Keywords: development, GABA, hypoglossal, nicotine

Abstract

Regulation of GABAergic signaling through nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) activation is critical for neuronal development. Here, we test the hypothesis that chronic episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE) disrupts GABAergic signaling, leading to dysfunction of hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs), which innervate the tongue muscles. We studied control and eDNE pups at two developmentally vulnerable age ranges: postnatal days (P)1–5 and P10–12. The amplitude and frequency of spontaneous and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs, mIPSCs) at baseline were not altered by eDNE at either age. In contrast, eDNE increased GABAAR-α1 receptor expression on XIIMNs and, in the older group, the postsynaptic response to muscimol (GABAA receptor agonist). Activation of nAChRs with exogenous nicotine increased the frequency of GABAergic sIPSCs in control and eDNE neurons at P1–5. By P10–12, acute nicotine increased sIPSC frequency in eDNE but not control neurons. In vivo experiments showed that the breathing-related activation of tongue muscles, which are innervated by XIIMNs, is reduced at P10–12. This effect was partially mitigated by subcutaneous muscimol, but only in the eDNE pups. Taken together, these data indicate that eDNE alters GABAergic transmission to XIIMNs at a critical developmental age, and this is expressed as reduced breathing-related drive to XIIMNs in vivo.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Here, we provide a thorough assessment of the effects of nicotine exposure on GABAergic synaptic transmission, from the cellular to the systems level. This work makes significant advances in our understanding of the impact of nicotine exposure during development on GABAergic neurotransmission within the respiratory network and the potential role this plays in the excitatory/inhibitory imbalance that is thought to be an important mechanism underlying neonatal breathing disorders, including sudden infant death syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

GABAA receptors (GABAARs) are GABA-gated anion channels responsible for most fast inhibitory synaptic transmission in the vertebrate central nervous system (CNS). In the adult CNS, GABAA receptor activation allows Cl− to move into the cell, causing a strong inhibitory hyperpolarization of the membrane potential, negatively regulating the glutamatergic excitatory activity of neurons (1, 2). GABAA receptors are also expressed in mammalian brain tissue as early as embryonic day (E)10, before the onset of synaptic inhibition, suggesting their involvement in brain development (3). Because of high expression of the sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter NKCC1, immature neurons have increased intracellular chloride concentrations that shift the equilibrium potential for Cl− to values less negative than the resting membrane potential. As a result, opening of a GABAAR channel leads to efflux of Cl−, which depolarizes the neuron, activates voltage-sensitive calcium channels and calcium-sensitive signaling cascades (4, 5). Thus, during the embryonic and early neonatal period, GABA serves as a trophic factor and may be involved in controlling morphogenesis, regulating cell proliferation, cell migration, axonal growth, synapse formation, steroid-mediated sexual differentiation, and cell death (4, 6–8).

Nicotinic signaling through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) is also implicated in early development as a regulator of neurite growth and pathfinding and in the development of functional neural circuits (9). Nicotinic cholinergic activity triggers the GABAergic shift from excitation to inhibition by driving expression of the mature chloride transporter, NKCC2 (10). In addition, activation of nAChRs located on the cell bodies, dendrites, and axon end terminals of GABAergic neurons throughout the CNS stimulates GABA release (11–13). It is therefore not surprising that nicotine exposure is known to have severe consequences for both brain development and the alteration of neural circuit function.

Previous work in our laboratory has focused on studying the effects of nicotine exposure on the development of hypoglossal motor neurons, which innervate the muscles of the tongue, subserving several critical homeostatic functions in early neonatal life, including vocalization, suckling, and maintaining an open upper airway during respiration (14, 15). Electrophysiology experiments in multiple preparations show that chronic, sustained nicotine exposure during development, mimicking the use of a nicotine patch, alters GABAergic synaptic transmission to hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs) in neonatal rats in the first week of life (15, 16), a period roughly correlating to the third trimester of human gestation (17). However, normal development of XIIMNs is marked by significant changes to GABAergic signaling beyond the prenatal and immediate postnatal periods, including fluctuations in GABAAR subunit expression and the amplitude, frequency, and kinetics of GABAergic currents. Importantly, an abrupt and significant increase in GABAergic inhibition is observed at the end of the second postnatal week in rats (18, 19). This time frame, referred to as a “critical period” of respiratory network development, is marked by an imbalance in excitatory and inhibitory influences on XIIMNs and weakened chemoreflex responses (10, 18).

Here, we make significant advances on previous work studying the effects of developmental nicotine exposure on GABAergic synaptic transmission to XIIMNs. First, in most of the prior work by our laboratory and others the osmotic minipump method was used for continuous nicotine delivery to a pregnant rodent. However, most nicotine use (via cigarettes, e-cigarettes, nicotine gum, etc.) results in intermittent exposure. Therefore, we exposed pregnant rats to chronic, episodic nicotine through drinking water [episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE)]. Second, we studied neonatal rats at postnatal days (P)1–5 and at P10–12, which encompasses the days leading up to and within the critical period of respiratory system development. We tested the hypotheses that eDNE alters GABAergic synaptic transmission, the postsynaptic response to GABAAR activation, and GABAAR expression in XIIMNs in vitro. We also studied the tongue muscle electromyographic (EMG) response to nasal occlusion after pretreatment with a subcutaneous dose of saline (control) or muscimol, a GABAAR agonist. The results of these experiments indicate that eDNE causes significant changes to GABAergic signaling that may exacerbate chemoreflex control abnormalities during a critical period in postnatal respiratory network development.

METHODS

Ethical Approval

All procedures were approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and are in accordance with guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health.

Animals

Data from 85 rat pups of either sex were used in two age groups: postnatal days (P)1–5, corresponding to 23–35 wk of gestation in humans (preterm infant), and P10–12, corresponding to 40 wk of gestation in humans (full-term infant). The P10–12 age in rats represents the days just before and encompassing a critical period in brain stem neuronal development (17). Pups were born via spontaneous vaginal delivery from pregnant adult female Sprague-Dawley rats purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Pups were housed with their mothers and littermates in the animal care facility (12:12-h light-dark cycle, 22°C, 30–70% relative humidity) with food and water available ad libitum.

eDNE

Nicotine exposure was established by exposing pregnant dams to nicotine through their drinking water starting on embryonic day 5. This results in in utero fetal exposure via the placenta, with continued exposure of the pups after birth through the breast milk. Exposure is considered “episodic” because the dam takes in nicotine only when drinking, as opposed to our previous model using the implanted osmotic pump, considered “continuous” exposure, which delivers nicotine at a constant rate. Nicotine was used at a concentration of 0.08 mg/mL tap water and mixed with 10 mg/mL of saccharin for palatability. Previous experiments have confirmed that this dose of nicotine creates blood levels of cotinine, a stable metabolic by-product of nicotine, similar to those found in the plasma of infants born to mothers who are considered moderate smokers (20–22). Waters were prepared fresh and replaced every 3 days. Control pups were obtained from pregnant dams that received saccharin water only.

Medullary Slice Preparation

P1–5.

Procedures were followed as described in previous publications (15, 22–24). Briefly, pups were weighed and anesthetized on ice. After decerebration at the coronal suture, the vertebral column and ribcage were exposed and placed in ice-cold (∼4°C), oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mM) 120 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 30 glucose, 1 MgSO4, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 1.2 CaCl2, with pH adjusted to 7.4 and osmolarity between 300 and 325 mosM. The brain stem and spinal cord were extracted, and all tissue above the pontomedullary junction was removed. The preparation was then glued to an agar block with the rostral surface up and submerged in ice-cold, oxygenated aCSF, and 250-μm transverse medullary slices were cut from the region containing the hypoglossal motor nucleus with a vibratome (7000smz; Campden Instruments). Slices were transferred to an equilibration chamber containing fresh, oxygenated, room-temperature aCSF, where they recovered for 1 h before use.

P10–12.

Procedures aimed to improve tissue health and the success rate for patch-clamp recordings in older rodents were followed as described in a recent publication from our laboratory (22) and detailed by Ting et al. in 2014 (25). Pups were weighed and deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in room air. The chest cavity was then opened to expose the heart, and the pups were transcardially perfused with ice-cold, oxygenated N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) aCSF containing (in mM) 92 NMDG, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 25 glucose, 2 thiourea, 5 Na-ascorbate, 3 Na-pyruvate, 0.5 CaCl2·H2O, and 10 MgSO4·7H2O, with pH adjusted to 7.3. After perfusion, the brain stem and spinal cord were prepared for slicing in a vibratome as above and submerged in ice-cold, oxygenated NMDG aCSF. Slices were then transferred to a recovery chamber containing oxygenated NMDG aCSF maintained at 32°C for 12 min and finally to a second recovery chamber containing room-temperature, oxygenated HEPES aCSF containing (in mM) 92 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 25 glucose, 2 thiourea, 5 Na-ascorbate, 3 Na-pyruvate, 2 CaCl2·4H2O, and 2 MgSO4·7H2O, with pH adjusted to 7.3.

Electrophysiology

Equilibrated slices were transferred to a recording chamber and perfused with oxygenated aCSF (see P1–5) maintained at 27°C (TC-324B temperature controller; Warner Instruments Corporation). An Olympus BX-50WI fixed stage (×40 water-immersion objective, 0.75 NA) with differential contrast optics and a video camera (C2741-62; Hamamatsu) was used to visually identify XIIMNs based on their size and location. Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were made with glass pipettes (tip resistance 3–7 mΩ) pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass capillary tubes [outer diameter (OD): 1.5 mm, inner diameter (ID): 0.75 mm ] filled with intracellular solution containing (in mM) 130 CsCl, 5 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl, 10 HEPES, 2 ATP-Mg, and 2 sucrose, with pH adjusted to 7.2 and osmolarity between 250 and 275 mosM. This cesium-based intracellular solution sets the chloride reversal potential to ∼0 mV (−2.8 mV exact value), and under these conditions both excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents are inward at a holding potential of −70 mV. Filled pipettes were attached to a preamplifier mounted on a micromanipulator (MP-225; Sutter Instrument Company) connected to a MultiClamp 700B amplifier, and signals were digitized with a Digidata 1440A A/D converter (Molecular Devices).

The following procedures were followed for all recordings. XIIMNs were approached in voltage-clamp mode. After junction potentials were zeroed the pipette was apposed to the membrane, and once a gigaohm seal was achieved the membrane was ruptured by suction. Cells were initially held at −70 mV for a 5-min equilibration period to confirm stability of the recording. Cells were then briefly assessed in current-camp mode, and the resting membrane potential was recorded. Cells were not studied if the resting membrane potential was more depolarized than −45 mV. Cells were again recorded in voltage-clamp mode, the slow and fast components of the capacitive current transients were canceled to the extent possible, and series resistance was compensated with a correction coefficient of 60%. After corrections were made, the holding current was recorded, and then a square-wave voltage step from −70 mV to −80 mV was introduced to calculate the input resistance of the neuron.

Experimental Protocols

GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents.

Spontaneous inhibitory synaptic events were recorded at baseline and after activation of nAChRs with bath-applied nicotine. We pharmacologically isolated GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) by using 20 µM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinozaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 0.5 µM d-(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP-5), and 0.5 µM strychnine hydrochloride to antagonize the AMPA-type glutamate receptors, NMDA receptors, and glycine receptors, respectively. Baseline sIPSCs were recorded for 5 min, after which 0.5 µM nicotine bitartrate was added to the superfusate and sIPSCs were recorded for an additional 5 min.

GABAergic miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents.

Since sIPSCs reflect both action potential-mediated synaptic release and spontaneous, action potential-independent, quantal release of neurotransmitter, we also examined the influence of DNE on the latter by recording miniature postsynaptic currents before and after bath application of acute nicotine. After a stable recording was achieved, CNQX, AP-5, and strychnine were added to the superfusate, followed by the addition of 1 µM tetrodotoxin (TTX) to block voltage-gated sodium channels, and GABAergic miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded. After 5 min of baseline recording, nicotine was added to the superfusate and mIPSCs were recorded for an additional 5 min.

Postsynaptic GABAA current.

To evaluate the influence of DNE on postsynaptic GABAA receptors, recordings were again made in the presence of CNQX, AP-5, strychnine, and TTX. After 5 min of this drug cocktail, 0.5 µM muscimol was added to the superfusate for 5 min, followed by a 5-min washout period.

Drugs

Drugs and concentrations used for electrophysiology experiments are shown in Table 1. Drugs were purchased from Sigma, except for nicotine bitartrate (MP Biomedicals) and TTX (R&D Chemicals). All drugs were mixed in aCSF on the day of the experiment from previously mixed aliquots that were stored at 0–2°C. Antagonists were used at concentrations known to be effective based on our previous studies and the literature. Nicotine was used at a dose that is within the range of what is found in the blood of humans after smoking one cigarette (26) and produces presynaptic release of neurotransmitter without producing a significant postsynaptic inward current, which can create significant noise in the record and impede visualization of sIPSCs and mIPSCs. For in vitro electrophysiology experiments, muscimol was used at a concentration based on a previous publication (27) that produced approximately half-maximal effects in our own dose-response experiments (L. B. Wollman and R. F. Fregosi, unpublished observations). All solutions were oxygenated, maintained at 27°C, and perfused into the recording chamber at a rate of 1.5–2 mL/min.

Table 1.

List of drug cocktails used to isolate GABA sIPSCs, mIPSCs, and the GABAA receptor-mediated postsynaptic current

| Age (n neurons, control: eDNE) | |

|---|---|

| GABA sIPSCs | |

| Baseline: 20 µM CNQX, 0.5 µM AP-5, 0.5 µM strychnine | P1–5 (10:10), P10–12 (10:10) |

| Nicotine: + 0.5 µM nicotine | P1–5 (10:10), P10–12 (10:10) |

| GABA mIPSCs | |

| Baseline: 20 µM CNQX, 0.5 µM AP-5, 0.5 µM strychnine, 1 µM TTX | P1–5 (10:10), P10–12 (10:10) |

| Nicotine: + 0.5 µM nicotine | P1–5 (10:10), P10–12 (10:10) |

| Postsynaptic GABAA current | |

| 20 µM CNQX, 0.5 µM AP-5, 0.5 µM strychnine, 1 µM TTX, 0.5 µM muscimol | P1–5 (10:10), P10–12 (10:10) |

n reflects the number of neurons assessed. AP-5, d-(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid; CNQX, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinozaline-2,3-dione, eDNE, episodic developmental nicotine exposure; mIPSC, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current; P, postnatal days; sIPSC, spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic current.

GABAAR Immunohistochemistry

Neonates were anesthetized on ice (P1–5) or with isoflurane (P10–12) and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Brain stems were rapidly removed and postfixed for 36 h in the perfusion solution, followed by a wash in PBS. Fixed brain stems were agar embedded and placed in a vibratome (VT1000; Leica). Transverse sections 40 µm thick were taken through the medulla, starting rostrally at approximately the pontomedullary junction and extending caudally to the spinomedullary junction. To identify GABAA receptors, sections were mounted serially on gelatin-coated glass slides and dried for at least 24 h. Tissue samples were rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed at 90°C in Tris-EDTA buffer. Sections underwent two blocking steps: an endogenous peroxidase block (3% H2O2 in PBS) and a 2.5% normal goat serum block. Primary antibody (Rabbit Anti-GABAA Receptor α1 Antibody; Sigma-Aldrich, 1:250 in 0.4% Triton X-PBS) was applied and incubated overnight at room temperature with agitation. Sections were incubated in Peroxidase Polymer Anti-Rabbit IgG Reagent (ImmPRESS HRP Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG Polymer Detection Kit; Vector Labs) for 30 min at room temperature with agitation. 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) (MP Biomedicals) was applied as a chromogen for detection. As a negative control, tissue samples were processed as above but without the primary antibody, which resulted in nonspecific staining. For positive controls, the antibody has been verified by the company (Sigma-Aldrich), and also we know that GABAARs containing the α1 subunit are present in these tissue slices, which has been confirmed in prior experiments (16).

EMG Recordings of Tongue and Diaphragm Muscle

P10–12 rat pups were lightly anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (30 mg/mL), xylazine (6 mg/mL), and acepromazine (3 mg/mL) injected subcutaneously at a volume corresponding to ∼0.35 mL/g body wt. Pain sensitivity was assessed via multiple paw pinches initiated 10 min after the injection. Supplemental anesthetic was added until retraction to pinch was abolished. With the pup in the supine position, fine-wire electrodes were used to record whole muscle EMG activity of the diaphragm muscle and the genioglossus muscle (GG; a tongue protrudor muscle) as described previously (22, 24, 28–30). An additional electrode placed into the scruff of the neck served as an electrical ground. EMG signals were filtered (30–3,000 Hz), amplified (Grass P122 AC amplifiers), and sent to an A/D converter [Cambridge Electronic Design (CED); model 1401], which sampled the signal at a rate of 8,300 Hz. EMG signals were displayed in real time on a computer monitor (Spike2 software) and stored on a hard drive for analysis offline.

After implantation of EMG electrodes, a stable baseline was recorded for at least 10 min, after which the animal received a subcutaneous injection of either muscimol (1 mg/kg in saline) or saline alone. Injection was made in the scruff at the back of the animal’s neck. Thirty minutes after injection the animal was challenged with nasal occlusions, resulting in strong breathing efforts but an absence of lung inflation as well as hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis. Each animal was subjected to two 15-s nasal occlusions, with 10 min of rest in between. After experiments, animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Animal weight and age were compared between control and eDNE by a two-way ANOVA with group means compared by Tukey’s post hoc test (Prism GraphPad). For initial analyses, animals within each group (i.e., control and eDNE) at each age (i.e., P1–5 and P10–12) were compared for sex differences. Consistent with previous work, we did not find any differences between males and females within treatment groups for any of the parameters measured. Select sex-based analyses are shown in Table 2. Since no sex differences were observed, all other results reported are from males and females combined.

Table 2.

Sex-based analyses of GABAergic sIPSCs and mIPSCs at baseline and GG EMG latency after saline injection

| Control Male vs. Female | eDNE Male vs. Female | |

|---|---|---|

| P1–5 | ||

| sIPSCs (at baseline) | ||

| Amplitude | P = 0.5919 | P = 0.2179 |

| Frequency | P = 0.2360 | P = 0.8732 |

| mIPSC (at baseline) | ||

| Amplitude | P = 0.4891 | P = 0.4532 |

| Frequency | P = 0.8760 | P = 0.6453 |

| P10–12 | ||

| sIPSCs (at baseline) | ||

| Amplitude | P = 0.5629 | P = 0.2104 |

| Frequency | P = 0.2967 | P = 0.4310 |

| mIPSC (at baseline) | ||

| Amplitude | P = 0.6235 | P = 0.3454 |

| Frequency | P = 0.7426 | P = 0.5354 |

| In vivo EMG | ||

| GG latency (saline injection) | P = 0.7091 | P = 0.7141 |

| GG latency (muscimol injection) | P = 0.5378 | P = 0.9514 |

For each parameter, P values reflect differences between males and females; n reflects the number of neurons or pups of each sex. Each parameter was analyzed with a Student’s unpaired t test. P1–5 sIPSCs: control n = 6 male, 4 female; eDNE n = 5 male, 5 female. P1–5 mIPSCs: control n = 3 male, 7 female; eDNE n = 4 male, 6 female. P10–12 sIPSCs: control n = 5 male, 5 female; eDNE n = 6 male, 4 female. P10–12 mIPSCs: control n = 5 male, 5 female, eDNE n = 5 male, 5 female. In vivo EMG GG latency (Saline): control n = 3 male, 3 female; eDNE n = 3 male, 3 female. In vivo EMG GG Latency (Muscimol): control n = 3 male, 3 female; eDNE n = 3 male. 3 female. eDNE, episodic developmental nicotine exposure; EMG, electromyography; GG, genioglossus muscle; mIPSC, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current; P, postnatal days; sIPSC, spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic current.

In Vitro Electrophysiology

All in vitro data were obtained with Clampex software (Molecular Devices). Differences in age, weight, resting membrane potential, holding current, and input resistance were compared between neurons from control and eDNE animals across ages with a two-way ANOVA, with group means compared by Tukey’s post hoc test. Analysis included n = 30 neurons in each group at each age, and we used data obtained from one or two neurons per animal. In the P1–5 group, neurons were from n = 20 control and n = 18 eDNE pups; at P10–12, neurons were obtained from n = 9 control and n = 14 eDNE pups. For SIPSCs and mIPSCs, data were obtained from n = 10 neurons in each treatment group at each age. sIPSCs and mIPSCs were analyzed with a custom MATLAB code. For all IPSCs, the peak amplitude and interevent interval (IEI) were measured during the minute before nicotine application and throughout the third minute of nicotine application. Mean sIPSC/mIPSC amplitude and IEI before and after acute nicotine application were compared between neurons from control and eDNE animals across ages with a two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA, with group means compared by Sidak’s post hoc test.

For postsynaptic GABAA receptor-mediated current experiments, the peak of the inward current produced in response to bath-applied muscimol was measured. The peak current response to muscimol was compared between neurons from control and eDNE animals across ages with a two-way ANOVA, with group means compared by Tukey’s post hoc test (data obtained from n = 10 control and n = 10 eDNE neurons in each age group).

GABAA Receptor Immunohistochemistry

Data were collected from 18 pups in the P1–5 age group (9 control and 9 eDNE) and 10 pups in the P10–12 age group (5 control and 5 eDNE) (see Table 5). Approximately six brain sections were obtained per animal, and sections from control and eDNE animals were age matched and processed together on the same slide.

Table 5.

List of unique comparisons, number of neurons, average staining intensity, and significance for GABAAR-α1 subunit in control vs. eDNE preparations at P1–5 and P10–12

| Age Group | Comparison | Treatment Group | No. of Neurons | Average Intensity | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1–5 | 1 | P1 eDNE | 33 | 153 | <0.0001 |

| P1 Control | 33 | 139.2 | |||

| 2 | P1 eDNE | 20 | 124.2 | 0.0079 | |

| P1 Control | 20 | 120.1 | |||

| 3 | P2 eDNE | 32 | 129.5 | <0.0001 | |

| P2 Control | 32 | 120.4 | |||

| 4 | P2 eDNE | 13 | 130.1 | <0.001 | |

| P2 Control | 13 | 119.2 | |||

| 5 | P3 eDNE | 38 | 127.2 | <0.0001 | |

| P3 Control | 38 | 108.2 | |||

| 6 | P3 eDNE | 17 | 142.6 | <0.0001 | |

| P3 Control | 17 | 133.6 | |||

| 7 | P4 eDNE | 24 | 136.8 | <0.0001 | |

| P4 Control | 24 | 129.3 | |||

| 8 | P5 eDNE | 38 | 167.2 | <0.0001 | |

| P5 Control | 36 | 147 | |||

| 9 | P5 eDNE | 24 | 143.9 | <0.0001 | |

| P5 Control | 24 | 126.7 | |||

| P10–12 | 10 | P10 eDNE | 24 | 105.5 | <0.0001 |

| P10 Control | 24 | 98.9 | |||

| 11 | P10 eDNE | 19 | 113.1 | 0.0003 | |

| P10 Control | 16 | 106.1 | |||

| 12 | P11 eDNE | 37 | 128.4 | <0.0001 | |

| P11 Control | 32 | 114.3 | |||

| 13 | P11 eDNE | 78 | 122.1 | 0.0913 | |

| P11 Control | 22 | 119.5 | |||

| 14 | P12 eDNE | 26 | 116.7 | <0.0001 | |

| P12 Control | 26 | 104.5 |

Each comparison was analyzed with a Student’s unpaired t test. eDNE, episodic developmental nicotine exposure; GABAAR, GABAA receptor; P, postnatal day.

Quantitative analysis of GABAAR-α1 subunit density is based on the approach from previous work from our laboratory (16), but with an important modification. Whereas in previous work we computed staining intensity thresholds manually, here we used an automated thresholding technique. First, digital images of sections were taken with a Zeiss Axiolab 5 microscope with standard lighting conditions and GRYPHAX software (JENOPTIK). Next, images were converted to 8-bit grayscale with ImageJ (NIH). Third, we used the ImageJ automatic thresholding software to identify the neurons in each slice with the highest staining intensity [i.e., the highest mean gray value (MGV)]. This was done to ensure unbiased selection of the neurons chosen for quantitative analysis. Fourth, selected neurons from each slide were manually outlined, and the MGVs were recorded and normalized against an unstained region within the same slide.

For statistical analysis, average MGVs from control and eDNE XIIMNs that were assayed on the same slide were compared with an unpaired Student’s t test. This resulted in 14 unique comparisons, ensuring that the only difference in staining intensity is the result of differences in experimental treatment (control vs. nicotine exposed). For example, the first comparison in Table 5 shows the results of a t test comparing the average intensity of 33 neurons obtained from the brain sections of one eDNE animal and 33 neurons obtained from the brain of one control animal that were processed together on the same slide. In total, we performed 14 of these separate assays, each analyzed as an individual comparison: 9 from pups aged P1–5 and 5 from pups aged P10–12 (Table 5). In a separate analysis, we then combined all neurons from all 14 assays. For the P1–5 age group, this included 239 neurons from eDNE preparations and 237 neurons from control preparations. For the P10–12 age group, this included 184 neurons from eDNE and 120 neurons from control preparations. The average MGVs of all neurons were then compared across treatment groups and age by a two-way ANOVA, with group means compared by Tukey’s post hoc test (see Fig. 5C). All analyses of MGV were performed on unaltered images. For illustrative purposes, the images shown have been enhanced identically in each treatment and age group (see Fig. 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

GABAA receptor (GABAAR)-α1 immunohistochemistry. A: example images of tissue samples stained for the GABAAR-α1 subunit in a postnatal (P)3 control (left) and a P3 episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE, right) preparation. B: example images of tissue samples stained for the GABAAR-α1 subunit in a P10 control (left) and a P11 eDNE (right) preparation. C: in both age groups, GABAAR-α1 receptor subunit immunostaining was increased in eDNE compared with control (2-way ANOVA, P1–5: n = 255 control and n = 257 eDNE, P < 0.0001; P10–12: n = 114 control and n = 178 eDNE, P < 0.0001). In both control (P < 0.0001) and eDNE (P < 0.0001) groups, receptor expression decreased with age. #Significant differences.

In Vivo EMG

Genioglossus EMG activity in response to nasal occlusion was measured in pups aged P10–12. The time between onset of nasal occlusion and the first GG EMG burst was defined as the response latency. Latency was measured after saline injection in six saccharin control pups and six eDNE pups and after muscimol injection in six saccharin control pups and six eDNE pups. The response latencies in animals in each of these four groups were compared with a one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

All statistical analyses were performed with Prism 9 (GraphPad). For all analyses, P < 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance. All experimental data are presented as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Age and Weight of Pups and Resting Membrane Potential, Holding Current, and Input Resistance of XIIMNs

As shown in Fig. 1, there was no difference in average age (P = 0.7029; Fig. 1A) or body weight (P = 0.4406; Fig. 1B) of control and eDNE pups within each of the age groups. As expected, animals in the P10–12 age group weighed significantly more than animals in the P1–5 age group (P1–5: n = 20 control and n = 18 eDNE pups; P10–12: n = 9 control and n = 14 eDNE pups). A total of 120 neurons from 61 pups across 26 litters (11 control and 15 eDNE) were used for electrophysiology experiments. Resting membrane potential (P = 0.8410; Fig. 1C), holding current (P = 0.3755; Fig. 1D), and input resistance (P = 0.2449; Fig. 1E) did not differ between XIIMNs from control or eDNE pups at either age, nor did they differ between age groups.

Figure 1.

Weight, age, resting membrane potential, holding current, and input resistance. There were no differences in age (A) or weight (B) between control and episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE) pups at either age [postnatal days(P)1–5: n = 20 control and n = 18 eDNE; P10–P12: n = 9 control and n = 14 eDNE]. There was also no difference in resting membrane potential (C), holding current (D), or input resistance (E) of hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs) from control and eDNE pups at either age (n = 30 control and n = 30 eDNE neurons in each age group). All data presented as means ± SD. Comparisons were made between control and eDNE across ages with a 2-way ANOVA, with group means compared by Tukey’s post hoc test. #Significant difference between age groups.

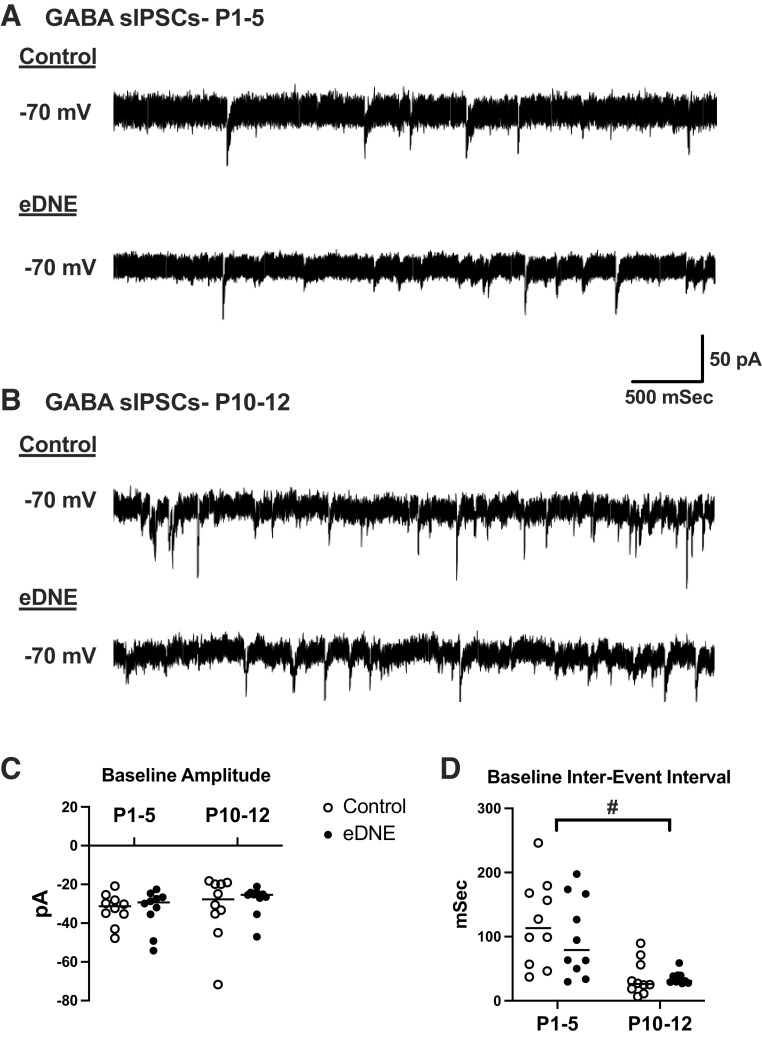

Frequency and Amplitude of GABAergic sIPSCs at Baseline

GABAergic interneurons that make synaptic contact with a postsynaptic neuron (here, the hypoglossal motor neurons) generate spontaneously occurring IPSCs (sIPSCs). The sIPSCs arise both from random quantal release of GABA (i.e., action potential-independent release) from presynaptic vesicles and via vesicular release that is triggered by action potentials generated in the GABAergic interneuron. Although precise interpretation of changes in the frequency and amplitude of sIPSCs is debated (31), in general the frequency reflects the probability of GABA release (whether from spontaneous vesicular release or from action potential-mediated release), whereas the amplitude reflects the postsynaptic response to the GABA that is released from each vesicle. To evaluate the influence of eDNE on GABAergic sIPSCs in hypoglossal motor neurons under baseline conditions, we computed the amplitude and interevent interval (IEI, the reciprocal of frequency) of every IPSC recorded over a 5-min period.

Figure 2A shows example recordings of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic sIPSCs from a P4 control (Fig. 2A, top) and a P3 eDNE (Fig. 2A, bottom) neuron. Figure 2B shows example recordings of GABAergic sIPSCs from a P11 control (Fig. 2B, top) and a P11 eDNE (Fig. 2B, bottom) neuron. There was no difference in the baseline amplitude of GABAergic sIPSCs recorded from control (P1–5: −32.8 ± 8.1 pA; P10–12: −31.8 ± 16.5 pA) and eDNE (P1–5: −33.1 ± 10.5 pA; P10–12: −28.2 ± 7.6 pA) neurons at either age, nor was there a change in sIPSC amplitude with age (F = 0.2970, P = 0.5892) (Fig. 2C). The frequency of GABAergic sIPSCs also was not different between control and eDNE neurons at either age. However in both groups, IEIs of sIPSCs were significantly shorter at P10–12 (control: 36.1 ± 27.2 ms; DNE: 35.2 ± 9.6 ms) compared with P1–5 (control: 121.6 ± 66.9 ms; DNE: 99.9 ± 62.1 ms) (F = 24.62, P < 0.0001), indicating a higher frequency of sIPSCs in the older pups (Fig. 2D), but with no impact of eDNE at either age These data are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Amplitude and interevent interval (IEI) of GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) at baseline. A: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic sIPSCs in hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs) from a postnatal day (P)3 control (top) and a P3 episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE, bottom) animal. B: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic sIPSCs in XIIMNs from a P10 control (top) and a P11 eDNE (bottom) animal. C: there was no difference in baseline amplitude of sIPSCs between control and eDNE at either age (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control and eDNE: P1–5, P > 0.9999; P10–12, P = 0.9797), nor was there a difference in sIPSC amplitude between age groups (control, P > 0.9999; eDNE, P = 0.9151). D: there was no difference in the IEI of sIPSCs between control and eDNE at either age (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control and eDNE: P1–5, P = 0.7428; P10–12, P > 0.9999); however, in both control and eDNE neurons, IEI was significantly shorter at P10–12 than at P1–5 (control, P = 0.0017; eDNE, P = 0.0227). Horizontal lines indicate mean values. #Significant difference between age groups.

Table 3.

Amplitude and IEI of GABAergic sIPSCs recorded at baseline and during application of acute nicotine

| Baseline | + 0.5 mM Nicotine | P | n Cells (control:eDNE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1–5 | 10:10 | |||

| Amplitude, pA | ||||

| Control | −32.8 ± 8.1 | −23.4 ± 3.1 | 0.0028 | |

| eDNE | −33.1 ± 10.5 | −27.7 ± 8.9 | 0.2317 | |

| IEI, ms | ||||

| Control | 1,216 ± 66.9 | 67.2 ± 38.8 | 0.0391 | |

| eDNE | 99.9 ± 62.2 | 52.4 ± 24.6 | 0.0372 | |

| P10–12 | 10:10 | |||

| Amplitude | ||||

| Control | −31.8 ± 16.5 | −32.7 ± 17.3 | 0.9974 | |

| eDNE | −28.2 ± 7.6 | −27.3 ± 5.8 | 0.7698 | |

| IEI | ||||

| Control | 36.1 ± 27.2 | 30.2 ± 20.2 | 0.5914 | |

| eDNE | 35.2 ± 9.6 | 26.4 ± 4.9 | 0.0198 |

Values expressed as means ± SD. n reflects the number of neurons assessed. eDNE, episodic developmental nicotine exposure; IEI, interevent interval; P, postnatal days; sIPSC, spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic current. Comparisons were made between control and eDNE across ages with a 2-way, repeated-measures ANOVA with group means compared by Sidak’s post hoc test. P values reflect differences between control and eDNE at each age; significant values are in bold.

Frequency, Amplitude, and Recovery Time Constant of GABAergic mIPSCs at Baseline

Miniature IPSCs reflect the postsynaptic response to a single vesicle of neurotransmitter, in this case GABA. Changes in the amplitude of mIPSCs are usually thought to reflect changes in the sensitivity of the postsynaptic receptors; however, under some conditions this effect can also have a presynaptic origin (31, 32). Miniature IPSCs can be observed only under conditions in which presynaptic action potentials are blocked. Here, we bath applied TTX to block action potentials everywhere in the slice. To evaluate the influence of eDNE on GABAergic mIPSCs in hypoglossal motor neurons under baseline conditions, we computed the amplitude and IEI of every mIPSC recorded over a 5-min period. Figure 3A shows example recordings of GABAergic mIPSCs from a P3 control (Fig. 3A, top) and a P3 eDNE (Fig. 3A, bottom) neuron. Figure 3B shows example recordings of GABAergic mIPSCs from a P10 control (Fig. 3B, top) and a P12 eDNE (Fig. 3B, bottom) neuron. As with GABAergic sIPSCs, there was no difference in the baseline amplitude of GABAergic mIPSCs recorded from control (P1–5: −6.2 ± 0.5 pA; P10–12: −7.8 ± 2.3 pA) or eDNE (P1–5: −6.4 ± 1.1 pA; P10–12: −8.3 ± 2.8 pA) neurons at either age, nor was there a change in mIPSC amplitude with age (F = 0.08402, P = 0.7736) (Fig. 3C). The frequency of GABAergic mIPSCs also was not different between control and eDNE neurons at either age. However, in both control and eDNE groups, IEIs of mIPSCs were significantly shorter at P10–12 (control: 414.1 ± 368.8 ms; eDNE: 737.7 ± 894.3 ms) compared with P1–5 (control: 1,847.4 ± 2,007.6 ms; DNE: 2,048.6 ± 1,714.9 ms) (F = 9.523, P = 0.0039) (Fig. 3D). Data are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Amplitude and interevent interval (IEI) of GABAergic miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) at baseline. A: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic mIPSCs in hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs) from a postnatal day (P)2 control (top) and a P3 episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE, bottom) animal. B: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic mIPSCs in XIIMNs from a P11 control (top) and a P12 eDNE (bottom) animal. Asterisks highlight individual currents. C: there was no difference in baseline amplitude of mIPSCs between control and eDNE at either age (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control and eDNE: P1–5, P = 0.9944; P10–12, P = 0.9114), nor was there a difference in mIPSC amplitude between age groups (control, P = 0.2786; eDNE, P = 0.1332). D: there was no difference in the IEI of mIPSCs between control and eDNE at either age (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control and eDNE: P1–5, P = 0.9885; P10–12, P = 0.9551); however, in both control and eDNE neurons, IEI was significantly shorter at P10–12 than at P1–5 (control, P = 0.1219; eDNE P = 0.1774). Horizontal lines indicate mean values. #Significant difference between age groups.

Table 4.

Amplitude and IEI of GABAergic mIPSCs recorded at baseline and during application of acute nicotine and tau of mIPSCs recorded at baseline

| Baseline | + 0.5 mM Nicotine | P | n Cells (Control:eDNE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1–5 | 10:10 | |||

| Amplitude, pA | ||||

| Control | −6.2 ± 0.5 | −6.8 ± 1.1 | 0.1456 | |

| eDNE | −6.4 ± 1.1 | −7.1 ± 1.9 | 0.3937 | |

| IEI, ms | ||||

| Control | 1,847.4 ± 2,007.6 | 3,791.2 ± 7,518.4 | 0.5772 | |

| eDNE | 2,048.6 ± 1,714.9 | 2,020.1 ± 1,933.3 | 0.9727 | |

| Tau, ms | ||||

| Control | 5.1 ± 3.2 | 3.9 ± 3.2 | 0.2550 | |

| eDNE | 8.1 ± 5.1 | 9.2 ± 5.3 | 0.0162* | |

| IMuscimol, pA | ||||

| Control | −653.1 ± 216.4 | |||

| eDNE | −554.7 ± 305.3 | |||

| P10–12 | 10:10 | |||

| Amplitude, pA | ||||

| Control | −7.8 ± 2.3 | −9.1 ± 5.7 | 0.5263 | |

| eDNE | −8.3 ± 2.8 | −7.7 ± 1.9 | 0.5445 | |

| IEI, ms | ||||

| Control | 414.1 ± 368.8 | 357.4 ± 446.7 | 0.7595 | |

| eDNE | 737.7 ± 894.3 | 1,024.5 ± 1,507.9 | 0.6119 | |

| Tau, ms | ||||

| Control | 10.1 ± 3.7^ | 4.9 ± 3.9 | 0.0004* | |

| eDNE | 10.9 ± 3.9 | 9.3 ± 3.3# | 0.2810 | |

| IMuscimol, pA | ||||

| Control | −434.5 ± 140.9 | |||

| eDNE | −742.9 ± 281.9# |

Values expressed as means ± SD. n reflects the number of neurons assessed. eDNE, episodic developmental nicotine exposure; IMuscimol, muscimol current; IEI, interevent interval; mIPSC, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current; P, postnatal days. P values reflect differences between control and eDNE at each age; significant values are in bold. Comparisons were made between control and eDNE across ages using a 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, with group means compared by Sidak’s post hoc test. *Significant differences between baseline and acute nicotine; ^significant differences between ages within a treatment group; #significant differences between control and eDNE at baseline within an age group.

GABAergic interneurons likely play an important role in motor neuron development, and GABAAR subunit expression appears to change over early development and in pathological conditions (33). Varying expression of different synaptic GABAAR subunits confers different decay kinetics of mIPSCs that may influence many neuronal processes and tune inhibition to individual cellular requirements (34). Table 4 reports GABAergic mIPSC decay time (tau) at baseline and during acute nicotine challenge in control and eDNE neurons. At P1–5, there was no difference in tau between control (5.1 ± 3.2 ms) and eDNE (8.1 ± 5.1 ms) neurons (F = 2.154, P = 0.4173). At this age, tau did not change with acute nicotine in control neurons (F = 0.0014, P = 0.2550); however, in eDNE neurons tau was significantly longer during acute nicotine than at baseline (F = 6.825, P = 0.0162). Tau significantly increased with age in control neurons (5.1 ± 3.2 ms at P1–5 vs. 10.1 ± 3.7 ms at P10–12, F = 9.760, P = 0.0035), but there was no significant change in eDNE neurons between the P1–5 and P10–12 age groups (8.1 ± 5.1 ms at P1–5 vs. 10.9 ± 3.9 ms at P10–12, F = 2.154, P = 0.1509), which may indicate a developmental alteration in GABAAR subunit expression associated with eDNE (see discussion). At P10–12, tau significantly decreased in control neurons during acute nicotine application (F = 18.95, P = 0.0004) but did not change in eDNE neurons (F = 3.134, P = 0.2810).

Postsynaptic GABAA Receptors

To gain a more complete understanding of the impact of eDNE on changes in GABAergic synaptic transmission, we directly assessed the response to activation of postsynaptic GABAA receptors with muscimol. Figure 4A shows example traces of the inward current that results from activation of postsynaptic GABAA receptors with bath application of 0.5 µM muscimol in one P2 control neuron (Fig. 4A, left) and one P4 eDNE neuron (Fig. 4A, right), and Fig. 4B shows the muscimol-mediated inward currents in one P11 control neuron (Fig. 4B, left) and one P10 eDNE neuron (Fig. 4B, right). At P1–5, the average peak amplitude of the inward current was not different between control (−653.1 ± 216.4 pA) and eDNE (−554.7 ± 305.3 pA) neurons (F = 1.842, P = 0.1831). Although there was also no change in average peak amplitude of the inward current with age in either group (F = 0.0386, P = 0.8453), by P10–12 muscimol produced a significantly larger peak current in eDNE (−742.9 ± 281.9 pA) neurons compared with control (−434.5 ± 140.9 pA) (F = 6.913, P = 0.0125) (Fig. 4C), indicating a stronger inhibitory response to activation of GABAA receptors in P10–12 nicotine-exposed animals.

Figure 4.

Activation of postsynaptic GABAA receptors. A: representative traces of the whole cell GABAA receptor-mediated inward current in hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs) from a postnatal (P)4 control (left) and a P4 episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE, right) animal. B: representative traces of the whole cell GABAA receptor-mediated inward current in XIIMNs from a P10 control (left) and a P10 eDNE (right) animal. C: at P1–5, activation of GABAA receptors with bath application of 0.5 µM muscimol resulted in a similar peak inward current in control and eDNE neurons. In the P10–12 age group, bath-applied muscimol resulted in a larger peak inward current in eDNE neurons compared with control (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control and eDNE: P1–5, P = 0.8052; P10–12, P = 0.0373). #Significant difference between control and eDNE.

GABAAR-α1 Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical probing of the GABAAR-α1 subunit in the XII motor nucleus was done to examine whether the influence of eDNE on the whole cell GABAA current can be explained by changes in receptor expression (Fig. 5). As described in methods, out of 14 unique assays (9 from P1–5 pups and 5 from P10–12 pups), eDNE preparations had significantly higher MGV than control (Table 5). Next, staining intensity on individual XIIMNs was evaluated (P1–5: 239 control and 237 eDNE neurons, P10–12: 184 control and 120 eDNE neurons). In the P1–5 group expression of the GABAAR-α1 subunit was examined in 237 control neurons and 239 eDNE neurons (Fig. 5A), and in the P10–12 age group we examined 120 control neurons and 184 eDNE neurons (Fig. 5B). In both age groups, GABAAR-α1 subunit immunostaining intensity was increased in eDNE samples compared with control (P1–5: P < 0.0001; P10–12: P < 0.0001).

The Effects of Acute Nicotine Challenge on GABAergic sIPSCs

Acute nicotine challenge stimulates nAChRs at pre- and postsynaptic sites, whereas chronic nicotine exposure causes long-term changes in nAChR number and/or function that could modify nicotine- and ACh-mediated GABA release from GABAergic interneurons. Accordingly, we bath applied 0.5 µM nicotine and evaluated changes in the frequency and amplitude of GABAergic sIPSCs. Example traces from one P3 control (Fig. 6A) and one P3 eDNE (Fig. 6B) neuron at baseline (top traces) and during acute nicotine application (bottom traces) are shown in Fig. 6. At P1–5, acute nicotine application did not significantly alter sIPSC amplitude in either group (F = 0.5626, P = 0.4629) (Fig. 6C). However, as is evident in the example traces, acute nicotine significantly increased the frequency of GABAergic sIPSCs in both control and eDNE XIIMNs (F = 10.22, P = 0.0028) (Fig. 6D). The average IEI for each neuron before and after acute nicotine application is summarized in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Amplitude and interevent interval (IEI) of GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) at baseline and during acute nicotine application in postnatal days (P)1–5 neurons. A: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic sIPSCs in hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs) from a P3 control animal at baseline (top) and during acute nicotine application (bottom). B: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic sIPSCs in XIIMNs from a P3 episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE) animal at baseline (top) and during acute nicotine application (bottom). C: acute nicotine application did not alter the amplitude of sIPSCs in either control or eDNE neurons (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control, P = 0.2863 and n = 10 eDNE, P = 0.2319). D: in both control neurons and eDNE neurons, acute nicotine application caused a decrease in sIPSC IEI (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control, P = 0.0391; n = 10 eDNE, P = 0.0372). Horizontal lines within the symbols indicate mean values. #Significant difference between baseline and acute nicotine application.

Figure 7 shows example traces from one P11 control (Fig. 7A) and one P10 eDNE (Fig. 7B) neuron at baseline (top traces) and during acute nicotine application (bottom traces). As in the P1–5 age group, at P10–12 acute nicotine application had no impact on sIPSC amplitude in either group (F = 0.009925, P = 0.9212) (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, the frequency of sIPSCs was also not altered by nicotine application in control neurons at this age (F = 0.6533, P = 0.4241) but was significantly increased in eDNE neurons at this age (F = 3.542, P = 0.0477) (Fig. 7D). The average IEI for each neuron, before and after acute nicotine application, is summarized in Table 3.

Figure 7.

Amplitude and interevent interval (IEI) of GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) at baseline and during acute nicotine application in postnatal days (P)10–12 neurons. A: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic sIPSCs in hypoglossal motor neurons (XIIMNs) from a P10 control animal at baseline (top) and during acute nicotine application (bottom). B: representative traces of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic sIPSCs in XIIMNs from a P10 episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE) animal at baseline (top) and during acute nicotine application (bottom). C: acute nicotine application did not alter the amplitude of sIPSCs in either control or eDNE neurons (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control, P = 0.9974 and n = 10 eDNE, P = 0.7698). D: in control neurons, acute nicotine application did not alter IEI of sIPSCs (2-way ANOVA, n = 10 control, P = 0.5914); however, in eDNE neurons acute nicotine application caused a decrease in sIPSC IEI compared with baseline (n = 10 eDNE, P = 0.0198). Horizontal lines indicate mean values. #Significant difference between baseline and acute nicotine application.

The Effects of Acute Nicotine Challenge on GABAergic mIPSCs

To assess whether activation of nAChRs at the GABAergic end terminals modulates the rate and amplitude of spontaneous single vesicle release, and to see whether eDNE modifies these variables, we added 0.5 µM nicotine to the drug cocktail described in Table 1 and analyzed changes in mIPSC amplitude and frequency. Nicotine application did not alter the amplitude or frequency (i.e., IEI) in control or eDNE neurons at either age. In the P1–5 age group, the mIPSC decay time (tau) significantly increased with acute nicotine application in eDNE neurons (F = 0.6825, P = 0.0162) but did not change in control neurons (F = 1.298, P = 0.2550). At P10–12, acute nicotine caused a significant decrease in control neurons (F = 3.422, P = 0.0004) but not in eDNE neurons (F = 5.009, P = 0.2810). These data are summarized in Table 3.

The Effects of Subcutaneous Muscimol on the Tongue Muscle EMG Response to Nasal Occlusion

The results from our electrophysiology experiments show that eDNE results in altered pre- and postsynaptic GABAergic transmission in XIIMNs at P10–12, including alterations in the development of GABAergic mIPSC decay, enhanced postsynaptic sensitivity to muscimol, and enhanced nAChR-mediated spontaneous GABAergic synaptic transmission that correlates with increased GABAAR-α1 subunit expression. To determine whether these cellular changes correlate with altered tongue muscle function in vivo, we performed EMG recordings of the GG muscle of the tongue (Fig. 8, A and B), which is innervated by XIIMNs and plays an important role in maintaining upper airway patency (35). To probe functional changes in GABAergic synaptic transmission, we challenged animals with 15-s nasal occlusions 30 min after subcutaneous injection of saline (sham) or muscimol. Twelve control (6 injected with saline, 6 with muscimol) and 12 eDNE (6 saline injected, 6 muscimol) pups from seven litters (4 control and 3 eDNE) were used for these experiments. After a delay, nasal occlusion is associated with a monotonic increase in the EMG activity of both the diaphragm (Fig. 6B, bottom) and GG (Fig. 6B, top) muscles. Consistent with previous work, after sham injection the onset latency of GG EMG activity during nasal occlusion was significantly longer in eDNE animals (14.1 ± 5.9 s) compared with control (6.6 ± 3.7 s) (P = 0.0101). Muscimol injection had no significant effect on onset latency in control animals (2.8 ± 1.2 s) (P = 0.3589); however, it significantly decreased latency in eDNE animals (7.7 ± 2.3 s) (P = 0.0321) compared with sham injection (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

In vivo experimental preparation and average genioglossus muscle (GG) latency in postnatal days (P)10–12 pups after saline or muscimol injection. A: schematic of the in vivo experimental preparation, which includes concurrent diaphragm (Dia) and GG electromyographic (EMG) recordings in lightly anesthetized rats. For details, see methods. High-frequency spikes in the diaphragm EMG are ECG artifacts. B: example traces from a P10 control animal (left) and a P11 episodic developmental nicotine exposure (eDNE) animal (right) showing the raw and the rectified and integrated GG and diaphragm EMG activities during a 15-s nasal occlusion (indicated by bold square), which was applied 30 min after a subcutaneous saline injection (sham). The time between the onset of the nasal occlusion and the first discernable GG muscle EMG burst (arrow) is defined as onset latency. C: in P10–12 rats after saline injection, onset latency of GG EMG bursts was significantly longer in eDNE pups compared with control (saccharin) pups (P = 0.0101). Muscimol injection had no effect on latency in control pups (P = 0.3589); however, in eDNE pups latency was decreased after muscimol injection (P = 0.0321) (1-way ANOVA, n = 12 control and n = 12 eDNE pups). All data represented as means ± SD. #Significant differences between groups.

DISCUSSION

We studied the effects of chronic eDNE on baseline and nicotine-mediated GABAergic synaptic transmission to XIIMNs, the postsynaptic current response to muscimol, a GABAAR agonist, and GABAAR expression in vitro. We also studied the effects of chronic eDNE on tongue muscle function in the presence or absence of muscimol in vivo. In the P1–5 age group, there was no difference in the frequency or amplitude of sIPSC or mIPSCs in XIIMNs at baseline or in response to acute activation of nAChRs with nicotine between control and eDNE. There was also no difference in the postsynaptic response to GABAAR activation with muscimol, although GABAAR immunofluorescence was enhanced in eDNE compared with control. At P10–12, there was no difference in the frequency or amplitude of sIPSCs or mIPSCs at baseline between control and eDNE neurons. However, in eDNE neurons at this age the frequency of sIPSCs increased with acute nicotine application, whereas in control neurons there was no response. There was also a significant increase in the postsynaptic current response to bath-applied muscimol in eDNE neurons at this age, which was accompanied by a significant increase in GABAAR immunostaining compared with control. Finally, at P10–12 eDNE animals exhibited a delayed GG onset latency compared with control animals during nasal occlusion. In eDNE animals this response time was significantly shortened 30 min after a subcutaneous injection of muscimol, whereas in control animals muscimol had no significant impact on latency. Together, these results indicate that eDNE enhances GABAergic synaptic transmission to XIIMNs through both pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms and alters respiratory-related tongue muscle function in pups at P10–12, which is a critical period in respiratory network development. The significance of these results is discussed below.

Influence of eDNE on Baseline GABAergic Synaptic Transmission to XIIMNs

Immediately after birth, rat XIIMNs are inhibited by synaptically released or exogenously applied GABA (36). Whereas glutamatergic synapses to XIIMNs drive the rhythmical activity that underlies oral motor functions and respiratory-related tongue muscle discharge, GABAergic, along with glycinergic and mixed GABA/glycinergic, synapses to XIIMNs play a crucial role in the control of coordinated movements of the tongue (37). Therefore, changes in the baseline strength of inhibitory GABAergic synaptic transmission to XIIMNs could have a significant effect on XII motor output and tongue muscle control.

In previous studies, we found that in XIIMNs from P1–5 pups chronic, sustained DNE using the osmotic pump model caused subtle changes to the baseline frequency and amplitude of GABAergic sIPSCs and mIPSCs, indicating a net reduction in GABAergic synaptic transmission at baseline due to DNE (15). In the present study, we found no differences in the baseline amplitude or frequency of sIPSCs or mIPSCs in either age group studied. Although we have found that our present nicotine exposure model results in plasma cotinine concentrations in the pups similar to what is achieved with the osmotic pump in both age groups (22), pharmacokinetic studies indicate that cotinine blood levels may not accurately represent nicotine concentrations in brain tissue (38). To our knowledge, brain nicotine and blood cotinine concentrations have not been compared across exposure models, as to do so a full dose response would be necessary for each condition. However, as we have proposed in previous work, it is possible that differences between our present model and the minipump exposure models might be explained simply by intermittent versus continuous DNE exposure resulting in significantly different brain nicotine concentrations, or that the pattern (intermittent vs. continuous) of nAChR activation by nicotine determines its effects (22).

Generally, the frequency of sIPSCs and mIPSCs reflects the probability of GABA release from presynaptic terminals, whereas the amplitude reflects the postsynaptic response to the GABA that is released from each vesicle (31). To further investigate the function of postsynaptic GABAARs, we assessed the effects of eDNE on the whole cell current response to muscimol, a GABAAR agonist. In the P1–5 age group, there was no difference in the whole cell current response to muscimol in eDNE compared with control; however, there was significantly increased immunostaining for the GABAAR-α1 subunit within the XII nucleus in eDNE preparations. Given that mIPSC amplitudes were the same between control and eDNE at this age, it is unlikely that this response can be explained by eDNE causing a change in the single-channel conductance of GABAARs that reside within the synaptic cleft. Since the synaptic pool of GABAARs is mainly controlled through regulation of internalization, recycling, and lateral diffusion of receptors (39, 40), one possible explanation for this paradoxical finding is that eDNE results in an increase of internalized GABAARs. Additionally, XIIMNs express a tonic GABA current, which is proposed to reduce the overall excitability of XIIMNs and is supported by δ-subunit-containing extrasynaptic GABAARs, which are high-affinity, muscimol-sensitive receptors (41, 42). The tonic, extrasynaptic GABAAR current is dependent on extracellular GABA concentration, which is highly regulated by GABA transporters (43). In these experiments, sIPSCs and mIPSCs reflect the function of synaptic GABAARs only; however, bath application of muscimol activates both synaptic and δ-subunit-containing extrasynaptic GABAARs. In previous work, the response to bath application of THIP, a specific δ-subunit-containing GABAAR agonist, was not different between control and DNE neurons (15). However, whether DNE/eDNE specifically changes δ-subunit-containing GABAARs or GABA transport mechanisms that may alter the whole cell GABAAR-mediated current in XIIMNs is not known.

By P10–12 there was an increase in GABAAR-α1 immunostaining, accompanied by an increase in the whole cell current response to muscimol in eDNE preparations. This is similar to what we have found in P1–5 rats with the osmotic pump model (15). Importantly, in previous studies it was observed that osmotic pump exposure causes XIIMNs to be smaller with a less complex dendritic arbor, potentially indicating developmental delay of neuron growth (44). Therefore, although XIIMN size was not assessed in the present study, it is possible that GABAAR-α1 immunostaining only appears increased because of differences in the size of neurons between control and eDNE, i.e., control neurons will have less staining per area because of the larger size of their cell bodies, which remain primarily unstained. Nevertheless, eDNE neurons are more sensitive to muscimol, indicating a functional increase in GABAARs. The reason for this increase is currently not known, but previous work has proposed that an increase in GABAARs on XIIMNs may be a homeostatic adjustment aimed at mitigating hyperexcitability, which has been characteristically observed in eDNE XIIMNs and is a presumed consequence of their smaller size (22, 45).

Finally, it is worth noting that GABAergic synaptic transmission to XIIMNs normally undergoes significant changes in the first 2 wk of life, including fluctuations in mIPSC kinetics owing to a gradual switch from high α1-subunit expression at birth to predominant α2 expression by P16 (18, 36, 46). In the present study, there were no differences in mIPSC amplitude between control and eDNE, nor did it change with age. However, although not different between control and eDNE at either age, the mIPSC decay time constant (tau) increased with age in control neurons but not in eDNE neurons. There are many reports indicating that the composition of GABAAR subunits dictates receptor kinetics and that α2 GABAARs display slower decay kinetics than α1 GABAARs (47–49). Therefore, the increase in tau seen here could reflect the normal developmental switch from α1- to α2-subunit expression in control pups, whereas eDNE pups maintain the α1-subunit at this age.

The Effects of eDNE on Nicotine-Mediated Modulation of GABAergic Synaptic Transmission to XIIMNs

Nicotine can both activate and desensitize/inactivate nAChRs, and it is now well accepted that many of the effects of chronic nicotine exposure result from a complex combination of these two effects (50, 51). Previous work from our laboratory shows that at P1–5 DNE with the osmotic minipump model causes long-term desensitization of nAChRs located postsynaptically on XIIMNs and presynaptically on excitatory glutamatergic synaptic inputs to XIIMNs (22, 24, 52). On the other hand, nAChRs located presynaptically on inhibitory GABAergic and glycinergic terminals that synapse on XIIMNs are functionally upregulated by DNE (15, 23). In the present study, consistent with prior work using the minipump model, we found that eDNE causes functional upregulation of nAChRs located presynaptically on GABAergic neurons that make synaptic contact with XIIMNs. Also, consistent with other work using our new eDNE model, this effect was only apparent in the P10–12 age group; at P1–5 acute nicotine application increased the frequency of GABAergic sIPSCs in XIIMNs from both control and eDNE pups, but by P10–12 acute nicotine application increased GABAergic sIPSCs in eDNE neurons only.

These experiments show that eDNE causes increased sensitivity of nAChRs that mediate GABA release onto XIIMNs in the P10–12 age group. Still, the inability of acute nicotine application to increase sIPSC frequency in XIIMNs from control P10–12 pups is somewhat unexpected. Also, although it did have variable effects on mIPSC kinetics suggesting the potential for postsynaptic modulation of GABAARs, acute nicotine had no impact on mIPSC frequency or amplitude at either age. This is the standard dose of nicotine used by our laboratory and was chosen because it correlates with the peak blood nicotine concentrations that occur after smoking a cigarette (26). In the neonatal brain stem spinal cord preparation this dose of nicotine also produces a robust increase in the frequency of respiratory motor output, and in previous patch-clamp experiments from XIIMNs this dose was able to achieve an increase in both IPSCs and excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in XIIMNs from control P1–5 rats (15, 23, 24). Based on literature assessing other brain regions, the dose of nicotine used here may be right on the threshold of what will consistently stimulate presynaptic GABA release (53, 54), which could explain differences between present and previous experiments. Another possibility is that the diffusion of bath-applied nicotine is slower in older animals because of changes in brain structure with development, which impacts the diffusion of water and solutes within the brain (55, 56). However, whether this impacts drug diffusion in this preparation is not known.

The Effects of eDNE on in Vivo Tongue Muscle Response to Nasal Occlusion

With the in vitro experiments above, we showed that the major effects of eDNE are enhanced nicotine-mediated GABAergic synaptic transmission to XIIMNs at P10–12, which encompasses the days before and encompassing a critical developmental window for the respiratory neural network. We hypothesize that this may underlie changes in breathing and chemoreflex responses that have been reported in nicotine‐exposed infants (57, 58). Critical to this work, the main respiratory phenotype observed in nicotine-exposed human infants is an increased incidence of obstructive apneas, which is thought to be a pathophysiological precursor to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (59) and underscores the impact of nicotine exposure on tongue muscle control.

Inadvertent airway obstruction, such as when an infant’s head gets covered by bedding, is accompanied by an increase in blood CO2 and a decrease in O2. This triggers a chemoreflex response leading to an increase in the release of several neurotransmitters, including GABA and ACh, the endogenous ligand for nAChRs (60, 61). The appropriate changes in excitatory synaptic inputs, along with the postsynaptic response of the motor neurons, are both critical to producing an effective respiratory motor response to chemoreceptor stimulation (60). This response includes increased drive to the respiratory muscles, including the muscles of the tongue, which contribute importantly to the maintenance of airway patency during inspiration.

In a recent publication, we showed that eDNE causes a blunting of the genioglossus EMG response to nasal occlusion and that change in XIIMN intrinsic properties due to eDNE is at least one important factor mediating this effect (22). Here, we investigated the role of GABAAR signaling by testing this response after subcutaneous muscimol injection. As with previous work, after saline injection, the latency to GG EMG onset during nasal occlusion was blunted in eDNE pups at P10–12. The finding that muscimol injection decreased response latency in the eDNE group but had no effect in the control group is consistent with upregulation of GABAARs and that the net effect of global activation of these receptors leads to disinhibition (i.e., inhibition of inhibitory influences) of the brain stem neural circuits that control chemoreflex responses. There are multiple examples of muscimol-mediated disinhibition throughout the brain and brain stem. For instance, intracerebral infusion of muscimol into the mesolimbic dopaminergic terminal site enhances the activity of these neurons (62). In addition, muscimol injected into the depressor area of the caudal ventrolateral medulla increases blood pressure and c-fos expression in the rostral ventral medulla (63). Both examples propose that muscimol acts to silence tonically active inhibitory synaptic inputs to these neuron populations. Phasic and, under certain conditions, tonic inhibitory synaptic transmission to XIIMNs are readily observed (43, 64, 65). Therefore, it is possible that GABAAR activation in the respiratory network plays an important role in disinhibition that allows for the proper enhancement of breathing during chemosensory stimulation and that a functional increase in these receptors due to eDNE is a compensatory mechanism aimed at strengthening this response. However, ultimately, this compensation would be incomplete, as exogenous GABAAR agonists are required to normalize the latency response in eDNE pups. Alternatively, disinhibition mechanisms that possibly occur during nasal occlusion may be overcome by the enhanced effect of GABAAR activation on the XIIMNs themselves. Experiments using targeted microinjections of GABAAR antagonists would be useful in furthering our understanding the consequences of eDNE on GABAergic signaling in chemoreflex responses and should be the focus of future experiments. Finally, although the phrenic motor neurons were not the focus of the present study, it is interesting to note that diaphragm EMG responses remained temporally aligned with GG responses, indicating that eDNE affects motor control mechanisms generally and therefore may cause changes in GABAergic transmission to all respiratory motor neurons.

Translational Significance

Here, we use a model of chronic, episodic nicotine exposure through drinking water that mimics nicotine use in the human population through cigarettes, nicotine gum, or vaping devices. Our most recent publication shows that this method of exposure creates breathing abnormalities and altered synaptic transmission in XIIMNs in the second week of life in rats (22), which correlates with the newborn period in humans, the time when most SIDS deaths occur.

One of the most influential hypotheses put forward to explain SIDS proposes that the coincidence of three factors increases the risk of death: a “vulnerable” infant, an external stressor, and a critical developmental period (66). Near the end of the second week of life in rats, there is a transient period of excitatory/inhibitory imbalance that is thought to be a critical time window for shaping and refinement of the respiratory control network (67). This critical period appears to be genetically predetermined, as it can be delayed or prolonged by external stimuli but not eliminated. Here, we make significant advances in our understanding of how eDNE enhances GABAergic signaling, potentially exacerbating the excitatory/inhibitory imbalance that is a hallmark of this critical period of development, which may be an important mechanism that underlies SIDS.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH grant 5R01HD071302.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.B.W. and R.F.F. conceived and designed research; L.B.W. and E.G.F. performed experiments; L.B.W. and E.G.F. analyzed data; L.B.W. and R.F.F. interpreted results of experiments; L.B.W. and E.G.F. prepared figures; L.B.W. drafted manuscript; L.B.W. and R.F.F. edited and revised manuscript; L.B.W., E.G.F., and R.F.F. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support of Seres J. Cross.

REFERENCES

- 1. Olsen RW, Tobin AJ. Molecular biology of GABAA receptors. FASEB J 4: 1469–1480, 1990. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.5.2155149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Macdonald RL, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor channels. Annu Rev Neurosci 17: 569–602, 1994. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goetz T, Arslan A, Wisden W, Wulff P. GABAA receptors: structure and function in the basal ganglia. Prog Brain Res 160: 21–41, 2007. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of GABA during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat Rev Neurosci 3: 728–739, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nrn920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Owens DF, Liu X, Kriegstein AR. Changing properties of GABAA receptor-mediated signaling during early neocortical development. J Neurophysiol 82: 570–583, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akerman CJ, Cline HT. Refining the roles of GABAergic signaling during neural circuit formation. Trends Neurosci 30: 382–389, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andäng M, Hjerling-Leffler J, Moliner A, Lundgren TK, Castelo-Branco G, Nanou E, Pozas E, Bryja V, Halliez S, Nishimaru H, Wilbertz J, Arenas E, Koltzenburg M, Charnay P, El Manira A, Ibañez CF, Ernfors P. Histone H2AX-dependent GABAA receptor regulation of stem cell proliferation. Nature 451: 460–464, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature06488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Represa A, Ben-Ari Y. Trophic actions of GABA on neuronal development. Trends Neurosci 28: 278–283, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanson MG, Landmesser LT. Characterization of the circuits that generate spontaneous episodes of activity in the early embryonic mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci 23: 587–600, 2003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00587.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu Q, Lowry TF, Wong-Riley MT. Postnatal changes in ventilation during normoxia and acute hypoxia in the rat: implication for a sensitive period. J Physiol 577: 957–970, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barik J, Wonnacott S. Indirect modulation by alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of noradrenaline release in rat hippocampal slices: interaction with glutamate and GABA systems and effect of nicotine withdrawal. Mol Pharmacol 69: 618–628, 2006. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barik J, Wonnacott S. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of action of nicotine in the CNS. Handb Exp Pharmacol 192: 173–207, 2009. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo JZ, Tredway TL, Chiappinelli VA. Glutamate and GABA release are enhanced by different subtypes of presynaptic nicotinic receptors in the lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci 18: 1963–1969, 1998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-01963.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lowe AA. The neural regulation of tongue movements. Prog Neurobiol 15: 295–344, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(80)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wollman LB, Levine RB, Fregosi RF. Developmental plasticity of GABAergic neurotransmission to brainstem motoneurons. J Physiol 596: 5993–6008, 2018. doi: 10.1113/JP274923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jaiswal SJ, Wollman LB, Harrison CM, Pilarski JQ, Fregosi RF. Developmental nicotine exposure enhances inhibitory synaptic transmission in motor neurons and interneurons critical for normal breathing. Dev Neurobiol 76: 337–354, 2016. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Semple BD, Blomgren K, Gimlin K, Ferriero DM, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Prog Neurobiol 106-107: 1–16, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gao XP, Liu QS, Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT. Excitatory-inhibitory imbalance in hypoglossal neurons during the critical period of postnatal development in the rat. J Physiol 589: 1991–2006, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peerboom C, Wierenga CJ. The postnatal GABA shift: a developmental perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 124: 179–192, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berlin I, Heilbronner C, Georgieu S, Meier C, Spreux-Varoquaux O. Newborns’ cord blood plasma cotinine concentrations are similar to that of their delivering smoking mothers. Drug Alcohol Depend 107: 250–252, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Powell GL, Levine RB, Frazier AM, Fregosi RF. Influence of developmental nicotine exposure on spike-timing precision and reliability in hypoglossal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 113: 1862–1872, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.00838.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buls Wollman L, Fregosi RF. Chronic, episodic nicotine alters hypoglossal motor neuron function at a critical developmental time point in neonatal rats. eNeuro 8: ENEURO.0203-21.2021, 2021. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0203-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wollman LB, Levine RB, Fregosi RF. Developmental nicotine exposure alters glycinergic neurotransmission to hypoglossal motoneurons in neonatal rats. J Neurophysiol 120: 1135–1142, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00600.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wollman LB, Clarke J, DeLucia CM, Levine RB, Fregosi RF. Developmental nicotine exposure alters synaptic input to hypoglossal motoneurons, and is associated with altered function of upper airway muscles. eNeuro 6: ENEURO.0299-19.2019, 2019. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0299-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ting JT, Daigle TL, Chen Q, Feng G. Acute brain slice methods for adult and aging animals: application of targeted patch clamp analysis and optogenetics. Methods Mol Biol 1183: 221–242, 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1096-0_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Savanapridi C. Determinants of nicotine intake while chewing nicotine polacrilex gum. Clin Pharmacol Ther 41: 467–473, 1987. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1987.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ren J, Greer JJ. Modulation of respiratory rhythmogenesis by chloride-mediated conductances during the perinatal period. J Neurosci 26: 3721–3730, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0026-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Janssen PL, Williams JS, Fregosi RF. Consequences of periodic augmented breaths on tongue muscle activities in hypoxic rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 88: 1915–1923, 2000. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bailey EF, Jones CL, Reeder JC, Fuller DD, Fregosi RF. Effect of pulmonary stretch receptor feedback and CO2 on upper airway and respiratory pump muscle activity in the rat. J Physiol 532: 525–534, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0525f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rice A, Fuglevand AJ, Laine CM, Fregosi RF. Synchronization of presynaptic input to motor units of tongue, inspiratory intercostal, and diaphragm muscles. J Neurophysiol 105: 2330–2336, 2011. doi: 10.1152/jn.01078.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vautrin J, Barker JL. Presynaptic quantal plasticity: Katz’s original hypothesis revisited. Synapse 47: 184–199, 2003. doi: 10.1002/syn.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. del Castillo J, Katz B. Quantal components of the end-plate potential. J Physiol 124: 560–573, 1954. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]