Abstract

Introduction:

Heterozygous variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway are associated with obesity. However, their effect on the long-term outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is still unknown.

Methods:

In this matched case-control study, 701 participants from the Mayo Clinic Biobank with a history of RYGB were genotyped. Sixty-three patients had a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway. After excluding patients with potential confounders, carriers were randomly matched (on sex, age, body-mass index [BMI], and years since surgery) with two non-carrier controls. The electronic medical record of carriers and matched non-carriers was reviewed for up to 15 years after RYGB.

Results:

A total of 50 carriers and 100 matched non-carriers with a history of RYGB were included in the study. Seven different genes (LEPR, PCSK1, POMC, SH2B1, SRC1, MC4R, and SIM1) in the leptin-melanocortin pathway were identified. At the time of surgery, the mean age was 50.8±10.6 years, BMI 45.6±7.3 kg/m2, 79% women. There were no differences in postoperative years of follow-up, Roux limb length, or gastric pouch size between groups. Fifteen years after RYGB, the %TBWL in carriers was −16.6±10.7 compared with −28.7±12.9 in non-carriers (diff=12.1%, 95% CI, 4.8 to 19.3) and weight regain after maximum weight loss was 52.7±29.7% in carriers compared with 29.8±20.7% in non-carriers (diff=22.9%, 95% CI, 5.3 to 40.5). The nadir %TBWL was lower −32.1±8.1% in carriers compared with −36.8±10.4 in non-carriers (diff=4.8%, 95% CI 1.8 to 7.8).

Conclusions:

Carriers of a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway have a progressive and significant weight regain in the mid- and long-term after RYGB. Genotyping patients experiencing significant weight regain after RYGB could help implement multidisciplinary and individualized weight-loss interventions to improve weight maintenance after surgery.

Keywords: Leptin-Melanocortin Pathway, Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery, Genetic Obesity

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Obesity is a heterogeneous and multifactorial disease1 that affects over 650 million adults and 124 million children and adolescents worldwide2. Heterozygous variants in genes of the leptin-melanocortin pathway have a frequency of 0.1–6% in patients with obesity3.

The leptin-melanocortin pathway is essential in energy balance regulation4. In the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus, the anorexigenic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) expressing neurons sense leptin through the leptin receptor (LEPR)5. Activation of the LEPR stimulates the synthesis of POMC through the downstream interaction of the steroid coreceptor activator-1 (SRC1) protein with the phosphorylated form of STAT3, and the Src homology 2 B adaptor protein 1 (SH2B1). POMC is cleaved by the proconvertase 1 enzyme, encoded by the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1) gene, to yield alpha-melanocyte stimulant hormone (αMSH). αMSH stimulates the melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R) on neurons expressing the single-minded 1 (SIM1) gene in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Activation of the MC4R in the PVN by upstream signals from the ARC regulates energy intake and expenditure.

Currently, five antiobesity medications are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the long-term management of common obesity, each with different effectiveness and side effects profile6. In 2020, the FDA approved setmelanotide (an MC4R agonist) for the treatment of obesity in patients with POMC, PCSK1, and LEPR homozygous variants7. Clinical trials are studying the effects of setmelanotide in patients with heterozygous variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway which have a higher frequency than homozygous variants (NCT03013543; NCT02507492).

Despite the advent of obesity pharmacotherapy, bariatric surgery, particularly Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), is still the most effective therapy for sustained long-term weight loss and improvement in obesity-related comorbidities8,9. The underlying mechanisms responsible for the remarkable outcomes following RYGB are not completely understood. Neurohormonal adaptations in the adipose-gut-brain axis and changes in the regulation of food intake seem to be critical to achieving these outcomes10. However, it is unknown if these neurohormonal adaptations are as effective and persistent in patients with carriers of a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway compared with non-carriers11. Studies attempting to answer this question 12–28 have been limited by the short time of follow-up, the small group of carriers, or by studying only one gene. Moreover, most studies have assessed the weight loss outcomes of RYGB altogether with other bariatric procedures (i.e., sleeve gastrectomy [SG] and adjustable gastric banding [AGB]) that differ in weight loss magnitude and mechanism 29.

Therefore, this study aimed to study the long-term outcomes of RYGB in patients with a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway. We hypothesized that patients with a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway will have inferior long-term weight loss outcomes after RYGB compared with patients without a heterozygous variant.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

In this retrospective, matched case-control study, we assessed the Mayo Clinic Biobank30, containing self-reported health questionnaires, biological samples, and data from electronic medical records (EMR) of 50,000 participants. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Mayo Clinic (IRB 18–010159), and all participants provided prior written authorization for research use of their medical records and biological samples, including their use for genotyping studies. We identified participants from the Mayo Clinic Biobank who were older than 18 years old, had a history of RYGB, and >2 mcg of genomic DNA available for analysis. Samples from eligible participants were sequenced, and only patients with a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway (hereinafter referred to as “carriers”) were included in the study. To avoid potential confounders, participants with any of the following were excluded: 1) less than six months since RYGB, 2) any bariatric reintervention or revisional procedure, 3) use of any FDA-approved (or discontinued) antiobesity medication(s) (i.e., phentermine, phentermine/topiramate, liraglutide, bupropion/naltrexone, orlistat, lorcaserin, and/or sibutramine) after RYGB, and/or 4) pregnancy after RYGB. Carriers with no identified confounders were randomly matched with two eligible controls from the pool of non-carriers with no identified confounders. Matching criteria were age within five years, sex, body mass index (BMI) within two units, and years since surgery within 2 years. If more than two non-carriers met the matching criteria available for a case, controls were selected randomly from the pool of eligible non-carriers.

Genetic Variants Selected and Sequencing Panel Analysis

A total of 30 genes of the leptin-melanocortin pathway previously related to obesity and/or bariatric surgery outcomes were selected for gene sequencing (Table 1 in Supplement) 4,5,12–28,31–33. Sequencing was performed at Sema4 Laboratories (Stamford, CT, USA). Submitted DNA was resuspended in Tris-HCl using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter). Eluted DNA was quantified via Qubit dsDNA assay (ThermoFisher) using a Biotek Synergy HTX fluorometer, and eluate volume was measured using a BioMicroLab VolumeCheck 100. NGS libraries were prepared using 200 ng DNA and KAPA HyperPlus (Roche) reagents and unique dual indexes (IDT) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were hybridized with custom-designed XGen probes (IDT), pooled, and gene sequenced using 2×100 bp v4 chemistry on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 following the manufacturer’s instructions to a mean coverage of 200x.

Passing filter reads meeting run and library-level QC criteria were processed via a GATK-based pipeline on DNAnexus (Mountain View, CA, USA). Briefly, BAM files were generated using GRCh37/hg19 reference. Upon additional read filtering and quality recalibration of the aligned BAM files, variants were then called using HaplotypeCaller. Variants with depth >20, quality>100, and variant allele frequency between 0.25 and 0.6 (heterozygous) or greater than 0.925 (homozygous) were included in the analyses. Finally, variants were filtered for rarity (in October 2018) with a <1% maximum continental frequency in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) and further annotated according to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG). Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS)34 nomenclature recommendations were used to describe sequence variants.

Data Collection and Outcome Definitions

Demographic and anthropometric data were extracted manually by a blinded systematic review of the EMR of carriers and their matched non-carrier controls for up to 15 years after the date of RYGB. Height was obtained in meters at baseline (i.e., at time of surgery) and weight in kilograms at baseline, at months 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18, and yearly thereafter from year 2 to 15. Data were abstracted from the information of follow-up visits. Weight was measured based on a standard protocol without shoes on electronic scales which are calibrated daily. We used a 3-month range for the annual weight abstraction and a 15-day range for the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 18-months time points. We assessed weight loss using the formula for the percentage of total body weight loss (%TBWL): [100*(baseline weight – each post-surgery time point weight)]/baseline weight35. The nadir value (defined as the lowest value after baseline) for weight, BMI, and %TBWL was calculated for each carrier and non-carrier in the analysis. Weight regain was calculated at 5, 10, and 15 years using the formula for percentage of weight regain after maximum weight loss: [100*(weight at 10, or 15 years – nadir weight)]/(baseline weight – nadir weight), as it has a better association with clinical outcomes after bariatric surgery than other weight regain formulas36. Comorbidities diagnoses were abstracted from preoperative evaluation notes or medical encounters in the 3 months before surgery. The surgical procedure was performed by the Division of Endocrine & Metabolic Surgery at Mayo Clinic following a standardized technique, creating a gastric pouch, an antecolic gastrojejunostomy, a Roux-limb, and a side-to-side jejunojejunostomy. Data was abstracted between December 2020 and February 2021 and analysis was performed between February and June 2021.

Study End Points

The primary endpoint was %TBWL at 15 years after RYGB. The secondary endpoints were the nadir %TBWL, %TBWL at 5 and 10 years, and weight regain at 5, 10, and 15

Statistical Analysis

We used JMP®, Version 14.3.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2019) to perform statistical analysis. The results are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), counts (percentages), or median (interquartile range [IQR]) when indicated. We used descriptive statistics to present demographic and anthropometric data. Categorical data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Results are presented with their respective 95% confidence interval (CI). Multiple linear regression was used to analyze %TBWL, weight regain, and nadir %TBWL, with adjustments for the baseline characteristic of age, sex, BMI, diabetes, and years since surgery. The regression coefficient (β) was reported from the multiple linear regression model. All tests were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline (Table 4 in Supplement).

Results

Pathway Variants

From the 50,000 participants in the Biobank, 701 had a history of RYGB, and their samples were sent for genotyping. Sixty-three (8.9%) patients were identified as carriers of a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway. After excluding patients with potential confounders, 50 carriers and 100 matched non-carriers were included in the primary analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). In the fifty included patients, we identified 40 variants in seven different genes from the leptin-melanocortin pathway, five genes upstream to the MC4R (LEPR, PCSK1, POMC, SH2B1, and SRC1), and two downstream (SIM1 and MC4R) (Table 1). The observed frequency of these heterozygous variants was 7.1% for all seven genes (1.3% for LEPR, 0.4% for PCSK1, 1.9% for POMC, 1.1% for SH2B1, 1.4% for SRC1, 0.7% for SIM1, and 0.3% for MC4R). The two compound heterozygous carriers (LEPR [p.Asn347Ser, p.Val754Met]; MC4R [p.Asp37Val, p.Tyr35*]) were not included in the primary analysis and are described separately in the Supplement. The estimated clinical significance according to the ACMG, gnomAD frequency, combined annotation dependent depletion (CADD), PolyPhen 2, and SIFT scores from variants are presented in Table 2 in the Supplement.

Table 1.

Heterozygous Variants in the Leptin-Melanocortin Pathwaya

| Gene | Description | Locus | Variant(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream pathway | |||

|

LEPR (n=9) |

Leptin receptor | 1p31.3 | p.Cys954Phe, p.Arg612His, p.Val144Leu, p.Tyr747Asp, p.Ser950Thr, p.Arg514Gly, p.Val344Ile, p.Val984Ala, p.Pro401Leu. |

|

PCSK1 (n=3) |

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 | 5q15‐ q21 | p.Arg110Cys, p.Ala185Gly, p.Thr640Ala |

|

POMC (n=13) |

Pro‐ opiomelanocortin | 2p23.3 | p.Pro194Ala, p.Phe144Leu, p.Cys5Tyr, p.His143Gln, p.Arg48Gln, p.Arg236Gly, p.Thr39Met, p.Pro132Ala p.Tyr221Cys |

|

SH2B1 (n=8) |

SH2B adaptor protein 1 | 16.p11.2 | p.Arg46His, p.Pro700Ser, p.His607Arg, p.Pro191Thr, p.Arg66His, p.Arg67His, p.Glu250Gly |

|

SRC1 (n=10) |

Steroid receptor coactivator 1 | 2p23.3 | p.His431Arg, p.Gly1405Arg, p.Ala857Thr, p.Thr1026Ile, p.Met791Val, p.Thr1219Ala p.Asn1332Ser, p.Arg572Ser, |

| Downstream pathway | |||

|

SIM1 (n=5) |

Single‐ minded 1 | 6q16.3‐ q21 | p.Asp707His, p.Asp590Glu |

|

MC4R (n=2) |

Melanocortin receptor 4 | 18q22 | p.Leu325Phe, p.Gln156* |

Abbreviations:

Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) recommendations are used to describe sequence variants

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Participants were predominantly female and Caucasian. The mean (±standard deviation [SD]) age was 50.8±10.6 years and BMI 45.6±7.3 kg/m2. RYGB procedure was performed mainly by laparoscopic approach. There were no differences in the baseline prevalence of diabetes mellitus, binge eating disorder (BED), and other comorbidities. There were no differences in the surgery technique between carriers and non-carriers, in carriers, 75% of the procedures were laparoscopic compared to 82% in non-carriers (p=0.41). The Roux limb length was 145.8±28 cm in carriers compared to 154.8±52.7 cm in non-carriers (p=0.18), The gastric pouch size was 22.7±7.4 mL in carriers compared to 22.8±7.7 mL in non-carriers (p=0.96). The attrition rate (i.e., loss to follow-up) 15 years after surgery was 6.25% (n=1/16) in carriers and 23.2% (n=10/43) in non-carriers.

Table 2.

Baseline participant characteristics. Variables are expressed as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified.

| All (n=150) |

Carriers (n=50) |

Non-carriers (n=100) |

Difference (95% Confidence Interval) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demographics

| |||||

| Age, years | 50.8 (10.6) | 49.6 (11.7) | 51.3 (10) | −1.7 (−5.6 – 2.1) | 0.38 |

| Sex, Female (%) | 118 (79%) | 39 (78%) | 79 (79%) | 1.0 | |

| Self-reported race, Caucasian (%) | 143 (95%)a | 46 (92%)b | 97 (97%)c | 0.23 | |

|

Anthropometrics | |||||

| Weight, kg | 126.1 (23.8) | 125.6 (21.2) | 126.3 (25.1) | −0.7 (−8.5 – 7) | 0.85 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 45.6 (7.3) | 45.3 (6.4) | 45.7 (7.7) | −0.4 (−2.8 – 2) | 0.74 |

|

Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes Mellitus (%) | 54 (36) | 16 (32) | 38 (25) | 0.59 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 85 (57) | 26 (52) | 59 (59) | 0.49 | |

| Cardiovascular Disease (%) | 30 (20) | 8 (16) | 22 (22) | 0.52 | |

| Binge Eating Disroderd (%) | 3 (2) | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.26 | |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 79 (53) | 25 (50) | 54 (54) | 0.73 | |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea (%) | 80 (54) | 29 (59) | 51 (51) | 0.39 | |

|

Procedure Characteristics | |||||

| Time since surgery, years | 10.5 (4.2) | 11.9 (5.9) | 13.3 (5.4) | −1.4 (−3.3 – 0.6) | 0.17 |

| Laparoscopic, (%) | 116 (77%) | 41 (82%) | 75 (75%) | 0.41 | |

| Roux limb length, cm | 151.8 (46) | 145.8 (28) | 154.8 (52.7) | −9 (−22.1 – 4.2) | 0.18 |

| Gastric pouch, mL | 22.8 (7.5) | 22.7 (7.4) | 22.8 (7.7) | −0.08 (−3.4 – 3.2) | 0.96 |

Abbreviations used: BMI, body mass index.

1% Asian, 2% African American, 1% American Indian/Alaskan, 1% Caribbean

2% Caribbean, 4% African American, 2% American Indian/Alaskan Native

1% Asian, 1% African American, 1% American Indian/Alaskan Native

diagnosed by DSM-V criteria

Weight Change after RYGB

Total Body Weight Loss

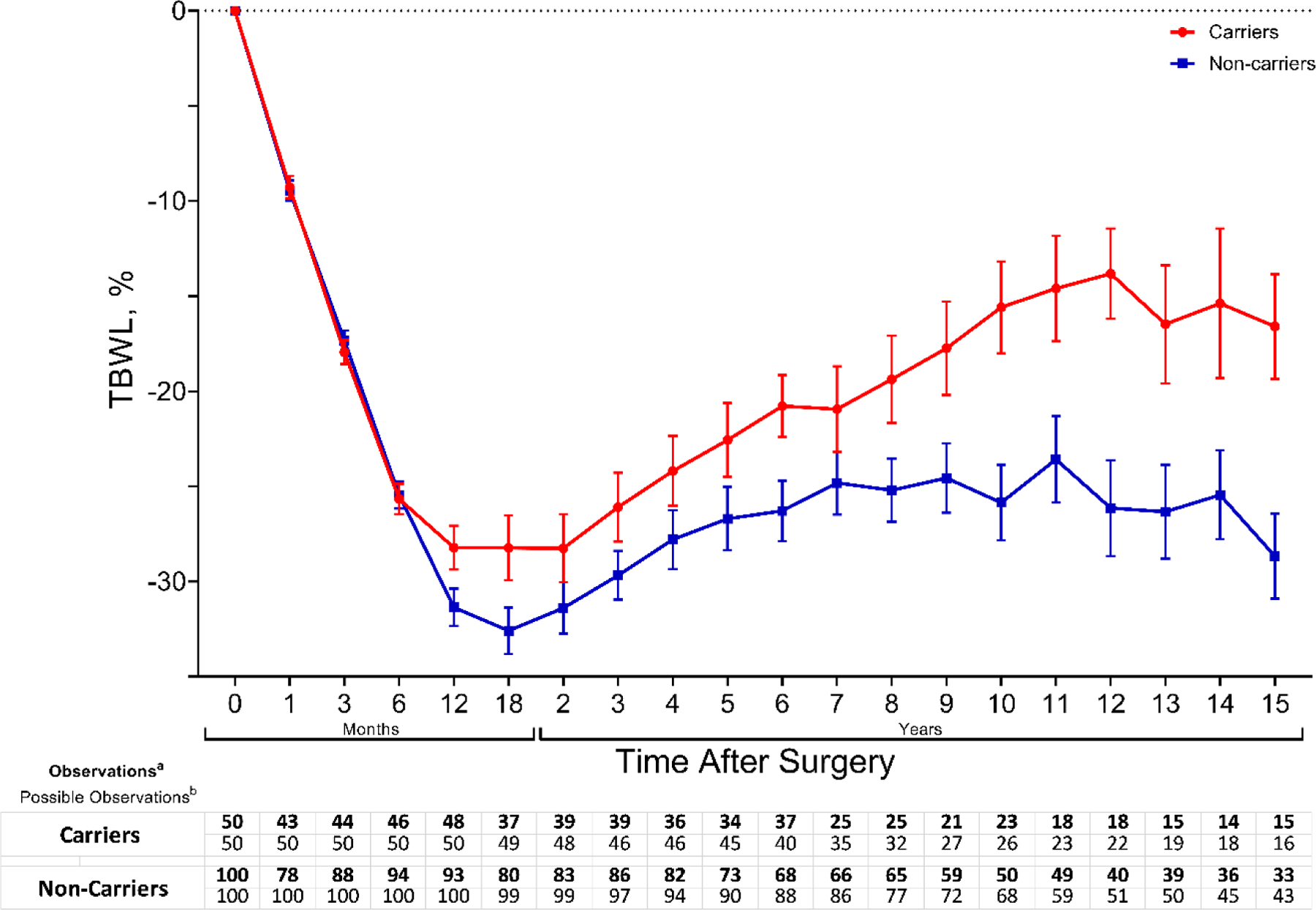

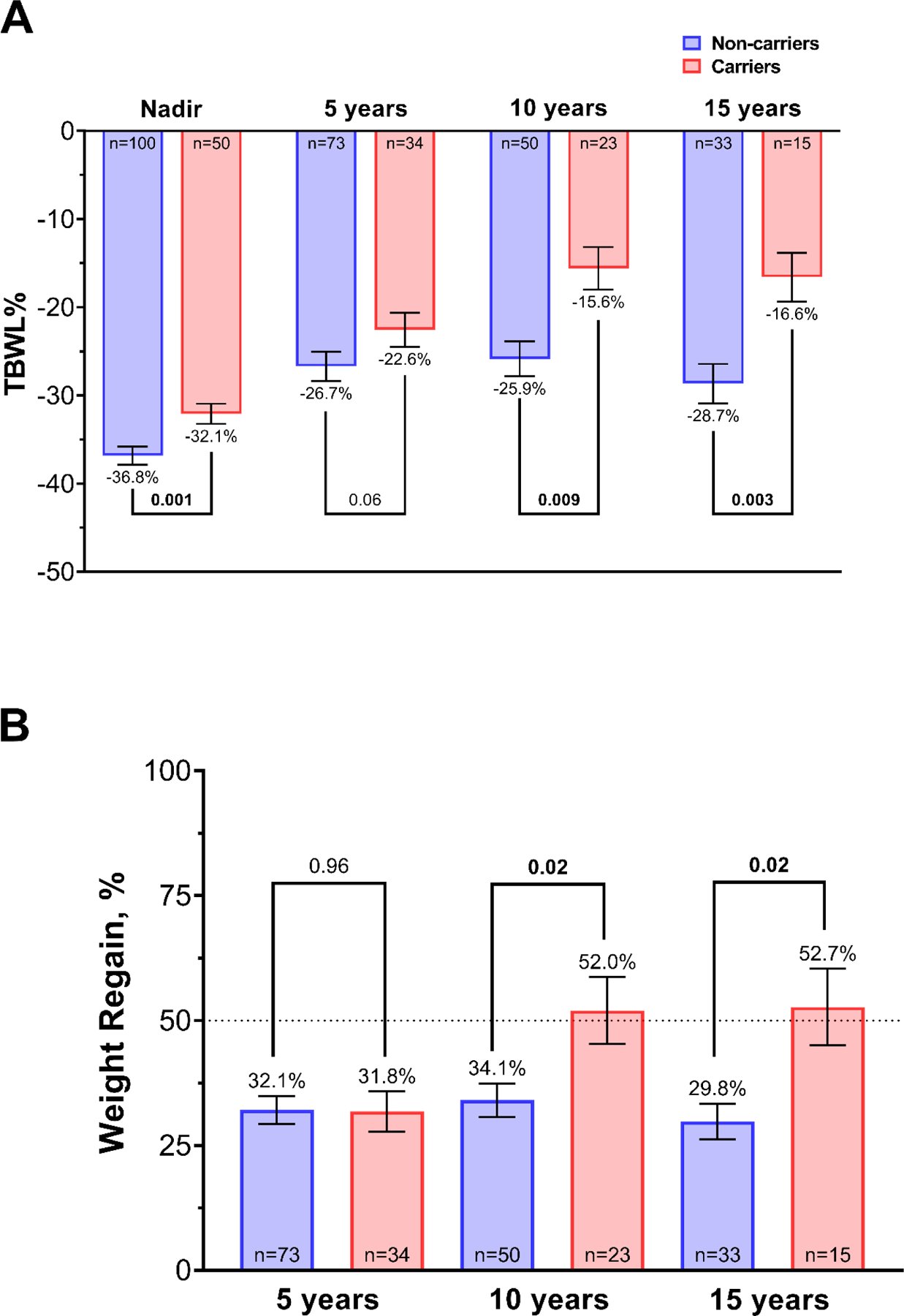

Figure 1 shows weight change in %TBWL by time point between carriers and non-carriers. Weight loss was similar between carriers and non-carriers during the first six months of follow-up. We used multiple linear regression to adjust the %TBWL for sex, age, BMI, diabetes, and years since surgery. Having a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway was associated with lower weight loss at 10 years (β [95% CI] = −4.2 [−7.3 to −1.1], p=0.009), and 15 years (β [95% CI] = −5.9 [−9.7 to −2.1], p=0.003) (Figure 2A and Table 3). There were no differences in the matching variables and diabetes status between carriers and non-carriers from the 15-year time point analysis (Table 3 in Supplement).

Figure 1.

Total body weight loss percentage (%TBWL) change during 15 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) between carriers and non-carriers. Change in %TBWL. Graph represents mean (SEM) at each time point. a: Weight record at the indicated time point, b: Number of patients with enough years of follow-up based on the year of surgery.

Figure 2.

Total body weight loss percentage (%TBWL) nadir, and at 5, 10, and 15 years (A) and percentage of weight regain after maximum weight loss at 5, 10, and 15 years (B) between carriers and non-carriers. Weight regain was calculated with the formula for percentage of weight regain after maximum weight lost: [100*(weight at 5,10, or 15 years – nadir weight)]/(baseline weight – nadir weight)36. Values are presented as mean (SEM). p value presented is adjusted for age, sex, BMI, diabetes, and years since surgery.

Table 3.

%TBWL and weight regain in carriers and non-carriers. Variables are expressed as mean (SD).

| Carriers | Non-carriers | Difference (95% Confidence Interval) | β coefficient (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

%TBWL

| |||||

| Nadir, % | −32.1 (8.1) | −36.9 (10.4) | 4.8 (1.8 – 7.8) | −2.5 (−4 – −1) | 0.001 |

| 5 years, % | −22.6 (11.3) | −26.7 (14.3) | 4.1 (−1 – 9.2) | −2.3 (−4.7 – 0.1) | 0.06 |

| 10 years, % | −15.6 (11.6) | −25.9 (14) | 10.3 (4 – 16.5) | −4.2 (−7.3 – −1.1) | 0.009 |

| 15 years, % | −16.6 (10.7) | −28.7 (12.9) | 12.1 (4.8 – 19.3) | −5.9 (−9.7 – −2.1) | 0.003 |

|

Weight Regain | |||||

| 5 years, % | 31.8 (23.5) | 32.1 (23.8) | −0.3 (−10.1 – 9.5) | −0.12 (−4.8 – 4.6) | 0.96 |

| 10 years, % | 52 (32.2) | 34.1 (23.7) | 17.9 (2.7 – 33.2) | −8 (−14.9 – −1.2) | 0.02 |

| 15 years, % | 52.7 (29.7) | 29.8 (20.7) | 22.9 (5.3 – 40.5) | −9.7 (−17.7 – −1.7) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations used: %TBWL, total body weight loss percentage.

adjusted for sex, age, BMI, diabetes, and years since surgery

Weight Nadir and Percentage of Weight Regain After Maximum Weight Loss

The mean %TBWL nadir was lower in carriers with −32.1±8.1 compared with −36.8±10.4 in non-carriers (mean diff. 4.8%, 95% CI 1.8 to 7.8) and after adjusting for sex, age, BMI, diabetes, and years since surgery, having a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway was associated with lower nadir %TBWL (β (95% CI) = −2.5 (−4 to −1), p=0.001) (Figure 2A). The percentage of weight regain after maximum weight loss is presented in Figure 2B. Weight regain was markedly higher in carriers with 52±32.2% compared with 34.1±23.7% in non-carriers at 10 years (mean diff. 17.9%; 95% CI, 2.7 – 33.2), and 52.7±29.7% in carriers compared with 29.8±20.7% in non-carriers at 15 years (mean diff. 22.9%, 95% CI 5.3 – 40.5) (Figure 2B). After adjusting for sex, age, BMI, diabetes, and years since surgery, having a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway was associated with higher weight regain at 10 (β (95% CI) = −8 (−14.9 to −1.2), p=0.02) and 15 years (β (95% CI) = −9.7 (−17.7 to −1.7), p=0.02) (Table 3).

Discussion

The long-term results of this study demonstrate that patients with a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway have a lower weight loss and a higher weight regain after RYGB. This is the first study to assess 15-year outcomes after RYGB, including multiple (seven) genes in the leptin-melanocortin pathway and focusing on heterozygous carriers. Furthermore, this study is the first to document RYGB outcomes in patients with heterozygous variants in SH2B1 and SRC1.

To date, only 18 studies have investigated the outcomes after bariatric surgery in patients with variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway12–28. The previous short- and mid-term results of these studies have been widely variable. Only 8 studies have focused on heterozygous carriers 14,19–22,24,26,37, several others assessed more than one type of bariatric surgery 12,14,17,18,20,23,25,28,37, and the majority studied a small number of carriers 12–16,18,21,22,27,28. Also, only four studies have investigated other less prevalent genes from the leptin melanocortin-pathway 20,21,23,28. Here we report that almost nine percent of the patients who underwent RYGB were carriers of a heterozygous variant in the leptin-melanocortin pathway.

In recent years, studies have demonstrated that heterozygous variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway are associated with increased BMI in a similar degree to that of homozygotes32,33, highlighting the importance of studying heterozygous carriers. Cooiman et. al. recently demonstrated that carriers of heterozygous MC4R variants showed a trend towards weight regain in the 6-year follow-up after RYGB37. Our study complements these results by assessing heterozygous variants in other important genes in the pathway in many carriers with longer follow-up.

Our results showed that weight loss was virtually identical between carriers and non-carriers during the first six months of follow-up, however, weight loss nadir was significantly lower in carriers. This observation might imply that when the leptin-melanocortin pathway is impaired, the immediate neurohormonal alterations after RYGB can effectively induce weight loss but with a limited nadir. In the mid-term, both carriers and non-carriers displayed a gradual and significant weight regain trend after reaching nadir which was more pronounced in carriers. This weight regain trend persisted in the long-term only in carriers and became significantly different compared with non-carriers. These observations highlight the role of the leptin-melanocortin pathway in long-term weight maintenance after RYGB. Identifying these patients early after experiencing a significant weight regain is essential to implement alternative strategies through a multidisciplinary and individualized approach to preserve the health and metabolic effects of RYGB-induced weight loss 38,39. Moreover, leptin-melanocortin pathway variants may constitute one of the many mechanisms underlying the inter-individual variability in weight loss outcomes after RYGB 40–42.

The mechanisms underlying the effective short-term weight loss and the significant long-term weight regain in patients with leptin-melanocortin pathway variants are still unknown. One possible mechanism could be that the sudden and vigorous change in gut and adipose tissue hormones immediately after RYGB, might be strong enough to signal through an impaired leptin-melanocortin pathway, producing an effective short-term weight loss43. However, in the mid- and long-term, the impaired ligands and receptors in the pathway may cease to respond to the post-RYGB hormonal adaptations, leading to a progressive and substantial weight regain44,45. Further studies are needed to elucidate and characterize the mechanisms causing weight regain after RYGB.

This study has several strengths including matching for factors that influence weight loss outcomes, excluding patients with weight change confounders, the long-term follow-up, the multiple genes included, and focusing only on heterozygotes and RYGB surgery. However, this study is limited by the observational and retrospective study design, and the predominance of females and self-reported Caucasians. Additionally, these results need to be further studied in homozygous carriers to assess the effect of zygosity.

Conclusions

In summary, heterozygous variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway seem to play an important role in long-term weight maintenance after RYGB. Carriers experienced a gradual and significant weight regain in the mid- and long-term after RYGB despite having an initial effective weight loss. Identifying carriers of heterozygous—and homozygous—variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway before surgery might enhance postoperative results through a closer and more individualized follow-up. On the other hand, identifying carriers—who were not screened before surgery—in the events of sub-optimal short-term weight loss and/or significant mid- or long-term weight regain might help implement multidisciplinary and individualized interventions that consider that the leptin-melanocortin pathway might be impaired or less functional in these individuals. Further studies are needed to determine if carriers of a specific gene benefit from a specific bariatric intervention or through modifications to current surgical techniques of a bariatric procedure (e.g., limb length and/or pouch size in RYGB). Moreover, there is an imperative need to explore the effects of combination therapy (bariatric surgery with antiobesity medications) in patients with genetic variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway and other obesity related genes.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

RYGB resulted in effective short-term weight loss in both patients with and without a heterozygous leptin-melanocortin pathway variant.

Only patients with a heterozygous leptin-melanocortin pathway variant experienced a gradual and significant weight regain in the mid-term that extended to the long-term (15 years).

Patients could benefit from genotyping studies as a preoperative workup or in the event of significant weight regain to implement individualized weight management strategies.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the participants from the Mayo Clinic Biobank and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals for the genotyping studies.

Funding:

Dr. Acosta is supported by NIH (NIH K23-DK114460). The study was supported by The Mayo Clinic Biobank, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine. Genotyping studies were provided by Rhythm Pharmaceuticals

This study was funded by the NIH (NIH K23-DK114460) and The Mayo Clinic Biobank, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine.

Funding Sources:

The funding sources were not involved in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Abbreviations:

- ARC

arcuate nucleus

- POMC

pro-opiomelanocortin

- LEPR

leptin receptor

- SRC1

steroid coreceptor activator-1

- SH2B1

Src homology 2 B adaptor protein 1

- PCSK1

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1

- αMSH

alpha-melanocyte stimulant hormone

- MC4R

melanocortin receptor 4

- SIM1

single-minded 1

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- RYGB

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- SG

gastrectomy

- AGB

adjustable gastric banding

- EMR

electronic medical record

- IRB

institutional review board

- BMI

body-mass index

- gnomAD

Genome Aggregation Database

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics

- HGVS

Human Genome Variation Society

- %TBWL

percentage of total body weight loss

- SD

standard deviation

- IQR

interquartile range

- CI

confidence interval

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- CADD

combined annotation dependent depletion

- BED

binge eating disorder

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Acosta is a stockholder in Gila Therapeutics and Phenomix Sciences; he served as a consultant for Rhythm Pharmaceuticals and General Mills. Dr. Camilleri is a stockholder in Phenomix Sciences and Enterin and serves as a consultant to Takeda, Kallyope, Ironwood with compensation to his employer, Mayo Clinic.

Disclosure: Author 16 is a stockholder in Company 1 and Company 2; he served as a consultant for Company 3 and Company 4. Author 12 is a stockholder in Company 2 and Company 5 and serves as a consultant to Company 6, 7, and 8 with compensation to his employer. The rest of the authors have no conflict of interest.

Clinical trial registration: None

Data Sharing and Transparency: Data collected for the study, including individual deidentified participant data, will be available to interested parties after the signing of a data access agreement. Data may be requested by contacting Andres Acosta M.D, Ph.D., at Acosta.Andres@mayo.edu.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and all participants provided prior written authorization for research use of their medical records and biological samples, including their use for genotyping studies.

Ethical Approval

“All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.”

References

- 1.Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;376(3):254–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;377(1):13–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Courbage S, Poitou C, Le Beyec-Le Bihan J, et al. Implication of Heterozygous Variants in Genes of the Leptin–Melanocortin Pathway in Severe Obesity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021;106(10):2991–3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. Mutations in ligands and receptors of the leptin–melanocortin pathway that lead to obesity. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism 2008;4(10):569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeo GS, Heisler LK. Unraveling the brain regulation of appetite: lessons from genetics. Nature neuroscience 2012;15(10):1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Progress in pharmacotherapy for obesity. Jama 2021;326(2):129–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markham A Setmelanotide: First approval. Drugs 2021:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlsson LM, Sjöholm K, Jacobson P, et al. Life expectancy after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;383(16):1535–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. New England journal of medicine 2007;357(8):741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning S, Pucci A, Batterham RL. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: effects on feeding behavior and underlying mechanisms. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2015;125(3):939–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vos N, Oussaada SM, Cooiman MI, et al. Bariatric Surgery for Monogenic Non-syndromic and Syndromic Obesity Disorders. Current Diabetes Reports 2020;20(9):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunziata A, Funcke J-B, Borck G, et al. Functional and phenotypic characteristics of human leptin receptor mutations. Journal of the Endocrine Society 2019;3(1):27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Beyec J, Cugnet-Anceau C, Pépin D, et al. Homozygous leptin receptor mutation due to uniparental disomy of chromosome 1: response to bariatric surgery. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013;98(2):E397–E402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Censani M, Conroy R, Deng L, et al. Weight loss after bariatric surgery in morbidly obese adolescents with MC4R mutations. Obesity 2014;22(1):225–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelin EB, Daggag H, Speer AL, et al. Melanocortin-4 receptor signaling is not required for short-term weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy in pediatric patients. International Journal of Obesity 2016;40(3):550–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aslan IR, Ranadive SA, Ersoy BA, Rogers SJ, Lustig RH, Vaisse C. Bariatric surgery in a patient with complete MC4R deficiency. International Journal of Obesity 2011;35(3):457–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valette M, Poitou C, Le Beyec J, Bouillot J-L, Clement K, Czernichow S. Melanocortin-4 Receptor Mutations and Polymorphisms Do Not Affect Weight Loss after Bariatric Surgery. PLOS ONE 2012;7(11):e48221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aslan IR, Campos GM, Calton MA, Evans DS, Merriman RB, Vaisse C. Weight Loss after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass in Obese Patients Heterozygous for MC4R Mutations. Obesity Surgery 2011;21(7):930–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirshahi UL, Still CD, Masker KK, Gerhard GS, Carey DJ, Mirshahi T. The MC4R(I251L) Allele Is Associated with Better Metabolic Status and More Weight Loss after Gastric Bypass Surgery. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2011;96(12):E2088–E2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potoczna N, Branson R, Kral JG, et al. Gene variants and binge eating as predictors of comorbidity and outcome of treatment in severe obesity. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery 2004;8(8):971–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Zhang H, Tu Y, et al. Monogenic Obesity Mutations Lead to Less Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery: a 6-Year Follow-Up Study. Obesity Surgery 2019;29(4):1169–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkhenini HF, New JP, Syed AA. Five-year outcome of bariatric surgery in a patient with melanocortin-4 receptor mutation. Clinical Obesity 2014;4(2):121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooiman MI, Kleinendorst L, Aarts EO, et al. Genetic Obesity and Bariatric Surgery Outcome in 1014 Patients with Morbid Obesity. Obesity Surgery 2020;30(2):470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore BS, Mirshahi UL, Yost EA, et al. Long-term weight-loss in gastric bypass patients carrying melanocortin 4 receptor variants. PLoS One 2014;9(4):e93629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonnefond A, Keller R, Meyre D, et al. Eating behavior, low-frequency functional mutations in the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) gene, and outcomes of bariatric operations: a 6-year prospective study. Diabetes Care 2016;39(8):1384–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatoum IJ, Stylopoulos N, Vanhoose AM, et al. Melanocortin-4 Receptor Signaling Is Required for Weight Loss after Gastric Bypass Surgery. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2012;97(6):E1023–E1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nizard J, Dommergues M, Clément K. Pregnancy in a woman with a leptin-receptor mutation. New England Journal of Medicine 2012;366(11):1064–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poitou C, Puder L, Dubern B, et al. Long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with biallelic mutations in the POMC, LEPR, and MC4R genes. Surgery for obesity and related diseases 2021;17(8):1449–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pucci A, Batterham RL. Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: similar, yet different. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2019;42(2):117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson JE, Ryu E, Johnson KJ, et al. The Mayo Clinic Biobank: A Building Block for Individualized Medicine. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2013;88(9):952–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Klaauw Agatha A, Farooqi IS. The Hunger Genes: Pathways to Obesity. Cell 2015;161(1):119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courbage S, Poitou C, Beyec-Le Bihan L, et al. Implication of heterozygous variants in genes of the leptin-melanocortin pathway in severe obesity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wade KH, Lam BY, Melvin A, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the melanocortin 4 receptor in a UK birth cohort. Nature Medicine 2021;27(6):1088–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, et al. HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Human mutation 2016;37(6):564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brethauer SA, Kim J, El Chaar M, et al. Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obesity surgery 2015;25(4):587–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.King WC, Hinerman AS, Belle SH, Wahed AS, Courcoulas AP. Comparison of the performance of common measures of weight regain after bariatric surgery for association with clinical outcomes. Jama 2018;320(15):1560–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooiman MI, Alsters SI, Duquesnoy M, et al. Long-Term Weight Outcome After Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Melanocortin-4 Receptor Gene Variants: a Case–Control Study of 105 Patients. Obesity Surgery 2022:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srivastava G, Apovian C. Future pharmacotherapy for obesity: new anti-obesity drugs on the horizon. Current obesity reports 2018;7(2):147–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeo GSH, Chao DHM, Siegert A-M, et al. The melanocortin pathway and energy homeostasis: From discovery to obesity therapy. Molecular Metabolism 2021;48:101206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang WW, Hawkins DN, Brockmeyer JR, Faler BJ, Hoppe SW, Prasad BM. Factors influencing long-term weight loss after bariatric surgery. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 2019;15(3):456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shantavasinkul PC, Omotosho P, Corsino L, Portenier D, Torquati A. Predictors of weight regain in patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 2016;12(9):1640–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benoit SC, Hunter TD, Francis DM, De La Cruz-Munoz N. Use of Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database (BOLD) to Study Variability in Patient Success After Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surgery 2014;24(6):936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandarana K, Gelegen C, Karra E, et al. Diet and Gastrointestinal Bypass–Induced Weight Loss: The Roles of Ghrelin and Peptide YY. Diabetes 2011;60(3):810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akalestou E, Miras AD, Rutter GA, le Roux CW. Mechanisms of weight loss after obesity surgery. Endocrine reviews 2022;43(1):19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hao Z, Münzberg H, Rezai-Zadeh K, et al. Leptin deficient ob/ob mice and diet-induced obese mice responded differently to Roux-en-Y bypass surgery. International Journal of Obesity 2015;39(5):798–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.