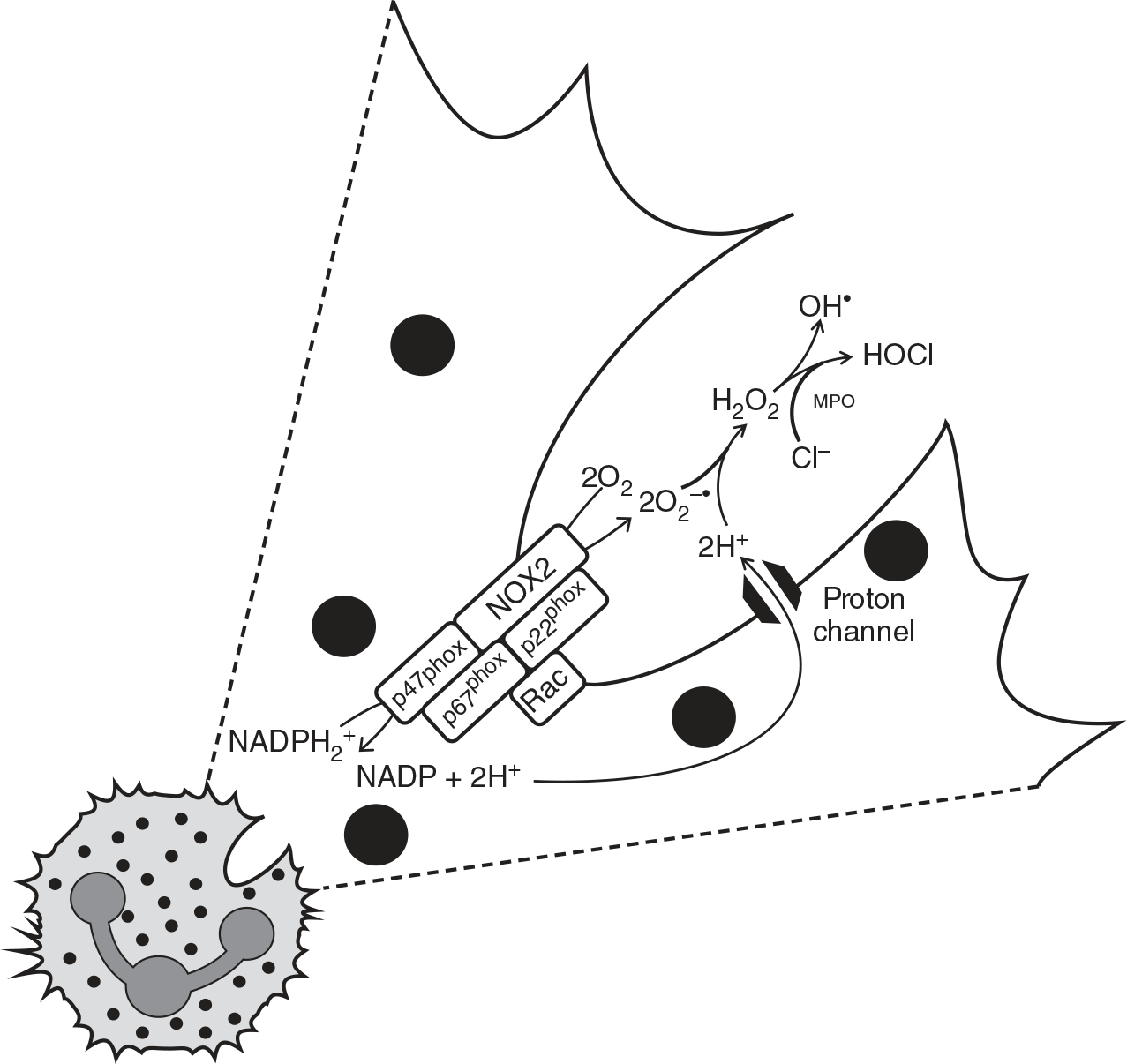

ROS (e.g., superoxide anion, singlet oxygen, hydroxyl radical) are short-lived, highly reactive molecules due to their unpaired valence electron. ROS are generated by specialized enzymes for cellular signaling, and also as a consequence of partial reduction of molecular O2 during mitochondrial respiration. When ROS generation is amplified to a point that overwhelms cellular/tissue antioxidant defenses, it is known as oxidative stress. It has been well established that ROS can virtually attack any cellular biomolecules (e.g., DNA, polyunsaturated fatty acids in biomembranes, and proteins) and cause oxidative damage which initiates and propagates many chronic diseases, including hypertension (211). In neutrophils, the major role of ROS is for immune defense as part of the oxidative/respiratory burst function (56). Accordingly, the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX)2 complex, a multi-subunit enzyme, produces superoxide from molecular O2, and subsequent conversion to other ROS, including the more stable and cell-permeable hydrogen peroxide. The neutrophil abundant protein, myeloperoxidase (MPO), converts hydrogen peroxide to hypohalous acid, which is a potent pro-oxidant and anti-microbial metabolite (194) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chemical reactions that make up the respiratory burst function in neutrophils via NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2). Classically, this is a potent antimicrobial defense against an invading pathogen. Upon endocytosis of the microbe (not depicted), NOX2 produces superoxide (O2−•) from molecular oxygen (O2), and then superoxide is then subsequently converted to other ROS, like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). In neutrophils, myeloperoxidase (MPO) converts H2O2 to hypohalous acid (HOCl). Based on Singel KL and Segal BH, 2016 (194).

Supporting the physiologic role of neutrophils in homeostatic BP regulation (144), it was observed that mice with NOX2 deficiency in myeloid-derived innate immune cells have a significantly reduced basal BP (179). However, the magnitude of BP increase in response to angiotensin II infusion was similar to control (179). Therefore, our understanding of how neutrophils cause hypertension-associated end-organ injury is far from complete, and we propose that MPO, neutrophil elastase (NE), and NETs exclusively expressed in neutrophils, are three novel mechanisms.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO): An enzymatic source of pro-oxidants in hypertension

MPO is a heme enzyme that catalyzes the generation of ROS including hypochlorous and hypothiocyanous acids (1, 125). MPO is abundantly expressed in neutrophils and released upon neutrophil activation (183). It is interesting to note that, unlike NOX2 which requires stringent cytosolic and membrane assembly of its multi-subunits for activation, MPO is active in its secreted/soluble form and thus possesses more pro-oxidant activity in the circulation and neutrophil infiltrated tissues. As such, MPO has been implicated as one potential mechanism by which neutrophils can promote cardiovascular disease (149). Specifically, MPO has been shown to be a strong biomarker for neutrophil infiltration in vascular injury (13, 26, 27, 59, 110) and BP (61, 173, 213). This association between MPO and high BP is strengthened with the knowledge that MPO is able to elicit endothelial dysfunction in vivo and ex vivo (177). These effects may be explained by MPO-dependent catabolism of nitric oxide (NO) into nitrite, followed by subsequent nitryl chloride and nitrogen dioxide production (14, 54, 55). Corroborating these studies, inhibition of MPO is able to increase indicators of NO bioavailability in cultured endothelial cells (173). These studies clearly indicate that MPO, vascular injury, and hypertension could be linked via the vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory NO pathway.

Neutrophil elastase (NE): A pathogenic neutrophil granule protein in hypertension

NE is a serine proteolytic enzyme exclusively produced by neutrophils (50, 97). NE is stored in large quantities within neutrophil azurophilic granules and is secreted at sites of inflammation (29). Protease and anti-protease balance are essential for proper immune response and restitution, where an imbalance between these factors has been suggested as a possible mechanism for neutrophil-mediated tissue damage (72). For example, NE causes proteolytic modification of inflammatory cytokines such as cleaving the pro-IL-1β into mature IL-1β and promoting its secretion (6). On the other hand, NE can also inactivate pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α (184) and IL-6 (15), which strengthens the concept that a balance between elastase and anti-elastase activity is essential.

Not surprisingly, elevated NE has been associated with endothelial damage (152), arterial stiffness (243), elevated BP (formerly termed “prehypertension”) (57), and hypertension (243). Interestingly, NE was also associated with pulmonary dysfunction in the same subjects with elevated BP (57), supporting the studies that have also shown that NE is involved in pulmonary hypertension (210). In line with this, cigarette smoking, which is a potent risk factor for pulmonary hypertension, results in the oxidation of methionine residues on the endogenous elastase inhibitor, which may play a role in the development of pulmonary emphysema (30). As a potential therapeutic, administration of an oral, synthetic, and selective NE inhibitor was found to reduce cell proliferation, vascular remodeling, and inflammation in a cigarette smoking-induced model of pulmonary hypertension (199, 233). The benefits of antagonizing NE activity could also be due, in part, to limiting ROS-induced NETs production (241). It must be cautioned though, that NE has the ability to perform an autoconversion to decrease the inhibitor efficacy of small-molecular antagonists (46).

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs): A novel mechanism of vascular damage

Along with their phagocytic activity and degranulation, NETs were recently identified as a novel mechanism of myeloid-derived immune cell activation (45) and serve as a trap to kill microbes. While this phenomenon has been particularly attributed to neutrophils (i.e., NETosis) (28), and has been at the forefront of a renewed interest in neutrophil biology (102), macrophages, mast cells, and eosinophils have also been reported to expel their DNA as web-like chromatin structures (161). During NETosis, the dedicated neutrophil enzyme peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 (PAD4, aka Padi4) removes the positively charged -NH2 group on the arginine residues of histone 3 (H3), which converts the arginine into citrulline (49). The loss of positive charge on H3 facilitates rapid de-condensation of DNA to be expelled out as “cobweb-like” NETs, comprising primarily of DNA decorated with other neutrophil granule proteins, including NE, MPO, and cathepsin G (66, 69). This network of extracellular DNA exerts potent anti-microbial, pro-inflammatory, pro-thrombotic, and cytotoxic properties capable of inducing endothelial dysfunction and damage (24). Evidence from literature has demonstrated a clear association between NETs and PAD4 in various cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis and thrombosis (21, 23, 24, 47, 52, 64, 166, 218) and pulmonary hypertension (5). With respect to hypertension, to the best of our knowledge, only Hofbauer et al. (82) have reported a positive correlation between BP and NETs, and angiotensin II and NADPH oxidase-derived ROS were identified as two pro-hypertensive factors important for NETs stimulation. Furthermore, our group has observed increased NETosis in peripheral neutrophils isolated from Dahl salt-sensitive rats compared to Dahl salt-resistant rats, as well as in hypertensive low capacity runner (LCR) rats compared to normotensive high capacity runner (HCR) rats (216).

To maintain blood and tissue integrity during inflammation, the host relies on deoxyribonucleases (DNases), such as DNase I and DNase I-like 3, as a dual-protection system against extracellular intravascular NETs by mediating their clearance in a timely fashion. Indeed, delayed clearance of NETs in systemic circulation can occlude blood vessels, which in turn damages erythrocytes and tissues (91). Observations suggest that DNase I and DNase I-like 3 play an important role to degrade NETs in the circulation during neutrophilia and septicemia and retain tissue integrity (91). Interestingly, DNase I has been reported to be decreased in spontaneously hypertensive rats (135) and DNase I-deficient mice spontaneously develop systemic lupus erythematosus (95), an autoimmune disease that also presents cardiovascular complications such as hypertension and endothelial dysfunction (9). DNase I-deficiency could also contribute to the increased extracellular presentation and prolonged exposure of sequestered neutrophil proteins (e.g., MPO) and PRR ligands. For example, NETs are also known to contain hypomethylated CpG DNA (136, 222). As a result, this hypomethylated CpG DNA may serve as a ligand for Toll-like receptor 9, a known contributor to the pathogenesis of hypertension (135). Moreover, NETs are found to be associated with autoimmune diseases like anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (111), where MPO can complex with ANCA and exhibit a distinct epitope specificity (176). Therefore, exogenous DNase I could serve as a potent therapeutic for alleviating autoimmunity, and possibly preventing hypertension through the timely clearance of NETs.

Alternatively, PAD4 inhibitors could be used to prevent NETs generation while preserving other critical neutrophil functions. The most effective inhibitor is the irreversible haloacetamidine compound, N-α-benzoyl-N5-(2-chloro-1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine amide (Cl-amidine), a recently described pan-PAD inhibitor, that has been shown to be effective against PAD4 in vitro and in vivo (7, 101, 129). Interestingly, Cl-amidine treatment reduced vascular damage and restrained innate immune responses in murine models of atherosclerosis (99), and lupus-associated endothelial dysfunction (100). Alongside, F-amidine is another potent and bioavailable irreversible inhibitor of PAD4 and is reported to be a potential lead compound for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (128). Comparatively, GSK199 and GSK484 are reversible PAD4 inhibitors that can disrupt mouse and human NETs formation (114). Altogether, the versatility of PAD4 inhibitors to alleviate various diseases that are associated with NETs dysregulation makes us enthusiastic that the use of these pharmacologic compounds could be beneficial in treating hypertension.

Collectively, we have discussed the functions of neutrophils and neutrophil products, such as MPO, NE, and NETs, in the pathogenesis of hypertension. While neutrophils are essential for host physiology because they are the primary responders to arrive at sites of inflammation, how they contribute to the development and/or maintenance of hypertension still remains to be elucidated. We propose that that MPO-derived pro-oxidants, NE, and NETs are important candidates to consider. Therefore, the cleavage of NETs and NET-specific markers (e.g., extracellular DNA and MPO-DNA complexes), by DNase I could be a novel therapeutic approach to ameliorate hypertension and prevent hypertension-associated cardiovascular damage. Furthermore, the utilization of Cl-amidine to inhibit PAD4 activity is perhaps required for limiting the citrullination of other proteins that may be involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension.

Gut microbiota intertwines with NETs and hypertension

Along with a dysregulated immune response, hypertension is strongly linked with gut microbiota dysbiosis (169). The gut microbiota consists of trillions of microbes from diverse taxa, but the dominant phyla are Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (126). Accordingly, an elevated Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio serves as a marker of gut dysbiosis, which is exhibited in multiple metabolic, intestinal, cardiovascular, and renal diseases (58, 115, 116, 155, 172, 209, 245). As delineated through hypertensive rat models, shifts in the intestinal bacterial communities involve a dramatic reduction in microbial richness and diversity, which encompasses an increased Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio (117, 240). Comparatively, we have discovered that in Dahl salt-sensitive rats, Bacteroidetes are more abundant compared to Dahl salt-resistant rats (138), which signifies the complexity of hypertension and the necessity to consider both the host genome and metagenome. Human studies, including a cross-sectional, epidemiologic study conducted from participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults, found that systolic BP and hypertension were inversely associated with α-diversity and bacterial richness (201, 240). It is noteworthy that comprehensive metagenomic and metabolomic analyses were sufficient to accurately classify pre-hypertensive and hypertensive patients based on their gut microbiota and metabolite profiles (117). Direct relation of the gut microbiota and hypertension is further demonstrated as germ-free mice exhibit elevated BP after fecal transplantation from human hypertensive patients (117). This is analogous to the development of hypertension in normotensive Wistar Kyoto rats after cecal microbiotal transfer from spontaneously hypertensive rats (4). Furthermore, our group recently revealed that resistance arteries from germ-free mice have hypocontractility relative to wild-type controls (53), indicating that the gut microbiota are essential for normal vascular contractility, and potentially suggesting a pro-hypertensive mechanism of dysbiosis.

The connection between gut dysbiosis and hypertension has been at the forefront of hypertension in recent years (31). However, the mechanistic understanding on how the gut microbiota affects the function of organs that control BP (i.e., the kidneys and the resistance vasculature) is still being elucidated. The current dogma is focused on gut metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (131, 147, 163, 164, 208, 230, 240). While this research is significant, we would like to add that there is a paucity of knowledge on the potential mechanistic contribution of the gut microbiota on neutrophil function in hypertension. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has proposed this link. Specifically, it was observed that angiotensin II infused into germ-free mice have less neutrophil infiltration into the aorta compared to sham mice, and this is associated with attenuated cardiac and kidney inflammation, fibrosis, and systolic dysfunction (93).

Considering that hypertension is associated with a disruption in gut homeostasis, including decreased tight junction proteins that result in increased intestinal permeability (181), the subsequent “leaky gut” can release various gut bacteria and microbial products that could cause unintended activation of neutrophils. It is interesting to note that germ-free mice and rats are neutropenic and once colonized with microbiota their levels reach to normal levels as observed in conventional animals (animals with indigenous gut microbiota) (239), suggesting that gut microbiota and their products/metabolites are necessary for maintaining normal levels of circulating neutrophils. For example, release of peptidoglycan from the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall was found traced to the bone marrow and primed neutrophil activation through nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 1 (NOD1) signaling (40). Additionally, translocation of the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall component lipopolysaccharide (LPS; a ligand for Toll-like receptor 4) and D-lactate correlated with systemic inflammation and cardiovascular complications post-myocardial infarction (253). Intriguingly, LPS is one of the most potent ligands for recruiting neutrophils (8) and inducing NETosis (11, 118, 122, 150, 162). Similarly, microbiota-dependent formylated peptide Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) is also effective in inducing neutrophil chemotaxis (190) and NETs formation (150). In contrast, we have shown that enterobactin, an iron-chelating siderophore secreted by some gut bacteria like Enterobacteriaceae (Escherichia coli), can inhibit neutrophil functions such as ROS and NETs generation including MPO activity (180, 195), which suggests that the gut microbiota is a source of both neutrophil activators and inhibitors.

Appraising the established mechanisms of gut dysbiosis and dysfunctional neutrophil response in hypertension, we propose the novel corollary that gut dysbiosis potentiates hypertension via neutrophilia and ROS and NETs overproduction. This further signifies that rebalancing the gut microbiota [e.g., with probiotics (96) or antibiotics (68)] might be a potent therapeutic intervention to normalize the inappropriate immune responses of neutrophils to the gut microbiota during hypertension pathogenesis.

Neutrophils prime and activate other immune cells

In recent years, it has become evident that neutrophils are not only first responders of the innate immune system, but they also contribute to the propagation of inflammation by interacting with other innate and adaptive immune cells (142). For example, neutrophils accumulate in the splenic marginal zone upon microbial challenge and facilitate the antibody production and maturation of marginal zone B cells in response to T cell-independent antigens (165). Furthermore, neutrophils can participate in a vicious cycle during the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases by releasing NETs that trigger plasmacytoid dendritic cells to release IFN-α, which then promote antibody production by B cells (109). Neutrophils may also directly present antigens to T cells (2, 19), and they can also deliver activation antigens to dendritic cells (137). Finally, neutrophils can activate NK cells (89, 197). Given that of T cells (74), B cells (32), dendritic cells (98), and NK cells (106) have all been demonstrated to be essential for the development and maintenance of hypertension, understanding if neutrophils participate in the priming and/or activation of these other pro-hypertensive immune cells is a critical gap in the literature that still remains to be filled.

Neutrophils and Nets Increase Cardiovascular Risk After SARS-CoV-2 Infection

SARS-CoV-2 is the novel viral pathogen that is responsible for the development of the current pandemic named COVID-19. Despite SARS-CoV-2 having a primary target for the respiratory system, COVID-19 patients also exhibit multi-organ damage, including cardiovascular injury (73, 83, 104, 188, 221) and endothelitis (214). Moreover, COVID-19 patients with pre-existing conditions, including hypertension, have a poor prognosis after infection and an increased risk for mortality (73, 83, 104, 188, 221).

Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection in hypertensive patients has been partially attributed to the compensatory upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)2 due to drugs prescribed to treat pre-existing cardiovascular conditions (36). It is well known that renin-angiotensin system inhibitors are first-line anti-hypertensive therapeutics (37) and SARS-CoV-2 uses ACE2 as the receptor to hijack host entry (157, 206, 220, 238, 252). However, infection alone does not totally account for the damage to multiple organ systems (219), including the cardiovascular system (73, 83, 221, 250). Moreover, this injury, on top of underlying end-organ damage from chronic high BP, could explain some of the increased morbidity and mortality of hypertension patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. After SARS-CoV-2 enters the host and infection subsequently ensues, this is associated with down-regulation of ACE2 expression and activity (76, 158, 215). This reduction in ACE2 can ultimately contribute to an inadequate immune response (121), including a delayed pro-inflammatory cytokine storm, which then elicits an overcompensated neutrophil and macrophage infiltration that causes greater tissue damage (33) Indeed, neutrophilia and increased lung-infiltrating neutrophils are associated with COVID-19 disease (17, 120, 141, 247).

When neutrophils enter the site of infection, they are capable of sensing viral particles through PRRs (i.e., Toll-like receptors), which can lead to secondary signals for NETs production. Recently, it has emerged that NETs are involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection (255). Specifically, Zuo et al. (255) found that COVID-19 patients have elevated sera levels of cell-free DNA, MPO-DNA complexes, and citrullinated H3. This study further revealed that the neutrophils isolated from COVID-19 patients triggered more NETs release upon stimulation compared to controls (255). As a result of this important study, we propose that NETs are a novel mechanism of cardiovascular damage after SARS-CoV-2 infection. In support of this hypothesis, excessive NETs have been observed to have pathogenic effects on acute respiratory distress syndrome and influenza pneumonia that follows H1N1 infection, where blunting NETs production by depleting neutrophils reduces lung pathology in infected mice (146). Furthermore, administering DNase I served to degrade NETs and protect against LPS-induced acute lung injury (122). This is analogous to the observation that DNase I protects against NETs-mediated vascular occlusion (91) and reduces NETs-induced airway obstruction (43). Therefore, abrogating NETs via DNase I may serve as a therapeutic approach to help defend against SARS-CoV-2 and/or the unintended cardiovascular injury that occurs due to the inappropriate neutrophil response (71).

Therefore, while ACE2 is a commonality between cardiovascular physiology and COVID-19 pathophysiology, blocking the anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive effects of ACE2 may cause other unwarranted consequences during COVID-19 disease. As an alternative approach, we suggest that targeting NETs may be an novel option to ameliorate the overzealous neutrophil responses (71).

Conclusion

In summary, myeloid-derived innate immune cells, and specifically neutrophils, are unequivocally involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension and COVID-19-associated cardiovascular injury. While neutrophils are undoubtedly increased in hypertension, whether they are causative of hypertension, or only a consequence of hypertension-associated end-organ damage, is still a subject of great debate. Regardless, revelation of neutrophil-specific factors such as MPO-dependent ROS, NE, and NETs, as well as unique interactions of other innate and adaptive immune cells, reveal previously unidentified mechanisms that can contribute to the development and/or maintenance of hypertension. This includes pinpointing a potential mechanism by which gut microbiota regulates the production of NETs in organs important for the control of BP. It cannot be understated that there are a growing number of mechanisms that can contribute to the activation and direction of the innate and adaptive immune systems in hypertension.

Didactic Synopsis.

Major Teaching Points

Inflammation is a homeostatic mechanism against danger (i.e., infection and cell injury).

On the other hand, unresolved inflammation underlies many chronic conditions, including cardiovascular diseases.

In hypertension, inflammation is a unifying etiological factor linking the three major organ systems responsible for blood pressure control—the vasculature, the kidneys, and the brain.

While adaptive immune system, and in particularly T cells, has been well described in hypertension, less is known about the innate immune system.

The innate immune system is comprised of components expressed on peripheral tissues and myeloid-derived immune cells.

Myeloid-derived immune cells include circulating monocytes, tissue infiltrating macrophages, antigen-presenting dendritic cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (aka granulocytes), such as mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils.

Neutrophils are essential “first responders” of the innate immune system. Hypertensive patients and animals have elevated neutrophils, where uncontrolled neutrophil responses can mediate cardiovascular injury and increase blood pressure.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the American Heart Association (18POST34060003), National Institutes of Health (K99HL151889, R01CA219144, R01HL143082, and R00GM118885), and the University of Toledo Medical Research Society grant for COVID-19 research.

References

- 1.Abdo AI, Rayner BS, van Reyk DM, Hawkins CL. Low-density lipoprotein modified by myeloperoxidase oxidants induces endothelial dysfunction. Redox Biol 13: 623–632, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abi Abdallah DS, Egan CE, Butcher BA, Denkers EY. Mouse neutrophils are professional antigen-presenting cells programmed to instruct Th1 and Th17 T-cell differentiation. Int Immunol 23: 317–326, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu Nabah YN, Losada M, Estelles R, Mateo T, Company C, Piqueras L, Lopez-Gines C, Sarau H, Cortijo J, Morcillo EJ, Jose PJ, Sanz MJ. CXCR2 blockade impairs angiotensin II-induced CC chemokine synthesis and mononuclear leukocyte infiltration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 2370–2376, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adnan S, Nelson JW, Ajami NJ, Venna VR, Petrosino JF, Bryan RM Jr, Durgan DJ. Alterations in the gut microbiota can elicit hypertension in rats. Physiol Genomics 49: 96–104, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aldabbous L, Abdul-Salam V, McKinnon T, Duluc L, Pepke-Zaba J, Southwood M, Ainscough AJ, Hadinnapola C, Wilkins MR, Toshner M, Wojciak-Stothard B. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote angiogenesis: Evidence from vascular pathology in pulmonary hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 36: 2078–2087, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfaidi M, Wilson H, Daigneault M, Burnett A, Ridger V, Chamberlain J, Francis S. Neutrophil elastase promotes interleukin-1beta secretion from human coronary endothelium. J Biol Chem 290: 24067–24078, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aliko A, Kaminska M, Falkowski K, Bielecka E, Benedyk-Machaczka M, Malicki S, Koziel J, Wong A, Bryzek D, Kantyka T, Mydel P. Discovery of novel potential reversible peptidyl arginine deiminase inhibitor. Int J Mol Sci 20: 2174, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andonegui G, Bonder CS, Green F, Mullaly SC, Zbytnuik L, Raharjo E, Kubes P. Endothelium-derived Toll-like receptor-4 is the key molecule in LPS-induced neutrophil sequestration into lungs. J Clin Invest 111: 1011–1020, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aranow C, Ginzler EM. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 9: 166–169, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arndt H, Smith CW, Granger DN. Leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Hypertension 21: 667–673, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arroyo R, Khan MA, Echaide M, Perez-Gil J, Palaniyar N. SP-D attenuates LPS-induced formation of human neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), protecting pulmonary surfactant inactivation by NETs. Commun Biol 2: 470, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asagami T, Reaven GM, Tsao PS. Enhanced monocyte adherence to thoracic aortae from rats with two forms of experimental hypertension. Am J Hypertens 12: 890–893, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldus S, Heeschen C, Meinertz T, Zeiher AM, Eiserich JP, Munzel T, Simoons ML, Hamm CW, CAPTURE Investigators. Myeloperoxidase serum levels predict risk in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 108: 1440–1445, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldus S, Heitzer T, Eiserich JP, Lau D, Mollnau H, Ortak M, Petri S, Goldmann B, Duchstein HJ, Berger J, Helmchen U, Freeman BA, Meinertz T, Munzel T. Myeloperoxidase enhances nitric oxide catabolism during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med 37: 902–911, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bank U, Kupper B, Reinhold D, Hoffmann T, Ansorge S. Evidence for a crucial role of neutrophil-derived serine proteases in the inactivation of interleukin-6 at sites of inflammation. FEBS Lett 461: 235–240, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbaro NR, Foss JD, Kryshtal DO, Tsyba N, Kumaresan S, Xiao L, Mernaugh RL, Itani HA, Loperena R, Chen W, Dikalov S, Titze JM, Knollmann BC, Harrison DG, Kirabo A. Dendritic cell amiloride-sensitive channels mediate sodium-induced inflammation and hypertension. Cell Rep 21: 1009–1020, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes BJ, Adrover JM, Baxter-Stoltzfus A, Borczuk A, Cools-Lartigue J, Crawford JM, Dassler-Plenker J, Guerci P, Huynh C, Knight JS, Loda M, Looney MR, McAllister F, Rayes R, Renaud S, Rousseau S, Salvatore S, Schwartz RE, Spicer JD, Yost CC, Weber A, Zuo Y, Egeblad M. Targeting potential drivers of COVID-19: Neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med 217: e20200652, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basheer M, Schwalb H, Shefler I, Levdansky L, Mekori YA, Gorodetsky R. Blood pressure modulation following activation of mast cells by cationic cell penetrating peptides. Peptides 32: 2444–2451, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beauvillain C, Delneste Y, Scotet M, Peres A, Gascan H, Guermonprez P, Barnaba V, Jeannin P. Neutrophils efficiently cross-prime naive T cells in vivo. Blood 110: 2965–2973, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belen E, Sungur A, Sungur MA, Erdogan G. Increased neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with resistant hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 17: 532–537, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berezin A Neutrophil extracellular traps: The core player in vascular complications of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr 13: 3017–3023, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binger KJ, Gebhardt M, Heinig M, Rintisch C, Schroeder A, Neuhofer W, Hilgers K, Manzel A, Schwartz C, Kleinewietfeld M, Voelkl J, Schatz V, Linker RA, Lang F, Voehringer D, Wright MD, Hubner N, Dechend R, Jantsch J, Titze J, Muller DN. High salt reduces the activation of IL-4- and IL-13-stimulated macrophages. J Clin Invest 125: 4223–4238, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonaventura A, Vecchie A, Abbate A, Montecucco F. Neutrophil extracellular traps and cardiovascular diseases: An update. Cells 9: 231, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borissoff JI, Joosen IA, Versteylen MO, Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, Gallant M, Martinod K, Ten Cate H, Hofstra L, Crijns HJ, Wagner DD, Kietselaer B. Elevated levels of circulating DNA and chromatin are independently associated with severe coronary atherosclerosis and a prothrombotic state. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 2032–2040, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosch X, Lozano F, Cervera R, Ramos-Casals M, Min B. Basophils, IgE, and autoantibody-mediated kidney disease. J Immunol 186: 6083–6090, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brennan ML, Penn MS, Van Lente F, Nambi V, Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Goormastic M, Pepoy ML, McErlean ES, Topol EJ, Nissen SE, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain. N Engl J Med 349: 1595–1604, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brevetti G, Schiano V, Laurenzano E, Giugliano G, Petretta M, Scopacasa F, Chiariello M. Myeloperoxidase, but not C-reactive protein, predicts cardiovascular risk in peripheral arterial disease. Eur Heart J 29: 224–230, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303: 1532–1535, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carne CA, Dockerty G. Genital warts: Need to screen for coinfection. BMJ 300: 459, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carp H, Miller F, Hoidal JR, Janoff A. Potential mechanism of emphysema: Alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor recovered from lungs of cigarette smokers contains oxidized methionine and has decreased elastase inhibitory capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79: 2041–2045, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakraborty S, Mandal J, Yang T, Cheng X, Yeo JY, McCarthy CG, Wenceslau CF, Koch LG, Hill JW, Vijay-Kumar M, Joe B. Metabolites and hypertension: Insights into hypertension as a metabolic disorder: 2019 Harriet Dustan Award. Hypertension 75: 1386–1396, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan CT, Sobey CG, Lieu M, Ferens D, Kett MM, Diep H, Kim HA, Krishnan SM, Lewis CV, Salimova E, Tipping P, Vinh A, Samuel CS, Peter K, Guzik TJ, Kyaw TS, Toh BH, Bobik A, Drummond GR. Obligatory role for B cells in the development of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 66: 1023–1033, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: Causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol 39: 529–539, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen AY, DeLano FA, Valdez SR, Ha JN, Shin HY, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Receptor cleavage reduces the fluid shear response in neutrophils of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C1441–C1449, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 227–242, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L, Li X, Chen M, Feng Y, Xiong C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res 116: 1097–1100, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen YJ, Li LJ, Tang WL, Song JY, Qiu R, Li Q, Xue H, Wright JM. First-line drugs inhibiting the renin angiotensin system versus other first-line antihypertensive drug classes for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11: CD008170, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chistiakov DA, Bobryshev YV, Nikiforov NG, Elizova NV, Sobenin IA, Orekhov AN. Macrophage phenotypic plasticity in atherosclerosis: The associated features and the peculiarities of the expression of inflammatory genes. Int J Cardiol 184: 436–445, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho C, Nguyen A, Bryant KJ, O’Neill SG, McNeil HP. Prostaglandin D2 metabolites as a biomarker of in vivo mast cell activation in systemic mastocytosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Immun Inflamm Dis 4: 64–69, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke TB, Davis KM, Lysenko ES, Zhou AY, Yu Y, Weiser JN. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat Med 16: 228–231, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clozel M, Kuhn H, Hefti F, Baumgartner HR. Endothelial dysfunction and subendothelial monocyte macrophages in hypertension. Effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition. Hypertension 18: 132–141, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collin M, Bigley V. Human dendritic cell subsets: An update. Immunology 154: 3–20, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cortjens B, de Jong R, Bonsing JG, van Woensel JBM, Antonis AFG, Bem RA. Local dornase alfa treatment reduces NETs-induced airway obstruction during severe RSV infection. Thorax 73: 578–580, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crowley SD, Song YS, Sprung G, Griffiths R, Sparks M, Yan M, Burchette JL, Howell DN, Lin EE, Okeiyi B, Stegbauer J, Yang Y, Tharaux PL, Ruiz P. A role for angiotensin II type 1 receptors on bone marrow-derived cells in the pathogenesis of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 55: 99–108, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daniel C, Leppkes M, Munoz LE, Schley G, Schett G, Herrmann M. Extracellular DNA traps in inflammation, injury and healing. Nat Rev Nephrol 15: 559–575, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dau T, Sarker RS, Yildirim AO, Eickelberg O, Jenne DE. Autoprocessing of neutrophil elastase near its active site reduces the efficiency of natural and synthetic elastase inhibitors. Nat Commun 6: 6722, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Boer OJ, Li X, Teeling P, Mackaay C, Ploegmakers HJ, van der Loos CM, Daemen MJ, de Winter RJ, van der Wal AC. Neutrophils, neutrophil extracellular traps and interleukin-17 associate with the organisation of thrombi in acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost 109: 290–297, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Ciuceis C, Amiri F, Brassard P, Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice: Evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 2106–2113, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demers M, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular traps: A new link to cancer-associated thrombosis and potential implications for tumor progression. Oncoimmunology 2: e22946, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dollery CM, Owen CA, Sukhova GK, Krettek A, Shapiro SD, Libby P. Neutrophil elastase in human atherosclerotic plaques: Production by macrophages. Circulation 107: 2829–2836, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorffel Y, Latsch C, Stuhlmuller B, Schreiber S, Scholze S, Burmester GR, Scholze J. Preactivated peripheral blood monocytes in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension 34: 113–117, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doring Y, Soehnlein O, Weber C. Neutrophil extracellular traps in atherosclerosis and atherothrombosis. Circ Res 120: 736–743, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edwards JM, Roy S, Tomcho JC, Schreckenberger ZJ, Chakraborty S, Bearss NR, Saha P, McCarthy CG, Vijay-Kumar M, Joe B, Wenceslau CF. Microbiota are critical for vascular physiology: Germ-free status weakens contractility and induces sex-specific vascular remodeling in mice. Vascul Pharmacol 125–126: 106633, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eiserich JP, Baldus S, Brennan ML, Ma W, Zhang C, Tousson A, Castro L, Lusis AJ, Nauseef WM, White CR, Freeman BA. Myeloperoxidase, a leukocyte-derived vascular NO oxidase. Science 296: 2391–2394, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eiserich JP, Hristova M, Cross CE, Jones AD, Freeman BA, Halliwell B, van der Vliet A. Formation of nitric oxide-derived inflammatory oxidants by myeloperoxidase in neutrophils. Nature 391: 393–397, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Benna J, Hurtado-Nedelec M, Marzaioli V, Marie JC, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Dang PM. Priming of the neutrophil respiratory burst: Role in host defense and inflammation. Immunol Rev 273: 180–193, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El-Eshmawy MM, El-Adawy EH, Mousa AA, Zeidan AE, El-Baiomy AA, Abdel-Samie ER, Saleh OM. Elevated serum neutrophil elastase is related to prehypertension and airflow limitation in obese women. BMC Womens Health 11: 1, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Emoto T, Yamashita T, Kobayashi T, Sasaki N, Hirota Y, Hayashi T, So A, Kasahara K, Yodoi K, Matsumoto T, Mizoguchi T, Ogawa W, Hirata KI. Characterization of gut microbiota profiles in coronary artery disease patients using data mining analysis of terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism: Gut microbiota could be a diagnostic marker of coronary artery disease. Heart Vessels 32: 39–46, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Exner M, Minar E, Mlekusch W, Sabeti S, Amighi J, Lalouschek W, Maurer G, Bieglmayer C, Kieweg H, Wagner O, Schillinger M. Myeloperoxidase predicts progression of carotid stenosis in states of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 2212–2218, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fabbiano S, Menacho-Marquez M, Robles-Valero J, Pericacho M, Matesanz-Marin A, Garcia-Macias C, Sevilla MA, Montero MJ, Alarcon B, Lopez-Novoa JM, Martin P, Bustelo XR. Immunosuppression-independent role of regulatory T cells against hypertension-driven renal dysfunctions. Mol Cell Biol 35: 3528–3546, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fang J, Ma L, Zhang S, Fang Y, Su P, Ma H. Association of myeloperoxidase gene variation with carotid atherosclerosis in patients with essential hypertension. Mol Med Rep 7: 313–317, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Faraco G, Sugiyama Y, Lane D, Garcia-Bonilla L, Chang H, Santisteban MM, Racchumi G, Murphy M, Van Rooijen N, Anrather J, Iadecola C. Perivascular macrophages mediate the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension. J Clin Invest 126: 4674–4689, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferrante CJ, Pinhal-Enfield G, Elson G, Cronstein BN, Hasko G, Outram S, Leibovich SJ. The adenosine-dependent angiogenic switch of macrophages to an M2-like phenotype is independent of interleukin-4 receptor alpha (IL-4Ralpha) signaling. Inflammation 36: 921–931, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Franck G, Mawson TL, Folco EJ, Molinaro R, Ruvkun V, Engelbertsen D, Liu X, Tesmenitsky Y, Shvartz E, Sukhova GK, Michel JB, Nicoletti A, Lichtman A, Wagner D, Croce KJ, Libby P. Roles of PAD4 and NETosis in experimental atherosclerosis and arterial injury: Implications for superficial erosion. Circ Res 123: 33–42, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedman GD, Selby JV, Quesenberry CP Jr. The leukocyte count: A predictor of hypertension. J Clin Epidemiol 43: 907–911, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, Weinrauch Y, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 176: 231–241, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Futosi K, Fodor S, Mocsai A. Neutrophil cell surface receptors and their intracellular signal transduction pathways. Int Immunopharmacol 17: 638–650, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Galla S, Chakraborty S, Cheng X, Yeo JY, Mell B, Chiu N, Wenceslau CF, Vijay-Kumar M, Joe B. Exposure to amoxicillin in early life is associated with changes in gut microbiota and reduction in blood pressure: Findings from a study on rat dams and offspring. J Am Heart Assoc 9: e014373, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gasser O, Hess C, Miot S, Deon C, Sanchez JC, Schifferli JA. Characterisation and properties of ectosomes released by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Exp Cell Res 285: 243–257, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gauckler P, Shin JI, Mayer G, Kronbichler A. Eosinophilia and kidney disease: More than just an incidental finding? J Clin Med 7: 529, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Golonka RM, Saha P, Yeoh BS, Chattopadhyay S, Gewirtz AT, Joe B, Vijay-Kumar M. Harnessing innate immunity to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 and ameliorate COVID-19 disease. Physiol Genomics 52: 217–221, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Groutas WC, Dou D, Alliston KR. Neutrophil elastase inhibitors. Expert Opin Ther Pat 21: 339–354, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, Wang H, Wan J, Wang X, Lu Z. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 5: 811–818, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 204: 2449–2460, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haller H, Behrend M, Park JK, Schaberg T, Luft FC, Distler A. Monocyte infiltration and c-fms expression in hearts of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 25: 132–138, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanff TC, Harhay MO, Brown TS, Cohen JB, Mohareb AM. Is there an association between COVID-19 mortality and the renin-angiotensin system – a call for epidemiologic investigations. Clin Infect Dis 71: 870–874, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hansen PR. Role of neutrophils in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation 91: 1872–1885, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hartner A, Porst M, Gauer S, Prols F, Veelken R, Hilgers KF. Glomerular osteopontin expression and macrophage infiltration in glomerulosclerosis of DOCA-salt rats. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 153–164, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harwani SC. Macrophages under pressure: The role of macrophage polarization in hypertension. Transl Res 191: 45–63, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harwani SC, Ratcliff J, Sutterwala FS, Ballas ZK, Meyerholz DK, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM. Nicotine mediates CD161a+ renal macrophage infiltration and premature hypertension in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Circ Res 119: 1101–1115, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hilgers KF, Hartner A, Porst M, Mai M, Wittmann M, Hugo C, Ganten D, Geiger H, Veelken R, Mann JF. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage infiltration in hypertensive kidney injury. Kidney Int 58: 2408–2419, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hofbauer T, Scherz T, Müller J, Heidari H, Staier N, Panzenböck A, Mangold A, Lang IM. Arterial hypertension enhances neutrophil extracellular trap formation via an angiotensin-II-dependent pathway. Atherosclerosis 263: e67–e68, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497–506, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang L, Wang A, Hao Y, Li W, Liu C, Yang Z, Zheng F, Zhou MS. Macrophage depletion lowered blood pressure and attenuated hypertensive renal injury and fibrosis. Front Physiol 9: 473, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ihara M, Urata H, Kinoshita A, Suzumiya J, Sasaguri M, Kikuchi M, Ideishi M, Arakawa K. Increased chymase-dependent angiotensin II formation in human atherosclerotic aorta. Hypertension 33: 1399–1405, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ishibashi M, Hiasa K, Zhao Q, Inoue S, Ohtani K, Kitamoto S, Tsuchihashi M, Sugaya T, Charo IF, Kura S, Tsuzuki T, Ishibashi T, Takeshita A, Egashira K. Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 on monocytes in hypertension-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Circ Res 94: 1203–1210, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Itani HA, Xiao L, Saleh MA, Wu J, Pilkinton MA, Dale BL, Barbaro NR, Foss JD, Kirabo A, Montaniel KR, Norlander AE, Chen W, Sato R, Navar LG, Mallal SA, Madhur MS, Bernstein KE, Harrison DG. CD70 exacerbates blood pressure elevation and renal damage in response to repeated hypertensive stimuli. Circ Res 118: 1233–1243, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ito BR, Schmid-Schonbein G, Engler RL. Effects of leukocyte activation on myocardial vascular resistance. Blood Cells 16: 145–163; discussion 163–146, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jaeger BN, Donadieu J, Cognet C, Bernat C, Ordonez-Rueda D, Barlogis V, Mahlaoui N, Fenis A, Narni-Mancinelli E, Beaupain B, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Bajenoff M, Malissen B, Malissen M, Vivier E, Ugolini S. Neutrophil depletion impairs natural killer cell maturation, function, and homeostasis. J Exp Med 209: 565–580, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jiang HM, Wang HX, Yang H, Zeng XJ, Tang CS, Du J, Li HH. Role for granulocyte colony stimulating factor in angiotensin II-induced neutrophil recruitment and cardiac fibrosis in mice. Am J Hypertens 26: 1224–1233, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jimenez-Alcazar M, Rangaswamy C, Panda R, Bitterling J, Simsek YJ, Long AT, Bilyy R, Krenn V, Renne C, Renne T, Kluge S, Panzer U, Mizuta R, Mannherz HG, Kitamura D, Herrmann M, Napirei M, Fuchs TA. Host DNases prevent vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps. Science 358: 1202–1206, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Yoshimura A, Lombardi D, Pritzl P, Floege J, Schwartz SM. Renal injury from angiotensin II-mediated hypertension. Hypertension 19: 464–474, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Karbach SH, Schonfelder T, Brandao I, Wilms E, Hormann N, Jackel S, Schuler R, Finger S, Knorr M, Lagrange J, Brandt M, Waisman A, Kossmann S, Schafer K, Munzel T, Reinhardt C, Wenzel P. Gut microbiota promote angiotensin II-induced arterial hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e003698, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kelm M, Feelisch M, Krebber T, Motz W, Strauer BE. Mechanisms of histamine-induced coronary vasodilatation: H1-receptor-mediated release of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. J Vasc Res 30: 132–138, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kenny EF, Raupach B, Abu Abed U, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Dnase1-deficient mice spontaneously develop a systemic lupus erythematosus-like disease. Eur J Immunol 49: 590–599, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khalesi S, Sun J, Buys N, Jayasinghe R. Effect of probiotics on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Hypertension 64: 897–903, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim YM, Haghighat L, Spiekerkoetter E, Sawada H, Alvira CM, Wang L, Acharya S, Rodriguez-Colon G, Orton A, Zhao M, Rabinovitch M. Neutrophil elastase is produced by pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and is linked to neointimal lesions. Am J Pathol 179: 1560–1572, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kirabo A, Fontana V, de Faria AP, Loperena R, Galindo CL, Wu J, Bikineyeva AT, Dikalov S, Xiao L, Chen W, Saleh MA, Trott DW, Itani HA, Vinh A, Amarnath V, Amarnath K, Guzik TJ, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ, Shyr Y, Chen SC, Mernaugh RL, Laffer CL, Elijovich F, Davies SS, Moreno H, Madhur MS, Roberts J 2nd, Harrison DG. DC isoketal-modified proteins activate T cells and promote hypertension. J Clin Invest 124: 4642–4656, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knight JS, Luo W, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Subramanian V, Guo C, Grenn RC, Thompson PR, Eitzman DT, Kaplan MJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition reduces vascular damage and modulates innate immune responses in murine models of atherosclerosis. Circ Res 114: 947–956, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Knight JS, Zhao W, Luo W, Subramanian V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Hodgin JB, Eitzman DT, Thompson PR, Kaplan MJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition is immunomodulatory and vasculoprotective in murine lupus. J Clin Invest 123: 2981–2993, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Knuckley B, Luo Y, Thompson PR. Profiling Protein Arginine Deiminase 4 (PAD4): A novel screen to identify PAD4 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem 16: 739–745, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kobayashi Y Neutrophil biology: An update. EXCLI J 14: 220–227, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kochanek PM, Hallenbeck JM. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes/macrophages in the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia and stroke. Stroke 23: 1367–1379, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kochi AN, Tagliari AP, Forleo GB, Fassini GM, Tondo C. Cardiac and arrhythmic complications in patients with COVID-19. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 31: 1003–1008, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kolck UW, Haenisch B, Molderings GJ. Cardiovascular symptoms in patients with systemic mast cell activation disease. Transl Res 174: 23–32.e1, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kossmann S, Schwenk M, Hausding M, Karbach SH, Schmidgen MI, Brandt M, Knorr M, Hu H, Kroller-Schon S, Schonfelder T, Grabbe S, Oelze M, Daiber A, Munzel T, Becker C, Wenzel P. Angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction depends on interferon-gamma-driven immune cell recruitment and mutual activation of monocytes and NK-cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 1313–1319, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kristal B, Shurtz-Swirski R, Chezar J, Manaster J, Levy R, Shapiro G, Weissman I, Shasha SM, Sela S. Participation of peripheral polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 11: 921–928, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kuzeytemiz M, Demir M, Şentürk M. The relationship between eosinophil and nondipper hypertension. Cor et Vasa 55: e487–e491, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, Frasca L, Conrad C, Gregorio J, Meller S, Chamilos G, Sebasigari R, Riccieri V, Bassett R, Amuro H, Fukuhara S, Ito T, Liu YJ, Gilliet M. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med 3: 73ra19, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lau D, Baldus S. Myeloperoxidase and its contributory role in inflammatory vascular disease. Pharmacol Ther 111: 16–26, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee KH, Kronbichler A, Park DD, Park Y, Moon H, Kim H, Choi JH, Choi Y, Shim S, Lyu IS, Yun BH, Han Y, Lee D, Lee SY, Yoo BH, Lee KH, Kim TL, Kim H, Shim JS, Nam W, So H, Choi S, Lee S, Shin JI. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in autoimmune diseases: A comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev 16: 1160–1173, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Levick SP, McLarty JL, Murray DB, Freeman RM, Carver WE, Brower GL. Cardiac mast cells mediate left ventricular fibrosis in the hypertensive rat heart. Hypertension 53: 1041–1047, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Levick SP, Murray DB, Janicki JS, Brower GL. Sympathetic nervous system modulation of inflammation and remodeling in the hypertensive heart. Hypertension 55: 270–276, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lewis HD, Liddle J, Coote JE, Atkinson SJ, Barker MD, Bax BD, Bicker KL, Bingham RP, Campbell M, Chen YH, Chung CW, Craggs PD, Davis RP, Eberhard D, Joberty G, Lind KE, Locke K, Maller C, Martinod K, Patten C, Polyakova O, Rise CE, Rudiger M, Sheppard RJ, Slade DJ, Thomas P, Thorpe J, Yao G, Drewes G, Wagner DD, Thompson PR, Prinjha RK, Wilson DM. Inhibition of PAD4 activity is sufficient to disrupt mouse and human NET formation. Nat Chem Biol 11: 189–191, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11070–11075, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444: 1022–1023, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, Chen J, Tao J, Tian G, Wu S, Liu W, Cui Q, Geng B, Zhang W, Weldon R, Auguste K, Yang L, Liu X, Chen L, Yang X, Zhu B, Cai J. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome 5: 14, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Li RHL, Ng G, Tablin F. Lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil extracellular trap formation in canine neutrophils is dependent on histone H3 citrullination by peptidylarginine deiminase. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 193–194: 29–37, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Liao TD, Yang XP, Liu YH, Shesely EG, Cavasin MA, Kuziel WA, Pagano PJ, Carretero OA. Role of inflammation in the development of renal damage and dysfunction in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 52: 256–263, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]