Summary

Food intake and energy expenditure are key regulators of body weight. To regulate food intake, the brain must integrate physiological signals and hedonic cues. The brain plays an essential role in modulating the appropriate responses to the continuous update of the body energy-status by the peripheral signals and the neuronal pathways that generate the gut-brain axis. This regulation encompasses various steps involved in food consumption, include satiation, satiety, and hunger. It is important to have a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that regulate food consumption as well as to standardize the vocabulary for the steps involved. This review discusses the current knowledge of the regulation and the contribution peripheral and central signals at each step of the cycle to control appetite. We also highlight how food intake has been measured. The increasingly complex understanding of regulation and action mechanisms intervening in the gut-brain axis offers ambitious targets for new strategies to control appetite.

Keywords: food intake, satiation, satiety, hunger

Introduction

Food intake is highly regulated by internal physiological information and external environmental cues. The hypothalamus and brain stem integrate neural and hormonal signals from the periphery and other brain areas to elicit feeding behaviors.1 However, humans eat not only in response to homeostatic signals but also for other reasons related to psychological and socio-cultural aspects.2 This integration of information determines what, when, and how much we eat.

Obesity is a growing epidemic that affects over 600 million adults worldwide. Obesity contributes to the development of multiple metabolic, mechanical and mental disorders, and it is associated with an overall increased mortality.3 The dominant pathogenesis is the imbalance in the processes involved in energy homeostasis: there is a greater energy intake than energy expenditure that leads to excessive energy storage.4 To better understand the complex mechanisms behind obesity development it is important to first recognize the physiologic processes involved in the shift from a fasting state to a food-seeking and consumption state. This cycle begins when an individual feels hunger and eats until they reach satiation and then fasts for a period known as satiety.5

This review aims to examine the steps of the stages of the food intake cycle; the homeostatic signals on motility, hormones, and neurotransmitters; and their action on the central nervous system. There is no single mechanism involved, it is not unidirectional, and the intervening steps need to be studied thoroughly.

Food intake cycle stages

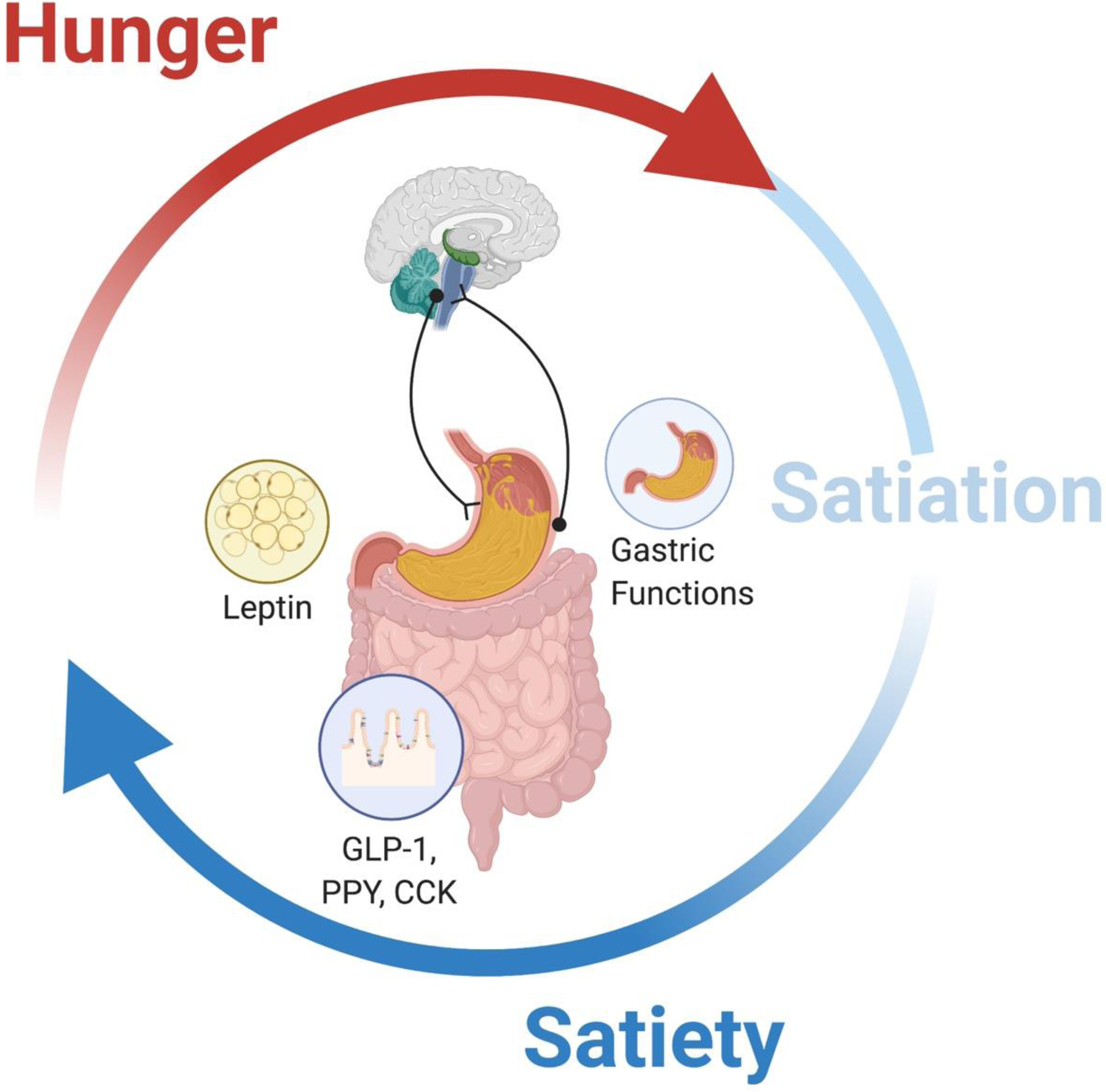

In humans, food intake is an essential function that is coordinated by the gastrointestinal, endocrine and nervous systems to maintain energy homeostasis.6 The food intake cycle stages are hunger, satiation and satiety.7 Hunger is the desire to eat and it is described as an uncomfortable emptiness in the abdomen.8 Satiation refers to the sensation of fullness that results in meal termination. Satiety is the term given to the postprandial events that determine the timing for the next meal.1 Although these terms imply that food intake regulation is a step-by-step system, this is not true. There is an inter meal period, not defined, in which neither fullness nor hunger is dominating. In a homeostatic regulation, meal initiation results from satiety fading and hunger increasing during the postprandial period or from prolonged fasting (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Food intake cycle. Satiation determines meal termination, while satiety fading and hunger increasing lead to food consumption.

The integration of internal signals (hormonal, neuronal and metabolic) and external cues (behavioral and cognitive) regulated the food intake cycle.9 This integration of information dictates what, when and how much we eat. However, the precise moment that establishes the change from one stage to the next one has yet to be determined.

Satiation

Satiation is the process that controls the meal size and leads to meal termination.10 It has been characterized as a postprandial feeling of fullness or even symptoms like nausea and bloating. Satiation is quantified by the calories consumed before reaching a usual level of fullness.11,12

Satiation relies on volume-dependent signals from the gastrointestinal tract and neuroendocrine effectors released from the interaction between the gut epithelium and nutrients. Altogether, this chain of events turns on the appetite inhibition neuron system in the brainstem and hypothalamus13 (see Fig 2). The cognitive information from the socio-cultural and aspects of eating can modulate these mechanical and neuroendocrine gastrointestinal signals. This modulation is referred as to hedonic regulation of eating.

Figure 2.

Peripheral signals for satiation. Gastric accommodation keeps a normal stretch perception until mechanoreceptors perceive gastric distention, and the vagus nerve transmits the signal to the nucleus of the solitary tract. Cholecystokinin also reaches the central nervous system by circulation.

Gastrointestinal motility

Gastrointestinal motility controls the transit of food through the stomach and intestine. This process is essential for food digestion and for food intake regulation. After food ingestion, nutrients fill the stomach and expand its volume up to 15 times before increasing the intragastric pressure. This is the result of gastric accommodation.

Gastric accommodation

In 1922, Walter Cannon described gastric accommodation in humans as the sensation of fullness felt after inflating an intragastric balloon.14 Gastric accommodation is the result of the gastric wall relaxation, and it correlates with the postprandial increase in gastric volume. Gastric accommodation is important in satiation because it keeps intragastric pressure low.15 Once gastric mechanoreceptors of the stomach sense the stretch, a satiation signal is relayed to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) in the brainstem via the vagus. This satiation signal induces gastric content emptying into the duodenum to decrease the intragastric pressure.

Studies have demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of the gastric accommodation decreases the meal size by 166 kcal, and gastric distention obtained by an inflated balloon reduced food intake by 400 ml.16,17 Additionally, inhibition of vagal functions blocking gastric stretch signals has been shown to decrease food intake by reducing gastric emptying (GE) and inducing early satiation.11 Taken together, these results suggest that the gastric volume load itself is enough to induce satiation, but it is not the only stimulus.

Endocrine regulation

The enteroendocrine cells are specialized hormone-secreting cells in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract’s epithelium from the stomach to the rectum. These cells represent only 1% of the newly formed epithelial cells. Digestive products of macronutrients, sub-products of digestion produced by microbiota and bile acids stimulate enteroendocrine cells. Their stimulation requires either the uptake of nutrients across the apical brush or the activation of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR).18 The main peptide with an established causal association with satiation is cholecystokinin (CCK).

Cholecystokinin

CCK is released from intestinal I-cells in the duodenal and jejunal mucosa in response to fat, protein and to a lesser extent, carbohydrates.19 Plasma levels increase 10 to 15 minutes after oral intake. CCK concentration remains elevated for up to 5 hours. CCK’s action is mediated through the CCK-1 receptor (CCK1R), known as the alimentary receptor.20

Experimentally, on one hand, the use of exogenous CCK has resulted in a reduction in meal size by 21%. This reduction in meal size is the result of an inhibitory effect on GE and increased gastric distention. However, anorectic effects dissipate after only 24 hours of continuous infusion.1,21,22 On the other hand, a CCK receptor blocker has been shown to block the satiating effects of intraduodenal lipid infusion.23

Central regulation

The peripheral signals generated in the gastrointestinal tract converge into vagal nerve afferents that also express GPCRs. Activation of vagal nerve afferents evoke various reflex responses that are relayed to the NTS in the brainstem. NTS neurons release glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), norepinephrine, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and CCK to generate a cascade of molecular signals that project to the lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPBM), the central amygdala, the stria terminalis and the medulla to decrease appetite.24

Measurement of satiation

Satiation is directly correlated with fasting gastric volume and is associated with calorie intake to comfortable fullness. Satiation can therefore be determined by the volume to comfortable fullness and maximum tolerated volume. Objectively, physiologic studies that determine gastric volume and accommodation can be used to measure satiation.25 Other tools to assess satiation include the measurement of food consumption up to fullness under standardized conditions and brain activation by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).2 It is important to note that eating is a sensory experience and therefore, test stimuli, location and palatability of the food can influence the response.

Nutrient drink test and ad libitum buffet meal

The nutrient drink test was developed to study functional dyspepsia. This test measures maximum tolerated volume. It involves the ingestion of a nutrient drink (Ensure 1 kcal/mL) at a constant rate of 30 mL min using a constant-rate perfusion pump. Participants record their sensations at 5-min intervals using a numerical scale from 0 to 5, with level 0 being no symptoms, level 3 corresponding to fullness sensation after a typical meal to address the volume to fullness (VTF), and level 5 corresponding to the maximum tolerated volume (MTV).26 Studies have shown that fasting gastric volume is associated with calorie intake to the point of comfortable fullness or volume to fullness (VTF) as well as the MTV.25

The caloric intake following an ad libitum buffet meal has been used to quantify the energy intake under both free-living and laboratory-controlled conditions. The ad libitum buffet meal with a detailed evaluation of the macronutrient content and total energy composition allows to determine the calories consumed to reach fullness and the effect in post prandial appetite sensation.27 This approach has been used to evaluate energy intake and to assess the effect of different interventions.28–31

Gastric volume and accommodation

Gastric volume and accommodation can be invasively measured using an intragastric barostatically-controlled balloon.32 Gastric accommodation can also be measure by single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). The SPECT provides a non-invasive estimate of a meal’s effect on the total gastric volume and has been validated against the barostatically-controlled balloon. The SPECT involves intravenously administration of 99mTc pertechnetate and the recording of images after 4 hours of fasting and after ingestion of 300 ml of a test meal.33 Gastric volume is measured by imaging reconstruction. The volume changes between the two stages allow us to calculate gastric accommodation.12

Functional MRI

fMRI is a neuroimaging technique that can interpret neural activity through changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) in specific regions of interest (ROI) using techniques like blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) or artery spin labeling (ASL).34,35 Brain activation increases blood flow, which leads to a decreased concentration of deoxygenated hemoglobin creating a signal that can be picked up by the MRI machine. These signals can then be correlated to the effects of satiation in the brain. Images can be acquired as fast as 64 images per second, making it suitable for assessing a single time point.36

Satiety

Satiety is the period after reaching satiation. During this period of time eating behavior is inhibited.7 It will end as food digestion continues, absorptive signals disappear, and the next feeding period begins. As seen with satiation, satiety is regulated by physiological stimulus (i.e., mechanical stimulation and neuroendocrine signals) and psychological patterns of behavior (see Fig 3).

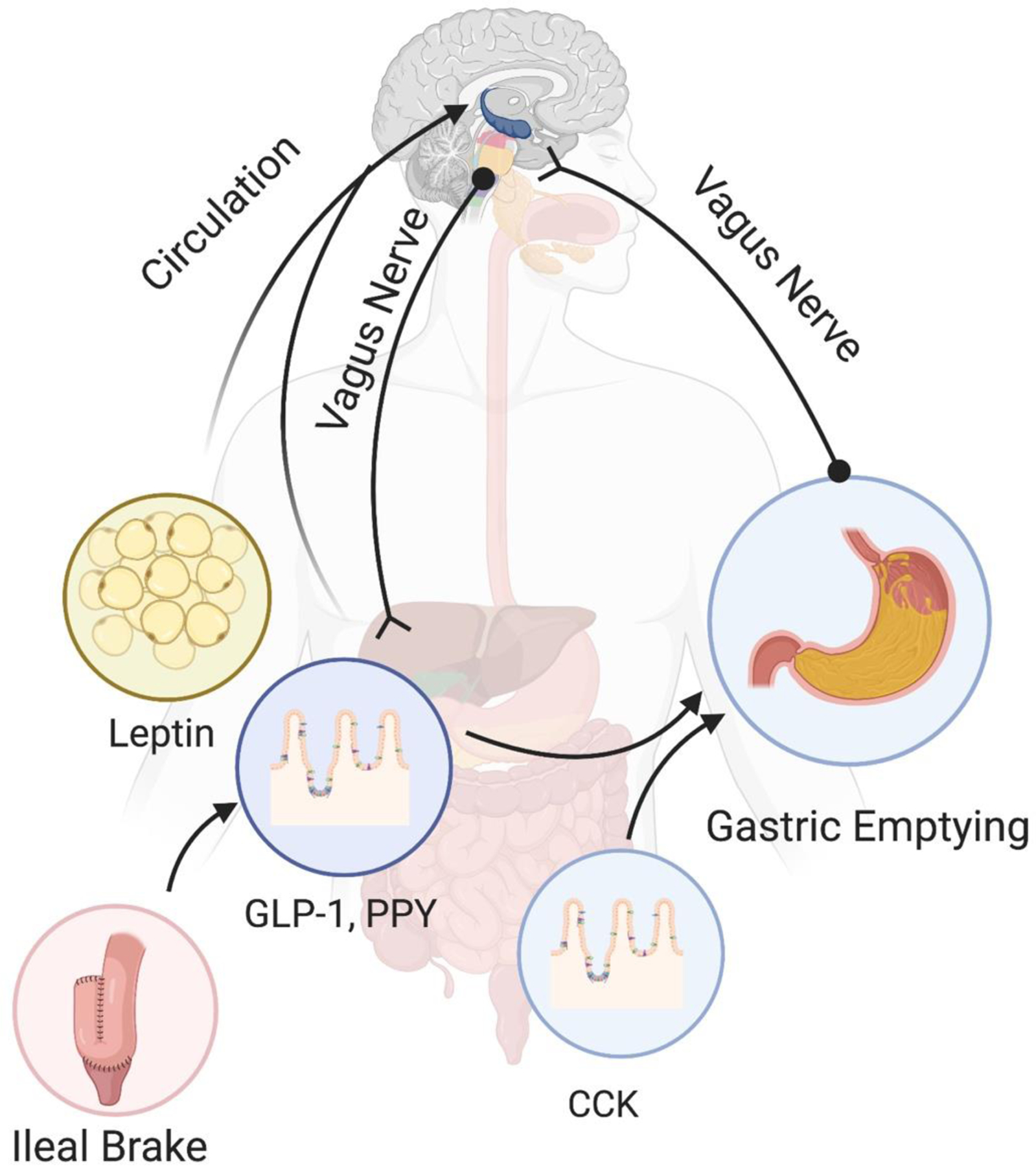

Figure 3.

Peripheral signals for satiety. The vagus nerve regulates gastric emptying through the inhibitory and excitatory vagal circuits. CCK and GLP-1 modulate GE as well by the process known as the ileal brake. Leptin, PYY, and GLP-1 regulate the central activation by endocrine regulation and stimulation through the vagus nerve.

Gastrointestinal motility

During the filling phase of the stomach, gastric accommodation keeps gastric pressure low and inhibits peristaltic movements. When gastric distention reaches a critical stretch level, slow tonic contractions of the fundus and peristaltic contractions in the rest of the stomach start. Once the antrum fills up to a certain level, the pylorus relaxes and propels the food into the duodenum. Motility studies refer to this period as the lag phase for the stomach-emptying curve.37

Gastric emptying

Gastric emptying determines the rate of appearance of nutrients in the small intestine to regulate satiety. GE rate is a measurement of the speed of delivery of gastric contents into the duodenum. The volume, osmolality and caloric density of the gastric content control the average GE rate with feedback from the rest of the GI tract by paracrine and nervous signals.38

The physical and chemical signals rely on hormonal and mechano-sensing receptors that communicate through the vagal circuit. The vagus nerve exerts both, inhibitory and excitatory effects on the stomach via the gastric inhibitory vagal motor circuit and the gastric excitatory vagal circuit.37 Among gastrointestinal hormones, CCK, GLP-1, and leptin slow GE. Other proglucagon-derived peptides (i.e., glucagon-like peptide-2, oxyntomodulin, glucagon, and GIP) have been related to gastrointestinal motility but affect GE in a lesser degree than GLP-1.39 CCK and GLP-1 directly stimulate the inhibitory circuit, while leptin induces a slow modulation by the delayed activation of CCK1 receptors. Endogenous peptide YY (PYY) was related with a slower rate of gastric emptying; however, exogenous PYY3–36 reduced food intake without changing gastric emptying.40

Ileal brake

The entry of nutrients, mostly fat and proteins, into the distal small intestine, induces a feedback response in the proximal GI tract to control motility and secretion. This mechanism is known as the ileal brake. Read et al. demonstrated that infusion of nutrients in the ileum decreases the frequency of antral and duodenal peristaltic contractions while the infusion of nutrients in the colon did not affect small bowel transit.41 The ileal break is the result of the activation of enteroendocrine cells and the mucosal afferent nerves. GLP-1 and CCK from the proximal gut, and PYY from the distal gut regulate this system. The intensity of the inhibitory signals is proportional to the GE rate, the caloric load and the composition of the food.42

Endocrine regulation

Gastrointestinal hormones play a role in the endocrine regulation of satiety. Leptin, PYY and GLP-1 are among the most important endocrine regulators.

Leptin

Leptin is a hormone released by the adipose tissue and the enterocytes. Leptin has a critical role in conserving fat mass for survival and reproduction. Leptin concentration positively correlates with total body fat stores and its levels fall during starvation.43 Leptin helps regulate appetite and food intake by promoting satiety when there is a positive energy balance.44

Leptin, as adipocyte-derived hormone, highlights the relation between adipose tissue, gut axis and the homeostatic regulation energy balance and body weight withing the hypothalamus in addition to a peripherical action on vagal cholinergic receptors.45,46 The significance of this adipose-brain relationship is demonstrated when leptin reduces ghrelin’s orexigenic action in the hypothalamus.47 While the adipose-gut relationship was confirmed in animal experiments, both intraperitoneal and intracerebral injection of leptin reduced gastric emptying rate, contributing to satiety.48,49

Patients with leptin deficiency show average birth weight but rapidly gain weight in the first few months of life due to hyperphagia. Leptin administration in leptin-deficient patients results in normalization of hyperphagia, reduced hunger scores and reduced energy intake up to 84%.50 Exogenous treatment with leptin to supra-physiologic concentrations is ineffective in preventing weight gain. Therefore, leptin is sufficient to restore fat stores when they are low but its effect on resisting obesity is weak.44

Peptide YY

PYY is a hormone secreted by enteroendocrine L-cells of the ileum and colon in response to nutrients, mainly fat. Other stimulants include intraluminal bile acids, gastric acid and CCK.23 These cells release inactive PYY1–36. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) rapidly cleaves it into the active form PYY3–36. Plasma levels increase within 15 minutes of food intake, peak at around 60 minutes and remain elevated for up to 6 hours. PYY participates in satiety control as it is the natural signal for the fat-induced ileal brake and acts directly in the central nervous system (CNS) by activating adjacent proopiomelanocortin neurons (POMC).51

PYY3–36 postprandial release promotes satiety through effects on appetite areas in the hypothalamus and brainstem. Supporting the role of PYY on food regulation, studies have shown that (1) fasting PYY concentrations inversely correlate to BMI; (2) diseases characterized by decreased food intake such as inflammatory bowel disease, cardiac cachexia and tropical sprue are associated high levels of PYY3–36 52; and (3) the infusion of PYY3–36 at physiologic postprandial concentrations decrease food intake by 33% over a 24 hour period and result in low ghrelin levels. 53

Glucagon-like-peptide 1

Glucagon-like-peptide 1 is synthesized as pre-pro-glucagon in the L-cells of the ileum and colon, and in the pancreas and by brain pre-pro-glucagon (PPG) neurons within the CNS. It undergoes differential cleavage by pro-hormone convertases 1 and 2, resulting in tissue-specific product.23 GLP-1 is released in response to intestinal luminal nutrients and/or bile acids and in response to submucosal neural stimulation mediated by voltage-gated Ca+2 channels. Concentrations are at their lowest levels after an overnight fast and increase upon meal ingestion in a biphasic pattern. The first peak is 10 to 15 minutes after food intake, followed by a second peak at 30 to 60 minutes.54

GLP-1 has both peripheral and central activation in the gut–brain satiation circuit. The peripheral action of GLP-1 on gastric motor functions can improve postprandial stomach capacity and impact satiety by delaying gastric emptying.55 These activities of the periphery on the gastrointestinal system are mediated through vagal pathways and nitrergic myenteric neurons.56 GLP-1-mediated central regulation of homeostatic food intake, on the other hand, is dependent on the signaling in the hypothalamus and hindbrain.57,58

The effects of GLP-1 on satiety are well stablished and has led to the development of anti-obesity drugs. Studies have shown that GLP-1 infusion at supraphysiological doses in obese and not obese adults induce a reduction in calorie intake by 12%.59 Furthermore, the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists results in delayed GE and progressive and lasting weight loss.60–62

Central regulation

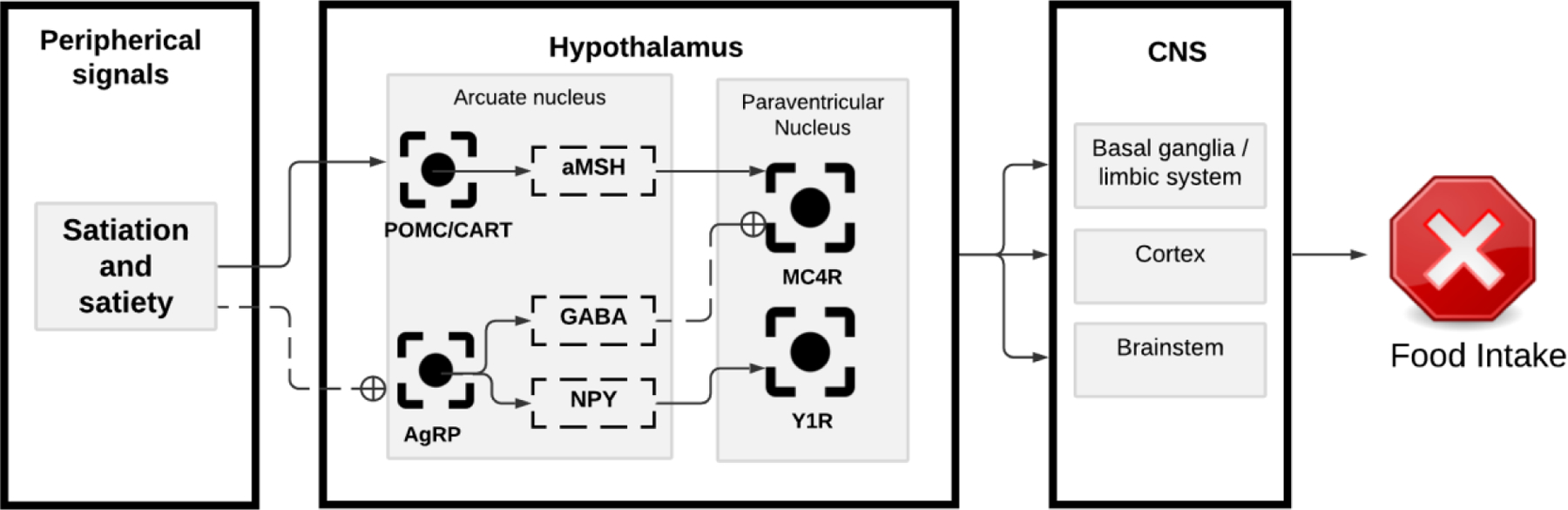

The hypothalamus receives neuronal and endocrine inputs from the GI tract, integrates the information, and translates this information into a feeding behavior. The gut-brain axis is on a continuous feeding mode and needs to be suppressed to limit the meal size. The food intake inhibitory neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus are the pro-opiomelanocortin and the cocaine- and amphetamine-related transcript neurons (POMC/CART). These neurons are activated in response to energy surplus and inhibit food intake. In the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, POMC is cleaved into adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH), β-lipotropic hormone (β-LPH), and N-POMC, however, in the hypothalamus, ACTH and β-LPH are further cleaved to yield α and β melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH, β-MSH), respectively. α-MSH targets melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R) downstream to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH).63

MC4R is a G-protein-coupled receptor widely expressed in the CNS, mainly in the PVH. The principal target of POMC derivatives is the MC4R placed in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN. The deletion of these receptors results in hyperphagia, and its selective expression in the PVN normalizes feeding.64,65 The PVN sends glutamatergic signals to several locations, including the LPBN in the brainstem.13 When activated, the LPBN promotes satiety. Over time, this activation results in a negative feedback and eventually inhibits PVN neurons, silencing the circuit of PVN to LPBN and resulting in food consumption 66 (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Central regulation of food intake. Satiation and satiety signals originated in the periphery stimulate the pro-opiomelanocortin and the cocaine- and amphetamine-related transcript (POMC/CART) neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. These neurons release aMSH, which activates the melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R) in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). The PVN relays the signal to the brainstem, cortex and basal ganglia to stop food intake. Satiation and satiety also inhibit the Agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. The activation of AgRP neurons results in GABA and neuropeptide Y (NPY) release. The release of GABA and NPY inhibit the MC4R, resulting in meal initiation.

Measurement of satiety

Satiety captures the intensity and duration of fullness after reaching satiation. Experimentally, satiety can be measured after a meal by tracking (1) the temporal changes in the subjective feeling of hunger and fullness, and (2) the duration of the fasting period between meals.

Visual analog scales

Appetite-related self-reports include a range of measures over a given period to capture subjective feelings of hunger and fullness. These subjective feelings are usually measured on 100- or 150-mm visual analog scales (VAS). VAS have a good reliability at a group level. These scales are completed before and after consumption of a test meal, and then at regular time intervals of 15, 30 or 60 minutes for 3–5 hours, or the start of the next meal.36 VAS are widely used for their ease of application, understanding, and analysis. VAS have been used to predict the timing but not the number of calories for a subsequent meal.67

Satiety is a function of time. Therefore, VAS data analysis should not be based on a single time point but on repeated measures or the area under the curve (AUC). Several novel parameters, derived from the meal energy content and appetite sensations, have been established. For instance, the “satiating power” of a meal is obtained by dividing the total AUC for the fullness sensation by the energy (kcal) consumed.2 The “satiety quotient” correlates the meal energy content and the change in appetite sensations. The equation is the variation of appetite sensation divided by the energy intake in an eating episode (appetite sensation pre-meal – appetite sensation post-meal/ energy intake).68 The “satiety ratio” can be derived as the ratio between meal size (kcal) and the latency to the onset of the next meal (time).69 However, all these multiple approaches lack ecological validity and inter-personal reproducibility.

Gastric emptying

Scintigraphy is the gold standard to measure GE. The standard procedure comprises the ingestion of a meal with a standardized caloric content and radiolabeled with 99mTc. A gamma camera obtains images immediately after meal ingestion and at a minimum of 1, 2 and 4 hours after meal ingestion. The results report the percent of food remaining in the stomach at each point.70 Furthermore, gastric emptying has been linked to subsequent meal intake, making it an objective marker of postprandial satiety. GE delay is associated with a lower caloric intake or greater satiety.12 And, rapid gastric emptying is associated with increased appetite hunger.71

Neuroimaging

Satiety can also be evaluated with functional neuroimaging techniques. PET is the preferred modality, and it is used to correlate sensory-specific sensations that lead to increased neuronal activity. PET imaging detects increased signals as a result of higher blood flow and greater tracer uptake in activated brain areas.34 These studies are based on the premise of sensory-specific triggers that can activate neuronal pathways and translate into behaviors.72

Hunger

Hunger represents the sensation of requiring food. Hunger triggers the motivation to seek and initiate food consumption. Individuals correlate hunger to physical experiences such as a dull ache or gnawing phenomena coming from the abdomen and metabolic signals that give rise to a feeling of light-headedness, weakness or emptiness.10,41

Gastrointestinal motility

The stomach and small intestine adopt a cyclic pattern of motility and secretion during fasting called the migrating motor complex (MMC). The MMC is a cycle of a relatively long period of near-quiescence (phase I), followed by non-propulsive contractions at irregular frequency (phase II), and then a short burst of high-amplitude propulsive contractions (phase III) that promotes GE of indigestible food residues.73 Phase III contractions play a “housekeeping” role before the next meal, contributing to the development of sensations associated with hunger.74 In sum, this increases GE and alleviates the sense of fullness caused by gastric distention.75

Endocrine regulation

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is produced by X/A-like cells in the gastric oxyntic mucosa and the small intestine. These cells express the G-protein-coupled receptors T1R1+T1R3 and T2R. Upon activation by nutrients, these receptors suppress ghrelin’s release. Plasma ghrelin concentrations peak before a meal and decrease postprandially in response to nutrient ingestion. Protein is the primary suppressant.18,74 Enteroendocrine cells secrete ghrelin as non-acyl ghrelin. Non-acyl ghrelin undergoes a unique post-translational acylation by ghrelin O-acyl transferase (GOAT) to become an active molecule.76 Ghrelin acts on the growth hormone secretagogue receptor type 1A to enhance the activity of NPY and AgRP neurons while suppressing the action of POMC neurons.77,78 Additionally, ghrelin is associated with the activation of the mesolimbic reward circuitry. This suggests that ghrelin’s hunger and meal initiation role may extend to reward-driven behaviors, including food desire.79

Ghrelin is the only circulating hormone that, upon systemic and central administration, potently increases adiposity and food intake. Administration of ghrelin stimulates gastric emptying and small bowel transit. Low-dose infusion of ghrelin increases ad libitum energy intake in obese patients, and high-dose ghrelin infusion increases energy intake in non-obese patients.80 Infusion of ghrelin in subjects with decreased appetite due to cancer increased energy intake by 31% at a subsequent buffet meal.81 Surprisingly, the deletion of the ghrelin gene, the gene encoding its receptor, or genetic ablation of ghrelin-secreting endocrine cells, does not affect feeding.24

Central regulation

The brain hunger system on the arcuate nucleus is permanently activated. The neurons driving this center are the AgRP neurons. AgRP neurons release two inhibitory neurotransmitters, GABA, and NPY, which antagonize MC4R actions.13,63 AgRP neurons receive the input signals from ghrelin, leptin and possibly insulin. During fasting, ghrelin and low leptin levels increase excitatory synapses. Mediated by NPY, these neurons inhibit MC4R in the PVN, increasing feeding in minutes. GABAergic inhibitory signals potentiate this effect by gradual neuron stimulation through the AgRP to the PVN circuit.24,82 The enteroendocrine hormones serotonin (5HT), CCK, and PYY can inhibit AgRP neurons, promoting satiety. 5HT and CCK cause a rapid but transient reduction in AgRP neuron activity. At the same time, PYY induces a slower, more sustained response.83

Measurement of hunger

Hunger, appetite, and food cravings are terms used interchangeably. Therefore, the lack of an operational definition causes hunger measurement to be based on subjective scales. The VAS for hunger is the most common standardized method used. Studies however, have found the VAS for hunger only has a significant association with liking and wanting, which are hedonic components of food intake, and not with the homeostatic regulation of food intake or any prospective caloric consumption.36,84

Conclusion

Food intake is a complex physiologic process that can be conceived of as a cycle of hunger, satiation, and satiety that combines homeostatic and hedonic signals to maintain energy homeostasis. The interaction of gastrointestinal and endocrine signals reaching the central nervous system is important for homeostatic control. Objective imaging tests and subjective scales have been used to study and quantify these steps. There are many missing links to help us understand the stepwise change from fasting to a food-seeking stage. However, universalizing the terminology, developing operational definitions, and standardizing the measurements may allow appreciating the whole picture of the process.

Acknowledgments:

Figures were created with BioRender.com

Funding:

Dr. Acosta is supported by NIH (NIH K23-DK114460, C-Sig P30DK84567), ANMS Career Development Award, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine – Gerstner Career Development Award.

Footnotes

Search strategy and selection criteria

The present paper is a narrative review based on publications identified through searches of PubMed with the search terms “satiation”, “satiety”, “appetite”, “hunger”, “food intake”, and “appetite” from 1912 until May 2021. Only papers published in English were reviewed. The final reference list was generated based on originality and relevance to the broad scope of this review.

Declaration of interests

Disclosures: Dr. Acosta is a stockholder in Gila Therapeutics, Phenomix Sciences; he serves as a consultant for Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, General Mills

References

- 1.Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. The Journal of clinical investigation 2007; 117(1): 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blundell J, De Graaf C, Hulshof T, et al. Appetite control: methodological aspects of the evaluation of foods. Obesity reviews 2010; 11(3): 251–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandes JC, Collaborators GO. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. New England Journal of Medicine 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin T, Mercer JG. Hunger and satiety mechanisms and their potential exploitation in the regulation of food intake. Current obesity reports 2016; 5(1): 106–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acosta A, Dayyeh BKA, Port JD, Camilleri M. Recent advances in clinical practice challenges and opportunities in the management of obesity. Gut 2014; 63(4): 687–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strominger JL, Brobeck JR. A mechanism of regulation of food intake. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 1953; 25(5): 383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blundell J, Halford J. Regulation of nutrient supply: the brain and appetite control. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 1994; 53(2): 407–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch KL. Gastric neuromuscular function and neuromuscular disorders. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology/diagnosis/management Philadelphia: Elsevier 2010: 789–815. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strubbe JH, Woods SC. The timing of meals. Psychol Rev 2004; 111(1): 128–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannon WB, Washburn AL. An Explanation of Hunger 1. Obesity research 1912; 1(6): 494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camilleri M Peripheral mechanisms in appetite regulation. Gastroenterology 2015; 148(6): 1219–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halawi H, Camilleri M, Acosta A, et al. Relationship of gastric emptying or accommodation with satiation, satiety, and postprandial symptoms in health. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2017; 313(5): G442–g7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heisler LK, Lam DD. An appetite for life: brain regulation of hunger and satiety. Current opinion in pharmacology 2017; 37: 100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannon WB. The mechanical factors of digestion: Longmans, Green & Company; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuiken SD, Samsom M, Camilleri M, et al. Development of a test to measure gastric accommodation in humans. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 1999; 277(6): G1217–G21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tack J, Demedts I, Meulemans A, Schuurkes J, Janssens J. Role of nitric oxide in the gastric accommodation reflex and in meal induced satiety in humans. Gut 2002; 51(2): 219–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geliebter A Gastric distension and gastric capacity in relation to food intake in humans. Physiology & behavior 1988; 44(4–5): 665–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mace O, Tehan B, Marshall F. Pharmacology and physiology of gastrointestinal enteroendocrine cells. Pharmacology research & perspectives 2015; 3(4): e00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liddle R Goldfine ID, Rosen MS, Taplitz RA, Williams JA. Cholecystokinin bioactivity in human plasma Molecular forms, responses to feeding, and relationship to gallbladder contraction J Clin Invest 1985; 75: 1144–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rehfeld JF. Cholecystokinin. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2004; 18(4): 569–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacIntosh CG, Morley JE, Wishart J, et al. Effect of exogenous cholecystokinin (CCK)-8 on food intake and plasma CCK, leptin, and insulin concentrations in older and young adults: evidence for increased CCK activity as a cause of the anorexia of aging. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2001; 86(12): 5830–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kissileff HR, Carretta JC, Geliebter A, Pi-Sunyer FX. Cholecystokinin and stomach distension combine to reduce food intake in humans. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2003; 285(5): R992–R8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinert RE, Feinle-Bisset C, Asarian L, Horowitz M, Beglinger C, Geary N. Ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1, and PYY (3–36): secretory controls and physiological roles in eating and glycemia in health, obesity, and after RYGB. Physiological reviews 2017; 97(1): 411–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andermann ML, Lowell BB. Toward a wiring diagram understanding of appetite control. Neuron 2017; 95(4): 757–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vijayvargiya P, Chedid V, Wang XJ, et al. Associations of gastric volumes, ingestive behavior, calorie and volume intake, and fullness in obesity. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2020; 319(2): G238–G44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chial HJ, Camilleri C, Delgado-Aros S, et al. A nutrient drink test to assess maximum tolerated volume and postprandial symptoms: effects of gender, body mass index and age in health. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002; 14(3): 249–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt SH, Brand Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E. A satiety index of common foods. European journal of clinical nutrition 1995; 49(9): 675–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wanders AJ, van den Borne JJ, de Graaf C, et al. Effects of dietary fibre on subjective appetite, energy intake and body weight: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obesity reviews 2011; 12(9): 724–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchison AT, Piscitelli D, Horowitz M, et al. Acute load-dependent effects of oral whey protein on gastric emptying, gut hormone release, glycemia, appetite, and energy intake in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr 2015; 102(6): 1574–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horowitz M, Flint A, Jones KL, et al. Effect of the once-daily human GLP-1 analogue liraglutide on appetite, energy intake, energy expenditure and gastric emptying in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2012; 97(2): 258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acosta A, Camilleri M, Shin A, et al. Association of melanocortin 4 receptor gene variation with satiation and gastric emptying in overweight and obese adults. Genes Nutr 2014; 9(2): 384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouras EP, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, et al. SPECT imaging of the stomach: comparison with barostat, and effects of sex, age, body mass index, and fundoplication. Single photon emission computed tomography. Gut 2002; 51(6): 781–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuiken SD, Samsom M, Camilleri M, et al. Development of a test to measure gastric accommodation in humans. Am J Physiol 1999; 277(6): G1217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aine CJ. A conceptual overview and critique of functional neuroimaging techniques in humans: I. MRI/FMRI and PET. Critical reviews in neurobiology 1995; 9(2–3): 229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, Gao J-H, Liu H-L, Fox PT. The temporal response of the brain after eating revealed by functional MRI. Nature 2000; 405(6790): 1058–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flint A, Raben A, Blundell J, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. International journal of obesity 2000; 24(1): 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goyal RK, Guo Y, Mashimo H. Advances in the physiology of gastric emptying. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2019; 31(4): e13546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunt J, Smith J, Jiang C. Effect of meal volume and energy density on the gastric emptying of carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 1985; 89(6): 1326–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagell C, Wettergren A, Pedersen JF, Mortensen D, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide-2 inhibits antral emptying in man, but is not as potent as glucagon-like peptide-1. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 2004; 39(4): 353–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pironi L, Stanghellini V, Miglioli M, et al. Fat-Induced heal brake in humans: a dose-dependent phenomenon correlated to the plasma levels of peptide YY. Gastroenterology 1993; 105(3): 733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Read N Role of gastrointestinal factors in hunger and satiety in man. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 1992; 51(1): 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Graaf C, Blom WA, Smeets PA, Stafleu A, Hendriks HF. Biomarkers of satiation and satiety. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2004; 79(6): 946–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. New England Journal of Medicine 1996; 334(5): 292–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. 20 years of leptin: role of leptin in energy homeostasis in humans. Journal of Endocrinology 2014; 223(1): T83–T96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinto S, Roseberry AG, Liu H, et al. Rapid Rewiring of Arcuate Nucleus Feeding Circuits by Leptin. Science 2004; 304(5667): 110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouret SG, Draper SJ, Simerly RB. Trophic Action of Leptin on Hypothalamic Neurons That Regulate Feeding. Science 2004; 304(5667): 108–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalra SP, Ueno N, Kalra PS. Stimulation of appetite by ghrelin is regulated by leptin restraint: peripheral and central sites of action. The Journal of nutrition 2005; 135(5): 1331–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martínez V, Barrachina M-D, Wang L, Taché Y. Intracerebroventricular leptin inhibits gastric emptying of a solid nutrient meal in rats. Neuroreport 1999; 10(15): 3217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cakir B, Kasimay Ö, Devseren E, Yegen B. Leptin inhibits gastric emptying in rats: role of CCK receptors and vagal afferent fibers. Physiological research 2007; 56(3): 315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. 20 years of leptin: human disorders of leptin action. Journal of Endocrinology 2014; 223(1): T63–T70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy K, Bloom S. Gut hormones in the control of appetite. Experimental physiology 2004; 89(5): 507–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El-Salhy M, Suhr O, Danielsson Å. Peptide YY in gastrointestinal disorders. Peptides 2002; 23(2): 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, et al. Gut hormone PYY 3–36 physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature 2002; 418(6898): 650–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chaudhri O, Small C, Bloom S. Gastrointestinal hormones regulating appetite. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2006; 361(1471): 1187–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams DL, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Evidence that intestinal glucagon-like peptide-1 plays a physiological role in satiety. Endocrinology 2009; 150(4): 1680–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imeryüz Ne, Yeğen BC, Bozkurt A, Coşkun T, Villanueva-Peñacarrillo ML, Ulusoy NB. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits gastric emptying via vagal afferent-mediated central mechanisms. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 1997; 273(4): G920–G7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Müller TD, Finan B, Bloom SR, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Molecular Metabolism 2019; 30: 72–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turton M, O’shea D, Gunn I, et al. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature 1996; 379(6560): 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Degen L, Oesch S, Matzinger D, et al. Effects of a preload on reduction of food intake by GLP-1 in healthy subjects. Digestion 2006; 74(2): 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Halawi H, Khemani D, Eckert D, et al. Effects of liraglutide on weight, satiation, and gastric functions in obesity: a randomised, placebo-controlled pilot trial. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017; 2(12): 890–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. The Journal of clinical investigation 1998; 101(3): 515–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nuffer WA, Trujillo JM. Liraglutide: a new option for the treatment of obesity. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy 2015; 35(10): 926–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hahn TM, Breininger JF, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Coexpression of Agrp and NPY in fasting-activated hypothalamic neurons. Nature neuroscience 1998; 1(4): 271–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shah BP, Vong L, Olson DP, et al. MC4R-expressing glutamatergic neurons in the paraventricular hypothalamus regulate feeding and are synaptically connected to the parabrachial nucleus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014; 111(36): 13193–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huszar D, Lynch CA, Fairchild-Huntress V, et al. Targeted disruption of the melanocortin-4 receptor results in obesity in mice. Cell 1997; 88(1): 131–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garfield AS, Li C, Madara JC, et al. A neural basis for melanocortin-4 receptor–regulated appetite. Nature neuroscience 2015; 18(6): 863–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holt GM, Owen LJ, Till S, et al. Systematic literature review shows that appetite rating does not predict energy intake. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2017; 57(16): 3577–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drapeau V, King N, Hetherington M, Doucet E, Blundell J, Tremblay A. Appetite sensations and satiety quotient: predictors of energy intake and weight loss. Appetite 2007; 48(2): 159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gibbons C, Hopkins M, Beaulieu K, Oustric P, Blundell JE. Issues in measuring and interpreting human appetite (satiety/satiation) and its contribution to obesity. Current obesity reports 2019; 8(2): 77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Journal of nuclear medicine technology 2008; 36(1): 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gonzalez-Izundegui D, Campos A, Calderon G, et al. Association of Gastric Emptying with Postprandial Appetite and Satiety Sensations in Obesity. Obesity 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reiman EM. The application of positron emission tomography to the study of normal and pathologic emotions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Narayanaswami V, Dwoskin LP. Obesity: Current and potential pharmacotherapeutics and targets. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2017; 170: 116–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanger GJ, Hellström PM, Näslund E. The hungry stomach: physiology, disease, and drug development opportunities. Frontiers in pharmacology 2011; 1: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rigaud D, Trostler N, Rozen R, Vallot T, Apfelbaum M. Gastric distension, hunger and energy intake after balloon implantation in severe obesity. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 1995; 19(7): 489–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gutierrez JA, Solenberg PJ, Perkins DR, et al. Ghrelin octanoylation mediated by an orphan lipid transferase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008; 105(17): 6320–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Camina J Cell biology of the ghrelin receptor. Journal of neuroendocrinology 2006; 18(1): 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Müller TD, Nogueiras R, Andermann ML, et al. Ghrelin. Molecular metabolism 2015; 4(6): 437–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Romero-Pico A, Vázquez MJ, González-Touceda D, et al. Hypothalamic κ-opioid receptor modulates the orexigenic effect of ghrelin. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013; 38(7): 1296–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Druce M, Wren A, Park A, et al. Ghrelin increases food intake in obese as well as lean subjects. International journal of obesity 2005; 29(9): 1130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wren A, Seal L, Cohen M, et al. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Chen Y, Lin Y-C, Kuo T-W, Knight ZA. Sensory detection of food rapidly modulates arcuate feeding circuits. Cell 2015; 160(5): 829–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marciani L, Cox E, Pritchard S, et al. Additive effects of gastric volumes and macronutrient composition on the sensation of postprandial fullness in humans. European journal of clinical nutrition 2015; 69(3): 380–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wall KM, Farruggia MC, Perszyk EE, et al. No evidence for an association between obesity and milkshake liking. International Journal of Obesity 2020: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]