Keywords: chemical chaperone, molecular chaperone, proteostasis, renal physiology, unfolded protein response (UPR)

Abstract

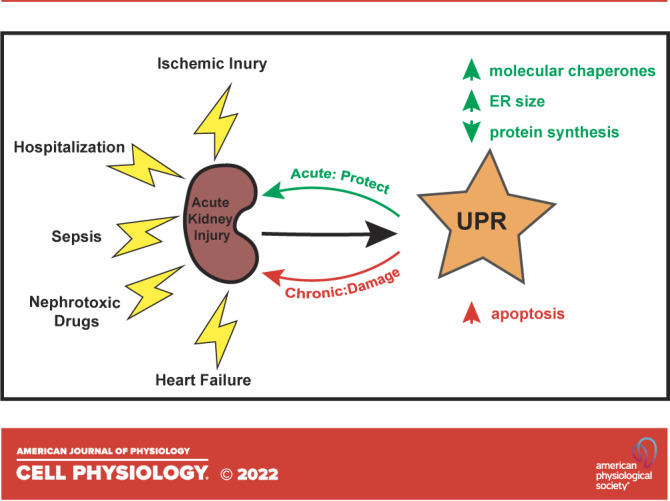

All cell types must maintain homeostasis under periods of stress. To prevent the catastrophic effects of stress, all cell types also respond to stress by inducing protective pathways. Within the cell, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is exquisitely stress-sensitive, primarily because this organelle folds, posttranslationally processes, and sorts one-third of the proteome. In the 1990s, a specialized ER stress response pathway was discovered, the unfolded protein response (UPR), which specifically protects the ER from damaged proteins and toxic chemicals. Not surprisingly, UPR-dependent responses are essential to maintain the function and viability of cells continuously exposed to stress, such as those in the kidney, which have high metabolic demands, produce myriad protein assemblies, continuously filter toxins, and synthesize ammonia. In this mini-review, we highlight recent articles that link ER stress and the UPR with acute kidney injury (AKI), a disease that arises in ∼10% of all hospitalized individuals and nearly half of all people admitted to intensive care units. We conclude with a discussion of prospects for treating AKI with emerging drugs that improve ER function.

INTRODUCTION

The kidney is responsible for regulating serum pH, osmolality, and blood pressure, and reabsorbing nutrients, maintaining electrolyte balance, and excreting metabolic waste. Given these diverse functions—and the dynamic environment to which it is exposed—the kidney is constantly stressed. Yet, all cells, including those in the nephron, have evolved elaborate means of alleviating cell stress and, thereby, maintaining homeostasis (1–3). For example, renal cells activate the heat shock response when exposed to environmental stress such as hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and changes in tonicity (4). Among other outcomes, the induction of this pathway increases the levels of protective chaperones and antioxidants (5).

Although the heat shock response is primarily associated with cytosolic insults, another compartment in the cell, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), is particularly stress-sensitive. Notably, the ER is responsible for the biogenesis of approximately one-third of all cellular proteins, including all membrane proteins and the vast majority of proteins that are secreted from cells (6). The ER is also relatively oxidizing and must maintain high concentrations of calcium. Moreover, ER function is sensitive to nutrient—and more specifically, carbohydrate—deprivation (7), as well as to the accumulation of misfolded proteins as they mature in this organelle. Fortunately, the potentially lethal effects of ER stress can also be counteracted by the induction of a compensatory stress response pathway, the unfolded protein response (UPR) (8).

In this review, we first discuss acute kidney injury (AKI), a condition in which cellular stress responses are evident. We follow this with a historical discussion of how the UPR was discovered, is induced, and leads to the synthesis of downstream effectors that reduce ER stress, or if stress cannot be mitigated, how the UPR initiates an apoptotic cascade. We then provide an overview of recent studies that link the UPR and, more generally, ER stress to AKI. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of novel routes through which AKI might one day be treated with an emerging class of chemical chaperones and ER stress modulators.

ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY

AKI refers to the sudden loss of renal function. Patients present with rising blood creatinine, the accumulation of metabolic byproducts, and impaired water, electrolyte, and acid-base regulation as well as decreased urine output. Although the incidence varies depending on the precise definition of this condition and the population, AKI affects ∼10% of hospitalized patients, including up to 65% of those requiring intensive care (9, 10). Estimates suggest that in the United States alone, there may be as many as 1.5 million cases annually with nearly 100,000 people requiring dialysis (11). Most cases of AKI are due to ischemic injury, sepsis, and nephrotoxic drugs (12, 13).

AKI is associated with an array of adverse short- and long-term outcomes and is an increasingly recognized cause of death (14, 15). Compared to patients with preserved kidney function, those diagnosed with AKI tend to have longer hospitalizations, are more likely to require ventilator assistance, and are at an increased risk to develop hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and kidney failure requiring dialysis. In the United States, annual hospital costs related to AKI conservatively exceed $5 billion dollars, with each episode adding about $2,500 in direct costs for non-ICU patients, which is more than the costs associated with asthma, pneumonia, and heart failure (16). Despite the incidence, consequences, and expense of AKI, proactive fluid management and dialysis remain the only interventions for the condition, much as they were a half-century ago. However, as detailed in might er stress represent a new therapeutic target to treat aki?, we propose that stress response pathways are an accessible and promising target for novel therapies that enhance cell resilience and ameliorate AKI.

THE UNFOLDED PROTEIN RESPONSE: HOW GOOD INTENTIONS CAN LEAD TO APOPTOSIS

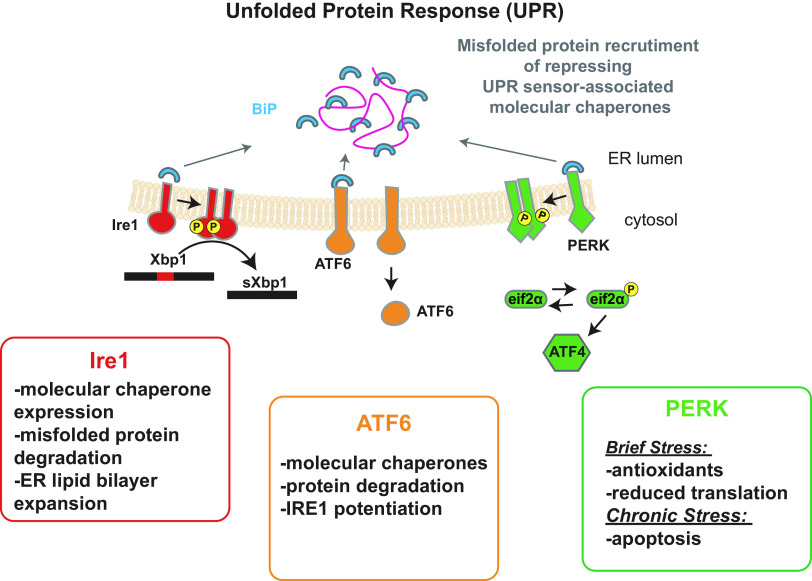

In 1993, the Walter and Gething laboratories identified an ER transmembrane protein, Ire1, that induces the expression of an ER-resident chaperone when yeast is exposed to stress (17, 18). Intriguingly, Ire1 has an ER stress-sensing domain as well as a cytosolic domain that exhibits both kinase and RNA splicing activity. Current models indicate that Ire1 is activated by the release of a repressing chaperone complex in the ER, an event facilitated by an increase in the concentration of ER resident misfolded proteins that recruit the chaperone repressing complex away from Ire1. One member of this complex is an Hsp70 homolog known as BiP (Fig. 1). Ire1 may also bind directly to misfolded proteins and form higher-order oligomers when activated, which is coordinated with Ire1 trans-phosphorylation (19, 20). Oligomer formation is thought to potentiate Ire1 downstream signaling.

Figure 1.

Unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling pathways. The three integral membrane transducers of the UPR in mammalian cells and their most prominent downstream effects are indicated. Although specific details of how each transducer results in unique outcomes may differ, IRE1, ATF6, and PERK are all activated by the dissociation of a repressing molecular chaperone complex from their lumenal domains. As shown, dissociation is triggered by an increase in the concentration of misfolded proteins in the ER. In addition (not shown), UPR strength may also be modulated directly by misfolded proteins, and the pathway can also be initiated by lipid disequilibrium. ATF6 activation requires transport to the Golgi and subsequent cleavage (not shown). The cleaved ATF6 fragment then migrates to the nucleus and directly activates the transcription of target genes. In contrast, IRE1 splices an intron that represses translation of the XBP1 transcription factor, whereas PERK phosphorylates eIF2α, which slows translation and activates another transcription factor—ATF4—that initiates a CHOP-dependent proapoptotic pathway. See text for additional details, and note that only select examples of downstream UPR outcomes are shown.

Following the discovery of Ire1, a transcription factor, Hac1, which acts as a downstream of Ire1 was identified in yeast. Hac1 induces the transcription of genes that protect the ER from stress (19, 21). These seminal studies also showed that translation of the Hac1 message is prevented by a stem-loop forming intron, which is spliced by Ire1. The cleaved HAC1 mRNA is then resealed, and mRNA-associated ribosomes are now able to translate the Hac1 transcription factor and initiate the subsequent expression of ER protectants.

The UPR, as it was termed at that time, is conserved in higher cells, but instead of relying on only one ER resident stress sensor (Ire1), there are three distinct sensors (IRE1, PERK, and ATF6), which diversify the spectrum of downstream events (Fig. 1). For example, mammalian IRE1 primarily increases the synthesis of ER chaperones, the efficiency of protein degradation pathways that destroy toxic misfolded proteins, and several enzymes required for lipid synthesis, which support ER expansion and thus dilute the concentration of misfolded proteins (22). ATF6 similarly induces the expression of protective chaperones, but also increases the levels of the mammalian Hac1 homolog, XBP1, thereby potentiating UPR signaling (23). In contrast to IRE1 and ATF6, the third UPR transducer, PERK, initially increases levels of redox enzymes and slows protein translation, allowing cellular protein quality control machineries to better handle the cohort of existing proteins. Initially, activation of Ire1 and the regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD) pathway also leads to degradation of the transcript for the proapoptotic transcription factor, death receptor 5 (DR5) (24). If, however, ER stress is unresolved, PERK signals the translational reinitiation of select factors, including the proapoptotic factor CHOP, which then increases the synthesis of DR5 (24–26). Accumulation of misfolded proteins in the secretory pathway may also directly initiate proapoptotic events by binding DR5 (27). Together, these UPR outputs are temporally controlled, such that apoptosis is only initiated if initial protective mechanisms fail. In addition, and perhaps relevant to AKI (see the emerging links between the upr and aki), basal expression of UPR transducers is essential to maintain ER homeostasis even in the absence of severe stress (28).

THE EMERGING LINKS BETWEEN THE UPR AND AKI

More than 30 years ago, the Borkan laboratory discovered that a cytosolic heat shock protein, HSP72, was induced in response to ischemic kidney injury in rats (29). The first indication of a connection between ER stress and AKI emerged in 1996 from the observation that ischemic kidney injury upregulates the levels of ER chaperones that support secretory protein folding (30).

In the ensuing years, a potential role of the UPR in AKI pathogenesis—contributing both to recovery and cell death—has emerged (see Table 1 for select examples). For example, in 2005, Montie et al. (31) in their study observed transient phosphorylation of PERK as well as a factor that acts downstream of PERK and controls protein translation, eIF2α, in mouse renal tubular cells following cardiac arrest-associated AKI. CHOP, a downstream proapoptotic effector of PERK (see the unfolded protein response: how good intentions can lead to apoptosis and Fig. 1), also induced apoptosis and exacerbated kidney dysfunction in mouse models of IRI (ischemia-reperfusion injury), toxin-induced AKI, and obstructive nephropathy (32–38, 41). These data suggest that apoptosis is, at least in part, mediated by the PERK-CHOP axis. The PERK-CHOP axis has also recently emerged as a modulator of sepsis-related AKI. Using a cecal ligation and puncture mouse model of sepsis-induced AKI, Jiang et al. observed phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2α and increased CHOP expression. Interestingly, depletion of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP2), an AKI biomarker and cell cycle arrest regulator, reduced ER stress and alleviated sepsis-induced kidney injury. The protective effect of dampening TIMP2 was mediated by the suppression of PERK/CHOP signaling (39). However, in another AKI model (i.e., lipopolysaccharide-induced AKI), CHOP deficiency appeared to increase inflammation and exacerbated kidney injury (40). This unexpected outcome might be due to chronic loss of CHOP, which affects autophagy. These data are consistent with the UPR providing protection against stress at early time points (65).

Table 1.

The unfolded protein response (UPR) and factors required for ER proteostasis are associated with acute kidney injury (AKI)

| Target | Exposure/Treatment | Selected References |

|---|---|---|

| ER stress sensor activation | ||

| PERK-eIF2α-CHOP | Ischemia-reperfusion injury | Montie et al. (31) Chen et al. (32) Noh et al. (33) Yang et al. (34) |

| Nephrotoxin | Wu et al. (35) Zhong et al. (36) Fan et al. (37) Rojas-Franco et al. (38) |

|

| Sepsis | Jiang et al. (39) Esposito et al. (40) |

|

| Obstructive nephropathy | Liu et al. (41) | |

| IRE1-XBP1 | Ischemia-reperfusion injury | Prachasilchai et al. (42) Ding et al. (43) Zhang et al. (44) |

| Nephrotoxin | Rojas-Franco et al. (38) Peyrou et al. (45) Mami et al. (46) Mami et al. (47) |

|

| Sepsis | Ferre et al. (48) | |

| ATF6 | Ischemia-reperfusion injury | Blackwood et al. (49) |

| Nephrotoxin | Rojas-Franco et al. (38) | |

| Altered chaperone activity | ||

| SEC63 depletion | None | Fedeles et al. (50) Ishikawa et al. (51) |

| GRP170 depletion | None | Porter et al. (52) Bando et al. (53) |

| Pharmacological interventions | ||

| General ER stress induction | Tunicamycin/thapsigargin | Yang et al. (34) Prachasilchai et al. (42) Asmellash et al. (54) |

| Stress sensor modulation | GPR120 agonist | Huang et al. (55) |

| PERK and ATF6 inducer | Blas-Valdivia et al. (56) | |

| BiP and eIF2α inhibitor | Zhang et al. (57) | |

| Generalized UPR suppressor | Tang et al. (58) | |

| ATF6 inducer | Blackwood et al. (49) | |

| Enhanced chaperone activity | TUDCA and 4-PBA | Zhong et al. (36) Carlisle et al. (59) Gao et al. (60) |

| Increased BiP expression | BiP inducer X | Prachasilchai et al. (61) |

| HDAC6 inhibition | Proprietary compound | Feng et al. (62) |

| Antioxidant | Resveratrol | Wang et al. (63) Gan et al. (64) |

Various models have been used that either directly target ER components or generally alter ER homeostasis and that then affect renal cells and/or kidney physiology. Only select examples are shown along with associated references. ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

The key components of the IRE1α-XBP-1 and ATF6 branches of the UPR (Fig. 1) have also been linked to AKI (38, 42, 43, 45, 49). In addition to activating PERK, ischemia induces IRE1 phosphorylation and cleaves and activates ATF6, at least at early time points, suggesting that widespread UPR activation represents an initial and perhaps protective response to IRI. Of note, in response to ER stress induced by cytotoxins, IRE1α-XBP1 induces the secretion of a ribonuclease, angiogenin, which limits protein synthesis by promoting tRNA digestion. The net effect of this response is to prevent further accumulation of proteins within the ER. Consistent with this model, angiogenin deficiency increased the susceptibility to tunicamycin-induced injury in both cultured renal tubule epithelial cells and in a transgenic murine model. This effect is presumably due to uninhibited protein translation that increases the levels of misfolded proteins and ER stress in the absence of angiogenin (46, 47).

Activation of the Ire1 branch of the UPR appears to alternatively promote AKI and protect against kidney injury. For example, the Gong laboratory recently reported that heterozygous XBP1+/− mice are resistant to renal ischemia. This protective effect is attributed to reduced expression of HRD1, a ubiquitin ligase required for the destruction of misfolded proteins in the ER. Hrd1 targets the transcription factor NRF2 for degradation, and NRF2 is required to regulate several antioxidant and anti-apoptotic genes. Therefore, reduced Xbp1 levels (i.e., in the XBP1+/− mice) indirectly lead to a more robust response to oxidative stress resulting from IRI (44). Moreover, XBP1 deficiency in tubule epithelia alleviates sepsis-induced AKI, providing yet another example of UPR inhibition reducing kidney injury (48). The potential for UPR derangements to cause irreparable damage was reinforced by the recent discovery that overexpression of XBP1 in the mouse nephron not only induces the expression of BiP, the ER lumenal Hsp70 (Fig. 1), but also induces CHOP, leading to severe, progressive AKI. Overall, although unexplored compensatory responses in these systems might complicate straightforward interpretations, the consequences of UPR activation depend on the cause and timing of injury as well as the experimental model/system.

In parallel studies, chemical ER stress inducers, such as tunicamycin and thapsigargin, provide further insights into potential links between AKI and ER stress. For example, with the UPR initially playing a renal protective role, numerous studies established that transient, low-dose pretreatment with these agents reduces kidney injury from IRI and nephrotoxic drugs (34, 42, 54, 59, 66). Notably, the ER stress inducers selectively modulated the UPR—stimulating BiP and XBP1 activation—but had no effect on the heat shock response. These data strongly suggest that the UPR, rather than a generalized cytoplasmic stress response, accounts for any observed cytoprotective effects. Therefore, modulating the UPR, via activation or suppression, may in principle improve outcomes in patients with AKI.

REFINED SYSTEMS AND CLINICAL DATA THAT BETTER LINK ER STRESS, MOLECULAR CHAPERONE FUNCTION, AND AKI

As outlined in the previous section, many publications have established a potential link between AKI, ER stress, and the UPR. Based on recent work from our laboratory and others, ER stress is likely one cause of kidney tubular injury and possibly AKI. However, initially establishing this paradigm was problematic because systemic genetic ablation of UPR-related proteins is often lethal; thus, few animal models of UPR defects existed (67). Recently, tissue-specific and inducible models have now allowed deeper insights into the role of the UPR in kidney physiology.

In one example, a nephron-specific knockout of SEC63 was constructed. SEC63 is an ER membrane protein required for protein translocation into the ER. SEC63 also anchors the protective molecular chaperone, BiP, at the site of new protein synthesis and folding within the ER (68). In this model, the loss of SEC63 triggers the proliferation of renal tubule cysts and serves as a model for another kidney disease, polycystic kidney disease. The SEC63 knockout also induces IRE1α-XBP1 (but neither PERK nor ATF6) in mice. Moreover, the cystic phenotype is worsened with concomitant deletion of XBP1 (50). Subsequent work revealed that the loss of SEC63 in combination with either IRE1 or XBP1 in distal tubules also causes progressive inflammatory and fibrotic injury (51). Together, these studies strongly suggest that UPR activation is an adaptive response to proteotoxic renal injury. These studies also established that compromised protein homeostasis (“proteostasis”) triggers nephron injury.

A more recent study by our group focused on an inducible, kidney tubule-specific GRP170 knockout mouse (52). GRP170 is an ER-localized chaperone that acts as a BiP co-chaperone (69). Specifically, we demonstrated that GRP170 depletion, in the absence of any other stressor, was sufficient to activate the UPR and compromise water and electrolyte homeostasis (52). Previous work established that GRP170 depletion predisposed mice to ischemic kidney injury, whereas GRP170 overexpression was protective (53). Our work also suggested that polymorphisms in the gene encoding GRP170, along with factors that support ER proteostasis, might represent an unrecognized source or risk factor for kidney disease and AKI.

Clinical evidence corroborates the relationship between ER stress, the UPR, and AKI-like phenotypes. A retrospective analysis of biopsy specimens from patients with AKI found that BiP and phosphorylated/activated PERK were induced in AKI, whereas CHOP and activated/spliced form of XBP1 (sXBP1) negatively correlated with kidney function (37). Consistent with a transient protective role for XBP1, a rapid increase in urinary sXBP1 was associated with a lower likelihood of AKI following cardiopulmonary bypass (70). Notably, urinary angiogenin (see previous section) was detected in transplant recipients with acutely elevated serum creatinine. In fact, the level of urinary angiogenin predicted XBP1 expression in the allografts (46, 71), and among patients following cardiac surgery, a downstream target of ATF6, CRELD2, was predictive of severe AKI (72).

MIGHT ER STRESS REPRESENT A NEW THERAPEUTIC TARGET TO TREAT AKI?

ER stress—and the UPR specifically—has emerged as both a potential cause and consequence of AKI. Therefore, might drugs that modulate ER stress serve as viable treatments? There is growing interest in identifying drugs that correct defects in protein structure and/or reduce the stress that arises from misfolded proteins in the ER (73, 74). To date, however, studies examining the effects of these proteostasis modifiers in AKI are sparse, but as noted in the following paragraphs, significant headway has been made in this field.

Molecules that alter ER proteostasis have shown promise in other conditions, such as neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases (25, 75, 76). Several of these agents also ameliorate AKI (Table 1) (49, 55–58, 61–64, 67, 77). For example, a compound that activates ATF6 and enhances BiP expression blunts the rise in serum creatinine and reduces tissue damage in two murine models of AKI, myocardial ischemia and transient unilateral portal system occlusion. Critically, ATF6 knockout abrogated this effect, indicating that the UPR was uniquely responsible for preserving the tissue (49).

Chemical chaperones—small molecules that augment protein folding—have also shown success in ameliorating kidney injury. For example, BiP Inducer X (BIX), which increases the expression of BiP and ATF6 but neither XBP1 nor CHOP, blunted the rise in serum creatinine and diminished histologic damage 24-h after IRI (61). Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) and 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA), which stabilize and promote the maturation of unfolded proteins in the ER, are also nephroprotective. Of note, pretreatment with TUDCA lowered BiP, CHOP, and caspase-12 expression and reduced tubular injury after tunicamycin treatment or ischemic injury (60). Similarly, 4-PBA inhibited ER stress and reduced the extent of kidney injury in a mercury chloride AKI model (36). 4-PBA also blunted CHOP expression and prevented apoptosis in both human proximal tubular cells and mice treated with tunicamycin (59). The success of these preclinical models indicates that more emphasis needs to be placed on testing emerging drugs that modulate ER proteostasis in these and other systems that reflect AKI.

CONCLUSIONS

There is growing evidence that the UPR modulates AKI. The UPR is induced in various murine models of AKI, and suppressing the UPR limits both the extent of injury and the progression from AKI to CKD. However, the UPR can also be protective against kidney injury. In fact, AKI is more extensive in the absence of UPR signaling, and priming the UPR is renal protective. Therefore, a balance between protective activation and a sustained, damaging UPR is ideal. The precise mechanism for either of these roles, protective or destructive, is still being established. Regardless, the UPR is induced in patients with AKI resulting from various etiologies, consistent with a link between the UPR and renal health. Because AKI affects one in three patients worldwide and is a tremendous burden to the healthcare system (78), chemical modulators that specifically target components of the UPR provide an exciting framework for novel therapeutics. Furthering our understanding of the potential relationship between the UPR and AKI will also help develop UPR effectors as promising targets for novel AKI interventions.

GRANTS

Work in the authors’ laboratories was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 DK117126 (to T.M.B.), NIH Grant R35 GM131732 (to J.L.B.), and the O’Brien Pittsburgh Center for Kidney Research (P30DK079307), and by a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (BRODSK21I0). We also acknowledge Grant K12 HD052892 (to A.W.P.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.W.P. and T.M.B. analyzed data; A.W.P., J.L.B., and T.M.B. interpreted results of experiments; T.M.B. prepared figures; A.W.P., J.L.B., and T.M.B. drafted manuscript; A.W.P., J.L.B., and T.M.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.W.P., J.L.B., and T.M.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Meyer-Schwesinger C. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in kidney physiology and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 15: 393–411, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inagi R, Ishimoto Y, Nangaku M. Proteostasis in endoplasmic reticulum–new mechanisms in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 10: 369–378, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sun Z, Brodsky JL. Protein quality control in the secretory pathway. J Cell Biol 218: 3171–3187, 2019. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201906047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chebotareva N, Bobkova I, Shilov E. Heat shock proteins and kidney disease: perspectives of HSP therapy. Cell Stress Chaperones 22: 319–343, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s12192-017-0790-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li J, Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. Rethinking HSF1 in stress, development, and organismal health. Trends Cell Biol 27: 895–905, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braakman I, Bulleid NJ. Protein folding and modification in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem 80: 71–99, 2011. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062209-093836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lemmer IL, Willemsen N, Hilal N, Bartelt A. A guide to understanding endoplasmic reticulum stress in metabolic disorders. Mol Metab 47: 101169, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hetz C, Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21: 421–438, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ronco C, Bellomo R, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury. Lancet 394: 1949–1964, 2019. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewington AJ, Cerda J, Mehta RL. Raising awareness of acute kidney injury: a global perspective of a silent killer. Kidney Int 84: 457–467, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordonez JD, Chertow GM, Go AS. Community-based incidence of acute renal failure. Kidney Int 72: 208–212, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cely CM, Colman R, Cruz DN, Edipidis K, Forni LG, Gomersall CD, Govil D, Honore PM, Joannes-Boyau O, Joannidis M, Korhonen AM, Lavrentieva A, Mehta RL, Palevsky P, Roessler E, Ronco C, Uchino S, Vazquez JA, Vidal Andrade E, Webb S, Kellum JA. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med 41: 1411–1423, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3934-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ali T, Khan I, Simpson W, Prescott G, Townend J, Smith W, Macleod A. Incidence and outcomes in acute kidney injury: a comprehensive population-based study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1292–1298, 2007. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3365–3370, 2005. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, Parikh CR. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 961–973, 2009. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silver SA, Chertow GM. The economic consequences of acute kidney injury. Nephron 137: 297–301, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000475607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell 73: 1197–1206, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morl K, Ma W, Gething M-J, Sambrook J. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell 74: 743–756, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90521-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Preissler S, Ron D. Early events in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 11: a033894, 2019. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Belyy V, Zuazo-Gaztelu I, Alamban A, Ashkenazi A, Walter P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates human IRE1α through reversible assembly of inactive dimers into small oligomers. eLife 11: e7342, 2022. doi: 10.7554/eLife.74342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell 101: 249–258, 2000. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moncan M, Mnich K, Blomme A, Almanza A, Samali A, Gorman AM. Regulation of lipid metabolism by the unfolded protein response. J Cell Mol Med 25: 1359–1370, 2021. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee K, Tirasophon W, Shen X, Michalak M, Prywes R, Okada T, Yoshida H, Mori K, Kaufman RJ. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev 16: 452–466, 2002. doi: 10.1101/gad.964702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lu M, Lawrence DA, Marsters S, Acosta-Alvear D, Kimmig P, Mendez AS, Paton AW, Paton JC, Walter P, Ashkenazi A. Opposing unfolded-protein-response signals converge on death receptor 5 to control apoptosis. Science 345: 98–101, 2014. doi: 10.1126/science.1254312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wiseman RL, Mesgarzadeh JS, Hendershot LM. Reshaping endoplasmic reticulum quality control through the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell 82: 1477–1491, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334: 1081–1086, 2011. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lam M, Marsters SA, Ashkenazi A, Walter P. Misfolded proteins bind and activate death receptor 5 to trigger apoptosis during unresolved endoplasmic reticulum stress. elife 9: e52291, 2020. doi: 10.7554/eLife.52291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rutkowski DT, Hegde RS. Regulation of basal cellular physiology by the homeostatic unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol 189: 783–794, 2010. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Emami A, Schwartz JH, Borkan SC. Transient ischemia or heat stress induces a cytoprotectant protein in rat kidney. Am J Physiol 260: F479–F485, 1991. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.260.4.F479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuznetsov G, Bush KT, Zhang PL, Nigam SK. Perturbations in maturation of secretory proteins and their association with endoplasmic reticulum chaperones in a cell culture model for epithelial ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 8584–8589, 1996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Montie HL, Kayali F, Haezebrouck AJ, Rossi NF, Degracia DJ. Renal ischemia and reperfusion activates the eIF 2 alpha kinase PERK. Biochim Biophys Acta 1741: 314–324, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen BL, Sheu ML, Tsai KS, Lan KC, Guan SS, Wu CT, Chen LP, Hung KY, Huang JW, Chiang CK, Liu SH. CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein deficiency attenuates oxidative stress and renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 23: 1233–1245, 2015. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Noh MR, Kim JI, Han SJ, Lee TJ, Park KM. C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) gene deficiency attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 1852: 1895–1901, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang JR, Yao FH, Zhang JG, Ji ZY, Li KL, Zhan J, Tong YN, Lin LR, He YN. Ischemia-reperfusion induces renal tubule pyroptosis via the CHOP-caspase-11 pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F75–F84, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00117.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu CT, Sheu ML, Tsai KS, Chiang CK, Liu SH. Salubrinal, an eIF2alpha dephosphorylation inhibitor, enhances cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity in a mouse model. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 671–680, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhong Y, Wang B, Hu S, Wang T, Zhang Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Zhang H. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in renal damage caused by acute mercury chloride poisoning. J Toxicol Sci 45: 589–598, 2020. doi: 10.2131/jts.45.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fan Y, Xiao W, Lee K, Salem F, Wen J, He L, Zhang J, Fei Y, Cheng D, Bao H, Liu Y, Lin F, Jiang G, Guo Z, Wang N, He JC. Inhibition of reticulon-1a-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress in early AKI attenuates renal fibrosis development. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2007–2021, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016091001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rojas-Franco P, Franco-Colin M, Torres-Manzo AP, Blas-Valdivia V, Thompson-Bonilla MDR, Kandir S, Cano-Europa E. Endoplasmic reticulum stress participates in the pathophysiology of mercury-caused acute kidney injury. Ren Fail 41: 1001–1010, 2019. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2019.1686019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jiang N, Huang R, Zhang J, Xu D, Li T, Sun Z, Su L, Peng Z. TIMP2 mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress contributing to sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. FASEB J 36: e22228, 2022. doi: 10.1096/fj.202101555RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Esposito V, Grosjean F, Tan J, Huang L, Zhu L, Chen J, Xiong H, Striker GE, Zheng F. CHOP deficiency results in elevated lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F440–450, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00487.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu SH, Wu CT, Huang KH, Wang CC, Guan SS, Chen LP, Chiang CK. C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) deficiency ameliorates renal fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstructive kidney disease. Oncotarget 7: 21900–21912, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Prachasilchai W, Sonoda H, Yokota-Ikeda N, Oshikawa S, Aikawa C, Uchida K, Ito K, Kudo T, Imaizumi K, Ikeda M. A protective role of unfolded protein response in mouse ischemic acute kidney injury. Eur J Pharmacol 592: 138–145, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ding C, Dou M, Wang Y, Li Y, Wang Y, Zheng J, Li X, Xue W, Ding X, Tian P. miR-124/IRE-1alpha affects renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress in renal tubular epithelial cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 52: 160–167, 2020. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmz150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang J, Zhang J, Ni H, Wang Y, Katwal G, Zhao Y, Sun K, Wang M, Li Q, Chen G, Miao Y, Gong N. Downregulation of XBP1 protects kidney against ischemia-reperfusion injury via suppressing HRD1-mediated NRF2 ubiquitylation. Cell Death Discov 7: 44, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00425-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peyrou M, Hanna PE, Cribb AE. Cisplatin, gentamicin, and p-aminophenol induce markers of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the rat kidneys. Toxicol Sci 99: 346–353, 2007. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mami I, Bouvier N, El Karoui K, Gallazzini M, Rabant M, Laurent-Puig P, Li S, Tharaux PL, Beaune P, Thervet E, Chevet E, Hu GF, Pallet N. Angiogenin mediates cell-autonomous translational control under endoplasmic reticulum stress and attenuates kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 863–876, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mami I, Tavernier Q, Bouvier N, Aboukamis R, Desbuissons G, Rabant M, Poindessous V, Laurent-Puig P, Beaune P, Tharaux PL, Thervet E, Chevet E, Anglicheau D, Pallet N. A novel extrinsic pathway for the unfolded protein response in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2670–2683, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015060703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ferre S, Deng Y, Huen SC, Lu CY, Scherer PE, Igarashi P, Moe OW. Renal tubular cell spliced X-box binding protein 1 (Xbp1s) has a unique role in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury and inflammation. Kidney Int 96: 1359–1373, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Blackwood EA, Azizi K, Thuerauf DJ, Paxman RJ, Plate L, Kelly JW, Wiseman RL, Glembotski CC. Pharmacologic ATF6 activation confers global protection in widespread disease models by reprograming cellular proteostasis. Nat Commun 10: 187, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fedeles SV, So JS, Shrikhande A, Lee SH, Gallagher AR, Barkauskas CE, Somlo S, Lee AH. Sec63 and Xbp1 regulate IRE1alpha activity and polycystic disease severity. J Clin Invest 125: 1955–1967, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI78863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ishikawa Y, Fedeles S, Marlier A, Zhang C, Gallagher AR, Lee AH, Somlo S. Spliced XBP1 rescues renal interstitial inflammation due to loss of Sec63 in collecting ducts. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 443–459, 2019. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018060614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Porter AW, Nguyen DN, Clayton DR, Ruiz WG, Mutchler SM, Ray EC, Marciszyn AL, Nkashama LJ, Subramanya AR, Gingras S, Kleyman TR, Apodaca G, Hendershot LM, Brodsky JL, Buck TM. The molecular chaperone GRP170 protects against ER stress and acute kidney injury in mice. JCI Insight 7: e151869, 2022. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.151869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bando Y, Tsukamoto Y, Katayama T, Ozawa K, Kitao Y, Hori O, Stern DM, Yamauchi A, Ogawa S. ORP150/HSP12A protects renal tubular epithelium from ischemia-induced cell death. FASEB J 18: 1401–1403, 2004. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1161fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Asmellash S, Stevens JL, Ichimura T. Modulating the endoplasmic reticulum stress response with trans-4,5-dihydroxy-1,2-dithiane prevents chemically induced renal injury in vivo. Toxicol Sci 88: 576–584, 2005. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huang Z, Guo F, Xia Z, Liang Y, Lei S, Tan Z, Ma L, Fu P. Activation of GPR120 by TUG891 ameliorated cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury via repressing ER stress and apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother 126: 110056, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Blas-Valdivia V, Rojas-Franco P, Serrano-Contreras JI, Sfriso AA, Garcia-Hernandez C, Franco-Colin M, Cano-Europa E. C-phycoerythrin from Phormidium persicinum prevents acute kidney injury by attenuating oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mar Drugs 19: 589, 2021. doi: 10.3390/md19110589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang Y, Zhang JJ, Liu XH, Wang L. CBX7 suppression prevents ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress through the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 318: F1531–F1538, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00088.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tang C, Hu Y, Gao J, Jiang J, Shi S, Wang J, Geng Q, Liang X, Chai X. Dexmedetomidine pretreatment attenuates myocardial ischemia reperfusion induced acute kidney injury and endoplasmic reticulum stress in human and rat. Life Sci 257: 118004, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Carlisle RE, Brimble E, Werner KE, Cruz GL, Ask K, Ingram AJ, Dickhout JG. 4-Phenylbutyrate inhibits tunicamycin-induced acute kidney injury via CHOP/GADD153 repression. PLoS One 9: e84663, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gao X, Fu L, Xiao M, Xu C, Sun L, Zhang T, Zheng F, Mei C. The nephroprotective effect of tauroursodeoxycholic acid on ischaemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 111: 14–23, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Prachasilchai W, Sonoda H, Yokota-Ikeda N, Ito K, Kudo T, Imaizumi K, Ikeda M. The protective effect of a newly developed molecular chaperone-inducer against mouse ischemic acute kidney injury. J Pharmacol Sci 109: 311–314, 2009. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08272sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Feng Y, Huang R, Guo F, Liang Y, Xiang J, Lei S, Shi M, Li L, Liu J, Feng Y, Ma L, Fu P. Selective histone deacetylase 6 inhibitor 23BB alleviated rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Front Pharmacol 9: 274, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang N, Mao L, Yang L, Zou J, Liu K, Liu M, Zhang H, Xiao X, Wang K. Resveratrol protects against early polymicrobial sepsis-induced acute kidney injury through inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-activated NF-kappaB pathway. Oncotarget 8: 36449–36461, 2017. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gan Y, Tao S, Cao D, Xie H, Zeng Q. Protection of resveratrol on acute kidney injury in septic rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 36: 1015–1022, 2017. doi: 10.1177/0960327116678298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kania E, Pająk B, Orzechowski A. Calcium homeostasis and ER stress in control of autophagy in cancer cells. Biomed Res Int 2015: 352794, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/352794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yan M, Shu S, Guo C, Tang C, Dong Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in ischemic and nephrotoxic acute kidney injury. Ann Med 50: 381–390, 2018. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2018.1489142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cybulsky AV. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, the unfolded protein response and autophagy in kidney diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol 13: 681–696, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pfeffer S, Dudek J, Zimmermann R, Forster F. Organization of the native ribosome-translocon complex at the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta 1860: 2122–2129, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Behnke J, Feige MJ, Hendershot LM. BiP and its nucleotide exchange factors Grp170 and Sil1: mechanisms of action and biological functions. J Mol Biol 427: 1589–1608, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fohlen B, Tavernier Q, Huynh TM, Caradeuc C, Le Corre D, Bertho G, Cholley B, Pallet N. Real-time and non-invasive monitoring of the activation of the IRE1alpha-XBP1 pathway in individuals with hemodynamic impairment. EBioMedicine 27: 284–292, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tavernier Q, Mami I, Rabant M, Karras A, Laurent-Puig P, Chevet E, Thervet E, Anglicheau D, Pallet N. Urinary angiogenin reflects the magnitude of kidney injury at the infrahistologic level. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 678–690, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016020218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kim Y, Park SJ, Manson SR, Molina CA, Kidd K, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Perry RJ, Liapis H, Kmoch S, Parikh CR, Bleyer AJ, Chen YM. Elevated urinary CRELD2 is associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated kidney disease. JCI Insight 2: e92896, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Marciniak SJ, Chambers JE, Ron D. Pharmacological targeting of endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 21: 115–140, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Grandjean JMD, Wiseman RL. Small molecule strategies to harness the unfolded protein response: where do we go from here? J Biol Chem 295: 15692–15711, 2020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV120.010218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annu Rev Biochem 84: 435–464, 2015. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-033955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kelly JW. Pharmacologic approaches for adapting proteostasis in the secretory pathway to ameliorate protein conformational diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12: a034108, 2020. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a034108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Chen JH, Wu CH, Chiang CK. Therapeutic approaches targeting proteostasis in kidney disease and fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 22: 8674, 2021. doi: 10.3390/ijms22168674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, Abulfaraj M, Alqahtani F, Koulouridis I, Jaber BL; Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology. World incidence of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1482–1493, 2013. [Erratum in Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1148, 2014]. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00710113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]