Vaccination is the central strategy to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccination-induced antibodies that target the viral spike (S) protein and neutralise SARS-CoV-2 are crucial for protection against infection and disease. However, most vaccines encode for the S protein of the virus that circulated early in the pandemic (eg, the B.1 lineage), and emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants have mutations in the S protein that reduce neutralisation sensitivity. In particular, the omicron variant (B.1.1.529 lineage and sublineages) is highly mutated and efficiently evades antibodies.1, 2, 3 Therefore, bivalent mRNA vaccines have been developed that include the genetic information for S proteins of the B.1 lineage and the currently dominating omicron BA.5 lineage. These vaccines have shown increased immunogenicity and protection in mice,4 but information on potential differences in the effectiveness of monovalent and bivalent vaccine boosters in humans is scarce.5, 6, 7

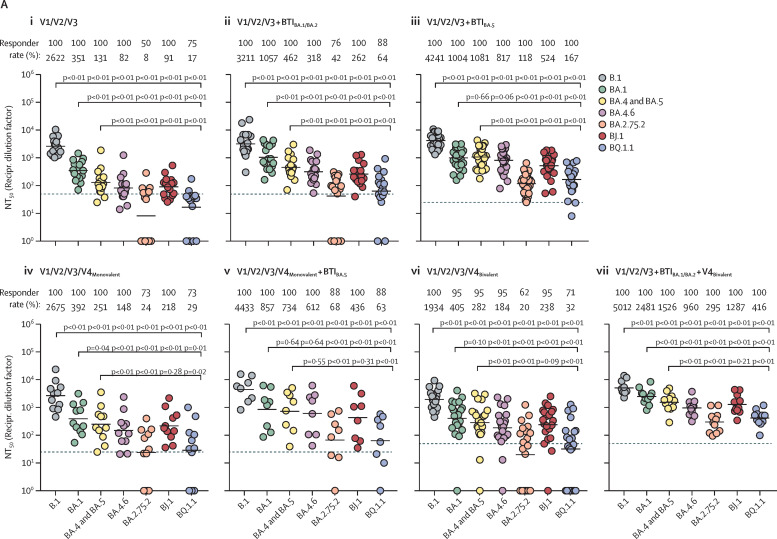

We compared neutralisation of BA.1, BA.4 and BA.5 (identical S proteins, BA.4-5), BA.4.6, and the emerging omicron sublineages BA.2.75.2 (circulating mainly in India), BJ.1 (parental lineage of the currently expanding XBB recombinant), and BQ.1.1 (the incidence of which is increasing in the USA and Europe). We tested neutralisation by antibodies that were induced upon triple vaccination, vaccination and breakthrough infection during the BA.1 and BA.2 wave or BA.5 wave in Germany, triple vaccination plus monovalent or bivalent mRNA booster vaccination, or triple vaccination plus breakthrough infection (BA.1 and BA.2 wave) and a bivalent mRNA booster vaccination. For this, we used S protein bearing pseudotypes, which adequately model antibody-mediated neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2.8 We found that neutralisation of particles pseudotyped with the B.1 S protein (B.1pp) was highest for all cohorts, followed by neutralisation of BA.1pp and BA.4-5pp, which is in line with expectations (figure ; appendix p 17).1, 2 Compared with BA.4-5pp, neutralisation of BA.4.6pp and BJ.1pp was moderately reduced (up to 2·2 times lower), whereas neutralisation of BA.2.75.2pp and BQ.1.1pp was strongly reduced (up to 15·5 times lower; figure; appendix p 8). These results suggest that omicron sublineages BA.2.75.2 and BQ.1.1 possess high potential to evade neutralising antibodies elicited upon diverse immunisation histories. We observed that BA.1 and BA.2 breakthrough infections and BA.5 breakthrough infections in individuals who had been triple vaccinated induced higher omicron sublineage neutralisation (on average 3·7–8·5 times higher compared with triple vaccinated individuals without breakthrough infection) than monovalent or bivalent booster vaccination (on average 1·9–2·2 times higher compared with triple vaccinated individuals without breakthrough infection; appendix p 17). Furthermore, the highest omicron sublineage neutralisation was obtained for individuals who were triple vaccinated and also had a BA.1 or BA.2 breakthrough infection plus a subsequent bivalent booster vaccination (on average 17·6 times higher compared with triple vaccinated individuals without breakthrough infection; appendix p 17). No notable differences were detected between the neutralisation activity induced upon monovalent or bivalent vaccine boosters (on average 2·0 times higher following monovalent vaccination and 2·1 times higher following bivalent vaccination compared with triple vaccinated individuals without breakthrough infection).

Figure.

Omicron sublineage-specific neutralisation activity elicited upon triple vaccination, breakthrough infection, and monovalent or bivalent vaccine boosters.

(A) Neutralising activity in patient plasma. Plasma samples were analysed from individuals who were (i) triple vaccinated (n=16), (ii) triple vaccinated with a BTI during the BA.1 and BA.2 wave in Germany (n=17), (iii) triple vaccinated with a BTI during the BA.5 wave in Germany (n=27), (iv) triple vaccinated that received the monovalent BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech) vaccine booster (n=11), (v) triple vaccinated with a subsequent monovalent BNT162b2 vaccine booster and a BTI during the BA.5 wave in Germany (n=8), (vi) triple vaccinated individuals with a subsequent bivalent BNT162b2 original and omicron BA.4-5 vaccine booster (n=21), (vii) or triple vaccinated with a BTI during the BA.1 and BA.2 wave in Germany and a subsequent bivalent BNT162b2 original and omicron BA.4-5 vaccine booster (n=11). Information on the methods and statistical analysis are reported in the appendix (pp 10–12). (B) Individual analysis of vaccinated cohorts without BTI. Information on the methods and statistical analysis are reported in the appendix (pp 10–12). Dashed lines indicate the lowest plasma dilution tested. Of note, all samples yielding an NT50 value of less than 6·25 (starting dilution of 1:25) or 12·5 (starting dilution of 1:50) were considered negative and were assigned an NT50 value of 1. BTI=breakthrough infection. NT50=neutralising titre 50. Recipr. dilution factor=reciprocal dilution factor. V=vaccination.

Collectively, our results show that the emerging omicron sublineages BQ.1.1 and particularly BA.2.75.2 efficiently evade neutralisation independent of the immunisation history. Although monovalent and bivalent vaccine boosters both induce high neutralising activity and increase neutralisation breadth, BA.2.75.2-specific and BQ.1.1-specific neutralisation activity remained relatively low. This finding is in keeping with the concept of immune imprinting by initial immunisation with vaccines targeting the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 B.1 lineage.9, 10 Furthermore, the observation that neutralisation of BA.2.75.2pp and BQ.1.1pp was most efficient in the cohort that had a breakthrough infection during the BA.1 and BA.2 wave and later received a bivalent booster vaccination, but was still less efficient than neutralisation of B.1pp, implies that affinity maturation of antibodies and two-time stimulation with different omicron antigens might still not be sufficient to overcome immune imprinting. As a consequence, novel vaccination strategies have to be developed to overcome immune imprinting by ancestral SARS-CoV-2 antigen.

AK, IN, SP, and MH have done contract research (testing of vaccinee sera for neutralising activity against SARS-CoV-2) for Valneva unrelated to this work. GMNB served as advisor for Moderna. SP served as advisor for BioNTech, unrelated to this work. All other authors declare no competing interests. MH and GMNB are co-first authors of this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Arora P, Zhang L, Rocha C, et al. Comparable neutralisation evasion of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:766–767. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00224-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora P, Kempf A, Nehlmeier I, et al. Augmented neutralisation resistance of emerging omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1117–1118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00422-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheward DJ, Kim C, Fischbach J, et al. Omicron sublineage BA.2.75.2 exhibits extensive escape from neutralising antibodies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1538–1540. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00663-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheaffer SM, Lee D, Whitener B, et al. Bivalent SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines increase breadth of neutralization and protect against the BA.5 omicron variant in mice. Nat Med. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02092-8. published online Oct 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurhade C, Zou J, Xia H, et al. Low neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 by 4 doses of parental mRNA vaccine or a BA.5-bivalent booster. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.10.31.514580. published online Nov 2. (preprint). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller J, Hachmann NP. Collier A-r Y, et al. Substantial neutralization escape by the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant BQ.1.1. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.11.01.514722. published online Nov 2. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis-Gardner ME, Lai L, Wali B, et al. mRNA bivalent booster enhances neutralization against BA.2.75.2 and BQ.1.1. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.10.31.514636. published online Nov 1. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, Muecksch F, et al. Measuring SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody activity using pseudotyped and chimeric viruses. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20201181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Y, Yisimayi A, Jian F, et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection. Nature. 2022;608:593–602. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04980-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park YJ, Pinto D, Walls AC, et al. Imprinted antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Science. 2022;378:619–627. doi: 10.1126/science.adc9127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.