Abstract

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after organ transplant. Many patients subsequently develop multiple CSCC following a first CSCC, and the risk of metastasis and death is significantly increased compared to the general population. Post-transplant CSCC represents a disease at the interface of dermatology and transplant medicine. Both systemic chemoprevention and modulation of immunosuppression are frequently employed in patients with multiple CSCC, yet there is little consensus on their use after first CSCC to reduce risk of subsequent tumors. While relatively few controlled trials have been undertaken, extrapolation of observational data suggests the most effective interventions may be at the time of first CSCC. We review the need for intervention after a first post-transplant CSCC and evidence for use of various approaches as secondary prevention, before discussing barriers preventing engagement with this approach and finally highlight areas for future research. Close collaboration between specialties to ensure prompt deployment of these interventions after a first CSCC may improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: cancer, outcomes, transplant, skin cancer, management

A Clinical Case

A 60 year old white male presents for kidney transplant follow-up, 21 years after a deceased donor transplant. Despite an early cellular rejection episode, he has maintained excellent allograft function (baseline creatinine 107 μmol/L) without humoral sensitization on a dual regimen of cyclosporine and azathioprine. He has a history of photodamage but no history of skin cancer or solid-organ malignancy. He has recently had a 1 cm tender keratotic nodule excised from his shin, confirmed histologically as invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC). The patient asks whether anything can be done to decrease his risk of cancer recurrence without putting their allograft at undue risk.

Introduction

Skin is the commonest site for post-transplant malignancy, with up to 200-fold increased incidence of keratinocyte carcinoma (KC) compared to immunocompetent populations (ICP) (1). CSCC accounts for 80% of KC in organ transplant recipients (OTR) (2). Half of OTR develop another CSCC within 3 years of their first (2–5). Metastatic risk from CSCC is doubled in OTR and those who develop multiple (>10) CSCC have up to 26% risk of metastasis (6, 7), with a 3 year median survival (8). CSCC represents a leading cause of cancer-related mortality for some OTR (2,8,9,10) and may be associated with increased risk of internal malignancies (11, 12), consistent with findings in ICP that are not fully explained by known cancer risk factors (13,14,15) and presumably relate to common susceptibility mechanisms. Treatment and surveillance for post-transplant CSCC creates significant economic burden for healthcare providers and patients (16). Interventions to reduce risk are desirable to improve OTR wellbeing, healthcare resource usage, and future cancer-related mortality.

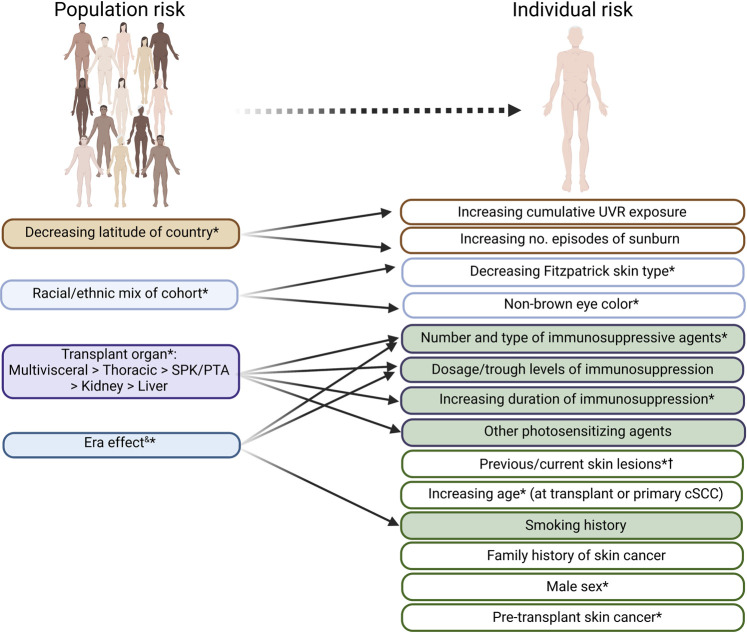

At a population level, cumulative incidence of CSCC amongst OTR is dependent upon several factors, the most important being immunosuppression intensity and geographic latitude (reflecting cumulative ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure) (2). 25% of white European OTR may ultimately develop CSCC, rising to 75% with significant UVR exposure (such as Australasia) (2). Pre-transplant CSCC is a major risk factor for post-transplant CSCC and consensus recommendations regarding the management of such patients have been published elsewhere (17). Individual risk factors are summarized in Figure 1. While used to guide cohort surveillance strategies (4, 18), prognostication using these factors [recently reviewed (19)], particularly for prediction of recurrence, lacks resolution to guide individual patient management.

FIGURE 1.

Clinical risk factors for (further) cSCC development, which may be useful in risk stratifying organ transplant recipients. Factors predictive of cSCC risk at a population level are indicated on the left. Factors relevant at an individual level (which are often interrelated—demonstrated by arrows) are shown on the right, with potentially modifiable factors at time of first cSCC shown in green. *indicates risk factors shown to be independently predictive of development of further KC or cSCC lesions in at least one study. cSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. UVR; UV radiation; SPK, simultaneous kidney-pancreas; PTA, pancreas transplant alone. &time period during which cohort data is collected: generally more historical cohorts demonstrate greater cSCC risk. † including human papillomavirus (HPV)-related viral warts or dysplasia and UVR-related photodamage and pre-malignant lesions.

We summarize staging of disease prevention for post-transplant skin cancer in Table 1 (20, 21). Primary and secondary prevention strategies for CSCC in OTR include patient education, photoprotection, clinical skin surveillance and topical and oral chemoprevention (22), though data in transplant cohorts are limited with recommendations extrapolated from relatively small studies (23–25), expert opinion (26, 27), or studies in ICP (28–30).

TABLE 1.

Definition of stages of CSCC prevention used in this paper.

| Prevention stage | Definition | Example(s) relevant to post-transplant CSCC |

|---|---|---|

| Primordial and primary | Prevent disease onset in susceptible individuals (i.e., with one or more risk factors) | Education regarding UV exposure, promoting use of photoprotection (such as sunscreen) |

| Secondary | Identify patients with early disease and prevent progression | Skin cancer screening, topical or systemic chemoprevention (including management of premalignant lesions) or modulation of immunosuppression in patient with first CSCC to prevent further CSCC. |

| Tertiary | Decrease morbidity and mortality of individuals with advanced disease | Surgery or radiotherapy to locally advanced lesions to prevent metastatic spread; immunotherapy for treatment of metastatic lesions |

| Quaternary | Protect individuals from medical interventions that may cause more harm than good | Avoiding sensitization and rejection resulting from immunosuppression modulation |

Uncertainty about optimal timing of these interventions led to formulation of expert consensus-based recommendations for management, including a recent international Delphi panel of transplant dermatologists (26). While consensus was reached regarding topical and systemic agents in primary and secondary prevention of CSCC, consensus was not reached for optimal interventions after a first low-risk CSCC (LRCSCC; defined in this study, and this paper, as Brigham and Women’s Hospital Stage T1 or T2a, or American Joint Committee on Cancer T1 or T2). Retrospective data suggest there is similar equipoise about optimal timing and nature of immunosuppressive regimen modification amongst transplant practitioners, particularly after first CSCC (3).

In the absence of definitive evidence, we provide an overview of potential interventions for secondary CSCC prevention after the first CSCC and suggest this timepoint as an optimal opportunity to consider initiation of such measures. We consider dermatology, transplant medicine and patient perspectives relevant to decision making and consider the current barriers to adoption of this practice. Finally, we propose a decision framework to guide management of after a first post-transplant CSCC.

Dermatological Strategies

There is scant evidence to guide transplant dermatologists in predicting CSCC risk and employing secondary prevention measures in OTRs after their first LRCSCC. OTR with a history of CSCC should be counselled on skin self-examination and photoprotection and undergoing regular skin cancer surveillance (4, 18), though screening interval recommendations are not consistent across international guidelines. There is randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence that regular use of sunscreen reduces the risk of first CSCC in ICP, but data for benefit in OTR are limited to case-control studies (32).

Actinic keratoses (AK) are clinically apparent hyperkeratotic papules and plaques representing epidermal dysplasia arising on sun-damaged skin; a small proportion proceed to invasive CSCC (0.01%–0.65% in ICP) (33). CSCC in situ (CSCCIS, Bowen disease) represents full-thickness epidermal dysplasia with a higher rate of transformation to CSCC (3%–5% in ICP) (34). AK and CSCCIS may become confluent in areas of ‘field cancerization’, with subclinical disease present in contiguous clinically normal photo-exposed skin. Management of premalignancy is an essential component of secondary prevention. Destructive therapies such as cryotherapy or surgical curettage and cautery tend to be favored for discrete lesions (24). In confluent areas of AK, topical “field directed” treatments are added (35). 5% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream has demonstrated superiority in blinded trials over alternatives in ICP and has also been demonstrated to prevent CSCC (22, 35), with evidence of superiority in OTR limited but growing (29, 36, 37).

Dermatologists may consider oral chemoprevention for patients at high risk of subsequent CSCC, with options including oral retinoids (acitretin) or nicotinamide (26). Acitretin is effective with up to 42% reduction in rates of CSCC in kidney transplant recipients in RCTs (23, 25). However, reported rates of discontinuation due to side effects range from 19%–39% in RCTs of OTR, most commonly due to xerosis and alopecia (23, 25). “Rebound” CSCC formation 3–4 months after drug cessation is frequent, meaning acitretin should be regarded as a long-term strategy (38). These factors may account for part of the documented reluctance of dermatologists to start acitretin after a first CSCC, typically waiting until multiple/high-risk CSCC formation is evident (26). In Australian ICP with a history of multiple KC, oral nicotinamide (active vitamin B3) 500 mg twice daily was well tolerated and resulted in a 30% reduction in CSCC compared to placebo over 12 months, but also showed rebound effects upon discontinuation (24). Nicotinamide has been studied in two insufficiently powered RCTs in kidney transplant recipients (39), but concerns regarding lack of positive data has limited its broader use by dermatologists in OTR (26). Results from a larger Australian RCT are forthcoming. Neither nicotinamide nor acitretin have been associated with significant changes in kidney allograft function or risk of allosensitization.

Modification of Immunosuppression

There are two immunosuppression-based secondary prevention strategies that may reduce risk of subsequent CSCC after a first CSCC: change of immunosuppressive agent or reduction in immunosuppressive intensity.

Change of Agent

Switch to Newer Agents

The direct carcinogenicity of various immunosuppressive agents is well established, particularly with those used prior to the mid-2000s. Azathioprine promotes UVA absorption by DNA, leading to UVA photosensitivity, mutagenicity and a unique mutational signature within CSCC (40, 41). Whilst azathioprine use is largely historical, it is still used in cases of mycophenolate intolerance and in recipients planning pregnancy: furthermore, Furthermore, the lag effect of CSCC development after transplant means many OTR who develop CSCC are still on this agent. Previous studies suggest up to 10% of Australian and US kidney transplant recipients, and up to 69% of Spanish heart transplant recipients, are receiving azathioprine (42). Mycophenolate does not promote UVA sensitivity, though may inhibit DNA repair mechanisms (43). Cyclosporine, but not tacrolimus, impairs UVR-induced DNA damage repair and apoptotic mechanisms and promotes tumor growth in pre-clinical models (41, 44). A large retrospective analysis of OTR found increased skin cancer risk with both cyclosporine and azathioprine compared to tacrolimus and mycophenolate, respectively (45). More recent regimens of tacrolimus and mycophenolate may be associated with a significant reduction in skin cancer risk compared to historical regimens and transition from azathioprine to mycophenolate appears to reduce first CSCC risk (45, 46). A major limitation to evidence for efficacy of this approach for secondary prevention is that the previous studies have been observational only. Belatacept may be an alternative or adjunct to calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) in certain kidney transplant recipients. The impact of belatacept on skin cancer is still emerging with a small single-center study showing lower risk of additional skin cancers after conversion from CNI to belatacept maintenance (47).

Switch to mTOR Inhibitor

Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi) are associated with anti-malignant effects through multiple pathways in vitro (41). Several small studies alongside two large multicenter randomized trials assessed the effect of switching from CNI to sirolimus for CSCC secondary prevention in kidney transplant recipients (48, 49). A 25%–40% reduction in further CSCC risk over 2-year was seen in those converted to sirolimus, though only one study achieved significance across the cohort, and this was seen only after the first but not subsequent CSCC (48). A single episode of borderline rejection was seen across both studies and 5-year follow-up suggested similar patient and graft survival, arguing immunosuppression transition is safe (50). However, sirolimus was generally poorly tolerated with discontinuation and crossover in around a third of recipients due to adverse effects and a CSCC rebound effect was observed. Adverse effects include significant proteinuria, pneumonitis, oedema, impaired wound healing, teratogenicity and hyperlipidaemia. A meta-analysis of 21 trials found mTORi therapy was associated with a significant 60% reduction in KC risk, but also an increased risk of mortality due to infection and cardiovascular disease, though this may be partly due to higher intensity mTORi regimens used in earlier studies (51). For these reasons, sirolimus has not become a mainstay of therapy for CSCC primary or secondary prevention. Recent data have suggested that an alternative mTORi, everolimus, may demonstrate comparable transplant outcomes in low and moderate-risk patients when used alongside low-dose calcineurin inhibition compared to standard immunosuppression (52), and this may reignite interest in the use of mTORi as an immunosuppressant. Analysis of long-term outcomes from earlier studies suggest everolimus is broadly similar to sirolimus in efficacy in reducing KC burden, though tolerability remains a concern (53, 54).

Reduction in Immunosuppression Intensity

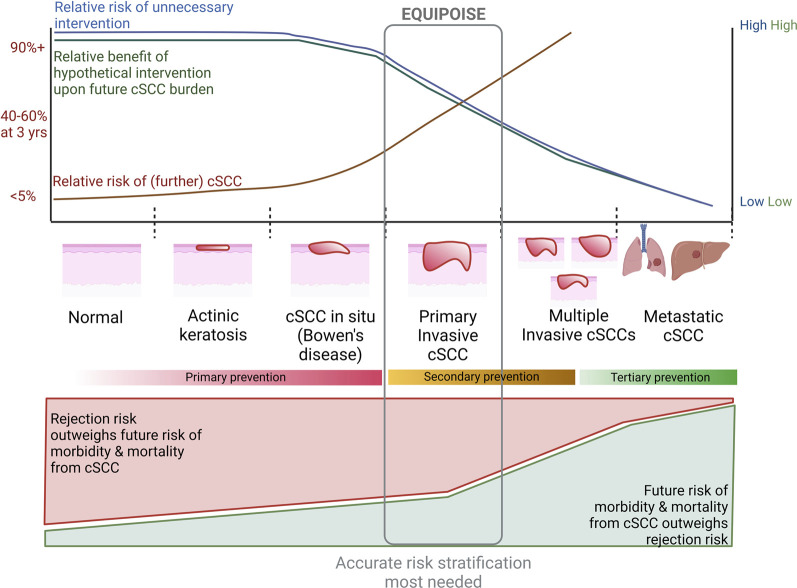

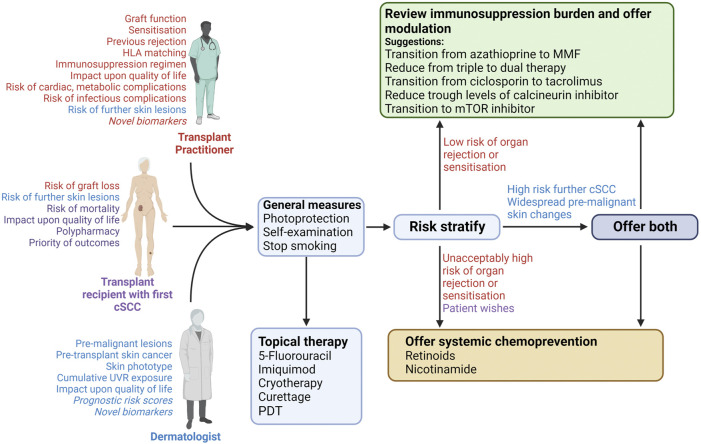

When considering reduction in immunosuppression intensity, the transplant practitioner may consider factors including graft function, pre-existing sensitization and history of rejection episodes, and perceived balance between rejection and future malignancy risk (Figures 2, 3). A major limitation is the lack of methods to determine ‘optimal’ immunosuppression intensity at an individual level. Novel markers to stratify rejection risk are currently being developed, including circulating/urinary transcriptomics, HLA eplet mismatch profiling and donor-derived cell-free DNA [recently reviewed in (55)], but are not in widespread use and require validation regarding utility in guiding immunosuppression reduction.

FIGURE 2.

Considerations in utilizing a hypothetical intervention for reduction of cSCC risk at various stages of disease. Top graph indicates relative risk of future cSCC at a patient level (approximate figures given on Y-axis) and unnecessary intervention, as well as relative benefit upon future malignancy risk from intervention at each stage of squamous carcinogenesis. This graph represents an extrapolation of trial and observational data. Bottom graph represents relative risk of morbidity and mortality from future cSCC and rejection with immunosuppression modulation. We postulate equipoise is greatest at time of first cSCC for most OTR, by which time the risk of further cSCC is high enough that more accurate methods of risk stratification are needed to delineate whether rejection upon immunosuppression modulation or future malignancy are more likely.

FIGURE 3.

Approach to risk stratification and interventions after primary cSCC in an organ transplant recipient. Free-text indicates the important considerations by each member of the discussion (indicated by colour coding: red will be mostly guided by transplant practitioner, purple by the patient, and blue by the dermatologist. Those considerations in italics are not in widespread use but may become relevant in the future). Discussion between the recipient, dermatologist and transplant practitioner should lead to lifestyles changes and the treating dermatologist should offer topical therapy for other lesions, irrespective of perceived cSCC risk. The respective clinicians should subsequently consider cSCC risk alongside perceived risk of allograft rejection/sensitisation. The relative risks of these will guide the offer of immunosuppression modulation and/or systemic chemoprevention. Final discussion between the dermatologist and transplant practitioner will guide on the final interventions offered to the patient. cSCC; cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; PDT, photodynamic therapy; UVR, UV radiation.

Immunosuppression intensity is often related to clinical circumstances, including organ transplant type, and is correlated with first CSCC risk: for example, recipients on dual immunosuppression or with lower CNI trough levels exhibit reduced skin cancer risk compared to counterparts on triple immunosuppression or with greater trough levels (56, 57). Immunosuppression reduction or cessation (following graft failure) is associated with reduced risk and improved outcomes for virus-associated post-transplant malignancy such as lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma (58), presumably by allowing greater immune control of cancer-associated viruses (59). However, data to support this approach for secondary prevention of CSCC is limited to retrospective cohort analyses, usually for advanced disease (3, 56). Immunosuppression modulation could synergize with chemopreventative approaches by permitting enhanced immune responses, but a combined approach has not been explored in either observational or trial settings.

Timing of Interventions

In theory, the earlier the interventions are undertaken, the slower the accumulation of mutations developing, reducing risk of CSCC development.

A landmark trial showed reduction in CNI intensity at 1-year post-transplant was associated with reduced rates of malignancy over the following 5 years, of which two-thirds were skin cancer (57). While associated with an increased rate of acute rejection, this did not appear to compromise graft survival, possibly due to a relatively low event rate, and relatively high trough concentrations (by current standards) of cyclosporine in the intervention arm. Rates of de novo donor-specific antibodies, a marker of allosensitization that reflects under-immunosuppression, or of further CSCC were not assessed. Intensity of cyclosporine therapy in the intervention (low dose) arm was roughly equivalent to that currently used and so whether even further reduction would benefit CSCC risk without compromising graft outcomes is uncertain as is the benefit of reduced doses of tacrolimus.

The most effective intervention timepoint may be before the first CSCC and when premalignant lesions are diagnosed. However, the risk of destabilizing graft function or introducing side-effects with immunosuppression modulation is likely greater than the potential benefit and in most cases quaternary prevention is more relevant (Table 1; Figure 2). Specifically, refractory cellular rejection through excessive immunosuppression reduction may require use of lymphocyte depleting monoclonal antibodies; the use of these at time of transplant as induction therapy is associated with increased risk of subsequent malignancy and it is reasonable to assume the same untoward shift in risk when used as rescue therapy in rejection, though increased CSCC risk has not been demonstrated directly (60).

In contrast, OTRs with a first CSCC are at high risk of further CSCC, representing the optimal time to modulate immunosuppression in most cases. This benefit may extend beyond the skin by impacting common underlying mechanisms responsible for both CSCC and solid organ malignancy (11–15). However, the risks of immunosuppression modulation based upon skin malignancy should be weighed against the ‘number needed to treat’ to prevent future skin and internal malignancy (Figure 2).

As indicated above, RCTs investigating CNI to sirolimus transition demonstrated that OTR with a single CSCC versus multiple CSCC at randomization gained the greatest benefit from a switch to sirolimus, with a striking 90% reduction in CSCC risk over the following 2 years (48–50).

These data indirectly suggest that immunosuppression modulation could be the most effective secondary prevention strategy, if implemented in a timely fashion. We suggest that after a first SCC, OTRs should be considered for transition off older agents, particularly azathioprine. Reduction of CNI target levels may also be appropriate. Sirolimus may be an option for those perceived to be at high risk of multiple subsequent CSCC, but tolerance is a major barrier.

Considerations of the Patient

While the patient will rely on the dermatologist and transplant physician to counsel regarding relative risks, it is important to consider the patient’s perspective.

The median time to first CSCC is typically many years after transplant, unless they have a pre-transplant history of CSCC (2); therefore, any intervention will generally be undertaken in the context of relatively stable graft function. Many OTR harbor an ongoing fear of rejection (61). Studies have found differences in prioritization of graft survival above other outcomes, including cancer and death (61–63), indicating outcomes of importance vary at a patient level. Many of the prevention tools available from a dermatology perspective do not incur risk for rejection but do warrant counselling on side effects and rebound CSCC upon drug cessation. Changes in immunosuppression may pose a rejection risk. While treatment of acute cellular rejection has good outcomes if detected rapidly, under-immunosuppression leading to humoral allosensitization is associated with significantly poorer graft survival and there is no consensus regarding effective treatment (64). Transplant recipients may be reluctant to change immunosuppression without individualized counselling balancing risk and benefits of this approach (61). Such counselling is difficult at present without more accurate CSCC risk stratification tools. Where immunosuppression modulation could be helpful, patients should be counselled regarding the uncertainty of individually predicting future CSCC risk, whilst emphasizing that a first CSCC is frequently associated with development of further lesions. Immunosuppression modulation at this timepoint may represent the optimal time to intervene and may also reduce the risk for other cancers, albeit with limited data to support this. Immunosuppression adjustment should be cautious and stepwise with close monitoring for graft function and sensitization.

How do We Overcome Equipoise?

Two barriers contribute to clinical equipoise regarding secondary prevention: the need for risk stratification and evidence to guide sequencing of preventative strategies.

Perhaps most important is the need for accurate risk stratification, both for further CSCC and rejection. Cohort studies demonstrate that the majority of OTRs with CSCC will form multiple tumors over a 10-year period (4, 6, 7). Risk stratification is critical for formulating secondary prevention interventions, especially as these must be balanced against allograft function. One approach would be to develop more accurate clinical prediction tools based on algorithms to prioritize skin cancer screening and interval surveillance following transplantation (4, 18). Increased intensity of dermatology follow-up in highest-risk cohorts would allow for earlier lesion detection but also an opportunity to initiate intervention with effective field therapies and discussion of chemoprevention agents.

Development of novel biomarkers to facilitate more accurate risk stratification after first CSCC as a complementary approach would serve two purposes: identification of those most likely to benefit from interventions and enrichment of trials with those at greatest risk. A full review of potential biomarkers is beyond the scope of this article. However, circulating immunological markers have been of interest as neoantigens that may drive immunological responses are common (especially in premalignancy) due to the high mutational burden in CSCC and the possible association with HPV (65). Other markers, including polygenic risk scores (66, 67), polymorphisms identified through genome-wide association studies (67–71), circulating (and tumoral) microRNA (72) and tumoral gene expression (73, 74) have been investigated for prognostic value in either OTR or ICP. Only a subset have been validated externally and/or for stratification of further CSCC risk (66, 67, 75, 76, 77). Synchronous stratification for rejection risk would reassure both practitioners and patients regarding immunosuppression reduction.

A second barrier is the lack of clarity regarding relative effectiveness of interventions to reduce secondary CSCC risk and how these should be sequenced. Several dermatological approaches are available to mitigate risk of second CSCC, but studies are limited. For immunosuppression, a single center retrospective study identified 24 different immunosuppression minimization strategies undertaken after first CSCC in kidney and heart transplant recipients (3). Since the sirolimus studies in the 2000s, interventional trials of immunosuppression modification for secondary CSCC risk reduction have been absent. What trial designs might address this? The “Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 therapy (RECOVERY)’ trial offers some inspiration: utilizing a simple design, central randomization with broad inclusion criteria and an adaptive trial platform design facilitated rapid, multi-center enrolment with a hard (mortality) endpoint to compare a series of possible treatments with established best care (78). A similar approach could facilitate a coordinated platform study of dermatological interventions after a first CSCC alongside immunosuppression modulation with the endpoint of subsequent CSCC (or locoregional recurrence/distant metastasis) development. The majority of subsequent CSCC development and poor outcomes are within the first 3 years of the first (2, 4), allowing for a medium-term follow-up period. The historical variety of immunosuppressive regimens have reduced over the last 20 years, coalescing around the use of tacrolimus, mycophenolic acid and/or corticosteroids, reducing the number of combinations to consider, though novel agents such as belatacept, proteosome inhibitors, IL-6 blockade and others may lead to future diversification of regimens.

Conclusion

In summary, while CSCC management is often considered complete after excision, we propose that the first CSCC diagnosis should be regarded as a “red flag” heralding an increased risk of further skin cancers and possibly internal malignancies. It therefore represents a key opportunity to proactively consider secondary preventive strategies, although as optimal preventative interventions and their sequencing remain unclear, further research is needed.

As summarized in Figure 3, based on existing evidence, we recommend that dermatologists should routinely communicate with the transplant team after diagnosis of a first post-transplant CSCC. This event should spark a discussion regarding risk of further lesions, with review of immunosuppression burden and use of chemopreventative therapies. This dialogue between dermatologists, transplant practitioners and patients should be viewed as part of an ongoing shared decision-making process, with the ultimate aim of reducing skin cancer risk, ensuring optimal allograft function and ultimately improving survival and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Figures in this manuscript were created using Biorender.com.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

No original data from studies involving human participants was included in this manuscript. The clinical case described is loosely based upon a real patient but details have been changed for teaching purposes and to ensure anonymity. Ethical approval was therefore not required for this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Manuscript devised by MB, PM, AJ-P, and CH, and initial draft written by MB and PM. All other authors contributed to discussions regarding content, and draft editing.

Funding

MB is supported by grants from the British Skin Foundation, Oxford Hospital Charities, Oxford Transplant Foundation and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Science (CIFMS), China (grant number: 2018-I2M-2-002).

Conflict of Interest

MB has previously received speaker’s fees and an educational grant from Astellas. KB has received honoraria from Sanofi-Genzyme. AJ-P has previously received consulting fees from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Garrett GL, Blanc PD, Boscardin J, Lloyd AA, Ahmed RL, Anthony T, et al. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Skin Cancer in Organ Transplant Recipients in the United States. JAMA Dermatol (2017) 153(3):296–303. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Madeleine MM, Patel NS, Plasmeijer EI, Engels EA, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Toland AE, et al. Epidemiology of Keratinocyte Carcinomas after Organ Transplantation. Br J Dermatol (2017) 177(5):1208–16. 10.1111/bjd.15931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Decullier E, Butnaru AC, Lefrancois N, Boissonnat P, et al. Subsequent Skin Cancers in Kidney and Heart Transplant Recipients after the First Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Transplantation (2006) 81(8):1093–100. 10.1097/01.tp.0000209921.60305.d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harwood CA, Mesher D, McGregor JM, Mitchell L, Leedham-Green M, Raftery M, et al. A Surveillance Model for Skin Cancer in Organ Transplant Recipients: a 22-year Prospective Study in an Ethnically Diverse Population. Am J Transpl (2013) 13(1):119–29. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wehner MR, Niu J, Wheless L, Baker LX, Cohen OG, Margolis DJ, et al. Risks of Multiple Skin Cancers in Organ Transplant Recipients: A Cohort Study in 2 Administrative Data Sets. JAMA Dermatol (2021) 157(12):1447–55. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levine DE, Karia PS, Schmults CD. Outcomes of Patients with Multiple Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas: A 10-Year Single-Institution Cohort Study. JAMA Dermatol (2015) 151(11):1220–5. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gonzalez JL, Reddy ND, Cunningham K, Silverman R, Madan E, Nguyen BM. Multiple Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Immunosuppressed vs Immunocompetent Patients. JAMA Dermatol (2019) 155(5):625–7. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinez JC, Otley CC, Stasko T, Euvrard S, Brown C, Schanbacher CF, et al. Defining the Clinical Course of Metastatic Skin Cancer in Organ Transplant Recipients: a Multicenter Collaborative Study. Arch Dermatol (2003) 139(3):301–6. 10.1001/archderm.139.3.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Venables ZC, Autier P, Nijsten T, Wong KF, Langan SM, Rous B, et al. Nationwide Incidence of Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in England. JAMA Dermatol (2019) 155(3):298–306. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garrett GL, Lowenstein SE, Singer JP, He SY, Arron ST. Trends of Skin Cancer Mortality after Transplantation in the United States: 1987 to 2013. J Am Acad Dermatol (2016) 75(1):106–12. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zamoiski RD, Yanik E, Gibson TM, Cahoon EK, Madeleine MM, Lynch CF, et al. Risk of Second Malignancies in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients Who Develop Keratinocyte Cancers. Cancer Res (2017) 77(15):4196–203. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wisgerhof HC, Wolterbeek R, De Fijter JW, Willemze R, Bouwes Bavinck JN. Kidney Transplant Recipients with Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Have an Increased Risk of Internal Malignancy. J Invest Dermatol (2012) 132(9):2176–83. 10.1038/jid.2012.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zheng G, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Forsti A, Hemminki A, Hemminki K. Incidence Differences between First Primary Cancers and Second Primary Cancers Following Skin Squamous Cell Carcinoma as Etiological Clues. Clin Epidemiol (2020) 12:857–64. 10.2147/CLEP.S256662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wheless L, Black J, Alberg AJ. Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer and the Risk of Second Primary Cancers: a Systematic Review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2010) 19(7):1686–95. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rees JR, Zens MS, Gui J, Celaya MO, Riddle BL, Karagas MR. Non Melanoma Skin Cancer and Subsequent Cancer Risk. PLoS ONE (2014) 9(6):e99674. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gordon LG, Rodriguez‐Acevedo AJ, Papier K, Khosrotehrani K, Isbel N, Campbell S, et al. The Effects of a Multidisciplinary High‐throughput Skin Clinic on Healthcare Costs of Organ Transplant Recipients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2019) 33(7):1290–6. 10.1111/jdv.15458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zwald F, Leitenberger J, Zeitouni N, Soon S, Brewer J, Arron S, et al. Recommendations for Solid Organ Transplantation for Transplant Candidates with a Pretransplant Diagnosis of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Melanoma: A Consensus Opinion from the International Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative (ITSCC). Am J Transpl (2016) 16(2):407–13. 10.1111/ajt.13593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Crow LD, Lowenstein S, Garrett GL, Melcher ML, Chan AW, et al. Predicting Skin Cancer in Organ Transplant Recipients: Development of the SUNTRAC Screening Tool Using Data from a Multicenter Cohort Study. Transpl Int (2019) 32(12):1259–67. 10.1111/tri.13493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lowenstein SE, Garrett G, Toland AE, Jambusaria‐Pahlajani A, Asgari MM, Green A, et al. Risk Prediction Tools for Keratinocyte Carcinoma after Solid Organ Transplantation: a Review of the Literature. Br J Dermatol (2017) 177(5):1202–7. 10.1111/bjd.15889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perez M, Abisaad JA, Rojas KD, Marchetti MA, Jaimes N. Skin Cancer: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Prevention. Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol (2022) 87(2):255–68. 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rojas KD, Perez ME, Marchetti MA, Nichols AJ, Penedo FJ, Jaimes N. Skin Cancer: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Prevention. Part II. J Am Acad Dermatol (2022) 87(2):271–88. 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chung EYM, Palmer SC, Strippoli GFM. Interventions to Prevent Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers in Recipients of a Solid Organ Transplant: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Transplantation (2019) 103(6):1206–15. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bavinck JN, Tieben LM, Van der Woude FJ, Tegzess AM, Hermans J, ter Schegget J, et al. Prevention of Skin Cancer and Reduction of Keratotic Skin Lesions during Acitretin Therapy in Renal Transplant Recipients: a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J Clin Oncol (1995) 13(8):1933–8. 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, Fernandez-Penas P, Dalziell RA, McKenzie CA, et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention. N Engl J Med (2015) 373(17):1618–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1506197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. George R, Weightman W, Russ GR, Bannister KM, Mathew TH. Acitretin for Chemoprevention of Non-melanoma Skin Cancers in Renal Transplant Recipients. Australas J Dermatol (2002) 43(4):269–73. 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Massey PR, Schmults CD, Li SJ, Arron ST, Asgari MM, Bouwes Bavinck JN, et al. Consensus-Based Recommendations on the Prevention of Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol (2021) 157:1219–26. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stasko T, Brown MD, Carucci JA, Euvrard S, Johnson TM, Sengelmann RD, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Organ Transplant Recipients. Dermatol Surg (2004) 30(4 2):642–50. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lopez AT, Carvajal RD, Geskin L. Secondary Prevention Strategies for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) (2018) 32(4):195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jansen MHE, Kessels J, Nelemans PJ, Kouloubis N, Arits A, van Pelt HPA, et al. Randomized Trial of Four Treatment Approaches for Actinic Keratosis. N Engl J Med (2019) 380(10):935–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, Marcolivio K, Means AD, Leader NF, et al. Chemoprevention of Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma with a Single Course of Fluorouracil, 5%, Cream: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol (2018) 154(2):167–74. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kisling LA. Prevention Strategies. Orlando, FL: StatPearls; (2022). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ulrich C, Jurgensen JS, Degen A, Hackethal M, Ulrich M, Patel MJ, et al. Prevention of Non-melanoma Skin Cancer in Organ Transplant Patients by Regular Use of a Sunscreen: a 24 Months, Prospective, Case-Control Study. Br J Dermatol (2009) 161(3):78–84. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09453.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Werner RN, Sammain A, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, Stockfleth E, Nast A, et al. The Natural History of Actinic Keratosis: a Systematic Review. Br J Dermatol (2013) 169(3):502–18. 10.1111/bjd.12420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tokez S, Wakkee M, Louwman M, Noels E, Nijsten T, Hollestein L. Assessment of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC) In Situ Incidence and the Risk of Developing Invasive cSCC in Patients with Prior cSCC In Situ vs the General Population in the Netherlands, 1989-2017. JAMA Dermatol (2020) 156(9):973–81. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nemer KM, Council ML. Topical and Systemic Modalities for Chemoprevention of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Dermatol Clin (2019) 37(3):287–95. 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heppt MV, Steeb T, Niesert AC, Zacher M, Leiter U, Garbe C, et al. Local Interventions for Actinic Keratosis in Organ Transplant Recipients: a Systematic Review. Br J Dermatol (2019) 180(1):43–50. 10.1111/bjd.17148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hasan ZU, Ahmed I, Matin RN, Homer V, Lear JT, Ismail F, et al. Topical Treatment of Actinic Keratoses in Organ Transplant Recipients: a Feasibility Study for SPOT (Squamous Cell Carcinoma Prevention in Organ Transplant Recipients Using Topical Treatments). Br J Dermatol (2022) 187:324–37. 10.1111/bjd.20974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harwood CA, Leedham-Green M, Leigh IM, Proby CM. Low-dose Retinoids in the Prevention of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Organ Transplant Recipients: a 16-year Retrospective Study. Arch Dermatol (2005) 141(4):456–64. 10.1001/archderm.141.4.456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Giacalone S, Spigariolo CB, Bortoluzzi P, Nazzaro G. Oral Nicotinamide: The Role in Skin Cancer Chemoprevention. Dermatol Ther (2021) 34(3):e14892. 10.1111/dth.14892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Inman GJ, Wang J, Nagano A, Alexandrov LB, Purdie KJ, Taylor RG, et al. The Genomic Landscape of Cutaneous SCC Reveals Drivers and a Novel Azathioprine Associated Mutational Signature. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):3667. 10.1038/s41467-018-06027-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Corchado-Cobos R, García-Sancha N, González-Sarmiento R, Pérez-Losada J, Cañueto J. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: From Biology to Therapy. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(8):2956. 10.3390/ijms21082956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jiyad Z, Olsen CM, Burke MT, Isbel NM, Green AC. Azathioprine and Risk of Skin Cancer in Organ Transplant Recipients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Transpl (2016) 16(12):3490–503. 10.1111/ajt.13863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ming M, Zhao B, Qiang L, He Y-Y. Effect of Immunosuppressants Tacrolimus and Mycophenolate Mofetil on the Keratinocyte UVB Response. Photochem Photobiol (2015) 91(1):242–7. 10.1111/php.12318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mittal A, Colegio OR. Skin Cancers in Organ Transplant Recipients. Am J Transpl (2017) 17(10):2509–30. 10.1111/ajt.14382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gibson JAG, Cordaro A, Dobbs TD, Griffiths R, Akbari A, Whitaker S, et al. The Association between Immunosuppression and Skin Cancer in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: a Control-Matched Cohort Study of 2, 852 Patients. Eur J Dermatol (2021) 31(6):712–21. 10.1684/ejd.2021.4108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vos M, Plasmeijer E, van Bemmel B, van der Bij W, Klaver N, Erasmus M, et al. Azathioprine to Mycophenolate Mofetil Transition and Risk of Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2018) 37(7):853–9. 10.1016/j.healun.2018.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang M, Mittal A, Colegio OR. Belatacept Reduces Skin Cancer Risk in Kidney Transplant Recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol (2020) 82(4):996–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Euvrard S, Morelon E, Rostaing L, Goffin E, Brocard A, Tromme I, et al. Sirolimus and Secondary Skin-Cancer Prevention in Kidney Transplantation. N Engl J Med (2012) 367(4):329–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa1204166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hoogendijk-van den Akker JM, Harden PN, Hoitsma AJ, Proby CM, Wolterbeek R, Bouwes Bavinck JN, et al. Two-year Randomized Controlled Prospective Trial Converting Treatment of Stable Renal Transplant Recipients with Cutaneous Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinomas to Sirolimus. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31(10):1317–23. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dantal J, Morelon E, Rostaing L, Goffin E, Brocard A, Tromme I, et al. Sirolimus for Secondary Prevention of Skin Cancer in Kidney Transplant Recipients: 5-Year Results. J Clin Oncol (2018) 36(25):2612–20. 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.6691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Knoll GA, Kokolo MB, Mallick R, Beck A, Buenaventura CD, Ducharme R, et al. Effect of Sirolimus on Malignancy and Survival after Kidney Transplantation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. BMJ : Br Med J (2014) 349:g6679. 10.1136/bmj.g6679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Berger SP, Sommerer C, Witzke O, Tedesco H, Chadban S, Mulgaonkar S, et al. Two-year Outcomes in De Novo Renal Transplant Recipients Receiving Everolimus-Facilitated Calcineurin Inhibitor Reduction Regimen from the TRANSFORM Study. Am J Transpl (2019) 19(11):3018–34. 10.1111/ajt.15480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Preterre J, Visentin J, Saint Cricq M, Kaminski H, Del Bello A, Prezelin-Reydit M, et al. Comparison of Two Strategies Based on Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors in Secondary Prevention of Non-melanoma Skin Cancer after Kidney Transplantation, a Pilot Study. Clin Transpl (2021) 35(3):e14207. 10.1111/ctr.14207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lim WH, Russ GR, Wong G, Pilmore H, Kanellis J, Chadban SJ. The Risk of Cancer in Kidney Transplant Recipients May Be Reduced in Those Maintained on Everolimus and Reduced Cyclosporine. Kidney Int (2017) 91(4):954–63. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bestard O, Thaunat O, Bellini MI, Bohmig GA, Budde K, Claas F, et al. Alloimmune Risk Stratification for Kidney Transplant Rejection. Transpl Int (2022) 35:10138. 10.3389/ti.2022.10138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Otley CC, Maragh SLH. Reduction of Immunosuppression for Transplant-Associated Skin Cancer: Rationale and Evidence of Efficacy. Dermatol Surg (2006) 31(2):163–8. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dantal J, Hourmant M, Cantarovich D, Giral M, Blancho G, Dreno B, et al. Effect of Long-Term Immunosuppression in Kidney-Graft Recipients on Cancer Incidence: Randomised Comparison of Two Cyclosporin Regimens. Lancet (1998) 351(9103):623–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08496-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Van Leeuwen MT, Webster AC, McCredie MRE, Stewart JH, McDonald SP, Amin J, et al. Effect of Reduced Immunosuppression after Kidney Transplant Failure on Risk of Cancer: Population Based Retrospective Cohort Study. BMJ (2010) 340(11 2):c570–c. 10.1136/bmj.c570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Barozzi P, Bonini C, Potenza L, Masetti M, Cappelli G, Gruarin P, et al. Changes in the Immune Responses against Human Herpesvirus-8 in the Disease Course of Posttransplant Kaposi Sarcoma. Transplantation (2008) 86(5):738–44. 10.1097/TP.0b013e318184112c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hall EC, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Segev DL. Association of Antibody Induction Immunosuppression with Cancer after Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation (2015) 99(5):1051–7. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. De Pasquale C, Veroux M, Indelicato L, Sinagra N, Giaquinta A, Fornaro M, et al. Psychopathological Aspects of Kidney Transplantation: Efficacy of a Multidisciplinary Team. World J Transpl (2014) 4(4):267–75. 10.5500/wjt.v4.i4.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Howell M, Tong A, Wong G, Craig JC, Howard K. Important Outcomes for Kidney Transplant Recipients: a Nominal Group and Qualitative Study. Am J Kidney Dis (2012) 60(2):186–96. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.02.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Howell M, Wong G, Rose J, Tong A, Craig JC, Howard K. Patient Preferences for Outcomes after Kidney Transplantation: A Best-Worst Scaling Survey. Transplantation (2017) 101(11):2765–73. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nickerson PW. What Have We Learned about How to Prevent and Treat Antibody‐mediated Rejection in Kidney Transplantation? Am J Transpl (2020) 20(S4):12–22. 10.1111/ajt.15859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Borden ES, Kang P, Natri HM, Phung TN, Wilson MA, Buetow KH, et al. Neoantigen Fitness Model Predicts Lower Immune Recognition of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas Than Actinic Keratoses. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2799. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Stapleton CP, Chang BL, Keating BJ, Conlon PJ, Cavalleri GL. Polygenic Risk Score of Non‐melanoma Skin Cancer Predicts post‐transplant Skin Cancer across Multiple Organ Types. Clin Transpl (2020) 34(8):e13904. 10.1111/ctr.13904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Seviiri M, Law MH, Ong JS, Gharahkhani P, Nyholt DR, Hopkins P, et al. Polygenic Risk Scores Stratify Keratinocyte Cancer Risk Among Solid Organ Transplant Recipients with Chronic Immunosuppression in a High Ultraviolet Radiation Environment. J Invest Dermatol (2021) 141(12):2866–75.e2. 10.1016/j.jid.2021.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chahal HS, Lin Y, Ransohoff KJ, Hinds DA, Wu W, Dai HJ, et al. Genome-wide Association Study Identifies Novel Susceptibility Loci for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Nat Commun (2016) 7:12048. 10.1038/ncomms12048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Siiskonen SJ, Zhang M, Li WQ, Liang L, Kraft P, Nijsten T, et al. A Genome-wide Association Study of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Among European Descendants. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2016) 25(4):714–20. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sarin KY, Lin Y, Daneshjou R, Ziyatdinov A, Thorleifsson G, Rubin A, et al. Genome-wide Meta-Analysis Identifies Eight New Susceptibility Loci for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):820. 10.1038/s41467-020-14594-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Asgari MM, Wang W, Ioannidis NM, Itnyre J, Hoffmann T, Jorgenson E, et al. Identification of Susceptibility Loci for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol (2016) 136(5):930–7. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Geusau A, Borik-Heil L, Skalicky S, Mildner M, Grillari J, Hackl M, et al. Dysregulation of Tissue and Serum microRNAs in Organ Transplant Recipients with Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Health Sci Rep (2020) 3(4):e205. 10.1002/hsr2.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Blue ED, Freeman SC, Lobl MB, Clarey DD, Fredrick RL, Wysong A, et al. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in Immunosuppressed Patients: A Systematic Review of Tumor Profiling Studies. JID Innov (2022) 2(4):100126. 10.1016/j.xjidi.2022.100126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wysong A, Newman JG, Covington KR, Kurley SJ, Ibrahim SF, Farberg AS, et al. Validation of a 40-gene Expression Profile Test to Predict Metastatic Risk in Localized High-Risk Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol (2021) 84(2):361–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bottomley MJ, Harden PN, Wood KJ. CD8+ Immunosenescence Predicts Post-Transplant Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in High-Risk Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol (2016) 27(5):1505–15. 10.1681/ASN.2015030250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Carroll RP, Segundo DS, Hollowood K, Marafioti T, Clark TG, Harden PN, et al. Immune Phenotype Predicts Risk for Posttransplantation Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Am Soc Nephrol (2010) 21(4):713–22. 10.1681/ASN.2009060669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hope CM, Grace BS, Pilkington KR, Coates PT, Bergmann IP, Carroll RP. The Immune Phenotype May Relate to Cancer Development in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Kidney Int (2014) 86(1):175–83. 10.1038/ki.2013.538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Normand S-LT. The RECOVERY Platform. N Engl J Med (2021) 384(8):757–8. 10.1056/NEJMe2025674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.